Abstract

Multiple red, raised nodules multifocally distributed along the serosal surface of the normal and the nonviable jejunum were identified in a 24-year-old neutered male horse undergoing surgery for removal of the strangulating lipoma around the jejunum. Histologically, these nodules consisted of many significantly and variably dilated, blood-filled vascular channels lined by a single layer of flattened, well-differentiated endothelial cells with occasional thrombi within a mildly thickened fibrous stroma. A diagnosis of intestinal angiomatosis was proposed. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the second report of small intestinal angiomatosis in a horse.

Résumé

Angiomatose du petit intestin équin. De multiples nodules rouges surélevés distribués de manière multifocale le long de la surface séreuse du jéjunum viable et non-viable furent identifiés chez un cheval mâle castré âgé de 24 ans soumis à une chirurgie pour le retrait d’un lipome étranglant autour du jéjunum. Histologiquement, ces nodules consistaient en de nombreux canaux vasculaires remplis de sang dilatés de manière significative et variable, et tapissés par une couche unique de cellules endothéliales aplaties et bien différenciées avec à l’occasion des thrombi à l’intérieur d’un stroma fibreux légèrement épaissi. Un diagnostic d’angiomatose intestinale fut proposé. Au meilleur de la connaissance des auteurs, ceci constitue le deuxième rapport d’angiomatose du petit intestin chez un cheval.

(Traduit par Dr Serge Messier)

Case description

A 24-year-old neutered male Arabian-cross horse was presented to a referring veterinarian with a history of severe acute colic. The horse historically had a high fecal parasite ova count based on repeated routine fecal evaluation, (in which the number of parasite eggs/g of feces was 600 to 3000) but was generally healthy and energetic before developing colic.

Ultrasonographic evaluation of the abdomen revealed a strangulating lipoma warranting emergency surgical intervention. Exploratory surgery revealed 2.44 m of grossly non-viable jejunum associated with the strangulating lipoma. The surgeon performed a resection of the nonviable tissue and anastomosis of grossly healthy portions of intestine. The surgeon noted that, in addition to the non-viable appearance of the jejunum, many multifocal small round raised lesions were visible from the serosal aspect of the grossly viable and the non-viable intestine. Two representative biopsies were collected (1 from viable jejunum near the anastomosis site and 1 from the non-viable portion of the jejunum) and submitted to Prairie Diagnostic Services (PDS, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan). Lesions were noted in the viable intestine well beyond the sampled lesion at the anastomosis site. The clinician removed a strangulating lipoma from the jejunum. The multifocal round raised dark red lesions in each biopsy measured between 0.3 × 0.5 cm and 1 × 1 cm. The intestinal samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and routinely processed by paraffin embedding, with subsequent glass slide sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

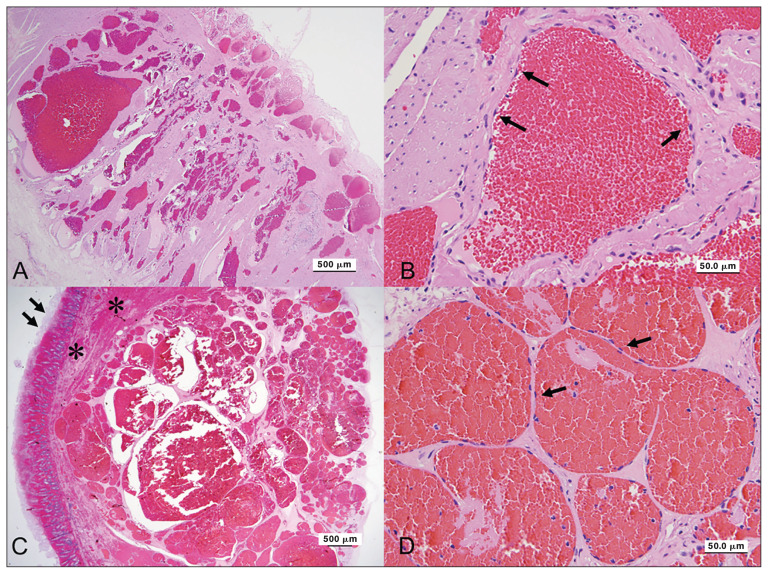

Histologically, the nodules on the grossly normal and abnormal intestinal portions had similar appearance. There were few profiles of relatively well-demarcated, non-encapsulated, multinodular masses within the submucosa and muscle layers of the intestinal biopsies. The masses comprised multiple closely associated, variably dilated, blood-filled vascular channels lined by a single layer of flattened, well-differentiated endothelial cells supported by a mildly thickened fibrous stroma (Figures 1A, B). Few of the vascular channels had thrombi within the lumens. In sections of a larger biopsy of grossly dark red non-viable intestine, the sections revealed a much larger mass with significant hemorrhage within the adjacent muscle layers and overlying submucosa (Figures 1C, D). The mucosal layers contained abundant congestion, hemorrhage and mucosal necrosis.

Figure 1.

Angiomatosis in the jejunum of a horse. A — The lesion in the grossly normal jejunum consists of numerous variable-sized blood vessels mainly in the muscular layer. H&E stain. Scale bar = 500 μm. B — In the grossly normal jejunum, the vascular channels are lined by well-differentiated flattened endothelial cells (arrows). H&E stain. Scale bar = 50 μm. C — The lesion in the grossly normal jejunum consists of numerous variable-sized blood vessels mainly in the muscular layer (arrows). The mucosal layers contain abundant congestion and hemorrhage with mucosal necrosis (asterisks). H&E stain. Scale bar = 500 μm. D — In the grossly abnormal jejunum, the vascular channels are lined by well-differentiated flattened endothelial cells (arrows). H&E stain. Scale bar = 50 μm.

The histologic diagnosis was intestinal angiomatosis with concurrent evidence of focal jejunal mucosal necrosis secondary to a strangulating lipoma in the non-viable tissue submitted. Sixty days following surgery, the horse was reported to be bright, alert, responsive, and energetic with appropriate eating, drinking, and elimination habits.

Discussion

Angiomatosis is a rare vascular malformation characterized by multiple red, raised nodules consisting of several to numerous blood-filled vascular channels lined by well-differentiated endothelial cells and involving multiple tissues (1,2). Angiomatosis has been relatively well-documented in humans with skin, subcutaneous tissue, skeletal muscle, and occasionally bone involved (3). It is primarily observed during childhood or adolescence with high recurrence after surgical resection due to its diffuse infiltrative pattern (4). In young cattle, angiomatosis lesions have been found on multiple organs and diagnosed as juvenile bovine angiomatosis (5). In dogs and cats, the lesions can be progressively proliferative involving both dermis and subcutaneous tissues with benign and variably aggressive forms noted (6,7).

In horses, angiomatosis is uncommon and rarely reported. One report in the literature listed the orbital area with 2 additional separate reports of vascular lesions in spinal cord from individual horses (8–10). So far, only 1 report of angiomatosis from small intestine and 1 from large intestine have been described (2,11). To the authors’ knowledge, this case is the second report of small intestinal angiomatosis in a horse.

Angiomatosis is believed to be an incidental finding in the intestine and is not known to cause clinical disease unless it involves critical locations such as the central nervous system, which makes the angiomatosis diagnosis rare unless a complete necropsy is performed (2). Angiomatosis can be congenital or a reactive, tumor-like vascular proliferation developing after birth in humans; the latter is known as bacillary angiomatosis (12). The specific cause is unknown, but has been presumed to be induced by inflammation, infection by microorganisms, or neoplastic transformation (13).

Angiomatosis must be differentiated from hemomelasma ilei, vascular hamartomas, hemangiomas, and hemangiosarcomas in the intestines. Hemangiomas and hemangiosarcomas occur commonly in dogs but rarely in horses. Hemangiomas are benign and are normally solitary masses in dermis or subcutis, commonly found in younger animals (14). Hemangiosarcomas are the malignant counterpart of hemangiomas. In dogs, hemangiosarcoma most commonly involves visceral locations (including the right auricle and spleen) and the subcutis with potential for metastasis to other organs (14,15). Visceral involvement of hemangiosarcoma, however, is uncommon in other domestic species, including the horse (14). Vascular hamartomas are typically solitary lesions most commonly found in the dermis and subcutis with no breed or sex predilection in horses (16). Vascular hamartomas resemble tumors but are not neoplastic and are regarded as abnormal admixtures of vascular-type tissue and associated supportive tissue (6). Hemangiomas and vascular hamartomas can be difficult to distinguish from vascular malformations, because they are both characterized by increased numbers of blood-filled channels of varying sizes. The multifocal distribution and histological characteristics in this case are not consistent with vascular hamartomas and hemangiomas.

Angiomatosis grossly appears similar to hemomelasma ilei, often with multiple red, round to oval, slightly raised plaques along the subserosal surface of the small intestine, particularly the ileum (2). However, angiomatosis and hemomelasma ilei can be differentiated histologically. Hemomelasma ilei lesions consist of edema, hemorrhage, and a mixed population of leukocytes with prominent erythrophagocytosis and occasionally coupled with an associated fragment of nematode (or portions of parasite components), or rarely, a parasitic migratory tract (17). In general, angiomatosis lesions have more defined vascular channel architecture without appreciable attendant leukocyte presence. These lesions would not be expected to have direct association with parasite components in intestinal lesions (17), which is consistent with the findings in this case. Despite the history of this horse having had historically high fecal parasite ova counts, there was no histologic evidence of parasites or tracts associated with the vascular lesions. In the authors’ experience, angiomatosis lesions can have additional areas of hemorrhage and localized erythrophagocytosis, particularly if traumatized.

We believe the angiomatosis lesions in this case were benign and unrelated to the strangulating lipoma, although there were significant areas of mural hemorrhage adjacent to angiomatosis lesions in the intestinal biopsies and the indirect clinical manifestation of this is uncertain. The strangulating lipoma in this horse caused venous infarction that was demonstrated microscopically by severe transmural congestion, hemorrhage, edema, full thickness mucosal necrosis, and effacement of the crypts in the grossly abnormal jejunum. Based on the current literature (1,2,6,9), prognosis of angiomatosis is uncertain but appears to be good with complete excision; however, even with excision the patient can be predisposed to development of multiple lesions, possibly in multiple organs. Angiomatosis reported in the ovary of a horse did not interfere with the reproductive function according to the provided history (2). However, removal of equine orbital angiomatosis may have the potential to cause extensive hemorrhage due to the critical location (9). Further investigation of angiomatosis lesions occurring in different organ systems in horses is warranted to determine the true prognostic significance which is currently precluded by the paucity of case reports and lack of a case series for this lesion. CVJ

Footnotes

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Khan S, Pujani M, Jetley S, Neogi S. Angiomatosis: A rare vascular proliferation of head and neck region. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:108–110. doi: 10.4103/0974-2077.158448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lamm CG, Njaa BL. Ovarian and intestinal angiomatosis in a horse. Vet Pathol. 2007;44:386–388. doi: 10.1354/vp.44-3-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howat AJ, Campbell PE. Angiomatosis: A vascular malformation of infancy and childhood. Report of 17 cases. Pathology. 1987;19:377–382. doi: 10.3109/00313028709103887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shetty SR, Prabhu S. Angiomatosis in the head and neck — 3 case reports. Head Neck Pathol. 2009;3:54–58. doi: 10.1007/s12105-009-0105-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watson TD, Thompson H. Juvenile bovine angiomatosis: A syndrome of young cattle. Vet Rec. 1990;127:279–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim Y, Reinecke S, Malarkey DE. Cutaneous angiomatosis in a young dog. Vet Pathol. 2005;42:378–381. doi: 10.1354/vp.42-3-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gross TL, Ihrke PJ, Walder EJ, Affolter VK. Skin Diseases of the Dog and Cat: Clinical and Histopathologic Diagnosis. 2nd ed. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Science; 2005. pp. 749–753. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gilmour JS, Fraser JA. Ataxia in a Welsh cob filly due to a venous malformation in the thoracic spinal cord. Equine Vet J. 1977;9:40–42. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1977.tb03974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ludwig HC, Pucket JD, Shaw GC. Equine orbital angiomatosis. Equine Vet Educ. 2017;29:426–430. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palmer ACH, Hickman J. Ataxia in a horse due to an angioma of the spinal cord. Vet Rec. 1960;72:613. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Platt H. Vascular malformations and angiomatous lesions in horses: A review of 10 cases. Equine Vet J. 1987;19:500–504. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1987.tb02658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howard GM, Jakobiec FA, Michelsen WJ. Orbital arteriovenous malformation with secondary capillary angiomatosis treated by embolization with silastic liquid. Ophthalmology. 1983;90:1136–1139. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(83)80059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richard V, Drolet R, Fortin M. Juvenile bovine angiomatosis in the mandible. Can Vet J. 1995;36:113–114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meuten DJ. Tumors of the hemolymphatic system. In: Meuten DJ, editor. Tumors in Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Ames, Iowa: John Wiley & Sons; 2017. pp. 203–321.pp. 499–601. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Withrow SJ, Vail DM. Small Animal Clinical Oncology. 4th ed. St Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elsevier; 2007. pp. 785–795. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saifzadeh S, Derakhshanfar A, Shokouhi F, Hashemi M, Mazaheri R. Vascular hamartoma as the cause of hind limb lameness in a horse. J Vet Med A Physiol Pathol Clin Med. 2006;53:202–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0442.2006.00818.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maxie DG. Alimentary and peritoneum. In: Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, Palmer N, editors. Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol. 2. St. Louis, Missouri: Saunders Elsevier; 2015. p. 284. [Google Scholar]