To the Editor:

We read with great interest the recent article from Bruni and colleagues (1) describing a hotel-based cohort model for patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19) convalescing from a hospital admission. They have shown preliminary evidence that such a model is feasible. Between mid-April and early May, we developed a similar model we have termed COVID-19 Intermediate Care (2) in the Saskatchewan Health Authority, an integrated provincial health system in Saskatchewan, located in Western Canada, serving a population of 1.2 million people spread out over 651,900 km2. We have a vast geographic area that is divided into quadrants that are governed centrally. An iterative method involving expertise from infectious disease, respiratory medicine, primary care, information technology, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, homecare services, supply chain, emergency medical services, and operational leadership was used to create a model sensitive to intraprovincial regional needs. Guiding principles for patient-centered, culturally responsive, collaborative, and integrated care were used.

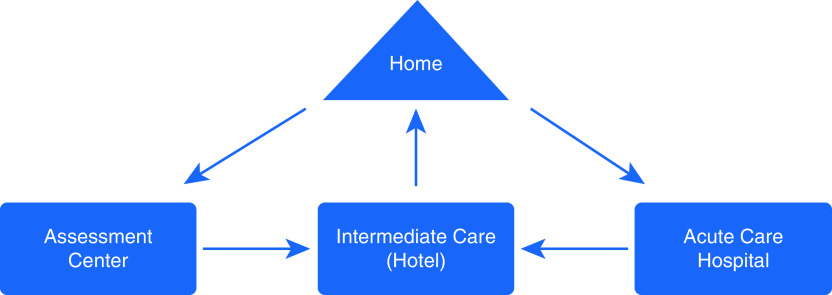

For similar reasons described in the model of Bruni and colleagues (1), we have also decided to use hotels as alternative sites of care. In contrast to their purely convalescent model, ours involves multiple entry points into intermediate care (Figure 1). Not only do patients who are positive for COVID-19 and are convalescing after acute care hospital admission transition there, but appropriate subacute patients identified in dedicated COVID-19 assessment centers and emergency rooms can also enter intermediate care according to established criteria (Table 1). Inherent in our model is the assumption that patients are living independently prior to acquiring COVID-19 and will return to the same setting once they have recovered (see Table 2 for a complete list of assumptions).

Figure 1.

Saskatchewan Health Authority intermediate care pathway.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics of Intermediate Care

| Subacute | Postacute |

|---|---|

| Medically stable but require observation | Require convalescent care or observation following acute care admission |

| May have hypoxemia | May have persistent hypoxemia |

| Unable to self-isolate and at risk of infecting others in household |

Table 2.

Assumptions Inherent to Intermediate Care Pathway

| All patients are COVID-19 swab positive (in exceptional cases/settings, presumptive COVID-19 will be included) |

| Any patient admitted to this setting is living independently prior to entry and anticipated to return to independent living |

| Care may be up to 6 wk in duration |

| No aerosol-generating procedures are anticipated for any patient |

| Current homecare standards will apply |

| Care in this setting is voluntary |

| Entry, exit, and escalation to acute care will be coordinated by the site lead |

| Staff will be screened in accordance with health authority standards |

Definition of abbreviation: COVID-19 = coronavirus disease.

Bruni and colleagues have built the clinical care model around twice daily assessment of patients by a respiratory physician using remote monitoring (no details of how monitoring is done were included) (1). We have designed our model to include a maximum 50:1 patient-to-physician ratio, with an expectation that primary care physicians will be the usual providers with backup available from respiratory consultants or others as needed. This is achieved by using a proprietary digital system (Home Health Monitoring; TELUS Health) that creates a dashboard of data collected from all patients being monitored in a given location. Patients are provided with tools and digital media to input their own biophysical data (temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation) together with answering a specifically designed COVID-19 digital questionnaire twice daily. Triage of patient care is based on changes/abnormalities in the biophysical data (which is tailored each patient) together with answers to key questions that prompt yellow and red flags under predetermined conditions. The physician can then decide to interact with the patient by video conference through the platform or, if necessary, in person. The frequency and intensity of monitoring is tailored to the clinical status of each patient within the system. For example, the questionnaires are specifically designed to be different between patients entering from an assessment center/emergency room compared with those convalescing from acute care.

In addition to physician staffing, our model includes resources for other allied health professionals, including rehabilitation (physiotherapy and occupational therapy), nutrition services, and nursing. As pointed out by Bruni and colleagues, the physical characteristics of a hotel setting create many efficiencies for staffing of allied health services. An onsite paramedic is also included to provide an immediate response in the event of a respiratory/cardiac emergency that may result in transfer to a nearby hospital. Additionally, we have included onsite security personnel to monitor and enforce public health orders regarding visitation.

To date, our jurisdiction has had great success with social distancing, self-isolation, and robust contact tracing in containing COVID-19. At the time of writing this, we have had a total of 962 cases with 15 deaths and enjoy an effective reproductive number of approximately 2.3 (recently increased from <1.0 because of a localized and contained outbreak). Fortunately, to date, our hospitals have not been overwhelmed like some of our Canadian and international peers. As such, we have not yet had to activate this model of care. We highly appreciate the data presented by our Italian colleagues that supports the feasibility of the convalescent part of our model. It remains to be seen how our multientry point model performs relative to theirs.

In summary, we applaud Bruni and colleagues (1) on their work and present a similar but more comprehensive hotel-based model of COVID-19 care.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Author Contributions: All authors were involved in preparation and review of the content. In addition, all authors were involved in the planning of the care model described in the letter.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202007-2902LE on August 13, 2020

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Bruni T, Lalvani A, Richeldi L.Telemedicine-enabled accelerated discharge of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 to isolation in repurposed hotel rooms Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020202508–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Saskatchewan Health Authority. Saskatchewan Health Authority COVID-19 emergency response plan: intermediate care [published 2020 Jul 9]. Available from: https://www.saskatchewan.ca/government/health-care-administration-and-provider-resources/treatment-procedures-and-guidelines/emerging-public-health-issues/2019-novel-coronavirus/pandemic-planning#community-surge-planning.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.