Abstract

The exposome is a concept that underlines the critical relationship between health and environmental exposures, including environmental toxicants. Currently, most environmental exposures that contribute to the exposome have not been characterized. Dried-blood spots (DBS) offer a cost-effective, reliable approach to characterize the blood exposome, which consists of diverse endogenous and exogenous chemicals, including persistent and bioaccumulating organic compounds. Current challenges involve prioritizing the identification by state-of-the-art mass spectrometry of likely up to tens of thousands of compounds present in blood; characterizing substances that represent a mixture of myriad constituent compounds; and detecting trace level contaminants, especially in quantity-limited matrices like DBS. This contribution reviews recent trends in DBS analysis of chemical pollutants and highlights the need for continued research in analytical chemistry to advance the field of exposomics.

1. Introduction

The exposome encompasses the totality of environmental exposures and over a lifetime1,2. These exposures can be characterized using endogenous and exogenous chemical compounds that result from diet, lifestyle, radiation, stress, and environmental pollutants1. Such factors likely play a greater role than genetics in the development of many chronic diseases, but the complex relationship between exposure and disease remains ambiguously defined at best. Unlike the genome, environmental exposures are dynamic and thus require frequent, cost-effective, and minimally invasive measurements to characterize variation over time.

In their pioneering study, Rappaport et al.3 explored the exposure-disease associations of 1,561 small molecules and metals derived from foods, drugs, endogenous processes and environmental pollutants in blood samples. The cumulative distribution of these compounds, see Figure 1, show that their blood concentrations span >11 orders of magnitude and that the concentrations of the pollutants are ~1000-fold lower than the remaining classes. This disparity has reinforced the view that the presence of drugs, food chemicals, natural toxins and other endogenous chemicals must be considered when assessing disease risks. The exogenous pollutants were primarily halogenated and exhibited common behaviour, such as environmental persistence, lipophilicity, toxicity and long-range transport potential4–9. Since the early 2000s, signatories of the Stockholm Convention10 have imposed restrictions on the emission and production of over twenty-eight groups of these chemicals, coined persistent organic pollutants (POPs). The success of regulation is reflected by the steady decline in blood concentrations of some POPs11,12. While continuing to monitor the effectiveness of regulating these compounds is important, one could argue that continued scrutiny of the impacts of dozens of regulated pollutants adds little to our understanding the etiology of disease, and that if we expect to reduce the burden of chronic disease, it is essential to develop methodologies that enable identification of unrecognized chemicals that potentially impact health13.

Figure 1.

The blood exposome3. Each curve represents the cumulative distribution of chemical species classified as pollutants (n=94), drugs (n=49), food chemicals (n=195) and endogenous chemicals (n=1223). Note that persistent organic pollutants, such as DDE (dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene), PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid), PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls), PBDEs (polybrominated diphenyl ethers) and OCDD (octachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin) constitute a large fraction of the environmental pollutants. This figure was reproduced from Environmental Health Perspectives with permission from the authors.

Suspected POPs number in the thousands and few have been subject to environmental monitoring or epidemiological studies4. This realization was the outcome of seminal works by Howard and Muir6, Wania and Brown7, Strempel et al.8 and Scheringer et al.9, who employed predictive modelling to select potential POPs from among the c. 100,000 chemical substances produced in high volumes globally. Muir et al.4 recently performed a comprehensive evaluation of these data and assembled a list of 3421 chemicals that meet the same criteria as the Stockholm POPs, but have yet to be measured in the environment or human samples. The difference between the number of known and unknown environmental pollutants in the blood exposome may serve to reinforce the view that comprehensive exposure assessment to environmental pollutants must be considered when evaluating the risk of disease. Ideally, unknown environmental toxicants should be identified using an approach often referred to as “Nontargeted screening” (NTS)1,5,13,14,15. Blood is a reservoir of endogenous and exogenous chemicals in the body3,16. Thus, a small quantity of blood collected using dried blood spot sampling17 is an attractive matrix to sequence the exposome. However, Rappaport et al. posited that 90% of environmental pollutants with concentrations below ~0.1 μM in 50 μL of blood (Fig. 1, vertical dashed line)3 were not detectable using current analytical platforms designed for NTS, and thus a large gap in our knowledge of the exposome exists. Establishing the identities of environmental pollutants is the first critical step towards understanding their effects, which can depend on dose and may be revealed by changes in the concentrations of metabolites and biomolecules that reflect biochemical pathways18,19. However, susceptibility to a chemical exposure can also vary over the course of a lifetime such that timing of the exposure can be more important than the dose, highlighting the need for frequent exposure measurements enabled by DBS screening20.

This paper seeks to review DBS preparation and instrumental analysis; examine the critical barriers to further progress towards DBS screening of ultra-trace level contaminants; offer a forward-looking perspective as to how existing methodologies can be refined for the analysis of emerging pollutants; and highlight recent discoveries of persistent and bioaccumulating organic compounds that contribute to the blood exposome21.

2. Challenges

2.1. Blood spot sampling and storage

Dried blood spots17,22–24 are obtained by pricking a finger or heel and collecting the blood onto filter paper25. Difficulties can arise when collecting samples from neonates, manual laborers and at low temperatures due to vascular constriction26. A circular punch of varying diameter (3–12 mm) is commonly taken from a DBS that has been collected on filter paper. (Note: a DBS with a diameter of 12mm corresponds to approximately 50 μL of blood). An inherent contamination risk exists from the skin surrounding the puncture site and during the drying time, which may vary between 15 minutes and many hours. Legacy POPs, such as organochlorine pesticides, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs) unsurprisingly have shown evidence of multiyear stability in DBSs during storage, although brominated substances may undergo photolytic Br loss if exposed to light27. Blanks are essential to account for contamination during, transport and analysis28 as indoor dust is a major source of exposure to persistent organics.

Other critical challenges of DBS collection include uneven spreading of the blood drop on the substrate; blood clotting during spotting; and non-uniform drying methods. Between patients, a different volume percentage of red blood cells, i.e. haematocrit, can affect the degree to which blood spreads: blood with high haematocrit will generally spread less than blood with lower haematocrit24. Between samples from the same patient, these effects can be further amplified when multiple punches are collected from the same spot. Some studies have standardized punching procedures e.g. by punching spot centres and whole spot analysis has also been used to minimize haematocrit effects29. Capiau et al.30 have suggested that haematocrit bias may be corrected using non-contact diffuse reflectance spectroscopy.

Blood plasma, and not whole blood, is the preferred matrix for biomonitoring organic pollutants, but it is usually obtained by centrifugation, which complicates the logistics of sampling and requires larger quantities of blood. Hauser et al.31 have recently developed a dried plasma spot (DPS) device that provides a high yield of plasma in an exact volume, while also addressing issues related to haematocrit and spot-drying biases. The plasma is collected on a substrate that is enclosed, which may well prevent contamination from dust. Thus, the plasma spot approach is promising for future studies, but it needs further validation before adoption into biomonitoring studies. Moreover, the trove of archived DBS samples available for retrospective analysis will continue to drive method development aimed at addressing the limitations of sampling and analyzing DBS.

2.2. Sample analysis

Preparation of DBS samples24 is typically performed by ultrasonic extraction24. Handling and transferring small quantities of extract (20–50μL) can be laborious. Several novel methods introduced to address this issue have been applied to plasma extraction. Stir-bar sorptive extraction and similar methods that rely upon partitioning the analyte onto polymer substrates, like polydimethyl siloxane32,33 and polyethersulfone13, have proven effective for the analysis of both polar and non-polar POPs. Non-polar POP concentrations in plasma are often normalized to lipid measurements, whereas DBS measurements are typically normalized to estimated whole blood volume. Estimating the volume of blood extracted from the blood spot is not trivial. The volume of blood present in the punch of a 12mm diameter blood spot is approximately 50 μL34, depending on the type and thickness of the filter paper35,36. Sodium has been used as an indication of the plasma content of the spot and recently, Kadjo et al.37 found that ring-disk electrode conductivity could be a useful nondestructive method of reducing errors associated with spotted blood volumes.

Gas chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry (GC-HRMS) is among the most sensitive and selective techniques used for the analysis of semi-volatile organic pollutants. For the last 25 years, many biomonitoring studies have revealed a steady decline in the blood concentrations of regularly monitored legacy pollutants38, such as PCBs, organochlorine pesticides, and (mixed) halogenated dibenzo-p-dioxins39,40 and dibenzofurans (PCDD/Fs)12. GC-HRMS is an important technique for the analysis of brominated POPs, such as polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs)41 and other halogenated flame retardants that have since replaced the PBDEs. However, liquid chromatography (LC) is more appropriate for thermally labile POPs like hexabromocyclododecane (HBCDD) and polar toxicants like some perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)36,42–44. Most studies employed targeted experiments for the analysis. While the advent of Fourier Transform and Time-of-Flight mass spectrometers (FTMS and TOFMS) promises to accelerate the identification of unrecognized contaminants, these techniques are inherently less sensitive34,51.

The small blood volume present in DBS samples requires high instrument sensitivity. Batterman et al.27 explored the suitability of DBS for measuring concentrations of various pollutants by comparing the ratio of concentrations measured in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) with estimated limits of quantification. Those PCBs, PBDEs and OCPs that were not suitable for analysis in DBS were characterized by a median NHANES blood concentration ratio of <1, either due to low blood concentrations or high background contamination of the filter materials. If the volume of blood required surpasses the volume that is typically associated with one punch, the entire spot or several punches from the spot may be taken. Generally, the quantity of PCBs and PBDEs detected in a 12-mm diameter spot is on the order of 10−5 μM, whereas PFOA and PFOS concentrations are higher by one order of magnitude and dioxins are at least 10-fold lower3,20. Fetal exposure levels are much lower than those of adults43. This should be considered when assessing whether a protocol offers adequate detection limits45.

3. Future Perspectives

Published biomonitoring studies reflect the impact of pollutants that have been previously identified to be of concern. There is growing interest in investigating emerging contaminants which serve as replacements for regulated chemicals. These emerging contaminants include flame retardants such as chlorinated paraffins 46–48, dechlorane plus49,50, its analogues, and organophosphate esters (OPEs)51. Dechlorane plus has emerged as a global contaminant, having been identified in Canada, the United States, China and Europe (despite the absence of production sources in Europe)50. Chlorinated paraffins are highly complex mixtures found in human blood, but continued monitoring of this class of compounds (and their mixed halogenated analogues) will require the development of sensitive and selective analytical methods. PFOS and PFOA levels in human samples are generally declining11, but their replacements52 are ubiquitously found in commercial products, food packaging and firefighting foams. The emergence of GenX is a worrying example of the trend to replace known toxicants with structurally similar compounds. While it has not yet been found in human samples48, its presence has been detected in various environmental matrices, which suggests that GenX is widespread and continued exposure may lead to a rise in blood concentrations over time. The effect of this exposure has not yet been established. Computer modelling of chemical inventories as well as recent experimental studies of wildlife strongly suggests that there are likely hundreds more pollutants that have not yet been identified in blood4,13.

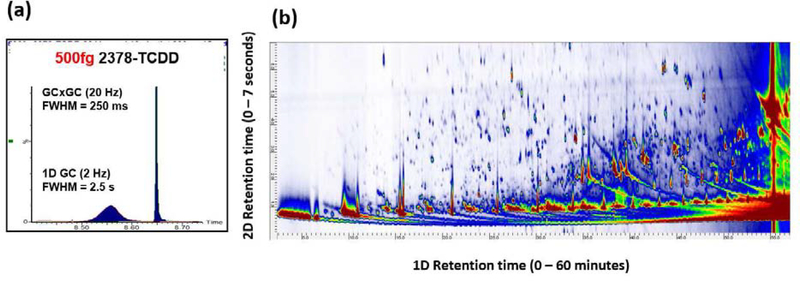

In order to make further progress, the obstacle noted by Rappaport et al.3 will need to be surmounted, viz. that 90% of environmental pollutants with concentrations below ~0.1 μM in 50 μL of blood are not identifiable using modern FTMS13 and TOFMS45 instruments. Comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography (GCxGC) and cryogenic zone compression (CZC) 12 are elegant approaches to improve separation and detection of contaminants by GC-MS. For this approach, the column effluent is trapped using a device called a modulator, and subsequently re-injected into a secondary column. During this process, the eluting peak becomes narrow, due to cryogenic focusing, and the signal is enhanced as shown in Figure 2a. The contour plot in Figure 2b is the result of multidimensional separation, which occurs when one employs a secondary column with a stationary phase that is orthogonal to that of the primary column. A similar effect may alternatively be accomplished using flow modulation53. CZC was originally conceived as a targeted approach, but Brasseur et al.49 coupled it with full-scan TOFMS. This increased sensitivity towards DP in human samples and demonstrated, for the first time, the potential to collect signal enhanced full-scan mass spectra with femtogram level concentrations. Recent work54 by the group of Schoenmakers suggest that compound detectability may be improved for LC-amenable compounds using an analogous LCxLC approach called active modulation. Though promising, the approach has not yet been applied to DBS or POPs.

Figure 2.

(a) Modulated gas chromatogram obtained from 2378-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin, resulting in 10-fold signal-to-noise (S/N) enhancement. Similar S/N enhancement can be achieved using either thermal or flow modulation; (b) Comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography (GCxGC) affords unparalleled separation of organic pollutants from in plasma.

Another challenge is related to recognizing which of the myriad signals detected from a blood spot corresponds to a suspected pollutant. It is impractical to comprehensively monitor all endogenous, exogenous and anthropogenic chemicals. One strategy is to employ suspect screening databases: Exposome-Explorer (v. 2.0) was a recently developed as an online database combining all available information (including the nature of the compound, their concentrations, study populations and analytical techniques) on exposure biomarkers and pollutants21. An alternative approach is to create analytical metrics that distinguish between those chemicals that persist and bioaccumulate from those that do not. Figure 3 displays 22,043 high-volume chemicals used in North America (in blue) along with the subset of these chemicals that are suspected of exhibiting POPs-like behaviour (in red). Since most known POPs are halogenated, it is unsurprising that the majority of suspected POPs (in red) cluster together according their respective mass-to-charge (m/z) and isotope ratios. This simple example shows that the environmental significance of a compound detected by mass spectrometry can be assessed based on MS measurements without beforehand knowledge of its structure or effect. In other words, an unknown compound detected in the region of Figure 3 that is densely populated by red dots may be assumed to have a high potential to persist and bioaccumulate. Indeed, the environmental and toxic effects of a chemical are typically prescribed by its structure, which in turn is reflected by the appearance of its mass spectrum55. Exploring these relationships may well reveal opportunities for analytical and physical chemists to collaborate with and complement a diverse range of researchers in environmental health, with the goal of sequencing the range of exposures that contribute to the exposome.

Figure 3.

(a) The compositional space of chemicals of commerce5. Suspected POPs generally cluster together in regions bound by similar mass spectrometry metrics, e.g. mass and isotopologue ratios (A+2 and A-2) relative to the most abundant isotopologue; (b) Even polyfluorinated substance can be recognized by isotope ratio measurements without a priori knowledge of their structure. This figure was reproduced from Environment International with permission.

In summary, environmental exposures that comprise the chemical exposome remain largely unknown. DBS promises to be a cost-effective, reliable approach to characterize unrecognized or unknown pollutants. But, meaningful progress towards this goal will require a transition from targeted to non-targeted methodologies that are currently under development. To our knowledge, no study to date has attempted non-targeted screening of DBS and very few pioneering NTS studies have been performed with larger blood or plasma sample quantities13,45. Online separation and pre-concentration techniques, such as CZC and GCxGC, may well be critical to addressing the challenge of identifying femtogram level pollutants in DBS.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this work was provided by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of Health Grant U01-087177-01.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- (1).Vermeulen R; Schymanski EL; Barabási AL; Miller GW The Exposome and Health: Where Chemistry Meets Biology. Science 2020, 367 (6476), 392–396. 10.1126/science.aay3164.**

- (2).Wild CP The Exposome:From Concept to Utility.International Journal of Epidemiology. 2012, pp 24–32. 10.1093/ije/dyr236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Rappaport SM; Barupal DK; Wishart D; Vineis P; Scalbert A The Blood Exposome and Its Role in Discovering Causes of Disease. Environmental Health Perspectives. Public Health Services, US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2014, pp 769–774. 10.1289/ehp.1308015.*

- (4).Muir D; Zhang X; de Wit CA; Vorkamp K; Wilson S Identifying Further Chemicals of Emerging Arctic Concern Based on ‘in Silico’ Screening of Chemical Inventories. Emerg. Contam 2019, 5, 201–210. 10.1016/j.emcon.2019.05.005.*

- (5).Zhang X; Di Lorenzo RA; Helm PA; Reiner EJ; Howard PH; Muir DCG; Sled JG; Jobst KJ Compositional Space: A Guide for Environmental Chemists on the Identification of Persistent and Bioaccumulative Organics Using Mass Spectrometry. Environ. Int 2019, 132 10.1016/j.envint.2019.05.002.*

- (6).Howard PH;Muir DCG Identifying New Persistent and Bioaccumulative Organics among Chemicals in Commerce. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44 (7), 2277–2285. 10.1021/es903383a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Brown TN;Wania F Screening Chemicals for the Potential to Be Persistent Organic Pollutants: A Case Study of Arctic Contaminants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42 (14), 5202–5209. 10.1021/es8004514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Strempel S;Scheringer M; Ng CA;Hungerbühler K Screening for PBT Chemicals among the “Existing” and “New” Chemicals of the EU. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46 (11), 5680–5687. 10.1021/es3002713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Scheringer M;Strempel S; Hukari S;Ng CA; Blepp M;Hungerbuhler K How Many Persistent Organic Pollutants Should We Expect? Atmos. Pollut. Res 2012, 3 (4), 383–391. 10.5094/APR.2012.044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (10).The Stockholm Convention http://chm.pops.int/TheConvention/Overview/TextoftheConvention/tabid/2232/Default.aspx.

- (11).Land M; De Wit CA; Bignert A; Cousins IT; Herzke D; Johansson JH; Martin JW What Is the Effect of Phasing out Long-Chain per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances on the Concentrations of Perfluoroalkyl Acids and Their Precursors in the Environment? A Systematic Review. Environmental Evidence BioMed Central Ltd; January 22, 2018, p 4 10.1186/s13750-017-0114-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Patterson DG Jr; Welch S; Turner W; Sjodin A; Focant J-F; Cryogenic Zone Compression for the Measurement of Dioxins in Human Serum by Isotope Dilution at the Attogram Level Using Modulated Gas Chromatography Coupled to High-Resolution Magnetic Sector Mass Spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography A. 2011, 1218, 3274–81.* The technique “cryogenic zone compression” is introduced. CZC was originally conceived as a targeted approach, but it now serves as the basis for on-going work on non-targeted screening of trace level organics is blood.

- (13).Liu Y; Richardson ES; Derocher AE; Lunn NJ; Lehmler H-J; Li X; Zhang Y; Cui JY; Cheng L; Martin JW Hundreds of Unrecognized Halogenated Contaminants Discovered in Polar Bear Serum. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed 2018, 57 (50), 16401–16406. 10.1002/anie.201809906.** The majority of epidiological studies focus on a small number of regulated environmental pollutants. This paper shows that hundreds of unrecognized pollutants are impacting remote ecosystems and their detection in wildlife may serve as a strong motivator to use the same novel approach on human popluations.

- (14).Rostkowski P; Haglund P; Aalizadeh R; Alygizakis N; Thomaidis N; Arandes JB; Nizzetto PB; Booij P; Budzinski H; Brunswick P; Covaci A; Gallampois C; Grosse S; Hindle R; Ipolyi I; Jobst K; Kaserzon SL; Leonards P; Lestremau F; Letzel T; Magnér J; Matsukami H; Moschet C; Oswald P; Plassmann M; Slobodnik J; Yang C The Strength in Numbers: Comprehensive Characterization of House Dust Using Complementary Mass Spectrometric Techniques. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2019, 411 (10). 10.1007/s00216-019-01615-6.*

- (15).Rappaport SM Implications of the Exposome for Exposure Science. Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology January 2011, pp 5–9. 10.1038/jes.2010.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Guthrie R; Susi A A simple phenylalanine method for detecting phenylketonuria in large populations of newborn infants. Pediatrics; 1963, 32, 338–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Labine L; Simpson MJ The use of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and mass spectrometry (MS)-based metabolomics in environmental exposure assessment. Current Opinion in Environmental Science & Health, 2020, 15, 7–15. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Aristizabal-Henao JJ; Ahmadireskety A; Griffin EK; Da Silva BF; Bowden JA Lipidomics and environmental toxicology: Recent trends, Current Opinion in Envrionmental Science & Health, 2020, 15, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Axelrod D; Burns K; Davis D; von Larebeke N “Hormesis” – An inappropriate extrapolation from the specific to the universal, International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health, 2004, 10, 335–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Neveu V; Eve Nicolas G; Salek RM; Wishart DS; Scalbert A Exposome-Explorer 2.0: An Update Incorporating Candidate Dietary Biomarkers and Dietary Associations with Cancer Risk. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48 10.1093/nar/gkz1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Zakaria R; Allen KJ; Koplin JJ; Roche P; Greaves RF Advantages and Challenges of Dried Blood Spot Analysis by Mass Spectrometry Across the Total Testing Process. EJIFCC 2016, 27 (4), 288–317. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Meesters RJW; Hooff GP State-of-the-Art Dried Blood Spot Analysis: An Overview of Recent Advances and Future Trends. Bioanalysis. Future Science Ltd London, UK September 21, 2013, pp 2187–2208. 10.4155/bio.13.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Freeman JD; Rosman LM; Ratcliff JD; Strickland PT; Graham DR; Silbergeld EK State of the Science in Dried Blood Spots. Clin. Chem. 2018, 64 (4), 656–679. 10.1373/clinchem.2017.275966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Ostler MW; Porter JH; Buxton OM Dried Blood Spot Collection of Health Biomarkers to Maximize Participation in Population Studies. J. Vis. Exp 2014, No. 83, e50973 10.3791/50973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Su X; Carlson BF; Wang X; Li X; Zhang Y; Montgomery JLP; Ding Y; Wagner AL; Gillespie B; Boulton ML Dried Blood Spots: An Evaluation of Utility in the Field. J. Infect. Public Health 2018, 11 (3), 373–376. 10.1016/j.jiph.2017.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Batterman S; Chernyak S Performance and Storage Integrity of Dried Blood Spots for PCB, BFR and Pesticide Measurements. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 494–495, 252–260. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.06.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Ma WL; Gao C; Bell EM; Druschel CM; Caggana M; Aldous KM; Louis GMB; Kannan K Analysis of Polychlorinated Biphenyls and Organochlorine Pesticides in Archived Dried Blood Spots and Its Application to Track Temporal Trends of Environmental Chemicals in Newborns. Environ. Res. 2014, 133, 204–210. 10.1016/j.envres.2014.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Zheng N; Yuan L; Ji QC; Mangus H; Song Y; Frost C; Zeng J; Oise Aubry A-F; Arnold ME “Center Punch” and “Whole Spot” Bioanalysis of Apixaban in Human Dried Blood Spot Samples by UHPLC-MS/MS. J. Chromatogr. B 2015, 988, 66–74. 10.1016/j.jchromb.2015.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Capiau S; Wilk LS; De Kesel PMM; Aalders MCG; Stove CP Correction for the Hematocrit Bias in Dried Blood Spot Analysis Using a Nondestructive, Single-Wavelength Reflectance-Based Hematocrit Prediction Method. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90 (3), 1795–1804. 10.1021/acs.analchem.7b03784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Hauser J; Lenk G; Ullah S; Beck O; Stemme G; Roxhed N An Autonomous Microfluidic Device for Generating Volume-Defined Dried Plasma Spots. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91 (11), 7125–7130. 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b00204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Boggess AJ; Rahman GMM; Pamukcu M; Faber S; Kingston HMS An Accurate and Transferable Protocol for Reproducible Quantification of Organic Pollutants in Human Serum Using Direct Isotope Dilution Mass Spectrometry. Analyst 2014, 139 (23), 6223–6231. 10.1039/c4an00851k.*

- (32).Lin EZ; Esenther S; Mascelloni M; Irfan F; Godri Pollitt KJ The Fresh Air Wristband: A Wearable Air Pollutant Sampler. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett 2020, 7 (5), 308–314. 10.1021/acs.estlett.9b00800. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Batterman SA; Chernyak S; Su F-C Measurement and Comparison of Organic Compound Concentrations in Plasma, Whole Blood, and Dried Blood Spot Samples. Front. Genet 2016, 7 (APR), 64 10.3389/fgene.2016.00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Hewawasam E; Liu G; Jeffery DW; Gibson RA; Muhlhausler BS Estimation of the Volume of Blood in a Small Disc Punched From a Dried Blood Spot Card. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2018, 120 (3). 10.1002/ejlt.201700362. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Poothong S; Papadopoulou E; Lundanes E; Padilla-Sánchez JA; Thomsen C; Haug LS Dried Blood Spots for Reliable Biomonitoring of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs). Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 655, 1420–1426. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.11.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Kadjo AF; Stamos BN; Shelor CP; Berg JM; Blount BC; Dasgupta PK Evaluation of Amount of Blood in Dry Blood Spots: Ring-Disk Electrode Conductometry. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88 (12), 6531–6537. 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b01280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Provatas AA; Kolakowski SL; Sternberg FH; Stuart JD; Perkins CR Analysis of Dried Blood Spots for Polychlorinated Biphenyls and Organochlorine Pesticides by Gas Chromatography Coupled with Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Lett. 2019, 52 (9), 1379–1395. 10.1080/00032719.2018.1541994. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Fernando S; Jobst KJ; Taguchi VY; Helm PA; Reiner EJ; McCarry BE Identification of the Halogenated Compounds Resulting from the 1997 Plastimet Inc. Fire in Hamilton, Ontario, Using Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography and (Ultra)High Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48 (18). 10.1021/es503428j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Organtini KL; Myers AL; Jobst KJ; Cochran J; Ross B; McCarry B; Reiner EJ; Dorman FL Comprehensive Characterization of the Halogenated Dibenzo-p-Dioxin and Dibenzofuran Contents of Residential Fire Debris Using Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography Coupled to Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2014, 1369 10.1016/j.chroma.2014.09.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Gravel S; Lavoué J; Labrèche F Exposure to Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) in American and Canadian Workers: Biomonitoring Data from Two National Surveys. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 631, 1465–1471. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Ma W; Kannan K; Wu Q; Bell EM; Druschel CM; Caggana M; Aldous KM Analysis of Polyfluoroalkyl Substances and Bisphenol A in Dried Blood Spots by Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2013, 405 (12), 4127–4138. 10.1007/s00216-013-6787-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Bach CC; Bech BH; Brix N; Nohr EA; Bonde JPE; Henriksen TB Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances and Human Fetal Growth: A Systematic Review. Critical Reviews in Toxicology. Informa Healthcare; January 1, 2015, pp 53–67. 10.3109/10408444.2014.952400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Workman CE; Becker AB; Azad MB; Moraes TJ; Mandhane PJ; Turvey SE; Subbarao P; Brook JR; Sears MR; Wong CS Associations between Concentrations of Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Human Plasma and Maternal, Infant, and Home Characteristics in Winnipeg, Canada. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 249, 758–766. 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Zheng MY; Li XH; Zhang Y; Yang YL; Wang WY; Tian Y Partitioning of Polybrominated Biphenyl Ethers from Mother to Fetus and Potential Health-Related Implications. Chemosphere 2017, 170, 207–215. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.11.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Yuan B; Muir D; MacLeod M Methods for Trace Analysis of Short-, Medium-, and Long-Chain Chlorinated Paraffins: Critical Review and Recommendations. Analytica Chimica Acta. 2019, pp 16–32. 10.1016/j.aca.2019.02.051.*

- (46).Li T; Wan Y; Gao S; Wang B; Hu J High-Throughput Determination and Characterization of Short-, Medium-, and Long-Chain Chlorinated Paraffins in Human Blood. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51 (6), 3346–3354. 10.1021/acs.est.6b05149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Schinkel L; Bogdal C; Canonica E; Cariou R; Bleiner D; McNeill K; Heeb NV Analysis of Medium-Chain and Long-Chain Chlorinated Paraffins: The Urgent Need for More Specific Analytical Standards. Environmental Science and Technology Letters. American Chemical Society; December 11, 2018, pp 708–717. 10.1021/acs.estlett.8b00537. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Brasseur C; Pirard C; L’homme B; De Pauw E; Focant J-F Measurement of Emerging Dechloranes in Human Serum Using Modulated Gas Chromatography Coupled to Electron Capture Negative Ionization Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2016, 30 (23), 2545–2554. 10.1002/rcm.7745.** This is the first example of coupling CZC to a full-scanning mass spectrometer. This increased sensitivity towards DP in human samples and demonstrated, for the first time, the potential to collect signal enhanced full-scan mass spectra with femtogram level concentrations.

- (49).Brasseur C; Pirard C; Scholl G; De Pauw E; Viel JF; Shen L; Reiner EJ; Focant JF Levels of Dechloranes and Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers (PBDEs) in Human Serum from France. Environ. Int 2014, 65, 33–40. 10.1016/j.envint.2013.12.014.**

- (50).Hou M; Shi Y; Jin Q; Cai Y Organophosphate Esters and Their Metabolites in Paired Human Whole Blood, Serum, and Urine as Biomarkers of Exposure. Environ. Int 2020, 139, 105698 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Gebbink WA; van Leeuwen SPJ Environmental Contamination and Human Exposure to PFASs near a Fluorochemical Production Plant: Review of Historic and Current PFOA and GenX Contamination in the Netherlands. Environment International 2020, 105583 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105583.** The emergence of GenX is a worrying example of the trend to replace known toxicants with structurally similar compounds. While it has not yet been found in human samples, its presence has been detected in various environmental matrices and in some cases above guideline levels.

- (52).Jobst K.; Seeley JV; Ladak A; Reiner EJ; Mullin L Enhancing the Sensitivity of Atmospheric Pressure Ionization Mass Spectrometry Using Flow Modulated Gas Chromatography. The Column 2018, 14 (6), 23–28. An alternative approach to CZC.*

- (53).Baglai A; Blokland MH; Mol HGJ; Gargano AFG; van der Wal S; Schoenmakers PJ Enhancing Detectability of Anabolic-Steroid Residues in Bovine Urine by Actively Modulated Online Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Liquid Chromatography – High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 1013, 87–97. 10.1016/j.aca.2017.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Fernando S; Green MK; Organtini K; Dorman F; Jones R; Reiner EJ; Jobst KJ Differentiation of (Mixed) Halogenated Dibenzo- p -Dioxins by Negative Ion Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88 (10), 5205–5211. 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]