Abstract

Are those individuals who were formerly placed on the back wards of the state mental hospital drifting to the back alleys of the community? There is some evidence to suggest that the erosion of the state hospitals system has led communities to develop new methods of excluding their mentally ill. Viewing inclusion and exclusion efforts as a function of social distance, we have reviewed empirical data on the nature of attitudinal response to the mentally ill.

Implications of public attitudinal response to this group are considered with respect to providing the necessary incentives for inclusion. Taking California as an example, we also attempt to conceptualize and classify actual community response patterns in the light of what appears to be the development of new formal and informal mechanisms of exclusion.

The assumption that the mentally ill are peremptorily excluded from their local communities has been the basis of much research in the area of social deviance during the past two decades.1–3 Though this assumption has been contested by some,4 its application to the notion that the mental institution is the major instrument of exclusion has almost become an accepted fact.

One of the primary goals of the community mental health movement has been to combat exclusion trends. It has stressed that the treatment outside of an institution would help maintain the person’s integration in the community or facilitate his reintegration into the community.

However, to the extent that the placement of individuals in mental institutions has been the major vehicle of exclusion from the local community and has been functional in the community social system—a possibility often alluded to by deviance theorists3,5—one would expect that the closing of these institutions would lead to a new system of exclusion.

Currently several states have moved toward an increasing commitment to the care of the mentally ill outside of mental hospitals in their local communities. This move seems to be resulting in some states in the erosion of the state hospitals’ system, as a mechanism for the care of the mentally ill. In California, for example, the state which has taken a lead in the nation in the provision of local care for the mentally ill, three state hospitals have been closed in recent years, with other closures indicated in the future.6(p865)

The commitment of California to community mental health programs is reflected in several facts (these facts may also illustrate the decline of the state hospitals system):

1. The California Community Mental Health Services Act of 1968 represents a major overhaul of the California Mental Services System.7,8 It created a single system of care based on local responsibility for the treatment and care of mentally ill people. In keeping with the concept of a single system of care, “The community mental health programs have become the controlling element with respect to state hospital utilization”6(p863) Although state hospitals can be used, it is the prerogative of the local community to decide how to use them. Funds are allocated by the state to the local, county program according to the county mental health plan.

2. Only four years ago the appropriation for the state hospitals for the mentally ill in California was almost four times the amount appropriated for the community mental health programs. In the 1972-1973 budget community mental health programs’ appropriation exceeded by about one third the appropriation for the state hospitals, for which the appropriation has been declining continuously since the Community Mental Health Services Act of 1968 has been in effect in California. Total state’s appropriation to local programs for the current fiscal year (1972/1973) is four times greater than it was just four years ago, ie, in the 1968/1969 fiscal year.

3. In the 1972-1973 proposed budget it is stated that the primary program objective of the state “continues and furthers a dramatic departure from traditional state hospital based psychiatric care.6(p859) “Twenty-four hour hospitalization is the least acceptable form of treatment. Locally provided outpatient care is the most acceptable.”6(p862)

4. In the last ten years the resident population in the state hospitals for the mentally ill has been declining from over 35,000 in 1962 to less than 10,000 in 1972.6,9

Contrary to the decline of resident population in state mental institutions, admission to both county as well as state hospitals for the mentally ill have been constantly rising.10

From an annual admission to state mental institutions of about 28,000 in 1961-1962 fiscal year the number rose to 44,000 ten years later. Apparently while the number of incidents of diagnosed mental illness have been rising, the length of stay in inpatient service units have been declining.

Given these facts, not much sophistication is needed to conclude that there are now in California and probably in other states many more people defined as mentally ill residing in the community than in the past. Mentally ill are returned now at a higher rate and much faster to the community. Thus, many of the ideas and the promises advanced by the community mental health movement are now being put to the test in California. Among them are the questions of the continued integration and reintegration of the mentally ill in the community.

It should be noted, lest we overstate the unity of purpose in the community mental health movement, that many of its strong supporters express doubt as to the extent to which reintegration of the seriously mentally disordered would occur even without the development of new exclusion trends. To these individuals community care for the mentally ill is a goal indicated for humanitarian rather than treatment purposes.11

If the closing of the state hospitals does in fact raise the possibility of the development of a new system of exclusion, we are faced with the problem that little if any work has been done on the dynamics associated with inclusion or exclusion in a given community. While Garfinkel12 described the conditions necessary for a successful degradation ceremony (ie, those activities engaged in by members of a social group which are involved in the process of excluding a member), little information is available as to the interaction of factors leading to the use of this social mechanism in a given social system with respect to a given social group. In the past, it has simply been assumed that the process is an all or none or a categorical phenomenon.

Coser13 distinguished a position for the deviant other than complete acceptance or rejection—ie, one in which he is sheltered by the group structure and tolerated within the group. Dentler and Erickson14 note that in this position deviants become critical reference points within the group. It is the contention of this paper that the inclusion or exclusion phenomenon is not categorical in character but that there are different degrees of inclusion or exclusion which can be placed on a social distance continuum.

Attitudes Toward the Mentally Ill

It is primarily in the work on attitudes toward the mentally ill4,15,16 that references to differing degrees of inclusion or exclusion in certain groups are mentioned. During the past 15 years several attempts have been made to assess public attitudes toward mental disorder. A large number of these studies have tried to ascertain the degree of social distance between the general public and the mentally ill.1,2,5,16–27 Though using different designs, each of the studies has made use of a similar dependent measure, ie, a social distance scale including the following types of agree/disagree statements:

1. I would not hesitate to work with someone who had been mentally ill.

2. I would be willing to sponsor a person who had been mentally ill for membership in my favorite club or society.

3. If I owned an empty lot beside my house, I would be willing to sell it to a former mental hospital patient.

4. I would be willing to room with someone who had been a patient in a mental hospital.

5. We should strongly discourage our children from marrying anyone who had been mentally ill.

6. I can imagine myself falling in love with a person who had been mentally ill.17(P231)

The results of these studies are not presented in directly comparable form but, when the scores of five of the studies of the relationship between mental illness and response tendency on a social distance scale are standardized on a 6-point scale of acceptance/rejection (a score of 6 implying total acceptance and a score of zero implying total rejection) the average amount of acceptance taken across studies is 3.26. The Table gives mean acceptance scores for each of the studies. The mean study scores would seem to indicate that attitudes are in fact becoming slightly more accepting toward the mentally ill. However, the actual cutting point on the scale for the average respondent is still between: “selling a lot beside his house to a former mental hospital patient” and “rooming with such a patient.” This finding also generalizes to the middle-class black community.24 The average person will admit the former action but not the latter.

Acceptance of Mentally Ill as Indicated by Mean Scores on a 6-Point Social Distance Scale

| Year | 1971 | 1967 | 1967 | 1963 | 1957 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Bentz & Edgerton*17 | Dohrenwend & Chin-Shong†16 | Yamamoto & Dizney27 | Phillips‡1 | Cumming & Cumming§5 |

| Mean score | 3.92 | 3.54 | 3.17 | 2.68 | 3.03 |

Estimate of the average score for those considered mentally ill by the Bentz and Edgerton sample.

Based on score estimates derived by assuming a perfect Guttman scale and using data from Dohrenwend’s sample of a crosssection of the Washington Heights population.

Based on estimate of the means for mentally ill individuals treated by a psychiatrist or in a mental hospital.

Since before and after comparisons were not significantly different in this study, all four mean scores (ie, for the two villages sampled) were taken as independent estimates of the true mean and were averaged to obtain the above score.

Assuming that all that is needed is the willingness to live near a former patient to enable his entry into the community, we can still see that a large group will not tolerate this amount of contact and that the possibility of any greater contact than this would be viewed with rapidly increasing distaste. This fact is perhaps best illustrated by the recent public response to the Eagleton affair.

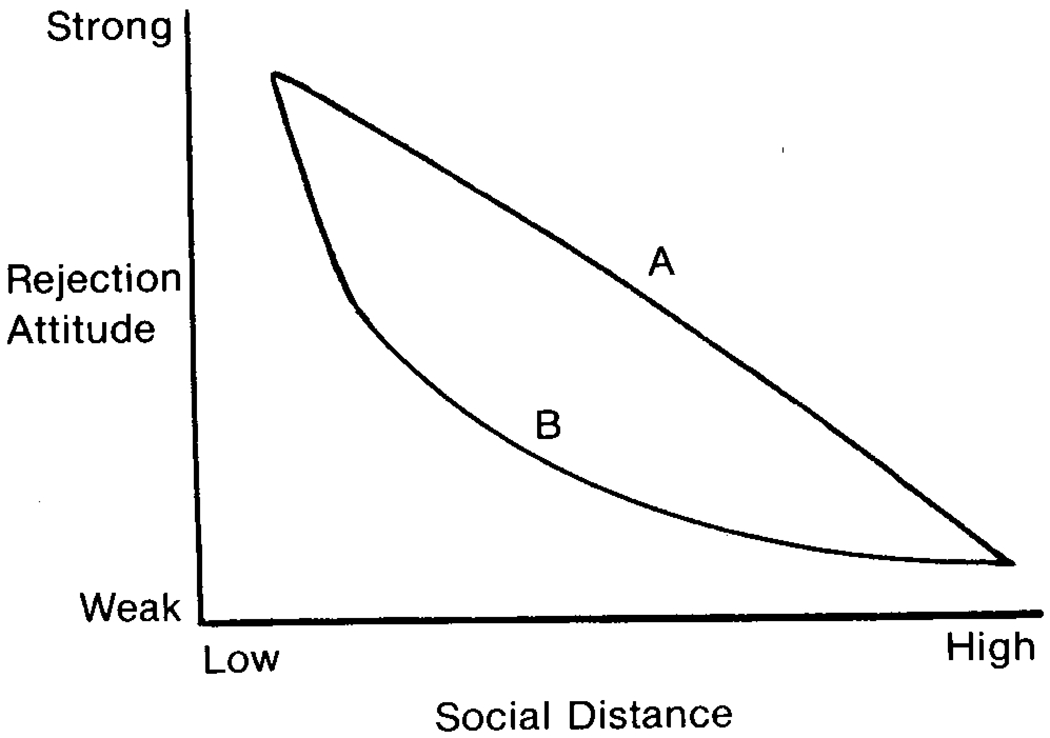

If we plot the results of some of the attitudinal studies of social distance so that the horizontal axis represents the degree of social distance and the vertical axis represents increasing levels of rejection, the form of the curves obtained approximate a straight line, in the most conservative populations, and a hyperbola in the most liberal groups16,26 (Figure 1). Thus, even assuming the most liberal population, these curves would indicate that as one draws closer to the goal of inclusion one will have to invest a rapidly increasing amount of incentives to overcome rejection trends.

Rejection response curve of conservative and liberal populations over varying degrees of social distance. A, Conservative population, and B, liberal population.

It took a great deal of economic incentives for the communities in California to accept the mental health reform and consequently a higher degree in inclusion of the mentally ill. Although the community mental health programs in Calfiornia have been in existence since 1957, it was not until the state assured the communities the reimbursement of 90% of the cost of the care of the mentally ill that they accepted the new mental health reform.7(p419,423)

The current situation in California illustrates not only the need for positive incentives to provoke community inclusion responses but also what might be a budding of a new system of exclusion. Given the previously mentioned attitudinal studies one might speculate that individuals coping with the actual fact of living next door to a former mental patient and encountering the possible threat of even closer contact would not prove as agreeable as they were in the hypothetical situation in which the attitudinal data were collected.

Incentives for Inclusion

If we mean by the term inclusion the physical existence of one in a certain social system (with no reference at this point to any degree of social proximity) then we can state that California has been able to achieve a much higher degree of inclusion of the mentally ill in the community than in the past, and than that achieved in other states.

There are many factors that may explain the shift in the population dynamics of the mentally ill. Those factors can be considered as incentives which brought about the change. They have operated to a greater or lesser degree throughout the past 15 years. They include: changes in attitudes; legal changes; economic incentives provided to communities for the care of their mentally ill; economic and political benefits for the state to transfer the responsibility to local communities; increased availability of resources—eg, especially federal, to provide income maintenance and medical treatment for the mentally ill in the community; availability of new treatment technologies, especially, the psychoactive drugs; increased availability and utilization of alternate care facilities in the community for population groups that used to be sent to the mental institution, eg, the senile aged; increased availability and utilization of outpatient facilities as well as community mental health centers; and political and professional rewards which were associated with the shift in the mental health service system. These factors, which may represent only part of the reinforcing stimuli for the inclusion trends, are highly interrelated. It is beyond the scope of this paper to assess the relative contribution of each of these factors. It would indeed be an interesting question to study the relative strength of these incentives, the pattern of their operation, and the timing of their introduction.

The California Mental Health Services Law of 1968 may be regarded as both a cause and a consequence of the changes in the pattern of care for the mentally ill in California. At present, however, it should be stated that this law makes it very difficult for any community to use the state hospital system as a mechanism for exclusion. Physical existence in a certain community, however, does not necessarily lead to social inclusion. Furthermore, a man can be living in a certain geographical community and still be excluded from it, physically, socially, or both.

The focal question is: Has the erosion of the state hospital system and the actual encounter of many communities with increased social proximity with the mentally ill brought about a creation of a new system of exclusion, and what are the patterns and the dynamics associated with this system?

Patterns associated with the exclusion phenomenon have been observed as operating at the local community level. Exclusion at this level seems to be a more subtle process than could be detected in the old system which was based on a state hospital, remote from the community.

In considering the process of exclusion at this level we will attempt to look into the formal and informal mechanisms employed. By formal mechanisms we refer to the use of alternative legal and administrative procedures that seem to accomplish the exclusion and to the use of rules and regulations that serve the same function. Informal mechanisms are referred to here as the various group pressures reflected in neighbors’ attitudes and various kinds of bureaucratic maneuverings that serve the function of exclusion.

Physical Exclusion.—

Physical exclusion refers to actual attempts to remove the person from the geographical locality or block his entry into it. It also relates to the process of removing the mentally ill into geographical pockets within a local unit, eg, into nonresidential areas and into the ghettoes. A person may live in a geographical community but still be excluded from certain neighborhoods and become secluded in specified areas.

Physical removal can be achieved by both formal or informal mechanisms. Let us first deal with the use of formal mechanisms, removal through the use of the penal code system.

Exclusion by Formal Mechanism: Use of Alternative Legal Routes.—

California’s mental health reform, which became effective in 1969, blocked the routes of exclusion through the use of indefinite civil commitment. A person in California can be committed under the penal code if: (1) he is charged with a criminal offense and is found not mentally competent to stand trial,28 and (2) he is convicted of crimes but found not responsible because of insanity.28 The state is also required to provide treatment-oriented service for persons who have committed sex offenses and are found to be mentally disordered.

One of the indications of the system’s adaptations which seems to run against the original intention of the legislature is the increase in the use of the penal code to commit people to mental institutions. There is not much research in this area; however, there is some evidence that there is a substantial increase in the use of the penal code in order to admit people into mental institutions. Recent research, which attempted to examine the impact of the mental health reform of 1969 in California (initiated by the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act-henceforth, LPS) on the number of admissions by penal code commitments to state hospitals for the mentally ill, concluded the annual admission rates for the state as a whole as well as for the four specific counties studied were higher for the period studied than for the corresponding period before the mental health law went into effect.29 The causal relationship between this increase and the new law (LPS) cannot be established unequivocally. However, the study report indicates that after LPS went into effect in July 1969, “the superior courts of at least some counties began to use commitment by the penal code as an effective admissions procedure for securing long-term care for such patients.28(p1) The study concludes that the legislation (of LPS) might have been partially responsible for the rise in the number of such admissions.

The increase of about 15% of the governor’s budget for 1972-1973 fiscal year over the 1970-1971 allocation for care of people committed by the penal code may be another indication for the increase in the use of the penal code for committing people to mental institutions. Neither the inflation nor the increase of California’s population30 can serve as a sufficient explanation for the 15% increase of expected expenditures for committed people under the penal code, in the last two years.

This may be some evidence of the system’s adaptation to the closure of civil commitment resulting from the enactment of LPS, by the use of alternative legal routes to commit people. Many who in the past might have been committed indefinitely, now return much faster to the community—some because they refuse to accept voluntary treatment and some because there was nothing in their behavior that would persuade the court to extend their involuntary treatment beyond the certified 14 days. There is also some evidence that local mental health services may not admit as easily for inpatient service as the state hospital used to do. There are now incentives for discouraging local mental health services from using state hospitals. At times there are people in the community that may become a local nuisance, but there is no way to exclude them to the mental institution. Law enforcement officers, under pressure to deal with a community’s undesirable elements often report their frustration. Some resorted to using the alternative solution! They arrest the mentally ill and charge them with a minor crime they had committed, and in some cases the court commits those arrested to a mental institution via the penal code.

Other formal mechanisms for physical exclusion may operate as well. We do not yet know to what extent types of people previously committed to mental institutions are now found in jails convicted of crimes or awaiting trial. Professionals in several California counties report an increasing tendency to resort to the use of criminal designations to handle troublesome people, many of whom had been previously handled by the state mental institutions. Some law enforcement officers see a great increase in the number of former mental patients who now are dealt with by the law enforcement agents.31 Without placing any value judgment on what is better (or what is a lesser of two evils), Szasz32 may find in California a system which is much closer to his ideals than it used to be. However, since the law in fact deals with people differentially, convictions of some people might be based not so much on the seriousness of the crime as on the desire to exclude them from the community.

Exclusion by Informal Mechanisms: Ghettoization.—

Financial and administrative requirements, as defined in the California Mental Health Law, define the community as the county. It is not within the scope of this paper to discuss the issue of what is a community. However, if people are not allowed to live in certain neighborhoods because of legal and/or group pressures, their residence within the boundaries of a geographically defined community does not mean that they are truly included in that community.

The process of ghettoization of the mentally ill, ie, their seclusion in certain neighborhoods, may be in part a result of economic conditions. The current level of the public assistance provided to them can, at best, let them subsist in the rundown neighborhoods like the ones so often found in the downtown area of many American cities.

Economic reasons do not seem to be a sufficient explanation for the phenomenon of ghettoization of the mentally ill. Many of these people move or drift to certain areas because their previous efforts to live in other neighborhoods fail. There is evidence of neighborhood pressures upon citizens who wanted to open and operate board and care facilities for the mentally ill. In one such case a man wanted to buy a house for his family and four expatients and was threatened by other people in the neighborhood. He gave up the idea and said: “I know I am entitled to live there but that is not the issue. My wife and kids, that’s what’s most important” (The Vista Press, Dec 1, 1971).

Since the road back for these expatients to the state hospitals wards has been made extremely difficult, they probably drift to the ghetto areas. The recent increase in the number of former mental patients in some neighborhoods in California counties has been observed and reported by professionals as well as lay people. If future systematic study substantiates this phenomenon, it would define one type of physical exclusion of the mentally ill that takes place within the boundaries of the geographically and administratively defined community.

Exclusion by Blocking Entrance: Formal and Informal Mechanisms.—

The upsurge of alternative care facilities in the communities has been resisted various ways: for example, zoning laws, city ordinances and regulations, and various informal approaches such as neighborhood pressures and bureaucratic maneuvering.

Many of these local communities base their resistance on the fact that the present level of care in the board and care homes in the community is not satisfactory, nor has the local community been given sufficient time and money to develop appropriate alternatives. We have no dispute with many of these claims. The fact remains, however, that in the past when the number of expatients in the community was low and alternative routes for rejects were open, the communities did not object so vehemently to the low level of care. It is only now, with diminished access to the state hospital system and the unavailability of other negotiated arrangements with other counties and neighborhoods, that we see the furor in some communities about the phenomenon and quality of care of the mentally ill within the community. It is the recognition of the lack of alternatives for routing the mentally ill “out” that suddenly revealed the low quality of care.

The furor raised and currently still raging over the closing of Agnews State Hospital and what was viewed by the San Jose community as the parallel development of a “little Agnews”—ie, a concentration of discharged mental patients in boarding houses surrounding the State University Campus—is one example of community resistance and fears related to an anticipated “mass invasion of mental patients” (The Mercury of San Jose, Nov 16, 1971).

Use of City Ordinances and Regulations.—

Local communities use legal measures to block the entrance of the mentally ill into the community. Although the state’s law requires the community to provide care and treatment for the mentally ill, it cannot prevent communities from exercising their local responsibilities. Communities have been using legal methods, some justified as safety needs, to deal with the situation of the upsurge of local facilities for the mentally ill in the communities.

One city demanded that every new board and care home operator obtain a permit from the fire marshal and then, a week later, announced a moratorium, suspending the authority of the fire marshal to issue permits for a specified time that was later extended (San Jose News, Dec 14, 1971). Thus, those who operated boarding homes for the mentally ill in the community did not have enough time to get the required permits nor could anyone start a new boarding home operation in that community. Another mechanism has been the use of stricter definitions than that of the state of what should be considered as a family for zoning purposes. The result of this action is restricting the mentally ill from certain residential zones. There is accumulating evidence of the use of other types of ordinances such as, fire safety requirements, building codes, etc, that may serve us as an example of exclusion trends operating now in the communities.7

Use of Legal or Bureaucratic Maneuvering.—

By maneuvering we refer to efforts taken through legal action or by the bureaucracy in which it tries to manipulate the system so as to create a preferred outcome without officially stating its goal.

The action mentioned above taken by the city council placing certain demands and then technically making it impossible for people to meet those demands is an example of maneuvering. Demanding a payment of high fees for use permits for board and care homes is another example of maneuvering or manipulating the system. The institution of a fee was mainly to discourage potential local operators of facilities for the mentally ill from going into business. In one city an ordinance was passed requiring prospective operators of a board and care facility to apply for a use permit and to pay a fee. The city could also demand expensive structural repairs in accordance with current building codes, and executing the repairs did not assure the permit. However, once a person simply applied, he took the risk of having his house condemned for non-compliance with current standards! The importance of this risk in influencing the decision to apply for a permit should not be minimized. Many of the potential board and care operators live in old homes and are in a low-income bracket.

Stalling, red tape, threats of legal action are also used in bureaucratic maneuvering. Bureaucracies may send forms back and forth for minor technical problems. Counties have been known to withhold approval of public assistance grants, although it was illegal, and thus caused difficulties and delay in placement programs in the communities for released mental patients. A request for legal opinion with the hope that the issue will not be resolved for some time (San Jose News, Dec 14, 1971 and June 1, 1972) probably served the same purpose of maneuvering the system in such a way as to block the mentally ill from the community.

Incentives, Risks, and Social Exclusion.—

Physical inclusion is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for the integration of the mentally ill in the community. The question of the social exclusion of the mentally ill in the new framework of community mental health is in much need of research. While the processes leading to social rather than physical exclusion are subtle and hard to assess, there is some evidence that may reveal the dynamics operating here.

The development of alternative care facilities for the mentally ill in the community has economic incentives in it for various groups and cannot be solely attributed to the anti-institutionalization movement with its research base and ideological commitments.

Caring for the mentally ill in the community has become a big business with money from many sources—federal, state, and county—in a variety of community programs providing jobs and income to many individuals. New nursing homes, board and care homes, hotel rooms, and other patient care facilities have been established; many community physicians are providing medical services to persons who in the past were cared for in the state hospital. In fact, new state and federal policies and resources have made the group formerly institutionalized in mental institutions, economically attractive for local individuals and groups. There is no doubt that this fact contributed to the facilitation of some physical inclusion of people, who were formerly hospitalized, in the community.

These economic incentives that were positive from one aspect had some unintended consequences, consequences that might have been contributing in part to a process fostering social exclusion. There are some economic risks involved in caring for the mentally ill in the community. Approaches taken to deal with these risks or aversive stimuli are at times contrary to programs and goals of integrating the mentally ill in the community.

Ideally, exmental patients who live in a board and care home, for example, would use it as a temporary arrangement and will move into an independent living situation. In reality, however, the people and organizations who provide the alternative care facilities have an incentive which is quite contrary to this goal. Being paid by the number of filled beds, many of the board and care operators are inclined to develop a stable population in their homes. Apte33 reports the occurrence of a similar phenomenon in his work on halfway houses in England. The dynamics which operated in the large mental institutions are operating in the community as well!

The desire to maintain a stable population in the board and care home is further affected by the community sensitivity to the former mental patients. Board and care operators have learned that the tolerance level of the community is lower than that of a remote hospital. Allowing an expatient to try it out in the community involves a risk of community reaction that might cause demands for removing that person from the home, if not closing down the facility. The economic implications to the home operator are obvious. The social implications may cause a great deal of inconvenience as well. It is not surprising that one finds a quite docile population in many of the board and care homes in the community. Lamb and Goertzel,34 in a study of such discharged mental patients, note that some of these homes resemble long-term hospital wards isolated from the community. One wonders whether a change in the economic incentive system will be sufficient to change this trend. It may be that community fears and uneasiness in relation to the mentally ill is even a stronger explanation than the lack of economic incentives of the fact that we find the mentally ill secluded within the community.

The dynamic of social exclusion reflected in the desire to maintain a docile, stable population in alternative care facilities may be aided by other social processes. It has been pointed out that the relationships between health workers, patients, and the pharmaceutical industry influences to some extent the way psychoactive drugs are used. The setting, the social environment, and the characteristics of the patients influence drug use and drug administration.36,37

We are all aware of the value of psychoactive drugs in the treatment of the mentally ill but we must not forget that these drugs, and especially their sedative effects, may be exploited by the social environment, and they may be functional in meeting the interest of the community to maintain a docile population in the alternative care facilities. This, of course, contributes to forces of social exclusion.

Studies dealing with the impact and use of psychoactive drugs have indicated the possibility of overuse of certain agents in some instances regarding certain patient populations. (Research currently being conducted on a patient population by M. Rapaport, J. Silverman, and H. Hopkins at Agnews State Hospital has indicated in preliminary findings that medication is being used too much in certain instances). Psychoactive drug administration and drug use by psychiatric patients in the community is yet to be looked into. It seems to us that forces of social exclusion play into the overuse of drugs for a segment of the population which was once being excluded in mental institutions. If our assumptions about the dynamics operating in this case are true, we may find that psychoactive drugs are overused for aggressive patients who may cause trouble in the neighborhoods while possibly under used with the withdrawn depressive patients. Reducing or eliminating these problems may be counter to forces of social exclusion.

From Back Wards to Back Alleys

The back wards of the state hospitals became the symbol for the decay of the state hospital system where people rejected by the community would be kept for years. In part, it has been claimed that the state hospital system was established and maintained as a mechanism of social exclusion.

The ideology of the community mental health movement and the erosion of the state hospitals system, specifically in the example of California which was used in this paper, raised the hope among many people that the trend of exclusion would be reversed by new ones, of inclusion. In fact, California’s vigorous effort to reverse the exclusion trend has resulted in bringing more people diagnosed as mentally ill back to the community.

There are, however, many indications that the dynamics of exclusion may still be operating. Physical exclusion by removal of the mentally ill from certain residential areas or by blocking their entrance is an indication of community resistance to the integration of the mentally ill. Communities have used various tactics both formal and informal in the manifestation of this resistance. We have also noted that in many cases where the mentally ill are in the community they are socially excluded either by mechanisms that foster a docility or by forces that encourage ghettoization. Some may claim that much of the evidence mentioned in this paper proves at best that the system is having transitional difficulties and that those are temporary. We certainly hope that those who make that claim are right. The questions dealt with in this paper in an exploratory manner need much further research. It should indeed be determined if the dynamic of exclusion which kept the mentally ill in the back wards of the hospital will relegate them to the back alleys of the community.

Contributor Information

Uri Aviram, School of Social Work, Tel Aviv University, Israel.

Steven P. Segal, School of Social Welfare, University of California, Berkeley.

References

- 1.Phillips D: Rejection: A possible consequence of seeking help for mental disorders. Am Sociolog Rev 28:963–972, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Phillips D: Rejection of the mentally ill: The influence of behavior and sex. Am Sociolog Rev 29:679–687, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheff T: Being Mentally Ill: A Sociological Theory. Chicago, Aldine: Publishing Co, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemkau PV, Crocetti GM: On rejection of the mentally ill. Am Sociolog Rev 30:579–580, 1965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cumming E, Cumming JC: Closed Rand: An Experiment in Mental Health Education. Cambridge, Mass, Harvard University Press, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 6.California State Governor’s Budget, 1972-1973. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aviram U: Mental Health Reform and the Aftercare State Service Agency, unpublished dissertation University of California, Berkeley, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bardach E: Skill Factor in Politics. Berkeley, Calif, University of California Press, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 9.California Mental Health Progress. Sacramento, Calif, California Department of Mental Hygiene, March 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 10.California Mental Health: A Study of Successful Treatment. Sacramento, Calif, California State Human Relations Agency, March 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown GW, et al. : Schizophrenia and Social Care. London, Oxford University Press, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garfinkel H: Conditions of successful degradation ceremonies. Am J Social 41:420–424, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coser L: Continuities in the Study of Social Conflict. New York, Free Press, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dentler R, Erickson K: The functions of deviance in groups. Soc Problems 7:98–107, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lemkau PV, Crocetti GM: An urban population’s opinion and knowledge about mental illness. Am J Psychiatry 118:692–700, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dohrenwend B, Chin-Shong E: Social status and attitudes toward psychological disorder. Am Sociolog Rev 32:417–433, 1967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bentz K, Edgerton JW: The consequences of labeling a person as mentally ill. Soc Psychiatry 6:29–33, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blizard PJ: The social rejection of the alcoholic and the mentally ill in New Zealand. Soc Sci Med 4:513–526, 1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bord RJ: Rejection of the mentally ill: Continuities and further developments. Soc Problems 18:496–509, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Myer JK: Attitudes towards mental illness in a Maryland community. Public Health Rep 79:769–772, 1964. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phillips D: Public identification and acceptance of the mentally ill. Am J Public Health 56:755–763, 1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phillips D: Identification of mental illness: Its consequences for rejection. Community Mental Health J 3:262–266, 1967a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phillips D: Education, psychiatric sophistication, and the rejection of the mentally ill help-seekers. Sociolog Quart, 8:122–132, 1967b. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ring SI, Schein L: Attitudes toward mental illness and the use of caretakers in a black community. Am J Orthopsychiatry 40:710–716, 1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schroder D, Ehrlich D: Rejection by mental health professionals: A possible consequence of not seeking appropriate help for emotional disorders. J Health Soc Behav 9:222–232, 1968. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whatley C: Social attitudes toward discharged mental patients. Soc Problems 6:313–320, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamamoto K, Dizney H: Rejection of the mentally ill: A study of attitudes of student teachers. J Counseling Psychology 14:264–268, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 28.California State Penal Code, No. 1370; No. 1026. [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Impact of the Lanterman-Petris Short, Act on the Number of Admissions by Penal Code Commitment to State Hospitals for the Mentally Ill: Statistical Bulletin. Sacramento, Calif, California Department of Mental Hygiene, Bureau of Biostatistics, June 8, 1970, vol 13, No. 12. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Population Estimates for California Counties. Sacramento, Calif, California Department of Finance, August 16, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Link AR, McMaster L: CSEA Legal Brief Presented in the California Superior Court. 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szasz T: Law, Liberty and Psychiatry. New York, Macmillan Co, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Apte R: Halfway Houses: A New Dilemma In Institutional Care. London, G. Bell, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lamb HR, Goertzel V: Discharged mental patients: Are they really in the community. Arch Gen Psychiatry 24:29–34, 1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lennard HL, et al. : Mystification and Drug Misuse. San Francisco, Jossey Bass, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eisen MB: Effects of ward tension on the quality and quantity of tranquilizer utilization. Ann New York Acad Sci 67:746–757, 1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parry HL: Use of Psychotropic Drugs by U.S. Adults. Public Health Rep 83:799–810, 1968. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]