Abstract

Context

Nurses who care for patients with life-limiting illness operate at the interface of family caregivers (FCG), patients, and prescribers; they are uniquely positioned to guide late-life medication management, including challenging discussions related to deprescribing questionably beneficial medications.

Objectives

To describe nurses’ perspectives about their role in hospice FCG medication management.

Methods

Secondary qualitative analysis of nurse interviews from a study exploring views on medication management and deprescribing for advanced cancer hospice patients. Original participants were drawn from 3 hospice agencies and their referring hospital systems in New England. Nurses were asked to describe current practices of medication management and deprescribing for patients transitioning to hospice, and to evaluate a pilot tool to standardize reviews of hospice medication appropriateness. We used content analysis to compare reports of existing practice to the theoretical needs of hospice FCGs based on Lau’s framework for hospice caregiver medication management needs.

Results

Content analysis of 10 nursing interviews from home hospice, inpatient hospice and primary care settings revealed that nurses were receptive to a standardized approach for comprehensive medication review upon transition to hospice that considered patients goals, and responded favorably to opportunities to discuss medication discontinuation with FCGs and prescribers. Effective framing for discussions included focusing on reducing harmful and non-essential medications, and reducing caregiver burden.

Conclusions

Nurses who care for hospice-eligible and enrolled patients are willing to discuss deprescribing with FCGs and prescribers, especially when conversations are framed around education about medication harms and their impact on quality of life.

Keywords: hospice, polypharmacy, deprescribing, cancer, family caregivers

INTRODUCTION

Over 1.3 million Americans aged 65 years and older receive hospice services annually and 45% are cared for at home.1 These patients are prescribed an average of 10–12 medications daily2–4 and have progressively declining organ function that increases their risk of drug-related harm.5,6 Furthermore, many take questionably beneficial medications7–9 until death while simultaneously being prescribed an increasing number of end-of-life (EOL) symptom management drugs.4 This changing combination of medications contributes to burden, stress and confusion for family caregivers (FCG) who are responsible for patient medication management and administration.10,11

Family (informal) caregivers are defined as “any relative, partner, friend or neighbor who has a significant personal relationship with, and provides a broad range of assistance”.12 Home hospice is a particularly challenging setting for FCGs because they are responsible for complicated medication administration tasks that are usually reserved for licensed healthcare professionals.13 An estimated 44 million adults, mostly women, provide this informal (i.e. unpaid) care.14 They often feel inadequately prepared for this responsibility15 and have fears about doing something wrong.13,15

Hospice nurses are critical teachers and supporters of these tasks.16 Yet, in one report, fewer than 60% of home hospice patients in the U.S. received assistance in medication management (i.e., assisting with medication administration, dispensing the correct dosages, and establishing and following a dosage schedule) from their hospice agencies.17 Prior research provides a conceptual understanding of key domains to help caregivers with medication-related tasks: establish trust, provide medication information, encourage self-confidence, offer medication assistance, and assess understanding and performance.18 Yet, there is no consensus on clinical guidelines defining the hospice nursing role when supporting caregivers with medication management19 nor standardized tools to support end-of-life care medication management for hospice nurses and prescribers.20 Hospice approaches to facilitating medication management are therefore left to individual agencies and providers, raising challenges about how to effectively to maintain the quality of remaining life for patients and how to best support their caregivers.

Nurses who care for patients with advanced, life-limiting illness operate at the interface of family caregivers, patients, and prescribers and are in a unique position to support FCGs before, during, and after the transition to hospice. However, little is known about nurse perspectives regarding end-of-life medication management. Moreover, discussions with FCG’s and patients about deprescribing questionably beneficial medications, while defensible based on patient risks and marginal benefits, can be challenging for nurses caring for FCG’s and patients who were told that they must take certain medications “for life”.

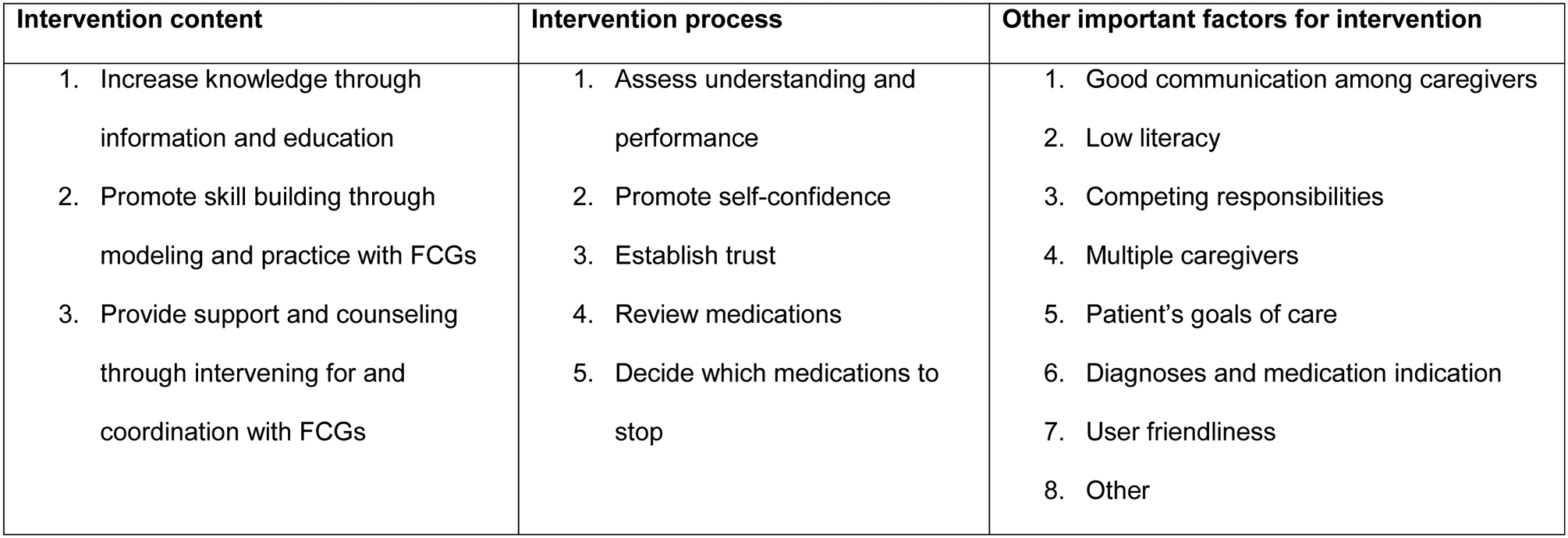

To describe nurses’ perspectives about their role in FCG medication management and support, including medication review and deprescribing, we analyzed qualitative interviews of nurses who care for older adults with life-limiting illness. Nurses were asked to describe their current practice of medication review, deprescribing, and medication management support upon transition to home hospice, and to evaluate a pilot tool to standardize a hospice medication appropriateness review. We mapped nurses’ responses to Lau’s framework for family caregiver medication management needs in home hospice.18,21 Lau’s framework identifies domains recommended for inclusion in interventions to support home hospice medication management, namely education, skill building, coordination support, and simplification of regimens (i.e. deprescribing).10,18 (Figure) Our findings provide insight into the design of hospice interventions to support FCG medication management at the end-of-life.

FIGURE.

Conceptual Framework for Intervention to Support FCG Medication Management (adapted from Lau10,18)

METHODS

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

Study Design, Participant Eligibility, Recruitment, and Data Collection

We conducted secondary qualitative analysis of semi-structured interviews from a study that explored views on medication management and deprescribing for advanced cancer hospice patients. In the parent study, we conducted interviews with home hospice patients with advanced cancer, their FCGs, and physicians and nurses who provide care for such patients in different clinical settings, including home hospice, inpatient hospice, palliative care, oncology, and primary care. Original participants were drawn from 3 hospice agencies and their referring hospital systems in New England. Eligible nurses included home hospice nurses, inpatient hospice nurses, primary care case coordinators. Nurses were asked to describe their current practice of medication review, deprescribing, and medication management support upon advanced cancer hospice patient transition to home hospice, and to evaluate a pilot tool to standardize hospice medication appropriateness reviews. The pilot tool is available in the online supplemental materials.

Data Analysis

Transcripts of nurse interviews were analyzed using a two-step approach to: 1) first identify responses relevant to the current practice of medication review in hospice and views on the need for an intervention to support medication review; and then 2) to map these responses to Lau’s framework for FCG hospice medication management.

Specifically, in the first step, all transcripts were broadly coded by two Bachelor’s level investigators (BN; TC) using an inductive content analytic approach, which is appropriate in the presence fragmented knowledge about the phenomenon in question,22 such as is the case with medication prescribing in home hospice. Inductive content analysis allows themes to arise from the data. Using this approach, investigators independently reviewed 3 transcripts from each category of patient/caregiver, nurse, and physician interviews; these were independently coded to identify themes and develop a coding schema related to current practice of medication review in hospice, care coordination, perception of the need for a standardized intervention, communication and decision-making processes. The coding schema was then compared for overlap and discrepancies. After team discussion to reconcile discrepancies, we used consensus coding to analyze all remaining transcripts.

Once this was completed, we conducted a second-level analysis of nurses’ transcript sections that were relevant to the current practice of medication review in hospice and nurses’ views on the need for an intervention to support medication review. Two nurse-investigators with expertise in hospice care (SDM; MC) used deductive content analysis to map these interview sections, identified in the initial coding, to a conceptual framework by Lau that informs the development of an intervention to support family caregiver medication management needs in home hospice. In this way, we compared nurses’ reports of existing practice to the theoretical needs of home hospice patients and their FCGs.18,21

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Participants in this analysis included 6 home hospice nurses, 3 inpatient hospice nurses, and one nurse medical home coordinator for a primary care practice (Table 1). Most respondents (70%) had been in their current position for over 5 years.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Characteristics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 10 | 100 |

| Practice Setting | ||

| Home Hospice | 6 | 60 |

| Inpatient Hospice | 3 | 30 |

| Outpatient Practice | 1 | 10 |

| Time in Current Position | ||

| < 2 years | 2 | 20 |

| 2–5 years | 1 | 10 |

| > 5 years | 7 | 70 |

| Education | ||

| RN | 3 | 30 |

| BSN | 7 | 70 |

Current Practice of FCG Support and Medication Review

Of the domains described in the modified Lau framework, we noted that nurses described parts, but not all, of each Content, Process, and Important Factors domain. [Figure]

Education and Skill Building for FCGs

Regarding intervention content, nurses more commonly discussed providing education than skill building, and within education, nurses mentioned increasing knowledge and providing education for symptom knowledge as part of current clinical practice, more often than they mentioned providing education to increase medication knowledge.

Well we look at their diagnosis, look at what they’re taking, and make sure there aren’t any duplications of medications, or if there’s something like a type of medicine that we could add to help improve their symptoms and their comfort, we would make recommendations to the doctor. And, of course it’s ultimately the doctor’s order. And of course we discuss the med changes with the family too…

When nurses discussed promoting skill building, they primarily focused on symptom management, and less so on medication administration and organization.

In regards to the first time you’re seeing a patient, is doing a full pain assessment which includes determining and assessing various factors. Pain location site. Factors that exacerbate it. Are there are any patterns to it. What have they used … what are they using currently to try and control it, not only medication but other measures. And what have they used in the past. And what was effective and what was not effective. What type of scheduling do they use? Are they only using it as needed? And then we also look at are there any cultural or spiritual or whatever personal beliefs in regards to utilizing pain … medications

Support and Counseling for FCGs

Simplifying Medication Regimens as Support.

Nurses spoke about simplifying medications as a means of supporting patients and their FCGs: “I personally eliminate as many meds as I can because meds can get overpowering.” Nurses also acknowledged the importance of medication management interventions that helped to coordinate care with other hospice caregivers, including prescribers, in order to streamline communication for FCGs.

We talk about which medications, what they’re currently taking, what it was prescribed for, why they’re asking to stop it and then run it by the doctor

What did not appear spontaneously in the interviews about current models of care as described in the Lau framework was education about addressing medication administration, namely technical knowledge, challenges about when patients are resistant to treatment, and skills about medication organization.

Medication Review as Support.

Consistent with the Lau framework’s recommendations for processes of care, nurses frequently described medication review as a key component of the process for medication support and deprescribing, and often described how they considered which medications to select as candidates for discontinuation.

I go through the list and a lot of times I’ll look at non-essentials first and after I look at the non-essentials I talk to the family, explain why they need to be on them, why they don’t need to be on them. If the family agrees then I go to the doctor and I make recommendations to DC the non-essential medications. And then a lot of times I’ll wait a couple of weeks and see how they’re doing on the medications that are essential before I make any changes…

Trust and Communication for Deprescribing Timing.

Nurses also touched on the importance of establishing trust and good communication by listening and understanding the goals of the family and patient:

It’s not a matter of just stopping; it’s a matter of looking at the big picture. Where is the patient at this particular time? What’s going to benefit this patient to have comfort and dignity and peace, and make it less stressful for the family?

Some nurses highlighted the importance of communication and the challenge of having medication management conversations with FCGs specifically related to deprescribing. Challenges with communication were felt to be complicated, sometimes attributed to literacy issues, but other times attributed to a global difficulty engaging in this type of conversation:

…ability of the patient to comprehend, and the family, whether it’s illiteracy or stress level or medication prejudices, some folks just don’t want to even listen.

Nurses’ skills in building trust, listening, and soliciting goals of care were all felt to be important to inform the subtleties of the process of supporting FCG medication, and to be important considerations for the implementation of any intervention to address FCG needs.

Although less frequent, the nurses also discussed indications for deprescribing and the importance of distinguishing between “hospice” meds and ”non-hospice” meds”:

Usually if somebody’s got medications we’re not pursuing stopping them unless we see signs that they’re not able to tolerate them for whatever reason. Or, if someone starts to have difficulties swallowing oftentimes what I’ll be doing is … and they’re not ready to let go, we start with the comfort meds … make sure you get those down first and then if they are starting to have difficulty you know you’ve provided the comfort meds.

Other FCG Support Tasks.

We found little to no discussion about the intervention process involving an assessment of the understanding and performance of the FCG tasks. Of the framework’s “other important factors” that occur in the current practice model of hospice medication support and deprescribing, assessing goals of care emerged as the most frequently cited important factor.

…certainly we would consider what the patient’s goals are to begin with.

I mean you come at it from the patient’s point of view and their understanding of what’s going on and then from the provider’s point of view in thinking about … really seriously thinking about what their reasons for everything on this list is and also comes to a meeting place where there can be discussion about what’s happening.

While Lau’s framework also identifies the need for an intervention to address competing responsibilities of the FCGs or coordinating multiple caregivers, these themes did not spontaneously emerge in our nurse interviews.

Need for an Intervention to Standardize Patient-Centered Medication Review

The interview text that described the nurses’ perception of a need for an intervention included responses to reviews of pilot standardized patient centered medication review tools. [Online Supplemental Material] In general, nurses agreed that having a standardized approach to medication review would be welcome and was needed:

I would love to come up with something that says, we got the meds, this is how long they have to live, this is where they’re at and these are their goals of care. And, somehow in the back end try to figure out these are the meds most likely to be causing their difficulty swallowing or nausea or whatever. And then like, and then, yeah, spit out some recommendations.

While one nurse stated that she liked it “as is”, most nurses stated that the format and approach of any standardized tool for medication review needs to be user friendly. As presented in the parent study, the pilot review tool was “a lot of words.” The tool asked for input from nurses, patients/FCGs, pharmacists and physicians, but nurses pointed out that “I think it’d be hard to get the hospice nurse, the physician, everyone to have access to one sheet of paper.” Eliciting goals of care in paper form from patients was also noted to be difficult and time consuming.

You have to be really helpful to the patients because it’s a lot of words. So as far as them picking an answer, I think I wouldn’t just present this to somebody to read and have them pick A, B, C or D. I think people would probably frown on too many thoughts and too many concepts sometimes.

Yeah, I don’t have time for that right now so it’s never going to get done.

Nurses also commented on the format, with some wanting a paper tool, and others wanting a computerized tool: “I would prefer paper because I think that if we even made copies and gave it to patients and families they could use it” or “Electronic, yes, definitely”. What was generally agreed upon, however, was the need to have a comprehensive medication list. “I think as long as you could get every medication that somebody takes on that list, it would help, because it’s difficult to get.” There was also agreement that the medication assessment should be made user friendly for patients and families as a tracking and education tool: “[if you] make copies and gave it to patients and families they could use it.”

In terms of intervention content, nurses were more likely to state that educational materials would be good for patients and their FCGs: “To say, when your body starts doing this, you really don’t need this, this, this, this, and kind of educate them as to … we don’t have like hospitals do, we do not have like educational pamphlets regarding medications” They also felt this would also help nurses when questions might become redundant: “when I did visiting nursing and I had a whole list of meds like this, I would just go through them with people and try to teach them as best I could. And then the next time you go, go over them again.” There was also a recommendation for education about the burden of medications: ”I think it would also help as another educational tool about benefit and burden of a specific medication.”

There was less discussion about the need for an intervention that would provide skill building and modeling for help with medication organization. Some nurses suggested that an intervention should help with support and coordination with FCGs, and should help coordinate with other members of the hospice team.

I feel like we tie things together because we’re in the home and we see what bottles they have, and they might have forgotten to tell one doctor about medication.

In terms of the process for an intervention to support FCG medication management, again the process of medication review was frequently cited, along with having indications for deprescribing and selecting which medications to deprescribe. Having a process to assess FCG understanding and skills was not often mentioned, nor was having a process to establish trust. However, understanding patients’ goals of care was commonly mentioned. The nurses also felt it is important to try to understand potential barriers to having medication support and deprescribing conversations, whether they are due to low literacy, stress, or other reasons: “[recognize their] ability of to comprehend … whether it’s illiteracy or stress level or med prejudices…”.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to map nurses’ current practices and perceived needs for medication review at hospice admission, including their suggestions for a future standardized intervention to an existing conceptual framework. According to Lau’s framework, these practices and needs include education, skill building, simplification of regimens, and coordination support.10,18 In this paper, we focused on the perceptions of nurses regarding current practice and the need for an intervention to support FCGs medication management. We found that at transition into hospice care, nurses regularly review medications, sometimes with an eye toward deprescribing but more often to obtain a complete and accurate list of current medications. We also found that the educational support FCGs receive focuses on symptom management, but less on understanding medication administration and/or organization skills. Nurses are open to a standardized approach to conducting patient-centered medication review on hospice transition.

While all nurses stated that they regularly review medications of patients transitioning to hospice, there was variation in what this meant to different nurses. While most nurses typically focus on obtaining a complete and accurate list of current medications, some play a more active role in reviewing appropriateness of medications and facilitating communication about deprescribing as a way of reducing medication burden and supporting FCGs. These findings are reminiscent of prior studies suggesting that the approach to hospice FCG medication support is inconsistent.17 This is important because we also know that variation in the execution of important medical decision making and procedures can contribute to suboptimal health care delivery.23,24 Thus, our findings support the need to develop a standardized approach to supporting FCGs home hospice medication review and management.

Our findings indicate that nurses agree with the need for a standardized approach to conducting patient-centered medication review on hospice transition. The overarching aim of such an intervention is to standardize the approach of the healthcare team to reviewing medication appropriateness based on the patient’s goals of care, indications for use (i.e. chronic preventive or symptomatic medications), complexity and burden of management and administration by FCGs.11,25 Unfortunately, since Lau introduced his framework, there is still no consensus on clinical guidelines defining hospice clinical roles in supporting FCG medication management, nor are there standardized tools and education in end-of-life care for health-care professionals.

Our study suggests that the design of tools to facilitate the nurses’ role in supporting FCGs with medication management needs to be user-friendly, computerized, printable in a form that can be used for FCG education, and inclusive of information about the burdens and benefits of medications. The intervention tools could also include space to document patient and FCG’s goals for care and medication use, since nurses often use this in their holistically based care plan. Finally, any intervention needs to be implemented in the context of a trusting relationship built upon strong communication and listening skills, since these medication-related conversations about management, and in particular about deprescribing longstanding medications now deemed less useful, can be stressful for both patients and their FCGs.

Our findings should be considered in light of several limitations. First, all of the study participants practiced in the Northeast, limiting the generalizability of the findings to other patient populations. Further, while a strength of the study was the inclusion of nurses from non-home hospice settings to inform the picture of the transition to hospice care, the number of non-hospice nurses was limited.

In summary, our findings provide initial insights to guide the design of interventions to standardize tools and education in end-of-life care for health-care professionals, demonstrating the need for user friendly and succinct approaches to conducting medication reviews at the time of hospice admission, and paving the way for the development and testing of a standardized approach that could be used in various settings when considering the usefulness of medications at hospice admission. Nurses would benefit from skills training on engaging patients in conversations about the need and appropriateness of medications, their benefits and risks, and the goals of FCGs and patients. Skills training should also focus on the acceptance of end-of life care and the relative benefits of stopping less necessary medications. Such standardized approaches and skills training will ultimately improve the quality of life of seriously ill patients and reduce caregiver stress and burden.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We are grateful to the participating hospice programs, their staff, and their clientele for their generous contributions of time for participating in this study.

Funding: This work was supported by the American Cancer Society/National Palliative Care Resource Center [grant number: PEP-11-263-01-PCSM].

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Nothing to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.NHPCO. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization NHPCO’s Facts and Figures. 2017:1–9. https://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/Statistics_Research/2017_Facts_Figures.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.McNeil MJ, Kamal AH, Kutner JS, Ritchie CS, Abernethy AP. The Burden of Polypharmacy in Patients Near the End of Life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dwyer LL, Lau DT, Shega JW. Medications That Older Adults in Hospice Care in the United States Take, 2007. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015:n/a–n/a. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Culshaw J, Kendall A, Wilcock A. Off-label prescribing in palliative care: A survey of independent prescribers. Palliat Med. 2013, 27(4):314–9. doi: 10.1177/0269216312465664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pretorius RW, Gataric G, Swedlund SK, Miller JR. Reducing the risk of adverse drug events in older adults. Am Fam Physician. 2013, 87(5):331–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinman MA, Hanlon JT. Managing medications in clinically complex elders: “There’s got to be a happy medium”. JAMA. 2010;304(14):1592–1601. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raijmakers NJ, van Zuylen L, Furst CJ, et al. Variation in medication use in cancer patients at the end of life: a cross-sectional analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2013. 21(4):1003–11. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1619-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fede A, Miranda M, Antonangelo D, et al. Use of unnecessary medications by patients with advanced cancer: Cross-sectional survey. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1313–1318. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0947-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tjia J, Briesacher B a, Peterson D, Liu Q, Andrade SE, Mitchell SL. Use of medications of questionable benefit in advanced dementia. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(11):1763–1771. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joyce BT, Lau DT. Hospice experiences and approaches to support and assess family caregivers in managing medications for home hospice patients: a providers survey. Palliat Med. 2013;27(4):329–338. doi: 10.1177/0269216312465650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tjia J, Ellington L, Clayton MF, Lemay C, Reblin M. Managing Medications During Home Hospice Cancer Care: The Needs of Family Caregivers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;50(5):630–641. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Center on Caregiving. Family Caregiver Alliance. www.caregiver.org. Published 2017.

- 13.Lau DT, Berman R, Halpern L, Pickard AS, Schrauf R, Witt W. Exploring factors that influence informal caregiving in medication management for home hospice patients. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(9):1085–1090. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGuire DB, Grant M, Park J. Palliative care and end of life: The caregiver. Nurs Outlook. 2012;60(6). doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chi NC, Demiris G, Pike KC, Washington K, Oliver DP. Pain management concerns from Hospice family caregivers’ perspective. Am J Hosp Palliat Med. 2018. 35(4):601–611. doi: 10.1177/1049909117729477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sekse RJT, Hunskar I, Ellingsen S. The nurse’s role in palliative care: A qualitative meta-synthesis. J Clin Nurs. 2018. 27(1–2):e21–e38. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlson MDA, Morrison RS, Holford TR, Bradley EH. Hospice care: What services do patients and their families receive? Health Serv Res. 2007;42(4):1672–1690. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00685.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lau DT, Joyce B, Clayman ML, et al. Hospice Providers’ Key Approaches to Support Informal Caregivers in Managing Medications for Patients in Private Residences. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43(6):1060–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Care NCP for QP. National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, Third Edition https://www.hpna.org/multimedia/NCP_Clinical_Practice_Guidelines_3rd_Edition.pdf. Published 2013. Accessed January 18, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campling N, Richardson A, Mulvey M, et al. Self-management support at end of life: Patient’s, carers’ and professionals’ perspectives on managing medicines. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018, 76, 45–54. doi:org/10/1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lau DT, Kasper JD, Hauser JM, et al. Family caregiver skills in medication management for hospice patients: a qualitative study to define a construct. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2009;64(6):799–807. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbp033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2007;62(1):107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wennberg JE. Unwarranted variations in healthcare delivery: implications for academic medical centres. Br Med J. 2002;325(April):961–964. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7370.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wennberg DE. Variation in the delivery of health care: The stakes are high. Ann Intern Med. 1998;128(10):866–868. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-128-10-199805150-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Payne S, Turner M, Seamark D, et al. Managing end of life medications at home-accounts of bereaved family carers: A qualitative interview study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2015;5(2):181–188. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2014-000658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.