Abstract

Background

Mobilization of intensive care patients is a multi-professional task. Aim of this study was to explore how different professions working at Intensive Care Units (ICU) estimate the mobility capacity using the ICU Mobility Score in 10 different scenarios.

Methods

Ten fictitious patient-scenarios and guideline-related knowledge were assessed using an online survey. Critical care team members in German-speaking countries were invited to participate. All datasets including professional data and at least one scenario were analyzed. Kruskal Wallis test was used for the individual scenarios, while a linear mixed-model was used over all responses.

Results

In total, 515 of 788 (65%) participants could be evaluated. Physicians (p = 0.001) and nurses (p = 0.002) selected a lower ICU Mobility Score (-0.7 95% CI -1.1 to -0.3 and -0.4 95% CI -0.7 to -0.2, respectively) than physical therapists, while other specialists did not (p = 0.81). Participants who classified themselves as experts or could define early mobilization in accordance to the “S2e guideline: positioning and early mobilisation in prophylaxis or therapy of pulmonary disorders” correctly selected higher mobilization levels (0.2 95% CI 0.0 to 0.4, p = 0.049 and 0.3 95% CI 0.1 to 0.5, p = 0.002, respectively).

Conclusion

Different professions scored the mobilization capacity of patients differently, with nurses and physicians estimating significantly lower capacity than physical therapists. The exact knowledge of guidelines and recommendations, such as the definition of early mobilization, independently lead to a higher score. Interprofessional education, interprofessional rounds and mobilization activities could further enhance knowledge and practice of mobilization in the critical care team.

Introduction

Early mobilization is defined according to the German S2e guideline “positioning and early mobilization in prophylaxis or therapy of pulmonary disorders” as mobilization within 72 hours after admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) [1]. Due to its proven benefits, such as shorter duration of mechanical ventilation [2], improved functionality [3], and possibly shorter duration of delirium [4–8], while being safe [9] and cost-effective [10], early mobilization is a highly recommended but hardly implemented therapy during intensive care.

Implementation of early mobilization is recommended in an inter-professional approach [5, 11–14]. In practice, professionals frequently report barriers to early mobilization, such as sedation, consciousness disorders, or hemodynamic or respiratory instability [15]. Interestingly, different professions report different barriers to early mobilization, e.g. nurses often report hemodynamic instability on continuous renal replacement therapy as barriers, while physical therapists report neurological impairments or inability to follow commands [16–24]. Hence, different professions may estimate the mobility of ICU patients differently.

In this investigation, ten ICU-specific case scenarios, which included several clinical barriers for mobilization (e.g. mechanical ventilation with an endotracheal tube, delirium or continuous renal replacement therapy), were assessed by different professions of the critical care team. This study aimed to compare the estimation of mobilization capacity of ICU patients among professions.

Materials and methods

The assessment was based on a previous evaluation using patient scenarios [23], and was reported in accordance with recommendations for the conduction of online surveys [25]. All participants were informed about the study and its voluntary, anonymous approach, as well as the approximate time required to complete the questionnaire. No incentives were offered. The study was approved by the ethical committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the Technical University of Munich (approval 116/17 from 26.04.2017), which waived the requirement for a written informed consent.

Design

The survey was designed as an online questionnaire containing 23 pages, 32 questions, and 161 items, resulting in a mean of 5 items per question (see S1 Appendix). The questionnaire included in summary 29 multiple-choice questions, two questions with multiple answers and one question with a ranking scale of 0 to 100. The survey covered 5 sections: a) workplace data (self-reported expert status of participants, the definition of early mobilization according to a German guideline [1], presence of protocols, implementation of protocols from 0 (none) until 100 (fully implemented)), b) explanations of terms used in the patient scenarios (Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale, pain, delirium, strength), c) 10 patient scenarios (Table 1 and S1 Appendix), d) barriers to mobilization (three most important barriers out of 20), and e) socio-demographic data (age, work experience, profession, country).

Table 1. Case scenarios characteristics.

| Variable / Scenario | 1a | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Running Title | Awake & stable | Comatose & MV with ETT | Awake & MV with ETT | Delirium & MV with TC | Awake & NIV | CRRT & MV with ETT | Delirium & MV with ETT | Pulmonary unstable & MV with TC | Vasopressors & MV with TC | Awake & SAB |

| Consciousness | +c | comatose | + | Hypoactive Delirium | + | + | Hyperactive Delirium | (+) | Hypoactive Delirium | SAB. ø ICP |

| Breathing | spontaneous | ETT | ETT | TC | NIV | ETT | ETT | TC | TC | spontaneous |

| Strength | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Respiratory stability (FiO2)b | 0.36 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.45 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.21 |

| Hemodynamic stability | + | - | + | + | + | + | + | + | - | + |

| Lines | + | + | + | + | + | CRRT | + | + | + | + |

| Days on ICU | 5 | 10 | 4 | 8 | 20 | 16 | 4 | 9 | 6 | 5 |

a Scenario 1 is a reference example, representing full mobility. Grey cells represent the scenario’s main characteristic.

b FiO2 values of the scenarios are presented.

c + = condition is given, e.g. patient has full consciousness, full strength, is stable, has all routine lines (central venous line, arterial catheter, stomach tube, bladder tube); (+) = reduced condition, e.g. reduced strength;— = unstable condition, e.g. pulmonary stability requiring 80% oxygen, reduced hemodynamic stability, requiring norepinephrine or dobutamine.

Abbreviations: CRRT Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy, ETT Endotracheal Tube, FiO2 Fraction of Oxygen, ICU Intensive Care Unit, SAB Subarachnoid Bleeding, TC Tracheal Cannula.

Participants were free to move back and forth while answering the questionnaire, but had no access to overall results. The questionnaire was self-developed and tested on 19 critical care team members in a pilot phase, after which only minor revisions were undertaken. The results of the pre-test were not included in this analysis. All authors approved the final version.

Participants

The call for participants was published and advertised via the German Network for Early Mobilization, as well as other related professional networks in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. In order to maximize participation, two reminders were emailed to all members of the network after 2 and 4 weeks. The assessment was administered with SurveyMonkey.

Case scenarios

We developed ten patient scenarios, including different levels of consciousness and responsiveness [11, 16], different airway devices or level of ventilation support (endotracheal intubation, tracheostomy cannula [26], spontaneous breathing, non-invasive or mechanical ventilation [27]), as well as organ support, such as continuous renal replacement therapy [16], vasopressors [28] or high fraction of oxygen [26] (Table 1 and S1 Appendix). All patient scenarios indicated that this was not to be the first mobilization attempt, as first mobilizations usually require a greater level of caution and flexibility while determining the degree of mobilization that a patient can tolerate [29].

Outcome measures

The primary outcome for each patient scenario was the ICU Mobility Scale (IMS), from 0 to 10: 0 = none (lying in bed), 1 = sitting in bed, exercises in bed, 2 = passively moved to chair (no standing), 3 = sitting on the edge of the bed, 4 = standing, 5 = transferring from bed to chair, 6 = marching in place (at bedside), 7 = walking with the assistance of 2 or more people, 8 walking with the assistance of 1 person, 9 = walking independently with gait aid, 10 = walking independently without a gait aid [30]. Participants were asked to estimate the mobilization capacity on the ICU Mobility Scale for each patient scenario in realistic conditions, and to estimate the number of required ICU staff necessary to carry it out.

Data analysis

Data was analyzed with SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp; New York, NY, USA), and missing data was treated as such. Minimal requirements for inclusion in the analysis were professional details and completion of at least one patient scenario. Nominal and categorical data are reported as numbers and percentages. Due to the non-normal distribution of metrical data, these are reported as median and interquartile range (IQR). Hypotheses were calculated using Kruskal Wallis, based on a double-sided alpha = 0.05. Wilcoxon test was used for a posthoc analysis, with p-values adjusted using the Bonferroni method. A linear mixed-effects model using R Version 3.5.1 (Vienna, Austria) was used for the calculation, using all scenarios and their categorization with the outcome of mobility. Factors regarding scenarios (consciousness, breathing, strength, respiratory stability, hemodynamic stability, lines as described in Table 1) and ICUs (availability of protocols) were categorized and combined with age, work experience and geographical area of the participants. As each participant answered ten scenarios, participants were used as a random factor in the model.

Results

Participants

The scenarios were answered by 788 participants, whereas 65% (n = 515) completed the minimum requirements. Participants answered all ten scenarios in 92% (n = 475), nine scenarios in 7% (n = 35) and eight scenarios in 1% (n = 5) of cases.

The majority of the participants (72% (n = 370)) were nurses, 77% (n = 395) of participants worked in Germany, 39% (n = 202) were aged between 35–48 years and 26% (n = 135) had 5–10 years of work experience (Table 2). Only 34.8% (n = 176) of participants could answer the question regarding the definition of early mobilization in accordance to the German guideline correctly. Physical therapists perceived themselves as experts significantly more often than other professions (Table 3). However, only 37% (n = 89) of the self-proclaimed experts answered the question for the precise definition of early mobilization correctly. The median implementation of protocols was 68 [IQR 48–80].

Table 2. Participants’ data.

| Items | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Profession | |

| Nurses | 370 (72) |

| Physical therapists | 83 (16) |

| Physicians | 48 (9) |

| Other specialistsa | 14 (3) |

| Socio-demographic data | |

| Germany | 395 (77) |

| Austria | 38 (7) |

| Switzerland | 78 (15) |

| Otherb | 4 (1) |

| Age (years) | |

| < 35 | 196 (38) |

| 35–48 | 202 (39) |

| 49–67 | 117 (23) |

| Job experience (years) | |

| In education/study | 1 (0) |

| < 1 | 17 (3) |

| 1–4 | 99 (19) |

| 5–10 | 135 (26) |

| > 10 | 131 (25) |

| > 20 | 132 (26) |

| Professionalism | |

| Self-perceived expert status | 242 (47) |

| Answered definition of early mobilization correctly | 176 (35) |

| Experts, who answered definition of early mobilization correctly | 89 (37) |

| Protocols, implemented on own ICU | |

| Analgesia | 432 (63) |

| Sedation | 344 (67) |

| Delirium | 267 (52) |

| Weaning | 345 (67) |

| Early mobilization | 162 (32) |

| Daily inter-professional goals | 193 (38) |

| Automatic order for mobilization | 110 (21) |

| Estimated percentage of existing protocols’ implementation. from 0 = no implementation to 100 = full implementation (median [IQR)] | 68 [48–80] |

a Respiratory therapists, speech and swallow therapists, occupational therapists

b Luxembourg (n = 2), and missing (n = 2)

Table 3. Self-perceived expert status per profession.

| Profession | Nurses (n = 367) | Physical therapistsa (n = 83) | Physicians (n = 47) | Other specialistsb (n = 14) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-perceived expert status | 155 (42) | 63 (76) | 17 (36) | 7 (50) | <0.001 |

| Answered definition of early mobilization correctly | 131 (36) | 26 (31) | 15 (32) | 6 (43) | 0.75 |

| Experts, who answered definition of early mobilization correctly | 61 (39) | 17 (27) | 7 (41) | 4 (57) | 0.57 |

a Physical Therapists perceived themselves as experts significantly more often, compared to nurses and physicians (both p<0.001), but not other specialists (p = 0.057).

b Respiratory therapists, speech and swallow therapists, occupational therapists.

Scenario 1 –awake & stable

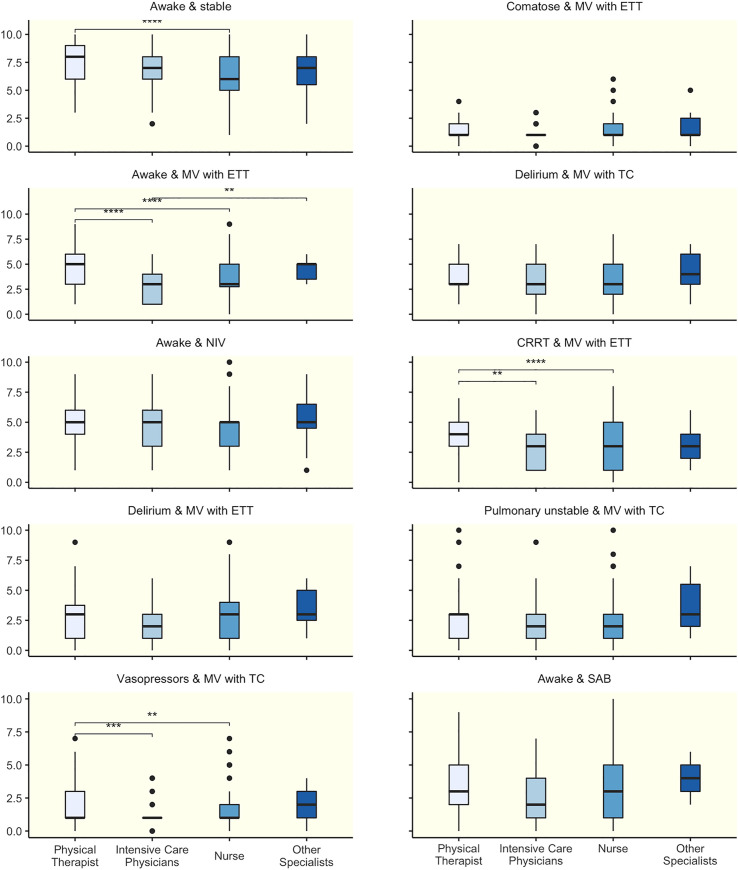

The selected mobilization level was 6 [5–8], representing marching in place, with significant differences between nurses and physical therapists (p<0.001. Fig 1). Interestingly, 9% would let the patient walk independently, without assistance or gait aid. The median number of health care professionals necessary for mobilization at this level was 2 [1–3].

Fig 1. Mobility capacity of ten clinical scenarios scored by different professions.

Mobility capacity scored by different professions using the ICU Mobility scale. * p ≤ 0.05. ** p ≤ 0.01. *** p ≤ 0.001. **** p ≤ 0.0001.

Scenario 2 –comatose & mechanical ventilation via endotracheal tube

In this scenario, the median estimated mobilization level was 1 [1, 2], representing active mobilization in bed, without any significant differences among professions in the posthoc tests (Fig 1). Overall, 14% would mobilize the unresponsive and ventilated patient to the edge of the bed. The median number of health care professionals required for mobilization in this level was 2 [1–3], with a lower value of one person in the physician and physical therapist subgroups (p = 0.007, see S1 Appendix).

Scenario 3 –awake & mechanical ventilation via endotracheal tube

In the third scenario, with an awake intubated patient, the median proposed mobilization level was 3 [3–5], which is sitting on the edge of the bed. There are significant differences between physical therapists compared to physicians or nurses (p<0.001 for both), as well as physicians and other specialists (p = 0.007), with physical therapists and other specialists aiming for higher mobility levels (Fig 1).

Overall, 5% would even attempt to walk with the patient (level 7 or higher), although none of the physicians or other specialists, and only 3% of nurses would try it compared to 14% of physical therapists. On the other hand, physical therapists are the subgroup with the highest percentage (40%) of passive approaches (maximum mobilization level of 2, passively in a chair) compared to 33% in physicians, 25% in nurses and none in other specialists. The median number of required health care professionals was 2 [2–4] (see S1 Appendix).

Scenario 4 –delirium & mechanical ventilation with a tracheostomy cannula

Median mobilization level in this scenario was 3 [3–5], which is sitting on the edge of a bed, yielding no significant differences among professions (Fig 1). Only a small group of people would try to walk with such a patient (4%). A median number of health care professionals required for mobilization was 2 [2–4], here with significant differences among professions (p = 0.012, see S1 Appendix).

Scenario 5 –awake & non-invasive ventilation

The estimated level of mobilization was 5 [3–6], which represents an active transfer from a bed to a chair, without significant differences in the posthoc comparisons among professions (Fig 1). 12% would try to walk with the patient, with a higher percentage in the subgroup physical therapists (19%) and other specialists (27%), compared to physicians (13%) and nurses (10%). The median number of health care workers required for mobilization was 2 [2–4].

Scenario 6 –continuous renal replacement therapy & mechanical ventilation via endotracheal tube

In a patient with continuous renal replacement therapy, the estimated level of mobilization was 3 [1–5], corresponding to sitting on the edge of a bed (Fig 1). Physical therapists scored significantly higher compared to nurses (p<0.001) and physicians (p = 0.0119). Overall, a median of 2.5 [2–4] staff members were estimated to be required for mobilization (see S1 Appendix).

Scenario 7 –delirium & mechanical ventilation via endotracheal tube

The estimated level of mobilization was 3 [1–4], corresponding to sitting on the edge of bed. There were no significant differences overall (Fig 1). Respondents estimated that 2 [1.25–4] team members would be required to mobilize this patient, with the subgroup nurses and other therapists opting for more staff members (p = 0.012, see S1 Appendix).

Scenario 8 –pulmonary unstable & MV mechanical ventilation via tracheostomy cannula

The median estimated mobilization level was 3 [1–3], which means sitting on the edge of a bed without differences among professions (Fig 1). The median number of health care professionals needed to mobilize that patient was estimated to be 2 [2–4].

Scenario 9 –vasopressors & MV mechanical ventilation via tracheostomy cannula

In this scenario, the estimated mobilization level was 1 [1–3], which represents active mobilization in the bed (Fig 1). Physical therapists scored significantly higher than nurses (p = 0.0164) and physicians (p<0.001). However, 22% would attempt to mobilize the patient on level 3 (edge of a bed), especially other specialists (40%) and physical therapists (33%). The median number of health care professionals required for mobilization was 2 [1–3], with physicians only needing one in accordance with their proposed lower mobilization level, while other specialists required a median of four staff members (p = 0.020, see S1 Appendix).

Scenario 10 –awake & subarachnoid hemorrhage

This scenario of neurocritical care resulted in an estimated mobilization level of 3 [1–5], which means sitting on the edge of a bed. 21% of physicians opted for no mobilization at all, and even fewer from other subgroups (12% nurses, 8% physical therapists and 0% other specialists, Fig 1). Again, respondents estimated 2 [1–3] team members as required to mobilize this patient, except physicians who voted for one person (p = 0.028, see S1 Appendix).

Overall model and influencing factors

Profession (p = 0.001), expert status (p = 0.049), and the knowledge of the definition of early mobilization according to the German guideline (p = 0.002) had a significant effect in the linear mixed-effects model over all scenarios adjusted for scenario factors (consciousness, breathing, strength, respiratory stability, hemodynamic stability, lines as described in Table 1), ICU factors (existence of protocols) as well as other respondent characteristics (age, work experience, geographical area, Table 4 and S1 Appendix). Physicians (p = 0.001) and nurses (p = 0.002) estimated a lower mobilization level compared to physiotherapists, while other specialists did not (p = 0.81).

Table 4. Linear mixed model over all scenarios.

| Factora | Value | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Profession compared to Physical therapists | |||

| Physician | -0.7 | (-1.1 to -0.3) | 0.001 |

| Nurses | -0.4 | (-0.7 to -0.2) | 0.002 |

| Other specialists | 0.1 | (-0.5 to 0.6) | 0.808 |

| Knowledge of S2e guideline definition | 0.3 | (0.1 to 0.5) | 0.002 |

| Expert | 0.2 | (0.0 to 0.4) | 0.049 |

aLinear mixed model with all scenario describing factors (consciousness, breathing, strength, respiratory stability, hemodynamic stability, lines as described in Table 1) being significant (p < 0.001). Other factors, such as age, work experience or geographical area of the participants, as well as existing of protocols at the ICU were not significant in the model.

Barriers

The top three barriers in this survey were hemodynamic and/or pulmonary instability (n = 350; 67%), lack of nurses (n = 271; 53%), and deep sedation (n = 228; 44%) (Table 5). There were no significant differences regarding barriers among professions (see S1 Appendix).

Table 5. Top three barriers to mobilization, according to the profession.

| Rank of barriers within a professiona | Physicians (n = 48) | Nurses (n = 370) | Physical therapists (n = 83) | Others specialistsb (n = 14) | Total (n = 515) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOP 1 | Hemodynamic / pulmonary instability 30 (63%) | Hemodynamic / pulmonary instability 252 (68%) | Hemodynamic / pulmonary instability 62 (75%) | Deep sedation 8 (57%) | Hemodynamic / pulmonary instability 350 (68%) |

| TOP 2 | Deep sedation 20 (42%) | Lack of nurses 226 (61%) | Deep sedation 53 (64%) | Hemodynamic / pulmonary instability 6 (43%) | Lack of nurses 271 (53%) |

| TOP 3 | Lack of nurses 19 (40%) | Deep sedation 147 (40%) | Lack of nurses 20 (24%) | Lack of nurses 6 (43%) | Deep sedation 228 (44%) |

a Participants were asked to select the three most important barriers

b Includes respiratory therapists, speech and swallow therapists, occupational therapists

Discussion

We analyzed the assessments of more than 500 critical care team members, who estimated the mobilization capacity of ten different patient scenarios in the ICU. While differences among the professions where found in four scenarios (awake & stable; awake & mechanical ventilation via endotracheal tube; continuous renal replacement therapy & mechanical ventilation via endotracheal tube; vasopressors & mechanical ventilation via tracheostomy cannula), agreement about the possible level of mobilization was observed in six scenarios. Furthermore, ICU staff who knew how early mobilization is defined in the current German guideline suggested a higher target level for the mobilization treatment. In general, physical therapists and other specialists aimed for higher levels of mobilization compared to physicians and nurses, independent of age, job experience, presence of protocols or geographical area. Most cited barriers were patient instability, lack of nurses and deep sedation.

Mobility levels

No significant differences in estimated mobilization levels among health care professionals were present in scenarios with coma, with delirium, with non-invasive ventilation, with pulmonary instability or with a subarachnoid hemorrhage. For impaired consciousness [31] and delirium [5, 12] evidence of benefits of early mobilization is available in the literature. Early mobilization is typically recommended during non-invasive ventilation [32, 33] and mechanical ventilation [5, 12] while for subarachnoid hemorrhage the evidence in critically ill patients is scarce [13]. However, no simple model or pattern can be derived which scenarios had an interprofessional agreement, so that further investigation is necessary. In accordance with our overall results and the majority of scenarios, however, previous studies also reported differences in the mobilization level of patients according to different professions [16, 34]. These differences can partly be explained by differing education and training [34]. Safety concerns limiting mobilization are common among nurses, as they tend to feel responsible for the integrity of the devices, in particular for the endotracheal tube and the catheters for the renal replacement therapy [35]. Interestingly, Fontela et al. [21] and Jolley et al. [18] found no knowledge differences between physical therapists and nurses according to mobilization. Local standards of education may influence interprofessional differences in knowledge and possibly performance. In addition, there might be distinct ICUs with high levels of mobility across all professions [36]. Another explanation for different mobilization targets might lie on different roles and attitudes [37], leading to varying emphases on specific aspects of mobility. For instance, if a physical therapist focuses on strength and functionality, marching in place might be prioritized [38]. If a nurse focuses on a patient’s well-being, sitting in a chair together with family may be seen as sufficient [39]. Physicians may be more prone to have weaning as a target [26]. Beside these psychosocial and cultural aspects, other facets, such as working habits, inter-professional communication, staff-to-patient ratios, and equipment might contribute to the diverse decision-making [23, 29, 40].

Staff resources

Estimation of the number of staff necessary for mobilization in each scenario differed in a few cases among professions. The number may depend on the targeted mobility level, and more devices may require more staff [41]. In fact, there is no evidence for a commonly agreed number of staff members, so that it varies according to patient’s condition, targeted mobility level, a mix of professions, and other factors, such as first vs. following mobilization, safety, quality, intensity, duration, and equipment. Guidelines recommend at least two, or even three team members for the mobilization of critically ill patients, but note that the actual number depends on the specific situation [1]. In some of our scenarios, the perception of how much staff is required differed among professions, and this different perception should be acknowledged to improve communication within the team. It must be highlighted that only 32% of the participants used a protocol for early mobilization. This is less than reported in previous studies in Germany [27], but slightly more than in other surveys from the United States, France, or United Kingdom [42]. The presence of mobilization protocols has an increasing impact on the mobilization level of patients [43, 44], but their influence on the individual decisions of health care professionals remains unknown.

Barriers

In agreement with other reports, we identified patient instability, deep sedation and lack of nurses as the top three barriers against advanced mobilization targets [15, 29]. In contrast to some reports [16, 18, 21, 34], however, there was a similar perception regarding mobilization barriers in our scenarios among the surveyed professions. Garzon-Serrano [16] reported that physical therapists indicate hemodynamic instability as an obstacle to mobilization, but not renal replacement procedures. Berney et al. [34] and Fontela et al. [21] reported similar results, with physicians and nurses rating ventilation status as decisive when setting mobilization targets, while physical therapists perceived sedation state as critical for the decision. Berney explains these differences with varying responsibilities in the ICU team. Lack of nurses is an often-cited barrier, but nurses may oversee possibilities for mobilization [39]. Staff shortage and limited time resources, coupled with the broader responsibilities of caregivers, may favor the higher degree of patient mobilization by physical therapists. Physical therapists are valuable and efficient in terms of mobilization, especially by focusing on the muscular and neurological status of the patient [16]. Nickels et al. [24] reported no differences among professions when conducting a survey in a single ICU with a homogenous culture.

Strategies to overcome these barriers can encompass an inter-professional approach, which has been shown to improve early mobilization [7, 11, 14, 40]. Another important aspect is the use of protocols [45, 46], which can contribute to breaking down the structural barriers. Regular inter-professional meetings as well as inter-professional exchange increase the probability of mobilization [12, 15].

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this survey is the high number of participating critical care team members from different professions, lowering the risk of a selection bias. The results are limited to voluntary participating respondents with limited generalizability, leading to a possible higher estimation of mobility levels. Another limitation is that the ten scenarios have not been validated. Furthermore, decisions in clinical practice can deviate significantly from fictitious cases. Although only 9% of respondents were physicians, and a higher participation rate might have influenced the results, physicians represent the smallest group within the multi-professional critical care team and early mobilization networks [47]. In addition, not all possible clinical scenarios (e.g. the combination of hemodynamic instability and continuous renal replacement therapy) could be assessed.

Conclusion

In summary, professions assess the capacity for mobilizing critical care patients differently. A reduced estimation of a patient’s mobility capacity may have an impact on rehabilitation and may limit mobilization. The exact knowledge of guidelines independently leads to a higher target level of mobilization. The key to successful therapy of the intensive care patient is teamwork. To optimally utilize and execute mobilization, an interprofessional understanding of rehabilitation practices and goals is essential. Hence, all professions of the ICU may benefit from interprofessional education, interprofessional rounds and participation in rehabilitation activities.

Supporting information

PDF with the original (German) survey, detail description of the scenarios, additional tables (required staff of mobilization, the ANOVA calculation of the mixed model and barriers to mobilization).

(PDF)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for all interprofessional critical care team members who participated in our survey. We would like to thank Dr. Rudolf Mörgeli, Department of Anesthesiology and Operative Intensive Care Medicine, Charité –Universitätsmedizin Berlin for his language correction of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The complete dataset is available here: DOI 10.6084/m9.figshare.12967106.

Funding Statement

We acknowledge support from the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the Open Access Publication Fund of Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin.

References

- 1.Bein T, Bischoff M, Bruckner U, Gebhardt K, Henzler D, Hermes C, et al. S2e guideline: positioning and early mobilisation in prophylaxis or therapy of pulmonary disorders: Revision 2015: S2e guideline of the German Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine (DGAI). Der Anaesthesist. 2015;64 Suppl 1:1–26. 10.1007/s00101-015-0071-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Devlin JW, Skrobik Y, Gelinas C, Needham DM, Slooter AJC, Pandharipande PP, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU. Critical care medicine. 2018;46(9):e825–e73. Epub 2018/08/17. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003299 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waldauf P, Jiroutkova K, Krajcova A, Puthucheary Z, Duska F. Effects of Rehabilitation Interventions on Clinical Outcomes in Critically Ill Patients: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Crit Care Med. 2020. Epub 2020/04/30. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004382 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morris PE, Goad A, Thompson C, Taylor K, Harry B, Passmore L, et al. Early intensive care unit mobility therapy in the treatment of acute respiratory failure. Critical care medicine. 2008;36(8):2238–43. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318180b90e . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schweickert WD, Pohlman MC, Pohlman AS, Nigos C, Pawlik AJ, Esbrook CL, et al. Early physical and occupational therapy in mechanically ventilated, critically ill patients: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9678):1874–82. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60658-9 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Needham DM, Korupolu R, Zanni JM, Pradhan P, Colantuoni E, Palmer JB, et al. Early Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation for Patients With Acute Respiratory Failure: A Quality Improvement Project. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2010;91(4):536–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schaller SJ, Anstey M, Blobner M, Edrich T, Grabitz SD, Gradwohl-Matis I, et al. Early, goal-directed mobilisation in the surgical intensive care unit: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10052):1377–88. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31637-3 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schaller SJ, Scheffenbichler FT, Bose S, Mazwi N, Deng H, Krebs F, et al. Influence of the initial level of consciousness on early, goal-directed mobilization: a post hoc analysis. Intensive care medicine. 2019;45(2):201–10. Epub 2019/01/23. 10.1007/s00134-019-05528-x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nydahl P, Sricharoenchai T, Chandra S, Kundt FS, Huang M, Fischill M, et al. Safety of Patient Mobilization and Rehabilitation in the Intensive Care Unit. Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(5):766–77. Epub 2017/02/24. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201611-843SR . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lord RK, Mayhew CR, Korupolu R, Mantheiy EC, Friedman MA, Palmer JB, et al. ICU early physical rehabilitation programs: financial modeling of cost savings. Critical care medicine. 2013;41(3):717–24. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182711de2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balas MC, Vasilevskis EE, Olsen KM, Schmid KK, Shostrom V, Cohen MZ, et al. Effectiveness and safety of the awakening and breathing coordination, delirium monitoring/management, and early exercise/mobility bundle. Critical care medicine. 2014;42(5):1024–36. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schaller SJ, Anstey M, Blobner M, Edrich T, Grabitz SD, Gradwohl-Matis I, et al. Early, goal-directed mobilisation in the surgical intensive care unit: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10052):1377–88. Epub 2016/10/07. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31637-3 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuest K, Schaller SJ. Recent evidence on early mobilization in critical-Ill patients. Current opinion in anaesthesiology. 2018;31(2):144–50. Epub 2018/01/20. 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000568 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nessizius SJMK-IuN. Maßgeschneiderte Frühmobilisation. 2017;112(4):308–13. 10.1007/s00063-017-0280-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dubb R, Nydahl P, Hermes C, Schwabbauer N, Toonstra A, Parker AM, et al. Barriers and Strategies for Early Mobilization of Patients in Intensive Care Units. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(5):724–30. Epub 2016/05/06. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201509-586CME . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garzon-Serrano J, Ryan C, Waak K, Hirschberg R, Tully S, Bittner EA, et al. Early Mobilization in Critically Ill Patients: Patients' Mobilization Level Depends on Health Care Provider's Profession. PM&R. 2011;3(4):307–13. 10.1016/j.pmrj.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costa DK, White MR, Ginier E, Manojlovich M, Govindan S, Iwashyna TJ, et al. Identifying Barriers to Delivering the Awakening and Breathing Coordination, Delirium, and Early Exercise/Mobility Bundle to Minimize Adverse Outcomes for Mechanically Ventilated Patients: A Systematic Review. Chest. 2017;152(2):304–11. Epub 2017/04/26. 10.1016/j.chest.2017.03.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jolley SE, Regan-Baggs J, Dickson RP, Hough CL. Medical intensive care unit clinician attitudes and perceived barriers towards early mobilization of critically ill patients: a cross-sectional survey study. BMC anesthesiology. 2014;14:84 Epub 2014/10/14. 10.1186/1471-2253-14-84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taito S, Shime N, Ota K, Yasuda H. Early mobilization of mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. Journal of intensive care. 2016;4:50 Epub 2016/08/02. 10.1186/s40560-016-0179-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nydahl P, Dewes M, Dubb R, Filipovic S, Hermes C, Juttner F, et al. Early Mobilization: competencies, responsibilities and accountabilities (German: Frühmobilisierung: Kompetenzen, Verantwortungen, Zuständigkeiten). Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed. 2016;111(2):153–9. 10.1007/s00063-015-0073-4 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fontela PC, Forgiarini LA Jr., Friedman G. Clinical attitudes and perceived barriers to early mobilization of critically ill patients in adult intensive care units. Revista Brasileira de terapia intensiva. 2018;30(2):187–94. Epub 2018/07/12. 10.5935/0103-507x.20180037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holdsworth C, Haines KJ, Francis JJ, Marshall A, O'Connor D, Skinner EH. Mobilization of ventilated patients in the intensive care unit: An elicitation study using the theory of planned behavior. J Crit Care. 2015;30(6):1243–50. Epub 2015/09/15. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.08.010 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toonstra AL, Nelliot A, Aronson Friedman L, Zanni JM, Hodgson C, Needham DM. An evaluation of learning clinical decision-making for early rehabilitation in the ICU via interactive education with audience response system. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(11):1143–5. Epub 2016/06/14. 10.1080/09638288.2016.1186751 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nickels M, Aitken LM, Walsham J, Watson L, McPhail S. Clinicians' perceptions of rationales for rehabilitative exercise in a critical care setting: A cross-sectional study. Australian critical care: official journal of the Confederation of Australian Critical Care Nurses. 2017;30(2):79–84. Epub 2016/04/24. 10.1016/j.aucc.2016.03.003 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of Web surveys: the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(3):e34 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bailey P, Thomsen GE, Spuhler VJ, Blair R, Jewkes J, Bezdjian L, et al. Early activity is feasible and safe in respiratory failure patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(1):139–45. 10.1097/01.CCM.0000251130.69568.87 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nydahl P, Ruhl AP, Bartoszek G, Dubb R, Filipovic S, Flohr HJ, et al. Early mobilization of mechanically ventilated patients: a 1-day point-prevalence study in Germany. Critical care medicine. 2014;42(5):1178–86. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000149 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hickmann CE, Castanares-Zapatero D, Bialais E, Dugernier J, Tordeur A, Colmant L, et al. Teamwork enables high level of early mobilization in critically ill patients. Ann Intensive Care. 2016;6(1):80 10.1186/s13613-016-0184-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parry SM, Knight LD, Connolly B, Baldwin C, Puthucheary Z, Morris P, et al. Factors influencing physical activity and rehabilitation in survivors of critical illness: a systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Intensive care medicine. 2017;43(4):531–42. 10.1007/s00134-017-4685-4 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hodgson C, Needham D, Haines K, Bailey M, Ward A, Harrold M, et al. Feasibility and inter-rater reliability of the ICU Mobility Scale. Heart Lung. 2014;43(1):19–24. Epub 2014/01/01. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2013.11.003 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schaller SJ, Scheffenbichler FT, Bose S, Mazwi N, Deng H, Krebs F, et al. Influence of the initial level of consciousness on early, goal-directed mobilization: a post hoc analysis. Intensive care medicine. 2019. Epub 2019/01/23. 10.1007/s00134-019-05528-x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sibilla A, Nydahl P, Greco N, Mungo G, Ott N, Unger I, et al. Mobilization of Mechanically Ventilated Patients in Switzerland. J Intensive Care Med. 2017:885066617728486. Epub 2017/08/30. 10.1177/0885066617728486 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jolley SE, Moss M, Needham DM, Caldwell E, Morris PE, Miller RR, et al. Point Prevalence Study of Mobilization Practices for Acute Respiratory Failure Patients in the United States. Critical care medicine. 2017;45(2):205–15. Epub 2016/09/24. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Berney SC, Rose JW, Denehy L, Granger CL, Ntoumenopoulos G, Crothers E, et al. Commencing out of bed rehabilitation in critical care—what influences clinical decision-making? Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2018. Epub 2018/09/03. 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.07.438 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parry SM, Remedios L, Denehy L, Knight LD, Beach L, Rollinson TC, et al. What factors affect implementation of early rehabilitation into intensive care unit practice? A qualitative study with clinicians. J Crit Care. 2017;38:137–43. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.11.005 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brock C, Marzano V, Green M, Wang J, Neeman T, Mitchell I, et al. Defining new barriers to mobilisation in a highly active intensive care unit—have we found the ceiling? An observational study. Heart Lung. 2018;47(4):380–5. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2018.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krupp A, Steege L, King B. A systematic review evaluating the role of nurses and processes for delivering early mobility interventions in the intensive care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2018;47:30–8. Epub 2018/04/24. 10.1016/j.iccn.2018.04.003 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gosselink R, Bott J, Johnson M, Dean E, Nava S, Norrenberg M, et al. Physiotherapy for adult patients with critical illness: recommendations of the European Respiratory Society and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Task Force on Physiotherapy for Critically Ill Patients. Intensive care medicine. 2008;34(7):1188–99. 10.1007/s00134-008-1026-7 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Young DL, Seltzer J, Glover M, Outten C, Lavezza A, Mantheiy E, et al. Identifying Barriers to Nurse-Facilitated Patient Mobility in the Intensive Care Unit. American Journal of Critical Care. 2018;27(3):186–93. 10.4037/ajcc2018368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schaller SJ, Stauble CG, Suemasa M, Heim M, Duarte IM, Mensch O, et al. The German Validation Study of the Surgical Intensive Care Unit Optimal Mobility Score. J Crit Care. 2016;32:201–6. Epub 2016/02/10. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.12.020 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee H, Ko YJ, Jung J, Choi AJ, Suh GY, Chung CR. Monitoring of Potential Safety Events and Vital Signs during Active Mobilization of Patients Undergoing Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy in a Medical Intensive Care Unit. Blood Purif. 2016;42(1):83–90. Epub 2016/05/18. 10.1159/000446175 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bakhru RN, McWilliams DJ, Wiebe DJ, Spuhler VJ, Schweickert WD. Intensive Care Unit Structure Variation and Implications for Early Mobilization Practices. An International Survey. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(9):1527–37. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201601-078OC . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Queiroz RS, Saquetto MB, Martinez BP, Andrade EA, da Silva P, Gomes-Neto M. Evaluation of the description of active mobilisation protocols for mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Heart Lung. 2018;47(3):253–60. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2018.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parry SM, Nydahl P, Needham DM. Implementing early physical rehabilitation and mobilisation in the ICU: institutional, clinician, and patient considerations. Intensive Care Med. 2017. 10.1007/s00134-017-4908-8 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hodgson CL, Stiller K, Needham DM, Tipping CJ, Harrold M, Baldwin CE, et al. Expert consensus and recommendations on safety criteria for active mobilization of mechanically ventilated critically ill adults. Crit Care. 2014;18(6):658 10.1186/s13054-014-0658-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nydahl P, Dubb R, Filipovic S, Hermes C, Jüttner F, Kaltwasser A, et al. Algorithmen zur Frühmobilisierung auf Intensivstationen. 2017;112(2):156–62. 10.1007/s00063-016-0210-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nydahl P, Spindelmann E, Hermes C, Kaltwasser A, Schaller SJ. German Network for Early Mobilization: Impact for participants. Heart Lung. 2020. Epub 2020/01/11. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2019.12.004 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDF with the original (German) survey, detail description of the scenarios, additional tables (required staff of mobilization, the ANOVA calculation of the mixed model and barriers to mobilization).

(PDF)

Data Availability Statement

The complete dataset is available here: DOI 10.6084/m9.figshare.12967106.