Abstract

Survival often depends on behavior that can adapt to rapid changes in contingencies, which should be particularly well suited to a contingency-sensitive and data-based discipline such as applied behavior analysis (ABA). The speed and scale with which contingencies shifted in early March 2020 due to the effects of COVID-19 represent a textbook case for rapid adaptation with a direct impact on the survival of many types of enterprises. We describe here the impact, changes, and outcomes achieved by a large, multifaceted ABA clinical program that has (a) ongoing data that forecasted and tracked changes, (b) staff well practiced with data-based shifts in operations (behavior), and (c) up-to-date information (data) on policy and regulations. The results showed rapid shifts in client and staff behavior on a daily basis, shifts in services from in-person services to telehealth, and increases in volumes, revenue, and margins. We detail regulations and provide actionable steps that clinical organizations can take pertinent to this shift now and in the future. The challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic underscore the importance of maintaining robust coordination and communication across our field in order to address crises that affect our field.

Keywords: Applied behavior analysis, Child problem behavior, Coronavirus, Service delivery, Telehealth

The novel coronavirus and illness caused by the virus (i.e., COVID-19) were first discovered in late 2019. By late January 2020, the United States had confirmed cases of COVID-19. Community spread was reported on the West Coast of the United States in late February. Subsequently in March, a nationwide effort was initiated to slow the spread of COVID-19, primarily through social-distancing measures. Over the past few months, states across the United States have declared a state of emergency and/or issued stay-at-home orders. Schools closed their doors and initiated distance learning, and nonessential businesses were mandated to close in nearly all states. When in public, people are advised to keep a distance of at least 6 feet from one another and wear a mask. Although states are gradually beginning to reopen as of this writing, social-distancing procedures are likely to be necessary into 2022 (Kissler, Tedijanto, Goldstein, Grad, & Lipstich, 2020).

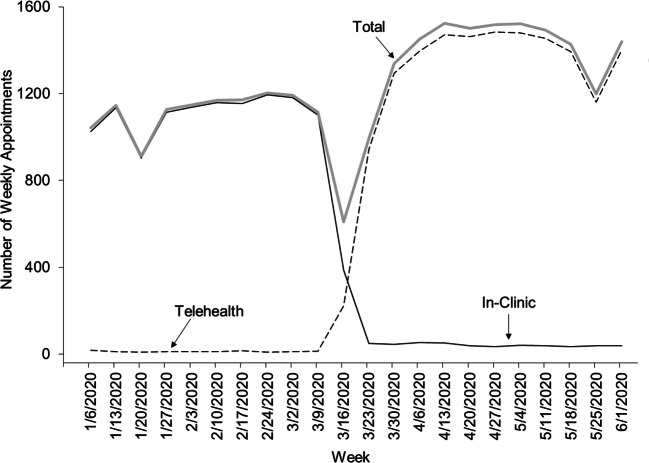

The rapid, but necessary, shift to social distancing has had a profound impact on behavioral health services for children. Up to one in five American children experience a significant behavior problem (Merikangas et al., 2010; Sheldrick, Merchant, & Perrin, 2011; Totsika, Hastings, Emerson, Berridge, & Lancaster, 2011). Treatments based on applied behavior analysis (ABA) are highly effective in reducing child problem behavior and increasing prosocial behavior (Doehring, Reichow, Palka, Phillips, & Hagopian, 2014; Heyvaert, Saenen, Campbell, Maes, & Onghena, 2014). Most ABA research focuses on children with intellectual or developmental disabilities, but studies also demonstrate that ABA interventions are effective for typically developing children (e.g., Austin, Groves, Reynish, & Francis, 2015; Call, Wacker, Ringdahl, Cooper-Brown, & Boelter, 2004; Greer et al., 2013). Among other things, ABA interventions usually involve frequent one-on-one interaction between the provider and the client. With social-distancing mandates and recommendations, there are two related dilemmas for behavioral health providers. First, although behavioral health falls under “essential business” and technically could continue with face-to-face care, providers had to weigh the ethical risks of doing so. Continuing in-person appointments puts the child, parent, and provider, as well as all parties’ families, at risk. Second, and partially solving the first dilemma, even if a provider continued business as usual, clients could (and did) cancel appointments. As an example, the solid black line of Fig. 1 displays the weekly number of in-clinic appointments for clients served by the Department of Behavioral Psychology at the Kennedy Krieger Institute (hereafter referred to as the department; the data in Fig. 1 will be discussed in more detail later in this article). There was a rapid decline in appointment attendance for both new and returning clients in mid-March due to client cancellations, which were presumed to be due to families’ resistance to physically attending an in-clinic session. Therefore, it was clear to us, as well as providers across the country, that an alternative to in-person care was necessary. To that end, many health care providers began to offer telehealth.

Fig. 1.

Total weekly behavioral psychology outpatient appointments

When providing telehealth services, many considerations, rules, and regulations should be addressed. Within our department, we have been providing telehealth services to military families since 2016 (referred to as the military project). The infrastructure in place for the military project allowed our entire department (as well as other departments within the institute) to rapidly transition to telehealth. In this article, we (a) describe the various legal, ethical, and logistical considerations for designing a telehealth service delivery model; (b) describe the steps needed to scale up the model across an organization; and (c) provide data demonstrating our transition from primarily in-person to primarily telehealth appointments over a 2-week period. First, however, we start with a brief overview of our department.

Department of Behavioral Psychology, Kennedy Krieger Institute

The Department of Behavioral Psychology provides assessment and treatment for a wide range of child behavior problems based on the principles of ABA. We have three interdisciplinary inpatient programs: the Neurobehavioral Unit (NBU), the Pediatric Feeding Disorders Program (Feeding), and the Pediatric Pain Rehabilitation Program (Pain). The NBU is devoted to severe and treatment-resistant problem behavior such as self-injury and aggression. The Feeding program focuses on treating severe and medically complicated feeding problems such as food refusal, vomiting, and gastronomy-tube dependence. The Pain program treats children with chronic pain to promote home, school, and community functioning. NBU, Feeding, and Pain provide a continuum of care that includes inpatient, intensive outpatient, outpatient, and follow-up services. In addition, there are four other outpatient clinics that provide behavioral services to various populations with less severe behavior problems. These outpatient programs typically see clients about once every 1–2 weeks. Briefly, the Pediatric Developmental Disorder Clinic (PDD) treats children with developmental delays and disabilities, the Behavior Management Clinic (BMC) works with typically developing children from 2 to 12 years old, Child and Family Therapy (CFT) sees typically developing individuals from 5 to 20 years old, and the Pediatric Psychology Consultation Service (PPCS) includes the outpatient arm of the Pain program and works with children with other chronic illnesses.

Across all programs, clinicians see between 9,000 and 10,000 families annually. The services provided across the department are based in ABA. There are 66 doctoral-level clinicians. Several programs (e.g., NBU and Feeding) provide training for Board Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA) applicants, which is coordinated with local university verified course sequences. In addition, all programs participate in (a) a doctoral internship training program that is accredited by the American Psychological Association (APA) and (b) a postdoctoral fellowship training program that is a member of the Association of Psychology Postdoctoral and Internship Centers. These two training programs include approximately 70 trainees annually. With a few exceptions, all staff clinicians (i.e., nontrainees) are licensed clinical psychologists, and treatment services are billed as psychological services. This is particularly relevant for the current discussion of telehealth because many rules and regulations related to telehealth revolve around billing and insurance reimbursement considerations. Currently, reimbursement for ABA services by a BCBA (nonpsychologist) is largely limited to children with autism spectrum disorder. However, the considerations that apply for psychologists are also highly relevant to BCBAs transitioning to telehealth services, and similar restrictions apply.

In 2013, the department established the Behavioral Health Program for Military Families, and in 2016 it extended this program to the delivery of behavioral services via telehealth. The Defense Health Agency (Department of Defense) was interested in military families being able to receive their care directly in their homes via telehealth. Our department participated in a pilot project with the U.S. Family Health Plan (a TRICARE insurance plan), which allowed the initiation of telehealth within our department. This telehealth service delivery model has continued across BMC, CFT, and PDD for close to 4 years. Because of the military project, we have slowly built the infrastructure and systems for a telehealth program. We believe our rapid conversion to telehealth is directly related to (a) our experience addressing telehealth rules and regulations, (b) the continuous collection and use of data about operations, and (c) a history of success based on staff response to such data.

Considerations for Designing a Telehealth Program

Our experience is distilled into rules and regulations (Table 1) and specific actions (Table 2). Specifically, the rules and regulations for transitioning behavioral services to telehealth largely come from four main sources: professional ethics codes (e.g., APA, 2017; Behavior Analyst Certification Board [BACB], 2019), the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA),1 insurance regulations, and state licensure laws. In Table 1, we list various topics and issues to consider based on these sources. There is considerable variability for both insurance regulations and state licensure laws. We, therefore, do not provide specific details for each insurance company or state but do list general trends based on our experiences and review of regulations. We list the pre-COVID-19 considerations, as well as changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2020, hereafter the Coronavirus Preparedness Act; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020a). Changes in regulations have allowed many providers to transition to telehealth. We realize that many providers have already made the transition to telehealth; however, we anticipate that the changes are temporary (particularly those related to HIPAA and insurance reimbursement) and may soon be revoked when emergency declarations are ended. Therefore, providers should prepare for that eventuality. Across all topics, we note considerations for reimbursement by insurance companies and documentation. In Table 2, we detail specific actions we took that providers and their clinical organizations may consider to address the guidelines in Table 1.

Table 1.

Guidelines for telehealth service bbefore and after the COVID-19 pandemic

| Topic | Relevant guidelines | General considerations | Reimbursement considerations | Documentation considerations | Changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consent | Ethics Code; HIPAA | There may be added risks associated with confidentiality and privacy that need to be included in consent procedures | No specific considerations | Signed consent to treat via telehealth | No change, but may not ever be physically face-to-face with client so consent may need to be virtual |

| Privacy | Ethics Code; HIPAA | Transmission and storage of PHI must be encrypted and secure | No specific considerations | Notice of privacy rights signed and acknowledged by client annually | Temporarily no HIPAA violations will be prosecuted; unclear how long it will be suspended |

| Platform and equipment (Providers) | Ethics Code; HIPAA; insurance regulations | Platform must be HIPAA-compliant and accessible for clients | Requires interactive audiovisual sessions; phone, e-mail, or asynchronous video may not be eligible for reimbursement | Type of telehealth service provided | Alternative formats such as phone calls and text messages are currently permissible and reimbursable but must be documented |

| Client access | Ethics Code | Consider how platform and equipment needs influence clients’ access to services; may consider providing access to necessary equipment | No specific considerations | No specific considerations | Access may be easier because standard telephone services are temporarily permissible |

| Originating and distant sites | Insurance regulations | Location of the client can impact eligibility for services | Facility-to-facility required; may require that client reside in a “rural” area | Originating site location and distance from provider | Restrictions on originating site have been lifted by insurance companies (home-to-facility are permitted) |

| Licensure and state restrictions | State licensure laws; Ethics Code | Professionals must be licensed to practice in the originating site state (i.e., where the client is located during telehealth services) | State licensure could affect reimbursement | License for each state (including temporary); continuing education and other requirements for license renewal | Some states waive licensure requirements, others provide temporary licensure, and others require providers to apply for licensure; in some states, telehealth is only permitted with established patients |

| Credentials or privileges | Insurance regulations | May need telehealth credentials or privileges to practice | Credentialing necessary for reimbursement | Credential or privilege details | Credentialing guidelines have relaxed |

| Provider training | Ethics Code | Must be competent with telehealth delivery model | May be required to become credentialed | Specific training requirements completed | Many more providers qualify for telehealth, but still need to ensure proper training and competence |

| Outcomes | Ethics Code; insurance regulations | Must demonstrate that telehealth is as effective as in-clinic services | Needed for continued reimbursement and/or preauthorization | Relevant outcome measures throughout service | No change |

| Emergency procedures | Ethics Code | If there is an emergency with the client, providers must be able to contact authorities in the client’s district (dialing 911 will contact authorities in the provider’s district) | None | Client’s address; authority contact information for client’s district | No change |

| Provider wellness | Ethics Code | Providers should maintain self-care and be aware of “Zoom fatigue” | None | None | That most providers working are from home has blurred lines between work and home |

Note. Guidelines refer to legal, ethical, or professional documents that provide rules or regulations regarding these topics. Ethics Code = includes both the American Psychological Association and the Behavior Analyst Certification Board professional ethics codes; HIPAA = Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act; PHI = protected health information. Reimbursement considerations are based on what most third-party payers (e.g., health insurance) will reimburse. There are exceptions to some of these guidelines across states and insurance companies.

Table 2.

Specific actions that service providers can take to convert to telehealth

| Topic | Specific actions |

|---|---|

| Consent |

1. Verify that people providing consent are who they say they are (e.g., view their identification card). 2. Describe risks associated with confidentiality and privacy during consent. 3. Identify a HIPAA-compliant electronic signature service if first contact will be virtual. |

| Privacy |

1. Identify a HIPAA-compliant method of transmitting PHI to and from the client. 2. Ensure consent includes a discussion of privacy risks and procedures. 3. Ensure that the family is in a private area and/or permits others in the area to hear possible PHI. |

| Platform and equipment (Providers) |

1. Determine the requirements of insurance funders for telehealth services, which may require synchronous (live) audiovisual interaction. 2. Identify a HIPAA-compliant platform that meets requirements (may require a business associate agreement). 3. Obtain the necessary equipment based on the platform and insurance requirements for provider(s), which includes a secure (i.e., password-protected), Internet-enabled device with a webcam and microphone. 4. Obtain a headset for use in session to minimize privacy concerns and limit excess noise. |

| Client access |

1. Verify that the client has an Internet-enable device with a webcam and microphone, and if necessary, consider providing access. 2. Provide instructions on how to download or access the platform. 3. Provide guidelines and feedback on how to set up a therapy space at home (e.g., proper lighting, minimal distractions, chair, table). |

| Originating and distant sites |

1. Determine whether the client is eligible for reimbursement for telehealth. 2. If eligible, determine whether the client’s insurance company reimburses for facility-to-home telehealth. |

| Licensure and state restrictions |

1. Document the originating site for each client. 2. For out-of-state clients, review state licensure requirements for the originating site and check whether existing clients can continue via telehealth. 3. Determine whether temporary or full licensure in the originating site state is needed to provide services. |

| Credentials and privileges |

1. Follow insurance requirements for credentialing providers (may include a background check and update to liability insurance). 2. If part of a hospital or larger organization, check whether certain telehealth credentials or privileges are needed to practice. 3. Consider establishing a telehealth oversight committee to review and approve telehealth services in accordance with regulations. |

| Provider training |

1. Develop provider training for telehealth service delivery. 2. Evaluate provider competence (see the Appendix for an example of a competency checklist). 3. Ensure providers can coach the client through telehealth setup. |

| Outcomes |

1. Continue data collection of clinical (e.g., rates of problem behavior) and operational (e.g., cancellations, costs) outcomes in a manner that is comparable to in-clinic data collection. 2. Identify a HIPAA-compliant way to administer surveys, questionnaires, or other measures, as needed. |

| Emergency procedures |

1. At the start of each telehealth session, document the client’s exact address. 2. Maintain an easily accessible list of authorities’ contact information in the client’s district that you can call in the event of an emergency. |

| Provider wellness |

1. Frequently check in with employees regarding their wellness/mental health. 2. Incorporate opportunities for employees to connect and experience positive events (e.g., virtual happy hours, more frequent supervisory contact). 3. Be sensitive to employees’ schedules and competing demands (may require flexibility with scheduling clients and adequate breaks in between clients). 4. Encourage self-care activities. |

| Documentation |

1. Incorporate necessary documentation for telehealth services into existing documentation procedures. 2. Ensure information such as the platform, service delivery method (e.g., synchronous video), originating site, and emergency procedures is easily accessible and properly reported to insurance. |

Note. HIPAA = Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act; PHI = protected health information. These actions are based on ethical and legal guidelines and insurance regulations, as well as our experience in converting to telehealth.

Consent

Informed consent is a critical part of treatment and is clearly detailed in the professional ethics code of the APA (2017, Standard 3.10) and the BACB (2019, Code 9.03). Informed consent means that the client (usually the parent in the case of child behavior treatment) must have the capacity to make the decision, the provider must disclose potential risks, the client must understand the risks, and consent must be voluntary. For telehealth, there are special considerations. First, it is necessary to verify that the person providing consent is authorized to do so. In exclusive telehealth models, this can be more challenging, but it is typically completed by having caregivers provide photo identification (ID) in advance to match the name on the child’s medical record with the name on the ID, as well as match the photo on the ID with the identification of the person who connects during the session. Second, there are additional risks with respect to protected health information (PHI; more details in the Privacy section), which need to be clearly described to the client before obtaining consent. Third, the client needs to physically sign a consent-to-treat form as documentation that informed consent was obtained. Third-party electronic signature tools are available to assist with this, but it is necessary to establish a business associate agreement for such services. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been no major changes to consent. However, because many more providers are seeing clients exclusively via telehealth, following and documenting proper consent procedures are crucial.

Privacy

HIPAA, among other things, assures patients that their PHI will be secure. Sharing PHI with anyone not explicitly authorized could result in prosecution, loss of professional licenses, and/or job loss. Telehealth provides additional privacy and confidentiality risks (APA, 2013). Clients transmit audio, video, and text data via the Internet to providers. Therefore, the mechanism for transfer and storage needs to be encrypted and secure. Clients need to be made explicitly aware of the risks related to their PHI. The provider should verify during each session that the client is in a private area and who else, if anyone, is present. If others are present, the client must either consent for others to hear any PHI or must verify that, although present, others are not able to hear discussions. The Office for Civil Rights has temporarily suspended enforcement of HIPAA for telehealth such that violations will not be penalized during the COVID-19 crisis (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020a). This has allowed clients and providers more flexibility to quickly switch to telehealth. However, the suspension of HIPAA will likely not last for long, and it is important for providers to find HIPAA-compliant solutions and to obtain informed consent for using unsecured platforms.

Platform and Equipment (Providers)

There are many options for telehealth platforms. Telehealth can be delivered synchronously (e.g., a live video conference) or asynchronously (e.g., a recording). Different platforms may be better suited to each approach. The platform should be HIPAA compliant, which may require a business associate agreement between the provider organization and the platform company. Because of the military project, we have a business agreement with a widely used videoconferencing platform to ensure that all telehealth sessions are secure. There is currently some flexibility with respect to HIPAA (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020a), but providers should plan for when HIPAA will again be fully enforced. Reimbursement is also important to consider when choosing a platform. Most insurance companies only reimburse for synchronous therapy. Moreover, insurance companies generally define reimbursable telehealth as interactive audiovisual sessions; therefore, audio-only sessions, e-mail, and text messaging would not be covered. As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Coronavirus Preparedness Act (2020), these restrictions have temporarily been lifted, which means that telephone-only sessions, e-mail, and texts may now be reimbursable. The method of interaction must be clearly documented, however. Like the HIPAA suspension, this temporary allowance will likely not last, and it is important to plan for the eventual return to synchronous audiovisual models. From an ethical standpoint, it is also important to consider how the chosen platform will impact clients’ access to services. Once a platform is identified, providers must determine what equipment they need. In general, providers will need a secure, password-protected device that has (a) Internet access, (b) a webcam (which can be external), and (c) a microphone. For privacy, providers should also use a headset or earbuds if they are in shared space (the headset or earbuds may also produce better sound quality).

Client Access

Depending on the platform that is used, clients may need access to certain equipment. In general, clients will need access to a computer with a webcam or smart device with a camera in order to have an interactive audiovisual session. In addition, they need Internet access. These requirements could unintentionally limit access to services for underprivileged populations (e.g., low-income populations, certain ethnic and racial groups). If individuals do not have the proper equipment, it may be necessary to provide it for them. Currently, because insurance companies are reimbursing for standard telephone calls, clients at a minimum need a phone. Clients also must know how to navigate to the virtual therapy session. Providers (including support staff) should give detailed instructions and phone support to help clients log on to their sessions. Clients may also need assistance with setting up a proper therapy space in their homes. Providers should consider sending clients guidelines on where and how to set up the space. This may include things such as ensuring proper lighting (e.g., avoiding excess backlighting, which causes a glare), identifying and reducing distractions (e.g., turning off the TV, putting toys in a different room), and determining where to sit (e.g., at a table or desk with a chair).

Originating and Distant Sites

The originating site is the location of the client. The distant site is the location of the provider. Most insurance companies will only reimburse for services if the originating site is an approved health care facility, called facility-to-facility service. For example, clients unable to come to the specialty care facility could go to a local health care facility to connect with a specialist via telehealth. TRICARE covers home-to-facility services in which clients are in their homes, but most other insurers (pre-COVID-19) still required facility-to-facility therapy. In addition, some insurance companies may only reimburse for telehealth if the client lives in a rural area with limited access to providers. Based on these insurance regulations, it is important to document the originating site and, in some cases, the distance between the originating site and distant site. These details vary by insurance company and require careful review and negotiation. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the restrictions for originating sites have been lifted by the Coronavirus Preparedness Act (2020), and most insurance companies are reimbursing for home-to-facility care. It is unclear how long this will last.

Licensure and State Restrictions

Our clinicians are in Maryland and are all licensed in Maryland. They could see a client from any state provided that the client travel to Kennedy Krieger for an in-person session, but they cannot see clients who live in a state other than Maryland via telehealth unless they are licensed in the other state. With the COVID-19 pandemic, some state licensure restrictions have relaxed, but this differs by state and by licensure board. There are also discrepancies across federal and state levels. On the federal level, guidance suggests the state-line requirements can be waived (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2020; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020b). However, licensure is decided at the state level, and there is variation across the country regarding the recommended waivers. Some states have waived state-line licensure requirements temporarily and have allowed psychologists licensed in another state to treat clients via telehealth. Others have provided expedited temporary licenses to out-of-state providers. Still others have made no changes and are requiring providers to apply for full licensure. Moreover, in many states, telehealth across state lines is only permitted with established (not new) patients. Providers should carefully review and follow state regulations for the originating site of all clients.

Credentials or Privileges

Providers may need to become credentialed to practice via telehealth. Credentialing is necessary for reimbursement by many insurance companies and may require a background check, proof of licensure, and proof of liability insurance. In addition, providers working in a hospital setting may need to obtain telehealth privileges. Providers should check with insurance carriers and organization or company guidelines regarding credentialing or privilege requirements. For larger organizations, it may be necessary to establish a telehealth committee that reviews and approves telehealth services; this can ensure that all proper guidelines and regulations are followed. Smaller organizations may consider joining forces with others to form a clinical consortium to help keep track of evolving regulations. Many states and agencies have relaxed their credentialing guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic; however, it is important to establish expectations surrounding the competent delivery of telehealth services.

Provider Training

Delivering behavioral services via telehealth can be challenging, and providers must be competent in this service delivery model. Ethical codes for both the APA (2017, Section 2) and BACB (2019, Code 1.02) highlight the necessity to practice within the boundaries of one’s education and training. The APA provides further guidance on telehealth, which indicates that competency guidelines extend to service delivery models (APA, 2013). Therefore, specific training in telehealth is necessary and must be documented. As more providers are now engaging in telehealth services, it is important to develop, maintain, and document training requirements and competence. Training may include self-paced modules on telehealth service delivery and regulations and/or behavioral skills training approaches (e.g., role-play, feedback). The Appendix includes a sample provider telehealth competency checklist.

Outcomes

Throughout any treatment, it is important to document that the service is effective and produces meaningful outcomes (APA, 2013). With respect to telehealth, minimally, providers must be able to demonstrate and document that outcomes (e.g., effectiveness, efficiency, cost) are as good as in-person services. If not, it is likely necessary to switch to (or back to) in-person therapy. In addition to documenting changes in child behavior and collateral effects (e.g., parent functioning), it is also important to evaluate client and provider satisfaction with a telehealth service delivery model. Clearly this is important for ethical reasons, but it is also important for reimbursement purposes. Further, evaluation of these outcomes likely must occur online or virtually and must be done in a HIPAA-compliant manner. The COVID-19 pandemic has not specifically changed anything related to outcomes. However, as more providers are engaging in telehealth services, continued monitoring of outcomes is essential.

Emergency Procedures

In the event of an emergency, it is necessary to develop appropriate procedures (APA, 2013). Because the originating site may not be in the same jurisdiction as the provider, a call to 911 may not contact the appropriate authorities. Providers should create a running list of emergency contact numbers for the originating sites they serve. In addition, providers must obtain the client’s exact location at each appointment so that if there is an emergency, the information can be relayed to the authorities. There has been no change in this as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Provider Wellness

It is also important to recognize and address the impact of telehealth on provider wellness. Having done telehealth for several years, we feel that circumstances surrounding COVID-19 restrictions, rather than telehealth itself, are responsible for so-called Zoom fatigue (named after the Zoom platform, but applies to all videoconferencing platforms; Fosslien & Duffy, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way we do everything. Not only has it converted our services primarily to virtual delivery, but it has also altered the way we interact with our colleagues, our friends, and our families. There are important discussions to have to ensure that our providers—who are primarily working from home, trying to juggle professional requirements with personal issues (everyone working and schooling from home), and cut off from nonvirtual contact with their colleagues—are engaging in self-care behaviors that prevent burnout, protect against occupational safety risks, and allow for the stamina needed to reach our “post-COVID-19” reality. It is important to regularly be in contact with employees to assess their wellness. Employers should find ways to incorporate social interaction and positive events into the workday. It may be helpful to organize company or departmental events such as virtual happy hours or raffles. In addition, supervisors should consider increasing one-on-one virtual contact with employees. Surveying employees may help identify the type and frequency of interactions that they would prefer. Employers should be especially sensitive to providers’ schedules, with respect to both clients and competing demands (e.g., childcare), and ensure flexibility in scheduling and frequent breaks in between clients.

Documentation

Throughout Table 1, we have included considerations and regulations for documentation because it is pervasive throughout all topics. Here and in Table 2, we highlight some of the main considerations regarding documentation. Telehealth providers should use best practice documentation as they would for in-person sessions, but should include additional information pertaining to the telehealth delivery model. Each state, licensure board, and organization will likely have different requirements, but standard telehealth documentation includes noting who is present (and able to hear possible PHI) at each location, how the session was conducted (synchronous video and audio), and how the safety planning protocol was established and discussed (addressed under Emergency Procedures).

Scaling Up the Telehealth Delivery Model

For us, we started relatively small in 2016 with only one insurance company (TRICARE), seven clinicians, eight hybrid telehealth and in-clinic clients, and one exclusively telehealth client. This small start allowed us to establish the proper procedures and safeguards in a relatively controlled and intentional manner. Our information systems team selected our telehealth platform and established a business associate agreement to ensure that the platform was HIPAA compliant. We also worked with the institute’s legal team to develop our telehealth consent form and establish our secure electronic signature service process. The institute established a telehealth oversight committee, which regulated and approved telehealth services and projects across all departments. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the military project was the only telehealth project within the institute that provided direct clinical services in the home. As of mid-March 2020 (reflecting the time prior to the COVID-19 pandemic), there were 17 behavioral psychology clinicians participating in the military project and 99 clients who had received exclusive (n = 48) or hybrid (n = 51) telehealth services. In addition to clinicians, a dedicated staff within the department ensured that all regulations were properly followed. This process included sending annual consent forms to existing clients, new consent forms to new clients, and outcome measurement instruments to clients to track progress (sent at various points throughout and following treatment). These staff also audited clinical notes and billing documents to ensure that they were properly marked as telehealth and that emergency contact numbers were maintained for each jurisdiction. Moreover, they were responsible for tracking state legislation related to telehealth as it related to our clients (e.g., if a current client was moving out of state but wanted to continue telehealth services).

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, scaling up services was relatively straightforward because of the infrastructure we had in place for the military project. However, scaling up telehealth services still came with challenges, primarily in terms of time and resources. Our department went from 17 clinicians credentialed and trained to conduct telehealth to all licensed clinicians and trainees (117 total clinicians) delivering most sessions via telehealth. First, all staff and trainees who were not already trained needed to quickly reach a minimum competency. We offered a self-paced training to all clinicians, as well as criterion-based competency training for all trainees (doctoral interns and postdoctoral fellows). Trainees had a supervisor present during all telehealth appointments until minimum competencies were directly observed and documented. The Appendix shows the competency checklist items required before trainees could be cleared to conduct telehealth sessions without their supervisor present. Once a trainee is cleared, a supervisor must be available “on call” during all clinical appointments. After training all staff and trainees, we were able to quickly convert all of our clinicians to telehealth providers, due to the loosening of restrictions regarding telehealth reimbursement by the Coronavirus Preparedness Act (2020). Because of the huge increase in the number of clients seen via telehealth, several of our staff members were redeployed to initiate and maintain presession consent forms and documentation.

In addition, our department has provided continued assistance and guidance to other providers in the institute on transitioning to telehealth, such as psychologists in other areas (neuropsychology, trauma, autism), other mental health providers (social workers, professional counselors), nurses, psychiatrists, speech-language pathologists, physical therapists, and occupational therapists. The general preparations needed across these disciplines were the same, but the challenges included having to complete all required preparedness steps in a matter of days.

We recognize that many providers have already shifted their services to telehealth, which was greatly assisted by temporary changes in regulations. As it is anticipated that telehealth services may become a normal part of practice in the coming years and that loosened regulations related to HIPAA and insurance will likely not last, providers should now take the time to build the appropriate infrastructure and oversight of telehealth within their organizations. Providers new to telehealth can set up this infrastructure by studying and applying the guidelines provided in Table 1 and taking the specific actions detailed in Table 2.

Data and Reflections on Our Transition to Telehealth

Figure 1 shows the total number of appointments per week across our outpatient programs2 (solid gray line) starting in the first full week of January. The solid black line is the weekly number of in-clinic appointments, and the dashed black line is the weekly number of telehealth appointments. Until the week of March 16, 2020, appointments were relatively stable at between approximately 900 and 1,200 weekly appointments (M = 1,122.6), and nearly all (98.9%) were in-clinic appointments. Maryland schools closed on March 13, 2020, and the governor issued an executive order closing restaurants, bars, movie theaters, and gyms on March 16. That week (March 16), we saw a drastic decrease in appointments to 610 (a 45% reduction from the prior week). Moreover, our department had already begun the process of approving and training clinicians for telehealth services, and about a third of those appointments (n = 222) were telehealth appointments. By the following week, our appointments were nearly all telehealth (95.0%), and we began to reach pre-COVID-19 levels for total weekly appointment volume (994 appointments). By March 30, our appointments exceeded pre-COVID-19 levels by 119% and continued to increase throughout April to early June, reaching nearly 1,500 appointments per week (a surprising 30% increase in appointment volume relative to pre-COVID-19 levels). As a point of additional comparison, as compared to the same time period in 2019, the mean appointment volume from April to early June 2020 increased by over 40% (M = 1,023.7), with a corresponding increase in revenue and a surprising 300% increase in margins.

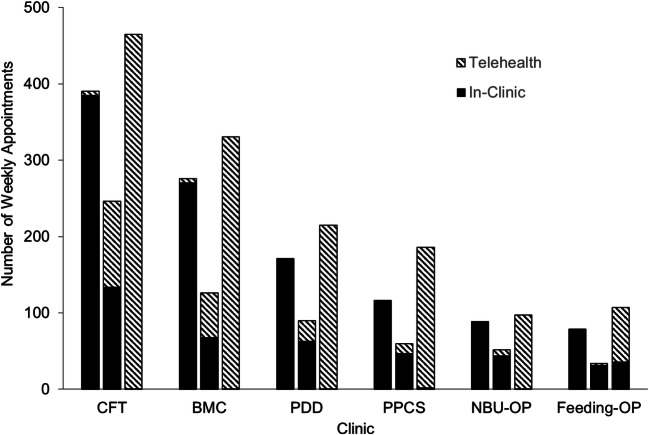

Figure 2 addresses the generality of the overall department-wide outcomes across all six distinct outpatient clinics. Specifically, Fig. 2 shows weekly appointment volume immediately prior to, during, and immediately after the departmental shift to telehealth for each outpatient clinic. Solid bars show in-clinic appointments, and striped bars show telehealth appointments. Each clinic has three bars; the first bar shows the mean weekly appointment volume from January 6 to March 9, 2020 (i.e., prior to the shift), the second bar shows appointment volume during the week of March 16 (i.e., when the shift was initiated), and the third bar shows the mean weekly appointment volume from March 23 to June 1 (i.e., after the shift). All clinics show a similar trend: primarily in-clinic appointments prior to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, a steep decline in all appointments during the week of March 16, and a rebound to prior appointment levels with a switch to primarily telehealth. This trend was even observed for our intensive outpatient programs: NBU and Feeding.

Fig. 2.

Weekly outpatient appointments by clinic before, during, and after telehealth shift. For each clinic, weekly appointment attendance is separated into three bars (first = mean prior to March 16, second = week of March 16, and third = mean after March 23). Solid black indicates in-clinic appointments and stripes indicate telehealth. CFT = Child and Family Therapy Clinic; BMC = Behavior Management Clinic; PDD = Pediatric Development Disability Clinic; PPCS = Pediatric Psychology and Consultation Service; NBU-OP = Neurobehavioral Unit Outpatient; Feeding-OP = Outpatient Feeding Disorders Program

Summary and Conclusion

In summary, in response to the public health emergency, like many behavioral health providers, we have quickly transitioned our services to a telehealth platform. This transition fortunately had the intended outcome, as well as an unanticipated one. The intended outcome was to adapt rapidly in order to save the clinical enterprise, both clinically and financially. In our case, hundreds of children and families per month who were in active treatment faced interruptions in services, loss of treatment gains, and potentially serious behavioral setbacks. Further, prolonged declines in revenue presented a financial threat to survival, which could have resulted in reductions in staffing and compounded the risk to fiscal viability. The unanticipated outcome was a 30%–40% increase in clinic volumes across the department and a surprising threefold increase in margins. The necessity to shift to such a high proportion of telehealth services allowed the inherent aspects and efficiencies of this form of clinical service to be documented and better understood.

We believe we were in an ideal position to do this rapidly because of three factors. The first has been discussed previously—namely, the experience with the telehealth regulations due to the military project. The second factor was that our clinical operation continuously obtained and analyzed data representing the “pipeline” of clinical activities, including client acquisition (marketing), intake and payment authorization, clinic and provider volumes, billing, collections, margins, and many more operational variables. Such data allow for both forecasting and tracking shifts along all parts of the pipeline over time (e.g., daily, weekly, monthly). The third factor was the history of staff response to these data, which represented a well-reinforced behavioral repertoire of staff and clinician behavior change in response to objective data vital to operations.

In addition, the rest of the institute, which did not previously offer any telehealth services directly in clients’ homes, was also able to convert quickly across many health disciplines using systems piloted in our department. The conversion of the Department of Behavioral Psychology was initiated first, followed soon after by the rest of the outpatient services of the entire institute, headed up and directed by a member of the Department of Behavioral Psychology. Data-analytic procedures used within our department were rapidly transferred and adapted across the institute in order to promote rapid increases in telehealth visits. Namely, systems were developed to analyze telehealth volumes currently as compared to the same time last year for both the entire institute and each clinical entity. Within a month, rapid transition began to occur across the various components of the institute, along with the same unanticipated outcome of increased clinical volumes with telehealth.

Based on these experiences, we have compiled the many considerations and moving parts associated with a telehealth program in the hope that this can help other providers build infrastructure to implement telehealth now and in the future. Many providers have been able to rapidly transition to telehealth thanks in large part to legislation and executive orders loosening HIPAA and insurance regulations. Although it is not clear when, sometime in the near future we expect telehealth regulations to change and result in a hybrid model of service delivery that does not simply revert back to previous, exclusively in-person care. ABA clinical services often consist of clinical organizations that cannot closely monitor and respond to regulatory changes. As change and the need to adapt are inevitable, a clinical consortium or professional organization can help ensure the continued success of ABA clinical programs by updating and distributing necessary rules and regulations for telehealth.

Author Note

The authors would like to thank the colleagues who helped pave our telehealth path over the last 4 years, especially Susan Perkins-Parks, Emily Shumate, Jaime Benson, Kristin McGue, Christi Culpepper, Kristi Phillips, Sara Hinojosa, Michelle Bubnik-Harrison, Jamila Ray, and Lauren O’Donnell. We also thank Danielle Forbus and Neha Karray, who provided clinical and data support during the first 2 years; Greg Miller for his technology expertise and guidance throughout this project; and Lana Warren for her contribution to the early conceptualization of this project.

Appendix

Telehealth Competency Checklist Items

| Skill Observed by Supervisor | |

| 1. Positions the camera for optimal viewing with the therapist’s face centered in the screen. | |

| 2. Establishes eye contact by looking at the camera instead of the screen throughout the session. | |

| 3. Obtains verbal consent to treat via telehealth if a telehealth addendum was not signed (i.e., reviews confidentiality and privacy precautions). | |

|

4. Takes privacy precautions, including: • using earbuds rather than computer speakers; • scanning the room to show the family your setting/who is present (if relevant); • introducing supervisors who may be joining remotely; and • putting a sign on the door to ensure privacy/lack of interruption. | |

| 5. Asks the family who is present at their location and whether or not they have a parent’s permission to possibly hear PHI. | |

| 6. Obtains or verifies the client’s physical location and backup telephone number. | |

| 7. Takes any individual or cultural considerations into account and establishes a plan for adapting the session via telehealth to meet client needs. | |

| 8. Maintains a professional environment throughout the session (background, professional attire). |

Note. Each skill is observed by a supervisor for new and existing clients.

Availability of Data and Material

The data sets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board (IRB) reviewed the procedures for the retrospective data analysis and acknowledged this study as quality assessment/quality improvement and therefore not human subjects research (IRB00251488).

Informed Consent

Not applicable; the study was identified as not human subjects research by the IRB.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable; the study was identified as not human subjects research by the IRB.

Code Availability

Not applicable; no code was used for this study.

Footnotes

The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) may also apply for providers working in schools.

Inpatient programs are by definition in-person only.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- American Psychological Association Guidelines for the practice of telepsychology. American Psychologist. 2013;68(9):791–800. doi: 10.1037/a0035001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/ethics/code/

- Austin JL, Groves EA, Reynish LC, Francis LL. Validating trial-based functional analyses in mainstream primary school classrooms. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2015;48(2):274–288. doi: 10.1002/jaba.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2019). Professional and ethical compliance code for behavior analysts. Retrieved from https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/BACB-Compliance-Code-english_190318.pdf

- Call NA, Wacker DP, Ringdahl JE, Cooper-Brown LJ, Boelter EW. An assessment of antecedent events influencing noncompliance in an outpatient clinic. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2004;37(2):145–157. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2020). COVID-19 emergency declaration blanket waivers for health care providers. Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/files/document/covid19-emergency-declaration-health-care-providers-fact-sheet.pdf#_blank

- Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2020, Pub. L. No. 116-123, 134 Stat. 145 (2020).

- Doehring P, Reichow B, Palka T, Phillips C, Hagopian L. Behavioral approaches to managing severe problem behaviors in children with autism spectrum and related developmental disorders: A descriptive analysis. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2014;23(1):25–40. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fosslien, L., & Duffy, M. W. (2020, April 29). How to combat Zoom fatigue. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2020/04/how-to-combat-zoom-fatigue

- Greer BD, Neidert PL, Dozier CL, Payne SW, Zonneveld KLM, Harper AM. Functional analysis and treatment of problem behavior in early education classrooms. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2013;46(1):289–295. doi: 10.1002/jaba.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyvaert M, Saenen L, Campbell JM, Maes B, Onghena P. Efficacy of behavioral interventions for reducing problem behavior in persons with autism: An updated quantitative synthesis of single-subject research. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2014;35:2463–2476. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissler SM, Tedijanto C, Goldstein E, Grad YH, Lipstich M. Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period. Science. 2020;368(6493):860–868. doi: 10.1126/science.abb5793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He J, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in US adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick RC, Merchant S, Perrin EC. Identification of developmental-behavioral problems in primary care: A systematic review. Pediatrics. 2011;128(2):356–363. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Totsika V, Hastings RP, Emerson E, Berridge DM, Lancaster GA. Behavior problems at 5 years of age and maternal mental health in autism and intellectual disability. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39(8):1137–1147. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9534-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020a). Enforcement discretion regarding COVID-19 community-based testing sites (CBTS) during the COVID-19 nationwide public health emergency. Retrieved from https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/notification-enforcement-discretion-community-based-testing-sites.pdf

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020b). Public health emergency declaration. Retrieved from https://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/legal/Pages/phedeclaration.aspx#_blank

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.