Abstract

Objective

To describe the current challenges of family caregivers during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic, the need for future digital innovations including involvement from professional nursing roles.

Data Sources

Review of recent literature from PubMed and relevant health and care reports.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused monumental disruption to health care delivery and care. Caregivers face unprecedented levels of uncertainty: both for the people they care for and for their own health and well-being. Given that many carers face poor health and well-being, there is a significant risk that health inequalities will be increased by this pandemic, particularly for high-risk groups. Innovations including those supported and delivered by digital health could make a significant difference but careful planning and implementation is a necessity for widespread implementation.

Implications for Nursing Practice

Carers need to be championed in the years ahead to ensure they do not become left at the “back of the queue” for health and well-being equity. This situation has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Disruptive change to health and social care is now required where digital health solutions hold considerable promise, yet to be fully realized.

Key Words: Informal carer, Digital technologies, COVID-19

Introduction

On March 11, 2020 the World Health Organization formally declared that Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus- 2 (SARS-CoV-2) or COVID-19 as a global pandemic.1 , 2 The disruption caused by COVID-19 has been unparalleled. Although the immediate impact on health and well-being demands urgent attention (reviewed elsewhere3, 4, 5) there remains growing concerns about the long-term impact of COVID-19, particularly within societal groups with preexisting conditions and those susceptible to poor health and well-being.

Informal carers (family members and friends looking after another person) are one such group. True champions of the COVID-19 pandemic, yet paradoxically “forgotten”.6 Recent review work suggests that policies developed to support informal carers throughout COVID-19 make false assumptions regarding health literacy levels, disease knowledge, psychological readiness, and medical care abilities.6 Further, collective knowledge of this group appears particularly inadequate; this is despite an obvious “pinch point” on the caring community due to COVID-19. Many individuals are facing additional pressures, not least conforming to local and national “lockdowns” and associated restrictions, which to some will translate to more time indoors, caring.

From the United Kingdom national statistics, it appears that almost half of the population (48%) provided help or support to someone outside of their household in April 2020; a significant increase from pre-pandemic levels of 11%.7 The pressure on this population is evident, even taking into account those relatively new to caregiving; U.K. national statistics have demonstrated significantly increased rates of feeling under strain compared to non-carers.7 For those who deliver caregiving with more permanency (eg, those caring for someone with a long-term condition such as cancer or dementia) there is an uncertain future. It is perhaps unsurprising that some are postulating that there is not just single crisis, but in fact three: (1) an acute health care crisis, (2) a health care recovery crisis, and (3) a social and economic crisis.8 Further, there is growing awareness that this pandemic is not an isolated event but a “syndemic” from which effects of COVID-19 are being felt in the most vulnerable throughout society, including the growing number of individuals with non-communicable disease.9

COVID-19 exerts nuanced short- and long-term challenges to our caregiver population, which are as yet poorly understood. We cannot afford to allow carers to end up as “passengers” in this roadmap. The support carers continue to provide needs to be urgently met with proactive approaches to health and well-being and constructive conversation. This opinion piece illustrates some of the short- and long-term challenges ahead, alongside potential avenues for digital health solutions. Although the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic may seem inevitable, this is not necessarily the case. To mitigate the risks we must: (1) Understand the carer demographic and the effect of COVID-19; eg, how have carers responded mentally and physically to the pandemic? (2) Innovate with caregivers and practitioners with rigorous evaluation of technology solutions capable of reaching the front line.

Short-Term Implications of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Informal Caregivers

Caregivers are a diverse group. Previous work in the area suggests that common groups for caregiving include those who are middle aged (eg, 35–65) and female.10 Some studies have suggested that carers report much higher degrees of social isolation and poorer quality of life compared with the general population.11 During the COVID-19 pandemic many caregivers have assumed extra roles, becoming the face of public health to those cared for: delivering and implementing messages around hygiene, social distancing, shielding, and providing reassurance.12 This is beyond the normal workload where up to 46% of caregivers report caring for 90 or more hours every week.10

As with all populations, caregivers are at risk of contracting COVID-19 through community transmission yet have added pressure to protect those who they care for. Although the population descriptors above do not necessarily place caregivers directly in the highest risk groups for COVID-19 (eg, people undergoing cancer treatments such as radiotherapy or chemotherapy, people with chronic and severe lung conditions, or those with serious heart conditions)13 they are reasonably likely to be caring for someone who is within these higher- or medium-risk groups. Caregivers are also likely themselves to have conditions of their own, including long-term conditions such as hypertension.14 , 15 National data from the United Kingdom suggests that 24% of caregivers consider themselves to have a disability.10 Even before the era of COVID-19, there is compelling evidence that caregivers face higher rates of psychological distress compared with non-carer comparison groups.16

The mental and physical health implications of the COVID-19 pandemic on caregiver communities are yet to be fully explored. What remains likely is that the severe disruption around health and well-being (eg, delays to diagnosis, treatments, increasing social isolation, inability to leave the house) is likely to have affected overall carer health and well-being. There are many at high-risk within the carer community such as those “shielding”, from Black and minority ethnic groups, and those facing social inequalities. Due to COVID-19 many caregivers will have changed habits around circadian rhythms, sleep, diet, exercise, alcohol consumption, and social activities. Although the development of a successful vaccination program is much needed—short-term social, health, and economic hardship will take time to recover from and could have lasting effect on individual families, communities, and carers.

Longer-Term Implications of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Informal Caregivers

The longer-term implications of COVID-19 on the caregiver community are particularly unclear; although for those who have already contracted the virus there remain significant questions regarding secondary complications (such as fatigue) over months if not years.17 Aside from COVID-19, there is already evidence that caregivers face a High risk of depression, stroke, and coronary heart disease18 and have a high percentage of overweight and obesity.19 National U.K. studies in caregiver populations found that one in five carers reported a preventable emergency hospital admission in the last year10 and observational studies have found that caregivers find it difficult to adhere to medical appointments and to prescribed treatments.20

Changes to daily behaviors (eg, shifts in our daily patterns, sleep, and stress) can have significant long-term effects on mental and physical health. Groups who are more susceptible to adverse effects of COVID-19 (eg, BAME groups) are already at a greater risk of sleep disparities and cardiovascular events in the first place.21 Collectively, this means that COVID-19 is presenting a sustained risk to our caregiver community and holds potential to further widen health inequalities. This being said, there may be some changes in behavior that are positive for health and well-being and some negative changes may not continue long-term. Such intricacies are why observational studies targeting the carer demographic are required: built with health and social care delivery partners in mind from the outset.

The Need for Innovation and Digital Solutions to Support Informal Caregivers

Technology solutions form a fast-moving spectrum of possibilities: online interventions, wearables, machine learning, big data; it is perhaps little surprise that concerns have been raised in the field in that technology developments are now outpacing rigorous research and evaluation.22 Although this can translate to the use of technologies with poor/no evidence for use in carers or over-engineering of solutions, solid science is still emerging. Such evidence includes psychosocial supports delivered online that have demonstrated clinically meaningful benefits for mental health outcomes including depression and anxiety.16 There is now considerable expansion internationally with appropriate cultural adaptation and personalization and delivery/evaluation in lower- and middle-income country settings.23

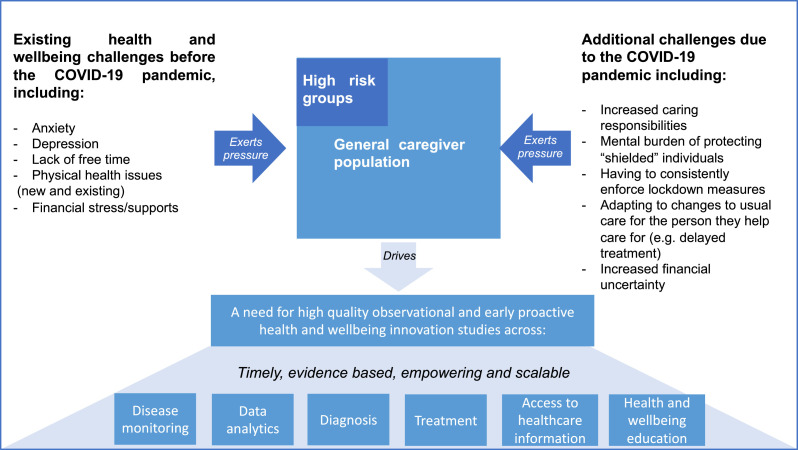

Given the plethora of technology options available there is much unrealized potential. U.K. national statistics report that four in five carers use digital technologies,10 and there remains a wealth of options across disease monitoring, data analytics, diagnosis, treatments, accessing health care information, and education and support (Fig. 1 ). Digital technologies, however, are no “silver bullet” and too few great concepts in technology reach the front line where there are significant questions on evaluation methodology.24 Understandably, there are many current efforts critiquing past failures, for which researchers are looking to develop robust approaches for successful implementation, cost effectiveness, and accessibility.16 , 25 , 26

Fig. 1.

Overview of the caregiver population and pressures faced both in general and because of the COVID-19 pandemic alongside some examples of targets for technology-based solutions.

Across all the research and practice questions above, the role and influence of the health care professional remains critical. This includes helping to identify caregivers, establishing unmet needs in caregivers, helping appraise the suitability of technologies from a health care viewpoint, and feeding back iteratively on how best to implement solutions. What is becoming increasingly feasible is that preventative, self-management, and triage approaches can become a reality for health and well-being in carers through the avenue of technology. The technology capability is already there; it is the infrastructure, human supports, and the ecosystem that need to be developed and proven effective. Success could mean a suite of evidence-based digital tools built to empower caregivers, protecting the health and well-being of this invaluable workforce, and leaving our societies much better prepared for future pandemics.

Conclusion and Implications for Nursing Practice

It is likely that the COVID-19 pandemic will have prolonged effects of the caregiver population in which health and well-being equity could become further from reach. Undoubtedly, clinical professionals will play a key day-to-day role in supporting patients and wherever possible their associated caregivers. However, increased demand on health and social care services, restricted budgets, alongside the potential for further lockdowns/restrictions means that innovations are sorely needed to champion and support “forgotten” caregivers in a timely manner. At a time when technologies are advancing quicker than rigorous evidence is being accumulated, the ideas, experience, and critique of health care professionals has never been more critical.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Sohrabi C, Alsafi Z, O'Neill N. World Health Organization declares global emergency: a review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) Int J Surg. 2020;76:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19: 11 March 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020. (Accessed August, 2020).

- 3.Maringe C, Spicer J, Morris M. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer deaths due to delays in diagnosis in England, UK: a national, population-based, modelling study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1023–1034. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30388-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heitzman J. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health. Psychiatr Pol. 2020;54:187–198. doi: 10.12740/PP/120373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Søreide K, Hallet J, Matthews JB. Immediate and long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on delivery of surgical services. Br J Surg. 2020;107:1250–1261. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan EYY, Gobat N, Kim JH. Informal home care providers: the forgotten health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395:1957–1959. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31254-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Office for National Statistics United Kingdom. 2020.

- 8.Raymond E, Thieblemont C, Alran S, Faivre S. Impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on the management of patients with cancer. Target Oncol. 2020;15:249–259. doi: 10.1007/s11523-020-00721-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horton R. Offline: COVID-19 is not a pandemic. The Lancet. 2020;396(10255):874. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32000-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carers UK. State of caring: 2019 report. http://www.carersuk.org/images/News__campaigns/CUK_State_of_Caring_2019_Report.pdf. (Accessed August, 2020).

- 11.Hayes L, Hawthorne G, Farhall J, O'Hanlon B, Harvey C. Quality of life and social isolation among caregivers of adults with schizophrenia: policy and outcomes. Community Ment Health J. 2015;51:591–597. doi: 10.1007/s10597-015-9848-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Onwumere J. Informal carers in severe mental health conditions: issues raised by the United Kingdom SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0020764020927046. 0020764020927046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NHS. Who's at higher risk from coronavirus. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/coronavirus-covid-19/people-at-higher-risk/whos-at-higher-risk-from-coronavirus/ . (Accessed August, 2020).

- 14.Perlick DA, Hohenstein JM, Clarkin JF, Kaczynski R, Rosenheck RA. Use of mental health and primary care services by caregivers of patients with bipolar disorder: a preliminary study. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:126–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Torimoto-Sasai Y, Igarashi A, Wada T, Ogata Y, Yamamoto-Mitani N. Female family caregivers face a higher risk of hypertension and lowered estimated glomerular filtration rates: a cross-sectional, comparative study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:177. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1519-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schulz R, Beach SR, Czaja SJ, Martire LM, Monin JK. Family caregiving for older adults. Annu Rev Psychol. 2020;71:635–659. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010419-050754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rimmer A. Covid-19: impact of long term symptoms will be profound, warns BMA. BMJ. 2020;370:m3218. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grant M, Ferrell B. Nursing role implications for family caregiving. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2012;28:279–282. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beesley VL, Price MA, Webb PM. Loss of lifestyle: health behaviour and weight changes after becoming a caregiver of a family member diagnosed with ovarian cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1949–1956. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-1035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X, Robinson K, Hardin H. The impact of caregiving on caregivers' medication adherence and appointment keeping. West J Nurs Res. 2014;37:1548–1562. doi: 10.1177/0193945914533158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Egan KJ, Knutson KL, Pereira AC, von Schantz M. The role of race and ethnicity in sleep, circadian rhythms and cardiovascular health. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;33:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bucci S, Schwannauer M, Berry N. The digital revolution and its impact on mental health care. Psychol Psychother. 2019;92:277–297. doi: 10.1111/papt.12222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pot AM, Gallagher-Thompson D, Xiao LD. iSupport: a WHO global online intervention for informal caregivers of people with dementia. World Psychiatry. 2019;18:365–366. doi: 10.1002/wps.20684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray E, Hekler EB, Andersson G. Evaluating digital health interventions: key questions and approaches. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51:843–851. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lapid MI, Atherton PJ, Clark MM, Kung S, Sloan JA, Rummans TA. Cancer caregiver: perceived benefits of technology. Telemed J E Health. 2015;21:893–902. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2014.0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenhalgh T, Wherton J, Papoutsi C. Beyond adoption: a new framework for theorizing and evaluating nonadoption, abandonment, and challenges to the scale-up, spread, and sustainability of health and care technologies. J Med Internet Res. 2017;19:e367. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]