Abstract

In this work, a dielectrophoretic impedance measurement (DEPIM) lab-on-chip device for bacteria trapping and detection of Escherichia coli, Vibrio cholerae, and Enterococcus is presented. Through the integration of SU-8 negative photoresist as a microchannel and the precise alignment of the SU-8 microchannel with the on-chip gold interdigitated microelectrodes, bacteria trapping efficiencies of up to 97.4%, 97.7%, and 37.7% were achieved for E. coli, V. cholerae, and Enterococcus, respectively. The DEPIM device enables a high detection sensitivity, which requires only a total number of 69 ± 33 E. coli cells, 9 ± 2 Vibrio cholera cells, and 36 ± 13 Enterococcus cells to observe a discernible change in system impedance for detection. Nonetheless, the corrected limit of detection for Enterococcus is 95 ± 34 after taking into consideration the lower trapping efficiency. In addition, a theoretical model is developed to allow for the direct estimation of the number of bacteria through a linear relationship with the change in the reciprocal of the overall system absolute impedance.

INTRODUCTION

One of the greatest threats to the marine environment is the introduction of foreign invasive marine species through the discharge of ballast water at destination ports.1 The discharge of ballast water at the port of destination disturbs the local marine ecology as ballast water contains harmful marine species and organisms carried over from the port of origin.2 These non-indigenous marine species could generate massive ecological damage and economic and health problems. An estimated 3000–4000 × 106 tons of untreated ballast water are discharged from ships every year in destination ports.3 Hence, it is inevitable that marine ports in the world are exposed to the threat of harmful foreign marine organisms brought in by hundreds of thousands of ships from all over the world every year.

The ballast water management (BWM) convention 2004 was organized by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) to address the issues of water quality of ballast water. The IMO demands that under D-2 regulation, seawater should be adequately treated with ballast water management systems (BWMS) such as mechanical filtration or sterilization with ultraviolet and heat treatment prior to ballast water discharge at the port of destination. The IMO's BWM 2004 was enforced from 8 September 2017. The IMO D-2 standard addresses the issues of water quality of ballast water and dictates the maximum allowable micro-organisms of various sizes ranging from 10 to 50 μm and three harmful bacteria—Escherichia coli (E. coli), Vibrio cholera, and Enterococci.

Port state control (PSC) could perform either an indicative analysis or a detailed analysis of the ballast water. A full compliance test may involve large scale ballast water sampling and require a specialist on-board assisting PSC officer. The current state-of-the-art ballast water micro-organism full compliance tests includes microscopic examination and fluorometry, such as the fluorescence-di-actate (FDA), pulse-amplified-modulation (PAM), adenosine-triphosphate (ATP), and fluorescence-in situ-hybridization (FISH) fluorometry.4 However, the drawbacks of the conventional fluorometry techniques, such as the FISH method, requires ∼8 h from sample to qualitative and quantitative results for the detection of Escherichia coli.5 Furthermore, as the sample has to be transported to the laboratory for these onshore compliance tests, the lead time from ballast water sampling to the final report could take up to several days.

On the other hand, portable water test kits were developed to perform indicative ballast water compliance tests. For example, marine potable water test kits for coliform/E. coli bacteria were made available by Lovibond, Parker Kittiwake, and DTK Water. Nonetheless, these kits use dipslides to detect visible color changes under fluorescence or UV light, after an incubation period of 24 h, for indicating the presence of coliforms and E. coli bacteria. Likewise, the ScanVIT E. coli/Enterococci bacteria test kit, which is based on the FISH fluorometry technique, requires a 12-h time-to-result test.6 Another portable indicative test tool B-QUA is an ATP-based detection device. Nevertheless, the B-QUA device detects the cATP activity level and provides a qualitative indication of “most likely compliant,” “close to limit,” and “most likely non-complaint” in 1 h. In other words, there are imminent demands for access to fast, sensitive, and reliable on-board testing tools for ballast water bacteria compliance tests.

The advancement in microfluidics lab-on-chip technologies has enabled a myriad of new applications in the bioengineering field such as cell sorting, immunoassay, bacteria, and virus detection.7–9 An integrated microfluidics system using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) molecular analysis realized Escherichia coli (E. coli) bacteria detection with sensitivity ranging from 104 to 106 total colony-forming units (CFUs) in 1 h.10 Among others, the dielectrophoretic impedance measurement (DEPIM) technique was introduced for selective bacteria detection.11–17 The electropermeabilization-assisted dielectrophoretic impedance measurement (EPA-DEPIM) method was developed to enhance the detection sensitivity of DEPIM by irreversibly breaking down the bacteria cell membrane to release intracellular ions by a pulsed high electric field, thus giving a higher signal-to-noise ratio.18

In this paper, a DEPIM lab-on-chip device for Escherichia coli, Vibrio cholera, and Enterococci bacteria trapping and detection is presented. In order to improve the detection sensitivity and measurement time compared to conventional DEPIM devices, we attempt to achieve 100% trapping of incoming bacteria by employing an SU-8 negative photoresist as the microchannel layer and a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) backing layer for fluidic sealing through semi-permanent bonding. Through the precise alignment of the SU-8 microchannel layer with the on-chip gold interdigitated microelectrodes, we are able to ensure that all incoming bacteria pass through the microelectrode DEP trapping region, thus achieving higher bacteria trapping efficiency and limit of detection. In addition, a new theoretical model to quantitatively predict the amount of bacteria present in a sample is developed. We validated experimentally the linear relationship obtained between the number of deposited bacteria with the change in the reciprocal of the overall system absolute impedance.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Device design and fabrication

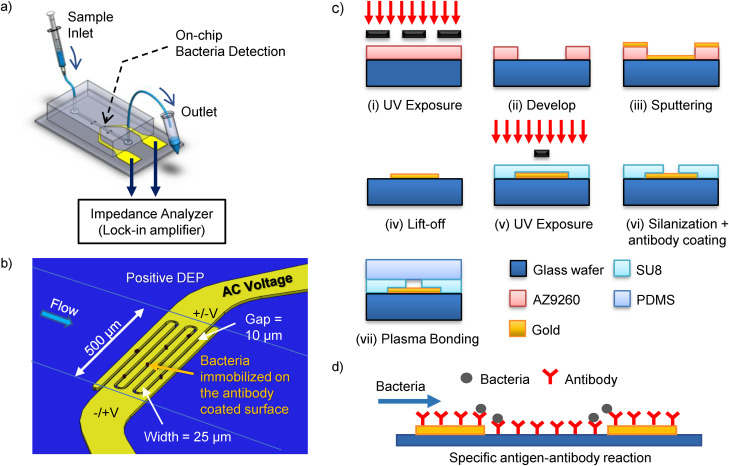

The schematic diagram of our bacteria detection device is shown in Fig. 1(a). The device comprises of a lab-on-chip microfluidics device with gold interdigitated microelectrodes and an impedance analyzer for impedance measurements. The microelectrodes, shown in Fig. 1(b), were fabricated in a cleanroom using standard photolithography techniques [Fig. 1(c)(i–iv)] (see the supplementary material for more details). The interdigitated microelectrodes have three pairs of fingers; each finger has a width and a gap of 25 μm and 10 μm, respectively. The microelectrodes on the glass surface were coated with rabbit polyclonal immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody to E. coli (ab137967, for “O” and “K” antigenic serotypes, Abcam, USA), Vibrio cholerae (ab79794, for somatic O1 antigen Factors A, B, and C, Abcam, USA), and Enterococcus (ab68540, for Enterococcus faecium, Abcam, USA) in separate microchips for their respective bacteria binding. The antibody was diluted in the ratio of 1:10 in sodium bicarbonate solution at pH 9.4 to a final concentration of 500 μg ml−1. An aliquot of 50 μl was pipetted to each of the microelectrodes on a glass wafer and left to coat overnight at 4 °C (Fig. S1 in the supplementary material), followed by washing with 1× PBS. Subsequently, a slab of ∼7 mm thick polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS, Sylgard 184, Dow Corning Inc.) was cured and punched with 1.5 mm holes (Harris Uni-Core puncher, USA) at the inlet and outlet for the fluidic connection. The PDMS slab seals the exposed top opening of the SU-8 microchannel through plasma bonding (PDC-002, Harrick Plasma, USA) [Fig. 1(c)(v–vii)]. The plasma RF power was set to maximum for 60 s for the surface activation. Nonetheless, the bonding between the SU-8 microchannel layer and the PDMS slab is semi-permanent. In other words, due to the weaker bonding than a typical PDMS–PDMS or PDMS–glass configurations, the highest flow rate is limited to a maximum of 5 μl min−1 to avoid bonding delamination or fluid leak.

FIG. 1.

(a) Schematic diagram for the integrated lab-on-chip rapid bacteria detection device. The device comprises of a microfluidics chip with interdigitated microelectrodes and an impedance analyzer for impedance measurements. (b) Channel and microelectrode configuration. The microelectrodes for the bacteria DEPIM trapping and measurements have a width and gap of 25 μm and 10 μm, respectively. Bacteria are attracted toward the surface of the electrode through positive DEP. (c) Photolithography procedures for the device fabrication: (i)–(iv) AZ9260 patterned on the glass wafer, followed by sputtering and lift-off to fabricate gold microelectrode onto glass wafer; (v) and (vi) a SU8 layer with a width of 500 μm and height of ∼20 μm is precisely aligned and patterned onto the interdigitated microelectrode to form the microchannel walls, followed by silanization and antibody coating; and (vii) a PDMS slab is plasma bonded to form a complete microchannel on-chip. (d) The glass surface of the microchannel is coated with the specific antibody for bacteria binding through a specific antigen–antibody reaction.

Experimental setup and device operation

The photograph of the DEPIM lab-on-chip device is shown in Fig. S2 in the supplementary material. Each wafer has eight independent integrated sets of microchannels and interdigitated microelectrodes for bacteria detection. There are two large square contact pads for each of the microelectrodes, with both width and length of 5 mm, for establishing electrical connection with the impedance analyzer via spring-loaded test probes (PA3FS, Coda pins). Impedance measurements are made using an impedance analyzer (MFLI 5 MHz lock-in amplifier, Zurich Instrument, Switzerland). The impedance readouts were obtained from LabOne® software bundled with the lock-in amplifier, and the saved data were processed and visualized in Matlab® (MathWorks, Inc., USA). The frequency used for the bacteria DEP trapping and impedance measurements was set to 5 MHz, and the peak to peak voltage is set between 0.1 Vpp and 5 Vpp. Bacteria samples were infused at a constant flow rate of 1 μl min−1 into the microchannel through the inlet via a syringe pump (Pump 11 Pico Plus Elite, Harvard Apparatus, USA) and microbore tubing (Tygon® 06419-01, Cole-Parmer). The waste suspension medium exits at the outlet for disposal. The device is designed for single experiment use and to be discarded according to standard biology laboratory protocol.

Bacteria culture and preparation

The bacteria used for the experiments were E. coli K-12 strain (ATCC© 29947™), Vibrio cholerae bacteriophage III (ATCC© 51352-B8™), and Enterococcus faecium NCTC 7171 (ATCC© 19434™) bought from ATCC, USA. E. coli bacteria were cultured for 24 h in a shaking incubator at 37 °C and 250 rpm in 5 ml of BD Difco™ nutrient broth (8.0 g l−1, BD 234000). Similarly, Vibrio cholerae were cultured in the same medium, except with the addition of sodium chloride (5.0 g l−1, NaCl, S7653 Sigma-Aldrich). Enterococcus faecium was cultured in Brain Heart Infusion broth (37.0 g l−1, BD 237500) at 37 °C and 250 rpm for 24 h. Before the experiment, 10 μl of antibody was added to each of the respective bacteria samples, unless or otherwise specified. See the supplementary material for more details on the sample preparation and bacteria concentration counting.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Bacteria trapping efficiency

With the help of the integrated lab-on-chip device shown in Fig. 1, bacteria are first focused and trapped onto microelectrodes using DEP forces. DEP induces the movement of bacteria through the polarization effect under a non-uniform electric field. As the bacteria have higher permittivity than the suspending medium, the bacteria move toward the region of a stronger electric field by means of positive DEP. Hence, it is possible to focus and trap bacteria in a microfluidic chamber for detection. Through the integration of SU-8 negative photoresist as a microchannel, we were able to precisely align the microchannel with the on-chip interdigitated microelectrodes (Fig. S3 in the supplementary material). This ensures that all incoming bacteria pass through the channel's electrode, i.e., the bacteria detection zone at the microelectrode gaps, for DEP trapping and detection. The constant flow rate of 1 μl min−1 is chosen to ensure that the microchannel remains intact during the experiment, while ensuring that the bacteria trapping efficiency is near 100%. We observed under a microscope that at a flow rate of 5 μl min−1, quite a number of bacteria escaped the trapping zone as such a high flow results in the bacteria flowing through the electrode region before they had the opportunity to travel downward to the bottom channel wall and get trapped onto the electrodes.

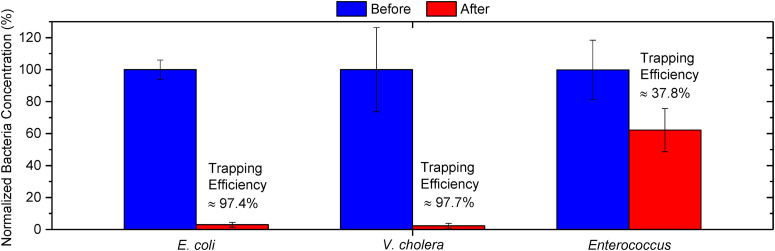

The trapping efficiency of bacteria, TE, is defined as the ratio of the number of bacteria trapped on the microelectrode through DEP to the total number of incoming bacteria into the microchannel, which can be expressed as , where cin and cout are the bacterial concentration collected at the inlet and outlet of the microchannel, respectively. The trapping efficiencies for E. coli, Vibrio cholera, and Enterococcus in the de-ionized (DI)-water suspension are shown in Fig. 2. The blue bar represents the normalized bacteria concentration collected at the inlet, while the red bar represents the normalized bacteria concentration at the outlet. The error bar shows the standard deviation. E. coli, Vibrio cholera, and Enterococcus were infused independently into separate sets of microchips with new microelectrodes at a flow rate of 1 μl min−1 with an applied DEP AC voltage of 5 Vpp, frequency of 5 MHz, and sample concentration of ∼104 CFU ml−1 for 50 min. After which, 50 μl of samples were collected at the inlet's and outlet's tubing and diluted ten times in DI-water. The bacteria concentrations before and after flowing through the device were estimated through colony-forming units formed on nutrient agar (N = 5). Bacteria concentrations for these samples were normalized by the average bacteria concentration collected at the inlet.

FIG. 2.

Trapping efficiency of E. coli, Vibrio cholera, and Enterococcus bacteria in the DI-water suspension medium at a flow rate of 1 μl min−1 at DEP AC voltage of 5 Vpp and frequency of 5 MHz, and sample concentration of 104 CFU ml−1. The bacteria concentrations at the inlet and outlet were evaluated through CFU counting on an agar plate (N = 5), where the error bar shows the standard deviation. Near perfect trapping efficiencies of 97.4% and 97.7% were achieved for E. coli and Vibrio cholera, respectively. Nonetheless, the trapping efficiency for Enterococcus was substantially lower at 37.8%.

The DEP force exerted on a bacterium can be expressed as , where r is the equivalent radius of the bacterium, Erms is the root-mean-squared electric field strength, ɛm is the medium permittivity, and Re[K*(ω)] represents the real part of the Clausius–Mossotti (CM) factor, which depends on the complex permittivities of the bacteria and medium. The bacteria samples are resuspended in DI-water instead of the culture medium. The former produces a larger DEP force through enlarging the product of ɛm and Re[K*(ω)], thus achieving a higher trapping efficiency. The ability to achieve high trapping efficiency is of pivotal importance for high sensitivity bacteria detection. Near perfect trapping efficiencies of 97.4% and 97.7% were achieved for E. coli and Vibrio cholera, respectively. Nonetheless, the trapping efficiency for Enterococcus was substantially lower at 37.8%.

The sub-optimal trapping of Enterococcus is due to the limitation of the maximum frequency (5 MHz) of our impedance analyzer. The CM factor determines whether the DEP force is repelling or attracting the cell.19 At low frequency (from a few kHz to a few MHz), the CM factor is negative, and hence a negative DEP force is repelling the cell; at mid-frequency, the CM factor becomes positive, and hence DEP force attracts the cell toward electrodes. Finally, at extremely high frequency, the CM factor and DEP force switch to negative again. While previous literature demonstrated negative DEP of Enterococcus at a frequency of 1 MHz,20 we observe that at 5 MHz, the DEP force starts to trap Enterococcus cells. We infer that the sign of Enterococcus's CM factor first switched from negative to positive at the frequency in-between 1 MHz and 5 MHz, and at 5 MHz, the DEP force acting on the Enterococcus microbes are relatively weak. We suggest that future experiments should be performed at higher AC frequency to increase the trapping efficiency for Enterococcus.

Bacteria detection

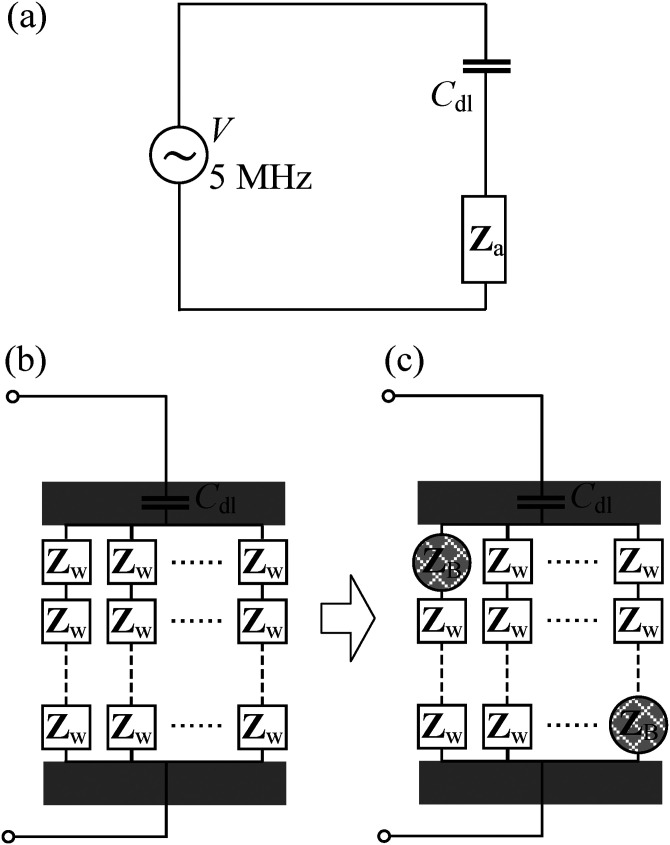

While the DEP force attracts the bacteria toward the microelectrode gap on the glass surface, the bacteria will escape from the microelectrode when the DEP force is turned off. Therefore, in order to detect the presence of a particular bacteria type, the specific antibody of that bacteria is coated on the microelectrode surface and acts to bind the bacteria of interest through specific antibody–antigen reaction. After the binding of the bacteria on the microelectrode glass surface, the bacteria are then detected using DEPIM, as bacteria often exhibit different electric properties compared to the surrounding fluid.21,22 We model the DEPIM circuit as a serial connection of two impedance components [Fig. 3(a)] such that the overall impedance, Ztot, can be represented as

| (1) |

where Cdl corresponds to the capacitance due to the electric double layer formed on the surfaces of the electrode pairs,23,24 which can be neglected at high frequency,25,26 leading to Ztot = Za; ω is the angular frequency of the applied AC source; j is the imaginary unit; and Za represents the impedance of the suspension medium flowing through the microchannel, the number of deposited bacteria, and the way they aligned in-between the interdigitated microelectrodes gap.

FIG. 3.

(a) The equivalent circuit of our DEPIM device, where the capacitance of the electric double layer, Cdl, is in serial connection with the impedance of the suspension medium Za. (b) Detailed model of the equivalent circuit before the deposition of bacteria, where Za is treated as parallel connections of N chain. Each chain composed of a serial connection of M impedance blocks, and Zw represents the impedance of each block. Each block has a similar size as an individual bacterium. (c) Detailed model of the equivalent circuit after the deposition of bacteria, where the volume initially occupied by the medium is replaced by bacteria with impedance ZB.

Escherichia coli detection

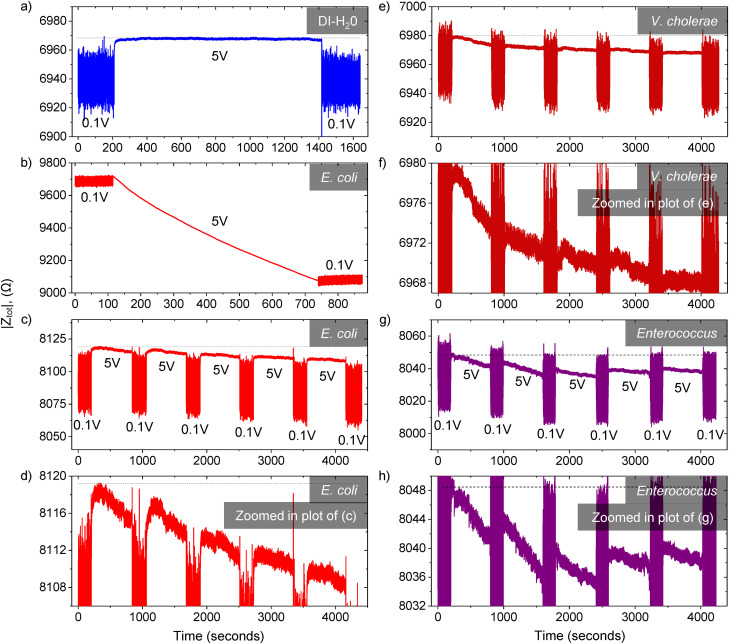

The DEP impedance measurements for (a) DI-water, (b) ∼106 E. coli CFU ml−1, and (c) ∼104 E. coli CFU ml−1 are shown in Fig. 4. All experiments were carried out on fresh new chips at a frequency of 5 MHz and a constant flow rate of 1 μl min−1 in DI-water as a suspension medium. Applying an AC voltage of 0.1 Vpp induces an extremely weak DEP force on the trapped bacteria, which is insufficient to trap or hold any bacteria other than E. coli and thus is equivalent to turning off the voltage source (see Antibody Specificity section and Figs. S5–S8 in the supplementary material for more information). Henceforth, we refer to the voltages of 5 Vpp and 0.1 Vpp as the “ON” and “OFF” states, respectively. First, when the microchannel was infused with DI-water only, the impedance transient response was flat as there was no deposition of E. coli, which represent the case where there is no bacteria detected [Fig. 4(a)]. Second, when the microchannel is infused with a high concentration E. coli of ∼106 CFU ml−1, the absolute impedance of the overall system, |Ztot|, decreased significantly from 9716 Ω to 9077 Ω in 10 min. (t-test, ), which corroborates the idea of E. coli detection through the relative change in the system impedance [Fig. 4(b)]. In addition, we noticed that the starting point of the |Ztot| differs from chip to chip. This difference could be due to the inherent variation in the microfabrication process. However, as our system detects bacteria based on detecting a relative change or decrease in |Ztot|, the variation of chip-to-chip impedance is unimportant. The baseline impedance can be taken at the start of the application of DEP “ON” voltage of 5 Vpp, where there is little to no bacteria deposition at the beginning of the experiment.

FIG. 4.

DEP impedance measurements. The applied DEP AC voltage of 5 Vpp and 0.1 Vpp represents the “ON” and “OFF” states, respectively. All experiments were carried out at a frequency of 5 MHz and a constant flow rate of 1 μl min−1 in DI-water as a suspension medium. (a) For DI-water only, the impedance response is flat as there was no deposition of E. coli bacteria, which represents the case where no bacteria are detected. (b) When the microchannel is infused with high concentration E. coli of 106 CFU ml−1, the absolute impedance decreased substantially. (c) The limit of detection of the device is tested with the 104 CFU ml−1 E. coli sample. The AC source voltage was applied in repeated blocks of “OFF”—200 s and “ON”—10 min. Due to the specific immobilization of E. coli bacteria through antibody–antigen reaction, the impedance continued to decrease gradually with time as more E. coli got trapped. (d) The zoomed in plot of the impedance response of subplot (c). (e) Bacteria detection test for the 103 CFU ml−1 Vibrio cholerae sample in a chip coated with Vibrio antibody. (f) Zoomed in plot of (e). (g) Bacteria detection test with ∼104 CFU ml−1 Enterococcus sample in chip coated with Enterococcus antibody, (h) Zoomed in plot of (g).

Subsequently, we tested the device limit of E. coli detection with the ∼104 CFU ml−1 E. coli sample [Fig. 4(c)]. The DEP AC voltage was applied in repeated blocks of “OFF”—200 s—and “ON”—10 min. The zoomed in plot of the impedance response of subplot (c) is shown in Fig. 4(d). The reason to include a voltage “OFF” period of 200 s was to assure that the change in impedance was solely due to the deposition of E. coli bacteria that were remain trapped through the specific E. coli antibody–antigen reaction. Any other bacteria present would be released and flushed to the channel outlet during the “OFF” period. The absolute impedance |Ztot| continued to decrease gradually with time from ∼8118 Ω to 8108 Ω over five voltage blocks. Nonetheless, after the first voltage block, there was already a significant decrease in the overall system absolute impedance. From the bacteria CFU counting on nutrient agar plates (N = 10), the actual E. coli bacteria concentration was estimated to be 6.9 ± 3.3 CFU μl−1. Therefore, since the buffer flow rate was 1 μl min−1, the total number of bacteria required to observe a discernible change in system impedance in one voltage loop was merely 69 ± 33 E. coli bacteria. In other words, our device is able to achieve a high sensitivity specific E. coli detection; the detection limit is only dependent on the number of bacteria trapped on the electrodes rather than the bacterial concentration of the infused solution.

Vibrio cholera and Enterococci detection

The bacteria detection test with the 103 CFU ml−1 Vibrio cholerae sample in a chip coated with Vibrio cholerae antibody is shown in Fig. 4(e). The AC source voltage was applied in repeated blocks of “OFF”—200 s—and “ON”—10 min. Similar to the above-mentioned E. coli experiment, we observed no changed in the impedance response of the chip over three blocks for DI-water (see Fig. S10 in the supplementary material) due to no bacteria deposition in the DI-water sample. When infused in the Vibrio cholera sample solution, we observed that first, the deposition of per V. cholera leads to a higher drop in the impedance response than E. coli [compare the gradients of Figs. 4(c) and 4(e)]. This is due to the fact that the size and composition of individual bacterial species, and hence their electrical properties, vary greatly among each other. Second, we observed from the zoomed plot in Fig. 4(f) that there is a discernable change in the total impedance after the first voltage loop of 10 min and it continues to decrease with subsequent voltage loops. The limit of detection for Vibrio cholerae bacteria based on the total number of incoming Vibrio cholerae bacteria in 10 min was 9 ± 2 (based on agar plating, N = 4).

Similarly, we evaluated the limit of detection for Enterococcus. Figure 4(g) shows the total impedance response for the ∼104 CFU ml−1 Enterococcus faecium sample in a chip coated with Enterococcus antibody. From agar CFU count (N = 8), the limit of detection for Enterococcus was 36 ± 13 after one voltage loop in 10 min. However, due to the lower bacteria trapping efficiency of 37.8%, the corrected limit of detection for Enterococcus bacteria is 95 ± 34. As the dielectrophoresis trapping force for bacteria depends on the applied voltage and frequency, the trapping efficiency of Enterococcus bacteria was limited by the maximum frequency of 5 MHz of our lock-in amplifier. Future work could be done to improve the Enterococcus trapping efficiency from two perspectives, either modifying the chip configuration by reducing the microchannel height and increasing the number of the interdigitated microelectrode fingers, or connecting our device to an impedance analyzer with higher voltage and frequency range to increase the magnitude of the trapping force.

Theoretical model for bacteria quantification

In order to determine the relationship between the overall impedance of the DEPIM circuit and the number of bacteria deposited on the electrode, we modeled the system equivalent circuit shown in Fig. 3(a). Before the deposition of bacteria, the fluid in-between the two electrodes is divided into multiple blocks of similar size to bacteria, and Zw represents the impedance of each block. The impedance, Za, is a parallel connection of N chains, in which each chain involves a serial connection of M impedance blocks [Fig. 3(b)]. After bacteria are infused into the microchannel and trapped on the edge of the electrodes, the volume initially occupied by the medium is replaced by individual bacteria. Due to the extremely low amount of deposited bacteria at the detection limit, it is reasonable to assume that there exists at most one bacterial block per chain [Fig. 3(c)]. Therefore, the impedance, Za, is given by the following expression:

| (2) |

where n denotes the number of deposited bacteria. Before any bacteria are trapped on the electrode (n = 0), Eq. (2) is simplified to be Za = MZw/N, which is in line with our observation that the smaller distance of the electrode gap (smaller M) and more pairs of electrodes (larger N) lead to smaller overall impedance. Taking the derivative of 1/Za with respect to n leads to

| (3) |

independent of n, where C = f(M, Zb, Zw) is a complex constant that depends on the configuration of the interdigitated electrodes and the electric properties of bacteria and medium. In other words, the magnitude of the reciprocal of the Za impedance is linearly proportional to n, . Utilizing this linear relationship, the number of trapped bacteria can be estimated by

| (4) |

which is linearly proportional to the change in the reciprocal of the absolute impedance of the system, where K is a constant that only depends on the electrode configuration and electric properties of the suspension medium.

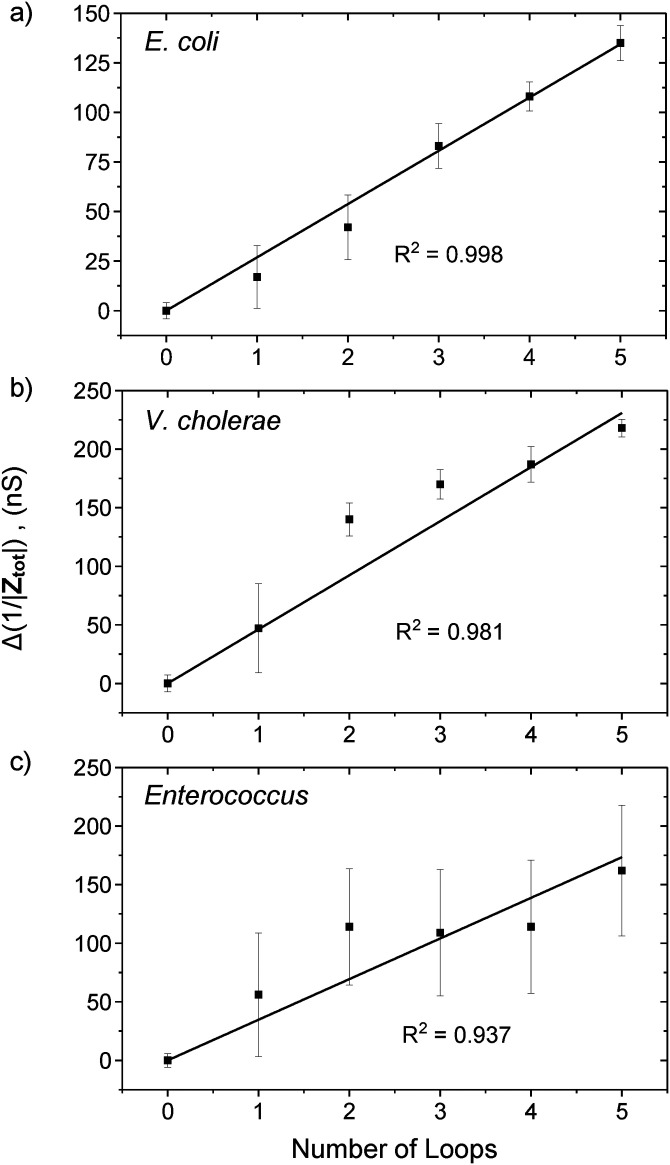

The variation of 1/|Ztot| with the number of voltage loops for E. coli, V. cholerae, and Enterococcus are shown in Fig. 5. The data points were computed from the average and standard deviation of the overall system absolute impedance for each of the DEP 10 min “ON” loops from Fig. 4. The system conductance for E. coli, V. cholerae, and Enterococcus increases with the number of voltage loops in a linear manner with an adjusted goodness of fit, R2 = 0.998, 0.981, and 0.937, respectively (the linear fit data are shown in Figs. S12–S14 in the supplementary material). As the bacteria flow into the microchannel in a randomly distributed manner, the linear relationship suggests that the number of bacteria trapped and detected also scales linearly with the change in the system absolute impedance, in line with our model prediction as shown in Eq. (4). For example, in the Bacteria detection section, we determined that ∼69 E. coli cells were trapped after one voltage loop, and the average Δ(1/|Ztot|) per loop for our E. coli experiment was 26.9 nS, thus yielding KE.coli = 2.57 × 109 bacteria Ω. Similarly, the constant K for V. cholerae and Enterococcus are KV.cholera = 1.95 × 108 bacteria Ω and KEnterococcus = 2.74 × 109 bacteria Ω, respectively. Thus, instead of a “YES/NO” detection, the absolute number of bacteria can be estimated from the measured Δ(1/|Ztot|) and the respective K constant.

FIG. 5.

Variation of the Δ(1/|Ztot|) with the number of loops of 200 s “ON” and 10 min “OFF” DEP AC voltage cycle for (a) E. coli, (b) V. Cholerae, and (c) Enterococcus. The data points were computed from the average overall system absolute impedance and standard deviation for each of the five loops from Figs. 4(d), 4(f), and 4(h). The system conductance increases in a linear manner with an adjusted goodness of fit R2 of 0.998, 0.981, and 0.937, respectively.

Application for ballast water bacteria compliance test

According to the BWM D-2 regulation, the total allowable density of E. coli bacteria is less than 2.5 CFU ml−1. Therefore, in order to achieve rapid detection in 10 min, a minimum ballast water sample of 400 ml is required for the ballast water E. coli bacteria compliance test. First, the ballast water sample should be filtered with a 5 μm membrane filter and concentrated through centrifugation. Following centrifugation at 6000g for 3 min, the supernatant should be removed and washed three to five times with DI-water. This is to ensure that the conductive sea salt contents are eliminated. Subsequently, the washed sample is to be resuspended in 100 μl of DI-water and infused into the device for detection through a syringe and microbore tubing for impedance measurement and detection. Similarly, for V. cholerae and Enterococcus, the minimum ballast water sample volumes are 10 l and 1 l, respectively.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, a dielectrophoretic impedance measurement (DEPIM) lab-on-chip device for bacteria trapping and detection of Escherichia coli, Vibrio cholerae, and Enterococcus is developed. Through the integration of SU-8 negative photoresist as a microchannel, which allows for the precise alignment of the SU-8 microchannel with the on-chip gold interdigitated microelectrodes, we achieved a high bacteria trapping efficiency of up to 97.4% and 97.7% for E. coli and V. cholerae. As a result, our device has a high detection sensitivity of 69 ± 33 E. coli bacteria and 9 ± 2 V. cholerae bacteria to observe a discernible change in system impedance for detection in 10 min. On the other hand, the trapping efficiency for Enterococcus was lower, ∼37.8%. Nonetheless, the device only requires 36 ± 13 Enterococcus bacteria for detection. Taking account of the 37.8% trapping efficiency, the corrected limit of detection for Enterococcus is 95 ± 34. Our device could potentially be used for ballast water bacteria detection, which offers high detection sensitivity and the ability to quantitatively estimate the actual bacterial concentration of E. coli, V. cholerae, and Enterococcus in ballast water.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

See the supplementary material for further information on ballast water management, device design and fabrication, antibody coating, prototype layout, bacteria culture and preparation, bacteria concentration counting, antibody specificity, impedance response for DI-water, and line fitting data.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge financial support provided by the Singapore Maritime Institute (SMI) under the Maritime Sustainability R&D Program (Research Grant No. SMI-2015-MA-10). They would like to thank Dr. Quang D. Tran and Dr. Phu N. Tran for the advice and fruitful discussion.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Seebens H., Gastner M. T., and Blasius B., Ecol. Lett. 16(6), 782–790 (2013). 10.1111/ele.12111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Maritime Organization, See http://www.imo.org/OurWork/Environment/BallastWaterManagement/Pages/Default.aspx for “Ballast Water Management” (last accessed 18 September 2020).

- 3.Endresen Ø., Lee Behrens H., Brynestad S., Bjørn Andersen A., and Skjong R., Mar. Pollut. Bull 48(7), 615–623 (2004). 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2004.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakalar G., SpringerPlus 3, 468 (2014). 10.1186/2193-1801-3-468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Maritime Safety Agency, See http://www.emsa.europa.eu/emsa-documents/latest/item/3472-ballast-water-management-guidance-for-best-practices-on-sampling.html for “Ballast Water Management—Guidance for Best Practices on Sampling” (last accessed 18 September 2020).

- 6.Vermicon A. G., See https://www.vermicon.com/products/scanvit-water/test-kit-quantitative-analysis-balast-water-enterococcus-ecoli/ for “Scan VIT Ballast Water Enterococcus/E. coli” (last accessed 18 September 2020).

- 7.Jayamohan H., Romanov V., Li H., Son J., Samuel R., Nelson J., Gale B. K., and Patrinos G. P., Molecular Diagnostics, 3rd ed. (Academic Press, 2017), pp. 197–217. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu J., Jasim I., Shen Z., Zhao L., Dweik M., Zhang S., and Almasri M., PLoS One 14(5), e0216873 (2019). 10.1371/journal.pone.0216873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luo T., Fan L., Zhu R., and Sun D., Micromachines 10(2), 104 (2019). 10.3390/mi10020104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang X., Jing W., Zheng L., Liu S., Wu W., and Sui G., Lab Chip 14(4), 671–676 (2014). 10.1039/C3LC50977J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suehiro J., Hamada R., Noutomi D., Shutou M., and Hara M., J. Electrostat. 57(2), 157–168 (2003). 10.1016/S0304-3886(02)00124-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suehiro J., Noutomi D., Shutou M., and Hara M., J. Electrostat. 58(3), 229–246 (2003). 10.1016/S0304-3886(03)00062-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Páez-Avilés C., Juanola-Feliu E., Punter-Villagrasa J., Del Moral Zamora B., Homs-Corbera A., Colomer-Farrarons J., Miribel-Català P. L., and Samitier J., Sensors 16(9), 1514 (2016). 10.3390/s16091514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sabounchi P., Morales A. M., Ponce P., Lee L. P., Simmons B. A., and Davalos R. V., Biomed. Microdevices 10(5), 661 (2008). 10.1007/s10544-008-9177-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamada R., Takayama H., Shonishi Y., Mao L., Nakano M., and Suehiro J., Sens. Actuators B Chem. 181, 439–445 (2013). 10.1016/j.snb.2013.02.030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim M., Jung T., Kim Y., Lee C., Woo K., Seol J. H., and Yang S., Biosens. Bioelectron. 74, 1011–1015 (2015). 10.1016/j.bios.2015.07.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.del Moral-Zamora B., Punter-Villagrassa J., Oliva-Brañas A. M., Álvarez-Azpeitia J. M., Colomer-Farrarons J., Samitier J., Homs-Corbera A., and Miribel-Català P. L., Electrophoresis 36(9–10), 1130–1141 (2015). 10.1002/elps.201400446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suehiro J., Hatano T., Shutou M., and Hara M., Sens. Actuators B Chem. 109(2), 209–215 (2005). 10.1016/j.snb.2004.12.048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandez R. E., Rohani A., Farmehini V., and Swami N. S., Anal. Chim. Acta 966, 11–33 (2017). 10.1016/j.aca.2017.02.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schröder U.-C., Ramoji A., Glaser U., Sachse S., Leiterer C., Csaki A., Hübner U., Fritzsche W., Pfister W., Bauer M., Popp J., and Neugebauer U., Anal. Chem. 85(22), 10717–10724 (2013). 10.1021/ac4021616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asami K., Hanai T., and Koizumi N., Biophys. J. 31(2), 215–228 (1980). 10.1016/S0006-3495(80)85052-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyu C., Wang J., Powell-Palm M., and Rubinsky B., Sci. Rep. 8(1), 2481 (2018). 10.1038/s41598-018-20535-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dastider S. G., Barizuddin S., Yuksek N. S., Dweik M., and Almasri M. F., J. Sens. 2015, 293461 (2015). 10.1155/2015/293461 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zou Z., Kai J., Rust M. J., Han J., and Ahn C. H., Sens. Actuators A Phys. 136(2), 518–526 (2007). 10.1016/j.sna.2006.12.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dastider S. G., Barizuddin S., Dweik M., and Almasri M., RSC Adv. 3(48), 26297–26306 (2013). 10.1039/c3ra44724c [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kong T. F., Shen X., Marcos, and C. Yang, Appl. Phys. Lett. 110(23), 233501 (2017). 10.1063/1.4984897 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

See the supplementary material for further information on ballast water management, device design and fabrication, antibody coating, prototype layout, bacteria culture and preparation, bacteria concentration counting, antibody specificity, impedance response for DI-water, and line fitting data.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.