Abstract

Sporothrix species are commonly isolated from environmental and clinical samples. As common causes of zoonotic mycosis, Sporothrix species may result in localized or disseminated infections, posing considerable threat to animal and human health. However, the pathogenic profiles of different Sporothrix species varied, in virulence, geographic location and host ranges, which have yet to be explored. Analysing the genomes of Sporothrix species are useful for understanding their pathogenicity. In this study, we analyzed the whole genome of 12 Sporothrix species and six S. globosa isolates from different clinical samples in China. By combining comparative analyses with Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), Carbohydrate-Active enZymes (CAZy), antiSMASH, Pfam, and PHI annotations, Sporothrix species showed exuberant primary and secondary metabolism processes. The genome sizes of four main clinical species, i.e., S. brasiliensis, S. schenckii, S. globosa, and S. luriei were significantly smaller than other environmental and clinical Sporothrix species. The contracted genes included mostly CAZymes and peptidases genes that were usually associated with the decay of plants, as well as the genes that were associated with the loss of pathogenicity and the reduced virulence. Our results could, to some extent, explain a habitat shift of Sporothrix species from a saprobic life in plant materials to a pathogenic life in mammals and the increased pathogenicity during the evolution. Gene clusters of melanin and clavaric acid were identified in this study, which improved our understanding on their pathogenicity and possible antitumor effects. Moreover, our analyses revealed no significant genomic variations among different clinical isolates of S. globosa from different regions in China.

Keywords: Sporothrix, comparative genomics, enzyme, gene clusters, phylogeny, fungal evolution

Introduction

Sporothrix species distribute all over the world, particularly in tropical and subtropical areas. Sporothrix includes about 51 species, commonly isolated from environmental and clinical samples (de Beer et al., 2016). Some Sporothrix species are associated with plants, decaying wood and organics in soil as environmental saprobes, while some are agents of Sporotrichosis on animals and humans (Rodrigues et al., 2016).

Sporothricosis is common in horticulturists, farmers and miners exposed to plants, soil or organic matter contaminated with Sporothrix pathogens, and is also seen in animals such as cats and dogs (Barros et al., 2011). The most common clinical lesion types are lymphocutaneous and fixed localized lesions (Verma et al., 2012). In addition, disseminated sporotrichosis might develop in immunocompromised patients (White et al., 2019).

Variations exist between different Sporothrix species including virulence, morbidity, host preference and drug resistance (Arrillaga-Moncrieff et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2015). The four main species well known as pathogenic to humans and animals are S. brasiliensis, S. schenckii, S. globosa, and S. luriei (Zhang et al., 2015). Among them, S. brasiliensis is the most virulent species, followed by S. schenckii, S. globosa, and S. luriei (Arrillaga-Moncrieff et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2015). Sporotrichosis caused by S. schenckii is prevalent globally (Chakrabarti et al., 2015), While S. globosa prevails in Asia, Europe and the Americas (Camacho et al., 2015). Recent evidences suggested that S. globosa is the major Chinese pathogenic species, with broad geographic distribution (Moussa et al., 2017; Nesseler et al., 2019; Song et al., 2013). S. brasiliensis is known to be always transmitted by cats and has outbroken in Brazil (Mora-Montes et al., 2015). S. luriei is a relatively rare pathogen compared with the other three species (Padhye et al., 1992; Marimon et al., 2008; Oliveira et al., 2011). Infections were also occasional reported from other species, i.e., S. mexicana (Dias et al., 2011) and S. pallida (Rodrigues et al., 2013). While S. humicola was known to be pathogenic to animals, as well as saprobic in the environment (Nesseler et al., 2019).

As far, previous multi-locus phylogenetic analyses have inferred that all clinical species have evolved from environmental species (Song et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2015). Several studies reported the whole-genome of few pathogenic species (D’Alessandro et al., 2016; de Beer et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2016; Shang et al., 2016), but the differences in genomes between environmental strains and clinical strains were never compared, posing difficulties in explaining the relationships between phenotypes and genotypes in the evolution of Sporothrix. To further understand the variations in the pathogenicities of Sporothrix, we analyzed and annotated the genomes and secondary metabolite biosynthesis of the four main clinical species, together with other rare pathogens and environmental species. Six clinical strains of S. globosa isolated from different regions in China were also compared and analyzed to understand their geographic variations.

Materials and Methods

Fungal Strains and DNA Extraction

Six Sporothrix strains isolated from the skin lesions of patients in China and 10 ex-type strains obtained from the CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre, including S. globosa, S. schenckii luriei, S. mexicana, S. pallida, S. brunneoviolacea, S. dimorphospora, S. humicola, S. inflata, S. lignivora, and S. variecibatus were included in the study (Table 1). Isolates were inoculated on 2% (0.02 g/ml) potato dextrose agar (PDA) and incubated for 7 days at 25°C prior to harvesting 100–200 milligrams of fungal mycelia. Genomic DNA was subsequently extracted using the cetyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) method (Liu et al., 2013).

TABLE 1.

Summary of isolates used in this study.

| Strain | Name | Source | Origin |

| LC 2460 | S. globosa | Clinical strain | Beijing, China |

| LC 2454 | S. globosa | Clinical strain | Beijing, China |

| LC 2445 | S. globosa | Clinical strain | Chongqing, China |

| LC 2433 | S. globosa | Clinical strain | Chongqing, China |

| LC 2405 | S. globosa | Clinical strain | Jilin, China |

| LC 2404 | S. globosa | Clinical strain | Jilin, China |

| CBS 120340 | S. globosa | Clinical strain | Spain |

| CBS 937.72 | S. luriei | Clinical strain | South Africa |

| CBS 131.56 | S. pallida | Stemonitis fusca | Japan |

| CBS 120341 | S. mexixcana | Soil | Mexico |

| CBS 118129 | S. humicola | Soil | South Africa |

| CBS 553.74 | S. dimorphospora | Soil | Canada |

| CBS 239.68 | S. inflata | Wheatfield soil | Germany |

| CBS 121961 | S. variecibatus | Protea infructescences | South Africa |

| CBS 124561 | S. brunneoviolacea | Soil | Spain |

| CBS 119148 | S. lignivora | Eucalyptus wood pole | South Africa |

Genome Sequencing and Assembly

The whole genomes of Sporothrix strains were sequenced using next generation Illumina Hiseq 2000 technology. Analysis based on K-mer using Jellyfish1 was undertaken to estimate the error rate of sequencing and the sizes of the genomes including heterozygosity and duplication. The sequence reads of Sporothrix genomes were assembled into contigs and scaffolds using SPAdes2. The effect of the contigs and scaffolds assembled was assessed with the default command of quast. Only scaffolds longer than 200 bp were considered for further analyses.

Ab initio Gene Prediction and Annotation

The genomes of S. schenckii (AWEQ00000000.1, strain ATCC 58251) (Lombard et al., 2014) and S. brasiliensis (AWTV00000000.1, strain 5110) (de Beer et al., 2016) were downloaded from the GenBank, and were analyzed together with our strains. Gene predictions were performed using GeneMark-ES (Borodovsky and Lomsadze, 2011) in unsupervised ab initio mode. Automatic annotations were performed using Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)3, Pfam (downloaded in June 2019) and PHI (version 4.8) databases (Han et al., 2016; Song et al., 2020) to analyze both homology and specific proteins. All results of Pfam and PHI databases were obtained using locally compiled databases. KEGG Pathways were inspected manually to analyze the metabolic pathways. The assembled scaffolds of the Sporothrix genomes were supplied to antiSMASH4 to evaluate the secondary metabolites (Blin et al., 2019). Gene clusters involved in pathogenicity, virulence and other areas of interest were further examined according to the domain annotations. BLASTp was adopted to search against the Gene Ontology (GO) database (by August 2019). Annotation of carbohydrate-active enzymes was performed with the translated protein sequences using the Carbohydrate-Active enZymes (CAZy) database5 (Lombard et al., 2014).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using STATA version 14.2 (Stata Corporation, College Station, United States). Normal distributed data were analyzed using t-test, while non-normal distributed data were analyzed using the Wilcoxon sign rank test. A p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the Sporothrix Genomes

The genome assembly of 16 Sporothrix strains ranged from approximately 33–44 Mb and included 138–5460 scaffolds with N50 length ranging from 1.8 to 10.7 Mb. The k-mer frequency distribution showed a unique peak suggesting that the sequenced fungal genomes did not exhibit significant heterozygosity. The number of predicted proteins ranged from 9010 to 13344. Genomes assemblies of the 16 Sporothrix strains were deposited in the GenBank. In this study, genome statistics including accession numbers, genome size, predicted proteins, assembled contigs and scaffolds were shown in Table 2. The genome size was largest in S. lignivora, followed by S. mexixcana, S. humicola, S. pallida, S. inflata, S. dimorphospora, S. variecibatus, S. brunneoviolacea, S. luriei, S. globosa, S. brasiliensis, and S. schenckii. There was no significant difference in genomes of Chinese S. globosa isolates, as well as with the ex-type strain.

TABLE 2.

Genome statistics of Sporothrix.

| Strain | Name | GenBank accession number | Genome size (Mb) | G + C content (%) | N50 length (Mb) | Predicted proteins | Assembled contigs | Assembled scaffolds | References |

| 5110 | S. brasiliensis | AWTV00000000.1 | 33.21 | 54.7 | 3.8 | 9091 | 601 | – | de Beer et al., 2016 |

| ATCC 58251 | S. schenckii | AWEQ00000000.1 | 32.23 | 55.1 | 3.3 | 8674 | 125 | 29 | Lombard et al., 2014 |

| CBS 120340 | S. globosa | WOEH00000000 | 33.29 | 54.51 | 2.9 | 9009 | 779 | 312 | – |

| LC 2460 | S. globosa | WNYM00000000 | 33.36 | 54.47 | 3.6 | 9036 | 837 | 276 | – |

| LC 2454 | S. globosa | WNYL00000000 | 33.36 | 54.46 | 3.1 | 9039 | 761 | 277 | – |

| LC 2445 | S. globosa | WNYK00000000 | 33.35 | 54.47 | 3 | 9128 | 817 | 308 | – |

| LC 2433 | S. globosa | WNYJ00000000 | 33.39 | 54.51 | 2.7 | 9098 | 819 | 371 | – |

| LC 2405 | S. globosa | WMHP00000000 | 33.44 | 54.42 | 2.3 | 9218 | 753 | 414 | – |

| LC 2404 | S. globosa | WNYB00000000 | 33.43 | 54.47 | 5 | 9010 | 2016 | 241 | – |

| CBS 937.72 | S. luriei | WNLO00000000 | 34.24 | 55.75 | 1.8 | 10,105 | 16,679 | 2213 | – |

| CBS 120341 | S. mexixcana | WNYC00000000 | 43.74 | 52.79 | 4.5 | 11,997 | 40,495 | 5460 | – |

| CBS 131.56 | S. pallida | WNYG00000000 | 40.23 | 52.76 | 4.8 | 10,749 | 1451 | 342 | – |

| CBS 118129 | S. humicola | WNYE00000000 | 40.74 | 52.21 | 3.6 | 10,656 | 2120 | 447 | – |

| CBS 553.74 | S. dimorphospora | WOUA00000000 | 39.13 | 55.17 | 5.6 | 10,706 | 10,821 | 598 | – |

| CBS 239.68 | S. inflata | WNYF00000000 | 39.53 | 55.47 | 3 | 11,008 | 1787 | 347 | – |

| CBS 121961 | S. variecibatus | WNYH00000000 | 38.87 | 52.94 | 10.7 | 10,411 | 738 | 138 | – |

| CBS 124561 | S. brunneoviolacea | WNYD00000000 | 37.75 | 56.41 | 1.9 | 11,160 | 8508 | 825 | – |

| CBS 119148 | S. lignivora | WNYI00000000 | 43.98 | 51.2 | 8.3 | 13,344 | 12,426 | 1438 | – |

Gene Expansion and Contraction in the Sporothrix Species

Evolutions of Sporothrix in gene families were inferred based on domain expansions or contractions assigned by the antiSMASH, CAZy, KEGG, Pfam, and PHI databases.

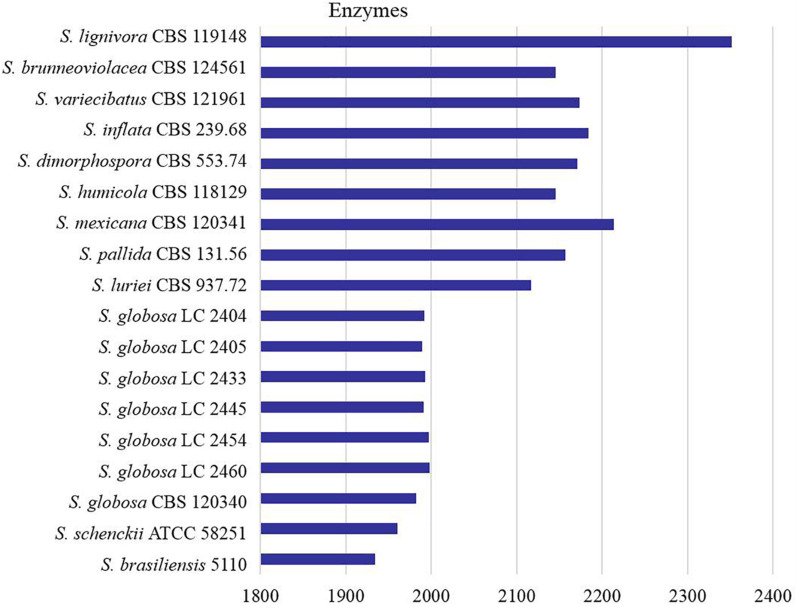

All proteins annotated with known function were classified into different categories according to the KEGG database (Figure 1). We found that core metabolic functions comprised enzymes, exosome, membrane trafficking, messenger RNA biogenesis, mitochondrial biogenesis, ribosome, and spliceosome. Enzymes metabolism was significantly predominant in contrast to other classifications. The enzyme genes of four main clinical species (S. brasiliensis, S. schenckii, S. globosa, and S. luriei) were less than most of environmental and other clinical species (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

Protein annotation of KEGG database in Sporothrix. All proteins annotated with known function were classified into different categories according to the KEGG database. The core metabolic functions comprised enzymes, exosome, membrane trafficking, messenger RNA biogenesis, mitochondrial biogenesis, ribosome, and spliceosome.

FIGURE 2.

Counts of the enzymes encoded by genes in Sporothrix. Enzyme genes of four main clinical species (S. brasiliensis, S. schenckii, S. globosa and S. luriei) were less than most of environmental and other clinical species.

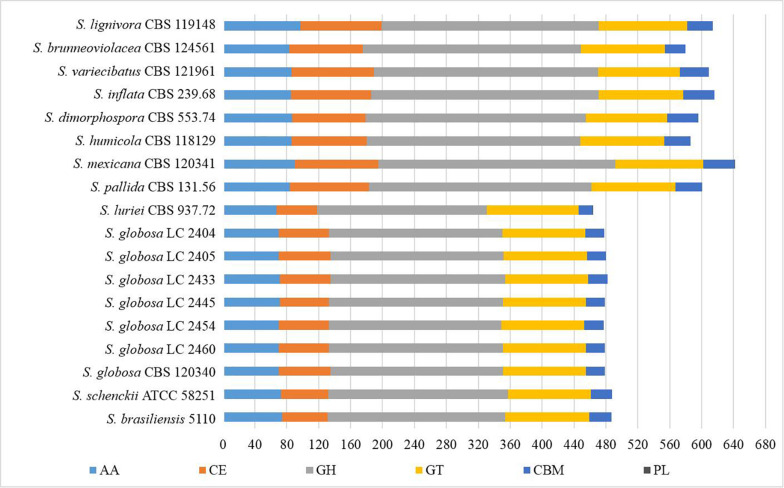

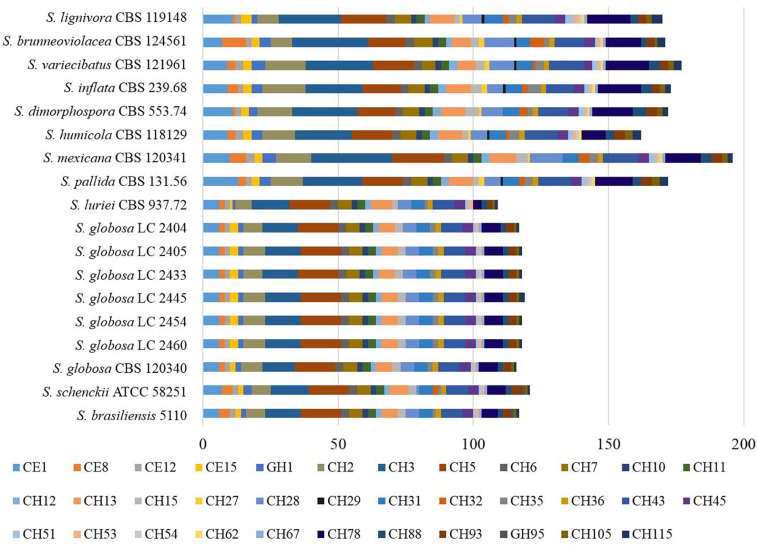

We explored the Sporothrix genomes for genes encoding carbohydrate-active enzymes and carbohydrate-binding modules. CAZy-coding genes falling into 141 families and CBM-coding genes in 19 families were identified. These genes were categorized into the auxiliary activities (AA), glycoside hydrolases (GH), glycosyltransferases (GT), carbohydrate-binding modules (CBM), carbohydrate esterases (CE), and polysaccharide lyases (PL) families. We observed that the highest proportion of gene sequences were assigned to the GH family, while there were a lack of polysaccharide lyase genes in almost all Sporothrix strains. A few gene sequences related to subfamilies PL1 and PL27 were detected only in S. luriei and S. mexicana. Further analysis was carried out to determine the gene distribution in the respective classifications. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test based on the gene counts in these families showed that there were significant differences (p < 0.05) in the distribution of the enzyme genes between the four main clinical species and other Sporothrix species. The heatmap and chart based on family classification suggested that the enzyme genes of the four main clinical species were significantly less than those of the other Sporothrix species, especially the genes belonging to the GH and CE groups (Figures 3, 4).

FIGURE 3.

Gene contraction of carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) in the genus Sporothrix. Genes of Sporothrix identified through CAZy database were classified into 6 categories. CAZymes genes of the four main clinical species (S. brasiliensis, S. schenckii, S. globosa, and S. luriei) were significantly less than those of the other Sporothrix species, especially the genes belonging to the GH and CE groups.

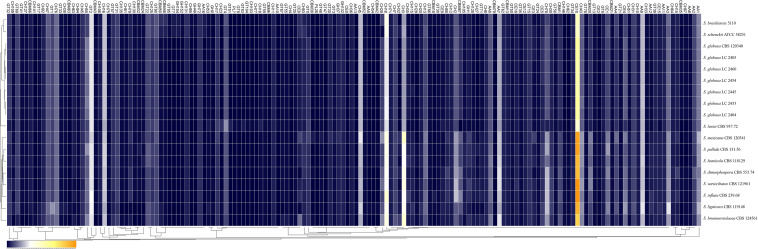

FIGURE 4.

Comparison of the CAZymes identified in the genomes of the genus Sporothrix. CAZy-coding genes falling into 141 families and CBM-coding genes in 19 families were identified in the genomes of the genus Sporothrix. There was a higher abundance of PPD enzyme genes, especially GH1, GH2, GH3, GH28, GH43, GH78, and CE1 in two clinical species (S. mexicana and S. pallida) and environmental species. A remarkable gene contraction was observed in the four main clinical species (S. brasiliensis, S. schenckii, S. globosa, and S. luriei) including AA3, AA7, CBM20, and CE10 families. Genes of CBM48 and CBM50 expanded in S. brasiliensis and S. schenckii.

Most CAZy enzyme genes were predicted using comprehensive annotation and comparison analysis in the CAZy database. The major plant polysaccharide degradation (PPD) enzyme genes in the four main clinical species were less than those of the environmental and other clinical species in further analyses (Figure 5). There was a higher abundance of PPD enzyme families, especially GH1, GH2, GH3, GH28, GH43, GH78, and CE1 in two clinical species (S. mexicana and S. pallida) and environmental species (Figures 4, 5). In addition, a remarkable contraction was observed in the four main clinical species including AA3 and AA7 families supporting the lignocellulose degradation, CBM20 carbohydrate-binding modules enhancing the activity of granular starch-binding function, and CE10 families assisting great capacity to digest pectin (Figures 4, 5). Though most CAZymes genes were in contraction, the comparative analysis revealed genes of CBM48 and CBM50 expanded in the two most virulent species, S. brasiliensis and S. schenckii (Figures 4, 5).

FIGURE 5.

Counts of the putative genes involved in plant polysaccharide degradation in the genus Sporothrix. The major plant polysaccharide degradation (PPD) enzyme genes in the four main clinical species (S. brasiliensis, S. schenckii, S. globosa, and S. luriei) were less than those of the environmental and other clinical species.

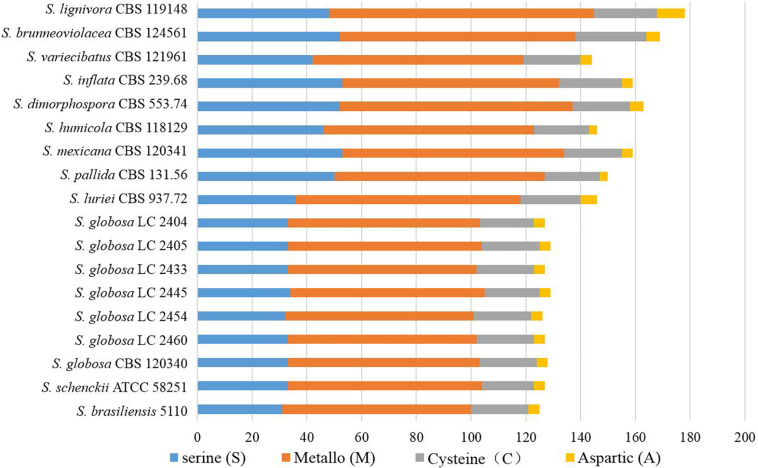

There were 125–178 protease-coding genes identified through Pfam database, which were classified into 4 categories consisting of 48 subfamilies (Figures 6, 7). In general, the largest category of predicted proteases in the Sporothrix genome was Metallo (M), followed by Serine (S), Cysteine (C), and Aspartic (A) proteases (Figure 6). No enrichment of peptidase genes in the clinical species was observed. The four main clinical species had less M20, S8, S9, and S15 subfamily genes than other species (Figure 7).

FIGURE 6.

Gene contraction of peptidases in the genus Sporothrix. Protease-coding genes of Sporothrix identified through Pfam database were classified into 4 categories. The largest category of predicted proteases in the Sporothrix genome was Metallo (M), followed by Serine (S), Cysteine (C), and Aspartic (A) proteases.

FIGURE 7.

Heatmap of the peptidases identified in the genomes of the genus Sporothrix. Protease-coding genes of Sporothrix identified through Pfam database were classified into 48 subfamilies. The four main clinical species (S. brasiliensis, S. schenckii, S. globosa, and S. luriei) had less M20, S8, S9, and S15 subfamily genes than other species.

Genes associated with virulence of 16 Sporothrix strains ranged from 3083 to 4750. The highest number was found in S. lignivora (CBS 119148), and the lowest in S. brasiliensis (5110) (Figure 8). Genes associated with the reduced virulence, and unaffected pathogenicity were consistently present with higher copy numbers in all strains. From the virulence gene prediction, genes of five classifications, i.e., loss of pathogenicity, reduced virulence, unaffected pathogenicity, increased pathogenicity, and lethal factors in four main clinical species were less than those in the environmental and other clinical species (p = 0.000000040, Wilcoxon sign rank test), and the reduced number of genes associated with the loss of pathogenicity, reduced virulence and unaffected pathogenicity was far more than that associated with the increased pathogenicity and lethal factors. Virulence gene families assigned by Pfam in this study were summarized into the following five classifications, i.e., cyclase-associated protein (CAP), Coenzyme A (CoA), heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70), ubiquitin family, and superoxide dismutases (SOD). However, significant difference in the five classifications of virulence genes was not observed in the different Sporothrix species (Figure 9). Genes associated with effector, enhanced antagonism, resistance to chemical medicine and sensitivity to chemical medicine present lower copy numbers, with no significant difference among different Sporothrix species (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8.

Genes associated with virulence in the genus Sporothrix. From the virulence gene prediction, genes of five classifications, i.e., loss of pathogenicity, reduced virulence, unaffected pathogenicity, increased pathogenicity, and lethal factors in four main clinical species (S. brasiliensis, S. schenckii, S. globosa, and S. luriei) were less than those in the environmental and other clinical species, and the reduced number of genes associated with the loss of pathogenicity, reduced virulence and unaffected pathogenicity was far more than that associated with the increased pathogenicity and lethal factors.

FIGURE 9.

Virulence genes annotated with Pfam in the genus Sporothrix. Virulence gene families assigned by Pfam were summarized into cyclase-associated protein (CAP), Coenzyme A (CoA), heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70), ubiquitin family, and superoxide dismutases (SOD). Significant difference in the five classifications of virulence genes was not observed in different Sporothrix species.

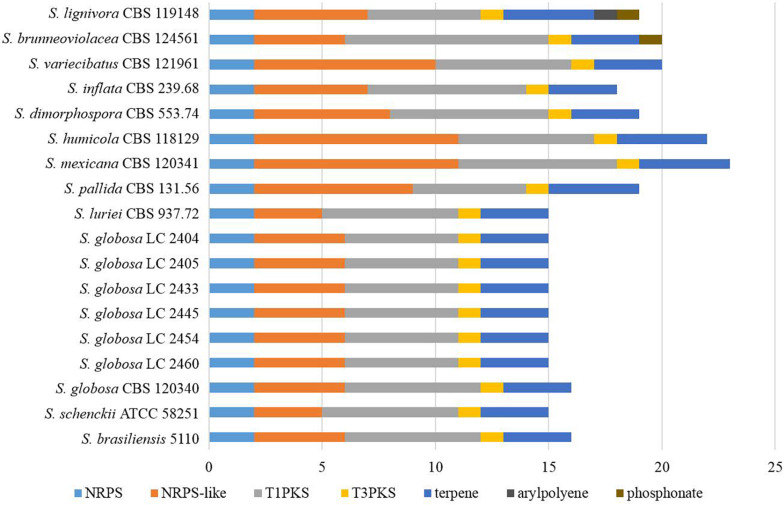

Bioactive Secondary Metabolites

Fifteen to 23 putative secondary biosynthetic gene clusters were identified though the antiSMASH platform. There were 15–16 gene clusters in the four main clinical species, while 17–23 gene clusters in other species. Many of these putative gene clusters belonged to type I pks (tIpks), non-ribosomal peptide synthase (nrps) gene clusters, and terpene, while the rest were type III pks (tIIIpks), indole, aryl polyene, or phosphonate. The gene clusters of tIpks and nrps were less in the four main clinical species. The number of tIIIpks genes was the same in all Sporothrix species (Figure 10).

FIGURE 10.

The putative secondary biosynthetic gene clusters identified in the genomes of Sporothrix species. Secondary biosynthetic gene clusters of Sporothrix were identified though antiSMASH platform. These putative gene clusters belonged to tIpks, nrps, terpene, tIIIpks, indole, arylpolyene, and phosphonate. Gene clusters of tIpks and nrps were less in the four main clinical species (S. brasiliensis, S. schenckii, S. globosa, and S. luriei) than those of the environmental and other clinical species.

All sequenced Sporothrix strains had tIpks gene clusters encoding melanin, and terpene gene clusters encoding clavaric acid. Based on the BLASTp and domain analyses, we identified 58.3% strains with emericellin genes in the nrps gene clusters and 41.7% strains with non-acetylated open-chain sophorolipid genes in the tIpks gene clusters. We detected that 75% strains have tIpks genes with 33.3% sequence identity with fujikurins. In addition, several predicted gene clusters of two clinical species (S. mexicana and S. pallida) and environmental species might encode HC-toxin, phenalamide, lydicamycin, TAN-1612, trypacidin, aspercryptins, usnic acid, botryenalol, melithiazol, leporin, dehydrocurvularin, sorbicillin, elsinochrome A, equisetin, clapurines, and natamycin.

The ex-type strain of S. globosa was compared with the clinical strains from three regions in China (Beijing, Chongqing, Jilin). Though the incidence of sporotrichosis and the growth rate of colony in three regions were different, there was no significant difference in CAZyme-coding genes (Figures 3–5), protease-coding genes (Figures 6, 7), virulence related genes (Figures 8, 9) and putative secondary biosynthetic gene clusters (Figure 10) between the ex-type strain and Chinese clinical strains.

Discussion

Sporothrix species infect humans and animals, and are widely distributed in the environments. The recent outbreaks in Australia, Brazil, China, India and South Africa have raised serious concerns on public health. Sporothrix is one of the major causes of deep fungal infection, with increasing resistance to antifungal medicines (Li J. et al., 2019). Sporothrix species have shown considerable variations in virulence, host preference and drug resistance, and the study on the relationships between phenotypes and genotypes of Sporothrix is crucial for understanding their pathogenesis.

Differences in pathogenic phenotypes of Sporothrix species could be correlated to the expansion or contraction in specific gene families. Previous multi-locus phylogenetic studies could not explain these phenotypic variations. Next-generation sequencing enables a comprehensive profiling of genetic data which enables a better interpretation and correlation of the phenotypic characters with their genetic bases. Previous studies speculated that the clinical species evolved from environmental species (Zhou et al., 2014), and the four main clinical species (S. brasiliensis, S. schenckii, S. globosa, and S. luriei) proved to show high degrees of endemicity (Zhang et al., 2015). In this study, the four main clinical species have smaller genome sizes and the number of predicted proteins are also obviously less, as compared to the environmental species (S. brunneoviolacea, S. dimorphospora, S. humicola, S. inflata, S. lignivora, and S. variecibatus) and other clinical pathogens (S. mexicana and S. pallida). Therefore, we infer that genes lost in the evolution of Sporothrix. Gene loss is a pervasive route of genetic contraction. On the other hand, gene gain is usually a main driver of genetic expansion (Zhi et al., 2017). Gene loss or gain as a source of functional variations plays a prominent role in microbial evolutions (Bush et al., 2017). We consider that the gene contraction, i.e., the abandonment of genes is more important, as compared to the gene expansion in the evolution of Sporothrix.

The number of enzyme genes significantly differ in Sporothrix species. CAZymes are important in the degradation of carbohydrate in the hosts. PPD enzymes of CAZymes provide carbon sources by degrading plant polysaccharides in cytoderm (Courtade and Aachmann, 2019; Pan et al., 2019). Poverty in CAZymes genes related to degrading cellulose, xyloglucan, galactomannan, and pectin, is not surprising in the four main clinical Sporothrix species, as humans and animals lack cytoderm. The obvious contraction of these enzyme genes in the four main clinical species are suggestive of reduced plant invasive capabilities. On the other hand, a clear expansion of enzyme genes in CBM48 and CBM50 domains is observed in two most virulent pathogens S. brasiliensis and S. schenckii. CBM48, similar to CBM20, is mostly involved in starch biosynthesis (Wilkens et al., 2018). CBM50, also known as LysM domains, plays an important role in inhibiting host defenses (Volk et al., 2019). Peptidases provide alternative carbon sources for glucose starving cells through degrading proteins (Handtke et al., 2018), and promote various progresses, such as cell growth and differentiation, apoptosis, cell cycle, and signaling (Ng et al., 2009). Mutant in peptidase gene has been known as an important drive for fungal adaptation to hosts and environment (Soberanes-Gutierrez et al., 2015; Cervantes-Montelongo and Ruiz-Herrera, 2019). Interestingly, none of the genes related to Asparagine, Glutamate, and Threonine were previously predicted. Moreover, we have not observed the enrichment of peptidase genes in clinical Sporothrix, specifically M35 and M36 subfamilies, which usually expand in dimorphic fungal pathogens as an adaptation to mammalian hosts (Sharpton et al., 2009). This result is consistent with that of Teixeira (Teixeira et al., 2014). In contrast, we observed less M20, S8, S9, and S15 subfamily genes in these strains. A previous study showed that clinical fungi tended to have less prolyl oligopeptidases (S9), and subtilisins (S8) that might be associated with a saprotrophic lifestyle (Muszewska et al., 2017). The occurrence of genes contraction in CAZymes and peptidases suggested a shift to pathogenic lifestyle in the evolution of Sporothrix. This study is the first time finding the decrease of M20 and S15 subfamily genes in clinical fungi and their potential roles in the evolution of Sporothrix. The above findings suggest that Sporothrix may have abandoned some useless genes but enriched virulence genes in the evolution.

Genes associated with virulence play important roles in the pathogenicity of fungi. However, the mechanism of variant virulence in Sporothrix species remains unknown. In our study, the reduced number of genes associated with the loss of pathogenicity, reduced virulence and unaffected pathogenicity is remarkable in the four main clinical Sporothrix species, and it is far more than that associated with the increased pathogenicity and lethal. This finding sheds light to unveil the increased pathogenicity of Sporothrix species during their evolution. Furthermore, some proteins encoded by virulence genes have known roles in extracellular vesicle production, dimorphic transition, subversion of host innate immunity, and invasiveness (Rossato et al., 2018; Song et al., 2020). For example, The Cap protein plays an important role in regulating cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) signaling (Yang et al., 2019). Acyl-CoA functioned in leucine catabolism is required for the vegetative growth, conidiation and full virulence (Li Y. et al., 2019). Hsp70 functioned as a stress-related transcriptional co-activator is required for fungal virulence (Weissman et al., 2020). Deletion of ubiquitin genes results in abnormal morphology, reduced sporulation, and attenuation of virulence (Oh et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2018). SOD contributes to the growth and survival under conditions of oxidative stress (Poli et al., 2004), and the antioxidant function of Cu SOD has been reported to be critical for the pathogenesis of fungi (Narasipura et al., 2003).

The large number of secondary biosynthetic gene clusters in Sporothrix suggests their biosynthetic potentials. Further research should provide guidance for the control of harmful secondary metabolites and the develop of beneficial secondary metabolites. Melanin is one of the harmful secondary metabolites prevalent in fungal pathogens, the expression of which is implicated in the pathogenesis (Langfelder et al., 2003). Specifically, melanin is resistant to phagocytosis, free radicals, antifungal drugs, and the host immune system (Al-Laaeiby et al., 2016). Melanin in Sporothrix was confirmed by observation in vitro and immunofluorescence with murine monoclonal antibodies (Morris-Jones et al., 2003; Godio and Martin, 2009). In this study, we predict that tIpks gene cluster is responsible for the biosynthesis of melanin in all Sporothrix species. Though contraction of gene clusters appears to be the trend in the evolution of Sporothrix, gene cluster associated with melanin is retained. This result contributes to understanding the pathogenic potential of Sporothrix. The gene cluster responsible for clavaric acid is also predicted in all Sporothrix species. Clavaric acid is a triterpenoid known for its antitumor activity, which is an inhibitor of the human Ras-farnesyl transferase (Li et al., 2018). Future studies on the biosynthesis of clavaric acid in Sporothrix by gene manipulation may be useful for the development of antitumor medicine.

Conclusion

The genomic analyses of the environmental and clinical Sporothrix strains might serve as a basis for the understanding their pathogenicity and evolution. Our results suggested that gene contraction was significant in the evolution of pathogenicity. The reduced CAZyme and peptidase genes were usually associated with the decay of plant invasive capabilities in the four main clinical Sporothrix species. This study explained a habitat shift in Sporothrix species from a saprobic lifestyle in the environment to a parasitic lifestyle in mammals. Furthermore, our analyses showed that the Sporothrix species, during their evolution, increased the virulence through reducing genes that were associated with the loss of pathogenicity and the reduced virulence. With respect to the secondary metabolites, we identified two important gene clusters of secondary metabolites, melanin and clavaric acid. We did not find any significant difference in genomes of S. globosa stains collected from different regions of China, indicating that regional differences did not lead to significant genetic variations in S. globosa. Interactions between microorganism and environment/host might have imposed a strong selection to genomic variations, which drove the evolution of Sporothrix species.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/ Supplementary Material.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Committee of Human Rights Related to Research Involving Human Subjects, Chongqing Hospital of Chinese Traditional Medicine. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

MH and XZ conceived the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. MH and ZM performed the genome sequencing, genome assembly, gene prediction, and gene annotation. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. L. Cai in the State Key Laboratory of Mycology, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for his valuable comments on this manuscript. We also thank CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Center for the provision of isolates.

Funding. This research was funded by the Chongqing Research Program of Basic Research and Frontier Technology (No. cstc2019jcyj-msxmX0013).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.565439/full#supplementary-material

References

- Al-Laaeiby A., Kershaw M. J., Penn T. J., Thornton C. R. (2016). Targeted disruption of melanin biosynthesis genes in the human pathogenic fungus Lomentospora prolificans and its consequences for pathogen survival. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17:444. 10.3390/ijms17040444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrillaga-Moncrieff I., Capilla J., Mayayo E., Marimon R., Marine M., Gene J., et al. (2009). Different virulence levels of the species of Sporothrix in a murine model. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 15 651–655. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02824.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros M. B., de Almeida Paes R., Schubach A. O. (2011). Sporothrix schenckii and Sporotrichosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 24 633–654. 10.1128/CMR.00007-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blin K., Shaw S., Steinke K., Villebro R., Ziemert N., Lee S. Y., et al. (2019). antiSMASH 5.0: updates to the secondary metabolite genome mining pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res. 47 W81–W87. 10.1093/nar/gkz310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borodovsky M., Lomsadze A. (2011). Eukaryotic gene prediction using GeneMark.hmm-E and GeneMark-ES. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics 4 4.6.1–4.6.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush S. J., Chen L., Tovar-Corona J. M., Urrutia A. O. (2017). Alternative splicing and the evolution of phenotypic novelty. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 372:20150474. 10.1098/rstb.2015.0474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camacho E., Leon-Navarro I., Rodriguez-Brito S., Mendoza M., Nino-Vega G. A. (2015). Molecular epidemiology of human sporotrichosis in Venezuela reveals high frequency of Sporothrix globosa. BMC Infect. Dis. 15:94. 10.1186/s12879-015-0839-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes-Montelongo J. A., Ruiz-Herrera J. (2019). Identification of a novel member of the pH responsive pathway Pal/Rim in Ustilago maydis. J. Basic Microbiol. 59 14–23. 10.1002/jobm.201800180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti A., Bonifaz A., Gutierrez-Galhardo M. C., Mochizuki T., Li S. (2015). Global epidemiology of sporotrichosis. Med. Mycol. 53 3–14. 10.1093/mmy/myu062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q., Li Y., Wang J., Li R., Chen B. (2018). cpubi4 is essential for development and virulence in chestnut blight fungus. Front. Microbiol. 9:1286. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtade G., Aachmann F. L. (2019). Chitin-active lytic polysaccharide monooxygenases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1142 115–129. 10.1007/978-981-13-7318-3_6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro E., Giosa D., Huang L., Zhang J., Gao W., Brankovics B., et al. (2016). Draft genome sequence of the dimorphic fungus Sporothrix pallida, a nonpathogenic species belonging to Sporothrix, a genus containing agents of human and feline sporotrichosis. Genome Announc. 4:e00184-16. 10.1128/genomeA.00184-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Beer Z. W., Duong T. A., Wingfield M. J. (2016). The divorce of Sporothrix and Ophiostoma: solution to a problematic relationship. Stud. Mycol. 83 165–191. 10.1016/j.simyco.2016.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias N. M., Oliveira M. M., Santos C., Zancope-Oliveira R. M., Lima N. (2011). Sporotrichosis caused by Sporothrix Mexicana, Portugal. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17 1975–1976. 10.3201/eid1710.110737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godio R. P., Martin J. F. (2009). Modified oxidosqualene cyclases in the formation of bioactive secondary metabolites: biosynthesis of the antitumor clavaric acid. Fungal Genet. Biol. 46 232–242. 10.1016/j.fgb.2008.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X., Chakrabortti A., Zhu J., Liang Z. X., Li J. (2016). Sequencing and functional annotation of the whole genome of the filamentous fungus Aspergillus westerdijkiae. BMC Genomics 17:633. 10.1186/s12864-016-2974-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handtke S., Albrecht D., Otto A., Becher D., Hecker M., Voigt B. (2018). The proteomic response of Bacillus pumilus cells to glucose starvation. Proteomics 18:1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L. L., Gao W. C., Giosa D., Criseo G., Zhang J., He T. L., et al. (2016). Whole-genome sequencing and in silico analysis of two strains of Sporothrix globosa. Genome Biol. Evol. 8 3292–3296. 10.1093/gbe/evw230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langfelder K., Streibel M., Jahn B., Haase G., Brakhage A. A. (2003). Biosynthesis of fungal melanins and their importance for human pathogenic fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 38 143–158. 10.1016/S1087-1845(02)00526-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Zhu M., An L., Chen F., Zhang X. (2019). Fungicidal efficacy of photodynamic therapy using methylene blue against Sporothrix globosa in vitro and in vivo. Eur. J. Dermatol. 29 160–166. 10.1684/ejd.2019.3527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Balmain A., Counter C. M. (2018). A model for RAS mutation patterns in cancers: finding the sweet spot. Nat. Rev. Cancer 18 767–777. 10.1038/s41568-018-0076-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zheng X., Zhu M., Chen M., Zhang S., He F., et al. (2019). MoIVD-mediated leucine catabolism is required for vegetative growth, conidiation and full virulence of the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. Front. Microbiol. 10:444. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Zhang Z., Hou B., Wang D., Sun T., Li F., et al. (2013). Rapid identification of Sporothrix schenckii in biopsy tissue by PCR. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 27 1491–1497. 10.1111/jdv.12030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombard V., Golaconda Ramulu H., Drula E., Coutinho P. M., Henrissat B. (2014). The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 42 D490–D495. 10.1093/nar/gkt1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marimon R., Gene J., Cano J., Guarro J. (2008). Sporothrix luriei: a rare fungus from clinical origin. Med. Mycol. 46 621–625. 10.1080/13693780801992837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mora-Montes H. M., Dantas Ada S., Trujillo-Esquivel E., de Souza Baptista A. R., Lopes-Bezerra L. M. (2015). Current progress in the biology of members of the Sporothrix schenckii complex following the genomic era. FEMS Yeast Res. 15:fov065. 10.1093/femsyr/fov065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris-Jones R., Youngchim S., Gomez B. L., Aisen P., Hay R. J., Nosanchuk J. D., et al. (2003). Synthesis of melanin-like pigments by Sporothrix schenckii in vitro and during mammalian infection. Infect. Immun. 71 4026–4033. 10.1128/iai.71.7.4026-4033.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussa T. A. A., Kadasa N. M. S., Al Zahrani H. S., Ahmed S. A., Feng P., Gerrits van den Ende A. H. G., et al. (2017). Origin and distribution of Sporothrix globosa causing sapronoses in Asia. J. Med. Microbiol. 66 560–569. 10.1099/jmm.0.000451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muszewska A., Stepniewska-Dziubinska M. M., Steczkiewicz K., Pawlowska J., Dziedzic A., Ginalski K. (2017). Fungal lifestyle reflected in serine protease repertoire. Sci. Rep. 7:9147. 10.1038/s41598-017-09644-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narasipura S. D., Ault J. G., Behr M. J., Chaturvedi V., Chaturvedi S. (2003). Characterization of Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD1) gene knock-out mutant of Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii: role in biology and virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 47 1681–1694. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03393.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesseler A., Schauerte N., Geiger C., Kaerger K., Walther G., Kurzai O., et al. (2019). Sporothrix humicola (Ascomycota: Ophiostomatales) - A soil-borne fungus with pathogenic potential in the eastern quoll (Dasyurus viverrinus). Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 25 39–44. 10.1016/j.mmcr.2019.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng N. M., Pike R. N., Boyd S. E. (2009). Subsite cooperativity in protease specificity. Biol. Chem. 390 401–407. 10.1515/BC.2009.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh Y., Franck W. L., Han S. O., Shows A., Gokce E., Muddiman D. C., et al. (2012). Polyubiquitin is required for growth, development and pathogenicity in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae. PLoS One 7:e42868. 10.1371/journal.pone.0042868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira D. C., Lopes P. G., Spader T. B., Mahl C. D., Tronco-Alves G. R., Lara V. M., et al. (2011). Antifungal susceptibilities of Sporothrix albicans, S. brasiliensis, and S. luriei of the S. schenckii complex identified in Brazil. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49 3047–3049. 10.1128/JCM.00255-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padhye A. A., Kaufman L., Durry E., Banerjee C. K., Jindal S. K., Talwar P., et al. (1992). Fatal pulmonary sporotrichosis caused by Sporothrix schenckii var. luriei in India. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30 2492–2494. 10.1128/jcm.30.9.2492-2494.1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y. M., Pan R., Tan L. Y., Zhang Z. G., Guo M. (2019). Pleiotropic roles of O-mannosyltransferase MoPmt4 in development and pathogenicity of Magnaporthe oryzae. Curr. Genet. 65 223–239. 10.1007/s00294-018-0864-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poli G., Leonarduzzi G., Biasi F., Chiarpotto E. (2004). Oxidative stress and cell signalling. Curr. Med. Chem. 11 1163–1182. 10.2174/0929867043365323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues A. M., Cruz Choappa R., Fernandes G. F., de Hoog G. S., de Camargo Z. P. (2016). Sporothrix chilensis sp. nov. (Ascomycota: Ophiostomatales), a soil-borne agent of human sporotrichosis with mild-pathogenic potential to mammals. Fungal Biol. 120 246–264. 10.1016/j.funbio.2015.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues A. M., de Hoog S., de Camargo Z. P. (2013). Emergence of pathogenicity in the Sporothrix schenckii complex. Med. Myco 51 405–412. 10.3109/13693786.2012.719648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossato L., Moreno L. F., Jamalian A., Stielow B., de Almeida S. R., de Hoog S., et al. (2018). Proteins potentially involved in immune evasion strategies in Sporothrix brasiliensis elucidated by ultra-high-resolution mass spectrometry. mSphere 3:e00514-17. 10.1128/mSphere.00514-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Y., Xiao G., Zheng P., Cen K., Zhan S., Wang C. (2016). Divergent and convergent evolution of fungal pathogenicity. Genome Biol. Evol. 8 1374–1387. 10.1093/gbe/evw082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpton T. J., Stajich J. E., Rounsley S. D., Gardner M. J., Wortman J. R., Jordar V. S., et al. (2009). Comparative genomic analyses of the human fungal pathogens Coccidioides and their relatives. Genome Res. 19 1722–1731. 10.1101/gr.087551.108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soberanes-Gutierrez C. V., Juarez-Montiel M., Olguin-Rodriguez O., Hernandez-Rodriguez C., Ruiz-Herrera J., Villa-Tanaca L. (2015). The pep4 gene encoding proteinase A is involved in dimorphism and pathogenesis of Ustilago maydis. Mol. Plant Pathol. 16 837–846. 10.1111/mpp.12240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y., da Silva N. M., Weiss V. A., Vu D., Moreno L. F., Vicente V. A., et al. (2020). Comparative genomic analysis of capsule-producing black yeasts Exophiala dermatitidis and Exophiala spinifera, potential agents of disseminated mycoses. Front. Microbiol. 11:586. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.00586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y., Li S. S., Zhong S. X., Liu Y. Y., Yao L., Huo S. S. (2013). Report of 457 sporotrichosis cases from Jilin province, northeast China, a serious endemic region. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 27 313–318. 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04389.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira M. M., de Almeida L. G. P., Kubitschek-Barreira P., Alves F. L., Kioshima E. S., Abadio A. K. R., et al. (2014). Comparative genomics of the major fungal agents of human and animal Sporotrichosis: Sporothrix schenckii and Sporothrix brasiliensis. BMC Genomics 15:943. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma S., Verma G. K., Singh G., Kanga A., Shanker V., Singh D., et al. (2012). Sporotrichosis in sub-himalayan India. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6:e1673. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk H., Marton K., Flajsman M., Radisek S., Tian H., Hein I., et al. (2019). Chitin-binding protein of Verticillium nonalfalfae disguises fungus from plant chitinases and suppresses chitin-triggered host immunity. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 32 1378–1390. 10.1094/Mpmi-03-19-0079-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman Z., Pinsky M., Wolfgeher D. J., Kron S. J., Truman A. W., Kornitzer D. (2020). Genetic analysis of Hsp70 phosphorylation sites reveals a role in Candida albicans cell and colony morphogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom. 1868:140135. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2018.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White M., Adams L., Phan C., Erdag G., Totten M., Lee R., et al. (2019). Disseminated sporotrichosis following iatrogenic immunosuppression for suspected pyoderma gangrenosum. Lancet Infect. Dis. 19 e385–e391. 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30421-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkens C., Svensson B., Moller M. S. (2018). Functional roles of starch binding domains and surface binding sites in enzymes involved in starch biosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 9:1652. 10.3389/fpls.2018.01652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang K., Liu Y., Wang S., Wu L., Xie R., Lan H., et al. (2019). Cyclase-associated protein cap with multiple domains contributes to mycotoxin biosynthesis and fungal virulence in Aspergillus flavus. J Agric Food Chem. 67 4200–4213. 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b07115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Hagen F., Stielow B., Rodrigues A. M., Samerpitak K., Zhou X., et al. (2015). Phylogeography and evolutionary patterns in Sporothrix spanning more than 14 000 human and animal case reports. Persoonia 35 1–20. 10.3767/003158515X687416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhi X. Y., Jiang Z., Yang L. L., Huang Y. (2017). The underlying mechanisms of genetic innovation and speciation in the family Corynebacteriaceae: a phylogenomics approach. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 107 246–255. 10.1016/j.ympev.2016.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X., Rodrigues A. M., Feng P. Y., de Hoog G. S. (2014). Global ITS diversity in the Sporothrix schenckii complex. Fungal Divers. 66 153–165. 10.1007/s13225-013-0220-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/ Supplementary Material.