Abstract

Background

Contact tracing remains a critical part of controlling COVID-19 spread. Many countries have developed novel software applications (Apps) in an effort to augment traditional contact tracing methods.

Aim

Conduct a national survey of the Irish population to examine barriers and levers to the use of a contact tracing App.

Methods

Adult participants were invited to respond via an online survey weblink sent via e-mail and messaging Apps and posted on our university website and on popular social media platforms, prior to launch of the national App solution.

Results

A total of 8088 responses were received, with all 26 counties of the Republic of Ireland represented. Fifty-four percent of respondents said they would definitely download a contact-tracing App, while 30% said they would probably download a contact tracing App. Ninety-five percent of respondents identified at least one reason for them to download such an App, with the most common reasons being the potential for the App to help family members and friends and a sense of responsibility to the wider community. Fifty-nine percent identified at least one reason not to download the App, with the most common reasons being fear that technology companies or the government might use the App technology for greater surveillance after the pandemic.

Conclusion

The Irish citizens surveyed expressed high levels of willingness to download a public health–backed App to augment contact tracing. Concerns raised regarding privacy and data security will be critical if the App is to achieve the large-scale adoption and ongoing use required for its effective operation.

Keywords: App, Contact tracing, Coronavirus, COVID-19, Online survey, Public opinion

Introduction

Until a vaccine or efficacious treatment emerge, the key to limiting the harm caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and its associated disease (COVID-19) is to identify and quarantine infected individuals as quickly as possible. China and neighboring countries have shown that an aggressive public health response involving rapid isolation of infected people and their close contacts can help contain the virus, thus reducing the number of patients requiring hospital-level care at any one time [1, 2]. Asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic spread of COVID-19 further underlines the importance of timely and effective contact tracing [3, 4].

Given the scale and gravity of the problem, novel software applications (“Apps”) that can potentially simplify the laborious work of contact tracing are a tempting prospect [5]. These Apps use modern smartphone technology to record details of other smartphones in the user’s vicinity, record smartphone location, or both, to determine the recent contacts of those who subsequently test positive for the virus [6]. While the evidence for contact tracing Apps is limited, in a global pandemic with a novel virus, many countries have designed and deployed Apps before their efficacy can be proven [7].

Researchers from the University of Oxford have estimated that if 56% of people were to download an ideal contact-tracing App in the UK, this would be enough to control the disease by itself [8]. However, the authors clearly state in the same document, “lower numbers of App users will also have a positive effect.” Indeed, the designers of Singapore’s TraceTogether App state that these Apps should be viewed as an adjunct to a human-fronted process and not a panacea to end the pandemic [9].

The technological and privacy challenges associated with such Apps are considerable, and there is much for governments and public health bodies to consider [10, 11]. The announcement of the “Exposure Notification” Application Programming Interface (API) as a joint venture by software companies Google and Apple on 20 May 2020 introduces a more direct means to access the Bluetooth technology harnessed by earlier Apps [12, 13]. The Irish government have committed to building a free-to-download, free-to-use Irish contact-tracing App based on the Exposure Notification API. The initial specification document states that anyone will be able to use the App if they have a smartphone that is “less than 5 years old” [14].

It remains unclear what proportion of a population must use a contact tracing App for it to make an effective contribution to a COVID-19 response. It will be dependent on many factors, including the App’s technological efficacy and the burden of COVID-19 in communities. However, what is clear is that any contact tracing App solution can only be effective if it is trusted, downloaded, and used by a significant number of citizens. The more people that download and use the App, the more the number of contacts between people will be silently logged by the App.

This study aims to gather “a priori” evidence from the Irish general public via an online survey concerning contact tracing Apps and relevant barriers deemed important to the adoption of such technologies, before any such App was available. While a pandemic of this scale has not been witnessed for more than a century, this is the third worrying outbreak of a potentially lethal coronavirus in the past 20 years [15]. How long countries will have to fight to suppress COVID-19 is unknown, yet it is likely that lessons learned from this pandemic, including those around use of technology, will prove useful for future infectious disease outbreaks.

Objective

The aim of this research is to conduct a national online survey with a large sample of the Irish population to examine barriers and levers to the use of a contact-tracing App to aid in the suppression of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

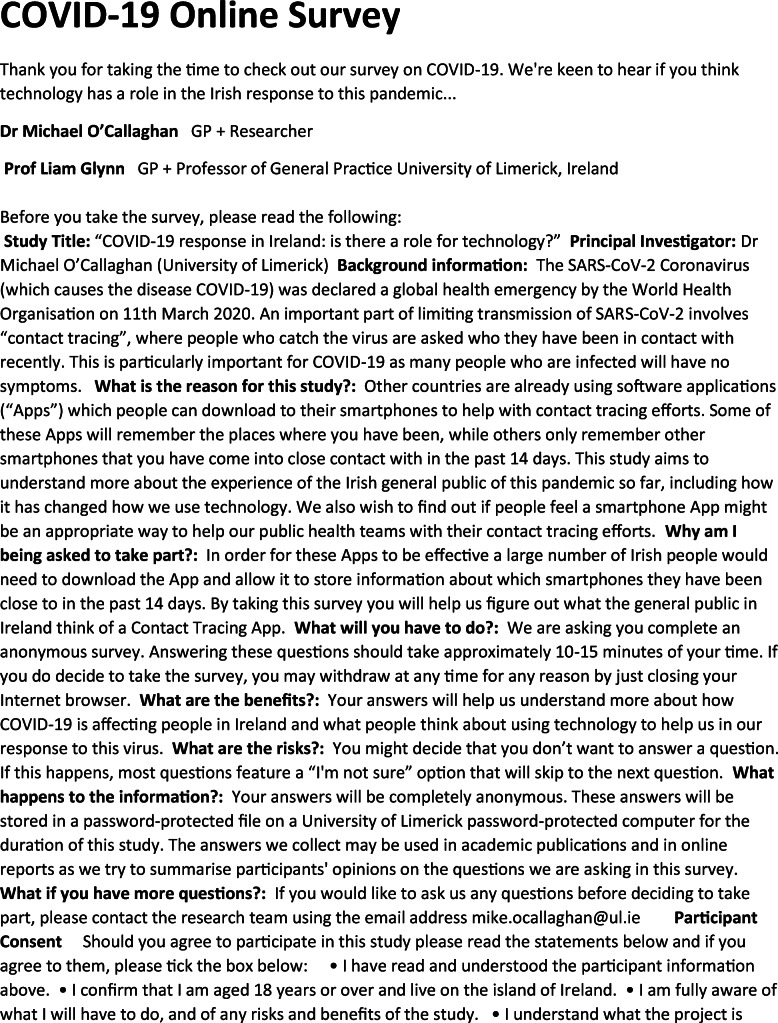

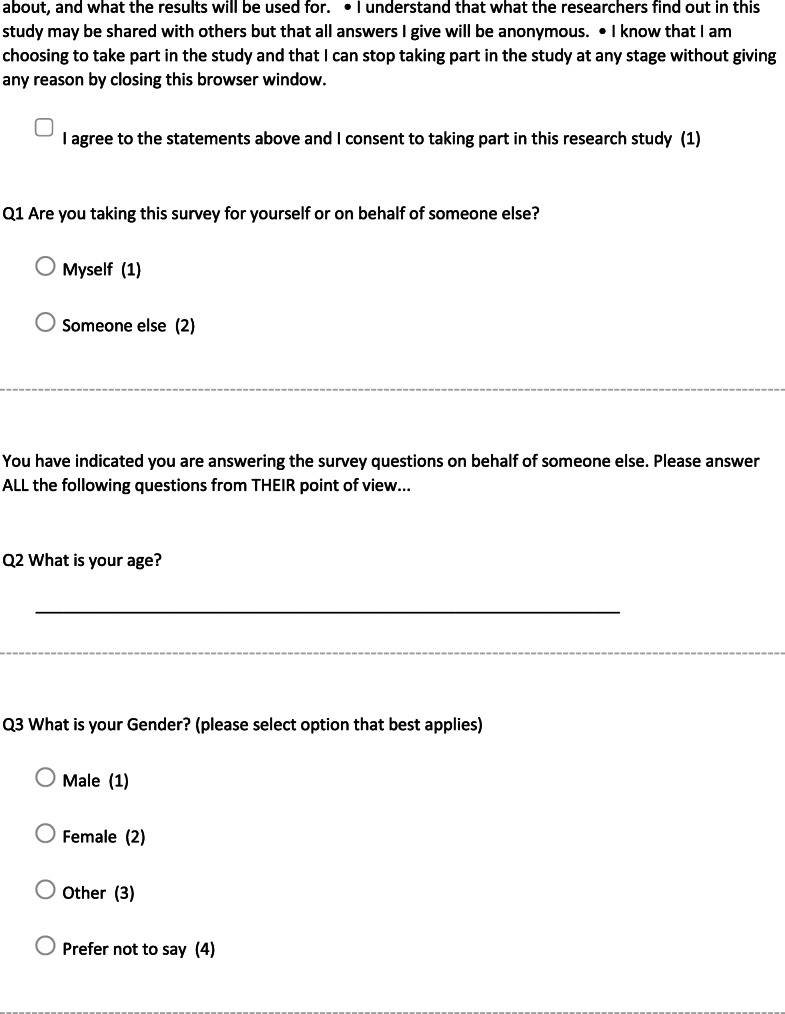

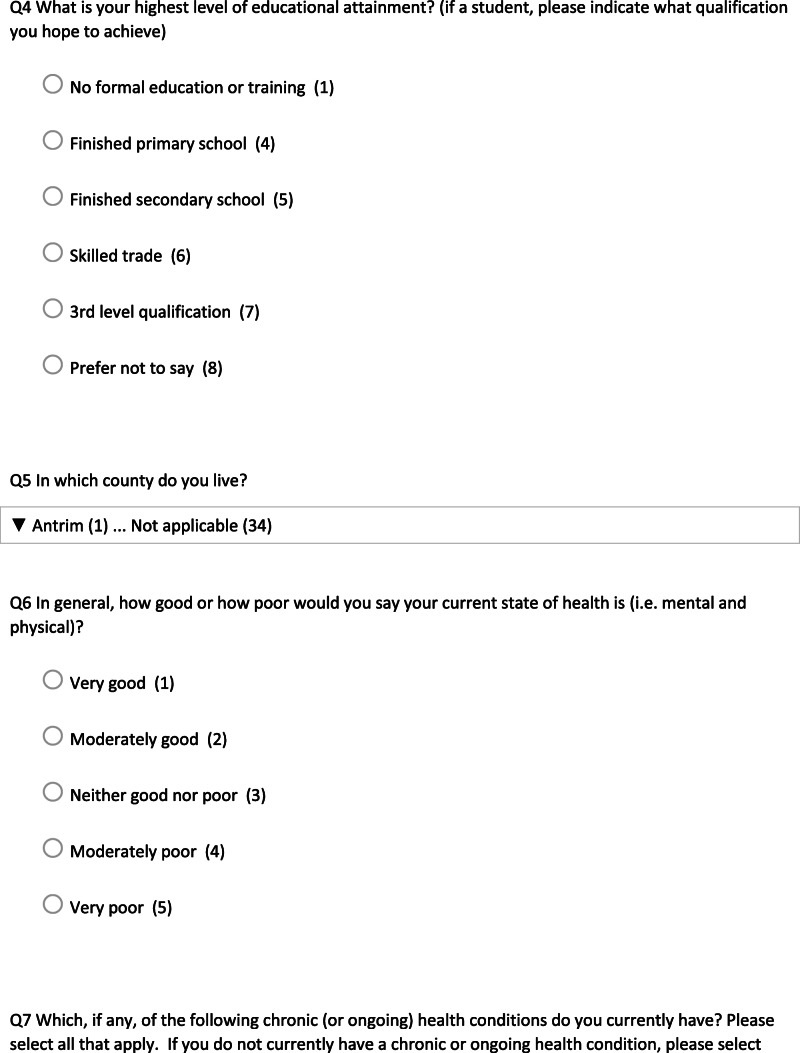

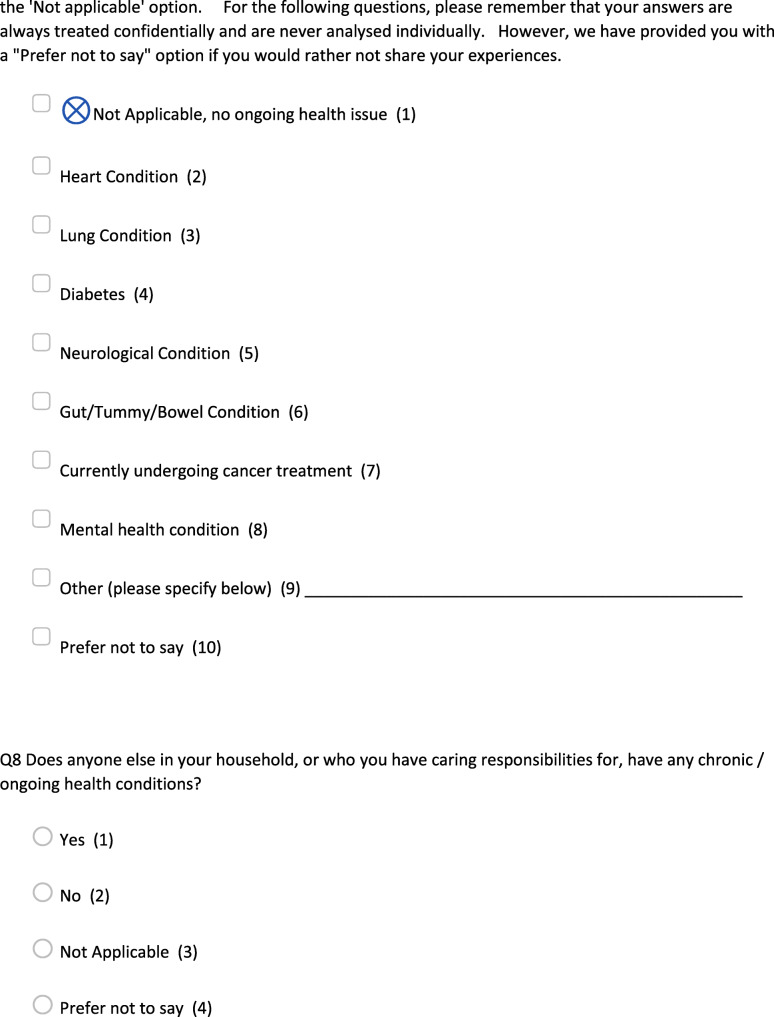

A 37-item online survey was designed and piloted by researchers at the University of Limerick Graduate Entry Medical School (GEMS), Science Foundation Ireland Research Centre for Software (LERO), and the National University of Ireland Galway (NUIG) College of Medicine, Nursing and Health Sciences.

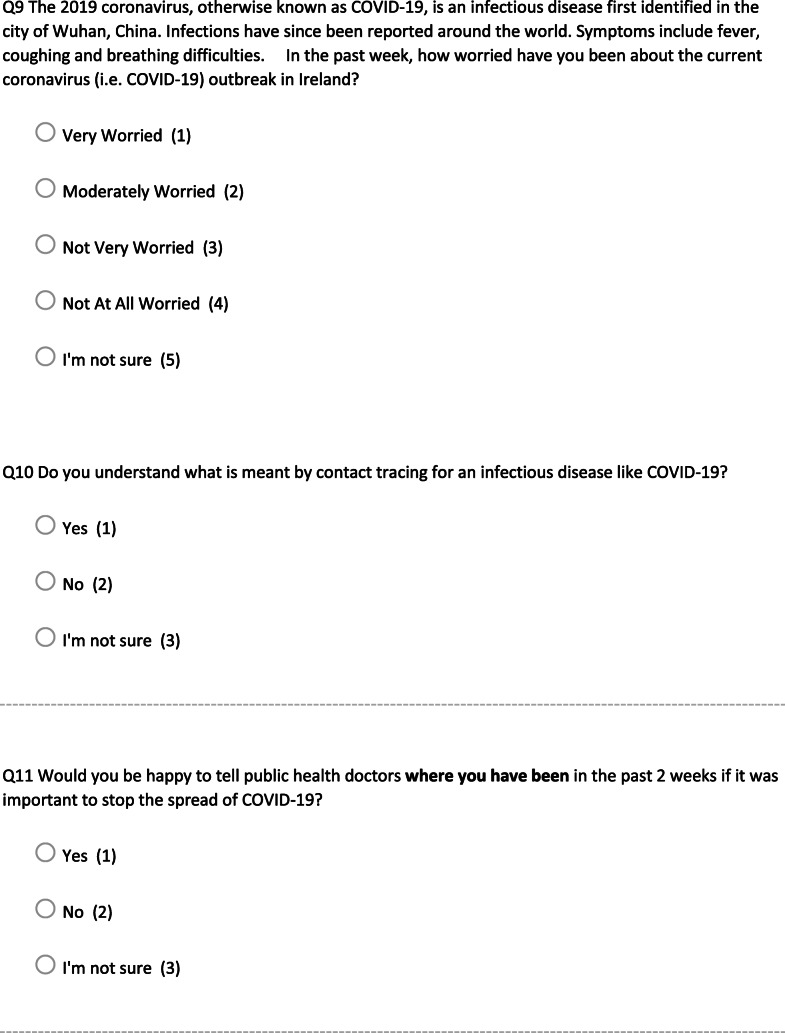

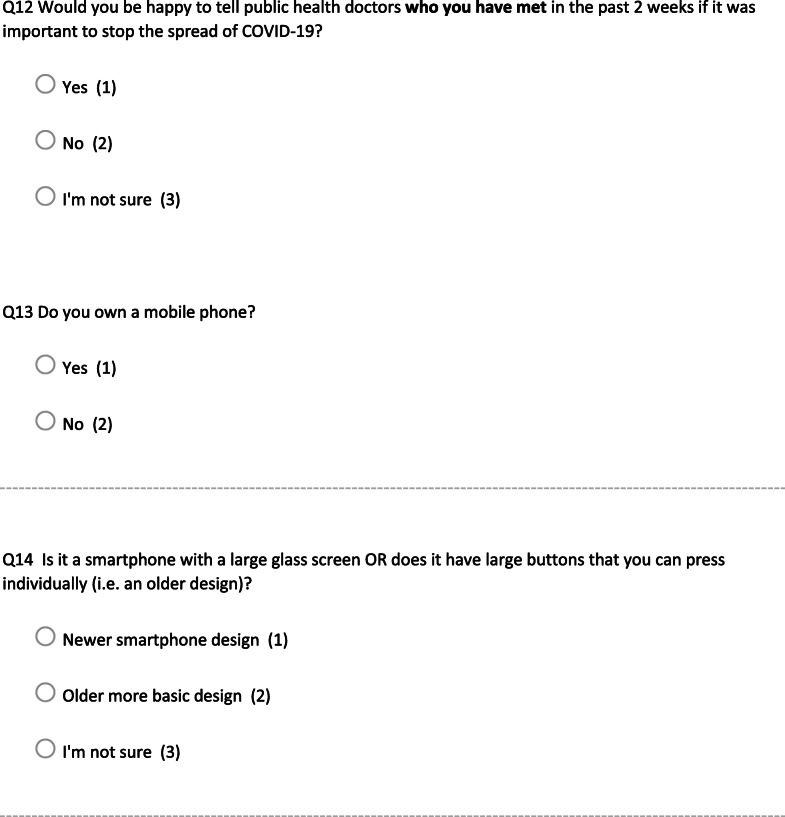

The final survey (see Appendix) was released via Qualtrics XM survey software [16] and featured five questions adapted from the Imperial College London “Public Response to UK Government Recommendations on COVID-19” population survey [17] and four questions adapted from the Oxford University survey of acceptability of a contact-tracing App [18].

The survey was released through social media platforms (Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIN, and Instagram), the University of Limerick website, and university e-mailing lists and via WhatsApp Messenger group conversations on Friday, 22 May, at 12 p.m. The survey was live for 7 days, and the respondents were advised they needed to be aged 18 or older when taking the survey. While plans to develop an Irish contact-tracing App had been released in April [14], the Irish health service–endorsed contact-tracing App solution was launched in early July.

In light of the potential for self-selection bias of respondents more familiar with technology, respondents were encouraged to discuss the survey with friends and family so that the survey could be completed on behalf of another person who may not be regularly online. The survey was carried out during the first week of easing of widespread societal restrictions which had been in place in the RoI for the previous 10 weeks.

Ethical approval for this project was granted by the University of Limerick Education and Health Sciences (EHS) ethics committee [study ID 2020_04_18_EHS (ER), approved 21 May 2020].

Statistical analysis

All analyses were carried out in R v3.6 [19]. Descriptive statistics are used to present the findings of demographics and attitudes of the respondents to the COVID-19 crisis, contact tracing, and the relevant technologies.

For the primary measure of interest, willingness to download the App, the survey data were weighted by gender and education to better reflect the Irish population. The population distribution of gender (50% male and female) and education (42% tertiary, 45% secondary, 13% primary or no formal education) was taken from census data recorded by the Central Statistics Office of Ireland [20].

We report univariate summaries of key survey questions, with the primary response being willingness to install the App. Chi-squared tests for association were carried out to investigate whether gender, age group, education level, or level of worry regarding COVID-19 were related to willingness to install.

Results

A total of 8088 complete responses were recorded. Just 27 responses were returned on behalf of others. Responses were received from all 26 counties in the Republic of Ireland, with most responses received from the major population centers of Dublin, Cork, Limerick, and Galway. The median age of respondents was 39 years, and mean age was 41 years. Eighty-one percent of respondents were female. Regarding highest educational attainment, 7124 (87%) of respondents reported having a 3rd level qualification.

Overall physical and mental health was reported to be “very good” by 4249 (53%) respondents, while 3208 (40%) felt their health was “moderately good.” Regarding chronic disease, 2519 (31%) of respondents indicated they had at least one chronic health issue. SARS-CoV-2-related anxiety in the previous week was assessed, with 878 (11%) of respondents reporting they had been “very worried,” while 4588 (57%) were “moderately worried.”

When asked about contact tracing, 7929 (98%) respondents understood the concept, while 7770 (96%) agreed they would tell public health doctors where they had been and who they had met recently, if it was important to stop the spread of COVID-19.

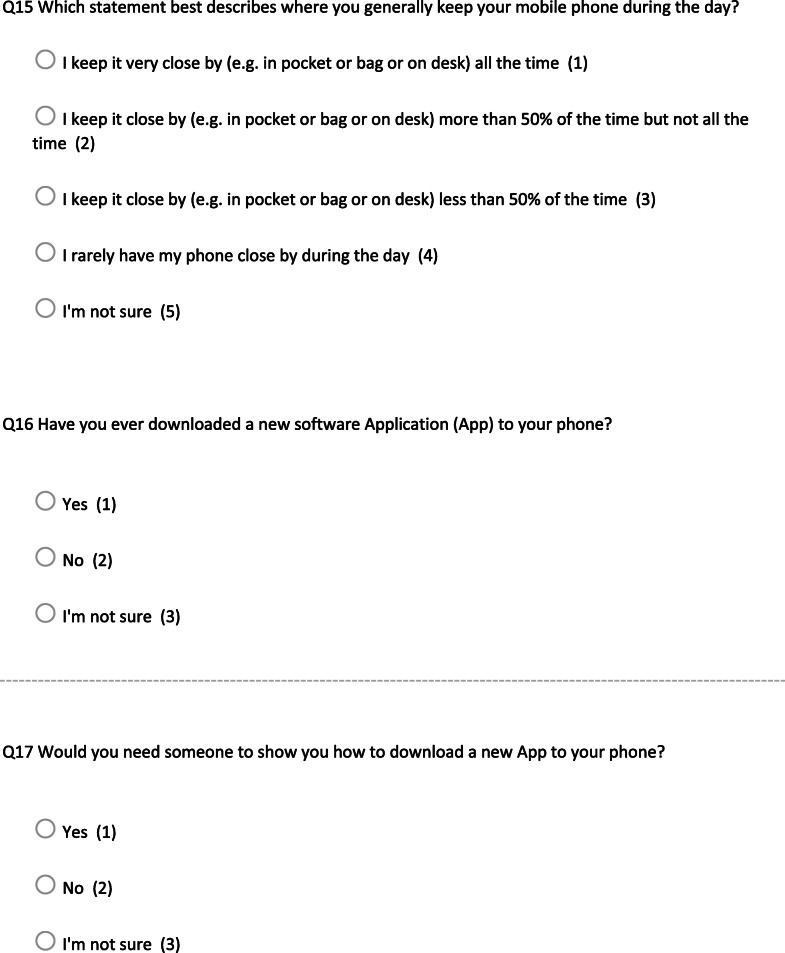

Just 6 respondents indicated they do not own a mobile phone. Of the mobile phone owners, 8036 (98%) own a smartphone, 7863 (98%) of these respondents had downloaded an App before, and 7781 (97%) stated that they would not need help to download an App to their smartphone. Just over two-thirds (68%) of smartphone owners indicated they keep their phones “very close by (e.g., in pocket, bag or on the desk) all the time”. A further 2211 (28%) indicated they keep their smartphones “very close by (e.g., in pocket, bag or on the desk) more than 50% of the time.”.

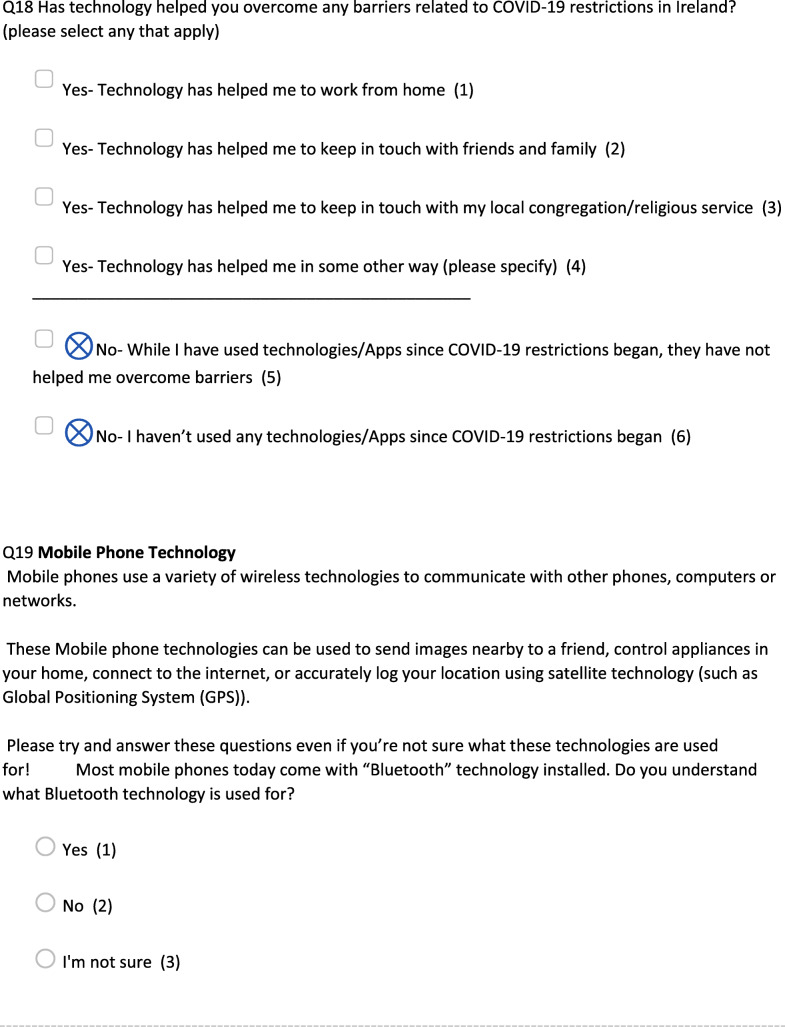

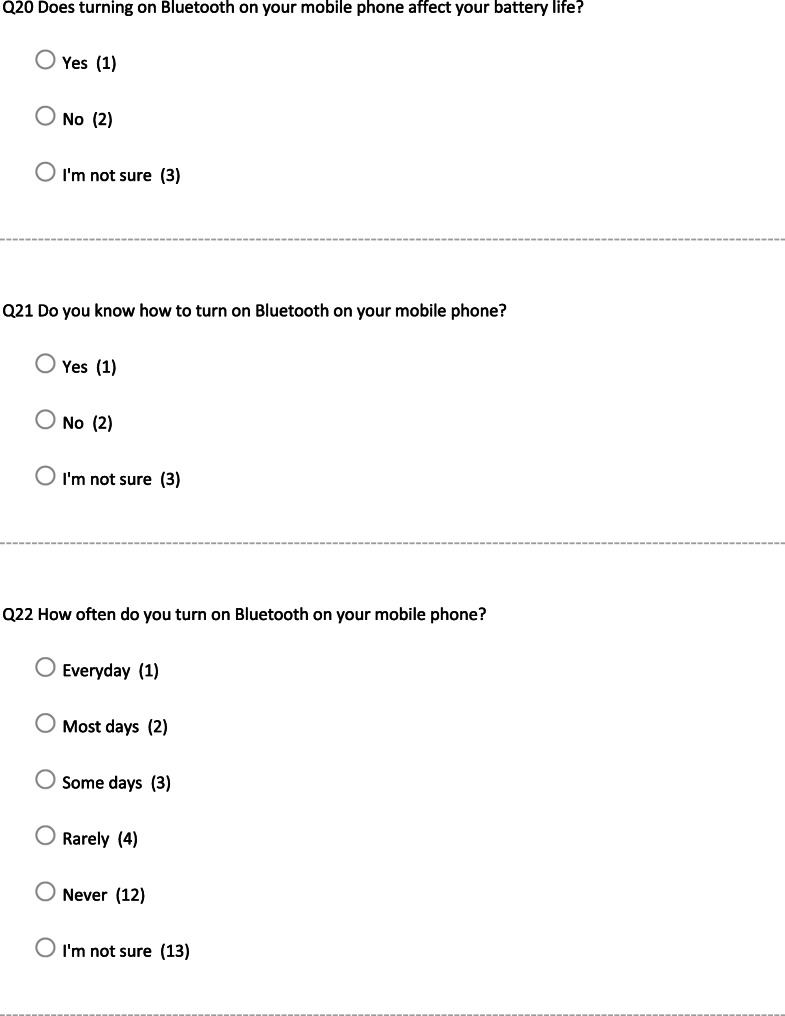

The majority of respondents (7757 or 96%) indicated they understand what Bluetooth technology is used for, and 7921 (98%) know how to turn on this function on their phone. Fifty-five percent of respondents (4444) stated that they believed Bluetooth adversely affects device battery life. Bluetooth use was common among owners of smartphones, with 4995 (63%) using it “Everyday” or “Most days.”

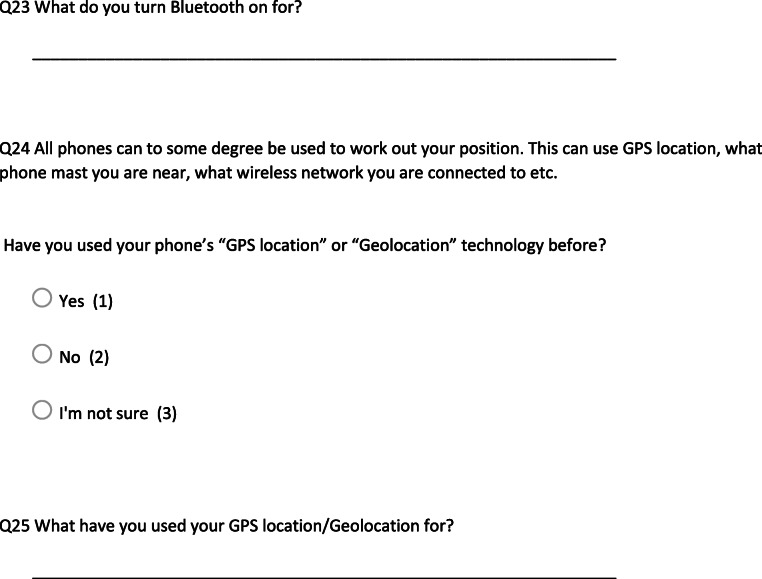

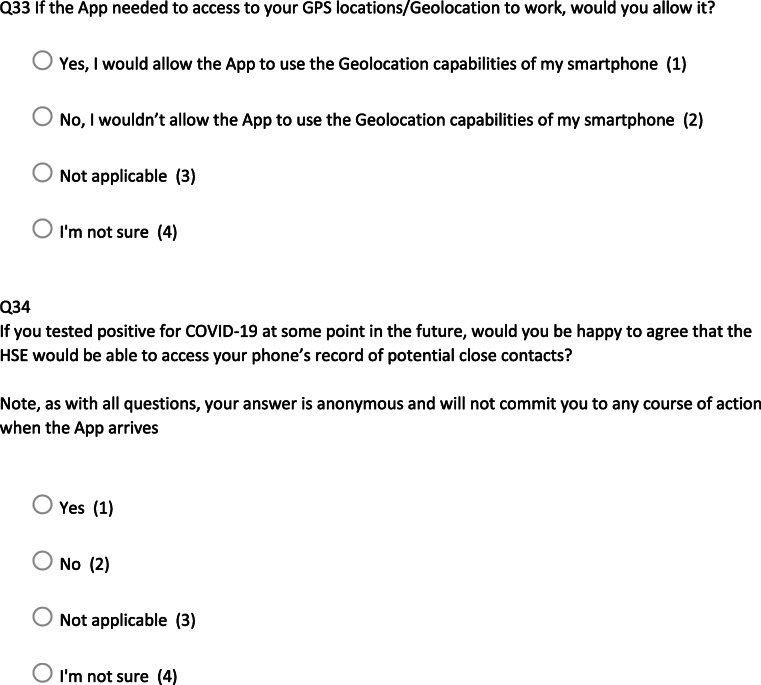

Use of geolocation technology was reported by 7026 (89%) of smartphone users. Of smartphone users, 5931 (75%) would be willing to allow the App to access the geolocation capabilities of their phone.

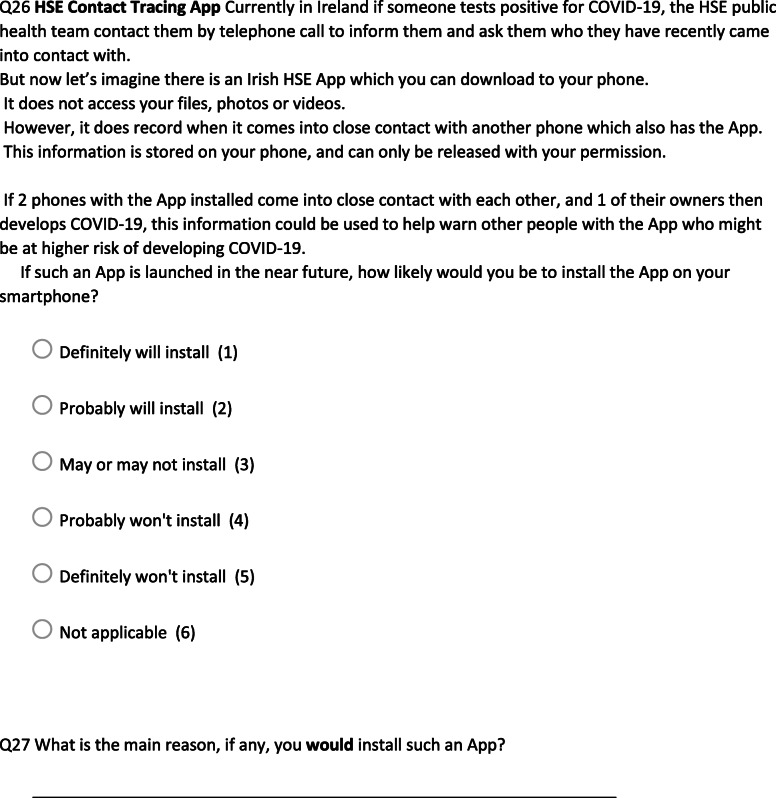

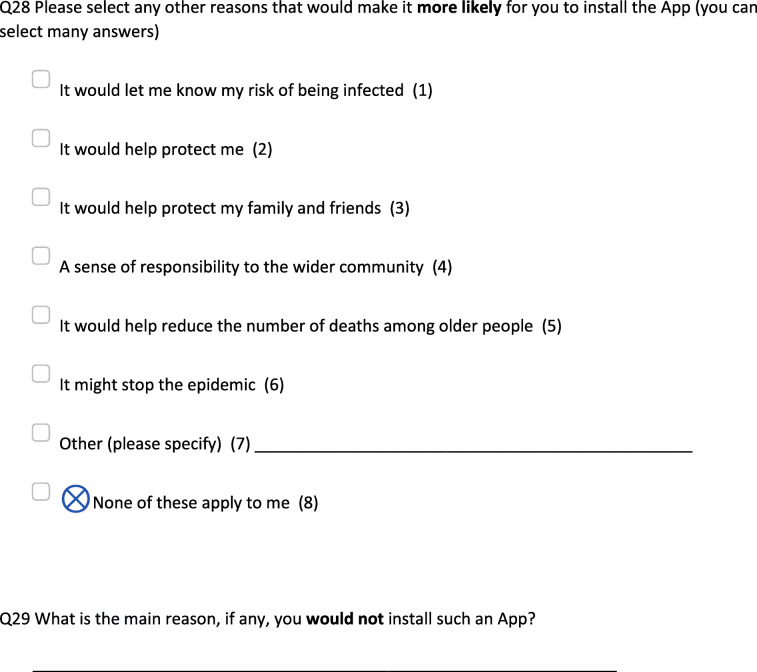

Respondents were asked to select from a list of options reasons that would encourage them to install the App (see Table 1). In rank order, 6395 (79%) felt the App would “help protect my family and friends”, 6338 (78%) felt “a sense of responsibility to the wider community,” while 5725 (71%) felt it would “let me know my risk of being infected.” Additional free text responses included “if the App was shown to be effective” and “if it was shown to be secure.”

Table 1.

Barriers/levers encouraging and discouraging App download

| Total responses | % respondents | |

|---|---|---|

| Reasons that would make it more likely for you to install the App (you can select many answers) | ||

| It would help protect my family and friends | 6395 | 79.1 |

| A sense of responsibility to the wider community | 6338 | 78.4 |

| It would let me know my risk of being infected | 5725 | 70.8 |

| It would help protect me | 5239 | 64.8 |

| It would help reduce the number of deaths among older people | 5148 | 63.6 |

| It might stop the epidemic | 4496 | 55.6 |

| None of these apply to me | 437 | 5.4 |

| Other (please specify) | 305 | 3.8 |

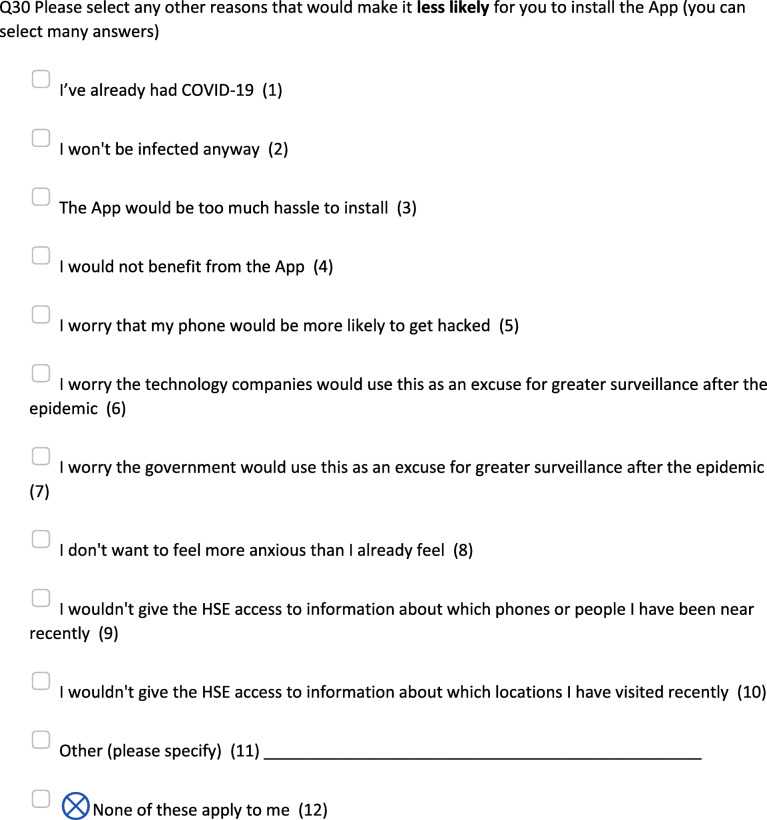

| Reasons that would make it less likely for you to install the App (you can select many answer) | ||

| I worry the technology companies would use this as an excuse for greater surveillance after the pandemic | 3342 | 41.3 |

| None of these apply to me | 3335 | 41.2 |

| I worry the government would use this as an excuse for greater surveillance after the pandemic | 2636 | 32.6 |

| I worry that my phone would be more likely to get hacked | 1742 | 21.5 |

| I do not want to feel more anxious than I already feel | 653 | 8.1 |

| I would not give the HSE access to information about which locations I have visited recently | 645 | 8.0 |

| I would not give the HSE access to information about which phones or people I have been near recently | 609 | 7.5 |

| Other (please specify) | 350 | 4.3 |

| I would not benefit from the App | 112 | 1.4 |

| I’ve already had COVID-19 | 102 | 1.3 |

| The App would be too much hassle to install | 99 | 1.2 |

| I will not be infected anyway | 26 | 0.3 |

While 3335 (41%) of respondents could see no reason not to install the App, the remaining 59% of respondents selected at least one option from a list of 10 options. “I worry technology companies will use this as an excuse for greater surveillance after the pandemic” was selected by 3342 (41%) respondents, “I worry the government would use this as an excuse for greater surveillance after the pandemic” was selected by 2636 (33%) people, and “I worry that my phone would be more likely to get hacked” was selected by 1742 (22%) of respondents.

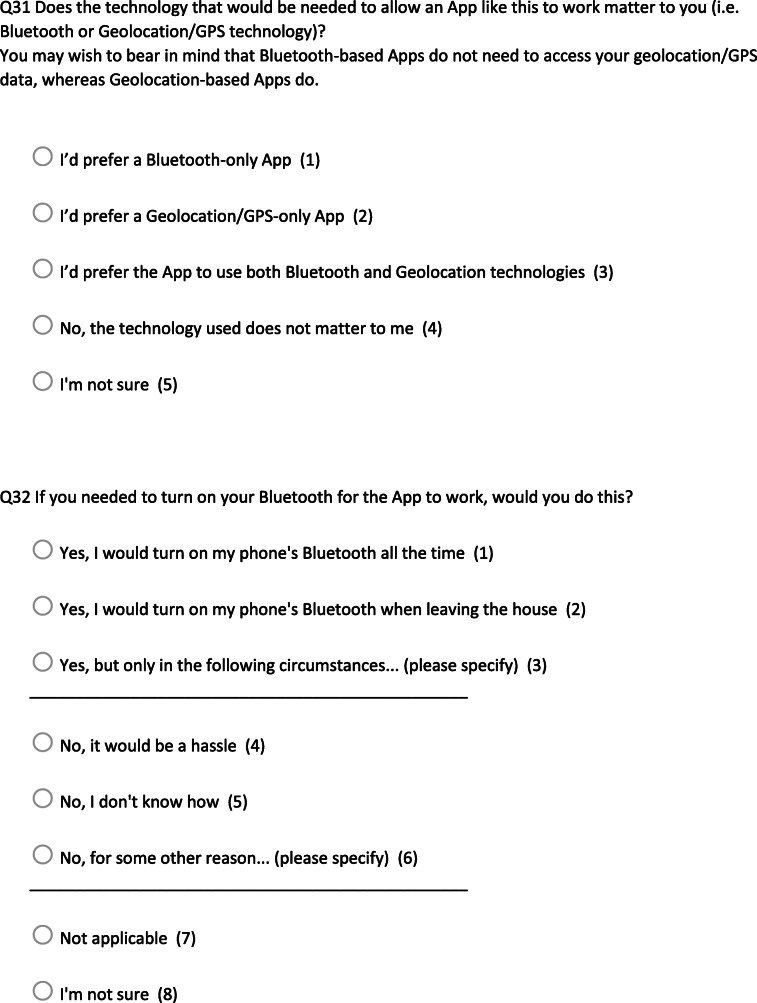

In terms of preference for choice of the App technology, 3907 (48%) of total respondents stated it did not matter to them. For the 4181 who expressed a preference, 1569 (38% of this group) preferred a Bluetooth-only App, 1344 (32%) were unsure, 738 (18%) would like an App that uses Bluetooth and Geolocation technology, and 530 (13%) would like to see a Geolocation-only App.

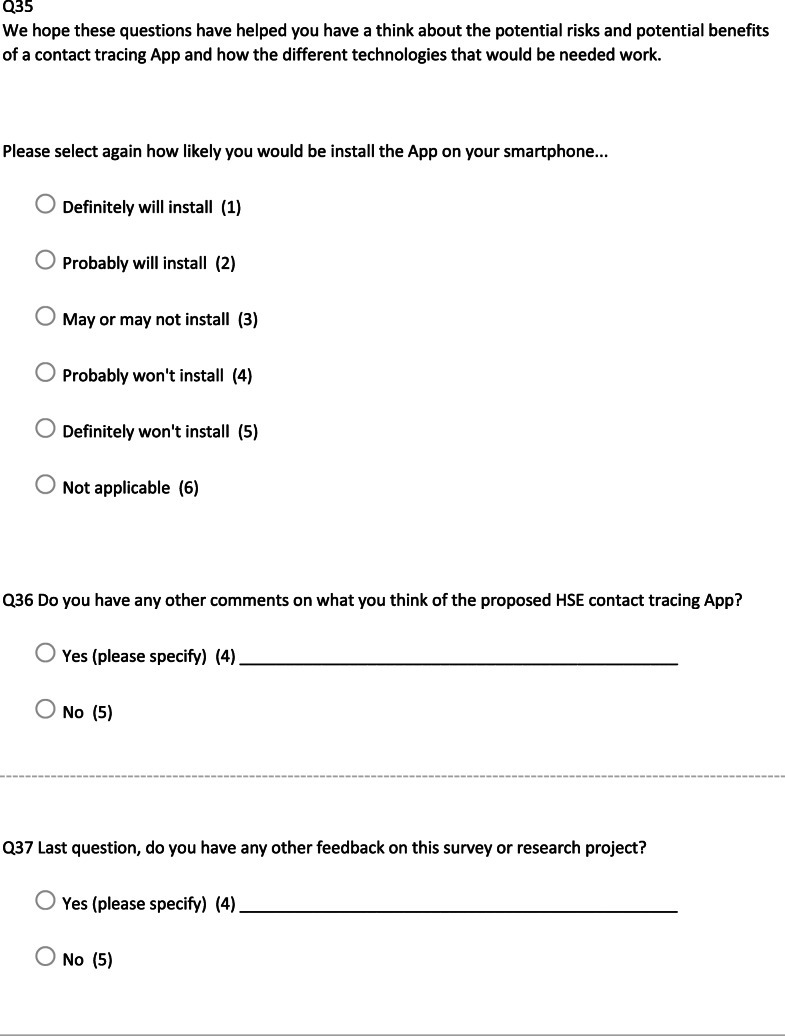

Weighted analyses

Initially, 58% percent of respondents indicated they “definitely will install” the App, with a further 25% indicating they “probably will install” the App. Eight percent indicated they “may or may not install”, 3% indicated they “probably won’t install,” while 6% stated they “definitely won’t install” the App. Following several questions containing more detailed information about the technologies involved in contact-tracing Apps and some potential push and pull factors regarding adoption (see Table 1), 54% of respondents indicated they definitely will install the App, 30% indicated they probably will install the App, and 7% indicated they may or may not install the App. Selection of the two remaining options for this question did not change.

There is evidence for an association between gender and unwillingness to install the App, with males more likely to respond that they probably or definitely will not install the app (11% vs 6% in females). There is also evidence for an association with age group, with the oldest and youngest groups most likely to indicate they probably or definitely will install the App. Finally, COVID-related worry was associated with willingness to install—those “Not At All Worried” about COVID were far more likely to respond that they definitely will not install the App (34% vs 6% or lower in those more worried about COVID).

Discussion

Summary of main findings

This survey has found considerable willingness among Irish citizens to download a public health service–endorsed COVID-19 contact tracing App. It was an acceptable intervention to a large majority (82%) of our sample. This did not alter significantly following mention of the type of technology involved or issues surrounding tracing of close contacts or location data.

Our sample was heavily skewed toward female participants; those with higher educational attainment and the 18–29-year and 30–41-year age groups were overrepresented when compared with the Irish population. This is partly explained by our survey invitation gaining traction with the online “followers” of a popular female Irish general practitioner who encouraged completion of the survey. This single endorsement was followed by almost 3000 responses being received from young females in a 24-h period. However, weighting for gender did not significantly change the primary outcome measure of willingness to download the App. Forty-two percent of Irish citizens possess a third-level qualification, compared with 82% of our cohort. Higher educational attainment has an age gradient in Ireland [20], and thus, this may be partly explained by the fact our sample was younger than the population, yet likely also reflects our chosen methodology where participants were primarily recruited using online platforms.

Ninety-two percent of our cohort reported good or very good health, which is greater than the 84% seen in the Healthy Ireland survey report 2019 [21]. Regarding chronic disease, 69% of our cohort reported no chronic illness, which is in line with the 68% reported in the Health Ireland survey. Poorer self-reported health status did not translate to increased willingness to download a contact-tracing App. Indeed, those with very good health were most likely to “definitely” download the App. However, respondents’ level of worry about COVID-19 in the past week did influence expressed willingness to download the App. While 2% of those very worried about COVID-19 would definitely not install the App, 38% of the 478 respondents not at all worried about COVID-19 said they definitely would not install the App. This may be a relevant area for public awareness campaigns when the Irish App is released.

Smartphone ownership of 98% is higher than the 91% reported in the 2019 Global Mobile Consumer Survey [22] and may be explained by the ease with which online surveys can be taken using a smartphone’s Internet browser. That 96% of respondents keep their phone very close by more than 50% of the time is important if detection of a smartphone’s Bluetooth signal by the App will act a proxy for its owner’s precise location.

While a number of responses were received from people aged 65 and above (563 (7%)), very few responses were received on behalf of other people. It was hoped to capture more opinions from less technologically adept citizens in this survey by encouraging respondents to discuss it with friends and family. Of the people aged 65 and above, 14% were very worried about COVID-19, 91% had a smartphone, and 91% said they would probably or definitely install the contact-tracing App.

While selection bias and other sampling issues inherent in online surveys are well described, online survey methods are quick and can be used to reach a wide audience [23, 24]. The latter characteristics of online surveys were attractive in the early stages of this pandemic and have allowed us to quickly inform a national discussion concerning the Irish contact-tracing App. However, planned qualitative work will be critical to gather opinions and attitudes of underrepresented and hard-to-reach cohorts if App deployment is to avoid a digital divide that mirrors well-established socioeconomic patterns of engagement with the healthcare system.

A good level of knowledge of Bluetooth technology and prior use of Bluetooth technology was reported by the majority of our respondents. However, if the Google/Apple Exposure Notification API bypasses the manual step of turning on Bluetooth and enabling the App to access it, these findings may not be as relevant. A large portion (3907 (48%)) of respondents indicated they had no preference for the technology the Irish contact-tracing App uses. However, an App featuring geolocation technology was only preferred by 16% of respondents. One quarter of respondents indicated they would not permit a contact-tracing App to access geolocation data. While fully anonymized geolocation data in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic is not likely to cause any data protection issues per se [25], it may hinder adoption of the App among some cohorts of the population, particularly given the types of barriers described in Table 1.

Strengths and limitations

This study captured data from a large sample of the general public in the Republic of Ireland using an online survey tool. However, our sample comprised a higher proportion of smartphone owners than is seen nationally, and selection bias effects regarding more technologically adept citizens are a limitation. If those taking part in this study are more or less likely to download the App compared with those who did not take part, then willingness to download at a population level may be different to this study’s estimates. Given the nature of the online survey, our results may represent an upper bound for willingness to install the app. Additionally, our sample was younger than the Irish population, comprised more females, and had a higher level of educational attainment than the Irish population. However, given the size of our sample, weighting to resolve these sampling issues was possible and did not significantly alter our main findings (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Participant demographics, education, COVID-related worry, and health self-report versus final intention to download HSE contact-tracing App—unweighted totals and weighted responses shown

| Unweighted responses | Weighted responses (weighted by gender and educational attainment) | p value (chi-squared test) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % | 1. Definitely will install | 2. Probably will install | 3. May or may not install | 4. Probably will not install | 5. Definitely will not install | 6. Not applicable | Total | % | ||

| Gender | |||||||||||

| Female | 6584 | 81.4 | 2135 (53%) | 1236 (31%) | 377 (9%) | 90 (2%) | 176 (4%) | 11 (0%) | 4025 | 50.0 | |

| Male | 1466 | 18.1 | 2197 (55%) | 1168 (29%) | 220 (5%) | 146 (4%) | 288 (7%) | 5 (0%) | 4024 | 50.0 | |

| Other | 6 | 0.1 | p = 0.004 | ||||||||

| Prefer not to say | 32 | 0.4 | |||||||||

| Total | 8088 | 4332 (54%) | 2404 (30%) | 597 (7%) | 236 (3%) | 464 (6%) | 16 (0%) | 8049 | |||

| Education | |||||||||||

| Primary/none | 43 | 0.5 | 713 (68%) | 281 (27%) | 26 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 26 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1046 | 13.0 | |

| Secondary | 955 | 11.8 | 1895 (52%) | 1110 (31%) | 238 (7%) | 128 (4%) | 244 (7%) | 7 (0%) | 3622 | 45.0 | p = 0.064 |

| Tertiary | 7012 | 86.7 | 1688 (51%) | 995 (30%) | 322 (10%) | 104 (3%) | 183 (6%) | 8 (0%) | 3300 | 41.0 | |

| Undisclosed | 78 | 1.0 | 37 (46%) | 18 (22%) | 10 (12%) | 3 (4%) | 12 (15%) | 1 (1%) | 81 | 1.0 | |

| Total | 8088 | 4333 (54%) | 2404 (30%) | 596 (7%) | 235 (3%) | 465(6%) | 16 (0%) | 8049 | |||

| COVID-19-related worry | |||||||||||

| Very worried | 878 | 10.9 | 767 (71%) | 224 (21%) | 41 (4%) | 21 (2%) | 25 (2%) | 2 (0%) | 1080 | 13.4 | |

| Moderately Worried | 4588 | 56.7 | 2344 (55%) | 1380 (32%) | 327 (8%) | 102 (2%) | 92 (2%) | 5 (0%) | 4250 | 52.8 | |

| Not Very Worried | 2120 | 26.2 | 1002 (49%) | 639 (31%) | 192 (9%) | 94 (5%) | 129 (6%) | 5 (0%) | 2, 061 | 25.6 | p < 0.001 |

| Not At All worried | 478 | 5.9 | 206(32%) | 157 (25%) | 36 (6%) | 19 (3%) | 218 (34%) | 4 (1%) | 640 | 7.9 | |

| I’m Not Sure | 24 | 0.3 | 13 (65%) | 4 (20%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 20 | 0.2 | |

| Total | 8088 | 4332 (54%) | 2404 (30%) | 597 (7%) | 237 (3%) | 465 (6%) | 16 (0%) | 8051 | |||

| Self-reported health | |||||||||||

| Very Good | 4249 | 52.5 | 2261 (56%) | 1095 (27%) | 287 (7%) | 100 (2%) | 255 (6%) | 6 (0%) | 4004 | 49.7 | |

| Moderately Good | 3208 | 39.7 | 1657 (51%) | 1078 (33%) | 258 (8%) | 107 (3%) | 144 (4%) | 9 (0%) | 3253 | 40.4 | |

| Neither Good nor Poor | 402 | 5.0 | 293 (55%) | 167 (32%) | 27 (5%) | 20 (4%) | 23 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 530 | 6.6 | p = 0.013 |

| Moderately Poor | 209 | 2.6 | 113 (48%) | 61 (26%) | 23 (10%) | 8 (3%) | 30 (13%) | 1 (0%) | 236 | 2.9 | |

| Very Poor | 20 | 0.2 | 8 (33%) | 2 (8%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 13 (54%) | 0 (0%) | 24 | 0.3 | |

| Total | 8088 | 4332 (54%) | 2403 (30%) | 596 (7%) | 235 (3%) | 465 (6%) | 465 (6%) | 16 (0%) | 8047 | ||

The survey was deployed at a time of considerable uncertainty where the optimal response to the pandemic and the role that technology might play was unclear [10, 11]. Expressions of concern around potential privacy issues associated with contact-tracing Apps [26, 27] and discussion around potential, but as yet unproven, benefits [28] were reported widely in the mainstream media around this time, which may have influenced results.

Implications for research and practice

It seems that the primary driver for people’s willingness to download a public health–backed contact-tracing App during the current crisis is a desire to help others and “for the greater good.” Forty-one percent of our sample did not feel any of our presented options would dissuade them from downloading the App (see Table 1). However, privacy issues and worries regarding technology companies, governments, and hackers capitalizing on perceived security weaknesses resulting from such an App were expressed by many respondents. Plans to release the source code of the Irish contact-tracing App are welcome and may help reassure people in this regard [14].

Analysis of free text responses yielded interesting insights and suggestions for the App. Some respondents stated that they would be more likely to install the App if there was clear evidence that it was effective. There were also several technology-based suggestions for the App. Battery life concerns led some respondents to suggest integrating a feature which automatically enables Bluetooth when the user leaves their primary residence or workplace (e.g., the App is activated when the phone is disconnected from home or work Wi-Fi). Another suggestion involves pre-setting times for the App to be active, which correspond with their work, travel, or shopping schedule in an effort to conserve battery life. Finally, use of Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) technology where possible may be another worthwhile feature.

Assessing willingness to download contact tracing Apps has been estimated by large surveys in the UK, Italy, Germany, France, and the USA. In keeping with our study, 75% of respondents in these countries indicated comparable willingness to download a similar contact tracing App [29]. How intent to download translates to actual downloads and ongoing use remains to be seen as contact-tracing Apps in the countries listed above are all in development or in early stages of deployment.

However, Singapore deployed their TraceTogether App in late March and 10 weeks later, as of early June, 28% of Singaporeans have downloaded the App [30]. In Australia, 64% of respondents in a large survey conducted in early April stated they would download a Bluetooth tracking App [31]. Follow up survey by the same research group 12 days after launch of the Australia “COVIDSafe” App established that 44% of respondents had downloaded the App [32]. Of respondents who downloaded the App, 1 in 10 was not using it. At a population level, it is estimated that approximately six million Australians (20% of the population) have downloaded the COVIDSafe App [33]. Iceland is considered to have had the most successful adoption of a national contact-tracing App, and currently, almost 40% of their population of 340,000 has voluntarily downloaded the Rakning-19 App [34, 35]. China and India have made use of COVID-19 Apps mandatory [36], but it is unlikely western democracies will opt for this strategy.

Each country’s response thus far to COVID-19 is so varied, from testing to media reporting, that it is no surprise that a one-size-fits-all approach is unlikely to exist for COVID-19 contact tracing Apps. There are a number of technological issues that are likely to negatively impact on download and usage rates. The App being developed for the Republic of Ireland will only work on newer smartphones, and all smartphone users will need to update their operating system to install the new API being developed by Google/Apple. Each of the barriers described here presents an additional hurdle for an undetermined proportion of the population, and each will lead to incremental reductions in App usage.

Conclusion

To date, the international evidence for contact tracing Apps remains limited. Despite this, our study indicates a significant majority of the Irish general public express a willingness to download an App which aims to augment our existing contact tracing process. Issues raised around privacy, data protection, and some mistrust of technology companies and government remind us that any App will need to have transparency at its core and defined timelines for operation.

App download and ongoing use are two separate challenges, and to ensure both occur, it will be important to generate evidence that this App is useful to our country’s contact tracing efforts. While it is difficult to quantify the benefit of a single measure when several measures are simultaneously active, it may be beneficial to keep the public informed on key data relating to the App, including downloads, active users, and numbers of cases where the App has helped contact tracing efforts as a method of promoting adoption and ongoing use. People have indicated a clear willingness to help, but experience from other countries shows that such willingness does not always translate into action. Allowing the general public to see in real time the public health benefits of this App may help promote the App and maintain public interest.

Irish citizens surveyed are very familiar with Bluetooth technology and expressed a preference for Bluetooth-based App rather than a geolocation-based App. Given this, and the additional data protection concerns associated with geolocation data [37], the plans for the Irish App to use Bluetooth technology are likely to be more acceptable to the Irish public. However, messaging around privacy, data protection, and the role that the Google/Apple API plays in the App design will be important. Our results also suggest public health campaigns encouraging use of the App should focus on the key messages of the seriousness of COVID-19 disease and around the benefit to family, friends, and communities of reducing COVID-19 spread. How effective public health messaging will be in encouraging download and ongoing use of the App as the pandemic progresses remains to be seen.

Data from other countries suggest a significant response to contact tracing Apps by early adopters, followed by a swift plateauing in the population. In addition, as countries continue to reduce transmission and overall healthcare burden from COVID-19 effectively, general societal concern is likely to decline. However, with the considerable uncertainty that prevails with the COVID-19 pandemic and the likelihood of further outbreaks, it seems prudent for all countries to continue contact tracing App development and refinement.

The authors of this study will repeat this survey in September 2020, approximately 10 weeks after the Irish contact-tracing App has been launched.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Helen Ward and Dr. Christina Atchison and the research team in the Patient Experience Research Centre (PERC) of Imperial College London, School of Public Health, for the permission to use 5 questions from their survey instrument [17]. Imperial College London, in turn, thanks Prof. Samuel Yeung Shan Wong, Prof. Kin On Kwok, and Ms. Wan In Wei from JC School of Public Health and Primary Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China, for the permission to use their survey instrument and translating it into English (Kwok et al.).

Appendix 1

Authors’ contributions

MOC, LG, and JB conceived and designed this study, interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript, and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. MOC designed and deployed the final survey instrument. AS interpreted the data and provided statistical testing expertise and advice and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. DOK, JW, BN, and CS aided in the interpretation of the data and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All of the authors reviewed, discussed, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research work is supported by a funding grant from Science Foundation Ireland (13/RC/2094) and the COVIGILANT Science Foundation Ireland grant Project ID: 20/COV/0133.

Compliance with ethical standards

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this project was granted by the University of Limerick Education and Health Sciences (EHS) ethics committee [study ID 2020_04_18_EHS (ER)].

The University of Limerick EHS ethics committee is “charged by the University to consider the ethics of proposed research projects which will involve human subjects and to agree or not, as is the case, as to whether the projected research is ethical.” Approval was granted for our project on 21st May 2020.

Statement on participant consent

Participants were asked to tick a box on the online survey following the Survey Introduction (see first page of Appendix 1) to indicate their consent to participate in our research study. All responses were anonymous.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organisation (WHO). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report-44 (March 4, 2020). Available at https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200304-sitrep-44-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=93937f92_6 (accessed March 5, 2020)

- 2.National Health Library and Knowledge Service Evidence Team, Health Service Executive (HSE), Ireland. Mar 2020. Rapid evidence review: Covid-19 contact tracing. Lenus, the Irish Health Repository Mar 2020. Available at: https://www.lenus.ie/handle/10147/627288 (accessed 07/06/20)

- 3.Health Information and Quality Authority (HIQA), Ireland. Evidence summary for asymptomatic transmission of COVID-19. Apr 2020. Available at: https://www.hiqa.ie/sites/default/files/2020-04/Evidence-summary-for-asymptomatic-transmission-of-COVID-19.pdf (accessed 07/06/20)

- 4.Gandhi M, Yokoe DS, Havlir DV (2020) Asymptomatic transmission, the Achilles’ heel of current strategies to control Covid-19. N Engl J Med. Editorial. Available at: https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMe2009758 (accessed 07/06/20) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Contact tracing for COVID-19: current evidence, options for scale-up and an assessment of resources needed. Apr 2020. Available https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/COVID-19-Contract-tracing-scale-up.pdf (accessed 07/06/20)

- 6.Bengio Y, Janda R, Yu YW et al (2020) The need for privacy with public digital contact tracing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Digit Health 0(0) Available at https://www.thelancet.com/journals/landig/article/PIIS2589-7500(20)30133-3/fulltext (accessed 07/06/20) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Nature- Editorial 580, 563 Apr 2020. Show evidence that apps for COVID-19 contact-tracing are secure and effective. Available at https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-01264-1 (accessed 07/06/20) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Hinch R, Probert W, Nurtay A et al. Effective configurations of a digital contact tracing App: a report to NHSX Available at https://045.medsci.ox.ac.uk/files/files/report-effective-app-configurations.pdf (accessed 07/06/20)

- 9.Bay J, Kek J, Tan A et al BlueTrace: a privacy-preserving protocol for community-driven contact tracing across borders government technology agency, Singapore. Available at https://bluetrace.io/static/bluetrace_whitepaper-938063656596c104632def383eb33b3c.pdf (accessed 07/06/20)

- 10.World Health Organization (WHO). Contact tracing in the context of COVID-19: interim guidance, 10 May 2020. Available at https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/332049 (accessed 07/06/20)

- 11.European Commission website. Coronavirus: a common approach for safe and efficient mobile tracing apps across the EU European Commission - Questions and Answers. May 2020. Available at https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_20_869 (accessed 07/06/20)

- 12.Google. Exposure Notifications: using technology to help public health authorities fight COVID-19. Available at https://www.google.com/covid19/exposurenotifications/ (accessed 07/06/20)

- 13.Apple. Privacy-preserving contact tracing. Available at https://www.apple.com/covid19/contacttracing (accessed 07/06/20)

- 14.Department of Health (DOH), Ireland. National App for COVID-19. Available at https://www.gov.ie/en/news/d2a00d-national-app-for-covid-19/ (accessed 07/06/20)

- 15.Peeri NC, Shrestha N, Rahman MS et al (2020) The SARS, MERS and novel coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemics, the newest and biggest global health threats: what lessons have we learned? Int J Epidemiol. Available at https://academic.oup.com/ije/advance-article/doi/10.1093/ije/dyaa033/5748175 (accessed 07/06/20) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Qualtrics Core XM Survey Software. Qualtrics (2020) Provo, Utah, USA. Available at https://www.qualtrics.com/uk/core-xm/survey-software/ (accessed 20/06/20)

- 17.Ward H, Atchison C. Public response to UK government recommendations on COVID-19: population survey, 17–18 March 2020 Patient Experience Research Centre (PERC) of Imperial College London, School of Public Health

- 18.Abeler J, Altmann S, Milsom L et al Support in the UK for app-based contact tracing of COVID-19. Report from 14th April 2020. Department of Economics, University of Oxford. Available at https://osf.io/3k57r/ (accessed 18/06/20)

- 19.R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available at https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed 18/06/20)

- 20.Central Statistics Office (CSO), Ireland. Census of Population 2016 – Profile 10 Education, Skills and the Irish Language Available at https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-cp10esil/p10esil/le/ (accessed 10/06/20)

- 21.Healthy Ireland Summary report 2019 Department of health, Ireland. 2020. Available at https://assets.gov.ie/41141/e5d6fea3a59a4720b081893e11fe299e.pdf (accessed 10/06/20)

- 22.Global Mobile Consumer Survey 2019: The Irish cut Deloitte Ireland 2019. Available at https://www2.deloitte.com/ie/en/pages/technology-media-and-telecommunications/articles/global-mobile-consumer-survey.html (accessed 10/06/20)

- 23.Wright KB. Researching internet-based populations: advantages and disadvantages of online survey research, online questionnaire authoring software packages, and web survey services. J Comput Mediated Commun. 2005;10(3):JCMC1034. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bracken CC, Jeffres LW, Neuendorf KA, Atkin D. Parameter estimation validity and relationship robustness: a comparison of telephone and internet survey techniques. J Telematics Inform. 2009;26(2):144–155. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2008.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.European Data Protection Board (2020) Statement on the processing of personal data in the context of the COVID-19 outbreak. Available at https://edpb.europa.eu/sites/edpb/files/files/news/edpb_statement_2020_processingpersonaldataandcovid-19_en.pdf (accessed 10/06/20)

- 26.Dixon H. Fears grow over contact tracing app’s security and privacy The Telegraph. 5th May 2020. Available at https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2020/05/05/fears-grow-contact-tracing-apps-security-privacy/ (accessed 17/9/20)

- 27.Farries E. Covid-tracing app may be ineffective and invasive of privacy The Irish Times. 5th May 2020. Available at https://www.irishtimes.com/opinion/covid-tracing-app-may-be-ineffective-and-invasive-of-privacy-1.4244638 (accessed 17/9/20)

- 28.Stokel-Walker C Can mobile contact-tracing apps help lift lockdown? British Broadcasting Corporation. 16th April 20. Available at https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200415-covid-19-could-bluetooth-contact-tracing-end-lockdown-early (accessed 17/9/20)

- 29.Milsom L, Abeler J, Altmann S et al (2020) Survey of acceptability of app-based contact tracing in the UK, US, France, Germany and Italy, Open Science Foundation (OSF) Website. Available at https://osf.io/7vgq9/wiki/home/ (accessed 07/06/20)

- 30.Trace Together Website. Ministry of Health, Singapore. Available at https://www.tracetogether.gov.sg/ (accessed 07/06/20)

- 31.A Representative Sample of Australian Participants’s attitudes towards government tracing during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Dennis S, Garrett P, White J, Little D, Perfors A, Kashima Y, Lewandowsky S. Complex Human Data Hub, School of Psychological Sciences, The University of Melbourne. Available at https://paulgarrettphd.github.io/Site/Wave2Final.html (accessed 07/06/20)

- 32.A Representative Sample of Australian Participant’s Attitudes Towards the COVIDSafe App. Garrett P, White J, Little D, Perfors A, Kashima Y, Lewandowsky S, Dennis S. Complex Human Data Hub, School of Psychological Sciences, The University of Melbourne. Available at https://paulgarrettphd.github.io/Site/Wave3PrelimAnalysis.html (accessed 07/06/20)

- 33.Meixner S. How many people have downloaded the COVIDSafe app and how central has it been to Australia’s coronavirus response? ABC News Australia. Available at https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-06-02/coronavirus-covid19-covidsafe-app-how-many-downloads-greg-hunt/12295130 (accessed 10/06/20)

- 34.The Rakning C-19 tracing app website. The Directorate of Health, Iceland. Available at https://www.covid.is/app/en (accessed 10/06/20)

- 35.Findlay S, Palma S, Milne R (2020) Coronavirus contact-tracing apps struggle to make an impact The Financial Times online edition. Available at https://www.ft.com/content/21e438a6-32f2-43b9-b843-61b819a427aa (accessed 10/06/20)

- 36.Phartiyal S. India follows China’s lead to widen use of coronavirus tracing app Reuters News Agency. 14th May 2020. Available at https://www.reuters.com/article/health-coronavirus-india-app/india-follows-chinas-lead-to-widen-use-of-coronavirus-tracing-app-idUSL4N2CV4JL (accessed 18/06/20)

- 37.Principles for legislators on the implementation of new technologies. Irish Council for Civil Liberties (ICCL). June 2020. Available at https://www.iccl.ie/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Principles-for-legislators-on-the-implementation-of-new-technologies.pdf (accessed 10/06/20)