Abstract

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a motor neuron disease, typically resulting from loss-of-function mutations in the survival motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene. Nusinersen/SPINRAZA, a splice-switching oligonucleotide that modulates SMN2 (a paralog of SMN1) splicing and consequently increases SMN protein levels, has a therapeutic effect for SMA. Previously reported small-molecule SMN2 splicing modulators such as risdiplam/EVRYSDI and its analog SMN-C3 modulate not only the splicing of SMN2 but also that of secondary splice targets, including forkhead box protein M1 (FOXM1). Through screening SMA patient-derived fibroblasts, a novel small molecule, designated TEC-1, was identified that selectively modulates SMN2 splicing over three secondary splice targets. TEC-1 did not strongly affect the splicing of FOXM1, and unlike risdiplam, did not induce micronucleus formation. In addition, TEC-1 showed higher selectively on galactosylceramidase and huntingtin gene expression compared to previously reported compounds (e.g., SMN-C3) due to off-target effects on cryptic exon inclusion and nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. Moreover, TEC-1 significantly ameliorated the disease phenotype in an SMA murine model in vivo. Thus, TEC-1 may have promising therapeutic potential for SMA, and our study demonstrates the feasibility of RNA-targeting small-molecule drug development with an improved tolerability profile.

Subject terms: Drug discovery, Diseases

Introduction

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a neurodegenerative disorder in which there is a loss of lower motor neurons (MNs) that project from the spinal cord and the brain stem. This leads to muscle atrophy and difficulties in breathing and walking, which may require tracheotomy and artificial respiration assistance.

SMA is typically inherited as an autosomal recessive trait, with most patients having loss-of-function mutations in the survival motor neuron 1 (SMN1) gene. The SMN2 gene, a paralog of SMN1, differs from SMN1 at only 2 base pairs in the open reading frame, but the amino acid sequences encoded by the two genes are identical. One of the base pair differences causes a translationally silent, single-nucleotide transition in SMN2 at position 6 of exon 7 (c6t), which not only disrupts binding sites for positive splicing regulators1 but also creates binding sites for negative splicing regulators2. In addition, this change (c6t) strengthens an extended inhibitory context3,4. As a result, most of the mRNA transcribed from the SMN2 gene is of the Δ7 form, which skips exon 7 via splicing. However, the full-length SMN2 mRNA containing exon 7 (FL-SMN2) is also produced at a rate of 5–10% of the total transcripts. An increase in the copy number of the SMN2 gene ameliorates the severity of SMA, and loss and compensation strongly correlate with the onset and progression of the disease5; hence, in recent years, SMN2 has become an attractive target of drug development.

Nusinersen/ASO10-27/SPINRAZA, an approved antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) drug for the treatment of SMA, directly targets intronic splicing silencer N1 (ISS-N1) in intron 7 of SMN26,7, which modulates SMN2 splicing, and leads to an increase in SMN protein levels8. According to a Phase III trial (ENDEAR), nusinersen showed moderate therapeutic effects with delayed disease progression and ventilation timing9, but was unable to penetrate the blood–brain barrier (BBB). However, nusinersen treatment requires repeated intrathecal administration, and is associated with several side effects, including post-lumbar puncture syndrome characterized by back pain, headache, and fever, and the production of neutralizing antibodies (NAb), raising concerns associated with its clinical use10. Furthermore, an advanced medical procedure to treat SMA patients with scoliosis is under development, as patients with complex spinal anatomies and respiratory insufficiency are unable to receive intrathecal injections11. AVXS-101/ZOLGENSMA is an approved gene therapy using an adeno-associated virus serotype 9 (AAV9) to deliver a functional copy of the SMN gene to MNs in patients with SMA. Compared with nusinersen, clinical trials of AVXS-101 have shown that it improves survival; thus, AVXS-101 is currently regarded as the most promising drug available, provided that the first dose is administered by approximately 7 months of age9,12. However, there are some disadvantages of AVXS-101, such as requiring intravenous administration, and checking the presence of NAb prior to infusion12. In addition, ASO drugs and gene therapies are generally expensive; the costs of nusinersen for 10 years and a single treatment with AVXS-101 in the United States are approximately $4.1 and $2.1 million, respectively, which imposes an additional burden on the patients.

RG7916/risdiplam/EVRYSDI, an approved orally administered small-molecule SMN2 splicing modulator, was developed by Roche13,14. Risdiplam analogs (hereafter referred to as the SMN-C series) were identified using a cell-based screening system, in which a luciferase reporter protein was expressed only when exon 7 of the SMN2 minigene containing exons 6 to 8 was included after splicing15. Each of the SMN-C series included exon 7 in the SMN2 transcript and concomitantly increased the level of FL-SMN protein in SMA patient-derived cells15. Optimization studies in a murine model of SMA and in non-rodent models were performed, resulting in the identification of risdiplam16. In the interim analysis of Phase II/III (FIREFISH), risdiplam showed equivalent activity to AVXS-101 in rescuing the motor function delays in patients with SMA type I12,13. However, risdiplam induced micronucleus formation in preclinical studies in vitro and in vivo, indicating that it is a potential carcinogen16. Aberrant splicing of forkhead box protein M1 (FOXM1) is thought to be responsible for this micronucleus induction16. In addition, RNA sequencing analyses revealed that the SMN-C series decreases the expression levels of galactosylceramidase (GALC)15,17, which metabolizes the toxic glycolipid psychosine in lysosomes18, and huntingtin (HTT)15,17, which is essential for pancreatic and brain function19. Thus, orally administered small-molecule drugs with a limited effect on splicing targets other than SMN2 (i.e., secondary splice targets) would be the best drugs to ensure clinical tolerability.

Small-molecule compounds offer many advantages for systemic delivery, including access to the brain, heart, and skin; non-invasive (oral) administration; avoidance of NAb; and lower manufacturing costs compared to ASO and gene therapy. We identified a SMN2 splicing small-molecule modulator, termed TEC-1 (2-(4,6-dimethylpyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrazin-2-yl)-6-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one)20, that shows promise as a clinical candidate for the tolerable long-term treatment of SMA. This report describes the preclinical characterization and prospects of TEC-1.

Results

TEC-1 increases the expression level of FL-SMN2 mRNA and decreases the expression level of Δ7 mRNA

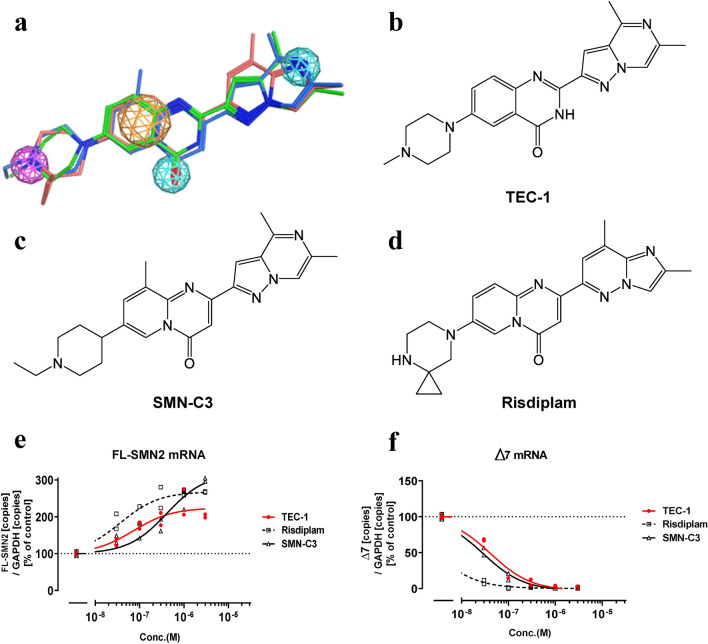

To identify splicing modulators with improved selectivity for SMN2, over 300 compounds were designed from our compound collection and evaluated, optimized using SMA patient-derived fibroblasts20. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was then used to evaluate the splicing activity of these candidates against SMN2 and secondary splice targets (e.g., FOXM1). Subsequently, a single oral dose was administered to FVB mice to assess bioavailability and brain penetration. As a result of these screens, we identified a compound, TEC-1, which increased the form of SMN2 that includes exon 7 (FL-SMN2), and decreased the form that skips exon 7 (Δ7) in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1a,b,e,f). These results led us to conclude that TEC-1 is an SMN2 splicing modulator. The SMN-C series (SMN-C3 and risdiplam) also modulated SMN2 splicing, with effects similar to those noted in previous reports15,16 (Fig. 1c–f).

Figure 1.

TEC-1 is structurally similar to SMN-C3 or risdiplam and modulates SMN2 splicing. (a) Pharmacophore model and alignment of TEC-1 (green), risdiplam (pink), and SMN-C3 (blue) with MOE2018.01. Pharmacophore annotation: Aromatic and other pi-system rings (orange), H-bond donor heavy atom (magenta), H-bond acceptor heavy atom (pale blue). (b) Structure of TEC-1. (c) Structure of SMN-C3. (d) Structure of risdiplam. (e) qPCR analysis of FL-SMN2 transcripts in SMA type II fibroblasts (GM03813) exposed to each compound for 24 h. The amounts of mRNA were normalized to those of GAPDH. (f) qPCR analysis of Δ7 transcripts of GM03813 cells exposed to each compound for 24 h. The amounts of mRNA were normalized to those of GAPDH. Data are from two biologically independent samples in e, f. a-d were derived by by Axcelead Drug Discovery Partners, Inc.

TEC-1 does not strongly affect FOXM1 splicing

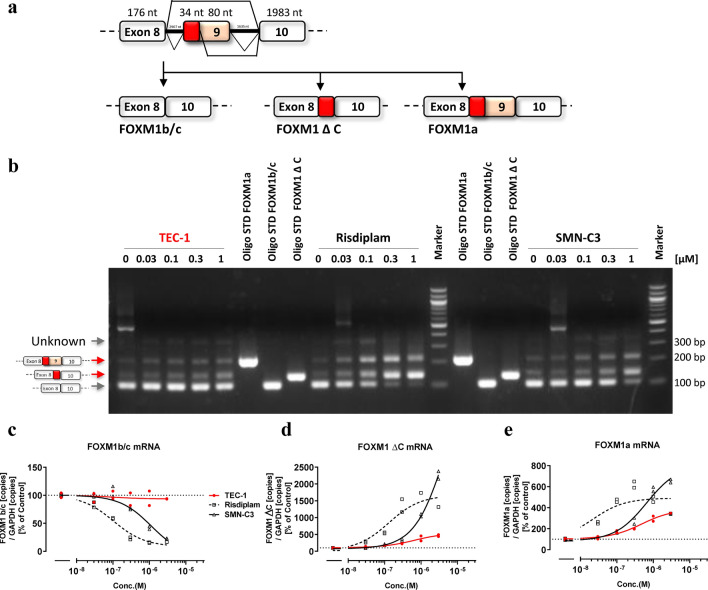

FOXM1 is a protein involved in cell division, and reduced abundance of its major splicing isoform FOXM1b/c is observed in the G1/S phase, whereas an increase in this isoform is detected in the G2/M phase. Moreover, FOXM1 splicing contributes to chromosome missegregation and toxicity at the level of cell cycle/division21,22. Previous reports revealed that risdiplam induces micronucleation in vitro and in vivo16. We therefore evaluated changes in FOXM1 splicing variants that occurred under the influence of the SMN-C series by reverse transcription (RT)-PCR (Fig. 2a,b). In GM03813 fibroblasts treated with the SMN-C series, the level of the FOXM1b/c variant was decreased, while the levels of the FOXM1 ΔC and 1a variants were increased, suggesting that the SMN-C series modulates the splicing of FOXM1 (Fig. 2b–e). Interestingly, TEC-1 did not strongly affect the splicing of FOXM1 (Fig. 2b–e). To estimate the selectivity of splicing between SMN2 and FOXM1, we determined the EC1.5× value of SMN2, representing the concentration at which there is a 50% increase in total FL-SMN2 mRNA. Next, we calculated EC50 values of FOXM1b/c to determine the concentrations showing a 50% reduction in total FOXM1b/c mRNA levels. We then normalized EC50 of FOXM1b/c based on the EC1.5× value of FL-SMN2 (FOXM1b/FL-SMN2) and found that its value in the presence of TEC-1 was over 61 (Table 1 and Fig. 2c–e). By contrast, these values in the presence of SMN-C3 or risdiplam was 8 and 8, respectively, indicating that the SMN-C series strongly affects FOXM1 splicing compared with TEC-1 (Table 1 and Fig. 2c–e). We next examined whether TEC-1 induces chromosomal damage using an in vitro micronucleus assay in human lymphoblasts (TK6 cells) under three treatment conditions (Table 2). In a 3-h treatment without S9 mix, followed by a 21-h recovery period, 2.3 µg/mL (5.9 µM) TEC-1 caused a significant increase in the incidence of micronucleated cells. We confirmed that TEC-1 induces a concentration-dependent increase in the number of micronucleated cells. However, the relative population doubling (RPD) value at 2.3 µg/mL (5.9 µM) was 35.0%, suggesting that this positive response was secondary to cytotoxicity. In a 3-h treatment including S9 mix, followed by a 21-h recovery period, 2.7 µg/mL (6.9 µM) TEC-1 significantly increased the incidence of micronucleated cells. The RPD value at this concentration was 58.7%. However, in this condition, a concentration-dependent increase was not observed. In a 24-h treatment without S9 mix, there was no significant increase in the number of micronucleated cells at any TEC-1 concentration compared to the negative control group. We therefore concluded that TEC-1 and its metabolites in the liver do not induce micronucleation, indicating that no chromosomal damage occurs. Conversely, risdiplam induces micronucleation in vitro and in vivo16. In summary, these results suggest that avoiding FOXM1 splicing helps to prevent micronucleation.

Figure 2.

TEC-1 does not substantially affect FOXM1 splicing. (a) Schematic representation of exon construction and exon inclusion of FOXM1 mRNA splicing. (b) RT-PCR analysis of FOXM1 variants of GM03813 fibroblasts exposed to each compound for 24 h. RT-PCR products of FOXM1 variants were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized with ethidium bromide. Standard FOXM1 fragments corresponding to three isoforms (Oligo STD) are shown. Molecular weight markers are shown on the right (bp). The full-length gel is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1e. (c–e) qPCR analysis of each FOXM1 variant of GM03813 cells exposed to each compound for 24 h. The amounts of each variant were normalized to those of GAPDH. Data are from two biologically independent samples in (c–e).

Table 1.

Selectivity against various splicing targets.

| Comp | EC1.5× (nM) | EC50 (nM) | EC4.0× (nM) | EC3.0× (nM) | EC50 (nM) | EC50 (nM) | Selectivity | Selectivity | Selectivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FL-SMN2 | FOXM1b | FOXM1ΔC | FOXM1a | GALC | HTT | FOXM1b /FL-SMN2 |

GALC /FL-SMN2 |

HTT /FL-SMN2 |

|

| TEC-1 |

49.1 (22.7–109.4) |

> 3000.0 |

1311.6 (864.7–2285.8) |

1096.8 (809.7–1552.2) |

> 3000.0 | > 3000.0 | > 61 | > 61 | > 61 |

| Risdiplam |

15.8 (8.81–32.8) |

123.5 (93.2–160.4) |

38.9 (6.98–85.0) |

24.2 (4.49–78.5) |

N.T. | N.T. | 8 | N.T. | N.T. |

| SMN-C3 |

122.1 (74.5–221.7) |

945.2 (620.0–1349.0) |

298.5 (248.8–355.8) |

280.3 (211.4–377.7) |

459.4 (315.7–645.5) |

547.2 (373.6–771.3) |

8 | 4 | 4 |

The EC values were calculated for a 6-point titration curve using nonlinear regression with Graphpad Prism for compounds whose curves are shown in Figs. 1, 2, 3, or 4. GM03813 fibroblasts were exposed to each compound for 24 h. The amounts of each target mRNA were normalized to those of GAPDH. An EC1.5×, 4.0× or 3.0× value shows 50%, 300%, or 200% total target mRNA increase. An EC50 value of the target shows 50% total target mRNA reduction. The 95% confidence intervals are listed in brackets. To estimate selectivity, each EC value was divided with EC1.5× of FL-SMN2. N.T. indicates Not Tested.

Table 2.

TEC-1 did not induce micronucleus formation in TK9 cells with or without a rat liver microsome fraction (S9).

| Group | Test article | Concentration µg/mL |

Treatment conditions | Relative population doubling (%) | Micronucleated cells | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well 1 | Well 2 | Total | (%) | |||||

| 1 | DMSO | 10 μL/mL | 3 h -S9 mix | 100 | 13 | 13 | 26 | (0.65) |

| 2 | TEC-1 | 1.9 (4.9 µM) | 68.6 | 13 | 16 | 29 | (0.73) | |

| 3 | 2.1 (5.4 µM) | 65.4 | 16 | 20 | 36 | (0.9) | ||

| 4 | 2.3 (5.9 µM) | 35.0 | 29 | 27 | 56 | (1.4) **,## | ||

| 5 | MMC | 0.1 (0.3 µM) | N.D. | 59 | 59 | 118 | (2.95) ** | |

| 6 | DMSO | 10 μL/mL | 3 h + S9 mix | 100 | 10 | 14 | 24 | (0.6) |

| 7 | TEC-1 | 2.5 (6.4 µM) | 76.4 | 18 | 15 | 33 | (0.83) | |

| 8 | 2.7 (6.9 µM) | 58.7 | 24 | 21 | 45 | (1.13) ** | ||

| 9 | 2.9 (7.4 µM) | 46.8 | 17 | 13 | 30 | (0.75) | ||

| 10 | CP | 6 (21 µM) | N.D. | 39 | 46 | 85 | (2.13) ** | |

| 11 | DMSO | 10 μL/mL | 24 h -S9 mix | 100 | 18 | 12 | 30 | (0.75) |

| 12 | TEC-1 | 1.1 (2.8 µM) | 81.7 | 21 | 13 | 34 | (0.85) | |

| 13 | 1.3 (3.3 µM) | 74.4 | 17 | 12 | 29 | (0.73) | ||

| 14 | 1.5 (3.9 µM) | 69.5 | 17 | 15 | 32 | (0.8) | ||

| 15 | COL | 0.01 (0.03 µM) | N.D. | 45 | 51 | 96 | (2.4) ** | |

Experiments were performed under the following three treatment conditions. 1: short-term treatment for 3 h without S9 mix, followed by a 21-h culture (3 h −S9 mix, shown in groups 1–5), 2: short-term treatment for 3 h with S9 mix, followed by 21-h culture (3 h + S9 mix, shown in groups 6–10), 3: continuous treatment for 24 h without S9 mix (24 h −S9 mix, shown in group 11–15). Mitomycin (MMC) for 3 h −S9 mix, cyclophosphamide (CP) for 3 h + S9 mix, and colcemid (COL) for 24 h −S9 mix were used as positive controls. These articles have been recommended for use in the OECD test guideline (Test No. 487)49. DMSO was served as negative control. The numbers of micronucleated cells were counted in 4000 cells and percentages of micronucleated cells were calculated for statistical analyses. ## < 0.01 as assessed by Cochran-Armitage test for dose-relationship. **p < 0.01 as assessed by Fisher’s exact test using negative control-treated cells. N.D. indicates Not Determined.

The FOXM1 sequence in cynomolgus monkeys is nearly identical to that in humans, with only a single mismatch in the sequence between exon 9 and the donor site (Supplementary Fig. 1a, yellow highlight). Notably, FOXM1 mis-splicing was similarly observed in cynomolgus monkey cells (NCMDF) exposed to risdiplam (Supplementary Fig. 1b–d), for which the toxicology is discussed below.

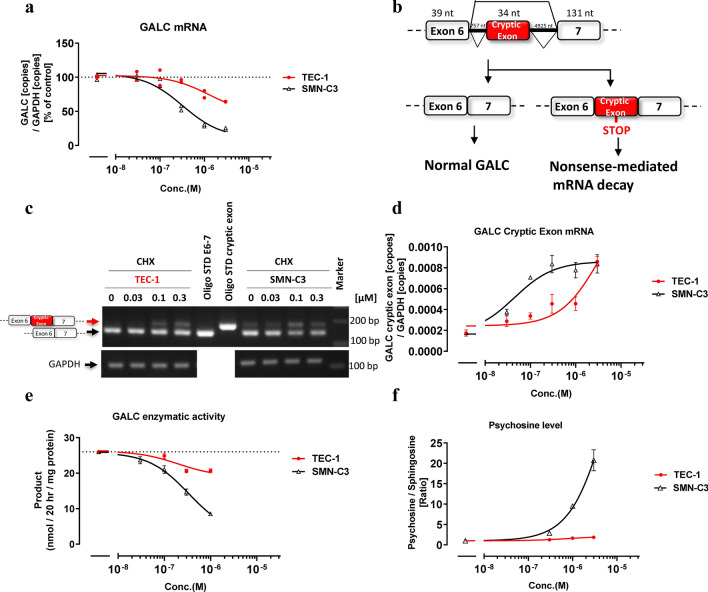

TEC-1 only slightly modulated GALC splicing

SMN depletion was reported to reduce the total amount of GALC mRNA in mouse MNs23. The SMN-C series, which increases the amount of SMN protein, unexpectedly decreased the total amount of GALC mRNA in RNA sequencing studies of SMA patient-derived fibroblasts15,17. We speculated that this reduced GALC expression is caused by the effects of the SMN-C series on secondary splice targets, rather than by an effect mediated by the SMN protein itself. To test this possibility, we evaluated the ability of SMN-C3 or TEC-1 to change the expression of GALC mRNA. SMN-C3 strongly reduced the GALC mRNA level compared to TEC-1 (Fig. 3a). The EC50 values of GALC, which reflects a 50% reduction in total GALC mRNA, normalized to the EC1.5×value of FL-SMN2 (GALC/FL-SMN2) was over 61 for TEC-1, whereas that of SMN-C3 was 4, suggesting that TEC-1 is a more selective SMN2 splicing modulator compared with the SMN-C series (Table 1, Fig. 3a). To investigate the mechanism of action for the reduction in GALC mRNA expression induced by the SMN-C series, we assessed whether the decrease in GALC mRNA by SMN-C3 is affected by cycloheximide (CHX), which suppresses nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD). The GALC mRNA reduction was rescued by CHX exposure (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Direct sequencing of RT-PCR products revealed that a 34 nucleotide (nt) sequence derived from intron 6 was inserted between exons 6 and 7 (Supplementary Fig. 2b cryptic exon start, Fig. 3b). Thus, we confirmed a previously unreported 34 nt cryptic exon by RT-PCR and qPCR, the inclusion of which was more significantly induced by SMN-C3 than by TEC-1 (Fig. 3c,d). This cryptic exon inclusion in GALC causes NMD since an in-frame TAG codon (premature termination codon) exists 12 nt from the 5ʹ-terminus of the cryptic exon (22 nt from the 3ʹ end of the cryptic exon) (Supplementary Fig. 3a, highlighted green). Thus, we conclude that the SMN-C series promotes inclusion of this abnormal 34 nt cryptic exon, which contributes to the reduction in total GALC mRNA expression.

Figure 3.

TEC-1 does not strongly impact GALC cryptic splicing. (a) qPCR analysis of GALC transcripts in GM03813 cells treated with each compound for 24 h. The amounts of GALC mRNA were normalized to those of GAPDH. (b) Schematic representation of exon construction and cryptic exon inclusion of GALC mRNA splicing. (c) RT-PCR analysis of GALC transcripts in GM03813 cells treated for 6 h with both compounds and CHX. RT-PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized with ethidium bromide. Standard GALC fragments (Oligo STD) with or without the cryptic exon are shown. Molecular weight markers are shown on the right (bp). The full-length gel is presented in Supplementary Fig. 2c. (d) qPCR analysis of the GALC cryptic exon in GM03813 cells treated for 6 h with both compounds and CHX. Aberrant GALC mRNA amounts with cryptic exons were quantified and normalized to those of GAPDH. (e) GALC enzymatic assay from human oligodendroglioma (Hs683) cells treated with each compound for 3 days. The amounts of standardized product (fluorogenic HMU-β-D galactopyranoside) were normalized to those of total protein. (f) Ratio of psychosine and sphingosine in Hs683 cells treated with each compound for 12 days. The amounts of psychosine were determined by LC/MS/MS whose signal was normalized by sphingosine signals. Data are from two biologically independent samples in (a). Data in (d), (e), (f) represent means ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of three independent assessments per concentration.

Notably, reductions in GALC by the SMN-C series were not observed in cells derived from dogs and rats, whose genomes lack the long intronic region that includes the 34 nt sequence (Supplementary Fig. 3a, d, e). However, the reduction in GALC caused by the SMN-C series in cynomolgus monkey cells was stronger than that in green monkey cells (Supplementary Fig. 3a–c). This difference is likely related to the number of mismatched sequences near the cryptic exon and donor site (Supplementary Fig. 3a–c). Furthermore, the sequences of the human GALC cryptic exon and human FOXM1 exon 9/A2 are quite similar (only 3 mismatches in the included exon and donor site, Supplementary Fig. 11, highlighted yellow). These results suggest that sequence similarity contributes to the inclusion of the GALC cryptic exon by the SMN-C series.

GALC encodes a lysosomal enzyme that degrades psychosine, a highly toxic glycolipid18. Mutations in GALC underlie Krabbe disease, an autosomal recessive disorder in which psychosine accumulates in the brain. To test whether reduced GALC mRNA impacts GALC enzymatic function, the activity of GALC protein was measured. Expression of UDP glycosyltransferase 8 (UGT8), a key enzyme for the production of psychosine, is low in the skin24. Since UGT8 expression is high in oligodendrocytes25, its glioma cell line Hs683 was utilized for this assay. SMN-C3 strongly decreased the activity of GALC compared to TEC-1, similar to its effects on GALC mRNA expression (Fig. 3a,e). TEC-1, even at a concentration of 3000 nM, induced a slight decrease in GALC enzymatic activity, and caused only a 1.9-fold increase in psychosine compared to the control (Fig. 3e,f). Notably, a 1.9-fold increase in psychosine is tolerable, as heterozygous carriers of Krabbe disease have an approximately 1.8-fold increase in plasma psychosine compared with unaffected controls18. By contrast, 3000 nM SMN-C3 triggered an approximately 22-fold increase in psychosine (Fig. 3f), which is greater than the approximately 15-fold increase in plasma psychosine reported in early-infantile-onset Krabbe disease18.

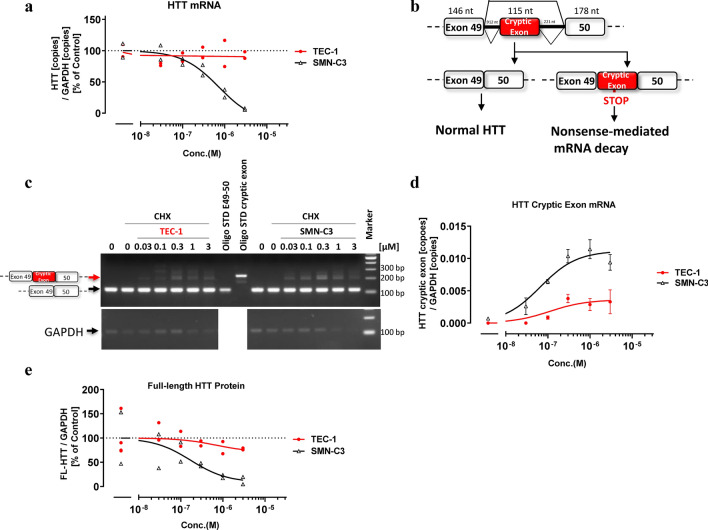

TEC-1 does not induce abnormal HTT splicing

Knockdown of the HTT gene in young mice was reported to cause acute pancreatitis19. Previous RNA sequencing studies have reported that the SMN-C series reduces total HTT mRNA15,17, which we confirmed in the present study using qPCR (Fig. 4a). However, SMN depletion does not alter the level of HTT mRNA in mouse MNs23, suggesting that HTT reduction by the SMN-C series is caused by secondary splice target effects. To elucidate the mechanism by which HTT is reduced, RT-PCR products from cells cultured with both risdiplam and CHX were sequenced. In the presence of risdiplam with CHX, the HTT mRNA included a previously unreported 115 nt derived from part of intron 49, just after the end of exon 49 (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 4b), which we also confirmed by RT-PCR and qPCR (Fig. 4c,d). As in the case with the GALC splicing isoforms, an in-frame TAG codon (premature termination codon) was present 58 nt upstream from the 3ʹ end of the cryptic exon (57 nt from the 5ʹ end) (Supplementary Fig. 5a, highlighted green). These results suggest that the HTT mRNA with the cryptic exon was also degraded via NMD. Importantly, TEC-1 did not substantially impact the inclusion of the HTT cryptic exon or reduction of HTT at the mRNA and full-length protein levels (Fig. 4a,d,e).

Figure 4.

TEC-1 does not strongly affect HTT cryptic splicing and protein abundance unlike SMN-C3. (a) qPCR analysis of HTT transcripts in GM03813 cells treated with each compound for 24 h. The amounts of HTT mRNA were normalized to those of GAPDH. (b) Schematic representation of exon construction and cryptic exon inclusion or exclusion of HTT mRNA splicing. (c) RT-PCR analysis of HTT transcripts in GM03813 cells treated for 6 h with compounds and CHX. RT-PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and visualized with ethidium bromide. Standard HTT fragments with or without the cryptic exon (Oligo STD) are shown. Molecular weight markers are shown on the right (bp). Full-length gels are presented in Supplementary Fig. 5b. (d) qPCR analysis of cryptic HTT transcripts of GM03813 cells treated for 6 h with compounds and CHX. The amounts of HTT with the cryptic exon were quantified and normalized to those of GAPDH. Values less than the quantitation limit were presumed to be 0. (e) Full-length (FL)-HTT protein levels of GM03813 fibroblasts treated with each compound for 3 days. Following western blot analyses, the signals of FL-HTT protein were analyzed and were normalized to those of GAPDH protein. Full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 4a. Data are from two or four biologically independent samples in (a), (e). Data in (d) represent means ± SEM of three independent assessments per concentration.

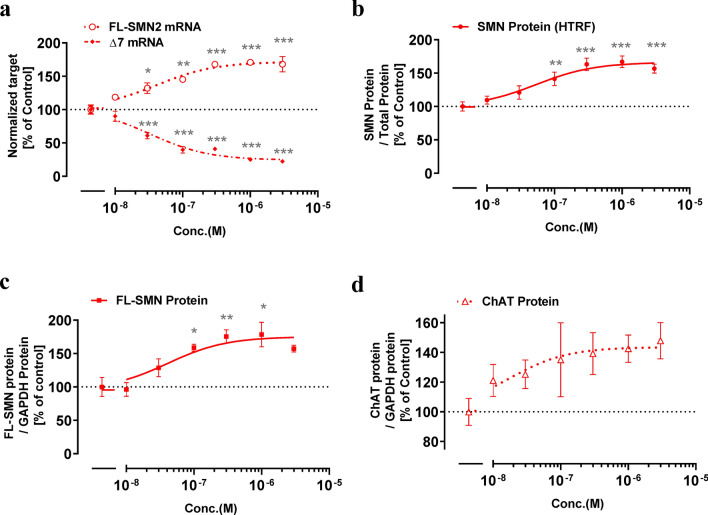

TEC-1 modulates SMN2 splicing and shows disease-modifying effects in induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived MNs of an SMA patient

To test whether TEC-1 impacts SMN2 splicing in MNs, we cultured MNs differentiated from iPSCs derived from a patient with SMA type II26. TEC-1 showed clear ability to modulate SMN2 splicing at a concentration of 30 nM, and increased SMA protein at a concentration of 100 nM (Fig. 5a–c). Consistent with previous results, we found that SMN-C3 modulates SMN2 splicing in our culture conditions15, with similar effects to those of TEC-1 (Supplementary Fig. 6). TEC-1 has also been shown to increase the levels of choline acetyltransferase (ChAT), which are decreased in MNs from patients with SMA compared to those of healthy subjects27 (Fig. 5d). These results suggest that TEC-1 can modulate SMN2 splicing in MNs, and is therefore a potential therapeutic drug.

Figure 5.

TEC-1 displays disease-modifying effects in motor neurons derived from SMA patient iPSCs (GM24468). (a) qPCR analysis of the SMN transcripts of motor neurons treated with TEC-1 for 24 h. The amounts of mRNA, including (FL-SMN2), and excluding (Δ7) exon 7, were normalized to those of GAPDH. (b) SMN protein levels in motor neurons treated with TEC-1 for 3 days. SMN protein in cell lysates was quantified with homogeneous time resolved fluorescence (HTRF) and normalized to total protein. (c) The level of FL-SMN protein. The SMN density in western blots was normalized to GAPDH density. Full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 10. (e) The levels of ChAT protein. The ChAT density in western blots was normalized to GAPDH density. Full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. 10. Data in (a–d) represent means ± SEM of three independent assessments per concentration. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 as assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test using DMSO-treated cells as a control (100%).

To ensure its therapeutic benefit to SMA patients in combination with nusinersen, it is important to know whether TEC-1 inhibits the activity of nusinersen. Low concentrations of TEC-1 did not inhibit the effects of nusinersen in SMA patient-derived fibroblasts, whereas at 1 and 3 µM, it significantly enhanced the effects of nusinersen (Supplementary Fig. 7).

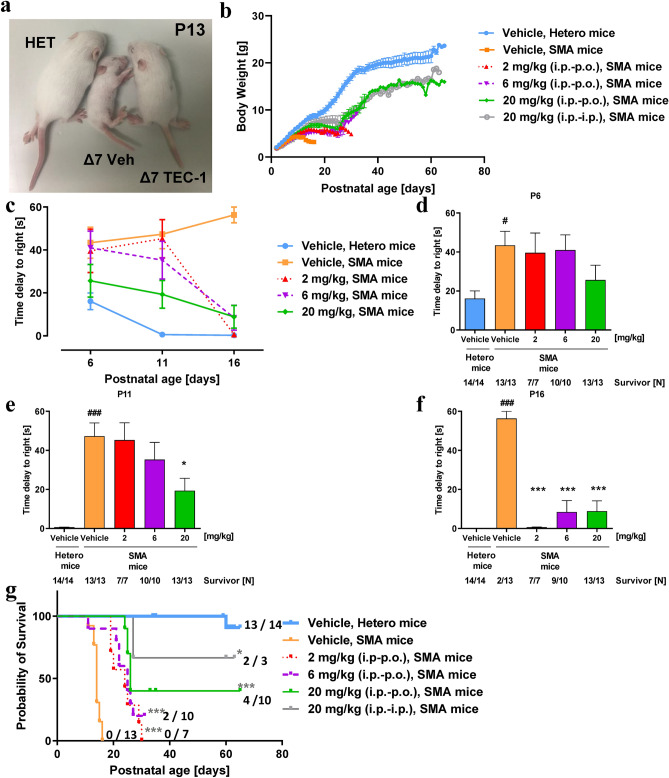

TEC-1 ameliorates the disease phenotype in a murine model of SMA

To examine whether TEC-1 alleviates the SMA phenotype, we evaluated the effects of TEC-1 on a murine model of SMA (SMNΔ7 mice), which show a severe disease phenotype28. First, we confirmed that orally administered TEC-1 could penetrate the BBB in adult wild-type FVB mice (Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Table 4). Next, since oral administration to neonatal SMNΔ7 mice increases the rate of unexpected mortality29, we intraperitoneally administered TEC-1 before weaning (P2 to P23). Intraperitoneally administered TEC-1 was absorbed, excreted, and crossed the BBB in juvenile wild-type FVB mice (Supplementary Fig. 9 and Supplementary Table 5). SMNΔ7 mice were then treated with 2, 6, and 20 mg/kg TEC-1 once a day by intraperitoneal injection from P2 to P23. After P23, the route of administration was changed to oral administration, since oral drug development is the ultimate objective. SMNΔ7 mice treated with TEC-1 showed an increased body mass compared to that of vehicle-treated SMNΔ7 mice (Fig. 6a,b). To examine the effect of TEC-1 on motor function in SMNΔ7 mice, a righting reflex test was performed at P6, P11, and P16. Latency to righting in vehicle-treated SMNΔ7 mice was prolonged compared to that of control heterozygous mice. However, SMNΔ7 mice treated with 2 mg/kg TEC-1 showed a significantly shortened latency time compared to that of vehicle-treated mice at P16 (Fig. 6c–f). Importantly, TEC-1 enhanced the survival of SMNΔ7 mice compared with that of vehicle-treated SMNΔ7 mice (Fig. 6g). Taken together, TEC-1 has potential to ameliorate SMA phenotypes, improving both survival and motor function.

Figure 6.

TEC-1 rescues the phenotype in a murine model of SMA. (a) Appearance of a vehicle-treated SMA mouse model, a 20 mg/kg TEC-1-treated SMA mouse model, and a vehicle-treated heterozygous mouse (HET) at P13. The murine model of SMA was treated from P2 to P23 once daily with vehicle or TEC-1 by intraperitoneal administration (i.p.) at 2, 6, or 20 mg/kg, and thereafter once daily by oral administration (p.o.) or i.p. with 2, 6, or 20 mg/kg. (b) Body weight from P2 through P65. (c–f) Righting reflex of SMA mice. The mean time for mice to right themselves after being put onto their backs, assessed at P6, P11, and P16, total duration. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 and ###p < 0.001 (vs. HET/Hetero, vehicle) as assessed by Student’s t-test (unpaired, two-tailed). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001 as assessed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test using vehicle-treated SMA mice as a control. Individuals who died had a value of 60 s (maximum). The number of mice (N) is shown in the graph. (g) Kaplan–Meier survival curves from birth to P65. Numbers at the right indicate survivors at P65 mice per group. The log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test and Bonferroni test were used for comparisons. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (vs. vehicle [KO]). The survivor or total input number of mice is graphed.

Discussion

TEC-1 was identified and optimized using a cell-based screening system with fibroblasts from a patient with SMA, in contrast to the previous use of a cell-based assay using an SMN2 minigene reporter, which led to the identification of the SMN-C series15 and the NVS-SM series30. To improve the clinical tolerability, we simultaneously evaluated the splicing of SMN2 and secondary splice targets (e.g., FOXM1) in SMA patient-derived fibroblasts, which maintain the intrinsic structure of cellular mRNAs. Our approach confirmed that TEC-1 has improved selectivity toward SMN2 splicing over three representative secondary splice targets. The characterization of the molecular target or binding site of TEC-1 is beyond the scope of this study. Previous reports revealed that the SMN-C series and NVS-SM series directly interact with the major groove of the RNA duplex generated by the 5ʹ splicing site of exon 7 and U1 snRNA17. Furthermore, the SMN-C series also binds to purine-rich regions within exon 7, and this interaction is proposed to be affected by several RNA-binding protein factors17,31,32. Thus, multiple interactions of RNA structure and compounds contribute to selective SMN2 splicing by the SMN-C series. Further research is required to reveal that TEC-1, which has a similar pharmacophore to the SMN-C series (Fig. 1), interacts in the same manner and strongly and/or selectively binds to SMN2 over the three secondary splice targets compared with the SMN-C series. Secondary splice target effects may lead to a high risk of toxicity in vivo. Indeed, in a 39-week toxicological study of cynomolgus monkeys treated with risdiplam, pathological intestinal and pancreatic changes, and irreversible retinal degeneration were observed16. Ratni et al.16 hypothesized that FOXM1 may be the most important target contributing to these toxicities, although the involvement of other secondary splice targets such as STRN3, APLP2, and MADD remains unclear. Our in vitro analysis of cynomolgus monkey cells also suggested that aberrant splicing of FOXM1 contributes to the toxicity in risdiplam-treated cynomolgus monkeys (Supplementary Fig. 1). To further characterize the selectivity of splicing by TEC-1, in future studies, we plan to investigate not only these secondary splice targets (STRN3, APLP2, and MADD) but also other unexpected targets using RNA sequencing and qPCR. Roche/PTC, when developing risdiplam, had set an exposure cap in a Phase I clinical trial with its concentration showing an area under the curve (AUC)0–24h value of 1500 ng·h/mL in plasma (18 mg/individual)14. Risdiplam administered under this exposure cap showed a comparable clinical effect to AVXS-101 in motor function assessments. Only about half of the patients achieved a clinical readout, which was the ability to sit unsupported for several seconds (5 or 30 s) during interim analysis12,13. Therefore, there is still room to improve motor function delays. Based on these reports and our results, we believe that risdiplam was being tested at lower doses in clinical trials to avoid toxic effects such as FOXM1 or GALC splicing and micronucleus induction16. Risdiplam aberrantly included FOXM1 exon 9, whose nucleotide sequence is similar to an unreported GALC cryptic exon (Supplementary Fig. 11, highlighted yellow). We hypothesize that the secondary splice target effects of the SMN-C series stem from these conserved nucleotide sequences of RNA. By contrast, TEC-1 showed relatively higher selectivity against FOXM1, GALC, or HTT. Our screening strategy with cells which maintain the intrinsic structure of cellular mRNAs further proved the validity of excluding toxic cryptic exons in specific secondary splice targets, enabling the identification of small-molecule SMN2 splicing modulators with a more tolerable clinical profile.

The biological activity of 106 representative proteins that are drug discovery targets was investigated with a selectivity-panel from Eurofins Inc. TEC-1 weakly affected the biological activity of only two targets, human acetylcholinesterase and rat N type calcium channel, with IC50 values of 1.19 μM and 8.80 μM, respectively. TEC-1 is therefore an effective and safe drug since the EC1.5× value of FL-SMN2 (49.1 nM) is markedly lower than the two aforementioned IC50 values. Furthermore, TEC-1 showed good profiles with general in vitro toxicity and adsorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) tests (items: solubility, PAMPA/membrane permeability; MDR1/BBB penetration, stability; CYP inhibition, CYP induction; PXR, hERG, cytotoxicity/liver toxicity, umu/mutagenicity, Ames/mutagenicity, in vitro micronucleus test/tumorigenesis). It should be noted that TEC-1 did not induce micronucleus formation in human cells in vitro, in contrast to risdiplam. Collectively, our findings demonstrate that TEC-1 is a key member of a class of compounds with a low risk of acute and chronic side effects for SMA treatment.

Cardiac abnormalities33,34, pancreatic defects35,36, and liver deficits37,38 have been reported in patients with SMA and in the murine model of SMA. Small-molecule compounds delivered systemically have the potential to increase the expression of SMN proteins, which are expressed ubiquitously in humans. Pinna and tail necrosis have been reported in the SMA murine model treated with SMN gene therapy39 or low doses of nusinersen40, which may result from insufficient systemic delivery or the impact of large-molecule drugs. Long-term clinical observations of these therapeutics are therefore recommended41,42. The small-molecule compound TEC-1 is expected to be a more promising drug for the long-term treatment of patients with SMA compared with the two approved large-molecule drugs whose systemic delivery is limited. From this single pharmacokinetics studies in juvenile (intraperitoneal) and adult (oral) FVB mice, the Kp values, which indicate the ratio of the compound in the brain and plasma, were greater than 1 (Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9). Thus, TEC-1 was efficiently distributed to the brain in both juveniles and adults, suggesting a favorable systemic delivery that includes the brain. Although the drug-metabolizing enzyme of TEC-1 has not yet been identified, TEC-1 was excreted from the plasma and brain in a time-dependent manner in juvenile mice. This indicates that TEC-1 can be developed for use in juvenile patients whose compositions of drug-metabolizing enzymes are different from those of adults. All SMA model mice administered 20 mg/kg TEC-1 intraperitoneally survived until weaning. TEC-1 was absorbed from the peripheral circulation, crossed the BBB, and completely rescued SMA phenotypes in vivo until weaning age. Interestingly, 66% (2 of 3 mice) of the SMA mice administered TEC-1 intraperitoneally survived, whereas 40% (4 of 10 mice) of SMA mice receiving oral administration survived, suggesting that bioavailability of the drug administered intraperitoneally is more favorable than when administered orally after weaning. To improve oral bioavailability, new formulation technologies43 will be applied to TEC-1 for the development of SMA therapeutics. At this time, the TEC-1 dosage is higher than that of risdiplam to extend the lifespan in the SMA murine model16. Finally, we will examine whether formulated TEC-1 increases the oral bioavailability, and enhances the exposure cap and therapeutic effects compared with risdiplam for SMA in preclinical and clinical studies.

In conclusion, these findings indicate that TEC-1 has selectivity toward SMN2 splicing over three secondary splice targets, suggesting that TEC-1 is a disease-modifying drug with a potentially higher therapeutic window compared to the SMN-C series, including risdiplam. Furthermore, TEC-1 did not inhibit the action of nusinersen in a cell culture system, supporting the possibility that TEC-1 could be utilized concomitantly with this existing SMA drug. Identification of TEC-1 contributes not only to the development of a promising SMA therapeutic but also to the feasibility of RNA-targeting small-molecule drug discovery that ensures clinical tolerability.

Materials and methods

SMN2 splicing modulators

RBS-001/TEC-1 (2-(4,6-dimethylpyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrazin-2-yl)-6-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)quinazolin-4(3H)-one) is a novel, orally available SMN2 splicing modifier that favors the production of full length SMN2 mRNA with high selectivity20. Risdiplam and the analogue, SMN-C3, were synthesized in-house according to the literature15,16. An antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) with the same sequence and modification as nusinersen was obtained from Gene Design Inc. (Japan).

Oligonucleotides for qRCR, RT-PCR

Oligo DNA standards, primers and probes were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies Inc. (USA). Their sequences are also available in Supplementary Tables 1, 2 and 3. The primer set and probe of human GAPDH, ready-made 20 × gene expression PCR assay [Cat.No.4326317E, Hs99999905_m1], was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (USA). Sequences of oligo DNA standards are shown in Supplemental Table 3.

Cell culture

Unless described otherwise, all reagents were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Both primary fibroblast cells (GM03813), collected from a SMA type II patient and induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) (GM24468) derived from GM03813, were obtained from Coriell Cell Repositories (USA). GM03813 cells was cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), high glucose containing 4.5 g/L glucose, 4 mM L-glutamine and 10% (by volume) fetal bovine serum (FBS). GM24468 cells was cultured in Essential 8 medium containing 3 µM Y-27632. GM24468 were dissociated with 0.5 × TrypLE Select solution. Hs683, human oligodendroglioma cell line, was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (USA) and maintained in DMEM, high glucose with 10% FBS. NRK-49F, rat kidney cell line, was cultured in DMEM (Wako, Japan) with 4.5 g/L glucose, 1 × GlutaMax, 1 × Non-Essential Amino Acids and 5% FBS. Madin-Darby Canine Kidney (MDCK) and Normal African Green Monkey Kidney Fibroblast Cells (CV-1) were maintained in Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (Wako) with 1 g/L glucose, 1 × GlutaMax and 10% FBS. Normal Cynomolgus Monkey Dermal Fibroblast (NCMDF) was cultured in DMEM (Wako) with 4.5 g/L glucose, 1 × GlutaMax and 20% FBS. NRK-49F, MDCK, CV-1 and NCMDF cells were obtained from the Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources (Japan). Human lymphoblastoid-derived TK6 cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (USA) and cultured in the culture medium consisted of RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated horse serum, 2 mmol/L sodium pyruvate, 100 unit/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin. All above cells were kept in a 37 °C incubator supplied with 5% CO2.

Differentiation of iPSCs to motor neuron

GM24468 cells were differentiated to motor neurons (MNs) via a motor neuron progenitor (MNP) as previously reported26. Briefly described, GM24468 were treated with a chemically defined neural medium, including DMEM/F12, Neurobasal medium at 1:1, 0.5% N2, 0.1% B27, 0.1 mM ascorbic acid (Sigma Aldrich, USA), 1 × GlutaMax, and 1 × penicillin/streptomycin. 3 µM CHIR99021 (Wako), 2 µM DMH1 (Sigma Aldrich) and 2 µM SB431542 (Wako) were added in the medium. The culture medium was changed every other day. GM24468 maintained under this condition for 6 days were induced into neuroepithelial progenitors (NEPs). NEPs were then dissociated and split with dispase (Stemcell technologies) and neural medium containing 0.1 µM RA (Sigma Aldrich), 0.5 µM Purmorphamine (Pur) (Merck, USA), 1 µM CHIR99021, 2 µM DMH1 and 2 µM SB431542. The medium was changed every other day. NEPs maintained under this condition for 6 days differentiated into OLIG2+ MNPs. The OLIG2+ MNPs were expanded with the same medium containing 1 µM CHIR99021, 2 µM DMH1, 2 µM SB431542, 0.1 µM RA, and 0.5 µM Pur, and split once a week. To induce MNs differentiation, OLIG2+ MNPs cultured in suspension in the above neural medium with 0.5 µM RA and 0.1 µM Pur. The medium was changed every other day. OLIG2+ MNPs under this condition for 6 days differentiated into MNX1+ MNs. The MNX1+ MNs were then dissociated into single cells and plated on Matrigel-coated plates. The MNX1+ MNs were cultured with 0.5 µM RA, 0.1 µM Pur and 0.1 µM Compound E (Calbiochem, USA) for 10 days to mature into CHAT+ MNs.

Transfection of ASO into cells

Transient transfection of GM03813 fibroblasts with nusinersen (final concentration 100 nM) was performed using Lipofectamine 2000. Cells were seeded 6 h prior to transfection at a density of 5 × 103 cells/well in 96-well plate. Transfection was performed according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were co-incubated either 0.1% DMSO or with TEC-1 at the concentration of 0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 1, and 3 µM for 24 h.

qPCR

GM03813 fibroblasts, GM24468-derived MNs, NRK-49F, MDCK, CV-1, or NCMDF cells were plated at a density of 0.5 or 1.5 × 104, 4 × 104, 5 × 103, 5 × 103, 8 × 103, or 6 × 103 cells/well on 96-well plates, respectively. After approximately 6 h, the medium was added with the same volume of culture medium containing each compound at the concentration of 0.06, 0.2, 0.6, 0.2, and 6 µM. The final concentration of DMSO was adjusted to 0.1% in culture condition.

All cells were treated with above compounds for 24 h and washed once with Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline without Ca and Mg [D-PBS (–)] (Wako or Nakarai Tesque). In case of using GM03813 or GM24468-derived MNs, cell lysis and reverse transcription were carried out using SuperPrep Cell Lysis & RT Kit for qPCR in accordance with manufacturer’s recommendations (Toyobo, Japan). qPCR was performed using THUNDERBIRD Probe qPCR Mix (Toyobo). The final concentrations of primers and probes were adjusted to 0.4 µM and 0.15 µM, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). Cycle conditions were as follows; 95 °C for 1 min; followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s; annealing and elongation at 60 °C for 1 min in the ViiA7 RT-PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The copy numbers of each target were normalized to those of GAPDH.

In the instances of using NRK-49F, MDCK, CV-1 or NCMDF, cell lysis and reverse transcription were carried out using Custom Cells to CT Lysis Components (Ambion) and Cells-to-CT RT Components (Ambion), each in accordance with manufacturer’s recommendations. qPCR was conducted using TaqMan Fast Advanced Master Mix. The final concentrations of primers and probes were adjusted to 0.4 µM and 0.15 µM, respectively. Cycle conditions were as follows; 50 °C for 2 min and 95 °C for 2 s; followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 1 s; annealing and elongation at 60 °C for 20 s in the ABI7900HT RT-PCR system (Applied Biosystems, USA). The relative quantification in gene expression was determined using the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Analysis of full length GALC with or without CHX

In order to elucidate the NMD of GALC transcripts, Hs683 cells were seeded at 5 × 103 cells/well in 96-well plates. After approximately 6 h, cells were co-incubated with final concentration of 200 µg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) and each compound (1 µM TEC-1 or 1 µM SMN-C3, 0.1% DMSO) for 6 h.

Total RNA was extracted with RNeasy Mini kit and RNase-Free DNase Set (Qiagen, USA) from compound-treated cells, followed by cDNA synthesis using High capacity cDNA revere transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) according to their protocols. PCR was done with PrimeStar GXL DNA polymerase (Takara). Briefly, cDNA of GALC coding full length sequence was amplified by PCR using the primer set, 5ʹ-GAGTCATGTGACCCACACAATG-3ʹ and 5ʹ-GAATGTTAGGGAACACACCAGGTA-3ʹ. Cycle conditions for GALC transcripts were used as follows; 98 °C for 1 min followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 10 s; annealing at 65 °C for 10 s; elongation at 72 °C for 4 min, and a final incubation at 72 °C for 5 min. The products were analyzed with agarose gel electrophoresis.

RT-PCR of cryptic exons of GALC, HTT and FOXM1

In order to elucidate splicing pattern of cryptic GALC and HTT transcripts, GM03813 cells were seeded at 5 or 15 × 103 cells/well in 96-well plates and incubated with TEC-1 or SMN-C3 (0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 0.1, 1 or 3 µM) for 6 h under final concentration of 200 µg/ml CHX. For FOXM1, GM03813 fibroblasts were plated at 1.5 × 104 cells/well in 96-well plate and incubated with TEC-1, SMN-C3 or risdiplam (0.03, 0.1, 0.3 and 1 µM) for 24 h.

cDNA synthesis was carried out using SuperPrep Cell Lysis & RT Kit for qPCR (Toyobo, Japan). PCR amplification was carried out using Takara Ex Taq Hot Start (Takara). The final concentrations of primers was adjusted to 1 µM (Supplementary Table 2). Cycle condition was as follows; 98 °C for 1 min followed by 45 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 10 s; annealing at 65 °C for 10 s; elongation at 72 °C for 1 min. PCR products were separated with electrophoresis on a 3% agarose gel and visualized after ethidium bromide staining under UV light.

Analysis of cryptic GALC and HTT transcripts

Hs683 cells which were co-treated with 1 µM SMN-C3 and 200 µg/ml CHX for 6 h were used for analysis of GALC transcript, while Hs683 cells which co-treated with 0.3 µM risdiplam and 200 µg/ml CHX for 6 h were used for the analysis of HTT.

Total RNA was extracted with RNeasy Mini kit and RNase-Free DNase Set from compound-treated cells, followed by cDNA synthesis using High capacity cDNA revere transcription kit according to their protocols. PCR was done with PrimeStar GXL DNA polymerase. Briefly, cDNA containing from exon 5 to exon 7 of GALC coding sequence was amplified by PCR using the primer set, 5ʹ-GAGTCATGTGACCCACACAATG-3ʹ and 5ʹ-GAATGTTAGGGAACACACCAGGTA-3ʹ. Cycle conditions for GALC transcripts were used as follows; 98 °C for 1 min followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 10 s; annealing at 65 °C for 10 s; elongation at 72 °C for 4 min, and a final incubation at 72 °C for 5 min. The products were analyzed with 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The second PCR was done using the first PCR products as templates with the same conditions but for only 25 cycles. One of the amplified products, derived from the cells treated with the compound, was sequenced directly using a primer, 5ʹ-CACAATGGCTGAGTGGCTACTC-3ʹ and Big Dye terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing kit. For analysis of the HTT transcripts, cDNA sequence from exon 42 to exon 55 was amplified by PCR using the primer set, 5ʹ-GAGGATTCTGACTTGGCAGCCA-3ʹ and 5ʹ-CACAGGCACAGTCATTGCACTGA-3ʹ with next condition; 98 °C for 1 min followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 98 °C for 10 s; annealing at 65 °C for 10 s; elongation at 72 °C for 2 min, with a final incubation at 72 °C for 4 min. The second PCR was performed using the first PCR product as a template under the same conditions but only for 20 cycles. The amplified product was sequenced directly using a primer, 5ʹ-ATGAATGCCTTCATGATGAACTCG-3ʹ and the above sequencing kit. DNA sequences were determined using an ABI-PRISM 3100 automatic sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

SDS-PAGE and western blotting

GM03813 fibroblasts and GM24468-derived MNs were seeded at 1.5 × 104 and 4 × 104 cells/well in 96-well plates and were treated with TEC-1 or SMN-C3 for 72 h at the concentration of 0.01, 0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 1, or 3 µM. After 72 h exposure of compound, GM24468 derived MNs and GM03813 fibroblasts were washed once with D-PBS (-), lysed with RIPA buffer (Wako) containing cOmplete (Sigma-Aldrich) and PhosSTOP (Sigma-Aldrich). The lysates were spun at 15,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C, and the supernatants were collected. The protein concentration was quantified with BCA kit (Wako). The lysates, adjusted to have the same protein amount, were mixed with NuPAGE LDS sample buffer containing DTT and heated at 95 °C for 5 min. Except for HTT detection, each sample (2 µg total protein/lane) was loaded Perfect NT Gel 7.5–15% gel (DRC, Japan) and run at 150 V for 60–70 min with Tris/glycine/SDS running buffer (BIO-RAD, USA). The proteins were transferred from the gel to Immobilon-P PVDF Membrane (Millipore, USA) with a transfer solution comprising 10% methanol and 1 × Novex Tris-glycine transfer buffer at 25 V for 180–240 min using Criterion blotter (BIO-RAD). In the case of HTT detection, each sample (2 µg total protein/lane) was loaded to Perfect NT Gel 7.5–15% gel and run at 150 V for 60–70 min with NuPAGE Tris–Acetate SDS Running Buffer. The proteins were transferred with a transfer solution comprising 10% methanol and 1 × Novex Tris-glycine transfer buffer at 25 V for 960 min using Criterion blotter. The membranes were blocked with Pierce Protein free T20 blocking reagent for 1 h and subsequently incubated with primary antibodies diluted with Can Get Signal Solution 1 (Toyobo) at room temperature for 1 h. Anti-SMN monoclonal antibody (MoAb)15 (1:1000 [fibroblasts], 1:2000 [iPSC]) (Cat. No. BD610646, BD Biosciences, USA), GAPDH MoAb44 (1:2000, Cat. No. 016-25523, Wako), anti HTT MoAb45 (1:1000, Cat. No. MAB2166, Millipore), or Choline acetyltransferase (ChAT) polyclonal antibody46 (1:2000, Cat. No. AB144P, Millipore) were used as the primary antibody. The membranes were washed with Tris-buffered Saline with Tween20 (TBS-T) three times and incubated with the secondary antibody, HPR-labeled anti-mouse IgG antibody (1:5000, Cat. No. NA9310-1ML, GE Healthcare, USA) or HRP-labeled anti-Goat IgG antibody (1:5000, Jackson laboratory, USA) diluted with Can Get Signal Solution 2 (Toyobo) at room temperature for 1 h. After washing with TBS-T four times, chemiluminescence signals were detected by Immunostar Zeta (Wako) and LAS-4000 (GE healthcare).

SMN HTRF

GM24468-derived MNs were seeded at 4 × 104 cells/well in 96-well plates and were treated with TEC-1 for 72 h at the final concentration of 0.03, 0.1, 0.3, 1, and 3 µM.

SMN protein concentration of the cells were quantified using an SMN HTRF kit15 (Cat. No. 63ADK033PEG, Cisbio, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The fluorescence emission was read at two different wavelengths (665 nm and 620 nm or 615 nm) using an Envision plate reader (PerkinElmer, USA) excited by 320 nm. The concentration of protein in each cell lysate were measured by BCA kit (BIO-RAD) and used for normalization.

GALC-enzyme activity assay

GALC enzymatic activities were quantified as reported by Wiederschain et al.47. Hs683 cells were seeded at 1.5 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plate. Cells were treated with TEC-1 (0.1, 0.3, or 1 µM) or SMN-C3 (0.03, 0.1, 0.3, or 1 µM) for 3 days. Hs683 cells were washed with D-PBS (–), collected with ultra-pure water using a cell scraper, and homogenized with homogenizers (NS-4, NS310E, Micotechnition, Japan) for 10 s. Cell lysates were centrifuged at 600 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, followed by collection of supernatants. The concentration of protein of each sample was quantified with a BCA kit. The samples were adjusted to 1 µg protein/µL (total volume 20 µL) with ultra-pure water and then 80 µL of reaction buffer (0.25% taurocholate, 0.05% oleic acid and 0.1 mol/L citrate, pH 4.4) containing 80 µM 6-Hexadecanoylamino-4-methylumbelliferone b-D-galactopyranoside (HMU-Gal, Carbosynth, UK) was added. Stop buffer (0.2 mol/L Glycine solution with NaOH, pH 10.6) was mixed with an equal amount of ethanol. The mixture was reacted at 37 °C for 20 h. The enzymatic reaction (10 µL) was quenched with 200 µL of stop buffer containing ethanol (EtOH). Signals were detected by reading the fluorescence emission at 450 nm with plate reader (Enspire, PerkinElmer) excited by 385 nm. The fluorescence intensity was corrected by the value of standard substrate of 6-hexadecanoylamino-4-methylumbelliferone (Cat. No. EH10520, Carbosynth).

Mass spectrometry for determination of psychosine and sphingosine

Hs683 cells were seeded at 1.5 × 105 cells/well in 6-well plates and were treated with TEC-1 or SMN-C3 for 12 days. The sample was extracted with EtOH and dried under nitrogen spray. Pellet was completely re-dissolved in EtOH using vortex and ultrasonication. The resulting sample was centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C. Analytes were separated from the supernatant and quantified by LC/MS/MS as reported by Boutin et al.48.

Evaluation of micronucleus test

Mitomycin (MMC), cyclophosphamide (CP) and colcemid (COL) were used as positive controls. These articles have been recommended for use in the OECD test guideline (Test No. 487)49. For metabolic activation, pre-cultured TK6 cells with the culture medium were supplemented with Sprague–Dawley rat liver mix (S9 mix, IEDA TRADING CORPORATION, Japan) at 3.33 vol%. Then, compound was mixed with the cell suspension and treated under the following treatment conditions:

Short-term treatment for 3 h without S9 mix, followed by a 21-h culture (−S9 mix assay),

Short-term treatment for 3 h with S9 mix, followed by a 21-h culture (+S9 mix assay), or

Continuous treatment for 24 h without S9 mix (24-h assay).

For treatment conditions 1 and 2, the cells in each well were centrifuged after the 3-h treatment, the supernatants were discarded, and the cells were washed twice with culture medium. The cells were further cultured with fresh culture medium for 21 h. The compound-treated cells were examined by the unaided eye for precipitation of compound at the start and end of treatment. After treatment, the rest of each cell suspension was centrifuged and then the cells were suspended in a 0.075 mol/L KCl solution at room temperature for 10 min. Then, 25 vol% acetic acid containing methanol was added and the centrifuged cells were fixed. The fixed cells were resuspended in a small amount of 3 vol% acetic acid containing methanol, which was changed two times by centrifugation. Finally, a drop of the cell suspension was transferred onto a slide and dried at room temperature. The slides were stained at room temperature in a 3 vol% Giemsa solution (Merck KGaA) diluted with Sörensen phosphate buffer (1/15 mol/L, pH 6.8, Muto Pure Chemicals Co. Ltd.). Four slides per dose (2 slides per well) were prepared. Each slide was coded randomly. The test was conducted at the following doses of TEC-1. -S9 mix assay: 1.5, 1.7, 1.9, 2.1, 2.3, 2.5, 2.7, 2.9, and 3.1 µg/mL, + S9 mix assay: 1.9, 2.1, 2.3, 2.5, 2.7, 2.9, 3.1, 3.3, and 3.5 µg/mL, 24-h assay: 0.9, 1.1, 1.3, 1.5, 1.7, 1.9, 2.1, 2.3, and 2.5 µg/mL. To perform scoring for compound and negative control groups, the number of cells in the suspensions was counted using a Coulter Counter (Z2; Beckman Coulter, Inc.). The positive control groups were not determined. A portion (0.5 mL) of the cell suspension was diluted with 20 mL of Isoton II, and 0.5 mL of this solution was used for cell counts. The cell number per 1 mL at each culture was calculated by the following formula.

The population doubling (PD) and relative population doubling (RPD) at each concentration was calculated by the following formula.

For the treated groups, the 3 consecutive concentrations were selected as follows. For −S9 mix assay condition, cytotoxicity, as indicated by a RPD of less than 50% was noted at 2.3 μg/mL of TEC-1 and higher; for + S9 mix assay condition, cytotoxicity was noted at 2.9 μg/mL of TEC-1 and higher; for 24-h assay condition, precipitation was noted at 1.5 μg/mL of TEC-1 and higher. Based on these results 1.9, 2.1 and 2.3 μg/mL of TEC-1 were analyzed for −S9 mix assay condition; 2.5, 2.7, and 2.9 μg/mL of TEC-1 were analyzed for + S9 mix assay condition; 1.1, 1.3, 1.5, μg/mL of TEC-1 were analyzed for 24-h assay condition. For all concentrations, 4000 mononuclear cells with cytoplasm were analyzed and the number of cells with micronucleus (micronuclei) was counted using a microscope (× 600). Micronucleus is identified as a round or oval small nucleus in the cytoplasm with the same staining intensity as the main nucleus. The diameter of each micronucleus should be less than 1/2 of the diameter of the main nucleus. Two investigators observed the slides. Each investigator scored 1000 cells for the frequency of micronucleated cells. Data from the two investigators were combined for each culture and the combined data from duplicate cultures were pooled for each concentration for each treatment condition. A cell having one or more micronuclei was recorded as a micronucleated cell. The test article was judged to be positive if the incidence of micronucleated cells between any test article treatment groups satisfied both criteria (1) and (2) shown below.

A significant difference in the incidence of micronucleated cells between the negative control group is detected in the statistical analysis and concentration-dependent increase was also detected in the statistical analysis.

The incidence of micronucleated cells is more than the historical control range (mean + 2SD).

Otherwise, the test article was judged to be negative.

Pharmacokinetic study in adult wild type FVB mice

TEC-1 was administered at doses of 2, 6, and 20 mg/kg for oral (suspended in 0.5% methyl cellulose aqueous solution) to male FVB mice (aged 8 weeks, 3 mice per a time point). After 0.5–120 h administration, blood and brain samples were collected. Blood samples with heparin were centrifuged for plasma collection. Brain samples were homogenized in saline 20% (w/v). The samples were deproteinized with acetonitrile and following by centrifugation, and the supernatants were analyzed by LC/MS/MS to obtain TEC-1 concentrations of the plasma and brain.

Pharmacokinetic study in neonatal FVB mice

TEC-1 was intraperitoneally administered at doses of 0.2, 0.6, and 2 mg/kg (suspended in saline/0.9% NaCl solution) to male FVB mice (10 days old, 3 mice per a time point). After administration, brain samples and blood samples with heparinized capillary tubes from heart were collected. Blood samples were centrifuged to obtain the plasma fraction. Brain samples were homogenized in 20% (w/v) saline. The samples were deproteinized with acetonitrile followed by centrifugation and the supernatants were analyzed by LC/MS/MS to obtain TEC-1 concentrations of the plasma and brain.

Animals and in vivo studies

A pair of heterozygous SMNΔ7 mice28 (mSmn+/−, SMN2+/+, SMNΔ7+/+) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (USA, stock number 005025). The homozygous SMNΔ7 mice (affected and referred to as “SMNΔ7 mice”; mSmn−/−, SMN2+/+, SMNΔ7+/+) was generated by cross-bleeding of heterozygous SMNΔ7 mice. All experiments were approved and monitored by the animal experiment committee of Gifu Pharmaceutical University and were performed after approval by the Bioethics and Biosafety Committee of Gifu Pharmaceutical University. All procedures relating to animal care and treatment confirmed to animal care guidelines issued by the National Institutes of Health.

Administration of TEC-1

SMNΔ7 mice were treated with 2, 6, and 20 mg/kg TEC-1 (succinate) once a day by intraperitoneal injection (TERUMO, Japan) from P2 to P23. TEC-1 was diluted in 0.9% NaCl (aqueous) for intraperitoneal injection. After P24, TEC-1 was administrated one a day orally using 0.4 × 0.7 mm feeding needle (Primetech Corporation, Japan). For oral administration, TEC-1 was diluted in distilled water (Otsuka Pharmaceutical Factory, Japan). Heterozygous mice received equal volumes of vehicle.

Behavioral analysis

Survival and body weight were assessed daily. Righting reflex test15 tests were performed daily at P6, 11 and 16. Righting time was defined as the time it took a pup to turn over to its front after being placed completely on its back (maximum 60 s). Dead individuals were set to 60 s.

Statistical analysis

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample sizes, but the sample sizes we used were consistent with those generally employed in the field. Comparisons between two groups were analyzed by Student’s t-test (unpaired, two-tailed). Dose-responsibility test was analyzed by one-way analysis of variance followed by William’s test or Dunnett’s test. In micronucleus test, Fisher’s exact test was performed in order to compare the incidence of micronucleated cells in the test article groups or the positive control group with that of the negative control groups for each treatment condition. When Fisher’s exact test showed statistical significance, the exact Cochran-Armitage trend test was performed to evaluate any dose–response relationship. Statistical processing was performed using the Microsoft Excel or GraphPad Prism Software (Prism 6 or 8), EXSUS statistical software package (CAC Croit Corporation, Japan).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by AMED under Grant Number JP19nk0101211. The authors are grateful to T Machida, and N Chinen, S Tsuji, T Mizoguchi for excellent technical assistance. The authors thank K Ono, H Takahagi, N Yoshida, T Yamasaki, M Tawada, T Kamei, K Miyata for helpful discussions.

Author contributions

All authors analyzed the data and interpreted the results. K.F. created and provided compounds and ligands. S.A., S.S., S.O., K.O. and K.T. performed experiments and analyzed experimental data. S.A., S.S. and S.O. wrote the manuscript. K.F., M.S., S.N. and H.H. contributed to manuscript writing and supervised the project.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

H.H. received a research grant from Reborna biosciences. S.S., S.O. and K.F. were employees of Reborna biosciences, Inc.. Reborna biosciences have filed a patent application (PTC/JP2019/025732, WO/2020/004594). S.A., K.O, K.T., S.N. and M.S. declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Shiori Ando and Shunya Suzuki.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-74346-9.

References

- 1.Cartegni L, Hastings ML, Calarco JA, de Stanchina E, Krainer AR. Determinants of exon 7 splicing in the spinal muscular atrophy genes, SMN1 and SMN2. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006;1:63–77. doi: 10.1086/498853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kashima T, Manley JL. A negative element in SMN2 exon 7 inhibits splicing in spinal muscular atrophy. Nat. Genet. 2003;34:460–463. doi: 10.1038/ng1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh NN, Androphy EJ, Singh RN. An extended inhibitory context causes skipping of exon 7 of SMN2 in spinal muscular atrophy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;315:381–388. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.01.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh NN, Androphy EJ, Singh RN. In vivo selection reveals combinatorial controls that define a critical exon in the spinal muscular atrophy genes. RNA. 2004;10:1291–1305. doi: 10.1261/rna.7580704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feldkötter M, Schwarzer V, Wirth R, Wienker TF, Wirth B. Quantitative analyses of SMN1 and SMN2 based on real-time lightCycler PCR: fast and highly reliable carrier testing and prediction of severity of spinal muscular atrophy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;70:358–368. doi: 10.1086/338627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh NK, Singh NN, Androphy EJ, Singh RN. Splicing of a critical exon of human Survival Motor Neuron is regulated by a unique silencer element located in the last intron. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;26:1333–1346. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.4.1333-1346.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh NN, Howell MD, Androphy EJ, Singh RN. How the discovery of ISS-N1 led to the first medical therapy for spinal muscular atrophy. Gene Ther. 2017;24:520–526. doi: 10.1038/gt.2017.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hua Y, Vickers TA, Okunola HL, Bennett CF, Krainer AR. Antisense masking of an hnRNP A1/A2 intronic splicing silencer corrects SMN2 splicing in transgenic mice. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2008;82:834–848. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finkel RS, et al. Nusinersen versus Sham control in infantile-onset spinal muscular atrophy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;377:1723–1732. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1702752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Food and Drug Administration. SPINRAZA. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-approvals-and-databases/drug-trials-snapshots-spinraza. (2017). Accessed 30 October 2019.

- 11.Wurster CD, et al. Intrathecal administration of nusinersen in adolescent and adult SMA type 2 and 3 patients. J. Neurol. 2019;266:183–194. doi: 10.1007/s00415-018-9124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Press release. https://www.novartis.com/news/media-releases/avexis-data-reinforce-effectiveness-zolgensma-treating-spinal-muscular-atrophy-sma-type-1.

- 13.Press release. https://www.roche.com/media/releases/med-cor-2020-08-10b.htm.

- 14.Sturm S, et al. A phase 1 healthy male volunteer single escalating dose study of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of risdiplam (RG7916, RO7034067), a SMN2 splicing modifier. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019;85:181–193. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naryshkin NA, et al. Motor neuron disease. SMN2 splicing modifiers improve motor function and longevity in mice with spinal muscular atrophy. Science. 2014;345:688–693. doi: 10.1126/science.1250127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ratni H, et al. Discovery of risdiplam, a selective survival of motor neuron-2 (SMN2) gene splicing modifier for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) J. Med. Chem. 2018;61:6501–6517. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sivaramakrishnan M, et al. Binding to SMN2 pre-mRNA-protein complex elicits specificity for small molecule splicing modifiers. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1476. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01559-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Escolar ML, et al. Psychosine, a marker of Krabbe phenotype and treatment effect. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2017;121:271–278. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2017.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang G, Liu X, Gaertig MA, Li S, Li XJ. Ablation of huntingtin in adult neurons is nondeleterious but its depletion in young mice causes acute pancreatitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2016;113:3359–3364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1524575113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fuji, K., Yamasaki, T., Suzuki, S., Ono, K. & Takahagi, H. Patent WO/2020/004594 (2020).

- 21.Zhang X, et al. A novel FOXM1 isoform, FOXM1D, promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and metastasis through ROCKs activation in colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2017;36:807–819. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim YH, Choi MH, Kim JH, Lim IK, Park TJ. C-terminus-deleted FoxM1 is expressed in cancer cell lines and induces chromosome instability. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:1907–1917. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maeda M, et al. Transcriptome profiling of spinal muscular atrophy motor neurons derived from mouse embryonic stem cells. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e106818. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fagerberg L, et al. Analysis of the human tissue-specific expression by genome-wide integration of transcriptomics and antibody-based proteomics. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2014;13:397–406. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.035600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y, et al. Purification and characterization of progenitor and mature human astrocytes reveals transcriptional and functional differences with mouse. Neuron. 2016;89:37–53. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Du ZW, et al. Generation and expansion of highly pure motor neuron progenitors from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6626. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu H, et al. Spinal muscular atrophy patient-derived motor neurons exhibit hyperexcitability. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:12189. doi: 10.1038/srep12189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le TT, et al. SMNDelta7, the major product of the centromeric survival motor neuron (SMN2) gene, extends survival in mice with spinal muscular atrophy and associates with full-length SMN. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005;14:845–857. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Butchbach ME, Edwards JD, Schussler KR, Burghes AH. A novel method for oral delivery of drug compounds to the neonatal SMNDelta7 mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2007;161:285–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palacino J, et al. SMN2 splice modulators enhance U1-pre-mRNA association and rescue SMA mice. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015;11:511–517. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J, Schultz PG, Johnson KA. Mechanistic studies of a small-molecule modulator of SMN2 splicing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:E4604–E4612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1800260115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh NN, Singh RN. How RNA structure dictates the usage of a critical exon of spinal muscular atrophy gene. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene. Regul. Mech. 2019;1862:194403. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2019.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Šoltić D, et al. Lamin A/C dysregulation contributes to cardiac pathology in a mouse model of severe spinal muscular atrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2019;28:3515–3527. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddz195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wijngaarde CA, et al. Cardiac pathology in spinal muscular atrophy: a systematic review. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2017;12:67. doi: 10.1186/s13023-017-0613-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davis RH, Miller EA, Zhang RZ, Swoboda KJ. Responses to fasting and glucose loading in a cohort of well children with spinal muscular atrophy type II. J. Pediatr. 2015;167:1362–8.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bowerman M, et al. Defects in pancreatic development and glucose metabolism in SMN-depleted mice independent of canonical spinal muscular atrophy neuromuscular pathology. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014;23:3432–3444. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Szunyogova E, et al. Survival motor neuron (SMN) protein is required for normal mouse liver development. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:34635. doi: 10.1038/srep34635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deguise MO, et al. Abnormal fatty acid metabolism is a core component of spinal muscular atrophy. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2019;6:1519–1532. doi: 10.1002/acn3.50855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Foust KD, et al. Rescue of the spinal muscular atrophy phenotype in a mouse model by early postnatal delivery of SMN. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010;28:271–274. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 40.Hua Y, et al. Peripheral SMN restoration is essential for long-term rescue of a severe spinal muscular atrophy mouse model. Nature. 2011;478:123–126. doi: 10.1038/nature10485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Messina S. New directions for SMA therapy. J. Clin Med. 2018;7:E251. doi: 10.3390/jcm7090251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mendell JR, et al. Single-dose gene-replacement therapy for spinal muscular atrophy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;377:1713–1722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1706198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams HD, et al. Unlocking the full potential of lipid-based formulations using lipophilic salt/ionic liquid forms. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2019;142:75–90. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2019.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ishimaru K, et al. Sphingosine kinase-2 prevents macrophage cholesterol accumulation and atherosclerosis by stimulating autophagic lipid degradation. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:18329. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-54877-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Munsie L, et al. Mutant huntingtin causes defective actin remodeling during stress: defining a new role for transglutaminase 2 in neurodegenerative disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011;20:1937–1951. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.González-Burguera I, et al. Highly efficient generation of glutamatergic/cholinergic NT2-derived postmitotic human neurons by short-term treatment with the nucleoside analogue cytosine β-D-arabinofuranoside. Stem Cell Res. 2016;16:541–551. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2016.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wiederschain G, Raghavan S, Kolodny E. Characterization of 6-hexadecanoylamino-4-methylumbelliferyl-beta-D- galactopyranoside as fluorogenic substrate of galactocerebrosidase for the diagnosis of Krabbe disease. Clin. Chim. Acta. 1992;205:87–96. doi: 10.1016/S0009-8981(05)80003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boutin M, Sun Y, Shacka JJ, Auray-Blais C. Tandem Mass spectrometry multiplex analysis of glucosylceramide and galactosylceramide isoforms in brain tissues at different stages of parkinson disease. Anal. Chem. 2016;88:1856–1863. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b04227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.OECD Guideline for the Testing of Chemicals; Test No. 487: In Vitro Mammalian Cell Micronucleus Test (29 July, 2016).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.