Abstract

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are a novel class of endogenous noncoding RNAs and have been shown to play important roles in a variety of physiological processes. Recently, dysregulation of circRNAs has been identified in many types of cancers. In this study, we analyzed the expression profile and biological functions of circMTO1 in ovarian cancer. We demonstrated that circMTO1 was downregulated in ovarian cancer tissues and cell lines. Upregulation of circMTO1 inhibited proliferation and invasion of ovarian cancer cells while downregulation of circMTO1 promoted these processes. Mechanistically, we showed that circMTO1 sponged miR-182-5p to support KLF15 expression, eventually leading to inhibition of ovarian cancer progression. In conclusion, our study suggested circMTO1 as a novel biomarker and therapeutic target for ovarian cancer treatment.

Keywords: CircMTO1, proliferation, invasion, ovarian cancer

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is one of the most common malignant tumors of reproductive organs in women1. Based on the histological differentiation, the disease can be classified into four types: serous, endometrioid, mucinous, and clear cell2,3. According to statistics, 239,000 new cases of ovarian cancer are annually diagnosed in the world, among which 152,000 women die from this disease4. Currently, there have been multiple therapeutic approaches such as surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy5–9. Despite great improvement in these therapeutics, the prognosis of ovarian cancer patients remains poor and the five-year survival rate is dissatisfying, which is less than 30%10. The high mortality of ovarian cancer is mainly attributed to late diagnosis and limited therapeutic strategies11. Thus, it is urgent to explore novel targets for early diagnosis and treatment of ovarian cancer.

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are a novel class of endogenous noncoding RNAs and characterized by covalently closed loop structures12,13. Besides, they are inherently resistant to exonucleolytic decay of RNAs and contain selectively conserved target sites of microRNAs (miRNAs)14. Increasing evidence has shown that circRNAs play an important role in physiological processes, regulation of cell functions, development of neurodegenerative diseases, and pathogenesis of heart diseases15,16. Recently, dysregulation of circRNAs has been identified in many types of cancers and thus investigations on their roles in cancer progression have emerged as a new field17–19. For example, Han et al. reported that circMTO1 was lowly expressed in hepatocellular cancer tissues and overexpression of circMTO1 suppressed hepatocellular cancer cell proliferation and invasion20. Rao et al. found that circMTO1 was significantly downregulated in chemoresistant glioblastoma cells and its upregulation reversed chemoresistance of glioblastoma cells by promoting cell apoptosis21. However, the biological functions of circMTO1 in ovarian cancer remain unclear.

In this study, we demonstrated that circMTO1 was downregulated in ovarian cancer tissues and cell lines. Upregulation of circMTO1 inhibited proliferation and invasion of ovarian cancer cells while downregulation of circMTO1 promoted these processes. Mechanistically, we showed that circMTO1 sponged miR-182-5p to support KLF15 expression, eventually leading to inhibition of ovarian cancer progression. All in all, our study suggested circMTO1 as a novel biomarker and therapeutic target for ovarian cancer treatment.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Tissue Samples

Ovarian cancer tissues and the adjacent normal tissues were collected from 48 patients who underwent surgery at China-Japan Union Hospital of Jilin University (Changchun, China). No patients received chemotherapy or radiotherapy before surgical resection. Every participant provided written informed consent. After collection, all tissue samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jilin University.

Cell Culture and Transfection

Human ovarian cancer cell lines (SKOV3 and OVCAR3) and the normal ovarian epithelial cell line IOSE80 were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Rockville, MD, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. All cell lines were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. For cell transfection, specific small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) against circMTO1, overexpression vectors of circMTO1 or KLF15, miR-182-5p mimics, and corresponding negative controls were obtained from GeneCopoeia (Rockville, MD, USA). Cell transfection was carried out using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA from tissues or cells was isolated using Trizol reagent (Takara, Dalian, China) and reversely transcribed into cDNA using the Prime Script RT Master Mix (Takara). The quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis was performed using PerfeCTa SYBR Green FastMix (Quanta Biosciences, Beverly, MA, USA) on an ABI Prism 7900HT system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) or U6 was used as an internal control. The relative expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method. The specific primers were as follows: circMTO1, 5’-TGCATCAGAGGCTTGGAGAA-3’ (forward) and 5’-AAGGAAGGGGTGATCTGACG-3’ (reverse); KLF15, 5’-TTCTCGTCGCCAAAATGCC-3’ (forward) and 5’-CCTGGGACAATAGGAAGTCCAA-3’ (reverse); GAPDH, 5’-GCTCTCTGCTCCTCCTGTTC-3’ (forward) and 5’-CCAAATCCGTTGACTC-3’ (reverse); miR-182-5p, 5’-TGCGGTTTGGCAATGGTAGAAC-3’ (forward) and 5’-CCAGTGCAGGGTCCGAGGT-3’ (reverse); U6, 5’-CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA-3’ (forward) and 5’-AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT-3’ (reverse).

Western Blot Analysis

Tissues or cells were lysed using RIPA lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA). The BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) was used to determine the protein concentration. An equal amount of protein was separated by 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The membranes were incubated with 5% skim milk and probed overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against KLF15 and GAPDH. Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 2 h. All antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Protein bands were visualized by electrochemiluminescence reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) and analyzed using the Quantity One system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA).

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) Assay

Cell proliferation was detected using the CCK-8 assay. In brief, cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at a density of 2 × 103 cells/well and cultured for different time. Then, CCK-8 reagents were added to each well and cells were incubated for another 4 h. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader.

Transwell Assay

Transwell chambers with 8 µm pores were used to measure cell invasion. 2 × 105 cells in serum-free medium were seeded into the upper chamber coated with Matrigel. Culture medium containing 10% FBS was added to the lower chamber. After incubation for 24 h, cells invading to the lower surface of the insert were fixed and stained. The number of invading cells from four random fields was counted under a microscope.

Luciferase Reporter Assay

The wild or mutant-type of circMTO1 and KLF15 containing the predicted miR-182-5p binding sites was inserted into the pmirGLO vector (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). 1×105 cells were cultured in a 24-well plate and co-transfected with wild or mutant-type reporter plasmids as well as miR-182-5p mimics or negative controls using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Forty-eight hours later, the luciferase activity was detected using the dual-luciferase reporter assay system (Promega).

Statistical Analysis

Data were shown as means ± standard deviation (SD). Differences between groups were compared using the Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA (followed by Scheffe test). Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 22.0 software. P < 0.05 indicated a statistically significant difference.

Results

CircMTO1 Is Downregulated in Ovarian Cancer Tissues and Cell Lines

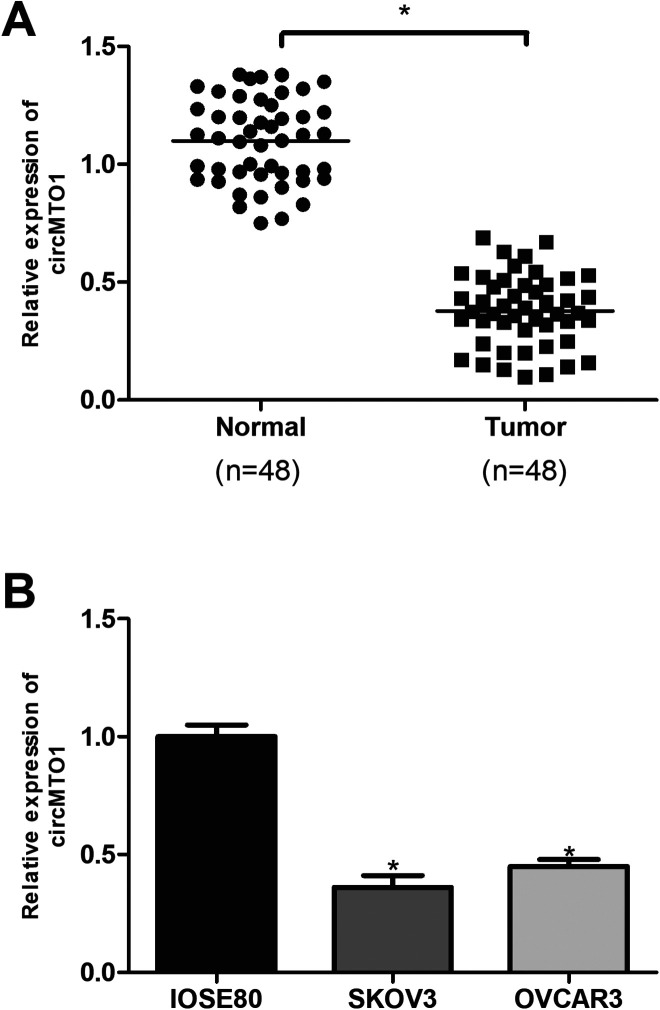

To explore the role of circMTO1 in ovarian cancer, we performed the qRT-PCR analysis to measure the expression of circMTO1 in ovarian cancer tissues and corresponding normal tissues from 48 patients. The results showed that circMTO1 was significantly decreased in ovarian cancer tissues in comparison with the adjacent normal tissues (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, we measured the expression of circMTO1 in ovarian cancer cell lines by the qRT-PCR analysis. Consistently, circMTO1 was also downregulated in ovarian cancer cell lines SKOV3 and OVCAR3 in comparison with the normal ovarian epithelial cell line IOSE80 (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

CircMTO1 is downregulated in ovarian cancer tissues and cell lines. (A) Relative expression of circMTO1 in ovarian cancer tissues and matched normal tissues by qRT-PCR. (n = 48). (B) Relative expression of circMTO1 in ovarian cancer cell lines by qRT-PCR. *P < 0.05.

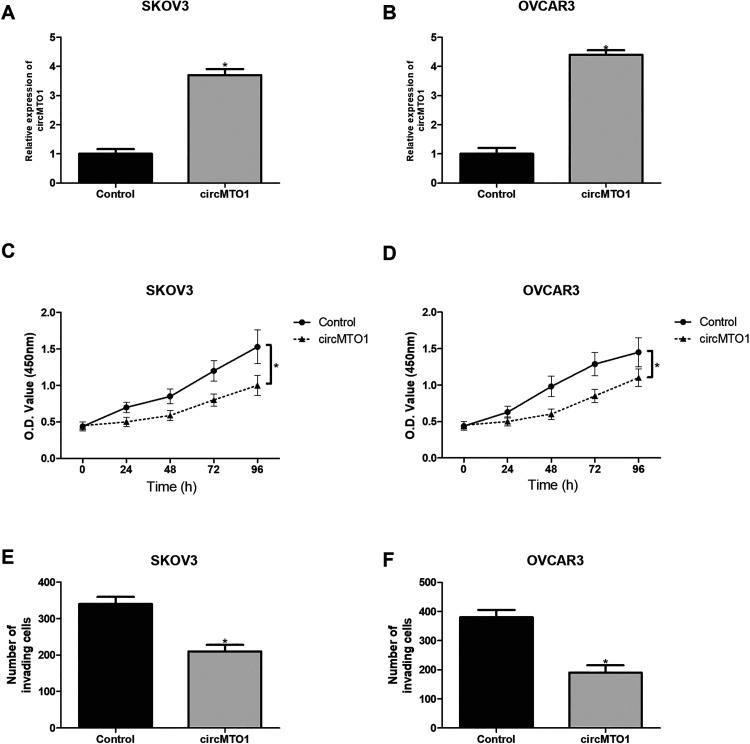

Upregulation of CircMTO1 Inhibits the Proliferation and Invasion of Ovarian Cancer Cells

To further investigate the biological functions of circMTO1, we overexpressed it in SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells by transfection of the circMTO1 expression vector. The qRT-PCR analysis showed that circMTO1 expression was markedly increased after transfection (Fig. 2A, B). Then we performed the CCK-8 assay to check the effect of circMTO1 on ovarian cancer cell proliferation. As shown in Fig. 2C, D, circMTO1 upregulation significantly inhibited the proliferative abilities of SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells. Moreover, we performed the transwell assay to examine the effect of circMTO1 on ovarian cancer cell invasion. The results showed that circMTO1 overexpression remarkably suppressed the invasive abilities of SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells (Fig. 2E, F).

Fig. 2.

Upregulation of circMTO1 inhibits the proliferation and invasion of ovarian cancer cells. (A, B) The qRT-PCR analysis for circMTO1 mRNA in SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells transfected with circMTO1 expression vector. (C, D) The CCK-8 assay was performed to measure the proliferation of SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells after transfection. (E, F) The transwell assay was performed to examine the invasion of SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells after transfection. *P < 0.05.

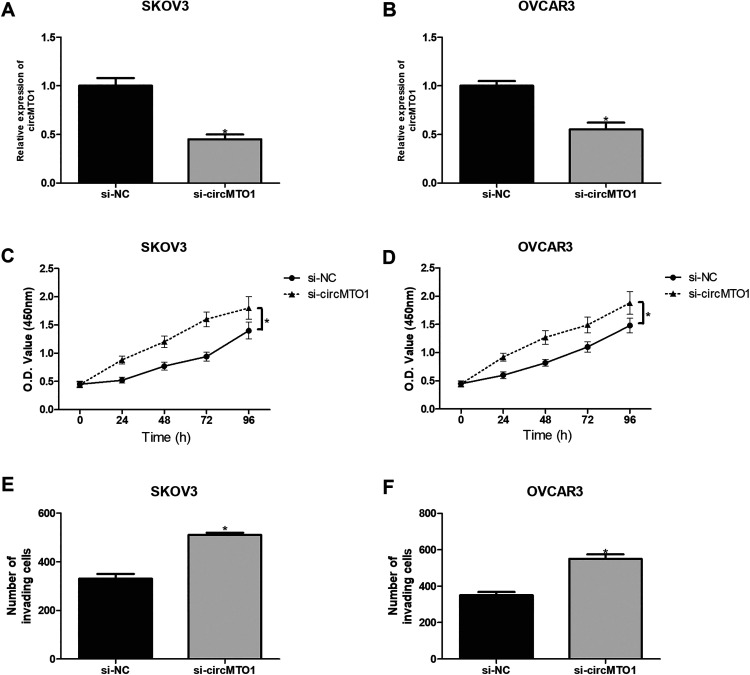

Knockdown of CircMTO1 Promotes the Proliferation and Invasion of Ovarian Cancer Cells

To test the effect of circMTO1 knockdown on ovarian cancer cell functions, we transfected SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells with circMTO1 siRNAs. The knockdown efficiency was confirmed by the qRT-PCR analysis (Fig. 3A, B). Meanwhile, circMTO1 depletion significantly promoted SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cell proliferation in comparison with corresponding control cells (Fig. 3C, D). Furthermore, circMTO1 knockdown obviously increased the number of invading SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells in comparison with corresponding control groups (Fig. 3E, F).

Fig. 3.

Knockdown of circMTO1 promotes the proliferation and invasion of ovarian cancer cells. (A, B) The qRT-PCR analysis for circMTO1 mRNA in SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells transfected with circMTO1 siRNA. (C, D) The CCK-8 assay was performed to measure the proliferation of SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells after transfection. (E, F) The transwell assay was performed to examine the invasion of SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells after transfection. *P < 0.05.

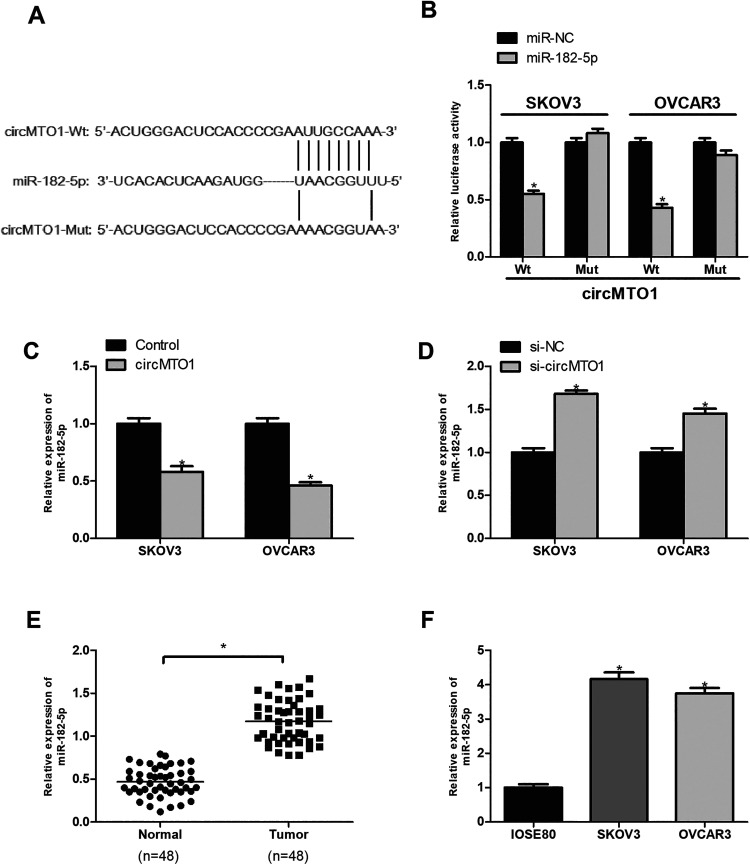

CircMTO1 Serves as a Sponge for MiR-182-5p in Ovarian Cancer Cells

Increasing evidence has shown that circRNAs could function as miRNA sponges to regulate gene expression22. To explore the molecular mechanism of circMTO1, we analyzed the potential target miRNAs of circMTO1 by the bioinformatics method. We identified miR-182-5p as a possible target and showed the potential binding site in Fig. 4A. To verify it, we performed the luciferase reporter assay. The results showed that ectopic expression of miR-182-5p significantly inhibited the luciferase activity of circMTO1-Wt reporter plasmids in SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells (Fig. 4B). Besides, circMTO1 upregulation dramatically decreased the expression of miR-182-5p (Fig. 4C), and vice versa (Fig. 4D). Furthermore, the qRT-PCR analysis showed that miR-182-5p was significantly overexpressed in ovarian cancer tissues and cell lines in comparison with the corresponding control group (Fig. 4E, F).

Fig. 4.

CircMTO1 serves as a sponge for miR-182-5p in ovarian cancer cells. (A) Putative miR-182-5p binding site in circMTO1. (B) The luciferase reporter assay demonstrated that miR-182-5p was a direct target of circMTO1. (C) CircMTO1 upregulation decreased miR-182-5p expression in SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells. (D) CircMTO1 downregulation increased miR-182-5p levels in SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells. (E) MiR-182-5p expression was elevated in ovarian cancer tissues in comparison with the adjacent normal tissues. (F) MiR-182-5p was overexpressed in ovarian cancer cells in comparison with the control cells. *P < 0.05.

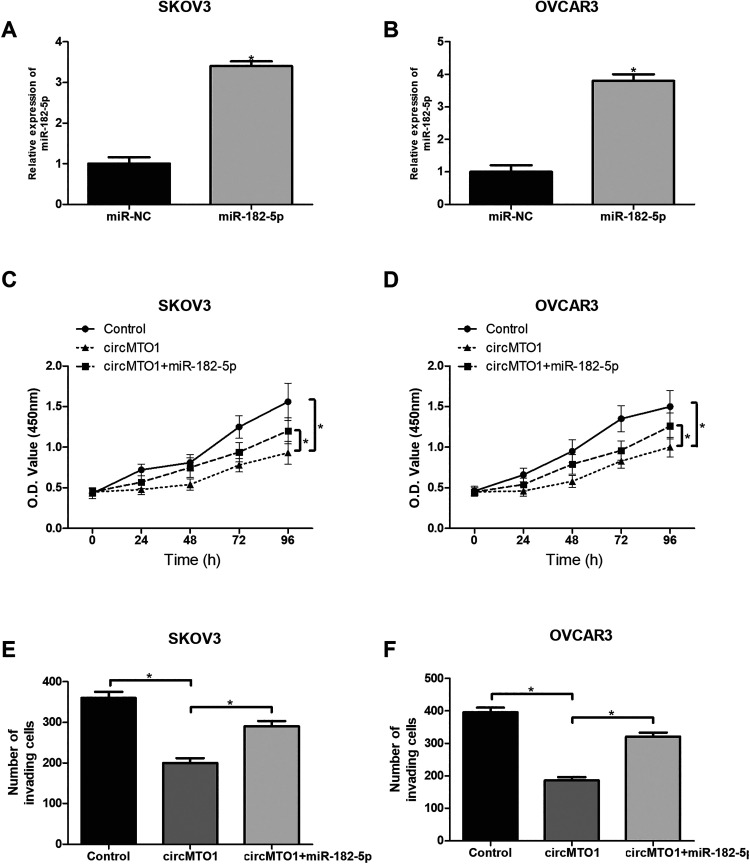

MiR-182-5p Mimic Reversed the Inhibitory Effects of CircMTO1 on Ovarian Cancer Cells

To further study the relationship between miR-182-5p and circMTO1 in proliferation and invasion of ovarian cancer cells, miR-182-5p mimic or its negative control was transfected into SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells. The qRT-PCR analysis was performed to confirm the transfection efficiency (Fig. 5A, B). Then we found that miR-182-5p transfection significantly reversed circMTO1-inhibited proliferation and invasion of SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells (Fig. 5C–F).

Fig. 5.

MiR-182-5p mimic reversed the inhibitory effects of circMTO1 on ovarian cancer cells. (A, B) Relative expression of miR-182-5p in SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells by qRT-PCR after transfection with miR-182-5p mimic. (C, D) The CCK-8 assay was performed to measure the proliferation of SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells after transfection. (E, F) The transwell assay was performed to examine the invasion of SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells after transfection. *P < 0.05.

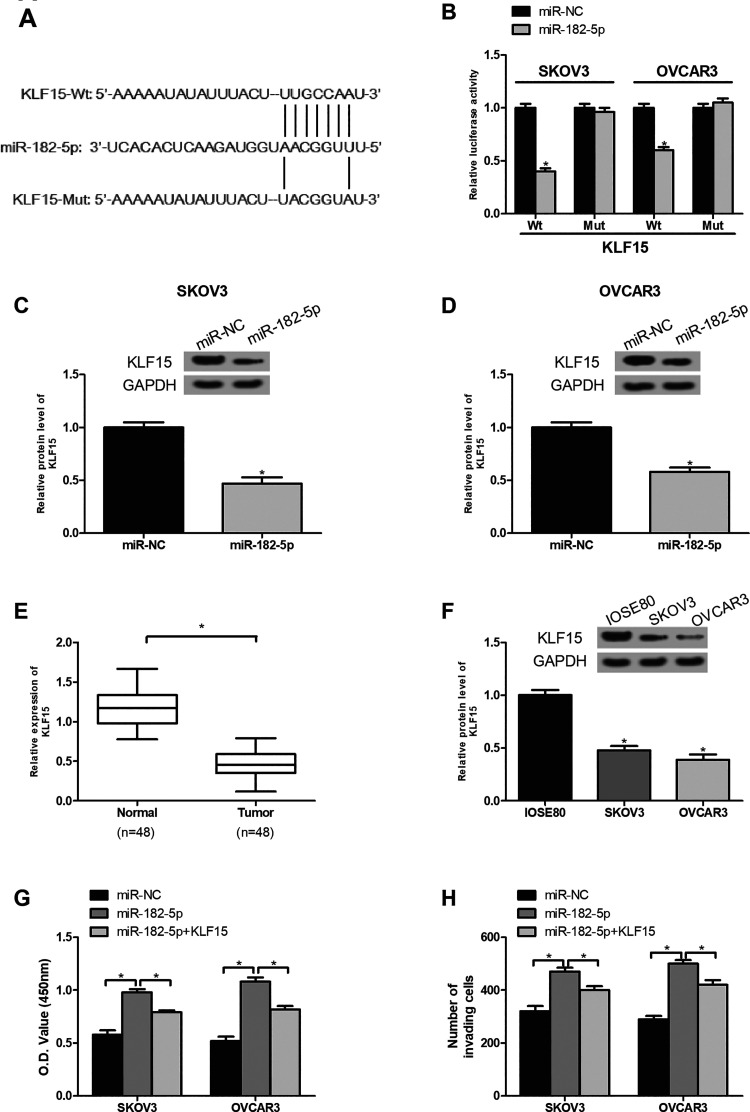

CircMTO1 Inhibits Ovarian Cancer Progression Through the MiR-182-5p/KLF15 Axis

We searched the downstream target of miR-182-5p via the bioinformatics analysis and identified KLF15 as a target of miR-182-5p. The potential binding sites of miR-182-5p in KLF15 were shown in Fig. 6A. To validate the prediction, we performed luciferase reporter assays. The results showed that overexpression of miR-182-5p significantly suppressed the luciferase activity of KLF15-Wt reporter plasmids in SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells (Fig. 6B), suggesting the direct interaction between miR-182-5p and KLF15. Furthermore, the western blot analysis showed that the protein level of KLF15 was markedly decreased in SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells after miR-182-5p mimics were introduced (Fig. 6C, D). Then we investigated the function of KLF15 in ovarian cancer. By the western blot analysis, we found that KLF15 expression was downregulated in ovarian cancer tissues and cell lines (Fig. 6E, F), indicating a tumor-suppression role in ovarian cancer. To confirm whether circMTO1 regulated ovarian cancer progression via the miR-182-5p/KLF15 axis, we performed rescue assays. The CCK-8 and transwell assays showed that overexpression of KLF15 significantly reversed the promoting effect of miR-182-5p on ovarian cancer cell proliferation and invasion (Fig. 6G, H).

Fig. 6.

CircMTO1 inhibits ovarian cancer progression through the miR-182-5p/KLF15 axis. (A) Putative miR-182-5p binding site in the 3’-UTR of KLF15 mRNA. (B) The luciferase reporter assay demonstrated that KLF15 was a direct target of miR-182-5p. (C, D) MiR-182-5p overexpression markedly decreased the protein level of KLF15 in SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells. (E) KLF15 expression was lowly expressed in ovarian cancer tissues in comparison with the adjacent normal tissues. (F) KLF15 was downregulated in ovarian cancer cells in comparison with the control cells. (G) The CCK-8 assay was performed to measure the proliferation of SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells after different treatment. (H) The transwell assay was performed to examine the invasion of SKOV3 and OVCAR3 cells after different treatment. *P < 0.05.

Discussion

As a leading cause of cancer-related death in females, ovarian cancer has posed a great threat to women worldwide23. According to statistics, over 75% of ovarian cancer patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage with nonspecific symptoms and a majority of the patients suffer from a low survival rate due to postsurgical metastasis24. Therefore, identification of novel prognostic biomarkers will be a great help in distinguishing patients with high risk of relapse.

CircRNAs are a group of new-type noncoding RNAs and have attracted a great attention. A growing body of evidence has shown that more and more circRNAs are aberrantly expressed in a variety of cancers25–27. In addition, circRNAs have been demonstrated to participate in many cancer-related biological processes28–30. For example, circBANP modulates colorectal cancer cell proliferation31. Upregulation of circDOCK1 suppresses cell apoptosis in oral squamous cell cancer32. CircMAN2B2 facilitates lung cancer cell proliferation and invasion33. These reports suggest a crucial role of circRNAs in cancer development. However, the correlation between circRNAs and ovarian cancer remains largely unknown.

To better understand the regulatory mechanism of circRNA in this study, we focused on circMTO1, which was downregulated in ovarian cancer tissues and cell lines. We found that overexpression of circMTO1 inhibited ovarian cancer cell proliferation and invasion while knockdown of circMTO1 promoted these processes. Like us, Liu et al. reported that circMTO1 upregulation suppressed breast cancer cell viability34. Consistently, Han et al. demonstrated that circMTO1 expression was decreased in hepatocellular cancer tissues and its enforced expression inhibited hepatocellular cancer progression20. These findings suggested that circMTO1 might serve as a tumor suppressor in cancer development.

CircRNAs frequently sponges miRNAs to participate in regulation of various physiological and pathological processes22. For example, circIRAK3 functions as a sponge of miR-3607 to facilitate breast cancer metastasis35. CircRBMS3 promotes gastric cancer progression by regulating miR-15336. In this study, we found that circMTO1 could directly bind to miR-182-5p. The qRT-PCR analysis showed that miR-182-5p expression was markedly reduced in ovarian cancer cells after circMTO1 upregulation, while its expression was significantly increased after circMTO1 knockdown. We also showed that miR-182-5p was highly expressed in ovarian cancer tissues and cell lines in comparison with the corresponding control group, suggesting an oncogenic role of miR-182-5p. Similarly, Li et al. reported overexpression of miR-182-5p in gastric cancer and its promoting effect on cell migration and invasion37. On the contrary, Wang et al. demonstrated that miR-182-5p had a lower expression in bladder cancer tissues than in the matched normal tissues and its upregulation reduced cell proliferation and invasion38. Thus, miR-182-5p may play different roles during cancer development with different cellular environment. All these observations provided further evidence in support of the notion that circRNAs can serve as miRNA sponge to regulate gene expression.

In the present study, we also searched the downstream target of miR-182-5p via bioinformatics analysis and identified KLF15 as a target of miR-182-5p. KLF15 is a transcription factor that is implicated in diverse biological processes and has recently been reported to play a significant role in cancer development39–43. In this study, we showed that KLF15 had a lower expression in ovarian cancer tissues and cell lines and its protein level was markedly decreased in ovarian cancer cells after miR-182-5p upregulation. Moreover, rescue experiments showed that overexpression of KLF15 significantly reversed the promoting effect of miR-182-5p on ovarian cancer cell proliferation and invasion. These results indicated that circMTO1 might inhibit ovarian cancer progression via regulating the miR-182-5p/KLF15 pathway.

One limitation of the present study is that we did not conduct xenograft tumor experiments to verify our in vitro results due to the limited laboratory conditions, and this issue will be the focus of our future study.

Conclusions

Our study revealed that circMTO1 was downregulated in ovarian cancer tissues and cell lines, and upregulation of circMTO1 inhibited proliferation and invasion of ovarian cancer cells by sponging miR-182-5p. Furthermore, we showed that miR-182-5p negatively regulated KLF15 expression. Taken together, the circMTO1/miR-182-5p/KLF15 axis might play an essential role in ovarian cancer progression.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions: Ning Wang, Qin-Xue Cao, and Jun Tian contributed to study design and manuscript preparation. Lu Ren was responsible for data collection and analysis. Hai-Ling Cheng and Shao-Qin Yang performed cellular experiments. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethical Approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Jilin University.

Statement of Human and Animals Rights: All experimental procedures with human subjects in this study were conducted in accordance with the Ethics Committee of Jilin University. This study does not contain any animal experiments.

Statement of Informed Consent: All patients involved in the study provided written informed consent.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Jun Tian  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6134-100X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6134-100X

References

- 1. Pięta B, Chmajwierzchowska K, Opala T. Past obstetric history and risk of ovarian cancer. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2012;19(3):385–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bertelsen K, Hølund B, Andersen E. Reproducibility and prognostic value of histologic type and grade in early epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;3(2):72–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Testa U, Petrucci E, Pasquini L, Castelli G, Pelosi E. Ovarian cancers: genetic abnormalities, tumor heterogeneity and progression, clonal evolution and cancer stem cells. Medicines. 2018;5(1):16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lewis GC, Blessing J. Ovarian cancer: use of multiple modality programs involving surgery, radiation therapy and chemotherapy. Cancer. 2015;40(S1):588–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Steiner M, Rubinov R, Borovik R, Cohen Y, Robinson E. Multimodal approach (surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy) in the treatment of advanced ovarian carcinoma. Cancer. 2015;55(12):2748–2752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Griffiths CT, Grogan RH, Hall TC. Advanced ovarian cancer: primary treatment with surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. Cancer. 2015;29(1):1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vafadar A, Shabaninejad Z, Movahedpour A, Fallahi F, Mirzaei H. Quercetin and cancer: new insights into its therapeutic effects on ovarian cancer cells. Cell Biosci. 2020;10(1):32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mirzaei H, Yazdi F, Salehi R, Mirzaei HR. SiRNA and epigenetic aberrations in ovarian cancer. J Cancer Res Ther. 2015;12(2):498–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schuurman MS, Kruitwagen RFPM, Portielje JEA, Roes EM, Lemmens VEPP, Aa MAVD. Treatment and outcome of elderly patients with advanced stage ovarian cancer: a nationwide analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;149(2):270–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wenderlein JM. Ovarian cancer: diagnosis and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109(11):208–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Qu S, Yang X, Li X, Wang J, Gao Y, Shang R, Sun W, Dou K, Li H. Circular RNA: a new star of noncoding RNAs. Cancer Lett. 2015;365(2):141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li LJ, Leng RX, Fan YG, Pan HF, Ye DQ. Translation of noncoding RNAs: focus on lncRNAs, pri-miRNAs, and circRNAs. Exp Cell Res. 2017;361(1):1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guo JU, Agarwal V, Guo H, Bartel DP. Expanded identification and characterization of mammalian circular RNAs. Genome Biol. 2014;15(7):409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu L, Wang J, Khanabdali R, Kalionis B, Tai X, Xia S. Circular RNAs: isolation, characterization and their potential role in diseases. RNA Biol. 2017;14(12):1715–1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Han B, Chao J, Yao H. Circular RNA and its mechanisms in disease: from the bench to the clinic. Pharmacol Ther. 2018;187(1):31–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shabaninejad Z, Vafadar A, Movahedpour A, Younes G, Mirzaei H. Circular RNAs in cancer: new insights into functions and implications in ovarian cancer. J Ovarian Res. 2019;12(1):84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Naeli P, Pourhanifeh MH, Karimzadeh MR, Shabaninejad Z, Movahedpour A, Tarrahimofrad H, Mirzaei HR, Bafrani HH, Savardashtaki A, Mirzaei H, Hamblin MR. Circular RNAs and gastrointestinal cancers: epigenetic regulators with a prognostic and therapeutic role. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2020;145:102854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Abbaszadeh-Goudarzi K, Radbakhsh S, Pourhanifeh M, Khanbabaei H, Davoodvandi A, Fathizadeh H, Sahebkar A, Shahrzad M, Mirzaei H. Circular RNA and diabetes: epigenetic regulator with diagnostic role. Curr Mol Med. 2020. doi: 10.2174/1566524020666200129142106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Han D, Li J, Wang H, Su X, Hou J, Gu Y, Qian C, Lin Y, Liu X, Huang M. Circular RNA circMTO1 acts as the sponge of microRNA-9 to suppress hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Hepatology. 2017;66(4):1151–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rao J, Cheng X, Zhu H, Wang L, Liu L. Circular RNA-0007874 (circMTO1) reverses chemoresistance to temozolomide by acting as a sponge of microRNA-630 in glioblastoma. Cell Biol Int. 2018;43(12):1525–1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kulcheski FR, Christoff AP, Margis R. Circular RNAs are miRNA sponges and can be used as a new class of biomarker. J Biotechnol. 2016;238:42–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jayson G, Kohn EC, Kitchener HC, Ledermann JA. Ovarian cancer. Lancet. 2014;384(9951):1376–1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Doubeni CA, Doubeni AR, Myers AE. Diagnosis and management of ovarian cancer. Am Fam Physician. 2016;93(11):937–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhong L, Wang Y, Cheng Y, Wang W, Lu B, Zhu L, Ma Y. Circular RNA circC3P1 suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma growth and metastasis through miR-4641/PCK1 pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;499(4):1044–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhou J, Zhang WW, Peng F, Sun JY, He ZY, Wu SG. Downregulation of hsa_circ_0011946 suppresses the migration and invasion of the breast cancer cell line MCF-7 by targeting RFC3. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:535–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ma HB, Yao YN, Yu JJ, Chen XX, Li HF. Extensive profiling of circular RNAs and the potential regulatory role of circRNA-000284 in cell proliferation and invasion of cervical cancer via sponging miR-506. Am J Transl Res. 2018;10(2):592–604. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yang C, Yuan W, Yang X, Li P, Wang J, Han J, Tao J, Li P, Yang H, Lv Q. Circular RNA circ-ITCH inhibits bladder cancer progression by sponging miR-17/miR-224 and regulating p21, PTEN expression. Mol Cancer. 2018;17(1):19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Xu Y, Yao Y, Zhong X, Leng K, Qin W, Qu L, Cui Y, Jiang X. Downregulated circular RNA hsa_circ_0001649 regulates proliferation, migration and invasion in cholangiocarcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;496(2):455–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li G, Yang H, Han K, Zhu D, Lun P, Zhao Y. A novel circular RNA, hsa_circ_0046701, promotes carcinogenesis by increasing the expression of miR-142-3p target ITGB8 in glioma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;498(1):254–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhu M, Xu Y, Chen Y, Yan F. Circular BANP, an upregulated circular RNA that modulates cell proliferation in colorectal cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;88:138–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang L, Wei Y, Yan Y, Wang H, Yang J, Zheng Z, Zha J, Peng B, Tang Y, Guo X. CircDOCK1 suppresses cell apoptosis via inhibition of miR-196a-5p by targeting BIRC3 in OSCC. Oncol Rep. 2018;39(3):951–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ma X, Yang X, Bao W, Li S, Liang S, Sun Y, Zhao Y, Wang J, Zhao C. Circular RNA circMAN2B2 facilitates lung cancer cell proliferation and invasion via miR-1275/FOXK1 axis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;498(4):1009–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu Y, Dong Y, Zhao L, Su L, Luo J. Circular RNA-MTO1 suppresses breast cancer cell viability and reverses monastrol resistance through regulating the TRAF4/Eg5 axis. Int J Oncol. 2018;53(4):1752–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wu J, Jiang Z, Chen C, Hu Q, Fu Z, Chen J, Wang Z, Wang Q, Li A, Marks JR. CircIRAK3 sponges miR-3607 to facilitate breast cancer metastasis. Cancer Lett. 2018;430:179–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li G, Xue M, Yang F, Jin Y, Fan Y, Li W. CircRBMS3 promotes gastric cancer tumorigenesis by regulating miR-153–SNAI1 axis. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(3):3020–3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li Y, Chen S, Shan Z, Bi L, Yu S, Xu S. MiR-182-5p improves the viability, mitosis, migration and invasion ability of human gastric cancer cells by down-regulating RAB27A. Biosci Rep. 2017;37(3):BSR20170136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 38. Wang F, Wu D, Xu Z, Chen J, Zhang J, Li X, Chen S, He F, Xu J, Su L. miR-182-5p affects human bladder cancer cell proliferation, migration and invasion through regulating Cofilin 1. Cancer Cell Int. 2019;19:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kaczynski J, Cook T, Urrutia R. Sp1- and Krüppel-like transcription factors. Genome Biol. 2003;4(2):206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Eaton SA, Funnell APW, Sue N, Nicholas H, Pearson RCM, Crossley M. A network of Krüppel-like factors (Klfs). J Biol Chem. 2008;283(40):26937–26947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mcconnell BB, Yang VW. Mammalian Krüppel-like factors in health and diseases. Physiol Rev. 2010;90(4):1337–1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sun C, Ma P, Wang Y, Liu W, Chen Q, Pan Y, Zhao C, Qian Y, Liu J, Li W. KLF15 inhibits cell proliferation in gastric cancer cells via up-regulating CDKN1A/p21 and CDKN1C/p57 expression. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62(6):1518–1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wang X, He M, Li J, Wang H, Huang J. KLF15 suppresses cell growth and predicts prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;106:672–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]