Abstract

Since the emergence of MRSA in the 1960s, a gradual increase in infections by resistant bacteria has been observed. Clinical manifestations may vary from brand to critical condition due to host risk factors, as well as pathogen virulence and resistance. The high adaptability and pathogenic profile of MRSA clones contributed to its spread in hospital and community settings. In Brazil, the first MRSA isolates were reported in the late 1980s, and since then different genetic profiles, such as the Brazilian epidemic clone (BEC) and other clones considered a pandemic, became endemic in the Brazilian population. Additionally, Brazil's MRSA clones were shown to be able to transfer genes involved in multidrug resistance and enhanced pathogenic properties. These events contributed to the rise of highly resistant and pathogenic MRSA. In this review, we present the main events which compose the history of MRSA in Brazil, including numbers and locations of isolation, as well as types of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) found in the Brazilian territory.

1. Introduction

Outbreaks of nosocomial and community-associated infections with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) have been reported as highly relevant worldwide. Attention to such pathogenic bacteria increased progressively since the first reports of resistance to antimicrobial agents. Penicillin was the first antibiotic to be introduced in clinical practice, in 1940. Shortly after, the selection of β-lactamase-producing bacteria marked the beginning of the first wave of antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), which continues today [1].

The rapid spread of penicillin resistance briefly came to a halt after the introduction of the second-generation, semisynthetic methicillin in the 1960s. However, MRSA soon emerged in England, and only in 1981, this mechanism of resistance was unraveled: these strains harbored mutant penicillin-binding proteins, designated PBP-2a, which showed a reduced affinity for methicillin. PBP-2a is encoded by mecA, a gene located in the S. aureus chromosome [2]. Thereafter, new cases of hospital-acquired infections were reported in other countries such as Australia and the United States [3, 4]. Due to the use of new antibiotics, a slight decrease in MRSA prevalence was noticed. However, because of selective pressure, strains of S. aureus began to display a multidrug resistance profile. Cases of MRSA resistant to both β-lactams and gentamicin began to be reported in health units at the end of the 1970s [5–7]. In the 1980s, reports of outbreaks and infections caused by MRSA increased gradually.

The genetic profile of MRSA began to be clarified only after 1999, when the gene coding a mutated form of the PBP of the N315 resistant clone isolated in Japan, in 1982, was discovered [8]. In 2001, it was reported that such a sequence was inserted into a mobile cassette within the chromosomal DNA, called staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec). Thereafter, the first three isolates of SCCmec-containing S. aureus were used to designate the first three types of cassettes, in order of isolation [9]. To date, fourteen types of SCCmec were described in S. aureus [10, 11]. They were identified according to different combinations of components of their sequences, including the mec complex, the cassette chromosome recombinase (ccr) complex, and J regions [10, 12].

Brazil is the largest country in Latin America and the 5th largest country in the world. Reviewing the history of MRSA in Brazil will help to better understand the spread of this important pathogen in Latin America, as well as in the new world. In Brazil, there are some epidemiological surveillance systems of resistant bacteria which do not work at a national level [13, 14]. However, in 2018, a program named PAN-BR (National Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Antimicrobial Resistance in Brazil) was developed [15]. Although it is not specific for the control and monitoring of MRSA, it was designed based on objectives pre-established by organizations, such as the World Health Organization, and aims to apply strategies for the prevention, control, and monitoring of infections caused by antimicrobial-resistant pathogens, including MRSA. One of the strategic objectives of PAN-BR is “to strengthen knowledge and the scientific basis through surveillance and research” [15]. Therefore, the data provided in this review will contribute to the performance and development of this program, as well as other strategic action plans suggested by the Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA) for the prevention and control of resistance in the country [16].

In this review, we present the history of MRSA in Brazil. Numbers and locations of isolation, as well as types of SCCmec found in the Brazilian territory, are discussed in sections by decade, since the 1980s. As inclusion criteria, all published studies reporting the isolation of MRSA from human samples in Brazil were used in this review. In addition, the prevalence of MRSA by region, as well as the frequency types of SCCmec, is shown. Text sections are concentrated on a critical review of the main events which compose the history of MRSA in Brazil. The articles were searched in MEDLINE/PubMed and SciELO databases by using the keywords “MRSA Brazil.” We found 597 articles, and after applying exclusion and inclusion criteria, 199 articles were selected.

1.1. The 1980s

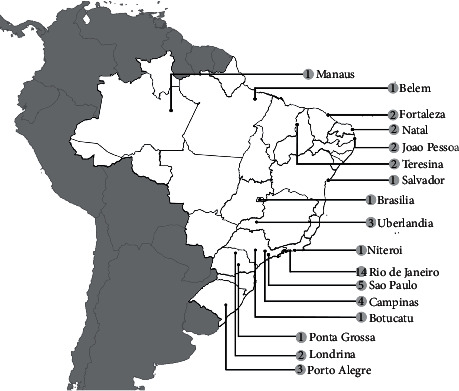

The first cases of MRSA in Brazil were reported in 1987 in Rio de Janeiro, and although they were not published, these events were mentioned by Ramos et al. in 1999 [17]. Such publication was the only one to report MRSA in the 1980s in Brazil, as shown in Figure 1. The incidence of MRSA was reported to be approximately 8%. Variances in the occurrence of MRSA isolates were reported in the following two years: with a decrease of 7.2% in 1988 and the following increase to 33% in 1989 [17]. From 1987 to 1994, Tresoldi and colleagues reported that 257 of 421 S. aureus isolates were MRSA. However, although S. aureus is to be isolated with the highest frequency (20.9%), MRSA isolates in this study were reported only in the 1990s by Tresoldi and colleagues [18].

Figure 1.

Map with georeference of MRSA reports showing the number of publications by isolation location during the 1980s.

After the global spread of MRSA, new antimicrobial agents, such as Synercid, daptomycin, linezolid, and tigecycline, were introduced during the treatment of infections caused by methicillin-resistant bacteria, which may have contributed to broadening mechanisms of multidrug resistance [19–23]. In a study published in 1989, which involved 106 strains of S. aureus from 21 countries, including Brazil, 90% of the samples were shown to be multiresistant to antimicrobial agents. Relevantly, the Brazilian strains showed resistance to fourteen antibiotics in this same study [24].

1.2. The 1990s

The first three waves of resistance of S. aureus of antimicrobial drugs were characterized based on its spread specifically in health care environments. The first wave was characterized by the emergence of strains capable of producing penicillinase, which inactivates penicillin. The emergence of MRSA strains marked the second wave. The disappearance of the archaic clone and the raise of new clones marked the third resistance wave [25]. The fourth wave has been marked by the introduction of community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA). However, the hospital clones were still prevalent in Brazil in the 1990s [26]. Compared to the 1980s, the number of occurrences of MRSA increased gradually in different health care facilities in Brazil [17, 27–30]. The spread of MRSA continued to be reported in different hospitals in São Paulo [31, 32]. Restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLP) showed the spread of MRSA clones, which indicated that microbial transfer was occurring possibly due to an interhospital connection involving patients and health workers [31, 32]. Furthermore, 91 MRSA isolates were found as microbiota composing of hospital food handlers in Teresina [33]. Such results indicated that transmission by physical contact was a determining factor of the occurrence for nosocomial outbreaks caused by both susceptible and resistant S. aureus [34, 35].

The theory of interhospital connection was reinforced when the same clone of MRSA was isolated from different locations at the same hospital in Joao Pessoa, in 1992 [36] and thereafter was found in the Campinas University Hospital, in two different studies [18, 37]. Such a clone was shown to be the same one found by Sader et al. in São Paulo, in 1993 and 1994 [31, 32]. The spread of MRSA was also shown to happen in an intrahospital way, as reported by a study carried out in Rio de Janeiro, in which propagation of a single virulent multidrug-resistant clone within the same hospital caused a relevant number of deaths [38].

A study carried out in five Brazilian cities showed in a systematic way that the interhospital communication was not restricted to nearby areas due to the spreading of bacteria with the same genetic pattern to different regions of the country [39]. Such a genetic pattern was identified by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) of chromosomal DNA. The epidemic MRSA was named as Brazilian epidemic clone (BEC) and became one of the five most-discussed MRSA clones around the world [28, 39]. Epidemiological studies aiming to investigate the spread of BEC were carried out in the 1990s in both Brazil and other countries, such as Portugal, Argentina, Chile, and Italy [28, 40–42]. MRSA strains containing both the polymorphic form type XI of the mec gene and type B of the Tn554 gene were classified as the A genetic pattern of BEC (BEC A). Although this pattern has been identified more frequently, some studies have isolated MRSA that differed minimally from BEC A. Such variants, including BEC A, were grouped as the Brazilian epidemic clonal complex (BECC) [30, 43].

After such reports, BEC was massively searched in several hospitals of Brazil evidencing its wide geographical distribution and predominance [42, 44]. The study by Oliveira et al. showed that from 83 MRSA isolated in 14 states in Brazil, 78.3% contained the mecA gene with polymorphism XI and Tn554 type B (BEC A). Moreover, isolates were shown to be multiresistant to drugs. These results clearly showed the spread of the BEC and its variants in Brazil [45, 46].

Genetic patterns of BECC isolates were shown to be diverse regarding their antimicrobial resistance and pathogenicity such as to be capable of forming biofilm and adhere and invade airway epithelial cells [30, 47]. The multiresistance is another common feature among BECC isolates. They carry structures such as plasmids and transposons that are responsible for resistance to other drugs within the cassette. In addition to methicillin, strains may be resistant to clindamycin, erythromycin, cephalothin, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, and chloramphenicol [39]. These strains have also shown high-level resistance to mupirocin. It is due to the insertion of the PMG1 plasmid, which carries a novel ileS gene that encodes a novel isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase, homolog to antibiotic target [48–50]. Such multiresistance presented by MRSA and the high frequency of nosocomial infections are associated with risk factors such as insertion of classic pathogens into host microbiota, prolonged hospitalization, and misuse of antibiotics [51–53]. This ability to adapt is probably related to genetic diversity into the BECC reported in different published studies [54, 55]. These reports indicated a relevant genetic diversity into the BECC at the ending of the 1990s.

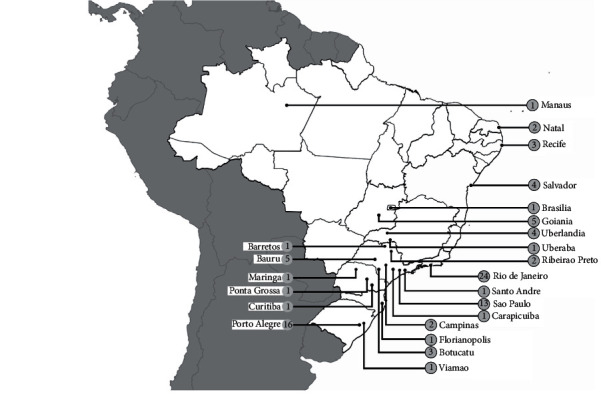

Therefore, other clones or subclones were reported in Brazilian hospitals. The first report of non-BEC MRSA, which presented different genetic patterns from that characterized by BEC, such as mecA type III and Tn544 type B polymorphism, was carried out in 1996 [56]. Although there were reports of diversity in genetic profiles, the BEC A was still prevalent among the isolates, as occurred in Teresina, Rio de Janeiro, Uberlandia, and Belem [30, 49, 57, 58]. However, the type of SCCmec was not yet known. In the 2000s, it was reported that the BEC clone carries the SCCmec type III. Such a cassette type was thus shown to be the most frequent in Brazil in the 1990s [55, 59]. The number of MRSA isolation reports published in the 1990s is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Map with georeference of MRSA reports showing the number of publications by isolation location during the 1990s.

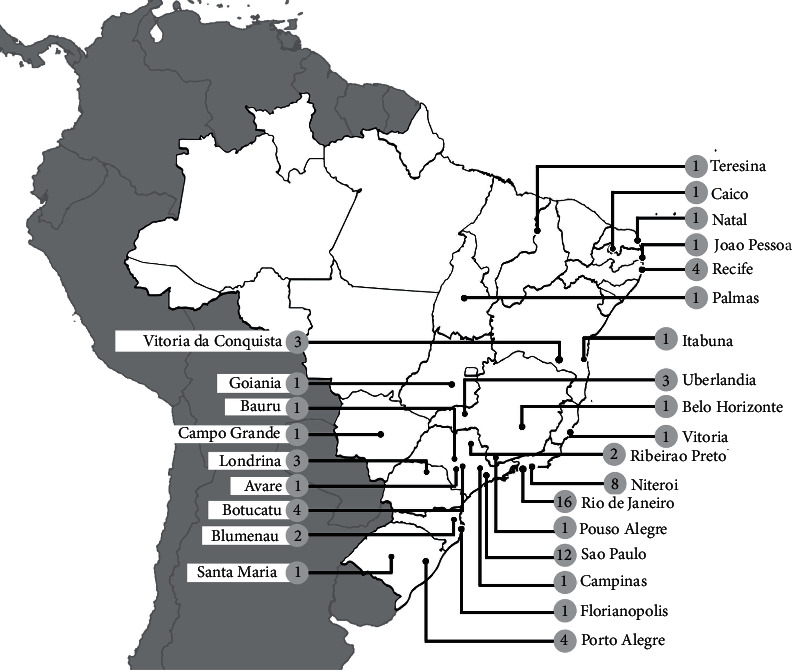

1.3. The 2000s

In the 2000s, MRSA remained a concern in Brazil, with new records in the prevalence of resistant bacteria, with an increase in the number of cases of infections [60]. Figure 3 shows the number of reports by location published in this decade. Strains of the BECC continued to be predominant in Brazilian hospitals until a certain moment [29, 61–66]. However, over the decade, other international (non-BEC) clones were imported and started to be reported in different regions of Brazil [67, 68]. Such international clones carried other types of cassettes and were named according to the location they were isolated for the first time [69]. Some of these clones, although considered pandemic, were reported less frequently in Brazil, such as the Iberian clone (SCCmec type I); the Hungarian clone (SCCmec type III); Cordobes/Chilean clone (SCCmec type I); an MRSA clone carrying SCCmec type V [69–71]. However, other clones considered to be of great relevance in a global context were reported in a larger frequency. One of these clones was the New York/Japan clone, which is also classified as HA-MRSA (hospital-acquired MRSA) but carrying SCCmec type II. Such a clone was initially isolated in a lower frequency with regard to the BEC. Nevertheless, it was gradually spread in the hospital environment [47, 65, 71–73]. Its fixation in Brazilian hospitals was a milestone in history because, in addition to its spread, the New York/Japan clone presented resistance to β-lactam antibiotics, ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, and clindamycin, hindering the treatment of patients [74].

Figure 3.

Map with georeference of MRSA reports showing the number of publications by isolation location during the 2000s.

The pediatric clone, which is of great world relevance, had also an important role in the history of MRSA in Brazil. It carries the SCCmec type IV, which is commonly present in strains of CA-MRSA. However, although not classified as HA-MRSA, it was reported in a relevant number of nosocomial infections. Its profile of resistance diverges from most of HA-MRSA, presenting a susceptibility to a wide range of antimicrobial agents, except β-lactams. Although non-multidrug resistant, the pediatric clone began to exhibit important virulence factors. Isolates obtained in different cities showed the capacity of forming biofilm and of producing enterotoxins. Such virulence factors increase the bacterial pathogenicity, exacerbating infections mainly in immunocompromised, children, and elderly [47, 72, 75, 76].

The pediatric clone has similarities and divergences with another clone that also gained prominence: the Oceania Southwest Pacific (OSP) clone. In common, both carry SCCmec type IV and are typically non-multiresistant. However, different from the pediatric clone, the OSP clone was shown to cause infections in the community [77]. Community MRSA strains were first reported in western Australia in the early 1990s [78]. Such strains were initially devoid of Panton-Valentine leucocidin (PVL), but subsequent cases of community MRSA were now recorded as PVL positive [79]. Such a clone was first described in Brazil as CA-MRSA before being isolated from patients with skin and soft tissue infections which were not exposed to classical risk factors for nosocomial infection [80]. Several infections caused by CA-MRSA ranging from mild [81–85] to severe [86–88] were reported in Brazil in the 2000s. Although the properties of CA-MRSA appear to make it less aggressive than hospital clones, the OSP clone presents virulence factors involved in the high pathogenicity, such as the PVL, which kills immune cells and induces tissue necrosis [82, 83, 86, 87, 89, 90]. Although originally found in MRSA SCCmec type IV, PVL has also been reported in strains with other types of cassettes mostly present in HA-MRSA strains, such as BEC, due to a horizontal transfer of genes [29, 63, 91, and 92]. Such horizontal transference indicates contact between CA and HA-MRSA. Thus, CA-MRSA was identified in health units, and HA-MRSA clones were identified in the community [74, 93, and 94]. As a result, in addition to the presence of PVL in clones that at the time were considered unusual carriers, the ability to form biofilms was spread among the various types of MRSA [92, 95]. In addition to the spread of virulence factors, genes of resistance to antimicrobial drugs were transferred to non-multiresistant clones, which resulted in strains with a profile of pathogenicity and resistance [75, 89, and 96].

The spread of different clones was observed in the mid-2000s in Brazil [92, 97]. Different clones of MRSA carrying SCCmec type IV, including CA-MRSA, were detected in 19 of 20 MRSA isolated from patients with nosocomial infections in a hospital of Rio de Janeiro. In Porto Alegre, moreover to the isolation of the OSP clone, the pediatric clone was shown to be circulating [71, 96, 98, and 99]. In São Paulo, a profile similar to CA-MRSA was identified as the cause of 95% of bloodstream infections. Such reports indicated the adaptive capacity of CA-MRSA to the hospital environment [75].

An important study was published in 2012 describing samples collected in the south, southeast, and northeast of the country and revealed the most frequent cassettes circulating in Brazil. The cassettes were identified based on the detection of clonal complexes (CC) and the most common were shown to be SCCmec types II, III, and IV [47, 64, 65, 72, 100, and 101]. These cassettes were reported gradually during the decade of 2000, showing that there was an evolution, adaptation, and propagation of different clones of MRSA in Brazil.

1.4. The 2010s

In the 2010s, MRSA remained being increasingly reported in Brazil, as shown in Figure 4. The most common clones in the hospital environment continued to be those carrying the SCCmec types II, III, and IV [14, 65, 73, 102, 103]. However, SCCmec type II, in contrast to the last decade, was reported as one of the most prevalent clone [103–109]. Relevantly, the New York/Japan clone, which carries SCCmec type II, was shown to become resistant to daptomycin, tigecycline, and vancomycin [67, 110]. In addition, such a clone was shown to become capable of producing α-hemolysin and PVL and forming a biofilm [14, 104, 105]. Thus, multiresistance and virulence remained evolutionary events among MRSA clones. As a further example of adaptation and evolution, in 2011, a CA-MRSA strain was shown to have acquired the vanA gene, which confers resistance to vancomycin. This was the first CA-MRSA reported being resistant to this antimicrobial agent [111].

Figure 4.

Map with georeference of MRSA reports showing the number of publications by isolation location during the 2010s.

Clones carrying the SCCmec type IV continued to be the main producers of PVL and biofilms [112, 113]. These virulence factors were involved in infections reported in both hospital and community environments due to a horizontal transfer of genes among CA-MRSA and HA-MRSA strains. In addition to the New York/Japan clone, the production of biofilms and PVL began to be seen in more unusual and less frequent clones, such as those carrying SCCmec types V and I [114, 115]. These types of cassettes, as well as the SCCmec type VI, UK/EMRSA-3, Hungarian, and Iberian clones, were identified in the history of MRSA in Brazil at a low frequency [104, 116–119].

The last relevant chapter of the history of MRSA in Brazil also involves SCCmec V. An unusual genetic profile called clonal complex 398 (CC398) began to be reported. Such variants may carry either type IV or type V cassettes. This complex is directly associated with livestock and thus called LA-MRSA (livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus). This type of MRSA emerged the first time from animal infection samples, in 1972 [120], but was subsequently isolated from humans, especially those who had direct access to animals [121–123]. In 2010, it was first isolated in Brazil from a patient with cystic fibrosis who had contact with animals from the farm [124]. Later, between 2011 and 2016, six clones of the same complex were isolated from children in Rio de Janeiro [125]. However, such isolates were not classified as LA-MRSA because the children did not present the typical risk factors for the acquisition of this lineage, which includes the previous contact with animals. These results showed that clones of this lineage are not restricted to animals and have adapted to a new kind of host.

1.5. Clinical and Epidemiological Relevance

The 199 documented articles reflect the high and gradual incidence of pandemic clones disseminated in Brazil and the increase in the proportion of infections that result in different clinical manifestations. Although it is currently part of the PAN-BR, no survey has yet been made of the MRSA rates recorded since its emergence in Brazil until today [15]. However, Brazil is part of an antimicrobial surveillance organization that acts at a global level, called SENTRY, which recorded that 38.7% of MRSA out of 17474 samples of S. aureus collected over the 20-year interval were from Latin America, including Brazilian sampling [126].

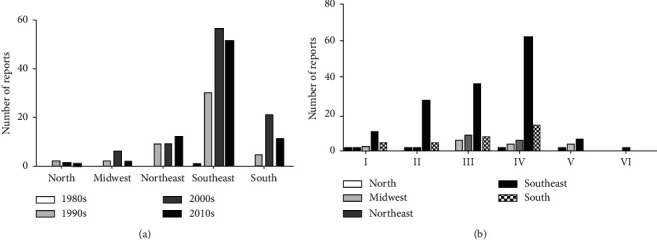

A quantitative survey of reports of MRSA infections specifically in Brazil collaborates to point out how emergency it is to apply the objectives of national epidemiological inspection and control programs [15]. Such a survey based on the regions of Brazil evidences which areas are most affected and which increase the country's epidemiological rates. Table 1 shows all the cities in Brazil and its respective references that were reported through publications that involved isolating MRSA from human samples. It is evident that the spread of clones and the consequences they bring to patients were gradually increased over the years and that all regions of the country have already been notified, with the southeast region being the most affected in all decades, followed by the south and northeast (Figure 5(a)). The high number of MRSA notifications in these regions was probably due to the fact that they are the most populated in Brazil, while the centralwest and north regions have lower demographic density [236]. In all regions, SCCmec type IV is the most prevalent, followed by III, II, and I, demonstrating that the clones that typically circulate in the community are the most prevalent in the country, followed by hospital clones (Figure 5(b)). Such data show how these virulent, highly adaptable, and multidrug-resistant clones pose risks to the population and show that such a survey contributes to the development of prevention and control assistance plans recently adopted in the country.

Table 1.

Reports of isolation of MRSA from the 1980s to the 2010s in Brazil.

| Region/location | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n a | Refsb | n | Refs | n | Refs | n | Refs | |

| North | ||||||||

| Belem | NRc | NR | 1 | [30] | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Manaus | NR | NR | 1 | [39] | 1 | [81] | NR | NR |

| Palmas | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1 | [127] |

|

| ||||||||

| Northeast | ||||||||

| Joao Pessoa | NR | NR | 2 | [27, 36] | NR | NR | 1 | [128] |

| Itabuna | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1 | [129] |

| Salvador | NR | NR | 1 | [130] | 4 | [60, 84, 131, 132] | NR | NR |

| Vitoria da Conquista | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 3 | [102, 114, 133] |

| Caico | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1 | [134] |

| Natal | NR | NR | 2 | [135, 136] | 2 | [137, 138] | 1 | [139] |

| Teresina | NR | NR | 2 | [33, 57] | NR | NR | 1 | [140] |

| Recife | NR | NR | NR | NR | 3 | [47, 141, 142] | 4 | [118, 143–145] |

| Fortaleza | NR | NR | 2 | [135, 136] | NR | NR | NR | NR |

|

| ||||||||

| South | ||||||||

| Viamao | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1 | [146] | NR | NR |

| Porto Alegre | NR | NR | 3 | [39, 147, 148] | 16 | [61, 69, 80, 82, 83, 88, 89, 98, 146, 149–155] | 4 | [156–159] |

| Santa Maria | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1 | [160] |

| Ponta Grossa | NR | NR | 1 | [161] | 1 | [161] | NR | NR |

| Maringa | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1 | [77] | NR | NR |

| Londrina | NR | NR | 2 | [135, 136] | NR | NR | 3 | [104, 105, 162] |

| Blumenau | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 2 | [110, 117] |

| Florianopolis | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1 | [154] | 1 | [117] |

| Curitiba | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1 | [163] | NR | NR |

|

| ||||||||

| Southeast | ||||||||

| Rio de Janeiro | 1 | 17 | 14 | [17, 28, 29, 34, 38, 39, 48–50, 53, 54, 56, 135, 136] | 24 | [29, 47, 64–66, 73, 83, 86, 87, 90–92, 95, 96, 99, 124, 151, 164–170] | 16 | [103, 112, 113, 115, 116, 125, 171–180] |

| Niteroi | NR | NR | 1 | [39] | NR | NR | 8 | [125, 181–187] |

| São Paulo | NR | NR | 5 | [31, 32, 39, 42, 188] | 13 | [72, 75, 85, 93, 151, 154, 189–195] | 12 | [106, 107, 109, 111, 119, 186, 196–201] |

| Carapicuiba | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1 | [202] | NR | NR |

| Barretos | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1 | [203] | NR | NR |

| Bauru | NR | NR | NR | NR | 5 | [63, 101, 204–206] | 1 | [108] |

| Ribeirao Preto | NR | NR | NR | NR | 2 | [97, 207] | 2 | [208, 209] |

| Botucatu | NR | NR | 1 | [55] | 3 | [62, 71, 210] | 4 | [14, 211–213] |

| Avare | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1 | [214] |

| Santo Andre | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1 | [215] | NR | NR |

| Campinas | NR | NR | 4 | [18, 37, 44, 216] | 2 | [97, 217] | 1 | [218] |

| Pouso Alegre | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1 | [219] |

| Uberaba | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1 | [220] | NR | NR |

| Uberlandia | NR | NR | 3 | [49, 50, 52] | 4 | [221–224] | 3 | [225–227] |

| Belo Horizonte | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1 | [67] |

| Vitoria | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1 | [228] |

|

| ||||||||

| Midwest | ||||||||

| Campo Grande | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1 | [229] |

| Goiania | NR | NR | NR | NR | 5 | [70, 76, 94, 230, 231] | 1 | [232] |

| Brasilia | NR | NR | 1 | [135, 136] | 1 | [154] | NR | NR |

|

| ||||||||

| Unknown | NR | NR | 4 | [51, 58, 233, 234] | 3 | [100, 193, 235] | NR | NR |

aNumbers of reports, breferences, cnonreported (NR).

Figure 5.

MRSA isolates and the types of SCCmec reported in Brazil. (a) Numbers of MRSA isolations per decade in the five regions of Brazil. (b) Numbers of types of SCCmec reported in the five regions of Brazil until 2019. The graphics program used to create the figure was GraphPad Prism.

1.6. Final Considerations

Considering case reports and field research included in this review, it is clear that MRSA is now present in the five regions of Brazil. It is also clear that Brazil has a large genetic diversity of MRSA, including multidrug-resistant and high virulent strains. Such diversity may increase if new SCCmec and variants are imported. In addition, it is important to note that the data indicated in this review are relevant but still limited concerning the subcontinental size of Brazil. Limitations may include an insufficient number of studies due to low government investment in research, lack of access to health services for the vulnerable population, and application of empirical antibiotic therapy ignoring established protocols, which undoubtedly results in underreporting of a relevant number of cases. This review reinforces problems related to the ability of bacteria to become resistant to antibiotics and their potential for spread, usually occurring in epidemic waves initiated by one or a few successful clones. Moreover, it contributes to an epidemiological study by mapping the spread of MRSA in Brazil, as there is still no monitoring system for these resistant strains or a specific antimicrobial surveillance system in Brazil. Strategies of control and monitoring should be increased in hospital and community environments to avoid the advance of spreading of successful clones as well as exporting or importing new strains of MRSA to Brazil.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) for the mastering fellowship of Mariana Moreira Andrade.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.David M. Z., Daum R. S. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology and clinical consequences of an emerging epidemic. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2010;23(3):616–687. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00081-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jevons M. P. “Celbenin”–resistant staphylococci. BMJ. 1961;1(5219):124–125. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5219.124-a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bulger R. J. A methicillin-resistant strain of Staphylococcus aureus. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1967;67(1):p. 81. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-67-1-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrett F. F., McGehee R. F., Finland M. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus at boston city hospital. New England Journal of Medicine. 1968;279(9):441–448. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196808292790901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deurenberg R. H., Stobberingh E. E. The evolution of Staphylococcus aureus. Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 2008;8(6):747–763. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ito T., Hiramatsu K., Oliveira D. C., et al. Classification of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec): guidelines for reporting novel SCCmec elements. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53(12):4961–4967. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00579-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson A. P., Pearson A., Duckworth G. Surveillance and epidemiology of MRSA bacteraemia in the UK. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2005;56(3):455–462. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ito T., Katayama Y., Hiramatsu K. Cloning and nucleotide sequence determination of the entire mec DNA of pre-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus N315. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1999;43(6):1449–1458. doi: 10.1128/AAC.43.6.1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ito T., Katayama Y., Asada K., et al. Structural comparison of three types of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec integrated in the chromosome in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2001;45(5):1323–1336. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.5.132310.1128/aac.45.5.1323-1336.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lakhundi S., Zhang K. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: molecular characterization, evolution, and epidemiology. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2018;31(4):1–103. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00020-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urushibara N., Aung M. S., Kawaguchiya M., Kobayashi N. Novel staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) type XIV (5A) and a truncated SCCmec element in SCC composite islands carrying speG in ST5 MRSA in Japan. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2019;75(1):46–50. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkz406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu J., Chen D., Peters B. M., et al. Staphylococcal chromosomal cassettes mec (SCCmec): a mobile genetic element in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2016;101:56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2016.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oliveira P. M. N. d., Buonora S. N., Souza C. L. P., et al. Surveillance of multidrug-resistant bacteria in pediatric and neonatal intensive care units in Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2019;52:1–7. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0205-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pereira Franchi E. P. L., Barreira M. R. N., Da Costa N. de S. L. M., et al. Molecular epidemiology of MRSA in the Brazilian primary health care system. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2018;24(3):339–347. doi: 10.1111/tmi.13192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brasil. Plano de Ação Nacional de Prevenção e Controle da Resistência Aos Antimicrobianos No Âmbito da Saúde Única 2018–2022 (PAN-BR) Brazil: Brasília Ministério da Saúde; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anvisa an de V. S. Programa Nacional de Prevenção e Controle de Gerência Geral de Tecnologia em Serviços de Saúde (PNPCIRAS) 2016–2020. 2016. http://file:///C:/Users/VAIO/Downloads/PNPCIRAS_2016.pdf.

- 17.Ramos R. L. B., Teixeira L. A., Ormonde L. R., et al. Emergence of mupirocin resistance in multiresistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates belonging to Brazilian epidemic clone III::B:A. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 1999;48(3):303–307. doi: 10.1099/00222615-48-3-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tresoldi A. T., Branchini M. L. M., Moreira Filho D. d. C., et al. Relative frequency of nosocomial microorganisms at unicamp university hospital from 1987 to 1994. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo. 1997;39(6):333–336. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46651997000600005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dowzicky M., Talbot G. H., Feger C., Prokocimer P., Etienne J., Leclercq R. Characterization of isolates associated with emerging resistance to quinupristin/dalfopristin (Synercid) during a worldwide clinical program. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2000;37(1):57–62. doi: 10.1016/S0732-8893(99)00154-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luh K.-T., Hsueh P.-R., Teng L.-J., et al. Quinupristin-dalfopristin resistance among gram-positive bacteria in Taiwan. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2000;44(12):3374–3380. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.12.3374-3380.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marty F. M., Yeh W. W., Wennersten C. B., et al. Emergence of a clinical daptomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolate during treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and osteomyelitis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2006;44(2):595–597. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.2.595-597.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meka V. G., Pillai S. K., Sakoulas G., et al. Linezolid resistance in Sequential Staphylococcus aureus Isolates associated with a T2500A mutation in the 23S rRNA gene and loss of a single copy of rRNA. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2004;190(2):311–317. doi: 10.1086/421471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rose W. E., Rybak M. J. Tigecycline: first of a new class of antimicrobial agents. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26(8):1099–1110. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.8.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maple P. A. C., Hamilton-Miller J. M. T., Brumfitt W. World-wide antibiotic resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. The Lancet. 1989;333(8637):537–540. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(89)90076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chambers H. F., DeLeo F. R. Waves of resistance: Staphylococcus aureus in the antibiotic era. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2009;7(9):629–641. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodríguez-Noriega E., Seas C., Guzmán-Blanco M., et al. Evolution of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones in Latin America. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2010;14(7):e560–e566. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freitas F. I. S., Guedes-Stehling E., Siqueira-Junior J. P. Resistance to gentamicin and related aminoglycosides in Staphylococcus aureus isolated in Brazil. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 1999;29(3):197–201. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coimbra M. V. D. S., Figueiredo A. M. S., Famiglietti A., et al. Spread of the Brazilian epidemic clone of a multiresistant MRSA in two cities in Argentina. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2000;49(2):187–192. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-49-2-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vivoni A. M., Diep B. A., de Gouveia Magalhaes A. C., et al. Clonal composition of Staphylococcus aureus isolates at a Brazilian university hospital: identification of international circulating lineages. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2006;44(5):1686–1691. doi: 10.1128/jcm.44.5.1686-1691.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amaral M. M., Coelho L. R., Flores R. P., et al. The predominant variant of the Brazilian epidemic clonal complex of methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus has an enhanced ability to produce biofilm and to adhere to and invade airway epithelial cells. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2005;192(5):801–810. doi: 10.1086/432515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sader H. S., Pignatari A. C., Hollis R. J., Jones R. N. Evaluation of interhospital spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Sao paolo, Brazil, using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of chromosomal DNA. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology. 1994;15(8):p. 508. doi: 10.1017/S019594170001011010.1086/646921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sader H. S., Pignatari A. C., Hollis R. J., Leme I., Jones R. N. Oxacillin- and quinolone-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Sao Paulo, Brazil: a multicenter molecular epidemiology study. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 1993;14(5):260–264. doi: 10.2307/3014836310.1086/646731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Soares M. J. S., Tokumaru-Miyazaki N. H., Noleto A. L. S., Figueired A. M. S. Enterotoxin production by Staphylococcus aureus clones and detection of Brazilian epidemic MRSA clone (III::B:A) among isolates from food handlers. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 1997;46(3):214–221. doi: 10.1099/00222615-46-3-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Falcao M. H. L., Texeira L. A., Ferreira-Carvalho B. T., Borges-Neto A. A., Figueiredo A. M. S. Occurrence of methicillin-resistant and -susceptible Staphylococcus aureus within a single colony contributing to MRSA mis-identification. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 1999;48(6):515–521. doi: 10.1099/00222615-48-6-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nogueira M., Marinsalta N., Roussell M., Notario R. Importance of hand germ contamination in health-care workers as possible carriers of nosocomial infections. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2001;43(3):149–152. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652001000300006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santos Filho L., Sader H. S., Bortolotto V. I., Gontijo Filho P. P., Pignatari A. C. Analysis of the clonal diversity of Staphylococcus aureus methicillin-resistant strains isolated at João Pessoa, state of Paraíba, Brazil. Memórias Do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 1996;91(1):101–105. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02761996000100018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beretta A. L. R. Z., Trabasso P., Stucchi R. B., Moretti M. L. Use of molecular epidemiology to monitor the nosocomial dissemination of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a University Hospital from 1991 to 2001. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 2004;37(9):1345–1351. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2004000900009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tórtora J. C., de Sousa T. L., Lourenço M. C., Lopes H. R. Nosocomial occurrence of enterotoxigenic multiresistant Staphylococcus strains in Rio de Janeiro. Revista Latinoamericana de Microbiología. 1996;38(1):1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teixeira L. A., Resende C. A., Ormonde L. R., et al. Geographic spread of epidemic multiresistant Staphylococcus aureus clone in Brazil. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1995;33(9):2400–2404. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2400-2404.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mebinda I., Quitoco Z., Ramundo M. S., et al. First report in South America of companion animal colonization by the USA1100 Clone of Staphylococcus aureus (ST30) and by the European clone of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius (ST71) BMC Research Notes. 2013;27(6):p. 336. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Sousa M. A., Sanches I. S., Ferro M. L., et al. Intercontinental spread of a multidrug-resistant methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1998;36(9):2590–2596. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2590-2596.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aires de Sousa M., Miragaia M., Santos Sanches I., et al. Three-year assessment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones in Latin America from 1996 to 1998. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2001;39(6):2197–2205. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.6.219710.1128/jcm.39.6.2197-2205.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Corso A., Sanches I. S., De Sousa M. A., Rossi A., De Lencastre H., de Lencastre H. Spread of a methicillin-resistant and multiresistant epidemic clone of Staphylococcus aureus in Argentina. Microbial Drug Resistance. 1998;4(4):277–288. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1998.4.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Branchini M. L. M., Morthland V. H., Tresoldi A. T., Von Nowakonsky A., Dias M. B. S., Pfaller M. A. Application of genomic DNA subtyping by pulsed field gel electrophoresis and restriction enzyme analysis of plasmid DNA to characterize methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from two nosocomial outbreaks. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 1993;17(4):275–281. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(93)90036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oliveira D. C., Tomasz A., de Lencastre H. The evolution of pandemic clones of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: identification of two ancestral genetic backgrounds and the Associated mec elements. Microbial Drug Resistance. 2001;7(4):349–361. doi: 10.1089/10766290152773365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oliveira D., Santos-Sanches I., Mato R., et al. Virtually all methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections in the largest Portuguese teaching hospital are caused by two internationally spread multiresistant strains: the “Iberian” and the “Brazilian” clones of MRSA. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 1998;4(7):373–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1998.tb00081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miranda O. P. De, Silva-carvalho M. C., Ribeiro A., et al. Emergence in Brazil of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates carrying SCC mec IV that are related genetically to the USA800 clone. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2007;13(12):1165–1172. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bastos M. C. F., Mondino P. J. J., Azevedo M. L. B., Santos K. R. N., Giambiagi-deMarval M. Molecular characterization and transfer among Staphylococcus strains of a plasmid conferring high-level resistance to mupirocin. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 1999;18(6):393–398. doi: 10.1007/s100960050306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Santos K. R. N., Teixeira L. M., Leal G. S., Fonseca L. S., Gontijo Filho P. P. DNA typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: isolates and factors associated with nosocomial acquisition in two Brazilian university hospitals. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 1999;48(1):17–23. doi: 10.1099/00222615-48-1-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.dos Santos K. R. N., de Souza Fonseca L., Filho P. P. G. Emergence of high-level mupirocin resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from Brazilian university hospitals. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. 1996;17(12):813–816. doi: 10.1086/647243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Korn G. P., Martino M. D. V., Mimica I. M., Mimica L. J., Chiavone P. A., Musolino L. R. d. S. High frequency of colonization and absence of identifiable risk factors for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in intensive care units in Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2001;5(1):1–7. doi: 10.1590/S1413-86702001000100001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sadoyama G., Gontijo Filho P. P. Risk factors for methicillin resistant and sensitive Staphylococcus aureus infection in a Brazilian university hospital. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2000;4(3):135–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moraes B. A. d., Cravo C. A. N., Loureiro M. M., Solari C. A., Asensi M. D. Epidemiological analysis of bacterial strains involved in hospital infection in a university hospital from Brazil. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo. 2000;42(4):201–207. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652000000400005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Loureiro M., Moraes B. d., Quadra M., Pinheiro G., Suffys P., Asensi M. Molecular epidemiology of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from newborns in a hospital in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Memórias Do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2000;95(6):777–782. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762000000600005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pereira V. C., Riboli D. F. M., da Cunha M. d. L. R. d. S., LR de S. Characterization of the clonal profile of MRSA isolated in neonatal and pediatric intensive care units of a University Hospital. Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials. 2014;13(1):1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12941-014-0050-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Teixeira L. A., Lourenço M. C. S., Figueiredo A. M. S. Emergence of a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clone related to the Brazilian epidemic clone III::B:A causing invasive disease among AIDS patients in a Brazilian hospital. Microbial Drug Resistance. 1996;2(4):393–399. doi: 10.1089/mdr.1996.2.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Soares M. J. D. S., Teixeira L. A., Nunes M. D. R., Carvalho M. C. D. S., Ferreira-Carvalho B. T., Figueiredo A. M. S. Analysis of different molecular methods for typing methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates belonging to the Brazilian epidemic clone. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2001;50(8):732–742. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-50-8-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.dos Santos Soares M. J., da Silva-Carvalho M. C., Ferreira-Carvalho B. T., Figueiredo A. M. S. Spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus belonging to the Brazilian epidemic clone in a general hospital and emergence of heterogenous resistance to glycopeptide antibiotics among these isolates. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2000;44(4):301–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reinert C., McCulloch J. A., Watanabe S., Ito T., Hiramatsu K., Mamizuka E. M. Type IV SCCmec found in decade old Brazilian MRSA isolates. Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2008;12(3):1995–1998. doi: 10.1590/s1413-86702008000300010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brites C., Silva N., Sampaio- Sá M. Temporal evolution of the prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a tertiary hospital in Bahia, Brazil: a nine-year evaluation study. Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2006;10(4):235–238. doi: 10.1590/S1413-86702006000400003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Perez L. R. R., D’azevedo P. A. Clonal types and antimicrobial resistance profiles of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from hospitals in south Brazil. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo. 2008;50(3):135–137. doi: 10.1590/s0036-46652008000300001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martins A., Moraes Riboli D. F., Moraes Riboli D. F., Cataneli Pereira V. Molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from a Brazilian university hospital. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2014;18(3):331–335. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rodrigues M. V. P., Branco Fortaleza C. M. C., Martins Souza C. S., Teixeira N. B., Ribeiro de Souza da Cunha M. d. L. Genetic determinants of methicillin resistance and virulence among Staphylococcus aureus isolates recovered from clinical and surveillance cultures in a Brazilian teaching hospital. ISRN Microbiology. 2012;2012(975143):1–4. doi: 10.5402/2012/975143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Melo M. C. N., Silva-Carvalho M. C., Ferreira R. L., et al. Detection and molecular characterization of a gentamicin-susceptible, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) clone in Rio de Janeiro that resembles the New York/Japanese clone. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2004;58(4):276–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Caboclo R. M. F., Cavalcante F. S., Iorio N. L. P., et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Rio de Janeiro hospitals: dissemination of the USA400/ST1 and USA800/ST5 SCCmec type IV and USA100/ST5 SCCmec type II lineages in a public institution and polyclonal presence in a private one. American Journal of Infection Control. 2013;41(3):e21–e26. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rozenbaum R., Silva-Carvalho M. C., Souza R. R., et al. Molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus disseminated in a home care system. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology. 2006;27(10):1041–1050. doi: 10.1086/507921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dabul A. N. G., Camargo I. L. B. C. Molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus resistant to tigecycline and daptomycin isolated in a hospital in Brazil. Epidemiology and Infection. 2014;142(3):479–483. doi: 10.1017/S0950268813001325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oliveira D. C., Tomasz A., de Lencastre H. Secrets of success of a human pathogen: molecular evolution of pandemic clones of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2002;2(3):180–189. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00227-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Becker A. P., Santos O., Castrucci F. M., Dias C., D’azevedo P. A. First report of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus cordobes/chilean clone involved in nosocomial infections in Brazil. Epidemiology and Infection. 2012;140(8):1372–1375. doi: 10.1017/S095026881100210X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lamaro-cardoso J., de Lencastre H., Kipnis A., et al. Molecular epidemiology and risk factors for nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant S. aureus in infants attending day care centers in Brazil. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2009;47(12):3991–3997. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01322-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bonesso M. F., Marques S. A., Camargo C. H., Fortaleza C. M. C. B., Cunha M. d. L. R. d. S. d. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in non-outbreak skin infections. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology. 2014;45(4):1401–1407. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822014000400034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Carmo M. S., Inoue F., Andrade S. S., et al. New multilocus sequence typing of MRSA in São Paulo, Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 2011;44(10):1013–1017. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2011007500114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chamon R. C., Ribeiro S. d. S., da Costa T. M., Nouér S. A., dos Santos K. R. N. Complete substitution of the Brazilian endemic clone by other methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus lineages in two public hospitals in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2017;21(2):185–189. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2016.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rodríguez-Noriega E., Seas C. The changing pattern of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones in Latin America: implications for clinical practice in the region. Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2010;14(2):87–96. doi: 10.1590/S1413-86702010000800004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Trindade P. d. A., Pacheco R. L., Costa S. F., et al. Prevalence of SCCmec type IV in nosocomial bloodstream isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2005;43(7):3435–3437. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.7.343510.1128/jcm.43.7.3435-3437.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vieira M. A., Minamisava R., Pessoa-Júnior V., et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage in neonates and children attending a pediatric outpatient clinics in Brazil. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2014;18(1):42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Prates K. A., Torres A. M., Garcia L. B., Ogatta S. F., Cardoso C. L., Bronharo Tognim M. C. Nasal carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in university students. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2010;14(3):316–318. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2012.08.01810.1590/s1413-86702010000300021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yamada Ogatta E. E. Genetic analysis of community isolates of Staphylococcus aureus in Western. Journal of Hospital Infection. 1993;25(2):97–108. doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(93)90100-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nimmo G. R., Coombs G. W. Community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in Australia. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 2008;31(5):401–410. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ribeiro A., Dias C., Silva-carvalho M. C., et al. First report of infection with community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in south America. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2005;43(4):1985–1988. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.4.198510.1128/jcm.43.4.1985-1988.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Egido J. M., Barros M. L. Preliminary study of community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus infection in manaus hospital, amazonia region, Brazil. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2003;36(6):707–709. doi: 10.1590/S0037-86822003000600011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Razera F., Stefani S. D., Bonamigo R. R., Olm G. S., Dias C. A. G., Narvaez G. A. CA-MRSA em furunculose: relato de caso do sul do Brasil. Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia. 2009;84(5):515–518. doi: 10.1590/S0365-05962009000500011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ribeiro A., Coronado A. Z., Silva-carvalho M. C., et al. Detection and characterization of international community-acquired infections by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones in Rio de Janeiro and Porto Alegre cities causing both community- and hospital-associated diseases. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2007;59(3):339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.de Vasconcellos Â. G., Leal R. D., Silvany-Neto A., Nascimento-Carvalho C. M. Oxacillin or cefalotin treatment of hospitalized children with cellulitis. Japanese Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2012;65(1):7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vola M. E., Moriyama A. S., Lisboa R., et al. Prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in ocular infections. Arquivos Brasileiros de Oftalmologia. 2013;76(6):350–353. doi: 10.1590/S0004-27492013000600006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Fortes C. Q., Espanha C. A., Bustorff F. P., et al. First reported case of infective endocarditis caused by community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus not associated with healthcare contact in Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2008;12(6):541–543. doi: 10.1590/S1413-86702008000600020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.de Araújo B. E. S., Borchert J. M., Manhães P. G., et al. A rare case of pyomyositis complicated by compartment syndrome caused by ST30-staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec type IV methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2010;28(4):e3–e537. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gelatti L. C., Sukiennik T., Becker A. P., et al. Sepse por Staphylococus aureus resistente à meticilina adquirida na comunidade no sul do Brasil. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2009;42(4):458–460. doi: 10.1590/S0037-86822009000400019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gelatti L. C., Bonamigo R. R., Inoue F. M., et al. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carrying SCCmec type IV in southern Brazil. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2013;46(1):34–38. doi: 10.1590/0037-868213022013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rozenbaum R., Sampaio M. G., Batista G. S., et al. The first report in Brazil of severe infection caused by community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 2009;42(8):756–760. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2009005000007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Brust T., Costa T. M. d., Amorim J. C., Asensi M. D., Fernandes O., Aguiar-Alves F. Hospital-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carrying the PVL gene outbreak in a Public Hospital in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology. 2013;44(3):865–868. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822013000300031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Souza R. R., Coelho L. R., Botelho A. M. N., et al. Biofilm formation and prevalence of lukF-pv, seb, sec and tst genes among hospital- and community-acquired isolates of some international methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus lineages. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2009;15(2):203–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Garcia C. P., Rosa J. F., Cursino M. A., et al. Non-multidrug-resistant, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a neonatal unit. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 2014;33(10):e252–e259. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lamaro-cardoso J., Castanheira M., de Oliveira R. M., et al. Carriage of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in children in Brazil. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2007;57(4):467–470. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ferreira F. A., Souza R. R., Bonelli R. R., Américo M. A., Fracalanzza S. E. L., Figueiredo A. M. S. Comparison of in vitro and in vivo systems to study ica-independent Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2012;88(3):393–398. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Silva-Carvalho M. C., Bonelli R. R., Souza R. R., et al. Emergence of multiresistant variants of the community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus lineage ST1-SCCmecIV in 2 hospitals in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2009;65(3):300–305. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cury G. G., Mobilon C., Stehling E. G., et al. Molecular typing of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains isolated in two metropolitan areas of São Paulo State, southeast Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2009;13(3):165–169. doi: 10.1590/S1413-86702009000300002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Scribel L. V., Silva-Carvalho M. C., Souza R. R., et al. Clinical and molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carrying SCCmecIV in a university hospital in Porto Alegre, Brazil. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2009;65(4):457–461. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Schuenck R. P., Nouér S. A., de Oliveira Winter C., et al. Polyclonal presence of non-multiresistant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates carrying SCCmec IV in health care-associated infections in a hospital in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2009;64(4):434–441. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Beltrame C. O., Botelho A. M. N., Silva-Carvalho M. C., et al. Restriction modification (RM) tests associated to additional molecular markers for screening prevalent MRSA clones in Brazil. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 2012;31(8):2011–2016. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1534-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rodrigues M. V. P., Fortaleza C. M. C. B., Riboli D. F. M., Rocha R. S., Rocha C., Cunha M. d. L. R. d. S. d. Molecular epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a burn unit from Brazil. Burns. 2013;39(6):1242–1249. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Campos G. B., Souza S. G., Lob O T. N., et al. Isolation, molecular characteristics and disinfection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from ICU units in Brazil. The New Microbiologica. 2012;35(2):183–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cavalcante F. S., Pinheiro M. V., Ferreira D. d. C., et al. Characteristics of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in patients on admission to a teaching hospital in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. American Journal of Infection Control. 2017;45(11):1190–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Oliveira C. F. d., Morey A. T., Santos J. P., et al. Molecular and phenotypic characteristics of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from hospitalized patients. The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries. 2015;9(7):743–751. doi: 10.3855/jidc.5868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Duarte F. C., Tavares E. R., Danelli T., et al. Disseminated clonal complex 5 (CC5) methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus SCCmec type ii in a tertiary hospital of southern Brazil. Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo. 2018;60:5–9. doi: 10.1590/S1678-9946201860032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.de Oliveira L. M., Van Der Heijden I. M., Golding G. R., et al. Staphylococcus aureus isolates colonizing and infecting cirrhotic and liver-transplantation patients: comparison of molecular typing and virulence factors. BMC Microbiology. 2015;15(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0598-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Van Der Heijden I. M., de Oliveira L. M., Brito G. C., et al. Virulence and resistance profiles of MRSA isolates in pre- and post-liver transplantation patients using microarray. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2016;65(10):1060–1073. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.da Silveira M., da Cunha M. d. L. R. d. S., LR de S., de Souza C. S. M., Correa A. A. F., Fortaleza C. M. C. B. Nasal colonization with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among elderly living in nursing homes in Brazil: risk factors and molecular epidemiology. Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials. 2018;17(1):1–5. doi: 10.1186/s12941-018-0271-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Caiaffa-filho H. H., Trindade P. A., Gabriela da Cunha P., et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carrying SCCmec type II was more frequent than the Brazilian endemic clone as a cause of nosocomial bacteremia. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2013;76(4):518–520. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.McCulloch J. A., Silveira A. C. d. O., Lima Moraes A. d. C., et al. Complete genome sequence of Staphylococcus aureus FCFHV36, a methicillin-resistant strain heterogeneously resistant to vancomycin. Genome Announcements. 2015;3(4):4–5. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00893-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Rossi F., Diaz L., Wollam A., et al. Transferable vancomycin resistance in a community-associated MRSA lineage. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014;370(16):1524–1531. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1303359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ferreira F. A., Souza R. R., de Sousa Moraes B., et al. Impact of agr dysfunction on virulence profiles and infections associated with a novel methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) variant of the lineage ST1-SCCmec IV. BMC Microbiology. 2013;13(1):93–12. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Guimarães M. A., Ramundo M. S., Américo M. A., et al. A comparison of virulence patterns and in vivo fitness between hospital- and community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus related to the USA400 clone. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 2015;34(3):497–509. doi: 10.1007/s10096-014-2253-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Carvalho S. P. d., Almeida J. B. d., Andrade Y. M. F. S., et al. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carrying SCC mec type IV and V isolated from healthy children attending public daycares in northeastern Brazil. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2017;21(4):464–467. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lima D. F., Brazão N. B. V., Folescu T. W., et al. Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) gene carriage among Staphylococcus aureus strains with SCCmec types I, III, IV, and V recovered from cystic fibrosis pediatric patients in Brazil. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2014;78(1):59–62. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zuma A. V. P., Lima D. F., Assef A. P. D. A. C., Marques E. A., Leão R. S. Molecular characterization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from blood in Rio de Janeiro displaying susceptibility profiles to non-β-lactam antibiotics. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology. 2017;48(2):237–241. doi: 10.1016/j.bjm.2016.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Silveira A. C. O., Cunha G. R., Caierão J., de Cordova C. M., d’Azevedo P. A. MRSA from Santa Catarina State, Southern Brazil: intriguing epidemiological differences compared to other Brazilian regions. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2015;19(4):384–389. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Soares C. R. P., de Lira C. R., Cunha M. A. H., et al. Prevalence of nasal colonization by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in outpatients living with HIV/AIDS in a Referential Hospital of the Northeast of Brazil. BMC Research Notes. 2018;11(794):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-3899-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zanella R. C., Brandileone M. C. d. C., Almeida S. C. G., et al. Nasopharyngeal carriage of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Staphylococcus aureus in a Brazilian elderly cohort. PLoS One. 2019;14(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221525.e0221525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Devriese L. A., Damme L. R., Fameree L. Methicillin (Cloxacillin)-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from bovine mastitis cases. Zentralblatt für Veterinärmedizin Reihe B. 1972;19(7):598–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.1972.tb00439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Van Rijen M. M. L., Van Keulen P. H., Kluytmans J. A. Increase in a Dutch hospital of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus related to animal farming. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2008;46(2):261–263. doi: 10.1086/524672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Huijsdens X. W., Dijke B. J. v., Spalburg E., et al. Community-acquired MRSA and pig-farming. Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials. 2006;5(26):1–4. doi: 10.1186/1476-0711-5-Received10.1186/1476-0711-5-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Armand-Lefevre L., Ruimy R., Andremont A. Clonal comparison of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from healthy pig farmers, human controls, and pigs. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005;11(5):711–714. doi: 10.3201/eid1105.040866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Lima D. F., Cohen R. W., Rocha G. A., Albano R. M., Marques E. A., Leão R. S. Genomic information on multidrug-resistant livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 isolated from a Brazilian patient with cystic fibrosis. Memórias Do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2017;112(1):79–80. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760160342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Neto E. D. A., Pereira R. F. A., Snyder R. E., et al. Emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from clonal complex 398 with no livestock association in Brazil. Memórias Do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2017;112(9):647–649. doi: 10.1590/0074-02760170040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Diekema D. J., Pfaller M. A., Shortridge D., Zervos M., Jones R. N. Twenty-year trends in antimicrobial susceptibilities among Staphylococcus aureus from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 2019;6(1):S47–S53. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofy270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Perim M. C., Borges J. d. C., Celeste S. R. C., et al. Aerobic bacterial profile and antibiotic resistance in patients with diabetic foot infections. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2015;48(5):546–554. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0146-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Barreto H. M., Fontinele F. C., Oliveira A. P. De, et al. Phytochemical prospection and modulation of antibiotic activity in vitro by lippia origanoides H. B. K. in methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. BioMed Research International. 2014;2014:7. doi: 10.1155/2014/305610.305610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Assis D. A. M., Rezende R. P., Dias J. C. T. Use of metagenomics and isolation of actinobacteria in Brazil’s atlantic rainforest soil for antimicrobial prospecting. ISRN Biotechnology. 2014;2014:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2014/909601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Gomes R. T., Lyra T. G., Alves N. N., Caldas R. M., Barberino M.-G., Nascimento-Carvalho C. M. Methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus infection among children. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2013;17(5):573–578. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Nascimento-carvalho C. M., Lyra T. G., Alves N. N., Caldas R. M., Barberino M. G. Resistance to methicillin and other antimicrobials among community-acquired and nosocomial Staphylococcus aureus strains in a pediatric teaching hospital in salvador, northeast Brazil. Microbial Drug Resistance. 2008;14(2):129–131. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2008.0790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Paixão V. A., Barros T. F., Mota C. M. C., Moreira T. F., Santana M. A., Reis J. N. Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of respiratory pathogens in patients with cystic fibrosis. Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2006;14(4):406–409. doi: 10.1590/S1413-86702010000400016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.de Carvalho S. P., de Almeida J. B., Andrade Y. M. F. S., et al. Molecular characteristics of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from hospital and community environments in northeastern Brazil. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2019;23(2):134–138. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2019.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Almeida G. C. M., dos Santos M. M., Lima N. G. M., Cidral T. A., Melo M. C. N., Lima K. C. Prevalence and factors associated with wound colonization by Staphylococcus spp. and Staphylococcus aureus in hospitalized patients in inland northeastern Brazil: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2014;14(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Novak F. R., da Silva A. V., Figueiredo A. M. S., Hagler A. N. Contamination of expressed human breast milk with an epidemic multiresistant Staphylococcus aureus clone. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2000;49(12):1109–1117. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-49-12-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Novak F., Almeida J., Warnken M., Ferreira-Carvalho B., Hagler A. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in human milk. Memórias Do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2000;95(1):29–33. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762000000100003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Sousa-Júnior F. C. d., Silva-Carvalho M. C., Fernandes M. J. B. C., et al. Genotyping of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates obtained in the Northeast region of Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 2009;42(10):877–881. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2009005000018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.de Sousa F. C., Nunes É. D. F., do Nascimento E. D., de Oliveira S. M., de Melo M. C. N., Fernandes M. J. d. B. C. Prevalência de Staphylococcus spp resistentes à meticilina isolados em uma maternidade escola da Cidade de Natal, Estado do Rio Grande do Norte. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2009;42(2):179–182. doi: 10.1590/S0037-86822009000200017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Sousa Júnior F. C. d., Néri G. d. S., Silva A. K., et al. Evaluation of different methods for detecting methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus isolates in a university hospital located in the northeast of Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology. 2010;41(2):316–320. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822010000200009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Oliveira D. M. d. S., Andrade D. F. R. d., Ibiapina A. R. d. S., et al. High rates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonisation in a Brazilian intensive care unit. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing. 2018;49:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Silva E. C. B. F. d., Antas M. d. G. C., Neto A. M. B., Melo F. L. d., de Melo M. A. V., Maciel M. A. V. Prevalence and risk factors for Staphylococcus aureus in health care workers at a University Hospital of Recife-PE. Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2008;12(6):504–508. doi: 10.1590/S1413-86702008000600012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Cavalcanti S. M. M., França E. R. d., Cabral C., et al. Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus introduced into intensive care units of a university hospital. Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2005;9(1):56–63. doi: 10.1590/S1413-86702005000100010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Caraciolo F. B., Maciel M. A. V., Santos J. B. d., Rabelo M. A., Magalhães V. Antimicrobial resistance profile of Staphylococcus aureus isolates obtained from skin and soft tissue infections of outpatients from a university hospital in Recife -PE, Brazil. Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia. 2012;87(6):857–861. doi: 10.1590/S0365-05962012000600006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Rabelo M. A., Bezerra Neto A. M., Loibman S. O., et al. The occurrence and dissemination of methicillin and vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus in samples from patients and health professionals of a university hospital in recife, State of Pernambuco, Brazil. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2014;47(4):437–446. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0071-2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Pereira J. N. d. P., Rabelo M. A., Lima J. L. d. C., Neto A. M. B., Lopes A. C. d. S., Maciel M. A. V. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of resistance to macrolides, lincosamides and type B streptogramin of clinical isolates of Staphylococcus spp. of a university hospital in Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2016;20(3):276–281. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Gelatti L. C., Bonamigo R. R., Becker A. P., Eidt L. M., Ganassini L., d’ Azevedo P. A. Phenotypic, molecular and antimicrobial susceptibility assessment in isolates from chronic ulcers of cured leprosy patients: a case study in Southern Brazil. Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia. 2014;89(3):404–408. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20142688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Senna J. P. M., Pinto C. A., Mateos S., Quintana A., Santos D. S. Spread of a dominant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) clone between Uruguayan and South of Brazil Hospitals. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2003;53(2):156–157. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2002.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Sandri A. M., Dalarosa M. G., Alcântara L. R. d., Elias L. d. S., Zavascki A. P. Reduction in inddence of nosocomial methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection in an intensive care unit: role of treatment with mupirocin ointment and chlorhexidine baths for nasal carriers of MRSA. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology. 2006;27(2):185–187. doi: 10.1086/500625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Senna J. P. M., Pinto C. A., Bernardon D. R., et al. Identification of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus among care-workers and patients in an emergency hospital. Journal of Hospital Infection. 2003;54(2):165–167. doi: 10.1016/S0195-6701(02)00386-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Santos H. B., Machado D. P., Camey S. A., Kuchenbecker R. S., Barth A. L., Wagner M. B. Prevalence and acquisition of MRSA amongst patients admitted to a tertiary-care hospital in Brazil. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2010;10(1):p. 328. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Salomao R., Rosenthal V. D., Grimberg G., et al. Device-associated infection rates in intensive care units of Brazilian hospitals: datos de la Comunidad Científica Internacional de Control de Infecciones Nosocomiales. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública. 2008;24(3):195–202. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892008000900006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Reiter K. C., Machado A. B. M. P., Freitas A. L. P. d., Barth A. L., Freitas P. De, Barth A. L. High prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with SCCmec type III in cystic fibrosis patients in southern, Brazil. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2010;43(4):377–381. doi: 10.1590/S0037-86822010000400008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]