Abstract

The biological and clinical heterogeneity of neuroblastoma (NB) demands novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets in order to drive the most appropriate treatment for each patient. Hypoxia is a condition of low-oxygen tension occurring in poorly vascularized tumor tissues. In this study, we aimed to assess the role of hypoxia in the pathogenesis of NB and at developing a new clinically relevant hypoxia-based predictor of outcome. We analyzed the gene expression profiles of 1882 untreated NB primary tumors collected at diagnosis and belonging to four existing data sets. Analyses took advantage of machine learning methods. We identified NB-hop, a seven-gene hypoxia biomarker, as a predictor of NB patient prognosis, which is able to discriminate between two populations of patients with unfavorable or favorable outcome on a molecular basis. NB-hop retained its prognostic value in a multivariate model adjusted for established risk factors and was able to additionally stratify clinically relevant groups of patients. Tumors with an unfavorable NB-hop expression showed a significant association with telomerase activation and a hypoxic, immunosuppressive, poorly differentiated, and apoptosis-resistant tumor microenvironment. NB-hop defines a new population of NB patients with hypoxic tumors and unfavorable prognosis and it represents a critical factor for the stratification and treatment of NB patients.

Keywords: neuroblastoma, hypoxia, prognosis, cell immortalization, therapeutic target

1. Introduction

Neuroblastoma (NB) is a common extracranial solid tumor of the developing sympathetic nervous system, which accounts for roughly 5% of all diagnosed pediatric cancers [1]. Patients with localized tumors, defined as low or intermediate risk, do not require intensive therapeutic treatment, as, in most cases, the tumor regresses spontaneously. For such patients, surgery is performed when possible and chemotherapy is only considered for symptomatic tumors or for tumor masses growing after surgery [1,2]. On the contrary, patients with disseminated tumors, defined as high-risk, undergo intensive treatment that includes different phases: induction based on chemotherapy at maximally tolerated doses, local treatment with surgery and radiotherapy, consolidation with high dose chemotherapy and peripheral blood stem cells rescue, maintenance based on a differentiating agent (cis-retinoic acid) and, more recently, on immunotherapy targeting the expression of disialoganglioside (GD2) on NB cells. Despite this aggressive treatment, almost 50% of high-risk NB patients are refractory to therapy, relapse, and die [1].

Efforts to identify prognostic biomarkers from the genomic interrogation of NB tumors have been made with the aim of improving patient stratification and providing novel therapeutic targets [1,2]. Molecular signatures are becoming increasingly important tools for assisting clinicians in prognosis assessment and therapeutic decisions, because they can be used for accurately predicting patient outcome, relapse, or response to therapy, and also be instrumental for refining patient risk stratification, optimizing treatment, and reducing unnecessary therapy related toxicity [3,4,5,6]. For these purposes, the gene expression profiles of a large number of primary tumor specimens of NB patients have been published in distinct data sets becoming available to the scientific community [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. However, a large-scale expression study of NB tumors has not been previously carried out because different technologies use different proprietary annotations to identify transcripts. The integration of the distinct data sets into one merged data set would enable an unbiased and robust prediction analysis because data set may be split into two large training and test sets. As a consequence, the availability of a large number of gene expression profiles coupled with patient characteristics may enable the stratification of subgroups of patients that are notoriously difficult to analyze with a low number of cases.

The importance of hypoxia in conditioning the aggressiveness of tumors, including NB, is documented by an extensive literature [14,15,16,17]. A variety of techniques have been described to measure intratumor hypoxia including polarographic electrodes, fiber-optic probes, and positron emission tomography, but there is no consensus on the most appropriate approach to use [18]. The identification of an accurate hypoxia predictor may be instrumental for discriminating diagnosis patients who will potentially benefit of an anti-hypoxia therapy, thus preventing treatment-associated damage elicited by unnecessary therapies. We have previously used a biology-driven approach to assess the hypoxic status of NB tumors, consisting in the analysis of the gene expression profile of NB cell lines cultured under hypoxic and normoxic conditions, and identified an 11-probe set hypoxia signature that was able to accurately predict NB patient outcome [19]. However, application of this signature in a large multiplatform study in NB has never been evaluated.

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a heterogeneous milieu that is composed by neoplastic, stromal, endothelial, and infiltrating immune cells [20]. The functional interaction among different TME components is critical to determine the development and progression of several types of cancers, including NB [21,22]. Unmasking the altered molecular mechanisms in a hypoxic NB TME may be instrumental to identify novel therapeutic targets and pathways that are involved in NB tumor progression and to design novel personalized therapies for NB patients who have low probability to survive with actual treatment strategies. Hypoxia was reported to strongly affect the TME by altering important biological processes, including tumor cell differentiation, survival, migration, and resistance to therapy, and influencing the nature and function of the immune cell infiltrate [14,23]. However, the molecular mechanisms and biological effectors that are involved in NB hypoxic TME have been only partially elucidated.

Telomere maintenance mechanisms (TMM) are adopted by tumor cells to prevent telomere shortening and acquire immortality and they represent a malignant hallmark of several cancer cells [24]. Telomerase is a complex ribonucleic reverse transcriptase that is responsible for telomere maintenance by synthesizing telomeric DNA repeats at the 3′ ends of linear chromosomes [24]. The catalytic subunit of the human telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) is a key component of the telomerase complex and it is detectable in over 90% of human cancers [25]. Alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT) is an intra-telomeric recombination mechanism that may be employed by tumor cells to maintain telomere lengthening independently by telomerase activation [24]. Alterations found to be responsible for TMM in tumor cells include TERT rearrangement, somatic mutations of the TERT promoter, ALT, epigenetic changes, and amplification of TERT gene [24]. Despite the large number of publications reporting the critical role of TMM in different diseases, the mechanisms of telomerase regulation remain mostly unknown [26,27]. Ackermann and coworkers have recently shown the unfavorable prognostic impact of TMM in combination with RAS and/or p53 pathway mutations in NB and the correlation of high expression levels of the TERT gene with TMM in a large set of NB specimens [13].

In this study, we aimed at assessing the role of hypoxia in the pathogenesis of NB by analyzing the molecular mechanisms and biological effectors that are involved in NB hypoxic TME and at dissecting the prognostic value of a new hypoxia-based predictor in a large multicenter and multiplatform study. Our results show the unfavorable prognostic value of hypoxia in a large number of patients and the ability of hypoxia to additionally stratify clinically relevant groups of NB patients. Furthermore, our results reveal the deregulation of specific biological processes and pathways affecting NB TME.

2. Results

2.1. Collection of the Gene Expression Profile of NB Primary Tumors and Patient Characteristics

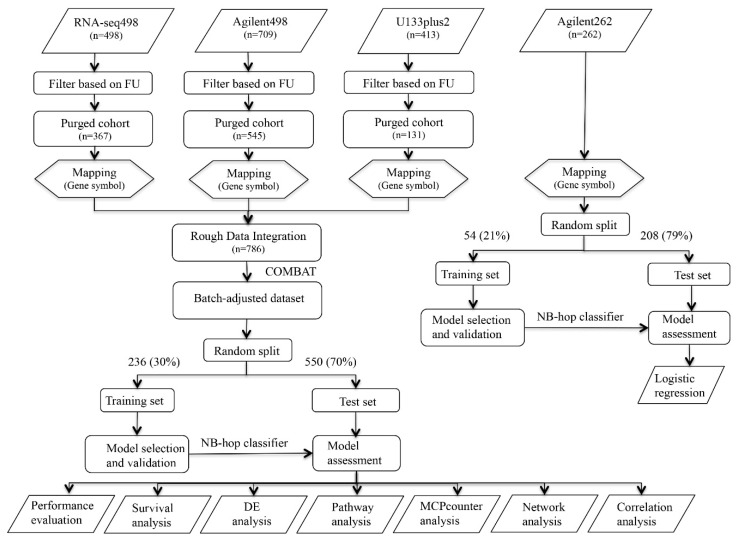

Analyses were carried out using the 11-probe set signature to assess the role of hypoxia in the pathogenesis of NB and to dissect the prognostic value of a new hypoxia-based predictor in a large multicenter and multiplatform study [19]. To these aims, we collected the gene expression profile of 1882 NB tumor specimens covering the entire spectrum of the disease included into four publicly available data sets (RNA-seq498, Affymetrix413, Agilent709, and Agilent262) [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Figure 1 shows the schematic representation of the analyses carried out in the present study.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the procedure used in the study. Workflow of the procedures used to build and test the neuroblastoma (NB)-hop classifier. The gene expression profile of 1620 NB tumors were collected from three different gene expression datasets. Datasets were purged of incomplete and unreliable samples. COMBAT adjusted the data for batch effect removal. The resulting dataset of patients was divided into training and test sets. LibSVM was used to build the NB-hop classifier in the batch-adjusted and Agilent262 data sets. The performance of the NB-hop classifier was then assessed in the test set. Survival analysis evaluated the clinical relevance of the NB-hop classifier. Differential expression analysis (DEA) and pathway analysis explored the molecular mechanisms altered between favorable and unfavorable NB-hop tumors. Microenvironment cell populations (MCP)-counter method estimated the abundance of immune and stromal cell populations. Network analysis assessed the functional association among genes. Correlation analysis estimated the strength of relationship between the expression of two genes. An additional data set composed by 262 gene expression profiles from untreated primary NB tumors coupled with patient status was used for investigating the link between hypoxia and TMM and/or telomerase activity. FU: Follow-up. NB-hop: Neuroblastoma hypoxia outcome predictor. SVM: Support vector machine. DEA: Differential expression analysis. MCP-counter: Microenvironment cell populations-counter.

The relative percentage of patient outcome was comparable among the four data sets. Table 1 summarizes platform information, clinical, and molecular characteristics of patients.

Table 1.

Platform information and clinical and biological characteristics of NB patients within the four cohorts used in the study.

| Platform | RNA-seq498 (n = 498) | Affymetrix413 (n = 413) | Agilent709 (n = 709) | Agilent262 (n = 262) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Illumina HiSeq 2000 RNASeq | Affymetrix HG-U133 plus 2.0 | Agilent 44 K oligonucleotide array | Agilent 44 K oligonucleotide array |

| Probe set Annotation | RefSeq | Proprietary | Proprietary | Proprietary |

| Number of Probe Sets | 43,827 | 40,352 | 43,290 | 43,290 |

| Patients’ Characteristics | ||||

| Age at Diagnosis | ||||

| <18 months | 300 (60.2%) | 201 (48.6%) | 431 (60.7%) | 146 (55.8%) |

| ≥18 months | 198 (39.8%) | 160 (38.7%) | 276 (39.3%) | 116 (44.2%) |

| na | 0 (0%) | 52 (12.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| INSS Stage | ||||

| 1 | 121 (24.3%) | 88 (21.3%) | 158 (22.2%) | 30 (11.5%) |

| 2 | 78 (15.7%) | 56 (13.5%) | 116 (16.3%) | 37 (14.1%) |

| 3 | 63 (12.7%) | 63 (15.2%) | 92 (12.9%) | 33 (12.6%) |

| 4 | 183 (36.7%) | 153 (37%) | 259 (36.0%) | 130 (49.6%) |

| 4s | 53 (10.6%) | 44 (10.6%) | 80 (11.2%) | 32 (12.2%) |

| na | 0 (0%) | 9 (2.4%) | 4 (1.4%) | 0 (0%) |

| MYCN Status | ||||

| normal | 401 (80.5%) | 329 (79.6%) | 581 (80.5%) | 191 (72.9%) |

| amplified | 92 (18.5%) | 76 (18.4%) | 122 (18.5%) | 70 (26.7%) |

| na | 5 (1.0%) | 8 (2%) | 6 (1.0%) | 1 (0.4%) |

| Event Overall | ||||

| no | 393 (78.9%) | 282 (68.3%) | 548 (77.3%) | 202 (77.1%) |

| yes | 105 (21.1%) | 81 (19.6%) | 161 (22.7%) | 60 (22.9%) |

| na | 0 (0%) | 50 (12.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Event-free | ||||

| no | 315 (63.2%) | 216 (52.3%) | 439 (60.3%) | 148 (56.5%) |

| yes | 183 (36.8%) | 96 (23.2%) | 249 (36.8%) | 114 (43.5%) |

| na | 0 (0%) | 101 (24.5%) | 21 (2.9%) | 0 (0%) |

| Follow-up Duration (Years) | 5.4 (3.0–8.6) | 2.1 (0.9–4.6) | 5.6 (3.0–8.7) | na |

| Telomere Maintenance | ||||

| no | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 99 (37.7%) |

| yes | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 109 (41.6%) |

| na | 262 (100%) | 262 (100%) | 262 (100%) | 54 (20.7%) |

| ALT | ||||

| no | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 177 (67.5%) |

| yes | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 31 (11.8%) |

| na | 262 (100%) | 262 (100%) | 262 (100%) | 54 (20.7%) |

| Documented Regression | ||||

| no | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 190 (72.5%) |

| yes | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 18 (6.8%) |

| na | 262 (100%) | 262 (100%) | 262 (100%) | 54 (20.7%) |

| TERT Rearrangements | ||||

| no | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 231 (88.1%) |

| yes | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 31 (11.9%) |

| na | 262 (100%) | 262 (100%) | 262 (100%) | |

| ATRX Mutation | ||||

| - | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 75 (28.7%) |

| Deletion | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 7 (2.8%) |

| Non sense | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| na | 262 (100%) | 262 (100%) | 262 (100%) | 179 (68.4%) |

| RAS Mutations | ||||

| no | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (1.9%) |

| yes | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 43 (16.4%) |

| na | 262 (100%) | 262 (100%) | 262 (100%) | 214 (81.7%) |

| RAS Mutations | ||||

| no | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 36 (13.7%) |

| yes | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 12 (4.6%) |

| na | 262 (100%) | 262 (100%) | 262 (100%) | 214 (81.7%) |

Data are relative to the patients within the four datasets RNA-seq498, Affymetrix413, Agilent498, and Agilent262 used in the study. In each subdivision, data show the total number of patients and the relative percentage within brackets. na indicates not available. NB: neuroblastoma. INSS: International Neuroblastoma Staging System. ALT: Alternative lengthening of telomere.

Age at diagnosis, international NB staging system (INSS) stage, MYCN status, event overall, and event-free data were available for all data sets. Patient follow-up was available for RNA-seq498, Affymetrix413, and Agilent709 data sets, but not for Agilent262, whereas telomere maintenance, ALT, documented regression, TERT rearrangement, ATRX mutation, RAS, and p53 mutation data were only available for the Agilent262 data set.

2.2. Integration of Gene Expression Profiles of NB Primary Tumors Using the COMBAT Batch-Effect Removal Method

The gene expression profiles of RNA-seq498, Agilent709, and Affymetrix413 data sets were integrated into a single data set to achieve a large-scale genomic data analysis. 577 patients were filtered out from the analysis either because of missing information about outcome or of follow-up shorter than five years (Figure 1). Furthermore, 257 patients that were profiled with both Illumina and Agilent technologies were removed from the Agilent709 data set to have independent data sets. Proprietary identifiers of each platform were mapped into gene symbols for comparability. The new merged and filtered data set comprised 786 patients that included 288 patients from Agilent709, 367 from RNA-seq498 and 131 from Affymetrix413.

It is known that the batch effect may be introduced when data sets from different gene expression platforms are integrated [28]. Batch effect can be estimated using principal variance component analysis (PVCA). PVCA uses the weighted average proportion variance (WAPV) to estimate the magnitude of any source of variability using biological, clinical, and batch variables [28]. Thus, the presence of a potential batch effect in the merged data set was assessed by PVCA. The PVCA results showed a WAPV of platform of 0.79, indicating that data integration introduced a measurable batch effect (Figure S1). Several computational methods have been proposed to remove batch effect from the data [28]. COMBAT is a well-known method to remove batch effect in the data applying an empirical bayes approach [28]. The application of the COMBAT technique to the gene expression profiles of RNA-seq498, Agilent709 and Affymetrix413 data sets removed the batch effect introduced by integrating the data from three different platforms (WAPV of Platform = 0.0; Figure S2). Furthermore, analysis evidenced the variance explained by the biological and clinical variables (WAPV > 0, Figure S2). The 786 gene expression profiles of the batch-adjusted data set are available in Table S1.

The expression profiles of 236 randomly selected tumors out of 786 (30%) served to build a classifier and the profiles of the remaining 550 tumors (70%) were used to test its prognostic value in a validation data set. The clinical and molecular characteristics of patients in the training and test sets are summarized in Table S2 and listed in Table S3.

2.3. Identification of a New Multiplatform Hypoxia Biomarker

We have previously used a biology-driven approach in order to assess the hypoxic status of NB cells identifying a 11 probe set signature that was able to accurately predict NB patient outcome [19]. This signature could not be used in the present study because the probe identifiers used were specific of the Affymetrix U133 plus 2.0 gene expression platform. Hence, we refined the signature by mapping the probe sets into gene symbols to obtain a multi-platform biomarker. 9 out of the 11 probe sets were annotated with a gene symbol, whereas two were not associated with a gene symbol and were excluded from subsequent analysis. Seven out of nine gene symbols were unique. Therefore, a new seven-gene biomarker named NB-hop (NB-hypoxia outcome prediction) was defined. Table 2 lists the main characteristics of NB-hop genes.

Table 2.

NB-hop gene signature used in the prognostic model.

| NB-hop | Gene Title | Affymetrix Probe Sets | Chromosome | Band | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Expression is Associated with Poor Prognosis | ||||||

| PGK1 | phosphoglycerate kinase 1 | 200738_s_at, 17356_s_at | X | q21.1 | 6.5 (3.9–10.7) | <0.0001 |

| PDK1 | pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase, isozyme 1 | 206686_at, 226452_at | 2 | q31.1 | 1.8 (1.4–2.4) | <0.0001 |

| MTFP1 | mitochondrial fission process 1 | 223172_s_at | 22 | q12.2 | 2.4 (1.8–3.1) | <0.0001 |

| FAM162A | family with sequence similarity 162, member A | 223193_x_at | 3 | q21.1 | 1.9 (1.3–2.8) | <0.0001 |

| EGLN1 | egl nine homolog 1 (C. elegans) | 224314_s_at | 1 | q42.2 | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) | >0.05 |

| AK4 | adenylate kinase 4 | 230630_at | 1 | p31.3 | 1.1 (0.7–1.6) | >0.05 |

| High Expression is Associated with Good Prognosis | ||||||

| ALDOC | aldolase C, fructose-bisphosphate | 202022_at | 17 | q11.2 | 0.7 (0.5, 0.8) | <0.001 |

Univariate analysis was carried out by Cox regression using overall survival in the batch-adjusted training set. Significant p-values are depicted in bold. Genes with a hazard ratio greater than 1 were associated with poor prognosis. Genes with a hazard ratio smaller than 1 were associated with good prognosis. CI: confidence interval; NB: neuroblastoma.

These genes encode for proteins that are involved in metabolic response to hypoxia. Univariate analysis of overall survival in the batch-adjusted training set based on the NB-hop genes showed that high expression of PGK1, PDK1, MTFP1, and FAM162a genes was associated with a significantly higher risk of death (hazard ratio (HR) > 1 and p-value < 0.05; Table 2), while a high expression of ALDOC was associated with a lower risk of death (HR < 1 and p-value < 0.05; Table 2).

2.4. Generation and Validation of a NB-hop Classifier for Predicting NB Patient Prognosis

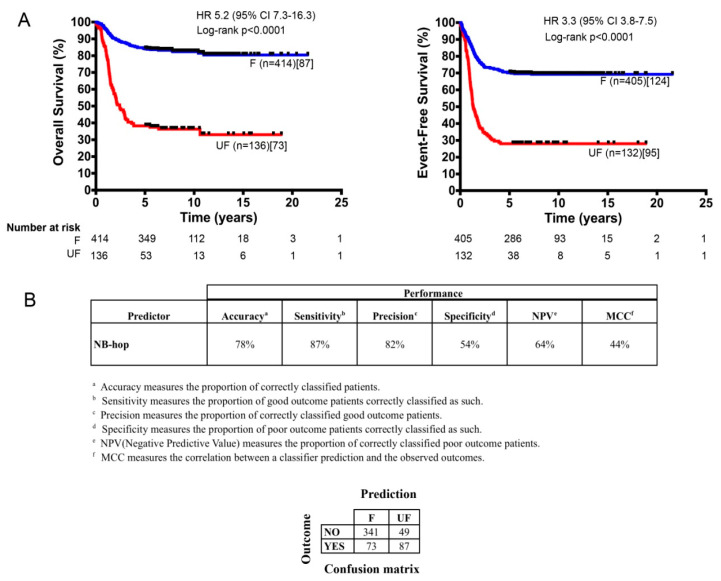

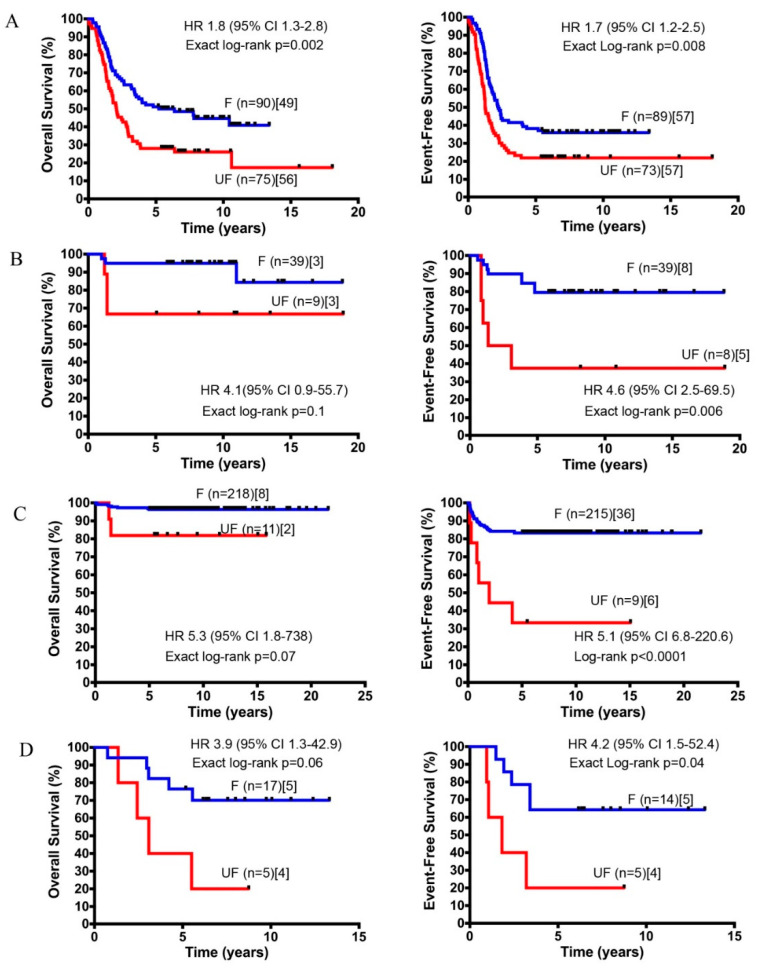

The classifier was built from the expression of NB-hop genes and patient outcome in the training set using the LibSVM library and the leave one-out cross validation (LOOCV) technique (Section 4). The predictive power of the NB-hop classifier was then estimated in the test set. NB-hop classifier predicted 414 out of 550 patients (75%) at favorable prognosis (F) and 136 out of 550 patients (25%) at unfavorable prognosis (UF). Moreover, it was able to stratify patients into subgroups that had a significantly different overall survival (OS) and event-free survival (EFS) (OS: HR 5.2 95% confidence interval (CI) 7.3–16.3 and EFS: HR 3.3 95% CI 3.8–7.5, both p < 0.0001; Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of Overall survival (OS) and Event-free survival (EFS) and prediction performances of the NB-hop classifier (A). The OS (left plot) and the EFS (right plot) of the two populations of NB patients predicted by the NB-hop classifier in the test cohort (n = 550) are shown. The classifier was built from the expression of NB-hop genes and patient outcome in the training set using the LibSVM library and leave one-out cross validation (LOOCV) technique. Blue and red curves represent the F and the UF classifications, respectively. Curves were compared by log-rank test. Log rank p value, number of patients classified by NB-hop (brackets), and number of deaths or events in each group of patients (square brackets) are reported. The number of patients at risk is displayed under the Kaplan–Meier plots. Each plot reports the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% of confidence interval (95% CI). (B) The NB-hop classifier prediction performances, measured by accuracy, sensitivity, precision, specificity, NPV, and MCC are shown. A brief description of the performance measures and the confusion matrix appear under the table. OS: Overall survival; EFS: Event-free survival; F: Favorable; UF: Unfavorable; HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; NPV: negative predictive value; MCC: Matthew’s correlation coefficient.

Our classifier obtained a significant overall performance of 44% of Matthew’s correlation coefficient (MCC) (78% of Accuracy) in the test set (Figure 2B and Table S3). For comparison, we trained and tested four alternative machine learning algorithms on the batch-adjusted data set. The performance of each of these methods was lower than that of libSVM (MCC < 44%, Table S4). To assess the significance of the NB-hop classifier performance, we applied the ConfusionMatrix function that was implemented in the Caret R Package [29] to NB-hop prediction and event overall in the batch-adjusted test set. We found that the no information rate was 0.709 and the difference of accuracy between NB-hop classifier and no information rate was significant (p value < 0.0001). These findings support our conclusion that the NB-hop classifier is an accurate predictor of NB patients’ outcome.

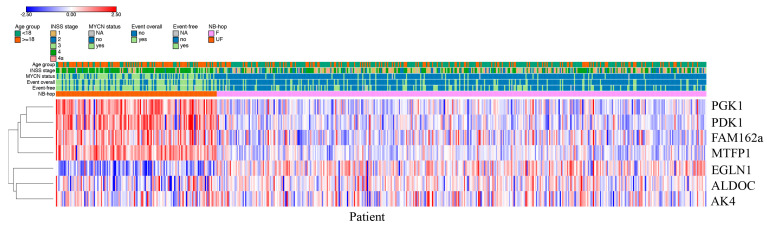

Patients predicted as UF by NB-hop had a clear different expression profile with respect to those predicted as F NB-hop, demonstrating that NB-hop was able to distinguish two groups of patients at the gene expression level (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Heat map based on NB-hop gene expression in the batch-adjusted test set. The expression values for each gene belonging to the NB-hop signature (rows) have been scaled and are represented by pseudo-colors in the heat map. Red color corresponds to high level of expression and blue color corresponds to low level of expression. Patients (columns) are divided into two groups according to NB-hop predictions. Indicated on top of the heat map are age groups, INSS stage, MYCN status, event overall, event-free and NB-hop prediction with the relative color legend. The expression value of the seven NB-hop genes was grouped by hierarchical clustering. The hierarchical clustering dendogram is shown on the left. F: Favorable. UF: Unfavorable. NB-hop: neuroblastoma hypoxia outcome predictor.

HIF-1a and HIF-2a are hypoxia inducible factor α-subunits that mediate the cellular response to hypoxia [16]. We compared the distribution of HIF-1a and EPAS1/HIF-2a mRNA expression of NB patients grouped by NB-hop prediction in batch-adjusted test set. Box plots displayed in Figure S3 show a significant up-regulation of HIF-1a and a significant down-regulation of EPAS1/HIF-2a expression in the group of UF NB-hop tumors (p < 0.0001). These data indicate that UF NB-hop tumors are more hypoxic than F NB-hop tumors. We also correlated the HIF-1a gene expression and that of each NB-hop marker by Pearson correlation. We found a significant correlation between HIF1a and NB-hop markers (p < 0.05).

The prognostic power of the NB-hop classifier was compared with that of established markers utilizing NB-hop classifier predictions (UF vs. F), INSS stage (4 vs. 1, 2, 3, 4 s), age at diagnosis (age ≥ 18 months vs. < 18 months), and MYCN status (amplified vs. single copy) in the test set. UF NB-hop, advanced stages 4, age ≥ 18 months, and MYCN amplification were significantly associated with a higher risk of death or undergoing an event according to a univariate analysis (HR > 1 and p < 0.0001; Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of overall and event-free survival in the batch-adjusted test set.

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | HR | 95% CI | p Value | HR | 95% CI | p Value |

| Overall survival | ||||||

| NB-hop (UF vs. F) | 5.4 | (3.9–7.4) | <2.0 × 10−16 | 1.8 | (1.2–2.6) | 4.20 × 10−3 |

| Age at diagnosis (≥18 months vs. <18 months) | 7.4 | (5.0–10.9) | <2.0 × 10−16 | 3.6 | (2.3–5.5) | 8.50 × 10−9 |

| INSS stage (4 vs. 1, 2, 3, 4 s) | 5.9 | (4.0–8.5) | <2.0 × 10−16 | 2 | (1.3–3.1) | 8.60 × 10−4 |

| MYCN status (Amplified vs. normal) | 6.8 | (5.0–9.4) | <2.0 × 10−16 | 2.7 | (1.8–3.9) | 3.70 × 10−7 |

| Event-free survival | ||||||

| NB-hop (UF vs. F) | 3.4 | (2.6–4.5) | <2.0 × 10−16 | 1.7 | (1.2–2.5) | 1.40 × 10−3 |

| Age at diagnosis (≥18 months vs. <18 months) | 3 | (2.2–3.9) | 7.11 × 10−15 | 1.8 | (1.3–2.5) | 2.20 × 10−4 |

| INSS stage (4 vs. 1, 2, 3, 4 s) | 2.9 | (2.2–3.8) | 2.83 × 10−14 | 1.6 | (1.1–2.2) | 4.60 × 10−3 |

| MYCN status (Amplified vs. normal) | 3.4 | (2.6–4.5) | <2.0 × 10−16 | 1.6 | (1.1–2.3) | 4.40 × 10−3 |

Univariate and multivariate analysis of overall and event-free survival assessed by Cox regression in the test set. Significant p-values are depicted in bold. HR: Hazard ratio. CI: Confidence interval. UF: unfavorable. F: favorable. INSS: international neuroblastoma staging system.

Importantly, the NB-hop classifier maintained a significant prognostic effect in the model adjusted for these clinical covariates in multivariate analysis (OS: HR 1.8 95% CI 1.2–2.6, p = 0.004 and EFS: HR 1.7 95% CI 1.2–2.5, p = 0.001; Table 3). We concluded that NB-hop is an independent prognostic biomarker of unfavorable prognosis in NB.

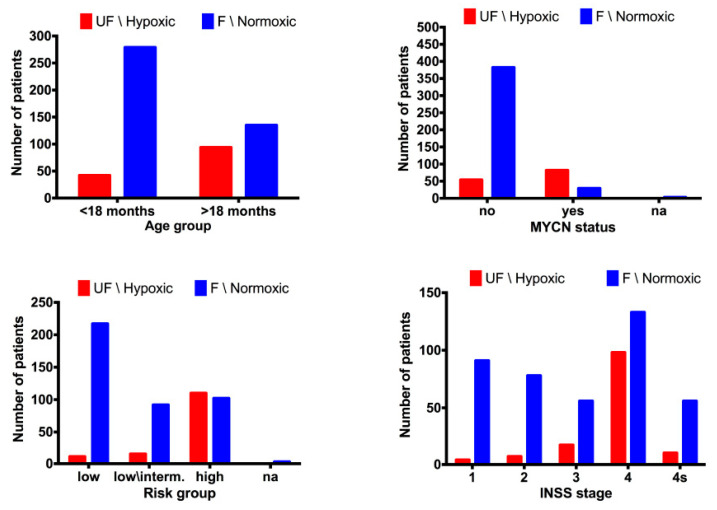

We evaluated the distribution of the two populations of patients with F and UF prognosis in the subsets defined by age at diagnosis, INSS stage, MYCN status, and risk group. The number of patients predicted with UF NB-hop was greater than zero in all subsets, but it was higher in patients with age greater than 18 months, INSS stage 4, amplified MYCN, and high-risk disease (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Bar plots of the distribution of NB-hop predictions in the batch-adjusted test set. The bar plots shows the number of patients with unfavorable prognosis (UF) NB-hop (red) and F NB-hop (blue) on the y-axis and one of the reference variables (age at diagnosis, INSS stage, MYCN status, and risk group) on the x-axis. Age at diagnosis was split into two groups, one >18 months and the other <18 months. Risk group was divided into low, low/intermediate, and high risk on the basis of International NB risk group (INRG) pre-treatment risk stratification schema. Na stands for not accessible value. NB-hop prediction labels are displayed on top of each bar plot.

These results indicate that UF patients are associated with unfavorable clinical characteristics and suggest that NB-hop may additionally stratify clinical groups of patients. We assessed the stratification of sub-cohorts defined by known prognostic markers in order to test this hypothesis (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary of Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS and EFS based on the NB-hop prediction after subdividing patients of the batch-adjusted test set into sub-cohorts.

| F NB-hop | UF NB-hop | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Survival Probability | SEM | No. of Patients | Survival Probability | SEM | No. of Patients | p |

| Stage 1 (n = 95) | 91 | 4 | |||||

| 5-year OS | 0.98 | 0.01 | 0.5 | 0.2 | <0.0001 | ||

| 5-year EFS | 0.95 | 0.02 | 0 | 0 | <0.0001 | ||

| Stage 2 (n = 85) | 78 | 7 | |||||

| 5-year OS | 0.96 | 0.02 | 0.57 | 0.18 | <0.0001 | ||

| 5-year EFS | 0.75 | 0.05 | 0.33 | 0.19 | 0.06 | ||

| Stage 3 (n = 73) | 56 | 17 | |||||

| 5-year OS | 0.87 | 0.04 | 0.29 | 0.11 | <0.0001 | ||

| 5-year EFS | 0.65 | 0.06 | 0.23 | 0.1 | 0.008 | ||

| Stage 4 (n = 231) | 133 | 98 | |||||

| 5-year OS | 0.63 | 0.04 | 0.32 | 0.04 | <0.0001 | ||

| 5-year EFS | 0.5 | 0.04 | 0.25 | 0.04 | <0.0001 | ||

| Stage 4s (n = 66) | 56 | 10 | |||||

| 5-year OS | 0.89 | 0.04 | 0.9 | 0.09 | ns | ||

| 5-year EFS | 0.72 | 0.06 | 0.77 | 0.13 | ns | ||

| Age at diagnosis <18 months (n = 321) | 279 | 42 | |||||

| 5-year OS | 0.94 | 0.01 | 0.61 | 0.07 | <0.0001 | ||

| 5-year EFS | 0.79 | 0.02 | 0.46 | 0.07 | <0.0001 | ||

| Age at diagnosis >=18 months (n = 229) | 135 | 94 | |||||

| 5-year OS | 0.62 | 0.04 | 0.27 | 0.04 | <0.0001 | ||

| 5-year EFS | 0.51 | 0.04 | 0.2 | 0.04 | <0.0001 | ||

| MYCN single copy (n = 436) | 382 | 54 | |||||

| 5-year OS | 0.88 | 0.01 | 0.5 | 0.06 | <0.0001 | ||

| 5-year EFS | 0.72 | 0.02 | 0.32 | 0.06 | <0.0001 | ||

| MYCN amplified (n = 111) | 29 | 82 | |||||

| 5-year OS | 0.31 | 0.08 | 0.3 | 0.05 | ns | ||

| 5-year EFS | 0.33 | 0.09 | 0.25 | 0.04 | ns |

SEM indicates the standard error of mean. ns stands for not significant result. Survival curves have been compared by approximate log-rank test or exact log-rank test when approximate log-rank p value < 0.0001 or >0.0001, respectively.

The NB-hop classifier significantly stratified patients with tumor stage 1, 2, 3, and 4, patients with age < 18 months, patients with age > 18 months, and patients with not amplified MYCN tumor (p < 0.05). The NB-hop classifier was not able to significantly stratify patients with amplified MYCN or stage 4s tumors (p > 0.05).

Next, the prognostic value of our predictor was assessed in additional clinically relevant subgroups of patients defined by combination of established prognostic markers. The group of high-risk patients older than 18 months with stage 4 tumors is a group traditionally difficult to stratify [1]. NB-hop classifier identified two subgroups of patients with significantly different OS and EFS (OS: HR 1.8 95% CI 1.3–2.8, p = 0.002 and EFS: HR 1.7 95% CI 1.2–2.5, p = 0.008; Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

OS and EFS of clinically relevant sub-groups of patients stratified by the NB-hop classifier. Kaplan-Meier curves show OS and EFS of NB patients in the test set predicted by NB-hop classifier. Plots are relative to (A) high-risk patients, stage 4, and age > 18 months, (B) intermediate-risk patients, stage 4, age < 18 months, and with not amplified MYCN tumors, (C) low-risk patients with stages 1, 2, 4s and no MYCN amplification tumor, (D) intermediate-risk patients, age > 18 months, stage 3 with not amplified MYCN tumors. Plots are entitled with the characteristics of the patients in the sub-population. F NB-hop (blue) and UF (red) curves were compared by approximate log-rank test or exact log-rank test when approximate log-rank p value <0.0001 or >0.0001, respectively. Each plot reports the HR and 95% CI. Number of patients classified as F or UF (brackets), and the number of patients who succumbed to disease or underwent an event (square brackets) are reported. OS: Overall survival; EFS: Event-free survival; HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; F: favorable; UF: Unfavorable.

The NB-hop classifier achieved a significant prediction performance of 21% MCC (Fisher p-value = 0.009). In the subgroup of low and intermediate-risk patients with stage 4 tumors lacking MYCN amplification and age < 18 months, NB-hop classifier identified two groups of patients with significant different EFS (EFS: HR 4.6 95% CI 2.5–69.5, p = 0.006; Figure 5B), but did not significantly discriminate patients who died from disease in this subgroup (OS: HR 4.1 95% CI 0.9–55.7, p = 0.1; Figure 5B).

In the subset of patients with stage 1, 2, 4s tumors lacking MYCN amplification, who are notoriously at low-risk of dying of disease [2], our classifier was able to discriminate patients who underwent an event from those who did not (EFS: HR 5.1 95% CI 6.8–220.6, p < 0.0001 Figure 5C). On the contrary, NB-hop was not able to significantly stratify patients who died, even though we observed a positive trend (OS: p > 0.05, Figure 5C). Patients that were older than 18 months with stage 3 and not amplified MYCN tumor constitute a group of localized tumors at intermediate risk, whose stratification remains a challenge [30]. NB-hop classifier was able to additionally stratify this population of patients (OS: HR 3.9 95% CI 1.3–42.9 and EFS: HR 4.2 95% CI 1.5–52.4, p ≤ 0.05 Figure 5D).

These findings highlight the ability of NB-hop to stratify NB patients that are difficult to stratify with actual risk assignment, indicating the potential prognostic significance of this classifier in NB.

2.5. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis of Primary Tumor Specimens between NB-hop Unfavorable and Favorable Patients

Microarray and RNA-seq platforms provide expression quantification of several transcripts in parallel from a sample. We compared the tumor transcription profile between F and UF populations of NB patients predicted by NB-hop classifier in the test set in order to investigate the key molecular mechanisms altered in NB hypoxic TME. Expression differences ≥1.5 or ≤−1.5 and Benjamini–Hochberg q-value ≤0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Using these selection criteria, we identified 2377 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (Table S5). Among them, 926 were up-regulated and 1451 were down-regulated in UF NB-hop with respect to F NB-hop tumors.

Pathway analysis is a well-known bioinformatic tool that is used to explore the biological processes and pathways associated with a list of differentially expressed genes using curated ontologies [31]. The list of DEGs was analyzed by the STRING-DB software using Gene ontology (GO), KEGG, and REACTOME ontologies (see Materials and Methods). Pathway analysis of up and down-regulated genes identified 546 and 705 significantly enriched biological processes and pathways in UF NB-hop, respectively. Table S6 reports the complete list of significant processes and pathways for every analysis. Table 5 presents a selection of significantly enriched functional terms.

Table 5.

Summary of the biological processes and pathways significantly modulated in the UF respect to F NB-hop patients of the test set.

| Biological Process a | Gene Set Id b | Pathway or Process Description c | Number of Genes d | FDR q-Value e | Type of Regulation f | Ontology g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response to hypoxia | ||||||

| GO: 0071456 | Cellular response to hypoxia | 19 | 1.00 × 10−3 | UP | GO BP | |

| GO: 0001666 | Response to hypoxia | 26 | 2.00 × 10−2 | UP | GO BP | |

| Telomere Maintenance | ||||||

| HSA-180786 | Extension of Telomeres | 17 | 1.68 × 10−10 | UP | RCTME | |

| HSA-157579 | Telomere Maintenance | 21 | 1.64 × 10−9 | UP | RCTME | |

| HSA-174417 | Telomere C-strand (Lagging Strand) Synthesis | 13 | 5.90 × 10−8 | UP | RCTME | |

| GO: 0000723 | Telomere maintenance | 22 | 1.00 × 10−6 | UP | GO BP | |

| GO: 0032201 | Telomere maintenance via semi-conservative replication | 11 | 2.77 × 10−6 | UP | GO BP | |

| Chromatin remodeling | ||||||

| GO: 0031497 | Chromatin assembly | 31 | 9.97 × 10−9 | UP | GO BP | |

| GO: 0031055 | Chromatin remodeling at centromere | 15 | 2.02 × 10−6 | UP | GO BP | |

| GO: 0006325 | Chromatin organization | 66 | 3.32 × 10−6 | UP | GO BP | |

| GO: 0006338 | Chromatin remodeling | 26 | 5.45 × 10−6 | UP | GO BP | |

| DNA damage response | ||||||

| GO: 0051276 | Chromosome organization | 143 | 3.32 × 10−27 | UP | GO BP | |

| GO: 0007059 | Chromosome segregation | 67 | 5.21 × 10−24 | UP | GO BP | |

| HSA-73886 | Chromosome Maintenance | 32 | 1.86 × 10−14 | UP | RCTME | |

| GO: 0006281 | DNA repair | 77 | 4.27 × 10−16 | UP | GO BP | |

| HSA-73894 | DNA Repair | 47 | 9.85 × 10−11 | UP | RCTME | |

| GO: 0006302 | Double-strand break repair | 29 | 1.88 × 10−6 | UP | GO BP | |

| hsa03410 | Base excision repair | 10 | 4.00 × 10−4 | UP | KEGG | |

| GO: 0006284 | Base-excision repair | 9 | 5.00 × 10−3 | UP | GO BP | |

| hsa03430 | Mismatch repair | 6 | 2.00 × 10−2 | UP | KEGG | |

| P53 mediated Cell cycle arrest and cellular senescence | ||||||

| HSA-6791312 | TP53 Regulates Transcription of Cell Cycle Genes | 14 | 6.62 × 10−6 | UP | RCTME | |

| HSA-6804756 | Regulation of TP53 Activity through Phosphorylation | 18 | 1.99 × 10−5 | UP | RCTME | |

| GO:0006977 | DNA damage response, signal transduction by p53 class mediator resulting in cell cycle arrest | 14 | 1.00 × 10−4 | UP | GO BP | |

| HSA-6804116 | TP53 Regulates Transcription of Genes Involved in G1 Cell Cycle Arrest | 7 | 2.40 × 10−4 | UP | RCTME | |

| HSA-6804114 | TP53 Regulates Transcription of Genes Involved in G2 Cell Cycle Arrest | 7 | 7.50 × 10−4 | UP | RCTME | |

| hsa04218 | Cellular senescence | 20 | 2.00 × 10−3 | UP | KEGG | |

| hsa04115 | p53 signaling pathway | 12 | 4.00 × 10−3 | UP | KEGG | |

| Cell cycle and proliferation | ||||||

| GO: 0007049 | Cell cycle | 196 | 6.38 × 10−43 | UP | GO BP | |

| GO: 0000278 | Mitotic cell cycle | 136 | 4.17 × 10−42 | UP | KEGG | |

| GO: 0051301 | Cell division | 87 | 1.15 × 10−21 | UP | GO BP | |

| GO: 0008283 | Cell population proliferation | 64 | 1.07 × 10−5 | UP | GO BP | |

| Immune response | ||||||

| GO: 0046649 | Lymphocyte activation | 63 | 1.87 × 10−7 | DOWN | GO BP | |

| GO: 0042110 | T cell activation | 45 | 1.27 × 10−6 | DOWN | GO BP | |

| GO: 0002250 | Immune response | 168 | 7.98 × 10−6 | DOWN | GO BP | |

| Cell differentiation | ||||||

| GO: 0030154 | Cell differentiation | 365 | 2.59× 10−11 | DOWN | GO BP | |

| GO: 0022008 | Neurogenesis | 193 | 6.90 × 10−11 | DOWN | GO BP | |

| GO: 0030182 | Neuron differentiation | 134 | 3.75 × 10−10 | DOWN | GO BP | |

| GO: 0002521 | Leukocyte differentiation | 51 | 2.60 × 10−5 | DOWN | GO BP | |

| GO: 0030217 | T cell differentiation | 29 | 4.39 × 10−5 | DOWN | GO BP | |

| GO: 0030098 | Lymphocyte differentiation | 39 | 1.30 × 10−4 | DOWN | GO BP | |

| Cell motility | ||||||

| GO: 0048870 | Cell motility | 108 | 7.41 × 10−5 | DOWN | GO BP | |

| HSA-1474244 | Extracellular matrix organization | 45 | 1.00 × 10−3 | DOWN | RCTME | |

| GO: 0007155 | Cell adhesion | 141 | 5.55 × 10−15 | DOWN | GO BP | |

| hsa04514 | Cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) | 40 | 3.14 × 10−9 | DOWN | KEGG | |

| Inflammation response | ||||||

| GO: 0006954 | Inflammatory response | 71 | 6.87 × 10−6 | DOWN | GO BP | |

| GO: 0071345 | Cellular response to cytokine stimulus | 111 | 9.18 × 10−5 | DOWN | GO BP | |

| GO: 0050727 | Regulation of inflammatory response | 44 | 6.70 × 10−3 | DOWN | GO BP | |

| hsa04062 | Chemokine signaling pathway | 24 | 2.00 × 10−2 | DOWN | KEGG | |

| Cell death | ||||||

| GO: 0042981 | Regulation of apoptotic process | 153 | 7.90 × 10−4 | DOWN | GO BP | |

| GO: 0043067 | Regulation of programmed cell death | 154 | 0.00086 | DOWN | GO BP | |

| Angiogenesis | ||||||

| GO: 0001568 | Blood vessel development | 61 | 0.00065 | DOWN | GO BP | |

| GO: 0001525 | Angiogenesis | 42 | 2.30 × 10−3 | DOWN | GO BP | |

| GO: 0045766 | Positive regulation of angiogenesis | 25 | 1.20 × 10−2 | DOWN | GO BP | |

a Significant GO biological processes, Reactome terms, and KEGG pathways. GO, Reactome and KEGG enrichment analysis was carried out on genes whose expression in UF NB-hop compared with F NB-hop prediction was significantly modulated. b Official identifier of a GO biological process, Reactome or KEGG pathway. c Official name of a GO biological process, Reactome term or KEGG pathway. d Number of genes of a GO biological process or Reactome term or KEGG pathway whose expression was significantly modulated in UF NB-hop tumors. e FDR q-value estimates the significance of the enrichment of a biological process or a pathway. FDR q-value <= 0.05 are considered acceptable. f Type of regulation of the genes involved in a process or a pathway. g Name of the ontology defining a biological process or pathway. GO BP stands for gene ontology biological process. KEGG stands for Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. RCTME stands for Reactome.

Up-regulated genes were mainly involved in the cellular response to hypoxia, telomere maintenance, chromatin remodeling, DNA damage response, P53 mediated cell cycle arrest, cellular senescence, cell cycle, and proliferation. Down-regulated genes were mainly involved in immune response, cell differentiation, motility, inflammation response, cell death, and angiogenesis. These results showed that patients with UF NB-hop tumor are characterized by a hypoxic, immune suppressive, poorly differentiated, and apoptosis-resistant TME.

Table 6 lists DEGs whose role has been previously reported in NB.

Table 6.

Summary of selected genes whose modulation was significant in the UF NB-hop patients.

| Biological Process a | Gene Symbol b | Gene Name c | Locus d | OMIM e | Type of Regulation f | Function g | References h |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response to hypoxia | |||||||

| GAPDH | glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 12p13.31 | 138400 | UP | GAPDH is a gene encoding a key enzyme in glycolysis and it is a hypoxia-induced gene in NB. | [32] | |

| HK2 | hexokinase 2 | 2p12 | 601125 | UP | HK2 is a gene encoding a protein that plays a key role in maintaining the integrity of the outer mitochondrial membrane. HK2 is a hypoxia-induced gene in NB and its up-regulation was associated with unfavorable prognosis in NB. | [3] | |

| LDHA | lactate dehydrogenase A | 11p15.1 | 150000 | UP | LDHA is a gene encoding an important component of the lactate dehydrogenase tetramer enzyme crucial for aerobic glycolysis. Increased expression of LDHA is associated with decreased survival and aggressive disease in NB including amplification of MYCN, older age, stage 4 and undifferentiated histology. | [33] | |

| LDHB | lactate dehydrogenase B | 12p12.1 | 150100 | UP | LDHB is a gene encoding an important component of the lactate dehydrogenase tetramer enzyme crucial for aerobic glycolysis. LDHB contributes to aggressiveness of NB. | [33] | |

| PDK1 | pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 | 2q31.1 | 602524 | UP | PDK1 is a gene encoding a mitochondrial multienzyme complex that catalyzes the oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate. PGK1 is a hypoxia-induced gene in NB and its up-regulation was associated with unfavorable prognosis in NB. | [5] | |

| PGK1 | phosphoglycerate kinase 1 | Xq21.1 | 311800 | UP | PGK1 is a gene encoding an enzyme that catalyzes one of the two ATP producing reactions in the glycolytic pathway. PGK1 is a hypoxia-induced gene in NB and its up-regulation was associated with unfavorable prognosis in NB. | [5] | |

| PKM | pyruvate kinase M1/2 | 15q23 | 179050 | UP | PKM encodes a protein involved in glycolysis and lactate production. PKM2 expression is elevated in high stage NB. | [34] | |

| SLC16A1 | solute carrier family 16 member 1 | 1p13.2 | 600682 | UP | SLC16A1 gene encodes a proton-linked monocarboxylate transporter that catalyzes the movement of several monocarboxylates including lactate and pyruvate across the plasma membrane. High SLC16A1 mRNA expression is significantly associated with worse prognosis in NB. | [35] | |

| SLCO4A1 | solute carrier organic anion transporter family member 4A1 | 20q13.33 | 612436 | UP | SLCO4A1 is a gene encoding a membrane transporter of which the only currently known solute is thyroid hormone. SLCO4A1 is a hypoxia-induced gene and its up-regulation was associated with unfavorable prognosis in NB. | [3] | |

| Telomere Mantainance | |||||||

| FEN1 | flap structure-specific endonuclease 1 | 11q12.2 | 600393 | UP | FEN1 is a DNA repair and replication endonuclease and exonuclease that has been shown to play a critical role for maintaining genomic integrity. FEN1 is a potent MYCN target gene in NB. | [36] | |

| PCNA | proliferating cell nuclear antigen | 20p12.3 | 176740 | UP | PCNA is a gene coding a protein that acts as the initial sensor of telomere damage. PCNA levels are increased in tumors with an amplified N-myc gene and in metastatic stage tumors in NB. | [37] | |

| TERT | telomerase reverse transcriptase | 5p15.33 | 187270 | UP | TERT is a gene encoding a key component of the telomerase complex. TERT plays a key role in telomere maintenance in NB. High expression levels of TERT is an unfavorable prognostic markers in NB. | [13] | |

| Chromatin remodeling | |||||||

| ARID1A | AT-rich interaction domain 1A | 1p36.11 | 603024 | DOWN | ARID1A is a chromatin-remodeling gene required for transcriptional activation of genes. ARID1A is a tumor suppressor gene in NB. ARID1A gene knockdown promotes NB migration and invasion. | [38] | |

| CHD5 | chromodomain helicase DNA binding protein 5 | 1p36.31 | 610771 | DOWN | CHD5 is a chromatin-remodeling gene that maps to 1p36.31 and is a tumor suppressor gene in NB. Low or absent CHD5 expression is associated with a 1p36 deletion and an unfavorable outcome in NB. | [39] | |

| DNA damage response | |||||||

| BRCA1 | BRCA1 DNA repair associated | 17q21.31 | 113705 | UP | BRCA1 is a gene encoding a nuclear phosphoprotein. BRCA1 protein keeps NB cells alive by cooperating with MYCN. BRCA1 expression closely correlated with MYCN amplification and was a strong indicator of poor prognosis in NB. | [40] | |

| BRCA2 | BRCA2 DNA repair associated | 13q13.1 | 600185 | UP | BRCA2 is a gene encoding a protein involved in double-strand break repair and/or homologous recombination. BRCA2 is one of the genes for which somatic mutations have been identified in primary NB. | [41] | |

| CHEK1 | checkpoint kinase 1 | 11q24.2 | 603078 | UP | CHK1 is a protein-coding gene belonging to serine/threonine-protein kinase. CHK1 performs a central role in DNA damage response and in preserving genomic integrity. CHK1 overexpression is thought to contribute to NB aggressiveness and poor NB patient survival. | [42] | |

| CHEK2 | checkpoint kinase 2 | 22q12.1 | 604373 | UP | CHK2 is a protein-coding gene belonging to serine/threonine-protein kinase. CHK2 plays a role in DNA damage response and maintenance of chromosomal stability. CHK2 overexpression is thought to contribute to NB aggressiveness. | [43] | |

| TPX2 | TPX2 microtubule nucleation factor | 20q11.21 | 605917 | UP | TPX2 is a protein-coding gene involved in spindle apparatus assembly. TPX2 plays a principal function in the DNA damage response pathway. High TPX2 expression is significantly associated with poor prognosis in NB patients. | [44] | |

| P53 mediated Cell cycle arrest and cellular senescence | |||||||

| CDK1 | cyclin dependent kinase 1 | 10q21.2 | 116940 | UP | CDK1 is a gene encoding a protein involved in the control of the eukaryotic cell cycle. CDK1 plays an essential role in NB tumor cell survival. CDK1 overexpression is associated with low survival for NB patients independently from MYCN status. | [45] | |

| CDK2 | cyclin dependent kinase 2 | 12q13.2 | 116953 | UP | CDK2 is gene encoding a member of a family of serine/threonine protein kinases that participate in cell cycle regulation. High CDK2 expression is strongly correlated with a bad prognosis. | [46] | |

| TP53 | tumor protein p53 | 17p13.1 | 191170 | UP | TP53 is a gene encoding a transcription factor that plays a critical role in the cellular defense against malignant transformation by promoting cell-cycle arrest, DNA damage repair, apoptosis, and senescence in response to stress signals. TP53 is a hypoxia-inducible gene. | [47,48] | |

| Cell cycle and proliferation | |||||||

| AURKA | aurora kinase A | 20q13.2 | 603072 | UP | AURKA is a gene encoding a member of a family of mitotic serine/threonine kinases. AURKA is a critical regulator of hypoxia-mediated tumor progression in NB. Overexpression of AURKA has been associated with poor prognosis in NB. | [49,50] | |

| ERBB4 | erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 4 | 2q34 | 600543 | UP | ERBB4 gene encodes a member of the Tyr protein kinase family and the epidermal growth factor receptor subfamily. HER4 functions as a cell cycle suppressor, maintaining resistance to cellular stress in NB. High HER4 expression significantly correlates with reduced survival in NB. | [51] | |

| LIN28B | lin-28 homolog B | 6q16.3–q21 | 611044 | UP | LIN28B is an RNA binding protein that blocks the maturation of let-7. LIN28B is an oncogene in NB. High LIN28B expression induces an increased cell proliferation. High LIN28B expression is associated with poor NB patient survival. | [52] | |

| LMO3 | LIM domain only 3 | 12p12.3 | 180386 | UP | LMO3 encodes a protein that belongs to the rhombotin family of cysteine-rich LIM domain oncogenes. LMO3 acts as an oncogene in NB. LMO3 induces marked tumor growth in nude mice. Increased expression of LMO3 is significantly associated with a poor prognosis in NB. | [53] | |

| MYCN | MYCN proto-oncogene, bHLH transcription factor | 2p24.3 | 164840 | UP | MYCN is one of the most important oncogenes in NB. MYCN plays multiple roles in malignancy and maintenance of stem-like state. Amplification of MYCN correlates with high-risk disease and poor prognosis in NB. | [54] | |

| ODC1 | ornithine decarboxylase 1 | 2p25.1 | 165640 | UP | ODC1 is a bona fide oncogene that encodes the rate-limiting enzyme in polyamine synthesis. Up-regulation of ODC1 induces a rapid tumor cell proliferation in NB. Elevated ODC1 is associated with reduced survival of NB patients. | [55] | |

| RAN | RAN, member RAS oncogene family | 12q24.33 | 601179 | UP | RAN encodes a small GTP binding protein belonging to the RAS superfamily. RAN promotes cell proliferation in neuroblastoma. High RAN expression is associated with a lower NB patient survival. | [56] | |

| Immune response | |||||||

| CADM1 | cell adhesion molecule 1 | 11q23.3 | 605686 | DOWN | CADM1 encodes a protein that mediates homophilic cell-cell adhesion in a Ca(2+)-independent manner. CADM1 down-regulation is associated with unfavorable prognosis in NB. Inhibition of CADM1 in tumor cells enables immune evasion and promotes metastasis. | [57,58] | |

| CCL19 | C-C motif chemokine ligand 19 | 9p13.3 | 602227 | DOWN | CCL12 is a cytokine involved in immunoregulatory and inflammatory processes. NB induces profound functional impairments in CCR7/CCL19-mediated dendritic cell migration in vitro and in vivo. | [59] | |

| CCL2 | C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 | 17q12 | 158105 | DOWN | CCL2 is an immunoregulatory chemokine. MYCN represses expression of CCL2 inhibiting natural killer T cell chemoattraction in NB. | [60] | |

| CCR7 | C-C motif chemokine receptor 7 | 17q21.2 | 600242 | DOWN | CCR7 encodes a member of the G protein-coupled receptor family. Murine NB inhibits mature dendritic cell function decreasing antitumor immunity via down-regulating CCR7 expression. CXCR7 expression was low in undifferentiated NB tumors. | [61,62,63] | |

| CD226 | CD226 molecule | 18q22.2 | 605397 | DOWN | CD226 encodes a glycoprotein expressed by virtually all human NK cells, T cells, and monocytes. | [64,65] | |

| CXCL12 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 | 10q11.21 | 600835 | DOWN | CXCL12 encodes a stromal cell-derived alpha chemokine member of the intercrine familyCXCL12 down-regulation in bone marrow samples from NB patients was strongly associated with worse EFS and OS. | [66] | |

| PVR | PVR cell adhesion molecule | 19q13.31 | 173850 | UP | PVR encodes a transmembrane glycoprotein that is widely expressed on normal neuronal, epithelial, endothelial, and fibroblastic cells and at high density on tumors of different histotype. | [64,65] | |

| Cell differentiation | |||||||

| ALK | ALK receptor tyrosine kinase | 2p23.2–p23.1 | 105590 | UP | ALK is a receptor tyrosine kinase involved in neuronal differentiation in NB. High ALK expression correlates with an adverse NB phenotype. ALK is an oncogene in NB. | [67] | |

| CAMTA1 | calmodulin binding transcription activator 1 | 1p36.31–p36.23 | 611501 | DOWN | CAMTA1 encodes a transcriptional activator protein. Low CAMTA1 expression inhibits neuroblastoma cell differentiation. Low CAMTA1 expression is significantly associated with markers of unfavorable tumor biology and poor outcome in NB. | [68] | |

| DNER | delta/notch like EGF repeat containing | 2q36.3 | 607299 | DOWN | DNER is a protein involved in the activation of the NOTCH1 pathway. DNER is a marker of neural differentiation. Low DNER expression is associated with a low differentiation in NB. | [69] | |

| NTRK1 | neurotrophic receptor tyrosine kinase 1 | 1q23.1 | 191315 | DOWN | NTRK1 encodes a member of the neurotrophic tyrosine kinase receptor family. Low NTRK1 expression is associated with a poorly neuronal differentiated state and a significant worse outcome in NB. | [70,71] | |

| PROM1 | prominin 1 | 4p15.32 | 604365 | UP | PROM1 encodes a pentaspan transmembrane glycoprotein. PROM1 represses NB cell differentiation and is decreased by several differentiation stimulators. High PROM1 expression was significantly associated with a decreased probability of patient survival in NB. | [72,73] | |

| PTN | pleiotrophin | 7q33 | 162095 | DOWN | PTN encodes a secreted heparin-binding growth factor. PTN is a marker of neural differentiation. Low PTN expression is associated with a lower patient survival in NB. | [69,74] | |

| RET | ret proto-oncogene | 10q11.21 | 164761 | UP | RET is an oncogenic receptor tyrosine kinase involved in NB cell proliferation and differentiation. High expression of RET correlates with poor outcomes in patients with NB. | [71,75] | |

| Cell motility and invasiveness | |||||||

| CD44 | CD44 molecule (Indian blood group) | 11p13 | 107269 | DOWN | CD44 encodes a cell-surface glycoprotein involved in cell-cell interactions, cell adhesion and migration Lack of CD44 expression has been associated with MYCN amplification and predicts risk of disease progression and dissemination in NB. | [76] | |

| CD9 | CD9 molecule | 12p13.31 | 143030 | DOWN | CD9 encodes a member of tetraspanin family. Low CD9 expression enhances inhibited migration and invasion in NB cells. Low CD9 expression in primary neuroblastomas correlates with a low probability of patient survival in NB. | [77] | |

| CDH1 | cadherin 1 | 16q22.1 | 192090 | DOWN | The CDH1 gene encodes the epithelial cell adhesion molecule, which forms the core of the adherence junctions between adjacent epithelial cells. Low expression levels of CDH1 promote NB cell migration and invasion and poor patient survival. | [78] | |

| ERBB3 | erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 3 | 12q13.2 | 190151 | DOWN | ERBB3 encodes a member of the epidermal growth factor receptor family of receptor tyrosine kinases. The decreased expression of ERBB3 was highly correlated with invasiveness in NB cell lines. The NB patients with low expression of ERBB3 showed significantly worse overall survival. | [79] | |

| L1CAM | L1 cell adhesion molecule | Xq28 | 308840 | DOWN | L1CAM is a gene encoding a protein of the immunoglobulin superfamily of cell adhesion molecules. L1CAM plays a key role in the development of the nervous system. Low L1CAM expression is associated with a worse survival in NB patients. | [80,81] | |

| NRP1 | neuropilin 1 | 10p11.22 | 602069 | DOWN | NRP1 encodes a transmembrane glycoprotein. NB cells in which NRP1 was knocked down exhibited increased migratory and invasive abilities. Lower levels of NRP1 expression were significantly associated with a shorter survival period of patients with NB. | [82] | |

| PLK4 | polo like kinase 4 | 4q28.1 | 605031 | UP | PLK4 is one of the polo-like kinase family members. Up-regulation of PLK4 in NB cells induces EMT through the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. High expression of PLK4 was negatively correlated with clinical features and survival. | [83] | |

| SRCIN1 | SRC kinase signaling inhibitor 1 | 17q12 | 610786 | DOWN | SRCIN1 is protein-coding gene that acts as a negative regulator of SRC. Low SRCIN1 expression correlates with increased metastatic recurrences in NB patients. Low SRCIN1 expression is associated with a poor prognosis in NB. | [84] | |

| Cell death | |||||||

| BIRC5 | baculoviral IAP repeat containing 5 | 17q25.3 | 603352 | UP | BIRC5 is a member of the inhibitor of apoptosis gene family. The over-expression of BIRC5 correlates with an unfavorable prognosis in NB. | [85] | |

| MYC | MYC proto-oncogene, bHLH transcription factor | 8q24.21 | 190080 | DOWN | MYC encodes a nuclear phosphoprotein that plays a role in cell cycle progression, apoptosis and cellular transformation. MYC is a proto-oncogene in NB. MYC and MYCN expression is inversely correlated in primary NB. | [86] | |

| TWIST1 | twist family bHLH transcription factor 1 | 7p21.1 | 601622 | UP | TWIST1 encodes a basic helix–loop–helix–ZIP transcription factor with crucial functions during embryogenesis. TWIST1 plays a crucial role in inhibition of apoptosis and differentiation in NB. | [87] | |

| Angiogenesis | |||||||

| EPAS1 | endothelial PAS domain protein 1 | 2p21 | 603349 | DOWN | EPAS1 encodes a transcription factor, which plays a key role during chronic hypoxia. Low level of EPAS1 expression is associated with higher NB patient survival. | [88] | |

a Main biological function associated with listed genes. b Official gene identifier sorted in alphabetic order within each functional group. c Official gene name. d Position of the gene in the chromosome. e OMIM identifier of the gene. f Type of gene regulation in the population of patients with UF NB-hop patients. Type of regulation was determined by differential expression analysis. g Short description of the gene function as reported in the literature on NB. h Main references reporting gene function in NB.

The up- or down-regulation of these genes have been previously associated with an unfavorable prognosis of NB patients, in accordance with our results. Among the up-regulated genes, several were involved in glycolysis (GAPDH, HK2, PGK1, PKM, LDHA, LDHB, and SLCO4A1), pH regulation (SLC16A1), and homeostasis (PDK1), indicating a metabolic reprogramming typical of hypoxic cells. In addition, a prominent set of up-regulated genes coding for proteins with a primary role in telomere maintenance (FEN1, PCNA, and TERT), DNA damage response (BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK1, CHEK2, and TPX2), P53 mediated cell cycle arrest (CDK1, CDK2, and TP53), and proliferation (AURKA, ERBB4, LIN28B, LMO3, MYCN, ODC1, and RAN). On the contrary, we demonstrated the down-regulation of genes coding for proteins that are involved in immune responses (CADM1, CCL19, CCL2, CCR7, CD226, and CXCL12), cell differentiation (CAMTA1, DNER, NTRK1, and PTN), cell motility and invasion (CD44, CD9, CDH1, ERBB3, L1CAM, NRP1, and SRCIN1), and angiogenesis (EPAS1). We also found the down-regulation of genes coding for proteins that are involved in chromatin remodeling (ARID1A and CHD5) and of the MYC gene and the up-regulation of genes involved in cell differentiation (ALK, PROM1, and RET), and coding for proteins that are involved in apoptosis and cell death (BIRC5 and TWIST1).

We performed a network analysis using STRING-DB software in order to assess the biological connection between HIF-1a and genes reported in Table 6 [89]. The resulting network that is shown in Figure S4 displayed significantly more interactions than expected for a random set of proteins of similar size drawn from the genome (PPI enrichment p-value < 1.0 × 10−16). Our findings establish a connection between HIF-1a and genes reported in Table 6 and indicate that those protein-coding genes are biologically connected as a group.

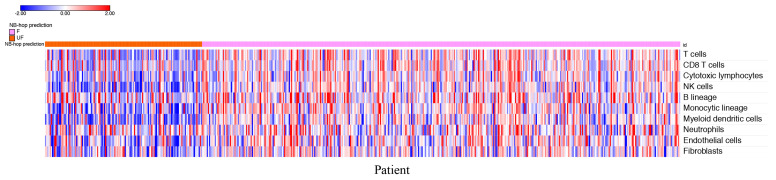

2.6. Correlating Immune Markers with NB-Hop Prediction and HIF1 Signature

The estimation of the abundance of immune and stromal cell populations in the TME may uncover their role in tumor development/progression [90]. Differential expression analysis provides useful information regarding deregulated genes, but it is not suitable for estimating the abundance of different tumor-infiltrating cells. For this purpose, we applied the microenvironment cell populations (MCP)-counter method using the expression profile of NB tumors in the batch-adjusted test set. MCP-counter is a very well-known and widely used bioinformatic tool. Furthermore, transcriptome-based cell-type quantification methods for immuno-oncology are valuable tools with several successful applications [91]. MCP-counter returned an abundance score for each cell type and tumor sample in the test set. Figure 6 depicts the heat map of the scores for each patient grouped by NB-hop prediction.

Figure 6.

Heat map of the cell abundance scores in the batch-adjusted test set. The MCP-counter score values for each cell type (rows) have been scaled and are represented by pseudo-colors in the heat map. Red color corresponds to high level of the score and blue color corresponds to low level of the score. NB patients belonging to the batch-adjusted test set (columns) are divided into two groups according to NB-hop predictions. The color key is displayed on the top left part of the plot. MCP: Microenvironment cell populations; F: Favorable; UF: Unfavorable; NB-hop: Neuroblastoma hypoxia outcome predictor.

The heat map shows a clear tendency to a lower abundance of T cells, CD8+ T cells, NK cells, cytotoxic lymphocytes, B cell lineage, monocytic lineage cells, myeloid dendritic cells, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts in patients with UF NB-hop tumors than in F NB-hop tumors, suggesting the association between an immunosuppressive TME and UF NB-hop tumors.

We carried out additional analyses to provide more links between MCP-counter analysis and hypoxia. For each cell type MCP-counter defines a set of characteristic genes that we refer to as MCP-counter markers [90]. Overlap between MCP-counter markers and genes in the HIF-1a interaction network may provide relevant evidence of a direct involvement of HIF-1a in the regulation of immune or non-immune cell population activity. To this end, we assessed the overlap between the list of MCP-counter markers and the list of genes in the HIF-1a interaction network. BioGRID is a public curated gene interaction repository [92]. Three-hundred and eighty-nine HIF-1a interactor genes were retrieved from the BioGRID repository. The resulting HIF-1a interaction network is shown in Figure S5. Venn diagram showed that none of the MCP-counter markers were in the HIF-1a interaction network. Network analysis is a valuable tool for assessing the functional interaction among a set of genes. We performed a network analysis for HIF-1a and MCP-counter markers using the STRING-DB software [89]. Interestingly, we found that HIF-1a was functionally associated with MCP-counter markers (Figure S6). These results showed a significant functional association among HIF-1a and MCP-counter markers, raising the question of the possible correlation between HIF-1a and MCP-counter markers in NB. Thus, we carried out a correlation between the expression of HIF-1a and that of each MCP-counter marker in the batch-adjusted test set using Pearson’s correlation method. The results reported in Table S7 showed that high HIF-1a expression is negatively correlated with most of the markers of T cells, CD8 T cells, cytotoxic lymphocytes, NK cells, myeloid dendritic cells cell types (Pearson r < 0 and p value < 0.05, Table S7), and positively correlated with most of the makers of monocytic lineage, neutrophils, endothelial cells and fibroblasts (Pearson r > 0 and p value < 0.05, Table S7). Within the set of significantly correlated immune markers in Table S7, we found that MAL, BANK1, CXCR2, and KCNJ15 genes have been previously reported to play a tumor suppressive role in different types of cancer [93,94,95,96]. These findings support the results shown in Figure 6.

The presence of specific immune regulatory cell populations is associated with poor outcome in different types of cancer, including NB [97]. Tumor infiltrating macrophages (TAMs) often display an immunosuppressive M2-phenotype in aggressive NB tumors [97]. Gene expression analysis of primary human NB tumors without MYCN amplification has revealed that high-level expression of TAM-specific genes, including CD14, CD16, IL6, IL6R, and TGFB1, was associated with poor five-year event-free survival [98]. We assessed the correlation between the expression of HIF-1a and that of TAM-specific genes in the batch-adjusted test set with not amplified MYCN tumors in order to find additional associations between hypoxia and immune suppressive TME in NB. The results reported in Table S8 showed a significant positive correlation between HIF-1a and CD14, IL6, and IL6R, while no significant correlation was found between HIF-1a and TGFB1. CD16/FCGR3A was absent in the batch-adjusted data set and it was excluded from the analysis. These findings suggest that hypoxia is associated with the presence of TAMs in NB without MYCN amplification supporting our conclusion that hypoxia is an unfavorable prognostic marker and is associated with an immune suppressive TME in NB.

One of the main mechanisms exploited by tumors for immune system escape is modulating immune checkpoints, inhibitory pathways that physiologically maintain self-tolerance, and limit the duration and amplitude of immune responses [99]. We focused on the immune checkpoint ligands PD-L1 (CD274), PD-L2 (PDCD1LG2), and B7-H3 (CD276), which are recognized by inhibitory receptors that are expressed by T and NK cytolytic immune effectors [99]. Because no PD-L2 gene expression was detected in the batch-adjusted data set, a comparison between UF and F NB-hop tumors was carried out for B7-H3 and PD-L1 expression. The results presented in Figure S7 showed that B7-H3 was significantly up-regulated, whereas PD-L1 was significantly down-regulated in UF NB-hop tumors, thus indicating a differential mRNA expression modulation of these immune checkpoints in NB tumors.

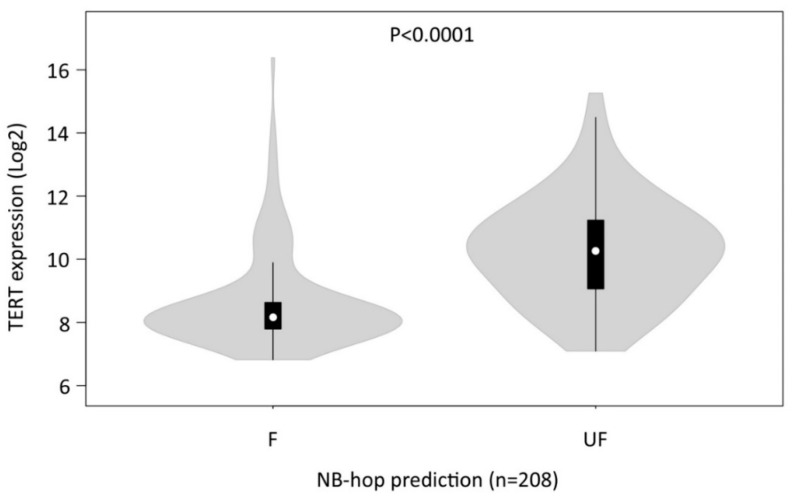

2.7. Validation of the NB-hop Classifier for Predicting TERT Gene Over-expression in an Independent Cohort of NB Patients

We used the gene expression profiles of 262 untreated primary NB tumors (Agilent262), for the majority of which we had information on the TMM activation in addition to other patient clinical and molecular data, such as age at diagnosis, ALT activation, event overall, event-free, TERT rearrangement, INSS stage, MYCN status, p53/RAS gene mutations, and spontaneous regression, in order to evaluate the association between hypoxia and TMM in NB [13]. Patients included in the data set did not overlap with the 786 patients in the batch-adjusted data set. Similarly to that described for the batch-adjusted data set, a classifier based on the expression of the 7 NB-hop genes and patient outcome was built in the training set (54 patients equal to 21%) using the LibSVM library and LOOCV technique. The predictive power of the NB-hop classifier was validated in the test set (208 patients equal to 79%). NB-hop classifier predicted a favorable prognosis for 138 out of 208 patients (66%) and an unfavorable prognosis for 70 out of 208 patients (33%). The clinical and molecular characteristics and NB-hop predictions of patients are reported in Table S9.

We, then, analyzed the distribution of TERT mRNA expression in the profiles of patients belonging to the Agilent262 test set that was grouped by NB-hop predictions. We found that TERT mRNA expression was significantly elevated in patients with UF prognosis with respect to those predicted with F prognosis (p < 0.00001, Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Distribution of telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) mRNA expression in NB patients grouped by NB-hop prediction in the Agilent262 test set. Violin plot show the distribution of TERT expression in mRNA profiles of NB patients grouped by NB-hop prediction. Data are relative to Agilent262 test set (n = 208). Significance of the expression differences between F and UF NB-hop groups of patients was assessed by unpaired t test. p-value is reported on the top. F: Favorable; UF: Unfavorable; NB: Neuroblastoma.

These findings confirmed the association between hypoxia and telomerase activity/expression, raising the question of the importance of hypoxia for TMM in NB.

2.8. Univariate Regression Analysis for Assessing the Association between Hypoxia and Telomere Maintenance Mechanisms in NB

We investigated the association between hypoxia, TMM, and other available clinical and molecular prognostic factors for NB [13] in the Agilent262 test set by univariate logistic regression analysis. This analysis showed that patients with UF expression of the NB-hop biomarker had higher odds of having an age > 18 months, of undergoing an event or relapse/progression, INSS 4 stage tumor, MYCN amplification, p53/RAS gene mutations, or TMM (odd ratio > 1 and p-value < 0.05, Table 7). The association between NB-hop and TMM is still significant even excluding amplified MYCN tumors from the data set (Odd ratio > 1 p < 0.05).

Table 7.

Univariate logistic regression analysis of known covariates on the Agilent262 test set.

| Covariate | OR | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (≥18 months vs. <18 months) | 3.1 | (1.6–5.7) | 3.03 × 10−4 |

| ALT (Yes vs. No) | 0.6 | (0.2–1.5) | 3.00 × 10−1 |

| Event Overall (Yes vs. No) | 8.4 | (3.9–18.4) | 7.77 × 10−8 |

| Event-free (Yes vs. No) | 4.3 | (2.3–7.8) | 2.12 × 10−6 |

| TERT Rearrangement (Yes vs. No) | 1.8 | (0.7–4.4) | 1.00 × 10−1 |

| INSS stage (4 vs. 1, 2, 3, 4 s) | 3.8 | (2.1–6.9) | 1.11 × 10−5 |

| MYCN status (Amplified vs. Normal) | 31.9 | (13.2–73.9) | 1.21 × 10−14 |

| P53/RAS gene mutations (Yes vs. No) | 3.7 | (1.9–7.3) | 8.18 × 10−5 |

| Spontaneous regression (Yes vs. No) | 0.1 | (0.02–0.7) | 2.00 × 10−2 |

| Telomere.Maintenance (Yes vs. No) | 16.70 | (7.3–38.2) | 2.80 × 10−11 |

Analysis was assessed by Logistic regression analysis using BayesGLM method. Covariates are sorted in alphabetic order. NB-hop prediction was used as reference class for the analysis. Significant p-values are depicted in bold. Odd ratio indicates the constant effect of hypoxia on the likelihood that one outcome will occur. OR: Odd ratio. CI: Confidence interval. UF: unfavorable. F: favorable. INSS: international neuroblastoma staging system; ALT: Alternative lengthening of telomeres.

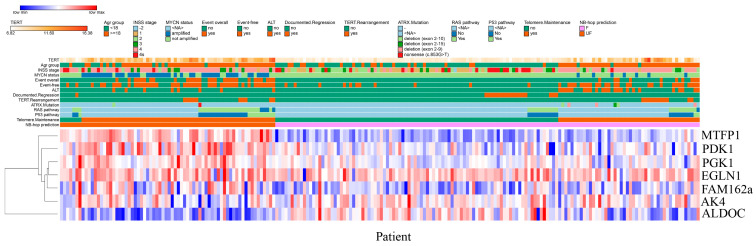

On the contrary, patients with documented tumor regression were associated with a lower odd of UF NB-hop prognosis (odd ratio < 1 and p-value < 0.05, Table 7). No significant odd ratio was found between NB-hop prediction and ALT or TERT rearrangements, which indicated that NB-hop prediction is not related to these factors (p-value > 0.05, Table 7). Heat map visualization of NB-hop gene expression and established prognostic factors for NB showed that UF NB-hop patients had a clear different expression profile with respect to F NB-hop ones, confirming that NB-hop was able to distinguish two distinct groups of patients with different prognosis at the gene expression level (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Heat map visualization of NB-hop gene expression in the Agilent262 test set. The expression values for each gene belonging to the NB-hop signature (rows) have been scaled and are represented by pseudo-colors in the heat map. Red color corresponds to high level of expression and blue color corresponds to low level of expression. NB patients (columns) belonging to the Agilent262 test set are divided into two groups according to NB-hop predictions. Age groups, INSS stage, MYCN status, event overall, event-free, TMM, ALT, p53/RAS gene mutations and NB-hop prediction are indicated on the top of the heat map with the relative color legend. The expression value of the 7 NB-hop genes was grouped by hierarchical clustering. The hierarchical clustering dendogram is shown on the left. NB-hop: neuroblastoma hypoxia outcome predictor; TMM: Telomere maintenance mechanisms; ALT: Alternative lengthening of telomeres; F: Favorable; UF: Unfavorable.

Furthermore, heat map graphically showed the association between the UF NB-hop subgroup and the worse clinical and molecular characteristic of NB patients, in accordance with the univariate regression analysis. These findings provide an indication that hypoxia is associated with telomerase activity, thus representing a potential critical factor for the classification and treatment of NB patients.

3. Discussion

Novel prognostic markers and therapeutic targets are urgently needed in the clinical settings to improve prognosis of NB patient and design more effective treatments and better-tailored therapies addressing NB heterogeneity [1]. Here, we propose a new seven-gene hypoxia biomarker, referred to as NB-hop, as an unfavorable prognostic marker for NB patients.

The NB-hop biomarker was defined by gene expression analysis carried out on 1620 tumor specimens belonging to three available data sets, whose expression was measured by three different gene expression platforms, which included Agilent, Illumina, and Affymetrix technologies. The RNA-seq498, Agilent709, and Affymetrix413 data sets were homogeneous on the basis of patient clinical and molecular data and they were used for dissecting the prognostic value of the new NB-hop hypoxia biomarker. Analysis of the gene expression profile of NB primary tumors to find prognostic factors is an active research field, and several prognostic signatures have been reported [5,6,100]. However, a large-scale expression study of NB tumors has not been previously carried out because different technologies used different proprietary annotations to identify transcripts. Meta-analysis is traditionally used in retrospective studies to overcome this problem [28]. However, meta-analysis must be replicated independently in each data set, limiting the statistical power of the study [28]. Here, we used a novel approach that is based on the application of the batch effect removal methods [28] for integrating the RNA-seq498, Agilent709, and Affymetrix413 data sets [28]. Data integration raises the question of the presence of the so-called batch effect [28]. Our analysis evidenced that the simple integration of the NB datasets introduces a measurable batch effect, which could hinder subsequent analysis. Several batch effect removal methods have been described in the literature [28]. In the present study, we used COMBAT, a well-known technique to remove batch effect for data integration [28]. The application of this method to integrate gene expression data of NB tumor samples profiled by different platforms allowed us to build up one single multiplatform and multicenter cohort of 786 patients, with at least five years of follow-up, representing the largest data set described so far in a gene expression study of NB patients.

The expression profiles of 30% NB tumor samples served to build a classifier and the profiles of the remaining 70% were used to test its prognostic value in a validation data set. Split a data set into a training set and a test set is a standard machine learning procedure for computing an unbiased estimation of the performances of a classifier. In the test set, the NB-hop classifier distinguished two groups of patients at the gene expression level. The UF NB-hop group was composed by 25% of samples and was referred as the group with hypoxic tumor and unfavorable prognosis. F NB-hop was composed by 75% of samples and referred as the group with normoxic tumor and favorable prognosis. OS and EFS were significantly lower for UF NB-hop respect to F NB-hop patients. UF NB-hop tumors were associated with unfavorable clinical characteristics including age > 18 months, INSS stage 4, amplified MYCN, or high-risk disease, which confirmed the unfavorable prognosis of UF NB-hop patients. We demonstrated that NB-hop retains its independent prognostic effect in multivariable analysis that included age at diagnosis, INSS stage, and MYCN status, which are considered the strongest prognostic clinical and molecular variables for prediction of OS and EFS in NB [2]. Analysis was focused on established risk factors in NB, such as age at diagnosis, MYCN status, and INSS stage, whose data were available in the original data sets, but not on other known risk factors, such as chromosomal aberration, ploidy, grade of differentiation, or histological category [2], because these data were not reported in the original publications.

The clinical value of novel prognostic factors is often evaluated in selected groups of patients defined by combination of established NB risk factors [5,6,100]. In this study, we assessed the prognostic value of our biomarker in clinically relevant groups of NB patients whose stratification was not previously reported. The groups included patients with metastatic (INSS stage 4) disease and age > 18 months, patients with age < 18 months, metastatic disease (INSS stage 4) and not amplified MYCN, and patients with localized (INSS stage 1, 2) or metastatic (INSS stage 4s) tumors with not amplified MYCN, and patients with age > 18 months, stage 3 and not amplified MYCN that are classified as high, intermediate, and low risk according to INRG schema [1,2,30]. We demonstrated that NB-hop additionally stratified these groups of patients, making of NB-hop a new potentially eligible biomarkers for inclusion in upcoming NB pre-treatment risk schema.