Abstract

Plants harbor various beneficial bacteria that modulate their innate immunity, resulting in induced systemic resistance (ISR) against various pathogens. However, the immune mechanisms underlying ISR triggered by Bacillus spp. and Pseudomonas spp. against pathogens with different lifestyles are not yet clearly elucidated. Here, we show that root drenching of Arabidopsis plants with Pseudomonas fluorescens PTA-CT2 and Bacillus subtilis PTA-271 can induce ISR against the necrotrophic fungus B. cinerea and the hemibiotrophic bacterium Pseudomonas syringae Pst DC3000. In the absence of pathogen infection, both beneficial bacteria do not induce any consistent change in systemic immune responses. However, ISR relies on priming faster and robust expression of marker genes for the salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and ethylene (ET) signaling pathways upon pathogen challenge. These responses are also associated with increased levels of SA, JA, and abscisic acid (ABA) in the leaves of bacterized plants after infection. The functional study also points at priming of the JA/ET and NPR1-dependent defenses as prioritized immune pathways in ISR induced by both beneficial bacteria against B. cinerea. However, B. subtilis-triggered ISR against Pst DC3000 is dependent on SA, JA/ET, and NPR1 pathways, whereas P. fluorescens-induced ISR requires JA/ET and NPR1 signaling pathways. The use of ABA-insensitive mutants also pointed out the crucial role of ABA signaling, but not ABA concentration, along with JA/ET signaling in primed systemic immunity by beneficial bacteria against Pst DC3000, but not against B. cinerea. These results clearly indicate that ISR is linked to priming plants for enhanced common and distinct immune pathways depending on the beneficial strain and the pathogen lifestyle.

Keywords: Arabidopsis, Bacillus subtilis, induced immunity, pathogens, priming, Pseudomonasfluorescens, induced resistance

1. Introduction

In hostile habitats, plants are subjects to various pathogens, including necrotrophs, biotrophs, and hemibiotrophs [1]. To restrict the pathogen infection, plants rapidly activate different layers of defenses depending on its own ability to recognize conserved microbial molecules that are characteristic of microorganisms [2,3]. The recognition of these microbial molecules known as “microbe-associated molecular patterns” (MAMPs) is mediated by a set of receptors referred to as pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs). Once pathogen or non-pathogen microbes are perceived by the plant, immune responses are often triggered in distal plant parts to protect undamaged tissues against subsequent pathogen infection. This long-lasting induced immunity is referred to as systemic acquired resistance (SAR) or induced systemic resistance (ISR) [4,5]. Accumulating evidence has shown that treatment of plant roots with beneficial bacteria enhance plant health through ISR [5], that mostly linked to a stronger and faster systemic immune response after pathogen infection, a phenomenon known as priming that allows plants to alert their immune system, reducing then their energy consumption [6,7]. The beneficial bacteria Bacillus spp. and Pseudomonas spp. have been reported to elicit ISR against pathogens with different lifestyles in various plant species through priming phenomenon [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. The primed plants express upregulation of defense related genes [15,16,17], generation of reactive oxygen species [18], reinforcement of cell walls via callose deposition [8,13], and accumulation of anti-microbial phytoalexins [11,19] after perception of pathogen-derived signal.

Salicylic acid (SA), jasmonate (JA), and ethylene (ET) have been documented as the major phytohormones involved in regulation of host immune response to pathogens with different lifestyles [20,21]. JA and ET signaling pathways are more important for resistance to necrotrophic fungi including Botrytis cinerea, while SA signaling is generally effective in response to biotrophs or hemibiotrophs, such as Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000. Collectively, the beneficial bacteria-mediated ISR seems to prioritize JA and ET signaling pathways that regulate PDF1.2 gene expression [5,13,16,17,22,23], whereas pathogen-induced SAR involves SA accumulation and PR1 expression [4,24]. Some beneficial microbes may also mediate ISR in SA-dependent manner and priming of PR1 gene expression upon pathogen challenge. For example, the Bacillus cereus AR156-mediated ISR against Pst DC3000 is simultaneously dependent on the activation of SA-responsive genes PR1, PR2, PR5, and JA/ET-responsive gene PDF1.2 [16]. Pseudomonas fluorescens SS101-mediated ISR against Pst DC3000 was impaired in SA deficient NahG plants, but remained comparable in JA- and ET-insensitive jar1 and ein2 mutants, respectively, compared to the wild type Col-0 [25]. The beneficial bacterium Bacillus subtilis FB17 also triggers ISR in Arabidopsis in a SA and ET dependent manner [26]. This revealed complex regulatory networks in the hormone signaling sectors triggered by different beneficial bacteria, that might affect the efficiency of ISR against pathogens.

More recently, abscisic acid (ABA) has also been identified as a regulator of plant immunity against pathogens [27,28,29,30]. ABA can also interact with SA, JA, and ET-regulated defenses, thereby modulating pathogen resistance [31,32,33]. ABA is involved in regulation of stomatal aperture, callose deposition, or expression of defense-related genes to restrict pathogen penetration [29,34,35]. It has also been reported that ABA-deficient mutants, aba3-1, aba2-1, failed to reduce stomatal aperture after pretreatment with B. subtilis FB17 inducing ISR [28] The impairment of stomatal closure was also observed in B. amyloliquefaciens FZB42-treated ABA-insensitive mutant abi1 [30]. The positive role of ABA in JA synthesis and induction of JA-responsive genes was also reported in Arabidopsis during interaction with the vascular oomycete Pythium irregular [36]. Moreover, priming defense response by β-aminobutyric acid (BABA) requires an ABA-dependent callose deposition upon pathogen challenge [27,37,38]. ABA has also been described as a negative regulator at the post-invasive penetration of pathogens through phytohormonal crosstalk [39,40]. Exogenous application of ABA leads to high susceptibility of Arabidopsis to Pst DC3000, which seems due to a negative effect on some defenses, such as inhibition of lignin biosynthesis, suppression of SA- and ET/JA-responsive genes [39,40].

In our previous research, we showed that both Bacillus subtilis PTA-271 and Pseudomonas fluorescens PTA-CT2 [41], trigger ISR in grapevine by priming plant immunity [11,18,19,42,43]. Nevertheless, whether priming is regulated by common or distinct immune pathways in B. subtilis- and P. fluorescens-mediated ISR against pathogens with different lifestyles remains to be elucidated. In this study, we first investigated the capacity of B. subtilis PTA-271 and P. fluorescens PTA-CT2 to trigger ISR against the necrotrophic fungus B. cinerea and the hemibiotrophic bacterium Pst DC3000 in Arabidopsis thaliana. We then examined the differences and similarities of B. subtilis and P. fluorescens-induced priming immune response and analyzed signaling pathways involved in ISR against pathogen infection. We especially focused on the expression of defense-related genes, phytohormone amounts, and the roles of SA, JA/ET, NPR1, and ABA signaling pathways in P. fluorescens- and B. subtilis-mediated ISR against B. cinerea and Pst DC3000.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant and Microbial Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Col-0 and its transgenic and mutant lines, including NahG (salicylic acid-deficient; [44], sid2 (SA synthesis-difficient2; [45], npr1 (SA-insensitive, nonexpressor of PR1; [46]), ein2.1 (ethylene-insensitive2.1), jar1.2 (jasmonic acid-insensitive1.2), and ABA insensitive mutants abi1.1 and abi2.1 [47] were obtained from the Salk Institute [48]. Seeds were sterilized in 50% sodium hypochlorite solution containing 0.2% Tween 20 for 10 min, rinsed five times with sterile distilled water, and kept at 4 °C for four days to promote uniform germination. The sterilized seeds were sown on soil under controlled conditions with 8 h light/16 h dark regime at a constant temperature of 22 °C. Two-week-old soil-grown seedlings were then transferred to individual 60-mL pots for 1 week before bacterial treatment.

B. subtilis PTA-271 (GenBank Nucleotide Accession No. AM293677) and P. fluorescens PTA-CT2 (GenBank Nucleotide Accession No. AM29367), isolated from grapevine plants [41] were cultivated overnight in sterile Luria Bertani (LB) liquid medium at 28 °C, under continuous shaking at 110 rpm. The bacterial pellets were then collected at the exponential growth phase by centrifugation at 4 °C, 5000 rpm for 20 min. The bacterial pellets were washed once and resuspended in sterilized 10 mM MgSO4, then adjusted to 1 × 109 CFU/mL for plant treatment.

Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (Pst DC3000) was grown overnight in sterile King Broth (KB) medium containing 50 mg/L rifampicin at 28 °C under continuous shaking at 180 rpm, then the pellets were collected at the exponential growth phase by centrifugation at 4 °C, 5000 rpm for 20 min. The pellets were then washed, resuspended in sterilized 10 mM MgSO4 and adjusted to 1 × 108 CFU/mL. Botrytis cinerea was grown on potato dextrose agar (PDA) at 28 °C for 2 weeks. Then fungal conidia were collected and resuspended in sterilized water, and filtrated to remove the mycelium and adjusted to 1 × 106 conidia [49].

2.2. Bacterial Treatment, Pathogen Infection, and Disease Assessment

Three-week-old plants were soil-drenched with B. subtilis or P. fluorescens to reach a final concentration of 1 × 108 CFU/g soil, or with MgSO4 as a mock treatment (control). Two weeks later, true rosette leaves of 5-week-old plants were infected with 10 µL droplets or by spraying B. cinerea at 1 × 106 conidia/mL or spraying Pst DC3000 at 1 × 108 CFU/mL. Disease symptoms were evaluated by determining the mean lesion diameter and percentage of diseased leaves in 20–30 plants per treatment at 4 days-post infection (dpi) with B. cinerea and Pst DC3000, respectively. Meanwhile, the pathogen growth was determined by analyzing the transcript level of B. cinerea Actin gene, and Pst DC3000 development was quantified on KB agar medium containing 50 mg/L rifampicin and 100 mg/L kanamycin after 48 h at 28 °C, and expressed as logarithmic scale of CFU per gram of fresh weight.

2.3. RNA Extraction and Analysis of Gene Expression by RT-qPCR

For each sample, 100 mg of leaves was ground in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was isolated using Extract’ All (Eurobio, Les Ulis, France) and cDNA was then synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA followed reverse transcription by using the Verso cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The transcript levels of target genes were determined by qPCR using the CFX 96TM Real Time System (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France) and the SYBR Green Master Mix PCR kit as recommended by the manufacturer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). PCR conditions were 95 °C for 15 s (denaturation) and 60 °C for 1 min (annealing/extension) for 40 cycles on CFX 96TM Real Time System (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France). Traditional reference genes were evaluated with Bio-Rad CFX MANAGER software v.3.0 (Actin2, UBQ5, UBQ10, EF1α, and Tubulin2) to select a reference gene with a stable expression in all tested conditions. The expression stability GeNorm M value of UBQ5 was below the critical value of 0.5 in Arabidopsis samples. Transcript levels of target genes were calculated using the standard curve method and normalized against UBQ5 gene as an internal control. For each experiment, PCR reactions were performed in duplicate and reference samples are leaves of untreated plants as the control sample. The specific primers used in this study were listed in Table S1 in Supplementary Material.

2.4. Phytohormone Analysis by LC-MS

Phytohormones were extracted from 20 mg of ground leaf powder in 1 mL of cold solution of methanol/water/formic acid (70/29/1: v/v/v). The homogenates were stirred at room temperature for 30 min, then centrifuged at 15,000× g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was evaporated under nitrogen and the residue was dissolved with 1 mL of a 2% formic acid solution. The extracts were purified using a solid phase extraction (SPE) Evolute express ABN 1 mL–30 mg (Biotage, Hengoed, UK). The eluate was evaporated to dry and reconstructed in 200 µL of H2O containing 0.1% of formic acid.

Phytohormones, salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and abscisic acid (ABA) were purchased from OlchemIn (Olomouc, Czech Republic, and the precursor of ethylene, 1-aminocyclopropane carboxylic acid (ACC) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint-Quentin-Fallavier, France). Phytohormones and ACC were analyzed by an UHPLC-MS/MS system as described in Lakkis et al. [11]. The analysis was achieved by a Nexera X2 UHPLC system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) coupled to a QTrap 6500+ MS (Sciex, ON, Canada) equipped with an IonDrive™ turbo V electrospray (ESI) source. Then, 2 µL of purified extract were injected into a Kinetex Evo C18 core-shell column (100 × 2.1 mm, 2.6 µm, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA) heated at 40 °C. Compounds were eluted using Milli-Q water (solvent A) and acetonitrile LCMS grade (Fisher Optima, Neots, UK) (solvent B), both containing 0.1% formic acid (LCMS grade) with a flow rate of 0.7 mL min−1. The gradient elution started with 1% B, 0.0–5.0 min 60% B, 5.0–5.5 min 100% B, 5.5–7.0 min 100 % B, 7.0–7.5 min 1% B, and 7.5–9.5 min 1% B. The ionization voltage was set to 5 kV for positive mode and −4.5 kV for negative mode producing mainly [M + H]+ and [M − H]−, respectively. The analysis was performed in scheduled MRM mode in positive and negative mode simultaneously with a polarity switching of 5 ms. Quantification was processed using MultiQuant software v3.0.2 (Sciex, ON, Canada).

2.5. Exogenous Application of ABA

Four-week-old Arabidopsis Col-0 was treated with 2% ethanol (control) or 100 µM ABA solution in 2% ethanol at the root level for 48 h. Then the leaves of control and ABA-treated plants were sprayed with Pst DC3000 at 1 × 108 CFU/mL or drop-inoculated with 5 µL of B. cinerea at 1 × 106 conidia/mL. The induced resistance was evaluated through disease incidence and disease severity measurement at four days-post infection as described below.

3. Results

3.1. B. subtilis and P. fluorescens Trigger ISR against Both B. cinerea and Pst DC3000

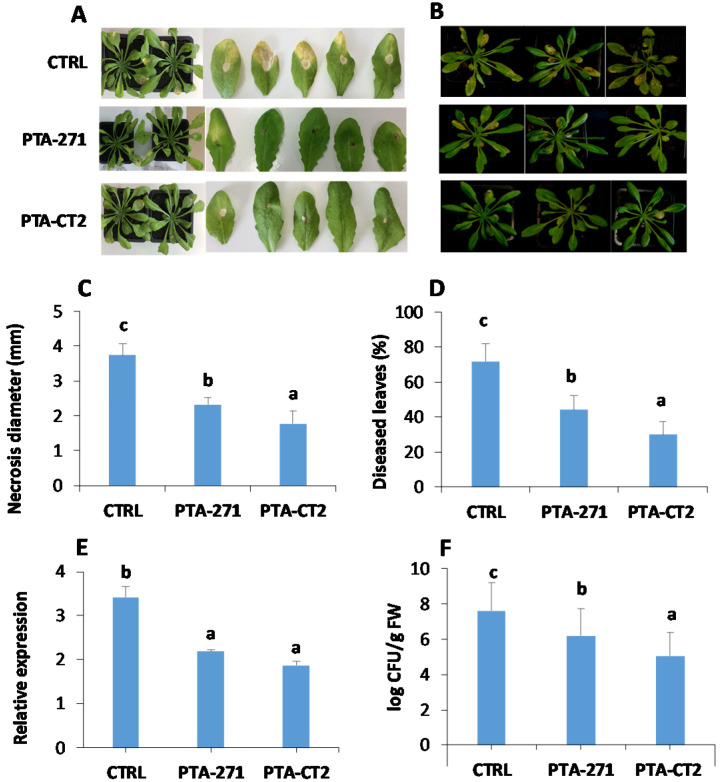

To explore whether B. subtilis PTA-271 and P. fluorescens PTA-CT2 enable to induce systemic resistance in Arabidopsis against the necrotroph B. cinerea and the hemibiotroph Pst DC3000, 5-week-old control and bacteria-treated Col-0 plants were drop inoculated with B. cinerea or sprayed with Pst DC3000. Our results showed that B. subtilis- and P. fluorescens-treated plants displayed a significant reduction of disease symptoms provoked by B. cinerea (Figure 1A) and Pst DC3000 (Figure 1B) in the leaves. B. subtilis- and P. fluorescens-treated plants exhibited 40% and over 50% protection against B. cinerea and 40% and 60% protection against Pst DC3000, respectively, compared to control (Figure 1C,D). The expression of B. cinerea Actin gene was significantly reduced in the leaves of the bacteria-treated plants (Figure 1E). Similarly, the CFU quantity of Pst DC3000 was substantially lowered in the leaves of B. subtilis- and P. fluorescens-inoculated plants compared to control (Figure 1F). This indicates that the root treatment with P. fluorescens and B. subtilis triggers a systemic resistance in Arabidopsis against B. cinerea and Pst DC3000. The higher efficiency was observed with P. fluorescens compared to B. subtilis in inducing ISR against both pathogens.

Figure 1.

Bacillus subtilis PTA-271 and Pseudomonas fluorescens PTA-CT2 induce systemic resistance against B. cinerea and Pst DC3000 in Arabidopsis. Plants were treated with each bacterium at 108 CFU g−1 soil or MgSO4 (control) at the root level for 2 weeks, then leaves were infected with B. cinerea or Pst DC3000. (A,B) Representative photographs depicting symptoms caused by B. cinerea and Pst DC3000 at 4 dpi. (C) B. cinerea disease incidence as the average of necrosis diameter spreading. (D) Pst DC3000 disease incidence as the percentage of diseased leaves. (E,F) The growth of B. cinerea and Pst DC3000 evaluated through the expression of B. cinerea Actin gene and logarithmic scale of Pst DC3000 CFU/g fresh weight, respectively. Data are means ± SE from at least three independent experiments with 16 plants/treatment (about 150 leaves). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (Duncan test, p < 0.05).

3.2. B. subtilis and P. fluorescens Prime Plants for Enhanced Expression of PR1, PR4, and PDF1.2 to Different Extents after Pathogen Infection

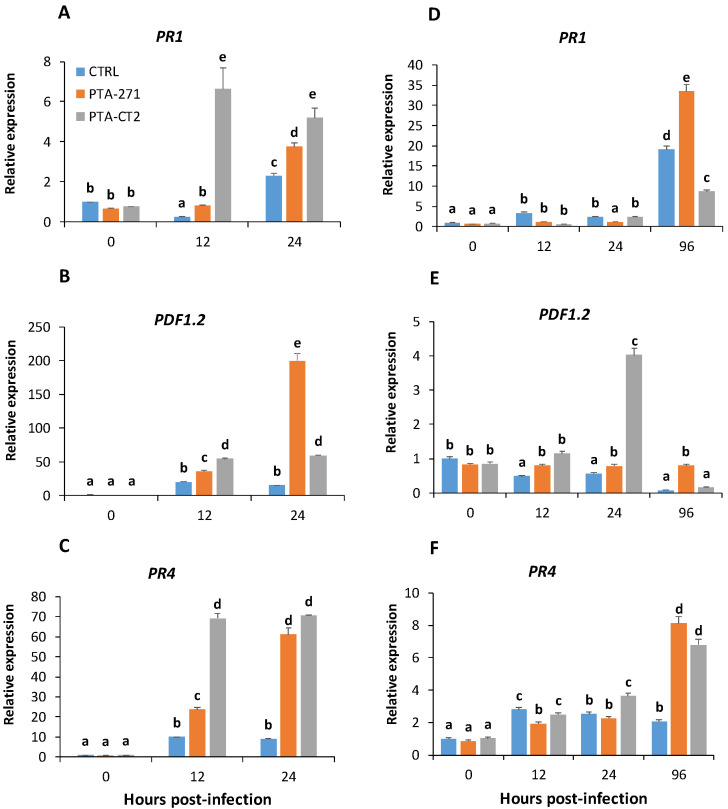

To gain more insight into the molecular mechanisms involved in B. subtilis and P. fluorescens-ISR against necrotrophic and hemibiotrophic pathogens, the transcript levels of PR1 (SA-responsive, [50]; PDF1.2 (ET/JA-responsive, [51] and PR4 (ET-inducible, [52] were examined in Arabidopsis leaves after infection with B. cinerea and Pst DC3000. The expression of these genes was monitored in control and bacteria-treated Col-0 plants at 0, 12, and 24 h-post-infection (hpi) with B. cinerea, and even up to 96 hpi with Pst DC3000. Data (Figure 2) showed that in the absence of pathogen (0 hpi), the bacteria alone did not induce any consistent change in gene expression. However, both P. fluorescens and B. subtilis primed plants for enhanced expression of all selected genes at 12 hpi of B. cinerea, except PR1 in B. subtilis-treated plants (Figure 2A–C). P. fluorescens strongly upregulated PR1, PDF1.2, and PR4 at 12 hpi in comparison with B. subtilis. However, this induction remained stable or slightly reduced at 24 hpi. With B. subtilis these genes were upregulated later and reached the peak at 24 hpi, especially for PDF1.2 that was approximately 4- and 10-times higher compared to P. fluorescens-treated and control plants, respectively (Figure 2B). The scale of PR4 and PDF1.2 expression was significantly higher than that of PR1 gene after B. cinerea infection. The maximum transcript value of PR1 was approximately 20- and 10-times lower than PDF1.2 and PR4 expression in B. subtilis- and P. fluorescens-treated plants, respectively (Figure 2A–C). These results indicate that ET and/or JA-inducible defense responses are likely to be more predominant than SA-dependent responses in resistance against B. cinerea. Data also revealed differential activation of gene expression by beneficial bacteria after Pst DC3000 infection. After bacterial treatment PR1 induction was the same as the control at 12 hpi, and even decreased in response to B. subtilis at 24 hpi. However, the expression of PR1 as for PR4 was preferably and highly upregulated by B. subtilis at 96 hpi, indicating that this bacterium can initially weaken SA immune response, but later activate both SA and ET defense pathways. Interestingly, P. fluorescens activated the expression of PDF1.2 and PR4 to a high extent at 24 and 96 hpi, respectively (Figure 2D–F). Data suggest a prominent role of PR4 in ISR against both necrotrophic and hemibiotrophic pathogens. P. fluorescens-treated plants activated sooner immune response to Pst DC3000 compared to B. subtilis. The expression of PR4 was also slightly induced, while that of PDF1.2 was about 4-times higher at 24 hpi in P. fluorescens-treated plants than in control (Figure 2E,F). PDF1.2 was significantly decreased, but a significant upregulation of PR4 was observed in P. fluorescens-treated plants at 96 hpi. Interestingly, the scale of PR1 expression was stronger than PR4 in B. subtilis-treated plants, indicating that SA-responsive defenses can play a crucial role in B. subtilis-ISR against Pst DC3000. Data also suggest that different mechanisms could be involved in ISR triggered by B. subtilis and P. fluorescens against the hemibiotrophic bacterium Pst DC3000.

Figure 2.

B. subtilis PTA-271 and P. fluorescens PTA-CT2 induce differential expression of defense-related genes in leaves of Col-0 plants after B. cinerea and Pst DC3000 infection. Five-week-old Col-0 were sprayed with B. cinerea and Pst DC3000, then the infected leaves were selected at 0, 12, and 24 hpi, Pst DC3000-infected leaves were additionally collected at 96 hpi. The UBQ5 gene was used as internal control, and leaves without infection of control plants correspond to reference samples (assigned as 1 fold). Expression of PR1, PR4, and PDF1.2 after B. cinerea (A–C) and Pst DC3000 (D–F) infection. The data are the mean ± SE from three independent experiments with total 12 plantlets/treatment. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (Duncan test p < 0.05).

3.3. B. subtilis and P. fluorescens Induce Differential Change in Phytohormone Amounts after Pathogen Challenge

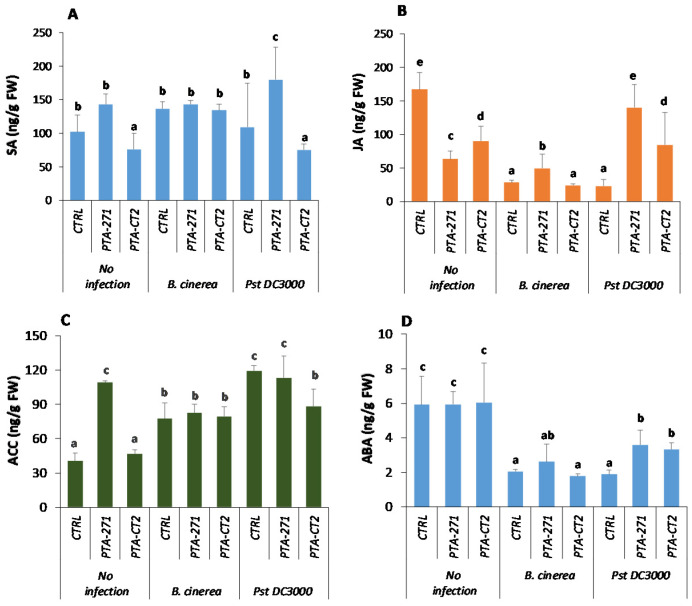

In order to investigate whether the expression of defense genes is associated with phytohormone accumulation at the systemic level, the amount of SA, JA, ACC (ET precursor), and ABA was quantified by LC-MS-MS in the leaves of P. fluorescens- and B. subtilis-treated plants before and after B. cinerea or Pst DC3000 infection. Data showed that in the absence of pathogen, the amounts of SA (Figure 3A) remained unchanged by B. subtilis, but decreased by P. fluorescens treatment. However, the JA content decreased in response to both bacteria (Figure 3B), while that of ABA (Figure 3D) remained stable. The ACC content (Figure 3C) increased by B. subtilis, but not by P. fluorescens. After infection with B. cinerea, the amount of phytohormones did not change in P. fluorescens-treated plants (Figure 3), whereas JA and ABA levels slightly increased in the leaves of B. subtilis-treated plants (Figure 3B,D). This indicates that upregulation of PR1 induced by both bacteria is not related to enhancement of SA production upon B. cinerea challenge. However, after Pst DC3000 infection, B. subtilis primed plants for increased level of SA (Figure 3A), whereas JA production was induced by both bacteria but more strongly by B. subtilis, with approximately 2-fold higher than with P. fluorescens (Figure 3B). In this condition, no increase of ACC level was observed among control and bacteria-treated plants, albeit P. fluorescens slightly decreased ACC accumulation after Pst DC3000 infection (Figure 3C). Data also showed that after pathogen infection, ABA content declined from 1.5- to 2-times compared to non-infected mock. P. fluorescens had no significant effect on the amount of ABA compared to control plants after B. cinerea infection, while the ABA content increased by approximately 2-fold after Pst DC3000 infection (Figure 3D). This indicates that P. fluorescens-induced ABA synthesis depends on the pathogen lifestyle, while B. subtilis-treated plants accumulated ABA after infection with both pathogens.

Figure 3.

B. subtilis PTA-271 and P. fluorescens PTA-CT2 induce differential accumulation of phytohormones in Col-0 plants upon B. cinerea and Pst DC3000 challenge. Salicylic acid (A), jasmonic acid (B), 1-aminocyclopropane-carboxyliate (C), and abscisic acid (D) were quantified in control and infected leaves at 48 h-post infection of treated and non-treated plants. Data are mean ± SE from three independent experiments with a total of nine plants/treatment, each treatment with three technical repetitions. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (Duncan test p < 0.05).

3.4. B. subtilis and P. fluorescens Mediated ISR through Different Signaling Pathways

3.4.1. Role of SA, JA and ET Signaling in ISR against B. cinerea and Pst DC3000

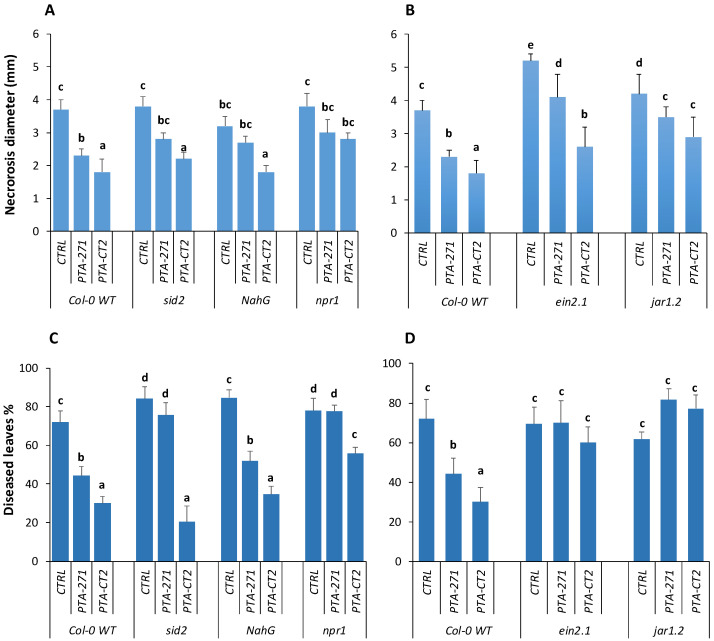

Here, we compared the effectiveness of P. fluorescens and B. subtilis in inducing ISR in the wild type Col-0 and transgenic or mutant lines NahG, sid2, npr1, jar1.2, and ein2.1. The results showed that sid2 and NahG plants failed to fully express the ISR triggered by B. subtilis after B. cinerea infection compared to Col-0 (Figure 4A). The necrotic size caused by B. cinerea in the leaves of NahG and sid2 was significantly larger than that in Col-0 plants, indicating that SA influences the efficiency of B. subtilis-ISR against this fungus. Although NahG expressed the same level of ISR as Col-0 plants by B. subtilis, sid2 mutant completely lost the resistance against Pst DC3000, suggesting that SA is also essential for B. subtilis-ISR against this pathogen (Figure 4C). However, P. fluorescens mounted equal level of ISR against both pathogens in NahG and sid2 as Col-0, suggesting that P. fluorescens-ISR is independent on SA signaling pathway. In addition, both P. fluorescens- and B. subtilis-treated npr1 mutants were more susceptible to B. cinerea and Pst DC3000 compared to bacteria-treated Col-0 plants (Figure 4A,C). However, bacteria-treated npr1 plants, especially with P. fluorescens, appeared more resistant than non-treated mutant npr1. This suggests that P. fluorescens- and B. subtilis-triggered ISR is partially control by SA an NPR1, but other factors are also playing an important role in this immunity against B. cinerea and Pst DC3000.

Figure 4.

B. subtilis PTA-271 and P. fluorescens PTA-CT2-induced systemic resistance in Col-0 and its mutants sid2, NahG, npr1, ein2.1, and jar1.2 plants against B. cinerea and Pst DC3000. Three-week-old Col-0, transgenic NahG and mutant plants sid2, nrp1, ein2.1, and jar1.2 were pretreated with B. subtilis PTA-271 or P. fluorescens PTA-CT2 for 2 weeks. Then the leaves were infected with B. cinerea and Pst DC3000. The induced systemic resistance (ISR) was determined at 4 dpi by measuring necrosis size caused by B. cinerea (A,B) and the percent of diseased leaves by Pst DC3000 (C,D). Data are means ± SE from four independent experiments with a total of 16 plants/treatment (about 150 leaves). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (Duncan test p < 0.05).

The non-treated mutant ein2.1 (Figure 4B) showed a high susceptibility to B. cinerea compared to non-treated Col-0. Furthermore, necrotic sizes were 1.5–2-times larger in P. fluorescens- and B. subtilis-treated ein2.1, respectively, compared to Col-0. This indicates that the ET signaling pathway is required for P. fluorescens- and B. subtilis-ISR against the necrotroph B. cinerea. Similarly, despite over 20% reduction of necrotic size of B. cinerea observed in bacteria-treated jar1.2 plants, the ISR level triggered by P. fluorescens and B. subtilis against B. cinerea was not fully expressed in this mutant compared to Col-0, suggesting an important role of JA in regulating ISR by the two bacteria. Against Pst DC3000, the level of ISR induced by P. fluorescens and B. subtilis was completely discarded in ein2.1 and jar1.2 (Figure 4D). The percentage of diseased leaves of non-treated and bacteria-treated ein2.1 and jar1.2 was over 60% as observed in non-treated Col-0 plants. Data highlight a prominent role JA and ET signaling pathways in P. fluorescens- and B. subtilis-ISR against Pst DC3000.

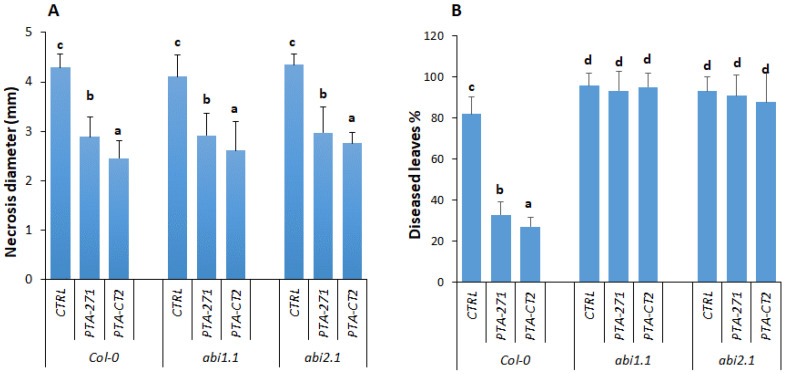

3.4.2. ABA Signaling Is Required for ISR against Pst DC3000, but not against B. cinerea

To understand whether ABA is involved in ISR against Pst DC3000 or B. cinerea, we compared the P. fluorescens- and B. subtilis-ISR effectiveness in Col-0 and its ABA-insensitive mutants abi1.1 and abi2.1. Our data provided evidence that both abi1.1 and abi2.1 plants still expressed P. fluorescens- and B. subtilis-ISR against B. cinerea as in Col-0 plants (Figure 5A). The necrotic size provoked by B. cinerea in Col-0, abi1.1, and abi2.1 remained comparable in both control and bacteria-treated plants. This indicates that ABA signaling was not required for ISR against B. cinerea, although ABA content was slightly increased by B. subtilis after B. cinerea infection. However, the loss of ABI1.1 and ABI2.1 function in the mutants strongly compromised ISR against Pst DC3000 in P. fluorescens- and B. subtilis-treated plants (Figure 5B). The mutant abi1.1 and abi2.1 showed around 90% of diseased leaves regardless bacterial treatment, while the percentage of diseased leaves in the bacteria-treated Col-0 was 3-fold lower than those in control plants, suggesting that both ABA concentration and signaling might be required for ISR against Pst DC3000.

Figure 5.

B. subtilis PTA-271 and P. fluorescens PTA-CT2-induced systemic resistance in Col-0 and its mutants abi1.1 and abi2.1 plants against B. cinerea and Pst DC3000. Three-week-old Col-0 and mutant plants abi1.1 and abi2.1 were pretreated with PTA-271 or PTA-CT2 suspensions for 2 weeks. Then the leaves were infected with B. cinerea and Pst DC3000. The ISR was determined at 4 dpi by measuring necrosis diameter caused by B. cinerea (A) and diseased leaves provoked by Pst DC3000 (B). Data are means ± SE from four independent experiments with a total of 16 plants/treatment (about 150 leaves). Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (Duncan test p < 0.05).

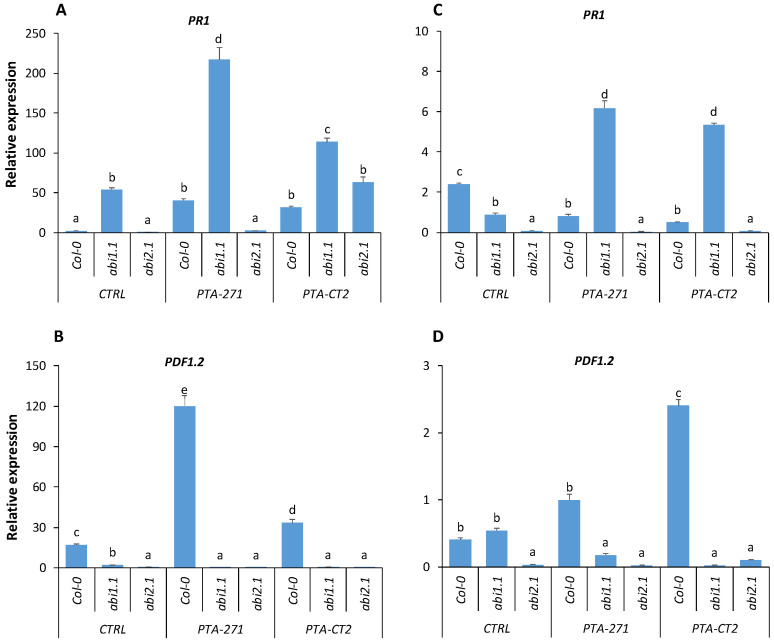

3.4.3. Loss of ABA Signaling in abi1.1 and abi2.1 Affects Defense Responses against Pathogens

To investigate whether ABA signaling can affect immune response after pathogen infection, we compared the expression of PR1 and PDF1.2 genes in Col-0 and ABA insensitive mutants abi1.1, abi2.1 after infection with B. cinerea and Pst DC3000. In B. cinerea-infected plants only abi1.1 showed a high PR1 expression compared to the control and abi2.1 (Figure 6A). B. subtilis also failed to potentiate the expression of PR1 in abi2.1, while in abi1.1 mutant PR1 was significantly upregulated after infection with Pst DC3000 (Figure 6B). Meanwhile, the enhanced expression of PDF1.2 during P. fluorescens-ISR against Pst DC3000 was impaired in abi1.1 and abi2.1 plants (Figure 6D), highlighting a link between the strong reduction of PDF1.2 expression in P. fluorescens-treated abi1.1 and abi2.1 and their susceptibility to Pst DC3000. Surprisingly, although the expression of PR1 was strongly primed by B. subtilis in abi1.1 and significantly reduced in abi2.1 (Figure 6A), these mutants still expressed similar ISR level against B. cinerea as in Col-0 plants. Likewise, both P. fluorescens and B. subtilis were unable to increase expression of PDF1.2 in abi1.1 and abi2.1 (Figure 6C), but no significant difference was observed in P. fluorescens- and B. subtilis-ISR against B. cinerea in Col-0, abi1.1, and abi2.1 plants (Figure 2A).

Figure 6.

Expression of PR1 and PDF1.2 genes in leaves of control, B. subtilis PTA-271-, and P. fluorescens PTA-CT2-treated Col-0, abi1.1, and abi2.1 after pathogen infection. The expression of PR1 and PDF1.2 genes was analyzed at 24 hpi with B. cinerea (A,B) and Pst DC3000 (C,D) in Col-0 and abi1.1, abi2.1 plants. Data are mean ± SE from the pool of three independent experiments with 12 plants/treatment. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences (Duncan test, p < 0.05).

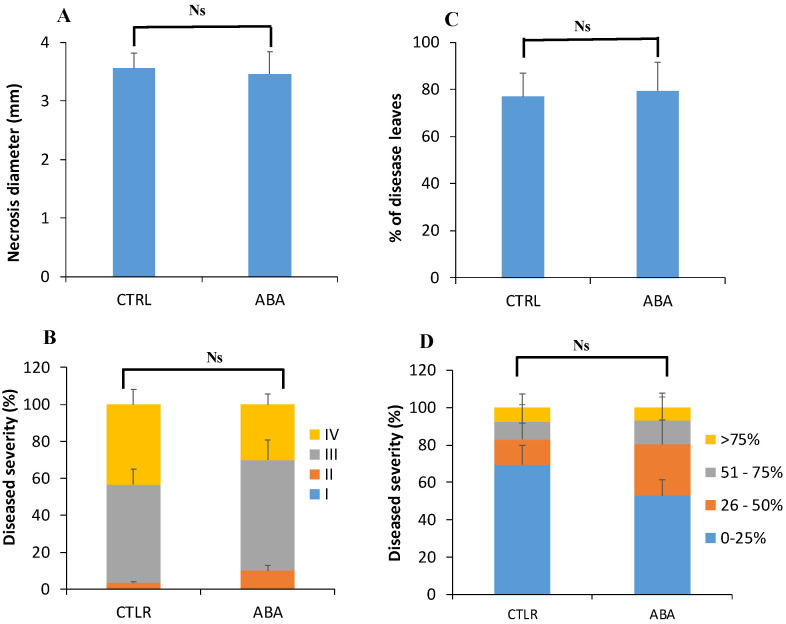

3.4.4. Root Treatment with Exogenous ABA Prior to Inoculation Has No Effect on ISR against B. cinerea and Pst DC3000

To test whether ABA effect is due to its concentration or not, exogenous ABA was applied at the root level of Col-0 plants and systemic resistance was assessed at 4 dpi with B. cinerea and Pst DC3000. Data showed that root treatment with ABA had no effect on systemic resistance against both pathogens. As for the control, ABA-treated plants displayed strong spread symptoms caused by B. cinerea (Figure 7A), and expressed approximately 80% of diseased leaves by Pst DC3000 (Figure 7B). No significant difference was observed in disease severity between control and ABA-treated plants upon B. cinerea and Pst DC3000 challenge (Figure 7C,D).

Figure 7.

Effects of exogenous abscisic acid (ABA) on the induced resistance against B. cinerea and Pst DC3000 in Arabidopsis. Col-0 plants were treated with 100 µM ABA solution at the root level. After 48 h, the leaves were drop-inoculated with B. cinerea or sprayed with Pst DC3000. Disease incidence and severity caused by B. cinerea (A,B) and Pst DC3000 (C,D) were assessed at 4 days post infection. Data are mean ± SE from three repetitions with 12 plants/treatment. Ns indicates no significant difference (Duncan test, p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

In this study, we showed that B. subtilis PTA-271 and P. fluorescens PTA-CT2 are able to trigger an efficient protection against both the necrotrophic fungus B. cinerea and the hemibiotrophic bacterium Pst DC3000 in Arabidopsis. The effectiveness of P. fluorescens-ISR is mostly higher than B. subtilis-ISR against both pathogens. It is plausible to assume that different mechanisms could be involved in P. fluorescens- and B. subtilis-ISR against the pathogens. In both cases, ISR is based on priming immune response after perception of pathogen-derived signal, rather than a direct elicitation effect. This is in line with other reports indicating that ISR is linked to the priming plants for enhanced immune system only after pathogen challenge, saving the plant from a high energy consumption [6,7]. It is also suspected that B. subtilis and P. fluorescens prime at least partially distinct signaling defense pathways that result in different levels of ISR [5,8,13]. A clear difference between B. subtilis- and P. fluorescens-ISR is that they target distinct defense-related genes and signaling pathways depending on the pathogen. P. fluorescens significantly upregulated the expression of PR1, PR4, and PDF1.2 at the early stage of B. cinerea infection, compared to B. subtilis that induced higher expression of PDF1.2 at the later stage. This highlights the importance of earlier primed ET/JA-responsive defenses for enhanced efficiency of ISR against the necrotrophic fungus. The upregulation of PR1 gene in bacteria-treated plants upon B. cinerea challenge suggests the dependency of ISR on the SA signaling pathway. This is in line with the findings of Nie et al. [13], showing that B. cereus AR156 primed Arabidopsis for enhanced expression of the PR1 gene after B. cinerea infection. A substantially lower scale of PR1 transcript was also observed compared to those of PR4 and PDF1.2 upon B. cinerea challenge, indicating the requirement of JA/ET-responsive defenses in ISR against this pathogen.

The phytohormone analysis suggests that beneficial bacteria differentially affect hormonal status before infection. P. fluorescens did not impact either ACC or ABA levels, but reduced SA and JA content in leaf tissues. B. subtilis also reduced JA level, while it induced a significant accumulation of ACC without impact on SA and ABA. It is therefore suggested that bacteria may confer a hormonal homeostasis, thus prime plants for enhanced resistance upon subsequent pathogen infection. It seems that the induced resistance by P. fluorescens was more dependent on JA/ET signaling rather than hormonal concentration, as reported earlier [53,54]. Although P. fluorescens did not cause any change in the amount of JA and ACC after B. cinerea infection, a significant increase of PDF1.2 expression occurred. Meanwhile, B. subtilis induced an increase in JA content, and primed plants for the strongest expression of PDF1.2 after challenge with B. cinerea. Interestingly, the P. fluorescens-ISR against Pst DC3000 is associated with enhanced expression of PDF1.2, but not of PR1, whereas B. subtilis primed plants for upregulation of PR1, but not PDF1.2 after Pst DC3000 infection. In both cases, the expression of PR4 was upregulated, indicating that ISR against the hemibiotrophic Pst DC3000 share similar ET-dependent signaling components [55]. It is noteworthy that P. fluorescens triggered a sooner and stronger expression of defense-related genes at early stage of Pst DC3000 infection, compared to B. subtilis. However, B. subtilis activated later a high expression of PR1 and PR4 genes, indicating the prominent role of SA-dependent immune response in ISR against Pst DC3000, as also observed with B. cereus and P. fluorescens SS101 [14,16,25]; B. subtilis PTA-271 also increased the amounts of SA and JA after Pst DC3000 infection, suggesting that this beneficial bacterium can also modulate SA-JA crosstalk by prioritizing SA-dependent immune response after Pst DC3000 infection, as observed with P. fluorescens SS101 (van de Mortel et al., 2012). It has also been reported that Pst DC3000 can produce the phytotoxin coronatine, which mimics a bioactive JA conjugate and targets JA-receptor COI1, resulting in an activation of JA-dependent response and suppression of SA-inducible defense response [56,57,58].

Functional analyses also point to the involvement of SA signaling in B. subtilis-ISR, but not in P. fluorescens-ISR against B. cinerea, since mutant sid2 and transgenic NahG plants (both SA deficient) failed to express the B. subtilis-ISR, but not P. fluorescens-ISR against B. cinerea, compared to Col-0. Similarly, B. subtilis-mediated ISR against Pst DC3000 was abolished in sid2 mutant but not in NahG plants, suggesting that SA is involved in B. subtilis-ISR against this bacterium. The phenotypic difference between NahG and sid2 after Pst DC3000 infection could be related to different basal level of SA in these mutants [59], since NahG plants express a SA hydrolase to degrade SA to catechol, while sid2 is unable to synthesize SA due to lack of isochorismate synthase 1. Our data are also consistent with the finding that ISR triggered by Paenbacillus alvei K165 was impaired in SA-signaling eds5 and sid2 mutants, but still fully expressed in NahG transgenic plants [60]. In contrast, P. fluorescens triggered SA-independent ISR against Pst DC3000. This highlights a distinct dependency of SA signaling by P. fluorescens and B. subtilis to mediated ISR against both necrotroph and hemibiotroph pathogens. It has been reported that in Arabidopsis, SA can serve as a precursor for synthesis of SA-containing siderophores by rhizospheric bacteria in iron-limiting conditions [61,62]. ISR induced by several Bacillus strains also required the SA signaling pathway [63].

We also showed that both P. fluorescens and B. subtilis failed to mediate ISR against B. cinerea and Pst DC3000 in npr1, jar1.2, and ein2.1 mutants. This result is consistent with most studies, highlighting the functional role of JA/ET and NPR1 in ISR triggered by both beneficial bacteria against the pathogens. This also suggests a prominent function of NPR1 in SA-dependent or independent ISR [5]. NPR1 functions downstream with SA- and JA/ET-signaling pathways, leading to activation of transcription factors and defense-related genes, such as PR1 and PDF1.2 [20]. SA- and JA/ET-dependent ISR induced by B. cereus AR156 required NPR1 after Pst DC3000 infection [16]. In B. subtilis PTA-271-treated plants, NPR1 might play a role as a mediator of SA-JA crosstalk, resulting in priming both SA- and ET/JA-responsive genes following infection with B. cinerea. Our results showed that ein2.1 and jar1.2 mutants were unable to express a full ISR mediated by P. fluorescens PTA-CT2 and B. subtilis PTA-271 against B. cinerea and Pst DC3000. However, roles of JA and ET signaling seem to be more prioritized in the ISR against Pst DC3000.

The role of ABA in priming plant immune response by beneficial microbes is so far obscure and even unknown. Here, we showed that the amount of ABA was significantly increased in B. subtilis PTA-271-treated plants after infection with both B. cinerea and Pst DC3000, while it was accumulated only in P. fluorescens PTA-CT2-ISR against Pst DC3000, but not B. cinerea. This indicates that ABA can play a positive role in ISR depending on beneficial strain and pathogen lifestyle. ABA can act downstream SA signaling to suppress stomatal reopening induced by pathogens, inhibiting pathogenic penetration [28,30,64,65]. Pst DC3000-induced stomatal reopening was strongly suppressed by B. subtilis FB17, thus minimizing the bacteria entry [28]. The increase of ABA level during B. subtilis-ISR could be related to its interaction with the SA signaling pathway upon Pst DC3000 infection [14,15,16]. Interestingly, a significant difference was observed between P. fluorescens PTA-CT2 and B. subtilis PTA-271 in inducing ABA accumulation after B. cinerea infection, suggesting that ABA concentration can contribute to ISR against the pathogens. Moreover, before pathogen infection the higher level of ABA in P. fluorescens- and B. subtilis-treated plants did not seem to play such an important role for the subsequent ISR against pathogens. This suggests that P. fluorescens and B. subtilis are likely to modulate interaction between ABA and SA or ET/JA signaling pathways, thus abolishing the negative effect of ABA in ISR against pathogens.

Using ABA-insensitive mutants, we showed that ABA plays predominant role in regulating ISR against Pst DC3000, but not B. cinerea. Loss of ABA function in abi1.1 and abi2.1 plants did not cause any consistent change in ISR level against B. cinerea. This suggests that both P. fluorescens- and B. subtilis-ISR share the ABA-independent pathway, albeit these bacteria induced different levels of ABA accumulation upon B. cinerea challenge. However, ABA was found to be determinant for both P. fluorescens- and B. subtilis-mediated ISR against Pst DC3000. Mutation of ABA signaling in abi1.1 and abi2.1 results in impaired ISR by both bacteria toward Pst DC3000. This is in line with the demonstration that inhibition of ABA signaling can cause stomatal reopening induced by Pst DC3000 [30,34], which is essential in early stages of pathogenic penetration [34,36]. Since the abi mutants actually do contain normal amounts of ABA as the wild type, it is conceivable that other ABA signaling components are involved in ISR including independent modulation of the guard cell outward-rectifying potassium channel (GORK) [66]. Such a mechanism may implicate ABA in the direct and rapid stomatal responses to the onset of pathogenic infection. Further investigations are needed to decipher the ABA signaling components in the regulation of priming immune response. It is suggested that both P. fluorescens and B. subtilis require ABA signaling at least via the ABI receptor for ISR against the hemibiotroph Pst DC3000 rather than the necrotroph B. cinerea. Experiments showed that the loss BI2.1 function, but not of ABI1.1, compromised the expression of PR1, resulting in a reduction of B. subtilis-ISR against Pst DC3000. This effect may be linked to a significant downregulation of JA/ET-responsive PDF1.2 gene, supporting the role of JA/ET in ISR against pathogens [5,13,14]. However, exogenous application of ABA at the root level did not show any significant change in ISR induced by both bacteria, suggesting that ISR is more sensitive to ABA signaling rather than ABA concentration.

Overall, this study clearly reports that B. subtilis PTA-271 and P. fluorescens PTA-CT2 prime common and distinct immune responses resulting in differential effectiveness of ISR against pathogens. P. fluorescens seems to potentiate rapid and strong defense responses at the early stage of the pathogen infection, triggering an efficient resistance compared to B. subtilis. Both B. subtilis- and P. fluorescens-ISR share JA/ET and NPR1-dependent defenses as prioritized immune pathways against B. cinerea. However, B. subtilis-ISR against Pst DC3000 is dependent on SA, JA/ET, and NPR1 pathways, while P. fluorescens-ISR is independent on SA pathway. ABA signaling, but not ABA concentration, also plays an important role along with JA/ET signaling in primed systemic immunity by beneficial bacteria against Pst DC3000, but not against B. cinerea.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to J.-F. Guise for his help with the plant production and Isabelle Roberrini for her technical assistance. This work used the scientific material and facilities supported by the University of Reims.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/8/3/503/s1, Table S1: Primer sequences of the different genes used in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.H.N., P.T.-A., F.B. and A.A.; methodology, N.H.N., P.T.-A., S.V., F.R., A.S., E.N.-O., F.B. and A.A.; validation, F.B. and A.A.; formal analysis, N.H.N., S.V., F.R., E.N.-O., F.B. and A.A.; investigation, P.T.-A., C.C., F.B. and A.A.; data curation, F.B. and A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, N.H.N., P.T.-A., F.B. and A.A.; writing—review and editing, A.A.; supervision, P.T.-A., F.B. and A.A.; funding acquisition, E.N.-O. and A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the State-Region Planning Contracts (CPER) and European Regional Development Fund (FEDER). The grant of N-H Nguyen was funded by Campus France and the Vietnamese Government.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Vleeshouwers V.G.A.A., Oliver R.P. Effectors as tools in disease resistance breeding against biotrophic, hemibiotrophic, and necrotrophic plant pathogens. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2014;27:196–206. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-10-13-0313-IA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones A.M., Dangl J.L. The plant immune system. Nature. 2006;444:323–329. doi: 10.1038/nature05286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katagiri F., Tsuda K. Understanding the Plant Immune System. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2010;23:1531–1536. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-04-10-0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fu Z.Q., Dong X. Systemic Acquired Resistance: Turning Local Infection into Global Defense. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013;64:839–863. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pieterse C.M., Zamioudis C., Berendsen R.L., Weller D.M., Van Wees S.A., Bakker P.A. Induced Systemic Resistance by Beneficial Microbes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2014;52:347–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-082712-102340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conrath U., Beckers G.J.M., Langenbach C., Jaskiewicz M. Priming for Enhanced Defense. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2015;53:97–119. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080614-120132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinez-Medina A., Flors V., Heil M., Mauch-Mani B., Pieterse C.M., Pozo M.J., Ton J., Van Dam N.M., Conrath U. Recognizing Plant Defense Priming. Trends Plant Sci. 2016;21:818–822. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahn I.-P., Lee S.-W., Kim M.G., Park S.-R., Hwang D.-J., Bae S.-C. Priming by rhizobacterium protects tomato plants from biotrophic and necrotrophic pathogen infections through multiple defense mechanisms. Mol. Cells. 2011;32:7–14. doi: 10.1007/s10059-011-2209-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alizadeh H., Behboudi K., Ahmadzadeh M., Javan-Nikkhah M., Zamioudis C., Pieterse C.M., Bakker P.A. Induced systemic resistance in cucumber and Arabidopsis thaliana by the combination of Trichoderma harzianum Tr6 and Pseudomonas sp. Ps14. Biol. Control. 2013;65:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2013.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Y., Yan F., Chai Y., Liu H., Kolter R., Losick R., Guo J. Biocontrol of tomato wilt disease by Bacillus subtilis isolates from natural environments depends on conserved genes mediating biofilm formation. Environ. Microbiol. 2012;15:848–864. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02860.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lakkis S., Trotel-Aziz P., Rabenoelina F., Schwarzenberg A., Nguema-Ona E., Clément C., Aziz A. Strengthening Grapevine Resistance by Pseudomonas fluorescens PTA-CT2 Relies on Distinct Defense Pathways in Susceptible and Partially Resistant Genotypes to Downy Mildew and Gray Mold Diseases. Front. Plant Sci. 2019;10:10. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lucas J.A., Garcia-Cristobal J., Bonilla A., Ramos-Solano B., Gutiérrez-Mañero J. Beneficial rhizobacteria from rice rhizosphere confers high protection against biotic and abiotic stress inducing systemic resistance in rice seedlings. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2014;82:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nie P., Li X., Wang S., Guo J., Zhao H., Niu D. Induced Systemic Resistance against Botrytis cinerea by Bacillus cereus AR156 through a JA/ET- and NPR1-Dependent Signaling Pathway and Activates PAMP-Triggered Immunity in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:238. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Timmermann T., Armijo G., Donoso R., Seguel A., Holuigue L., González B. Paraburkholderia phytofirmans PsJN Protects Arabidopsis thaliana Against a Virulent Strain of Pseudomonas syringae Through the Activation of Induced Resistance. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2017;30:215–230. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-09-16-0192-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahn I.-P., Lee S.-W., Suh S.-C. Rhizobacteria-Induced Priming in Arabidopsis Is Dependent on Ethylene, Jasmonic Acid, andNPR1. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2007;20:759–768. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-7-0759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niu N.-D., Liu H.-X., Jiang C., Wang Y.-P., Wang Q.-Y., Jin H., Guo J. The Plant Growth–Promoting Rhizobacterium Bacillus cereus AR156 Induces Systemic Resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana by Simultaneously Activating Salicylate- and Jasmonate/Ethylene-Dependent Signaling Pathways. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2011;24:533–542. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-09-10-0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Verhagen B.W.M., Glazebrook J., Zhu T., Chang H.-S., Van Loon L.C., Pieterse C.M. The Transcriptome of Rhizobacteria-Induced Systemic Resistance in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2004;17:895–908. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2004.17.8.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verhagen B.W.M., Trotel-Aziz P., Couderchet M., Höfte M., Aziz A. Pseudomonas spp.-induced systemic resistance to Botrytis cinerea is associated with induction and priming of defence responses in grapevine. J. Exp. Bot. 2009;61:249–260. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aziz A., Verhagen B., Magnin-Robert M., Couderchet M., Clément C., Jeandet P., Trotel-Aziz P. Effectiveness of beneficial bacteria to promote systemic resistance of grapevine to gray mold as related to phytoalexin production in vineyards. Plant Soil. 2015;405:141–153. doi: 10.1007/s11104-015-2783-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pieterse C.M., Van Der Does D., Zamioudis C., Leon-Reyes A., Van Wees S.A. Hormonal Modulation of Plant Immunity. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2012;28:489–521. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang Y., Ahammed G.J., Wu C., Fan S.-Y., Zhou Y. Crosstalk among Jasmonate, Salicylate and Ethylene Signaling Pathways in Plant Disease and Immune Responses. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2015;16:450–461. doi: 10.2174/1389203716666150330141638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pieterse C.M., Van Pelt J.A., Van Wees S.A., Ton J., Léon-Kloosterziel K.M., Keurentjes J.J., Verhagen B.W., Knoester M., Van Der Sluis I., Bakker P.A., et al. Rhizobacteria-mediated Induced Systemic Resistance: Triggering, Signalling and Expression. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2001;107:51–61. doi: 10.1023/A:1008747926678. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Der Ent S., Van Hulten M., Pozo M.J., Czechowski T., Udvardi M.K., Pieterse C.M., Ton J. Priming of plant innate immunity by rhizobacteria and β-aminobutyric acid: Differences and similarities in regulation. New Phytol. 2009;183:419–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klessig D.F., Choi H.W., Dempsey D.A. Systemic Acquired Resistance and Salicylic Acid: Past, Present, and Future. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2018;31:871–888. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-03-18-0067-CR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Van De Mortel J.E., De Vos R.C.H., Dekkers E., Pineda A., Guillod L., Bouwmeester K., Van Loon J.J., Dicke M., Raaijmakers J.M. Metabolic and Transcriptomic Changes Induced in Arabidopsis by the Rhizobacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens SS101. Plant Physiol. 2012;160:2173–2188. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.207324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rudrappa T., Biedrzycki M.L., Kunjeti S.G., Donofrio N.M., Czymmek K.J., Paul W.P., Bais H.P. The rhizobacterial elicitor acetoin induces systemic resistance inArabidopsis thaliana. Commun. Integr. Biol. 2010;3:130–138. doi: 10.4161/cib.3.2.10584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flors V., Ton J., Van Doorn R., Jakab G., García-Agustín P., Mauch-Mani B. Interplay between JA, SA and ABA signalling during basal and induced resistance against Pseudomonas syringae and Alternaria brassicicola. Plant J. 2007;54:81–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar A.S., Lakshmanan V., Caplan J.L., Powell D., Czymmek K.J., Levia D.F., Bais H.P. RhizobacteriaBacillus subtilisrestricts foliar pathogen entry through stomata. Plant J. 2012;72:694–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05116.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ton J., Flors V., Mauch-Mani B. The multifaceted role of ABA in disease resistance. Trends Plant Sci. 2009;14:310–317. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu L., Huang Z., Li X., Ma L., Gu Q., Wu H., Liu J., Borriss R., Wu Z., Gao X. Stomatal Closure and SA-, JA/ET-Signaling Pathways Are Essential for Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42 to Restrict Leaf Disease Caused by Phytophthora nicotianae in Nicotiana benthamiana. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:847. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Proietti S., Caarls L., Coolen S., Van Pelt J.A., Van Wees S.A., Pieterse C.M.J. Genome-wide association study reveals novel players in defense hormone crosstalk in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Environ. 2018;41:2342–2356. doi: 10.1111/pce.13357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shigenaga A.M., Berens M.L., Tsuda K., Argueso C.T. Towards engineering of hormonal crosstalk in plant immunity. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017;38:164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2017.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vos I.A., Moritz L., Pieterse C.M.J., Van Wees S.A. Impact of hormonal crosstalk on plant resistance and fitness under multi-attacker conditions. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:639. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melotto M., Underwood W., He S.Y. Role of Stomata in Plant Innate Immunity and Foliar Bacterial Diseases. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2008;46:101–122. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.121107.104959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sah S.K., Reddy K.R., Li J. Abscisic Acid and Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Crop Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:571. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adie B.A., Pérez-Pérez J., Pérez-Pérez M.M., Godoy M., Sánchez-Serrano J.J., Schmelz E.A., Solano R. ABA Is an Essential Signal for Plant Resistance to Pathogens Affecting JA Biosynthesis and the Activation of Defenses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:1665–1681. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.García-Andrade J., Ramírez V., Flors V., Vera P. Arabidopsis ocp3 mutant reveals a mechanism linking ABA and JA to pathogen-induced callose deposition. Plant J. 2011;67:783–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ton J., Mauch-Mani B. β-amino-butyric acid-induced resistance against necrotrophic pathogens is based on ABA-dependent priming for callose. Plant J. 2004;38:119–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anderson J.P., Badruzsaufari E., Schenk P.M., Manners J.M., Desmond O.J., Ehlert C., MacLean D.J., Ebert P., Kazan K. Antagonistic Interaction between Abscisic Acid and Jasmonate-Ethylene Signaling Pathways Modulates Defense Gene Expression and Disease Resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2004;16:3460–3479. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.025833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mohr P.G., Cahill D. Suppression by ABA of salicylic acid and lignin accumulation and the expression of multiple genes, in Arabidopsis infected with Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2006;7:181–191. doi: 10.1007/s10142-006-0041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trotel-Aziz P., Couderchet M., Biagianti S., Aziz A. Characterization of new bacterial biocontrol agents Acinetobacter, Bacillus, Pantoea and Pseudomonas spp. mediating grapevine resistance against Botrytis cinerea. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2008;64:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2007.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gruau C., Trotel-Aziz P., Villaume S., Rabenoelina F., Clément C., Baillieul F., Aziz A. Pseudomonas fluorescens PTA-CT2 triggers local and systemic immune response against Botrytis cinerea in grapevine. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2015;28:1117–1129. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-04-15-0092-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Verhagen B., Trotel-Aziz P., Jeandet P., Baillieul F., Aziz A. Improved Resistance Against Botrytis cinerea by Grapevine-Associated Bacteria that Induce a Prime Oxidative Burst and Phytoalexin Production. Phytopathology. 2011;101:768–777. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-09-10-0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Delaney T.P., Uknes S., Vernooij B., Friedrich L., Weymann K., Negrotto D., Gaffney T., Gut-Rella M., Kessmann H., Ward E., et al. A Central Role of Salicylic Acid in Plant Disease Resistance. Science. 1994;266:1247–1250. doi: 10.1126/science.266.5188.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wildermuth M.C., Dewdney J., Wu G., Ausubel F.M. Isochorismate synthase is required to synthesize salicylic acid for plant defence. Nature. 2001;414:562–565. doi: 10.1038/35107108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cao H., Bowling S.A., Gordon A.S., Dong X. Characterization of an Arabidopsis mutant that is nonresponsive to inducers of systemic acquired resistance. Plant Cell. 1994;6:1583–1592. doi: 10.2307/3869945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Merlot S., Gosti F., Guerrier D., Vavasseur A., Giraudat J. The ABI1 and ABI2 protein phosphatases 2C act in a negative feedback regulatory loop of the abscisic acid signalling pathway. Plant J. 2001;25:295–303. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2001.00965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alonso J.M., Hirayama T., Roman G., Nourizadeh S., Ecker J.R. EIN2, a Bifunctional Transducer of Ethylene and Stress Responses in Arabidopsis. Science. 1999;284:2148–2152. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5423.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aziz A., Poinssot B., Daire X., Adrian M., Bézier A., Lambert B., Joubert J.M., Pugin A. Laminarin elicits defence responses in grapevine and induces protection against Botrytis cinerea and Plasmopara viticola. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2003;16:1118–1128. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2003.16.12.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vlot A.C., Dempsey D.A., Klessig D.F. Salicylic Acid, a Multifaceted Hormone to Combat Disease. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2009;47:177–206. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.050908.135202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Verhagen B.W.M., Van Loon L.C., Pieterse C.M.J. Induced disease resistance signaling in plants. Floric. Ornam. Plant Biotechnol. 2006;3:334–343. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Potter S. Regulation of a Hevein-like Gene in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 1993;6:680. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-6-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pieterse C.M.J., Van Pelt J.A., Ton J., Parchmannb S., Mueller M.J., Buchala A.J., Métrauxc J.-P., Van Loon L.C. Rhizobacteria-mediated induced systemic resistance (ISR) in Arabidopsis requires sensitivity to jasmonate and ethylene but is not accompanied by an increase in their production. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2000;57:123–134. doi: 10.1006/pmpp.2000.0291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Van Wees S.A., Luijendijk M., Smoorenburg I., Van Loon L.C., Pieterse C.M. Rhizobacteria-mediated induced systemic resistance (ISR) in Arabidopsis is not associated with a direct effect on expression of known defense-related genes but stimulates the expression of the jasmonate-inducible gene Atvsp upon challenge. Plant Mol. Biol. 1999;41:537–549. doi: 10.1023/A:1006319216982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van Der Ent S., Verhagen B.W., Van Doorn R., Bakker D., Verlaan M.G., Pel M.J., Joosten R.G., Proveniers M.C., Van Loon L., Ton J., et al. MYB72 Is Required in Early Signaling Steps of Rhizobacteria-Induced Systemic Resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:1293–1304. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.113829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brooks D.M., Bender C.L., Kunkel B.N. The Pseudomonas syringae phytotoxin coronatine promotes virulence by overcoming salicylic acid-dependent defences in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2005;6:629–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2005.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Geng X., Jin L., Shimada M., Kim M.G., Mackey D. The phytotoxin coronatine is a multifunctional component of the virulence armament of Pseudomonas syringae. Planta. 2014;240:1149–1165. doi: 10.1007/s00425-014-2151-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ishiga Y. Studies on mode of action of phytotoxin coronatine produced by Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2017;83:424–426. doi: 10.1007/s10327-017-0748-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abreu M.E., Munné-Bosch S. Salicylic acid deficiency in NahG transgenic lines and sid2 mutants increases seed yield in the annual plant Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2009;60:1261–1271. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tjamos S.E., Flemetakis E., Paplomatas E.J., Katinakis P. Induction of Resistance to Verticillium dahliae in Arabidopsis thaliana by the Biocontrol Agent K-165 and Pathogenesis-Related Proteins Gene Expression. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2005;18:555–561. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-18-0555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Audenaert K., Pattery T., Cornelis P., Höfte M. Induction of Systemic Resistance toBotrytis cinereain Tomato byPseudomonas aeruginosa7NSK2: Role of Salicylic Acid, Pyochelin, and Pyocyanin. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2002;15:1147–1156. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2002.15.11.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.De Vleesschauwer D., Djavaheri M., Bakker P.A., Höfte M. Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS374r-Induced Systemic Resistance in Rice against Magnaporthe oryzae Is Based on Pseudobactin-Mediated Priming for a Salicylic Acid-Repressible Multifaceted Defense Response. Plant Physiol. 2008;148:1996–2012. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.127878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barriuso J., Solano B.R., Gutiérrez Mañero F.J. Protection against pathogen and salt stress by four plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria isolated from Pinus sp. on Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytopathology. 2008;98:666–672. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-98-6-0666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Melotto M., Underwood W., Koczan J., Nomura K., He S.Y. Plant Stomata Function in Innate Immunity against Bacterial Invasion. Cell. 2006;126:969–980. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zeng W., He S.Y. A Prominent Role of the Flagellin Receptor FLAGELLIN-SENSING2 in Mediating Stomatal Response to Pseudomonas syringae pv tomato DC3000 in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2010;153:1188–1198. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.157016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ooi A., Lemtiri-Chlieh F., Wong A., Gehring C.A. Direct Modulation of the Guard Cell Outward-Rectifying Potassium Channel (GORK) by Abscisic Acid. Mol. Plant. 2017;10:1469–1472. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.