Abstract

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is still one of the most aggressive and lethal cancer types due to the late diagnosis, high metastatic potential, and drug resistance. The development of novel therapeutic strategies is urgently needed. KRAS (Kirsten rat sarcoma 2 viral oncogene homolog) is the major driver mutation gene for PDAC tumorigenesis. In this study, we mined cancer genomics data and identified a common KRAS-driven gene signature in PDAC, which is related to cell–cell and cell–extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions. Higher expression of this gene signature was associated with poorer overall survival of PDAC patients. Connectivity Map (CMap) analysis and drug sensitivity profiling predicted that a clinically approved JAK2 (Janus kinase 2)-selective inhibitor, fedratinib (also known as TG-101348), could reverse the KRAS-driven gene signature and exhibit KRAS-dependent anticancer activity in PDAC cells. As an approved treatment for myelofibrosis, the pharmacological and toxicological profiles of fedratinib have been well characterized. It may be repurposed for treating KRAS-driven PDAC in the future.

Keywords: bioinformatics, drug repurposing, gene signature, histone deacetylase inhibitor, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

1. Introduction

The occurrence of pancreatic cancer has significantly ascended throughout the past decade. Among them, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) accounts for most cases of pancreatic cancer, with its survival rate being lower than 8% [1,2]. The death rate is highly correlated with high incidence of metastasis, recurrence rate, and chemoresistance. Due to late diagnosis of most clinical cases, the aggressive type was often accompanied by angiogenesis and metastasis, resulting in high unresectable clinical cases [3,4]. Gemcitabine-based chemotherapies, alone or in combination with other drugs such as nab-paclitaxel and FOLFIRINOX (a combination of fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin), are the first-line treatment for locally advanced or metastatic PDAC. However, past clinical results often showed poor prognosis and unsatisfactory drug efficacy [4,5]. Therefore, a more profound knowledge of PDAC biology will help to develop more effective anticancer strategies.

PDAC is usually driven by mutations of the proto-oncogene and tumor suppressor genes, such as KRAS (Kirsten rat sarcoma 2 viral oncogene homolog), TP53 (tumor protein p53), SMAD4 (SMAD family member 4), CDKN2A (cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 2A), and others [6,7]. Because KRAS is the most common mutated driver gene in PDAC, it is considered an ideal therapeutic target. However, KRAS remains undruggable for the past three decades due to the failure of the development of effective KRAS inhibitors [8]. A breakthrough is the development of KRASG12C (glycine 12 to cysteine)-specific inhibitors, MRTX849 and AMG-510 [9,10]. At the end of 2019, the latter has been granted a fast track designation by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating metastatic non-small-cell lung carcinoma with the KRASG12C mutation [11]. Another exciting drug is the first oral pan-KRAS inhibitor, BI-1701963, which has been in a phase I clinical trial alone or in combination with the MEK (mitogen-activated protein/extracellular signal-regulated kinase) inhibitor, trametinib, for KRAS-mutated solid tumors (NCT04111458; https://clinicaltrials.gov/). The successes of KRAS inhibitors make targeting KRAS-mutated PDAC possible in the near future.

In this study, we mined bioinformatics resources and identified a common PDAC gene signature that was driven by KRAS, but not by TP53, mutation. This gene signature was associated with the regulation of cell–cell and cell–extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions. The reversion of this gene signature by a clinically approved JAK2 (Janus kinase 2) inhibitor, fedratinib (also known as TG-101348), may provide therapeutic benefit for KRAS-mutated PDAC patients.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of the Differentially Expressed Genes

The microarray data sets (GSE15471 [12,13], GSE16515 [14,15,16], GSE32676 [17,18], GSE62452 [19], and GSE101448 [20]) containing normal and cancerous pancreatic tissue samples were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) [21]. The differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were prepared using the R-based web application, GEO2R [21]. The Venn diagram was generated using the InteractiVenn (http://www.interactivenn.net/) [22]. The heat map was generated using the Morpheus (https://software.broadinstitute.org/morpheus).

2.2. Pathway Enrichment and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

Pathway enrichment was performed using the WebGestalt (http://www.webgestalt.org/) [23] and STRING (http://string-db.org/) [24] web-based tools. For WebGestalt analysis, the gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) method was used to analyze the following functional databases: Gene Ontology (GO) biological processes [25,26], Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways [27], and cancer hallmarks [28]. For STRING analysis, the settings were as follows: active interaction source = experiments and databases; minimum required interaction score = medium confidence (0.400); and max number of interactors to show = none. The enrichment of the PDAC gene signature in these microarray data sets (GSE33323 [29], GSE58055 [30], GSE53659 [31], GSE67358 [32], GSE123646 [33]) was performed using the GSEA v3.0 software (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/ [34,35]).

2.3. Cancer Genomics Analysis via the cBioPortal Website

The cBioPortal (http://www.cbioportal.org/) is a website to access, analyze, and visualize the large-scale TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) cancer genomics data sets or other studies [36,37]. The “Pancreatic adenocarcinoma (TCGA, PanCancer Atlas)” dataset of 168 PDAC patients containing complete genetic status (mutation, copy number variation, and mRNA expression) was used in this study to compare the association between gene mutations and PDAC gene signature. In addition, a Kaplan–Meier survival plot was generated using the cBioPortal to investigate the impact of PDAC gene signature on patients’ overall survival.

2.4. Connectivity Map Analysis

The Connectivity Map (CMap; https://clue.io/) database contains numerous gene signatures from cultured human cancer cell lines treated with drugs [38]. It is believed that a drug has the potential for treating a disease if this drug could reverse the disease-associated gene signature [39,40]. To identify the potential drugs to reverse PDAC gene signature, the commonly upregulated 53 genes were inputted to query the CMap database. The results were visualized as a heat map with a connectivity score between −100 and 100 corresponding to the magnitude of dissimilarity and similarity between queried and existing gene signatures.

2.5. Drug Sensitivity Profiling in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Cell Lines

The correlations between KRAS gene expression and drug sensitivity in PDAC cancer cell lines were obtained from the CellMinerCDB (https://discover.nci.nih.gov/cellminercdb/ [41]). The Cancer Therapeutics Response Portal (CTRP [42,43,44]) data from the Broad Institute of Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Harvard (Cambridge, MA, USA) were used.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of a Common Gene Signature in Human Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma

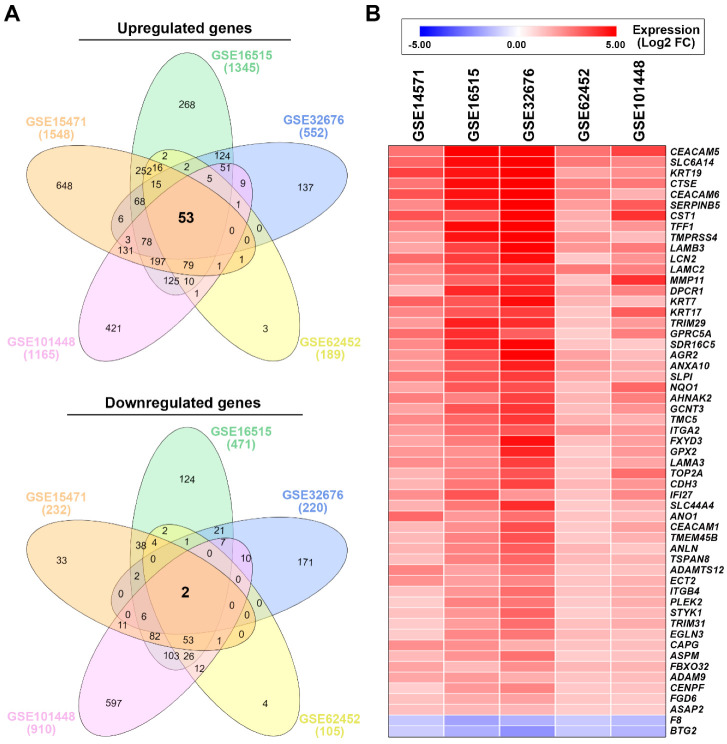

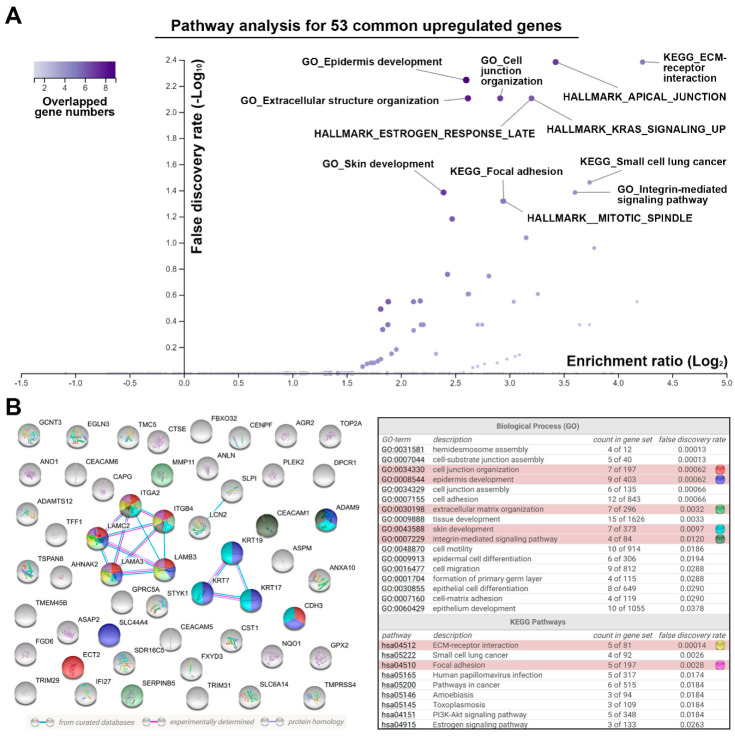

To identify the common gene signature associated with PDAC, five microarray data sets (Table 1) were obtained from the NCBI-GEO database [21]. Then, the DEGs were prepared using the R-based web application, GEO2R [21]. These DEGs (Supplementary Material, File S1) were analyzed using the InteractiVenn web-based tool [22]. As shown in the Venn diagrams (Figure 1A), we identified 53 upregulated and 2 downregulated genes that were common in PDAC tissues when compared with the adjacent normal tissues (Figure 1A). Their expression levels are listed in Table 2 and visualized in a heat map (Figure 1B). To investigate the potential role of this common gene signature, pathway enrichment for the 53 upregulated genes was performed using the WebGestalt web-based tool [23] against GO biological processes [25,26], KEGG pathways [27], and cancer hallmarks [28]. We found that pathways related to cell–cell and cell–ECM interactions were significantly enriched, such as KEGG_ECM-receptor interaction, KEGG_Focal adhesion, HALLMARK_APICAL_JUNCTION, GO_Cell junction organization, GO_Integrin-mediated signaling pathway, and GO_Extracellular structure organization (Figure 2A). The network for the 53 upregulated genes was further constructed and functional enrichment was performed for GO biological processes and KEGG pathways using the STRING database [24]. As shown in Figure 2B, ITGA2, ITGB4, LAMA3, LAMC2, LAMB3, and GPRC5A genes formed a major cluster, which participated in ECM-receptor interaction, focal adhesion, cell junction organization (together with CDH3 and ECT2 genes), and extracellular organization (together with SERPINB5 and MMP11 genes). Therefore, the alteration of genes related to cell–cell and cell–ECM interactions is a common gene signature in PDAC.

Table 1.

Microarray data sets from human pancreatic cancer patients.

| Access Number | Platform | # of Cases | # of DEGs 1 | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Tumor | Up | Down | |||

| GSE15471 | HG-U133_Plus_2 2 | 39 | 39 | 1548 | 232 | [12,13] |

| GSE16515 | HG-U133_Plus_2 | 16 | 36 | 1345 | 471 | [14,15,16] |

| GSE32676 | HG-U133_Plus_2 | 7 | 25 | 552 | 220 | [17,18] |

| GSE62452 | HG-U133_Plus_2 | 61 | 69 | 189 | 105 | [19] |

| GSE101448 | Illumina_HT-12_V4 3 | 19 | 24 | 1165 | 910 | [20] |

1 Differentially expressed genes (DEGs): adjusted p value <0.05 and fold change (FC) >1. 2 Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array. 3 Illumina HumanHT-12 V4.0 expression BeadChip.

Figure 1.

The common gene signature in human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. (A) The Venn diagrams show the overlapped gene numbers among five microarray data sets. (B) The heat map shows the relative expression for the common gene signature.

Table 2.

The common gene signature in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and the gene FC values.

| GSE15471 | GSE16515 | GSE32676 | GSE62452 | GSE101448 | Average FC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEACAM5 | 2.77 | 6.25 | 6.81 | 2.79 | 3.68 | 4.46 |

| SLC6A14 | 3.01 | 4.63 | 5.88 | 2.66 | 2.39 | 3.71 |

| KRT19 | 3.71 | 4.47 | 6.22 | 1.83 | 2.22 | 3.69 |

| CTSE | 2.73 | 4.62 | 5.12 | 2.55 | 2.69 | 3.54 |

| CEACAM6 | 3.35 | 4.53 | 5.79 | 2.42 | 1.56 | 3.53 |

| SERPINB5 | 2.32 | 4.39 | 5.62 | 1.97 | 3.22 | 3.50 |

| CST1 | 3.35 | 3.04 | 4.90 | 1.65 | 3.96 | 3.38 |

| TFF1 | 2.40 | 4.68 | 5.06 | 1.51 | 2.12 | 3.15 |

| TMPRSS4 | 1.96 | 4.50 | 5.76 | 2.06 | 1.36 | 3.13 |

| LAMB3 | 1.79 | 3.67 | 4.87 | 2.08 | 2.64 | 3.01 |

| LCN2 | 2.89 | 3.79 | 4.59 | 1.12 | 2.15 | 2.91 |

| LAMC2 | 2.18 | 3.55 | 3.59 | 2.65 | 2.51 | 2.90 |

| MMP11 | 2.05 | 3.05 | 4.16 | 1.23 | 3.99 | 2.90 |

| DPCR1 | 1.35 | 4.15 | 4.23 | 1.78 | 2.47 | 2.80 |

| KRT7 | 3.11 | 3.29 | 4.65 | 1.49 | 1.34 | 2.77 |

| KRT17 | 2.38 | 3.27 | 3.77 | 1.18 | 3.20 | 2.76 |

| TRIM29 | 2.00 | 4.30 | 4.06 | 1.28 | 2.01 | 2.73 |

| GPRC5A | 2.85 | 4.05 | 3.14 | 1.01 | 2.53 | 2.72 |

| SDR16C5 | 2.32 | 4.18 | 4.78 | 1.20 | 1.07 | 2.71 |

| AGR2 | 2.05 | 3.37 | 4.83 | 1.86 | 1.36 | 2.69 |

| ANXA10 | 2.01 | 3.25 | 4.32 | 1.94 | 1.70 | 2.64 |

| SLPI | 2.67 | 3.31 | 3.79 | 1.73 | 1.61 | 2.62 |

| NQO1 | 1.80 | 3.28 | 3.45 | 1.31 | 2.98 | 2.56 |

| AHNAK2 | 2.54 | 2.48 | 3.71 | 1.51 | 2.54 | 2.56 |

| GCNT3 | 1.85 | 3.35 | 3.93 | 1.34 | 2.15 | 2.52 |

| TMC5 | 2.36 | 3.00 | 3.86 | 1.55 | 1.55 | 2.46 |

| ITGA2 | 2.00 | 2.83 | 3.29 | 2.14 | 2.02 | 2.46 |

| FXYD3 | 1.80 | 2.59 | 4.57 | 1.32 | 1.91 | 2.44 |

| GPX2 | 2.07 | 2.18 | 4.20 | 1.07 | 2.01 | 2.31 |

| LAMA3 | 2.26 | 2.33 | 3.75 | 1.24 | 1.81 | 2.28 |

| TOP2A | 1.51 | 2.46 | 3.36 | 1.16 | 2.86 | 2.27 |

| CDH3 | 1.50 | 2.68 | 3.65 | 1.43 | 2.07 | 2.27 |

| IFI27 | 2.24 | 3.33 | 2.10 | 1.23 | 2.36 | 2.25 |

| SLC44A4 | 1.56 | 2.68 | 4.06 | 1.08 | 1.55 | 2.18 |

| ANO1 | 2.97 | 2.03 | 2.83 | 1.20 | 1.36 | 2.08 |

| CEACAM1 | 1.42 | 2.24 | 3.47 | 1.10 | 1.84 | 2.01 |

| TMEM45B | 1.41 | 2.49 | 3.39 | 1.12 | 1.54 | 1.99 |

| ANLN | 1.52 | 2.44 | 3.18 | 1.47 | 1.15 | 1.95 |

| TSPAN8 | 1.30 | 2.48 | 3.02 | 1.39 | 1.49 | 1.94 |

| ADAMTS12 | 2.42 | 1.87 | 2.69 | 1.14 | 1.25 | 1.87 |

| ECT2 | 2.18 | 1.93 | 2.40 | 1.19 | 1.55 | 1.85 |

| ITGB4 | 1.23 | 2.09 | 2.87 | 1.23 | 1.63 | 1.81 |

| PLEK2 | 1.01 | 2.47 | 2.71 | 1.09 | 1.64 | 1.78 |

| STYK1 | 1.25 | 2.08 | 3.05 | 1.03 | 1.42 | 1.77 |

| TRIM31 | 1.06 | 1.97 | 2.84 | 1.27 | 1.68 | 1.76 |

| EGLN3 | 1.06 | 2.38 | 2.70 | 1.39 | 1.25 | 1.76 |

| CAPG | 2.23 | 2.23 | 1.62 | 1.22 | 1.30 | 1.72 |

| ASPM | 1.38 | 2.17 | 2.80 | 1.03 | 1.21 | 1.72 |

| FBXO32 | 1.82 | 1.39 | 2.21 | 1.45 | 1.51 | 1.68 |

| ADAM9 | 1.76 | 2.00 | 1.65 | 1.20 | 1.33 | 1.59 |

| CENPF | 1.00 | 2.03 | 2.44 | 1.12 | 1.24 | 1.57 |

| FGD6 | 1.26 | 1.68 | 1.87 | 1.18 | 1.07 | 1.41 |

| ASAP2 | 1.27 | 1.44 | 1.47 | 1.03 | 1.04 | 1.25 |

| F8 | −1.11 | −1.83 | −1.56 | −1.07 | −1.37 | −1.39 |

| BTG2 | −1.02 | −1.61 | −2.17 | −1.12 | −1.51 | −1.49 |

Figure 2.

Pathway enrichment for the common upregulated genes in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by the WebGestalt (A) and STRING database (B) web-based tools. Inset at top left in (A): a gradient color key shows the overlapped gene numbers in a pathway. In the volcano plot of (A), the purple circles for HALLMARK_ESTROGEN_RESPONSE_LATE/HALLMARK_KRAS_ SIGNALING_UP or KEGG_Focal adhesion/HALLMARK_MITOTIC_SPINDLE were overlapped. In the left part of (B), line colors indicate the types of interaction evidence. The cyan and pink lines indicate protein–protein interactions from curated and experimental data, respectively. The purple line indicates that two protein molecules share structural homology. Functional enrichment (gene ontology (GO) biological processes and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways) in this network are shown in the right part of (B). Selected GO biological processes and KEGG pathways are highlighted with different colors. The term “count in gene set” indicates the overlapped genes (the first number) in a pathway (the second number). The term “false discovery rate” indicates the average rate of false coverage for the functional enrichment.

3.2. The Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Gene Signature Was Associated with KRAS and TP53 Gene Mutations

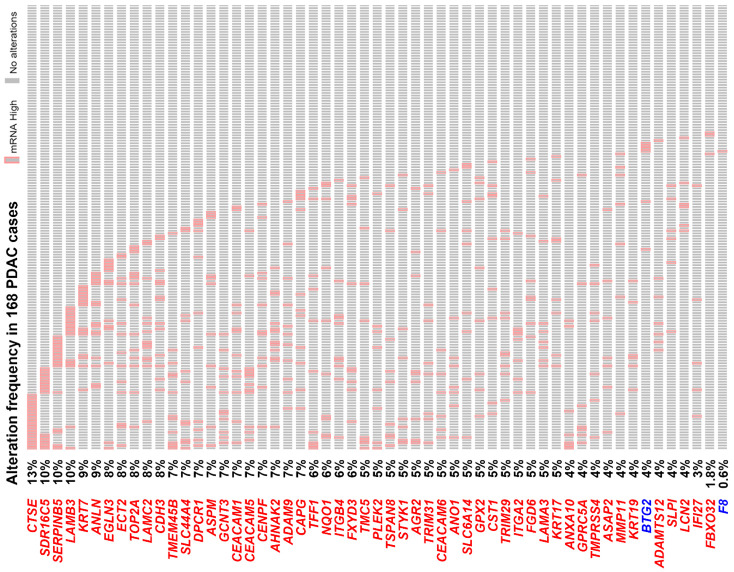

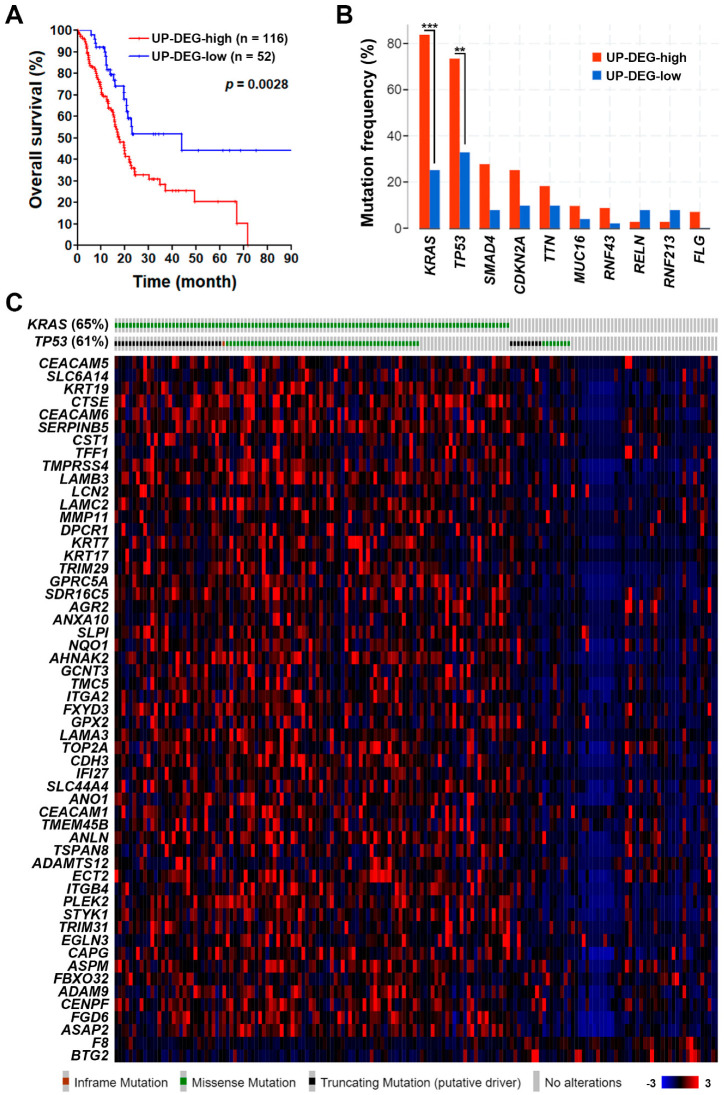

To further confirm the role of PDAC gene signature, the TCGA-PAAD (pancreatic adenocarcinoma) data set with 168 PDAC cases was used to compare their mRNA levels. As shown in Figure 3, most of them have higher mRNA expressions, especially for the 10 genes related to cell–cell and cell–ECM interactions: LAMB3 (10%), SERPINB5 (10%), CDH3 (8%), ECT2 (8%), LAMC2 (8%), ITGB4 (6%), ITGA2 (5%), LAMA3 (5%), GPRC5A (4%), and MMP11 (4%). PDAC patients with the higher gene signature (53 upregulated genes only) expression have poorer overall survival (Figure 4A). In addition, we found that the upregulation of PDAC gene signature was significantly associated with KRAS and TP53 gene mutations (Figure 4B,C). According to the TCGA-PAAD data set, 110 (65%) and 102 (61%) of the 168 PDAC cases harbored KRAS and TP53 gene mutations, respectively (Figure 4B). Given the fact that KRAS and TP53 were the most two common mutated genes in PDAC [6,7], it is reasonable that the PDAC gene signature may be driven by KRAS and TP53 gene mutations during tumorigenesis.

Figure 3.

A waterfall plot for the common gene signature expression in “The Cancer Genome Atlas—Pancreatic adenocarcinoma” data set. Genes highlighted in red or blue color indicate those commonly upregulated or downregulated in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) patients, respectively. The cases highlighted in red grids (labeled as “mRNA High”) indicate those with mRNA expression higher than that of the average patient (z-score >2).

Figure 4.

The association of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma gene signature with patients’ overall survival and gene mutations. (A) A Kaplan–Meier plot shows the association of 53 common upregulated genes (UP-DEG) with PDAC patients’ overall survival. The term “UP-DEG-high” indicates patients with higher mRNA expression (z-score >2) of any one of the 53 common upregulated genes. The remaining patients are classified as “UP-DEG-low” cases. (B) The association of 53 common upregulated genes (UP-DEG) with PDAC patients’ gene mutation status. (C) A heat map shows the association of PDAC gene signature with KRAS and TP53 mutations. Inset at bottom right: a gradient color key shows the related gene z-scores.

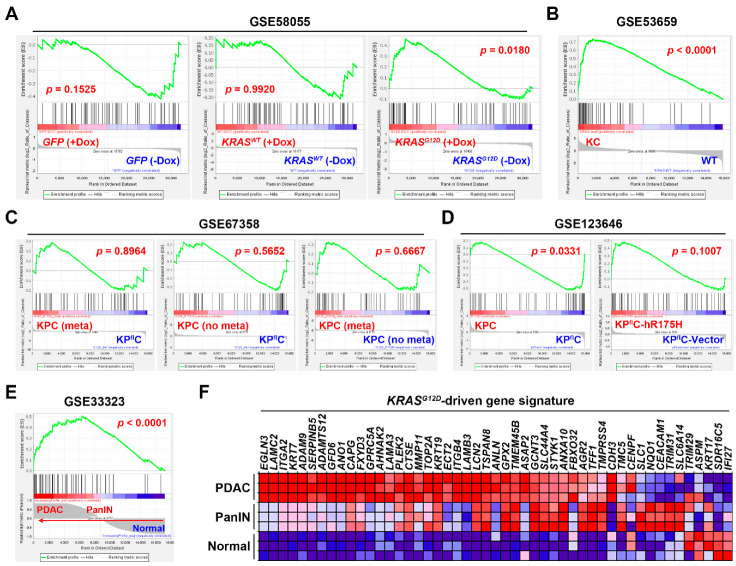

3.3. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis Revealed That the Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Gene Signature Was Driven by KRAS Gene Mutation

To further investigate whether the PDAC gene signature was driven by KRAS and TP53 gene mutations, the effect of KRASG12D (glycine 12 to aspartate) or TP53R175H (arginine 175 to histidine; the human equivalent of mouse Trp53R172H) mutations on PDAC gene signature was analyzed by GSEA using the relevant microarray data sets (Table 3). In GSE58055 [30], a doxycycline (Dox)-inducible KRASG12D mutation was introduced into the E6/E7-transformed human pancreatic ductal epithelial (HPDE) cells, in which the E6 and E7 proteins of the HPV16 virus inactivate p53 and RB, respectively [45,46]. We found that the PDAC gene signature was only enriched in HPDE cells with KRASG12D induction by Dox, but not in cells with the induction of wild-type (WT) KRAS or green fluorescent protein (GFP) control vector (Figure 5A), suggesting that the PDAC gene signature can be driven by KRASG12D mutation. To confirm the above observation, another microarray data set GSE53659 [31] with the KrasG12D-driven PDAC in mice (Pdx1-Cre/KrasG12D/+; also known as KC mice) was used. As shown in Figure 5B, the PDAC gene signature was enriched in KRASG12D-driven PDAC cells compared with that in the WT cells. Therefore, the PDAC gene signature is indeed driven by KRASG12D mutation.

Table 3.

Microarray data sets from KRAS-mutant and TP53 (Trp53)-mutant cells.

| Access Number | Platform | Samples | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| GSE58055 | Agilent SurePrint G3 Human Gene Expression 8x60K v2 Microarray | Immortalized HPDE-E6/E7 cells stably transfected with a doxycycline (Dox)-inducible KRASWT (n = 4) or KRASG12D (n = 6) plasmid, or a control GFP vector (n = 6). | [30] |

| GSE53659 | Affymetrix Mouse Genome 430 2.0 Array | Normal pancreas from WT mice (n = 5); PDAC cells from KC (Pdx1-Cre/KrasG12D/+) mice (n = 6) | [31] |

| GSE67358 | Affymetrix Mouse Genome 430 2.0 Array | Metastatic (n = 7) and non-metastatic (n = 7) PDAC cells from KPC (Pdx1-Cre/KrasG12D/+/Trp53R172H/+) mice; PDAC cells (n = 5) from KPflC (Pdx1-Cre/KrasG12D/+/Trp53-/+) mice. | [32] |

| GSE123646 | Affymetrix Mouse Genome 430 2.0 Array | KPC (n = 3) and KPflC (n = 3) PDAC cells; KPflC PDAC cells transfected with either a human TP53R175H plasmid (n = 3) or a control vector (n = 3). | [33] |

| GSE33323 | Affymetrix Mouse Gene 1.0 ST Array | Normal pancreas (n = 3), pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN; n = 3) and PDAC (n = 3) from KC mice | [29] |

Figure 5.

The association between KRAS/TP53 gene mutations and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma gene signature. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed to enrich the PDAC gene signature in the following data sets. (A) GSE58055: HPDE-E6/E7 cells stably transfected with doxycycline (Dox)-inducible GFP (left part), KRASWT (middle part), and KRASG12D (right part). (B) GSE53659: KRASG12D-driven PDAC cells from KC (Pdx1-Cre/KrasG12D/+) mice compared with normal pancreatic cells from WT mice. (C) GSE67358: The metastatic (meta) and non-metastatic (no meta) PDAC cells from KPC (Pdx1-Cre/KrasG12D/+/Trp53R172H/+) mice were compared with the PDAC cells from KPflC (Pdx1-Cre/KrasG12D/+/Trp53-/+) mice (left and middle parts) and with each other (right part). (D) GSE123646: In the left part, PDAC cells from KPC mice irrespective of their metastatic status were compared with those from KPflC mice. In the right part: KPflC PDAC cells transfected with a plasmid encoding human TP53R175H were compared with those transfected with a control vector. (E) GSE33323: Normal, pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN), and PDAC tissues from KC mice were compared. Notes for (A–E): The top portion of an enrichment plot shows the running enrichment score (ES) for the gene set (53 PDAC signature genes) as the analysis walks down the ranked list (as indicated by a green line). The ES is the maximum deviation from zero encountered in walking down the list. A positive or negative ES indicates gene set enrichment at the top or bottom of the ranked list, respectively. The bottom portion shows the ranking metric scores (as indicated by the grey graph) that represent a gene’s correlation with a phenotype (such as a treatment). For categorical phenotypes in (A–D), the metric “Log2_Ratio_of_ Classes” was used to calculate fold changes (Log2 ratio) for gene expression differences between two phenotypes. A positive or negative value indicates the correlation of the gene set with the first or second phenotype, respectively. For continuous phenotypes (Normal → PanIN → PDAC) in (E), the Pearson’s correlation metric was used. A positive value indicates the correlation of the gene set with the phenotype profile and a negative value indicates no correlation or inverse correlation of the gene set with the phenotype profile. The middle portion is a barcode plot showing the position of 53 PDAC signature genes (denoted as “Hits”) in the ranked list. The “zero cross” (a dash line) indicates the point at which the calculated difference between expression in two or continuous phenotypes is 0. Red or blue gradient colors around the “zero cross” correspond to the expression levels of the ranked list. Genes with the darker red or blue are expressed higher in the first or second phenotype, respectively. (F) The heat map for the relative expression of PDAC gene signature in GSE33323 microarray data set.

To investigate the role of TP53 (Trp53 in mice) gene mutation, two microarray data sets, GSE67358 [32] and GSE123646 [33], were employed. It has been shown that one-third of KC mice develop PDAC by 500 days [47], and the additional Trp53 mutation in KPC (Pdx1-Cre/KrasG12D/+/Trp53R172H/+) mice or Trp53 deletion in KPflC (Pdx1-Cre/KrasG12D/+/Trp53-/+) mice accelerates the tumor development by 120–180 days [48]. However, only Trp53 mutation, but not deletion, can drive tumor metastasis in this model [49], suggesting a synergy between KRAS and TP53 mutations to promote PDAC progression. Because the incidence of tumor metastasis is about 65% in KPC mice [49], the gene expression profiles of both metastatic (meta) and non-metastatic (no meta) PDAC cells from KPC mice were compared with that from KPflC mice (Figure 5C, the left and middle parts). In addition, the gene expression profiles of metastatic and non-metastatic PDAC cells were also compared to each other (Figure 5C, the right part). We found that the PDAC gene signature was not enriched in any group, suggesting that the PDAC gene signature was not associated with TP53 (Trp53) mutation and its metastasis-promoting effect. It was puzzling that inconsistent observation was found in the GSE123646 data set (Figure 5D). The PDAC gene signature was enriched in KPC mice-derived PDAC cells (irrespective of their metastatic status) compared with that in KPflC mice-derived PDAC cells. However, the PDAC gene signature was not enriched in KPflC mice-derived PDAC cells transfected with the human equivalent of murine Trp53R172H (TP53R175H). Such discrepancy may imply the minimal effect of TP53 gene mutation on PDAC gene signature expression, which warrants further investigation.

The above results argue for the essential role of KRAS gene mutation in PDAC gene signature expression. To further investigate the expression of PDAC gene signature during KRASG12D-driven pancreatic tumorigenesis, the gene expression profiles of normal pancreas, pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) and PDAC in KC mice were obtained from the microarray data set GSE33323 [29]. GSEA showed that the PDAC gene signature is significantly correlated with PanIN and PDAC (Figure 5E). The related expression of PDAC gene signature was visualized in a heat map showing that the PDAC gene signature was induced during KRASG12D-driven PDAC development in KC mice (Figure 5F). Taken together, we conclude that the PDAC gene signature is driven by KRAS, but not TP53, gene mutation.

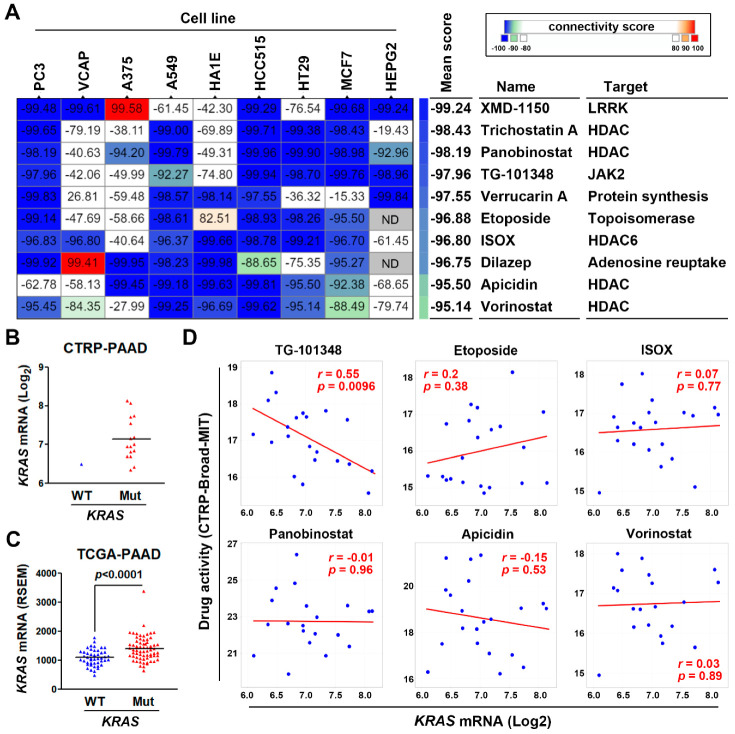

3.4. Connectivity Map Analysis and Drug Sensitivity Profiling Identify TG-101348 (Fedratinib) as a Potential Drug Reversing KRAS-Driven Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Gene Signature

To identify potential drugs that could reverse the KRAS-driven PDAC gene signature, we employed the CMap database that contains numerous gene signatures from cultured human cancer cell lines treated with drugs [38]. If a drug could reverse a disease-associated gene signature, this drug is believed to have the potential to cure the disease [39,40]. We queried the CMap database with the PDAC gene signature (53 upregulated genes) to connect the PDAC gene signature to drug-derived gene signatures. The CMap connectivity score ranging from −100 to 100 corresponds to the magnitude of dissimilarity and similarity between queried and existing gene signatures. Figure 6A showed the most dissimilar drugs (connectivity score < −95) representing the potential drugs that could reverse the queried PDAC gene signature. Interestingly, most of them belong to histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors including trichostatin A (pan-HDAC), panobinostat (pan-HDAC), ISOX (HDAC6-specific), apicidin (pan-HDAC), and vorinostat (pan-HDAC). Therefore, inhibition of HDAC might have the potential to treat PDAC by reversing its KRAS-driven gene signature.

Figure 6.

Connectivity Map analysis and drug sensitivity profiling in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells. (A) The PDAC gene signature (53 upregulated genes) was queried using the CMap database to predict potential drugs to reverse this signature. The connectivity scores ranging from −100 to 100 correspond to the dissimilarity and similarity between the queried and existing gene signatures in each drug-treated cancer cell line. Inset at top right: a color key shows the connectivity scores. The blue and red colors indicate the scores of −100 and 100, respectively. (B) The correlation between KRAS gene mutation and mRNA levels in PDAC cell lines (The Cancer Therapeutics Response Portal CTRP-PAAD (pancreatic adenocarcinoma) data from the CTRP database). (C) The correlation between KRAS gene mutation and mRNA levels in PDAC cancer tissues (The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)-PAAD data from the cBioPortal database). (D) The correlation between drug activity and KRAS mRNA levels in PDAC cell lines (CTRP-PAAD data from the CTRP database).

We hypothesized that a drug may exhibit KRAS-dependent cytotoxicity in cancer cells if this drug could reverse the KRAS-driven gene signature. To examine whether the predicted CMap drugs could exhibit KRAS-dependent cytotoxicity in PDAC cells, we employed the CellMinerCDB database that is a web-based tool enabling to explore and analyze pharmacological and genomic data of human cancer cell lines [41]. Due to the frequent KRAS mutation in PDAC, there was only one PDAC cell line (BxPC-3) harboring the wild-type KRAS gene (Figure 6B). Thus, it is impossible to correlate the drug activity to KRAS gene mutation. According to the gene expression profiles from PDAC cell lines (CTRP-PAAD) and patients’ tissues (TCGA-PAAD; Figure 6C), the mutant KRAS gene tended to be expressed higher compared to the wild-type KRAS gene. Thus, as an alternative, we correlated the drug activity with KRAS mRNA expression. The CTRP database only contained the drug sensitivity profiles for TG-101348, etoposide, ISOX, panobinostat, apicidin, and vorinostat. Surprisingly, pan-HDAC (panobinostat, apicidin, and vorinostat) and HDAC6 (ISOX) inhibitors, as well as etoposide, did not exhibit KRAS-dependent cytotoxicity (Figure 6D). Only TG-101348 displayed significant association with KRAS expression (Figure 6D). Therefore, TG-101348 may exhibit KRAS-dependent anticancer activity in PDAC cells via the reversion of KRAS-driven gene signature.

4. Discussion

Dynamic cell–cell and cell–ECM interactions maintain a tumor microenvironment that consists of acellular fibrous stroma and diverse populations of the non-neoplastic cancer-associated cells. Previous studies suggested that the tumor progression of PDAC as well as its deadly malignancy are highly associated with the tumor microenvironment. Thus, targeting the stromal compartment in PDAC may have anticancer effects and enhance chemo-/radio-sensitivity [50,51,52]. Our results imply that inhibition of PDAC gene signature (genes related to cell–cell and cell–ECM interactions) may be beneficial for treating PDAC via a remodeling of the tumor microenvironment.

According to TCGA-PAAD data, there were several KRAS mutation types in PDAC patients (Supplementary Material, Figure S1A), including KRASG12C (glycine 12 to cysteine; n = 1), KRASG12D (n = 45), KRASG12V (glycine 12 to valine; n = 31), KRASG12S (glycine 12 to serine; n = 1), KRASG12A (glycine 12 to alanine; n = 1), KRASG12R (glycine 12 to arginine; n = 24), KRASG13C (n = 1), KRASQ61R (glutamine 61 to arginine; n = 2), and KRASQ61H (glutamine 61 to histidine; n = 6). The most frequent mutation types were KRASG12D, KRASG12V, and KRASG12R. In this study, only the impact of KRASG12D on PDAC gene signature was analysed by GSEA. The roles of other KRAS gene mutations were still unclear. However, we found that the expression levels of PDAC gene signature were similar in patients with different KRAS mutation types (Supplementary Material, Figure S1B and Table S1). Furthermore, GSEA indicated that the PDAC gene signature was significantly enriched in patients with KRASG12D, KRASG12V, and KRASG12R (Supplementary Material, Figure S1C). Therefore, the PDAC gene signature could be driven by different KRAS mutation types.

TG-101348, also known as fedratinib, is a JAK2-selective inhibitor that has been approved for treating patients with myelofibrosis [53]. Myelofibrosis is a rare type of bone marrow cancer, which disrupts the normal production of blood cells. The discovery of JAK2V617F (valine 617 to phenylalanine) mutation in myelofibrosis uncovers the activated JAK–STAT (signal transducer and activator of transcription) signaling as a primary driver for myelofibrosis, and supports the rationale for treating myelofibrosis by JAK2 inhibition [54]. Interestingly, a previous study has shown that STAT3 plays a critical role in KRAS-induced PDAC tumorigenesis. A large-scale cancer cell line screening identified a JAK2-selective inhibitor, AZ960, that blocks STAT3 activation and exhibits higher sensitivity against PDAC cell lines [55], which supports the utility of therapeutic targeting of JAK2–STAT3 signaling in PDAC.

HDAC inhibitors have been viewed as a prominent class of therapeutic agents for treating PDAC [56,57]. However, the impact of KRAS mutation on their anticancer activity was largely unclear. Our results suggest that the anticancer activity of HDAC inhibitors is unrelated to KRAS mutation status. Consistently, previous studies found that pan-HDAC inhibitors (vorinostat and AR-42) exhibit similar cytotoxicity in both KRAS WT and mutant PDAC cells [58,59]. However, it was also reported that a HDAC inhibitor, romidepsin, preferentially induces apoptosis in cancer cells harboring mutant KRAS [60]. More investigations are needed to clarify the exact role of KRAS mutation in the anticancer activity of HDAC inhibitors.

5. Conclusions

This study integrates bioinformatics resources to investigate the key driver mutation gene, KRAS, and the associated gene signature in PDAC. Our results demonstrate that the progression and prognosis of PDAC is highly associated with a KRAS-driven gene signature related to cell–cell and cell–ECM interactions. A FDA-approved JAK2-selective inhibitor, fedratinib (TG-101348), is predicted to reverse the KRAS-driven gene signature, thereby providing therapeutic benefit for KRAS-mutated PDAC patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the “TMU Research Center of Cancer Translational Medicine” from The Featured Areas Research Center Program within the framework of the Higher Education Sprout Project by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4426/10/3/130/s1, Table S1: The correlation between KRAS mutation types and PDAC gene signature, Figure S1: Role of KRAS mutation types in PDAC gene signature expression, Figure S1A: Visualization of the KRAS mutation burden and hotspots in 168 PDAC patients, Figure S1B: A heat map shows the correlation between KRAS mutation types and PDAC gene signature expression, Figure S1C: GSEA results for the role of KRAS mutation types in regulating PDAC gene signature, File S1: The differentially expressed genes (DEGs) prepared from microarray data sets.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.-W.L. and P.-M.Y.; methodology, L.-W.L. and Y.-Y.H.; validation, L.-W.L. and Y.-Y.H.; formal analysis, L.-W.L. and Y.-Y.H.; investigation, L.-W.L. and Y.-Y.H.; resources, Y.-Y.H. and P.-M.Y.; data curation, P.-M.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, L.-W.L., Y.-Y.H., and P.-M.Y.; writing—review and editing, Y.-Y.H. and P.-M.Y.; visualization, L.-W.L. and P.-M.Y.; supervision, P.-M.Y.; project administration, P.-M.Y.; funding acquisition, Y.-Y.H. and P.-M.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology, grant numbers MOST108-2314-B-038-010 and MOST109-2314-B-038-040; the health and welfare surcharge of tobacco products (WanFang Hospital, Chi-Mei Medical Center, and Hualien Tzu-Chi Hospital Joint Cancer Center Grant-Focus on Colon Cancer Research), grant number MOHW109-TDU-B-212-134020.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ryan D.P., Hong T.S., Bardeesy N. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:1039–1049. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1404198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020;70:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamisawa T., Wood L.D., Itoi T., Takaori K. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet. 2016;388:73–85. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manji G.A., Olive K.P., Saenger Y.M., Oberstein P. Current and Emerging Therapies in Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017;23:1670–1678. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Binenbaum Y., Na’ara S., Gil Z. Gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Drug Resist. Updates. 2015;23:55–68. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Storz P., Crawford H.C. Carcinogenesis of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:2072–2081. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raphael B.J., Hruban R.H., Aguirre A.J., Moffitt R.A., Yeh J.J., Stewart C., Robertson A.G., Cherniack A.D., Gupta M., Getz G., et al. Integrated Genomic Characterization of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2017;32:185–203.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore A.R., Rosenberg S.C., McCormick F., Malek S. RAS-targeted therapies: Is the undruggable drugged? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020;19:533–552. doi: 10.1038/s41573-020-0068-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canon J., Rex K., Saiki A.Y., Mohr C., Cooke K., Bagal D., Gaida K., Holt T., Knutson C.G., Koppada N., et al. The clinical KRAS(G12C) inhibitor AMG 510 drives anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2019;575:217–223. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1694-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hallin J., Engstrom L.D., Hargis L., Calinisan A., Aranda R., Briere D.M., Sudhakar N., Bowcut V., Baer B.R., Ballard J.A., et al. The KRASG12C Inhibitor MRTX849 Provides Insight toward Therapeutic Susceptibility of KRAS-Mutant Cancers in Mouse Models and Patients. Cancer Discov. 2020;10:54–71. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amgen Amgen Announces New Clinical Data Evaluating Novel Investigational KRAS(G12C) Inhibitor in Larger Patient Group at WCLC 2019. [(accessed on 16 June 2020)]; Available online: https://www.amgen.com/media/news-releases/2019/09/amgen-announces-new-clinical-data-evaluating-novel-investigational-krasg12c-inhibitor-in-larger-patient-group-at-wclc-2019/

- 12.Badea L., Herlea V., Dima S.O., Dumitrascu T., Popescu I. Combined gene expression analysis of whole-tissue and microdissected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma identifies genes specifically overexpressed in tumor epithelia. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:2016–2027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Idichi T., Seki N., Kurahara H., Yonemori K., Osako Y., Arai T., Okato A., Kita Y., Arigami T., Mataki Y., et al. Regulation of actin-binding protein ANLN by antitumor miR-217 inhibits cancer cell aggressiveness in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8:53180–53193. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellsworth K.A., Eckloff B.W., Li L., Moon I., Fridley B.L., Jenkins G.D., Carlson E., Brisbin A., Abo R., Bamlet W., et al. Contribution of FKBP5 genetic variation to gemcitabine treatment and survival in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e70216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li L., Zhang J.-W., Jenkins G., Xie F., Carlson E.E., Fridley B.L., Bamlet W.R., Petersen G.M., McWilliams R.R., Wang L. Genetic variations associated with gemcitabine treatment outcome in pancreatic cancer. Pharm. Genom. 2016;26:527–537. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0000000000000241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pei H., Li L., Fridley B.L., Jenkins G.D., Kalari K.R., Lingle W., Petersen G., Lou Z., Wang L. FKBP51 affects cancer cell response to chemotherapy by negatively regulating Akt. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donahue T.R., Tran L.M., Hill R., Li Y., Kovochich A., Calvopina J.H., Patel S.G., Wu N., Hindoyan A., Farrell J.J., et al. Integrative survival-based molecular profiling of human pancreatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012;18:1352–1363. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toste P.A., Li L., Kadera B.E., Nguyen A.H., Tran L.M., Wu N., Madnick D.L., Patel S.G., Dawson D.W., Donahue T.R. p85alpha is a microRNA target and affects chemosensitivity in pancreatic cancer. J. Surg. Res. 2015;196:285–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2015.02.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang S., He P., Wang J., Schetter A., Tang W., Funamizu N., Yanaga K., Uwagawa T., Satoskar A.R., Gaedcke J., et al. A Novel MIF Signaling Pathway Drives the Malignant Character of Pancreatic Cancer by Targeting NR3C2. Cancer Res. 2016;76:3838–3850. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klett H., Fuellgraf H., Levit-Zerdoun E., Hussung S., Kowar S., Kusters S., Bronsert P., Werner M., Wittel U., Fritsch R., et al. Identification and Validation of a Diagnostic and Prognostic Multi-Gene Biomarker Panel for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Front. Genet. 2018;9:108. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barrett T., Wilhite S.E., Ledoux P., Evangelista C., Kim I.F., Tomashevsky M., Marshall K.A., Phillippy K.H., Sherman P.M., Holko M., et al. NCBI GEO: Archive for functional genomics data sets–update. Nucleic. Acids Res. 2013;41:D991–D995. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heberle H., Meirelles G.V., da Silva F.R., Telles G.P., Minghim R. InteractiVenn: A web-based tool for the analysis of sets through Venn diagrams. BMC Bioinform. 2015;16:169. doi: 10.1186/s12859-015-0611-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liao Y., Wang J., Jaehnig E.J., Shi Z., Zhang B. WebGestalt 2019: Gene set analysis toolkit with revamped UIs and APIs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W199–W205. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Szklarczyk D., Gable A.L., Lyon D., Junge A., Wyder S., Huerta-Cepas J., Simonovic M., Doncheva N.T., Morris J.H., Bork P., et al. STRING v11: Protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D607–D613. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ashburner M., Ball C.A., Blake J.A., Botstein D., Butler H., Cherry J.M., Davis A.P., Dolinski K., Dwight S.S., Eppig J.T., et al. Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The Gene Ontology Consortium The Gene Ontology Resource: 20 years and still GOing strong. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D330–D338. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanehisa M., Goto S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liberzon A., Birger C., Thorvaldsdottir H., Ghandi M., Mesirov J.P., Tamayo P. The Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst. 2015;1:417–425. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ling J., Kang Y.a., Zhao R., Xia Q., Lee D.-F., Chang Z., Li J., Peng B., Fleming J.B., Wang H., et al. KrasG12D-induced IKK2/beta/NF-kappaB activation by IL-1alpha and p62 feedforward loops is required for development of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:105–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsang Y.H., Dogruluk T., Tedeschi P.M., Wardwell-Ozgo J., Lu H., Espitia M., Nair N., Minelli R., Chong Z., Chen F., et al. Functional annotation of rare gene aberration drivers of pancreatic cancer. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10500. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stellas D., Szabolcs M., Koul S., Li Z., Polyzos A., Anagnostopoulos C., Cournia Z., Tamvakopoulos C., Klinakis A., Efstratiadis A. Therapeutic effects of an anti-Myc drug on mouse pancreatic cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014;106 doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller B.W., Morton J.P., Pinese M., Saturno G., Jamieson N.B., McGhee E., Timpson P., Leach J., McGarry L., Shanks E., et al. Targeting the LOX/hypoxia axis reverses many of the features that make pancreatic cancer deadly: Inhibition of LOX abrogates metastasis and enhances drug efficacy. EMBO Mol. Med. 2015;7:1063–1076. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201404827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vennin C., Melenec P., Rouet R., Nobis M., Cazet A.S., Murphy K.J., Herrmann D., Reed D.A., Lucas M.C., Warren S.C., et al. CAF hierarchy driven by pancreatic cancer cell p53-status creates a pro-metastatic and chemoresistant environment via perlecan. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:3637. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10968-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mootha V.K., Lindgren C.M., Eriksson K.F., Subramanian A., Sihag S., Lehar J., Puigserver P., Carlsson E., Ridderstrale M., Laurila E., et al. PGC-1alpha-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat. Genet. 2003;34:267–273. doi: 10.1038/ng1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Subramanian A., Tamayo P., Mootha V.K., Mukherjee S., Ebert B.L., Gillette M.A., Paulovich A., Pomeroy S.L., Golub T.R., Lander E.S., et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cerami E., Gao J., Dogrusoz U., Gross B.E., Sumer S.O., Aksoy B.A., Jacobsen A., Byrne C.J., Heuer M.L., Larsson E., et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: An open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:401–404. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gao J., Aksoy B.A., Dogrusoz U., Dresdner G., Gross B., Sumer S.O., Sun Y., Jacobsen A., Sinha R., Larsson E., et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci. Signal. 2013;6:pl1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Subramanian A., Narayan R., Corsello S.M., Peck D.D., Natoli T.E., Lu X., Gould J., Davis J.F., Tubelli A.A., Asiedu J.K., et al. A Next Generation Connectivity Map: L1000 Platform and the First 1,000,000 Profiles. Cell. 2017;171:1437–1452.e1417. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lamb J. The Connectivity Map: A new tool for biomedical research. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2007;7:54–60. doi: 10.1038/nrc2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lamb J., Crawford E.D., Peck D., Modell J.W., Blat I.C., Wrobel M.J., Lerner J., Brunet J.-P., Subramanian A., Ross K.N., et al. The Connectivity Map: Using gene-expression signatures to connect small molecules, genes, and disease. Science. 2006;313:1929–1935. doi: 10.1126/science.1132939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rajapakse V.N., Luna A., Yamade M., Loman L., Varma S., Sunshine M., Iorio F., Sousa F.G., Elloumi F., Aladjem M.I., et al. CellMinerCDB for Integrative Cross-Database Genomics and Pharmacogenomics Analyses of Cancer Cell Lines. iScience. 2018;10:247–264. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2018.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Basu A., Bodycombe N.E., Cheah J.H., Price E.V., Liu K., Schaefer G.I., Ebright R.Y., Stewart M.L., Ito D., Wang S., et al. An interactive resource to identify cancer genetic and lineage dependencies targeted by small molecules. Cell. 2013;154:1151–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rees M.G., Seashore-Ludlow B., Cheah J.H., Adams D.J., Price E.V., Gill S., Javaid S., Coletti M.E., Jones V.L., Bodycombe N.E., et al. Correlating chemical sensitivity and basal gene expression reveals mechanism of action. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016;12:109–116. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seashore-Ludlow B., Rees M.G., Cheah J.H., Cokol M., Price E.V., Coletti M.E., Jones V., Bodycombe N.E., Soule C.K., Gould J., et al. Harnessing Connectivity in a Large-Scale Small-Molecule Sensitivity Dataset. Cancer Discov. 2015;5:1210–1223. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Furukawa T., Duguid W.P., Rosenberg L., Viallet J., Galloway D.A., Tsao M.S. Long-term culture and immortalization of epithelial cells from normal adult human pancreatic ducts transfected by the E6E7 gene of human papilloma virus 16. Am. J. Pathol. 1996;148:1763–1770. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ouyang H., Mou L., Luk C., Liu N., Karaskova J., Squire J., Tsao M.S. Immortal human pancreatic duct epithelial cell lines with near normal genotype and phenotype. Am. J. Pathol. 2000;157:1623–1631. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64800-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hingorani S.R., Petricoin E.F., Maitra A., Rajapakse V., King C., Jacobetz M.A., Ross S., Conrads T.P., Veenstra T.D., Hitt B.A., et al. Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:437–450. doi: 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00309-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hingorani S.R., Wang L., Multani A.S., Combs C., Deramaudt T.B., Hruban R.H., Rustgi A.K., Chang S., Tuveson D.A. Trp53R172H and KrasG12D cooperate to promote chromosomal instability and widely metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:469–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morton J.P., Timpson P., Karim S.A., Ridgway R.A., Athineos D., Doyle B., Jamieson N.B., Oien K.A., Lowy A.M., Brunton V.G., et al. Mutant p53 drives metastasis and overcomes growth arrest/senescence in pancreatic cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:246–251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908428107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ho W.J., Jaffee E.M., Zheng L. The tumour microenvironment in pancreatic cancer clinical challenges and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020;17:527–540. doi: 10.1038/s41571-020-0363-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hosein A.N., Brekken R.A., Maitra A. Pancreatic cancer stroma: An update on therapeutic targeting strategies. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020;17:487–505. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-0300-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stopa K.B., Kusiak A.A., Szopa M.D., Ferdek P.E., Jakubowska M.A. Pancreatic Cancer and Its Microenvironment-Recent Advances and Current Controversies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:3218. doi: 10.3390/ijms21093218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Blair H.A. Fedratinib: First Approval. Drugs. 2019;79:1719–1725. doi: 10.1007/s40265-019-01205-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mullally A., Hood J., Harrison C., Mesa R. Fedratinib in myelofibrosis. Blood Adv. 2020;4:1792–1800. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Corcoran R.B., Contino G., Deshpande V., Tzatsos A., Conrad C., Benes C.H., Levy D.E., Settleman J., Engelman J.A., Bardeesy N. STAT3 plays a critical role in KRAS-induced pancreatic tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5020–5029. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Feng W., Zhang B., Cai D., Zou X. Therapeutic potential of histone deacetylase inhibitors in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Lett. 2014;347:183–190. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Damaskos C., Garmpis N., Karatzas T., Nikolidakis L., Kostakis I.D., Garmpi A., Karamaroudis S., Boutsikos G., Damaskou Z., Kostakis A., et al. Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) Inhibitors: Current Evidence for Therapeutic Activities in Pancreatic Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:3129–3135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chao M.W., Chang L.H., Tu H.J., Chang C.D., Lai M.J., Chen Y.Y., Liou J.P., Teng C.M., Pan S.L. Combination treatment strategy for pancreatic cancer involving the novel HDAC inhibitor MPT0E028 with a MEK inhibitor beyond K-Ras status. Clin. Epigenetics. 2019;11:85. doi: 10.1186/s13148-019-0681-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Henderson S.E., Ding L.Y., Mo X., Bekaii-Saab T., Kulp S.K., Chen C.S., Huang P.H. Suppression of Tumor Growth and Muscle Wasting in a Transgenic Mouse Model of Pancreatic Cancer by the Novel Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor AR-42. Neoplasia. 2016;18:765–774. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2016.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bahr J.C., Robey R.W., Luchenko V., Basseville A., Chakraborty A.R., Kozlowski H., Pauly G.T., Patel P., Schneider J.P., Gottesman M.M., et al. Blocking downstream signaling pathways in the context of HDAC inhibition promotes apoptosis preferentially in cells harboring mutant Ras. Oncotarget. 2016;7:69804–69815. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.