Abstract

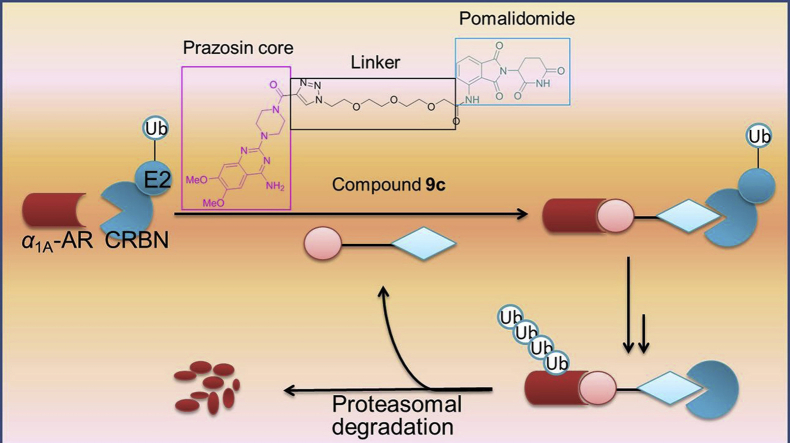

Proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) are dual-functional hybrid molecules that can selectively recruit an E3 ubiquitin ligase to a target protein to direct the protein into the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), thereby selectively reducing the target protein level by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Nowadays, small-molecule PROTACs are gaining popularity as tools to degrade pathogenic protein. Herein, we present the first small-molecule PROTACs that can induce the α1A-adrenergic receptor (α1A-AR) degradation, which is also the first small-molecule PROTACs for G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) to our knowledge. These degradation inducers were developed through conjugation of known α1-adrenergic receptors (α1-ARs) inhibitor prazosin and cereblon (CRBN) ligand pomalidomide through the different linkers. The representative compound 9c is proved to inhibit the proliferation of PC-3 cells and result in tumor growth regression, which highlighted the potential of our study as a new therapeutic strategy for prostate cancer.

Key words: Small-molecule PROTACs, α1A-Adrenergic receptor, Ubiquitylation, Degradation, Prostate cancer

Abbreviations: α1-ARs, α1-adrenergic receptors; α1A-AR, α1A-adrenergic receptor; α1B-AR, α1B-adrenergic receptor; α1D-AR, α1D-adrenergic receptor; BPH, benign prostatic hyperplasia; CRBN, cereblon; DCM, dichloromethane; DMF, dimethylformamide; DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; GPCR, G-protein-coupled receptor; hPCE, human prostate cancer epithelial; HPLC, high-performance liquid chromatography; LUTS, lower urinary tract symptoms; PROTACs, proteolysis targeting chimeras; TEA, triethylamine; THF, tetrahydrofuran

Graphical abstract

Small-molecule proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) of α1A-adrenergic receptor (α1A-AR) were designed and synthesized through conjugation of known α1-ARs inhibitor prazosin and CRBN ligand pomalidomide through different linkers. Selected compounds displayed remarkable degradation activity. Inhibition of PC-3 cells proliferation and tumor growth regression of these compounds were investigated.

1. Introduction

α1-Adrenergic receptors (α1-ARs), as important members of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), mediate many physiological responses of the sympathetic nervous system. Up to now, there are three subtypes of α1-ARs (α1A, α1B, and α1D)1,2. α1-ARs mediate actions of the endogenous epinephrine, norepinephrine, and catecholamines, leading to hepatic glucose metabolism, myocardial inotropy and chronotropy, and smooth muscle contraction3. As the prime mediators of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), they also play a crucial role in regulating prostatic smooth muscle tone. Therefore, they are the therapeutic targets for the treatment of hypertension4, BPH5, and LUTS5. All three subtypes of α1-AR are present in the prostate. Previous quantification of α1-AR mRNA expression within human prostatic tissue had indicated that α1A-AR subtype predominates, followed by α1D-AR subtype, while the α1B-AR subtype is rarely expressed. In the hyperplastic prostate, this predominance of α1A-AR is reportedly more marked. The relative level of α1A:α1B:α1D was 63:6:31 in non-BPH tissue but 85:1:14 in BPH tissue6. Furthermore, the total level of α1-ARs in BPH tissue was over 6 times than in normal tissue; particularly, the expression of α1A-AR subtype was almost 9-fold higher6. This elevated expression of α1-ARs, especially α1A-AR subtype, probably directly related to the pathogenicity of prostate patients7.

Currently, prostate cancer is an epithelial malignant tumor, which occurs in the prostate and is a common malignant tumor of the male genitourinary system8. The incidence of prostate cancer is rising rapidly in most countries, which is expected to increase substantially in the next future. The cause of prostate cancer mortality is metastasis to the bone and lymph nodes as well as progression from androgen-dependent to androgen-independent prostatic growth9. In addition, it is noteworthy that the castrate-resistant prostate cancer is currently considered incurable and inevitable10. Therefore, it is imperative to develop new drugs to improve the curative effect for these patients. Importantly, some studies have suggested that there is a direct link between α1A-AR and the proliferation of prostate cancer cells11, 12, 13. By using two human prostate cancer epithelial (hPCE) cell models, it has been identified that α1A-AR could functionally couple to transmembrane Ca2+ entry via the phospholipase C (PLC)-catalyzed inositol phospholipid-breakdown signaling pathway, which works presumably by activating the channels in the transient receptor potential (TRP) family. This Ca2+ entry appears to be a major source of Ca2+ required to promote hPCE cells proliferation. Therefore, chronic activation of α1A-AR promoted hPCE cells proliferation. Collectively, α1A-AR plays an important role in enhancing hPCE cells proliferation via TRP channels. Therefore, we can expect more reasonable therapeutic effects if α1A-AR is selectively degraded, which is a novel hypothesis for the therapy of prostate cancer.

Proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) technology is an emerging drug discovery paradigm. PROTACs offer a novel mechanism to inhibit protein function by inducing target protein degradation, which overcomes the limitations of the current inhibitor pharmacological paradigm, namely, the intracellular destruction of target proteins14. PROTACs contain two ligands that are connected via a linker. One ligand would bind with the target protein, while the other ligand would recruit E3 ubiquitin ligase. The formation of a ternary complex between PROTAC, E3 ligase, and target protein can lead to the polyubiquitination and subsequent degradation of the target protein15,16. Small-molecule PROTACs possess many advantages, such as good tissue distribution and oral bioavailability, high selectivity, sub-stoichiometric catalytic activity and rarely off-target side effects17. Therefore, protein degradation by small-molecule PROTACs would provide a new modality to target a number of proteins for degradation, which could be applied for novel drug development.

Up to now, small-molecule PROTACs have made remarkable advances and have been used for inducing the degradation of many pathogenic proteins, including AR18, BCR-ABL19, BRD420,21, CRABP I/II22, ERα23, ERRα24, RAR25, RIPK224, TACC326, etc. Considering α1A-AR is overexpressed in prostate cancer cells and could promote cell proliferation, and the unique features of small-molecule PROTACs, we designed and synthesized the first small-molecule PROTACs to induce the degradation of α1A-AR so far.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Design strategy

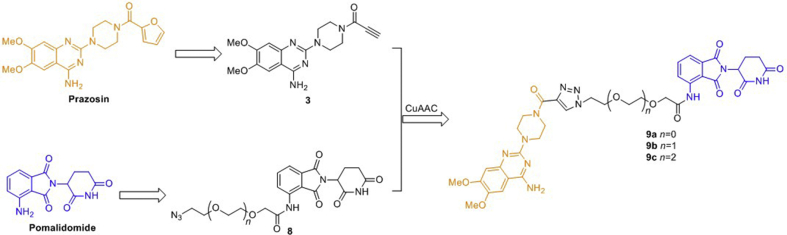

As reported previously27,28, 4-amino-6,7-dimethoxy-2-(piperazin-l-yl)-quinazoline core of prazosin derivatives always endure antagonism to α1-ARs, which was chosen as the α1A-AR binding moiety as a result (Scheme 1). In addition, in the previous work of our group, the results we have obtained indicate that acylation of 4-amino-6,7-dimethoxy-2-(piperazin-l-yl)-quinazoline will help to increase the affinity of the antagonists to some extent. Therefore, we used the amide group as a convenient bridge to connect the key pharmacophore of prazosin with the linker section. It has been reported that cereblon (CRBN) E3 ligase based PROTACs are in a more suitable chemical space with respect to oral absorption and have better drug-like physicochemical properties due to the distinct starting properties of the E3 ligase warhead, so we chose CRBN as the target of E3 ligase29. For the binding moiety of CRBN E3 ligase, it was discovered that thalidomide and its derivatives (pomalidomide and lenalidomide) directly bind to and inhibit E3 ubiquitin ligase CRBN. Considering pomalidomide (Scheme 1) has the most potent affinity among the three ligands, therefore, it was used to recruit CRBN E3 ligase in this study30,31. Therefore, based on the above results, we designed three small-molecule PROTACs (9a–c) by conjugating the key pharmacophore of prazosin as α1A-AR ligand with pomalidomide as CRBN ligand via polyethylene glycol (PEG) linkers with varying length (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Structure and synthetic design of small-molecule PROTACs for α1A-AR.

2.2. Chemistry

The synthetic details of designed compounds can be found in Scheme 2. For the binding moiety of α1A-AR, we pruned away the furan group of prazosin to introduce the terminal alkyne and provide the key intermediate acetylenic compound 3. After the nucleophilic substitution reaction of 2-chloro-6,7-dimethoxyquinazolin-4-amine with piperazine, and amidation by propiolic acid, acetylenic compound 3 was afforded. The primary PEG linkers 4a–c with different length were modified by the nucleophilic substitution reaction with NaN3 and sodium iodoacetate at the terminal halogen group and hydroxyl, respectively. Obtained linkers 6a–c possess an azido group and a carboxyl group. For the binding moiety of E3 ligase CRBN, amide condensation reaction of linkers 6a–c and pomalidomide gave the key intermediate azides 8a–c. The end products 9a–c were obtained by the CuAAC click reactions between the above acetylenic compound 3 and the azides 8a–c.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of PROTACs 9a–c and negative control 11. Reagents and conditions: (i) piperazine, H2O, 100 °C, 6 h; (ii) propiolic acid, EDCI, HOBt, TEA, DCM, rt, 20 min; (iii) H2O/CH3CN, NaN3, 80 °C, 20 h; (iv) NaH, THF, 0 °C, 30 min, and then sodium iodoacetate, rt, 32 h; (v) SOCl2, TEA, THF; (vi) t-BuOH/H2O, CuSO4, sodium ascorbate, 50 °C, 2 h; (vii) DMF, K2CO3, CH3I, rt, 6 h; (viii) t-BuOH/H2O, CuSO4, sodium ascorbate, 50 °C, 2 h.

2.3. Ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation of α1A-AR

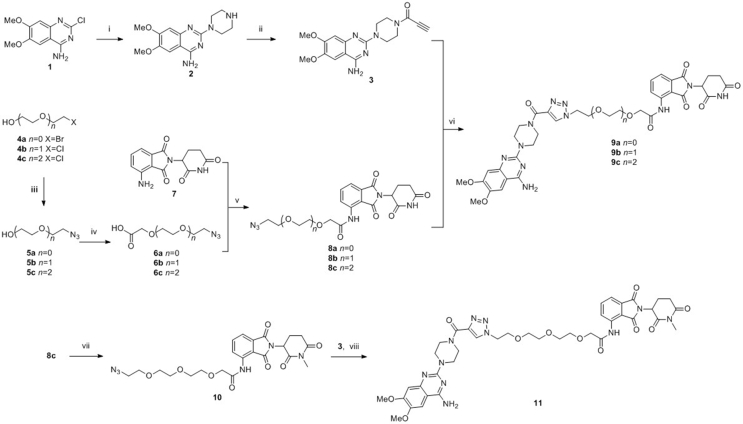

First of all, the cytotoxicity of α1A-AR PROTACs in HEK293 cells was detected, and CCK-8 assay revealed that the cytotoxicity of all compounds was relatively weak with IC50 > 50 μmol/L and the subsequent experiment will not be interfered by cytotoxicity (Supporting Information Fig. S1). To study the effect of the synthesized PROTACs on α1-ARs, HEK293 cells stably transfected with α1A-, α1B- or α1D-AR were treated with compounds 9a–c. We first examined the level of α1A-AR in HEK293 cells expressing α1A-AR by Western blot analysis. As shown in Fig. 1, compounds 9a and 9c induced a dose-dependent and time-dependent decrease of α1A-AR, while 9b did not show too much effect within the tested concentrations.

Figure 1.

(A) PROTACs dose-dependently downregulates α1A-AR levels. α1A-AR stably transfected HEK293 cells were incubated with PROTACs at indicated concentrations for 12 h. (B) Cells were incubated with 3 μmol/L PROTACs for the indicated time. (C) Quantitative analysis of the Western blot in Fig. 1A. (D) Quantitative analysis of the Western blot in Fig. 1B.

Compound 9c resulted in α1A-AR degradation in the treated HEK293 cells with a DC50 value (the concentration of an inducer that required for 50% protein degradation) approximately 2.86 μmol/L. The DC50 value of compound 9a was about 4.32 μmol/L. For the cells treated with 10 μmol/L compound 9c for 12 h, the maximal level of degradation (Dmax) reached 94%. These results suggested that the linker with n = 3 gave the best results among those investigated. One possible interpretation would be that the structure of compound 9c is most suitable to bring the ubiquitination sites in α1A-AR and CRBN into an appropriate spatial relationship to allow effective ubiquitination.

We further investigated the effect of compound 9c on the level of α1B-AR and α1D-AR in the corresponding stably transfected HEK293 cells. Based on Western blot, compound 9c showed no degradation activity for α1B-AR, and only showed a slight influence on the α1D-AR level (Supporting Information Fig. S2). The preferential degradation of α1A-AR presumably resulted from preferential direct interaction or reduced steric hindrance between α1A-AR and CRBN, which led to a more efficient formation of the ternary complex between α1A-AR, compound 9c and CRBN compared with α1B-AR and α1D-AR. These results suggested that compound 9c is a valuable tool that could selectively induce the degradation of α1A-AR.

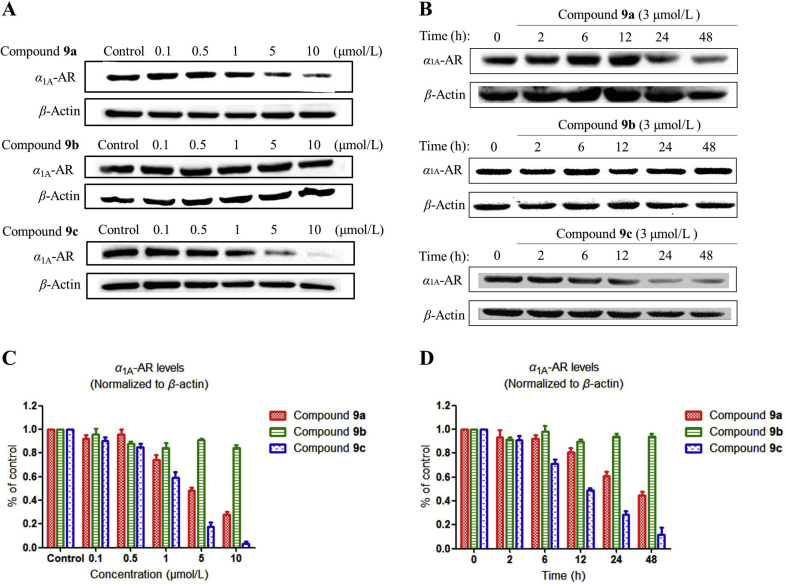

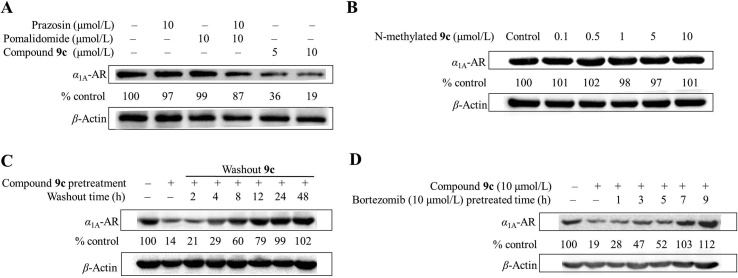

We next confirmed that the decreased α1A-AR expression level was not caused by a partial structure of compound 9c or by a mere mixture of prazosin and pomalidomide (Fig. 2A), indicating that the conjugation of prazosin and pomalidomide to a single molecule is essential for inducing the α1A-AR degradation. To study whether the degradation of α1A-AR is mediated by CRBN, we designed and synthesized compound 11 as a negative control (Scheme 2). In the reported X-ray diffraction structure of the DDB1-CRBN E3 ubiquitin ligase with bound pomalidomide (PDB: 4CI3)30, the NH group in the glutarimide ring is very important for the hydrogen bonding between the carbonyl group and H380. Methylation of this NH group in compound 9c would significantly hinder the binding of pomalidomide to His380 and led to no effective recruitment of CRBN (Supporting Information Fig. S3)20. HEK293 cells treated with N-methylated 9c (compound 11) for 12 h were tested for α1A-AR degradation. As expected, N-methylated 9c was incapable of inducing α1A-AR degradation (Fig. 2B). We also found that the downregulation of α1A-AR level by PROTAC 9c is reversible. The α1A-AR level could recover to basal level within approximately 24 h if the cells were washed thoroughly to remove residual PROTAC 9c (Fig. 2C), which illustrated that cells would need to resynthesize α1A-AR to recover its functions. This could potentially delay the development of drug resistance. In addition, we also investigated the influence of proteasome inhibitor bortezomib on α1A-AR degradation induced by PROTAC 9c. After the pretreatment of cells using bortezomib for more than 7 h, compound 9c could no longer trigger the degradation of α1A-AR (Fig. 2D), suggesting that the PROTAC 9c induced α1A-AR degradation can be attributed to proteasomal degradation.

Figure 2.

(A) Western blot detection of α1A-AR in HEK293 cells expressing α1A-AR after 12 h treatment with each reagent. (B) HEK293 cells treated with N-methylated 9c for 12 h were tested for α1A-AR expression level. (C) Degradation by PROTACs is reversible. After a 12 h pretreatment with 10 μmol/L PROTAC 9c, the medium was replaced with fresh medium lacking PROTAC 9c and the cells washed thoroughly to remove residual compound 9c, and then the cells were analyzed by Western blot after the indicated times. (D) HEK293 cells were preincubated with 10 μmol/L of bortezomib for the indicated times before the treatment with 10 μmol/L PROTAC 9c for 12 h, and then α1A-AR levels were detected.

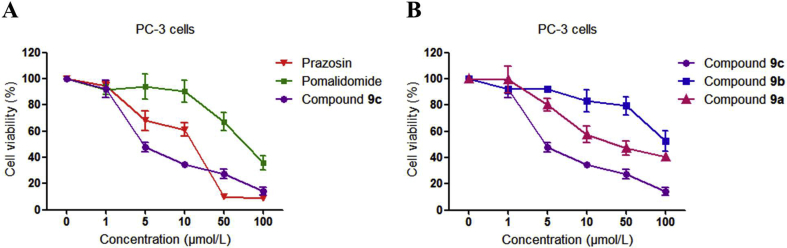

2.4. Inhibition of PC-3 cells proliferation

Since compound 9c was proved to be effective in reducing α1A-AR level, we next determined whether compound 9c could inhibit the proliferation of the androgen-independent PC-3 prostate cancer cells by inducing the α1A-AR degradation. Both compounds 9c and 9a showed concentration-dependent antiproliferation activities on PC-3 cells, while compound 9b exhibited much less influence in inhibiting the cell growth (Fig. 3). This was consistent with the activity-test results that compound 9b has a weaker potency in the α1A-AR degradation.

Figure 3.

Antiproliferative effects of indicated compounds on PC-3 cells. PC-3 cells were incubated with 1–100 μmol/L compounds for 48 h. The cell viability is shown as percentage of cell numbers of treated over untreated cells. The data was processed using GraphPad Prism 5. The results were reported as the means ± SEM of a representative experiment performed in triplicate.

Notably, it has been reported in the last two decades that some α1-AR antagonists, including prazosin, also exerted anticancer activity against human prostate cancer by inducing apoptosis in both smooth muscle cells and prostate tumor epithelial cells, which was proved to be an action that is unrelated to their capacity to antagonize α1-ARs32, 33, 34. There are several potential mechanisms accounting for the anticancer action of α1-AR antagonists, including activation of caspase 8 and caspase 333,35, cell-cycle arrest32,36, disruption of DNA integrity37,38, and disruption of key mediators of angiogenesis34,39,40, which remained to be further investigated. In this study, we employed the prazosin moiety as an anchor to recruit E3 ubiquitin ligase, and inhibit PC-3 cell proliferation by inducing α1A-AR degradation. Compound 9c (IC50 = 6.12 μmol/L) displayed more potent antiproliferative activity than prazosin (IC50 = 11.72 μmol/L) in PC-3 cells (Fig. 3).

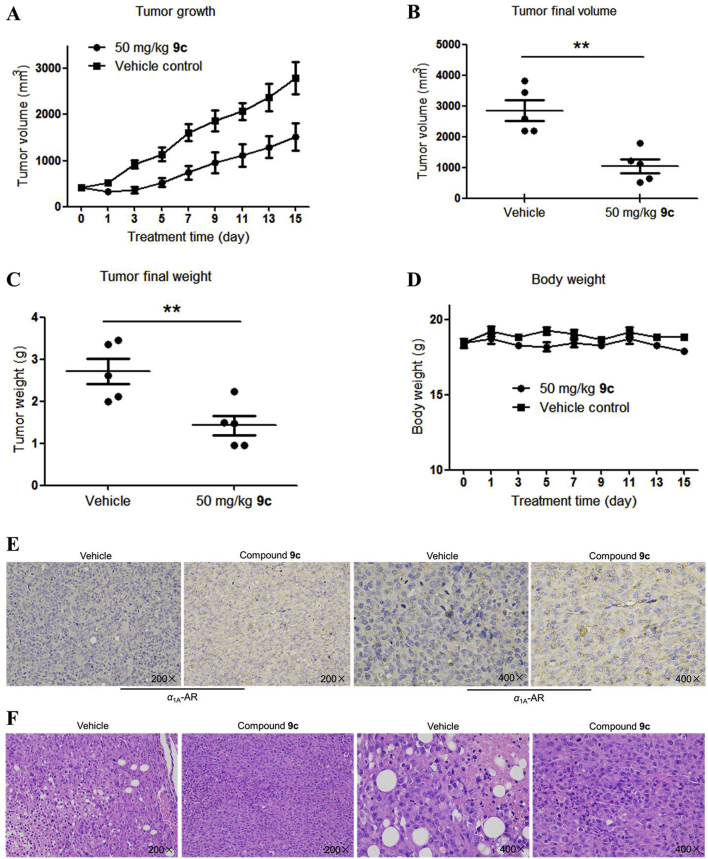

2.5. PROTAC 9c suppresses PC-3 tumor xenografts in vivo

We subsequently conducted an in vivo study to examine the influence of compound 9c on tumor growth. The nude mice with the PC-3 derived prostate cancer xenografts were used as an in vivo tumorigenic model. Daily intraperitoneal administration of compound 9c (50 mg/kg) caused a significant antitumor effect without noticeable loss of body weight (Fig. 4A and B), indicating that compound 9c had negligible toxic effect under the treatment dosages. We observed that compound 9c resulted in an inhibition in tumor growth during this period (Supporting Information Fig. S4). As shown in Fig. 4C and D, the average tumor size and mass was noticeably decreased in mice treated with compound 9c compared with the vehicle-treated group. Tumor samples collected from vehicle- and 9c-treated groups were tested with immunohistochemical and HE staining analysis to identify the decreased α1A-AR level in 9c-treated samples, which further confirmed our findings of α1A-AR suppression by 9c treatment (Fig. 4E and F).

Figure 4.

PROTAC 9c is efficacious in tumor xenograft models of PC-3 cells. (A) Effect of PROTAC 9c on tumor growth in vivo. Tumor growth was monitored over time. (B) Tumors were harvested for analysis of the differences in tumor size. (C) Scatter plot of the tumor mass. (D) Body weights of mice in the antitumor study against PC-3 cells. (E) Immunohistochemical staining of tumor tissue samples from the vehicle group and experimental group. (F) Effects on morphologic changes in tumor tissue samples, HE staining of tumor tissue samples from the vehicle group and experimental group. Data are means ± SEM, n = 5, ∗∗P < 0.01.

3. Conclusions

In this study, we designed and synthesized the first small-molecule PROTACs to induce the degradation of α1A-AR, to the best of our knowledge, which is also the first small-molecule PROTACs available for inducing GPCRs degradation so far. Among all three PROTACs tested, compound 9c, with the longest PEG linker, was capable of inducing the degradation of α1A-AR (DC50 = 2.86 μmol/L). In addition, compound 9c exhibited potent activity in inhibiting the proliferation of PC-3 cells (IC50 = 6.12 μmol/L). The intraperitoneal administration of PROTAC 9c caused a significant suppression of tumor growth, revealing the antitumor efficacy of compound 9c in vivo. Taken together, this proof-of-concept study demonstrates the feasibility of discovering an inducer for α1A-AR degradation, which also provides a novel and efficient strategy for GPCR degradation, as well as the drug discovery for prostate cancer treatment.

4. Experimental

4.1. Chemistry

All reagents are chemical pure or analytical pure, and the water used in chemical experiments is distilled water. Unless otherwise specified, reagents and solvents were used without further purification. The melting points of the compounds were determined using an RY-1G melting point apparatus (uncorrected temperature before use, Tianjin Tianguang New Optical Instrument Technology Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China). Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectra were obtained on a Bruker AV-400 spectrometer (Bruker Inc., Karlsruhe, Germany) with 400 MHz for 1H NMR and 100 MHz for 13C NMR. Mass spectra (ESI mode) and high-resolution mass spectra (HR-MS) were conducted in the Analysis and Test Center of Shandong University, Jinan, China. The purity of all final compounds was determined by RP-HPLC (reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography) analysis. Analytical HPLC (high-performance liquid chromatography) was performed on Agilent Technologies 1260 series high-performance liquid chromatography (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) using a C18 reversed-phase column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm, Phenomenex Inc., Torrance, CA, USA).

4.1.1. 6,7-Dimethoxy-2-(piperazin-1-yl)quinazolin-4-amine (2)

The starting material 2-chloro-6,7-dimethoxyquinazolin-4-amine (0.5 g, 2.09 mmol) and piperazine (2.16 g, 25.04 mmol) were added to 8 mL of water, the suspension was heated to 100 °C for 6 h. After the reaction solution was cooled to room temperature, 10 mL of 1.7 mol/L KOH was added slowly, and then the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h. After filtering the precipitation, it was washed with cold water and recrystallized from methanol, and then the desired product 2 was obtained as white solid. Yield: 492 mg, 81.5%; m.p. 220–223 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.44 (s, 1H, quinazoline H-8), 7.12 (s, 2H, –NH2), 6.72 (s, 1H, quinazoline H-5), 3.83 (s, 3H, –OCH3 at quinazoline C-6), 3.79 (s, 3H, –OCH3 at quinazoline C-7), 3.77–3.70 (m, 4H, –CH2–CH2–NH–CH2–CH2–), 2.91–2.80 (m, 4H, –CH2–CH2–NH–CH2–CH2–). ESI-MS: m/z [M+H]+ Calcd. for C14H20N5O2+ 290.2, Found 290.2.

4.1.2. 1-(4-(4-Amino-6,7-dimethoxyquinazolin-2-yl)piperazin-1-yl)prop-2-yn-1-one (3)

The mixture of intermediate 2 (300 mg, 1.04 mmol), propiolic acid (196.75 μL, 3.11 mmol), EDCI (238.52 mg, 1.24 mmol), HOBt (168.13 mg, 1.24 mmol) and TEA (440.59 μL, 3.11 mmol) in 4 mL of DMF was stirred at room temperature for 20 min. After diluting with 100 mL of dichloromethane, the solution was washed with water and brine and the organic layer was dried over anhydrous MgSO4, MgSO4 was removed by filtration and the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure, the crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography with methanol and dichloromethane (DCM/MeOH = 40:1–20:1), the desired product 3 was produced as a white powder. Yield: 260 mg, 73.4%; m.p. 215–218 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.43 (s, 1H, quinazoline H-8), 7.20 (s, 2H, –NH2), 6.75 (s, 1H, quinazoline H-5), 4.62 (s, 1H, alkynyl-H), 3.90–3.51 (m, 14H, –OCH3, –OCH3 and –CH2–CH2–N–CH2–CH2–). ESI-MS: m/z [M+H]+ Calcd. for C17H20N5O3+ 342.2, Found 342.4.

4.1.3. 2-Azidoethan-1-ol (5a)

Compound 4a (2 g, 16 mmol) was dissolved in a mixed solvent of 32 mL of H2O and 8 mL of CH3CN, and then NaN3 (3.12 g, 48 mmol) was added to the reaction solution carefully, and the solution was heated to 80 °C for 20 h. After the solution was cooled to room temperature, it was extracted with dichloromethane (3 × 50 mL). The organic layer was combined and dried over anhydrous MgSO4, and after removing MgSO4 by filtration, the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure to afford 5a as a clear oil without further purification. Yield: 0.7 g, 50%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.80 (t, 2H, J = 3.0 Hz, HO–CH2–CH2–N3), 3.27 (t, 2H, J = 5.4 Hz, HO–CH2–CH2–N3), 1.96 (s, 1 H, HO–CH2–CH2–N3).

4.1.4. 2-(2-Azidoethoxy)ethan-1-ol (5b)

Compound 5b was synthesized using the method described for 5a except for the use of 4b (2 g, 16 mmol). Yield: 1.73 g, 82.4%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.76 (t, J = 3.8 Hz, 2H, HO–CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–N3), 3.73–3.67 (m, 2H, HO–CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–N3), 3.66–3.54 (m, 2H, HO–CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–N3), 3.51–3.31 (m, 2H, HO–CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–N3), 2.34 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H, HO–CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–N3).

4.1.5. 2-(2-(2-Azidoethoxy)ethoxy)ethan-1-ol (5c)

Compound 5c was synthesized using the method described for 5a except for the use of 4c (2 g, 11.86 mmol). Yield: 1.92 g, 92.3%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.75 (t, J = 4.4 Hz, 2H, HO–CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–N3), 3.71–3.66 (m, 6H, HO–CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–N3), 3.64–3.60 (m, 2H, HO–CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–N3), 3.41 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 2H, HO–CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–N3), 2.52 (s, 1H, HO–CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–N3).

4.1.6. 2-(2-Azidoethoxy)acetic acid (6a)

To a solution of 5a (100 mg, 1.15 mmol) in dry THF (5 mL), NaH (60%, 45.93 mg, 1.15 mmol) was added at 0 °C. After stirring at 0 °C for 30 min, sodium iodoacetate (238.78 mg, 1.15 mmol) was added to the reaction mixture. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 36 h. Water (10 mL) was added to the reaction mixture, THF in the reaction mixture was evaporated, and the residue was taken up in water (30 mL) and washed with dichloromethane (3 × 30 mL). The aqueous layer was acidified (pH = 1) with 1 mol/L HCl, and then saturated with sodium chloride and extracted with dichloromethane (3 × 40 mL). The organic layer was combined and dried over anhydrous MgSO4, MgSO4 was removed by filtration and the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure to afford 6a as a pale-brown liquid without further purification. Yield: 45.8 mg, 27.5%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.25 (s, 1H, –COOH), 4.21 (s, 2H, –CH2–COOH), 3.78–3.74 (m, 2H, –CH2–CH2–N3), 3.50–3.46 (m, 2H, –CH2–CH2–N3).

4.1.7. 2-(2-(2-Azidoethoxy)ethoxy)acetic acid (6b)

Compound 6b was synthesized using the method described for 6a except for the use of 5b (718 mg, 5.48 mmol). Yield: 511.5 mg, 49.2%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.55 (s, 1H, –COOH), 4.21 (s, 2H, –CH2–COOH), 3.78 (t, J = 2.4 Hz, 2H, –CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–N3), 3.75–3.69 (m, 4H, –CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–N3), 3.43 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H, –CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–N3).

4.1.8. 2-(2-(2-(2-Azidoethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)acetic acid (6c)

Compound 6c was synthesized using the method described for 6a except for the use of 5c (800 mg, 4.57 mmol). Yield: 817.2 mg, 76.4%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.38 (s, 1H, –COOH), 4.18 (s, 2H, –CH2–COOH), 3.78–3.75 (m, 2H, –CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–N3), 3.74–3.70 (m, 4H, –CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–N3), 3.70–3.66 (m, 4H, –CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–N3), 3.41 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H, –CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–N3).

4.1.9. 2-(2-Azidoethoxy)-N-(2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-1,3-dioxoisoindolin-4-yl)acetamide (8a)

A mixture of compound 6a (112 mg, 771.79 μmol) and SOCl2 (1.14 mL, 15.37 mmol) in THF (4 mL) was heated to reflux for 3 h. The excessive SOCl2 and solvent were removed by rotary evaporation to afford 2-(2-azidoethoxy)acetyl chloride as a yellow oily liquid (the resultant oily product was used for further synthesis as soon as prepared). The acyl chloride dissolved in THF (2 mL) was dropwise added into the suspension of compound 7 (70 mg, 256.18 μmol) and triethylamine (109.01 μL, 768.53 μmol) in THF (6 mL) at room temperature, and then the mixture was heated to reflux for 5 h. After it was cooled to room temperature, the THF was evaporated, the residue was dissolved in dichloromethane (120 mL), and then the solution was washed with water and brine. After the solution was dried over MgSO4, MgSO4 was removed by filtration and the solvent was evaporated, the crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography with methanol and dichloromethane (DCM/MeOH = 30:1–10:1) to afford white powder as desired product 8a. Yield: 80 mg, 78%; m.p. 183–187 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.16 (s, 1H, –CO–NH–CO–), 10.36 (s, 1H, amide-H), 8.72 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 1,3-dioxoisoindoline H-6), 7.92–7.84 (m, 1H, 1,3-dioxoisoindoline H-7), 7.65 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H, 1,3-dioxoisoindoline H-5), 5.17 (dd, J = 13.0, 5.3 Hz, 1H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-3), 4.26 (s, 2H, –CO–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–N3), 3.87–3.77 (m, 2H, –CO–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–N3), 3.62–3.53 (m, 2H, –CO–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–N3), 2.95–2.85 (m, 1H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-4), 2.66–2.53 (m, 2H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-5), 2.13–2.02 (m, 1H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-4). ESI-MS: m/z [M+Na]+ Calcd. for C17H16N6NaO6+ 423.1, Found 423.4.

4.1.10. 2-(2-(2-Azidoethoxy)ethoxy)-N-(2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-1,3-dioxoisoindolin-4-yl)acetamide (8b)

Compound 8b was synthesized using the method described for 8a except for the use of 6b (312 mg, 1.65 mmol). Yield: 160 mg, 65.6%; m.p. 177–179 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.16 (s, 1H, –CO–NH–CO–), 10.37 (s, 1H, amide-H), 8.73 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 1,3-dioxoisoindoline H-6), 7.87 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H, 1,3-dioxoisoindoline H-7), 7.64 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H, 1,3-dioxoisoindoline H-5), 5.17 (dd, J = 12.8, 5.3 Hz, 1H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-3), 4.22 (s, 2H, –NH–CO–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–), 3.78 (dd, J = 5.4, 2.9 Hz, 2H, –NH–CO–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–), 3.72 (dd, J = 5.5, 2.8 Hz, 2H, –NH–CO–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–), 3.68–3.59 (m, 2H, –CH2–CH2–N3), 3.44–3.36 (m, 2H, –CH2–CH2–N3), 2.90 (m, 1H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-4), 2.69–2.52 (m, 2H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-5), 2.13–2.02 (m, 1H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-4). ESI-MS: m/z [M+Na]+ Calcd. for C19H20N6NaO7+ 467.1, Found 467.3.

4.1.11. 2-(2-(2-(2-Azidoethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)-N-(2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-1,3-dioxoisoindolin-4-yl)acetamide (8c)

Compound 8c was synthesized using the method described for 8a except for the use of 6c (466 mg, 2 mmol). Yield: 137 mg, 42.1%; m.p. 159–165 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.16 (s, 1H, –CO–NH–CO–), 10.37 (s, 1H, amide-H), 8.73 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 1,3-dioxoisoindoline H-6), 7.87 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H, 1,3-dioxoisoindoline H-7), 7.64 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H, 1,3-dioxoisoindoline H-5), 5.17 (dd, J = 12.8, 5.3 Hz, 1H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-3), 4.22 (s, 2H, –NH–CO–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–), 3.78 (dd, J = 5.4, 2.9 Hz, 2H, –NH–CO–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–), 3.72 (dd, J = 5.5, 2.8 Hz, 2H, –NH–CO–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–), 3.68–3.59 (m, 6H, –O–CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–N3), 3.44–3.36 (m, 2H, –CH2–CH2–N3), 2.90 (m, 1H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-4), 2.69–2.52 (m, 2H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-5), 2.13–2.02 (m, 1H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-4). ESI-MS: m/z [M+Na]+ Calcd. for C21H24N6NaO8+ 511.2, Found 511.4.

4.1.12. 2-(2-(4-(4-(4-Amino-6,7-dimethoxyquinazolin-2-yl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)ethoxy)-N-(2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-1,3-dioxoisoindolin-4-yl)acetamide (9a)

Alkyne 3 (35 mg, 102.53 μmol) and azides 8a (41.05 mg, 102.53 μmol) were dissolved in a mixed solvent of 3.9 mL of t-BuOH/H2O (2:1), 0.1 mol/L sodium ascorbate (4.1 mL) and 0.1 mol/L CuSO4 (1.02 mL) were sequentially added to the reaction mixture. After the reaction mixture was heated to 50 °C for 2 h in the dark, the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and the solvent was removed by rotary evaporation. Then 2 mol/L NH4OH (10 mL) was added to the residue and extracted with dichloromethane (3 × 40 mL). The organic layer was combined and dried over MgSO4, and MgSO4 was removed by filtration and the solvent was evaporated; the crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography with methanol and dichloromethane (DCM/MeOH = 30:1–10:1) to afford yellow powder as desired product 9a. Yield: 25 mg, 33%; m.p. 175–177 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.15 (s, 1H, –CO–NH–CO–), 10.28 (s, 1H, amide-H), 8.68 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H, 1,3-dioxoisoindoline H-6), 8.66 (s, 1H, triazole-H), 7.87 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H, 1,3-dioxoisoindoline H-7), 7.64 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H, 1,3-dioxoisoindoline H-5), 7.45 (s, 1H, quinazoline H-8), 7.22 (s, 2H, –NH2), 6.78 (s, 1H, quinazoline H-5), 5.19 (dd, J = 12.7, 5.3 Hz, 1H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-3), 4.77 (s, 2H, –NH–CO–CH2–O–), 4.25–3.68 (m, 18H, triazole–CH2–CH2–O–, –OCH3 at quinazoline C-6, –OCH3 at quinazoline C-7, piperazine-H), 2.97–2.83 (m, 1H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-4), 2.71–2.54 (m, 2H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-5), 2.16–2.05 (m, 1H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-4). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 173.19, 170.17, 169.19, 168.74, 167.14, 161.63, 160.09, 154.78, 145.62, 143.49, 137.02, 136.33, 131.75, 129.76, 125.03, 118.93, 116.78, 104.22, 103.38, 70.13, 69.88, 60.22, 56.32, 55.94, 49.96, 49.51, 31.51, 22.38. ESI-HRMS: m/z [M+H]+ Calcd. for C34H36N11O9+ 742.2692, Found 742.2674. HPLC purity 97.2%, tR = 13.762 min, 250 mm × 4.60 mm, H2O as solvent A and CH3OH containing 0.1% triethylamine as solvent C, the gradient program was as follows: 40%–50% C (0–10 min), and 50% C (10–25 min), 1 mL/min.

4.1.13. 2-(2-(2-(4-(4-(4-Amino-6,7-dimethoxyquinazolin-2-yl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)ethoxy)ethoxy)-N-(2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-1,3-dioxoisoindolin-4-yl)acetamide (9b)

Compound 9b was synthesized using the method described for 9a except for the use of 8b (66 mg, 148.51 μmol). Yield: 40 mg, 34.3%; m.p. 172–174 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.17 (s, 1H, –CO–NH–CO–), 10.34 (s, 1H, amide-H), 8.72 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 1,3-dioxoisoindoline H-6), 8.53 (s, 1H, triazole-H), 7.85 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H, 1,3-dioxoisoindoline H-7), 7.62 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H, 1,3-dioxoisoindoline H-5), 7.45 (s, 1H, quinazoline H-8), 7.23 (s, 2H, –NH2), 6.77 (s, 1H, quinazoline H-5), 5.17 (dd, J = 12.7, 5.2 Hz, 1H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-3), 4.68–4.52 (s, 2H, –NH–CO–CH2–O–), 4.12–3.64 (m, 22H, triazole–CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–O–, –OCH3 at quinazoline C-6, –OCH3 at quinazoline C-7, piperazine-H), 2.98–2.82 (m, 1H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-4), 2.58 (m, 2H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-5), 2.17–2.02 (m, 1H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-4). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 173.20, 170.21, 169.65, 168.76, 167.17, 161.63, 160.03, 154.75, 145.59, 143.45, 136.94, 136.44, 131.75, 129.49, 124.83, 118.76, 116.54, 104.19, 103.39, 71.01, 70.54, 69.88, 68.97, 56.32, 55.93, 55.38, 50.13, 49.45, 46.53, 44.58, 43.90, 42.51, 31.42, 22.42. ESI-HRMS: m/z [M+H]+ Calcd. for C36H40N11O10+ 786.2954, Found 786.2956. HPLC purity 95.6%, tR = 14.454 min, 250 mm × 4.60 mm, H2O as solvent A and CH3OH containing 0.1% triethylamine as solvent C, the gradient program was as follows: 40%–50% C (0–10 min), and 50% C (10–25 min), 1 mL/min.

4.1.14. 2-(2-(2-(2-(4-(4-(4-Amino-6,7-dimethoxyquinazolin-2-yl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)-N-(2-(2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-1,3-dioxoisoindolin-4-yl)acetamide (9c)

Alkyne 3 (83.87 mg, 245.67 μmol) and azides 8c (120 mg, 245.67 μmol) were dissolved in a mixed solvent of 3.9 mL of t-BuOH/H2O (2:1), 0.1 mol/L sodium ascorbate (9.82 mL) and 0.1 mol/L CuSO4 (2.45 mL) were sequentially added to the reaction mixture. After the reaction mixture was heated to 50 °C for 2 h in the dark, the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature and the solvent was removed by rotary evaporation. Then 2 mol/L NH4OH (10 mL) was added to the residue and extracted with dichloromethane (3 × 40 mL). The organic layer was combined and dried over MgSO4, and MgSO4 was removed by filtration and the solvent was evaporated; the crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography with methanol and dichloromethane (DCM/MeOH = 30:1–10:1) to afford yellow powder as desired product 9c. Yield: 40 mg, 37.2%; m.p. 149–155 °C, λmax = 345 nm, λex = 503 nm, λem = 540 nm. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.16 (s, 1H, –CO–NH–CO–), 10.33 (s, 1H, amide-H), 8.70 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 1,3-dioxoisoindoline H-6), 8.51 (s, 1H, triazole-H), 7.84 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H, 1,3-dioxoisoindoline H-7), 7.60 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H, 1,3-dioxoisoindoline H-5), 7.43 (s, 1H, quinazoline H-8), 7.16 (s, 2H, –NH2), 6.75 (s, 1H, quinazoline H-5), 5.16 (dd, J = 12.8, 5.3 Hz, 1H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-3), 4.57 (s, 2H, –NH–CO–CH2–O–), 4.20–3.55 (m, 26H, triazole–CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–O–, –OCH3 at quinazoline C-6, –OCH3 at quinazoline C-7, piperazine-H), 3.01–2.82 (m, 1H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-4), 2.68–2.52 (m, 2H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-5), 2.16–2.01 (m, 1H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-4). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 173.22, 170.22, 169.84, 168.70, 167.15, 161.61, 160.11, 158.70, 154.69, 145.50, 143.44, 136.93, 136.42, 131.74, 129.46, 124.82, 118.75, 116.49, 105.67, 104.13, 103.44, 71.26, 70.68, 70.16, 69.97, 68.81, 56.30, 55.89, 55.38, 50.01, 49.44, 46.67, 44.57, 43.92, 42.58, 31.41, 22.42. ESI-HRMS: m/z [M+H]+ Calcd. for C38H44N11O11+ 830.3216, Found 830.3216. HPLC purity 97.0%, tR = 13.762 min, 250 mm × 4.60 mm, H2O as solvent A and CH3OH containing 0.1% triethylamine as solvent C, the gradient program was as follows: 40%–50% C (0–10 min), and 50% C (10–25 min), 1 mL/min.

4.1.15. 2-(2-(2-(2-Azidoethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)-N-(2-(1-methyl-2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-1,3-dioxoisoindolin-4-yl)acetamide (10)

Intermediate 8c (336.8 mg, 689.52 μmol) was dissolved in 5 mL of anhydrous DMF at room temperature, and then K2CO3 (238.24 mg, 1.72 mmol) and iodomethane (132 μL, 2.07 mmol) were sequentially added to the reaction mixture. After stirring at room temperature for 6 h, the reaction solution was diluted with 120 mL of dichloromethane, and then washed with water and brine, respectively. After it was dried over MgSO4, MgSO4 was removed by filtration and the solvent was evaporated, the crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography with methanol and dichloromethane (DCM/MeOH = 30:1) to afford white powder as desired product 10. Yield: 230 mg, 66.4%. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.36 (s, 1H, amide-H), 8.74 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 1,3-dioxoisoindoline H-6), 7.88 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H, 1,3-dioxoisoindoline H-7), 7.64 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H, 1,3-dioxoisoindoline H-5), 5.23 (dd, J = 13.1, 5.3 Hz, 1H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-3), 4.21 (s, 2H, –NH–CO–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–), 3.79–3.74 (m, 2H, –NH–CO–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–), 3.71–3.66 (m, 2H, –NH–CO–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–), 3.64–3.49 (m, 8H, –O–CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–N3), 3.03 (s, 3H, –CH3), 2.90 (m, 1H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-4), 2.69–2.52 (m, 2H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-5), 2.13–2.02 (m, 1H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-4). ESI-MS: m/z [M+Na]+ Calcd. for C22H26N6NaO8+ 525.2, Found 525.5.

4.1.16. 2-(2-(2-(2-(4-(4-(4-Amino-6,7-dimethoxyquinazolin-2-yl)piperazine-1-carbonyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)ethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)-N-(2-(1-methyl-2,6-dioxopiperidin-3-yl)-1,3-dioxoisoindolin4-yl)acetamide (11)

Compound 11 was synthesized using the method described for 9a except for the use of compound 10 (60 mg, 119.41 μmol). Yield: 33 mg, 32.7%; m.p. 195–198 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 10.41 (s, 1H, amide-H), 8.65 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, 1,3-dioxoisoindoline H-6), 8.53 (s, 1H, triazole-H), 7.76 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H, 1,3-dioxoisoindoline H-7), 7.48 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H, 1,3-dioxoisoindoline H-5), 7.44 (s, 1H, quinazoline H-8), 7.25 (s, 2H, –NH2), 6.78 (s, 1H, quinazoline H-5), 5.17 (dd, J = 12.7, 5.3 Hz, 1H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-3), 4.59 (s, 2H, –NH–CO–CH2–O–), 4.17–3.56 (m, 26H, triazole–CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–O–CH2–CH2–O–, –OCH3 at quinazoline C-6, –OCH3 at quinazoline C-7, piperazine-H), 3.03 (s, 3H, –CH3), 2.80 (m, 1H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-4), 2.59 (m, 2H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-5), 2.15–2.03 (m, 1H, 2,6-dioxopiperidine H-4). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 169.65, 169.29, 168.61, 168.58, 167.99, 165.29, 164.31, 157.20, 154.38, 152.51, 143.16, 140.02, 139.27, 134.66, 131.37, 129.58, 126.75, 120.37, 116.09, 110.47, 110.14, 101.20, 69.96, 69.68, 68.88, 68.70, 56.83, 51.78, 47.45, 47.25, 44.62, 29.33, 25.66, 23.92. ESI-MS: m/z [M+H]+ Calcd. for C39H46N11O11+ 844.3, Found 844.5. HPLC purity 96.5%, tR = 17.673 min, 250 mm × 4.60 mm, H2O as solvent A and CH3OH containing 0.1% triethylamine as solvent C, the gradient program was as follows: 40%–50% C (0–10 min), and 50% C (10–25 min), 1 mL/min.

4.2. Biology assay

4.2.1. Cell culture

The medium for α1A-, α1B- and α1D-AR transfected stably HEK293 cells was DMEM, while the medium for PC-3 cells was RPMI-1640, and the above corresponding medium was supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum. Cells were cultured in a cell incubator at 37 °C humidified 5% CO2/95% air atmosphere.

4.2.2. Cell viability assay in vitro

The cell viability of α1A-, α1B- and α1D-AR transfected stably HEK293 cells, and PC-3 cells exposed to 9a–c, pomalidomide and prazosin, was determined using CCK-8 assay. The number of cells in the prepared cell suspension was counted by the cell counting plate, and then cells were seeded at a concentration of 5000 cells per well (200 μL) in a 96-well culture plate. After 24 h, cells were incubated with the indicated compounds for 48 h (the control group only added DMSO without any compounds or drugs). The CCK-8 reagents (PMS was purchased from J&K Chemicals Co., Ltd., Beijing, China. WST-8 was synthesized in our laboratory) were added to the well, and the cells were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. The absorbance at 450 nm of the medium was measured using a Thermo Scientific Microplate Reader (Thermofisher Scientific Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The cell viability calculation formula was as Eq. (1):

| (1) |

As, experimental well (culture medium containing cells, CCK-8, compound); Ab, control well (culture medium containing cells, CCK-8, without compound); Ac, blank well (culture medium without cells, CCK-8, without compound).

4.2.3. Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed with RIPA lysis and extraction buffer (Thermofisher Scientific Co., Ltd.) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail and the protein concentrations in the extracts were measured with a bicinchoninic acid assay (Thermofisher Scientific Co., Ltd.). Equal amounts of extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and then were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The membrane was blocked with 3% BSA for immunoblot analysis. Primary antibody for α1A-AR (ab137123, Abcam, Cambridge, England), primary antibody for α1B-AR (ab169523, Abcam), primary antibody for α1D-AR (sc-390884, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Shanghai, China), all of which were diluted at a ratio of 1:1000. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Proteintech Group, Inc., Wuhan, China.

4.2.4. Animal feeding and nude mice xenograft model

All animal studies were approved by the Ethics Committee and IACUC of Qilu Health Science Center of Shandong University (Jinan, China) and in accordance with European guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. Four-week-old nude mice were purchased from the SBF Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China. Nude mice were housed in groups under a 12:12 light–dark cycle at 25 °C with free access to food and water.

The nude mice were subcutaneously injected with PC-3 cells (106 cells/mouse). When the tumors had reached a volume of 400 mm3, the mice were divided into two groups (n = 5), and vehicle control (10% DMSO+10% PEG400 + 80% normal saline) or PROTAC 9c (50 mg/kg) was injected via the intraperitoneal administration every day for two weeks. The tumor volume and body weight were measured every 2–3 days. Tumor volume was monitored by caliper measurements along two orthogonal axes. And tumor volume was calculated as Eq. (2):

| (2) |

in the experiments, tumors were harvested 12 h after the last dose.

4.2.5. Immunohistochemistry

Tumor tissue was dissected, fixed in 4% polyformaldehyde, and embedded in paraffin. Tumor sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated in an ethanol series. Slides were immersed in of (pH 6.0) and maintained at a sub-boiling temperature for 8 min, standing for 8 min and then followed by another sub-boiling temperature for 7 min, and then washed three times with PBS (pH 7.4), 5 min each. Slides were immersed in 3% H2O2 and incubated at room temperature for 15 min in dark place. Then slides were washed again three times with PBS (pH 7.4) in a Rocker device, 5 min each. Objective tissues were covered with 3% BSA at room temperature for 30 min. Slides were incubated with primary antibody (diluted with PBS) overnight at 4 °C, placed in a wet box containing a little water, and then slides were washed three times with PBS (pH 7.4) in a Rocker device, 5 min each. Objective tissues were covered with secondary antibody labelled with HRP, incubated at room temperature for 50 min. DAB chromogenic reagent was used for color development. Nucleus stained with hematoxylin are blue. The positive cells developed by DAB reagent have brown-yellow nucleus.

4.2.6. Data analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5. The data were presented as the mean ± SEM of the indicated experimental number. The t-test was performed in both groups to determine the statistical differences. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21629201), the Shandong Natural Science Foundation (No. ZR2018ZC0233, China), the Taishan Scholar Program at Shandong Province, the Qilu/Tang Scholar Program at Shandong University, the Major Project of Science and Technology of Shandong Province (No. 2015ZDJS04001, China) and the Key Research and Development Project of Shandong Province (No. 2017CXGC1401, China).

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2020.01.014.

Author contributions

Minyong Li and Zhenzhen Li conceived and designed the study. Zhenzhen Li, Yuxing Lin and Zheng Zhang participated in chemical synthesis. Zhenzhen Li, Wei Zhao, Hui Song, Xiaojun Qin, Zhongxia Yu and Gaopan Dong contributed to activity evaluation. Zhenzhen Li, Yuxing Lin and Xiang Li analyzed all the data and written the manuscript. Minyong Li, Lupei Du and Xiaodong Shi revised the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Piascik M.T., Perez D.M. α1-Adrenergic receptors: new insights and directions. J Pharmacol Exp Therapeut. 2001;298:403–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhong H., Minneman K.P. α1-Adrenoceptor subtypes. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;375:261–276. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00222-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koshimizu T.A., Tanoue A., Hirasawa A., Yamauchi J., Tsujimoto G. Recent advances in α1-adrenoceptor pharmacology. Pharmacol Ther. 2003;98:235–244. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(03)00033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Docherty J.R. Subtypes of functional α1-adrenoceptor. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:405–417. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0174-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kojima Y., Sasaki S., Hayashi Y., Tsujimoto G., Kohri K. Subtypes of α1-adrenoceptors in BPH: future prospects for personalized medicine. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2009;6:44–53. doi: 10.1038/ncpuro1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nasu K., Moriyama N., Kawabe K., Tsujimoto G., Murai M., Tanaka T. Quantification and distribution of α1-adrenoceptor subtype mRNAs in human prostate: comparison of benign hypertrophied tissue and non-hypertrophied tissue. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;119:797–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15742.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kojima Y., Sasaki S., Shinoura H., Hayashi Y., Tsujimoto G., Kohri K. Quantification of α1-adrenoceptor subtypes by real-time RT-PCR and correlation with age and prostate volume in benign prostatic hyperplasia patients. Prostate. 2006;66:761–767. doi: 10.1002/pros.20399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bray F., Ren J.S., Masuyer E., Ferlay J. Global estimates of cancer prevalence for 27 sites in the adult population in 2008. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:1133–1145. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatterjee B. The role of the androgen receptor in the development of prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer. Mol Cell Biochem. 2003;253:89–101. doi: 10.1023/a:1026057402945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Batty M., Pugh R., Rathinam I., Simmonds J., Walker E., Forbes A. The role of α1-adrenoceptor antagonists in the treatment of prostate and other cancers. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1339–1364. doi: 10.3390/ijms17081339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi T., Gaivin R.J., McCune D.F., Gupta M., Perez D.M. Dominance of the α1B-adrenergic receptor and its subcellular localization in human and TRAMP prostate cancer cell lines. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2007;27:27–45. doi: 10.1080/10799890601087487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thebault S., Roudbaraki M., Sydorenko V., Shuba Y., Lemonnier L., Slomianny C. α1-Adrenergic receptors activate Ca2+-permeable cationic channels in prostate cancer epithelial cells. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1691–1701. doi: 10.1172/JCI16293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kyprianou N., Benning C.M. Suppression of human prostate cancer cell growth by α1-adrenoceptor antagonists doxazosin and terazosin via induction of apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4550–4555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neklesa T.K., Winkler J.D., Crews C.M. Targeted protein degradation by PROTACs. Pharmacol Ther. 2017;174:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai A.C., Crews C.M. Induced protein degradation: an emerging drug discovery paradigm. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16:101–114. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2016.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toure M., Crews C.M. Small-molecule PROTACS: new approaches to protein degradation. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:1966–1973. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y., Jiang X., Feng F., Liu W., Sun H. Degradation of proteins by PROTACs and other strategies. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020;10:207–238. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2019.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneekloth A.R., Pucheault M., Tae H.S., Crews C.M. Targeted intracellular protein degradation induced by a small molecule: en route to chemical proteomics. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:5904–5908. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.07.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai A.C., Toure M., Hellerschmied D., Salami J., Jaime-Figueroa S., Ko E. Modular PROTAC design for the degradation of oncogenic BCR-ABL. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2016;55:807–810. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu J., Qian Y., Altieri M., Dong H., Wang J., Raina K. Hijacking the E3 ubiquitin ligase cereblon to efficiently target BRD4. Chem Biol. 2015;22:755–763. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gadd M.S., Testa A., Lucas X., Chan K.H., Chen W., Lamont D.J. Structural basis of PROTAC cooperative recognition for selective protein degradation. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13:514–521. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Itoh Y., Ishikawa M., Naito M., Hashimoto Y. Protein knockdown using methyl bestatin-ligand hybrid molecules: design and synthesis of inducers of ubiquitination-mediated degradation of cellular retinoic acid-binding proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:5820–5826. doi: 10.1021/ja100691p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Demizu Y., Okuhira K., Motoi H., Ohno A., Shoda T., Fukuhara K. Design and synthesis of estrogen receptor degradation inducer based on a protein knockdown strategy. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:1793–1796. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.11.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bondeson D.P., Mares A., Smith I.E.D., Ko E., Campos S., Miah A.H. Catalytic in vivo protein knockdown by small-molecule PROTACs. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:611–617. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Itoh Y., Kitaguchi R., Ishikawa M., Naito M., Hashimoto Y. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of nuclear receptor-degradation inducers. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:6768–6778. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohoka N., Nagai K., Hattori T., Okuhira K., Shibata N., Cho N. Cancer cell death induced by novel small molecules degrading the TACC3 protein via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5 doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma Z., Lin Y., Cheng Y., Wu W., Ca R., Chen S. Discovery of the first environment-sensitive near-infrared (NIR) fluorogenic ligand for α1-adrenergic receptors imaging in vivo. J Med Chem. 2016;59:2151–2162. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang W., Ma Z., Li W., Li G., Chen L., Liu Z. Discovery of quinazoline-based fluorescent probes to α1-adrenergic receptors. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2015;6:502–506. doi: 10.1021/ml5004298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edmondson S.D., Yang B., Fallan C. Proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) in ‘beyond rule-of-five' chemical space: recent progress and future challenges. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2019;29:1555–1564. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fischer E.S., Boehm K., Lydeard J.R., Yang H., Stadler M.B., Cavadini S. Structure of the DDBI-CRBN E3 ubiquitin ligase in complex with thalidomide. Nature. 2014;512:49–53. doi: 10.1038/nature13527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chamberlain P.P., Lopez-Girona A., Miller K., Carmel G., Pagarigan B., Chie-Leon B. Structure of the human Cereblon-DDB1-lenalidomide complex reveals basis for responsiveness to thalidomide analogs. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21:803–809. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin S.C., Chueh S.C., Hsiao C.J., Li T.K., Chen T.H., Liao C.H. Prazosin displays anticancer activity against human prostate cancers: targeting DNA and cell cycle. Neoplasia. 2007;9:830–839. doi: 10.1593/neo.07475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Forbes A., Anoopkumar Dukie S., Chess Williams R., McDermott C. Relative cytotoxic potencies and cell death mechanisms of α1-adrenoceptor antagonists in prostate cancer cell lines. Prostate. 2016;76:757–766. doi: 10.1002/pros.23167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liao C.H., Guh J.H., Chueh S.C., Yu H.J. Anti-angiogenic effects and mechanism of prazosin. Prostate. 2011;71:976–984. doi: 10.1002/pros.21313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Desiniotis A., Kyprianou N. Advances in the design and synthesis of prazosin derivatives over the last ten years. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2011;15:1405–1418. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2011.641534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hori Y., Ishii K., Kanda H., Iwamoto Y., Nishikawa K., Soga N. Naftopidil, a selective α1-adrenoceptor antagonist, suppresses human prostate tumor growth by altering interactions between tumor cells and stroma. Cancer Prev Res. 2011;4:87–96. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Youm Y.H., Yang H., Yoon Y.D., Kim D.Y., Lee C., Yoo T.K. Doxazosin-induced clusterin expression and apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. Urol Oncol. 2007;25:483–488. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cal C., Uslu R., Gunaydin G., Ozyurt C., Omay S.B. Doxazosin: a new cytotoxic agent for prostate cancer?. BJU Int. 2000;85:672–675. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anglin I.E., Glassman D.T., Kyprianou N. Induction of prostate apoptosis by α1-adrenoceptor antagonists: mechanistic significance of the quinazoline component. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2002;5:88–95. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keledjian K., Kyprianou N. Anoikis induction by quinazoline based α1-adrenoceptor antagonists in prostate cancer cells: antagonistic effect of bcl-2. J Urol. 2003;169:1150–1156. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000042453.12079.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.