Abstract

Purpose:

Multiple myeloma (MM) treatment has changed tremendously, with significant improvement in patient out-comes. One group with a suboptimal benefit is patients with high-risk cytogenetics, as tested by conventional karyotyping or fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Methodology for these tests has been published, but not necessarily standardized.

Methods:

We address variability in the testing and reporting methodology for MM cytogenetics in the United States using the ongoing African American Multiple Myeloma Study (AAMMS). We evaluated clinical and cytogenetic data from 1,221 patients (1,161 with conventional karyotyping and 976 with FISH) tested between 1998 and 2016 across 58 laboratories nationwide.

Results:

Interlab and intralab variability was noted for the number of cells analyzed for karyotyping, with a significantly higher number of cells analyzed in patients in whom cytogenetics were normal (P 5.0025). For FISH testing, CD138-positive cell enrichment was used in 29.7% of patients and no enrichment in 50% of patients, whereas the remainder had unknown status. A significantly smaller number of cells was analyzed for patients in which CD138 cell enrichment was used compared with those without such enrichment (median, 50 v 200; P, .0001). A median of 7 loci probes (range, 1-16) were used for FISH testing across all laboratories, with variability in the loci probed even within a given laboratory. Chromosome 13–related abnormalities were the most frequently tested abnormality (n5956; 97.9%), and t(14;16) was the least frequently tested abnormality (n 5 119; 12.2%).

Conclusions:

We report significant variability in cytogenetic testing across the United States for MM, potentially leading to variability in risk stratification, with possible clinical implications and personalized treatment approaches.

INTRODUCTION

Multiple myeloma (MM) is the second most common hematologic malignancy, with more than 30,000 new patients diagnosed in 2018.1 Death rates have been decreasing steadily over the last decade, with a current reported 5-year relative survival rate of 50.7%.1-3 Despite these encouraging trends, there are MM subtypes based on cytogenetic prognostic markers with high-risk disease that tend to have significantly worse outcomes.4,5 Results of cytogenetic testing are useful beyond prognostication and are now being used to select therapeutic strategies for patients.6,7 Thus, cytogenetic testing has become integrated into routine clinical practice for patients with MM and is now the standard of care at the time of initial diagnosis. Moreover, it has been reported that MM biology can change with treatment, with acquisition of new cytogenetic abnormalities with passage of time,8 requiring frequent cytogenetic testing in the setting of relapsed MM as well. The traditional method of cytogenetic testing by metaphase karyotyping is still used, but increasingly less so, and has been replaced by interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) as the new standard of care.9 Although conventional metaphase karyotyping can provide a global view of genetic abnormalities in the entire cell, molecular cytogenetics using the FISH technique is more efficient and precise, although it provides information on prespecified, targeted abnormalities only. The sensitivity of detection by metaphase karyotyping and FISH is different, with FISH being more sensitive.10 The importance of standardized testing methodologies in the care of patients with MM is clear; clinicians as well as patients depend heavily on their results and the validity of the technique.

Blacks have a 1.5- to 2-fold higher risk of MM and earlier onset than European Americans (EAs), but similar or better survival.11 We sought to explore the variability in the testing and reporting methodology for MM cytogenetics in the United States using the ongoing African American Multiple Myeloma Study (AAMMS) with data collected from 12 national Comprehensive Cancer Centers and 4 National Cancer Institute (NCI)-SEER cancer registries.12

METHODS

Study participants were recruited as part of the ongoing AAMMS Genome-Wide Admixture Study, for which the design and recruitment methods have been previously described.12 Briefly, English-speaking Black patients with MM diagnosed between January 1, 1998, and December 31, 2016, were ascertained and recruited from 11 national Comprehensive Cancer Centers and 4 NCI-SEER registries. Blood or saliva samples were obtained from patients, and information on lifestyle, family history, and medical history was obtained by interviews. Detailed clinical information was obtained from medical records from patients ascertained in clinics and hospitals; SEER registries provided only partial information from pathology reports. Patients with a prior allogeneic stem cell transplantation were excluded. Similar information collected from clinical records of EA patients with MM matched on sex, age (within 5 years), and date of diagnosis (within 5 years) from 4 of the participating cancer centers as controls for a comparison group for analyses within the AAMMS were also included in this study. Approval was obtained by the respective contributing site institutional review boards according to the Declaration of Helsinki Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects (1964), and signed informed consent was obtained from all patients providing data for this study by the respective sites collecting the samples and data.

MM clinical data were abstracted from patients’ medical records, the registry abstract, and/or pathology reports according to availability. De-identified patient data, including cytogenetic reports, were sent to the data-coordinating center at the University of Southern California (Los Angeles, CA), where 4 trained members of the study team abstracted data from cytogenetic reports using a standardized data collection form. Participants without cytogenetic reports were excluded from the analyses described here, as were participants with missing information on the laboratory where the cytogenetic testing was conducted or the timing of cytogenetic testing (at initial diagnosis or at the time of disease relapse). When patient records contained more than one cytogenetic report, the abstractors selected the one performed in closest proximity to initiating MM treatment. This was due to a practice noted for certain laboratories where a more comprehensive FISH analysis was performed at the time of initial diagnosis and a targeted FISH was performed at the time of subsequent testing for the same patient.

Karyotyping (timing, number of cells evaluated, number of abnormal cells reported, and types of abnormalities) and FISH (timing, number and type of cells tested, loci and probes included, and types of abnormalities reported) data were summarized. For conventional karyotyping, a typical report describes 20 cells identified and evaluated in metaphase. We categorized the patients from each laboratory into 3 reporting categories, with < 20 cells, 20 cells, or > 20 cells. To study FISH processing methodology, laboratories were divided into 3 categories: laboratories using CD138-positive–enriched samples, laboratories using unenriched samples, and those with unreported/unknown methodology. Unsuccessful tests due to an insufficient number of cells were excluded from analysis. Values for continuous and categorical variables were compared across testing facilities using Kruskal-Wallis and χ2 tests, respectively, with a significance level of P < .05. We did not evaluate any racial variation in FISH or karyotype testing between EA and Black patients because typically the laboratories performing the cytogenetic analysis do not receive this information and are not influenced by it.

RESULTS

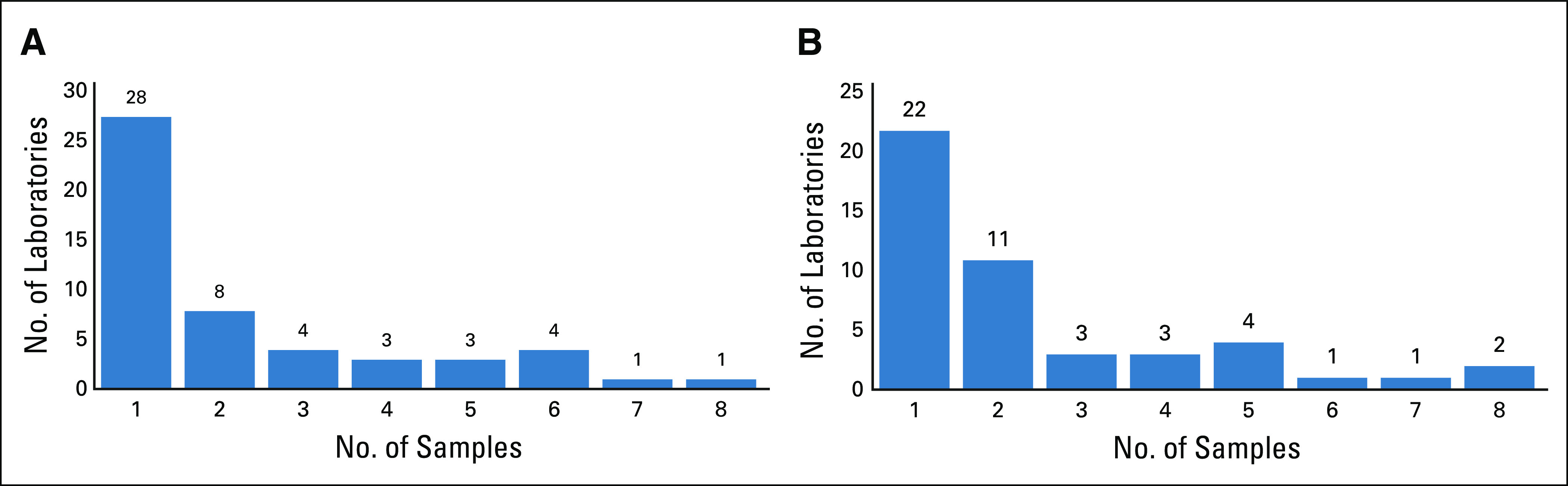

The study cohort included a total of 1,221 patients who underwent cytogenetic testing between the years 1998 and 2016 (Black, 937; EA, 284). This included 1,161 patients (95%) with conventional karyotype testing and 976 patients (79.9%) with FISH testing, with many patients having cytogenetic testing performed by both karyotyping and FISH. Testing was performed at a total of 58 laboratories. Selected patient and laboratory-specific characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The distribution of laboratories by number of patients tested showed that a minority of laboratories tested a large proportion of the samples. Nine laboratories were considered high volume (> 25 patients tested) for conventional karyotyping, whereas 8 were high-volume laboratories for FISH testing. The remaining laboratories tested a smaller number of patients, with 28 testing only 1 patient by conventional karyotyping and 22 testing only 1 patient by FISH (Figs 1A and 1B).

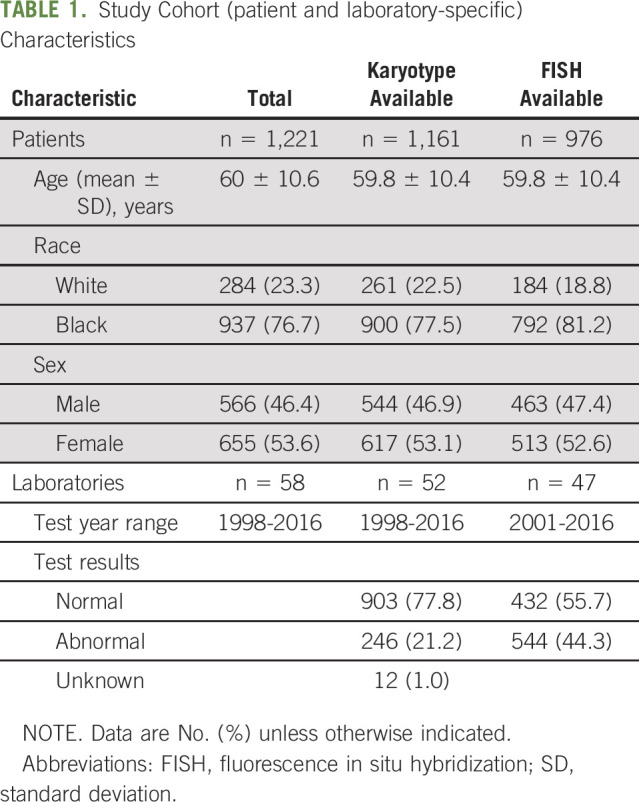

TABLE 1.

Study Cohort (patient and laboratory-specific) Characteristics

Fig 1.

(A) Laboratory distribution for the patients tested by conventional karyotyping (1,161 patients from 52 laboratories). (B) Laboratory distribution for the patients tested by fluorescence in situ hybridization (976 samples from 47 laboratories).

Conventional Karyotyping

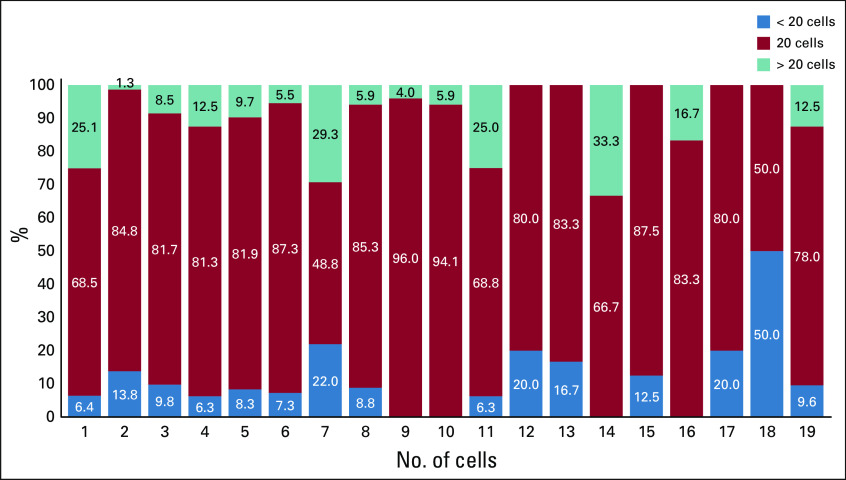

Figure 2 shows that of the 52 laboratories where karyotyping was performed, 18 reported inconsistencies in the number of cells analyzed (representing 1,089 patients). Of these, 78% of patients had 20 cells analyzed, 12.5% had > 20 cells, and 9.5% had < 20 cells. Nine of the 18 laboratories reported using each of the 3 cell categories for different patients, whereas the other 9 reported using at least 2 of the categories. The remainder included 28 laboratories where only 1 patient each was evaluated (Fig 2), with varying numbers of cells counted. We noted that a higher number of cells was counted in patients where cytogenetics were normal (median, 20; range, 1-80) compared with those with some cytogenetic abnormality (median, 20; range, 4-45; P = .0025; nonparametric Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test). Although a smaller number of cells may have been evaluated in patients where 20 metaphases were not available within a given sample, we noted heterogeneity in reporting with no specific pattern. Without details available for reasons why fewer cells may have been evaluated, the laboratories reported a range of 1-80 cells.

Fig 2.

Intralab and interlab variability in number of cells analyzed for reporting metaphase karyotyping. Data on 18 of a total of 52 laboratories (1,089 samples, representing 93.8% of the total study samples with karyotypes), which are the labs with variations in the evaluated cell numbers. They reported at least 2 of the 3 reporting categories of less than, equal to, or greater than 20 cells in patients analyzed. Karyotyping or cytogenetic testing in general evaluates on average 20 cells to identify the patient karyotypes. The other 34 unlisted labs included 28 labs with a single sample (20 labs testing 20 cells, 3 labs testing < 20 cells, 3 labs testing > 20 cells, and 2 labs with missing numbers), 3 labs with 2 samples all testing 20 cells, 2 labs with 3 samples all testing 20 cells.

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization

FISH testing was performed at 47 laboratories. Here, the main sources of variability among the laboratories were enrichment for CD138-positive plasma cells and the number of cells counted to determine the FISH result. Laboratories using CD138-positive enrichment evaluated a median of 50 plasma cells (range, 3-1,400), whereas those that did not evaluated a median of 200 (range, 3-900) plasma cells (P < .0001; nonparametric Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test). Laboratories with an unknown CD138-positive cell enrichment status also reported a median of 200 cells (range, 19-600), but there was higher variability among these laboratories, probably representing a mixture of methodologies (Fig 3A). Overall, 29.7% of the patients had testing with CD138-positive cell enrichment, 50% with no enrichment, and 20.3% had unknown CD138 enrichment status. Twenty-six of the 47 FISH laboratories (55%) reported using consistent methodology: 1 laboratory used only used CD138-positive–enriched samples, 15 used only samples that were not enriched, 10 consistently did not report the enrichment status of the samples, and the remaining 21 reported using at least 2 of the 3 variations for CD138 enrichment (Fig 3B). We also evaluated trends in use of CD138 enrichment by laboratories and noted that there was a significant increase in this over time (1-sided P = .0214; 2-sided P = .042; Cochran-Armitage trend test; Fig 3C).

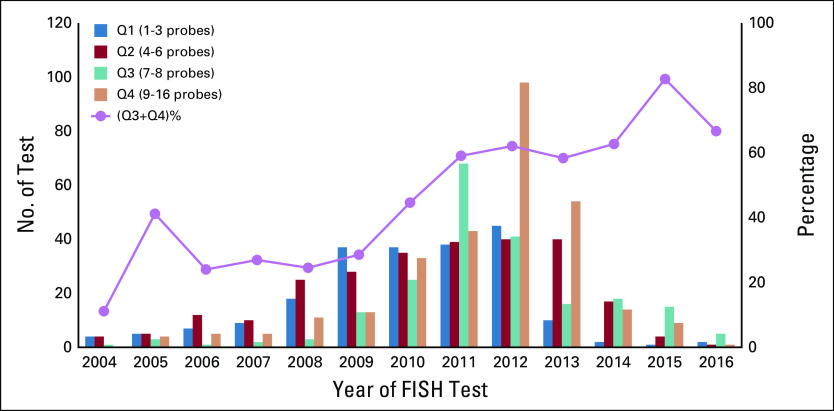

Fig 3.

Type and number of cells evaluated by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) across the laboratories. (A) Bone marrow evaluation included a median of 50 cells for CD138-positive (+)–enriched samples and a median of 200 cells without enrichment. In general, 50 CD138+-enriched cells were used, whereas 200 bone marrow cells without enrichment were used for FISH. (B) Intralab and interlab variability in using CD138+-enriched versus nonenriched samples for reporting FISH testing. Data on 21 of a total of 47 laboratories (943 samples, representing 96.6% of the total study samples with variations in the cell numbers), which reported at least 2 of the 3 methods of CD138+-enriched, not enriched, and unknown. (C) CD138-enriched cell type used for FISH over time. Data for years 2001-2003 were excluded because fewer than 2 tests were available for those years. Test years shown on the x-axis. Primary y-axis (left) shows the number of tests for each cell type (CD138 enriched and not enriched; box-plot) in each year, whereas the secondary y-axis (right) shows the percentage of tests for that year using CD138 enriched cells (line plot). (D) Intralab and interlab variability in the number of loci probed for FISH testing. Data on 24 of a total of 47 laboratories that had variability in the number of FISH probes tested per patient at that laboratory are shown. These patients represent 951 samples (97.4% of samples with FISH tests) included in the study. (E) Number of probes used per FISH test over time. Data for years 2001-2003 were excluded because fewer than 2 tests were available for those years. Test years shown on x-axis. Primary y-axis (left) shows the number of tests for each quartile (Q; Q1, 1-3 probes; Q2, 4-6 probes; Q3, 7-8 probes; Q4, 9-16 probes; box-plot) in each year, whereas the secondary y-axis (right) shows the percentage of the sum of Q3 and Q4 (7-16 probes; line-plot).

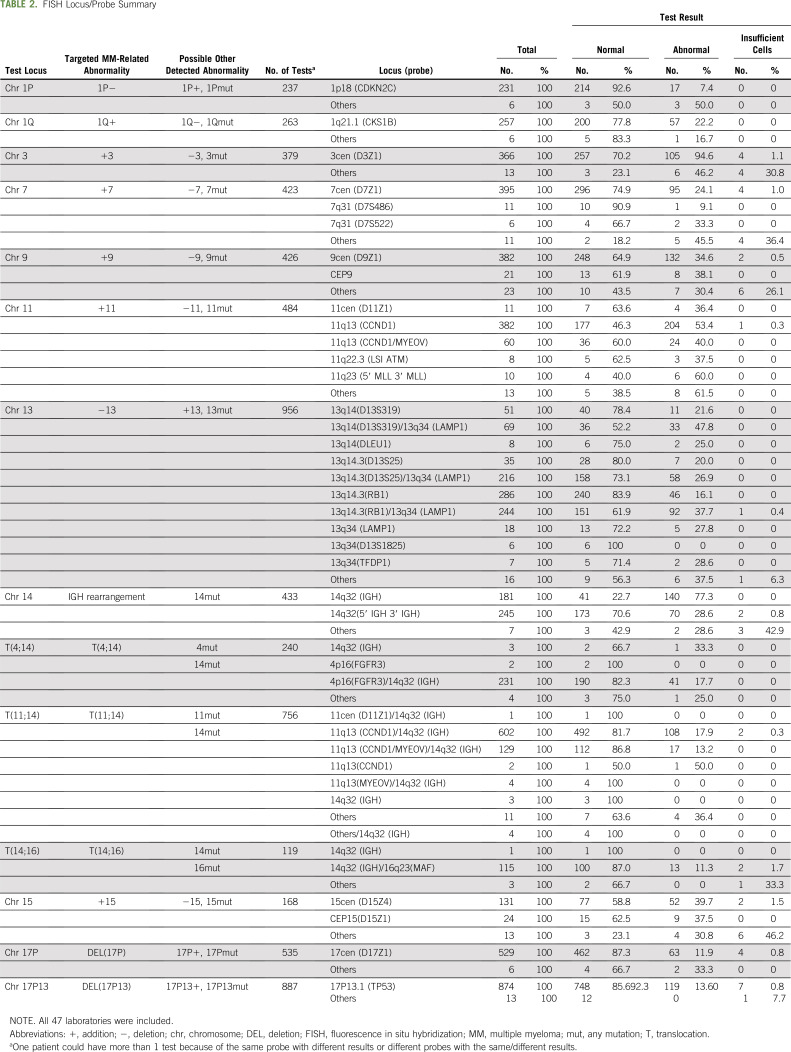

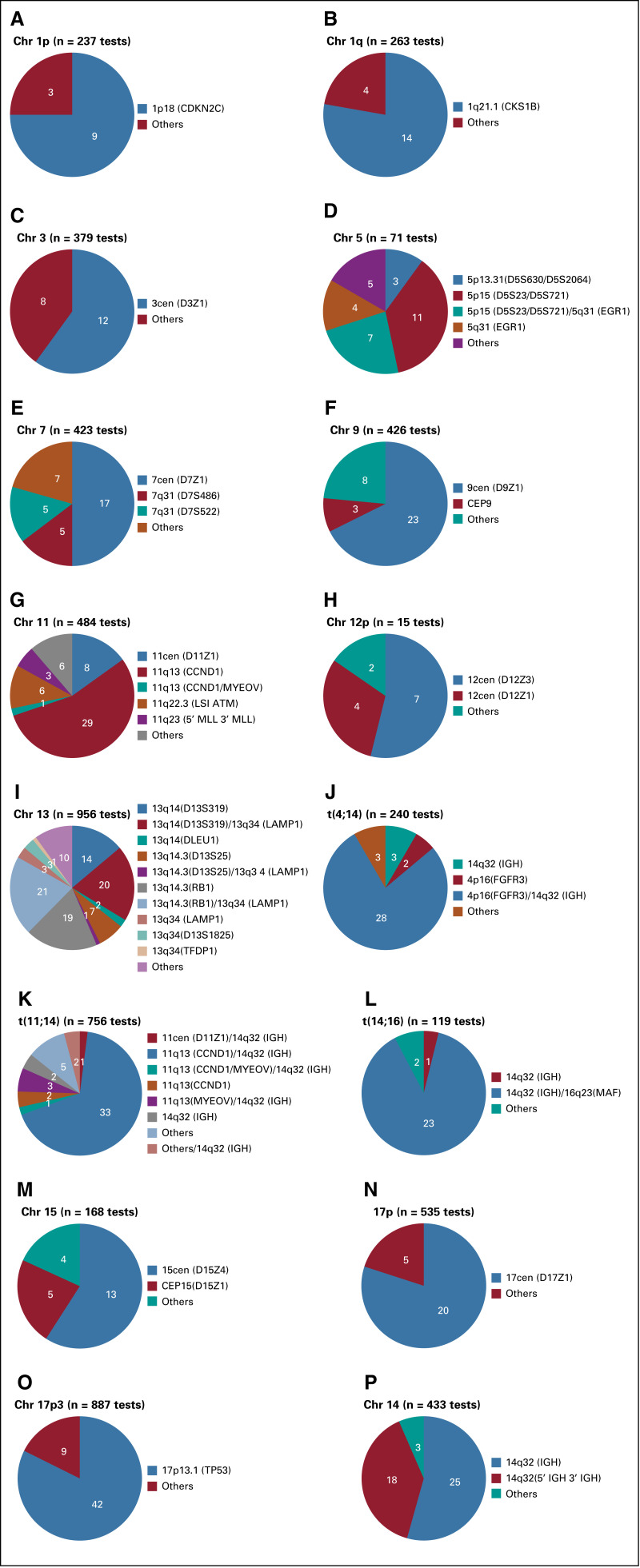

The number and type of specific probes used for FISH testing also varied among laboratories. A median of 7 loci probes (range, 1-16) were used for FISH testing across all laboratories. Twenty-two laboratories tested only 1 sample by FISH and reported a median of 9 loci probes (range, 1-11 probes). Another laboratory tested 3 samples and reported 5 probes for all those patients. Data for interlab and intralab variability for the number of FISH probes used in the rest of the 24 laboratories, representing 97.4% of the samples tested, are shown in Figure 3D. There was variability in the loci probed for FISH even within a given laboratory, with a different number of probes used in samples tested at the same laboratory. We did not have available data to determine whether the variability in probes was related to whether the specimen was tested at the time of initial diagnosis or when a repeat bone marrow aspiration may have been performed for that patient. Chromosome 13–related abnormalities were the most frequently tested (n = 956; 97.9%), whereas t(14;16) was the least frequently tested (n = 119; 12.2%). The largest number of different probes was used for detecting abnormalities in chromosome 13. We tested whether the number of FISH probes used overall increased over time. The number of probes ranged from 1-16 per test. We categorized the number of probes by quartiles and found that there was a significantly higher number of probes used per FISH test over time (1-sided P < .0001; 2-sided P < .0001; Somers’ D test; Fig 3E). Table 2 and Figure 4 depict the various probes used and the loci that they represent to detect the FISH abnormalities for patients with MM analyzed along with the distribution of laboratories that used these specific probes.

TABLE 2.

FISH Locus/Probe Summary

Fig 4.

Variability in the probes used for a given target locus for fluorescence in situ hybridization testing among various laboratories. Each pie diagram represents a target locus tested. (A) Chromosome (chr) 1p, (B) chr 1q, (C) chr 3, (D) chr 5, (E) chr 7, (F) chr 9, (G) chr 11, (H) chr 12, (I) chr 13t, (J) t(4;14), (K) t(11;14), (L) t(14;16), (M) chr 15, (N) chr 17p, (O) chr 17p3, (P) chr 14, and the number of laboratories reporting each variation of the probes for that locus.

DISCUSSION

We used a large database available from the AAMMS to interrogate the variability of cytogenetic testing among patients with MM across the United States. Although Black patients are at higher risk for developing MM, their disease is not associated with an increased frequency of cytogenetic abnormalities, especially high-risk cytogenetics, as has been recently reported from the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation’s CoMPASS clinical trial.13

Conventional metaphase karyotyping and interphase FISH may be used together to obtain the most comprehensive cytogenetic information available for clinical decision making in patients with MM.10 Although there has been some guidance regarding how to interpret and use each of these tests individually,10 in routine clinical practice, karyotyping and FISH are frequently used interchangeably, depending on availability of the testing methodology, preference and understanding of the ordering practitioner, and perceived utility of the particular test. Although there has been variability in use of these tests, there are also differences in how these tests may be performed by various laboratories across the country. This introduces a layer of unpredictability in the correct clinical assessment of patients with MM, which has never been explored previously. Our analysis describes several elements of this variability, which is of clinical significance.

Although the median number of chromosomes reported for conventional metaphase karyotyping was 20, the range was as low as 1 and as high as 80 cells. We note that a significantly higher number of cells were analyzed and reported by laboratories when cytogenetic results were normal compared with when any karyotypic abnormality was noted (P = .0025). It is plausible that when a karyotypic abnormality was noted, the laboratory discontinued additional analysis of the sample but this is not considered a standard approach, and we could not find any reference to support this hypothesis. This lack of standardization makes it difficult to compare results across laboratories. In addition, there may be inaccuracies for reports based on a small number of cells, because these may not be a true representation of the distribution of somatic mutations. There have been previous guidelines suggesting how to evaluate cytogenetics in various clinical settings, including in cancer, where it has been recommended that at least 15-20 cells be analyzed to select a minimum of 2 cells for karyotyping.14 Although it is possible to obtain clinically meaningful inferences with a fewer number of cells, a standardized measure would be of immense clinical benefit to a practicing clinician as well as the patient with MM. The notable finding in our analysis was that even within a given laboratory, there was significant variability in the number of cells analyzed among the various sam-ples tested.

FISH testing was noted to have a much more nuanced variability, with several factors contributing to the differences among the laboratories studied. Plasma cell enrichment has been proposed as a method to increase the yield and accuracy of FISH testing,15 yet we found that this technique is not being universally used. Reasons for this could include cost, lack of technical expertise, and more time and effort necessary for enrichment. In our analysis, the majority of the laboratories performed FISH testing without CD138 cell enrichment. We observed that analysis of more cells was necessary for diagnosis of patients where there was no enrichment, compared with patients with enriched plasma cells. There are no data on whether analysis of more cells produces a result similar to analysis with enriched plasma cells, but such an analysis would be beneficial to standardize the process. Recently, newer methodologies of cell enrichment and targeted FISH have been developed16-18; thus, the issue of whether to uniformly enrich plasma cells and the ideal technique to achieve this should be addressed. Indeed, it has been reported previously that FISH results are dependent not only on whether enrichment is performed, but also on the method of enrichment.15,19 It was encouraging to see in our analysis that over time there was an increase in the number of laboratories that used CD138-positive cell enrichment for FISH testing.

There were several laboratories that evaluated a small number of patients. Although these were Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments certified, it is unclear whether the expertise and standardization procedures of these laboratories would be the same as those that tested a much higher number of samples. A clinical practice or a patient may not have any control over where the samples are sent for pathology evaluation, which likely depends on existing contracts between the clinical practice and the particular laboratory.

There is a focus on optimal management of patients with MM with high-risk cytogenetics because they have benefitted the least from novel therapeutics.20 We noted that there was substantial variability in the specific mutations tested by FISH and the probes used to test those mutations among the laboratories. Several guidelines and consensus statements have defined what genetic abnormalities should be classified as high-risk MM based on significant prognostic implications for the patients.5,21-24 We did not observe any uniformity in the panel of mutations tested across different laboratories. There were certainly some abnormalities among the intermediate to high-risk MM subgroups, for example, t(11;14)- or chromosome 13– and chromosome 17–related mutations, which were reported more frequently than others, such as t(4;14)- or chromosome 1–related mutations. Of note, the classification of mutations in MM has also evolved over time, but our dataset predates the new classification that now focuses on standard and high-risk MM only, without mention of the intermediate-risk category.5 We were not able to determine a specific pattern of testing or criteria, which determined the panel of mutations tested in any given patient. We hypothesized that a laboratory might use a different probe set for FISH testing for evaluating repeat samples for a given patient compared with initial diagnostic testing, a process that has been previously recommended.10 We attempted to control for this by evaluating only the initial (diagnostic) sample available for a patient and excluding repeat testing for the same patient, but the variability in testing still persisted. Thus, this hypothesis could not explain the variability we observed. Of course, the patient may have had prior testing that was not included in our analysis, but that is less likely because the bone marrow biopsies included were at the time of MM diagnosis per accompanied case report forms and bone marrow biopsy pathology report documentation. We noted that over time, the number of probes used per patient significantly increased, which could be related to the evolving knowledge about MM biology and technical advancement in FISH testing.

We also observed significant differences in the probes used to test the abnormalities at a given locus. Table 2 identifies the various probe sets used for a given locus among different laboratories and even within the same laboratory. Although the result from these different probes may have a uniform patient-level prognostic implication, it has been reported that the biologic impact of some of the mutations may depend on the methodology and percentage of cells found to have that mutation within a given patient sample. One example is alterations of the 17p chromosome, which harbors the TP53 gene, which are associated with a poor prognosis in patients with MM.5 There are several methods described to assess this alteration, including mutation in the TP53 gene or deletion of the 17p chromosome, 2 different molecular events with perhaps different clinical significance.25 Thus far, the clinical superiority of either method has not been definitively established. It is possible that the methodology used at a particular laboratory evolved over time, but we were not able to establish a particular pattern to support this. We noted that over time, the number of probes used for FISH testing as well as the use of CD138-enriched samples increased. These changes will certainly affect the rate of positivity for certain mutations and also uncover newer abnormalities, necessitating uniform guidelines and consensus methodology so that the variability in testing can be minimized and the methodologies retain clinical significance for patients.

The field of cancer biology is fast evolving, including the development of highly sensitive genomic analysis techniques useful for implementing personalized therapy. Indeed, next-generation sequencing, proteomics, and metabolomics are being increasingly described and showing benefit in cancers, including MM. Although it is important to develop new technology and improve medical care to ultimately benefit the patient, it is imperative to standardize these processes, including those technologies that are currently being used widely, such as karyotyping and FISH analysis. Because cytogenetics are being used as a standard-of-care therapeutic and prognostic decision tool routinely, it is necessary for the international myeloma community to devise a standardized methodology and interpretation guideline for cytogenetic analysis in patients with MM.

Footnotes

Y.Y., N.B.W., and A.E.H. are co-first authors.

W.C. and S.A. are co-senior authors.

See the accompanying article 10.1200/JOP.19.00309

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Niquelle Brown Wade, Amie E. Hwang, Daniel Stram, Howard Terebelo, Carol A. Huff, Wendy Cozen, Sikander Ailawadhi

Financial support: Christopher A. Haiman, Wendy Cozen

Administrative support: Wendy Cozen

Provision of study materials or patients: Edward S. Peters, Karen Pawlish, Cathryn Bock, Howard Terebelo, Brian Chiu, Jeffrey A. Zonder, Carol A. Huff, Robert Z. Orlowski, Wendy Cozen, Nalini Janakiraman, Leon Bernal-Mizrachi

Collection and assembly of data: Yang Yu, Niquelle Brown Wade, Amie E. Hwang, Ajay K. Nooka, Mark A. Fiala, Edward S. Peters, Cathryn Bock, David J. Van Den Berg, Daniel Auclair, Christopher A. Haiman, Howard Terebelo, Brian Chiu, Carol A. Huff, Robert Z. Orlowski, Wendy Cozen, Sikander Ailawadhi, Kristin A. Rand, Graham A. Colditz, Nalini Janakiraman, Leon Bernal-Mizrachi

Data analysis and interpretation: Yang Yu, Niquelle Brown Wade, Amie E. Hwang, Ajay K. Nooka, Ann Mohrbacher, David V. Conti, Jayesh Mehta, Howard Terebelo, Seema Singhal, Brian Chiu, Ravi Vij, Jeffrey A. Zonder, Carol A. Huff, Sagar Lonial, Wendy Cozen, Sikander Ailawadhi, Kristin A. Rand, Graham A. Colditz, Nalini Janakiraman, Leon Bernal-Mizrachi

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Variability in Cytogenetic Testing for Multiple Myeloma: A Comprehensive Analysis from Across the United States

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Niquelle Brown Wade

Employment: Cigna

Ajay K. Nooka

Consulting or Advisory Role: Amgen, Janssen Oncology, Celgene, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Takeda, Oncopeptides, Karyopharm Therapeutics

Research Funding: Amgen (Inst), Janssen Oncology (Inst), Takeda (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: GSK

Daniel Stram

Employment: Personalis (I)

Graham A. Colditz

Consulting or Advisory Role: Grail

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Royalties as author for UptoDate

Jayesh Mehta

Honoraria: Celgene, Celgene (I), Takeda, Takeda (I), BMS, BMS (I), Janssen, Janssen (I)

Speakers’ Bureau: Celgene, Celgene (I), Takeda, Takeda (I), BMS, BMS (I), Janssen, Janssen (I)

Howard Terebelo

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene

Speakers' Bureau: Janssen Oncology

Seema Singhal

Honoraria: Celgene, Celgene (I), Takeda, Takeda (I), BMS, BMS (I), Janssen, Janssen (I)

Honoraria: Celgene, Celgene (I), Takeda, Takeda (I), BMS, BMS (I), Janssen, Janssen (I)

Ravi Vij

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, Janssen, Sanofi, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Amgen, Takeda, AbbVie

Research Funding: Amgen, Takeda, Celgene, Bristol-Myers Squibb

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Celgene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi, Janssen, DAVAOncology, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Amgen, Takeda, AbbVie

Leon Bernal-Mizrachi

Employment: Winship Cancer Institute, Kodikas Therapeutic Solutions, Takeda Science Foundation

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Kodikas Therapeutic Solutions

Honoraria: Celgene

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene

Research Funding: Takeda

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: We have discovered that translocation of NFKB2 predicts response to proteasome inhibitors. Test has been patented and licensed to Empire Genomics

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Celgene

Jeffrey A. Zonder

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Prothena, Janssen, Amgen, Takeda, Caelum, Intellia Therapeutics, Alnylam, Oncotherapeutics

Research Funding: Celgene (Inst), BMS (Inst)

Carol A. Huff

Consulting or Advisory Role: Karyopharm Therapeutics, Sanofi Genzyme, GlaxoSmithKline, miDiagnostics, Janssen

Research Funding: Ichnos (Inst)

Sagar Lonial

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen Oncology, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Amgen, AbbVie, Takeda, Merck, Juno Therapeutics

Research Funding: Celgene, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Takeda

Robert Z. Orlowski

Consulting or Advisory Role: Amgen, Celgene, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Legend Biotech, Molecular Partners, Sanofi- Aventis, Servier, Takeda, Kite Pharma, Juno Therapeutics, GSK Biologicals, FORMA Therapeutics, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen Biotech

Research Funding: BioTheryX

Sikander Ailawadhi

Consulting or Advisory Role: Amgen, Takeda, Celgene, Janssen Biotech

Research Funding: Pharmacyclics (Inst), Janssen Biotech (Inst), Cellectar (Inst), Phosplatin Therapeutics (Inst), Celgene (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Amgen, Takeda, Novartis

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A.Cancer statistics, 2018 CA Cancer J Clin 687–302018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ailawadhi S, Aldoss IT, Yang D, et al. Outcome disparities in multiple myeloma: A SEER-based comparative analysis of ethnic subgroups Br J Haematol 15891–982012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar SK, Dispenzieri A, Lacy MQ, et al. Continued improvement in survival in multiple myeloma: Changes in early mortality and outcomes in older patients Leukemia 281122–11282014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan HSH, Chen CI, Reece DE.Current review on high-risk multiple myeloma Curr Hematol Malig Rep 1296–1082017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajkumar SV.Multiple myeloma: 2016 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management Am J Hematol 91719–7342016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Usmani SZ, Sexton R, Ailawadhi S, et al. Phase I safety data of lenalidomide, bortezomib, dexamethasone, and elotuzumab as induction therapy for newly diagnosed symptomatic multiple myeloma: SWOG S1211. Blood Cancer J. 2015;5:e334. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2015.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar S, Kaufman JL, Gasparetto C, et al. Efficacy of venetoclax as targeted therapy for relapsed/refractory t(11;14) multiple myeloma Blood 1302401–24092017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fakhri B, Vij R.Clonal evolution in multiple myeloma Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 16S130–S1342016(suppl [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wan TS.Cancer cytogenetics: Methodology revisited Ann Lab Med 34413–4252014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rajan AM, Rajkumar SV. Interpretation of cytogenetic results in multiple myeloma for clinical practice. Blood Cancer J. 2015;5:e365. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2015.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ailawadhi S, Bhatia K, Aulakh S, et al. Equal treatment and outcomes for everyone with multiple myeloma: Are we there yet? Curr Hematol Malig Rep 12309–3162017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rand KA, Song C, Dean E, et al. A meta-analysis of multiple myeloma risk regions in African and European ancestry populations identifies putatively functional loci Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 251609–16182016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Manojlovic Z, Christofferson A, Liang WS, et al. Comprehensive molecular profiling of 718 multiple myelomas reveals significant differences in mutation frequencies between African and European descent cases. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1007087. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knutsen T, Bixenman HA, Lawce H, et al. Chromosome analysis guidelines--Preliminary report Cytogenet Cell Genet 541–41990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu G, Muddasani R, Orlowski RZ, et al. Plasma cell enrichment enhances detection of high-risk cytogenomic abnormalities by fluorescence in situ hybridization and improves risk stratification of patients with plasma cell neoplasms Arch Pathol Lab Med 137625–6312013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ma ES, Wang CL, Wong AT, et al. Target fluorescence in-situ hybridization (target FISH) for plasma cell enrichment in myeloma. Mol Cytogenet. 2016;9:63. doi: 10.1186/s13039-016-0263-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong H, Yang HS, Jagannath S, et al. Risk stratification of plasma cell neoplasm: Insights from plasma cell-specific cytoplasmic immunoglobulin fluorescence in situ hybridization (cIg FISH) vs. conventional FISH Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 12366–3742012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kishimoto RK, de Freitas SL, Ratis CA, et al. Validation of interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization (iFISH) for multiple myeloma using CD138 positive cells Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter 38113–1202016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartmann L, Biggerstaff JS, Chapman DB, et al. Detection of genomic abnormalities in multiple myeloma: The application of FISH analysis in combination with various plasma cell enrichment techniques Am J Clin Pathol 136712–7202011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sonneveld P, Avet-Loiseau H, Lonial S, et al. Treatment of multiple myeloma with high-risk cytogenetics: A consensus of the International Myeloma Working Group Blood 1272955–29622016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Avet-Loiseau H, Hulin C, Campion L, et al. Chromosomal abnormalities are major prognostic factors in elderly patients with multiple myeloma: The intergroupe francophone du myélome experience J Clin Oncol 312806–28092013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyd KD, Ross FM, Chiecchio L, et al. A novel prognostic model in myeloma based on co-segregating adverse FISH lesions and the ISS: Analysis of patients treated in the MRC Myeloma IX trial Leukemia 26349–3552012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palumbo A, Avet-Loiseau H, Oliva S, et al. Revised international staging system for multiple myeloma: A Report from International Myeloma Working Group J Clin Oncol 332863–28692015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sawyer JR.The prognostic significance of cytogenetics and molecular profiling in multiple myeloma Cancer Genet 2043–122011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lodé L, Eveillard M, Trichet V, et al. Mutations in TP53 are exclusively associated with del(17p) in multiple myeloma Haematologica 951973–19762010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]