Abstract

Genetic variations and adverse environmental events in utero or shortly after birth can lead to abnormal brain development and increased risk of schizophrenia. γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the mammalian brain, plays a vital role in normal brain development. GABA synthesis is controlled by enzymes derived from two glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) genes, GAD1 and GAD2, both of which produce transcript isoforms. While the full-length GAD1 transcript (GAD67) has been implicated in the neuropathology of schizophrenia, the transcript structure of GAD1 in the human brain has not been fully characterized. In this study, with the use of RNA sequencing and PCR technologies, we report the discovery of 10 novel transcripts of GAD1 in the human brain. Expression levels of four novel GAD1 transcripts (8A, 8B, I80, and I86) showed a life span trajectory expression pattern that is anticorrelated with the expression of the full-length GAD1 transcript. In addition, methylation levels of two CpG loci within the putative GAD1 promoter were significantly associated with the schizophrenia-risk SNP rs3749034 and with the expression of GAD25 in DLPFC. Moreover, schizophrenia patients who had completed suicide and/or were positive for nicotine exposure had significantly higher full-length GAD1 expression in the DLPFC. Alternative splicing of GAD1 and epigenetic state appear to play roles in the developmental profile of GAD1 expression and may contribute to GABA dysfunction in the PFC and hippocampus of patients with schizophrenia.

Introduction

γ- amino-butyric acid (GABA) is the major inhibitory neurotransmitter in the adult central nervous system; as such GABA modulates the firing pattern of intrinsic cortical neurons. Not only is GABA important in modulating excitation in the adult brain, in the developing brain it acts as a neurotrophic factor playing a role in cell migration, proliferation, and maturation1–3. GABA levels and signaling are regulated, in part, by glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), the rate-limiting enzyme in GABA synthesis4. The mammalian nervous system contains two major isoforms of GAD, named by their protein sizes of 67 and 65 kDa5,6. GAD67 and GAD65 transcripts are encoded by two separate genes, GAD1 and GAD2, located on different chromosomes in humans, and GAD67 accounts for the majority of overall GABA synthesis in the rodent brain7–9.

Postmortem and genetic studies have implicated GABA in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. One of the most replicated findings is a decrease in GAD1 full-length mRNA in the prefrontal cortex and other neocortical brain regions in schizophrenia10–13. Allelic variations surrounding the proximal promoter of the GAD1 gene have been associated with both schizophrenia and GAD67 expression14–17. The transcriptional start site of GAD1 is located within a large CpG island, and the DNA methylation level in the GAD1 promoter regulates GAD1 expression in brain18. The methylation level around the GAD1 promoter is regulated by a DNA methyltransferase I (DNMT1) in GABAergic interneurons, and most importantly, it is inversely associated with decreased GAD1 mRNA expression in human prefrontal cortex19,20. DNMT inhibitors can induce the expression of GAD67 in a dose- and time-dependent manners, and this activation correlated with a reduction in DNMT activity and DNA methyltransferase 1 protein level18. A previous postmortem study of the hippocampus in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder revealed DNA methylation changes in a set of GAD1 regulatory network genes, including histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) and death-associated protein 6 (DAXX)21, which are co-repressors associated with epigenetic regulation of the expression of GAD67 in the hippocampal circuit22,23.

During embryonic development in the rodent, alternative splicing takes place in GAD67 to produce two additional transcripts, composed of either the first 80 or 86bp of two almost identical alternative spliced exons (7A and 7B) inserted between the exon 6 and exon 7 of the full-length GAD1 transcript24,25. For the 80bp insert, an overlapping stop/start codon (TGATG) converts the main open reading frame into two overlapping open reading frames, one encoding for an enzymatically inactive 25-kDa protein (GAD25) and the other for the enzymatically active 44-kDa (GAD44) protein. At the end of the 86-bp insert, an additional stop codon terminates the translation of GAD444,25,26. These two truncated transcripts are highly expressed during fetal development, with a rapid decline in expression after birth. GAD25 may play a role in neuronal proliferation and migration, as well as synaptogenesis27, while the role of GAD44 in development is still unknown. A missense mutation located at the N-terminus of GAD1 has been found in a family with an autosomal recessive spastic form of cerebral palsy28. This mutation leads to an amino acid change in GAD67 and GAD25. The role of regulation of these embryonic splice variants in brain development and the possibility abnormal expression might lead to neurodevelopmental disorders such as schizophrenia is unknown.

Our previous work has found that rs3749034, a GAD1 promoter SNP, was associated with schizophrenia risk15, and additional studies have demonstrated the importance of alternative transcripts from the GAD1 gene in early brain development and schizophrenia29. The full characterization of the GAD1 transcriptome has not been completed in human brain, and it is still unclear how a genetic variant in the GAD1 promoter might lead to increased risk for schizophrenia. The aim of this study is to identify alternative transcripts of GAD1 that and their expression patterns in the developing PFC, and to identify the transcript and DNA methylation site associated with the genetic risk variant located near the GAD1 promoter.

Materials and Methods

Human postmortem brain tissue collection, tissue retrieval and RNA extraction

Postmortem neonate, infant, child, adolescent and adult brains were collected at the Clinical Brain Disorders Branch (CBDB), National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) through the Northern Virginia and District of Columbia Medical Examiners’ Office. Informed consent to study brain tissue was obtained from the legal next of kin for all cases, according to NIMH Protocol 90-M-0142 and processed approved by the NIMH/National Institutes of Health Institutional Review Board. Additional fetal, child and adolescent brain tissue samples were provided by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Brain and Tissue Bank for Developmental Disorders under contracts N01-HD-4–3368 and NO1-HD-4_3383, approved by institutional review board of the University of Maryland at Baltimore and the State of Maryland, and the tissue was donated to the NIMH under the terms of a material transfer agreement. All samples were obtained with audio-taped informed consent from the legal next of kin to study brain tissue, as approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institutes of Health and University of Maryland, in lieu of a written consent form. Brains were hemisected, and cut into 1.0–1.5-cm-thick coronal slabs, flash frozen, and stored at −80°C. DLPFC gray matter was dissected using a dental drill. For non-fetal cases, the DLPFC (Brodmann’s areas 9 and 46) was dissected from the middle frontal gyrus of the coronal slab, immediately anterior to the genu of the corpus callosum. For fetal cases, the PFC was obtained from the frontal cortex dissected at the dorsal convexity, midway between the frontal pole and anterior temporal pole.

Dissected tissue was pulverized and stored at −80°C. Pulverized cerebellum was used to measure the pH. Total RNA from postmortem DLPFC tissue was extracted from 100mg of pulverized tissue with RNeasy Lipid Tissue Mini Kit (QIAGEN). The RNA was purified with RNeasy Mini Spin columns plus on-column DNase digestion by RNase-free DNase Set (QIAGEN). The yield of total RNA was determined by Qubit RNA BR Assay Kit and Qubit Fluorometer (ThermoFisher Scientific). The RNA quality was assessed with high-resolution capillary electrophoresis on an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies). Approximately 300ng total RNA was applied to an RNA 6000 Nano LabChip without prior heating. An RNA integrity number (RIN), obtained from the entire Agilent electrophoretic trace with the RIN software algorithm, was used for the assessment of RNA quality.

We have assessed the expression of GAD1 alternative transcripts in three postmortem cohorts in this study (Supplementary Table 1, 2, 3). The DLPFC cohort included 181 schizophrenia patients, 69 bipolar disorder patients, 146 major depressive disorder (MDD), and 340 non-neurological and non-psychiatric controls. The hippocampus cohort was composed of 128 schizophrenia patients and 295 non-neurological and non-psychiatric controls. A subset of non-psychiatric non-neurological controls, spanning from gestational weeks 14 to 20 and from birth up to 85 years of age, were used to measure expression of selected GAD1 transcripts in the prefrontal cortex. Toxicological analysis was performed on all samples. Positive toxicology was exclusionary for control subjects but not for patients with psychiatric disorders. The majority of positive toxicology reports in psychiatric cases were due to the presence of psychotropic medications. In a subset of psychiatric cases, toxicology studies also revealed the presence of a variety of illicit substances. Nonpsychiatric controls were excluded if toxicology was positive for psychotropic medications or illicit substances.

Poly-A RNA Sequencing and GAD1 expression quantification

Poly-A-containing RNA was purified from 1ug DNAse treated total RNA. After purification, mRNA molecules were fragmented into small pieces using divalent cations under elevated temperatures. Reverse transcriptase and random hexamers were used to convert the cleaved RNA fragments into first strand cDNA. Second strand cDNA was synthesized using DNA Polymerase I and RNaseH. These cDNA fragments were then subjected to an end repair process using T4 DNA polymerase, T4 polynucleotide kinase (PNK) and Klenow DNA polymerase, the addition of a single ‘A’ base using Klenow Exo (3’ to 5’ exon minus), and then ligation of the Illumina P adapters using T4 DNA Ligase. An index (up to 12) was inserted into Illumina adapters so that multiple samples could be sequenced in one lane of an 8-lane flow cell if necessary. These products were then purified and enriched by PCR to create the final cDNA library for high-throughput DNA sequencing using the HiSeq 2000 (Illumina, Inc.). The Illumina Real Time Analysis (RTA) module was used for image analysis and base calling, followed by the use of a BCL Converter (CASAVA v1.8.2) to generate FASTQ files containing sequence reads. Pair-end 100 bp reads of cDNA sequences obtained by the Hi-Seq 2000 were aligned to the human genome reference (UCSC hg19) by splice-read mapper (TopHat v2.0.4), providing known transcripts from Ensembl Build GRCh37.67.

To measure the mRNA expression of GAD1 transcripts, we acquired the mapped reads covering the GAD1 genomic region, corresponding to chr2:171,658,206–171,748,200 on genome build GRCh37/hg19. Reads mapping to the unique junction for each transcript were used to quantify GAD1 transcripts similar to previous approaches30. RPM (reads per million mapped reads in the targeted GAD1 locus) has been calculated to quantify junction-level expression.

End-to-End PCR

Based on known GAD1 gene exons and RNA sequencing results, we designed primer pairs to amplify the full length of GAD1 transcripts using Platinum TaqDNA polymerase (Invitrogen). The PCR conditions were 94°C for 3 minutes, 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 60°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 1–5 minute, and 72°C for 10 minutes after the last cycle. End-toend PCR products were cloned into E. Coli by PCR-TOPO 4.0 vectors (Invitrogen) and sequenced. All PCR results were confirmed by separate PCR assays and Sanger sequencing.

Quantification of GAD1 transcripts by RNA sequencing and real-time PCR

Using SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) to synthesize cDNA, 4μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed in a 50μl reaction system. mRNA expression levels of alternative GAD1 transcripts were measured in postmortem DLPFC samples from 89 non-psychiatric non-neurological control subjects by real-time quantitative PCR (RT-PCR), using ABI Prism 7900 sequence detection system with the 384-well format. Customized TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) were used for the four GAD1 transcripts (I80, I86, 8A, and 8B) by spanning their unique junctions (Supplementary Table 7). mRNA expression levels of four GAD1 alternative transcripts were normalized to geometric means of three constitutively-expressed genes: β-actin (ACTB), β2-microglobulin (B2M) and β-glucuronidase (GUSB).

DNA extraction, SNP genotyping and methylation

Genomic DNA was extracted from 100mg of pulverized cerebellar tissue and DLPFC tissue with the phenol-chloroform method. SNP genotyping with HumanHap650Y_V3 or Human 1M-Duo_V3 BeadChips (Illumina, San Diego, CA) was carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions with DNA extracted from cerebellar tissue. The methylation and genotype data for the GAD1 gene were extracted from a larger data set from one of our recent studies31. In brief, methylation of DNA extracted from DLPFC was assessed according to the manufacturer’s instruction using the Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip Kit (Illumina), which measures DNA methylation of more than 485,000 CpG dinucleotides (cg) covering 99% RefSeq gene promoters, including the GAD1 gene. The methylation data were processed and normalized using the minfi Bioconductor package in R32 as previous described31.

Expression GAD1 transcripts in HEK293 cells

GAD1 transcripts encoding GAD67, GAD25, GAD44, 8A and 8B cDNA were cloned into a pCR4-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) using a specific primer and high-fidelity DNA polymerase and then subcloned into a pCMV6-Entry vector, which contains a C-terminus Myc-DDK tag to make C-Myc-DDK fusion constructs. All cDNA clones were verified by Sanger sequencing to avoid de novo mutations. HEK293 cells were cultured in DMEM medium (Gibico) with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine and 1% penicillin-streptomycin in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. The plasmids containing each GAD1 fusion construct were all accurately quantified by Qubit Fluorometer (ThermoFisher Scientific) and transfected HEK293 cell by using FuGENE HD transfection Reagent (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 48 hours, transfected cells were harvested, washed with cold PBS and subjected to protein extraction.

Western Blotting

Cold PBS-washed cells were lysed by Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent (M-PER, Thermo Scientific). The homogenates were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatants were collected and protein concentrations were measured by Qubit Fluorometer. Twenty micrograms of each protein sample plus loading dye were boiled for 5 min and resolved on NuPage 12% Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen). Gels were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Invitrogen) and then blocked by Odyssey Blocking Buffer (LI-COR Biosciences) overnight at 4 °C. Antibodies (Calbiochem, Cat#OP10) were diluted in Odyssey blocking buffer at an appropriate concentration and incubated overnight at 4 °C with medium agitation. Blots were washed three times with PBST (0.2% Tween-20) for 10 min and then incubated with IRDye secondary antibody (LI-COR Biosciences, Cat#827–11080) in Odyssey blocking buffer plus 0.5% Tween 20 and incubated with gentle shaking for 1 h (protected from light), and the blots were scanned on an Odyssey imaging system.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the R package (Version3.2.2). The expression measurements were log2 transformed to make the data more symmetrical for ANCOVA/linear modeling. The lifespan curve was generated using LOESS fit (local polynomial regression fitting) by using an R package with default parameters. Multiple regression analyses were carried out to evaluate the contributions of age, pH, postmortem interval (PMI), race, sex and RNA integrity number (RIN), ethanol exposure and nicotine exposure on mRNA expression or DNA methylation levels. Multiple regression analyses were also performed to assess the effect of completed suicide, psychotropic medications (toxicology screen results about antidepressants, antipsychotics, anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines, and opiates), lifetime neuroleptic exposure, average daily neuroleptic dose, final neuroleptic dose, and illicit substances on mRNA expression or DNA methylation levels in the patients with psychiatric disorders. Estimated of lifetime neuroleptic exposure, average daily dose, and final neuroleptic dose were all converted to chlorpromazine equivalents for statistical comparisons. Levene’s test showed that the assumption of homogeneity of variance was met. Comparisons between diagnostic groups were made by ANCOVA for mRNA expression or DNA methylation levels with diagnosis as an independent variable. Covariates were chosen for each ANCOVA from multiple regression analyses. Comparisons between patients and controls following overall ANCOVA were conducted by post-hoc Tukey HSD tests. Comparisons within the different diagnostic groups for completed suicide, nicotine exposure, ethanol exposure and psychotropic medications were conducted by ANCOVA, followed by Bonferroni correction.

Results

Alternative transcripts of GAD1 in human brain

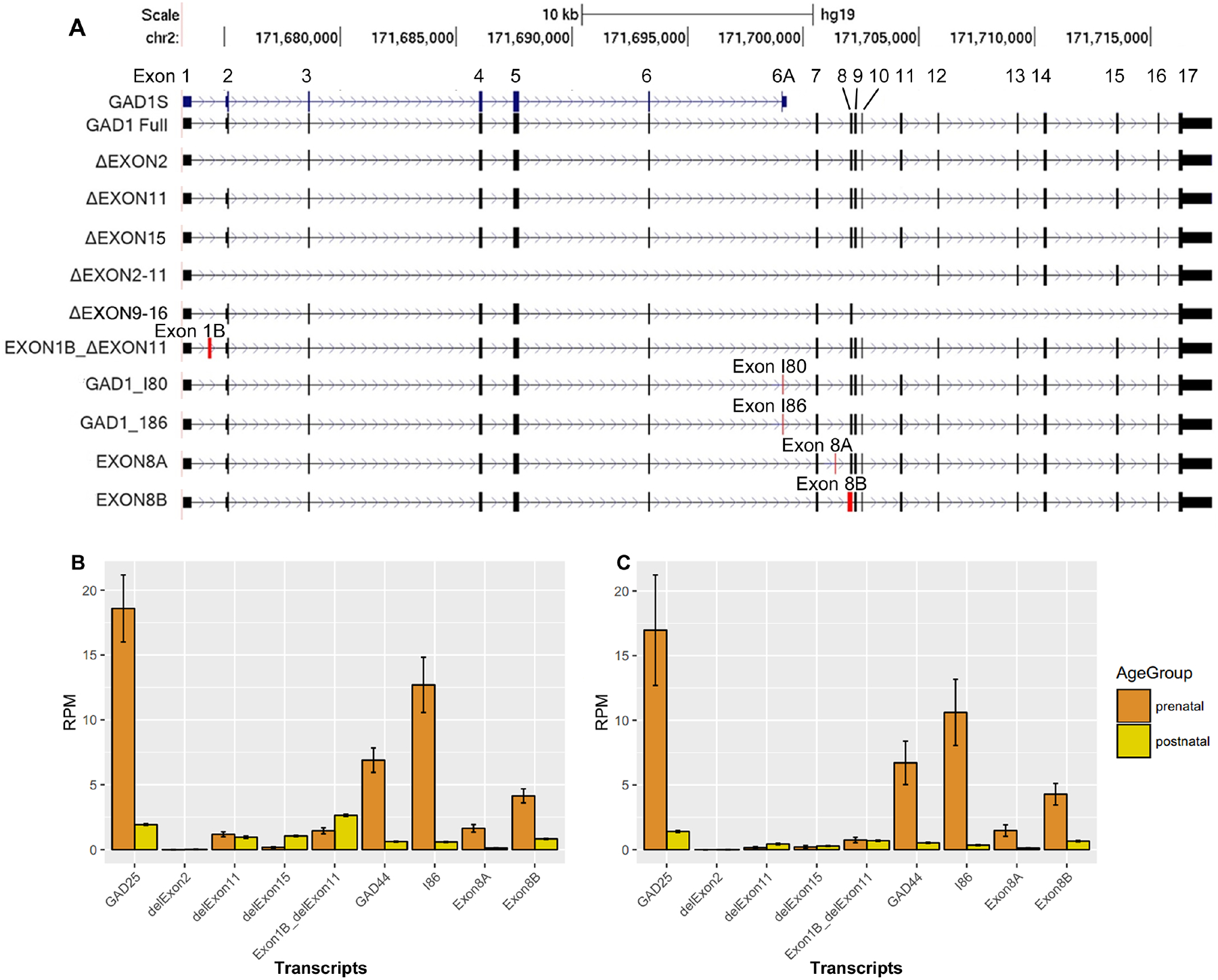

RNA seq revealed that while reads aligned to previously annotated RefSeq exons, sequence also mapped to previously unannotated exons and alternative transcripts in fetal and adult human brain tissue. Whereas these novel expression peaks were found in both fetal and adult tissue, RNA sequencing junction maps suggested the splicing events of GAD1 are different between the fetus and the adult. The exon skipping mainly occurs in adults, and splicing junctions indicating novel exons are mainly occurring in fetal brain. Further PCR and molecular cloning experiments have confirmed at least 5 transcripts due to exon skipping, including skipping of exon 2, exon 11, exon 15, exons 9–16, or exon 2–11. In addition to these exon-skipping events, for GAD1 we also identified 3 new exons: exon 1B, 8A, and 8B. Additionally, we have also identified embryonically expressed exons in the human brain: I80 and I86, which have previously been identified only in the rodent brain. Finally, by the end to end PCR, we have observed 8 novel GAD1 transcripts and confirmed the existence of transcripts GAD1-I80 and GAD1-I86 in the human brain (Figure 1A, Supplementary Table 4).

Figure 1. Identification and mRNA expression of alternative transcripts of GAD1 in human brain.

A: Alternative transcripts of GAD1 in human brain. We have observed five exotic deletions and 3 novel exons in both adult and fetal human brain. We have also observed the expression of the two embryonic exons in human brain: I80 and I86, previously discovered in rodent brain. In total, we have identified 8 novel GAD1 transcripts in human brain and confirmed the existence of transcripts GAD1-I80 and GAD1-I86 in human brain. Red rectangles, new exons; black rectangles; known exon. Stars mark the 4 embryonic transcripts measured with real-time quantitative PCR. Exon deletion is indicated by Δ; for example, ΔEXON2 means deletion of exon2. Transcripts with a new exon were represented by its former exon name plus a letter. For example, EXON8A means a transcripts containing a new exon between original exon 8 and exon 9. Novel alternative exons have been highlighted by red color. B: mRNA expression of GAD1 transcripts in human DLPFC. C: mRNA expression of GAD1 transcripts in human Hippocampus. We have measure the average expression of GAD1 transcript in the DLPFC and Hippocampus of control subjects by using the RNA sequencing data and unique junctions of each transcript. The expression of the transcripts with novel deletion have been measured by the reads spanning the junction of the deletion. The expression of the transcript with novel exons have been measured by the reading spanning the junction between the novel exon and nearby exon. Since the I80 encodes the GAD25 and GAD44, so the expression of I80 can reflect the expression of GAD44. Since the GAD25 was encodes by I80 and I86, which sharing the same unique junction from exon 6 to I80 or I86, we have used the sharing unique junction of I80 and I86 to represent the expression level of GAD25. We didn’t show the expression level of the full length GAD1 transcript, encoding GAD67, in this two plots. It is because it expression level is too high in postnatal stage to be showed properly with other transcripts together in the same plot. The rare GAD1 transcripts such as ΔEXON2–11 and ΔEXON 9–16 were also not plotted since they are rare.

Among all the transcripts produced by GAD1, the previously identified full-length transcript encoding GAD67 showed the highest frequency in our clones. Transcripts containing exon I80, I86, 8A or 8B were also relatively common in clones derived from fetal cDNA. We have quantified each transcript in the RNA sequencing data generated from control subjects by their unique splicing junctions. The full-length transcript, which encodes GAD67, was most abundant in adult human PFC (Figure 1B) and hippocampus (Figure 1C). In fetal PFC and hippocampus, the full-length transcript also was relatively most abundant, with I80, I86, 8A, and 8B the most abundant of the alternative transcripts (Figure 1B, 1C). The alternative transcripts containing exon skipping are low abundance especially skipping of exon 2, exons 2–11 or exons 9–16, which are rare in both human PFC and hippocampus.

Similar to the lifespan pattern of the truncated transcript GAD25 (Hyde et al., 2011), the expression of GAD1-I80, GAD1-I86, GAD1-8A, and GAD1-8B, were relatively high during the second trimester fetal period, followed by decreased expression after birth (Supplementary Figure 1). These lifespan patterns were the inverse of the expression pattern of the full-length transcript GAD67 (Hyde et al., 2011), whose expression was low in the fetal period, increased steadily up to around 20 years of age, and then remained highly expressed throughout adulthood.

Expression of proteins in transfected HEK293 cells

Since the majority of GAD1 transcripts encode GAD67, GAD25, GAD44, 8A or 8B in human DLPFC and hippocampus (Figure 1B, 1C), we focused on the related 5 transcripts for protein expression. Previous studies on rodents have suggested the alternative exon I80 contains an overlapped stop-start codon, and as a result, encodes both GAD25 and GAD44. On the other hand, the alternative transcript exon I86 has an extra 6bp insertion that produces a premature stop codon. As a result, the alternative transcript I86 encodes GAD25 only. Bioinformatics analyses have suggested that the alternative transcripts 8A and 8B also have a premature stop codon (TAA) because of a novel exon insertion. Accordingly, 8A and 8B should generate 29.82 kDa and 28.17 kDa truncated proteins respectively. In our experiments, HEK293 cells were transfected with a Myc-fusion construct containing either GAD67, GAD25, GAD44, 8A, or 8B. By western blotting with an anti-Myc antibody, we observed protein translated from all five selected transcripts. As predicted, the ascending order of their molecular weights is GAD25, 8B, 8A, GAD44 and GAD67 (Supplementary Figure 2).

mRNA expression of GAD1 transcripts in schizophrenia and affective disorders

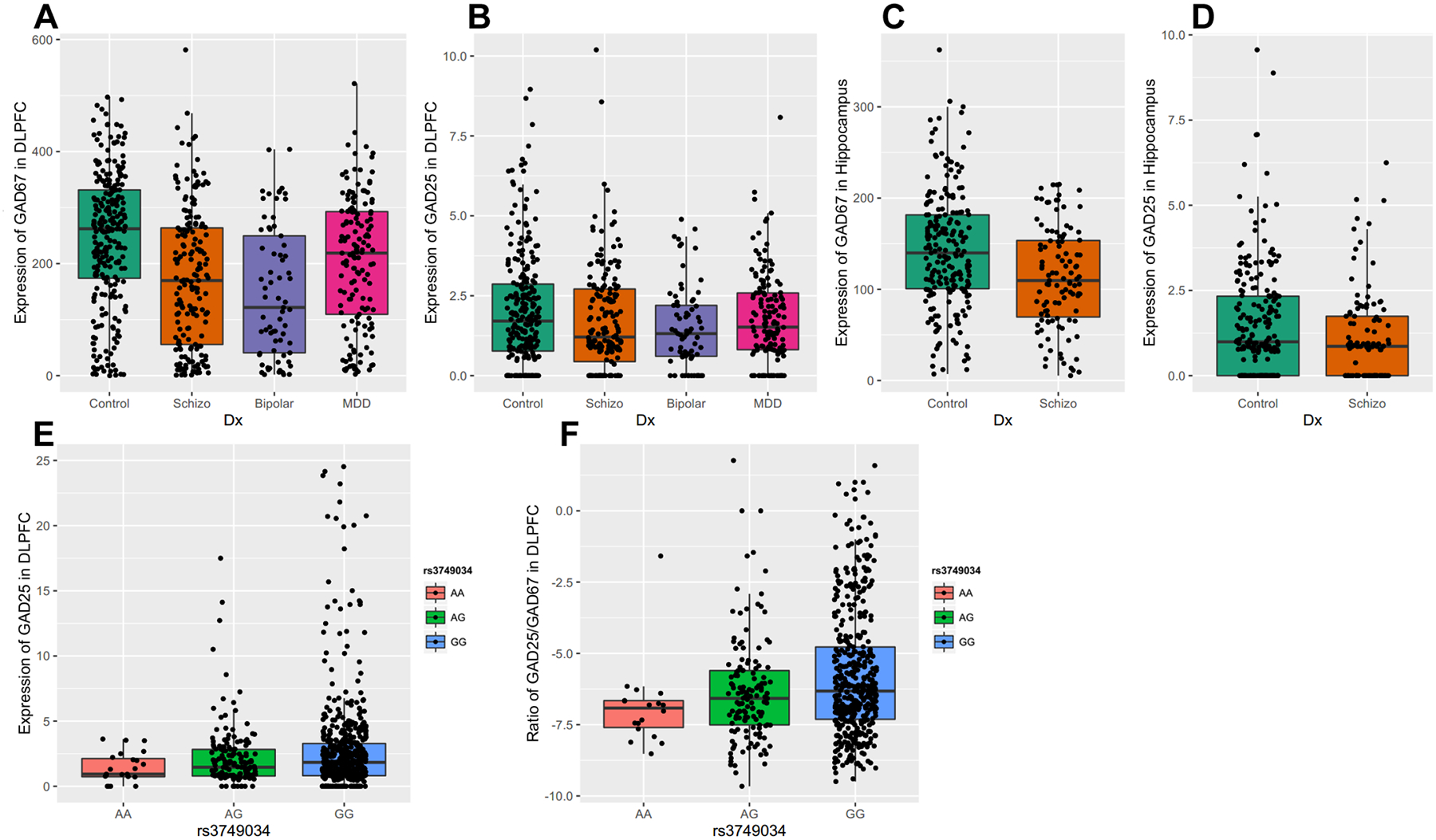

Compared to the full-length GAD1 transcript, which encodes GAD67, the alternative GAD1 transcripts are expressed at very low level in adult DLPFC and hippocampus. By ANCOVA, the expression of the full-length GAD1 transcript showed an overall effect of diagnosis in DLPFC (F(3, 622) = 27.2, p=1.51E-16). Tukey HSD post hoc analyses revealed that the full-length GAD1 transcript was significantly decreased in DLPFC of patients with schizophrenia (p = 2.08E-10), bipolar disorder (p = 2.81E-10) and major depression (p = 1.20E-03) (Figure 2A). In the hippocampus, the expression of full-length GAD1 transcript was significantly down-regulated in the patients with schizophrenia (F(1, 297) = 17.1, p = 4.59E-05) (Figure 2C). There was no effect of diagnosis on the expression of transcripts encoding for GAD25 in DLPFC (Figure 2B) and hippocampus (Figure 2D). There was no significant association between the expression of the full-length GAD1 transcript and the schizophrenia risk SNP rs3749034, but this SNP was significantly associated with the expression of GAD25 (F(2, 596) = 4.9, p = 8.00E-03) and the GAD25/GAD67 ratio in DLPFC (F(2, 558) = 8.1, p = 3.56E-04). The risk allele (G) was significantly associated with increased expression of GAD25 and increased GAD25/GAD67 ratio in an allelic dose-dependent manner in DLPFC (Figure 2E, 2F).

Figure 2. Expression of transcripts encoding GAD67 and GAD25 in human DLFPC and Hippocampus among different diagnostic groups.

The expression of each alternative transcript was studied across four cohorts of subjects (nonpsychiatric controls, schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, and bipolar disorder) in DLPFC and two cohorts of subjects in hippocampus (nonpsychiatric controls and schizophrenia). A: the expression of transcript encoding GAD67 in DLPFC; B: the expression of transcripts encoding GAD25 in DLPFC; C: the expression of transcript encoding GAD67 in Hippocampus; D: the expression of transcripts encoding GAD25 in Hippocampus. The x-axis shows the different diagnostic groups: Control, nonpsychiatric control group; Schizo, patients with schizophrenia; Bipolar, patients with bipolar disorder; MDD, the patient group with major depression. The y-axis represents the relative expression quantities in the DLPFC or Hippocampus. Each dot represents a subject. E: schizophrenia-associated GAD1 risk SNP rs3749034 and the expression of GAD25 in human DLPFC. F: schizophrenia-associated GAD1 risk SNP rs3749034 and ratio of GAD25/GAD67 in human DLPFC. The different genotypes are on the x-axis. The schizophrenia-associated risk genotype is G/G. The y-axis represents the expression of GAD25 in DLPFC or the ratio of the expression of transcript encoding GAD25 divided by the expression of the transcript encoding GAD67. Each dot represents a subject.

DNA methylation quantitative trait loci (mQTLs) for GAD1 in PFC and hippocampus

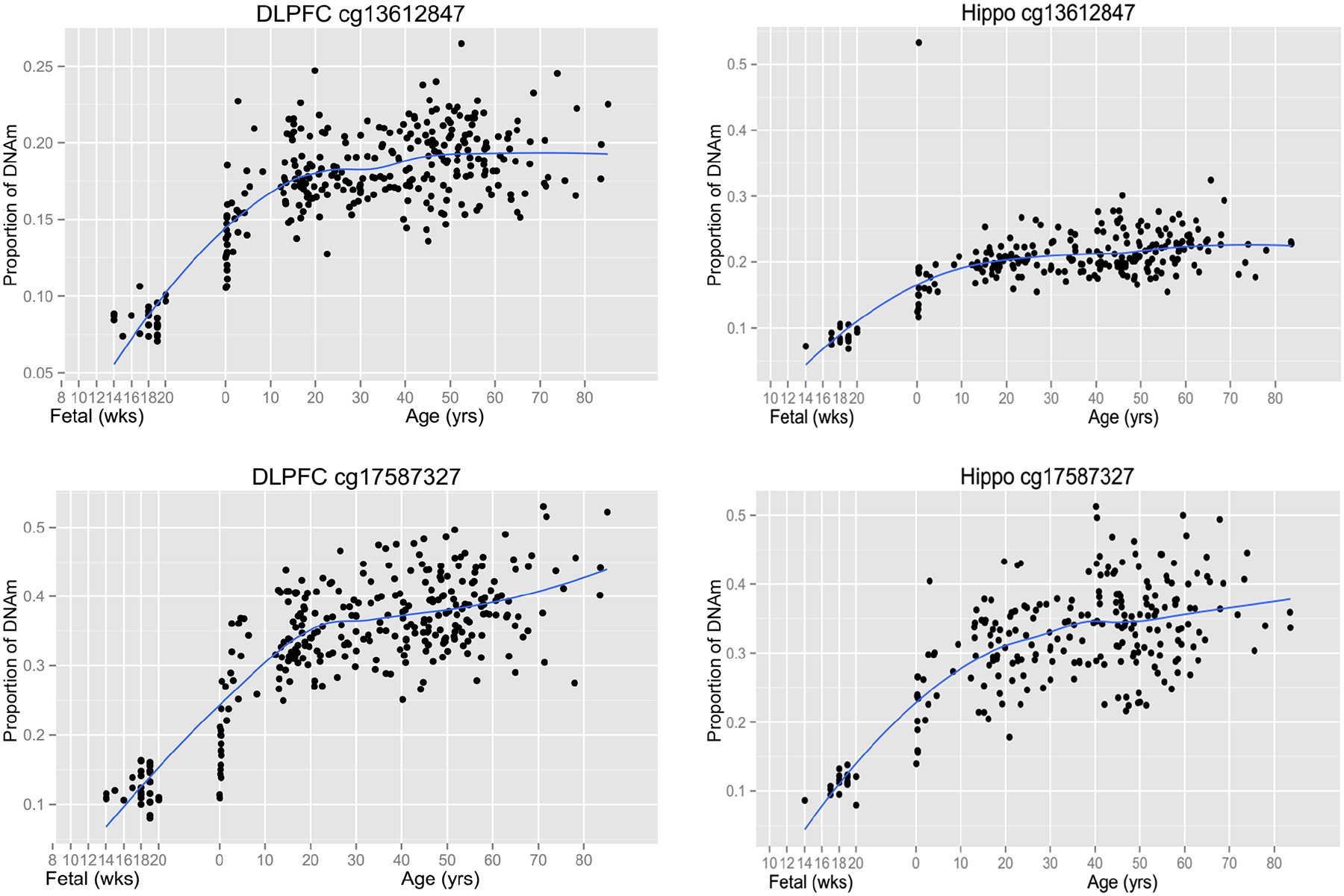

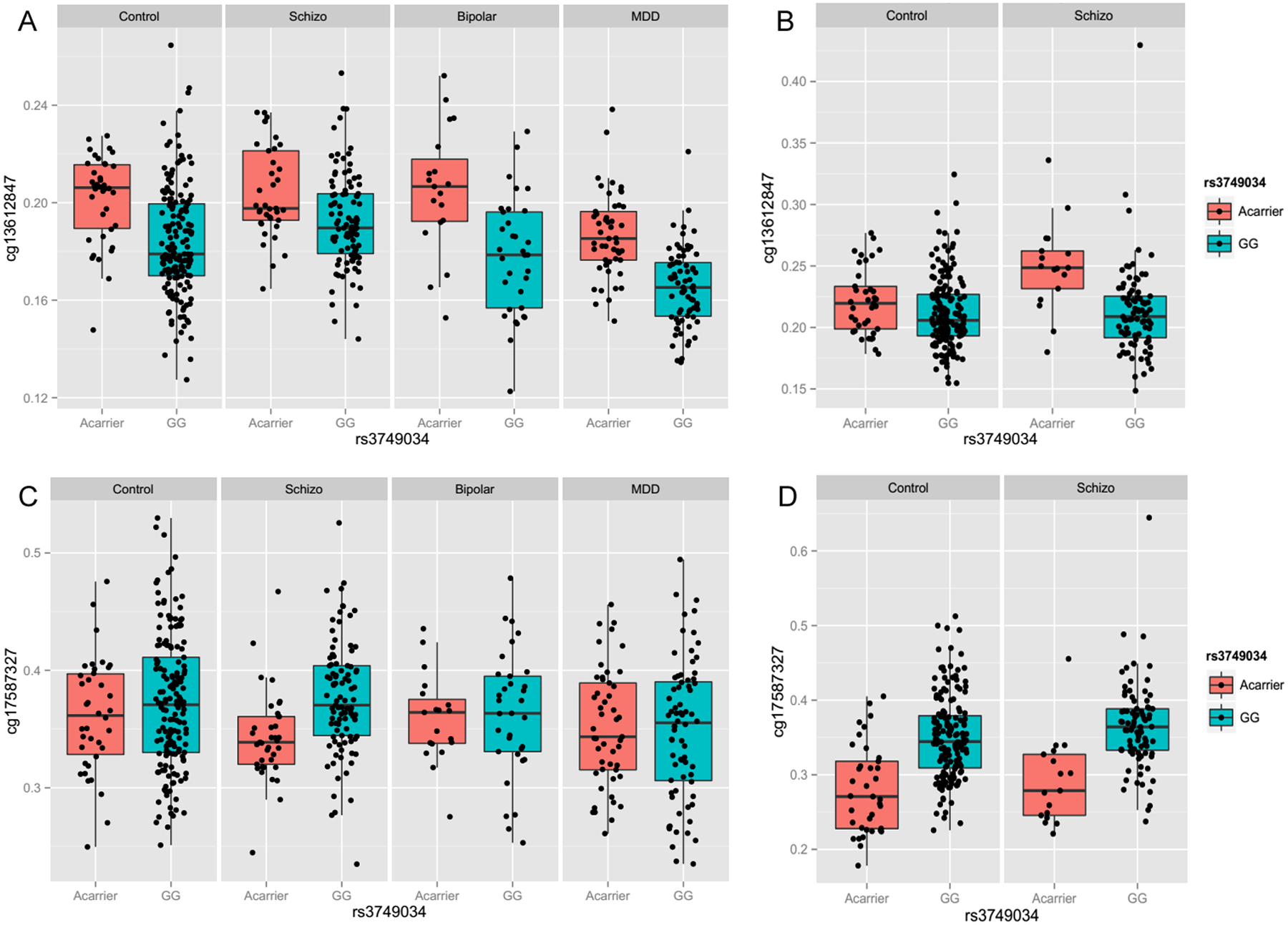

We analyzed DNA methylation levels at 48 GAD1 CpG loci in the DLPFC of control subjects, patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and MDD as well as in the hippocampus of control subjects and patients with schizophrenia. The GAD1 SNP rs3749034 was interrogated for association with DNA methylation levels. For the GAD1 gene, we found two significant mQTL loci for rs3749034, cg13612847, and cg17587327, in the PFC and hippocampus respectively. Both of these methylation loci were located within the 5’ non-transcriptional region of GAD1, but not in a CpG island. The methylation levels at these sites were low in the human PFC and hippocampus between gestational weeks 14–20, then increased and plateaued into adulthood (Figure 3). In control subjects, the schizophrenia-associated risk allele of rs3749034 (GG) was significantly associated with decreased methylation of cg13612847 in DLPFC and increased methylation of cg17587327 in the hippocampus (Figure 4A, 4D). The DNA methylation levels of both loci were inversely correlated with mRNA expression of GAD25 (p < E-19) and positively correlated with mRNA expression of GAD67 (p < E-05) in the DLPFC of control subjects (Supplementary Table 5). Our analyses also revealed negative correlations between the DNA methylation levels of both loci and the mRNA expression of GAD25 in the hippocampus (p<E-08), and a positive correlation between the methylation level at cg17587327 and expression of GAD67 mRNA in the hippocampus (p=1.60E-03) (Supplementary Table 5).

Figure 3. The lifespan trajectory of DNA methylation level at cg13612847 and cg17587327 loci in human DLPFC and Hippocampus.

Both CpG loci (cg) showed similar lifespan trajectory of DNA methylation level in human DLPFC and Hippocampus. Their methylation level is low in fetal age, and rising during the brain development until about 20~30 years old. The x-axis before birth gestational age is in weeks (wks) and after birth the x-axis shifts to years (yrs). The y-axis represents proportion of DNA methylation level at CpG locus. Each black dot represents a subject. Blue curve indicates the best fit curve for lifetime expression.

Figure 4. Schizophrenia-associated GAD1 risk SNP rs3749034 is significantly associated with cg13612847 and cg17587327 in human DLPFC and Hippocampus respectively.

The methylation level of two CpG loci, cg13612847 and cg17587327, was evaluated with the schizophrenia-associated GAD1 risk SNP rs3749034 across four cohorts of subjects (nonpsychiatric controls, schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, and bipolar disorder) in DLPFC and two cohorts of subjects in hippocampus (nonpsychiatric controls and schizophrenia). A: The methylation level of cg13612847 was significantly associated with rs3749034 in human DLPFC of the four cohorts of subjects; B: The methylation level of cg13612847 was significantly associated with rs3749034 in human Hippocampus of patients with schizophrenia; C: The methylation level of cg17587327 was significantly associated with rs3749034 in human DLPFC of patients with schizophrenia; D: The methylation level of cg17587327 was significantly associated with rs3749034 in human Hippocampus of control subjects and patients with schizophrenia. The different genotype is on the x-axis. The y-axis represents the proportion of DNA methylation of cg13612847 or cg17587327. Each black dot represents a subject. The different diagnostic groups were labeled on the head of each plot: Control, nonpsychiatric control group; Schizo, patients with schizophrenia; Bipolar, patients with bipolar disorder; MDD, the patient group with major depression.

In the DLPFC, rs3749034 was significantly associated with the methylation level of cg13612847 in control subjects (F(1, 303) = 24.3, p = 1.35E-06), patients with schizophrenia (F(1, 169) = 19.5, p = 1.76E-05), bipolar disorder (F(1, 57) = 24.2, p = 7.63E-06), and MDD (F(1, 135) = 48.1, p = 1.51E-10), as the risk allele predicted decreased methylation level of cg13612847 (Figure 4A). The methylation level of cg17587327 was only significantly associated with rs3749034 in the patients with schizophrenia (F(1, 169) = 16.7, p = 6.60E-05), but not in the DLPFC of control subjects, patients with bipolar disorder or MDD (Figure 4C).

On the other hand, in the hippocampus, the rs3749034 was significantly associated with the methylation level of cg13612847 only in patients with schizophrenia (F(1, 97) = 16.0, p = 1.22E-04), but not in control subjects (Figure 4B). Additionally, the methylation level of cg17587327 was significantly associated with rs3749034 in both control subjects (F(1, 236) = 17.9, p = 3.31E-05) and patients with schizophrenia (F(1, 97) = 29.1, p = 4.9E-07), as the schizophrenia-associated risk allele predicted increased methylation of cg17587327 in the hippocampus (Figure 4D).

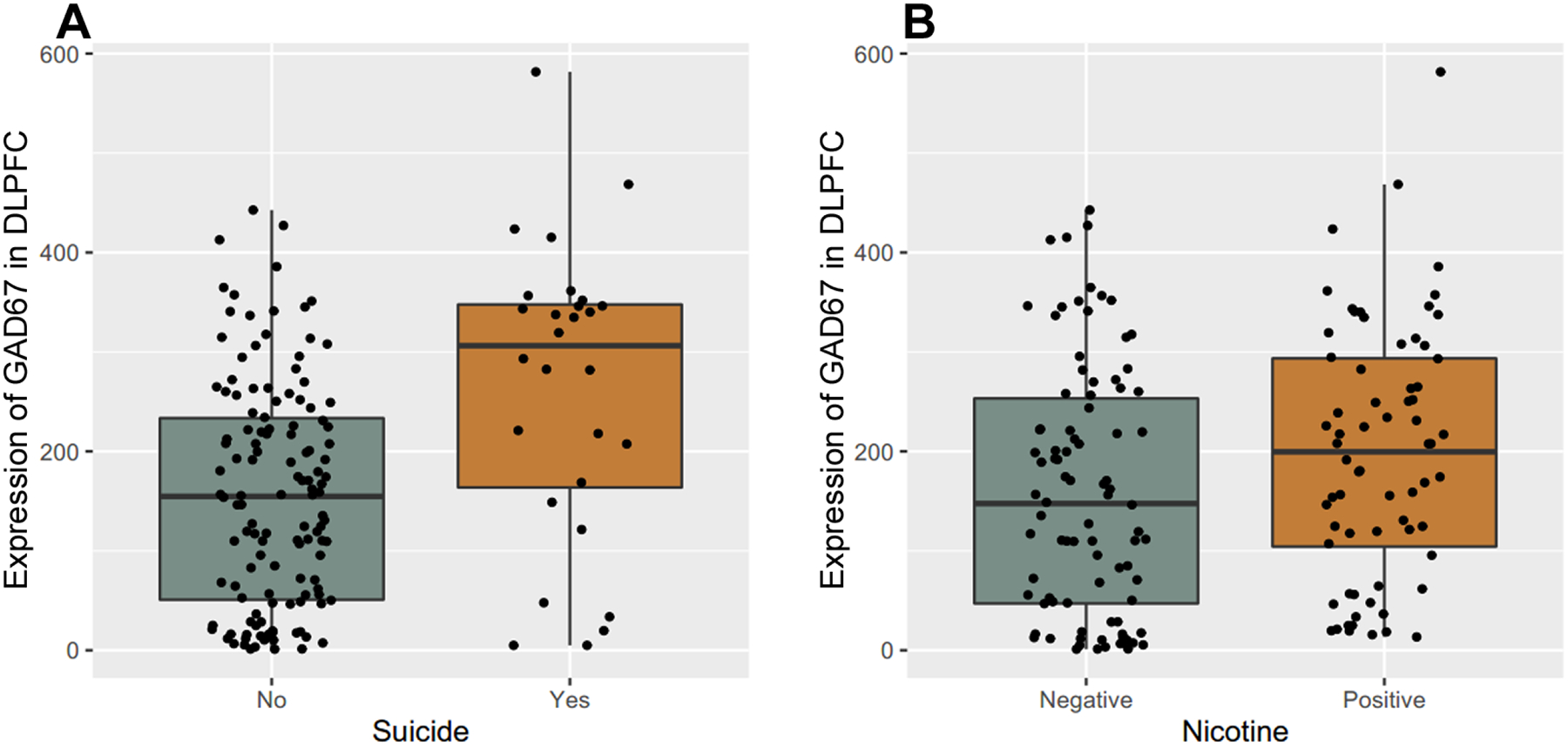

Expression of GAD1 full-length transcript with nicotine exposure and suicide

Toxicology screens from blood samples taken at the time of autopsy provided results for a large number of substances including nicotine, ethanol, opiates, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, and antipsychotics. The clinical and medical examiner records provided basic demographic information plus lifetime neuroleptic exposure, average daily dose, final neuroleptic dose, and suicide. In the DLPFC cohort, 43.4 % of psychiatric patients (61.7% in MDD, 65.2% in bipolar disorder, and 19.9% in schizophrenia) died from completed suicide. Nicotine exposure was positive in 41.8% patients with psychiatric disorders (43% in schizophrenia, 42.6% in bipolar disorder and 38.7% in MDD) and 25.4% controls. Those subjects with schizophrenia who died via completed suicide (F(1, 167) = 28.8, p = 2.69E-07) (Figure 5A) or subjects with schizophrenia and positive nicotine toxicology (F(1, 148) = 7.9, p = 5.58E-03) (Figure 5B) showed significantly higher expression of GAD1 full length transcript in the DLPFC compared with schizophrenia subjects who died via natural causes or nicotine-free patients with schizophrenia, respectively. The expression of the other GAD1 transcripts in PFC were not associated with completed suicide and/or nicotine exposure. In the hippocampus cohort, there was no significant association between the expression of GAD1 transcripts and completed suicide or nicotine exposure. There was no significant effect of psychotropic medications on the expression of GAD1 transcripts in the DLPFC and hippocampus.

Figure 5. Expression of GAD67 mRNA correlated with suicide and nicotine exposure in human DLPFC.

The y-axis represents the expression of GAD1 full length transcript encoding GAD67 in DLPFC of patients with schizophrenia. Each black dot represents a subject. A: GAD67 mRNA expression in DLPFC between completed suicide and death by natural causes in schizophrenia patients. The x-axis represents the schizophrenia patients with or without completed suicide. B: GAD67 mRNA expression in DLPFC between nicotine positive and nicotine free schizophrenia patients on toxicology testing. The x-axis represents the schizophrenia patients with or without nicotine exposure based on toxicology testing. “Schizo” represents patients with schizophrenia.

Discussion

Alternative splicing of transcripts is a common feature of gene expression in the central nervous system. Our results revealed multiple novel transcripts for GAD1 in the human brain derived from new exons and/or exon skipping. Extending the previous observation in embryonic rodent brain24,25,27, we have discovered the presence of the transcripts with the 80 or 86 base alternative exons in the human brain, and their developmental trajectory of expression. We have also found two additional novel exons, exon 8A, and 8B, located between the exon 7 and exon 8 of the full-length transcript. The transcripts with exon 8A or 8B encode two truncated GAD isoforms because of a premature stop codon. These 4 alternative exons (I80, I86, 8A, and 8B) are exclusive, and result in 4 alternative transcripts, all of which share a similar lifespan expression pattern in the human brain. They are highly expressed during the second trimester fetal period in the human brain, followed by a rapidly decreasing level of expression after birth, and are rarely expressed in the adult brain. This pattern is opposite to the lifespan expression of the full-length GAD1 transcript, encoding GAD67, the glutamate decarboxylase responsible for the majority of GABA synthesis in CNS. Besides these four embryonic exons, we have discovered another novel exon between exon 1 and exon 2, plus five transcripts produced from different exon skipping events. Though the full-length GAD1 transcript, GAD67, appears to be the most abundant transcript in human PFC and hippocampus across the different life stages, the time course of expression of the alternative GAD1 transcripts suggests that most of splicing events for the GAD1 gene occur during the fetal stages of brain development.

Though two truncated GAD1 isoforms, GAD25 and GAD44, were discovered many years ago33, their function remains unknown. In silico analysis suggests that GAD25 yields an enzymatically inactive form of GAD lacking a catalytic domain, while GAD44 should produce an enzymatically active peptide. These two truncated GAD1 isoforms are expressed widely in fetal mouse brain, but are barely detectable in the adult excepting the olfactory blub27,34. Interestingly, their expression in the olfactory bulb is modulated by estrogen in adult rat35. Overall, the olfactory bulb showed the highest expression of GAD1 transcripts in rodent brain27,34. The olfactory bulb is one of the few structures in the adult mammalian brain that is neurogenically active. Since alternative GAD1 transcripts, especially GAD25, are relatively abundant in areas associated with neurogenesis and high synaptic plasticity, their functional roles are most likely related to neurogenesis and synaptogenesis. Interestingly, GAD25 is also expressed in several non-neural human tissues, including pancreatic islets, testis, and adrenal cortex. Instead of the I80 or I86 exon insertion between exon 6 and exon 7, the alternative transcript for GAD25 in those non-neuronal tissues is truncated, having only seven exons. In the non-neural tissues, exon 7 has a shared the sequence with both I80 and I86, and includes a polyadenylation signal33. Therefore, while GAD44 might be only expressed and functional during the early brain development, GAD25 is not only critical during early brain development but also plays a role in human endocrine function during adult life, and in testicular function as well. Additional studies are needed to confirm that each of these four alternative transcripts produce four truncated GAD-related proteins, including GAD25 and GAD44 in the human brain. Functional studies are also needed to define their potential role in early brain development.

Dysfunction in the GABAergic system has been implicated in neurodevelopmental psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, with a decrease in GAD67 in prefrontal cortex being a consistent finding10–13. In this study, we found that GAD67 expression decreased in schizophrenia patients in both DLPFC and hippocampus, but the GAD25 splice variant mRNA did not differ between controls and patients in these two brain regions. Interestingly, we also report similar decreases in GAD1 expression in patients with bipolar disorder and major depression, suggesting the non-specificity of this finding in psychiatric illness. Previously, we reported that the schizophrenia-associated risk genotype in GAD1, at rs3749034, is significantly associated with the expression of GAD25 and the ratio of GAD25/GAD67 expression in hippocampus; those subjects with risk associated G/G genotype had higher expression of GAD25 and a larger GAD25/GAD67 ratio compared with minor allele carriers29. In this study, we have observed consistent results in a different cohort, finding that control subjects and patients with schizophrenia carrying the schizophrenia-associated risk genotype at rs3749034 have significantly increased expression of GAD25 and a higher GAD25/GAD67 ratio in the hippocampus. Unlike the previous study, we also found that the schizophrenia-associated risk allele at rs3749034 was significantly associated with the expression of GAD25 and the GAD25/GAD67 ratio in DLPFC too. This discrepancy between our two studies may be due to the larger cohort in this study, providing more statistical power to discover significant association signals.

There are other examples of pathological conditions in the adult brain associated with expression of embryonic GAD1 transcripts. In adult rat dentate granule cells after kainate-induced limbic seizures, there is a transient up-regulation of I86 expression, which is then followed by a moderate elevation of GAD67 mRNA36. Similarly, adult subjects with schizophrenia bearing a risk-associated GAD1 SNP show elevated expression of fetally-predominant transcripts associated with GABA signaling. The GAD1 risk-associated SNP was associated with decreased GAD67, as well as with increased GAD25/GAD67 and NKCC1/KCC2 ratios in the hippocampus of schizophrenia patients (Hyde et al., 2011). The expression of NKCC1, which is a fetal-predominant cation cotransporter at GABA synapses, was up-regulated and the expression of KCC2, an adult-predominant cation cotransporter at GABA synapses, was down-regulated immediately after brain injury37,38. The protein expression of KCC2 was decreased in the DLPFC of patients with schizophrenia off of medication. The authors also found that anti-psychiatric medications appear to raise the level of KCC2 protein in the patients with schizophrenia39. Our RNA sequencing data indicates that the expression of NKCC1 and KCC2, especially KCC2, is strongly positively correlated with the expression of GAD67 mRNA in both the DLPFC and hippocampus (Supplementary Table 8). These findings suggest that genes in the GABA signaling pathway are dynamically co-regulated during normal brain development. In schizophrenia, a chronic condition unlike seizures or brain injury, there appears to be a persistent expression of transcripts normally expressed in high levels only during fetal development. Given the notion that abnormalities during neurodevelopment may cause schizophrenia40, the levels of GAD1 developmental variants may be significant.

Like most mammalian promoters, the putative promoter of GAD1 is GC rich. The transcriptional start site of GAD1 is located within a large CpG island that spans a region extending from upstream through the first exon41. In this study, the schizophrenia-associated risk genotype in GAD1, rs3749034, is significantly associated with the methylation status of CpG site cg13612847 in human PFC and cg17587327 in the human hippocampus. Those two CpG sites are located in CpG island “shores” near the putative promoter of GAD1. Their methylation status followed a similar life trajectory in the PFC and hippocampus. In normal development, their methylation level gradually increased until about 20 years of age. In silico analysis by TFBIND (http://tfbind.hgc.jp/) suggested these two methylation loci might be the binding sites for multiple transcription factors, including CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha and beta, E2F-myc activator, RFX1, AHR, GTF3A, RREB1, LIMO2, TP53, EGR1, EGR2, EGR4 and GC box elements (Supplementary Table 6). Considering both methylation sites are negatively correlated with the expression of GAD25 and positively correlated with the expression of GAD67, they may be involved in the developmental regulation of GAD1 transcriptome expression, especially the shift from GAD25 to GAD67 production. Our data also showed that a schizophrenia-associated risk genotype in GAD1, at rs3749034, impacts the PFC and hippocampus through different methylation sites. Our results suggest that cg13612847 and cg17587327 have distinct methylation signatures in different brain regions during normal human brain development. Perhaps more importantly, alterations in their methylation status in both the DLPFC and hippocampus might contribute to the similar GAD1 expression changes in DLPFC and hippocampus of patients with schizophrenia.

Across diagnostic groups, many of the psychiatric patients involved in this study died through completed suicide. Consistent with our previous finding with GAD65, the expression of full-length GAD1 transcript encoding GAD67 was also significantly increased in the DLPFC of patients with schizophrenia who died through suicide. This result adds to the compendium of evidence of increased levels of GAD in the PFC of suicidal patients with schizophrenia42,43. Additional studies are needed to explore the role of high levels of GAD67 (and GAD65) in the prefrontal cortex in suicide, regarding pathogenesis and even possible therapeutic interventions.

Many subjects in this study also have a history of chronic nicotine exposure, confirmed by toxicology screen. Our data showed an up-regulated expression of GAD67 in the DLPFC of patients with schizophrenia who were positive for nicotine exposure. Smokers had a 2–4 times higher risk for suicide than non-smokers44. Daily smoking has been significantly associated with suicide attempts and self-mutilation in adolescent psychiatric patients, even after controlling for confounding factors such as psychiatric diagnosis45. Nicotinic cholinergic receptors in the hippocampus play a critical role in regulating the activity of GABA neurons, and decreased expression of several different nicotinic subunit isoforms in the hippocampus of patients with bipolar disorder might reflect a diminished influence of nicotinic receptor system on the GABA cells46. Our data showed that the expression of GAD67 was highest in the DLPFC of patients with schizophrenia who completed suicide and were positive for nicotine exposure. As expected, the non-suicide and negative nicotine exposure patients with schizophrenia had the lowest expression of GAD67 in DLPFC. Interestingly, we did not observe an association between the expression of GAD67 and/or suicide or nicotine exposure in the hippocampus. Our data suggest that regionally specific GABA dysfunction in the DLPFC might contribute to the increasing suicidality in chronic tobacco smokers, especially those with major psychiatric disorders.

In addition to neurons, GAD1 is also expressed in non-neural cell populations in the brain, such as glia47 and astrocytes48. Further, during the development of psychiatric disorders, there are often changes or shifts in gene expression between cell-types49. Our current study is unable to resolve the cell types expressing GAD1 mRNA isoforms and shifts in DNA methylation across development and in schizophrenia. Laser capture microdissection and nuclear sorting studies are needed to help resolve these questions.

Overall, we have characterized the transcriptome of GAD1 in human PFC and hippocampus in this study. Besides confirming previous findings of GAD67 and GAD25, we have reported two important methylation loci, both of which reside within the CpG island shores of the putative GAD1 promoter. The methylation status of these two sites was significantly associated with allelic variation at the schizophrenia-risk GAD1 promoter SNP rs3749034 in the human PFC and hippocampus. Since the methylation level of these two loci was significantly correlated with the expression of GAD67 and GAD25 in human PFC and hippocampus, our data suggest that epigenetic factors are involved in the dysregulation of expression of GAD67 and GAD25 in human PFC and hippocampus of patients with schizophrenia. This study provides novel insights regarding the role of GAD1 in brain developmental and function.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Amy Deep-Soboslay, M.Ed. of Lieber Institute for Brain development for the efforts in clinical diagnosis and demographic characterization.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors of this paper have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Reference

- 1.LoTurco JJ, Owens DF, Heath MJ, Davis MB, Kriegstein AR. GABA and glutamate depolarize cortical progenitor cells and inhibit DNA synthesis. Neuron 1995; 15: 1287–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marty S, Berninger B, Carroll P, Thoenen H. GABAergic stimulation regulates the phenotype of hippocampal interneurons through the regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Neuron 1996; 16: 565–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Behar TN, Schaffner AE, Scott CA, Greene CL, Barker JL. GABA receptor antagonists modulate postmitotic cell migration in slice cultures of embryonic rat cortex. Cereb Cortex N Y N 1991 2000; 10: 899–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varju P, Katarova Z, Madarász E, Szabó G. Sequential induction of embryonic and adult forms of glutamic acid decarboxylase during in vitro-induced neurogenesis in cloned neuroectodermal cell-line, NE-7C2. J Neurochem 2002; 80: 605–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erlander MG, Tillakaratne NJ, Feldblum S, Patel N, Tobin AJ. Two genes encode distinct glutamate decarboxylases. Neuron 1991; 7: 91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bu DF, Erlander MG, Hitz BC, Tillakaratne NJ, Kaufman DL, Wagner-McPherson CB et al. Two human glutamate decarboxylases, 65-kDa GAD and 67-kDa GAD, are each encoded by a single gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1992; 89: 2115–2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asada H, Kawamura Y, Maruyama K, Kume H, Ding RG, Kanbara N et al. Cleft palate and decreased brain gamma-aminobutyric acid in mice lacking the 67-kDa isoform of glutamic acid decarboxylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997; 94: 6496–6499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Condie BG, Bain G, Gottlieb DI, Capecchi MR. Cleft palate in mice with a targeted mutation in the gamma-aminobutyric acid-producing enzyme glutamic acid decarboxylase 67. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997; 94: 11451–11455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mason GF, Martin DL, Martin SB, Manor D, Sibson NR, Patel A et al. Decrease in GABA synthesis rate in rat cortex following GABA-transaminase inhibition correlates with the decrease in GAD(67) protein. Brain Res 2001; 914: 81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akbarian S, Kim JJ, Potkin SG, Hagman JO, Tafazzoli A, Bunney WE et al. Gene expression for glutamic acid decarboxylase is reduced without loss of neurons in prefrontal cortex of schizophrenics. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1995; 52: 258–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Volk D, Austin M, Pierri J, Sampson A, Lewis D. GABA transporter-1 mRNA in the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia: decreased expression in a subset of neurons. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158: 256–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashimoto T, Volk DW, Eggan SM, Mirnics K, Pierri JN, Sun Z et al. Gene expression deficits in a subclass of GABA neurons in the prefrontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci 2003; 23: 6315–6326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curley AA, Arion D, Volk DW, Asafu-Adjei JK, Sampson AR, Fish KN et al. Cortical deficits of glutamic acid decarboxylase 67 expression in schizophrenia: clinical, protein, and cell type-specific features. Am J Psychiatry 2011; 168: 921–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Addington AM, Gornick M, Duckworth J, Sporn A, Gogtay N, Bobb A et al. GAD1 (2q31.1), which encodes glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD67), is associated with childhood-onset schizophrenia and cortical gray matter volume loss. Mol Psychiatry 2005; 10: 581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Straub RE, Lipska BK, Egan MF, Goldberg TE, Callicott JH, Mayhew MB et al. Allelic variation in GAD1 (GAD67) is associated with schizophrenia and influences cortical function and gene expression. Mol Psychiatry 2007; 12: 854–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao X, Qin S, Shi Y, Zhang A, Zhang J, Bian L et al. Systematic study of association of four GABAergic genes: glutamic acid decarboxylase 1 gene, glutamic acid decarboxylase 2 gene, GABA(B) receptor 1 gene and GABA(A) receptor subunit beta2 gene, with schizophrenia using a universal DNA microarray. Schizophr Res 2007; 93: 374–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Du J, Duan S, Wang H, Chen W, Zhao X, Zhang A et al. Comprehensive analysis of polymorphisms throughout GAD1 gene: a family-based association study in schizophrenia. J Neural Transm Vienna Austria 1996 2008; 115: 513–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kundakovic M, Chen Y, Costa E, Grayson DR. DNA methyltransferase inhibitors coordinately induce expression of the human reelin and glutamic acid decarboxylase 67 genes. Mol Pharmacol 2007; 71: 644–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Veldic M, Caruncho HJ, Liu WS, Davis J, Satta R, Grayson DR et al. DNA-methyltransferase 1 mRNA is selectively overexpressed in telencephalic GABAergic interneurons of schizophrenia brains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004; 101: 348–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Veldic M, Guidotti A, Maloku E, Davis JM, Costa E. In psychosis, cortical interneurons overexpress DNA-methyltransferase 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005; 102: 2152–2157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruzicka WB, Subburaju S, Benes FM. Circuit- and Diagnosis-Specific DNA Methylation Changes at γ-Aminobutyric Acid–Related Genes in Postmortem Human Hippocampus in Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 2015; 72: 541–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Subburaju S, Coleman AJ, Cunningham MG, Ruzicka WB, Benes FM. Epigenetic Regulation of Glutamic Acid Decarboxylase 67 in a Hippocampal Circuit. Cereb Cortex 2016. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhw307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Subburaju S, Coleman AJ, Ruzicka WB, Benes FM. Toward dissecting the etiology of schizophrenia: HDAC1 and DAXX regulate GAD67 expression in an in vitro hippocampal GABA neuron model. Transl Psychiatry 2016; 6: e723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bond RW, Wyborski RJ, Gottlieb DI. Developmentally regulated expression of an exon containing a stop codon in the gene for glutamic acid decarboxylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1990; 87: 8771–8775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szabo G, Katarova Z, Greenspan R. Distinct protein forms are produced from alternatively spliced bicistronic glutamic acid decarboxylase mRNAs during development. Mol Cell Biol 1994; 14: 7535–7545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu H, Zhang Y, Li S, Yan Y, Li Y. Dynamic regulation of glutamate decarboxylase 67 gene expression by alternative promoters and splicing during rat testis maturation. Mol Biol Rep 2010; 37: 3111–3119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Popp A, Urbach A, Witte OW, Frahm C. Adult and embryonic GAD transcripts are spatiotemporally regulated during postnatal development in the rat brain. PloS One 2009; 4: e4371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lynex CN, Carr IM, Leek JP, Achuthan R, Mitchell S, Maher ER et al. Homozygosity for a missense mutation in the 67 kDa isoform of glutamate decarboxylase in a family with autosomal recessive spastic cerebral palsy: parallels with Stiff-Person Syndrome and other movement disorders. BMC Neurol 2004; 4: 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hyde TM, Lipska BK, Ali T, Mathew SV, Law AJ, Metitiri OE et al. Expression of GABA signaling molecules KCC2, NKCC1, and GAD1 in cortical development and schizophrenia. J Neurosci Off J Soc Neurosci 2011; 31: 11088–11095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li M, Jaffe AE, Straub RE, Tao R, Shin JH, Wang Y et al. A human-specific AS3MT isoform and BORCS7 are molecular risk factors in the 10q24.32 schizophrenia-associated locus. Nat Med 2016; 22: 649–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jaffe AE, Gao Y, Deep-Soboslay A, Tao R, Hyde TM, Weinberger DR et al. Mapping DNA methylation across development, genotype and schizophrenia in the human frontal cortex. Nat Neurosci 2016; 19: 40–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aryee MJ, Jaffe AE, Corrada-Bravo H, Ladd-Acosta C, Feinberg AP, Hansen KD et al. Minfi: a flexible and comprehensive Bioconductor package for the analysis of Infinium DNA methylation microarrays. Bioinforma Oxf Engl 2014; 30: 1363–1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chessler SD, Lernmark A. Alternative splicing of GAD67 results in the synthesis of a third form of glutamic-acid decarboxylase in human islets and other non-neural tissues. J Biol Chem 2000; 275: 5188–5192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trifonov S, Yamashita Y, Kase M, Maruyama M, Sugimoto T. Glutamic acid decarboxylase 1 alternative splicing isoforms: characterization, expression and quantification in the mouse brain. BMC Neurosci 2014; 15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-15-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krizbai IA, Katarova Z, Szabó G, Párducz A, Wolff JR. Modulation of the truncated GAD25 by estrogen in the olfactory bulb of adult rats. Neuroreport 2000; 11: 791–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Szabó G, Kartarova Z, Hoertnagl B, Somogyi R, Sperk G. Differential regulation of adult and embryonic glutamate decarboxylases in rat dentate granule cells after kainate-induced limbic seizures. Neuroscience 2000; 100: 287–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu K-T, Wu C-Y, Cheng N-C, Wo Y-YP, Yang J-T, Yen H-H et al. Inhibition of the Na+−K+−2Cl−-cotransporter in choroid plexus attenuates traumatic brain injury-induced brain edema and neuronal damage. Eur J Pharmacol 2006; 548: 99–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boulenguez P, Liabeuf S, Bos R, Bras H, Jean-Xavier C, Brocard C et al. Down-regulation of the potassium-chloride cotransporter KCC2 contributes to spasticity after spinal cord injury. Nat Med 2010; 16: 302–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sullivan CR, Funk AJ, Shan D, Haroutunian V, McCullumsmith RE. Decreased Chloride Channel Expression in the Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex in Schizophrenia. PLOS ONE 2015; 10: e0123158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weinberger DR. Implications of normal brain development for the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1987; 44: 660–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen Y, Dong E, Grayson DR. Analysis of the GAD1 promoter: trans-acting factors and DNA methylation converge on the 5’ untranslated region. Neuropharmacology 2011; 60: 1075–1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davis KN, Tao R, Li C, Gao Y, Gondré-Lewis MC, Lipska BK et al. GAD2 Alternative Transcripts in the Human Prefrontal Cortex, and in Schizophrenia and Affective Disorders. PLOS ONE 2016; 11: e0148558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gos T, Günther K, Bielau H, Dobrowolny H, Mawrin C, Trübner K et al. Suicide and depression in the quantitative analysis of glutamic acid decarboxylase-Immunoreactive neuropil. J Affect Disord 2009; 113: 45–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li D, Yang X, Ge Z, Hao Y, Wang Q, Liu F et al. Cigarette smoking and risk of completed suicide: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Psychiatr Res 2012; 46: 1257–1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mäkikyrö TH, Hakko HH, Timonen MJ, Lappalainen JA, Ilomäki RS, Marttunen MJ et al. Smoking and suicidality among adolescent psychiatric patients. J Adolesc Health 2004; 34: 250–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benes FM. Nicotinic Receptors and Functional Regulation of GABA Cell Microcircuitry in Bipolar Disorder and Schizophrenia In: Geyer MA, Gross G (eds). Novel Antischizophrenia Treatments. Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012, pp 401–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jow F, Chiu D, Lim H-K, Novak T, Lin S. Production of GABA by cultured hippocampal glial cells. Neurochem Int 2004; 45: 273–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee M, Schwab C, McGeer PL. Astrocytes are GABAergic cells that modulate microglial activity. Glia 2011; 59: 152–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Skene NG, Grant SGN. Identification of Vulnerable Cell Types in Major Brain Disorders Using Single Cell Transcriptomes and Expression Weighted Cell Type Enrichment. Front Neurosci 2016; 10. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.