Abstract

Systematic administration of anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin 4 (IL-4) has been shown to improve recovery after cerebral ischemic stroke. However, whether IL-4 affects neuronal excitability and how IL-4 improves ischemic injury remain largely unknown. Here we report the neuroprotective role of endogenous IL-4 in focal cerebral ischemia–reperfusion (I/R) injury. In multi-electrode array (MEA) recordings, IL-4 reduces spontaneous firings and network activities of mouse primary cortical neurons. IL-4 mRNA and protein expressions are upregulated after I/R injury. Genetic deletion of Il-4 gene aggravates I/R injury in vivo and exacerbates oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) injury in cortical neurons. Conversely, supplemental IL-4 protects Il-4−/− cortical neurons against OGD injury. Mechanistically, cortical pyramidal and stellate neurons common for ischemic penumbra after I/R injury exhibit intrinsic hyperexcitability and enhanced excitatory synaptic transmissions in Il-4−/− mice. Furthermore, upregulation of Nav1.1 channel, and downregulations of KCa3.1 channel and α6 subunit of GABAA receptors are detected in the cortical tissues and primary cortical neurons from Il-4−/− mice. Taken together, our findings demonstrate that IL-4 deficiency results in neural hyperexcitability and aggravates I/R injury, thus activation of IL-4 signaling may protect the brain against the development of permanent damage and help recover from ischemic injury after stroke.

Key words: Anoxic depolarization, IL-4, Ischemia–reperfusion injury, Neuronal excitability, Synaptic transmissions

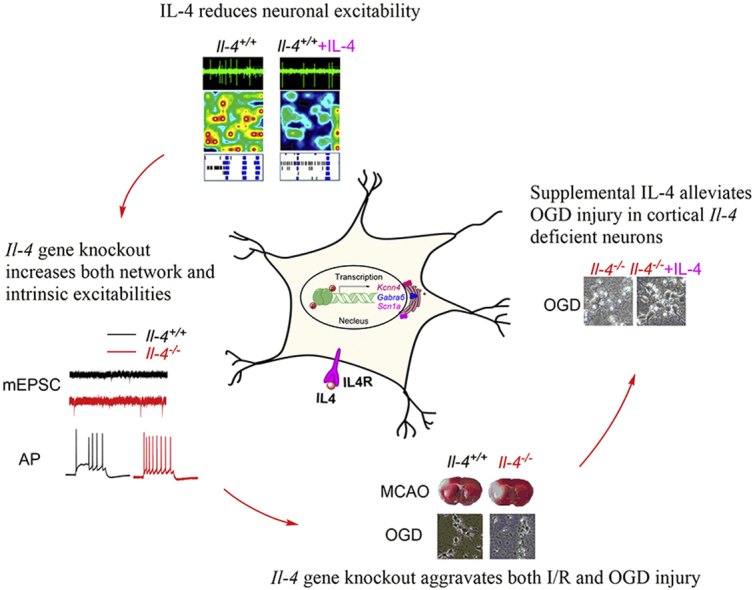

Graphical abstract

This study reveals a previously unknown mechanism by which IL-4 deficiency causes neural hyperexcitability and enhances neuronal excitatory transmissions. Supplementing IL-4 might be beneficial for improvement of functional recovery after brain ischemia injury.

1. Introduction

Stroke is the second leading cause of death and the major cause of long-term disability worldwide. Ischemic stroke represents approximately 87% of all brain strokes1. During ischemic stroke, energy depletion induces anoxic depolarization and excitotoxicity of cortical neurons characterized by progressive cell death and development of permanent local brain damage2. Meanwhile, proinflammatory mediators are released from activated resident microglia for participation in neuroinflammation3, further aggravating neuronal loss and brain damage.

Conversely, several lines of evidence suggest that neurons can rapidly respond to ischemic conditions by secreting molecules that support brain tissue healing and repairing4,5. It has recently been shown that as an intrinsic defense mechanism neurons produce and secrete anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin 4 (IL-4) in response to sublethal ischemic injury6. IL-4 participates in protecting injured neurons in central nervous system7. Interleukin 4 receptor alpha chain (IL-4Rα) is expressed in neurons and plays a critical role in modulating neuronal death through activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6) during ischemia8. IL-4 stimulates microglial phagocytosis and enables efficient clearance of apoptotic neurons for repair6. Systemic administration of IL-4 also reduces ischemic lesion and improves neurologic function after stroke6,9, 10, 11. All these investigations indicate that neuronal IL-4 is actively involved in promoting recovery of brain injury after stroke. However, the underlying mechanism for neuroprotective role of neuronal IL-4 in ischemic recovery remains largely unknown.

Previous studies have shown that the anti-apoptotic function of IL-4 is closely related to hyperpolarization of mitochondrial membrane potential in different cells including effector CD4 cells12 and B cells13. The interaction of IL-4 with its high-affinity receptor IL-4Rα and the subsequent recruitment of the IL-2Rγ chain14,15 are related to membrane depolarization of T cells16. The upregulation of IL-4 expression influences membrane potential oscillations due to opening of intermediate/small conductance calcium-activated K+ channel (KCa3.1, encoded by Kcnn4 gene) in macrophages17. Interestingly, IL-4 upregulates KCa3.1 expression and increases KCa3.1 current through IL-4 receptor (IL-4R) signaling pathway in microglia18, and KCa3.1 contributes to regulation of after-hyperpolarization potentials (AHPs)19. All these investigations suggest that an enhanced neuronal IL-4 signaling may regulate neuronal membrane potential, thus affecting the excitability of neurons in the brain. We, therefore, hypothesize that neuronal IL-4 might have a direct impact on anoxic depolarization or hyperexcitability during ischemic injury after stroke.

To test this hypothesis, we utilized Il-4 knockout (KO) mice and found that Il-4−/− mice were more susceptible to ischemia–reperfusion (I/R) injury induced by transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO) in vivo, and neurons from Il-4−/− mice were hyperexcitable. Mechanistically, genetic deletion of Il-4 resulted in intrinsic hyperexcitability in cortical neurons with upregulation of Nav1.1 channels, and downregulations of KCa3.1 channels and α6 subunits of GABAA receptors. These findings for the first time demonstrate a previously unknown mechanism that loss of IL-4 causes neural hyperexcitability, and the enhancement of neuronal IL-4 signaling by reduction of neuronal firing can protect the brain against development of permanent damage and help recover from ischemic injury after stroke.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals and agents

NMDA receptor antagonist d-2-amino-5-phosphonovalerate (AP5) and α-amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionate (AMPA)/kainate glutamate receptor antagonist 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX) were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Neurobiotin™ tracer N-(2-aminoethyl) biotinamide hydrochloride was purchased from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA, USA), and molecular probe Alexa 488-conjugated streptavidin was obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). Neuronal medium NbActiv4 was from Brain Bits (Springfield, IL, USA), animal-free murine IL-4 was purchased from Peprotech (Rocky Hill, NJ, USA).

2.2. Il-4 gene knockout mice

A “neo cassete” was inserted into the SacI site (GAGCTC) in the exon 3 of the interleukin 4 gene (ID: 16189) to produce the Il-4 gene KO mice (Supporting Information Fig. S2A). The genotyping was determined using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Briefly, genomic DNA was extracted from ear or tail (0.2 cm) using the alkali extraction method20. A PCR was then performed using Ex Taq polymerase (TaKaRa-Bio, Kusatsu, Japan) and the following primers: primer 1, 5′-GTTGAGCAGATGACATTGGGGC-3′; primer 2, 5′-CTTCAAGCATGGAGTTTTCCC-3′; primer 3, 5′-GCGCATCGCCTTCTATCGCCTTC-3′.

The PCR consisted of an initial 2 min at 94 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 15 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 57 °C and 30 s at 72 °C. After the last cycle, the reaction is kept at 72 °C for 10 min before held at 4 °C. A 180 bp cDNA band was observed for wild-type allele, whereas a 208 bp band was detected for the mutant allele, and heterozygotes containing both alleles were detected with the two bands.

2.3. Multi-electrode array (MEA) recordings

Cortical neurons from newborn C57BL/6J mice (<24 h) were acutely dissociated and suspended in NbActiv4 (Brain Bits) medium. Approximately ∼7 × 104 neurons in 8 μL medium were seeded on 12-well MEA plates (Axion Biosystems Inc, Atlanta, GA, USA) coated with poly-d-lysine (40 μg/mL)/laminin (20 μg/mL). 20 ng/mL IL-4 (Peprotech) was added in the culture media in IL-4 group for 16 days. On the 3rd day, cytarabine (2.5 μg/mL) was added to suppress the proliferation of glial cells by mitotic inhibition for up to seven days21.

Neuronal activities were recorded using an MEA system (Axion Maestro Pro) and data are analyzed using Axion Integrated Studio AxIS2.1 (Axion Biosystems Inc, Atlanta, GA, USA) and NeuroExplorer (Nex Technologies, Madison, AL, USA) as previously described22. In the MEA recordings, a spike detection criterion of >6 standard deviations above the background was used to separate monophasic or biphasic action potential spikes from the noise22. Active electrodes were defined as >1 spike over a 200-s analysis period. Firing frequencies were averaged among all active electrodes from wells expressing either construct22.

2.4. Whole-cell patch clamp recordings of acute brain slices

Mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (60 mg/kg, i.p.) and decapitated before their brains were dissected into ice-cold slicing solution. Acute horizontal (for patch recordings of medial entorhinal cortex (mEC) layer II stellate neurons) or coronal slices (for patch recordings of motor cortical neurons) at a 300-μm thickness on a vibratome (Leica VT1200S, Leica, Nussloch, Germany) and transferred to normal artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF). Then, slices were incubated at 37 °C for 20–30 min and stored at room temperature before use.

The medium after-hyperpolarization potential (mAHP) slope was calculated with Eq. (1):

| (1) |

where Vsmall-peak and Tsmall-peak are the small peak membrane potential and time-point at the end of an action potential (AP) respectively, Vtrough and Ttrough are the trough membrane potential and time-point at the end of fast after-hyperpolarization potential (fAHP), respectively.

The sag ratio was calculated with Eq. (2):

| (2) |

where Vbaseline is the resting membrane potential or −70 mV, Vmin is the minimum voltage reached soon after the hyperpolarizing current pulse, and Vsteady-state is the average voltage recorded at 0–10 ms before the end of the −200 pA stimulus.

The input resistance (IR) was calculated with Eq. (3):

| (3) |

where Vbaseline is the resting membrane potential or −70 mV, and Vsteady-state is the average voltage recorded at 0–10 ms before the end of the −100 pA stimulus.

For whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings of miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs), the internal solution contained (in mmol/L): 122 CsCl, 1 CaCl2, 5 MgCl2, 10 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 4 Na2ATP, 0.3 Tris-GTP, 14 Tris-phosphocreatine, adjusted to pH 7.3 with CsOH. Tetrodotoxin (TTX; sodium channel blocker, 0.5 μmol/L), AP5 (NMDA receptor antagonist, 50 μmol/L), CNQX (AMPA/kainate glutamate receptor antagonist, 10 μmol/L) were applied to block excitatory synaptic transmission. For recordings of miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs), the internal solution contained (in mmol/L): 118 KMeSO4, 15 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 0.2 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 4 Na2ATP, 0.3 Tris-GTP, 14 Tris-phosphocreatine, adjusted to pH 7.3 with KOH. TTX, bicuculline (GABAA receptor antagonist, 10 μmol/L) and CGP55845 (selective GABAB receptor antagonist, 2 μmol/L) were applied to block inhibitory synaptic transmission. We used thick-wall borosilicate glass pipettes, which were pulled with open-tip resistances of 4–6 MΩ. Slices were maintained under continuous perfusion of ACSF at 32–33 °C with a flow rate of 2–3 mL/min. In the whole-cell configuration, series resistance (Rs) was maintained at the range of 15–30 MΩ, and the recordings with unstable Rs or a change of Rs > 20% were aborted.

For cell labeling, the internal solution either for whole-cell current clamp recordings or for voltage-clamp recordings contained 0.1%–0.2% (w/v) neurobiotin tracer. At the end of the electrophysiological recordings (∼30 min), slices were treated as previously described23,24. Labeled neurons in brain slices were imaged by laser scanning confocal microscopy (TCS-SP8 STED 3X, Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) with 40 × oil-immersion objectives for pyramidal neurons and 63 × oil-immersion objectives for stellate neurons.

All recordings were performed at least 10 min after breakthrough for internal solution exchange equilibrium using a MultiClamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Device, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), and data were acquired using pCLAMP 10.6 software and filtered using a Digidata 1440A digitizer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Only a single neuron was recorded in each brain slice.

2.5. Culture of mouse primary cortical neurons

Cortical neurons were dissociated from newborn mice (within 24 h) by 0.25% trypsinization25. Cells were suspended in high-glucose DMEM (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) before plated on poly-d-lysine hydrobromide (Sigma–Aldrich) coated 12-well culture plates at a density of approximate 1.2 × 105 cells/cm2 for different experiments. After 4–6 h seeding, the medium was changed to phenol red-free neurobasal A medium (Gibco) supplemented with 2% B27 (Gibco), containing 0.5 mmol/L GlutaMAX-Ⅰ, and 0.5% penicillin–streptomycin before one-half medium was refreshed every three days. On the 3rd day, cytarabine (2.5 μg/mL) was added to suppress the proliferation of glial cells by mitotic inhibition for up to seven days21. Cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 95% air and 5% CO2 and used for experiments after 7–9 days in vitro.

2.6. In vivo model of I/R injury induced by middle cerebral artery occlusion in mice

C57BL/6J mice (12 ± 2 weeks) were obtained from the Department of Laboratory Animal Science, Peking University Health Science Center (Beijing, China). The Il-4 gene knockout mice (12 ± 2 weeks, background is C57BL/6J) were kindly provided by Kopf's group26 and bred in our animal facility. All experimental procedures were approved by the Beijing Committee for Animal Care and Use. The surgery protocol was approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of Peking University Health Science Center (Beijing, China).

Mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (60 mg/kg, i.p.). A probe was connected to the left skull for monitoring relative local cerebral blood flow (LCBF) with laser Doppler flowmetry (LDF) (Periflux 5000, Perimed, Sweden). Transient focal cerebral ischemia was induced by left tMCAO for 90 min. The LCBF drops and maintains below 80% of the baseline during ischemia27. Scoring of neurological deficits following stroke was evaluated by the Longa method according to an expanded 7 scale28. The observer was blind to animal treatment, and one mouse obtaining no less than 2 scores was counted as a valid model. Infarct areas were analyzed using Adobe Photoshop CC and determined by an indirect method correcting for edema29.

2.7. Oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) injury in mouse cortical neurons

The in vitro OGD injury model was generated as previously described30. The original media were replaced with a glucose-free and phenol red-free DMEM containing 10 mmol/L of sodium dithionite (Na2S2O4), a deoxygenated reagent for 30 min (or 20 min), before return to their original culture medium for maintenance of 24 h until the assay of cell injury.

The release amount of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) into the culture medium as a measurement of cell death was measured using LDH assay reagent (Promega, Fitchburg, WI, USA) according to the instructions30. The survival cell viability was estimated by a cell counting kit-8 assay (CCK-8, Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan)31. At least three wells were measured in each group. For the calculation of LDH release, we took the value in the sham group as 100%, and the value in the OGD group was divided by the sham group to get the relative value of LDH release. In the rescue experiment, we took the Il-4−/− group value as 100%, and the value of adding IL-4 was divided by that of Il-4−/− group to get the relative value.

2.8. RNA isolation, reverse transcription and qRT-PCR analysis

After MCAO surgery for 6, 12, and 24 h, the brains were divided ischemia part and contralateral part to extract RNAs. Total RNAs were extracted with TRIzol reagent (Sigma) from mouse cerebral tissues or cortical neurons according to the manufacturer's instructions. 4 μg RNA was subjected to reverse transcription (RT) with a GoScript™ Reverse Transcription System (Promega), and the resulting cDNA subjected to quantitative RT-PCR analysis with the use of GoTaq® qPCR Master Mix (Promega) and specific primers in a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). PCR primer sequences were listed in the Supporting Information Table S7. The calculation was based on follows using the ΔΔCt method32. For calculation of relative expression of Il-4 mRNAs in each brain after ischemic injury, we took the contralateral value as 1, and the ischemic area part value was divided by the value from the contralateral part to get the relative value.

2.9. Western blot

After MCAO surgery for 6, 12, and 24 h, mouse brains were removed and divided ischemia part and contralateral part to extract whole protein. Total proteins were extracted in cold RIPA lysis buffer containing 2% cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Protein samples were loaded on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis before transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA, USA). After blocking by 5% milk, PVDF membranes were incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight such as rat anti-IL-4 antibody (1:500, Abcam, ab11524), mouse monoclonal anti-KCa3.1 antibody (1:250, Alomone, ALM-051), rabbit anti-Nav1.1 antibody (1:250, Alomone, ASC-001), rabbit GABAA R α6 Polyclonal Antibody (1:200, Alomone, AGA-004), mouse anti-β-actin antibody (1:5000, Abcam) and mouse anti-GAPDH antibody (1:5000, Abcam). The membranes were then incubated with their corresponding secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies before detected using an ECL Western blotting detection system (Millipore). The immunoreactive bands were scanned by Tanon 5200 instrument, captured by Tanon MP system before quantitative analysis by densitometry with Tanon GIS software. For calculation of relative expression of IL-4 proteins, we took the contralateral value as 1, and the ischemic area value was divided by the value from the contralateral part to get the relative value.

2.10. Immunostaining and confocal microscopy

Mouse primary cortical neurons in 15 mm culture dish after seven to nine days were fixed with 4% PFA for 15 min at room temperature after washed three times by 0.01 mol/L PBS before blocked by 10% sheep serum with 0.3% Triton X-100 (Amresco, Solon, OH, USA) in 0.01 mol/L PBS for 1 h. Cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies including rabbit monoclonal NeuN antibody (1:1000, Abcam, ab177487), mouse monoclonal anti-KCa3.1 antibody (1:200, Alomone, ALM-051) and rabbit anti-Nav1.1 antibody (1:200, Alomone, ASC-001). To test neuronal purity of the primary cultured cortical neurons, we also used rabbit anti-GFAP (glial fibrillary acidic protein) antibody (1:200, Abcam, ab16997) for astrocytes; recombinant anti-Iba1 (ionized calcium-binding adaptor molecule-1) antibody [EPR16589] (1:500, Abcam, ab178847) for microglial cells; and rat mAb to anti-MBP (Myelin basic protein) antibody (1:100, Abcam, ab7349) for oligodendrocytes. The immunoreactivity was visualized with Alexa Fluor 488- or 594-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:500; ZSGB-BIO) and goat anti-rat IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488) (1:500, Abcam, ab150165). The nuclei were stained by Hochest33342. Immunocytochemical staining was scanned by confocal microscopy (TCS SP8 II, Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

2.11. Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the means ± SEM. Unless otherwise noted, statistical significance was determined using unpaired Student's t-test for comparison between two groups. Two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test was used for the comparison between multiple groups. Each “n” indicates the number of independent experiments. A value of P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

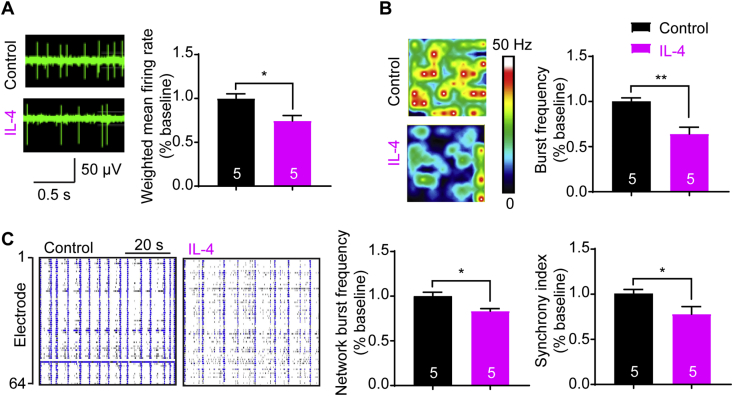

3.1. Reduction of spontaneous firings and network activities of mouse primary cortical neurons by IL-4 in multi-electrode array recordings

To test whether IL-4 had a direct effect on neuronal firings, we started performing multi-electrode array (MEA) recordings of spontaneous firings in primary cortical neurons in the presence of cytarabine that inhibits glial cells to purify neurons to 92.0% (Supporting Information Fig. S1). As shown in Fig. 1, robust spontaneous firings of cortical neurons were recorded, and adding IL-4 (20 ng/mL) decreased the spike frequency about 26% (Fig. 1A), burst activity about 36% (Fig. 1B), network bursting frequency about 17% and the synchrony of spontaneous spikes about 22% (Fig. 1C). These data show that IL-4 attenuates spontaneous neuronal firing and network burst activity, suggesting a direct effect of IL-4 on neural excitability.

Figure 1.

Attenuation of spontaneous firings and network activities of mouse primary cortical neurons by IL-4 in multi-electrode array (MEA) recordings. (A) Raw traces of neuronal firings for a single electrode recordings of mouse primary cortical neurons in the presence or absence of IL-4 (20 ng/mL) after culture of 16 days. (B) Heat-maps of representative MEA recordings of cortical neurons, and reduction of burst frequency in IL-4 group. (C) Well-wide (64 electrodes) raster plots of MEA recordings of cortical neurons for 1.0 min, and reduction of network burst frequency and synchrony index with IL-4. Data are collected from 5 wells of MEA plates (320 electrodes) and are expressed as the mean ± SEM, ∗P < 0.05 and ∗∗P < 0.01 versus the control group. The numbers at the bottom of the bars indicate the number of wells.

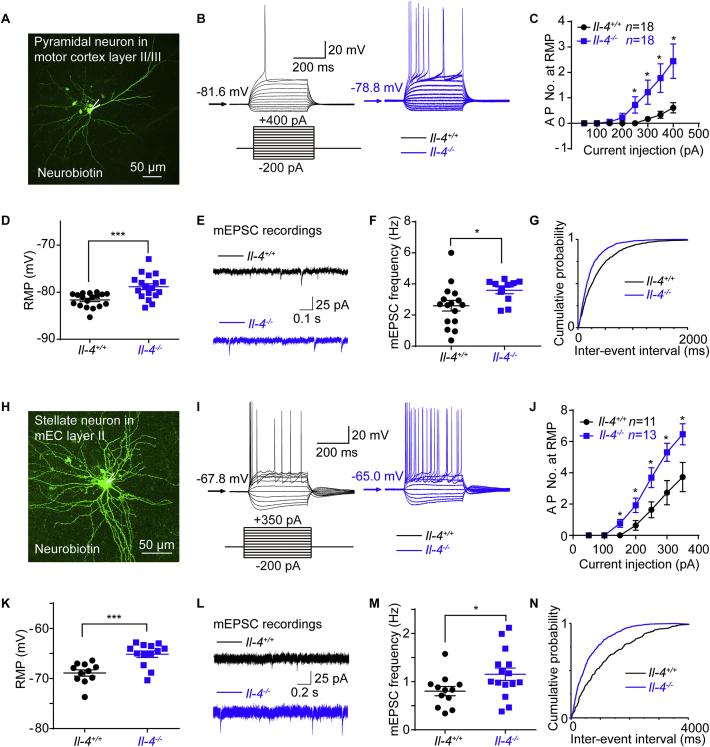

3.2. Increased neuronal excitability and excitatory synaptic transmissions of cortical neurons in Il-4−/− mice

To confirm the effect of IL-4 on neural excitability, we utilized Il-4 gene knockout (Il-4−/−) mice generated by Kopf's group (Supporting Information Fig. S2). As ischemic penumbra after I/R injury commonly occurs in the cortex where IL-4 and IL-4Rα are also expressed8, we recorded the layer II/III pyramidal neurons in the motor cortex (M1) that controls motor function33 and layer II stellate neurons in mEC that provides main excitatory inputs to the hippocampus34.

In response to a series of 400 ms current steps, layer II/III pyramidal neurons from Il-4−/− mice fired more action potentials (APs) and exhibited depolarized resting membrane potentials (RMPs, Fig. 2A–D and Supporting Information Table S1), indicating that Il-4−/− neurons were hyperexcitable mainly due to their depolarized RMPs. When holding at −70 mV, the mAHP slope increased in Il-4−/− pyramidal neurons (Supporting Information Fig. S2F).

Figure 2.

Hyperexcitability and enhanced synaptic transmissions of pyramidal and stellate neurons from Il-4−/− mice. (A) Morphology of pyramidal neurons in the motor cortex (M1) layer II/III labeled with neurobiotin. (B) Representative traces for neuronal firings by whole-cell current clamp recordings of Il-4+/+ and Il-4−/− pyramidal neuron. (C) The comparison of fired action potential numbers (AP No.) between of Il-4−/− and Il-4+/+ pyramidal neurons. (D) The resting membrane potentials (RMP) of Il-4+/+ and Il-4−/− pyramidal neurons. (E) Representative traces for miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) by voltage-clamp recordings of Il-4+/+ and Il-4−/− pyramidal neurons. (F) Increased frequency of mEPSCs with a cumulative probability of shorter inter-event intervals. (G) In Il-4−/− pyramidal neurons. (H) Morphology of a stellate neuron in mEC layer II for patch-clamp recordings. (I) The representative traces for neuronal firings of recordings of Il-4+/+ and Il-4−/− stellate neurons. (J) Comparison of fired AP No. and RMP (K) between of Il-4+/+ and Il-4−/− stellate neurons. (L) Representative traces for mEPSCs in Il-4+/+ and Il-4−/− stellate neurons. (M) Increased frequency of mEPSCs with a cumulative probability of shorter inter-event intervals. (N) in Il-4−/− stellate neurons. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM; n indicates the number of cells recorded, ∗P < 0.05, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001 versus Il-4+/+ group.

To further investigate whether Il-4 null had any influence on synaptic transmissions, we recorded of cortical pyramidal neurons for miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs) and miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs). The mEPSC frequency of Il-4−/− pyramidal neurons, but not the mIPSC, increased with cumulative probability of shorter inter-event intervals (Fig. 2E–G and Supporting Information Tables S2 and S3), indicating that Il-4−/− neurons exhibited enhanced excitatory synaptic transmissions.

Current-clamp recordings of Il-4−/− stellate neurons further confirmed the increased number of APs due to depolarized RMP (Fig. 2H–K and Supporting Information Table S4), increased mAHP slope at −70 mV (Fig. S2J), and enhanced mEPSC frequency (Fig. 2L–N and Supporting Information Table S5), but not the mIPSC (Supporting Information Table S6), consistent with the observations for the pyramidal neurons. All these results indicated that IL-4 deficiency enhanced neuronal excitability and excitatory synaptic transmissions in both cortical pyramidal and stellate excitatory neurons.

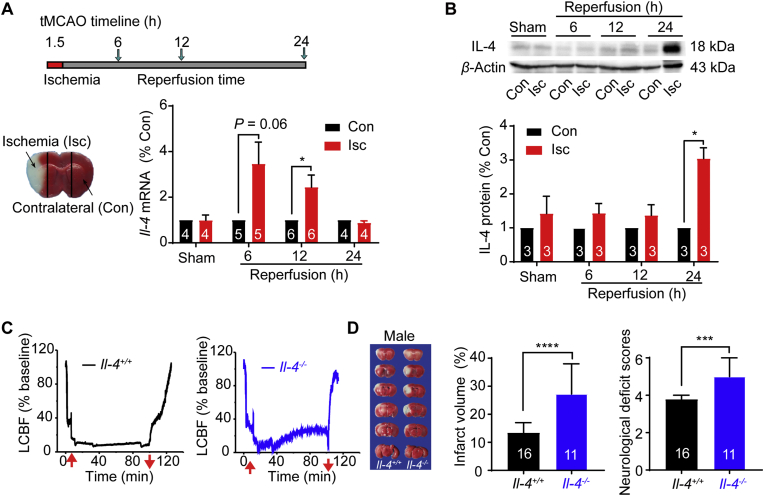

3.3. Upregulation of IL-4 in ischemic brain after focal I/R injury

To examine the expression of IL-4 after brain injury, we generated mouse focal cerebral ischemia by tMCAO for 90 min and reperfusion for different durations (6, 12 and 24 h). As shown in Fig. 3A, the mRNA expression of Il-4 in the Isc region after tMCAO increased to 3.5-fold at 6 h, 2.4-fold at 12 h and declined to the baseline level at 24 h after reperfusion. Western blot analysis further revealed that the protein expression of IL-4 in the Isc hemisphere increased to 3.0-fold after reperfusion for 24 h (Fig. 3B). These results suggested the upregulation of IL-4 signaling under ischemic conditions.

Figure 3.

Upregulations of IL-4 after focal ischemia-reperfusion injury and aggravation of brain ischemia by Il-4 silencing. (A) Schematic timeline of transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAO) in mice subjected to 1.5 h ischemia before reperfusion for 6, 12 or 24 h, and representative image of ischemic (Isc) and contralateral (Con) regions. Upregulation of Il-4 mRNA in the Isc region at 6 and 12 h after 1.5 h ischemia by real-time PCR analysis. (B) Upregulation of IL-4 protein expression in Isc at 24 h after reperfusion by Western blot analysis. (C) Representative local cerebral blood flow (LCBF) measured by laser Doppler flowmetry (LDF) in Il-4+/+ mouse (left) and Il-4−/− mouse (right) subject to I/R injury in tMCAO model. Red arrows indicate insertion and withdrawal of the filament. (D) Representative images of TTC-stained brain slices at 24 h after reperfusion from Il-4+/+ and Il-4−/− male mice. The white regions indicate the infarct size, and regions in red indicate the viable tissues. An increase of infarct volume (%) and neurological deficit scores in male Il-4−/− mice subjected to I/R injury. Data are presented as the median ± 95% CI, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001 versus Il-4+/+ group for Mann Whitney test. Other data are presented as the mean ± SEM. The numbers at the bottom of the bars indicate the number of repeats or mice in each group, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

3.4. Aggravation of focal brain I/R injury by Il-4 silencing in mice

To examine the role of IL-4 in ischemic injury, both Il-4−/− and Il-4+/+ mice were subjected to tMCAO injury for 90 min as monitored by the decline of local cerebral blood flow (LCBF) in laser Doppler flowmetry (LDF) assay (Fig. 3C). The declined LCBF was maintained about 20% of baseline as an indicator for successful occlusion of cerebral blood flow and there are no significant differences of the declined LCBF between the two genotypic groups of mice (Fig. 3C).

For assessment of the cerebral lesion induced by I/R injury, the infarct volume was measured after TTC staining. As shown in Fig. 3D, the total infarct volume of Il-4−/− male mice was 2.0-fold larger than those in Il-4+/+ male mice. The scoring of neurological deficits, determined by an expanded seven-point scale method also revealed that the behavior outcome of Il-4−/− male mice (5.00 ± 0.24, n = 10) was significantly worse than that of Il-4+/+ mice. Similarly, female Il-4−/− mice also exhibited the aggravated behavioral deficits and infarct volume after cerebral I/R injury (Supporting Information Fig. S3).

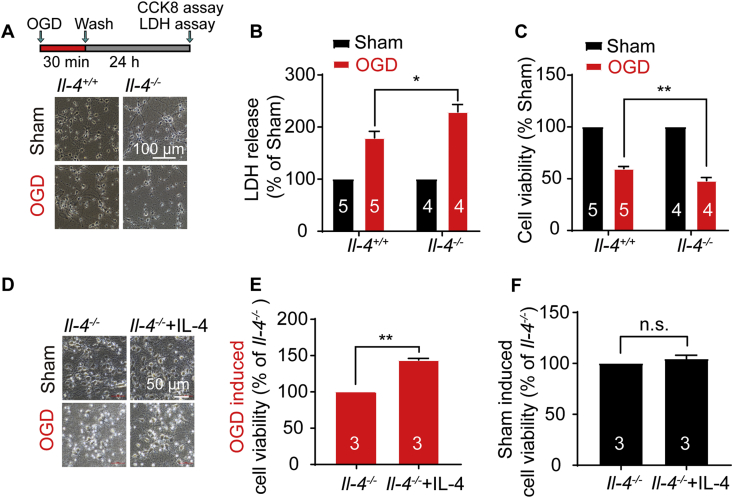

3.5. Il-4 deficient neurons are more susceptible to OGD injury and supplementing IL-4 alleviates OGD injury

To further verify the role of IL-4 in ischemic injury, neurons were subjected to oxygen-glucose deprivation injury for 30 min and reoxygenation (OGD/R) for 24 h (Fig. 4A). Cell death was determined by measuring the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release. Il-4−/− neurons had an elevated LDH release with approximately 28% more than that in Il-4+/+ neurons after OGD/R injury (Fig. 4B). Viable cells were measured by CCK-8 assay in which dehydrogenase activity of survival cells is directly proportional to the number of living cells. Data showed that the percentage of viable Il-4−/− neurons was about 24% lower than that of Il-4+/+ neurons subject to OGD/R injury (Fig. 4C), consistent with our earlier in vivo data. These results demonstrated that IL-4 deficiency increased the susceptibility of neurons to ischemic injury in vitro.

Figure 4.

Il-4 deficient neurons are susceptible to OGD injury and alleviation of the ischemia injury by supplemental IL-4. (A) Cortical neurons were subject to 30 min oxygen-glucose deprivation and 24 h reoxygenation (OGD/R) injury. The representative images for morphological changes of Il-4+/+ and Il-4−/− neurons at 24 h after washout. (B) Increase of the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release in LDH assay and (C) decrease of cell viability in Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8) assay of Il-4−/− primary cortical neurons subject to OGD/R injury. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM, n indicates the number of mice in each group, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 versus Il-4+/+ group. (D) The representative morphological images of Il-4−/− cortical neurons after adding IL-4 (20 ng/mL) for 7 days and subject to 20 min OGD/24 h R injury. Supplementing IL-4 increased the cell viability of Il-4−/− cortical neurons in the OGD injury group (E), but not in the Sham group (F). Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. The numbers at the bottom of the bars indicate the number of repeats. ∗∗P < 0.01 versus Il-4+/+ group, paired student t-test. n.s.: no significance.

To test any protective effect of IL-4, we added IL-4 (20 ng/mL) in the culture of cortical Il-4−/− neurons before subjected to 20 min OGD injury. Supplementing IL-4 resulted in an increased viability of OGD-injured Il-4−/− cortical neurons to 144% at 24 h, while at normal condition adding IL-4 had no effect on cell viability of Il-4−/− neurons (Fig. 4D–F). These results indicate that adding IL-4 can rescue OGD-induced injury in Il-4−/− neurons.

We also tested the neuronal firings in Il-4−/− brain slices after incubating 20 ng/mL IL-4 in ACSF for 4 h, and there was no significant difference in neuronal firing between Il-4−/− and Il-4−/− + IL-4 groups (Supporting Information Fig. S4).

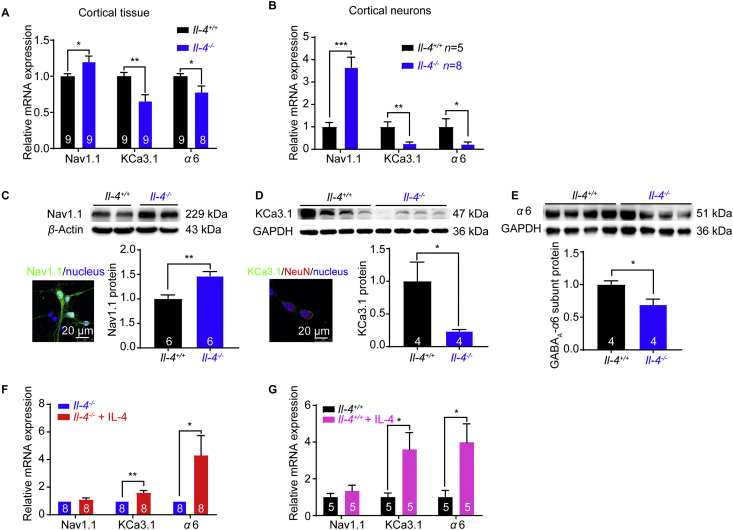

3.6. Upregulation of Nav1.1 and downregulation of KCa3.1 and α6 subunit of GABAA receptors in Il-4−/− mice and supplemental IL-4 increases KCa3.1 and α6 subunit mRNA expressions

Neuronal excitability is largely controlled by ion channels in concerted action35. To understand the mechanism underlying the hyperexcitability in Il-4−/− mice, we further tested the mRNA expression of ion channels that are critical for neuronal excitability. Among the ion channels tested (Supporting Inforamtion Fig. S5), Nav1.1 mRNA expression was upregulated about 1.2-fold, whereas KCa3.1 and α6 subunit of GABAA were downregulated to 0.66-fold and 0.78-fold in Il-4−/− cortical tissues, respectively (Fig. 5A). Further examination of cultured primary cortical neurons revealed an upregulation of Nav1.1 mRNA expression about 3.7-fold, and down-regulation of KCa3.1 and α6 subunit of GABAA to 0.27-fold and 0.24-fold, respectively (Fig. 5B). Western blot analysis further revealed that Nav1.1 protein expression was increased to 1.5-fold (Fig. 5C), whereas KCa3.1 and GABAA α6 subunit protein expressions were decreased to 0.19-fold and 0.70-fold in Il-4−/− mice, respectively (Fig. 5D and E), consistent with their mRNA expression levels.

Figure 5.

Upregulation of Nav1.1 and downregulations of KCa3.1 and α6 subunit of GABAA receptors in the cortex from Il-4−/− mice and supplemental IL-4 increases KCa3.1 and α6 mRNA expressions. Upregulation of Nav1.1 mRNA expression and downregulations of KCa3.1 and α6 subunit of GABAA receptors mRNA expression, in cortical tissues (A) and cortical neurons (B) from Il-4−/− mice. (C) Nav1.1 protein expression in primary mouse cortical neurons by immunostaining and upregulation of Nav1.1 protein in Il-4−/− mice (n = 6 mice). (D) The image staining with KCa3.1 antibody (green), NeuN antibody (red, a neuronal-specific nucleus marker) and DAPI (blue, a nucleus marker). Downregulation of KCa3.1 protein in Il-4−/− mice (n = 4 mice, Mann Whitney test). (E) Downregulation of α6 subunit of GABAA protein in Il-4−/− mice (n = 4 mice). Increased mRNA expressions of KCa3.1 and α6 subunit in Il-4−/− (F) and Il-4+/+ (G) cortical neurons after supplementing IL-4 (20 ng/mL) in culture for 7 days. Data are expressed as the mean ± SEM, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01 and ∗∗∗P < 0.001 compared with their controls. The numbers at the bottom of the bars indicate the number of repeats or mice in the group.

To test whether supplemental IL-4 could rescue the ion channel expressions, Il-4−/− cortical neurons were cultured for 7 days in the presence of IL-4 (20 ng/mL) or vehicle. RT-PCR analysis showed that the mRNA expressions of KCa3.1 and α6 subunit increased to 1.6-fold and 4.3-fold, respectively in Il-4−/− neurons in the presence of IL-4 compared to vehicle treated Il-4−/− neurons (Fig. 5F). In addition, we also tested the effect of supplemental IL-4 on the channel expressions in Il-4+/+ neurons, and the results showed that the mRNA expressions of KCa3.1 and α6 subunit were upregulated about 3.6-fold and 4.0-fold respectively in Il-4+/+ cortical neurons in the presence of IL-4, as compared to vehicle treated Il-4+/+ neurons (Fig. 5G). These results indicated that neuronal IL-4 deficiency resulted in the upregulation of Nav1.1 and downregulations of both KCa3.1 and α6 subunit of GABAA receptors.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to test the hypothesis that IL-4 signaling might exert a direct influence on neuronal excitability that defines the fundamental mechanism of brain function and neurological disorders18,36. Our hypothesis was based on the previous investigations that focal ischemia evokes a sudden loss of membrane potentials (anoxic depolarization) in neurons within the ischemic core or ischemic penumbra37,38. The excitotoxicity is characterized by hyperexcitable neurons and cell death in the absence of oxygen and glucose, which can be reversed by a sodium channel blocker named dibucaine39.

Based on literature findings18,40, IL-4 binds to IL-4R for functioning (Fig. 6). IL-4 deficiency may change gene transcriptions, downregulating Kcnn4 gene encoding KCa3.1 protein and Gabra6 gene encoding GABAA receptor chloride channel, and upregulating Scna1 gene encoding Nav1.1 channel through IL-4 signaling pathways. Downregulation of KCa3.1 channels reduces potassium outflow, resulting in hyperexcitable with a larger mAHP slope, and decreased tonic GABAA receptors expression reduces chloride inflow, thus leading to enhanced neuronal firings through membrane depolarization. In addition, the upregulation of Nav1.1 channels can increase sodium inflow into cortical neurons. All these alterations are likely to enhance neuronal excitability and glutamate release from excitatory axonal terminals, ultimately accentuating susceptibility to ischemic injury. Conversely, enhancement of IL-4 signaling through supplemental IL-4 can rescue the expressions of these ion channels, reverse the neuronal excitability and protect against ischemic injury (Fig. 6). These findings support the view that anti-inflammatory IL-4 can protect brains against ischemic injury and promote recovery after ischemic injury9,10,41.

Figure 6.

A proposed molecular mechanism underlying increased neural excitabilities and susceptibility to ischemic injury caused by IL-4 deficiency. IL-4 binding to IL-4R actives IL-4 pathway. IL-4 deficiency alters gene transcriptions by downregulating the Kcnn4 gene encoding KCa3.1 protein and Gabra6 gene encoding GABAA receptor chloride channel and upregulating the Scna1 gene encoding Nav1.1 protein through IL-4 signaling pathways. Downregulation of KCa3.1 channels and tonic GABAA receptors can reduce potassium outflow and chloride inflow in neurons, leading to enhanced neuronal firings through membrane depolarization. The upregulation of Nav1.1 channels can increase sodium inflow in neurons. All these alterations can enhance neuronal hyperexcitability and glutamate release from excitatory axon terminals, ultimately increasing susceptibility to ischemic injury. Conversely, enhancement of IL-4 signaling through supplemental IL-4 can increase KCa3.1 and α6 subunit of GABAA receptors in cortical neurons and reverse neuronal hyperexcitability, thus exerting neuroprotection against ischemic injury.

Previous findings have shown that anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-4 induce neurogenesis42, promote axonal outgrowth to form new connections7,43 and modulate synaptic plasticity44. Similar to those findings, our findings reveal IL-4 deficiency leads to repetitive firings, enhanced miniature excitatory transmissions and more susceptibility to ischemic injury, thus supplementing or boosting IL-4 level may decrease neuronal firings and neural network activities, which should be beneficial for functional recovery after ischemic injury. Ion channels are essential for neuronal excitability45. In neurons, an excess of sodium influx can reduce membrane potential and lead to cytotoxic edema, and intracellular calcium overload can also trigger a series of pathological events that ultimately result in neuronal apoptosis as well as necrotic death1. Previous reports demonstrate that IL-4 upregulates KCa3.1, Kv1.3 and Kir2.1 expressions in microglia through IL-4R signaling pathway18,46. IL-4 binding to IL-4R reduces pro-inflammatory cytokine production or alters potassium channel expressions such as KCa3.1, Kv1.3 and Kir2.1 channels that play protective roles in neuroinflammation46. KCa3.1 channel also contributes to AHPs in neurons expressing IL-4 receptors19. Consistent with those investigations, our data show that IL-4 deficiency causes downregulation of KCa3.1 channel and changes of mAHP slope, thus helping lead to increased neuronal excitability.

GABAA receptors regulate neuronal excitability by local inhibitory controls, which are classified as phasic and tonic inhibitions47. Tonic inhibition (i.e., mediated by α4, α5, α6, and δ), but not phasic inhibition (mediated by α1, α3, and γ2), induced by GABAA currents contributes to RMP48. Our findings show the downregulation of the tonic α6 subunit, which can be reversed after supplement of IL-4 in both Il-4−/− and Il-4+/+ neurons. The depolarized RMP of Il-4−/− neurons is at least partially due to the downregulation of tonic α6 subunit of GABAA receptors, which is consistent with the observation that IL-1 augments GABAA receptor function and reduces the excitability of neocortical neurons49.

Voltage-gated Nav1.1 channel participates in controlling not only neuronal RMP but also threshold potential50,51. Nav1.1 is mainly expressed in GABAergic inhibitory interneurons rather than excitatory neurons52. Under normal physiological conditions, inhibitory GABAergic interneurons are more excitable than excitatory neurons to maintain the balance of neural network excitability53. During or after cerebral ischemia injury, it is likely that the upregulation of Nav1.1 induced by IL-4 deficiency causes GABAergic interneurons hyperexcitable and more susceptible to death than excitatory neurons during ischemia injury. Therefore, the decreased GABA release resulted from a decreased number of GABAergic interneurons will further reduce the inhibitory control over excitatory neurons, causing damage to the balance of network excitability, thus resulting in exacerbation of excitotoxicity.

5. Conclusions

Our findings reveal a previously unknown mechanism by which IL-4 deficiency causes neural hyperexcitability and enhances neuronal excitatory transmissions. IL-4 deficiency leads to an increased vulnerability to ischemic injury. Conversely, supplemental IL-4 reduces neuronal firing and neural network activities, and increases neuronal viability as well. Our data support the view that IL-4 plays a neuroprotective role in ischemia and reperfusion injury. Therefore, supplementing IL-4 might be beneficial for improvement of functional recovery after brain ischemia injury6,9, 10, 11.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81573410), the National Science and Technology Major Project (2018ZX09711001-004-006, China) and the Natural Sciences Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2015QL008, China) awarded to Kewei Wang. Xiaoling Chen is grateful to Chenyu Zhang and Xueqin Jin for the help in Western blot experiments and patch clamp recordings of IL-4 supplementary brain slices, respectively.

Author contributors

Xiaoling Chen and Jingliang Zhang carried out the experiments by collecting and analyzing the data, and also drafted the manuscript. Yan Song and Pan Yang assisted in some experiments. Yang Yang and Zhuo Huang supervised this project. Kewei Wang supervised the project and finalized the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest in this study.

Footnotes

Peer review under the responsibility of Chinese Pharmaceutical Association and Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences.

Supporting data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2020.05.002.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Chen X.L., Wang K.W. The fate of medications evaluated for ischemic stroke pharmacotherapy over the period 1995–2015. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2016;6:522–530. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2016.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hossmann K.A. Periinfarct depolarizations. Cerebrovasc Brain Metab Rev. 1996;8:195–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lan X., Han X., Li Q., Yang Q.W., Wang J. Modulators of microglial activation and polarization after intracerebral haemorrhage. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:420–433. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xing C.H., Wang X.S., Cheng C.J., Montaner J., Mandeville E., Leung W. Neuronal production of lipocalin-2 as a Help-Me signal for glial activation. Stroke. 2014;45:2085–2092. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han Y., Chen X., Shi F., Li S., Huang J., Xie M. CPG15, a new factor upregulated after ischemic brain injury, contributes to neuronal network re-establishment after glutamate-induced injury. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:722–731. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao X., Wang H., Sun G., Zhang J., Edwards N.J., Aronowski J. Neuronal Interleukin-4 as a modulator of microglial pathways and ischemic brain damage. J Neurosci. 2015;35:11281–11291. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1685-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walsh J.T., Hendrix S., Boato F., Smirnov I., Zheng J., Lukens J.R. MHCII-independent CD4+ T cells protect injured CNS neurons via IL-4. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:699–714. doi: 10.1172/JCI76210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee H.K., Koh S., Lo D.C., Marchuk D.A. Neuronal IL-4Ralpha modulates neuronal apoptosis and cell viability during the acute phases of cerebral ischemia. FEBS J. 2018;285:2785–2798. doi: 10.1111/febs.14498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu X., Liu J., Zhao S., Zhang H., Cai W., Cai M. Interleukin-4 is essential for microglia/macrophage M2 polarization and long-term recovery after cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2016;47:498–504. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.012079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lively S., Hutchings S., Schlichter L.C. Molecular and cellular responses to interleukin-4 treatment in a rat model of transient ischemia. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2016;75:1058–1071. doi: 10.1093/jnen/nlw081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang J., Ding S., Huang W., Hu J., Huang S., Zhang Y. Interleukin-4 ameliorates the functional recovery of intracerebral hemorrhage through the alternative activation of microglia/macrophage. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:61. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang R., Lirussi D., Thornton T.M., Jelley-Gibbs D.M., Diehl S.A., Case L.K. Mitochondrial Ca2+ and membrane potential, an alternative pathway for Interleukin 6 to regulate CD4 cell effector function. Elife. 2015;4:e06376. doi: 10.7554/eLife.06376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carey G.B., Semenova E., Qi X., Keegan A.D. IL-4 protects the B-cell lymphoma cell line CH31 from anti-IgM-induced growth arrest and apoptosis: contribution of the PI-3 kinase/AKT pathway. Cell Res. 2007;17:942–955. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.2007.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J.L., Buehner M., Sebald W. Functional epitope of common gamma chain for interleukin-4 binding. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:1490–1499. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang J.L., Simeonowa I., Wang Y., Sebald W. The high-affinity interaction of human IL-4 and the receptor alpha chain is constituted by two independent binding clusters. J Mol Biol. 2002;315:399–407. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagy E., Mocsar G., Sebestyen V., Volko J., Papp F., Toth K. Membrane potential distinctly modulates mobility and signaling of IL-2 and IL-15 receptors in T cells. Biophys J. 2018;114:2473–2482. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanley P.J., Musset B., Renigunta V., Limberg S.H., Dalpke A.H., Sus R. Extracellular ATP induces oscillations of intracellular Ca2+ and membrane potential and promotes transcription of IL-6 in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9479–9484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400733101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferreira R., Lively S., Schlichter L.C. IL-4 type 1 receptor signaling up-regulates KCNN4 expression, and increases the KCa3.1 current and its contribution to migration of alternative-activated microglia. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:183. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen T.V., Matsuyama H., Baell J., Hunne B., Fowler C.J., Smith J.E. Effects of compounds that influence Ik (KCNN4) channels on afterhyperpolarizing potentials, and determination of Ik channel sequence, in Guinea pig enteric neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:2024–2031. doi: 10.1152/jn.00935.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmitteckert E.M., Prokop C.M., Hedrich H.J. DNA detection in hair of transgenic mice—a simple technique minimizing the distress on the animals. Lab Anim. 1999;33:385–389. doi: 10.1258/002367799780487922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwieger J., Esser K.H., Lenarz T., Scheper V. Establishment of a long-term spiral ganglion neuron culture with reduced glial cell number: effects of AraC on cell composition and neurons. J Neurosci Methods. 2016;268:106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Y., Adi T., Effraim P.R., Chen L., Dib-Hajj S.D., Waxman S.G. Reverse pharmacogenomics: carbamazepine normalizes activation and attenuates thermal hyperexcitability of sensory neurons due to Nav 1.7 mutation I234T. Br J Pharmacol. 2018;175:2261–2271. doi: 10.1111/bph.13935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fogarty M.J., Hammond L.A., Kanjhan R., Bellingham M.C., Noakes P.G. A method for the three-dimensional reconstruction of Neurobiotin-filled neurons and the location of their synaptic inputs. Front Neural Circ. 2013;7:153. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2013.00153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang J., Chen X., Karbo M., Zhao Y., An L., Wang R. Anticonvulsant effect of dipropofol by enhancing native GABA currents in cortical neurons in mice. J Neurophysiol. 2018;120:1404–1414. doi: 10.1152/jn.00241.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nunez J. Primary culture of hippocampal neurons from P0 newborn Rats. JoVE. 2008;(19):895. doi: 10.3791/895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kopf M., Le Gros G., Bachmann M., Lamers M.C., Bluethmann H., Kohler G. Disruption of the murine IL-4 gene blocks Th2 cytokine responses. Nature. 1993;362:245–248. doi: 10.1038/362245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu F., McCullough L.D. The middle cerebral artery occlusion model of transient focal cerebral ischemia. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1135:81–93. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-0320-7_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jingliang Zhang T.H., Liu Xiaoyan, Zhu Yuanjun, Chen Xiaoling, Liu Ye, Wang Yinye. 002C-3 protects the brain against ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibiting autophagy and stimulating CaMKK/CaMKIV/HDAC4 pathways in mice. J Chin Pharmaceut Sci. 2016;25:598–604. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackman K., Kunz A., Iadecola C. Modeling focal cerebral ischemia in vivo. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;793:195–209. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-328-8_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu Z., Bian X., Liu X., Zhu Y., Zhang X., Chen S. Honokiol protects brain against ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats through disrupting PSD95–nNOS interaction. Brain Res. 2013;1491:204–212. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guan L., Song Y., Gao J., Gao J., Wang K. Inhibition of calcium-activated chloride channel ANO1 suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis of epithelium originated cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7:78619–78630. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy T.H., Corbett D. Plasticity during stroke recovery: from synapse to behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:861–872. doi: 10.1038/nrn2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gloveli T., Schmitz D., Heinemann U. Interaction between superficial layers of the entorhinal cortex and the hippocampus in normal and epileptic temporal lobe. Epilepsy Res. 1998;32:183–193. doi: 10.1016/s0920-1211(98)00050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lai H.C., Jan L.Y. The distribution and targeting of neuronal voltage-gated ion channels. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:548–562. doi: 10.1038/nrn1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Szucs A., Rubakhin S.S., Stefano G.B., Hughes T.K., Rozsa K.S. Interleukin-4 potentiates voltage-activated Ca-currents in Lymnaea neurons. Acta Biol Hung. 1995;46:351–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joshi I., Andrew R.D. Imaging anoxic depolarization during ischemia-like conditions in the mouse hemi-brain slice. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:414–424. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.1.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bures J., Buresova O. Anoxic terminal depolarization as an indicator of cerebral cortex vulnerability in anoxia & ischemia. Pflugers Arch für Gesamte Physiol Menschen Tiere. 1957;264:325–334. doi: 10.1007/BF00364173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Douglas H.A., Callaway J.K., Sword J., Kirov S.A., Andrew R.D. Potent inhibition of anoxic depolarization by the sodium channel blocker dibucaine. J Neurophysiol. 2011;105:1482–1494. doi: 10.1152/jn.00817.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelly-Welch A.E., Hanson E.M., Boothby M.R., Keegan A.D. Interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 signaling connections maps. Science. 2003;300:1527–1528. doi: 10.1126/science.1085458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xiong X., Barreto G.E., Xu L., Ouyang Y.B., Xie X., Giffard R.G. Increased brain injury and worsened neurological outcome in interleukin-4 knockout mice after transient focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2011;42:2026–2032. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.593772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Butovsky O., Ziv Y., Schwartz A., Landa G., Talpalar A.E., Pluchino S. Microglia activated by IL-4 or IFN-gamma differentially induce neurogenesis and oligodendrogenesis from adult stem/progenitor cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;31:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vidal P.M., Lemmens E., Dooley D., Hendrix S. The role of "anti-inflammatory" cytokines in axon regeneration. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2013;24:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li Q., Qi F., Yang J., Zhang L., Gu H., Zou J. Neonatal vaccination with bacillus Calmette-Guerin and hepatitis B vaccines modulates hippocampal synaptic plasticity in rats. J Neuroimmunol. 2015;288:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2015.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aldrich R. Molecular biophysics: ionic channels of excitable membranes. Science. 1985;228:867–868. doi: 10.1126/science.228.4701.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nguyen H.M., Grossinger E.M., Horiuchi M., Davis K.W., Jin L.W., Maezawa I. Differential Kv1.3, KCa3.1, and Kir2.1 expression in "classically" and "alternatively" activated microglia. Glia. 2017;65:106–121. doi: 10.1002/glia.23078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walker M.C., Semyanov A. Darlison MG editor. Inhibitory regulation of excitatory neurotransmission. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; Heidelberg: 2008. Regulation of excitability by extrasynaptic GABAA receptors; pp. 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu J.C., Hsiao Y.T., Chiang C.W., Wang C.T. GABAA receptor-mediated tonic depolarization in developing neural circuits. Mol Neurobiol. 2014;49:702–723. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8548-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miller L.G., Galpern W.R., Dunlap K., Dinarello C.A., Turner T.J. Interleukin-1 augments gamma-aminobutyric acidA receptor function in brain. Mol Pharmacol. 1991;39:105–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bean B.P. The action potential in mammalian central neurons. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:451–465. doi: 10.1038/nrn2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bennett D.L., Clark A.J., Huang J., Waxman S.G., Dib-Hajj S.D. The role of voltage-gated sodium channels in pain signaling. Physiol Rev. 2019;99:1079–1151. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00052.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lorincz A., Nusser Z. Cell-type-dependent molecular composition of the axon initial segment. J Neurosci. 2008;28:14329–14340. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4833-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cantu D., Walker K., Andresen L., Taylor-Weiner A., Hampton D., Tesco G. Traumatic brain injury increases cortical glutamate network activity by compromising GABAergic control. Cerebr Cortex. 2015;25:2306–2320. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhu041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.