Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

To inform the patient-centered discussion regarding comparative outcomes with irritable bowel syndrome/chronic idiopathic constipation pharmacotherapy, we evaluated reasons and timing of discontinuation of FDA-approved pharmacotherapy for irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation in a large observational real-world cohort.

METHODS:

We identified patients initiating lubiprostone or linaclotide within the University of Michigan Electronic Medical Record (2012–2016). Medication start and stop dates were determined in manual chart review including detailed review of all documentation including office notes and telephone encounters. A Cox model was constructed to predict the hazard of discontinuation.

RESULTS:

On multivariate analysis of 1,612 patients, linaclotide users had a lower risk of discontinuing therapy than lubiprostone users for any reason (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.6, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.5–0.8). At 3 and 12 months, the overall discontinuation rates were 23% and 43% for lubiprostone compared with 14% and 24% for linaclotide. Over the first year of therapy, more than half of discontinuations due to intolerance occurred in the first 3 months for both drugs. Linaclotide users were more likely to discontinue due to intolerance (HR = 1.6 [95% CI, 1.2–2.3]) but less likely to discontinue due to insufficient efficacy of therapy (HR = 0.5 [95% CI, 0.4–0.8]). IBS diagnosis increased the hazard of discontinuation of lubiprostone relative to linactolide (HR = 1.4, 95% CI, 1.1–1.6). Loss of prescription drug coverage remained a common reason for discontinuation over the first year of therapy.

DISCUSSION:

Individuals appear more likely to discontinue lubiprostone than linaclotide overall, but more likely to discontinue linaclotide compared with lubiprostone due to intolerance (mostly diarrhea). Most discontinuations due to intolerance occur in the first 3 months. These results may be useful in individualized treatment selection and enhancing patient knowledge regarding long-term outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

Constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-C) and chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC) are common and often debilitating conditions which can affect quality of life similarly to rheumatoid arthritis or heart failure (1–3). As IBS-C and CIC are chronic and incurable, the goal of long-term treatment remains symptom relief. Prescription drug therapy is efficacious in managing IBS-C/CIC, based on clinically significant improvements in symptoms of abdominal pain and constipation in several well-conducted clinical trials (4). However, efficacy in 12-week clinical trials is not the same as long-term effectiveness in clinical practice (5,6). To maintain long-term relief of symptoms, individuals with IBS-C/CIC must continue to take their medications on a regular basis (7). Discontinuation of therapy results in a return of symptoms for which these individuals originally sought care because of the relatively short-term effects of current drug therapies (8,9).

The patient-centered decision to discontinue drug therapy is an important binary clinical outcome in the long-term management of these chronic conditions such as IBS-C and CIC (10). Symptom relief (i.e., efficacy in a clinical trial) must be balanced on an ongoing basis against factors such as side effects (11) and medication cost (12–14). When discontinuing therapy, the patient and/or provider inherently places greater weight on the overall risk or cost associated with remaining on therapy, compared with disease burden of returning to their baseline symptom severity associated with untreated IBS-C or CIC (15). In other words, the patient and/or provider would rather have untreated IBS-C/CIC (and then seek alternative treatment) than continue drug therapy. Despite the importance of understanding treatment discontinuation to patients and providers, little is known about treatment discontinuation in IBS-C/CIC outside of clinical trials (16).

To better inform the patient-centered discussion regarding potential long-term outcomes in prescription drug treatment of IBS-C/CIC, we aimed to evaluate the duration of therapy until discontinuation, reasons for medication discontinuation, and clinical factors leading to discontinuation for approved pharmacotherapies for IBS-C and CIC in clinical practice.

METHODS

Database search and exclusion criteria

A retrospective cohort study was conducted in accordance with the ISPOR checklist for medication persistence studies (17) and STROBE checklist for cohort studies. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained before initiation of the study. Individuals were identified using the Michigan Medicine Electronic Medical Record Search Engine information retrieval system between December 2012 and November 2016. This system links outpatient and inpatient provider encounter documentation, administrative claims data, and medication prescription data across the Michigan Medicine healthcare system (18). Specifically, patients who were prescribed lubiprostone before linaclotide was available (December 2012 in the Michigan Medicine health system) were excluded due to confounding by a potential change in practice patterns. Selection criteria included (i) age over 18 years, (ii) new initiation of linaclotide or lubiprostone therapy, and (iii) at least 1 documented outpatient office visit after medication initiation. We required at least 1 additional office visit after medication initiation, to ensure adequate follow-up which is needed to correctly identify medication persistence. Exclusion criteria included previous use of either lubiprostone, linactolide, or enrollment in an IBS-C clinical trial. Notably, plecanatide was not included because there was minimal use in our health system for the duration of this study.

Demographics and disease classifications

Patient- and encounter-specific demographics including gender and age at medication initiation were extracted. IBS-C diagnosis was determined using validated case definitions of IBS in administrative claims data sets (International Classification of Diseases-9 billing codes for IBS and/or abdominal pain in a single outpatient encounter: 564.1, 388.⋆(19)). Individuals not meeting the case definition for IBS were classified as having CIC, consistent with US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) labeling as well as usual clinical practice for lubiprostone and linaclotide which is generally limited to these 2 indications. The specialty of the prescriber initiating the IBS-C/CIC therapy was extracted and classified as gastroenterology specialty or nongastroenterology specialty.

Medication persistence and discontinuation assessment

Consistent with the standard definition of medication persistence (defined by ISPOR Medication Adherence and Persistence Special Interest Group as the “the act of continuing the treatment for the prescribed duration”) (20), we assessed “duration of therapy until discontinuation” as the length of time between (i) initial prescription by the provider and (ii) the date that the patient or provider reported stopping treatment altogether. Importantly, medication persistence is distinct from medication adherence, which is defined separately as “the extent to which a patient acts in accordance with the prescribed interval” (20). The patient-reported date of stopping therapy was preferred, if available in the medical record. Dates of starting and stopping therapy were manually extracted from office notes, telephone notes, and other documented communications. Results were corroborated with medication prescription and refill records in the electronic health record; however, clinical documents served as the ground truth to account for outside provider prescriptions, refills, and discontinuations.

Rate of discontinuation was determined at 3-, 6-, and 12-month timepoints after initiation of therapy. The 3-month timepoint was important for 2 reasons: (i) consistency with evaluating discontinuation after an initial 90-day prescription and (ii) consistency with the length of recent registered phase III clinical trials leading to IBS-C/CIC drug approvals (21). Six- and 12-month timepoints correspond to pragmatic lengths of medication fills in clinical practice of managing stable IBS-C/CIC.

Reasons for discontinuation were broadly categorized as due to intolerance, perceived lack or loss of efficacy, financial cost of prescription fills, or sufficient improvement in the underlying IBS-C/CIC no longer necessitating drug treatment. Reasons for discontinuation were pooled among individuals who discontinued therapy within the first 3 months (termed early discontinuations) consistent with an initial 90-day prescription fill and individuals who discontinued therapy between 3 and 12 months (termed delayed discontinuations).

Statistical analysis

Categorical and continuous variables were defined using mean values and SDs and compared between medication groups using the Fisher χ2 and Student t test. Unadjusted rates of discontinuation between linaclotide and lubiprostone at 3, 6, and 12 months were compared using the Student t test (see Table 2, Supplementary Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/AJG/B387). Kaplan-Meier survival plots were constructed, stratified by drug, to visualize the risk of discontinuation over time (i) for any reason or (ii) specifically due to intolerance. Cox-proportional hazards methods were used to model medication persistence, in-corporating demographic, provider type, concominate medication use, and codiagnoses. The proportionality assumption was checked for each variable by assessing linear time-by-covariate interactions for each covariate. A log-rank test was used to determine whether reasons for discontinuation differed between early and late discontinuation periods. Statistical analysis was conducted using STATA version 14.0 (STATACorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Study population

We identified 679 patients on lubiprostone therapy and 933 on linaclotide therapy who met eligibility criteria and were included in the overall cohort. Baseline characteristics are reported in Table 1. The average length of follow-up within the medical record was 2.5 years (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.4–2.7 years; range 2 days to 10.0 years) for lubiprostone and 1.2 years (95% CI, 1.1–1.3 years; range 2 days to 3.7 years) for linaclotide. In contrast to individuals prescribed linaclotide, individuals who were prescribed lubiprostone were younger, were more likely to be female, and were more likely to have IBS-C as opposed to CIC in the study cohort. There were significant differences between lubiprostone and linaclotide cohorts on several demographic variables including average length of follow-up, gender distribution, and the proportion of individuals with IBS-C vs CIC.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics stratified by drug

| Characteristic | Lubiprostone cohort (n = 679) | Linaclotide cohort (n = 933) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, yr (SD) | 48.6(17.8) | 49.9 (16.4) | 0.13 |

| Female gender | 586/679 (86.3%) | 760/933 (81.5%) | 0.01 |

| Proportion of individuals with IBS-C (vs CIC) | 492/679 (72.5%) | 225/933 (24.1%) | <0.001 |

| Managed by gastroenterology | 599/679 (88.2%) | 821/933 (88.0%) | 0.89 |

CIC, chronic idiopathic constipation; IBS-C, constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome.

Comparative risk of discontinuing lubiprostone or linaclotide therapy

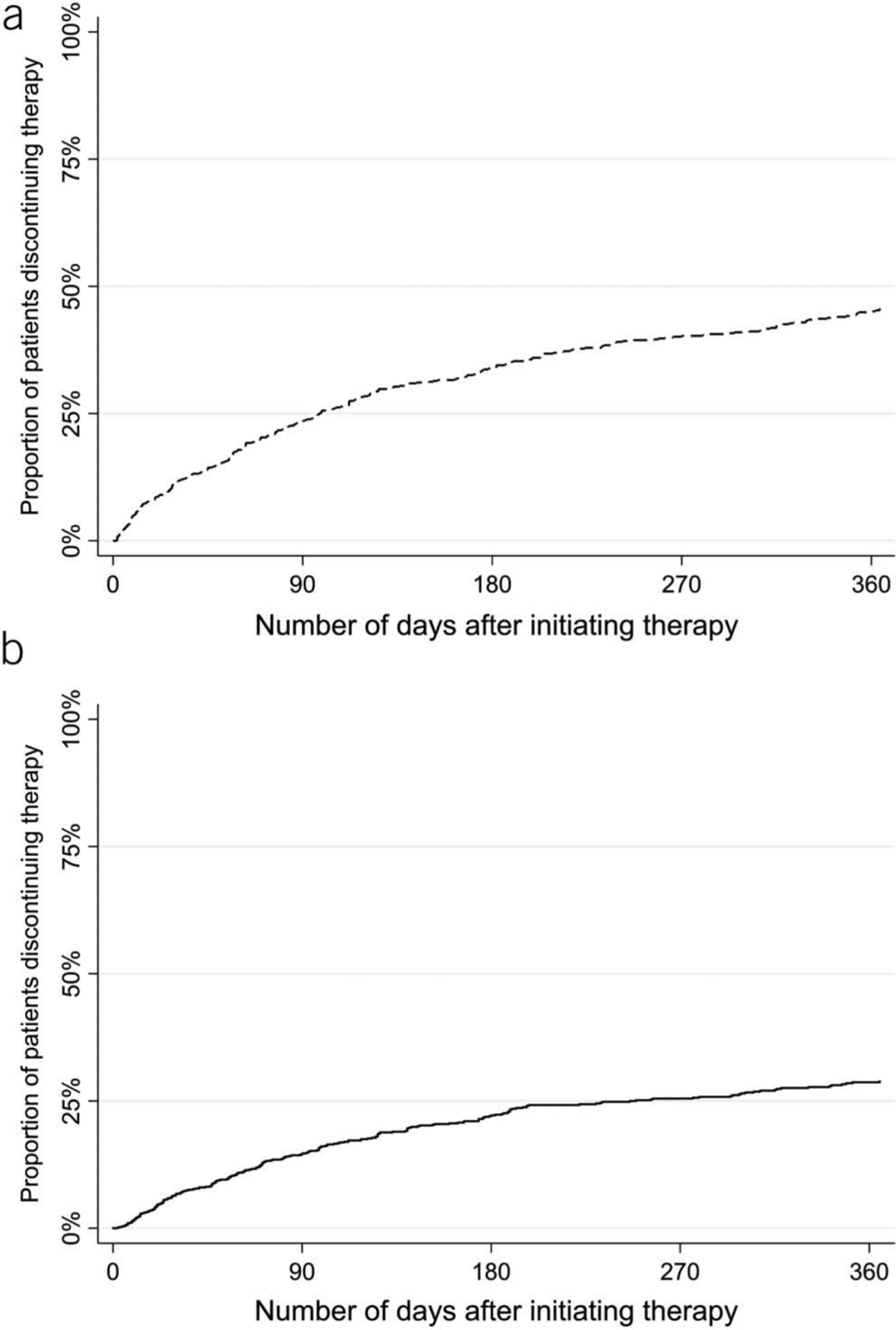

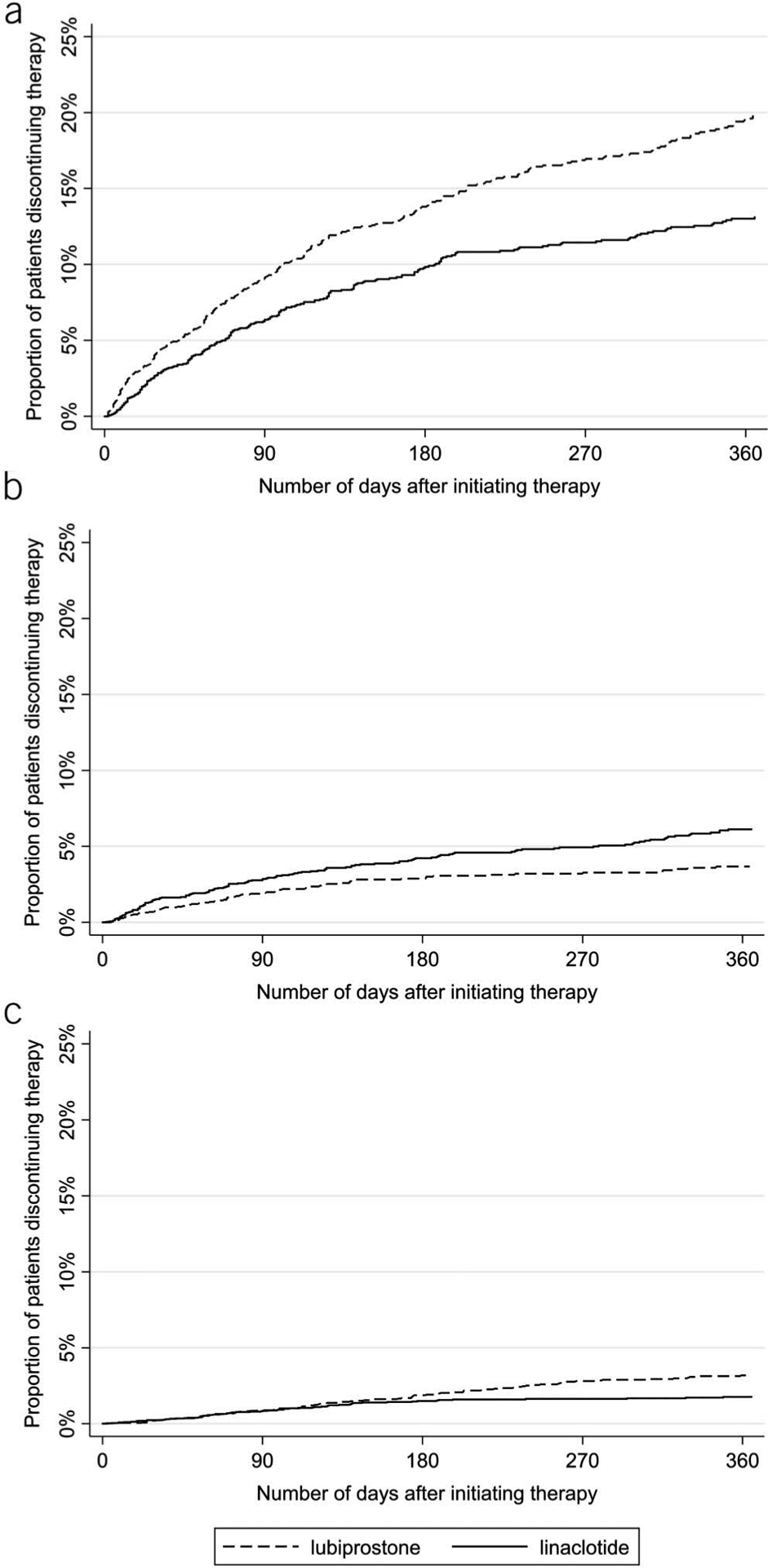

On unadjusted analysis, the overall rates of discontinuation on lubiprostone therapy were 23.6% (95% CI, 20.5–27.0) at 3 months, 33.8% (95% CI, 30.4–37.6) at 6 months, and 45.7% (95% CI, 41.8–49.7) at 12 months. On linaclotide, the rates of discontinuation were 14.7% (95% CI, 12.5–17.2) at 3 months, 22.2% (95% CI, 19.5–25.2) at 6 months, and 28.9% (95% CI, 25.7–32.3) at 12 months (Figure 1). On multivariable analysis adjusting for demographic variables (age, gender, presence of IBS-C [vs CIC], and management of therapy by gastroenterology [vs nongastroenterology]), linaclotide users had a lower risk of discontinuation relative to lubiprostone users (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.64, 95% CI, 0.54–0.77) (Figure 2). Linaclotide users also had a lower risk of discontinuation due to insufficient efficacy compared with lubiprostone (HR = 0.57, 95% CI, 0.41–0.77). However, patients were more likely to discontinue linaclotide due to intolerance compared with lubiprostone (HR = 1.93, 95% CI, 1.44–2.57). These findings were consistent across unadjusted, age- and gender-adjusted, and multivariable analyses (Table 2). The full multivariable model as well as univariate analyses are presented in Table 1 (Supplementary Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/AJG/B387).

Figure 1.

Unadjusted risk of discontinuing therapy. The unadjusted risks of discontinuing lubiprostone (a) or linaclotide (b) are presented using a Kaplan-Meier curves.

Figure 2.

Adjusted risk of discontinuing therapy stratified by reason for discontinuation. The multivariable model was adjusted for age, gender, diagnosis of constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (vs chronic idiopathic constipation), and management of therapy by gastroenterology (vs nongastroenterology). Results are presented as: risk of discontinuation for any reason (a), risk of discontinuation due to intolerance (b), and risk of discontinuation due to insufficient efficacy of therapy (c). Adjusting for covariates, individuals were more likely to discontinue lubiprostone for any reason or due to insufficient efficacy as reported by the patient or provider. Individuals were more likely to discontinue therapy due to intolerance with linaclotide.

Table 2.

Risk of discontinuing linaclotide compared with lubiprostone for any reason, due to intolerance, or due to insufficient efficacy

| Reason for discontinuation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any reason | Intolerance | Insufficient efficacy | ||||

| Drug | Lubiprostone | Linaclotide | Lubiprostone | Linaclotide | Lubiprostone | Linaclotide |

| N | 679 | 933 | 679 | 933 | 679 | 933 |

| Patient-days on therapy | 628,661 | 419,716 | 628,661 | 419,716 | 628,661 | 419,716 |

| HR of discontinuation (95% CIs) | ||||||

| Age- and gender-adjusted | reference | 0.596 (0.510–0.697) (P<0.001) | reference | 1.803 (1.384–2.350) (P < 0.001) |

reference | 0.519 (0.391–0.689) (P < 0.001) |

| Multivariable model | reference | 0.644 (0.540–0.768) (P<0.001) | reference | 1.926 (1.442–2.574) (P < 0.001) |

reference | 0.565 (0.412–0.775) (P < 0.001) |

| Unadjusted | reference | 0.598 (0.511–0.699) (P<0.001) | reference | 1.796 (1.379–2.339) (P < 0.001) |

reference | 0.520 (0.392–0.690) (P < 0.001) |

Risk is presented using HRs. The overall risk of discontinuing linaclotide, and the risk of discontinuing linaclotide due to insufficient efficacy, was lower compared with lubiprostone. The risk of discontinuing linaclotide due to intolerance was higher compared with lubiprostone. Results were concordant in unadjusted, age/gender-adjusted, and multivariable analyses.

Multivariable model adjusted for age, gender, diagnosis of constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (vs chronic idiopathic constipation), and management by gastroenterology (vs nongastroenterology).

CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

Reasons for discontinuation of IBS-C or CIC therapy

Reasons for discontinuation within the first year of therapy are reported for lubiprostone and linaclotide (Table 3). The most common reasons for discontinuation were intolerance, loss of prescription drug coverage, and insufficient efficacy derived from therapy. The most common reasons for early discontinuation of lubiprostone due to intolerance were nausea (41% of early lubiprostone discontinuations due to intolerance), followed by abdominal pain (27%) and diarrhea (12%). Diarrhea (53%) was the most common reason for early discontinuation of linaclotide due to intolerance, followed by abdominal pain (25%) and bloating (8%). Nausea remained the most reason for late discontinuation due to intolerance on lubiprostone (50% of late lubiprostone discontinuations due to intolerance), while diarrhea remained the most common reason for late discontinuation of linaclotide due to intolerance (65% of late linaclotide discontinuations due to intolerance).

Table 3.

Reasons for discontinuation of chronic lubiprostone or linaclotide therapy among those stopping therapy during the first year of use

| Reason for discontinuation | Lubiprostone (n = 679) | Linaclotide (n = 933) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discontinuation within 3 mo of initiating therapy (n = 157), % | Discontinuation between 3–12 mo of initiating therapy (n = 134), % | P-value | Discontinuation within 3 mo of initiating therapy (n = 128), % | Discontinuation between 3–12 mo of initiating therapy (n = 97), % | P value | |

| No longer needed | 0.0 | 0.0 | No events | 3.1 | 1.0 | <0.001 |

| Insufficient efficacy | 16.6 | 39.6 | <0.001 | 25.0 | 23.7 | <0.001 |

| Insurance noncoverage | 42.7 | 17.9 | <0.001 | 8.6 | 9.3 | <0.001 |

| All adverse events | 26.1 | 17.9 | <0.001 | 57.0 | 50.5 | <0.001 |

| Diarrhea | 3.2 | 5.2 | <0.001 | 30.5 | 33.0 | <0.001 |

| Nausea | 10.8 | 9.0 | <0.001 | 0.0 | 0.0 | No events |

| Abdominal pain | 7.0 | 2.2 | <0.001 | 14.1 | 10.3 | <0.001 |

| Abdominal bloating or discomfort | 0.0 | 0.0 | No events | 4.7 | 3.1 | 0.002 |

| Other adverse event | 5.1 | 1.5 | Not applicable | 7.8 | 4.1 | Not applicable |

| Not reported | 14.6 | 24.6 | Not applicable | 6.3 | 15.5 | Not applicable |

The risk of discontinuing therapy due to insufficient efficacy, loss of insurance coverage, intolerance, or no longer needing therapy decreased among individuals who remained on drug therapy for at least 3 months. Percentages reflect the portion of patients discontinuing for each stated reason compared with all individuals discontinuing therapy within the specified timeframe.

Lack of prescription drug coverage was a common reason for early discontinuation of lubiprostone (43% of all discontinuations), compared with 9% of early discontinuations of linaclotide. Subsequent loss of prescription drug coverage (after initial prescription drug coverage) continued to account for 18% of lubiprostone and 9% of linaclotide discontinuations over the remaining year. Insufficient efficacy of therapy accounted for 25% of linaclotide and 17% of lubiprostone discontinuations within the first 3 months, regardless of on- or off-label dose titration. Over half of discontinuations due to lack of efficacy occurred within the first 3 months of starting linaclotide, while most discontinuations due to insufficient lubiprostone efficacy occurred after the first 3 months of therapy. Patients rarely reported no longer needing drug therapy due to improvement in underlying IBS-C/CIC symptom severity, with only 5 patients on linaclotide discontinuing therapy within the first year for this reason.

Dose adjustment can mitigate treatment discontinuation

Forty-four of the 933 patients adjusted their linaclotide dose after starting therapy, enabling 23 of these patients to remain on linaclotide for at least 1 year and avoid treatment discontinuation. Despite dose adjustment, 15 of these 44 patients ultimately discontinued therapy due to diarrhea within the first year of therapy while the remaining 6 patients discontinued for other reasons.

Only 2 patients in the lubiprostone cohort adjusted their dose within the first year of treatment, precluding meaningful analysis on whether dose adjustment could mitigate treatment discontinuation. However, neither of the 2 patients discontinued therapy at 1 year.

Treatment discontinuation based on likelihood of having IBS-C or CIC

Treatment discontinuation by 3 months for any reason was higher among patients with IBS-C compared with CIC for linaclotide (21.3% for IBS-C patients on linaclotide, compared with 13.8% for CIC, P = 0.01) but not lubiprostone (25.5% of IBS-C patients on lubiprostone, compared with 20.8% for CIC, P = 0.21). By contrast, there was no longer a significant difference in the rate of linaclotide discontinuation at 1 year based on whether a patient had IBS-C or CIC (P = 0.57). IBS-C patients were more likely to discontinue lubiprostone at 1 year (53.1%) compared with CIC patients (41.0%) (P = 0.009). The reasons for these findings were likely complex. There were nonsignificant trends toward long-term insurance coverage issues for patients with IBS-C as opposed to CIC regardless of drug treatment, understanding that these subanalyses had small sample sizes. There was no clear evidence of differences in discontinuation due to adverse events (P > 0.20 for all subanalyses) to explain these findings.

DISCUSSION

We evaluated comparative discontinuation rates and reasons for discontinuation for FDA-approved IBS-C/CIC pharmacotherapy in 1,612 patients covering 1,048,377 patient-days of therapy. Roughly one-eighth to one-quarter of patients discontinued therapy within 3 months, and one-quarter to two-fifths of patients discontinued therapy within 1 year. The overall risk of discontinuation was lower for linaclotide compared with lubiprostone. Although the risk of discontinuation was higher with lubiprostone due to either patient-reported medication ineffectiveness or loss of insurance coverage, the risk of discontinuation due to intolerance was greater with linaclotide. Results were robust in both unadjusted and in age- and gender-adjusted analyses.

Discontinuation is an objective outcome which captures the point at which a patient or provider would rather return to the original severity of IBS-C or CIC (or seek alternative therapy) than continue therapy. To maintain clinically significant improvement in symptoms, IBS-C/CIC patients require continued pharmacotherapy. A previous systematic review found that adverse events and discontinuation related to adverse events are not infrequent in IBS clinical trials (16); however, a summary of reasons for discontinuation and timing of discontinuation has not been previously reported outside of clinical trials. In the present large observational study, we found that medication ineffectiveness and loss of insurance coverage are major reasons for discontinuation in clinical practice in addition to intolerance. Although IBS symptoms naturally wax and wane irrespective of therapy (1), natural improvement in underlying IBS-C/CIC severity was not a major reason for drug discontinuation in our study.

Intolerance and medication ineffectiveness were common reasons for drug discontinuation in this analysis on both therapies. The higher risk of discontinuation due to intolerance and lower risk of discontinuation due to patient-reported ineffectiveness on linaclotide may be due to “potency.” In clinical trials, IBS therapies with greater frequency of adverse events appear to have higher patient-reported efficacy (22). Thus, it is possible that patients might feel a drug working if it is associated with mild adverse events. Modifiable factors which might generally affect perceived effectiveness and risk of discontinuation include dosing schedule and strength, and frequency of clinic visits (7,23,24). Providers have little opportunity to modify the dosing schedule within FDA labeling instructions: Lubiprostone is a twice-daily medication, compared with once-daily dosing of both linaclotide and plecanatide in IBS-C/CIC. However, multiple dosing strengths are available for linaclotide and lubiprostone, which could potentially improve the ability for clinicians to balance long-term efficacy and tolerability and decrease the risk of discontinuation (21). Finally, discontinuation of treatment due to loss of insurance coverage is a critical problem in chronic disease management because discontinuation of effective therapy may lead to increased healthcare utilization related to greater burden of illness. Thus, our findings highlight the need for providers and patients to maintain vigilance for prescription drug coverage problems which likely have profound impact in clinical practice.

Optimizing individual patient response to pharmacotherapy might help to contain the costs of undertreated constipation exceeding $1.6 billion annually in the United States (25,26) and to improve the significant detriment to quality of life affecting this patient population (27). In the absence of a viable biomarker in IBS-C or CIC to predict patient response, primary endpoints in clinical studies evaluating drug effectiveness remain limited to symptom assessment (28–30). Previous attempts to phenotype positive responders to linaclotide pharmacotherapy on the basis of symptoms had limited success (31). The complications arising with a symptom-based approach are at least 2-fold. First, natural history of symptoms in patients with functional disorders waxes and wanes (32) which limits the development of a stable phenotype within the individual patient. Second, there is significant overlap and prevalence of multiple gastrointestinal symptoms even among patients with classically lower abdominal functional syndromes (28,33,34) which make stratification of specific symptoms into phenotypes more difficult from a research standpoint.

Large data sets offer an opportunity to better discriminate individual predictors of therapeutic response but are rarely tied longitudinally to validated symptom assessments which are cumbersome and costly to evaluate. An ideal outcome measure for population-level claims data analysis would consistently and objectively stratify subsets of patients across healthcare systems and payer models. Discontinuation is a binary and clinically important outcome measure which may provide a solution to the lack of viable outcome instruments for administrative claims data analyses, based on patient-level data in this study which validate reasons for discontinuation of IBS-C/CIC pharmacotherapy.

A number of important limitations should be considered in interpreting results. First, single-center design can impact censoring which may not be independent of reasons for discontinuation. Some discontinuations may not be captured because local physicians may take over prescription for patients who only seek tertiary care for 1 or 2 visits. However, it is important to note that our database encompasses the breadth of a large healthcare system as well as the quaternary referral center, and average length of follow-up exceeded 1 year supporting validity of our findings. Moreover, our manual review of referral notes which document the intended length of therapy supplants the need to review prescription refill data by local primary care providers. We furthermore excluded patients with only 1 encounter in the system. Furthermore, we censored length of treatment for patients who left our center and did not count these cases as drug discontinuations. Another limitation relates to possible “confounding by indication” for linaclotide and lubiprostone in claims data set analyses. Because the perception of disease severity may influence the choice of initial dosing in practice, characterization of individual dosing strengths for linaclotide or lubiprostone may have less relevance to individual practitioners. Instead, the focus of our study is on the choice of therapy, allowing for dose adjustments as needed. Despite these choices toward optimizing study design, it remains possible that clinical perceptions on the appropriateness of lubiprostone or linaclotide based on disease severity may impact our findings, and that clinical perceptions of these treatments likely vary in practice. Unlike medications for IBS with diarrhea such as tricyclic antidepressants or rifaximin, both linaclotide and lubiprostone have limited indication for chronic constipation disorders and IBS with constipation. Moreover, recent literature suggest that IBS-C and CIC may be variants of the same overall illness rather than separate disease entities (33,34). In all analyses, patients with a high suspicion of IBS-C based on validated sets of International Classification of Diseases-9 codes consistently discontinued pharmacotherapy more frequently than those with a low suspicion of IBS-C. These billing codes were readily available to providers when therapy was initiated—identification of these patients in the electronic records system may obviate the need for symptom-based risk assessments for discontinuation; however, such an approach remains to be validated prospectively.

We characterized reasons and rates for discontinuation of IBS-C/CIC pharmacotherapy in a large observational cohort of patients encompassing >1,000,000 patient-days of follow-up and average length of follow-up exceeding 1 year. Discontinuation is a clinically important outcome in IBS-C and CIC, and reasons and rates of discontinuation can differ among IBS-C/CIC pharmacotherapies. Loss of prescription drug coverage remains a common ongoing barrier to long-term management of IBS-C and CIC with linaclotide and lubiprostone. These results provide patients and providers with additional outcome data which drive the patient-centered discussion regarding expected long-term outcomes with long-term pharmacotherapy.

Supplementary Material

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS KNOWN

Constipation-predominant IBS-C and CIC can be managed with prescription drug therapy.

To maintain long-term relief of symptoms, individuals must continue to take their medications on a regular basis.

Treatment discontinuation is clinically important outcome for these chronic, incurable conditions.

When and why patients stop medication for IBS-C or CIC is unknown.

WHAT IS NEW HERE

Individuals appear more likely to discontinue lubiprostone than linaclotide overall.

Individuals appear more likely to discontinue linaclotide compared with lubiprostone due to intolerance (mostly diarrhea).

Most discontinuations due to intolerance occur in the first 3 months.

Loss of prescription drug coverage remains a common ongoing barrier to long-term management.

Financial support:

E.D.S. received funding from the NIH T32 Training Grant in Epidemiology and Health Services (DK062708) and is funded by the AGA Research Foundation’s 2019 AGA-Shire Research Scholar Award in Functional GI and Motility Disorders.

Guarantor of the article: Eric D. Shah, MD, MBA.

Footnotes

Potential competing interests: W.D.C. is a consultant for Allergan, Biomerica, IM Health, Ironwood, Outpost, QOL Medical, Ritter, Salix, and Urovant and has research grants from Commonwealth Diagnostics, Ironwood, QOL Medical, Salix, Urovant, Vibrant, and Zespri. The other authors have no disclosures.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL accompanies this paper at https://links.lww.com/AJG/B387

REFERENCES

- 1.Spiegel B, Harris L, Lucak S, et al. Developing valid and reliable health utilities in irritable bowel syndrome: Results from the IBS PROOF cohort. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:1984–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buono JL, Carson RT, Flores NM. Health-related quality of life, work productivity, and indirect costs among patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2017;15:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lea R, Whorwell PJ. Quality of life in irritable bowel syndrome. Pharmacoeconomics 2001;19:643–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinberg DS, Smalley W, Heidelbaugh JJ, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the Pharmacological management of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2014;147:1146–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singal AG, Higgins PD, Waljee AK. A primer on effectiveness and efficacy trials. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2014;5:e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irvine EJ, Tack J, Crowell MD, et al. Design of treatment trials for functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology 2016;150: 1469–80.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cassell B, Gyawali CP, Kushnir VM, et al. Beliefs about GI medications and adherence to pharmacotherapy in functional GI disorder outpatients. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:1382–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andresen V, Camilleri M, Busciglio IA, et al. Effect of 5 days linaclotide on transit and bowel function in females with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2007;133:761–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chey WD, Saad RJ, Panas RM, et al. M1706 discontinuation of lubiprostone treatment for irritable bowel syndrome with constipation is not associated with symptom increase or recurrence: Results from a randomized withdrawal study. Gastroenterology 2008;134:A-401. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hutchins DS, Zeber JE, Roberts CS, et al. Initial medication adherence-review and recommendations for good practices in outcomes research: An ISPOR medication adherence and persistence special interest group report. Value Health 2015;18:690–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Black CJ, Burr NE, Quigley EMM, et al. Efficacy of secretagogues in patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation: Systematic review and network meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2018;155:1753–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karter AJ, Parker MM, Solomon MD, et al. Effect of out-of-pocket cost on medication initiation, adherence, and persistence among patients with type 2 diabetes: The diabetes study of northern California (DISTANCE). Health Serv Res 2018;53:1227–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hennessy D, Sanmartin C, Ronksley P, et al. Out-of-pocket spending on drugs and pharmaceutical products and cost-related prescription non-adherence among Canadians with chronic disease. Health Rep 2016;27: 3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldsmith LJ, Kolhatkar A, Popowich D, et al. Understanding the patient experience of cost-related non-adherence to prescription medications through typology development and application. Soc Sci Med 2017;194: 51–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shah E, Pimentel M. Evaluating the functional net value of pharmacologic agents in treating irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;39:973–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah E, Kim S, Chong K, et al. Evaluation of harm in the pharmacotherapy of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Med 2012;125:381–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peterson AM, Nau DP, Cramer JA, et al. A checklist for medication compliance and persistence studies using retrospective databases. Value Health 2007;10:3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanauer DA, Mei Q, Law J, et al. Supporting information retrieval from electronic health records: A report of University of Michigan’s nine-year experience in developing and using the Electronic Medical Record Search Engine (EMERSE). J Biomed Inform 2015;55:290–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goff SL, Feld A, Andrade SE, et al. Administrative data used to identify patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:617–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, et al. Medication compliance and persistence: Terminology and definitions. Value Health 2008;11:44–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah ED, Kim HM, Schoenfeld P. Efficacy and tolerability of guanylate cyclase-C agonists for irritable bowel syndrome with constipation and chronic idiopathic constipation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113:329–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shah E, Triantafyllou K, Hana AA, et al. Adverse events appear to unblind clinical trials in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2014; 26:482–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pitz M, Cheang M, Bernstein CN. Defining the predictors of the placebo response in irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;3: 237–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Owens DM, Nelson DK, Talley NJ. The irritable bowel syndrome: Long-term prognosis and the physician-patient interaction. Ann Intern Med 1995;122:107–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sommers T, Corban C, Sengupta N, et al. Emergency department burden of constipation in the United States from 2006 to 2011. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:572–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peery AF, Crockett SD, Murphy CC, et al. Burden and cost of gastrointestinal, liver, and pancreatic diseases in the United States: Update 2018. Gastroenterology 2019;156:254–72.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irvine EJ, Ferrazzi S, Pare P, et al. Health-related quality of life in functional GI disorders: Focus on constipation and resource utilization. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:1986–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bortoli Nde, Frazzoni L, Savarino EV, et al. Functional heartburn overlaps with irritable bowel syndrome more often than GERD. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:1711–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fond G, Loundou A, Hamdani N, et al. Anxiety and depression comorbidities in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2014;264:651–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Office of Communications, Division of Drug Information, Center for Drug Evaluation, Research. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Irritable Bowel Syndrome—Clinical Evaluation of Drugs for Treatment. 2012. (https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/UCM205269.pdf). Accessed July 1, 2019.

- 31.Schoenfeld PS, Chang L, Carson R, et al. Tu1069 Do baseline factors contribute to treatment satisfaction in patients with chronic constipation treated with linaclotide vs placebo? Gastroenterology 2012;142:S737–8. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Halder SLS, Locke GR, Schleck CD, et al. Natural history of functional gastrointestinal disorders: A 12-year longitudinal population-based study. Gastroenterology 2007;133:799–807.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shah ED, Almario CV, Spiegel BMR, et al. Lower and upper gastrointestinal symptoms differ between individuals with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation or chronic idiopathic constipation. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2018;24:299–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heidelbaugh JJ, Stelwagon M, Miller SA, et al. The spectrum of constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome and chronic idiopathic constipation: US survey assessing symptoms, care seeking, and disease burden. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:580–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.