Abstract

Background

The standard for clinical staging of lung cancer is the use of CT and PET scans, however, these may underestimate the burden of the disease. The use of serum tumor markers might aid in the detection of subclinical advanced disease. The aim of this study is to review the predictive value of tumor markers in patients with clinical stage I NSCLC.

Methods

A comprehensive search was performed using the Medline, EMBASE, Scopus data bases. Abstracts included based on the following inclusion criteria: 1) adult ≥18 years old, 2) clinical stage I NSCLC, 3) Tumor markers (CEA, SCC, CYFRA 21-1), 4) further imaging or procedure, 5) > 5 patients, 6) articles in English language. The primary outcome of interest was utility of tumour markers for predicting nodal involvement and oncologic outcomes in patients with clinical stage I NSCLC. Secondary outcomes included sub-type of lung cancer, procedure performed, and follow-up duration.

Results

Two hundred seventy articles were screened, 86 studies received full-text assessment for eligibility. Of those, 12 studies were included. Total of 4666 patients were involved. All studies had used CEA, while less than 50% used CYFRA 21-1 or SCC. The most common tumor sub-type was adenocarcinoma, and the most frequently performed procedure was lobectomy. Meta-analysis revealed that higher CEA level is associated with higher rates of lymph node involvement and higher mortality.

Conclusion

There is significant correlation between the CEA level and both nodal involvement and survival. Higher serum CEA is associated with advanced stage, and poor prognosis. Measuring preoperative CEA in patient with early stage NSCLC might help to identify patients with more advanced disease which is not detected by CT scans, and potentially identify candidates for invasive mediastinal lymph node staging, helping to select the most effective therapy for patients with potentially subclinical nodal disease. Further prospective studies are needed to standardize the use of CEA as an adjunct for NSCLC staging.

Keywords: Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), lymph nodes

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer related death. Optimal treatment for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is dependent on accurate clinical staging to determine the extent of disease [1–3]. Patients with lymph node involvement have worse prognosis and may be candidates for neoadjuvant treatment prior to surgical resection. The standard for clinical staging of NSCLC is the use of computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET) scans. However, these can underestimate the burden of the disease [4–7]. The median sensitivity and specificity of PET-CT for detection of mediastinal nodal disease is 80 and 88%, respectively [8]. False negatives on imaging studies result in understaging patients who might have benefited from invasive mediastinal staging or neoadjuvant therapy [7, 9, 10]. This had led researchers to investigate the use of biomarkers to increase the sensitivity of clinical staging and allow proper treatment selection. These markers include carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), squamous cell carcinoma antigen (SCC), and cytokeratin fragment antigen (CYFRA 21-1) [4, 11–13]. To our knowledge this is the first systematic review about the use of tumor markers in patients with clinical stage I NSCLC for predicting lymphatic spread.

Methods

A comprehensive search was performed for articles published on non-small cell lung cancer and tumor markers using the Medline, EMBASE, Scopus data bases. Search terms included “non-small cell lung cancer” or NSCLC or lung adenocarcinoma, AND carcinoembryonic antigen or squamous cell carcinoma antigen or cytokeratin fragment antigen, AND stage I or stage IA or early stage”. Literature was limited to human studies in the English language. Abstracts and titles were screened for inclusion by two reviewers (AN and JL). Non-relevant articles based on their abstract were not included for full-text evaluation. Abstracts were then further screened based on the following inclusion criteria: 1) adult patient ≥18 years old, 2) primary non-small cell lung cancer (stage I or stage IA or early stage), 3) Tumor markers (Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), cytokeratin fragment antigen (CYFRA 21-1) and squamous cell carcinoma antigen (SCC)), 4) any further imaging such as positron emission tomography (PET) scan or procedure such as mediastinoscopy or endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) or further treatment, 5) studies including > 5 patients, 6) articles in English language. Exclusion criteria included non-English studies, abstracts only, and duplicates.

The primary outcome of interest was utility of tumour markers for predicting pathological tumor invasiveness in patients with clinical stage I NSCLC. Secondary outcomes included subtype of lung cancer, follow-up duration, procedure performed, smoking status, and region of publication. Meta-analysis was performed to determine the following: death within 5 years, and lymph node involvement. This study was conducted and the results are presented according to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines.

In addition, two independent reviewers assessed the risk of bias using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for evaluating the quality of the included studies. We rated the quality of the studies (good, fair and poor) according to the guidelines of the NOS. A “good” quality score required 3 or 4 points in selection, 1 or 2 points in comparability, and 2 or 3 points in outcomes. A “fair” quality score required 2 points in selection, 1 or 2 points in comparability, and 2 or 3 points in outcomes. A “poor” quality score reflected 0 or 1 point in selection, or 0 points in comparability, or 0 or 1 point in outcomes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Risk of bias assessment using NOS

| No. | Name of the study | Journal | Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Identifying Patients at Risk of Early Postoperative Recurrence of Lung Cancer: A New Use of the Old CEA Test | Ann Thorac Surg | Good |

| 2 | Predictive factors for node metastasis in patients with clinical stage I non-small cell lung cancer | Annals of Thoracic Surgery | Poor |

| 3 |

Risk Factors for Predicting Occult Lymph Node Metastasis in Patients with Clinical Stage I Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Staged by Integrated Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography |

World Journal of Surgery | Good |

| 4 | Optimal Predictive Value of Preoperative Serum Carcinoembryonic Antigen for Surgical Outcomes in Stage I Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Differences According to Histology and Smoking Status | Journal of Surgical Oncology | Fair |

| 5 | Clinical significance of preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen level for clinical stage I non-small cell lung cancer: can preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen level predict pathological stage? | Interactive CardioVascular and Thoracic Surgery | Good |

| 6 |

Predictive Risk Factors for Mediastinal Lymph Node Metastasis in Clinical Stage IA Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer Patients |

Journal of Thoracic Oncology: Official Publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer | Fair |

| 7 |

Sialyl Lewis X as a predictor of skip N2 metastasis in clinical stage IA non-small cell lung cancer |

World Journal of Surgical Oncology | Good |

| 8 | Clinical significance of preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen level in patients with clinical stage IA non-small cell lung cancer | J Thorac Dis | Good |

| 9 | Prognostic impact of Cyfra21–1 and other serum markers in completely resected non-small cell lung cancer | Lung Cancer | Good |

| 10 | Significant correlation between urinary N1, N12-diacetylspermine and tumor invasiveness in patients with clinical stage IA non-small cell lung cancer | BMC Cancer | Poor |

| 11 |

Prediction of lymph node status in clinical stage IA squamous cell carcinoma of the lung |

European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery | Good |

| 12 |

Predictive Factors for Lymph Node Metastasis in Clinical Stage IA Lung Adenocarcinoma |

Annals of Thoracic Surgery | Poor |

Results

Study selection

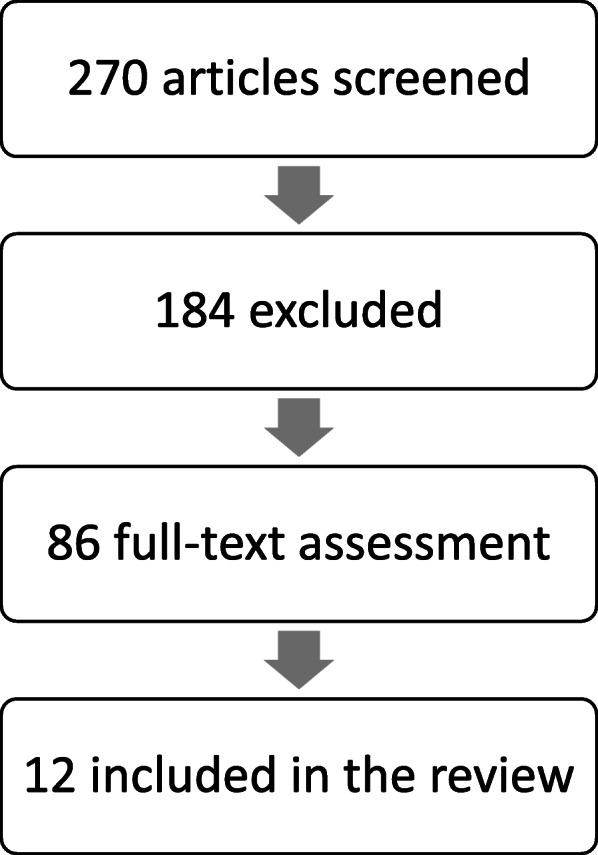

Preliminary literature search yielded 270 articles after duplicates were removed. All these 270 studies were screened. Eighty-six studies received full-text assessment for eligibility. Of those, 12 studies were included in the final systematic review (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram with search results for systematic review

Basic demographics

Twelve studies with 4666 patients were included for systematic review. The majority of these studies were retrospective (10/12) and most were conducted in Japan (8/12). The mean age of the subjects was 65.3 ± 3.2 years, 2602 were males, and 2064 were females (Table 2). The mean follow-up period was 48.86 months. Nine studies, involving 3842 patients reported smoking status, in which 2003 were smokers (52.1%).

Table 2.

Patients demographics

| Number of patients | 4666 |

|---|---|

| Male | 2602 |

| Female | 2064 |

| Age (mean) | 65.3 ± 3.2 years |

| Smoking status | |

| Smoker | 2003 |

| Non-smoker | 1839 |

| Not specified | 824 |

| Histological types | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 3622 |

| Squamous cell cancer | 697 |

| Large cell cancer | 54 |

| Adenosquamous carcinoma | 17 |

| Carcinoid tumor | 12 |

| Others | 264 |

| Follow up (mean) | 48.86 months |

| Country | |

| Japan | 8 |

| China | 1 |

| Korea | 1 |

| Germany | 1 |

| Italy | 1 |

Reporting of tumor markers and tumor characteristics

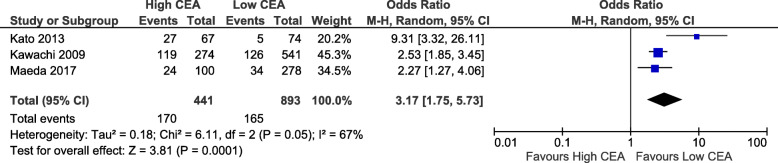

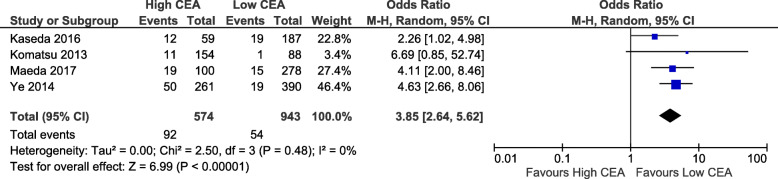

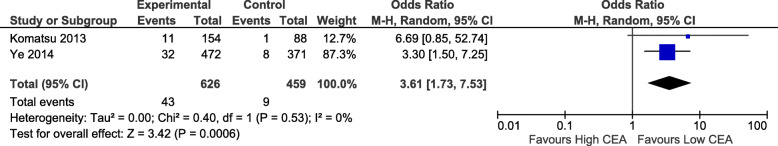

All the studies included investigated CEA, while 4 studies also used CYFRA 21-1, and 2 studies used SCC. Given there was a low number of studies looking at tumour markers other than CEA, we excluded the analysis of these markers from our review. The cut-off value for abnormal CEA differed among the studies, ranging from 2.5 to 10 ng/mL (Table 3). Seven out of the twelve articles included in this review had used 5 ng/mL as cut-off value. The majority of the studies involved the use of PET scan (10 studies) for clinical staging, while fewer studies used EBUS (2 studies), mediastinoscopy (1 study), or image guided biopsy (1 study). The most frequently performed procedure was lobectomy (2715, 67.7%), followed by segmentectomy (374, 11.8%), wedge resection (47, 1.5%), pneumonectomy (45, 1.4%),bilobecomy (24, 7.6%). However, 4 studies did not specify the operative procedure. The tumor sub-types were: adenocarcinoma (3622, 77.6%), squamous cell cancer (697, 14.9%), large cell cancer (54, 1.2%), adenosquamous (17, 0.4%), carcinoid (12, 0.3%), other (264, 5.7%) (Table 3). Postoperative staging were specified in 7 studies as the following: stage I (1,228, 79.2%), stage II (121, 7.8%), stage III (198, 12.8%), stage IV (3, 0.2%). Pathologic lymph node status were: NO (2315, 86.3%), N1 (192, 6.7%), N2 (158), N 1–3 (197, 5.5%), while three studies did not report lymph nodes details. Meta-analysis was performed to determine the association of high CEA with death within 5 years and lymph node involvement. High CEA had an odds of death within 5 years that is 3.17 times that of low CEA (95% CI 1.75 to 5.73, p = 0.0001). This result had high heterogeneity (chi2 = 67%, p = 0.05). This analysis included 3 studies and 1334 patients (Fig. 2). For nodal status, high CEA had a higher odds of there being any positive nodal metastases (OR 3.85, 95% CI 2.64 to 5.62, p < 0.00001) compared to low CEA. This result had low heterogeneity (chi2 = 0%, p = 0.48). This analysis included 4 studies and 1517 patients (Fig. 3). Further subanalysis revealed that high CEA had higher odds of positive N2 that is 3.61 times that of low CEA (95% CI 1.73 to 7.53, p = 0.0006). This analysis included 2 studies and 1085 patients (Fig. 4). Heterogeneity was low (chi2 = 0%, p = 0.53).

Table 3.

Studies included in the review

| Low CEA | High CEA | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO | Author | Year of publication | No. of patients | CEA cut-off | No. of LN | 5 year survival | Recurrence | No. of LN | 5 year survival | Recurrence |

| 1 | Ryo Maeda [29] | 2017 | 378 | 5 ng/mL | 263 N0, 15 N1–3 | 87.70% | 81 N0, 19 N1–3 | 75.50% | ||

| 2 | Yusuke Takahashi [30] | 2015 | 171 | 5 ng/mL | ||||||

| 3 | Gianfranco Buccheri [18] | 2003 | 118 | 10 ng/mL | 16% | 70% | ||||

| 4 | Riken Kawachi [31] | 2009 | 815 | 5 ng/mL | 76.70% | 56.60% | ||||

| 5 | Niels Reinmuth [19] | 2002 | 67 | 5 ng/mL | ||||||

| 6 | Sukki Cho [32] | 2013 | 770 | 3.5 ng/mL (mean) | ||||||

| 7 | Kaoru Kaseda [33] | 2016 | 246 | 5 ng/mL | 168 N0, 19 N1-N2 | 47 N0, 12 N1-N2 | ||||

| 8 | Tatsuya Kato [34] | 2013 | 177 | 3 ng/mL | 93.2% (ADC), 81% (SCC) | 6.80% | 59.4% (ADC), 51.9% (SCC) | 38.80% | ||

| 9 | Terumoto Koike [35] | 2012 | 894 | 5 ng/mL | ||||||

| 10 | Hiroaki Komatsu [36] | 2013 | 279 | 2.8 ng/mL | 87 N0, 1 skip N2 | 143 N0, 11 skip N2 | ||||

| 11 | Yasuhiro Tsutani [37] | 2014 | 100 | 2.5 ng/mL | ||||||

| 12 | Bo Ye [38] | 2014 | 651 | 5 ng/mL | 371 N0, 11 N1, 8 N2 | 211 N0, 32 N1,18 N2 | ||||

Fig. 2.

Correlation between CEA level and 5-year mortality

Fig. 3.

Correlation between CEA level and lymph nodes involvement

Fig. 4.

Correlation between CEA level and N2 lymph nodes involvement

Risk of bias assessment

Most of the studies included had good or fair quality score, only 3 studies their quality score was poor. Those whose scored poor on their quality lost some point on follow up.

Discussion

Accurate preoperative staging of NSCLC is integral for appropriate treatment plan. The main treatment for patients with stage I NSCLC is surgery. Unfortunately, due to limited sensitivity of preoperative imaging, up to 30% of patients with stage I NSCLC may have positive N2-N3 lymph nodes at the time of resection [8, 14, 15]. A meta-analysis of 20 studies showed that mediastinal lymph node staging using CT scan had 57% sensitivity and 82% specificity [16]. Similarly, Cerfolio et al. showed that 7 of 17 patients with cN1 (41%) were found to have positive N2 after lymph node sampling by mediastinoscopy or endoscopic ultrasound with fine needle aspiration (EUS FNA), although N2 involvement was excluded initially by PET/CT scan [17]. The ability to detect subclinical nodal involvement prior to surgery could allow identification of cN0 patients who might benefit from invasive staging, while patients with low CEA levels could conceivably be spared invasive staging if they would otherwise qualify for reasons such as large tumour size or central tumour. Better preoperative staging should result in improved treatment selection, as patients may benefit from neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy rather than upfront surgery. In patients with early stage I NSCLC, in whom lymph sampling versus lymph dissection is controversial, the use of CEA could also identify patients in need of more aggressive lymphadenectomy [18–20]. Whether the increased risk of mortality found in this meta-analysis is completely attributable to the increased rate of nodal involvement can not be determined from the available studies’ data, but identification of patients with poor prognosis related to high CEA may also allow for a more tailored approach to post-resection surveillance and patient counselling.

Due to the limited ability of preoperative imaging CT or PET-CT to detect mediastinal lymph nodes disease, interest in serum biomarkers in lung cancer is growing. The most frequently studied tumor marker is carcinoembryonic antigen. All histological types of lung cancer can produce CEA and a role for its use in lung cancer screening and staging was first proposed in the 1970s [21–25]. Recently, studies have demonstrated the usefulness of CEA in patients with NSCLC for postoperative follow up, response to chemotherapy, recurrence, and prognosis. High CEA level has been correlated with advanced disease and poor prognosis. Serum CEA measurement is a simple, non-invasive, inexpensive test. In such case, patients with high CEA level might benefit from lymph node sampling by mediastinoscopy or endoscopic ultrasound with fine needle aspiration (EUS FNA) [18, 25–27]. As shown in our meta-analysis CEA level is correlated with lymph node involvement, and further sub-analysis did reveal that higher CEA associated with positive N2.

There is a discrepancy in the cut-off value of CEA ranges from 2.5 to 10 ng/mL and is attributable to the different techniques used for measurement such as radioimmunoassay (RIA) and enzyme immunoassay [21, 28]. Further studies are needed to standardize the cut-off value. Our meta-analysis about lymph nodes involvement and death within 5 years was limited to few studies because most did not mention the specific details needed to conduct the analysis. Other limitations in our study include the following: the majority of included studies were retrospective, done in a single country (Japan) and many lacked specific lymph nodes details (N0, N1, N2, N3). In addition, we excluded non-English articles. As such we recommend a prospective study using CEA preoperatively to accurately correlate the level of CEA with risk of lymph nodes metastasis, and to determine the cut-off value of CEA.

Conclusion

There is significant correlation between the CEA level and both nodal involvement and survival. Higher level of CEA is associated with advanced stage, and poor prognosis. Performing preoperative CEA in patient with early stage NSCLC might help to identify patients with more advanced disease which is not detected by imaging, and potentially identify patients for invasive mediastinal lymph node staging, helping to select the most effective therapy for patients with potentially subclinical nodal disease. Further prospective studies are needed to standardize the use of CEA as an adjunct for NSCLC staging.

Acknowledgements

University of Alberta librarian who provided teaching how to conduct a comprehensive search.

Abbreviations

- EBUS

Endobronchial ultrasound

- CT

Computed tomography

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- LN or N

Lymph node

- cN

clinical stage lymph node

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer

- CEA

Carcinoembryonic antigen

- SCC

Squamous cell carcinoma antigen

- CYFRA 21-1

Cytokeratin fragment antigen

- EUS FNA

Endoscopic ultrasound with fine needle aspiration

- RIA

Radioimmunoassay

- NOS

Newcastle–Ottawa Scale

Authors’ contributions

Awrad Nasralla: comprehensive search, data screening, data collection, data analysis, and writing the paper. Jeremy Lee: data screening, collection and analysis. Jerry Dang: meta-analysis. Simon Turner: supervision, data analysis, and writing the paper. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

Possible upon request, we can share our Excel sheet of data.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Informed consent does not apply for this type of study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

None.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Barta JA, Powell CA, Wisnivesky JP, Glob A, Author H. Global Epidemiology of Lung Cancer HHS Public Access Author manuscript. Ann Glob Heal. 2019;85(1) [cited 2020 Feb 25]. Available from: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Zhang C, Leighl NB, Wu Y-L, Zhong W-Z. Emerging therapies for non-small cell lung cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0731-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson S, Ilonen I, Järvinen T, Rauma V, Räsänen J, Salo J. Surgically Treated Unsuspected N2-Positive NSCLC: Role of Extent and Location of Lymph Node Metastasis. Clin Lung Cancer. 2018;19(5):418–425. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2018.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen F, Wang X-Y, Han X-H, Wang H, Qi J. Diagnostic value of Cyfra21-1, SCC and CEA for differentiation of early-stage NSCLC from benign lung disease. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(7):11295–11300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDonald F, De Waele M, Hendriks LEL, Faivre-Finn C, Dingemans A-MC, Van Schil PE. Management of stage I and II nonsmall cell lung cancer. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(1) [cited 2020 Feb 25]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28049169. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Aktas GE, Karamustafaoğlu YA, Balta C, Süt N, Sarikaya İ, Sarikaya A. Prognostic significance of fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography-derived metabolic parameters in surgically resected clinical-N0 nonsmall cell lung cancer. Nucl Med Commun. 2018;39(11):995–1004. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0000000000000903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gómez-Caro A, Garcia S, Reguart N, Arguis P, Sanchez M, Gimferrer JM, et al. Incidence of occult mediastinal node involvement in cN0 non-small-cell lung cancer patients after negative uptake of positron emission tomography/computer tomography scan. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;37(5):1168–1174 [cited 2020 May 30]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20116273. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.D'Andrilli A, Maurizi G, Venuta F, Rendina EA. Mediastinal staging: when and how? Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2020;68(7):725–732. doi: 10.1007/s11748-019-01263-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turner SR, Seyednejad N, Nasir BS. Patterns of Practice in Mediastinal Lymph Node Staging for Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer in Canada. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;106(2):428–434. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho HJ, Kim SR, Kim HR, Han J-O, Kim Y-H, Kim DK, et al. Modern outcome and risk analysis of surgically resected occult N2 non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97(6):1920–1925. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang-Chun F, Min F, Di Z, Yan-Chun H. Retrospective Study to Determine Diagnostic Utility of 6 Commonly Used Lung Cancer Biomarkers Among Han and Uygur Population in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region of People’s Republic of China. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95(18):e3568. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000003568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu H, Huang X, Zhu Z, Hu Y, Ou W, Zhang L, et al. Significance of combined detection of LunX mRNA and tumor markers in diagnosis of lung carcinoma. Chin J Cancer Res [Internet]. 2014;26(1):89–94 [cited 2020 may 30]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24653630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Molina R, Marrades RM, Augé JM, Escudero JM, Viñolas N, Reguart N, Ramirez J, Filella X, Molins L, Agustí A. Assessment of a combined panel of six Serum tumor markers for Lung Cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(4):427–437. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201404-0603OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Decaluwé H, Dooms C, D’Journo XB, Call S, Sanchez D, Haager B, et al. Mediastinal staging by videomediastinoscopy in clinical N1 non-small cell lung cancer: a prospective multicentre study. Eur Respir J. 2017;50(6) [cited 2020 may 30]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29269579. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Hishida T, Yoshida J, Nishimura M, Nishiwaki Y, Nagai K. Problems in the current diagnostic standards of clinical N1 non-small cell lung cancer. Thorax. 2008;63(6):526–531. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.062760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toloza EM, Harpole L, DC MC. Noninvasive staging of non-small cell lung cancer: a review of the current evidence. Chest. 2003;123(1 Suppl):137S–146S. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.1_suppl.137S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cerfolio RJ, Bryant AS, Eloubeidi MA. Routine mediastinoscopy and esophageal ultrasound fine-needle aspiration in patients with non-small cell lung cancer who are clinically N2 negative: a prospective study. Chest. 2006;130(6):1791–1795. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.6.1791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buccheri G, Ferrigno D. Identifying patients at risk of early postoperative recurrence of lung cancer: a new use of the old CEA test. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75(3):973–980. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(02)04638-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reinmuth N, Brandt B, Semik M, Kunze W-P, Achatzy R, Scheld HH, et al. Prognostic impact of Cyfra21-1 and other serum markers in completely resected non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2002;36(3):265–270. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5002(02)00009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki K, Nagai K, Yoshida J, Moriyama E, Nishimura M, Takahashi K, et al. Prognostic factors in clinical stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg [Internet]. 1999;67(4):927–932 [cited 2020 Feb 28]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10320230. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Hanagiri T, Sugaya M, Takenaka M, Oka S, Baba T, Shigematsu Y, et al. Preoperative CYFRA 21-1 and CEA as prognostic factors in patients with stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2011;74(1):112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsu W-H, Huang C-S, Hsu H-S, Huang W-J, Lee H-C, Huang B-S, et al. Preoperative serum carcinoembryonic antigen level is a prognostic factor in women with early non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83(2):419–424. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.07.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Concannon JP, Dalbow MH, Hodgson SE, Headings JJ, Markopoulos E, Mitchell J, et al. Prognostic value of preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) plasma levels in patients with bronchogenic carcinoma. Cancer. 1978;42(S3):1477–1483. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197809)42:3+<1477::AID-CNCR2820420818>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt-Hansen M, Baldwin DR, Hasler E, Zamora J, Abraira V, Roqué I, Figuls M. PET-CT for assessing mediastinal lymph node involvement in patients with suspected resectable non-small cell lung cancer. Cochrane Datab Syst Rev. 2014;2014(11):CD009519. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009519.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuo Y-S, Zheng M-Y, Huang M-F, Miao C-C, Yang L-H, Huang T-W, et al. Association of Divergent Carcinoembryonic Antigen Patterns and Lung Cancer Progression. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2020;10(1):2066 [cited 2020 May 30]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32034239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Sawabata N, Ohta M, Takeda S, Hirano H, Okumura Y, Asada H, et al. Serum carcinoembryonic antigen level in surgically resected clinical stage I patients with non- small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74(1):174–179. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(02)03662-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang J, Ma Y, Zhu Z-H, Situ D-R, Hu Y, Rong T-H. Expression and prognostic relevance of tumor carcinoembryonic antigen in stage IB non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2012;4(5):490–496. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2012.09.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nisselbaum JS, Smith CA, Schwartz D, Schwartz MK. Comparison of Roche RIA, Roche EIA, Hybritech EIA, and Abbott EIA methods for measuring carcinoembryonic antigen. ClinChem. 1988;34(4):761–764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maeda R, Suda T, Hachimaru A, Tochii D, Tochii S, Takagi Y. Clinical significance of preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen level in patients with clinical stage IA non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9(1):176–186. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.01.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takahashi Y, Horio H, Sakaguchi K, Hiramatsu K, Kawakita M. Significant correlation between urinary N1, N12-diacetylspermine and tumor invasiveness in patients with clinical stage IA non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2015;15(1):65. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1068-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawachi R, Nakazato Y, Takei H, Koshi-ishi Y, Goya T. Clinical significance of preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen level for clinical stage I non-small cell lung cancer: can preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen level predict pathological stage? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2009;9(2):199–202. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2009.206698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cho S, Song IH, Yang HC, Kim K, Jheon S. Predictive Factors for Node Metastasis in Patients With Clinical Stage I Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(1):239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaseda K, Asakura K, Kazama A, Ozawa Y. Risk Factors for Predicting Occult Lymph Node Metastasis in Patients with Clinical Stage I Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Staged by Integrated Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography. World J Surg. 2016;40(12):2976–2983. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3652-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kato T, Ishikawa K, Aragaki M, Sato M, Okamoto K, Ishibashi T, et al. Optimal predictive value of preoperative serum carcinoembryonic antigen for surgical outcomes in stage I non-small cell lung cancer: Differences according to histology and smoking status. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107(6):619–624. doi: 10.1002/jso.23293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koike T, Koike T, Yamato Y, Yoshiya K, Toyabe S-I. Predictive risk factors for mediastinal lymph node metastasis in clinical stage IA non-small-cell lung cancer patients. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7(8):1246–1251. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31825871de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Komatsu H, Mizuguchi S, Izumi N, Chung K, Hanada S, Inoue H, et al. Sialyl Lewis X as a predictor of skip N2 metastasis in clinical stage IA non-small cell lung cancer. World J SurgOncol. 2013;11:309. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-11-309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsutani Y, Murakami S, Miyata Y, Nakayama H, Yoshimura M, Okada M. Prediction of lymph node status in clinical stage IA squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. Eur J Cardio-Thoracic Surg. 2015;47(6):1022–1026. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezu363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ye B, Cheng M, Li W, Ge X-X, Geng J-F, Feng J, et al. Predictive factors for lymph node metastasis in clinical stage IA lung adenocarcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98(1):217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Possible upon request, we can share our Excel sheet of data.