Abstract

Background

Drought stress is an environmental factor that limits plant growth and reproduction. Little research has been conducted to investigate the MLP gene in tobacco. Here, NtMLP423 was isolated and identified, and its role in drought stress was studied.

Results

Overexpression of NtMLP423 improved tolerance to drought stress in tobacco, as determined by physiological analyses of water loss efficiency, reactive oxygen species levels, malondialdehyde content, and levels of osmotic regulatory substances. Overexpression of NtMLP423 in transgenic plants led to greater sensitivity to abscisic acid (ABA)-mediated seed germination and ABA-induced stomatal closure. NtMLP423 also regulated drought tolerance by increasing the levels of ABA under conditions of drought stress. Our study showed that the transcription level of ABA synthetic genes also increased. Overexpression of NtMLP423 reduced membrane damage and ROS accumulation and increased the expression of stress-related genes under drought stress. We also found that NtWRKY71 regulated the transcription of NtMLP423 to improve drought tolerance.

Conclusions

Our results indicated that NtMLP423-overexpressing increased drought tolerance in tobacco via the ABA pathway.

Keywords: NtMLP423, Drought stress, ABA, Nicotiana tabacum

Background

Drought stress is not conducive to plant growth and development, as it can cause changes in plant morphology and damage to cells [1, 2]. Plants have evolved many complex physiological and biochemical mechanisms to adapt to drought. The plant hormone, abscisic acid, regulates the physiological processes of plants under biotic and abiotic stresses [3].

Abscisic acid is a key sesquiterpene which is participated in many important processes of plant growth and development, and controls many genes related to stress adaptation responses and osmotic adjustment [4–6]. The increase in ABA synthesis under drought stress can promote stomatal closure and reduce transpiration loss [7]. Due to the role of ABA in response to drought stress, genes involved in the biosynthesis of ABA have been identified, such as 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase (NCED), xanthoxin dehydrogenase/reductase (ABA2), and ABA-aldehyde oxidase 3 (AAO3) [8, 9]. In Arabidopsis, NCED3 contributes to ABA accumulation in response to drought stress [10], while the aba2 and aao3 mutants decreased ABA levels under drought stress [11, 12].

The major latex protein (MLP) gene was first identified in latex of the opium poppy [13, 14]. Orthologs of MLP, called MLP-like proteins, were found in other plants [15, 16]. Each plant species can contain multiple members of the MLP family. For example, there are 26, 14, and 27 MLPs in Arabidopsis, Vitis vinifera, and Solanum lycopersicum, respectively [17, 18]. The MLP family is characterized by low sequence similarities, whereas the three-dimensional structures are similar. It was found that two MLPs in Arabidopsis could delay flowering by inducing cis-cinnamic acid [19] and that MLP is closely related to ripening in fruits such as peach and kiwifruit [20]. Overexpression of GhMLP increases the flavonoid content of Arabidopsis and increases tolerance to salt stress [21], while the MLP expression level in wild strawberry and cucumber is increased by mechanical damage [22]. The expression of MLP gene family differs significantly in different tissues; however, there is little research on MLP genes, and the molecular mechanism of MLPs in response to abiotic stress remains elusive in tobacco. Here, we cloned the NtMLP423 gene from tobacco and tested the stress response of NtMLP423-overexpressing transgenic plants.

Results

Subcellular localization of NtMLP423

We constructed the Pro35S::MLP423-GFP vector and injected it into the leaves of Nicotiana benthamiana by agroinfiltration. Confocal microscopy results indicated that NtMLP423 protein was localized in cytoplasm and nucleus (Fig. S1).

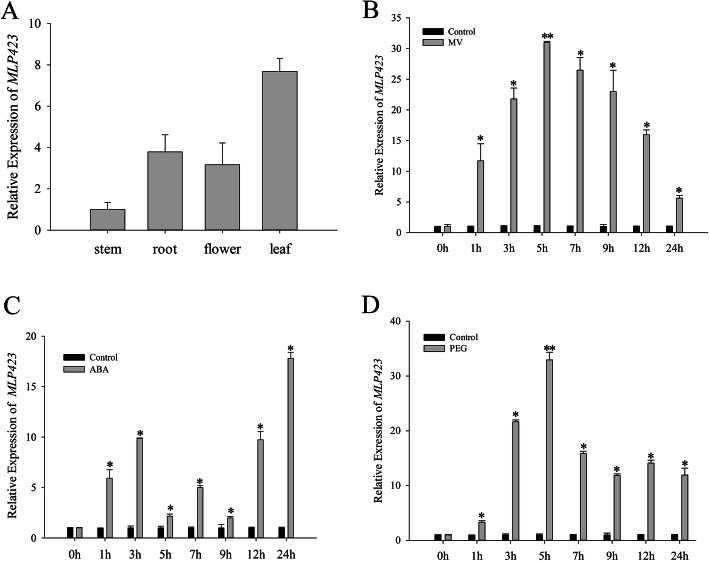

Expression analysis of NtMLP423 in tobacco

The tissue expression analysis of NtMLP423 by qRT-PCR showed the highest expression of NtMLP423 in the leaves, followed by the roots, with the lowest expression in the stems (Fig. 1a). Expression of NtMLP423 under methyl viologen (MV), ABA and polyethyleneglycol (PEG) treatments were detected by qPCR. Results indicated differential upregulation under the three treatments (Fig. 1b-d). The induction of ABI5 (abscisic acid insensitive 5; ABA-responsive gene) [23], P5CS (pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthase; proline biosynthesis key gene), and DEFL (defensin-like; H2O2 and MV-responsive gene) [24, 25] ensured that the treatments were effective (Fig. S2). The induction rate in the PEG treatment was more than 30 times higher than that in control group over 5 h, while that in the ABA treatment for 24 h was the most significant. These results suggested that NtMLP423 was regulated by drought stress and drought-related signaling molecules.

Fig. 1.

Expression analysis of NtMLP423. Expression of NtMLP423 gene in different tissues (a), under 10 μM MV treatments in tobacco leaves (b), under 100 μM ABA treatments in tobacco leaves (c), and under 20% PEG treatments in tobacco leaves (d). Data represent means ± SE (n = 3). * indicate significant difference relative to controls (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01)

Overexpression of NtMLP423 confers drought tolerance in Arabidopsis

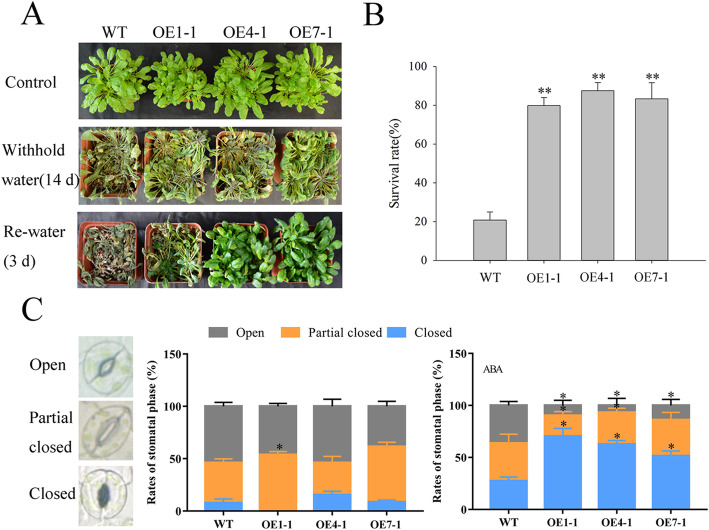

To investigate whether NtMLP423 is participated in drought stress, we obtained transgenic Arabidopsis expressing the NtMLP423 gene. NtMLP423 was expressed in all transgenic Arabidopsis (Fig. S3), and three T3-generation homozygous lines (OE1–1, OE4–1 and OE7–1) were selected for subsequent experiments. Transgenic and wild type (WT) seeds were sown in murashige and skoog (MS) medium and in a mannitol medium. The results suggested that there was no difference in germination rate in MS medium; however, germination rate of overexpressing NtMLP423 Arabidopsis were higher than that of WT seeds in different concentrations of the mannitol medium (Fig. S4A, B). The average root length of overexpressing NtMLP423 plants was significantly longer than that of WT plants (Fig. S4C, D). We examined the effects of NtMLP423 overexpression under drought stress by discontinuing irrigation to the plants for 2 weeks, followed by a watering period of 3 d to observe the recovery process. The results showed that only 20.8% of WT plants survived after watering resumed, whereas transgenic survival rate was more than 80% (Fig. 2a-b). We further examined the effects of NtMLP423 overexpression under drought stress by treating plants with 20% PEG. We found that WT plants had more severe wilting than the transgenic plants (Fig. S5A). Relative water content of transgenic plants were found to be much higher than that of WT following drought stress (Fig. S5B). Osmotic potential of leaves of overexpressing NtMLP423 were also significantly lower than that of WT under drought stress (Fig. S5C). The results suggested that overexpression of NtMLP423 increased the resistance to drought stress in Arabidopsis.

Fig. 2.

The NtMLP423 gene is involved in drought stress responses in Arabidopsis. a Irrigation was discontinued for 14 days, followed by 3 days of watering and observation of phenotypes after re-watering. b Survival rate of plants treated with drought stress. c Stomatal aperture after ABA treatment. The proportions of different stomata phases were calculated with or without ABA treatment. Data are means ± SE (n = 3). * indicate significant difference (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01)

Overexpression of NtMLP423 increases ABA sensitivity and accumulation in Arabidopsis

The ABA hormone plays a key role in regulating growth and responses to various stress conditions in plants, including stomatal closure [26]. We detected ABA-induced stomatal closure (pore phase was defined as closed, partially open, or open, based on the ratio of width to length of the pore diameter). There were no significant differences in ratios between all lines without ABA treatment. However, after ABA treatment for 30 min, the percentage of stomatal closure in overexpressing NtMLP423 was much higher than in WT (Fig. 2c). The percentage of stomatal closure of WT, OE1–1, OE4–1 and OE7–1 transgenic plants increased by 2.56 times, 22.67 times, 3.52 times, and 6.22 times, respectively, after ABA treatment. The results suggested that the improvement of drought tolerance is associated with ABA-induced stomatal closure.

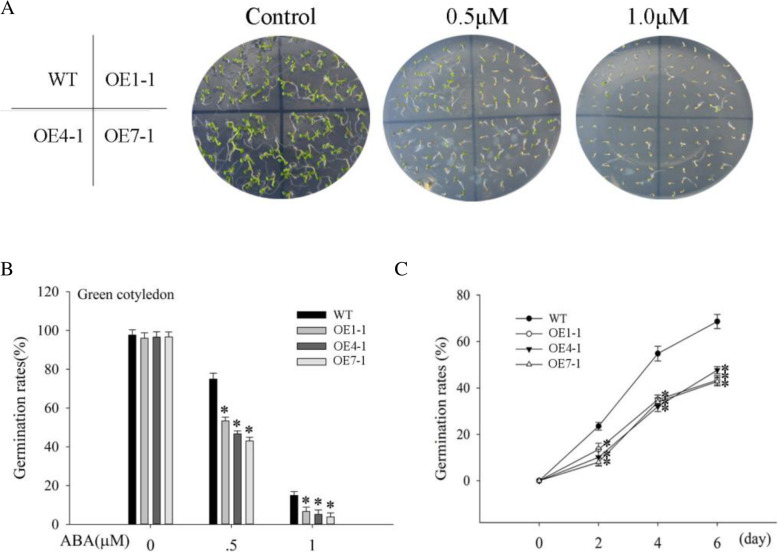

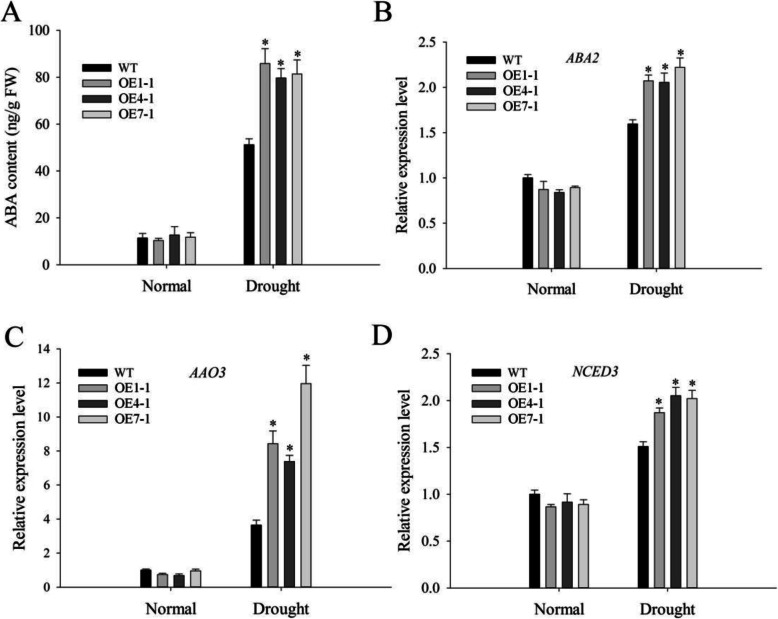

To evaluate the role of ABA as a signal molecule during plant stress response [3], we conducted ABA treatments. In the medium without ABA, there were no differences in germination rates among all plants. At different ABA concentrations (0.5 and 1.0 μM), plants in which NtMLP423 was overexpressed indicated significantly decreased germination rates compared to WT plants (Fig. 3), indicating that overexpression of NtMLP423 improves ABA sensitivity. Under normal conditions, ABA content in all plants was similar, while it was significantly higher in overexpressing NtMLP423 than in WT plants under drought stress, which increased by approximately 2.0 times (Fig. 4a). We further measured the expression levels of ABA-related genes and found that expression levels of ABA-synthesizing genes (ABA2, AAO3, and NCED3) in overexpressing NtMLP423 were significantly higher than those in WT under drought conditions (Fig. 4b-d). Here, we also tested the genes involved in ABA catabolism pathway (Fig. S6). The results indicated that expression of the BG1 (β-glucosidase 1) gene in overexpressing NtMLP423 plants were significantly higher than that of WT under drought stress, but the expression level of CYP707A1 (cytochrome P450 monooxygenase 707A1) gene was lower than that of WT under drought stress (Fig. S6A, S6C). BG2 (β-glucosidase 2) and UGT71C5 (UDP-glucosyltransferase 71C5) gene expressions were not significantly different in all lines that were subjected to drought stress (Fig. S6B, S6D).

Fig. 3.

NtMLP423 gene involvement in ABA responses in the seed germination assay. a Seeds growing on MS medium added with ABA. b Germination rates under ABA treatment. c Germination rate changes with time under 0.5 μM ABA. Data represent means ± SE (n = 3). * indicate significant difference relative to WT (*P < 0.05)

Fig. 4.

ABA content in Arabidopsis leaves and gene expression related to ABA biosynthesis under drought stress. a ABA content under normal (untreated) conditions and after 20% PEG treatment. b-d Expression levels of ABA2, AAO3, and NCED3 under drought stress. Data represent means ± SE (n = 3). * indicate significant difference relative to WT (*P < 0.05)

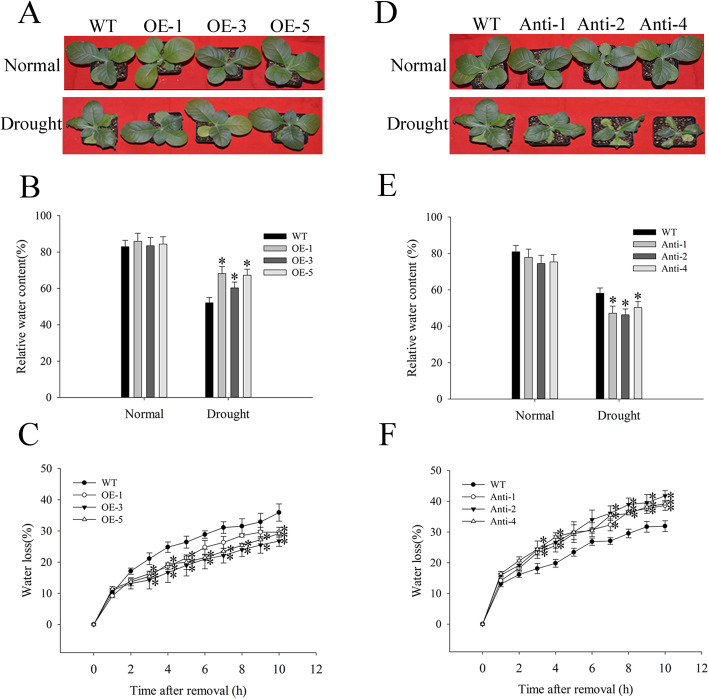

Overexpression of NtMLP423 confers drought tolerance in tobacco

To examine drought tolerance in tobacco, we detected the expression level of NtMLP423 in transgenic lines and selected three lines of the T2-generation overexpressing NtMLP423 (OE-1, OE-3, and OE-5), and three antisense transgenic lines (Anti-1, Anti-2, and Anti-4) for subsequent analysis (Fig. S7). We examined the effects of NtMLP423 overexpression in tobacco under drought stress using 20% PEG treatments. We found more severe wilting in WT than in overexpressing NtMLP423 plants (Fig. 5a). RWC of overexpressed plants was much higher than that of WT after drought stress and RWC of OE-1, OE-3, and OE-5 increased by 1.17, 1.11, and 1.14 times, respectively, compared to WT. The water loss rate of overexpressing NtMLP423 leaves in vitro was lower than that of WT leaves (Fig. 5b-c). However, antisense transgenic tobacco showed the opposite result, which reduces the resistance to drought stress, as shown in Fig. 5d-f. Antisense plants had more severe wilting than the WT, and RWC was lower than that of the WT; however, the rate of water loss from antisense plants was higher than that of WT (Fig. 5d-f). In addition, the osmotic potential of tobacco leaves were measured and found that osmotic potential of overexpressing NtMLP423 was lower than that of WT, while antisense plants had the highest osmotic potential (Fig. S8). The results indicated that NtMLP423 overexpression increased resistance to drought stress in tobacco.

Fig. 5.

Overexpression of NtMLP423 enhances drought tolerance in tobacco. a Phenotypic observation of overexpressing NtMLP423 plants treated with 20% PEG for 7 days. b RWC of overexpressing NtMLP423 plants. c Water loss rates of overexpressing NtMLP423 detached leaves. Tobacco plants carrying antisense NtMLP423 gene showed increased sensitivity to drought stress. d Phenotypic observation of antisense transgenic plants treated with 20% PEG for 7 days. e RWC of antisense transgenic plants. f Water loss rates of antisense transgenic detached leaves. Data represent means ± SE (n = 3). * indicate significant difference relative to WT (*P < 0.05)

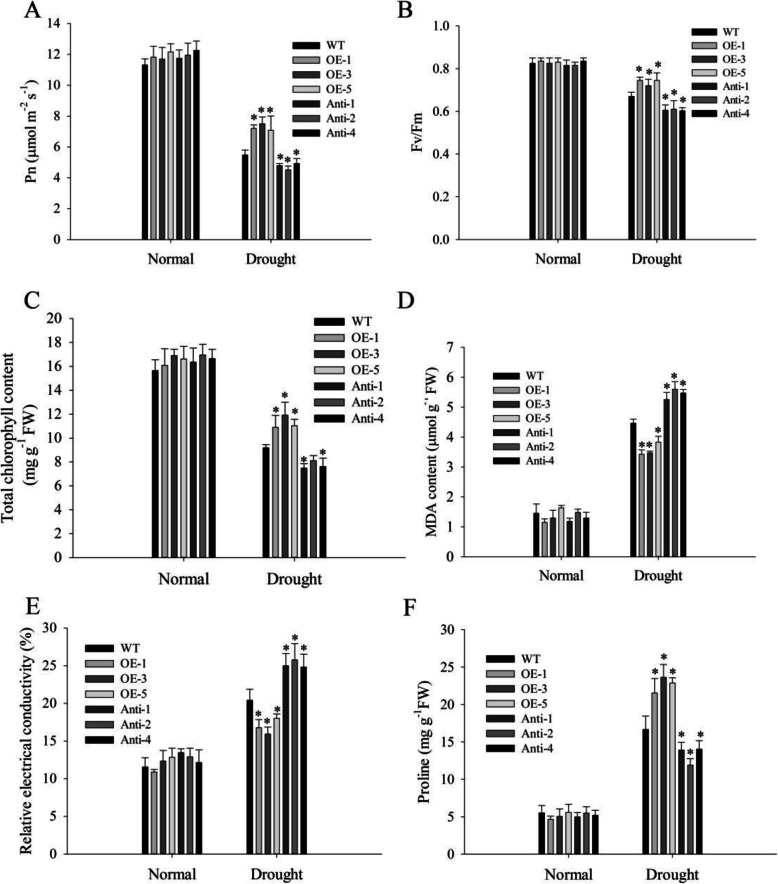

Overexpression of NtMLP423 enhances photosynthesis under drought stress in tobacco

Net photosynthetic rates (Pn) of all plants decreased markedly after drought stress, with the greatest decrease in the antisense line and the lowest decrease in the overexpressed line. The Pn of WT, OE-1, OE-3, OE-5, Anti-1, Anti-2, and Anti-4 decreased by 47.3, 33.8, 32.5, 41.2, 62.7, 63.1, and 63.3%, respectively, after drought stress treatment (Fig. 6a). The variable fluorescence/maximum fluorescence (Fv/Fm) ratio of all plants decreased after drought stress. However, the decrease in Fv/Fm of antisense was larger than that of other lines, while the decrease in Fv/Fm of overexpressed plants was smaller (Fig. 6b). Chlorophyll content of all lines decreased markedly, by 41.1, 37.5, 29.5, 33.7, 54.2, 52.3, and 54.3%, in WT, OE-1, OE-3, OE-5, Anti-1, Anti-2, and Anti-4, respectively (Fig. 6c).

Fig. 6.

Physiological determination of tobacco under drought stress. a Pn of tobacco leaves. b Fv/Fm ratio of tobacco. c Chlorophyll content determination. d MDA content of plants. e Relative electrical conductivity in plants. f Proline content under drought stress. Data represent means ± SE (n = 3). * indicate significant difference relative to WT (*P < 0.05)

Overexpression of NtMLP423 alleviates membrane damage and reduces ROS levels under drought stress in tobacco

The cell membrane of plants is subject to damage under adverse conditions, the extent of which can be reflected by levels of malondialdehyde (MDA). MDA content increased in all groups under drought stress; however, MDA content in overexpressed was lower than that in WT plants, and antisense plants showed the highest content (Fig. 6d). In addition, the relative electrical conductivity of overexpressing NtMLP423 was the lowest, while that of antisense plants was the highest after drought stress (Fig. 6e). These results showed that membrane damage in overexpressed plants was the lowest under drought stress. Because proline is a key intracellular osmotic regulator and plays an important role in osmotic stress resistance [27], proline content in the different plant lines were measured. Drought stress improved proline content in all lines, with the highest content in overexpressed plants and the lowest in antisense plants (Fig. 6f). The results indicated that overexpressing plants could reduce osmotic damage and membrane damage under drought stress by regulating content of proline.

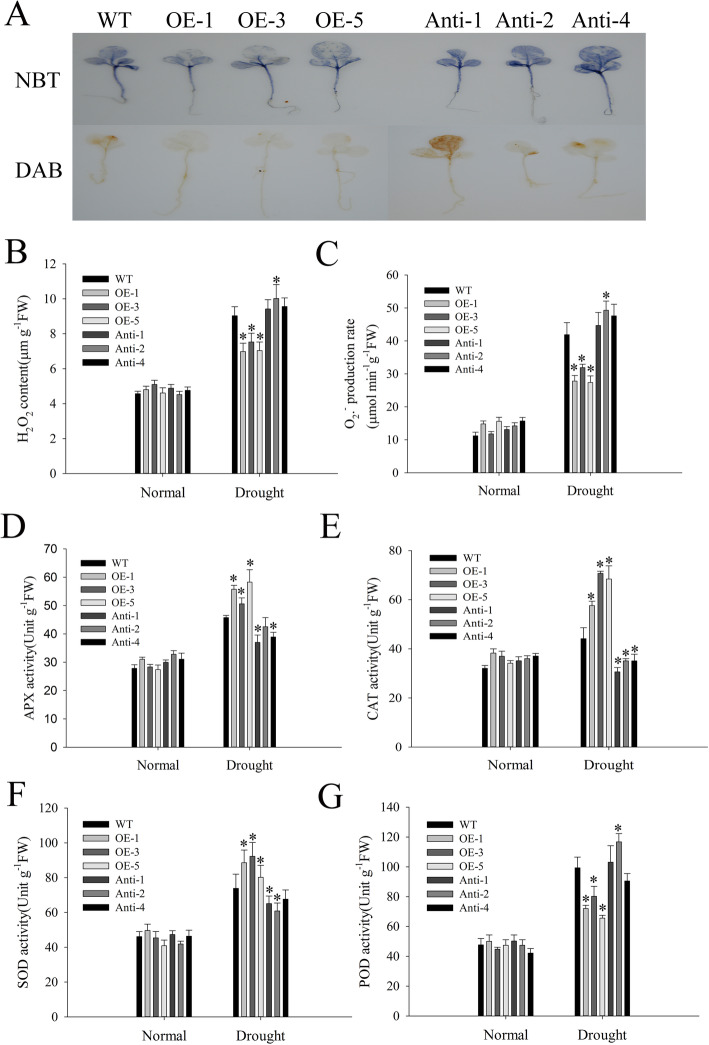

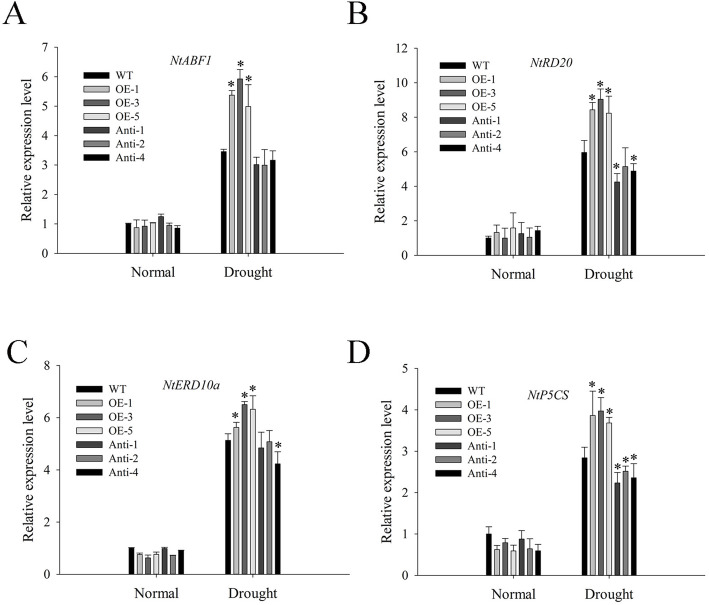

Drought can cause osmotic stress, which leads to ROS production [28]. We measured H2O2 and O2•− levels under drought stress, and found that the accumulation of H2O2 and O2•− were induced under drought stress; the content of H2O2 and O2•− were significantly higher in antisense than in WT and overexpressed plants, with the lowest content found in overexpressed plants (Fig. 7b, c). The results of the nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT) and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining were consistent with the results obtained from the quantitative analysis of H2O2 and O2•− levels (Fig. 7a). Further, we tested the antioxidant enzyme activities and found no difference in all plants before drought stress. Additionally, the antioxidant enzyme activities of APX, CAT, SOD, and POD were tested under drought stress. The results suggested that the activities of APX, CAT, and SOD in overexpressed were significantly higher than those of WT or antisense plants; however, the POD activities were lower than those of WT (Fig. 7d-g). These results showed that overexpression of NtMLP423 could regulate ROS levels by increasing the activities of APX, CAT and SOD. Moreover, we determined the expression of stress-related genes NtABF1 (ABA responsive element binding factor 1), NtRD20 (responsive to dehydration 20), NtERD10a (early responsive to dehydration 10) and NtP5CS under drought conditions by qPCR and found that overexpression of NtMLP423 increased expression of stress-related genes under drought stress, while the expression level of antisense were lower than that of WT (Fig. 8).

Fig. 7.

Overexpression of NtMLP423 affects ROS production and antioxidant enzyme activities of tobacco leaves under drought stress. a DAB and NBT staining under drought stress. b H2O2 content of leaves under drought stress. c Oxygen free radical generation rate under drought conditions. d-g Activities of antioxidant enzymes SOD, CAT, APX, and POD under drought stress, respectively. Data points represent means ± SE (n = 3). * indicate significant difference (*P < 0.05)

Fig. 8.

Transcript levels of stress-related genes NtABF1, NtRD20, NtERD10a and NtP5CS under drought stress. Data represent means ± SE (n = 3). * indicate significant difference relative to WT (*P < 0.05)

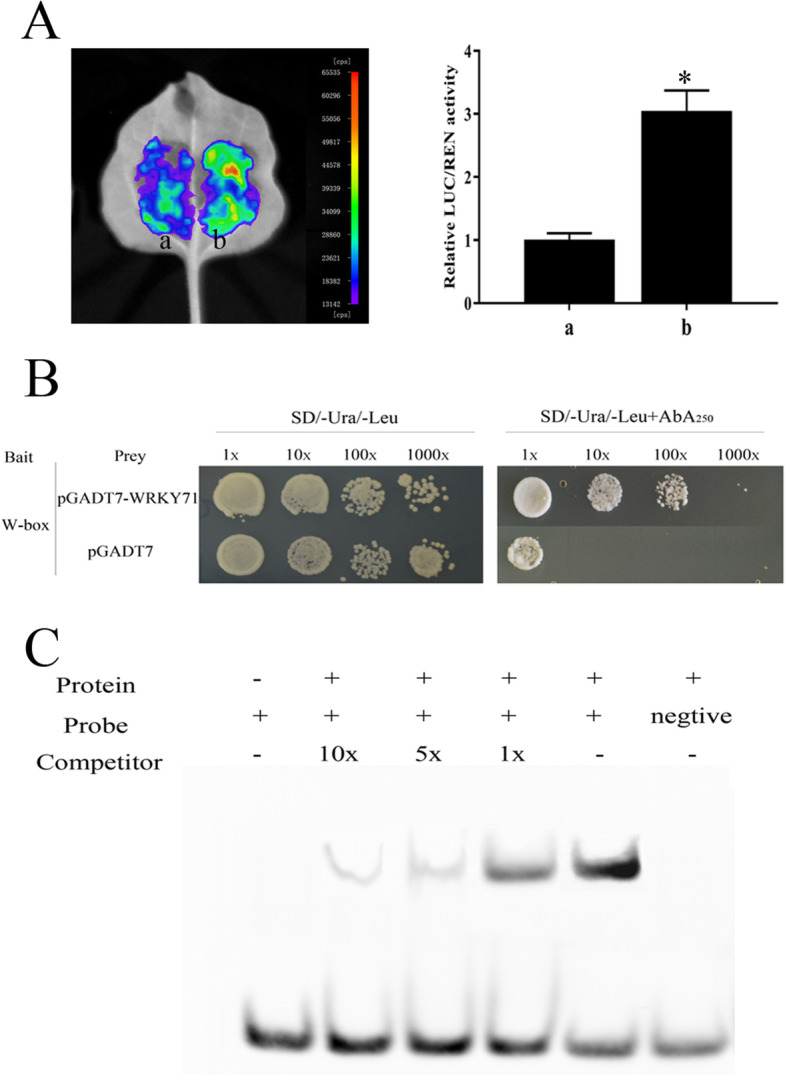

Transcription of NtMLP423 enhanced by NtWRKY71

To further elucidate the molecular regulatory mechanism of NtMLP423, bioinformatics analysis of the NtMLP423 promoter was performed and screened the transcription factor NtWRKY71 for potential binding to the NtMLP423 promoter. The firefly luciferase (Luc) complementation imaging assay were performed and observed that the fluorescence intensity increased after injection of NtWRKY71, indicating transactivation effects on the NtMLP423 promoter (Fig. 9a). Yeast one-hybrid (Y1H) assays were conducted to test whether NtWRKY71 could bind promoters of NtMLP423. W-box sequences were integrated into yeast cells, and the positive yeast cells were verified by gradient dilution on an SD/−Ura/−Leu-deficient medium containing aureobasidin A (AbA). The results showed that the yeast containing the bait vector pAbAi-W-box could grow normally at an AbA concentration of 250 ng/mL (Fig. 9b). Additionally, we used the DNA fragment containing the W-box sequence as a probe to validate NtWRKY71 binding to the NtMLP423 promoter, in EMSA experiments. The results suggested that NtWRKY71 was directly bound to W-box in the NtMLP423 promoter (Fig. 9c).

Fig. 9.

NtWRKY71 binds to the NtMLP423 promoter (A) NtWRKY71 regulates the activity of the NtMLP423 promoter. a: 62SK + pNtMLP423-LUC was used as the reference; b: NtWRKY71-62SK + pNtMLP423-LUC. The vectors were infiltrated into tobacco leaves by Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 and then observed by firefly luciferase complementation imaging. Detection of LUC/REN activity verified that NtWRKY71 activated the NtMLP423 promoter. Data points represent means ± SE (n = 3). * indicated significant difference (P < 0.05). b Yeast one-hybrid analysis showing that NtWRKY71 was bound to W-box in the NtMLP423 promoter. c EMSA showing that the NtWRKY71 fusion protein was directly bound to the NtMLP423 promoter on W-box in vitro

Discussion

At present, research exploring the characteristics of MLP gene expression mainly focuses on its role in responses to abiotic and biotic stress. Studies have reported that expression of three MLP genes is significantly down-regulated after oxidative stress [29], and MLP was detected in the stem phloem juice of melon infected with the cucumber mosaic virus [30]. Additionally, the GhMLP28 gene can respond to pathogens [31], and significant differences in MLP gene family expression have been shown to occur among different tissues. In our study, the NtMLP423 gene was expressed at the highest level in leaves and roots and was significantly induced after PEG treatment (Fig. 1). The results showed that NtMLP423 may participate in response of tobacco to drought stress. This was verified using overexpressing NtMLP423 plants; overexpressing NtMLP423 showed a lower wilting and a higher survival rate than WT under drought stress (Fig. 2a, 5, S5). The results indicated that NtMLP423 positively regulated drought resistance.

Stomatal closure played an important role in adapting to drought stress, and ABA played a key role in regulating stomatal closure [32]. In this study, we showed that overexpressing transgenic plants exhibit ABA hypersensitivity, including ABA-induced inhibition of seed germination and ABA-induced promotion of stomatal closure (Figs. 2c and 3). The efficiency of water loss is related to drought stress tolerance, as water loss rapidly increases sensitivity to drought [33]. RWC of overexpressing NtMLP423 was higher than that of WT, but the water loss rate and osmotic potential were significantly lower; this high water retention capacity benefitted transgenic plants by enhancing their drought tolerance (Fig. 5b-c, S8). Studies showed that the accumulation of ABA could improve drought resistance, thereby decreasing stomatal opening and water loss under drought conditions [34].

ABA content of overexpressing NtMLP423 increased significantly under drought stress and was higher than that of WT (Fig. 4a); this indicates that NtMLP423 is involved in ABA accumulation. ABA is a major signaling molecule participated in drought response, and many genes related to ABA biosynthesis have been identified [9, 35]. The NCED enzyme is important to ABA biosynthesis and has been shown to play a key role in drought stress response in Arabidopsis [36]. We analyzed expression of ABA synthetic genes (ABA2, AAO3, and NCED3), and found that they were upregulated (Fig. 4). The results showed that NtMLP423 positively regulates ABA signaling and ABA accumulation by regulating ABA biosynthesis.

Photosynthesis is the basis for the survival of the biological world. Drought stress can inhibit photosynthesis in plants by destroying the photosynthetic system reaction center, which results in reduced photosynthetic efficiency. The photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll is crucial to photosynthesis in plants [37, 38]. We found that the contents of Pn and chlorophyll decreased under drought stress, with the greatest decrease recorded in the antisense plants and the least in overexpressed plants and the same results were found for the Fv/Fm ratio (Fig. 6a-c). The results indicate that overexpression of NtMLP423 increases photosynthesis of tobacco under drought stress.

The final breakdown product of membrane lipid peroxidation is MDA, which is widely used to assess oxidative lipid damage under abiotic stress [39]. Previous studies showed that plant resistance to abiotic stress is closely related to physiological responses, mainly due to accumulation of osmoregulatory substances such as free proline [40]. Accumulation of free proline contributes to drought tolerance, thereby protecting cells from damage [41, 42]. Our results showed a much greater accumulation of free proline and a much lower accumulation of MDA in plant lines that overexpress NtMLP423 than in WT (Fig. 6d, f). This demonstrates that overexpression of NtMLP423 enhances the plants’ osmotic adjustment capability and alleviates damage to membrane lipids.

As direct or indirect inducers of a variety of genes which participate in stress response, ROS can serve as signaling molecules [43, 44]. Drought stress triggers the accumulation of ROS, which, in excess, could cause damage to plant cell membranes. Removal of ROS is important for plant survival under drought stress; therefore activity of antioxidant enzymes can maintain the balance of reactive oxygen metabolism and protect membrane system [45–47]. Our experimental results showed ROS accumulation under drought stress; however, ROS level of overexpressing was lower than that of WT and antisense plants (Fig. 7a-c). There is evidence indicating that ABA-enhanced drought stress tolerance is related to antioxidant enzymes [48]. The activities of SOD, CAT, and APX enzymes following drought stress were higher in NtMLP423-overexpressing than in other experimental groups (Fig. 7d-g). The results showed that NtMLP423 participates in ROS-mediated drought response, and that NtMLP423 can eliminate the negative effects of excessive ROS production under drought stress, thereby enhancing drought tolerance. NtABF1 and NtRD20 are drought stress responses genes. NtP5CS is a key gene in proline biosynthesis, whereas NtERD10a is a gene encoding late embryogenesis abundant proteins and is involved in regulating drought stress [24, 32, 49]. Expression levels of stress-related genes by qPCR were examined and found that overexpressed lines increased drought tolerance by upregulating stress-related genes (NtABF1, NtRD20, NtERD10a, and NtP5CS) (Fig. 8).

There is little research on the transcription factors regulating NtMLP423. Here, we screened a novel transcription factor, NtWRKY71. Y1H and EMSA assays were determined to test whether NtWRKY71 can bind promoter of NtMLP423. The results indicated that NtWRKY71 regulated the transcription of NtMLP423 and directly bound W-box in the NtMLP423 promoter (Fig. 9). The WRKY transcription factors comprise a large family of transcriptional regulators that play a key role in biotic stress response, ABA signaling, and physiological and biochemical processes [50, 51]. The regulation of NtMLP423 by NtWRKY71 was also a factor in improving drought resistance.

Conclusions

As determined by physiological indicators and the expression levels of drought-related genes, overexpression of NtMLP423 increased drought tolerance in Arabidopsis and tobacco. According to our results, NtMLP423 is a gene that can positively regulate drought tolerance, is also conducive to improving the tolerance of plants to adversity and has potential applications in agricultural production.

Methods

Plant materials, seed germination assays, and drought treatment

Arabidopsis thaliana (ecotype Columbia) and Nicotiana tabacum cv. NC89 were used in the study. Arabidopsis thaliana (ecotype Columbia) plants were got from Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC), and seeds of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum cv. NC89) were stored in our laboratory. The plants seeds were sown on MS medium and germination assays were performed without and with ABA (0.5 and 1 μM) or mannitol (150 and 200 mM).

To study the effects of drought stress on Arabidopsis and tobacco, we conducted both simulated and natural-drought experiments using the seedlings obtained from the procedure outlined above. To simulated drought treatment, the roots of both Arabidopsis (8-week-old) and tobacco (4-week-old) were treated with 20% PEG for 7 days. For the natural-drought treatment, watering was discontinued for 14 days and the plant phenotypes were observed for 3 days after re-watering.

For Arabidopsis, three pots each of transgenic (OE1–1, OE4–1, and OE7–1) and WT lines were used, with four plants from the same line in each pot. For tobacco, three pots each of T2-generation overexpressing NtMLP423 (OE-1, OE-3, and OE-5), antisense transgenic (Anti-1, Anti-2, and Anti-4) lines, and WT were used, with one plant per pot. Each pot of each treatment was considered one biological replicate. Overall, 12 and 21 pots were used for each treatment of Arabidopsis and tobacco, respectively.

Generation of transgenic plants

Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends (RACE) was used for cDNA cloning, using the GSP1 and NGSP1 primers used for the first round of RACE PCR reactions and nested PCR reactions (Table S1). The NtMLP423 sequence was amplified with NtMLP423F and NtMLP423R primers (Table S1). The complete NtMLP423 coding sequence was fused in a sense or antisense orientation, in PBI121 vector driven by CaMV 35S promoter. The sense and antisense expression vectors were obtained and transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 and LBA4404. Tobacco transformation was carried out by leaf disc method, while the floral dip method was used for transformation of Arabidopsis.

Subcellular localization of NtMLP423 protein

The NtMLP423 and green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion expression vector was constructed and the vector was introduced into A. tumefaciens [52], which was then injected into leaves of N.benthamiana [53]. Confocal imaging was used a high-resolution confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss LSM880, Germany).

Gene expression analysis

Rosette leaves of 8-week-old Arabidopsis and leaves of 4-week-old tobacco grown in soil without and with 7 days of drought treatment were sampled. Table S1 lists the primers used in real-time quantitative PCR experiments. The qRT-PCR study was conducted on the Quantitative PCR CFX96–3 detection system (Bio-Rad, USA) with three biological replicates.

Stomatal aperture measurement

Eight-week-old Arabidopsis rosette leaves were incubated in a solution (50 mM KCl, 10 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM MES-KOH) for 3 h for ABA sensitivity analysis. ABA was added into incubation solution and then stomatal aperture was observed with a fluorescence microscope (AX10, Zeiss, Germany) after treatment with ABA for 1 h [33].

Relative water content and water loss rate

Relative water content (RWC) and water loss rate were measured after Gaxiola et al. [54].

ABA content measurements

To determine ABA content, 50 mg Arabidopsis rosette leaves grown under normal conditions and following 7 days of drought stress were sampled. ABA was extracted with 70% methanol and 0.1% formic acid and ABA content was determined according to Wang et al. [9].

Proline contents and malondialdehyde (MDA) contents

Proline and MDA contents were performed as described by Zhang et al. [55].

ROS contents and antioxidant enzyme activities

The H2O2 and O2•− contents were determined according to the description of Kong et al. [56]. Activities of antioxidant enzymes were determined according to method of Wang et al. [57].

Chlorophyll content measurement

Chlorophyll contents were performed according to the description of Wang et al. [24].

Net photosynthetic rate and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters

Photosynthesis rate (Pn) was determined using portable photosynthesis measuring system (Ciras-3, PP Systems International, Hertfordshire, UK). Leaf maximum photochemical-efficiency was measured after steady state attainment in the dark for 30 min at 25 °C using a portable fluorometer (FMS-2, Hansatech, UK).

Dual-luciferase assay

Dual-luciferase assay was carried out according to the description of An et al. [58]. The NtMLP423 promoter was inserted into pGreenII0800-LUC vector, whereas NtWRKY71 was inserted into pGreenII62-SK vector. All vectors were transformed into A. tumefaciens GV3101 and infiltrated into N. benthamiana leaves. Luminescence signals were observed by firefly luciferase complementation imaging (Xenogen, USA).

Yeast one-hybrid assay

Interaction between the transcription factor and NtMLP423 promoter was verified by the Y1H assay as described by Zhu et al. [59].

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA)

EMSA experiments were carried out as described by An et al. [58].

Statistical analysis

Data represent means ± SE of three biological replicates and SPSS software was used for statistical analysis. * indicates significantly different at P < 0.05, ** indicates significantly different at P < 0.01, relative to the WT.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1 Table S1. Primers for gene amplification and qRT-PCR.

Additional file 2 Fig. S1 (A)-(C) Subcellular localization of NtMLP423-GFP fusion protein. Fig. S2 Relative expression of stresses reference marker genes under ROS, ABA, and drought stress. Expression level of NtDEFL (A), NtABI5 (B) and NtP5CS (C) treated with MV, 100 μM ABA and 20% PEG, respectively. Data represent means ± SE (n = 3). * indicate significant difference relative to 0 h (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Fig. S3. Identification of transgenic Arabidopsis plants. (A) PCR identification of transgenic plants, M: DL2000 marker. 1–7: OE1–1, OE2–1, OE3–1, OE4–1, OE5–1, OE6–1, and OE7–1 lines, respectively. (B) Expression level of NtMLP423 in transgenic Arabidopsis. Data represent means ± SE (n = 3). * indicate significant difference relative to WT (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Fig. S4 NtMLP423 participated in drought response in seed germination assay in Arabidopsis. (A) Germination of Arabidopsis seed on MS medium and with mannitol medium. (B) Statistics of germination rate under mannitol treatment. (C) Length of primary roots after mannitol treatment. (D) Statistical analysis of root length. Data represent means ± SE (n = 3). * indicate significant difference relative to WT (*P < 0.05). Fig. S5 The NtMLP423 gene is involved in drought stress responses in Arabidopsis. (A) Phenotypic observation of plants treated with 20% PEG for 7 days. (B) RWC in Arabidopsis under drought stress. (C) Osmotic potential in Arabidopsis leaves under drought stress. Data represent means ± SE (n = 3). * indicate significant difference relative to WT (*P < 0.05). Fig. S6 Genes expression is involved in ABA catabolism pathway in Arabidopsis under drought stress. Data represent means ± SE (n = 3). * indicate significant difference relative to WT (*P < 0.05). Fig. S7 Expression levels of NtMLP423 in transgenic tobacco. (A) Expression level analysis of NtMLP423-overexpressing transgenic tobacco. (B) Expression level analysis of antisense transgenic tobacco. Data represent means ± SE (n = 3). * indicate significant difference (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Fig. S8 Osmotic potential of tobacco leaves under drought stress. Data represent means ± SE (n = 3). * indicate significant difference relative to WT (*P < 0.05).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ABA

Abscisic acid

- GFP

Green fluorescent protein

- MLP

Major latex protein

- MDA

Malondialdehyde

- MS

Murashige and skoog

- Pn

Net photosynthetic rate

- NBT

Nitro blue tetrazolium

- PEG

Polyethyleneglycol

- RWC

Relative water content

- Fv/Fm

Variable fluorescence/maximum fluorescence

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- WT

Wild type

- Y1H

Yeast one-hybrid

- EMSA

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays

Authors’ contributions

YZ conceived and designed the research. HL performed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. HL, XM and SL analyzed the data. BD, NC and YW revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31370359) and funds of Shandong “Double Tops” Program [grant number SYL2017YSTD01 to Y.W.]. Funds were used for the experimental conduction and the open access payment. The funding agency did not participate in the design of the study, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Tobacco genes sequences in this research were downloaded from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The primers for qRT-PCR used in this research were designed in Primer5 software and the specific primers for qRT-PCR are listed in supplementary table. The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12870-020-02690-z.

References

- 1.Choudhury FK, Rivero RM, Blumwald E, Mittler R. Reactive oxygen species, abiotic stress and stress combination. Plant J. 2017;90:856–867. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakashima K, Tran LSP, VanNguyen D, Fujita M, Maruyama K, Todaka D. Functional analysis of a NAC-type transcription factor OsNAC6 involved in abiotic and biotic stress-responsive gene expression in rice. Plant J. 2007;51(4):617–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raghavendra AS, Gonugunta VK, Christmann A, Grill E. ABA perception and signaling. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15(7):395–401. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campos-Rivero G, Osorio-Montalvo P, Sanchez-Borges R, Us-Camas R, Duarte-Ake F, De-la-Pena C. Plant hormone signaling in flowering: an epigenetic point of view. J Plant Physiol. 2017;214:16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2017.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee SC, Luan S. ABA signal transduction at the crossroad of biotic and abiotic stress responses. Plant Cell Environ. 2012;35(1):53–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang H, Liu Y, Wen F, Yao D, Wang L, Guo J. A novel rice C2H2-type zinc finger protein, ZFP36, is a key player involved in abscisic acid-induced antioxidant defence and oxidative stress tolerance in rice. J Exp Bot. 2014;65(20):5795–5809. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eru313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ren ZZ, Wang Z, Zhou XE, Shi HZ, Hong YC, Cao MJ, Chan ZL, Liu X, Xu XE, Zhu JK. Structure determination and activity manipulation of the turfgrass ABA receptor FePYR1. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):14022. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14101-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edel KH, Kudla J. Integration of calcium and ABA signaling. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2016;33:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2016.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Z, Wang FX, Hong YC, Yao JJ, Ren ZZ, Shi HZ, Zhu JK. The flowering repressor SVP confers drought resistance in Arabidopsis by regulating Abscisic acid catabolism. Mol Plant. 2018;11(9):1184–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2018.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan BC, Joseph LM, Deng WT, Liu LJ, Li QB, Cline K, McCarty DR. Molecular characterization of the Arabidopsis 9-cis epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase gene family. Plant J. 2003;35(1):44–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nambara E, Kawaide H, Kamiya Y, Naito S. Characterization of an Arabidopsis thaliana mutant that has a defect in ABA accumulation: ABA-dependent and ABA-independent accumulation of free amino acids during dehydration. Plant Cell Physiol. 1998;39:853–858. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seo M, Peeters AJM, Koiwai H, Oritani T, Marion-Poll A, Zeevaart JAD, Koornneef M, Kamiya Y, Koshiba T. The Arabidopsis aldehyde oxidase 3 (AA03) gene product catalyzes the fifinal step in abscisic acid biosynthesis in leaves. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2000;97(23):12908–12913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220426197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nessler CL, Burnett RJ. Organization of the major latex protein gene family in opium poppy. Plant Mol Biol. 1992;20(4):749–752. doi: 10.1007/BF00046460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nessler CL, Kurz WG, Pelcher LE. Isolation and analysis of the major latex protein genes of opium poppy. Plant Mol Biol. 1990;15(6):951–953. doi: 10.1007/BF00039436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aggelis A, John I, Karvouni Z, Grierson D. Characterization of two cDNA clones for mRNAs expressed during ripening of melon (Cucumis melo L) fruits. Plant Mol Biol. 1997;33(2):313–322. doi: 10.1023/A:1005701730598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu FZ, Lu TC, Shen Z, Wang BC, Wang HX. N-terminal acetylation of two major latex proteins from Arabidopsis thaliana using electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Plant Mol Biol Rep. 2008;26(2):88–97. doi: 10.1007/s11105-008-0027-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heimo B, Peter L, Christian R. The bet v 1 fold: an ancient, versatile scaffold for binding of large, hydrophobic ligands. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8(1):286. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang N, Li R, Shen W. Genome-wide evolutionary characterization and expression analyses of major latex protein (MLP) family genes in Vitis vinifera. Mol Gen Genomics. 2018;18:1440–1447. doi: 10.1007/s00438-018-1440-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo D, Wong WS, Xu WZ, Sun FF, Qing DJ, Li N. Cis-cinnamic acid-enhanced 1 gene plays a role in regulation of Arabidopsis bolting. Plant Mol Biol. 2011;75:481–495. doi: 10.1007/s11103-011-9746-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chruszcz M, Ciardiello MA, Osinski T, Majorek KA, Giangrieco I, Font J, Breiteneder H, Thalassinos K, Minor W. Structural and bioinformatic analysis of the kiwifruit allergen act d 11, a member of the family of ripening-related proteins. Mol Immunol. 2013;56(4):794–803. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen JY, Dai XF. Cloning and characterization of the Gossypium hirsutum major latex protein gene and functional analysis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2010;231(4):861–873. doi: 10.1007/s00425-009-1092-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suyama T, Yamada K, Mori H. Cloning cDNAs for genes preferentially expressed during fruit growth in cucumber. J Amer Soc Horti Sci. 1999;124(2):136–139. doi: 10.21273/JASHS.124.2.136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skubacz A, Daszkowska-Golec A, Szarejko I. The role and regulation of ABI5 (ABA-insensitive 5) in plant development, Abiotic Stress Responses and Phytohormone Crosstalk. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1884. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang S, Zhuang K, Zhang S, Yang M, Kong F, Meng Q. Overexpression of a tomato carotenoid ε-hydroxylase gene ( sllut1 ) improved the drought tolerance of transgenic tobacco. J Plant Physiol. 2018;222:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gadjev I, Vanderauwera S, Gechev TS, Laloi C, Minkov IN, Shulaev V, Apel K, Inzé D, Mittler R, Van BF. Transcriptomic footprints disclose specificity of reactive oxygen species signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2016;141:436–445. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.078717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finkelstein RR, Gampala SSL, Rock CD. Abscisic acid signaling in seeds and seedlings. Plant Cell. 2002;14:15–45. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rejeb KB, Abdelly C, Savoure A. How reactive oxygen species and proline face stress together. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2014;80:278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krasensky J, Jonak C. Drought, salt, and temperature stress induced metabolic rearrangements and regulatory networks. J Exp Bot. 2012;63:1593–1608. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim HS, Yu Y, Snesrud EC, Moy LP, Linford LD, Haas BJ, Nierman WC, Quackenbush J. Transcriptional divergence of the duplicated oxidative stress-responsive genes in the Arabidopsis genome. Plant J. 2005;41(2):212–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malter D, Wolf S. Melon phloem-sap proteome: developmental control and response to viral infection. Protoplasma. 2011;248(1):217–224. doi: 10.1007/s00709-010-0215-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang CL, Liang S, Wang HY, Han LB, Wang FX, Cheng HQ, Wu XM, Qu ZL, Wu JH, Xia GX. Cotton major latex protein 28 functions as a positive regulator of the ethylene responsive factor 6 in defense against Verticillium dahlia. Mol Plant. 2015;8:399–411. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2014.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang YP, Yang L, Chen X, Yel TT, Zhong B, Liu RJ, Wu Y, Chan ZL. Major latex protein-like protein 43 (MLP43) functions as a positive regulator during abscisic acid responses and confers drought tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Exp Bot. 2016;67(1):421–434. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J, Zhang L, Cao Y, Qi C, Li S, Liu L. Csataf1 positively regulates drought stress tolerance by aba-dependent pathway and promoting ros scavenging in cucumber. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018;59(5):930–945. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcy030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saradadevi R, Palta JA, Siddique KHM. ABA-mediated stomatal response in regulating water use during the development of terminal drought in wheat. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1251. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raghavendra AS, Gonugunta VK, Christmann A, Grill E. ABA perception and signalling. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:395–401. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frey A, Effroy D, Lefebvre V, Seo M, Perreau F, Berger A, Sechet J, To A. North HM, Marion-Poll A. Epoxycarotenoid cleavage by NCED5 fifine-tunes ABA accumulation and affects seed dormancy and drought tolerance with other NCED family members. Plant J. 2012;70(3):501–512. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathobo R, Marais D, Steyn JM. The effect of drought stress on yield, leaf gaseous exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence of dry beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Agric Water Manag. 2017;180:118–125. doi: 10.1016/j.agwat.2016.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Z, Jia Y, Gao H, Zhang L, Li H, Meng Q. Characterization of PSI recovery after chilling-induced photoinhibition in cucumber (cucumis sativusl.) leaves. Planta. 2011;234(5):883–889. doi: 10.1007/s00425-011-1447-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davey MW, Stals E, Panis B, Keulemans J, Swennen RL. High-throughput determination of malondialdehyde in plant tissues. Anal Biochem. 2005;347(2):201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sperdouli I, Moustakas M. Interaction of proline, sugars, and anthocyanins during photosynthetic acclimation of Arabidopsis thaliana to drought stress. J Plant Physiol. 2012;169(6):577–585. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller G, Suzuki N, Ciftci-Yilmaz S, Mittler R. Reactive oxygen species homeostasis and signaling during drought and salinity stresses. Plant Cell Environ. 2010;33(4):453–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garg AK, Kim JK, Owens TG, Ranwala AP, Yang DC, Kochian LV. Trehalose accumulation in rice plants confers high tolerance levels to different abiotic stresses. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99(25):15898–15903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252637799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Apel K, Hirt H. Reactive oxygen species: metabolism, oxidative stress and signal transduction. Ann Rev Plant Biol. 2004;55(1):373–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gill SS, Tuteja N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2010;48(12):909–930. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Farrant JM, Bailly C, Leymarie J, Hamman B, Come D, Corbineau F. Wheat seedlings as a model to understand the desiccation tolerance and sensitivity. Physiol Plantarum. 2004;120(4):563–574. doi: 10.1111/j.0031-9317.2004.0281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dutilleul C, Garmier M, Noctor G, Mathieu C, Chétrit P, Foyer CH, Paepe R. Leaf mitochondria modulate whole cell redox homeostasis, set antioxidant capacity, and determine stress resistance through altered signaling and diurnal regulation. Plant Cell. 2003;15(5):1212–1226. doi: 10.1105/tpc.009464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miura K, Okamoto H, Okuma E, Shiba H, Murata Y. Siz1 deficiency causes reduced stomatal aperture and enhanced drought tolerance via controlling salicylic acid-induced accumulation of reactive oxygen species in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2013;7(1):91–104. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mittler R, Vanderauwera S, Suzuki N, Miller G, Tognetti VB, Vandepoele K, Gollery M, Shulaev V, Van BF. ROS signaling: the new wave. Trends Plant Sci. 2011;16(6):300–309. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khurana P, Vishnudasan D, Chhibbar AK. Genetic approaches towards overcoming water deficit in plants-special emphasis on LEAs. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2008;14(4):277–298. doi: 10.1007/s12298-008-0026-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matsushita A, Inoue H, Goto S, Nakayam A, Sugano S, Hayashi N. The nuclear ubiquitin proteasome degradation affects WRKY45 function in the rice defense program. Plant J. 2013;73(2):302–313. doi: 10.1111/tpj.12035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wei W, Liang DW, Bian XH. GmWRKY54 improves drought tolerance through activating genes in ABA and Ca2+ signaling pathways in transgenic soybean. Plant J. 2019;100:384–398. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wise AA, Liu Z, Binns AN. Three methods for the introduction of foreign DNA into agrobacterium. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;343:43–53. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-130-4:43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang Y, Li R, Qi M. In vivo analysis of plant promoters and transcription factors by agroinfiltration of tobacco leaves. Plant J. 2000;22(6):543–551. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gaxiola RA, Li J, Undurraga S, Dang LM, Allen GJ, Alper SL. Drought- and salt-tolerant plants result from overexpression of the AVP1 H+-pump. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98(20):11444–11449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191389398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang M, Liu H, Wang Q, Liu SH, Zhang YH. The 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme a reductase 5 gene from Malus domestica enhances oxidative stress tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol Bioch. 2020;146:269–277. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kong FY, Deng YS, Zhou B, Wang GD, Wang Y, Meng QW. A chloroplasttargeted DnaJ protein contributes to maintenance of photosystem II under chilling stress. J Exp Bot. 2014;65:143–158. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang Y, Yang L, Zheng Z, Grumet R, Loescher W, Zhu JK. Transcriptomic and physiological variations of three Arabidopsis ecotypes in response to salt stress. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69036. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.An JP, Yao JF, Xu RR, You CX, Wang XF, Hao YJ. Apple bZIP transcription factor MdbZIP44 regulates ABA-promoted anthocyanin accumulation. Plant Cell Environ. 2018;41:2678–2692. doi: 10.1111/pce.13393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhu D, Hou L, Xiao P, Guo Y, Deyholos MK, Liu X. Vvwrky30, a grape wrky transcription factor, plays a positive regulatory role under salinity stress. Plant Sci. 2018;280:132–142. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1 Table S1. Primers for gene amplification and qRT-PCR.

Additional file 2 Fig. S1 (A)-(C) Subcellular localization of NtMLP423-GFP fusion protein. Fig. S2 Relative expression of stresses reference marker genes under ROS, ABA, and drought stress. Expression level of NtDEFL (A), NtABI5 (B) and NtP5CS (C) treated with MV, 100 μM ABA and 20% PEG, respectively. Data represent means ± SE (n = 3). * indicate significant difference relative to 0 h (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Fig. S3. Identification of transgenic Arabidopsis plants. (A) PCR identification of transgenic plants, M: DL2000 marker. 1–7: OE1–1, OE2–1, OE3–1, OE4–1, OE5–1, OE6–1, and OE7–1 lines, respectively. (B) Expression level of NtMLP423 in transgenic Arabidopsis. Data represent means ± SE (n = 3). * indicate significant difference relative to WT (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Fig. S4 NtMLP423 participated in drought response in seed germination assay in Arabidopsis. (A) Germination of Arabidopsis seed on MS medium and with mannitol medium. (B) Statistics of germination rate under mannitol treatment. (C) Length of primary roots after mannitol treatment. (D) Statistical analysis of root length. Data represent means ± SE (n = 3). * indicate significant difference relative to WT (*P < 0.05). Fig. S5 The NtMLP423 gene is involved in drought stress responses in Arabidopsis. (A) Phenotypic observation of plants treated with 20% PEG for 7 days. (B) RWC in Arabidopsis under drought stress. (C) Osmotic potential in Arabidopsis leaves under drought stress. Data represent means ± SE (n = 3). * indicate significant difference relative to WT (*P < 0.05). Fig. S6 Genes expression is involved in ABA catabolism pathway in Arabidopsis under drought stress. Data represent means ± SE (n = 3). * indicate significant difference relative to WT (*P < 0.05). Fig. S7 Expression levels of NtMLP423 in transgenic tobacco. (A) Expression level analysis of NtMLP423-overexpressing transgenic tobacco. (B) Expression level analysis of antisense transgenic tobacco. Data represent means ± SE (n = 3). * indicate significant difference (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). Fig. S8 Osmotic potential of tobacco leaves under drought stress. Data represent means ± SE (n = 3). * indicate significant difference relative to WT (*P < 0.05).

Data Availability Statement

Tobacco genes sequences in this research were downloaded from National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The primers for qRT-PCR used in this research were designed in Primer5 software and the specific primers for qRT-PCR are listed in supplementary table. The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.