Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by the accumulation of amyloid-beta (Aβ) senile plaques in patients’ brain tissues. Elevated levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-1beta (IL-1β) have been identified in cerebrospinal fluid of living AD patients and in animal models of AD. Increased expression of IL-1β and the accumulation of iron have been identified in microglial cells that cluster around amyloid plaques in AD mouse models and post-mortem brain tissues of AD patients. The goals of this study were to determine the effects of Aβ on the secretion of IL-1β by microglial cells and whether iron status influences this pro-inflammatory signaling cue. To accomplish this goal, immortalized microglial (IMG) cells were incubated with Aβ with or without the addition of iron. qRT-PCR and Western blot analyses showed that Aβ induces the expression and biosynthesis of IL-1β by IMG cells. These microglial cells secrete the mature form of IL-1β in a caspase-1 dependent manner as determined by ELISA. Incubation of IMG cells with iron provoked a greater pro-inflammatory response as measured by these assays. Inhibition of the iron transporter DMT1 protected IMG cells against Aβ-induced inflammation. Potentiation of Aβ-elicited IL-1β induction by FAC was also antagonized by ROS inhibitors, supporting the notion that DMT1-mediated iron loading and a subsequent increase in cellular ROS contribute to the inflammatory effects of Aβ in microglia. Immunoblots and immunofluorescence microscopy data indicated that the presence of iron enhances Aβ activation of NF-κB signaling to promote synthesis of IL-1β. These results support the hypothesis that Aβ stimulates IL-1β expression by activating NF-κB signaling in microglia cells. Most importantly, iron appears to exacerbate the pro-inflammatory effects of Aβ to increase IL-1β levels, most likely through ROS generation. Because IL-1β promotes neuronal degeneration, these results suggest that iron status can profoundly influence the pathogenesis of AD by altering production of this cytokine.

Keywords: Microglia, Iron, IMG (immortalized microglia) cells, Neuroinflammation, Alzheimer’s disease, Divalent Metal Transporter-1

Introduction

The selective accumulation of iron and in some cases, changes in iron-related proteins in the brain, are features of several sporadic and genetic neurological disorders including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and Huntington’s disease (HD) (Connor 1992, Loeffler D. A 1995, Bartzokis G 2000, Piñero and Connor 2000, Muhoberac and Vidal 2013, Ward et al. 2014, Xu et al. 2018). Such accumulation of iron in the brain is exacerbated with age and is often associated with chronic neuroinflammation, oxidative stress and cellular damage (Zecca et al. 2004, Ward et al. 2014). While iron is essential for neurological functions including myelination, synthesis of neurotransmitters and oxidative metabolism (Beard and Connor 2003, Todorich et al. 2009, Lill et al. 2012, Kim and Wessling-Resnick 2014, Nnah and Wessling-Resnick 2018), excess amounts may compromise these physiological processes since iron increases the concentration of damaging reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Ward et al. 2014). Homeostatic levels of iron must be maintained in the brain, and this process involves a number of iron-interacting and regulatory proteins including transferrin, ferritin, and divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) which mediates import of transferrin- and non-transferrin-bound iron into brain cells (Hentze et al. 2010, Wessling-Resnick 2010, Ward et al. 2014).

In the last decade, the role of iron in neuroinflammatory responses observed in AD has received a lot of attention, with much focus directed towards understanding the underlying cellular and molecular cues affected by aberrant brain iron metabolism. Iron has been shown to promote neurotoxic oligomerization of Aβ peptides and tau tangles to potentiate neuroinflammatory responses in AD (Yu et al. 2009, Belaidi and Bush 2016, Yang and Stockwell 2016, Peters et al. 2018, Lane et al. 2018). Such inflammatory responses involve the acquisition of extracellular iron by microglia and downregulation of iron-interacting proteins, leading to intracellular sequestration of iron in activated microglial cells (Thomsen et al. 2015, McCarthy et al. 2018).

Microglia are the CNS-resident macrophages charged with immunosurveillance of their microenvironment. Under normal conditions, activated microglia reduce Aβ accumulation and toxicity through phagocytosis and intracellular degradation of amyloid plaque components in brain tissues (Lee and Landreth 2010). Aberrant activation of these brain macrophages, as observed in AD, leads to the chronic release of pro-inflammatory cytokines including interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (Wang et al. 2015). Among these inflammatory cytokines, IL-1β is the prominent cytokine that is consistently identified in cerebrospinal fluid of AD patients and in animal models of AD (Griffin 2000, Griffin et al. 2006, Simard et al. 2006, White et al. 2017). Secreted IL-1β is known to enhance neuronal uptake of iron and also influences iron transport and metabolism in microglia and other immune cells (Urrutia et al. 2013, Thomsen et al. 2015, Holland et al. 2018).

IL-1β is considered a master regulator of neuroinflammation because it mediates expression of adhesion molecules and immune cell infiltration while upregulating the production of prostaglandins and other mediators of inflammation in the CNS (Basu et al. 2004, Kaushik et al. 2013). Secreted IL-1β stimulates its own production in an autocrine or paracrine manner by binding to its cognate interleukin-1 receptors expressed in microglial cells, further ensuring its constitutive production and amplification of pro-inflammatory signals (Rothwell JN and GN 2000, Toda et al. 2002). Since it plays a central role in orchestrating inflammatory responses, IL-1β gene expression, protein synthesis and maturation, and subsequent secretion by microglia are tightly regulated at multiple checkpoints. First, microglia and other immune cells express and process the immature protein pro-IL-1β, a biologically inactive precursor of IL-1β. Induction of pro-IL1β is controlled by the transcription factor NF-κB whose nuclear translocation can be triggered by the activation of toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling (Tschopp and Schroder 2010, White et al. 2017). TLRs are transmembrane pattern recognition receptors that mediate innate immune response (D’Ignazio et al. 2016). Among members of the TLR family, TLR2 and TLR4 have been shown to transduce the Aβ signal and if necessary, may compensate for each other (Udan et al. 2008). Induction of nuclear NF-κB involves the degradation of a family of NF-κB-inhibiting proteins known as IκBs. IκBs are phosphorylated by IκB kinase (IKK) complexes downstream of TLRs and are subsequently ubiquitinated and targeted for proteasomal degradation. This, in turn, liberates NF-κB and promotes its translocation into the nucleus to activate the expression of target genes including IL-1β (D’Ignazio et al. 2016). After its induction and expression, the pro-IL-1β protein further undergoes a post-translational modification involving a proteolytic cleavage by the protease caspase-1 to generate matured IL-1β (Martinon et al. 2006, Weber et al. 2010). Activation of caspase-1 is carried out by NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) protein, a member of the inflammasome multiprotein complex involved in the inflammatory response (D’Ignazio et al. 2016). Aberrant NLRP3 activation can also propagate neuroinflammation by generating toxic levels of IL-1β to impede microglia-mediated clearance of Aβ plaques, further indicating the crucial role of this cytokine in AD pathogenesis (Heneka et al. 2013, Gold and El Khoury 2015). Activation of NF-κB and inflammasome signaling is mediated in part by mitochondrial ROS (mROS) (Takada et al. 2003, Park et al. 2015, Forrester et al. 2018). Interestingly, inflammatory stimulants that induce NF-κB signaling, such as bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), increase mROS production and upregulate DMT1-mediated iron uptake in microglial cells (Park et al. 2015, McCarthy et al. 2018), implicating a potential role for dysregulated iron metabolism in neuroinflammation.

Recent reports have demonstrated that in vivo, reactive and iron-containing microglial cells associate with senile plaques in brain tissues of patients and AD mouse models (Gallagher et al. 2012, Meadowcroft et al. 2015, Zeineh et al. 2015). Aβ(1–42), the main component of senile plaques, was reported to stimulate secretion of IL-1β and expression of proteins necessary for uptake and sequestration of extracellular iron in microglia (Terrill-Usery et al. 2014, McCarthy et al. 2018, McIntosh et al. 2019). This evidence links microglial iron handling to neuroinflammation, however, the molecular mechanism underlying the inflammatory role of iron in AD is still unclear. Therefore, we sought to determine the influence of microglial iron on inflammatory signaling cues induced by Aβ to promote expression, processing and secretion of IL-1β using the immortalized microglial (IMG) cell line (McCarthy et al. 2016). Our results show that while Aβ induces IL-1β production by IMG cells, the addition of iron provokes an even stronger pro-inflammatory response. Mechanistically, the presence of iron enhances the activation of NF-κB signaling pathway by Aβ to promote expression of IL-1β in microglia. Thus, our findings demonstrate that iron accumulation exacerbates neurodegeneration by enhancing neuroinflammation induced by Aβ.

Methods

Cell culture and reagents:

IMG cell line was previously characterized by McCarthy et al. (2016) and was subsequently made commercially available through Millipore (Cat. #SCC134, RRID:CVCL_HC49) and Kerafast (Cat. #EF4001). It was last authenticated by Millipore on August 30, 2018 by a Contamination Clear panel at Charles River Animal Diagnostic Services to verify its origin and to confirm the absence of inter-specie contamination. Origin of the cells was confirmed by Charles River using a Mouse Essential CLEAR panel. This cell line is not listed on the International Cell Line Authentication Committee (ICLAC) database of misidentified cell lines.

IMG cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with high glucose (4.5 g/L) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2.5mM glutamine and 100U/mL penicillin/streptomycin. A maximum of 10 passages were used for this cell line. Caspase-1 inhibitor Ac-YVAD-cmk (Cat. #SML0429), Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (Cat. #A-7699), Dimethyl malonate (DMM) (Cat. #136441), and N-Acetylcysteine (NAC) (Cat. #A7250) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Phenol red-free Ham’s F12 medium was supplied by Caisson labs (Cat. #HFL05). Ferric ammonium citrate (Cat. #ICN15804090) was supplied by Fisher Scientific. Salicylaldehyde-isocotinoyl-hydrazone (SIH) was a kind gift of Dr. Prem Ponka (McGill University).

Preparation of Aβ:

Aβ(1–42) and scrambled Aβ(1–42) were prepared as previously described in Pan et al. (2011) and McCarthy et al. (2016). Briefly, hexafluoroisopropanol-treated amyloid-beta peptides were purchased from rPeptide (Cat. #A-1163-2 and Cat. #A-1004-1,respectively Watkinsville, GA) and resuspended in DMSO to 5mM. The solution was sonicated in a water-bath sonicator for 10 minutes and then diluted to a final concentration of 200μM in phenol red-free Ham’s F-12 media and incubated in 4°C for 24 hours. The presence of oligomeric and fibrillar Aβ1–42 in the preps was assessed by dot blot analyses using species-specific antibodies: anti-amyloid beta fibrils (OC) (Rockland, Cat. #200-401-E87), anti-amyloid beta oligomers (A11) (Rockland, Cat. #200-401-E88) and anti-amyloid beta (4G8) (Biolegend, Cat. #80070).

Endotoxin testing:

Aβ preps were tested for contamination using a chromogenic endotoxin kit (ThermoScientific, Cat. #A39552S, 2018). Per the manufacturer’s instructions, all reagents and standards were prepared on the day of the assay. OD405 nm was measured using a BioTek Synergy 2 spectrophotometer (Winooski, VT). A standard curve was used to determine the endotoxin concentration which was less than the limit of detection (0.01 EU/ml).

Immunoblotting procedures:

Following the treatments detailed in figure legends, IMG cells were rinsed with ice-cold phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH 7.4) and lysed with ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer, pH 8.5, containing 25mM Tris-HCl, 150mM NaCl, 5mM EDTA, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS. RIPA buffer was supplemented with protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (ThermoScientific, #A32961, 2018 and 2019) before use. Lysed samples were centrifuged for 15 minutes at 17,000g, and supernatants were then transferred to fresh tubes. Protein concentration was determined using the bicinchoninic acid assay kit (ThermoScientific, Cat. #23228, 2019). Forty μg of protein was mixed with SDS-PAGE sample buffer and heated for 5 minutes at 95°C, cooled on ice and then resolved in 4–20% (w/v) SDS-PAGE. The proteins were transferred to 0.2μm pore-sized nitrocellulose membrane using a Trans-Blot Turbo transfer system (Bio-Rad). The resulting membranes were then blocked for 1 hour at room temperature in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) buffer containing 5% (w/v) milk. After blocking, membranes were washed three times in TBS buffer plus 0.05% Tween 20 (TBST) and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies diluted in TBST plus 5% milk to detect IL-1β (R and D Systems, Cat. #AF-401-NA, RRID:AB_416684, 1:1000), β-tubulin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Cat. #SC-5274, RRID: AB_2288090, 1:2000), L-Ferritin (Abcam, Cat. #ab69090, RRID:AB_1523609, 1:1000), NFκB (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat. #8242, RRID:AB_10859369, 1:1000), IκBα (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat. #4812, RRID:AB_10694416, 1:1000), phospho-IκBα (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat. #2859, RRID:AB_561111, 1:1000), GAPDH (Sigma Aldrich, Cat. #98795, 1:2000), or lamin B1 (Abcam, Cat. #ab16048, RRID:AB_10107828, 1:1000). Membranes were then washed three times in TBST and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour with Li-Cor secondary antibodies IRDye 800CW or 680RD donkey anti-mouse, anti-rabbit or anti-goat IgG (LI-COR Biosciences, Cat. #926–68072, RRID:AB_10953628; Cat. #926–68073, RRID:AB_10954442; Cat. #926–32224, RRID:AB_1575081; Cat. #926–32213, RRID:AB_621848; 1:5000) in TBST plus 5 % milk. The membranes were washed three times with TBST and imaged using Li-Cor Odyssey 2.1 infrared detection technology. Image Studio version 5.2 (LI-COR Biosciences) software was used to analyze the data.

Immunocytochemistry:

IMG cells were grown on poly-D-lysine-coated coverslips and then treated as described in the figure legend. After treatments, the cells on coverslips were rinsed with PBS and fixed for 15 minutes with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature. After fixation, cells were rinsed with PBS and then permeabilized at room temperature for 5 minutes in PBS solution containing 0.5% Triton X-100. Cells were then blocked for 1 hour at room temperature in PBS solution containing 5% normal goat serum, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1% bovine serum albumin and 0.3M glycine. Cells were then incubated overnight at 4°C with a rabbit anti-NF-κB/p65 primary antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Cat. #8242, RRID:AB_10859369, 1:500) diluted in blocking buffer. The next day the cells were washed with PBS, incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (Invitrogen, Cat. #32731; 1:1000) for 1 hour at room temperature. After secondary antibody incubation, cells were washed with PBS and mounted onto glass slides using a fluorescent mounting medium (DakoCytomation, Cat. #S3023). Images were obtained using a Zeiss Cell Observer spinning disc confocal microscope system (Carl Zeiss, Germany). ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD) was used to analyze images.

Cell viability assay:

Viability of cells was determined using the TOX-1 assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich). IMG cells were first exposed to Aβ with or without FAC at concentrations indicated in the figure legend for 16 hours then incubated for 4 hours with 0.5 mg/ml 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT). The resulting formazan crystals were dissolved in isopropanol alcohol containing 0.1N HCL. Absorbance was then measured at 570nm using a BioTek Synergy 2 plate reader, and viability of the cells normalized to control (untreated) cells.

DMT1 siRNA knockdown:

IMG cells were grown overnight on poly-D-lysine-coated tissue culture plates. Cells were transfected the next day with ONTARGET plus SMARTpool siRNA for mouse DMT1 (GE Dharmacon, #L-047945-01-0005) or control (scrambled) siRNAs (GE Dharmacon, #D-001810-01-05) as described in the Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent protocol (Life Technologies, Cat. #13778–075). The knockdown efficiency was validated by immunoblot using anti-DMT1 antibody (a kind gift from Dr. Jerry Kaplan, University of Utah).

Quantitative RT-PCR:

TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Cat. #15596–018, 2018 and 2019) was used to extract total RNA from IMG cells according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Subsequent on-column purification and DNase treatment of RNA samples were carried out using a Direct-zol RNA Miniprep kit (Zymo Research, Cat. #11–330, 2018 and 2019) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Purified RNA was then reverse transcribed into cDNA using the Verso cDNA synthesis kit (ThermoScientific, Cat. #AB-1453/B, 2018 and 2019) with anchored oligo dT primers. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) was carried out using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-rad, Cat. #172–5120, 2018 and 2019) and the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system (Life Technologies). Primers used for qPCR: mouse 36B4 Forward-TCATCCAGCAGGTGTTTGAC; Reverse-TACCCGATCTGCAGACACAC, mouse IL-1β Forward-AGCTTCAGGCAGGCAGTATC; Reverse-AAGGTCCACGGGAAAGACAC. 36B4 was used as an internal control in all the qPCR experiments. Thermal cycling parameters used for IL-1β qPCR in a StepOnePlus system were: 95°C for 1 min (holding), 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 seconds, 55°C for 15 seconds and 68°C for 30 seconds for denaturation, annealing and extension respectively.

Nuclear fractionation:

Cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts were obtained using a nuclear fractionation kit supplied by Thermo Scientific (Cat. #78835, 2019). In a poly-D-lysine-treated six-well tissue culture dish, IMG cells were incubated with normal growth media containing Aβ with or without FAC for the indicated time points in a 37°C and 5% CO2 incubator. Following the manufacturer’s instructions, adherent cells were harvested with trypsin-EDTA and then centrifuged at 500g for 5 minutes. Pelleted cells were then washed with PBS and counted. Approximately 2 × 106 cells were transferred to a 1.5mL microcentrifuge tube and pelleted by centrifugation at 500 × g for 3 minutes. 100μL of ice-cold cytoplasmic extraction reagent I was added to the cell pellet and the tube vortexed vigorously for 15 seconds to fully suspend the cell pellet. The tube was then incubated on ice for 10 minutes and then 5.5μL of cytoplasmic extraction reagent II was added to the tube, vortexed for 5 seconds and incubated on ice for 1 minute. The cell suspension was then centrifuged for 5 minutes at maximum speed in a microcentrifuge. Supernatants containing the cytoplasmic extracts were transferred to a fresh tube. Pelleted nuclear fraction was resuspended with 50μL of the nuclear extraction reagent, vortexed vigorously for 15 seconds, incubated on ice for 40 minutes and centrifuged at maximum speed for 10 minutes. Nuclear fraction supernatants were transferred to a fresh tube. All fractions were further analyzed by western blotting.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays:

IL-1β mini enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Peprotech, Cat. #900-K00, 2018) was used to detect the mature form of IL-1β secreted by IMG cells. Briefly, IMG cells grown in a poly-D-lysine-treated six-well tissue culture dish were incubated with normal growth media containing the indicated concentrations of amyloid-β42 peptide and/or FAC for the indicated time points in a 37°C and 5% CO2 incubator. For experiments testing caspase-1 activity in the release of mature IL-1β, 40μM YVAD-cmk was added to the wells for 5 minutes before the addition of 5mM ATP for 30 minutes. Conditioned media was collected, and cells were washed three times with ice-cold PBS and lysed at 4°C with RIPA lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors. IL-1β capture antibody was adhered to wells of a 96-well plate overnight at room temperature followed by several washes with the washing buffer provided in the kit. The wells were then blocked with 1 % bovine serum albumin in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature followed by multiple washes. For each condition, 100μL volumes of conditioned media were added to each well in triplicates and left for 2 hours at room temperature. The plate was washed, and 0.5μg/mL of the detection antibody was added to the wells and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Plates were then washed and incubated with avidin-HRP conjugate (1:2000 dilution) for 30 min at room temperature. Lastly, the plate was washed, and the liquid substrate 2,2′-azinobis [3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid]-diammonium salt was added to each well, and color development was monitored at 405nm using a BioTek Synergy 2 spectrophotometer (Winooski, VT).

Statistical Analysis:

The results shown are means ± SD with the number of biological replicates and experiments indicated in the figure legends. Data were collected from a minimum of 3 independent cell culture experiments. Statistical analyses were performed with Prism GraphPad version 8 for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) using the two-tailed Student’s t-test or ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test as appropriate. Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test for Normality of the data before statistical analyses. No sample calculation was performed. No test for outliers was conducted on the data. Significant difference was defined as P ≤ 0.05.

Results

Aβ induces expression of IL-1β by IMG cells:

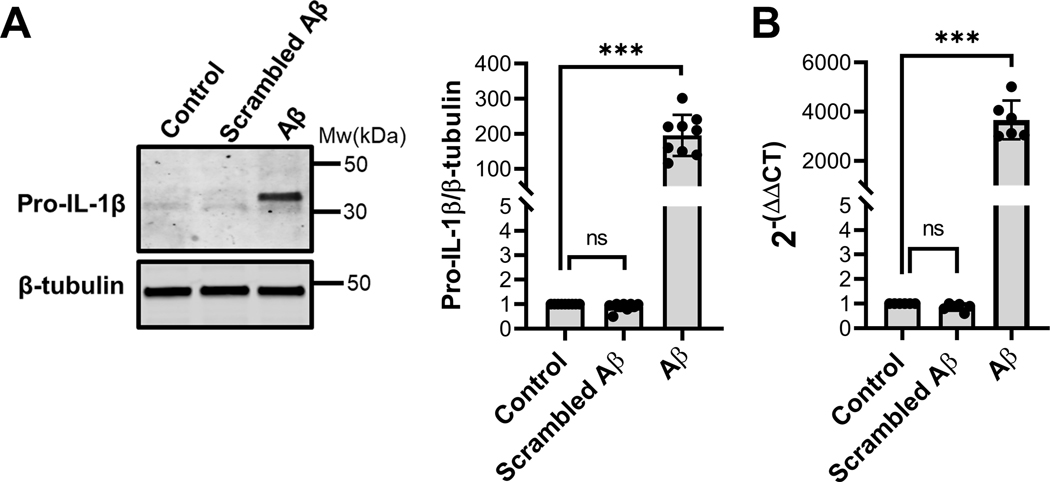

Previous studies have demonstrated that Alzheimer’s disease peptide Aβ induces pro-inflammatory responses in IMG cells (McCarthy et al. 2018). Studies carried out in other microglial cell lines have shown that Aβ stimulates the release of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β but only after an initial stimulation of the toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling with a priming factor such as LPS (Pinteaux et al. 2002, Parajuli et al. 2013, Burm et al. 2015). To examine the influence of Aβ on the synthesis of IL-1β by IMG cells, protein and transcript levels of IL-1β in IMG cells treated with 1μM Aβ for 16 hours were determined by immunoblot and RT-qPCR analyses (Fig. 1A and 1B). These results indicate that treatment of IMG cells with Aβ alone upregulates transcription and synthesis of the pro-IL-1β. Endotoxin testing of cell media confirmed the absence of LPS (less than the limit of detection, 0.01EU/ml), and scrambled Aβ was without effect on IMG cells (Fig 1A and 1B). Thus, cognate Aβ(1–42) by itself appears to be sufficient in inducing IMG cells to produce IL-1β.

Figure 1. Aβ induces IL-1β in IMG cells.

(A) Immunoblot analysis of pro-IL-1β protein levels in lysates prepared from cells treated with 1μM Aβ or scrambled Aβ for 16 hours. A representative immunoblot is shown with the fold change in pro-IL-1β protein level in Aβ-treated cells compared to control cells determined from data collected in 3 independent experiments, each with 3 biological replicates. β-tubulin served as a loading control. (B) Transcript levels of IL-1β in IMG cells treated with 1μM Aβ for 16 hours were analyzed by RT-qPCR. 36B4 served as control RT-qPCR analysis. Data are the means ± SD from 3 independent cell culture experiments each with 2 biological replicates. Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to determine the significance of the data. ***P≤0.001.

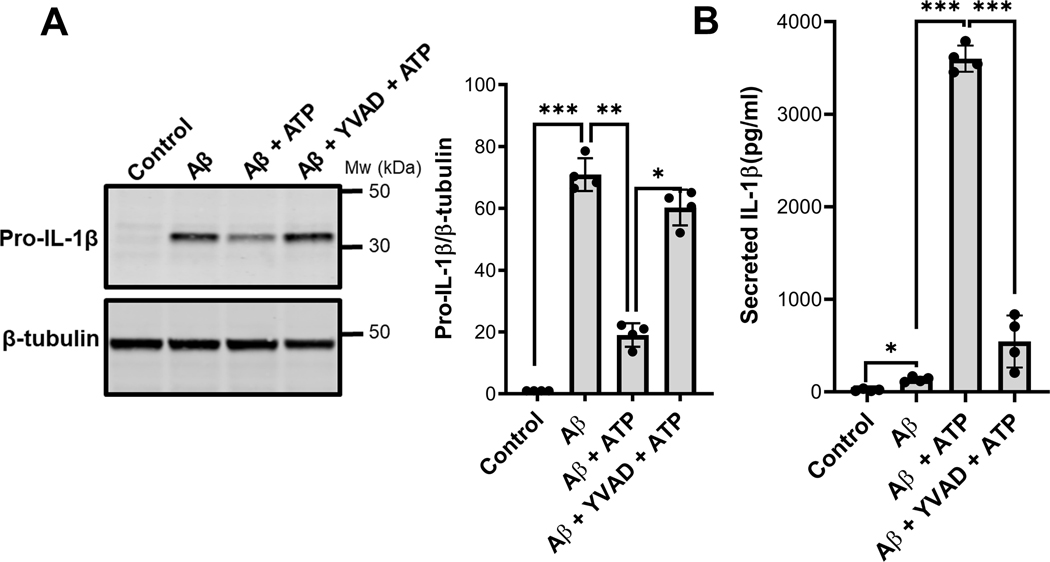

In order to be released in its mature reactive form, pro-IL-1β must be processed by proteolytic cleavage carried out upon activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and caspase-1 activity (Weber et al. 2010, Jo et al. 2016). Inflammasome activity can be induced by the canonical danger signal presented by extracellular ATP. To further examine processing and secretion of the cytokine induced by Aβ, IMG cells were first treated with 1μM Aβ for 16 hours then stimulated by a 30-minute incubation with 5mM ATP. To define the role of caspase-1, ATP was added with or without the caspase-1 inhibitor z-YVAD-cmk. Induction of pro-IL-1β protein synthesis was subsequently assessed by western blots of IMG cell lysates and the amount of IL-1β secreted into conditioned media was determined by ELISA which specifically detects the mature form. IMG cells treated with Aβ expressed pro-IL-1β protein (Fig. 2A) but the mature form of the cytokine was detected in culture media only when ATP was added (Fig. 2B). A corresponding decrease in cell-associated pro-IL-1β was observed in the presence of ATP (Fig. 2A). Treatment with the caspase-1 inhibitor blocked processing induced by ATP as reflected by the increased amount of cell-associated pro-IL-1β and the reduced amount of mature IL-1β secreted into the media by IMG cells. Together these data show that Aβ, by itself, induces expression of pro-IL-1β protein but that release of mature peptide still requires a second “hit” to trigger the inflammasome-mediated processing and secretion of IL-1β by IMG cells.

Figure 2. IMG cells secrete IL-1β in a caspase-1 dependent manner.

(A) Immunoblot analysis of protein lysates prepared from cells treated with 1μM Aβ for 16 hours, washed twice with normal media, and stimulated with 5mM ATP for 30 minutes with or without caspase-1 inhibitor z-YVAD-cmk. The fold change of cell-associated pro-IL-1β was quantified using β-tubulin as a loading control. (B) ELISA analysis determined the amount of mature IL-1β secreted into conditioned media after indicated treatments as described in methods section. Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to determine the significance of the data. *P≤0.05;**P≤0.01; ***P≤0.001. Data are the means ± SD from 4 independent cell culture experiments (one well per condition in each experiment); a representative immunoblot is shown.

Iron potentiates Aβ-mediated induction of IL-1β by IMG cells:

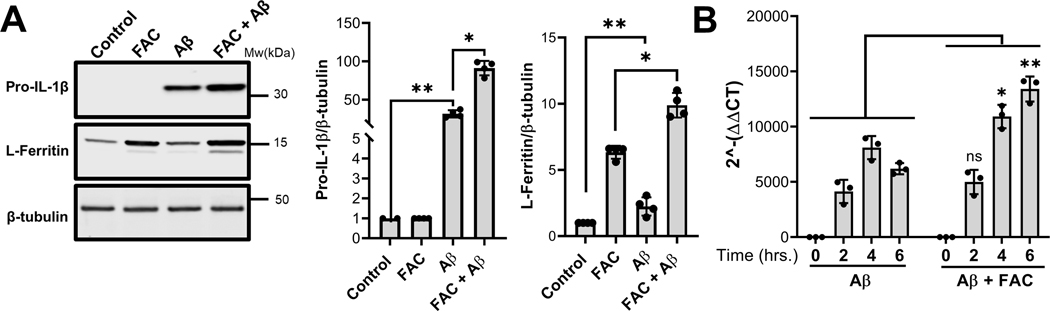

Accumulating evidence indicates that onset of AD is closely associated with brain iron levels and microglia-driven chronic neuroinflammation, both of which increase with age (Zhu et al. 2007, Praticò 2008, Bonda et al. 2010, Bush 2013, Zeineh et al. 2015). To determine how iron may influence the inflammatory signaling cues induced by Aβ to promote IL-1β expression, processing and secretion, IMG cells were treated with Aβ in the presence or absence of ferric ammonium citrate (FAC). Environmentally, the actual amount and form of iron associated with Aβ plaques is not known. Therefore, we first established the maximal physiological level of iron to use in our assay while avoiding secondary effects on IMG cells due to cellular toxicity. Systemic levels of diferric transferrin circulating in plasma are 25 μM, thus at saturation the amount of bound iron in plasma can be approximated at 50 μM. However, it should be noted that the amount of transferrin in brain interstitial fluid may be much lower, while non-transferrin bound iron levels in the brain are thought to be higher than plasma levels. In dose response experiments, we found that IMG cell viability was maintained in the presence of up to 50μM FAC (supplementary figure S1). Next, to confirm iron loading of IMG cells at this concentration of FAC, lysates were collected after incubation and immunoblotted to determine levels of the iron-sequestering protein ferritin (Fig. 3A). Incubation with 50μM FAC upregulated L-ferritin consistent with increased cellular iron content in IMG cells. Levels of this protein were further up-regulated with addition of Aβ due to induction of the inflammatory response as previously reported for these cells (McCarthy et al. 2018). Thus, IMG cells were viable and took up iron under our assay conditions. Finally, induction of pro-IL-1β in the presence of 50 μM FAC was analyzed by western blot. Compared to the 40-fold increase observed for cells treated with Aβ alone, treatment of IMG cells with FAC and Aβ resulted in an 80-fold increase in pro-IL-1β (Fig. 3A). qPCR analysis (Fig. 3B) showed that the combination of Aβ with iron enhanced IL-1β transcript levels; iron treatment alone induced only a minor increase (data not shown). To ensure the effect of FAC was exerted at the cellular level and wasn’t secondary to conformational changes in Aβ, dot blot experiments were carried out after incubation of Aβ with 50 μM FAC using conformation-specific antibodies (supplementary figure S2). Incubation with iron did not alter the forms of the peptide present in the preparation, which are predominantly oligomeric. Thus, we conclude that iron potentiates Aβ-mediated induction of IL-1β by acting directly on IMG cells.

Figure 3. Effect of iron on the Aβ-mediated induction of IL-1β in IMG cells.

(A) Immunoblot analysis of lysates prepared from IMG cells incubated with or without 1μM Aβ plus or minus 50μM FAC for 16 hours. The fold change of pro-IL-1β and L-ferritin protein levels were quantified using β-tubulin as a loading control. (B) Transcript levels of IL-1β in IMG cells treated with 1μM Aβ with or without 50μM FAC for indicated time points were analyzed by RT-qPCR. Two-tailed student’s t-test was used to determine the significance of the data. *P≤0.05; **P≤0.01; ns denotes no significant difference. Data are means ± SD from 3–4 independent cell culture experiments (n = 2 biological replicates in each experiment); a representative immunoblot is shown.

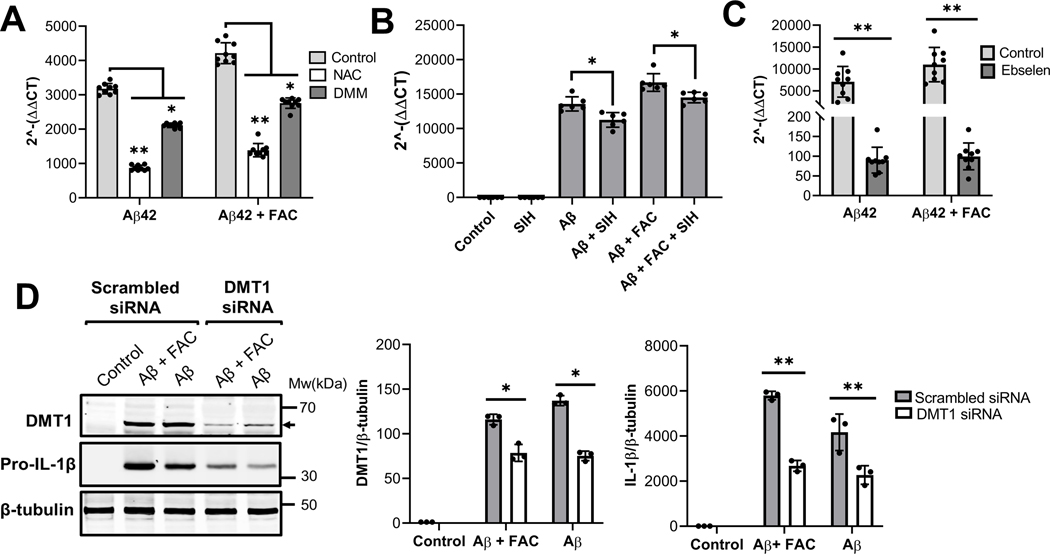

Iron is a known mediator of the Fenton reaction that generates ROS. We and others have demonstrated that inflammatory stimulants alter the expression of DMT1 to promote iron uptake in microglia (Urrutia et al. 2013, McCarthy et al. 2018) suggesting that intracellular iron accumulation via DMT1 and the subsequent generation of ROS may contribute to the IMG cell inflammatory response. To test this hypothesis, we first assessed IL-1β transcript levels in IMG cells incubated with Aβ and FAC in the presence or absence of N-acetylcysteine (NAC, a ROS scavenger) and dimethylmalonate (DMM, a complex II inhibitor that blocks mROS production). Both agents blunted IL-1β induction by Aβ or Aβ plus FAC, compared to vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 4A). To confirm the role of intracellular iron in the induction of IL-1β, IMG cells were co-incubated with the cell-permeable iron chelator, salicylaldehyde-isocotinoyl-hydrazone (SIH), which also antagonized the inflammatory effect of Aβ (Fig. 4B). To further examine whether induction of IL-1β by involves iron uptake by IMG cells, we incubated Aβ and FAC-treated IMG cells with ebselen, an inhibitor of the iron transporter DMT1 (Wetli et al. 2006). Induction of IL-1β was suppressed in the presence of this inhibitor (Fig 4C), suggesting that iron must actively be taken up for Aβ to exert inflammatory effects. Finally, we used RNAi mediated DMT1 knockdown to specifically probe the role of this transporter. DMT1 knockdown normalized the difference between Aβ and Aβ plus FAC to induce IL-1β. Combined, these results characterize iron as a potent enhancer of the pro-inflammatory effects of Aβ on IMG cells to promote IL-1β synthesis and highlight the role of iron uptake to potentiate Aβ-mediated induction of IL-1β by IMG cells.

Figure 4. Effects of intracellular ROS inhibition, iron chelation and DMT1 inhibition on Aβ-mediated induction of IL-1β.

(A) IMG cells were treated for 16h with 1μM Aβ42, with or without 50μM FAC, plus 10mM N-Acetylcysteine (NAC) or 10mM Dimethylmalonate (DMM). (B) Cells were treated for 16h with 1μM Aβ42, with or without 50μM FAC, in the presence of 10μM salicylaldehyde-isocotinoyl-hydrazone (SIH), a cell permeant iron chelator. (C) Cells treated with 1μM Aβ42, with or without 50μM FAC, were co-incubated with the iron uptake inhibitor 50μM Ebselen for 16h. (D) DMT1-knockdown and control cells were treated with 1μM Aβ42, with or without 50μM FAC, for 16h followed by western blot analyses to determine DMT1 and pro-IL-1β protein levels. For DMT1 analysis, protein samples were heated to 72 oC. Data in panels A-C are from 3 independent cell culture experiments with 2–3 biological replicates in each; Panel D shows data from 3 independent cell culture experiments with one well per each condition. Shown are the means ± SD. Two-tailed student’s t-test was used to determine the significance of the data. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01.

Iron potentiates Aβ-mediated activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway:

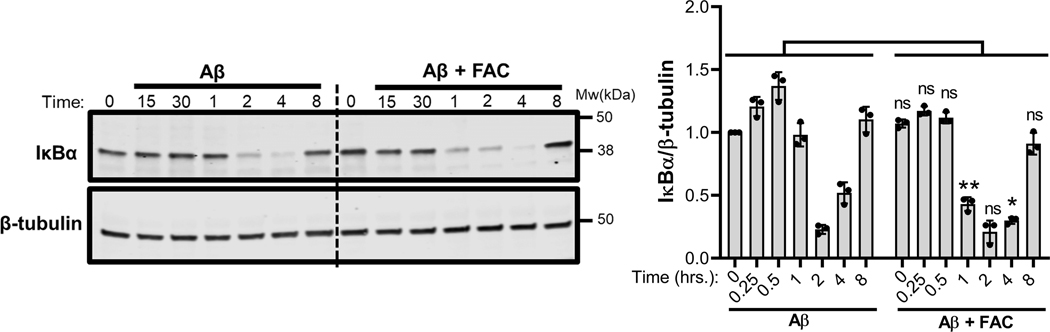

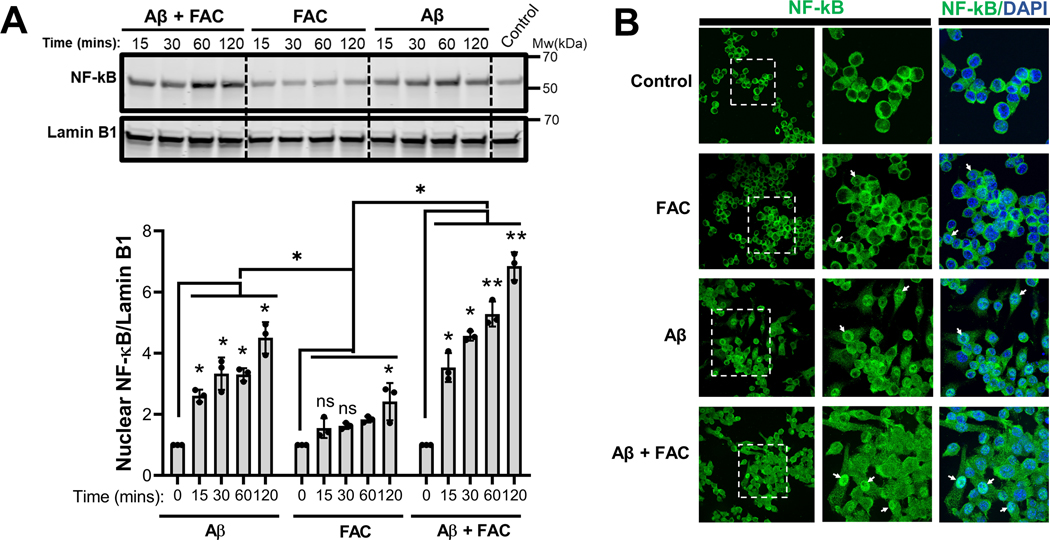

Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling has been associated with Aβ-induced proinflammatory activation of microglia (Liu et al. 2012, McDonald et al. 2016, Rubio-Araiz et al. 2018). TLR signaling is initiated when the IκB kinase (IKK) complex is activated to mediate the phosphorylation and subsequent proteasomal degradation of the NF-κB inhibitor, IκB (D’Ignazio et al. 2016). This action promotes the nuclear translocation of NF-κB for transcriptional upregulation of IL-1β and other targets of the transcription factor. It is known that ROS can activate NF-κB signaling (Takada et al. 2003, Forrester et al. 2018). To test whether iron influences NF-κB signaling to potentiate IL-1β secretion by IMG microglia, cells were incubated with Aβ in the presence or absence of 50μM FAC and degradation of IκBα was assessed over an 8 h time period. Compared to Aβ-treated controls, degradation of IκB in IMG cells incubated with the combination of iron and Aβ occurred more rapidly, with loss of the NF-κB inhibitor observed as soon as 1 h post-stimulation (Fig 5). Nuclear fractionation of IMG cells treated with Aβ alone, FAC alone or with a combination of Aβ and FAC showed increased nuclear translocation of NF-κB in cells treated with both Aβ and FAC (Fig. 6A). Near complete IκBα degradation at 2 hours coincides with the observed peak of NF-κB accumulation. Indirect immunofluorescence microscopy further demonstrates increased nuclear staining of NF-κB in IMG cells stimulated by Aβ in the presence of FAC (Fig. 6B)

Figure 5. Effect of iron on Aβ activation of TLR signaling.

Immunoblot analysis of lysates prepared from IMG cells that were incubated with 1μM Aβ plus or minus 50μM FAC for the indicated time points. IkBα protein levels in all the conditions were first normalized to the loading control β-tubulin, then fold-change was determined in each condition relative to untreated controls at time 0. Two-tailed student’s t-test was used to determine the significance of the data. **P≤0.005; ns denotes no significant difference. Shown are the means ± SD are from 3 independent cell culture experiments with 1 well in each experiment); a representative immunoblot is shown. Two-tailed student’s t-test was used to determine the significance of the data. *P ≤ 0.05.

Figure 6. Iron potentiates nuclear translocation of NF-κB induced by Aβ.

(A) Immunoblot analysis of nuclear fractions prepared from IMG cells that were incubated with 1μM Aβ plus or minus 50μM FAC for the indicated time points. Nuclear NF-κB(p65) protein levels in all the conditions were first normalized to the nuclear marker lamin B1, and the fold change was determined in each condition relative to untreated controls at time 0. A representative immunoblot is shown and data shown are means ± SD from 3 independent cell culture experiments with 1 well in each experiment). Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to determine the significance of the data. *P≤0.05; **P≤0.01; ns denotes no significant difference. (B) Immunofluorescence analysis of IMG cells incubated with or without 1μM Aβ in the presence or absence of 50μM FAC for 8 hours. Anti-NF-κB primary antibody was used to detect NF-κB protein (stained green). DAPI was used to stain nuclei. White arrow heads point to the nuclear NF-κB.

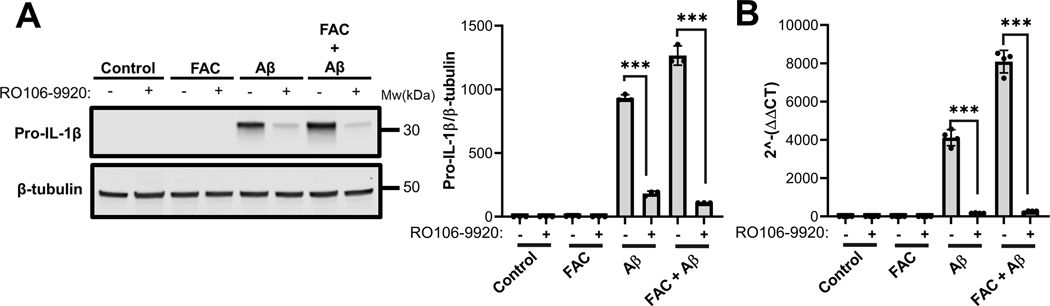

Upregulation of IL-1β in IMG cells is blocked by inhibition of IKK:

To determine whether NF-κB activation was prerequisite for FAC-induced effects on IL-1β induction, IMG cells were treated with the specific inhibitor of IKK, RO106-9920 during stimulation with Aβ in the presence and absence of iron. Both western blot (Fig. 7A) and RT-qPCR (Fig. 7B) analyses indicated that the IKK inhibitor blocked the induction of IL-1β expression by Aβ. Because FAC-induced increases in IL-1β induction were also blocked, these observations indicate that iron enhances the pro-inflammatory effects of Aβ secondary to the activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway in microglia. This idea is consistent with increased IκBα degradation observed in the presence of FAC in Aβ-activated IMG cells (Fig. 5).

Figure 7. Aβ-mediated induction of IL-1β in IMG cells requires NF-κB signaling.

(A) Immunoblot analysis of pro-IL-1β protein levels in lysates prepared from IMG cells treated with 3μM of the NF-κB inhibitor RO106–9920 in the presence or absence of FAC plus or minus 1μM Aβ for 6 hours. A representative immunoblot is shown. Data are means ± SD of results collected from 3 independent cell culture experiments with 1 well per each condition. (B) RT-qPCR analysis of IL-1β transcript levels in IMG cells treated as in panel A. Two-tailed student’s t-test was used to determine the significance of the data. ***P≤0.001. Data are means ± SD from 4 independent cell culture experiments with 1 well per condition in each experiment

Discussion

In this study, we set out to investigate the effect of iron on Aβ-induced microglial expression, processing and secretion of IL-1β, a prominent pro-inflammatory cytokine involved in the induction of pathogenic neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in AD. Earlier studies from other groups showed that the accumulation of iron in the brain coincides with that activation of microglia-induced neuroinflammation, and that both processes are involved in the pathogenesis of AD (Gallagher et al. 2012, Meadowcroft et al. 2015, Zeineh et al. 2015). Here we establish a mechanistic link by examining the influence of iron on transcript and protein levels of IL-1β in microglial IMG cells. Our results demonstrate that the presence of iron provokes a stronger inflammatory response induced by Aβ. These findings further suggest that such iron-mediated microglial responses contribute to the chronic inflammation observed in AD.

The role of IL-1β in the pathogenesis of AD has been a subject of intense study in recent years and most reports indicate that individuals with AD, and as well as AD mouse models, accumulate high levels of this cytokine in cerebrospinal fluid (Griffin 2000, Griffin et al. 2006, Simard et al. 2006, White et al. 2017). When released by microglia and other immune cells, IL-1β provokes expression of adhesion molecules and infiltration of immune cells (Rothwell JN and GN 2000, Toda et al. 2002, Simard et al. 2006, Dinarello 2009, White et al. 2017). High levels of IL-1β in the brain are reported to affect synaptic plasticity, thus causing impairment of learning and memory formation (Moore et al. 2009).

It has been suggested that Aβ, the main component of senile plaques, activates inflammasome-mediated processing and secretion of the matured form of IL-1β but is incapable of initiating IL-1β gene expression in microglia (Parajuli et al. 2013, Burm et al. 2015). Our results argue against this idea as treatment of IMG cells with peptide alone induced IL-1β expression. Induction of IL-1β mRNA and its precursor protein, pro-IL-1β, is known to be controlled by NF-κB transcription factor downstream of the TLR signaling pathway (Liu et al. 2012, McDonald et al. 2016, Rubio-Araiz et al. 2018). We determined that Aβ induces mRNA and protein levels by activation of NF-κB signaling. This conclusion is supported by the observed induction of IκBα degradation and nuclear translocation of NF-κB when IMG cells are treated with Aβ. Moreover, IL-1β induction by Aβ is blocked by the IKK inhibitor RO106-9920.

Some reports have identified TLR2 as the member of the TLR family that mediates macrophage inflammatory response to Aβ (Liu et al. 2012). TLR2 has an ability to form heterodimers with TLR1 or TLR6 to achieve ligand specificity (Farhat et al. 2008). Dimerization with TLR1 enhances TLR2-mediated inflammatory response to Aβ in RAW264.7 macrophage cell line, while binding to TLR6 suppresses it (Liu et al. 2012). Aβ may be interacting with TLR2-TLR1 heterodimer to induce IL-1β in IMG cells, which express both receptor family members (ICN and CHL, personal observations). We do know that a second trigger is necessary to activate NLRP3 inflammasome and caspase-1 processing for release of IL-1β (Martinon et al. 2006, Weber et al. 2010, D’Ignazio et al. 2016). In our studies, we observed secretion of the matured form of IL-β into conditioned media only when Aβ-treated IMG cells were stimulated by exogenous addition of ATP. Thus, without any additional stimulation of TLR signaling, Aβ sufficiently induced IMG cells to biosynthesize IL-1β but the subsequent inflammasome-mediated processing and release of IL-1β required an additional “danger” activating signal.

Earlier studies by our laboratory and others have demonstrated that Aβ also enhances microglial uptake and sequestration of extracellular iron (Terrill-Usery et al. 2014, McCarthy et al. 2018, McIntosh et al. 2019). Our group has shown that iron transport pathways in IMG cells are differentially activated in response to pro- and anti-inflammatory stimuli at both the transcript and protein levels. Pro-inflammatory mediators including Aβ up-regulate the iron importing membrane protein DMT1 along with the iron sequestering factor ferritin. These factors serve to increase the uptake of non-transferrin bound iron to expand iron pools in IMG cells (McCarthy et al. 2018). The increase in intracellular sequestration of iron correlates with increased level of intracellular ROS, induction of IL-1β and inflammation (Zhu et al. 2007, Praticò 2008, Bonda et al. 2010, Bush 2013, Urrutia et al. 2013, Zeineh et al. 2015, McCarthy et al. 2018). Further studies show that secreted IL-1β and other pro-inflammatory cytokines can influence microglial iron transport and metabolism (Urrutia et al. 2013, Wang et al. 2013, Thomsen et al. 2015, Holland et al. 2018). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying the role of iron during microglia-mediated inflammatory responses is unclear. Therefore, we examined whether microglial DMT1-mediated iron import and intracellular ROS influenced Aβ-mediated induction of IL-1β. Our results demonstrate greater levels of IL-1β mRNA and pro-IL-1β protein in the lysates of IMG cells treated with Aβ in the presence of iron. Inhibition of ROS or DMT1 activity protected IMG cells against Aβ-induced inflammation. Notably, DMT1 antagonism and protein depletion abolished the enhancement of Aβ-elicited IL-1β induction by FAC, supporting the notion that DMT1-mediated iron loading and cellular ROS contribute to the inflammatory effects of Aβ in microglia. Mechanistically, iron appears to enhance the NF-κB signaling pathway that is activated by Aβ. Specifically, IκBα degradation occurred more rapidly in iron-treated cells induced by Aβ. Nuclear fractionation and immunofluorescence microscopy data confirmed the expected increase in nuclear translocation of NF-κB in cells treated with both Aβ and iron. Importantly, the IKK inhibitor RO106-9920 blocked this activity supporting the idea that the effects of iron are secondary to NF-κB activation.

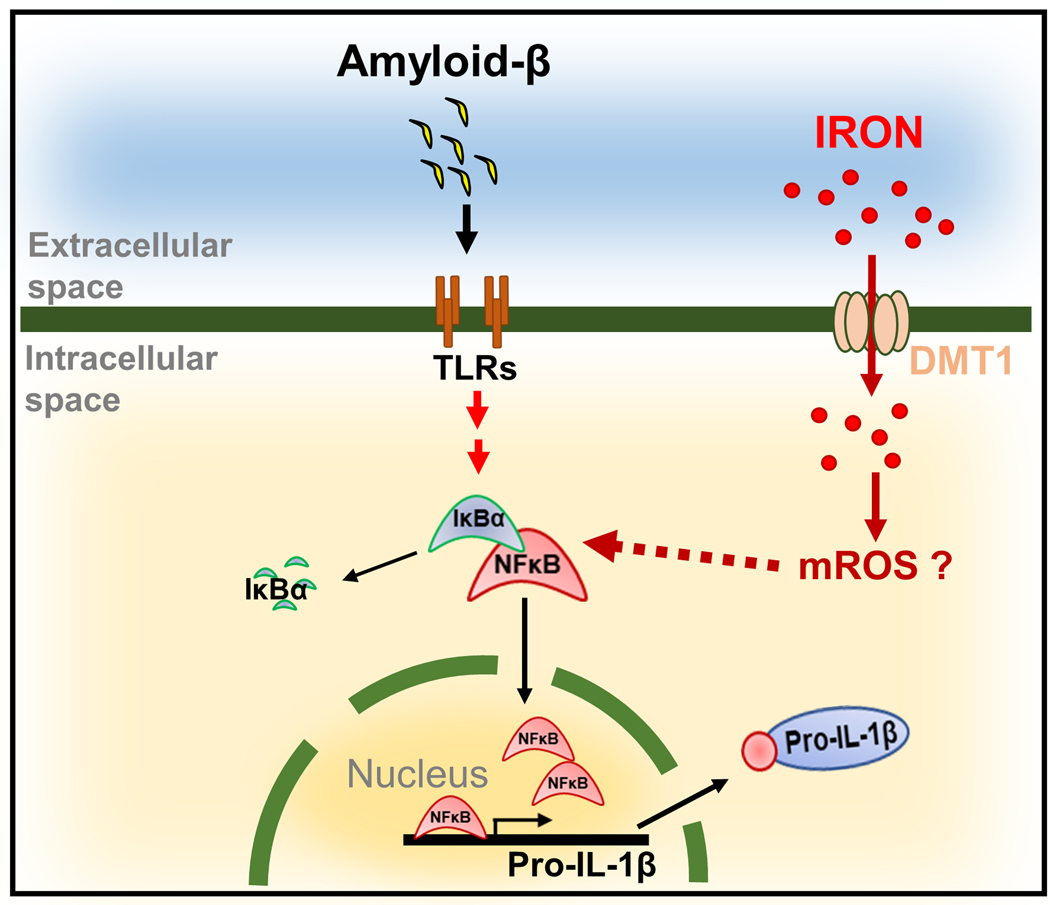

Our data are summarized in Figure 8 which presents a model wherein Aβ stimulates microglial cell expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β by activating NF-κB signaling. We show that iron enhances Aβ activation of NF-κB signaling to further promote synthesis of IL-1β. These effects are suppressed by depletion of the iron transporter DMT-1. ROS scavengers also reduce induction of IL-1β, suggesting that the potentiating effects of iron are at least in part due to cellular ROS.

Figure 8. Iron potentiates the pro-inflammatory signaling cues induced by Aβ to promote microglial IL-1β expression, processing and secretion.

Data are summarized by a model wherein Aβ stimulates microglial cell expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β by activating NF-κB signaling. We show that iron enhances Aβ activation of NF-κB signaling to further promote synthesis of IL-1β. These effects are suppressed by depletion of the iron transporter DMT-1. ROS scavengers also reduce induction of IL-1β, suggesting that the potentiating effects of iron are at least in part due to cellular ROS.

In addition to iron, dysregulation of other essential metals including copper, zinc, and manganese, has also been implicated in microglial activation and aberrant secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines. For instance, the exposure of copper to microglial cells has been shown to impair their ability to clear amyloid-beta and further enhance the Aβ-mediated activation and secretion of TNFα and IL-1β by these cells in an NF-κB-dependent manner (Hu et al. 2014, Yu et al. 2015, Kitazawa et al. 2016). Studies carried out in the AD mouse model Tg2576, which expresses human amyloid precursor protein (APP) carrying a Swedish mutation (APPsw), show that synaptic zinc contributes to Aβ deposition (Suh et al. 2000, Lee et al. 2002). Chronic manganese exposure has been reported to induce TLR signaling and oxidative stress that cumulatively cause inflammation (Ling et al. 2018). All of these studies highlight the impact of metals on AD and neurodegeneration.

Previous studies have demonstrated that iron-loading suppressed LPS-mediated induction of IL-1β in macrophages (O’Brien-Ladner et al. 2000). Conversely, disruption of iron homeostasis by brain hemorrhage results in an increased level of TNF-α and IL-1β (Meng et al. 2017, Jiang et al. 2018). Subsequent in vivo and in vitro studies carried out in AD models confirmed that iron overload results in elevated Aβ production, neuronal toxicity and cognitive impairments (Becerril-Ortega et al. 2014, Peters et al. 2018). Collectively, these observations suggest that iron modulates inflammatory response in a tissue/cell type-specific manner. Our findings support a model summarized in Fig. 8 which shows a hypothetical mechanism through which iron potentiates pro-inflammatory signaling cues induced by Aβ to promote microglial IL-1β expression, processing and secretion. Our results support the hypothesis that Aβ stimulates microglial cell expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β by activating NF-κB signaling. We show that iron enhances Aβ activation of NF-κB signaling to further promote synthesis of IL-1β. These effects are suppressed by depletion of the iron transporter DMT-1. ROS scavengers also reduce induction of IL-1β, suggesting that the potentiating effects of iron are at least in part to due to cellular ROS production. As a consequence of these interactions, reducing brain iron, either by dietary or pharmacological means, may provide additional therapeutic benefits for alleviating AD. Indeed, a number of clinical studies testing the effectiveness iron chelation therapies in neurodegenerative diseases have yielded encouraging data. An early study using desferoxamine, which is administered intramuscularly, showed promising results with low dose application slowing AD-associated dementia (McLachlan et al. 1991). Most recently, the ability of an iron chelator that penetrates the blood-brain-barrier, deferiprone, is under phase 2 investigation in a randomized placebo-controlled trial of patients showing signs of AD (NCT03234686). These future prospects will be bolstered by a better understanding how iron might influence progression of this devastating disease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Disease under the award R01 DK064750 and S1-DK064750. ICN was supported, in part, by funding by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences under the award T32 ES016645.

Abbreviations:

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Aβ

amyloid beta

- CNS

central nervous system

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- IkBα

NF-κB inhibitor alpha

- FAC

ferric ammonium citrate

- IKK

inhibitor of kappa B kinase

- IL-1β

interleukin 1-beta

- IMG

immortalized microglia

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- NLRP3

NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain-containing 3

- PBS

phosphate buffer saline

- RIPA

radioimmunoprecipitation assay

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RT-qPCR

reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- DMT1

divalent metal transporter 1

- MTT

3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- HCL

hydrochloric acid

- NAC

N-Acetylcysteine

- DMM

dimethylmalonate

- SIH

salicylaldehyde-isocotinoyl-hydrazone

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- mROS

mitochondrial reactive oxygen species

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors do not have any conflict of interest.

References

- Bartzokis G, S. D, Cummings J, et al. (2000). In vivo evaluation of brain iron in Alzheimer disease using magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Gen Psychiatry 57, 47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu A, Krady JK and Levison SW (2004). Interleukin-1: a master regulator of neuroinflammation. J Neurosci Res 78, 151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard JL and Connor JR (2003). Iron status and neural functioning. Annu Rev Nutr 23, 41–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerril-Ortega J, Bordji K, Freret T, Rush T and Buisson A. (2014). Iron overload accelerates neuronal amyloid-beta production and cognitive impairment in transgenic mice model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 35, 2288–2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belaidi AA and Bush AI (2016). Iron neurochemistry in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease: targets for therapeutics. Journal of Neurochemistry 139, 179–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonda DJ, Wang X, Perry G, Nunomura A, Tabaton M, Zhu X and Smith MA (2010). Oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease: A possibility for prevention. Neuropharmacology 59, 290–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burm SM, Zuiderwijk-Sick EA, t Jong AE, van der Putten C, Veth J, Kondova I and Bajramovic JJ (2015). Inflammasome-induced IL-1beta secretion in microglia is characterized by delayed kinetics and is only partially dependent on inflammatory caspases. J Neurosci 35, 678–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush AI (2013). The metal theory of Alzheimer’s disease. Advances in Alzheimer’s Disease 33, 277–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush AI (2013). The metal theory of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 33 Suppl 1, S277–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor JR, Menzies SL, St. Martin SM., and Mufson EJ (1992). A histochemical study of iron transferrin and ferritin in alzheimers disease brains. Journal of Neuroscience 31, 75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Ignazio L, Bandarra D and Rocha S. (2016). NF-kappaB and HIF crosstalk in immune responses. FEBS J 283, 413–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA (2009). Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin-1 family. Annu Rev Immunol 27, 519–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhat K, Riekenberg S, Heine H, Debarry J, Lang R, Mages J, Buwitt-Beckmann U, Roschmann K, Jung G, Wiesmuller KH and Ulmer AJ (2008). Heterodimerization of TLR2 with TLR1 or TLR6 expands the ligand spectrum but does not lead to differential signaling. J Leukoc Biol 83, 692–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forrester SJ, Kikuchi DS, Hernandes MS, Xu Q and Griendling KK (2018). Reactive Oxygen Species in Metabolic and Inflammatory Signaling. Circ Res 122, 877–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher JJ, Finnegan ME, Grehan B, Dobson J, Collingwood JF and Lynch MA (2012). Modest amyloid deposition is associated with iron dysregulation, microglial activation, and oxidative stress. J Alzheimers Dis 28, 147–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold M and El Khoury J. (2015). beta-amyloid, microglia, and the inflammasome in Alzheimer’s disease. Semin Immunopathol 37, 607–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin R. E. M. a. S. T (2000). Interleukin-1 and the immunogenetics of Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology 59, 471–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin WS, Liu L, Li Y, Mrak RE and Barger SW (2006). Interleukin-1 mediates Alzheimer and Lewy body pathologies. J Neuroinflammation 3, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heneka MT, Kummer MP, Stutz A, Delekate A, Schwartz S, Vieira-Saecker A, Griep A, Axt D, Remus A, Tzeng T-C, Gelpi E, Halle A, Korte M, Latz E and Golenbock DT (2013). NLRP3 is activated in Alzheimer’s disease and contributes to pathology in APP/PS1 mice. Nature 493, 674–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentze MW, Muckenthaler MU, Galy B and Camaschella C. (2010). Two to tango: regulation of Mammalian iron metabolism. Cell 142, 24–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland R, McIntosh AL, Finucane OM, Mela V, Rubio-Araiz A, Timmons G, McCarthy SA, Gun’ko YK and Lynch MA (2018). Inflammatory microglia are glycolytic and iron retentive and typify the microglia in APP/PS1 mice. Brain Behav Immun 68, 183–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Yu F, Gong P, Qiu Y, Zhou W, Cui Y, Li J and Chen H. (2014). Subneurotoxic copper(II)-induced NF-kappaB-dependent microglial activation is associated with mitochondrial ROS. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 276, 95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C, Zou X, Zhu R, Shi Y, Wu Z, Zhao F and Chen L. (2018). The correlation between accumulation of amyloid beta with enhanced neuroinflammation and cognitive impairment after intraventricular hemorrhage. J Neurosurg, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo EK, Kim JK, Shin DM and Sasakawa C. (2016). Molecular mechanisms regulating NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Cell Mol Immunol 13, 148–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik DK, Thounaojam MC, Kumawat KL, Gupta M and Basu A. (2013). Interleukin-1beta orchestrates underlying inflammatory responses in microglia via Kruppel-like factor 4. J Neurochem 127, 233–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J and Wessling-Resnick M. (2014). Iron and mechanisms of emotional behavior. The Journal of nutritional biochemistry 25, 1101–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitazawa M, Hsu HW and Medeiros R. (2016). Copper Exposure Perturbs Brain Inflammatory Responses and Impairs Clearance of Amyloid-Beta. Toxicol Sci 152, 194–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane DJR, Ayton S and Bush AI (2018). Iron and Alzheimer’s Disease: An Update on Emerging Mechanisms. J Alzheimers Dis 64, S379–S395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CY and Landreth GE (2010). The role of microglia in amyloid clearance from the AD brain. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 117, 949–960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JY, Cole TB, Palmiter RD, Suh SW and Koh JY (2002). Contribution by synaptic zinc to the gender-disparate plaque formation in human Swedish mutant APP transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 7705–7710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lill R, Hoffmann B, Molik S, Pierik AJ, Rietzschel N, Stehling O, Uzarska MA, Webert H, Wilbrecht C and Mühlenhoff U. (2012). The role of mitochondria in cellular iron–sulfur protein biogenesis and iron metabolism. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 1823, 1491–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling J, Yang S, Huang Y, Wei D and Cheng W. (2018). Identifying key genes, pathways and screening therapeutic agents for manganese-induced Alzheimer disease using bioinformatics analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 97, e10775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Liu Y, Hao W, Wolf L, Kiliaan AJ, Penke B, Rube CE, Walter J, Heneka MT, Hartmann T, Menger MD and Fassbender K. (2012). TLR2 is a primary receptor for Alzheimer’s amyloid beta peptide to trigger neuroinflammatory activation. J Immunol 188, 1098–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeffler DA, C. JR, Juneau L, Snyder BS, Kanaley L, DeMaggio AJ, Nguyen H, Brickman CM, and LeWitt PA (1995). Transferrin and iron in normal, Alzheimer’s disease and parkinson’s disease brain regions. Journal of Neurochemistry 65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinon F, Petrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A and Tschopp J. (2006). Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature 440, 237–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy RC, Lu DY, Alkhateeb A, Gardeck AM, Lee CH and Wessling-Resnick M. (2016). Characterization of a novel adult murine immortalized microglial cell line and its activation by amyloid-beta. J Neuroinflammation 13, 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy RC, Sosa JC, Gardeck AM, Baez AS, Lee CH and Wessling-Resnick M. (2018). Inflammation-induced iron transport and metabolism by brain microglia. J Biol Chem 293, 7853–7863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald CL, Hennessy E, Rubio-Araiz A, Keogh B, McCormack W, McGuirk P, Reilly M and Lynch MA (2016). Inhibiting TLR2 activation attenuates amyloid accumulation and glial activation in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Behav Immun 58, 191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh A, Mela V, Harty C, Minogue AM, Costello DA, Kerskens C and Lynch MA (2019). Iron accumulation in microglia triggers a cascade of events that leads to altered metabolism and compromised function in APP/PS1 mice. Brain Pathol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan DRC, Kruck TPA, Kalow W, Andrews DF, Dalton AJ, Bell MY and Smith WL (1991). Intramuscular desferrioxamine in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. The Lancet 337, 1304–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadowcroft MD, Connor JR and Yang QX (2015). Cortical iron regulation and inflammatory response in Alzheimer’s disease and APPSWE/PS1DeltaE9 mice: a histological perspective. Front Neurosci 9, 255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng FX, Hou JM and Sun TS (2017). In vivo evaluation of microglia activation by intracranial iron overload in central pain after spinal cord injury. J Orthop Surg Res 12, 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore AH, Wu M, Shaftel SS, Graham KA and O’Banion MK (2009). Sustained expression of interleukin-1beta in mouse hippocampus impairs spatial memory. Neuroscience 164, 1484–1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhoberac BB and Vidal R. (2013). Abnormal iron homeostasis and neurodegeneration. Front Aging Neurosci 5, 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nnah IC and Wessling-Resnick M. (2018). Brain Iron Homeostasis: A Focus on Microglial Iron. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien-Ladner AR, Nelson SR, Murphy WJ, Blumer BM and Wesselius LJ (2000). Iron Is a Regulatory Component of Human IL-1b Production. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 23, 112–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan XD, Zhu YG, Lin N, Zhang J, Ye QY, Huang HP and Chen XC (2011). Microglial phagocytosis induced by fibrillar beta-amyloid is attenuated by oligomeric beta-amyloid: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener 6, 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parajuli B, Sonobe Y, Horiuchi H, Takeuchi H, Mizuno T and Suzumura A (2013). Oligomeric amyloid beta induces IL-1beta processing via production of ROS: implication in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Death Dis 4, e975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J, Min JS, Kim B, Chae UB, Yun JW, Choi MS, Kong IK, Chang KT and Lee DS (2015). Mitochondrial ROS govern the LPS-induced pro-inflammatory response in microglia cells by regulating MAPK and NF-kappaB pathways. Neurosci Lett 584, 191–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters DG, Pollack AN, Cheng KC, Sun D, Saido T, Haaf MP, Yang QX, Connor JR and Meadowcroft MD (2018). Dietary lipophilic iron alters amyloidogenesis and microglial morphology in Alzheimer’s disease knock-in APP mice. Metallomics : integrated biometal science 10, 426–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piñero DJ and Connor JR (2000). Iron in the Brain: An Important Contributor in Normal and Diseased States. The Neuroscientist 6, 435–453. [Google Scholar]

- Pinteaux E, Parker LC, Rothwell NJ and Luheshi GN (2002). Expression of interleukin-1 receptors and their role in interleukin-1 actions in murine microglial cells. Journal of Neurochemistry 83, 754–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praticò D. (2008). Oxidative stress hypothesis in Alzheimer’s disease: a reappraisal. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 29, 609–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell JN and L. GN (2000). Interleukin 1 in the brain: biology, pathology and therapeutic target Trends in Neuroscience 23, 618–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Araiz A, Finucane OM, Keogh S and Lynch MA (2018). Anti-TLR2 antibody triggers oxidative phosphorylation in microglia and increases phagocytosis of beta-amyloid. J Neuroinflammation 15, 247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard AR, Soulet D, Gowing G, Julien JP and Rivest S. (2006). Bone marrow-derived microglia play a critical role in restricting senile plaque formation in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 49, 489–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh SW, Jensen KB, Jensen MS, Silva DS, Kesslak PJ, Dancher G and Frederickson CJ (2000). Histochemically reactive zinc in amyloid plaques, angiopathy, and degenerating neurons of Alzheimer’s diseased brains. Brain Research 852, 274–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada Y, Mukhopadhyay A, Kundu GC, Mahabeleshwar GH, Singh S and Aggarwal BB (2003). Hydrogen peroxide activates NF-kappa B through tyrosine phosphorylation of I kappa B alpha and serine phosphorylation of p65: evidence for the involvement of I kappa B alpha kinase and Syk protein-tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem 278, 24233–24241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrill-Usery SE, Mohan MJ and Nichols MR (2014). Amyloid-beta(1–42) protofibrils stimulate a quantum of secreted IL-1beta despite significant intracellular IL-1beta accumulation in microglia. Biochim Biophys Acta 1842, 2276–2285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen MS, Andersen MV, Christoffersen PR, Jensen MD, Lichota J and Moos T. (2015). Neurodegeneration with inflammation is accompanied by accumulation of iron and ferritin in microglia and neurons. Neurobiol Dis 81, 108–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda Y, Tsukada J, Misago M, Kominato Y, Auron PE and Tanaka Y. (2002). Autocrine induction of the human pro-IL-1beta gene promoter by IL-1beta in monocytes. J Immunol 168, 1984–1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todorich B, Pasquini JM, Garcia CI, Paez PM and Connor JR (2009). Oligodendrocytes and myelination: the role of iron. Glia 57, 467–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschopp J and Schroder K. (2010). NLRP3 inflammasome activation: The convergence of multiple signalling pathways on ROS production? Nat Rev Immunol 10, 210–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udan ML, Ajit D, Crouse NR and Nichols MR (2008). Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 mediate Abeta(1–42) activation of the innate immune response in a human monocytic cell line. J Neurochem 104, 524–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urrutia P, Aguirre P, Esparza A, Tapia V, Mena NP, Arredondo M, Gonzalez-Billault C and Nunez MT (2013). Inflammation alters the expression of DMT1, FPN1 and hepcidin, and it causes iron accumulation in central nervous system cells. J Neurochem 126, 541–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Song N, Jiang H, Wang J and Xie J. (2013). Pro-inflammatory cytokines modulate iron regulatory protein 1 expression and iron transportation through reactive oxygen/nitrogen species production in ventral mesencephalic neurons. Biochim Biophys Acta 1832, 618–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Cella M, Mallinson K, Ulrich Jason D., Young Katherine L., Robinette Michelle L., Gilfillan S, Krishnan Gokul M., Sudhakar S, Zinselmeyer Bernd H., Holtzman David M., Cirrito John R. and Colonna M. (2015). TREM2 Lipid Sensing Sustains the Microglial Response in an Alzheimer’s Disease Model. Cell 160, 1061–1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward RJ, Zucca FA, Duyn JH, Crichton RR and Zecca L. (2014). The role of iron in brain ageing and neurodegenerative disorders. The Lancet Neurology 13, 1045–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber A, Wasillew P and Kracht M. (2010). Interleukin-1beta processing pathway. Immunology 3, 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessling-Resnick M. (2010). Iron homeostasis and the inflammatory response. Annu Rev Nutr 30, 105–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetli HA, Buckett PD and Wessling-Resnick M. (2006). Small-molecule screening identifies the selanazal drug ebselen as a potent inhibitor of DMT1-mediated iron uptake. Chem Biol 13, 965–972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White CS, Lawrence CB, Brough D and Rivers-Auty J. (2017). Inflammasomes as therapeutic targets for Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Pathol 27, 223–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Wang Y, Song N, Wang J, Jiang H and Xie J. (2018). New Progress on the Role of Glia in Iron Metabolism and Iron-Induced Degeneration of Dopamine Neurons in Parkinson’s Disease. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience 10, 455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang WS and Stockwell BR (2016). Ferroptosis: Death by Lipid Peroxidation. Trends in Cell Biology 26, 165–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu F, Gong P, Hu Z, Qiu Y, Cui Y, Gao X, Chen H and Li J. (2015). Cu(II) enhances the effect of Alzheimer’s amyloid-beta peptide on microglial activation. J Neuroinflammation 12, 122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Guo Y, Sun M, Li B, Zhang Y and Li C. (2009). Iron is a potential key mediator of glutamate excitotoxicity in spinal cord motor neurons. Brain Research 1257, 102–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zecca L, Youdim MB, Riederer P, Connor JR and Crichton RR (2004). Iron, brain ageing and neurodegenerative disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci 5, 863–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeineh MM, Chen Y, Kitzler HH, Hammond R, Vogel H and Rutt BK (2015). Activated iron-containing microglia in the human hippocampus identified by magnetic resonance imaging in Alzheimer disease. Neurobiology of Aging 36, 2483–2500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Su B, Wang X, Smith MA and Perry G. (2007). Causes of oxidative stress in Alzheimer disease. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 64, 2202–2210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.