Highlights

-

•

A chronic expanding hematoma of the adrenal gland is extremely rare.

-

•

Chronic expanding hematomas mimic sarcomatous lesions.

-

•

Gallium scintigraphy may help the differential diagnosis between chronic expanding hematomas and sarcomatous lesions.

-

•

Complete resection of chronic expanding hematomas is the gold standard.

-

•

Preoperative arterial embolization may reduce intraoperative bleeding on complete tumor removal.

Abbreviations: CEH, chronic expanding hematoma; FDG-PET, 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron-emission tomography; ND, no description; GIST, gastrointestinal stromal tumor; AML, angiomyolipoma

Keywords: Chronic expanding hematoma, Gallium scintigraphy, Adrenal tumors, Retroperitoneal tumors, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

A chronic expanding hematoma in the retroperitoneal space is a rare disease with poorly understood pathology, and preoperative diagnosis of such hematomas using conventional methods is sometimes difficult.

Presentation of case

A 68-year-old man with a history of slowly progressive abdominal distention was referred to our department for further evaluation. Contrast-enhanced CT revealed a large retroperitoneal tumor of the adrenal gland. MRI revealed that the tumor was iso-intense to hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging, with heterogeneous signal intensity on T1-weighted imaging without fat components. Angiography of the left adrenal artery confirmed many extravasations into the tumor. However, gallium scintigraphy showed no accumulation in the tumor. These findings were suggestive of a chronic expanding hematoma of left adrenal gland. This patient underwent complete tumor resection. Postoperative histopathological findings revealed a chronic expanding hematoma.

Discussion

Chronic expanding hematomas are slowly expanding, space-occupying masses as a result of trauma, surgery, or bleeding disorders. Chronic expanding hematomas mimic malignant tumors such as sarcomatous lesions. Although CT and MRI are used to obtain the diagnosis, the diagnosis is sometimes difficult. Gallium scintigraphs play a pivotal role in the differential diagnosis between them.

Conclusion

Gallium scintigraphs, magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography, are useful tools to differentiate chronic expanding hematomas from sarcomatous lesions.

1. Introduction

Chronic expanding hematomas (CEH) are slowly expanding, space-occupying masses that could persist for months or years as a result of trauma, surgery, or bleeding disorders. CEHs can develop in many locations, such as the head, chest, abdomen, and limbs [1]. However, a CEH in the retroperitoneal space is extremely rare [2]. Various types of soft tissue neoplasms that occur in the retroperitoneal space are usually differentiated using imaging modalities, such as CT and MRI. However, preoperative diagnosis of CEHs is sometimes difficult. Tokue et al. reported that CEHs mimic malignant tumors [3]. In this report, we present a case of a giant CEH within the adrenal gland, where preoperative gallium scintigraphy was a useful diagnostic tool. The work has been presented in line with the SCARE guideline [4].

2. Presentation of case

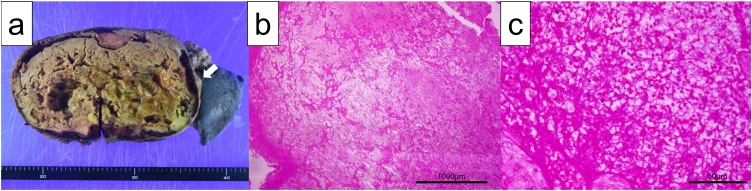

A 68-year-old man presented with a 3-month history of abdominal distention that had progressively increased. He had no history of abdominal trauma or surgery; however, he had been taking aspirin for 5 years (100 mg/day) to prevent cerebral stroke. However, he had no other relevant medical history. Physical examination confirmed a non-tender, left epigastric swelling. Hemoglobin concentration decreased (11.5 g/dL), liver and renal function tests were normal, and the levels of carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 were within their normal ranges. The levels of pancreatic enzymes, including amylase (70 U/mL) and lipase (32 IU/mL), and hormones such as insulin (8.48 μIU/mL) and glucagon (191 pg/mL) were normal. The serum noradrenalin (0.83 ng/mL) and vanillylmandelic acid (27.7 ng/mL) concentrations were slightly elevated; however, the levels of renin (4.8 ng/mL/hr), adrenalin (0.04 ng/mL), dopamine (0.02 ng/mL), and homovanillic acid (17.5 ng/mL) were normal. The levels of procalcitonin (0.01 ng/mL) and C-reactive protein (0.3 mg/dl) were not suggestive of inflammation. Contrast-enhanced CT revealed a well-defined tumor that was heterogeneously enhanced with extravasation of contrast at the left adrenal site, which also showed pancreatic tail and left kidney involvement (Fig. 1a). MRI showed that the tumor was iso-intense to hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging and had heterogeneous intensity on T1-weighted imaging without fat components (Fig. 1b, c). Transcatheter angiography revealed extravasation in some parts of the tumor, mainly from the left adrenal artery (Fig. 1d). Gallium scintigraphy revealed no accumulation of contrast in the tumor (Fig. 1e). This finding excluded malignant tumors, such as liposarcoma and sarcoma. Therefore, a preoperative diagnosis of a benign tumor, such as a CEH derived from the left adrenal gland, was made. Intraoperative findings revealed that the tumor was encapsulated and tightly adhered to the colic mesentery, pancreatic tail, left kidney and adrenal gland without invading the psoas muscle. We first mobilized the spleen with the pancreas, transverse and descending colon, and left Kidney. Thereafter, the pancreatic tail and the adhering colonic mesentery were resected without a colectomy. Finally, after resection of the renal artery and vein, complete tumor resection was performed with distal pancreatectomy, left nephrectomy, and adrenalectomy. The resected specimen was a tumor measuring 25 × 23 cm in diameter and composed mainly of necrotic tissue and fibrin, surrounded by a capsule and fused to the left adrenal gland (Fig. 2a). Histopathological findings revealed dense fibrous and necrotic connective tissue with old clots, and there was no evidence of viable cells (Fig. 2b, c). Therefore, the patient was diagnosed with a CEH arising from the left adrenal gland. The patient was discharged from the hospital 3 weeks postoperatively without any complications. There was no recurrence of the tumor 6 months after the surgery.

Fig. 1.

Radiological findings. (a) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showing a well-demarcated tumor with heterogeneously enhanced areas of density with extravasation of the contrast. (b) Magnetic resonance imaging showing iso-intensity to hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging (b) and heterogeneity on T1-weighted imaging without fat component (c). (d) Angiography through the left renal artery showing extravasation (arrow) in the tumor, mainly from the left adrenal artery (arrow head). (e) Gallium scintigraphy showing no accumulation of contrast within the tumor.

Fig. 2.

Macroscopic and microscopic findings of resected specimen. The mass contained necrotic tissue and fibrin, a partially organized hematoma and fused with the left adrenal gland (arrow) (a). Histopathological findings showing a hematoma surrounded by fibrous tissues (b: ×12.5, c: ×200).

3. Discussion

A CEH in the retroperitoneal space is extremely rare. Following a literature search in PubMed, there were only 11 reported cases of the retroperitoneal space hematomas and 3 reported cases within the adrenal gland, including this case [1,2,[5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11]] (Table 1). In this patient, CEH was supplied from left adrenal artery. Moreover, the mass fused to the left adrenal gland. Therefore, this mass must have derived from the left adrenal gland. The mechanism of expansion of such hematomas remains known [3]; however, some possible mechanisms have been suggested. Hematomas develop in patients after trauma, or surgery [12]. In this case, the patient was receiving antiplatelet drugs and had no history of trauma. Therefore, antiplatelet therapy may have induced a CEH in this patient.

Table 1.

Previously reported cases of chronic expanding hematoma in the retroperitoneal space.

| Case No. | Year | Age/Sex | Tumor Size (cm) | Tumor Location | Tumor Origin | Cause | Postoperative Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1980 | 79/M | ND | right iliac fossa | ND | hernioplasty | ND |

| 2 | 1980 | ND/M | 8.0 | above left kidney | ND | nephrectomy | ND |

| 3 | 2003 | 59/M | 12.0 | above left kidney | Adrenal gland | ND | ND |

| 4 | 2005 | 65/M | 8.0 | right iliac fossa | ND | warfarin | ND |

| 5 | 2005 | 70/M | 18.0 | below right kidney | ND | ureteral lithotripsy | 13 months, no recurrence |

| 6 | 2005 | 53/M | 12.0 | iliopsoas | Psoas muscle | trauma | 6 months, no recurrence |

| 7 | 2009 | 34/F | 12.0 | above right kidney | ND | ND | 20 months, no recurrence |

| 8 | 2013 | 69/M | 20.0 | below left kidney | ND | ND | 24 months, no recurrence |

| 9 | 2014 | 72/M | 20.0 | below left kidney | Iliopsoas muscle | ND | 3 months, no recurrence |

| 10 | 2015 | 67/M | 16.0 | Left adrenal gland | Adrenal gland | aspirin and warfarin | ND |

| 11 | Present case | 68/M | 25.0 | above left kidney | Adrenal gland | aspirin | 5 months, no recurrence |

The differential diagnosis of retroperitoneal tumors based on imaging becomes crucial. The findings of CT and MRI can facilitate the differential diagnosis of retroperitoneal tumors [13]. Additionally, these categorize retroperitoneal masses as solid or cystic. Solid tumors include those associated with lymphoma; liposarcoma; malignant fibrous histiocytoma; leiomyosarcoma; angiosarcoma; neurogenic tumor; germ-cell tumor and benign tumors, including CEHs. Sarcomatous lesions have similar findings on CT and MRI compared with CEHs; the CT findings of sarcomatous lesions include nodules with heterogenous enhancement and occasionally, calcifications. MRI findings of sarcomatous lesions demonstrate heterogeneously low intensity on T1-weighted imaging and heterogeneously high intensity on T2-weighted imaging. This contrast with the CT findings of CEH, which show a heterogeneous mass with a wall of variable thickness that often contains peripheral areas of calcification [14]. On MRI, a CEH has signal intensities ranging from high to low—the so-called mosaic sign. The different signal intensities indicate the presence of fresh and old blood [15]. However, use of only CT and MRI findings cannot narrow the differential diagnosis between sarcoma and CEH. Other modalities in addition to MRI and CT are required to obtain a preoperative diagnosis (Table 2).

Table 2.

The differences of radiological findings of retroperitoneal tumors.

| MRI |

CT |

Gallium scintigraphy | FDG-PET | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1WI | T2WI | Fat suppression | Calcification | Plain | Contrast-enhanced | |||

| Lymphoma | iso | iso~high | – | absent | iso~high | mildly homogenous enhancement | + | ++ |

| Liposarcoma | low~high | high | + | possible | low | heterogenous enhancement | + | ++ |

| Malignant fibrous histiocytoma | low | low~high | – | absent | iso~high | heterogenous enhancement | + | ++ |

| Leiomyosarcoma | low | low | – | possible | low~high | heterogenous enhancement | + | ++ |

| Angiosarcoma | low~high | high | – | absent | low | heterogenous enhancement | + | ++ |

| Neurogenic tumor | low~iso | low | – | possible | low~iso | heterogenous enhancement | + | + |

| Germ-cell tumor | low~high | low~high | – | possible | low~high | heterogenous enhancement | + | + |

| Carcinoid | low | low~high | – | possible | low | heterogenous enhancement | + | + |

| GIST | low~iso | high | – | possible | low | heterogenous enhancement | + | ++ |

| Pheochromocytoma | low | high | – | possible | iso | moderately homogenous enhancement | + | ++ |

| Chronic expanding hematoma | low~high | iso~high | – | possible | low~high | heterogenous enhancement | – | + |

| Hemangioma | low | high | – | possible | low | persistent enhancement | – | – |

| Lipoma | low~high | high | + | absent | low | – | – | – |

| Neurogenic tumor | low | iso~high | – | possible | iso | mildly heterogenous enhancement | – | – |

| Adenoma | low~hyper | low~hyper | – | possible | low~iso | homogenous enhancement | – | – |

| AML | high | low | + | absent | low | heterogenous enhancement | – | – |

(–): no uptake, (+): mild uptake, (++): strong uptake.

In general, gallium scintigraphy can help differentiate a malignant tumor from a benign one, as gallium-citrate does not accumulate in benign tumors. Hata et al. reported that CEH had no accumulation of gallium [16]. This feature was also seen in this case. This finding could play a pivotal role in the differential diagnosis of retroperitoneal tumors. However, Southee et al. reported that 52 of 56 patients (93%) had accumulation of gallium, while four cases were determined to be false-negatives for leiomyosarcoma, epitheloid sarcoma, and liposaroma [17]. We must pay attention to the possibilities of false-negatives on gallium scintigraphy as one of the tools for differential diagnosis (Table 2).

2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron-emission tomography (FDG-PET) may also help narrow down the differential diagnosis of the retroperitoneal tumors. However, it has been reported that FDG-PET of a CEH reveals positive uptake of FDG [3]. Therefore, FDG-PET may not be a useful tool for differential diagnosis between sarcoma and CEH.

The discrepancy of these gallium scintigraphy and FDG-PET findings may help narrow down the differential diagnosis between CEHs and other retroperitoneal tumors. This discrepancy may be caused by the mechanism of uptake of gallium and FDG. The mechanisms of gallium uptake include leukocyte labeling and lactoferrin, lactoferrin, ferritin, and siderophores binding [18], leading to accumulation of gallium in the tumor or abscess. In contrast, the molecular mechanisms of FDG imaging relate to its uptake by glucose transporter 1 and metabolism by hexokinase and glucose-6-phosphatase [19]. These mechanisms result in the accumulation of FDG in the tumor. These molecular mechanisms of uptake produce the differences between gallium scintigraphy and FDG-PET.

The gold standard treatment for a CEH is complete excision of the hematoma along with its fibrous capsule [1]. There are some treatment options, including trans-arterial embolization, aspiration, and drainage. However, these procedures can result in bleeding or recurrence [2,17,20]. In this case, we performed a surgical procedure to prevent recurrence of the CEH and improve epigastric distress. In this case, surgical removal of the kidney and the tail of pancreas was required. Although we tried to preserve these organs, the CEH was strongly adherent to them, and preservation was associated with a high risk of bleeding and pancreatic and urinary fistula. Therefore, we could not exfoliate and preserve them. Trans-arterial embolization is a useful procedure to reduce intraoperative bleeding [21]. We should have performed this procedure preoperatively.

4. Conclusion

A retroperitoneal tumor in a patient receiving antiplatelet therapy may be a CEH. The other differential diagnoses are soft tissue sarcoma and chronic abscess. We need to accumulate enough cases to better understand the effectives of gallium scintigraphy in detection of CEHs. However, these modalities, in addition to conventional imaging, including MRI and CT, may help differentiate a CEH from soft tissue malignant tumors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

All authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

All authors listed have no source of funding to disclose.

Ethical approval

Our institutional review board does not require case reports to be submitted for ethical approval.

Consent

Written Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

Hiroki Kajioka: study concept, design, data collection, writing the paper.

Toshiaki Morito: interpretation (pathology part).

Yasutaka Kokudo: writing the paper.

Atsushi Muraoka: writing the paper.

Registration of research studies

Our paper is a case report, no registration was done for it.

Guarantor

Hiroki Kajioka.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Contributor Information

Hiroki Kajioka, Email: hiroki_kajioka@yahoo.co.jp.

Toshiaki Morito, Email: morito_15j@yahoo.co.jp.

Yasutaka Kokudo, Email: yasutaka@kagawah.johas.go.jp.

Atsushi Muraoka, Email: amuraoka@kagawah.johas.go.jp.

References

- 1.Syuto T., Hatori M., Masashi N., Sekine Y., Suzuki K. Chronic expanding hematoma in the retroperitoneal space: a case report. BMC Urol. 2013;13:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-13-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irisawa M., Tsukuda S., Amanuma M., Heshiki A., Kuroda I., Ogawa F. Chronic expanding hematoma in the retroperitoneal space: a case report. Radiat. Med. 2005;23:116–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tokue H., Tokue A., Okauchi K., Tsushima Y. 2-[18F]-2-deoxy-d-glucose (FDG) positron-emission tomography (PET) findings of chronic expanding intrapericardial hematoma: a potential interpretive pitfall that mimics a malignant tumor. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2013;8:13. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agha R.A., Borrelli M.R., Farwana R., Koshy K., Fowler A., Orgill D.P., For the SCARE Group The SCARE 2018 statement: updating consensus surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2018;60:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reid J.D., Kommareddi S., Park M.C. Chronic expanding hematomas: a clinicopathologic entity. JAMA. 1980;244:2441–2442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamada T., Ishibashi T., Saito H., Sato A., Matsuhashi T., Takahashi S. Case report: chronic expanding hematoma in the adrenal gland with pathologic correlations. J. Comput. Assist. Tomogr. 2003;27:354–356. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200305000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamada K., Myoui A., Ueda T., Higuchi I., Inoue A., Tamai N. FDG-PET imaging for chronic expanding hematoma in pelvis with massive bone destruction. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34:807–811. doi: 10.1007/s00256-005-0895-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamasaki T., Shirahase T., Hashimura T. Chronic expanding hematoma in the psoas muscle. Int. J. Urol. 2005;12:1063–1065. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2005.01209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaneko G., Shirakawa H., Kozakai N., Hara S., Nishiyama T., Shitoh A case of chronic expanding hematoma in retroperitoneal space. Hinyoukika Kiyo. 2009;55:603–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kubota M., Kanno T., Nishiyama R., Okada T., Higashi Y., Yamada H. A case of chronic expanding hematoma with xanthogranuloma in retroperitoneal space. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2015;61:159–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sunada T., Kobayashi T., Furuta A., Shibuya S., Okada Y., Negoro H. Large retroperitoneal mass diagnosed as adrenal chronic expanding hematoma. Urology. 2015;86:e17–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2015.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pasku D., Bano A., Lagoudaki E., Alpantaki K. Katonis P: spontaneous and enormous, chronic expanding hematoma of the lumbar region: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:9400. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-2-9400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rajiah P., Sinha R., Cuevas C., Dubinsky T.J., Bush W.H., Jr, Kolokythas O. Imaging of uncommon retroperitoneal masses. Radiographics. 2011;31:949–976. doi: 10.1148/rg.314095132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akata S., Ohkubo Y., Jinho P., Saito K., Yamagishi T., Yoshimura M. MR features of a case of chronic expanding hematoma. Clin. Imaging. 2000;24:44–46. doi: 10.1016/s0899-7071(00)00161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwon Y.S., Koh W.J., Kim T.S., Lee K.S., Kim B.T., Shim Y.M. Chronic expanding hematoma of the thorax. Yonsei Med. J. 2007;48:337–340. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2007.48.2.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hata Y., Sakamoto S., Shiraga N., Sato K., Sato F., Otsuka H. A case of chronic expanding hematoma resulting in fatal hemoptysis. J. Thorac. Dis. 2012;4:508–511. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2012.08.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Southee A.E., Kaplan W.D., Jochelson M.S., Gonin R., Dwyer J.A., Antman K.H. Gallium imaging in metastatic and recurrent soft-tissue sarcoma. J. Nucl. Med. 1992;33:1594–1599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoffer P. Gallium: mechanisms. J. Nucl. Med. 1980;21:282–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Torizuka T., Tamaki N., Inokuma T., Magata Y., Sasayama S., Yonekura Y. In vivo assessment of glucose metabolism in hepatocellular carcinoma with FDG-PET. J. Nucl. Med. 1995;35:1811–1817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamamoto S., Momose T., Aoyagi M., Ohno K. Spontaneous intracerebral hematomas expanding during the early stages of hemorrhage without rebleeding. Report of three cases. J. Neurosurg. 2002;97:455–460. doi: 10.3171/jns.2002.97.2.0455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuwata T., Uramoto H., Tanaka F. Preoperative embolization followed by palliative therapy for patients unable to undergo the complete removal of a chronic expanding hematoma–a case report. Asian J. Surg. 2013;36:40–42. doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]