Abstract

Long-term caloric restriction (CR) has been shown to be beneficial to various tissues and organs. In contrast, CR exerts differential effects on bone, which could be due in part to the nature of the protein regime utilized. Male Sprague Dawley rats (8-month-old) were subjected for 12 months to 40% CR in macronutrients and compared with rats fed ad libitum for the same period. Casein- and soy-fed groups were compared. There was a significant decrease in bone quality in both CR groups, which was independent of the source of protein in the diet. In contrast, the group fed soy protein ad libitum showed better bone quality and higher levels of bone formation compared with casein-fed animals. Notably, bone marrow adipocytes were not mobilized upon CR as demonstrated by an absence of change in adipocyte number and tissue expression of leptin. This study demonstrates that the negative effect of CR on bone quality could not be prevented by the most common protein regimes.

Keywords: Caloric restriction, Osteoporosis, Bone, Marrow adipose tissue, Sirt1, PPARγ

In addition to a reduction in bone mass, osteoporosis in older people is characterized by the accumulation of fat within the bone marrow at the expense of bone tissue (1). Caloric restriction (CR) has been shown to delay the development and the severity of age-related diseases in multiple organs and systems (2). Considering that CR reduces white fat mass in several tissues (3), it might be expected to exert a preventive effect from the appearance of bone loss and osteoporosis. However, several studies have shown that this is not the case. Behrendt and colleagues showed that CR reduced cortical femoral mineral density and thickness, which was also associated with reduced femoral failure force (4). The same changes were observed in both lifelong and short-term CR groups. In addition, CR has been associated with an increase in marrow fat in animals (5) and humans (6). This increase in marrow fat could have deleterious consequences on bone due to adipocyte-induced lipotoxicity, which could affect osteoblastogenesis and increase osteoclastic activity (1).

Previous studies on rat models of CR have demonstrated that the potentially undesirable effects of CR could be prevented using different dietary protein sources. For example, Iwasaki and colleagues have shown that, in contrast to casein-fed animals, those fed soy showed longer survival and lower incidence of nephropathy (7). Since soy protein diet has demonstrated a beneficial effect on bone by increasing bone mass due to its phytoestrogenic effect (8), we therefore hypothesized that using soy protein as the main source of dietary protein could not only prevent the bone loss seen in CR animals but also influence the potential changes in bone marrow fat induced by CR. The objective of the present study was to investigate the effect of a long-term 40% CR, implemented at 8 months, in combination with either casein or soy, on tibial bone quality and marrow fat in aging male Sprague Dawley rats.

Methods

Animals and Experimental Procedures

Two-month-old male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles Rivers Canada, St-Constant, QC) were individually housed in wire-bottom cages, in a room under controlled temperature (22°C), humidity and lighting (cycles of 12 hours: lights on at 07:00 hours, ambient light intensity of 45 Lux). Male rats were selected to avoid the effect of estrogenic deprivation on bone during menopause. The animals were fed chow diet containing 20% casein or soy, 20% sucrose, 29.5% corn starch, 14% maltodextrin, 5.5% corn oil, 5% cellulose, 3.5% vitamin mix, 0.3% methionine, 0.3% choline bitartrate, and 0.001% tertiary butylhydroquinone (AIN-93G, Harland, Teklad, Madison, WI). At 8 months, each group (casein- and soy-fed) was randomized in two groups: ad libitum-fed and 40% CR. Implementation at this age allows to avoid interference with the period of normal growth and development. CR animals received a diet enriched in vitamins and minerals (TD.130771) to ensure that both groups received comparable amounts of micronutrients. Ad libitum rats were fed a comparable control diet (Charles River Rodent Diet # 5075, St-Constant, Canada; composition: Prot 21%, Carb 66%, Fat 13%). Rats were subjected to a 20% restriction for 2 weeks and 40% thereafter. All animals had free access to water. Body weight (BW) and food intake were recorded every 2 weeks. Four groups (n = 10 per group) of aged rats were studied: AC = ad libitum- and casein-fed, AS = ad libitum- and soy-fed, RC = 40% CR and casein-fed, RS = 40% CR and soy-fed. Aging rats were weighted regularly until sacrifice. They were sacrificed at 20 months of age along with 2-month-old ad libitum casein-fed rats (n = 10), between 08:30 and 10:30 hours, by complete blood withdrawal via the abdominal aorta under pentobarbital anesthesia (5 mg/100 g BW). Macroscopic evaluation indicated the absence of major pathology or tumor. The animal protocol was approved by the animal Care Committee of the University of Montreal in compliance with the guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care. The aging rats were supplied by the Aging Rat Colonies platform from the Quebec Network for studies on aging (www.rqrv.com). All analyses were performed essentially as described previously (9,10).

Serum Biochemistry

Serum biochemistry was determined at the Rodent Diagnostics Lab (McGill University, Montréal, Canada) using routine automated techniques as previously described (10) (refer to Supplementary Methodology).

Immunohistochemistry, Immunofluorescence and Oil Red Staining of Bone Marrow Fat

Described in Supplementary Methodology.

Statistical Methods

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Comparisons among the young and aged groups were made by ANOVA followed by Neuman–Keul’s test to determine statistical differences between specific groups. Comparisons of the ad libitum-fed and CR rats with different protein sources were made by 2 × 2 ANOVA. In some cases, comparisons between specific groups were made by Student’s t-test. In all experiments, a p value of <.05 was considered significant.

Results

Effect of Aging and Diets on BW, Body Mass Index, and Length

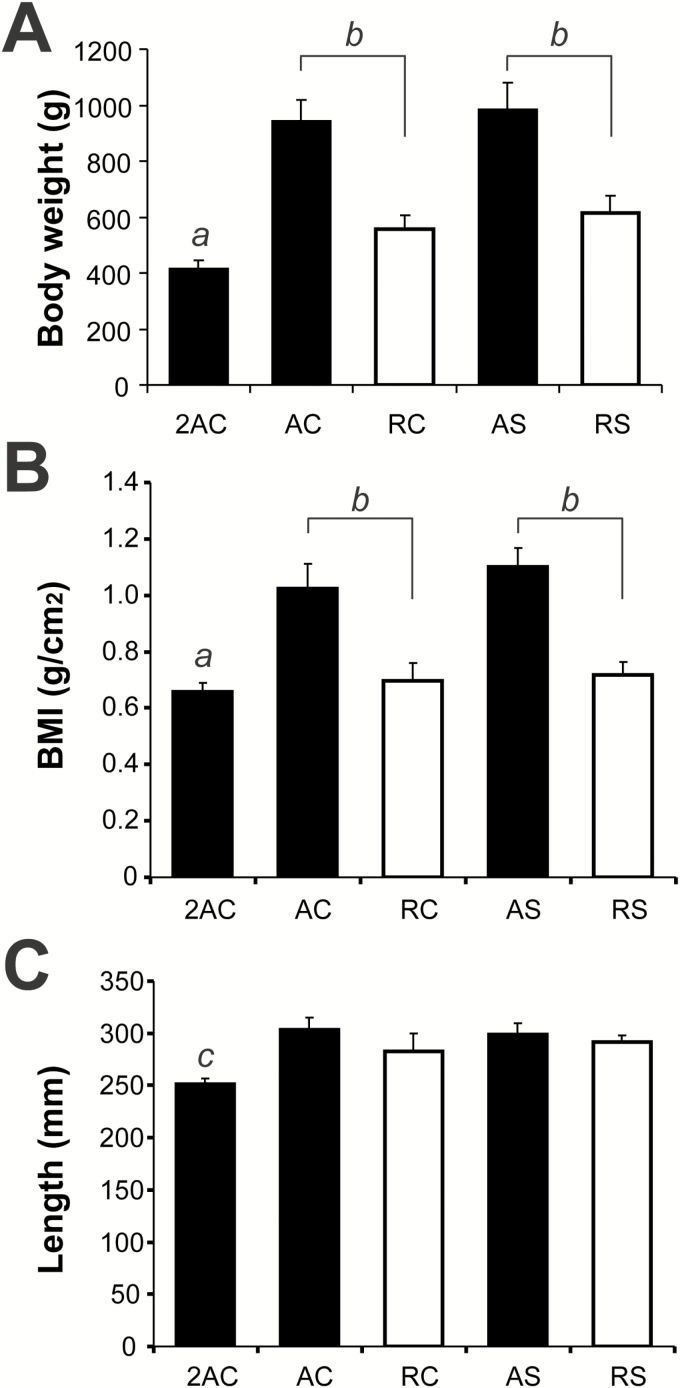

BW was similar in all groups at 2 months of age (Figure 1A). The effect of age and dietary interventions was examined in four groups of aged rats: AC = ad libitum- and casein-fed, AS = ad libitum- and soy-fed, RC = 40% CR and casein-fed, RS = 40% CR and soy-fed were compared with 2-month-old AC rats. Differences on BW, body mass index (BMI), and length at 20th month are presented in Figure 1. Age-related changes in BW under different conditions (~2.5-fold in the ad libitum-fed groups and ~1.5-fold in the CR groups) were similar to those observed in a previous study (11).

Figure 1.

Effect of long-term caloric restriction (CR) and dietary protein source on body weight (A), body mass index (BMI) (B), and total length (C) of aged rats. Eight-month-old rats (N = 10 per group) were exposed to 12 months of CR (40%) or fed ad libitum and received either casein or soy as protein source. (A) All aged groups showed a significant increase in body weight as compared with their 2-month-old ad libitum-fed controls (2AC) (a, p < .001). When compared with aged rats fed ad libitum with either casein (RC) or soy (RS) protein, CR rats (RC and RS) showed a significant reduction in body weight (b, p < .001). In the case of BMI (B), all aged groups showed a significant increase in BMI as compared with their 2AC controls (a, p < .01). Additionally, aged CR rats showed a significant reduction in BMI as compared with their ad libitum-fed counterpart (b, p < .01). Finally, rats length (C) significantly increased in both CR and ad libitum fed groups when compared with 2-month-old controls (c, p < .01) with nonsignificant difference in length seen between the CR and ad libitum aged rats.

Effects of Aging and Diets on Tibial Bone Quality

All 20-month-old rats showed a significant reduction in bone volume per tissue volume (BV/TV) when compared with the 2-month-old ad libitum controls (considered as 100% BV/TV). As shown in Supplementary Figure 1, CR rats (Supplementary Figure 1C, D, and G–I) fed either with casein or soy protein showed a significant decrease (~20%) in BV/TV in the proximal tibial epiphysis when compared with old rats fed ad libitum (p < .05). In contrast, rats fed ad libitum receiving a soy protein regime (AS) showed a significant increase (~20%) in BV/TV when compared with the other three aged groups (p < .05; Supplementary Figure 1E, F, and I).

Effects of Aging and Diets on Serum Biomarkers and Calciotropic Hormones

A significant age-related decrease in markers of bone resorption (C-telopeptide) and formation (osteocalcin) was found in all 20-month-old groups compared with 2-month-old controls (p < .001) (Supplementary Figure 2A and B). No diet effect was seen for serum C-telopeptide in all 20-month-old groups. However, the decrease in osteocalcin levels was significantly smaller in the AS group (p < .01), compared with other old groups, suggesting that ad libitum soy could stimulate bone formation. In contrast, the RS group showed the lowest levels of osteocalcin (p < .01). As previously reported using other conditions of CR in aging rats (12), an important increase in serum PTH levels was present in 20-month-old ad libitum-fed casein and soy rats (Supplementary Figure 2C; p < .001), which was attenuated by CR. Finally, differences in serum PTH were not associated with any significant difference in serum levels of vitamin D (25OH; Supplementary Figure 2D).

Effects of Aging and Diets on Bone Marrow Adiposity

As shown in Figure 2A and B, there was an age-related increase in bone marrow fat volumes in all 20-month-old groups, CR and fed ad libitum, when compared with the 2-month-old controls (p < .01); with the AS group showing the lowest number of adipocytes (p < .05). Both CR groups showed significantly higher adipocyte number independently of the type of protein in the diet (p < .01). Furthermore, given the proposed role of leptin in fat metabolism and bone growth, leptin immunoreactive levels within the bone marrow were quantified (Figure 2C and D) and compared with serum levels of leptin (Figure 2E). As previously reported (13), serum levels of leptin were significantly increased with aging and reduced by CR (p < .001; Figure 2E) likely due to the decrease of adipose tissue mass outside the bones. However, quantification of leptin immunoreactivity/marrow area, although increased by aging (p < .001; Figure 2C and D) did not show differences between diets suggesting that local expression of leptin within the bone marrow was not affected by CR (Figure 2C), and in agreement with the fact that marrow adipocytes did not seem to be mobilized by CR.

Figure 2.

Quantification of tibial bone marrow adipocytes and leptin in caloric restriction (CR) rats receiving either casein or soy and submitted or not to long-term CR. (A) Longitudinal sections of proximal tibiae from 2-month-old rats fed ad libitum (2AC) and 20-month-old rats fed ad libitum or CR receiving either casein or soy as protein sources (N = 10 per group). Using sections stained with haematoxylin/eosin (H/E) we quantified adipocyte number (AD#, 1 mm). Individual adipocytes were traced out in all the fields analysed as previously described (10); adipocytes appear as distinct, translucent, yellow ellipsoids in the marrow cavity. Adipocyte number (B) was quantified by three different observers looking at 10 different fields per section. A marked increase in adipocyte number was seen in all aged groups when compared with 2-month-old controls (2AC; a, p < .01). Additionally, the AS rats showed a significantly lower number of adipocytes per field as compared with all the other aged groups (b, p < .05). Note that most of the bone marrow (BM) space is occupied by fat (empty spaces) in all aged groups. Tr = bone trabeculae. Magnification at source was ×40. Micrographs are representative of four to six screened in each group of animals. (C) Immunofluorescence analysis of leptin within the bone marrow and serum leptin in 2-month-old (2AC) and 20-month-old rats fed ad libitum or CR, receiving either casein or soy protein as protein sources. A marked age-related increase in leptin expression/marrow area was observed in all aged groups (a, p < .001) with no significant difference found between aged groups (D). Serum leptin (E) was significantly higher in all the aged groups (a, p < .05). Independently of the protein source, CR significantly decreased serum levels of leptin in aged rats when compared with rats fed ad libitum (b, p < .001). Magnification at source was ×40. Micrographs are representative of four to six screened in each group of animals.

Effects of CR and Diets on PPARγ and Sirt1 Expression in Old Rats

The sirtuin family of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-dependent deacetylases plays an important role in aging and metabolic regulation. Among the sirtuin family, CR upregulates Sirt1 in white adipose tissue where it modulates white adipocyte differentiation through the repression of PPARγ and promotes fatty acid mobilization (14). To assess whether CR has a similar effect on PPARγ and Sirt1 in bone marrow fat, differences in PPARγ and Sirt1 immunoreactive levels were examined (Figure 3). Compared to the casein-fed groups, both soy-fed groups (AS and RS) showed a significant reduction in PPARγ expression (p < .01), with RS rats showing the lowest level of PPARγ expression (p < .001) (Figure 3A and B). Within the soy-fed groups, CR rats (RS) showed significantly lower PPARγ expression than the ad libitum group (p < .01). Furthermore, immunofluorescence localization of Sirt1 was significantly increased in both CR groups compared with the age-matched ad libitum groups (Figure 3C and D) with a significantly higher expression in the casein fed group (p < .01).

Figure 3.

PPARγ and Sirt1 immunoreactive levels of tibiae of aged rats fed casein or soy and submitted or not to long-term caloric restriction (CR). (A) Immunofluorescence (left panels) and immunohistochemistry (right panels) analysis of PPARγ expression in aged rats either fed ad libitum or under CR and receiving either casein or soy protein. Quantification of PPARγ expression (B) shows a significant reduction in the soy-fed (AS and RS) when compared with the casein-fed aged rats (AC and RC) (a, p < .01), with RS rats showing the lowest level of PPARγ expression (b, p < .001) (A and B). Additionally, a significant difference between AS and RS groups was found (c, p < .01). Magnification at source was ×40. Fluorescence was quantified using image analysis software (Image Pro Plus 6.0, MediaCybernetics) and presented as cell mean intensity. Micrographs are representative of four to six tissue examination in each group of animals. (C) Immunofluorescence localization of Sirt1 protein. Levels of expression were quantified using the same image software and are shown in D and presented as cell mean intensity. The figure shows significantly upregulated expression in the CR aged rats fed either casein (RC) or soy (RS) compared with aged rats fed ad libitum (AC and AS) (a, p < .01). Sirt1 expression is significantly lower in RS when compared with RC group (b, p < .01). Micrographs are representative of four to six screened in each group of animals (N = 10 per group).

Discussion

Using old male Sprague Dawley rats, we have studied the impact of long-term CR implemented at 8 months of age and two dietary protein regimens, casein and soy, on the features of age-related bone loss. Changes in body weight was similar to those reported in previous studies (11). We report that the decrease in bone tibial quality and increased marrow adipogenesis associated with aging and CR was not prevented by the tested protein sources.

As in the present study, previous groups have reported a deleterious effect of CR on bone architecture and quality (4,15,16) together with a significant increase in marrow fat (5,6), thus the need for interventions that prevent this negative effect. A common feature of studies on the effect of CR is the use of casein as a source of dietary protein. In fact, casein has not been shown to have any effect on bone mass. In a model of male rats fed ad libitum in which casein was compared with soy as the source of protein, it was shown that casein had no apparent effects on bone microarchitecture whereas the soy fed rats showed a significant improvement in all the parameters in an animal model of osteoporosis fed ad libitum (17). An effect that could be associated with the beneficial phytoestrogenic effect of soy on bone (18), which is not expected to be found in casein reach diet.

In contrast with previous studies (18), we found that soy protein was unable to prevent or reduce the severe decline in bone structure and increased marrow adipogenesis observed in the CR groups. Indeed, rats fed ad libitum with soy protein showed significantly higher levels of bone volumes and lower marrow fat, with concomitant differences in biochemical markers of bone formation (osteocalcin) found in the same group with no effect on markers of bone resorption (C-telopeptide). This effect was also independent of either PTH or vitamin D levels.

In addition to adipocyte number, we also examined leptin expression within the bone marrow space. Leptin, which is highly expressed by adipocytes, has been associated with either stimulation or inhibition of bone formation depending on the cell origin of its secretion (19). Although CR was reported to reduce the local expression of leptin in other types of fat, this does not appear to be the case in bone marrow fat where none of the old groups, either CR or ad libitum-fed, showed a reduction in levels of leptin expression within the bone marrow independently of the reduction in serum levels, which could be interpreted as a lack of fat mobilization.

From a mechanistic point of view, we assessed whether CR aging rats receiving either casein or soy in their diet showed differences in the expression of two major genes that are affected by both aging and CR: PPARγ and Sirt1. PPARγ levels increase with aging in bone marrow leading to an increase in the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cell into adipocytes (1). Interestingly, both soy-fed groups showed a lower expression of PPARγ in bone marrow when compared with the casein-fed rats, the soy-fed CR group showing the lower PPARγ levels despite higher adipocyte differentiation compared with the respective soy-fed ad lib group. Thus, although these results confirm previous evidence on the inhibitory effect of soy on PPARγ, the steady high levels of marrow adipogenesis observed in those groups suggest that there are other PPARγ-independent adipogenic pathways that are activated by aging and CR. It is also possible that expression levels of PPARγ do not reflect its activity in the conditions studied. Both hypotheses deserve further exploration in future studies.

With respect to Sirt1 expression, CR induced higher levels of protein expression in the bone marrow of both soy and casein-fed groups, which was also associated with higher adipogenesis. These findings suggest that in contrast to the inhibitory effect of CR and Sirt1 on PPARγ in white adipose tissue (20), the increase in bone marrow adipocyte differentiation upon CR appears refractory to these protective mechanisms, as also evidenced by high leptin expression in this tissue. It is also possible that bone marrow mesenchymal cells are subjected to other hormonal cues in vivo compared with vitro settings, which could impact Sirt1 activity (21).

A potential limitation of our study is that our results only quantified the proximal tibia, which is composed primarily of regulated marrow adipose tissue (rMAT) as opposed to the distal tibia which is composed of constitutive marrow adipose tissue (cMAT) (22). Considering that the metabolic phenotype of these adipose depots is unique, we cannot conclude that the same effect applies to cMAT.

In conclusion, while testing the effect of two different protein regimes on CR-induced bone loss, we have found that neither casein nor soy protein regimes are able to prevent or reduce this bone loss. This refractory condition of bone to the source of protein administered under CR and the steady (and even increased) levels of marrow fat observed in CR animals suggest that marrow fat could be implicated in the biological phenomenon. Identification of those marrow fat-related mechanisms could provide new therapeutic targets aimed to prevent the bone loss that is observed not only under CR but also in other clinical conditions associated with severe bone loss such as drastic lower energy intake induced by anorexia nervosa and gastric bypass surgery.

Funding

This work was supported by a catalyst grant on aging research from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR; 200703IAP to G.D., G.F., P.G., and F.P.) and a pilot project grant from the Quebec Network for Research on Aging, a network funded by the Fonds de Recherche du Québec-Santé.

Conflict of Interest

None reported.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the technical assistance of Ms. Miren Gratton.

References

- 1. Singh L, Tyagi S, Myers D, Duque G. Good, bad, or ugly: the biological roles of bone marrow fat. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2018;16:130–137. doi: 10.1007/s11914-018-0427-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Golbidi S, Daiber A, Korac B, Li H, Essop MF, Laher I. Health benefits of fasting and caloric restriction. Curr Diab Rep. 2017;17:123. doi: 10.1007/s11892-017-0951-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Das M, Gabriely I, Barzilai N. Caloric restriction, body fat and ageing in experimental models. Obes Rev. 2004;5:13–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789x.2004.00115.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Behrendt AK, Kuhla A, Osterberg A, et al. Dietary restriction-induced alterations in bone phenotype: effects of lifelong versus short-term caloric restriction on femoral and vertebral bone in C57BL/6 mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31:852–863. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Devlin MJ, Cloutier AM, Thomas NA, et al. Caloric restriction leads to high marrow adiposity and low bone mass in growing mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:2078–2088. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bredella MA, Fazeli PK, Daley SM, et al. Marrow fat composition in anorexia nervosa. Bone. 2014;66:199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Iwasaki K, Gleiser CA, Masoro EJ, McMahan CA, Seo EJ, Yu BP. The influence of dietary protein source on longevity and age-related disease processes of Fischer rats. J Gerontol. 1988;43:B5–B12. doi: 10.1093/geronj/43.1.b5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hinton PS, Ortinau LC, Dirkes RK, et al. Soy protein improves tibial whole-bone and tissue-level biomechanical properties in ovariectomized and ovary-intact, low-fit female rats. Bone Rep. 2018;8:244–254. doi: 10.1016/j.bonr.2018.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Richard S, Torabi N, Franco GV, et al. Ablation of the Sam68 RNA binding protein protects mice from age-related bone loss. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:e74. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duque G, Li W, Adams M, Xu S, Phipps R. Effects of risedronate on bone marrow adipocytes in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2011;22:1547–53. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1353-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Keenan KP, Smith PF, Hertzog P, Soper K, Ballam GC, Clark RL. The effects of overfeeding and dietary restriction on Sprague-Dawley rat survival and early pathology biomarkers of aging. Toxicol Pathol. 1994;22:300–315. doi: 10.1177/019262339402200308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kalu DN, Hardin RR, Cockerham R, Yu BP, Norling BK, Egan JW. Lifelong food restriction prevents senile osteopenia and hyperparathyroidism in F344 rats. Mech Ageing Dev. 1984;26:103–112. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(84)90169-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moyse E, Bédard K, Segura S, et al. Effects of aging and caloric restriction on brainstem satiety center signals in rats. Mech Ageing Dev. 2012;133:83–91. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2012.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lomb DJ, Laurent G, Haigis MC. Sirtuins regulate key aspects of lipid metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1804:1652–1657. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McCay CM, Maynard LA, Sperling C, Barnes LL. Retarded growth, life span, ultimate body size and age changes in the albino rat after feeding diets restricted in calories. J Nutr. 1939;18:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. LaMothe JM, Hepple RT, Zernicke RF. Selected contribution: bone adaptation with aging and long-term caloric restriction in Fischer 344 x Brown-Norway F1-hybrid rats. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2003;95:1739–1745. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00079.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Soung DY, Devareddy L, Khalil DA, et al. Soy affects trabecular microarchitecture and favorably alters select bone-specific gene expressions in a male rat model of osteoporosis. Calcif Tissue Int. 2006;78:385–391. doi: 10.1007/s00223-005-0069-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zheng X, Mun S, Lee SG, et al. Anthocyanin-rich blackcurrant extract attenuates ovariectomy-induced bone loss in mice. J Med Food. 2016;19:390–397. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2015.0148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Williams GA, Callon KE, Watson M, et al. Skeletal phenotype of the leptin receptor-deficient db/db mouse. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:1698–1709. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Linford NJ, Beyer RP, Gollahon K, et al. Transcriptional response to aging and caloric restriction in heart and adipose tissue. Aging Cell. 2007;6:673–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00319.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Qu B, Ma Y, Yan M, et al. Sirtuin1 promotes osteogenic differentiation through downregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ in MC3T3-E1 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;478:439–445. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.06.154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Scheller EL, Doucette CR, Learman BS, et al. Region-specific variation in the properties of skeletal adipocytes reveals regulated and constitutive marrow adipose tissues. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7808. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.