Abstract

Introduction

The evolution of computed tomography (CT) findings in patients with mild coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia has not been described in detail. A large-scale longitudinal study is urgently required.

Methods

We analyzed 606 CT scans of 182 patients. The dynamic evolution of CT scores was evaluated using two staging methods: one was divided into 10 periods based on decile intervals, and the other was one stage per week. Moreover, the latter was used to evaluate the dynamic evolution of imaging performance. A published severity scoring system was used to compare findings of the two methods.

Results

In the dynamic evolution of 10 stages, the total lesion CT score peaked during stage 3 (9–11 days) and stage 6 (17–18 days), with scores = 7.19 ± 3.66 and 8.00 ± 4.57, respectively. The consolidation score peaked during stage 6 (17–18 days; score = 2.72 ± 3.07). In contrast, when a 1-week interval was used and time was divided into five stages, the total lesion score peaked during week 3 (score = 7.3 ± 4.15). The consolidation score peaked during week 2 (score = 2.54 ± 3.25). The predominant CT patterns differed significantly during each stage (P < 0.01). Ground-glass opacities (GGO), with an increased trend during week 3 and beyond, was the most common pattern in each stage (33–46%). The second most common patterns during week 1 were GGO and consolidation (24%). The linear opacity pattern with an increased trend was the second most common pattern during week 2 and beyond (21–32%).

Conclusions

The total lesion score of mild COVID-19 pneumonia peaked 17–18 days after disease onset. The consolidation scores objectively reflected the severity of the lung involvement compared with total lesion scores. Each temporal stage of mild COVID-19 pneumonia mainly manifested as GGO pattern. Moreover, good prognosis may be associated with increases in the proportions of the GGO and linear opacity patterns during the later stage of disease.

Keywords: COVID-19, Pneumonia, SARS-CoV-2, Tomography, X-ray computed

Key Summary Points

| The CT findings of patients with mild COVID-19 have not been explored in detail. |

| The existing total lesion CT score only considered the area of involvement of the lesions, but not the nature of the lesions. |

| We analyzed 606 CT scans of 182 patients and proposed a new scoring system based on the area and nature of the lesions. |

| The total lesions score of mild COVID-19 pneumonia peaked 17–18 days after illness onset, and week 2 after onset may be the critical period for disease progression. |

| The consolidation scores may objectively reflect the severity of lung involvement and thus serve as a more accurate diagnostic measure than total lesion scores. |

| The typical CT features of each stage of COVID-19 pneumonia were bilateral, multiple, and ill-defined, with a GGO pattern, which were located in the posterior and peripheral regions of both lungs. |

| Good prognosis may be associated with increases in the proportions of the GGO and linear opacity patterns during the later stage of disease. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a summary slide, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13007915.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) reported that as of July 6, 2020, there were ten million confirmed cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) worldwide, including 532,340 deaths [1]. These figures are updated daily, and subsequently, the situation has largely deteriorated depending on geographical location. Among confirmed cases reported in China, 81% of 72,314 patients experienced mild pneumonia [2]. Computed tomography (CT) is instrumental for screening and effective evaluation of patients with COVID-19 [3], and understanding CT performance is of vital clinical significance for controlling the pandemic.

Nevertheless, to our knowledge, the scope of studies investigating the evolution of CT findings in COVID-19 is limited [4–9]. For example, Wang et al. [5], Zhou et al. [6], and Pan et al. [8] focused on the evolution of imaging performance within 14 or 15 days after the onset of symptoms, while more than 14 or 15 days after illness onset was classified as the last stage. However, the time from illness onset to ICU admission is 12 (IQR 8, 15) days [10]. Therefore, focusing on 14 or 15 days after illness onset as the last stage may obscure a critical change in disease course. Furthermore, certain studies [6–9] analyzed patients with mild as well as severe pneumonia, which may bias the results. For example, Liang et al. [4] analyzed only the CT findings of patients who were not discharged from the hospital during the first 3 weeks after admission, and Shi et al. included only the initial CT date of all patients [7]. Therefore, a large-scale longitudinal study on the CT manifestations of patients with mild COVID-19 pneumonia is urgently required.

Here we describe the evolution of CT appearances in 182 patients with mild COVID-19 with definitive outcomes (all patients were discharged and none became severely or critically ill or died). We aimed to compare the CT findings across the disease courses and analyze the correlation between CT scores and inpatient days, which may be helpful for understanding the nature of disease and for optimally managing patients.

Methods

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Commission of Wuhan Third Hospital (Approved number KY2020-027), and informed consent was waived in accordance with the guidelines of the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences. The research study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, and its later amendments.

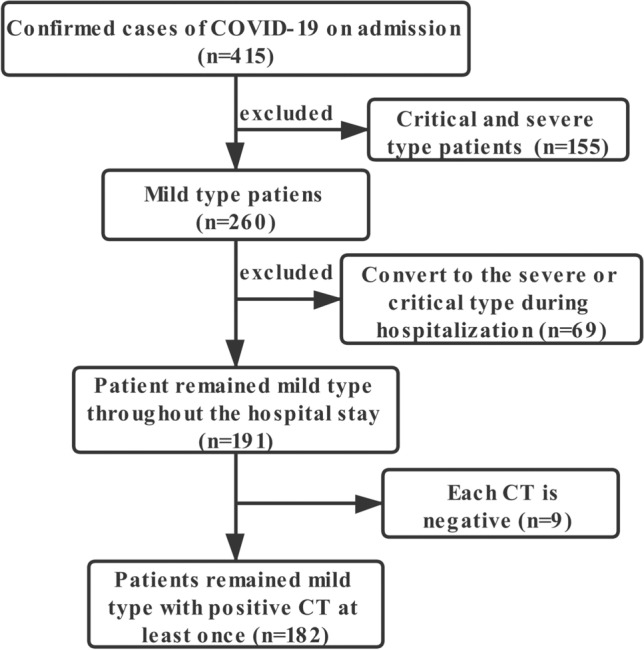

In this retrospective, single-center, longitudinal study we included 182 patients (Fig. 1) with confirmed COVID-19 admitted to the Wuhan Third Hospital (Tongren Hospital of Wuhan University) from January 21, 2020 to March 15, 2020. We used a published method for identifying SARS-CoV-2 infection [11]. The standards for discharge were absence of fever for more than 3 days, significant improvement in respiratory symptoms, obvious absorption of lesions in both lungs on CT, and negative SARS-CoV-2 RNA status in two consecutive nucleic acid tests (at least 1 day apart) of throat swabs [12]. In the present study, in accordance with WHO guidelines, mild COVID-19 pneumonia of adults was defined as COVID-19 pneumonia with no signs of severe pneumonia and no requirement for supplemental oxygen [13]. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients diagnosed with asymptomatic, mild, or moderate-type illness according to Chinese guidelines [12] who did not convert to the severe or critical type before discharge, (2) at least one positive CT, (3) recovery and discharge, and (4) age greater than 18 years.

Fig. 1.

Screening process of 182 patients with mild coronavirus disease 2019

CT

Chest CT images without contrast were acquired using a single inspiratory phase using two CT scanners (SOMATOM Definition AS, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany; uCT 760, United Imaging, Shanghai, China). All patients were supine when examined. The CT protocol was as follows: 120 kVp; 120–200 mA; slice thickness 5–10 mm; matrix 512 × 512; pitch 0.625. The reconstruction section thickness was 0.5–1 mm. We collected CT scans of patients from admission to discharge.

Image Analysis

Two radiologists with 15 and 10 years of experience in chest imaging, respectively, evaluated the CT images to reach a consensus diagnosis. Definitions of CT imaging features referred to in the Fleischner Society glossary and peer-reviewed literature on viral pneumonia [7, 14–16]. The observers reviewed the image features as follows: lung involvement, extent of lesion involvement, predominant location, margin definition, distribution, lung segments of lesion distribution, number of lung segments and lobes involved, predominant CT pattern (Fig. 2), pure ground-glass opacity (GGO), pure consolidation, GGO and consolidation, linear opacity, adjacent pleura thickening, nodules, round cystic changes, bronchiectasis, air bronchogram sign, bronchial wall thickening, interlobular septal thickening, crazy-paving pattern, pleural effusion, thoracic lymphadenopathy, honeycomb pattern, tree-in-bud, reversed halo sign, calcification, and cavitation. Observers referred to a severity scoring system [16].

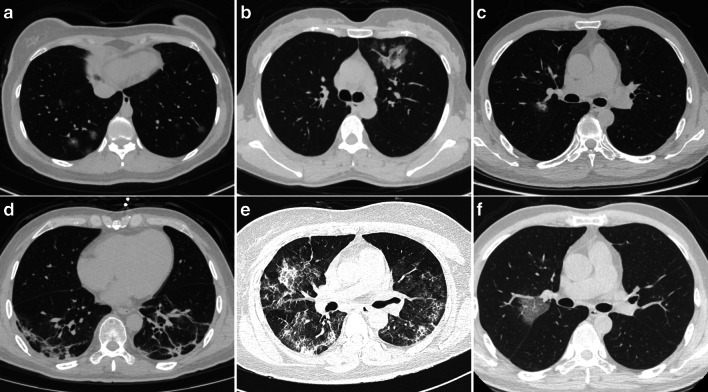

Fig. 2.

Predominant CT patterns of mild COVID-19 pneumonia. a GGO. b Consolidation. c GGO and consolidation. d Linear opacity. e Linear opacity, GGO, and consolidation. f Crazy-paving

Each lung was divided into upper, lower, and middle zones according to the horizontal lines through the carina and inferior pulmonary vein (six zones). The scoring rules for the involvement of each zone were as follows: score 0 = 0%; score 1, less than 25% involvement; score 2, 25% to less than 50%; score 3, 50% to less than 75%; and score 4, 75% or higher. The total severity score represents the sum of the scores of the six zones (possible scores, 0–24). The total lesion score represents the total score of involved lesions. We further evaluated the individual total scores for GGO, consolidation, and linear opacity of all lesions. To obtain detailed information about the dynamic evolution of CT features with disease progression, we divided the time axis into 10 periods according to the decile interval of the time from the onset of illness: stage 1 (1–5 days), stage 2 (6–8 days), stage 3 (9–11 days), stage 4 (12–14 days), stage 5 (15–16 days), stage 6 (17–18 days), stage 7 (19–21 days), stage 8 (22–25 days), stage 9 (26–30 days), and stage 10 (more than 30 days). The date of disease onset was defined as patients’ reported date of symptom onset. Moreover, studies evaluating the therapeutic effect of the COVID-19 typically required 1 week [17–19]. Therefore, to provide a reference for subsequent research on the evaluation of the therapeutic effects, we defined each week as one stage to further explore the dynamic changes in CT scores and imaging performance. The time axis was accordingly divided as follows: weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, and after 4 weeks. Finally, we analyzed the correlation between inpatient days and weekly CT scores.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics Software (version 25; IBM, New York, USA). Continuous variables are expressed as the mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile ranges (IQRs), as appropriate. Categorical variables are summarized as counts and/or percentages. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to evaluate the differences among continuous variables of each stage, and a trend test was performed using a polynomial contrast procedure. The chi-square test was used to evaluate the differences between categorical variables in each stage, and the trend test was used with the chi-square test or curve fitting. Correlation coefficients were then calculated between inpatient days and CT scores using Spearman correlation analysis. P values less than 0.05 (two-tailed) were considered significant, and the comparison between specific pairwise comparisons used the adjusted P value.

Results

Patients’ Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

In this research, 182 patients with 606 CT scans were ultimately enrolled. Patients’ median age was 58 years (IQR 45, 66; Table 1). The most common symptoms were fever (151, 83%) and cough (130, 71%). All patients met the discharge criteria, and the lung lesions of 3 (1.6%) patients were completely absorbed upon discharge.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of 182 patients with mild coronavirus disease 2019

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, years | 58 (45, 66) | |||

| Sex | Female | 101 (56%) | Male | 81 (45%) |

| Clinical features | ||||

| Symptoms | Fever | 151 (83%) | Cough | 130 (71%) |

| Fatigue | 53 (29%) | Diarrhea | 24 (13%) | |

| Expectoration | 17 (9%) | Inappetence | 12 (7%) | |

| Sore throat | 10 (6%) | Short of breath | 9 (5%) | |

| Headache | 9 (5%) | Muscle soreness | 9 (5%) | |

| Chills | 7 (4%) | Joint soreness | 5 (3%) | |

| Rhinorrhea | 3 (2%) | Palpitation | 2 (1%) | |

| Nausea | 3 (2%) | |||

| Inpatient days | 19 (15, 23) | |||

Data are median (interquartile ranges) or n (%)

CT Scores

Of the 606 CT scans (CTs), 17 were negative, and we therefore focused on the lesion scores and characteristics of the positive CTs.

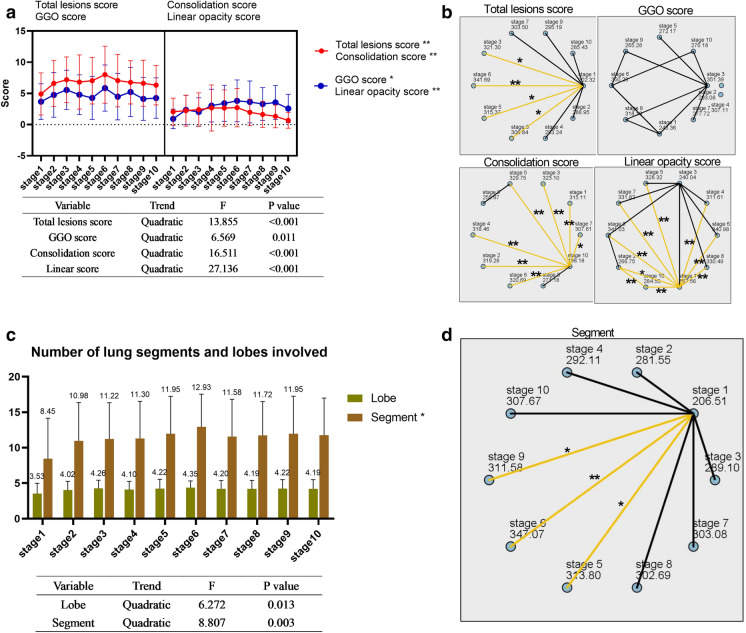

In the dynamic evolution of the 10 stages, the numbers of CTs of each stage were 53, 62, 54, 70, 55, 43, 64, 72, 59, and 57, respectively. There were significant differences between different stages in scores (Fig. 3a). The differences between specific pairwise comparisons are shown in Fig. 3b. We found two peaks in the changing trends of the total lesion scores: stage 3 (9–11 days) and stage 6 (17–18 days), scores = 7.19 ± 3.66 and 8.00 ± 4.57, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Dynamic changes of CT scores and numbers of lung segments and lung lobes involved during the 10 stages described in “Methods”. a The scores for total lesion, consolidation, linear opacity, and GGO of each stage and the significant results of trend tests are shown in the table below. b Statistical analysis of pairwise comparisons of CT scores of 10 stages. c The numbers of lung segments and lung lobes involved during the 10 stages and significant results of trend tests are shown in the table below. d Pairwise comparison of the numbers of involved lung lobes and lung segments during the 10 stages. Stage 1, 1–5 days; stage 2, 6–8 days; stage 3, 9–11 days; stage 4, 12–14 days; stage 5, 15–16 days; stage 6, 17–18 days; stage 7, 19–21 days; stage 8, 22–25 days; stage 9, 26–30 days; stage 10, more than 30 days. GGO ground glass opacity; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01

The three peaks of the GGO score occurred during stage 3 (9–11 days), stage 6 (17–18 days), and stage 8 (22–25 days), with scores of 5.56 ± 3.16, 5.86 ± 3.70, and 5.22 ± 3.93, respectively. The consolidation score peaked during stage 6 (17–18 days, score = 2.72 ± 3.07). The linear opacity score peaked during stage 6 (score = 3.81 ± 3.35). The numbers of lung segments and lobe involvement peaked during stage 6 (scores = 12.93 ± 4.61 and 4.35 ± 0.97, respectively), conforming to a quadratic function (Fig. 3c). Furthermore, there was a significant difference in the number of involved lung segments during different stages. Specific pairwise comparisons are shown in Fig. 3d.

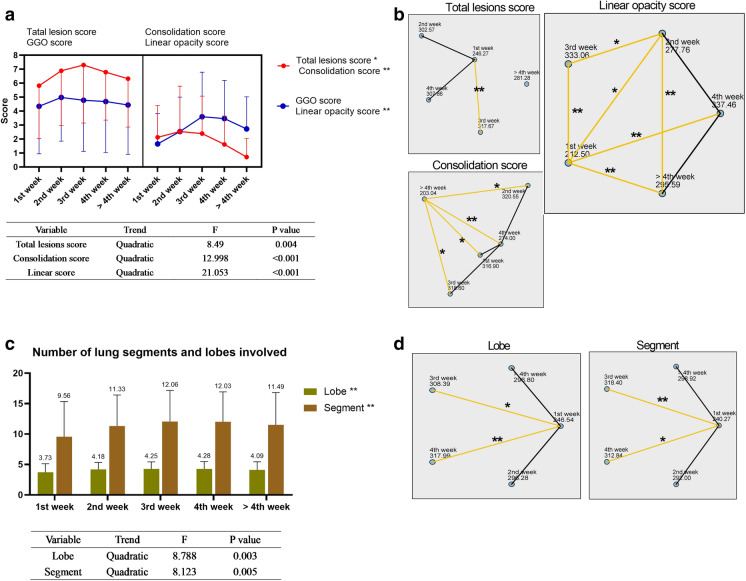

In contrast, when a 1-week interval was used and the time axis was divided into five stages, the numbers of CTs in each stage were 103, 136, 162, 109, and 79. In the dynamic evolution of five stages, there were significant differences in total lesions (P < 0.05), consolidation (P < 0.01), and linear opacity (P < 0.01) scores (Fig. 4a). The differences between the specific pairwise comparisons are shown in Fig. 4b. The total lesion score, GGO score, consolidation score, and linear opacity score peaked during week 3 (7.3 ± 4.15), week 2 (4.98 ± 3.13), week 2 (2.54 ± 3.25), and week 3 (2.54 ± 2.46), respectively. The total lesion score and GGO score showed significantly positive correlation with the inpatient days 4 weeks after the onset of the disease (r range 0.26–0.31, P < 0.05) (Table 2). The number of lung segments and the extent of lobe involvement remained high during weeks 2–4, and the curve conformed to a quadratic function (Fig. 4c). Further, there were significant differences in the numbers of lung segments and lung lobes involvement during each stage. The specific pairwise comparisons are shown in Fig. 4d.

Fig. 4.

Dynamic changes of CT scores and the numbers of lung segments and lung lobes involved in five stages. a The total lesion, consolidation, linear opacity, and GGO scores during each stage. Significant results of trend tests are shown in the table below. b Statistical analysis of pairwise comparisons of CT scores during five stages. c The numbers of lung segments and lung lobes involved during stages and significant results of trend tests are shown in the table below. d Pairwise comparison of the numbers of involved lung lobes and lung segments during 10 stages. GGO ground glass opacity; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01

Table 2.

Correlation between inpatient days and CT scores

| Time | Total lesion score | GGO score | Consolidation score | Linear opacity score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | – 0.03 (0.775) | – 0.07 (0.551) | – 0.09 (0.389) | – 0.01 (0.818) |

| Week 2 | 0.12 (0.215) | 0.09 (0.346) | – 0.03 (0.712) | 0.02 (0.849) |

| Week 3 | 0.10 (0.218) | 0.09 (0.304) | 0.001 (0.923) | 0.16 (0.057) |

| Week 4 | – 0.04 (0.698) | 0.04 (0.717) | – 0.13 (0.208) | 0.01 (0.885) |

| > Week 4 | 0.26 (0.047*) | 0.31 (0.017*) | – 0.16 (0.225) | 0.22 (0.076) |

Data are presented as r (P), where n is the total number of CT scans

*P < 0.05

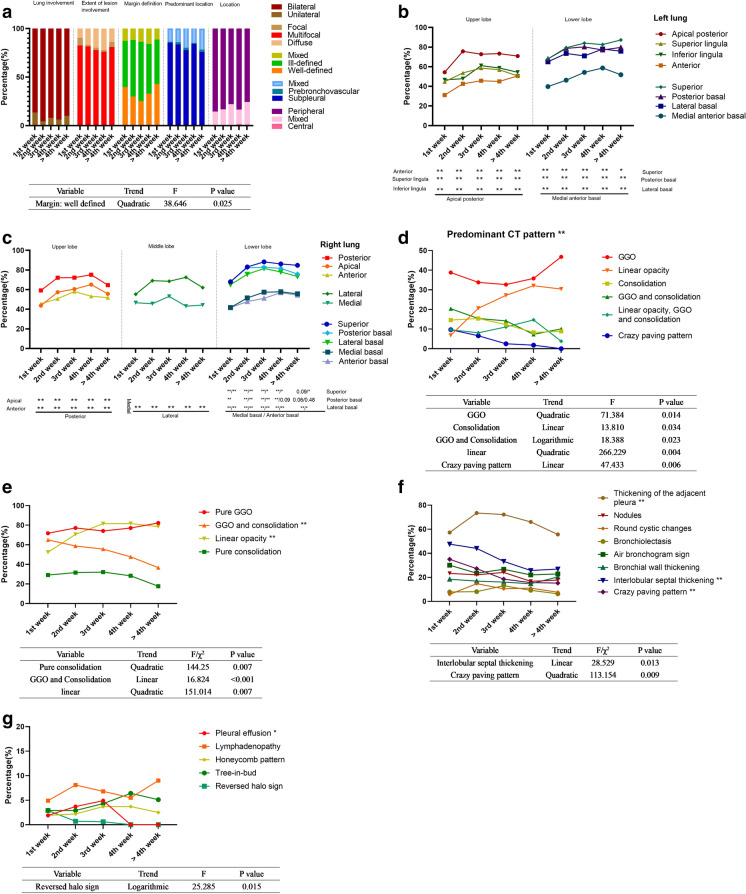

Imaging Features

Image features are summarized in Fig. 4. In each stage, lesions, which were mainly bilateral (86–94%), multiple (76–83%), and ill-defined (46–61%), were located in the subpleural (78–85%) and peripheral areas (78–85%) of both lungs. The percentages of the well-defined margins of the lesions conformed to a quadratic function (Fig. 5a). The lesions more frequently involved the apical posterior (54–76%), superior (68–87%), posterior basal (68–80%), and lateral basal segments (65–78%) of the left lung; and the posterior (59–75%), lateral (55–73%), superior (68–88%), posterior basal (68–83%), and lateral basal segments (65–82%) of the right lung (Fig. 5b, c). The predominant CT patterns differed significantly during each stage (P < 0.01), and GGO was the most common pattern in each stage (33–46%) (Fig. 5d). The percentages of the GGO and consolidation opacity exhibited a linearly decreasing trend (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5e).

Fig. 5.

Imaging manifestations of 182 patients during five stages. a Lung involvement, extent of lesion involvement, margin definition, predominant location, and distribution of the lesions during each stage. b Proportion of involvement of each lung segment of the left lung. c Proportion of involvement of each lung segment of the right lung. d Percentages of predominant patterns in each stage and significant results of trend tests are shown in the table below. e Percentages of pure ground glass opacity (GGO), pure consolidation, GGO and consolidation and linear opacity, and significant results of trend tests are shown in the table below. f The percentages during each stage of thickening pleura, nodules, round cystic changes, bronchiolectasis, air bronchogram sign, bronchial wall thickening, interlobular septal thickening, and crazy-paving pattern. Significant results of trend tests are shown in the table below. g Percentages during each stage of pleural effusion, lymphadenopathy, honeycomb pattern, tree-in-bud and reversed halo sign. Significant results of trend tests are shown in the table below. GGO ground glass opacity; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01

The proportion of the pure GGO maintained a high value during each stage (72–82%), peaking during stage 2 (week 2) and stage 5 (after 4 weeks). The changing trends of the percentages of pure consolidation and linear opacity were similar to the changing trends of the consolidation and linear opacity scores, and the percentages of both peaked during week 3. Among other imaging signs, pleural thickening (56–74%), interlobular septal thickening (26–48%), and the crazy-paving pattern (15–35%) were relatively common, while lymphadenopathy (5–9%), pleural effusion (0–5%), and reversed halo signs (0–3%) were relatively infrequent (Fig. 5f, g).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, of all the longitudinal CT performance studies of COVID-19 pneumonia [4–8], the present study analyzed the largest number of patients. Through the study of 589 COVID-19 CT images of 182 patients, we found that the total lesion CT score proposed by others only considers the area of involvement of the lesions, but not the nature of the lesion [4, 6, 8, 20–22], which may lead to delays of imaging evaluation in clinical practice [19]. Therefore, according to the nature and area of the lesions, we first evaluated consolidation, linear opacity, and GGO scores. Second, although the total lesion score peaked during days 9–11, similar to previous reports [6, 8, 9], we found it interesting that the peak of the total lesion score was highest during days 17 and 18, because this is not reported by others. Third, the peak times of the four CT scores were basically consistent during the 10 stages. However, if the interval was extended to 1 week, the peak time of the total CT score lagged behind those of the consolidation and GGO scores, suggesting that a useful scoring system should include comprehensive assessment of the extent and histopathology of the lesion.

The peak times of the total lesion score differ among previous studies [5, 6, 8, 9]. These studies define the last stage of pneumonia as days 14 or 15 after disease onset. However, the average time from illness onset to discharge reported by other investigators is approximately 28 days [23, 24], and more than 12 days after illness onset is a critical period for disease progression [10]. Therefore, we speculate that the staging method of these studies reported the average of the true peak of the total lesion score. Clearly, in our research, the 10-stage curve confirmed our prediction that the total lesion score peaked during days 9–11 as well as on days 17–18. The latter peak corresponds to week 3 of the five-stage curve, while the previous peak was averaged. In addition, the peak time of the consolidation score was earlier than that of the total score of the five-stage change, and the curve of the consolidation score conformed to a quadratic function. Moreover, the decreased time of the total lesion score is later than the improvement time of clinical parameters [19], and greater consolidation may indicate disease progression [25]. Therefore, the consolidation score may reflect the severity of disease more promptly than the total lesion score, although the changes of the two scores may tend to be associated with the increase of the number of stages.

Among the typical features of each stage, here we show that COVID-19 pneumonia was mainly characterized by bilateral, multiple, and ill-defined lesions, with a GGO pattern, located in the posterior and peripheral regions of both lungs, similar to previous findings [5–7, 9]. In the predominant CT pattern of COVID-19 pneumonia, the GGO and linear opacity patterns increased rapidly from week 3 after disease onset. Histologically, GGO represents interstitial mononuclear inflammatory infiltrates and edema [26], while during the absorption stage, the absorption of exudate cells and hyaline membrane in the lung tissue forms other lesions such as consolidation and the crazy-paving pattern, gradually transforming into GGO. Evidence indicates that linear opacity is an organized feature during the late stage of disease [27]. Therefore, good prognosis may be associated with increases in the proportions of the GGO and linear opacity patterns during the later stage of disease. However, the increases in the total score and GGO score during stage 5 (after week 4) may indicate an extension of hospital stay. Furthermore, the proportions of the consolidation pattern and the consolidation score peaked during week 2 after disease onset and gradually decreased, suggesting that the events that occur during week 2 may be critical for disease progression.

In the present study, the changing trends of the proportions of consolidation, GGO, and linear opacity were not completely consistent with the changing trends of their respective scores, suggesting that previous studies [7, 27], based only on the proportion of lesions used to judge the severity of the disease, may have generated unreliable results. Thus, the proportion of lesions and the area involved should therefore be simultaneously considered. Here, pleural thickening and interlobular septal thickening were relatively common CT signs during each stage. The crazy-paving pattern sign was relatively common during the first 2 weeks after illness onset, and pleural effusion appeared during the first 3 weeks.

Obviously, CT plays an important role in controlling the spread of COVID-19. However, CT has some insurmountable shortcomings, such as high cost, exposure to radiation, and their immobile nature, which can be overcome by lung ultrasound (LUS) [28–31]. Coupled with the fact that the lesions of COVID-19 tend to occur in subpleural regions, LUS has been suggested as a potential triage and diagnostic tool for COVID-19 [32]. The latest research showed that LUS was a promising tool for early risk stratification in COVID-19, which may guide patients’ management strategies, as well as resource allocation in case of surge capacity [28, 31].

There were some limitations to our study. First, this was a single-center study, and the results require verification through a multicenter study. Second, the CT scores of this study may not be comparable with the quantitative scores determined using artificial intelligence [33], although visual scores are easier to determine. Finally, only patients with mild COVID-19 pneumonia were included, and the longitudinal CT performance of severe pneumonia must be determined using a larger sample size.

Conclusions

The total lesion score of mild COVID-19 pneumonia peaked 17–18 days after illness onset, and week 2 after onset may be the critical period for disease progression. The consolidation scores may objectively reflect the severity of lung involvement and thus serve as a more accurate diagnostic measure than total lesion scores. The mild COVID-19 pneumonia in each stage was mainly manifested as bilateral, multiple, and ill-defined lesions, with the GGO pattern, and located in the posterior and peripheral areas of both lungs. Moreover, good prognosis may be associated with increases in the proportions of the GGO and linear opacity patterns during the later stage of disease.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and their families for contributing to this work. We thank the frontline medical staff for their hard work and selfless dedication in the face of the pandemic, despite the risk of infection to themselves and their families. They make an important contribution to controlling the spread of this outbreak.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. The Rapid Service Fee was funded by the authors.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Huaping Liu, Shiyong Luo, Youming Zhang, Yuzhu Jiang, Yuting jiang, Yayi Wang, Hailan Li, Chiyao Huang, Shunzhen Zhang, Xili Li, Yiqing Tan and Wei Wang declare that they have no conflicts of interests and no competing interests.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Commission of Wuhan Third Hospital (Approved number KY2020-027), and informed consent was waived in accordance with the guidelines of the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences. The research study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, and its later amendments.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Footnotes

Huaping Liu and Shiyong Luo contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yayi Wang, Email: 1870592197@qq.com.

Yiqing Tan, Email: tanyiqingradiology@163.com.

Wei Wang, Email: wangweiradiology@163.com.

References

- 1.World Health Organization Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. 2020. https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed 7 July 2020.

- 2.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1239–42. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Ai T, Yang Z, Hou H, et al. Correlation of chest CT and RT-PCR testing in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: a report of 1014 cases. Radiology. 2019;2020:200642. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liang T, Liu Z, Wu CC, et al. Evolution of CT findings in patients with mild COVID-19 pneumonia. Eur Radiol. 2020;30(9):4865–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Wang YC, Luo H, Liu S, et al. Dynamic evolution of COVID-19 on chest computed tomography: experience from Jiangsu Province of China. Eur Radiol. 2020. 10.1007/s00330-020-06976-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Zhou S, Zhu T, Wang Y, Xia L. Imaging features and evolution on CT in 100 COVID-19 pneumonia patients in Wuhan, China. Eur Radiol. 2020;30(10):5446–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Shi H, Han X, Jiang N, et al. Radiological findings from 81 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(4):425–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Pan F, Ye T, Sun P, et al. Time course of lung changes on chest CT during recovery from 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia. Radiology. 2019;2020:200370. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, Dong C, Hu Y, et al. Temporal changes of CT findings in 90 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia: a longitudinal study. Radiology. 2020;296(2):E55–E64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Health and Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Diagnosis and treatment guidelines for 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia (version 6). 2020. https://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s7653p/202002/8334a8326dd94d329df351d7da8aefc2.shtml. Accessed 19 Feb 2020.

- 13.World Health Organization. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when COVID-19 is suspected. 2020. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/clinical-management-of-severeacute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected. Accessed 23 Jan 2020.

- 14.Chung M, Bernheim A, Mei X, et al. CT imaging features of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Radiology. 2019;295(1):202–207. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, et al. Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology. 2008;246(3):697–722. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2462070712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ooi GC, Khong PL, Muller NL, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: temporal lung changes at thin-section CT in 30 patients. Radiology. 2004;230(3):836–844. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2303030853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D, et al. A trial of lopinavir-ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(19):1787–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cao Y, Wei J, Zou L, et al. Ruxolitinib in treatment of severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a multicenter, single-blind, randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(1):137–46.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Han X, Cao Y, Jiang N, et al. Novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) progression course in 17 discharged patients: comparison of clinical and thin-section computed tomography features during recovery. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):723–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Li K, Wu J, Wu F, et al. The clinical and chest CT features associated with severe and critical COVID-19 pneumonia. Invest Radiol. 2020;55(6):327–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Zhao W, Zhong Z, Xie X, Yu Q, Liu J. Relation between chest CT findings and clinical conditions of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pneumonia: a multicenter study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020;214(5):1072–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Li K, Fang Y, Li W, et al. CT image visual quantitative evaluation and clinical classification of coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Eur Radiol. 202030(8):4407–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Liang WH, Guan WJ, Li CC, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of hospitalised patients with COVID-19 treated in Hubei (epicentre) and outside Hubei (non-epicentre): a nationwide analysis of China. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(6):2000562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Liu X, Zhou H, Zhou Y, et al. Risk factors associated with disease severity and length of hospital stay in COVID-19 patients. J Infect. 2020;81(1):e95–e97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Song F, Shi N, Shan F, et al. Emerging coronavirus 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Radiology. 2020;295(1):210–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, Peacock SJ, Prescott HC. Pathophysiology, transmission, diagnosis, and treatment of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. 2020;324(8):782–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Bernheim A, Mei X, Huang M, et al. Chest CT findings in coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19): relationship to duration of infection. Radiology. 2020;295(3):200463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Brahier T, Meuwly JY, Pantet O, et al. Lung ultrasonography for risk stratification in patients with COVID-19: a prospective observational cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2020. 10.1093/cid/ciaa1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Cocconcelli E, Biondini D, Giraudo C, et al. clinical features and chest imaging as predictors of intensity of care in patients with COVID-19. J Clin Med. 2020;9(9):E2990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Kalafat E, Yassa M, Koc A, Tug N. Utility of lung ultrasound assessment for probable SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy and universal screening of asymptomatic individuals. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020;56(4):624–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Lichter Y, Topilsky Y, Taieb P, et al. Lung ultrasound predicts clinical course and outcomes in COVID-19 patients. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(10):1873–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Rubin GD, Ryerson CJ, Haramati LB, et al. the role of chest imaging in patient management during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multinational consensus statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2020;296(1):172–180. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu F, Zhang Q, Huang C, et al. CT quantification of pneumonia lesions in early days predicts progression to severe illness in a cohort of COVID-19 patients. Theranostics. 2020;10(12):5613–5622. doi: 10.7150/thno.45985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.