Abstract

Background

A health department survey revealed nearly half employ laboratory-based HIV and HCV testing (LBT) over rapid testing (RT) in nonhospital settings such as drug detoxification centers. LBT has higher sensitivity for acute HIV infection compared to RT but LBT is not point of care and may result in fewer diagnoses due to loss to follow-up before result delivery.

Methods

We conducted a randomized trial comparing real-world case notification of RT (Orasure) vs LBT (HIV Combo Ag/Ab EIA, HCV EIA) for HIV and HCV at a drug detoxification center. Primary outcome was receipt of test results within 2 weeks.

Results

Among 341 individuals screened (11/2016–7/2017), 200 met inclusion criteria; 58% injected drugs and 31% shared needles in the previous 6 months. Of the 200 randomized, 98 received RT and 102 LBT. Among all participants, 0.5% were positive for HIV and 48% for HCV; 96% received test results in the RT arm and 42% in the LBT arm (odds ratio, 28.72; 95% confidence interval, 10.27–80.31). Real-world case notification was 95% and 93% for HIV and HCV RT, respectively, compared to 42% for HIV and HCV LBT.

Conclusions

RT has higher real-world case notification than LBT at drug detoxification centers.

Clinical trials registration: NCT02869776.

Keywords: HIV, hepatitis C, testing, linkage to care, injection drug use, drug treatment

Recent human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) outbreaks in Indiana, Massachusetts, and West Virginia in the United States demonstrated that these infections and concurrent substance use disorders represent a syndemic requiring coordinated approaches for prevention and treatment [1–4]. Detoxification centers are sites of contact between persons who inject drugs (PWID) and the health care delivery system, but they have been understudied as venues for HIV and HCV screening. Furthermore, the most effective approaches to HIV and HCV screening among PWIDs in community-based settings are not known. In an effort to identify acute HIV cases that are more likely to transmit infection, some public health jurisdictions in the United States have shifted away from rapid point-of-care testing, which does not identify acute HIV, to laboratory-based fourth-generation testing, which can diagnose early HIV infections [5]. A recent study of state health departments, including 47 US states and territories, demonstrated that almost one-half of sites surveyed relied on HIV laboratory-based testing [6]. Although laboratory-based fourth-generation testing can diagnose acute HIV infections, it is not performed at the point of care and results are not immediately available. Therefore, the actual potential to identify acute HIV infection using laboratory-based fourth-generation assays may not be realized if individuals fail to receive test results. Rapid HIV antibody testing eliminates 1 step in the continuum of care and allows persons to receive results during a single encounter without having to be contacted days later to learn about test results; however, rapid antibody tests are not capable of identifying acute HIV infection. There is a trade-off, therefore, between HIV fourth-generation laboratory testing and rapid testing. The optimal choice of test modality depends highly on the rate of test result delivery for the fourth-generation laboratory test.

We compared laboratory-based testing (LBT) to rapid testing (RT) for HIV and HCV infections among drug detoxification center patients to assess receipt of test results and subsequent linkage to care.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a single-site randomized trial to compare test result receipt between LBT and RT for HIV and HCV at the Boston Treatment Center (BOSTC), a short-term inpatient drug and alcohol detoxification center located near Boston Medical Center (BMC), a safety net hospital. The average length of stay at BOSTC is 5 days.

Participants

Study participants were recruited from November 2016 to July 2017. Inclusion criteria were the following: (1) age ≥ 18 years; (2) admission to BOSTC with a history of self-reported drug use; (3) willingness to provide locator information including a phone number and contact information for 2 friends or family members; (4) release of medical records form to assess follow-up at BMC clinics; and (5) English-speaking. Persons reporting both HIV and HCV infection and ongoing engagement in care were excluded.

Procedure

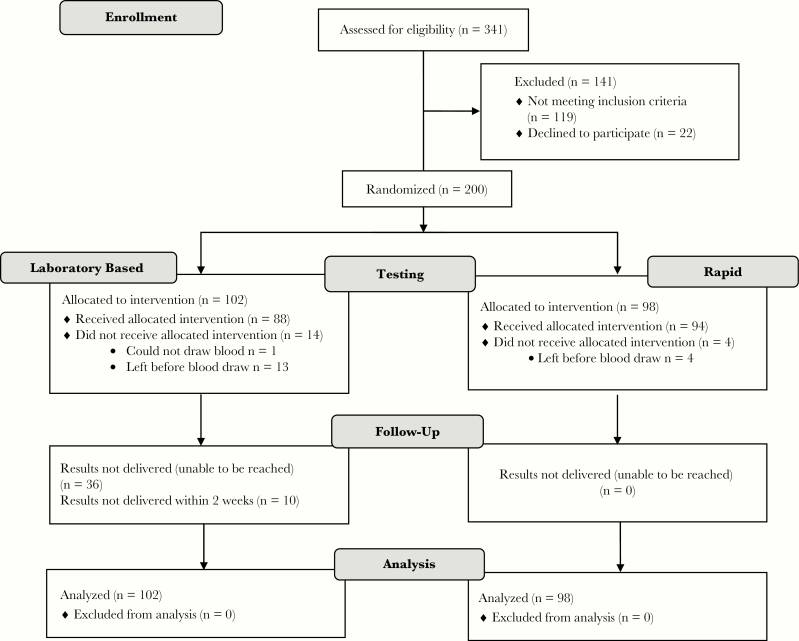

After the research assistant obtained informed consent, participants completed a baseline assessment prior to randomization that included demographics, substance use and psychiatric history, sex and drug use behaviors, and substance use treatment history. Participants were randomized 1:1 to either LBT or RT using a computer-generated randomization scheme (Figure 1). All participants received a $20 gift card.

Figure 1.

Study Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram.

Intervention

A trained counselor/tester performed RT, on-site phlebotomy for LBT, and pre- and posttest counseling. A finger stick blood specimen was obtained for HIV and HCV RT using OraQuick assays (OraSure Technologies) and results were available in 20 minutes. For LBT, venipuncture blood specimens were processed using the HIV Combo Ag/Ab EIA (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and the HCV EIA (Abbott Laboratories). Results were available within 3 days and delivered in person or by phone (up to 3 attempts).

Positive or negative test results were communicated to the participants by the counselor/tester who attempted to facilitate linkage to care at BMC’s Center for Infectious Diseases when indicated. Counselor/testers made an appointment for the participant, provided reminders about the follow-up visit at BMC, and accompanied the participant to the first visit unless the participant declined. The counselor/tester also provided assistance with addressing health insurance barriers to care prior to the medical visit.

We reviewed BMC medical records to determine the proportion of individuals who were referred to BMC and successfully linked to care, and we determined reasons for other health care utilization at BMC during a 4-month period after testing.

The primary study outcome was receipt of HIV and HCV test results within 2 weeks of testing. The secondary outcome was linkage to HIV or HCV care within 4 months of testing for persons who tested positive.

Statistical Analyses

We compared baseline characteristics using χ 2 test for categorical variables. We employed an intention-to-treat design, whereby participants were analyzed according to the group to which they were randomized. We used logistic regression to determine the relationship between test result receipt and test modality. We conducted all analyses using 2-sided tests and a significance level of P < .05. We performed statistical analyses using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Based on the literature, the study was estimated to provide 98% power to detect at least a 27% difference between the 2 strategies [7]. We also estimated the real-world case notification to persons who completed RT and LBT. To do so, we multiplied the diagnostic test sensitivity by the proportion of individuals who received their test results [8–11]. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Boston University Medical Campus and a Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the National Institutes of Health.

RESULTS

BOSTC patients (n = 341) were screened and 200 met inclusion criteria; 102 were randomized to LBT and 98 to RT. Of the 200 randomized participants, 17 were discharged from the BOSTC prior to completing testing (13 LBT, 4 RT). In addition, 7 participants assigned to LBT had hemolyzed samples that could not be tested. Reasons for exclusion among the 141 individuals who did not participate in the study were as follows: testing within the past 6 months, 50% (71/141); refusal to participate in the study, 20% (28/141); unable or unwilling to provide contact information to study staff, 17% (24/141); inability to sign a release form, 5% (7/141); self-report of HIV/ HCV coinfection and already linked to care, 4% (5/141); non-English speaking, 3% (5/141); and younger than 18 years, <1% (1/141). Demographic information was similar between individuals enrolled in the study and those excluded, except that individuals who were excluded were more likely to be Hispanic.

Baseline characteristics were similar between randomization groups except for marital status (Table 1) and use of an opioid overdose reversal drug. The cohort was predominantly male 62%, (124/200) with a mean age of 40 years (SD, 10); 46% (92/200) were white, 26% (51/200) black, 20% (40/200) Hispanic, and 8% other race (17/200) (Table 1). In terms of substances used in the past 12 months, 75% (150/200) used heroin, 20% (40/200) prescription opioids, and 55% (110/200) cocaine or crack. In the 6 months prior to admission, 58% (117/200) reported injection drug use and 31% (63/200) shared needles. When only including the 171 participants who had sex during the 6 months prior to enrollment in the study, 87% (149/171) reported condomless sex and 57% (98/171) had sex with more than 1 partner (Table 1). Over one-quarter of the cohort, 28% (55/200) reported unstable housing. In the 6 months prior to admission, almost one-half of participants (49%, 98/200) had been treated for a drug overdose and the same proportion had been prescribed an opioid overdose reversal drug. Forty-three percent (86/200) reported that family or friends had been prescribed an overdose reversal drug. In addition, 46% (98/200) of the cohort had accessed substance use treatment services in the past 6 months.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of All Participants Tested for HIV and HCV in a Detoxification Center and Stratified by Testing Method (n = 200)

| Characteristic | Overall, No. (%) | Intervention | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory-Based Testing, No. (%) (n = 102) |

Rapid Testing, No. (%) (n = 98) |

P Value | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 124 (62.0) | 68 (66.7) | 56 (57.1) | .17 |

| Female | 76 (38.0) | 34 (33.3) | 42 (42.9) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Black | 51 (25.5) | 27 (26.5) | 24 (24.5) | .96 |

| White | 92 (46.0) | 45 (44.1) | 47 (48.0) | |

| Hispanic | 40 (20.0) | 21 (20.6) | 19 (19.4) | |

| Other | 17 (8.5) | 9 (8.8) | 8 (8.2) | |

| Education | ||||

| < High school | 9 (4.5) | 4 (3.9) | 5 (5.1) | .78 |

| High school | 136 (68.0) | 68 (66.7) | 23 (23.5) | |

| >High school | 55 (27.5) | 30 (29.4) | 25 (25.5) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 11 (5.5) | 7(6.9) | 4(4.1) | .08 |

| Widowed/divorced or separated | 35 (17.5) | 12(11.8) | 23(23.5) | |

| Never married | 154 (77.0) | 83 (81.4) | 71(72.5) | |

| Employment status | ||||

| Full-time | 42 (21.0) | 26 (25.5) | 16 (16.3) | .28 |

| Part-time | 26 (13.0) | 14 (13.7) | 12 (12.2) | |

| Unemployed | 103 (51.5) | 45 (44.1) | 58 (59.2) | |

| Disabled | 25 (12.5) | 15 (14.7) | 10 (10.2) | |

| Other | 4 (2.0) | 2 (2.0) | 2 (2.0) | |

| Unstable housing | ||||

| Yes | 55 (27.5) | 24 (23.5) | 31 (31.6) | .20 |

| No | 145 (72.5) | 78 (76.5) | 67 (68.4) | |

| Prescription for psychiatric disorder in the past 6 mo | ||||

| Yes | 70 (35.0) | 36 (34.7) | 34 (35.3) | .93 |

| No | 130 (65.0) | 66 (65.3) | 64 (64.7) | |

| Substances used in the past 12 mo | ||||

| Sedatives | 59 (29.5) | 31 (30.4) | 28 (28.6) | .77 |

| Tranquilizers | 91 (45.5) | 42 (41.2) | 49 (50.0) | .21 |

| Cocaine/crack | 110 (55.0) | 51 (50.0) | 59 (60.2) | .15 |

| Marijuana | 110 (55.0) | 59 (57.8) | 51 (52.0) | .41 |

| Stimulants | 57 (28.5) | 30 (29.4) | 27 (27.6) | .77 |

| Prescription opioids | 80 (40.0) | 40 (39.2) | 40 (40.8) | .82 |

| Heroin | 159 (79.5) | 79 (77.5) | 80 (81.6) | .46 |

| Sexual history | ||||

| Number of sexual partners | ||||

| No sex | 29 (14.5) | 14 (13.7) | 15 (15.3) | .12 |

| Sex with 1 partner | 73 (36.5) | 45 (66.1) | 28 (28.6) | |

| Sex with 2–3 | 60 (30.0) | 24 (23.5) | 36 (36.7) | |

| Sex with 4 or more | 38 (19.0) | 19 (18.6) | 19 (19.4) | |

| Condom use | ||||

| No sex in the past 6 mo | 29 (14.5) | 14 (13.7) | 15 (15.3) | .57 |

| Condom use at all time | 22 (11.0) | 8 (7.8) | 14 (14.3) | |

| Condom use most of the time | 25 (12.5) | 15 (14.3) | 10 (10.2) | |

| Condom use some of the time | 39 (19.5) | 21 (20.6) | 18 (18.4) | |

| Condom use none of the time | 85 (42.5) | 44 (43.1) | 41 (41.8) | |

| Injection drug use | ||||

| Lifetime | ||||

| Yes | 133 (66.5) | 66 (64.7) | 67 (68.4) | .58 |

| No | 67 (33.5) | 36 (35.3) | 31 (31.6) | |

| Past 6 mo | ||||

| Yes | 117 (58.5) | 59 (57.8) | 58 (59.2) | .85 |

| No | 83 (41.5) | 43 (42.2) | 40 (40.8) | |

| Needles or paraphernalia shared in the past 6 mo | ||||

| Yes | 63 (31.5) | 31 (30.4) | 32 (32.7) | .73 |

| No | 137 (68.5) | 71 (69.6) | 66 (67.4) | |

| Overdose history | ||||

| Ever been treated for an overdose | ||||

| Yes | 98 (49.0) | 44 (43.1) | 54 (55.1) | .09 |

| No | 102 (51.0) | 58 (56.9) | 44 (44.9) | |

| Prescribed a drug to reverse a drug overdose | ||||

| Yes | 98 (49.0) | 47 (46.1) | 51 (52.0) | .40 |

| No | 102 (51.0) | 55 (53.9) | 47 (48.0) | |

| Used a drug to reverse a drug overdose | ||||

| Yes | 94 (47.0) | 41 (40.2) | 53 (54.1) | .05 |

| No | 106 (53.0) | 61 (59.8) | 45 (45.9) | |

| Friends/family prescribed a drug to reverse overdose | ||||

| Yes | 86 (43.0) | 39 (38.2) | 47 (48.0) | .17 |

| No | 114 (57.0) | 63 (61.8) | 51 (52.0) |

Among all participants, 0.5% (1/200) newly tested positive for HIV. Forty-eight percent (96/200) of the cohort included in the study tested positive for HCV. Out of the 96 positive HCV tests, 32 (33%) were newly diagnosed based on self-report at baseline.

All participants who completed testing in the RT arm (n = 94) received their results on the day of testing. In contrast, the median time to result receipt in the LBT arm was 11 days (range, 7–13). Among participants in the LBT arm with information on the mode of test result delivery, approximately two-thirds received their result over the phone. Ninety-six percent (94/98) in the RT arm and 42% (43/102) in the LBT arm received their test results within 2 weeks (odds ratio [OR], 28.72; 95% confidence interval [CI], 10.27–80.31) (Table 2). When comparing result receipt among racial/ethnic groups, black race was negatively associated with successful result receipt compared to white (57% vs 72%, respectively; OR, 0.48; 95% CI, .23–1.01). The real-world case notification based on actual result receipt was 95% and 93% for HIV and HCV RT, respectively, compared to 42% for both HIV and HCV LBT.

Table 2.

Factors Associated With Test Result Receipt Using Logistic Regression Modeling

| Predictor Variable | No. (%) (n = 200) | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Test modality | |||

| Rapid testing | 98 (49) | 28.72 (10.27–80.31) | <.0001 |

| Laboratory-based testing | 102 (51) | Reference | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 124 (62) | 0.83 (.44–1.54) | .54 |

| Female | 76 (38) | Reference | |

| Age | 1.00 (.97–1.03) | .84 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 11 (5) | 0.92 (.26–3.28) | .41 |

| Divorce/separated | 35 (17) | 2.54 (.99–6.49) | .08 |

| Single | 154 (77) | Reference | |

| Unstable housinga,b | 55 (27) | 0.96 (.49–1.88) | .91 |

| High-risk behaviora,c | 157 (78) | 0.72 (.36–1.46) | .36 |

| History of prior testinga,d | 179 (89) | 1.39 (.44–4.43) | .58 |

| Prescription for mental health disorder in the last 6 moa,e | 70 (35) | 1.22 (.66–2.26) | .53 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Black | 51 (26) | 0.48 (.23–1.01) | .04 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 40 (20) | 1.19 (.53–2.63) | .68 |

| Other | 17 (8) | 1.32 (.39–4.43) | .45 |

| White | 92 (46) | Reference |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

aReference group is participants not in this category.

bDefined as living on the street or in an overnight shelter in the past 6 months.

cDefined as having more than 1 sex partner, or lifetime injection drug use, or having sex without using condoms at all times.

dDefined as ever been tested in his/her lifetime.

eDefined as receiving a prescription of a mental health disorder (posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia) in the last 6 months.

One participant had a positive HIV test and 96 participants had a positive HCV test. Chart review revealed that 6% (6/97) of persons with positive tests were successfully linked to care at BMC, defined as having either an HIV or HCV-related visit within 4 months of testing. Three individuals in the RT group, including the individual newly diagnosed with HIV, and 3 in the LBT group were linked to care. The participant with newly diagnosed HIV was seen for an initial intake visit at the HIV clinic on the day of diagnosis and then completed an HIV-focused visit with a physician 1 month after diagnosis. She was initiated on antiretroviral therapy during the HIV-focused visit at 1 month, but did not achieve HIV viral suppression within 4 months of diagnosis. Among the 6 participants diagnosed with HCV who linked to care within 4 months, 1 was initiated on HCV therapy but data on treatment outcome were not available.

Forty-one individuals who did not have a record of HCV-related follow-up utilized other health care services at BMC. In this group, there was an average of 3 visits within 4 months (maximum, 16 visits) and 61% (148/244) of visits were in the emergency department. The remaining visits were in internal medicine and psychiatry clinics. The chief complaint for the majority was related to substance use disorder (substance use, drug detoxification, or drug overdose) or pain. One fatality occurred from a drug overdose in the follow-up period.

Discussion

We found a significant difference in test result receipt between LBT and RT for HIV and HCV upon testing at a drug detoxification center. Individuals randomized to RT compared to LBT were much more likely (96% vs 42%) to receive their results within a 2-week period. In addition, although fourth-generation LBT has the benefit of identifying acute HIV infection, the real-world case notification for LBT was below 50% when accounting for the proportion of individuals who received their results. This finding is important because, as demonstrated in a recent survey, approximately one-half of US state health departments and territories are prioritizing identification of acute HIV cases, and moving away from RT in community-based settings [6]. Our study demonstrated that even in the era of fourth-generation HIV antigen-antibody testing, RT has a distinct advantage over LBT in venues serving hard-to-reach populations.

This study also demonstrated the opportunities and challenges of detoxification centers as venues for HIV and HCV testing. Despite a high rate of result receipt in the RT arm, and many attempts to follow-up with infected individuals, only 6% of those with positive results were linked to care. However, many individuals had multiple interactions with the health care system in the 4 months following testing, mainly in the form of visits to the emergency room. These visits constitute additional opportunities for linkage to care, but doing so would require that results obtained in drug detoxification centers be available to nearby health care facilities. Such linkage of patients to medical care from detoxification centers has been achieved in the past with dedicated effort to attain that goal [12].

In addition to an increased risk of HIV acquisition through injection drug use, there was also a high proportion of participants reporting condomless sex and multiple sexual partners. This illustrates the importance of also testing for co-occurring sexually transmitted infections such as syphilis, gonorrhea, or chlamydia.

Since completing this study, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health reported a large cluster of new HIV infection among injection drug users in the Northeastern Massachusetts cities of Lowell and Lawrence [3]. There were 129 new HIV cases in these 2 cities between 2015 and 2018, according to preliminary data by the Massachusetts Department of Public Health and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This is an increase when compared to an average of 41 cases of HIV linked to injection drug use per year in the whole state of Massachusetts. Employing exclusively rapid HIV testing in the context of an outbreak might miss identifying acutely HIV-infected individuals. Given our finding of high loss to follow-up after laboratory-based HIV testing in an acute detoxification center, however, the high sensitivity of fourth-generation HIV testing for acute HIV might not provide an accurate representation of its usefulness as an HIV screening test among high-risk transient PWIDs. While there may be reasons to continue to employ LBT in detoxification centers for surveillance and early detection of an HIV outbreak among PWIDs, it is important to distinguish surveillance activities, which are for public health benefit, from clinical services that directly impact patient care and prioritize the interests of the individual patient over population outcomes.

Outside of an outbreak situation, the prevalence of acute HIV infection ranges from 0.5 to 4.0 acute HIV cases per 1000 persons tested [13]. Thus, the benefit of finding a very small number of acute HIV cases would likely be outweighed by the high proportion of chronically HIV-infected individuals who would not receive their laboratory-based test results in this transient hard-to-reach population.

Reasons for the lower test result delivery among black participants are unclear. We did not have access to participant’s length of stay at BOSTC, and it is possible that black participants had a shorter stay and were then less likely to be reached once they were discharged from the drug detoxification center. It is also possible that black participants might have been less likely to have a working phone that could have been used to reach them after discharge.

Our preliminary findings on linkage to care within 4 months of testing suggest that in this transient population with a history of substance use disorder, RT likely needs to be enhanced with additional measures to improve movement along the continuum of care. Studies have shown that facilitated referral in the form of patient navigation or hepatitis care coordination with case management, education, and motivational interviewing might help individuals with a history of substance use link to HCV care [14, 15]. In addition, point-of-care HCV RNA testing might improve linkage to care by enabling same-day diagnosis of chronic HCV infection and avoid an additional step for confirmatory testing [15]; however, there are no Food and Drug Administration-approved point-of-care HCV RNA assays at this time.

Finally, our findings also demonstrated the importance of integrating overdose prevention into testing programs for HCV and HIV among PWIDs, especially during the current US opioid epidemic. It is notable that half of participants had been treated for a drug overdose in the past, and that all had been prescribed an opioid overdose reversal drug. It is also encouraging that half of participants’ family or friends had been prescribed an overdose reversal drug. Families may have the potential to play an important role in addressing the current opioid crisis and have been underutilized as resources [16].

There were limitations to our study including the short follow-up time and the lack of information on both medical visits outside of BMC and reasons for low clinical follow-up despite multiple attempts at linkage.

In conclusion, RT was associated with a higher proportion of result receipt than LBT for HIV and HCV at a detoxification center during the opioid epidemic. The real-world case notification for RT and LBT in this population was greater than 90% and less than 50%, respectively. Additional studies are needed to determine reasons for lower test result delivery among black participants and the low linkage to care rate despite the availability of curative therapy for HCV. In addition, testing algorithms are needed to expedite confirmatory testing following positive HIV screening tests in community settings such as drug detoxification centers.

Presented in part: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Boston, Massachusetts, 4–7 March 2018.

Notes

Acknowledgments. The authors thank study participants and our research team, including Samantha Johnson, James Evans, Rachel Peirchert, William Sinton, and Cynthia Wigfall for their contributions to this work.

Disclaimer. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of National Institutes of Health.

Financial support. This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (grant number P30AI042853 Providence/Boston Center for AIDS Research collaborative developmental grant to S. A. A); and the National Institute of Drug Abuse (grant number R25DA035163 pilot award to S. A. A, K23DA044085 to S. A. A, R01DA046527 to B. P. L, and P30DA040500 to B. P. L).

Supplement sponsorship. This supplement is sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1. Conrad C, Bradley HM, Broz D, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Community outbreak of HIV infection linked to injection drug use of oxymorphone–Indiana, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015; 64:443–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zibbell JE, Iqbal K, Patel RC, et al. Increases in hepatitis C virus infection related to injection drug use among persons aged ≤30 years–Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia, 2006–2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015; 64:453–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alpren C, Dawson EL, John B, et al. Opioid use fueling HIV transmission in an urban setting: an outbreak of HIV infection among people who inject drugs-Massachusetts, 2015–2018. Am J Public Health 2020; 110:37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. West Virginia Department of Health and Human Resources Bureau of Public Health. Increase in new HIV infections among persons who inject drugs https://oeps.wv.gov/healthalerts/documents/wv/WVHAN_155.pdf. Accessed 3 September 2019.

- 5. Goodhue T, Kazianis A, Werner BG, et al. 4th generation HIV screening in Massachusetts: a partnership between laboratory and program. J Clin Virol 2013; 58(Suppl 1):e13–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors. 2019 National HIV Prevention Inventory (NHPI) Survey Report https://www.nastad.org/resource/2019-national-hiv-prevention-inventory-survey-report. Accessed 2 July 2019.

- 7. Kowalczyk Mullins TL, Braverman PK, Dorn LD, Kollar LM, Kahn JA. Adolescent preferences for human immunodeficiency virus testing methods and impact of rapid tests on receipt of results. J Adolesc Health 2010; 46:162–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Smith BD, Teshale E, Jewett A, et al. Performance of premarket rapid hepatitis C virus antibody assays in 4 national human immunodeficiency virus behavioral surveillance system sites. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53:780–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bentsen C, McLaughlin L, Mitchell E, et al. Performance evaluation of the Bio-Rad Laboratories GS HIV Combo Ag/Ab EIA, a 4th generation HIV assay for the simultaneous detection of HIV p24 antigen and antibodies to HIV-1 (groups M and O) and HIV-2 in human serum or plasma. J Clin Virol 2011; 52(Suppl 1):S57–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Approval of a new rapid test for HIV antibody. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2002; 51:1051–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Colin C, Lanoir D, Touzet S, Meyaud-Kraemer L, Bailly F, Trepo C; HEPATITIS Group Sensitivity and specificity of third-generation hepatitis C virus antibody detection assays: an analysis of the literature. J Viral Hepat 2001; 8:87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Samet JH, Larson MJ, Horton NJ, Doyle K, Winter M, Saitz R. Linking alcohol- and drug-dependent adults to primary medical care: a randomized controlled trial of a multi-disciplinary health intervention in a detoxification unit. Addiction 2003; 98:509–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cohen MS, Shaw GM, McMichael AJ, Haynes BF. Acute HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:1943–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Masson CL, Delucchi KL, McKnight C, et al. A randomized trial of a hepatitis care coordination model in methadone maintenance treatment. Am J Public Health 2013; 103:e81–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Falade-Nwulia O, Mehta SH, Lasola J, et al. Public health clinic-based hepatitis C testing and linkage to care in Baltimore. J Viral Hepat 2016; 23:366–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ventura AS, Bagley SM. To improve substance use disorder prevention, treatment and recovery: engage the family. J Addict Med 2017; 11:339–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]