Abstract

Introduction

Lagos state remains the epicentre of COVID-19 in Nigeria. We describe the symptoms and signs of the first 2,184 PCR-confirmed COVID-19 patients admitted at COVID-19 treatment centers in Lagos State. We also assessed the relationship between patients’ presenting symptoms, sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and COVID-19 deaths..

Methods

Medical records of PCR-confirmed COVID-19 patients were extracted and analyzed for their symptoms, symptom severity, presence of comorbidities and outcome.

Results

The ages of the patients ranged from 4 days to 98 years with a mean of 43.0(16.0) years. Of the patients who presented with symptoms, cough (19.3%) was the most common presenting symptom. This was followed by fever (13.7%) and difficulty in breathing, (10.9%). The most significant clinical predictor of death was the severity of symptoms and signs at presentation. Difficulty in breathing was the most significant symptom predictor of COVID-19 death (OR:19.26 95% CI 10.95-33.88). The case fatality rate was 4.3%.

Conclusion

Primary care physicians and COVID-19 frontline workers should maintain a high index of suspicion and prioritize the care of patients presenting with these symptoms. Community members should be educated on such predictors and ensure that patients with these symptoms seek care early to reduce the risk of deaths associated with COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, Symptoms, Death, Nigeria

INTRODUCTION

Since the discovery of the index case of COVID-19 in Nigeria in February 2020,(NCDC Coronavirus COVID-19 Microsite, 2020) the spread of the virus has increased exponentially due to community-based human-to-human transmission.(Odukoya et al 2020) Lagos state was the first state to record and manage that case and has remained the epicentre of the pandemic, accounting for 36% of the cases and 22% of deaths as at July 26, 2020. (NCDC 2020, Odukoya et al 2020)

COVID-19 is a novel disease with seemingly variable clinical presentation and progression. In several parts of the world, commonly reported symptoms include fever, dry cough, fatigue, myalgia, headache, sore throat, abdominal pain and diarrhea. (Kim et al 2020; Koh J et al 2020; Lapostolle et al., 2020, Lechien et al., 2020) There is limited research on the symptom profile of COVID-19 patients in Nigeria.

The first and only study in Nigeria that reported the symptomatology of COVID-19 in Lagos State found that admitted early cases of COVID-19 had an average age of 38.1 years, were mostly male and had moderately severe symptoms (66%), while only 16% were asymptomatic.7 The validity of the findings of this study is limited by its small sample size (only 32 patients) and the fact that the data was obtained from a single isolation centre in Lagos state. (Bowale et al 2020)

COVID-19 is a new and rapidly evolving disease. Understanding the symptoms profile of the infection is important in formulating a practicable approach to rapidly identify cases and assess the course of infection. This will improve treatment outcomes and reduce disease transmission and death rates. Assessing the relationship between symptom severity and COVID-19 outcomes may provide some insights into the understanding of the disease and its risk or protective factors. The objective of this study is to use data from a large cohort of the first 2184 patients with PCR confirmed COVID-19 admitted in nine isolation and treatment centres in Lagos State, to describe the pattern of symptoms and predictors of mortality from COVID-19. It is hoped that these findings will fill some critical gaps in research on COVID-19 in Nigeria and provide locally relevant evidence on COVID-19 among Nigerians. The findings will also inform state and national policy and decision-making to improve health outcomes for the rapidly rising number of COVID-19 patients in Nigeria.

METHODS

Study sites

The cases reported in this study were patients admitted at all of the nine treatment centres in Lagos state, Southwest Nigeria, though their places of residence were diverse in the Lagos Metropolis. Treatment centers refer to a place that provides in-patient hospital care specifically for COVID-19 cases.

Study design and population

This was a retrospective study using medical records of 2184 PCR confirmed COVID-19 patients. Laboratory confirmation of COVID-19 was done with naso-oropharyngeal and sputum specimens that tested positive for the SARS-CoV-2 virus using real-time reverse transcription-polymerase-chain-reaction (RT-PCR) assay for SARS-CoV-2 in accordance with the protocol established by the World Health Organisation.(World Health Organization, 2020) Patients were considered negative and discharged after a negative PCR-based SARS-CoV-2 virus test. All patients were treated with Lopinavir-Ritonavir, Vitamin C, Vitamin D and Zinc.

Data extraction and analysis

Data were extracted from electronic medical records of the 2,184 patients as maintained by the case management teams at the hospital or isolation centres. We obtained data on patients age, gender, admitting facility, presenting symptoms, severity of initial presenting symptoms, the presence of co-morbidities and patient’s final outcome (i.e. Dead or Discharged).

Patient’s severity at presentation was based on clinical parameters and the need for oxygen and assisted ventilation. Mild patients are those who were asymptomatic at presentation; Moderate, if patient presented with fever, cough, respiratory rate <30breaths per minutes and peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (spO2) >90% for adults and >92% for children. A patient with grunting respiration, respiratory rate >30 breaths per minute, spO2 < 90% for adults and <92% for children requiring oxygenation was classified as severe while a patient with respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation was classified as critical. Our case definition was adapted from a handbook on clinical experience in China (Yu 2020) STATA version 16 (StataCorp, USA) was used to conduct the data analysis.

Normally distributed continuous variables were presented as means (SD) while categorical variables were presented in tables as frequencies and percentages. To determine the variables associated with COVID-19 deaths, we first of all conducted a bivariate analysis using the student’s T test and the Pearson’s chi square tests for continuous or categorical variables respectively. Thereafter, we conducted two multivariable logistic regression models using variables that were significant at p < 0.2. (Hosmer et al 2013, Lee et al 2014)The first model was designed to determine the socio-demographic and clinical predictors of COVID19 death, while the second model was designed to identify the presenting symptoms most predictive of COVID-19 death among our COVID-19 patients. Variables that were collinear were dropped from the analysis. Results were presented in adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. p values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the Health Research and Ethics Committee of the Lagos State University Teaching Hospital. All patient data was anonymized and handled only by authorized personnel in order to ensure confidentiality.

RESULTS

Patients socio-demographic and clinical presentation

Data from two thousand one hundred and eighty-four (2,184) laboratory confirmed COVID-19 patients presenting in nine treatment facilities in Lagos state. The ages of the patients ranged from 4 days to 98 years with a mean of 43.0(SD16.0) years. More than half (53.2%) were aged between 30 and 50 years. Only 2.9 % were children i.e. less than 18 years of age) while 3.8% were aged 70 years and older. The patients were mostly male (65.8%) and seen in in government owned COVID-19 treatment facilities (97%). More than half (57.5%) were tested within a hospital setting while 42.4% were tested at designated ambulatory centreand thereafter referred to the isolaton and treatment centres.

At presentation, majority were considered to have mild disease, while 6.8% of them were either in severe or critical condition at presentation. Less than a quarter (22.5%) presented with at least one other comorbidity. Of these, 25.4% presented with more than one comorbidity. The cases fatality rate was 4.3%.(Table 1, Table 2 )

Table 1.

Patients age, gender and admitting facility of the COVID-19 patients.

| Variable | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years (N = 2,175) | ||

| <10 | 52 | 2.4 |

| 10-19 | 69 | 3.2 |

| 20-29 | 365 | 16.8 |

| 30-39 | 631 | 29.0 |

| 40-49 | 526 | 24.2 |

| 50-59 | 321 | 14.8 |

| 60-69 | 128 | 5.9 |

| 70-79 | 55 | 2.5 |

| 80 and older | 28 | 1.3 |

| Mean age (SD) | 43.0(16.0) | 43.3-44.7* |

| Gender (N = 2182) | ||

| Female | 746 | 34.2 |

| Male | 1436 | 65.8 |

| Admitting facility (N = 2,184) | ||

| Government-owned | 2118 | 97.0 |

| Privately run | 66 | 3.0 |

*95% Confidence interval

SD-Standard deviation

Table 2.

Patients’ clinical presentation and outcomes of the COVID-19 patients.

| Variable | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Initial presentation (N = 2170) | ||

| Mild | 1251 | 57.7 |

| Moderate | 770 | 35.5 |

| Severe | 107 | 4.9 |

| Critical | 42 | 1.9 |

| The presence of symptoms at presentation (N = 2170) | ||

| Symptomatic | 906 | 41.7 |

| Asymptomatic | 1264 | 58.3 |

| Co-morbidity (N = 2184) | ||

| Yes | 492 | 22.5 |

| No | 1692 | 77.5 |

| Number of co-morbidities (n = 492) | ||

| 1 | 367 | 74.6 |

| 2 | 114 | 23.2 |

| 3 or more | 11 | 2.2 |

| Type of co-morbidities | ||

| Hypertension | 365 | 16.7 |

| Diabetes | 149 | 6.8 |

| Asthma | 50 | 2.3 |

| Cancer | 9 | 0.4 |

| Kidney disease | 14 | 0.6 |

| Sickle cell disease | 7 | 0.3 |

| HIV | 7 | 0.3 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | ||

| Less than 5 | 229 | 12.3 |

| 6-10 | 475 | 25.4 |

| 11-15 | 912 | 48.8 |

| 16-20 | 165 | 8.83 |

| >20 | 88 | 4.71 |

| Outcome (n = 1798) | ||

| Discharged | ||

| Died | 1725 | 95.9 |

| 73 | 4.1 |

Pattern of presenting symptoms among COVID-19 laboratory confirmed cases

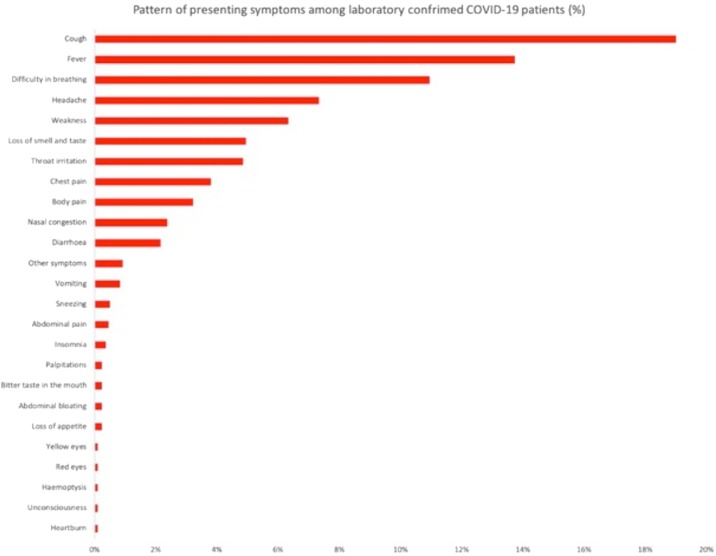

Of the patients who presented with symptoms, cough (19.3%) was the most common presenting symptom. This was followed by fever (13.7%), difficulty in breathing, (10.9%) headaches (7.3%), weakness (6.3%), loss of sense of smell and taste (4.9%), throat irritation (4.9%), chest pain (3.8%), body pains (3.2%), nasal congestion (2.4%) and diarrhea (2.4%). All other symptoms were experienced by less than 1% of the patients.

Fig. 1 displays symptoms profile of patients. We report all symptoms that were presented by at least 2 patients. All other symptoms were presented by only one patient and include: hoarse voice, tooth pain, easy satiety, dry mouth, dark urine, frequent urination, stained mucus, body rash, bleeding, hemiparesis, increased thirst, hiccups, hearing impairment, metallic taste, swollen feet, leg shaking, tingling sensations, anorexia, osteoarthritis, vaginal discharge, weight loss, anxiety, convulsion, ear heaviness, excessive sweating, constipation and body itching

Fig. 1.

XXX.

Socio-demographic and clinical factors associated with COVID-19 deaths

The bivariate analysis showed that more deaths occurred among older patients, males and patients admitted in non-government treatment facilities (p < 0.05). Also, more deaths occurred in patients who were considered as being severe or critical at presentation also had more deaths. More deaths also occurred in persons with existing co-morbidities and this increased with increasing number of co-morbidities. The most significant predictor of death was the severity of initial presentation. Patients presenting in a severe/critical state were 153 times more likely to have died (95%CI:30.74-766.35) while those presenting in a moderate state were 6.33 times (95%CI: 1.13-35.20) more likely to have died, compared to those presenting in as mild cases.

Patients with at least one co-existing morbidity were 2.45 more likely to have died, (95%CI: 1.26-4.76) compared to those without comorbidities. Males were 2.21 times (95%CI: 1.06-4.58) more likely to have died. For every additional year of life, the likelihood of death increased by 1.04 times (95%CI: 1.02-1.06) (Table 3, Table 5 )

Table 3.

Patients age, gender, admitting facility and clinical presentation by final outcome N = 1802

|

Variable |

Recovered n = 1725 Freq.(%) |

Died n = 73 Freq.(%) |

Total N = 1798 Freq.(%) |

Chi-square | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | |||||

| <10 | 48(100) | 0 (0.0) | 48(100.0) | 173.14 | 0.000 |

| 10-19 | 55(98.2) | 1 (1.8) | 56(100.0) | ||

| 20-29 | 294(98.7) | 4 (1.3) | 298(100.0) | ||

| 30-39 | 529(99.1) | 5 (0.9) | 534(100.0) | ||

| 40-49 | 444(98.0) | 9(2.0) | 453(100.0) | ||

| 50-59 | 234(92.5) | 19(7.5) | 253(100.0) | ||

| 60-69 | 83(81.4) | 19(18.6) | 102(100.0) | ||

| 70-79 | 23(69.7) | 10(30.3) | 33(100.0) | ||

| 80 and older | 15(71.4) | 6(28.6) | 21(100.0) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 41.7(15.0) | 61.2(17.1) | 42.5(15.6) | -10.8 | 0.000 |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 611(97.3) | 17 (2.7) | 628(100.0) | 4.54 | 0.033 |

| Male | 1114(95.2) | 56 (4.8) | 1,170(100.0) | ||

| Admitting facility (n = 1802) | |||||

| Government-owned | 1689(96.2) | 66 (3.8) | 1,755(100.0) | 16.9 | 0.00 |

| Privately run | 36(83.7) | 7 (16.3) | 43(100.0) | ||

| The presence of symptoms at presentation | |||||

| Symptomatic | 1092(99.1) | 10(0.9) | 1102(100.0) | 72.64 | 0.000 |

| Asymptomatic | 633(91.0) | 63(9.0) | 696(100.0) |

| Initial presentation | |||||

| Mild | 1,089(99.6) | 4 (0.4) | 1,093(100.0) | 981.177 | 0.000 |

| Moderate | 584(97.3) | 16 (2.7) | 600(100.0) | ||

| Severe | 52(76.5) | 16(23.5) | 68(100.0) | ||

| Critical | 0(0.0) | 37(100.0) | 37(100.0) | 0.000 | |

| Prescence of co-morbidity | |||||

| Yes | 336(86.8) | 51(13.2) | 387(100.0) | 105.26 | 0.000 |

| No | 1389(98.4) | 22(1.6) | 1411(100.0) | ||

| Number of co-morbidities (n = 387) | |||||

| 1 | 270(91.2) | 26(8.8) | 296(100.0) | ||

| 2 | 61(72.6) | 23(27.4) | 84(100.0) | ||

| 3 or more | 5(71.4) | 2(28.6) | 7(100.0) | 21.26 | 0.000 |

Table 5.

Socio-demographic and clinical predictors of COVID-19 outcome (Death) among COVID-19 patients

| Variables | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | 1.04 | 1.02-1.06 | 0.000 |

| Male gender | 2.21 | 1.06-4.58 | 0.034 |

| Is asymptomatic at presentation | 1.16 | 0.31-4.37 | 0.831 |

| Has at least one co -morbidity | 2.45 | 1.26-4.76 | 0.008 |

| Being admitted in a government own facility | 1.99 | 0.66- 6.16 | 0.222 |

| Severity of presenting symptoms | |||

| Mild | Ref | ||

| Moderate | 6.33 | 1.13-35.20 | 0.035 |

| Severe/Critical | 153.47 | 30.74-766.35 | 0.000 |

Presenting symptoms as predictors of COVID-19 deaths

A bivariate analysis showed that deaths occurred more in patients who presented with difficulty in breathing, weakness, loss of appetite, fever, cough, weakness, and hemoptysis. Of the symptoms, difficulty in breathing was the most significant predictor of COVID-19 death (OR:19.26 95% CI 10.95-33.88). Patients who presented with body weakness were 3.04 times more likely to have died, while those presenting with cough were 1.87 times more likely to have died. (Table 4, Table 6 )

Table 4.

Pattern of presenting symptoms by patient’s outcome.

| Symptoms profile | Recovered n = 1725 Freq.(%) |

Died n = 77 Freq.(%) |

Total N = 1802 Freq.(%) |

Chi-square | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fever | 198(89.6) | 23(10.4) | 221(100.0) | 26.06 | 0.000 |

| Cough | 281(90.3) | 31(9.7) | 311(100.0) | 30.13 | 0.000 |

| Vomiting | 14(93.3) | 1(6.7) | 15(100.0) | 0.26 | 0.607 |

| Abdominal pain | 8(100.0) | 0(0.0) | 8(100.0) | 0.34 | 0.560 |

| Loss of appetite | 23(85.2) | 4(14.8) | 27(100.0) | 8.13 | 0.004 |

| Weakness | 81(83.5) | 16(16.5) | 97(100.0) | 40.70 | 0.000 |

| Headache | 114(98.3) | 2(1.7) | 116(100.0) | 1.73 | 0.188 |

| Difficulty in breathing | 126(71.6) | 50(28.4) | 176(100.0) | 296.95 | 0.000 |

| Diarrhoea | 35(89.7) | 4(10.3) | 39(100.0) | 3.92 | 0.047 |

| Chest pain | 68(95.7) | 3(4.2) | 71(100.0) | 0.00 | 0.943 |

| Body pain | 55(100) | 0(0) | 55(100.0) | 2.40 | 0.121 |

| Throat irritation | 82(98.8) | 1(1.2) | 83(100.0) | 1.82 | 0.177 |

| Insomnia | 6(100) | 0(0) | 6(100.0) | 0.25 | 0.614 |

| Sneezing | 11(100) | 0(0) | 11(100.0) | 0.47 | 0.494 |

| Loss of smell and taste | 77(98.7) | 1(1.3) | 78(100.0) | 1.62 | 0.204 |

| Abdominal bloating | 4(100) | 0(0.0) | 4(100.0) | 0.17 | 0.680 |

| Nasal congestion | 39(100.0) | 0(0.0) | 39(100.0) | 1.69 | 0.194 |

| Bitter taste in the mouth | 3(100.0) | 0(0.0) | 3(100.0) | 0.13 | 0.721 |

| Palpitations | 2(100.0) | 0(0.0) | 2(100.0) | 0.08 | 0.771 |

| Heartburn | 2(100.0) | 0(0.0) | 2(100.0) | 0.08 | 0.771 |

| Haemoptysis | 0(0.0) | 2(100.0) | 2(100.0) | 47.31 | 0.000 |

| Red eyes | 2(100.0) | 0(0.0) | 2(100.0) | 0.08 | 0.771 |

| Other symptoms | 13(86.7) | 2(13.3) | 15(100.0) | 3.34 | 0.068 |

Table 6.

Symptoms as a predictor of COVID-19 death controlling for age, gender, co morbidity and admitting facility.

| Variables | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fever | 1.58 | 0.82-3.07 | 0.172 |

| Cough | 1.87 | 1.04-3.37 | 0.038 |

| Weakness | 3.04 | 1.44-6.42 | 0.003 |

| Loss of Appetite | 1.87 | 0.44-7.91 | 0.397 |

| Headache | 0.48 | 0.10-2.32 | 0.367 |

| Difficulty in breathing | 19.26 | 10.95-33.88 | 0.000 |

| Diarrhoea | 1.12 | 0.31-4.02 | 0.861 |

| Throat irritation | 0.15 | 0.02-1.29 | 0.084 |

| Loss of taste/smell | 0.36 | 0.04-3.09 | 0.321 |

| Other symptoms | 1.85 | 0.18-19.40 | 0.609 |

DISCUSSION

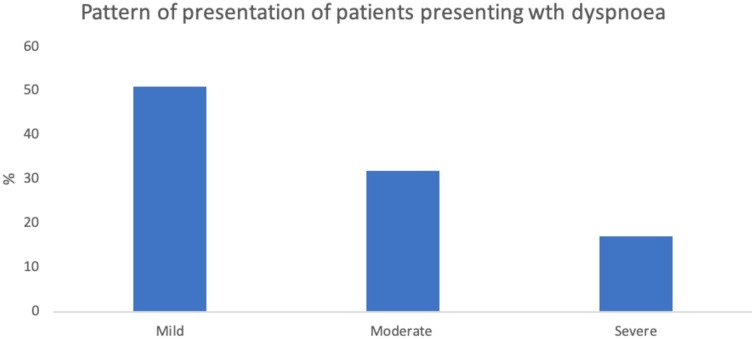

This is the first study that reports the pattern of presenting symptoms and predictors of death among a large cohort of PCR confirmed COVID-19 patients in Nigeria, and one of the first in sub Saharan Africa. COVID-19 patients with dyspnea may have a higher risk of severe and critical disease outcomes. In our study, difficulty in breathing was the most significant predictive symptom of COVID-19 death. Fu et al. observed that there was no statistically significant association between shortness of breath and COVID-19 severity 2== however a systematic review and meta-analysis of risk factors for critical and morbid cases of COVID-19 indicated that shortness of breath/dyspnea was positively associated with the severe illness and death but with a lower odds than ours (OR = 4.16, 95% CI [3.13–5.53]1== Fever on the other hand as reported by Zheng et al was negatively associated with severe illness and death (OR = 0.56, 95% CI [0.38–0.82], P = 0.003) though Fu et al and a systematic review by Shi et al reported no associations similar to our findings. Both systematic reviews however were predominated by studies in China with only one study from the UK and none from Africa.

More than half (58.3%) of patients in our study were asymptomatic and often reluctant to be admitted into isolation units. These patients though asymptomatic, can transmit the virus to others and as a result serve as an important source of hospital and community-based transmission. Two separate reviews of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections report slightly lower figures, ranging from 1.6% to 51.8% in the first review and 40%- 45% of asymptomatic cases in the second review. None of these reviews had patient representation from sub Saharan Africa. (Gao et al., 2020, Oran and Topol, 2020). Another systematic review and meta-analysis of asymptomatic COVID-19 patients showed that up to 40% of patients present with abnormal computed tomography (CT) findings. (Kronbichler et al 2020) Public health messages tend to focus on symptoms as an indicator of COVID-19 disease. Our findings suggest that the focus of public health preventive measures should not be only placed on symptomatic persons, as the majority of COVID-19 cases may be asymptomatic. In addition, public health infection prevention guidelines for both the symptomatic of asymptomatic must be provided to the general public. Asymptomatic COVID-19 infection may be associated with sub-clinical CT lung abnormalities; however, CTs were not conducted for the asymptomatic cases in our study. National guidelines for the management COVID-19 cases should include asymptomatic cases, as they may have undetected sub-clinical abnormalities. (Kronbichler et al., 2020, Singhal, 2020) To reduce the risk of nosocomial transmission, health care workers need to maintain a very high index of suspicion when treating their patients, as the majority may be asymptomatic. The role of asymptomatic carriers in community-based transmission is also important and public health messages designed to emphasize this should be prioritized.

Majority of the symptomatic cases in our study had mild symptoms. This is consistent with findings observed in other places like Beijing, (Tian et al 2020) Hubei province of China (Novel 2020) and South Korea. (Kim et al 2020) Cough, fever and difficulty in breathing were the most common symptoms observed in the patients in this study. Similar findings were observed in France where cough and fever were reported in more than 90% of cases (Lapostolle et al 2020). Body pains, headaches, shortness of breath, ear-nose-throat symptoms and chest pain were also common symptoms a the French aamong patients in France (Lapostolle et al 2020). Similarly, only 3% of patients presented with haemoptysis in the French study, comparable to our study findings. Consistent with the literature, COVID-19 symptoms among the patients in our study are primarily respiratory, ear-nose and throat, gastrointestinal and generalised symptoms. (Lapostolle et al 2020; Lechein et al 2020; Koh et al 2020)

Loss of smell and taste was the most peculiar symptom observed among the COVID-19 patients. However, this occurred in less than 5% of our of the patients in our study. Studies in other parts of the world suggest that such peculiar symptoms may serve as an important clue for the diagnosis of the infection. (Lee et al., 2020, Jan et al., 2020) In Korea and the United States, up to 15.3% of patients presented with acute loss of smell and taste, (Lee et al., 2020, Moein et al., 2020) and this was more common in females and young individuals at the early stages of the infection. (Lee et al 2020) Further research is needed to determine whether loss of taste and smell may also serve as important early signs of COVID-19 among patients in sub Saharan African settings.

Of the symptoms, difficulty in breathing was the most significant predictor of COVID-19 deaths. This is consistent with studies in Wuhan, Guangzhou and Italy (Wang et al., 2020, Liang et al., 2020; De Vito A 2020) Also consistent with the literature, increasing age, male gender, and the presence of co-existing morbidities are strong predictors of COVID 19 deaths in Nigeria. (Figliozzi et al., 2020, Galloway et al., 2020; Imam 2020; Du et al 2020)

Late presentation appears to be the most significant predictor of poor outcomes e as patients presenting in severe or critical states were more likely to have died compared to those presenting in mild clinical states. Effective home management of COVID-19 may therefore play a critical role in reducing late presentations and deaths as suggested by McCullough et al. Targeted and consistent public sensitization on effects of late presentation should be considered in social mobilisation and communication drive to achieve the needed behavioural change in a pandemic as this. Majority of testing in this study was in treatment centers, and not done earlier. This is congruent with the early American experience that a majority of patients waited until becoming very ill to have testing done at the hospital. (McCullough et al 2020) Furthermore, in Lagos, where this study was conducted, poor hospital seeking practices and late presentation occur commonly. (Roberts et al., 2015; Awofeso O et al 2020; Anorlu RI et al 2020; Ugochukwu et al., 2019) Strong public health advisories encouraging people to seek care early. and guidelines for the effective home management of COVID-19 should be instituted to prevent COVID-19 deaths (Fig. 1, Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Pattern of presentation of patients presenting wth dyspnoea

Study strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study in Nigeria and one of the first in sub Saharan Africa to explore the symptomatology and predictors of mortality using data from a large cohort of COVID 19 patients in several treatment facilities. It however has some important limitations and the findings should be interpreted with some caution. First, data on symptoms was obtained by self-report and may be subject to recall or reporting bias. Secondly, inferences on causality cannot be made due to the cross-sectional nature of data extraction. Thirdly, this represents finding from the early stages of a dynamic and rapidly changing pandemic and the evidence provided may change over time or as more data becomes available. Nevertheless, this study provides valuable evidence on the symptom profile and predictors of mortality for COVID-19 at a time where evidence from African countries is sparse.

Conclusion

Respiratory symptoms i.e. cough and difficulty in breathing, as well as fever are the most common presenting symptoms for the COVID-19 patients in our study. Difficulty in breathing is the most important symptom predictive of COVID-19 death. Body weakness and cough are also predictive symptoms of poor outcomes.. Severe symptoms at presentation, which may be brought about by late presentation, is the most significant predictor of death. Males, patients with co-existing morbidities and increasing age have poorer COVID-19 outcomes. Primary care physicians and COVID-19 frontline workers should maintain a high index of suspicion and prioritize the care of patients presenting with these symptoms. Emphasis should be placed on older males with co- morbid conditions. Community members should ensure that patients with these symptoms seek care early to reduce the risk of deaths associated with COVID-19.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Funding

The Lagos State Government funded the study but is not responsible for the design, results and discussions presented in this paper.

Conflict of interest

None.

Uncited references

Anorlu et al., 2004, Awofeso et al., 2018, De Vito et al., 2020, Imam et al., 2020, Lee, 2014, Nigeria Centre for Disease Control, 2020 and McCullough and Arunthamakun (2020).

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to place on record the full support of the Incident Commander for the response to the COVID-19 outbreak in Lagos State, Mr Babajide Sanwo-Olu, Governor of Lagos State and the Deputy Governor Dr Kadiri Hamza by making available resources to conduct researches as part of the counter-measures to the outbreak. Several health workers in the frontline were responsible for caring for the patients and keeping the records.

References

- Anorlu R.I., Orakwue C.O., Oyeneyin L., Abudu O.O. Late presentation of patients with cervical cancer to a tertiary hospital in Lagos: what is responsible? European journal of gynaecological oncology. 2004;25(6):729–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awofeso O., Roberts A.A., Salako O., Balogun L., Okediji P. Prevalence and pattern of late-stage presentation in women with breast and cervical cancers in Lagos University Teaching Hospital. Nigeria. Nigerian Medical Journal: Journal of the Nigeria Medical Association. 2018;59(6):74. doi: 10.4103/nmj.NMJ_112_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowale A., Abayomi A., Idris J., Omilabu S., Abdus-Salam I., Adebayo B., Opawoye F., Finnih-Awokoya O., Zamba E., Abdur-Razzaq H., Erinoso O. Clinical presentation, case management and outcomes for the first 32 COVID-19 patients in Nigeria. The Pan African Medical Journal. 2020;35(24) doi: 10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.35.2.23262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vito A., Geremia N., Fiore V., Princic E., Babudieri S., Madeddu G. Clinical features, laboratory findings and predictors of death in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Sardinia, Italy. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24(14):7861–7868. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202007_22291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du RH, Liang LR, Yang C.Q., Wang W., Cao T.Z., Li M., Guo G.Y., Du J., Zheng C.L., Zhu Q., Hu M. Predictors of mortality for patients with COVID-19 pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2: a prospective cohort study. European Respiratory Journal. 2020;55(5) doi: 10.1183/13993003.00524-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figliozzi S., Masci P.G., Ahmadi N., Tondi L., Koutli E., Aimo A., Stamatelopoulos K., Dimopoulos M.A., LP Caforio A, Georgiopoulos G. Predictors of Adverse Prognosis in Covid‐19: A Systematic Review and Meta‐analysis. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2020 doi: 10.1111/eci.13362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway J.B., Norton S., Barker R.D., Brookes A., Carey I., Clarke B.D., Jina R., Reid C., Russell M.D., Sneep R., Sugarman L. A clinical risk score to identify patients with COVID-19 at high risk of critical care admission or death: an observational cohort study. Journal of Infection. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Z., Xu Y., Sun C., Wang X., Guo Y., Qiu S., Ma K. A systematic review of asymptomatic infections with COVID-19. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer D.W., Lemeshow S., Sturdivant R.X. Wiley; New York: 2013. Applied logistic regression. [Google Scholar]

- Imam Z., Odish F., Gill I., O’Connor D., Armstrong J., Vanood A., Ibironke O., Hanna A., Ranski A., Halalau A. Older age and comorbidity are independent mortality predictors in a large cohort of 1305 COVID‐19 patients in Michigan, United States. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1111/joim.13119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan H., Faisal S., Khan A., Khan S., Usman H., Liaqat R., Shah SA. COVID-19: Review of Epidemiology and Potential Treatments Against 2019 Novel Coronavirus. Discoveries. 2020;8(2) doi: 10.15190/d.2020.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim G.U., Kim M.J., Ra S.H., Lee J., Bae S., Jung J., Kim S.H. Clinical characteristics of asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with mild COVID-19. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh J., Shah S.U., Chua P.E., Gui H., Pang J. Epidemiological and Clinical Characteristics of Cases During the Early Phase of COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Medicine. 2020;7:295. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronbichler A., Kresse D., Yoon S., Lee K.H., Effenberger M., Shin J.I. Asymptomatic patients as a source of COVID-19 infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapostolle F., Schneider E., Vianu I., Dollet G., Roche B., Berdah J., Michel J., Goix L., Chanzy E., Petrovic T., Adnet F. Clinical features of 1487 COVID-19 patients with outpatient management in the Greater Paris: the COVID-call study. Internal and Emergency Medicine. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lechien J.R., Chiesa‐Estomba C.M., Place S., Van Laethem Y., Cabaraux P., Mat Q., Huet K., Plzak J., Horoi M., Hans S., Barillari M.R. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of 1,420 European patients with mild‐to‐moderate coronavirus disease 2019. Journal of internal medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1111/joim.13089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PH. Should we adjust for a confounder if empirical and theoretical criteria yield contradictory results? A simulation study. Sci Rep. 2014;4:6085. doi: 10.1038/srep06085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y., Min P., Lee S., Kim S.W. Prevalence and duration of acute loss of smell or taste in COVID-19 patients. Journal of Korean medical science. 2020;35(18) doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang W., Liang H., Ou L., Chen B., Chen A., Li C., Li Y., Guan W., Sang L., Lu J., Xu Y. Development and validation of a clinical risk score to predict the occurrence of critical illness in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moein S.T., Hashemian S.M., Mansourafshar B., Khorram‐Tousi A., Tabarsi P., Doty R.L. Smell dysfunction: a biomarker for COVID‐19. InInternational forum of allergy & rhinology. 2020 doi: 10.1002/alr.22587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigeria Centre for Disease Control Coronavirus COVID-19 Microsite [Internet] 2020. https://covid19.ncdc.gov.ng/ Available from:

- Novel CP. The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China. Zhonghua liu xing bing xue za zhi= Zhonghua liuxingbingxue zazhi. 2020;41(2):145. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2020.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough P.A., Kelly R.J., Ruocco G., Lerma E., Tumlin J., Wheelan K., Katz N., Lepor N.E., Vijay K., Carter H., Singh B. Pathophysiological basis and rationale for early outpatient treatment of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) Infection. The American journal of medicine. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2020.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough P.A., Arunthamakun J. Disconnect between mcomunity testing and hospitalization for SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infection. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2020;33(3):481. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2020.1762439. Published 2020 May 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odukoya O.O., Adeleke I.A., Jim C.S., Isikekpei B.C., Obiodunukwe C.M., e Lesi F., Osibogun A., Ogunsola F. Evolutionary trends of the COVID-19 epidemic and effectiveness of government interventions in Nigeria: A data-driven analysis. medRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- Oran DP, Topol EJ. Prevalence of Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Narrative Review. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.7326/M20-3012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A.A., Balogun M.R., Sekoni A.O., Inem V.A., Odukoya O.O. Health-seeking preferences of residents of Mushin LGA, Lagos: A survey of preferences for provision of maternal and child health services. Journal of Clinical Sciences. 2015;12(1):9. [Google Scholar]

- Singhal T. A review of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) The Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2020:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s12098-020-03263-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian S., Hu N., Lou J., Chen K., Kang X., Xiang Z., Chen H., Wang D., Liu N., Liu D., Chen G. Characteristics of COVID-19 infection in Beijing. Journal of Infection. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugochukwu U.V., Odukoya O.O., Ajogwu A., Ojewola R. Prostate cancer screening: what do men know, think and do about their risk? exploring the opinions of men in an urban area in Lagos State, Nigeria: a mixed methods survey. Pan African Medical Journal. 2019;34(168) doi: 10.11604/pamj.2019.34.168.20921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., He W., Yu X., Hu D., Bao M., Liu H., Zhou J., Jiang H. Coronavirus disease 2019 in elderly patients: Characteristics and prognostic factors based on 4-week follow-up. Journal of Infection. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization WHO/Europe | Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak - Health care considerations for older people during COVID-19 pandemic [Internet] 2020. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/technical-guidance/health-care-considerations-for-older-people-during-covid-19-pandemic Available from:

- Yu L. 2020. (PDF) Handbook of COVID-19 Prevention and Treatment [Internet] [cited 2020 Jul 27]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339998871_Handbook_of_COVID-19_Prevention_and_Treatment. [Google Scholar]