Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to investigate the incidence, clinical presentation, cardiovascular (CV) complications, and mortality risk of myocardial injury on admission in critically ill intensive care unit (ICU) inpatients with COVID-19.

Design

A single-center, retrospective, observational study.

Setting

A newly built ICU in Tongji hospital (Sino-French new city campus), Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China.

Participants

Seventy-seven critical COVID-19 patients.

Interventions

Patients were divided into a myocardial injury group and nonmyocardial injury group according to the on-admission levels of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I.

Measurements and Main Results

Demographic data, clinical characteristics, laboratory tests, treatment, and clinical outcome were evaluated, stratified by the presence of myocardial injury on admission. Compared with nonmyocardial injury patients, patients with myocardial injury were older (68.4 ± 10.1 v 62.1 ± 13.5 years; p = 0.02), had higher prevalence of underlying CV disease (34.1% v 11.1%; p = 0.02), and in-ICU CV complications (41.5% v 13.9%; p = 0.008), higher Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II scores (20.3 ± 7.3 v 14.4 ± 7.4; p = 0.001), and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment scores (7, interquartile range (IQR) 5-10 v 5, IQR 3-6; p < 0.001). Myocardial injury on admission increased the risk of 28-day mortality (hazard ratio [HR], 2.200; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.29 to 3.74; p = 0.004). Age ≥75 years was another risk factor for mortality (HR, 2.882; 95% CI 1.51-5.50; p = 0.002).

Conclusion

Critically ill patients with COVID-19 had a high risk of CV complications. Myocardial injury on admission may be a common comorbidity and is associated with severity and a high risk of mortality in this population.

Key Words: myocardial injury, novel coronavirus disease, critically ill, cardiovascular complication

THE OUTBREAK of novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 has now become a global health emergency.1 , 2 COVID-19-related pneumonia and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) are the major causes of hospital admission in most patients. However, cardiovascular (CV) complications, including myocardial injury and arrhythmia, have been reported in recent literature.3, 4, 5, 6, 7

The specific incidence of myocardial injury and its association with the mortality in patients with COVID-19 have been demonstrated widely.8, 9, 10 However, investigations focusing on the incidence and mortality risk of myocardial injury in critically ill in-intensive care unit (ICU) patients with COVID-19 still are limited. Therefore, a need exists to characterize CV complications and myocardial injury because an increasing number of countries are facing the difficult situation of a vast number of critically ill patients and increasing cases of CV complications that China encountered from January to April 2020. The authors conducted a retrospective study of data from 77 patients admitted to a newly constructed ICU in Wuhan, compared patients with and without myocardial injury, detailed the relationship of myocardial injury with the survival rate and CV outcomes, and presented the following conclusions: (1) myocardial injury is a common complication in critically ill COVID-19 patients; (2) patients with myocardial injury are more likely to develop adverse events and fatal outcomes during hospitalization; and (3) myocardial injury and advanced age (≥75 years old) are independent risk factors for 28-day in-ICU mortality.

Methods

This single-center, retrospective, observational study enrolled patients admitted to a newly constructed ICU in Tongji Hospital (Sino-French New City Campus), Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China. “Newly constructed” indicates that the quarantine ICU was equipped and modified from a previous general ward within three days and designated to treat critically ill COVID-19 patients. The ICU was staffed with a multidisciplinary team including 185 healthcare providers from Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Beijing, China. Because of the emergency nature of the situation, this ICU lacked sufficient equipment, such as invasive hemodynamic monitors, at the beginning of surgery. The authors retrospectively analyzed patients who were admitted to the ICU from February 4 to March 3, 2020. The confirmation of novel coronavirus infection was defined as a positive result of a throat-swab specimen on a real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction assay. The cutoff of data for investigation of survival status was March 19, 2020. Patients were followed up at least 28 days or died before the cut-off date. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital.

The data analyzed in this study were extracted from electronic medical records and included demographics and baseline characteristics (ie, pre-existing CV diseases [CVD] and CV risk factors), clinical information (ie, vital signs and therapeutic management), laboratory results, and outcomes. Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores were determined on the date of ICU admission. The time from symptom onset to ICU admission, intubation and death also were recorded. Patients were categorized into two groups, including those with or without myocardial injury (myocardial injury and nonmyocardial injury group) on admission according to troponin test results on the first day in the ICU. Covariates of interests were compared between these two groups. Myocardial injury was defined as an elevated cardiac troponin value above the 99th percentile upper reference limit according to the Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction.11 A high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I (hs-cTnI) assay was implemented in this study, and the 99th upper reference limit was 28 ng/L. Prior CVD included a medical history of coronary artery disease (CAD), myocardial infarction, heart failure, and stroke. CV death was defined as a death caused directly by CV complications, such as cardiogenic shock, and occurrence of sudden cardiac arrest and/or fatal ventricular arrhythmia in relatively stable patients. CV complications included in-ICU cardiac arrest, cardiac shock, acute myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, and malignant ventricular arrhythmia. ARDS and acute kidney injury were diagnosed according to the Berlin Definition and Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) clinical practice guidelines, respectively.11 , 12 The authors defined liver abnormalities as any parameter greater than the upper limit of the normal values of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and total bilirubin.

Vasoconstrictive support was applied mostly in patients with shock status (combined with blood pressure lower than 90/60 mmHg or evidence of insufficient perfusion). The venous-venous mode of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation was used in these patients and was performed mainly to improve oxygen supply and attenuate severe hypercarbia under mechanical ventilation.

In the further analysis of risk factors for mortality, the authors conducted a survival study based on age (≥75 and <75 years old), prior CVD history, and myocardial injury on admission. The primary endpoint was 28-day mortality after ICU admission, and the secondary outcome was CV death.

Continuous variables were presented as the mean ± standard deviation for those with a normal distribution or the median and interquartile range () for those with a non-normal distribution. Categorical variables were described by the number (%). Two-sample t test and Mann-Whitney U test were applied to assess the differences in continuous variables between patients with and without myocardial injury. The differences in categorical variables were assessed using χ² test and Fisher's exact test (for small sample sizes). Survival analyses were based on the time from ICU admission to the event. Kaplan-Meier plots and Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to assess survival data. Statistical significance was determined by a two-sided α value less than 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 21.0 software (IBM, Armonk, NY).

Results

Myocardial Injury Is a Common Complication That Intensifies the Disease

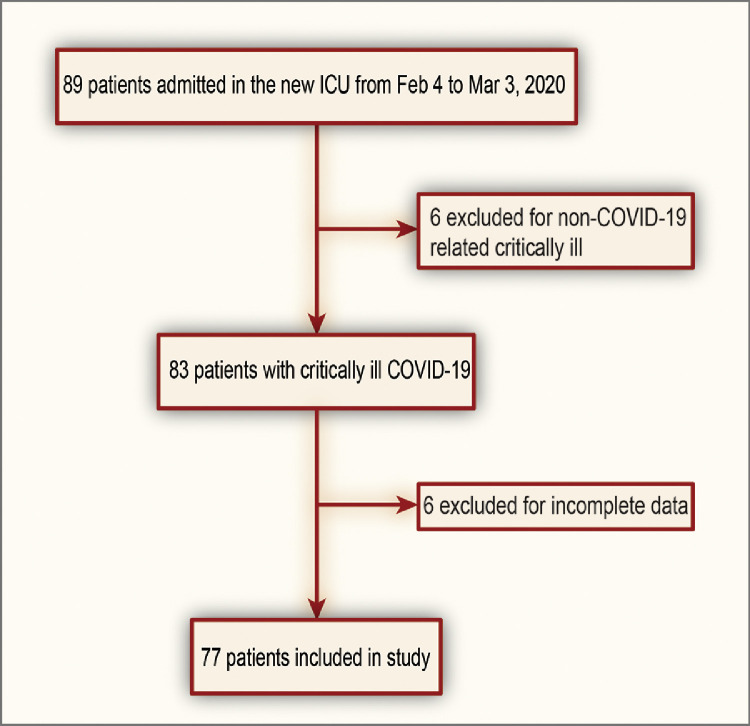

From February 4 to March 3, 2020, 89 reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction test-positive critically ill patients were admitted to the newly constructed ICU; of whom, six patients were considered ineligible because of non-COVID-19-related illness (eg, acute leukemia, intestinal obstruction, gastric cancer). Additionally, six patients with no information on admission hs-cTnI values also were excluded. Finally, 77 patients were enrolled in the study (Fig 1 ).

Fig 1.

Study flow diagram. COVID-19, novel coronavirus disease; ICU, intensive care unit.

The average age of all patients was 65.5 ± 12.2 years old (range, 26-92 y), and 53 patients (68.8%) were men. The mean times from symptom onset to admission and intubation were 17.0 ± 8.3 days and 20.6 ± 16.2 days, respectively. Of these patients, 41 (53.2%) were diagnosed with myocardial injury, and 18 (23.4%) had one or more pre-existing CVDs. Some patients had CV risk factors such as hypertension (39, 50.6%), diabetes (17, 22.1%), and smoking (30, 39.0%). The demographics and baseline characteristics of the studied patients are summarized in Table 1 . Compared with the nonmyocardial injury group, patients with myocardial injury were significantly older (68.4 ± 10.1 y v 62.1 ± 13.5 y; p = 0.022), had more concurrent CVD (34.1% v 11.1%; p = 0.017), including CAD (19.6% v 2.8%; p = 0.032), and were more likely to be smokers (53.6% v 22.2%; p < 0.01). However, the prevalence rates of other CVDs, such as myocardial infarction, heart failure, and stroke, or other CV risk factors, such as hypertension and diabetes, were not significantly different.

Table 1.

Demographics and Baseline Characteristics of Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19

| MI (n = 41) | non-MI (n = 36) | Total (n = 77) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 68.4 ± 10.1 | 62.1 ± 13.5 | 65.5 ± 12.2 | 0.02 |

| Male | 30 (73.2%) | 23 (63.9%) | 53 (68.8%) | 0.38 |

| Prior medical illness | ||||

| CV diseases | 14 (34.1%) | 4 (11.1%) | 18 (23.4%) | 0.02 |

| CAD | 8 (19.6%) | 1 (2.8%) | 9 (11.7%) | 0.03 |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 2 (4.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.6%) | 0.50 |

| HF | 2 (4.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.6%) | 0.50 |

| Stroke | 7 (17.1%) | 3 (8.3%) | 10 (13.0%) | 0.32 |

| COPD | 2 (4.9%) | 1 (2.8%) | 3 (3.9%) | 1.00 |

| CKD | 4 (9.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (5.2%) | 0.12 |

| Malignancy | 1 (2.4%) | 1 (2.8%) | 2 (2.6%) | 1.00 |

| Others | 4 (9.8%) | 3 (8.3%) | 7 (9.1%) | 1.00 |

| CV risk factors | ||||

| Hypertension | 24 (58.5%) | 15 (41.6%) | 39 (50.6%) | 0.17 |

| Diabetes | 12 (29.2%) | 5 (13.9%) | 17 (22.1%) | 0.11 |

| Smoking | 22 (53.6%) | 8 (22.2%) | 30 (39.0%) | 0.005 |

| Death | ||||

| All-cause death | 35 (85.3%) | 23 (63.9%) | 58 (75.3%) | 0.03 |

| CV death | 6 (14.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (7.8%) | 0.03 |

| Symptom onset to (d) | ||||

| Admission to ICU | 17.2 ± 8.5 | 16.8 ± 8.2 | 17.0 ± 8.3 | 0.81 |

| Intubation | 19.9 ± 14.6 | 21.6 ± 18.1 | 20.6 ± 16.2 | 0.65 |

| Death | 27.8 ± 14.2 | 38.5 ± 15.7 | 32.8 ± 15.8 | 0.02 |

NOTE. p values present the differences between MI and non-MI patients.

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CV, cardiovascular; HF, heart failure; ICU, intensive care unit; MI, myocardial injury.

As summarized in Table 2 , there were no significant differences in vital signs (heart rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure) between the two groups on ICU admission. When two important indices for assessing and predicting ICU performance and ICU mortality, the APACHE II and SOFA scoring systems, were compared, the myocardial injury group had significantly higher scores than the nonmyocardial injury group (APACHE II: 20.3 ± 7.3 v 14.4 ± 7.4, p < 0.01; SOFA: 7 IQR 5-10 v 5 IQR 3-6, p < 0.01, respectively). When complications were considered, a significant difference in CV complications (41.5% v 13.9%; p < 0.01) was observed between the two groups (Table 2). Most patients (75 of 77, 97.4%) had ARDS on admission, and there was no significant difference in acute kidney injury or liver dysfunction between the two groups.

Table 2.

Clinical Characteristics of Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19

| Myocardial Injury (n = 41) | Nonmyocardial injury (n = 36) | Total (n = 77) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| On admission | ||||

| Fever | 16.0 (39.0%) | 19.0 (52.8%) | 35 (45.5%) | 0.23 |

| HR (bpm) | 114.6 ± 20.4 | 108.3 ± 19.0 | 111.6 ± 19.9 | 0.16 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 123.8 ± 24.5 | 128.4 ± 19.3 | 125.9 ± 22.2 | 0.36 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 75.0 ± 14.1 | 77.9 ± 13.7 | 76.4 ± 13.9 | 0.38 |

| RR (times/min) | 29.3 ± 8.6 | 27.8 ± 7.6 | 28.6 ± 8.1 | 0.43 |

| Intubated | 10 (24.4%) | 8 (22.2%) | 18 (23.1%) | 0.82 |

| APACHE II score | 20.3 ± 7.3 | 14.4 ± 7.4 | 17.5 ± 7.9 | 0.001 |

| SOFA score* | 7.0 (5.0-10.0) | 5.0 (3.0-6.0) | 6.0 (4.0-8.0) | <0.001 |

| Complications | ||||

| CV complications | 17 (41.5%) | 5 (13.9%) | 22 (28.6%) | 0.008 |

| Arrythmia | 14 (34.1%) | 5 (13.9%) | 19 (24.7%) | 0.04 |

| Cardiac shock | 3 (7.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (3.9%) | 0.24 |

| ARDS | 41 (100%) | 34 (94.4%) | 75 (97.4%) | 0.22 |

| AKI | 15 (36.6%) | 10 (27.8%) | 25 (32.5%) | 0.41 |

| Live dysfunction | 7 (17.1%) | 10 (27.8%) | 17 (22.1%) | 0.26 |

| Acromelic gangrene | 4 (9.8%) | 5 (13.9%) | 9 (11.7%) | 0.73 |

| In-ICU oxygen therapy | ||||

| High flow nasal cannula | 11 (25.8%) | 12 (33.3%) | 23 (29.9%) | 0.54 |

| Noninvasive mechanical ventilation | 13 (31.7%) | 9 (25%) | 22 (28.5%) | 0.52 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 33 (80.5%) | 31 (86.1%) | 64 (83.1%) | 0.51 |

| Prone position ventilation | 12 (29.3%) | 16 (44.4%) | 28 (36.4%) | 0.17 |

| Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation | 2 (4.9%) | 3 (8.3%) | 5 (6.5%) | 0.66 |

| Blood purification therapy | 9 (22.0%) | 6 (16.7%) | 15 (19.5%) | 0.56 |

| Other in-ICU treatment | ||||

| Antiviral agents | 25 (61.0%) | 29 (80.6%) | 54 (70.1%) | 0.06 |

| Antibacterial agents | 28 (68.3%) | 24 (66.7%) | 52 (67.5%) | 0.88 |

| Immunoglobulin | 28 (68.3%) | 29 (80.6%) | 57 (74.0%) | 0.22 |

| Glucocorticoids | 30 (73.1%) | 32 (88.9%) | 62 (80.5%) | 0.08 |

| Vasoconstrictive agents | 31 (75.6%) | 25 (69.4%) | 56 (72.7%) | 0.54 |

| Anticoagulation agents | 16 (39.0%) | 25 (69.4%) | 41 (53.2%) | 0.008 |

| Tocilizumab | 2 (4.90%) | 5 (13.9%) | 7 (9.1%) | 0.17 |

NOTE. p values present the differences between myocardial injury and nonmyocardial patients.

Abbreviations: AKI, acute kidney injury; APACHE II, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HR, heart rate; RR, respiratory rate; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Non-normal distribution.

The admission laboratory findings revealed that patients with myocardial injury had a significantly lower platelet count, longer prothrombin time, higher N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide and D-dimer levels, and reduced renal function according to higher serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels compared with the nonmyocardial injury patients (Table 3 ). There was no significant difference in life support therapy, including in-ICU oxygen therapy, intubation rate, vasoconstrictive agents, and blood purification therapy, between the groups. Similar in-ICU usage of antiviral and/or antibacterial agents, immunoglobulin, and glucocorticoids was observed. The only significant difference in therapy was that more nonmyocardial injury patients received anticoagulation therapy than myocardial injury patients (69.4% v 39.0%, p < 0.01) (Table 2).

Table 3.

Laboratory Tests of COVID-19 Patients

| Normal Range | Myocardial Injury (n = 41) | Nonmyocardial injury (n = 36) | Total (n = 77) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White blood count, × 109/L | 3.5-9.5 | 12.4 ± 5.3 | 12.2 ± 7.4 | 12.3 ± 6.4 | 0.89 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 40.0-75.0 | 89.9 ± 7.1 | 86.5 ± 9.1 | 88.3 ± 8.2 | 0.07 |

| Lymphocytes, × 109/L | 1.1-3.2 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0. 7 ± 0.4 | 0.6 ± 0.4 | 0.12 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 130.0-175.0 | 121.5 ± 20.6 | 123.0 ± 20.1 | 122.2 ± 20.3 | 0.75 |

| Platelets, × 109/L | 125.0-350.0 | 152.7 ± 83.9 | 200.0 ± 100.8 | 174.9 ± 94.6 | 0.03 |

| ALT*, U/L | ≤41.0 | 31.0 (19.0-45.0) | 28.0 (22.0-39.5) | 29 (20.0-45.0) | 0.96 |

| Total bilirubin*, μmol/L | ≤26.0 | 12.8 (8.8-19.2) | 11.9 (8.2-18.4) | 12.8 (8.6-18.9) | 0.54 |

| Albumin g/L | 35.0-52.0 | 28.2 ± 4.1 | 30.1 ± 5.9 | 29.1 ± 5.0 | 0.11 |

| Creatinine*, μmol/L | 59.0-104.0 | 88.0 (73.0-124.0) | 65.5 (47.5-86.0) | 80.0 (58.0-106.0) | <0.001 |

| BUN*, mmol/L | 3.6-9.5 | 10.5 (7.1-18.3) | 7 (5.4-9.6) | 8.3 (6.3-13.1) | 0.002 |

| Serum sodium, mmol/L | 136.0-145.0 | 145.0 ± 9.2 | 139.8 ± 6.6 | 142.6 ± 8.43 | 0.006 |

| Serum potassium, mmol/L | 3.5-5.1 | 4.6 ± 0.8 | 4.4 ± 1.0 | 4.5 ± 0.9 | 0.52 |

| hsCRP, mg/L | <1.0 | 122.3 ± 75.6 | 79.2 ± 64.6 | 102.8 ± 73.5 | 0.22 |

| PT*, s | 11.5-14.5 | 17.2 (15.6-18.2) | 15.2 (13.5-16.5) | 16.1 (15.0-17.6) | 0.001 |

| APTT*, s | 29.0-42.0 | 42.1 (38.2-46.8) | 41.5 (37.2-45) | 41.7 (37.3-45.3) | 0.50 |

| INR* | 0.8-1.2 | 1.4 (1.2-1.5) | 1.2 (1.1-1.3). | 1.3 (1.2-1.4) | <0.001 |

| Fibrinogen, g/L | 2.0-4.0 | 4.5 (0.7-8.4) | 4.6 (2.7-6.5) | 4.6 (3.1-1.5) | 0.97 |

| D-dimer*, mg/L | <0.5 | 21 (6.5-21.0) | 4.0 (2.0-21.0) | 13.5 (3.20-21.0) | 0.004 |

| Hs-cTnI*, ng/L | ≤34.2 | 312.8 (130.5-910.0) | 11.6 (4.9-19.2) | 51.4 (12.1-361.6) | <0.001 |

| NT-proBNP*, ng/L | <241.0 | 2251.0 (776.0-4537.0) | 407.0 (112.8-858.0) | 852.0 (269.0-2894.0) | <0.001 |

NOTE. p values present the differences between myocardial injury and nonmyocardial injury patients.

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; hs-cTnI, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I; INR, international normalized ratio; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; PT, prothrombin time.

Non-normal distribution.

Patients With Myocardial Injury Had Higher Mortality Than Those Without Myocardial Injury

When survival outcomes were summarized, 58 (75.3%) patients had died within 28 days of ICU admission, including six (7.8%) patients who died from CV causes. As indicated in Table 1, the patients with myocardial injury had significantly higher rates of all-cause death and CV death than nonmyocardial injury patients (85.3% v 63.9%, p = 0.029 and 14.6% v 0%, p = 0.027, respectively). Although the durations from symptom onset to ICU admission and intubation were similar in these two groups, the duration from symptom onset to death in patients with myocardial injury was significantly shorter than that of nonmyocardial injury patients (27.8 ± 14.2 v 38.5 ± 15.7 days, p = 0.022).

Myocardial Injury and Advanced Age are Independent Risk Factors for Mortality

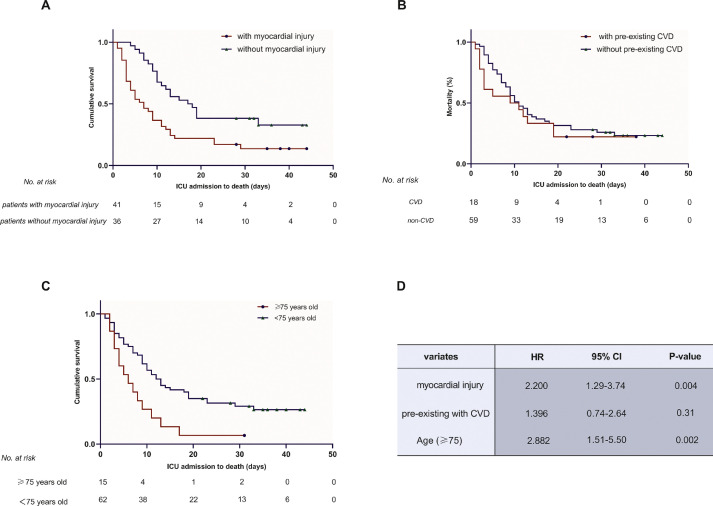

The authors conducted Cox regression analyses to compare survival between patients ≥75 years and those <75 years, with or without admission myocardial injury and pre-existing CVD. Adjusted variates included smoking history, creatinine levels greater than 104 μmol/L (normal limitation), D-dimer levels greater than 13.5 mg/L (median level), and N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide levels greater than 852 ng/L (median level). The older patients had a higher risk of all-cause death (HR, 2.882; 95% CI 1.51-5.50; p = 0.002) than patients <75 years (Fig 2 , A). Consistently, the in-ICU cumulative survival curve of myocardial injury patients was significantly lower than that of nonmyocardial injury patients (HR, 2.200; 95% CI 1.29-3.74; p = 0.004) (Fig 2, B). However, no significant difference was observed in survival between patients with or without pre-existing CVD (HR, 1.396; 95% CI 0.74-2.64; p = 0.31) (Fig 2, C).

Fig 2.

Kaplan-Meier plots for the survival time (ICU admission to death) of patients with myocardial injury (A), pre-existing CVD (B), and advanced age (≥75 years) (C). The occurrence of myocardial injury and advanced age were shown to significantly reduce the survival time in critically ill patients with COVID-2019, as shown in (A) and (C). (B) Revealed that patients with pre-existing CVD did not show a significant difference from those without pre-existing CVD. (D) Shows the HR, 95% CI, and p values after adjusting for smoking history, creatinine levels greater than 104 μmol/L (normal limit), D-dimer levels greater than 13.5 mg/L (median level), and NT-proBNP levels greater than 852 ng/L (median level) in Cox regression models. CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovascular disease; HR, hazard ratio; ICU, intensive care unit.

Discussion

In this study, the authors reported 77 critically ill patients with confirmed novel coronavirus infection in a newly constructed ICU in Wuhan, China. The mean time from symptom onset to ICU admission was 17 days. Most patients had developed severe COVID-19 pneumonia, 75 patients (97.4%) had ARDS, and 64 patients (83.1%) received invasive ventilation.

Elevated hs-cTnI or myocardial injury is well-recognized as a primary complication contributing to increased respiratory syndrome severity and total mortality in patients infected with COVID-19,13, 14, 15, 16 especially in critically ill patients.17 Several studies have indicated that myocardial injury occurrence was a predictor for disease progression, as more than 80% of myocardial injury patients infected with novel coronavirus developed critical illness.3 , 6 This speculation was documented by this study, as the APCHE II and SOFA scores of the myocardial injury patients were significantly higher than those of patients without myocardial injury. Additionally, the authors further compared the mortality and time from ICU admission to death between the myocardial injury and nonmyocardial injury patients, which suggested the predictive value of coexisting myocardial injury on admission as a high-risk factor in critically ill patients with COVID-19 in this study. However, serum troponin level elevation should be interpreted carefully by specialized physicians because of its high sensitivity. Various noncardiovascular factors, such as fever with rapid heart rate, electrolyte disorder, and kidney dysfunction, may contribute to troponin level elevation.18 , 19

In critical patients, myocardial injury results from various clinical mechanisms that may include severe hypoxia, insufficient perfusion, systemic inflammation, and coagulation dysfunctions.18, 19, 20 There was no evidence of acute coronary syndrome or coronary artery-related CV events as the major cause of elevated troponin based on electrocardiography and echocardiography findings. In the authors’ patients, severe hypoxia was suggested as the major cause of myocardial injury, as most had rapid progression of dyspnea, with an oxygenation index (PaO2/FIO2) <200, and more than 95% (including all myocardial injury patients) developed ARDS. Moreover, although 18 patients were intubated and sedated before being sent to the ICU, the mean baseline respiratory rate still exceeded 28 times per minute, suggesting the wide occurrence of dyspnea in the authors’ patients. Additionally, 14 patients received vasoconstrictive agents on the first day of admission, indicating a prevalence of shock or insufficient peripheral perfusion. The imbalance of increased cardiac metabolic demand and decreased blood perfusion/oxygen supply may contribute to myocardial injury and dysfunction.21 A high prevalence of coagulation disequilibrium also was observed closely in the authors’ patients, especially in those with myocardial injury (higher D-dimer levels and longer prothrombin time). Anticoagulation therapies, such as low-molecular-weight heparin or unfractionated heparin were empirically prescribed. These therapies seemed to be effective for restoring coagulation abnormalities and coagulopathy, which might potentially benefit the prognosis. Additionally, a high systemic inflammatory burden was demonstrated to be positively associated with myocardial injury in critically ill patients with COVID-19.22 In this study, anti-inflammation therapies, such as glucocorticoids or tocilizumab, were used in some patients, and the authors’ found that inflammatory cytokine levels were decreased. However, related clinical investigations were not performed in this study. Concrete clinical values for anticoagulation and anti-inflammation therapies in critical patients with COVID-19 should be explored in further studies.

Age and pre-existing CVD have been associated with higher mortality in critically ill patients with viral infection.23, 24, 25 Older patients may have more comorbidities (eg, CAD, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes) and a higher rate of CV complications. In fact, no patients older than 80 had survived at the end of this study. However, this does not mean that young adults will not develop critical illness. The youngest patient in the authors’ ICU with invasive mechanical ventilation was 26 years, and two more patients in their thirties were admitted. The youngest death was 47 years old in the authors’ study. This study verified that COVID-19 patients with myocardial injury had a higher prevalence of prior CVD. No significant difference in survival rate was noted between patients with or without pre-existing CVD. The authors suspect that the extremely high mortality might partially conceal the contribution of previous CVD to death. Thus, this study cannot exclude the risk of pre-existing CVD in mildly or moderately ill patients with COVID-19 (patients with respiratory symptoms [fever, cough, etc] and/or manifestations of pneumonia in imaging examinations). In this study, the prevalence of pre-existing CVD in patients with myocardial injury was higher than that in patients without myocardial injury, but the prevalence of myocardial injury in patients with prior CVD was not explored. Whether pre-existing CVD increases the incidence of myocardial injury in COVID-19 patients requires further investigation.

There was no direct evidence indicating that COVID-19-related viral myocarditis was a major cause of myocardial injury and death in this study. In the authors’ previous echocardiography study, although several presentations of cardiac dysfunction (eg, pericardial effusion, increased left ventricular [LV] mass index, decreased LV stroke volume index, and impaired right ventricle systolic function) were general features of critical patients, LV systolic dysfunction (such as decreased LV ejection fraction [LVEF] or newly diagnosed abnormal ventricular wall movement) was not common.26 There were only four cases of reduced LVEF, including two related to prior myocardial infarction/ischemia, one patient with hypothermia, and one patient with unconfirmed dilated cardiomyopathy. As for the electrocardiography presentations, sinus tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, ventricular tachyarrhythmias, and nonspecific ST-T changes commonly were found in these patients, but no indications for fulminant COVID-19-related myocarditis were found. The authors do not have cardiac magnetic resonance images because this procedure was not applicable for these quarantined critically ill patients. Therefore, viral myocarditis also was not presented in pathology studies. In a report of three autopsies of COVID-19 patients, no pathologic findings indicated viral myocarditis, and the nucleic acid tests for the 2019 novel coronavirus were negative in heart tissue, although mild infiltration of lymphocytes, monocytes and neutrophils, and necrosis of cardiomyocytes were observed.27 Similar results also were reported by Xu et al. who found that novel coronavirus infection might not directly impair the heart tissue in another autopsy report, as they found a few interstitial mononuclear inflammatory infiltrates without other substantial damage in the myocardial tissue.28 The authors have close communication with the pathologists and are expecting further results of autopsies including several of the authors’ patients.29

The prevalence of admission myocardial injury was considered as an increased risk of 28-day mortality in this study, but it was not likely to be the cause of death. The authors considered hs-cTnI elevation on admission as a biomarker of risk. The authors carefully investigated the six patients with cardiovascular death, and they all had myocardial injury. Two patients with prior myocardial infarction (without revascularization) had sudden cardiac death, which was considered as coronary thrombosis events. Two cases of fatal ventricular fibrillation were reexamined and found to have underlying hypokalemia during urgent intubation or deep vein catheterization. One cardiac arrest was related to hyperkalemia (7.2 mmol/L). Only one patient had troponin elevation, cardiac shock without evidence of sepsis or respiratory failure, significantly reduced LVEF, and four-chamber enlargements; however, the authors did not exclude the prior history of dilated cardiomyopathy.

Conclusion

This study focused on critically ill patients with COVID-19 and found that myocardial injury was a common complication and indicative of a poor prognosis in these patients. Furthermore, advanced age also was associated positively with high mortality. Regarding the pathogenesis, the critical status of multiorgan failure, or high systemic inflammatory burden partially may explain the onset of myocardial injury. Evidence for viral myocarditis currently is lacking. It is necessary to pay increased attention to myocardial injury during treatment of critically ill patients with COVID-19.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not for profit sectors.

References

- 1.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang X., Yu Y., Xu J., et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonow R.O., Fonarow G.C., O'Gara P.T., et al. Association of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) with myocardial injury and mortality. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:751–753. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi S., Qin M., Shen B., et al. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:802–810. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo T., Fan Y., Chen M., et al. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:811–818. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ranieri V.M., Rubenfeld G.D., Thompson B.T., et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: The Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–2533. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khwaja A. KDIGO clinical practice guidelines for acute kidney injury. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;120:c179–c184. doi: 10.1159/000339789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thygesen K., Alpert J.S., Jaffe A.S., et al. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2231–2264. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peiris J.S., Chu C.M., Cheng V.C., et al. Clinical progression and viral load in a community outbreak of coronavirus-associated SARS pneumonia: A prospective study. Lancet. 2003;361:1767–1772. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13412-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li S.S., Cheng C.W., Fu C.L., et al. Left ventricular performance in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome: A 30-day echocardiographic follow-up study. Circulation. 2003;108:1798–1803. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000094737.21775.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu C.M., Wong R.S., Wu E.B., et al. Cardiovascular complications of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82:140–144. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2005.037515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Abdely H.M., Midgley C.M., Alkhamis A.M., et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection dynamics and antibody responses among clinically diverse patients, Saudi Arabia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019;25:753–766. doi: 10.3201/eid2504.181595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim W., Qushmaq I., Cook D.J., et al. Elevated troponin and myocardial infarction in the intensive care unit: A prospective study. Crit Care. 2005;9:R636–R644. doi: 10.1186/cc3816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noble J.S., Reid A.M., Jordan L.V., et al. Troponin I and myocardial injury in the ICU. Br J Anaesth. 1999;82:41–46. doi: 10.1093/bja/82.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Randhawa V.K., Grunau B.E., Debicki D.B., et al. Cardiac intensive care unit management of patients after cardiac arrest: Now the real work begins. Can J Cardiol. 2018;34:156–167. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2017.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiong T.Y., Redwood S., Prendergast B., et al. Coronaviruses and the cardiovascular system: Acute and long-term implications. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1798–1800. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song Y., Gao P., Ran T., et al. High inflammatory burden: A potential cause of myocardial injury in critically ill patients with COVID-19. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7:128. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2020.00128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J., Xu H., Yang X., et al. Cardiac complications associated with the influenza viruses A subtype H7N9 or pandemic H1N1 in critically ill patients under intensive care. Braz J Infect Dis. 2017;21:12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong P.L., Sii H.L., P'Ng C K., et al. The effects of age on clinical characteristics, hospitalization and mortality of patients with influenza-related illness at a tertiary care centre in Malaysia. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2020;14:286–293. doi: 10.1111/irv.12691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Y., Xie J., Gao P., et al. Swollen heart in COVID-19 patients who progress to critical illness: A perspective from echo-cardiologists [e-pub ahead of print] ESC Heart Fail. 2020 doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12873. Accessed September 25, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yao X.H., Li T.Y., He Z.C., et al. [A pathological report of three COVID-19 cases by minimally invasive autopsies] Zhonghua Bing Li Xue Za Zhi. 2020;49:E009. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112151-20200312-00193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu Z., Shi L., Wang Y., et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:420–422. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inciardi R.M., Lupi L., Zaccone G., et al. Cardiac involvement in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:819–824. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]