Abstract

Objective

Domestic violence is a hidden epidemic. We used a two-question screening tool to explore the prevalence of domestic violence among gynaecological outpatients. We also retrospectively assessed whether there was a change in the prevalence rate of self-reported violence after the launch of the #MeToo movement.

Study design

Over an 11-month period, all gynaecological first-time visitors to our outpatient clinic were asked two dichotomous questions that screened for domestic violence and examined whether the violence had an ongoing impact on the respondent’s everyday life. We used logistic regression models to assess whether the launch of #MeToo was associated with the answers to these two questions.

Results

Of the 6,957 screened women, 154 (2.2 %) tested positive for domestic violence. Among the screen-positive women, 87 (56.5 %) reported that the violence affected their health and well-being. Of these 87 women, 52.9 % wanted further support and 72.4 % had already contacted psychiatric care. Out of all of the patients, the proportion of screen-positive respondents was 2.3 % before and 2.2 % after #MeToo. We did not detect increased odds of self-reporting domestic violence (odds ratio 0.97, 95 % confidence interval 0.70–1.36) or its ongoing impact on the victim’s everyday life (odds ratio 1.05, 95 % confidence interval 0.53–2.07) after #MeToo.

Conclusions

Our two-question screening tool detected a lower prevalence of domestic violence among gynaecological outpatients than previous reports examining the general population. Our results illustrate the dire challenges in screening for domestic violence that persist even in the post-#MeToo era. Domestic violence remains a highly intimate, stigmatising, and underreported health issue, and systematic measures to screen for and prevent it should be advocated, both in gynaecological patients and the general population.

Keywords: Domestic violence, #MeToo, Physical violence, Screening, Sexual abuse, Social media

Introduction

Domestic violence is a major public health problem that violates human rights. It includes all acts or threats of physical, sexual, or psychological violence by one family member against another [1,2]. Experience of domestic violence has been linked to serious short- and long-term consequences such as depression, post-traumatic stress and other anxiety disorders, sleep difficulties, eating disorders, and suicide attempts [3,4].

Several factors could increase the risk of becoming a victim of domestic violence, including a history of exposure to child maltreatment, witnessing family violence, alcohol abuse, lower level of education, and male controlling behaviour toward their partners. The two root causes of violence against women are gender inequity and harmful norms on the acceptability of violence against women [1,2]. Fundamentally, the problem rests with a behavioural model characterised by controlling and domination [1,2].

In long-lasting and frequent violence, the victim is usually a woman [1]. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), more than 30 % of women worldwide have suffered domestic violence [2]. In agreement, one-fifth of Finnish women report having experienced domestic violence [5]. However, low disclosure rates to authorities remain a problem, as only one-tenth of domestic violence is reported to the police in Finland [5], and sexual assault remains the most widely underreported violent crime in the US [6]. As one possible aid, the social media movement #MeToo has raised hopes that the victims of sexual abuse would come forward. The movement came to wider public knowledge after an initial tweet on October 15, 2017, stating, “If you’ve been sexually harassed or assaulted, write ‘me too’ as a reply to this tweet” [7]. Since then, the movement has continued to battle steadfastly against sexual harassment and violence. #MeToo is still trending on social media and bringing into focus onto the concealed epidemic of domestic violence [8,9].

There are international screening tools for domestic and intimate partner violence [[10], [11], [12], [13]]. The European Union has designated a minimum demand for collected data on reported domestic violence, including the age and gender of the victim and perpetrator and the type of violence used [14].

A systematic review of six randomised controlled trials demonstrated that face-to-face screening does not significantly increase the disclosure of intimate partner violence compared with self-administered written screening [15]. Drawing from this evidence, we designed a questionnaire that could potentially aid the disclosure of violence, with a minimal collection burden and a focus on domestic violence. We assessed the practical usability of this tool and the prevalence rates of violence it obtains. As a result, on June 1, 2017, a two-question screening questionnaire for domestic violence was implemented at Turku University Hospital as an attachment on the back of a health inquiry form that is given to each woman at their initial visit to the gynaecological outpatient clinic. We were also able to retrospectively assess whether the launch of #MeToo had an association with the rates by which violence had been disclosed.

Materials and methods

Patients and screening

This study was a collaboration between the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Turku University Hospital and the Department of Social Research at the University of Turku. A background questionnaire was sent to all first attenders at the gynaecological outpatient clinic at Turku University Hospital to be completed before obtaining the patients’ medical history during the appointment. Starting on June 1, 2017, two dichotomous questions (Table 1 ) were attached to the back of the questionnaire to screen for domestic violence (these questions remain on the form regardless of this study). However, the screening began effectively only starting from July 2017, and as a result, only one patient screened positive in June 2017. All of the analyses were therefore conducted utilising the data collected from July 1, 2017, to May 31, 2018. During this period, a total of 6,957 patients were screened and included in this study.

Table 1.

The two-question screening questionnaire for domestic violence.

| Question 1. Have you been a victim of physical, psychological, and/or sexual abuse, or have you yourself been violent in your domestic or family relationships? (no/yes) |

| If you answered “yes” to the previous question: Question 2. Does the violence affect your health, your well-being, or your ability to cope in your day-to-day life? (no/yes) |

If the patient answered “yes” to both screening questions, a possible need for emergency help was first assessed. If there was no need for immediate action, the patient was asked for permission to be contacted by telephone by a doctor (KK) within two weeks of the visit. Written consent was obtained and the patient was asked to determine a suitable and safe time for the call. A doctor (KK) interviewed the patients by telephone, and further help and treatment were individually tailored if the patient did not already have a psychiatric or other relevant treatment contact. Concise demographic information was gathered for this study, including age, parity, reason for the appointment (that is, diagnosis), and possible current psychiatric care.

Ethics

The Joint Commission on Ethics at the University of Turku and Turku University Hospital approved the study protocol.

Statistical analyses

We used simple logistic regression models to test whether the #MeToo movement was associated with the rates at which gynaecological outpatients reported domestic violence. In the first regression model, the outcome variable was the result of the first screening question, which is outlined in Table 1. A dummy exposure variable indicated whether the screening had been conducted before or after the start of #MeToo. For those who did not screen positive for the first question, the only available covariate data was the month of their outpatient visit. We therefore opted to use the first turn of a month following the initial #MeToo tweet on October 15, 2017, as the movement’s start date in our analyses.

The second regression model included all of the outpatients who screened positive for the first screening question, excluding only those (n = 5) with missing data for the second screening question. The outcome variable was the result of the second screening question, as outlined in Table 1, and the exposure variable was similar to the first regression model.

We conducted the statistical analyses using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Of the 6,957 screened women, 154 (2.2 %) tested positive for having experienced violence. The characteristics of the screen-positive women are presented in Table 2 . Among the screen-positive women, 87 (56.5 %) reported that the violence still negatively affected their health and well-being. Table 3 summarises the characteristics of these 87 women.

Table 2.

Characteristics of gynaecological outpatients (n = 154) who reported having suffered from domestic violence.

| Characteristic | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 39.7 ± 16.0 | |

| Number of pregnancies | 1.9 ± 2.0 | |

| Number of labours | 1.4 ± 1.6 | |

| Ongoing impact of violence | ||

| No | 62 (40.3 %) | |

| Yes | 87 (56.5 %) | |

| Missing data | 5 (3.2 %) | |

| Outpatient visit after October 2017a | ||

| No | 55 (35.7 %) | |

| Yes | 99 (64.3 %) | |

| Missing data | 0 (0.0 %) | |

| Abdominal pain | ||

| No | 90 (58.4 %) | |

| Yes | 63 (40.9 %) | |

| Missing data | 1 (0.6 %) | |

| Patient wanted to be contacted | ||

| No | 68 (44.4 %) | |

| Yes | 64 (41.8 %) | |

| Missing data | 21 (13.7 %) | |

| Already treated for domestic violence | ||

| No | 71 (46.1 %) | |

| Yes | 79 (51.3 %) | |

| Missing data | 4 (2.6 %) | |

| History of drug abuse | ||

| No | 127 (82.5 %) | |

| Yes | 14 (9.1 %) | |

| Missing data | 13 (8.4 %) | |

| Immigrant | ||

| No | 141 (91.6 %) | |

| Yes | 7 (4.5 %) | |

| Missing data | 6 (3.9 %) | |

Values are means ± standard deviations for continuous data and numbers and percentages for categorical data. Data on number of labours were missing for one patient.

The #MeToo movement started on Twitter on October 15, 2017.

Table 3.

Characteristics of outpatients (n = 87) suffering ongoing impact of domestic violence.

| Characteristic | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 39 ± 16.2 | |

| Number of pregnancies | 1.9 ± 2.0 | |

| Number of labours | 1.4 ± 1.5 | |

| Outpatient visit after October 2017a | ||

| No | 30 (34.5 %) | |

| Yes | 57 (65.5 %) | |

| Missing data | 0 (0.0 %) | |

| Abdominal pain | ||

| No | 45 (51.7 %) | |

| Yes | 42 (48.3 %) | |

| Missing data | 0 (0.0 %) | |

| Patient wanted to be contacted | ||

| No | 29 (33.3 %) | |

| Yes | 46 (52.9 %) | |

| Missing data | 12 (13.8 %) | |

| Already treated for domestic violence | ||

| No | 20 (23.0 %) | |

| Yes | 63 (72.4 %) | |

| Missing data | 4 (4.6 %) | |

| History of drug abuse | ||

| No | 74 (85.1 %) | |

| Yes | 8 (9.2 %) | |

| Missing data | 5 (5.7 %) | |

| Perpetrator with history of drug abuse | ||

| No | 10 (11.5 %) | |

| Yes | 19 (21.8 %) | |

| Missing data | 58 (66.7 %) | |

| Immigrant | ||

| No | 81 (93.1 %) | |

| Yes | 4 (4.6 %) | |

| Missing data | 2 (2.3 %) | |

| Perpetrator immigrant | ||

| No | 46 (52.9 %) | |

| Yes | 2 (2.3 %) | |

| Missing data | 39 (44.8 %) | |

| Sexual violence | ||

| No | 24 (27.6 %) | |

| Yes | 25 (28.7 %) | |

| Missing data | 38 (43.7 %) | |

| Physical non-sexual violence | ||

| No | 5 (5.7 %) | |

| Yes | 48 (55.2 %) | |

| Missing data | 34 (39.1 %) | |

| Mental violence | ||

| No | 3 (3.4 %) | |

| Yes | 50 (57.5 %) | |

| Missing data | 34 (39.1 %) | |

| Harassment after break-up | ||

| No | 34 (39.1 %) | |

| Yes | 5 (5.7 %) | |

| Missing data | 48 (55.2 %) | |

| Long-standing and recurrent violence | ||

| No | 2 (2.3 %) | |

| Yes | 48 (55.2 %) | |

| Missing data | 37 (42.5 %) | |

Values are means ± standard deviations for continuous data and numbers and percentages for categorical data.

The #MeToo movement started on Twitter on October 15, 2017.

Among the 154 screen-positive women, the three most frequent outpatient diagnoses were abnormal findings from Pap smear screening, abdominal pain, and medical abortion (Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Ten most frequent diagnoses of gynaecological outpatients (n = 154) who reported having suffered from domestic violence.

| Rank | ICD-10 code | ICD-10 text | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | R87.6 | Abnormal cytological findings in specimens from female genital organs | 24 | 15.6 |

| 2 | R10.3 | Pain localised to other parts of lower abdomen | 16 | 10.4 |

| 3 | O04.9 | Medical abortion: complete or unspecified, without complications | 13 | 8.4 |

| 4 | R10.4 | Other and unspecified abdominal pain | 8 | 5.2 |

| 5 | N92.0 | Excessive and frequent menstruation with regular cycles | 7 | 4.5 |

| 6 | N94.1 | Dyspareunia | 7 | 4.5 |

| 7 | D25.9 | Leiomyoma of uterus, unspecified | 4 | 2.6 |

| 8 | N81.6 | Rectocele | 4 | 2.6 |

| 9 | N92.1 | Excessive and frequent menstruation with irregular cycles | 4 | 2.6 |

| 10 | R32 | Unspecified urinary incontinence | 4 | 2.6 |

The most frequently reported sole perpetrators were ex-husbands (23.0 %) and a family member in childhood (8.0 %). Nearly one in six victims (16.1 %) reported the involvement of many perpetrators (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Breakdown of perpetrators of domestic violence victims.

The victims included in this analysis were gynaecological outpatients who reported that they were suffering the ongoing impact of violence in their everyday lives.

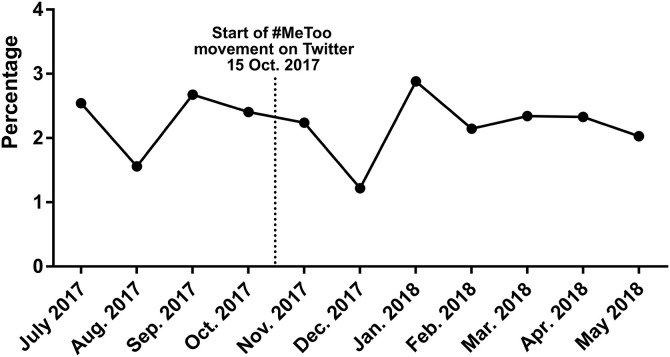

The prevalence of reported violence is presented by outpatient visit month in Fig. 2 , varying from 1.2 to 2.9 % and peaking in January. The monthly average number of screen-positive patients was 14 at our outpatient clinic.

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of self-reported domestic violence by visit month among gynaecological outpatients. Screening for domestic violence was conducted using a questionnaire. Absolute numbers of screen-positive and screen-negative patients are shown below the graph. No., number; pts, patients; screen+, screen-positive; screen-, screen-negative.

Before #MeToo, 55 (2.3 %) of the 2,444 screened patients tested positive for having experienced violence, while after #MeToo, 99 (2.2 %) of the 4,513 examined patients were screen-positive. We did not detect increased odds of reporting domestic violence (odds ratio 0.97, 95 % confidence interval 0.70–1.36) or its ongoing impact on the victim’s everyday life (odds ratio 1.05, 95 % confidence interval 0.53–2.07) after #MeToo (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Effect of #MeToo on prevalence of reported (A) domestic violence and (B) ongoing impact of domestic violence among gynaecological outpatients.

Comments

In our study, only 2.2 % of the gynaecological outpatients reported having experienced violence. We did not detect increased odds of reporting violence or its ongoing impact on the victim’s everyday life after the #MeToo movement.

The prevalence of violence was low in our study compared to the previously reported prevalence estimates in the general population. According to a WHO report, more than 30 % of women worldwide have experienced domestic violence. Finland is considered one of the world’s happiest nations [16], but this success is not echoed in its statistics for the prevalence of reported domestic violence: in Finland, one in five women has reported violence in their present intimate relationship [1]. Although our two-question questionnaire detected a low amount of violence, we believe that such a screening tool could guide patients to identify the concealed trouble of this affliction for the first time in their lives. We suspect that some patients could initially struggle in asking for our aid when completing our health questionnaire.

According to the previous literature, domestic violence should be recognised as a health epidemic, and routine and repeated screenings are needed to increase the potential to identify it, since a woman’s abuse status may change over time [17]. However, during our study, we acknowledged the concerns of our colleagues related to allocating scarce time from the busy general gynaecology outpatient appointments to the screening. The nurses at our clinic were able, for their part, to alleviate this burden by providing further guidance to the screened patients. The serendipitously low number of screen-positive patients also mitigated the strain that this study put on the busy outpatient clinic.

More than one-half of the screen-positive women had had deliveries, indicating that other family members, including children, had likely witnessed the violence. According to prior research, a history of experienced childhood abuse, violence, or maltreatment are severe risk factors for numerous medical and health conditions [[18], [19], [20]]. Toxic stress occurs when a person undergoes significant amounts of stress during their formative years, which may alter the formation of the brain structure and the endocrine and immune systems [20,21]. Victims of childhood violence often experience new victimisation in adult life. However, risk factors for such victimisation are poorly understood [22]. Thus, the suffered violence affects over generations, and the burden of the trauma may be inherited epigenetically within the family [20]. Contrary to the unsatisfactory framework of screening for domestic violence within the adult health sector, there is an effective standard for general health screening in maternity clinic and in child health care in Finland [23].

In the present study, gynaecological diagnoses varied widely among the screen-positive patients, and it was therefore unlikely that we could find predictive value of any singular diagnosis for the risk of domestic violence. Furthermore, individuals across a wide range of age screened positive. These findings underscore the need to screen all patients, regardless of their appointment reason.

Some of the patients conferred the history of violence for the first time in their lives. To increase motivation to screen, it is crucial that clinicians are aware of the various health problems that could be triggered by domestic violence. Wider recognition of these scenarios might improve the effectiveness of health care by enabling clinicians to better understand the origins of a given violence-related health problem. This could reduce the costs related to unnecessary prescriptions, tests, and even surgical interventions and thus lead to better care and treatment [22,24].

We established that many of the positively screened patients already had a contact in psychiatric care. This might indicate that it was easier to report the violence in cases where the barrier of shame had already been broken down. Feelings such as fear, shame, and confusion are present when the victim has eventually identified the problem and is starting to consider sharing the information with a specialist [24,25]. In this setting, it is important that the victim feels secure and is assured that they are not guilty for what has happened.

We found no patients with a need for immediate police or emergency aid. At any rate, the most crucial primary intention of screening should be to avoid severe assaults, as they can be lethal to the victim. In Finland in 2003–2014, there were 302 violent deaths due to domestic violence, and the victim was a woman in 80 % of these cases. In addition to the threat against the spouse, children may also become casualties of tragedy. In 2003–2011, there were 35 familicides in Finland. Fifty-five people died, comprising seven spouses and 48 children [5].

Immigrants comprised less than 5 % of the outpatients suffering from domestic violence in our study. However, it has been estimated that foreigners living in Finland tend to experience violence three times more often than the native population [26]. In our study, methodological and cultural factors could have contributed to the low percentage of immigrants among the screen-positive patients. First, immigrants could have difficulties providing written informed consent in a foreign language. Second, admitting the violence may pose safety risks and fear of uncertainty. Third, violence may be difficult to identify due to cultural differences in what is generally accepted as normal behaviour in intimate relationships and parenting. Notwithstanding, immigrant patients should also be provided appropriate information, which should be conveyed in a culturally sensitive manner [9].

We found that in most cases, the reported perpetrator was the ex-husband. Among other reported perpetrators were a family member in childhood, a member of the religious community, and a neighbour. In addition, school or workplace bullying was mentioned. Many of the women had had many perpetrators. The perpetrator could not be determined in 45 % of the cases, partially because we could not reach all of the screen-positive respondents by telephone after the visit.

As an exploratory observation, we noticed an apparent peak in the prevalence of reported domestic violence in January, which could reflect the holiday season’s influence and would thus corroborate previous research on this subject [27]. The COVID-19 pandemic also had a similar influence on reported family violence in global terms [28].

We did not find an increasing trend in reported domestic violence during the seven months of our screening after #MeToo. After the #MeToo movement initiated, many members of the public who had experienced sexual violence were empowered to come forward with their painful past [29]. Our results did not reflect a similar potency of the #MeToo movement, which illustrates the enormous stigma with the experience of violence even in the post-#MeToo era and the enduring screening challenges. The closer the perpetrator is in the victim’s everyday life, the more difficult it may be to expose the disgraceful family secret.

Our study had limitations. First, to the best of our knowledge, no similar two-question model has been described elsewhere in the literature. Thus, we could not compare our results with other studies. At any rate, we argue that it is important to consider any new instrument that could help improve the sensitive issue of violence during the outpatient visit. We believe that systematic management of this issue by medical staff is pivotal to overcome the barriers of domestic violence screening among outpatients. Similar future studies with a longer study period might corroborate our theory. Second, we encountered difficulties reaching screen-positive patients by telephone after their visit. This underscores the importance of an immediately tailored plan of further help and treatment for a screen-positive patient at the initial appointment. After this study, we developed our own algorithm to provide individually planned immediate help for patients with different backgrounds.

Conclusions

Due to its highly intimate and stigmatising character, domestic violence is difficult to screen with singular questions on a health inquiry form. Even broad social media movements such as #MeToo do not necessarily facilitate screening. Health professionals need more education and skills to raise this sensitive issue, and algorithms for systematic screening and further care must be developed.

Funding information

V. Langén was supported by a grant from the State Research Funding of Turku University Hospital’s expert responsibility area.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Piispa M., Heiskanen M., Kääriäinen J., Siren R., editors. Naisiin kohdistuva väkivalta 2005. [Violence against women in Finland in 2005.] (in Finnish. English summary available.) The European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control, affiliated with the United Nations (HEUNI); Helsinki: 2006. Available online at: http://hdl.handle.net/10138/152455 (accessed 1 January 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . WHO; Geneva: 2013. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Available online at: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/9789241564625/en/ (Accessed 1 January 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pico-Alfonso M.A., Garcia-Linares M.I., Celda-Navarro N., Blasco-Ros C., Echeburúa E., Martinez M. The impact of physical, psychological, and sexual intimate male partner violence on women’s mental health: depressive symptoms, posttraumatic stress disorder, state anxiety, and suicide. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2006;15:599–611. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen L.P., Murad M.H., Paras M.L., Colbenson K.M., Sattler A.L., Goranson E.N., et al. Sexual abuse and lifetime diagnosis of psychiatric disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:618–629. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Official Statistics of Finland (OSF): Statistics on offences and coercive measures [e-publication] Statistics Finland; Helsinki: 2017. Domestic violence and intimate partner violence 2016. Available online at: https://www.stat.fi/til/rpk/2016/15/rpk_2016_15_2017-05-31_tie_001_en.html (Accessed 1 January 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher B.S., Daigle L.E., Cullen F.T., Turner M.G. Reporting sexual victimization to the police and others: results from a national-level study of college women. Crim Justice Behav. 2003;30:6–38. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bogen K.W., Bleiweiss K.K., Leach N.R., Orchowski L.M. #MeToo: disclosure and response to sexual victimization on twitter. J Interpers Violence. 2019 doi: 10.1177/0886260519851211. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mervosh S. New York Times; 2018. Domestic violence awareness hasn’t caught up with #MeToo. Here’s why. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/16/us/domestic-violence-hotline-me-too.html (Accessed 8 January 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hegarty K., Tarzia L. Identification and management of domestic and sexual violence in primary care in the #MeToo era: an update. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21:12. doi: 10.1007/s11920-019-0991-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rabin R.F., Jennings J.M., Campbell J.C., Bair-Merritt M.H. Intimate partner violence screening tools: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:439–445. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.024. e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sherin K.M., Sinacore J.M., Li X.Q., Zitter R.E., Shakil A. HITS: a short domestic violence screening tool for use in a family practice setting. Fam Med. 1998;30:508–512. n.d. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feldhaus K.M., Koziol-McLain J., Amsbury H.L., Norton I.M., Lowenstein S.R., Abbott J.T. Accuracy of 3 brief screening questions for detecting partner violence in the emergency department. JAMA. 1997;277:1357–1361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown J.B., Lent B., Schmidt G., Sas G. Application of the Woman Abuse Screening Tool (WAST) and WAST-short in the family practice setting. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:896–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruuskanen E., Aromaa K. European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control, affiliated with the United Nations (HEUNI). Directorate General of Human Rights and Legal Affairs, Council of Europe; Strasbourg: 2008. Administrative data collections on domestic violence of Europe member states. Available online at: https://www.coe.int/t/dg2/equality/domesticviolencecampaign/Source/EG-VAW-DC(2008)Study_en.pdf (Accessed 8 January 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hussain N., Sprague S., Madden K., Hussain F.N., Pindiprolu B., Bhandari M. A comparison of the types of screening tool administration methods used for the detection of intimate partner violence. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2015;16:60–69. doi: 10.1177/1524838013515759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Broom D. World Economic Forum; 2019. Finland is the world’s happiest country – again. Available online at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/03/finland-is-the-world-s-happiest-country-again/ (Accessed 8 January 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alvarez C., Fedock G., Grace K.T., Campbell J. Provider screening and counseling for intimate partner violence: a systematic review of practices and influencing factors. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2017;18:479–495. doi: 10.1177/1524838016637080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berger R.P., Bogen D., Dulani T., Broussard E. Implementation of a program to teach pediatric residents and faculty about domestic violence. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:804–810. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.8.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sonu S., Post S., Feinglass J. Adverse childhood experiences and the onset of chronic disease in young adulthood. Prev Med (Baltim) 2019;123:163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson S.B., Riley A.W., Granger D.A., Riis J. The science of early life toxic stress for pediatric practice and advocacy. Pediatrics. 2013;131:319–327. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Adverse health conditions and health risk behaviors associated with intimate partner violence--United States, 2005. Morbidity Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008:57. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/wk/mm5705.pdf (Accessed 8 January 2020) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aakvaag H.F., Thoresen S., Strøm I.F., Myhre M., Hjemdal O.K. Shame predicts revictimization in victims of childhood violence: a prospective study of a general Norwegian population sample. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2019;11:43–50. doi: 10.1037/tra0000373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hakulinen-Viitanen T., Hietanen-Peltola M., Hastrup A., Wallin M., Pelkonen M. Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare: Juvenes Print – Tampereen yliopistopaino Oy; Tampere: 2012. Laaja terveystarkastus - Ohjeistus äitiys- ja lastenneuvolatoimintaan sekä kouluterveydenhuoltoon. [Comprehensive health examination – instructions for maternity and child health clinics and school health care.] (in Finnish. No abstract available.) Available online at: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-245-708-0 (Accessed 8 January 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 24.García-Moreno C. Dilemmas and opportunities for an appropriate health-service response to violence against women. Lancet (London, England) 2002;359:1509–1514. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08417-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mercy J.A., Hillis S.D., Butchart A., Bellis M.A., Ward C.L., Fang X., et al. 2017. Interpersonal violence: global impact and paths to prevention. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pohjanpää K., Paananen S., Nieminen M. Statistics Finland; Helsinki: 2003. Maahanmuuttajien elinolot. Venäläisten, virolaisten, somalialaisten ja vietnamilaisten elämää Suomessa vuonna 2002. [Immigrant living conditions. The lives of Russians, Estonians, Somalis and Vietnamese in Finland in 2002.] (in Finnish. No abstract available.) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joshi M., Sorenson S.B. Intimate partner violence at the scene: incident characteristics and implications for public health surveillance. Eval Rev. 2010;34:116–136. doi: 10.1177/0193841X09360323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Usher K., Bhullar N., Durkin J., Gyamfi N., Jackson D. Family violence and COVID‐19: increased vulnerability and reduced options for support. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2020;29:549–552. doi: 10.1111/inm.12735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mendes K., Ringrose J., Keller J. #MeToo and the promise and pitfalls of challenging rape culture through digital feminist activism. Eur J Women’s Stud. 2018;25:236–246. [Google Scholar]