The development of asciminib (ABL001)1, a low nanomolar allosteric BCR-ABL1 tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), is the culmination of programs in academic and pharmaceutical industry laboratories spanning more than a decade. Currently in clinical trials for relapsed/refractory Philadelphia chromosome-positive (Ph+) leukemia patients (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02081378), asciminib represents a major advance from the structurally related, micromolar-potency tool compounds GNF-2 and GNF-52–4. We investigated mechanisms of asciminib resistance and identified two major categories: (1) upregulation of the ABCG2 efflux pump, resulting in undetectable intracellular asciminib levels, and (2) emergence of BCR-ABL1 mutations at the myristoyl-binding site and at a distant residue.

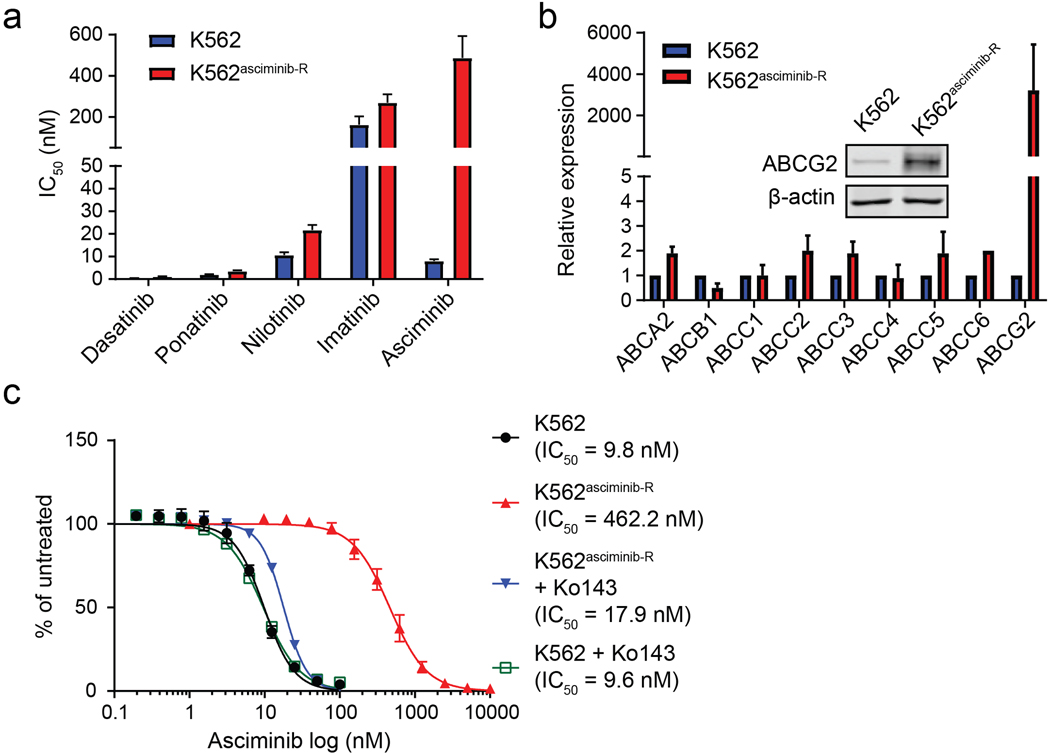

We generated five asciminib-resistant, BCR-ABL1-positive cell lines by adapting to increasing concentrations of asciminib : K562asciminib-R, LAMA84asciminib-R, KYO1asciminib-R, Ba/F3 BCR-ABL1asciminib-R and KCL-22asciminib-R cells (Supplemental Methods). In K562asciminib-R cells, methanethiosulfonate (MTS)-based cell proliferation assays demonstrated a ~60-fold increase in asciminib IC50 compared to parental K562 cells, despite remaining sensitive to the ATP-site TKIs imatinib, nilotinib, dasatinib and ponatinib (Figure 1a; Table S1). Immunoblot analysis revealed similar results, showing marked restoration of BCR-ABL1 tyrosine kinase activity and downstream STAT5 tyrosine phosphorylation in the presence of asciminib but not ponatinib (Figure S1a). However, Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) and Sanger sequencing of the BCR-ABL1 kinase domain identified no mutations (Table S2)5. To check for the possibility of reduced intracellular drug concentrations, asciminib levels were measured following treatment using a customized liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) method6. Asciminib was undetectable in K562asciminib-R cells but present at substantial levels in parental K562 cells (Figure S1b), with an inhibitor-based screen for potential involvement of efflux pumps (Figure S1c) and analysis by qPCR and immunoblot (Figure 1b) all implicating ABCG2. Cell proliferation experiments revealed that the ABCG2 inhibitor Ko143 restored asciminib effectiveness against K562asciminib-R cells but had no effect on the asciminib IC50 for K562 cells (Figure 1c). Similar results were obtained for LAMA84asciminib-R (Figure S2; Table S1, S2) and KYO1asciminib-R cells (Figure S3; Table S1, S2). Our findings support ABCG2-mediated efflux of asciminib as the major mechanism of resistance in these cell lines, warrant its profiling among patients with asciminib resistance in the clinic, and suggest that combining asciminib with an ABCG2 inhibitor could override resistance, though development of clinical ABCG2 inhibitors is at the investigational stage7, 8.

Figure 1.

Upregulation of the ABCG2 efflux pump eliminates asciminib from K562asciminib-R cells and confers high-level resistance to asciminib. (a) K562asciminib-R cells retain sensitivity to TKIs that target the ATP site. (b) qPCR of candidate efflux pumps and (inset) ABCG2 immunoblot confirm ABCG2 upregulation in K562asciminib-R cells. (c) Inclusion of the ABCG2 inhibitor, Ko143, restores asciminib sensitivity to K562asciminib-R cells.

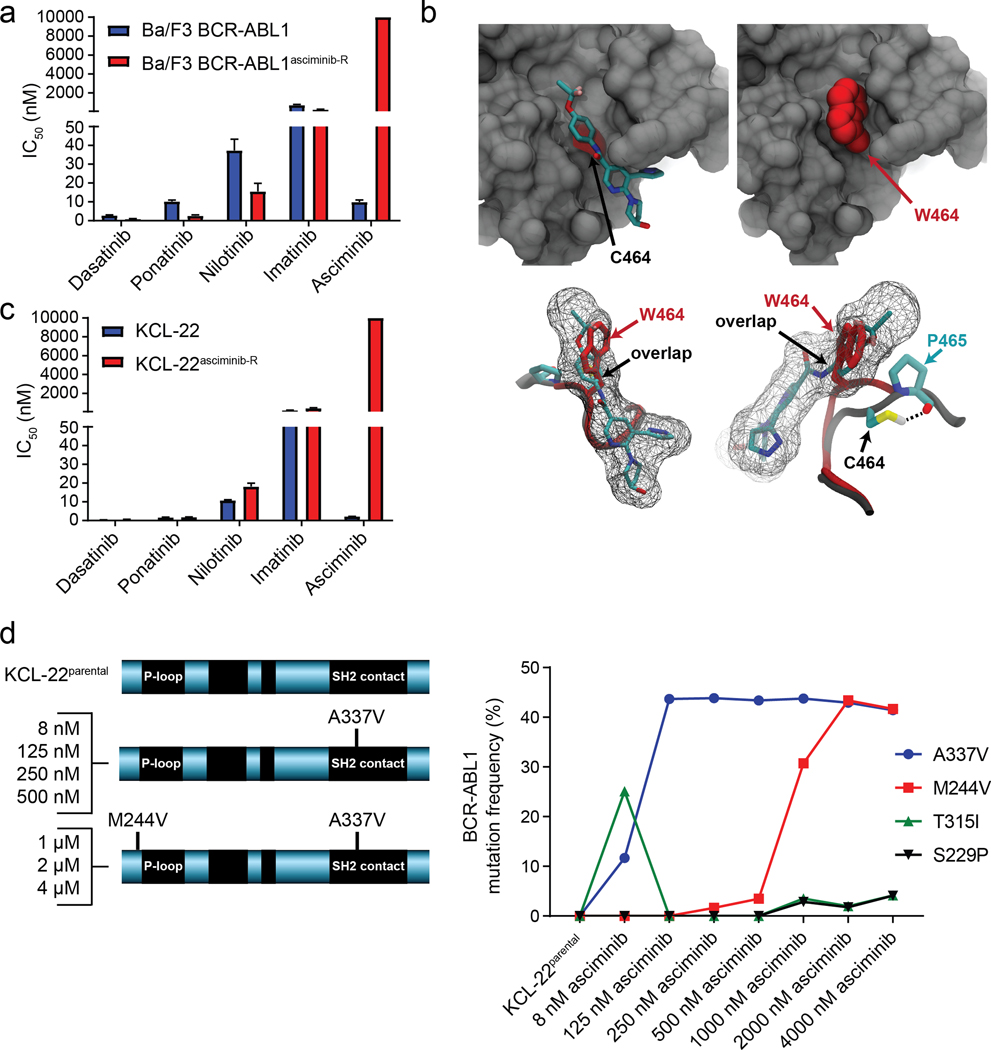

In contrast, mutation-based resistance mechanisms were observed in Ba/F3 BCR-ABL1asciminib-R and KCL-22asciminib-R cells. In Ba/F3 BCR-ABL1asciminib-R cells, a >1,000-fold increase in asciminib IC50 over Ba/F3 BCR-ABL1 cells was observed, despite undiminished sensitivity to ATP-site TKIs (Figure 2a; Table S1). While immunoblot analysis demonstrated restored BCR-ABL1 signaling in Ba/F3 BCR-ABL1asciminib-R cells treated with asciminib (Figure S4a), LC-MS/MS analysis showed similar amounts of asciminib in Ba/F3 BCR-ABL1 and Ba/F3 BCR-ABL1asciminib-R cells and there was no evidence of efflux pump involvement (Figure S4b–e). NGS and Sanger sequencing of the BCR-ABL1 kinase domain identified a novel BCR-ABL1C464W mutation (Table S2), which was demonstrated through computational modeling to block access of asciminib to the myristoyl-binding pocket, consistent with high-level resistance (Figure 2b). While other BCR-ABL1 mutations within or near the myristoyl-binding pocket (e.g. A337V; P465S; V468F) have been recently reported to confer asciminib resistance1, this is the first report of BCR-ABL1C464W as an asciminib-resistant mutant.

Figure 2.

BCR-ABL1 mutations in the myristoyl-binding pocket and at a remote site confer asciminib resistance. (a) Myristoyl-binding site mutation BCR-ABL1C464W confers high-level resistance to asciminib but not to ATP-site TKIs. (b) Structural analysis of the C464W mutation in the allosteric myristoyl-binding pocket. (upper left) Close-up view of the asciminib-bound allosteric pocket. For visualization of the deeper pocket some residues are not shown. The Cα position of the C464 residue is highlighted in red, while the sidechain is partially buried inside the pocket. (upper right) C464W mutation occupies the deep hydrophobic cleft due to its bulky sidechain, making critical interaction with the αI helix, while blocking access of asciminib. The mutated residue is shown as a space-filling model (highlighted in red). (lower) Two sideviews of the asciminib-binding pocket show the native and C464W mutant sidechain alignments with respect to asciminib binding. The first image is oriented to match the preceding images in this panel. The second image is rotated to allow visualization of hydrogen-bonding interaction. The sidechain of C464 is buried in the interior of the protein and participates in thiol-mediated hydrogen bonding with the P465 residue. However, on mutation to W464, the tryptophan sidechain is sterically incompatible with P465 and is forced to occupy the myristoyl-binding pocket, interfering with asciminib binding. (c) KCL-22asciminib-R cells exhibit high-level resistance to asciminib but not to ATP-site TKIs. (d) NGS sequencing of KCL-22 cells, increasingly asciminib-resistant cells collected in the process of generating the final resistant line and the KCL-22asciminib-R cell line reveals a progression from BCR-ABL1 through BCR-ABL1A337V to BCR-ABL1M244V/A337V.

KCL-22asciminib-R cells exhibited two mutations at similar allelic frequencies9: BCR-ABL1M244V near the ATP site and BCR-ABL1A337V in the myristoyl-binding pocket (Table S2), and single-cell sorting followed by clonal sequencing revealed a BCR-ABL1M244V/A337V compound mutation10, 11. KCL-22asciminib-R cells were completely insensitive to asciminib (IC50: 10,000 nM as compared to 2.2 nM for parental KCL-22 cells), but remained sensitive to ATP-site TKIs (Figure 2c; Figure S5a; Table S1). LC/MS-MS showed comparable intracellular asciminib levels in KCL-22asciminib-R and KCL-22 cells, and there was no evidence of either altered effectiveness of asciminib against KCL-22asciminib-R cells by inclusion of an efflux pump inhibitor or upregulation of an efflux pump by qPCR or ABCG2 immunoblot (Figure S5b–e). Sequencing of increasingly asciminib-resistant cells collected in the process of generating the final KCL-22asciminib-R cell line revealed a progression from BCR-ABL1A337V to BCR-ABL1M244V/A337V (Figure 2d). The reported asciminib IC50 value of 702 nM for KCL-22A337V cells1 is consistent with the inability of this mutation alone to confer the high-level resistance observed in KCL-22asciminib-R cells. The BCR-ABL1M244V/A337V compound mutant confers high-level asciminib resistance but inclusion of clinically achievable concentrations of imatinib lead to outgrowth of BCR-ABL1S229P/T315I at the expense of BCR-ABL1M244V/A337V (Figure S6), highlighting a potential complication of addressing asciminib resistance by switching to or including an ATP-site TKI.

Taken together, our findings suggest that mechanisms of acquired resistance to the allosteric BCR-ABL1 inhibitor asciminib involve restoration of BCR-ABL1 signaling, due to either asciminib efflux or select BCR-ABL1 mutations. It may be possible to override ABCG2-mediated drug efflux by dose escalation of asciminib. The achievable clinical dose is estimated to be at least 1 μM12. Another possibility to circumvent this resistance mechanism is to design a next-generation allosteric inhibitor that is not a substrate for efflux pump(s). While development of a next-generation allosteric inhibitor13 is possible, the potential for cross-resistant myristoyl-binding pocket mutations may be high, as those observed for asciminib to date completely block inhibitor access to the binding pocket. Alternatively, myristoyl-binding site mutation-based resistance to asciminib could be countered with a TKI that binds at the ATP site, though such a mutation occurring in tandem with an additional kinase domain mutation could result in resistance to both types of inhibitor. The strategy of simultaneously treating with asciminib and an ATP-site TKI (imatinib, nilotinib or dasatinib) to minimize opportunity for resistance is under clinical investigation. Ponatinib, which has activity against the T315I mutant and reported potency as an ABCG2 inhibitor14, 15, may also warrant consideration in this setting.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

WQ is supported by NSFC (81400105) and Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong (2014A020212185). This work was supported by NIH/NCI R01CA178397 (MD, TO) and Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA042014.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

TWK has financial interests to declare: Novartis speaker’s bureau, Novartis advisory board. DR receives honoraria from BMS, Novartis, Incyte and Pfizer for non-promotional scientific lectures or advisory boards and is an investigator of Novartis-sponsored CABL001X2101 phase I trial. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wylie AA, Schoepfer J, Jahnke W, Cowan-Jacob SW, Loo A, Furet P, et al. The allosteric inhibitor ABL001 enables dual targeting of BCR-ABL1. Nature 2017; 543: 733–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gray NS, Fabbro D. Discovery of allosteric BCR-ABL inhibitors from phenotypic screen to clinical candidate. Methods Enzymol 2014; 548: 173–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adrian FJ, Ding Q, Sim T, Velentza A, Sloan C, Liu Y, et al. Allosteric inhibitors of Bcr-abl-dependent cell proliferation. Nat Chem Biol 2006; 2: 95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang J, Adrian FJ, Jahnke W, Cowan-Jacob SW, Li AG, Iacob RE, et al. Targeting Bcr-Abl by combining allosteric with ATP-binding-site inhibitors. Nature 2010; 463: 501–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Szankasi P, Schumacher JA, Kelley TW. Detection of BCR-ABL1 mutations that confer tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance using massively parallel, next generation sequencing. Ann Hematol 2016; 95: 201–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Hare T, Eide CA, Agarwal A, Adrian LT, Zabriskie MS, Mackenzie RJ, et al. Threshold levels of ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitors retained in chronic myeloid leukemia cells determine their commitment to apoptosis. Cancer Res 2013; 73: 3356–3370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miyata H, Takada T, Toyoda Y, Matsuo H, Ichida K, Suzuki H. Identification of Febuxostat as a New Strong ABCG2 Inhibitor: Potential Applications and Risks in Clinical Situations. Front Pharmacol 2016; 7: 518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Westover D, Li F. New trends for overcoming ABCG2/BCRP-mediated resistance to cancer therapies. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2015; 34: 159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan H, Wang Z, Gao C, Chen W, Huang Q, Yee JK, et al. BCR-ABL gene expression is required for its mutations in a novel KCL-22 cell culture model for acquired resistance of chronic myelogenous leukemia. J Biol Chem 2010; 285: 5085–5096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah NP, Skaggs BJ, Branford S, Hughes TP, Nicoll JM, Paquette RL, et al. Sequential ABL kinase inhibitor therapy selects for compound drug-resistant BCR-ABL mutations with altered oncogenic potency. J Clin Invest 2007; 117: 2562–2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zabriskie MS, Eide CA, Tantravahi SK, Vellore NA, Estrada J, Nicolini FE, et al. BCR-ABL1 compound mutations combining key kinase domain positions confer clinical resistance to ponatinib in Ph chromosome-positive leukemia. Cancer Cell 2014; 26: 428–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ottman OG, Alimena G, DeAngelo DJ, Goh Y-T, Heinrich MC, Hochhaus A, et al. ABL001, a potent, allosteric inhibitor or BCR-ABL, exhibits safety and promising single-agent activity in a phase I study of patients with CML with failure of prior TKI therapy. Blood 2015; 126. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng X, Okram B, Ding Q, Zhang J, Choi Y, Adrian FJ, et al. Expanding the diversity of allosteric BCR-ABL inhibitors. J Med Chem 2010; 53: 6934–6946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sen R, Natarajan K, Bhullar J, Shukla S, Fang HB, Cai L, et al. The novel BCR-ABL and FLT3 inhibitor ponatinib is a potent inhibitor of the MDR-associated ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCG2. Mol Cancer Ther 2012; 11: 2033–2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu L, Saunders VA, Leclercq TM, Hughes TP, White DL. Ponatinib is not transported by ABCB1, ABCG2 or OCT-1 in CML cells. Leukemia 2015; 29: 1792–1794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.