Abstract

Objectives

This study considers whether experiencing the death of a child prior to midlife (by parental age 40) is associated with subsequent dementia risk, and how such losses, which are more common for black than for white parents, may add to racial disparities in dementia risk.

Methods

We use discrete-time event history models to predict dementia incidence among 9,276 non-Hispanic white and 2,182 non-Hispanic black respondents from the Health and Retirement Study, 2000–2014.

Results

Losing a child prior to midlife is associated with increased risk for later dementia, and adds to disparities in dementia risk associated with race. The death of a child is associated with a number of biosocial variables that contribute to subsequent dementia risk, helping to explain how the death of child may increase risk over time.

Discussion

The death of a child prior to midlife is a traumatic life course stressor with consequences that appear to increase dementia risk for both black and white parents, and this increased risk is explained by biosocial processes likely activated by bereavement. However, black parents are further disadvantaged in that they are more likely than white parents to experience the death of a child, and such losses add to the already substantial racial disadvantage in dementia risk.

Keywords: Bereavement, Cumulative advantage/disadvantage, Dementia, Minority aging (race/ethnicity)

Dementia is a growing public health concern around the world, particularly in countries with aging populations such as the United States (Alzheimer’s Association, 2019; Blazer, Yaffe, & Liverman, 2015). Like other health outcomes, dementia risk is not equally distributed in the population. Dementia prevalence is two or more times greater for black than for white Americans, and dementia emerges at substantially younger ages for black Americans (Alzheimer’s Association, 2019; Glymour & Manly, 2008; Mayeda, Glymour, Quesenberry, & Whitmer, 2016). A number of biological, psychological, social, and behavioral mechanisms are associated with increased risk for dementia (Blazer et al., 2015; Glymour & Manly, 2008), but specific life course events that trigger these mechanisms are largely unidentified (Babulal et al., 2019).

Growing evidence points to the role of stress in contributing to dementia risk (Blazer et al., 2015; Greenberg, Tanev, Marin, & Pitman, 2014; Peavy et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2016), and one of the most stressful events one can experience is the death of a child (Stroebe, Schut, & Stroebe, 2007). The higher rates of premature mortality for black Americans at every age (Rogers, Hummer, Krueger, & Vinneau, 2019)—a result of the legacy of racism in the United States—mean that black parents are much more likely than white parents to experience the death of a child, and to experience these losses at younger ages (Umberson et al., 2017). If the death of a child occurs prior to midlife, there may be many years after which mechanisms of risk (e.g., depression) are activated, adding to later life dementia risk.

While black parents are more likely than white parents to lose a child and to develop dementia, prior work has not directly addressed the death of a child as a unique life course stressor prior to midlife that may add to racial disadvantage in later dementia risk, the biosocial processes that might explain increased risk, or how race differences in exposure and vulnerability to the loss of a child may influence the association of bereavement with dementia risk. In the present study, we analyze Health and Retirement Study (HRS) data to address these gaps. A focus on the death of a child as a unique life course event occurring prior to midlife that contributes to later life dementia may help policymakers shift their thinking about dementia as a public health problem of old age to a public health problem that has its origins earlier in the life course, and as contributing to racial disadvantage in dementia risk.

Background

Dementia is a geriatric syndrome in which declining cognitive function reaches sufficient severity to interfere with independent function and self-care. The disease burden of dementia is devastating for both the individual and their family members, adds to overall health costs in the United States, and is likely to increase in the future as the population ages and socially disadvantaged groups become a larger segment of the older population (Blazer et al., 2015). As noted above, this burden is borne disproportionately by black Americans (Alzheimer’s Association, 2019; Mayeda et al., 2016). Race differences in dementia risk have been attributed to a wide range of factors including lower socioeconomic status (SES) (particularly education), lower rates of marriage, and greater incidence of vascular disease (e.g., cardiometabolic conditions and stroke) for black Americans (Glymour & Manly, 2008; Liu, Zhang, Choi, & Langa, 2019; Peterson, Fain, Butler, Ehiri, & Carvajal, 2019; Zhang, Hayward, & Yu, 2016), but stress is receiving increasing attention as a contributor to higher rates of dementia among black Americans (Forrester, Gallo, Whitfield, & Thorpe, 2018; Peterson et al., 2019). Stress has been associated with increased dementia risk regardless of race (Greenberg et al., 2014; Peavy et al., 2012) but substantial evidence documents higher levels of stress for black Americans throughout the life course (Williams, 2018; Williams, Lawrence, & Davis, 2019). Stress may have long-term “neurotoxic” effects that increase risk, as well as indirect effects by activating biosocial factors (e.g., health damaging behaviors, lower earnings, depression, and poor physical health) that increase risk (Forrester et al., 2018; Glymour & Manly, 2008; McEwen, 2007; Whitfield & Baker, 2013; Zahodne, Sol, & Kraal, 2019). Traumatic stressors, such as the death of a child, may constitute a major turning point in the life course by triggering or exacerbating these mechanisms of risk (Greenberg et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2016). Glymour and Manly (2008) emphasize that, “cognitive function is a developmental trajectory, and harmful exposures may influence the likelihood of impairments in old age by derailing the maturation trajectory, promoting pathological processes, or restricting compensation or resilience after pathological events” (p. 224), and Peterson and colleagues (2019) argue that “disparities between African Americans and non-Hispanic whites may widen if the risks driving them are not better understood…” (p. 1).

There are a number of reasons to view the death of a child as a uniquely traumatic life event with substantial adverse consequences. The death of any significant other has adverse health effects, but prior studies indicate that the death of a child has stronger and more enduring effects on health and well-being than other types of loss (Stroebe et al., 2007). Relationships with children are unique in a number of ways that may contribute to these enduring effects. Parents often report feeling a loss of part of the self after a child dies (Rogers, Floyd, Seltzer, Greenberg, & Hong, 2008). This may occur because the parent/child relationship is fundamental to personal identity in adulthood, and because parents expect to predecease their children (Rogers et al., 2008). Prior studies show that premature or off-time losses (i.e., death of significant others occurring earlier in the life course than expected) have stronger effects on health following bereavement (Smith, Hanson, Norton, Hollingshaus, & Mineau, 2014; Stroebe et al., 2007), and—because parents expect to predecease their children—the death of a child at any age is “off-time.” The death of a child disrupts parents’ expectations about future possibilities for both the child and the parent. Loss at younger ages may mean the loss of “what could be,” and, as bereaved parents age, the absence of typical support exchanges between the generations that benefit parental health and well-being (Fingerman & Birditt, 2011; Rogers et al., 2008). While very little research has addressed bereavement and cognitive status, the death of a parent during childhood (Norton, Østbye, Smith, Munger, & Tschanz, 2009; Ravona-Springer, Beeri, & Goldbourt, 2012), and the death of a spouse (Gerritsen et al., 2017; Vidarsdottir et al., 2014) or child (Greene et al., 2014) in adulthood have been linked to poorer cognitive functioning and/or increased dementia risk—but only in white populations (e.g., rural Utah, European, and Israeli samples). These prior studies do not take into account the greater exposure of black Americans to the death of a child throughout the life course. Moreover, black parents who lose a child may be more vulnerable than white parents because black Americans are more likely than white Americans to experience multiple family member losses over the life course and earlier in the life course (Umberson et al., 2017), and because this loss occurs against the backdrop of lifelong and myriad stressors associated with racism and discrimination in the United States (Forrester et al., 2018; Glymour & Manly, 2008; Whitfield & Baker, 2013; Williams, 2018; Williams et al., 2019). Older black adults are also less likely to have any living kin (Verdery & Margolis, 2017) and fewer socioeconomic resources (Williams et al., 2019) to help them cope with stress, which could amplify the consequences of losing a child. We test the following hypotheses to consider whether the death of a child prior to midlife is associated with increased dementia risk, as well as the possibility that greater exposure and vulnerability to loss associated with race may contribute to dementia risk:

H1. The death of a child prior to midlife will increase parents’ subsequent dementia risk, adding to racial disparities in dementia risk. (Exposure Hypothesis)

H2. The death of a child prior to midlife will have stronger effects on dementia risk for black parents than for white parents. (Vulnerability Hypothesis)

Mechanisms of Risk

Past studies suggest a number of biosocial mechanisms through which bereavement might increase dementia risk (Greene et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2019; Norton et al., 2009; Ravona-Springer et al., 2012). For example, the death of a child may increase risk for depression (psychological mechanism), diminished earnings (social mechanism), alcohol consumption and smoking (behavioral mechanisms), and cardiovascular disease (biological mechanism) (Greene et al., 2014; Rogers et al., 2008; Stroebe et al., 2007; Umberson, 2017)—all of which may contribute to dementia risk (Blazer et al., 2015; Glymour & Manly, 2008; James & Bennett, 2019). In the years and decades following a child’s death, these biosocial processes may add to cumulative disadvantage in dementia risk. Moreover, while mechanisms of risk may be triggered by loss of a child regardless of race, they may be further compounded for black parents by the chronic stress black Americans experience due to racism in the United States (Glymour & Manly, 2008; Forrester et al., 2018; Williams, 2018; Williams et al., 2019). For example, a legacy of racism in the United States has resulted in lower levels of education and wealth, residential segregation, and higher levels of stress and discrimination for black Americans. In turn, stress can increase risk for coping behaviors that undermine health (e.g., smoking, drinking), interfere with health promotion (e.g., safe places and time to exercise), and increase allostatic load (accumulated effects of stress on the body and brain) (Forrester et al., 2018). Research on racial disparities in dementia emphasize that “it is the exposure and accumulation of environmental, sociocultural and/or behavior factors over time that shapes the vulnerability of biological risk and likely produces the disparate rates” among black adults (Peterson et al., 2019, p. 2). Therefore, we test the following hypotheses:

H3. The death of a child will be associated with biosocial factors identified in prior research as increasing dementia risk.

H3a. The death of a child will be more strongly associated with biosocial factors for black parents than for white parents.

H3b. Biosocial factors will explain the association of child loss with dementia risk.

Method

Data

Data for the following analyses are from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), an ongoing biannual survey launched in 1992. The initial sample included individuals born between 1931 and 1941 as well as their spouses/partners of any age. The HRS adds new cohorts of adults aged 50–55 years old every 6 years. The War Baby cohort (WB; born 1942–1947) entered the study in 1998, the Early Baby Boomer cohort (EBB; born 1948–1953) entered in 2004, and the Mid Baby Boomer cohort (MBB; born 1954–1959) entered in 2010. Only non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic black respondents who ever had any biological children are included in the analytic sample for the present study. Since the focus of this article is on child loss prior to midlife, respondents who lost a child after age 40 are excluded from the analysis. Dementia was assessed from 2000 to 2014; the sample consists of respondents with nonmissing measures for dementia. Respondents were free of dementia at the baseline wave, which refers to the respondent’s first wave with measurement of dementia status. For example, the baseline wave for the HRS and the WB cohorts is 2000, 2004 for the EBB cohort, and 2010 for the MBB cohort. The final analytic sample includes 9,276 non-Hispanic white respondents and 2,182 non-Hispanic black respondents.

Measures

Dementia

The measure of dementia status was developed specifically for the HRS by Langa and colleagues—referred to as the Langa-Weir classification of cognitive function (Langa, Weir, Kabeto, & Sonnega, 2018); this classification is commonly used in studies of dementia in the United States (e.g., Dassel, Carr, & Vitaliano, 2017; Langa et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2019). This approach includes proxy- as well as self-reports to assess dementia because people who experience dementia may struggle with completing self-reported measures of cognitive status on their own. Measurement of self-reported dementia status is based on a summary score of immediate word recall (Score 0–10), delayed word recall (Score 0–10), serial subtraction of 7s (Score 0–5), and backward counting from 20 (Score 0–2), which ranges from−0 to 27. The Langa-Weir classification of cognitive function classifies respondents who scored 6 or lower as having dementia. Proxy-reported dementia status is based on a rating of respondents’ current memory from excellent to poor (Score 0–4); assessment of limitations in five instrumental activities of daily living including using the phone, managing money, taking medication, preparing hot meals, and shopping for groceries (Score 0–5); and the interviewer’s evaluation of difficulty completing the interview because of cognitive limitations (Score 0–2), which sum to 11. In line with Langa and colleagues, we classify respondents who received a proxy-reported score of 6 or higher as having dementia (N = 322 respondents with proxy reports in the 2000 data collection). About 10% of interviews in the HRS are conducted through proxy reports (Langa et al., 2008). The cut points for the Langa-Weir classification parallel the distribution of cognitive status as found in the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study (ADAMS; a detailed neuropsychiatric assessment performed by clinicians on a subsample of HRS respondents). The HRS dementia measures are highly reliable with more than 80% probability of correct classification for proxy and self-reports based on the ADAMS assessment, when accounting for demographic information, such as gender, age, and education group (Crimmins, Kim, Langa, & Weir, 2011). Following previous studies that assess dementia using the HRS (Langa et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2019), we assess risk of dementia relative to those not having dementia.

Race

Race is a major focus of this study, with attention to disadvantage experienced by black Americans. Thus, we restrict our analysis to non-Hispanic white and non-Hispanic black respondents, with non-Hispanic black coded as 1.

Death of a child prior to midlife

Beginning in 2004 (as a pilot study) until 2012, a leave-behind questionnaire linked to the HRS asked respondents whether they had ever experienced the death of a child and the most recent year of a child’s death. Parent age at the time of the child’s death is calculated by subtracting year at child loss from respondent’s birth year. Respondents who experienced child loss by age 40 are coded as 1 with parents who never experienced a child death serving as the reference group.

Biosocial covariates

We consider several biosocial factors that may be affected by child loss and, in turn, contribute to dementia risk. We use an adjusted household income measure as a possible social factor linking child death to dementia: we log-transformed household income, added a constant to eliminate zero incomes, and divided by the square root of household size. Psychological distress is considered as a possible psychological factor associated with child loss as well as risk of dementia. Distress is measured with an 8-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale which assessed whether respondents felt depressed, felt that everything s/he did was an effort, sleep was restless, could not get going, felt lonely, enjoyed life, felt sad, and was happy much of the time during the past week (Steffick, 2000). Positive items are reversed coded so that higher scores indicate higher levels of psychological distress (ranging from 0 to 8).

Behavioral factors include drinking status, smoking status, and physical activity. Drinking is coded into three categories: nondrinker, moderate drinker (reference), and heavy drinker. Moderate drinker refers to those who drank 1–7 alcoholic beverages per week, and heavy drinker refers to those who drank 8 beverages or more per week. These categories are based on guidelines for classification of alcohol consumption among older adults established by the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Lin, Guerrieri, & Moore, 2011). We do not differentiate former drinkers from those who never drank because a supplementary analysis shows that combining former drinkers with nondrinkers does not affect the results.

Smoking status is indicated by three categories: never smoked (reference), former smoker, and current smoker. Physical activity is dummy coded with 1 referring to respondents who participated in vigorous physical activity three or more times per week on average over the last 12 months. We assess body mass index (BMI), self-rated health, and cardiometabolic conditions as biological factors that may be associated with child loss and dementia. BMI is a continuous variable that is calculated as weight divided by the square of height. Poor self-rated heath is a dummy variable coded as 1 if respondents reported their health as fair or poor and 0 for reports of health as excellent, very good, or good. Cardiometabolic conditions count number of ever-diagnosed conditions, including heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and hypertension. Measures of biosocial factors are time-invariant and come from the baseline wave when data on dementia is first available. Time-invariant biosocial measures are used because preliminary analyses showed that child loss is not associated with trajectories of change over the study period in the biopsychosocial and behavioral factors considered.

Other covariates

We include a control for other family member deaths prior to midlife to address the substantially higher rates of family bereavement for black compared with white Americans. This measure is coded as 1 if respondents experienced the death of a mother, father, spouse, or sibling by the respondent’s baseline wave. Additional covariates measured at baseline include gender (women = 1), birth place in the South compared with non-South (South = 1), education, and marital status. Marital status is coded as a dummy variable with married coded as 1. Education has four categories: less than high school (reference group), high school, some college, and college and above. Birthplace in the South, education, and marital status have been associated with dementia risk in prior studies (Gilsanz, Mayeda, Glymour, Quesenberry, & Whitmer, 2017; Liu et al., 2019; Meng & D’Arcy, 2012). We include gender to account for differences in lifetime risk for dementia (Chêne et al. 2015).

Analytic Strategy

We use discrete-time event history models to examine dementia incidence (compared with nondementia status) from 2000 to 2014. Person-interval data were created for analyses and respondents could contribute one to seven 2-year intervals from 2000 to 2014. The risk set includes respondents who did not have dementia at the first wave when their dementia status was measured. Respondents could exit the risk set in three ways: develop dementia, die, or drop out of the study during follow-up. Dropping out of the sample and death are considered as competing risks to avoid biasing the estimates for dementia incidence (Allison, 2010; Zhang et al., 2016). As the onset of dementia is age dependent, we estimate multinomial logistic regression with age as the time metric. We present results from the multinomial logistic regression models predicting dementia incidence; results from models predicting death or dropout are available upon request. We first examine whether child loss is associated with dementia risk during follow-up. We then test whether loss of a child is associated with social, psychological, behavioral, and biological factors assessed at the baseline interview and whether these associations differ by race. Linear regression is used for models predicting the association of child loss with household income, psychological distress, and BMI whereas multinomial logistic regression is used for models predicting smoking and drinking behavior. Logistic regression is used for models predicting physical activity and self-rated health. Poisson regression is used to estimate number of cardiometabolic conditions. Lastly, we test whether the association between child loss and risk of dementia is explained by social, psychological, behavioral, and biological factors. All models are analyzed using Stata 15.1.

Results

Descriptive Results

Descriptive results in Table 1 show that black respondents are significantly more likely than white respondents to lose a child by age 40, when 7.63% of white parents have lost a child compared with 12.33% of black parents. The median age of parents at the time of child loss is 26 years in this sample. Black respondents are also over two times more likely to develop dementia over the observation period (2000–2014). Compared with white respondents, black respondents are slightly younger, more likely to be female, born in the South, and have lower levels of education. On average, black respondents also have lower household income, higher levels of psychological distress and BMI, and more cardiometabolic conditions. Black respondents are more likely to be unmarried, current smokers, and nondrinkers but less likely to exercise vigorously compared with white respondents. A higher percentage of black respondents report fair or poor self-rated health.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for All Variables, Health and Retirement Study

| Variables | Total sample % or Mean (SD) | Non-Hispanic white % or Mean (SD) | Non-Hispanic black % or Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dementia incidence | 6.89 | 5.50 | 12.83*** |

| Parent bereaved by age 40 | 8.53 | 7.63 | 12.33*** |

| Non-Hispanic (NH) black | 19.04 | ― | ― |

| Female | 57.41 | 55.60 | 65.12*** |

| Born in the South | 35.97 | 28.95 | 65.86*** |

| Less than high school | 13.05 | 10.68 | 23.10*** |

| High school | 37.26 | 38.14 | 33.50*** |

| Some college | 26.15 | 25.52 | 28.83** |

| College and above | 23.55 | 25.66 | 14.57*** |

| Married at baseline | 77.70 | 82.84 | 55.87*** |

| Other family member deaths | 84.72 | 84.54 | 85.47 |

| Household income (Ln) | 10.34 (1.13) | 10.48 (1.02) | 9.74 (1.33)*** |

| Psychological distress | 1.35 (1.86) | 1.24 (1.79) | 1.84 (2.07)*** |

| Nonsmoker | 40.79 | 40.91 | 40.28 |

| Former smoker | 39.07 | 40.17 | 34.42*** |

| Current smoker | 20.13 | 18.92 | 25.30*** |

| Nondrinker | 62.18 | 60.37 | 69.89*** |

| Moderate drinker | 26.79 | 27.84 | 22.36*** |

| Heavy drinker | 11.02 | 11.79 | 7.75*** |

| Vigorous physical activity | 43.15 | 45.68 | 32.40*** |

| BMI | 28.37 (5.80) | 27.92 (5.51) | 30.30 (6.56)*** |

| Fair/poor self-rated health | 19.19 | 16.14 | 32.17*** |

| Cardiometabolic conditions | 0.68 (0.82) | 0.62 (0.79) | 0.97 (0.90)*** |

| Age at baseline | 58.01 (6.58) | 58.23 (6.67) | 57.07 (6.06)*** |

| Number of deaths during follow-up | 1,142 | 961 | 181 |

| Number of dementia cases during follow-up | 790 | 510 | 280 |

| N | 11,458 | 9,276 | 2,182 |

Note. BMI refers to body mass index. Mean and standard deviation are presented for continuous variables. Percentages are presented for categorical variables.

***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05.

Child Loss and Dementia Risk

Hypothesis 1 (exposure)

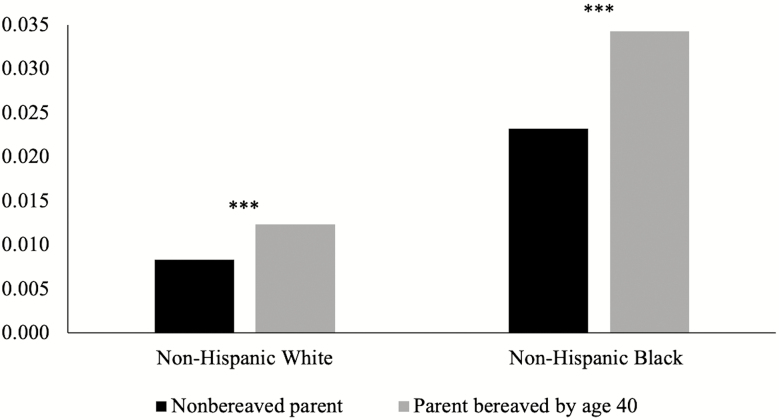

We first consider whether exposure to the death of a child is associated with increased risk for dementia, adding to racial disparities in dementia risk (Table 2). Results from Model 1 show that child loss prior to midlife (p < .001) is significantly associated with increased risk for subsequent dementia net of age, race, gender, respondent birthplace in the South, and death of other family members. Parents who lose a child prior to midlife have 50% greater odds of developing dementia compared with parents who do not lose a child. Model 1 also shows that black parents are almost three times more likely than white parents to develop dementia over the HRS study period (p < .001). Thus, results from Model 1 suggest that race and child loss have independent and additive effects on dementia risk. These additive effects are illustrated in Figure 1. Model 2 shows that the positive association between child loss prior to midlife with dementia risk decreases after controlling for education but remains significant (p < .05). Overall, these results provide support for Hypothesis 1, with child loss by age 40 associated with increased risk for dementia, net of covariates.

Table 2.

Multinomial Logistic Regression Predicting Dementia Incidence by Death of a Child Prior to Midlife, Health and Retirement Study, 2000–2014 (N = 11,458)

| Dementia vs nondementia | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

| Parent bereaved by age 40 | 0.404*** | 0.274* | 0.279* |

| (0.106) | (0.107) | (0.139) | |

| Non-Hispanic (NH) black | 1.078*** | 0.852*** | 0.854*** |

| (0.084) | (0.088) | (0.094) | |

| Parent bereaved by age 40 × NH black | −0.015 | ||

| (0.216) | |||

| Female | −0.231** | −0.288*** | −0.288*** |

| (0.074) | (0.077) | (0.077) | |

| Born in the South | 0.504*** | 0.350*** | 0.350*** |

| (0.079) | (0.081) | (0.081) | |

| High school (ref. LTHS) | −0.872*** | −0.872*** | |

| (0.085) | (0.085) | ||

| Some college (ref. LTHS) | −1.473*** | −1.473*** | |

| (0.117) | (0.117) | ||

| College and above (ref. LTHS) | −1.805*** | −1.805*** | |

| (0.139) | (0.139) | ||

| Married at baseline | −0.164 | −0.164 | |

| (0.087) | (0.087) | ||

| Other family member deaths | 0.127 | −0.049 | −0.049 |

| (0.134) | (0.136) | (0.136) | |

| Age centered at 65 | 0.072*** | 0.065*** | 0.065*** |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |

| Constant | −4.974*** | −3.583*** | −3.584*** |

| (0.134) | (0.172) | (0.172) |

Note. LTHS = less than high school. Standard errors are presented in parentheses.

***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05.

Figure 1.

Predicted probability of dementia incidence by race and death of a child prior to midlife. Note: *** indicates significant difference in probability of dementia incidence between bereaved and nonbereaved parents, p < .001.

Hypothesis 2 (vulnerability)

We next consider the possibility that black parents might be more vulnerable than white parents to the effects of child loss. The interaction terms for child loss prior to midlife with race (Model 3, Table 2) are not statistically significant suggesting that, for parents who experience the death of a child prior to midlife, the estimated effect on dementia risk is similar for black parents and white parents. As an additional test, we considered the possibility of gender differences in the impact of child loss on dementia risk; this interaction (not shown) is not significant suggesting similar effects on mothers and fathers.

Hypothesis 3 (mechanisms of risk)

In Table 3, we consider whether (H3) death of a child by age 40 is associated with biosocial factors identified in prior research as increasing dementia risk; (H3a) death of a child by age 40 is more strongly associated with biosocial factors for black parents than for white parents; and (H3b) biosocial factors explain the association of child loss with dementia risk. Table 3 shows that, net of covariates, loss of a child prior to midlife is associated with the following biosocial factors assessed at baseline: less household income (Model 1, p < .001) and higher levels of psychological distress (Model 2, p < .001); greater odds of being a current smoker (Model 3, p < .05), nondrinker (Model 4, p < .001), or heavy drinker (Model 4, p < .01); higher BMI (Model 6, p <.05) and greater odds of reporting fair/poor health (Model 7, p <.001) and more cardiometabolic conditions (Model 8, p <.05). Overall, these results provide partial support for Hypothesis 3, with child loss prior to midlife associated with all of the biosocial factors except physical activity. Tests for interactions of race with child loss do not support Hypothesis 3a concerning race differences in the association of child loss with each of the possible biosocial factors (no interaction term was statistically significant; results not shown, available upon request).

Table 3.

Models Predicting Biosocial Factors Related to Dementia Risk by Death of a Child Prior to Midlife, Health and Retirement Study (N = 11,458)

| Smoking statusa | Drinking statusb | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household income | Psychological distress | Former smoker | Current smoker | Nondrinker | Heavy drinker | Vigorous physical activity | BMI | Fair/poor self-rated health | Cardio-metabolic conditions | |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | ||

| Parent bereaved by age 40 | −0.128*** | 0.317*** | 0.094 | 0.226* | 0.339*** | 0.359** | 0.077 | 0.468* | 0.287*** | 0.080* |

| (0.033) | (0.060) | (0.079) | (0.091) | (0.088) | (0.130) | (0.069) | (0.191) | (0.081) | (0.038) | |

| Non-Hispanic (NH) black | −0.419*** | 0.169*** | −0.151* | −0.105 | 0.075 | −0.271** | −0.383*** | 2.136*** | 0.464*** | 0.400*** |

| (0.025) | (0.046) | (0.061) | (0.070) | (0.064) | (0.104) | (0.055) | (0.148) | (0.062) | (0.028) | |

| Female | −0.087*** | 0.143*** | −0.759*** | −0.699*** | 0.469*** | −0.957*** | −0.203*** | −0.383*** | −0.100 | −0.201*** |

| (0.019) | (0.035) | (0.045) | (0.056) | (0.047) | (0.074) | (0.040) | (0.112) | (0.053) | (0.024) | |

| Born in the South | −0.059** | 0.114** | −0.089 | −0.004 | 0.470*** | 0.063 | −0.064 | −0.153 | 0.283*** | 0.125*** |

| (0.020) | (0.037) | (0.047) | (0.058) | (0.050) | (0.078) | (0.042) | (0.117) | (0.053) | (0.025) | |

| High schoolc | 0.438*** | −0.561*** | −0.299*** | −0.640*** | −0.348*** | −0.307* | 0.088 | −0.128 | −0.834*** | −0.125*** |

| (0.030) | (0.054) | (0.074) | (0.082) | (0.084) | (0.124) | (0.064) | (0.174) | (0.068) | (0.033) | |

| Some college | 0.718*** | −0.806*** | −0.200* | −0.807*** | −0.703*** | −0.483*** | 0.184** | −0.530** | −1.110*** | −0.165*** |

| (0.031) | (0.058) | (0.078) | (0.087) | (0.086) | (0.128) | (0.067) | (0.184) | (0.075) | (0.036) | |

| College and above | 1.132*** | −1.094*** | −0.587*** | −1.905*** | −1.052*** | −0.607*** | 0.422*** | −1.513*** | −1.898*** | −0.361*** |

| (0.032) | (0.059) | (0.079) | (0.101) | (0.087) | (0.128) | (0.069) | (0.190) | (0.093) | (0.039) | |

| Married at baseline | 0.677*** | −0.762*** | −0.237*** | −0.779*** | −0.029 | −0.193* | 0.275*** | −0.197 | −0.562*** | −0.064* |

| (0.023) | (0.042) | (0.056) | (0.064) | (0.057) | (0.090) | (0.049) | (0.134) | (0.057) | (0.028) | |

| Other family member | −0.040 | 0.074 | 0.190** | 0.125 | 0.125* | −0.070 | 0.063 | 0.491** | 0.181* | 0.210*** |

| Deaths | (0.026) | (0.049) | (0.063) | (0.074) | (0.063) | (0.090) | (0.056) | (0.155) | (0.077) | (0.038) |

| Age centered at 65 | −0.009*** | −0.026*** | 0.019*** | −0.060*** | 0.028*** | −0.006 | 0.028*** | −0.084*** | −0.016*** | 0.026*** |

| (0.001) | (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.004) | (0.006) | (0.003) | (0.009) | (0.004) | (0.002) | |

| Constant | 9.334*** | 2.198*** | 0.910*** | 0.564*** | 1.069*** | 0.096 | −0.335*** | 27.895*** | −0.540*** | −0.225*** |

| (0.044) | (0.081) | (0.109) | (0.124) | (0.114) | (0.168) | (0.094) | (0.259) | (0.113) | (0.055) |

Note. BMI = body mass index. Standard errors are presented in parentheses.

aReference category: nonsmoker.

bReference category: moderate drinker.

***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05.

Hypothesis 3b considers whether biosocial factors explain the association of child loss prior to midlife with dementia risk. Social, psychological, behavioral, and biological factors, respectively, are presented separately in Models 1–4 of Table 4. Model 1 shows that higher levels of income (p < .001) are associated with lower dementia risk. However, the association of child loss prior to midlife with increased dementia risk remains statistically significant after accounting for income (p < .05). Model 2 shows that, while psychological distress (CES-D scores) is associated with increased dementia risk (p < .001), the estimated effect of child loss prior to midlife on dementia remains significant (p < .05). Similarly, Model 3 shows that child loss by age 40 remains a significant predictor of dementia (p < .05) even with inclusion of health behavior variables, though current smokers (p < .01), nondrinkers (p < .01), and heavy drinkers (p < .05) have increased dementia risk, and those who engage in vigorous physical activity are at lower risk for dementia (p < .05). Model 4 shows that higher levels of BMI, a possible biological mechanism, are associated with lower dementia risk (p < .01), but self-reported fair/poor health and more cardiometabolic conditions are associated with higher dementia risk (p < .001). The finding for BMI is consistent with recent studies showing that although BMI is positively associated with risk at younger ages, this pattern is reversed at older ages (Kivimäki et al., 2018). The association between child loss by age 40 with dementia risk remains significant after controlling for BMI, self-rated health, and cardiometabolic conditions. The final Model 5 includes the full set of covariates and biosocial variables considered jointly. The association of child loss prior to midlife with dementia risk is no longer significant in this final model. Thus, the full set of biosocial variables considered together accounts for the significant association of child loss with dementia risk, providing support for Hypothesis 3b.

Table 4.

Multinomial Logistic Regression Predicting Dementia Incidence by Death of a Child Prior to Midlife, Health and Retirement Study, 2000 to 2014 (N = 11,458)

| Dementia vs nondementia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 |

| Parent bereaved by age 40 | 0.250* | 0.242* | 0.270* | 0.236* | 0.206 |

| (0.107) | (0.107) | (0.107) | (0.107) | (0.107) | |

| Non-Hispanic (NH) black | 0.754*** | 0.843*** | 0.858*** | 0.815*** | 0.766*** |

| (0.089) | (0.088) | (0.088) | (0.089) | (0.089) | |

| Female | −0.327*** | −0.325*** | −0.298*** | −0.255** | −0.318*** |

| (0.078) | (0.077) | (0.080) | (0.078) | (0.082) | |

| Born in the South | 0.309*** | 0.327*** | 0.315*** | 0.265** | 0.211* |

| (0.081) | (0.081) | (0.081) | (0.081) | (0.082) | |

| High school (ref. LTHS) | −0.765*** | −0.799*** | −0.842*** | −0.743*** | −0.634*** |

| (0.085) | (0.085) | (0.085) | (0.086) | (0.086) | |

| Some college (ref. LTHS) | −1.275*** | −1.356*** | −1.417*** | −1.304*** | −1.094*** |

| (0.119) | (0.118) | (0.118) | (0.119) | (0.120) | |

| College and + (ref. LTHS) | −1.494*** | −1.650*** | −1.700*** | −1.572*** | −1.241*** |

| (0.142) | (0.141) | (0.141) | (0.142) | (0.146) | |

| Married at baseline | 0.068 | −0.039 | −0.117 | −0.090 | 0.177 |

| (0.091) | (0.088) | (0.088) | (0.087) | (0.093) | |

| Other family member deaths | −0.100 | −0.031 | −0.035 | −0.099 | −0.102 |

| (0.136) | (0.136) | (0.136) | (0.136) | (0.137) | |

| Household income (Ln) | −0.302*** | −0.240*** | |||

| (0.029) | (0.031) | ||||

| Psychological distress | 0.151*** | 0.085*** | |||

| (0.017) | (0.019) | ||||

| Former smoker (ref. nonsmoker) | 0.077 | −0.001 | |||

| (0.085) | (0.086) | ||||

| Current smoker (ref. nonsmoker) | 0.316** | 0.193 | |||

| (0.101) | (0.104) | ||||

| Nondrinker (ref. MD) | 0.327** | 0.246* | |||

| (0.105) | (0.106) | ||||

| Heavy drinker (ref. MD) | 0.299* | 0.272 | |||

| (0.151) | (0.152) | ||||

| Vigorous physical activity | −0.177* | −0.014 | |||

| (0.075) | (0.078) | ||||

| BMI | −0.019** | −0.018* | |||

| (0.007) | (0.007) | ||||

| Fair/poor self-rated health | 0.775*** | 0.557*** | |||

| (0.083) | (0.089) | ||||

| Cardiometabolic conditions | 0.150*** | 0.129** | |||

| (0.043) | (0.043) | ||||

| Age centered at 65 | 0.066*** | 0.070*** | 0.067*** | 0.067*** | 0.072*** |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |

| Constant | −0.755* | −3.999*** | −3.937*** | −3.477*** | −1.687*** |

| (0.314) | (0.181) | (0.207) | (0.256) | (0.414) |

Note. BMI = body mass index; LTHS = less than high school; MD = moderate drinker. Models also account for sample attrition due to mortality and dropout (available upon request). Standard errors are presented in parentheses.

***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05.

Sensitivity Checks

As a sensitivity check, we explored alternative approaches to measuring both dementia risk and child loss. Because proxy reports of dementia are especially reliable in the HRS, we conducted all analyses using only proxy reports; the pattern of results was consistent with those presented above. We also used an alternative approach to assess child loss, based on number of live births relative to number of living children in the total HRS sample assessed from 1996 to 2014. A consistent pattern of results across measures suggests a robust association of child loss prior to midlife with dementia risk, and racial disadvantage therein.

Discussion

The death of a child is a traumatic and stressful life event for parents and is more common than most Americans realize. Estimates based on the HRS sample indicate that about 8.5% of HRS parents had lost a child by age 40, and about 13% report having ever lost a child. These estimates, however, understate the extent of loss for black parents. Black parents are twice as likely as white parents to have lost a child by midlife, and this disparity increases with advancing age (Umberson et al., 2017). Moreover, stress has been implicated as contributing to increased risk of dementia (Forrester et al., 2018; Greenberg et al., 2014; Peavy et al., 2012). In this study, we hypothesized that the death of a child prior to midlife is a stressful life event that adds to dementia risk from mid to later life, and our results strongly support this hypothesis.

Very few studies have considered how the death of a family member might affect subsequent dementia risk, and prior studies that have addressed the death of other family members in relation to dementia have been based on white populations (e.g., Gerritsen et al., 2017; Norton et al., 2009; Vidarsdottir et al., 2014), failing to consider the racialized context of family member loss and of dementia risk in the United States. Our results suggest that the association of the loss of a child with dementia risk is similar for black and white parents. However, this finding should not distract from the substantial disadvantage associated with race. Black parents are much more likely to lose a child and the death of a child adds to the already higher risk of developing dementia for black Americans. Indeed, our findings suggest that race and the death of a child have independent and additive effects on dementia risk. These findings contribute to a growing literature documenting that black Americans face more stress throughout the life course than do whites (e.g., Williams, 2018), and that race-related stress may contribute to dementia risk (Forrester et al., 2018; Zahodne et al., 2019). The results of the present study suggest that the death of a child by age 40—which certainly reflects structural racism and its effects on life expectancy in the United States—is a life course trauma that adds significantly to the greater stress burden of black Americans and increases dementia risk. Future studies should examine how multiple family member losses, and the timing of those losses, from childhood (e.g., early loss of parents and siblings) through midlife (e.g., spouses, children) may add to racial disparities in dementia risk later in life (Umberson, 2017).

We also considered a number of biosocial factors that might be associated with experiencing the death of a child and potentially increase dementia risk. We find that the death of a child prior to midlife is associated with lower levels of household income, more psychological distress, more smoking and heavy drinking, poorer self-rated health, higher BMI, and more cardiometabolic conditions by midlife—factors that have been associated with dementia risk in prior studies (Babulal et al., 2019; Glymour & Manly, 2008; Kivimäki et al., 2018; St. John & Montgomery, 2013). The association of child death with subsequent dementia risk is no longer statistically significant after inclusion of the full set of biosocial measures is taken into account, suggesting that the death of a child adds to dementia risk by activating biosocial risk factors (e.g., depression, heavy drinking, cardiometabolic conditions) that increase the probability of developing dementia over time. Contrary to expectations, we found no evidence for race differences in the impact of loss on biosocial factors. It may be that, for any parent who loses a child, the trauma is so great that it activates numerous and intersecting biosocial processes. Alternatively, there may be processes of sample selectivity, inadequate measurement of risk factors, or yet to be discovered risk factors that mask race differences in these processes. Due to HRS data limitations, we were not able to follow individuals after child loss but prior to enrollment in the HRS at midlife; it is possible that black parents, who are more likely than white parents to experience loss, are also more likely to die or drop out of the HRS. Future research should direct more attention to the life course timing of loss in relation to the unfolding and inter-related biosocial processes that unfold over time and increase dementia risk across diverse populations.

While this study draws on the rich HRS sample to provide population-level estimates of the link of child loss prior to midlife with subsequent dementia risk, limitations must be noted. First, we limit our sample to non-Hispanic black parents and non-Hispanic white parents. The HRS does not include enough individuals in most racial/ethnic groups to permit additional comparisons. Although the HRS includes a sizable number of Latinos, results may be difficult to interpret with these data because a significant portion of older Latinos in the HRS are foreign-born adults who experienced different mortality environments (Viner et al., 2011). Previous studies have found Hispanic Americans to be at higher risk of developing dementia compared with non-Hispanic white Americans (Garcia et al., 2017). Therefore, future work should consider how child loss affects dementia risk for Latinos in the United States. Second, HRS questions about the death of a child ask only about the “most recent” loss and some respondents may have lost more than one child; thus, if respondents experienced a loss before age 40 as well as a loss after age 40, they would not be coded as having lost a child before age 40. Misclassification might then lead to underestimation of effects of loss on dementia risk. Future research should also consider the cause of a child’s death, information not available in the HRS. Black youth and young adults who die are more likely than their white counterparts to die as a result of homicide (Khan et al., 2018), and prior research on bereavement shows that violent and unexpected deaths have stronger adverse effects following loss (Stroebe et al., 2007). Third, as our concern is with the most severe consequences of child loss, we focus on dementia as the primary dependent variable rather than focusing on other measures of cognitive functioning (e.g., mild cognitive impairment). Measurement of dementia in the HRS is also more reliable than measures of cognitive impairment with no dementia (Crimmins et al., 2011). We conducted an additional analysis of the association of child loss before age 40 with cognitive impairment, no dementia (CIND) and found that death of a child before age 40 was not associated with increased risk of CIND. Future research might consider trajectories of cognitive decline following bereavement, especially in relation to progression to dementia.

Future research should assess both the short- and long-term consequences of loss on other cognitive outcomes to identify who is most at risk of advancing to dementia as well as factors that may be protective against future dementia onset. Greene and colleagues (2014) found an accelerated rate of cognitive decline for white parents who lost a child before age 31 but only for those with an APOE ε4 allele and no subsequent births. It should also be noted that some of the biosocial mechanisms of risk evaluated in our analysis (e.g., psychological distress, heavy drinking, poor health) might interfere with the ability to focus or concentrate on testing, and that measures of dementia status may operate differently across racial/ethnic groups (Babulal et al., 2019; Blazer et al., 2015; Glymour & Manly, 2008). Finally, the HRS did not include the measure of timing of child loss until 2004, which means that older birth cohorts (specifically the HRS and WB cohorts) had to survive until at least 2004 to be included in the study. Thus, selective survival, especially for black Americans who have lower life expectancy than whites, may attenuate estimates of risk with advancing age (Mayeda et al., 2016). Such selectivity would likely result in underestimation of dementia risk. Regardless of these constraints, the present results suggest that child loss before midlife elevates the risk of dementia incidence in mid to later life through biosocial pathways, with more disadvantage for black Americans due to their independent elevated risks of dementia and of losing a child.

Conclusion

Dementia is associated with increased demands for medical and personal care as well as premature death, and this burden is borne more heavily by black than white Americans (Alzheimer’s Association, 2019; Blazer et al. 2015). Our results strongly suggest that experiencing the death of a child by midlife is a life course turning point that increases risk for developing dementia. These findings underscore the importance of identifying parents who have lost a child and of early intervention strategies to reduce long-term risk for bereaved parents, perhaps by targeting the specific biosocial factors most strongly triggered by loss and known to increase dementia risk (e.g., depression, cardiometabolic conditions). Attention to specific life course turning points associated with later life dementia may provide the impetus to dedicate resources to specific and modifiable risk and protective factors for dementia earlier in the life course (James & Bennett, 2019), and that may vary across racial groups in the United States (Glymour & Manly, 2008); this approach should recognize that effective interventions must also address barriers to screening and treatment that are greater for black Americans. Although more challenging to address, premature mortality of Americans, especially black Americans, is at the heart of the matter. Black Americans already face an elevated risk of developing dementia and this risk is further compounded by their disproportionate exposure to child loss. Future research should further consider how race differences in exposure to and timing of other family member deaths across the life course may contribute to and compound racial disparities in dementia risk (Umberson, 2017). The public health conversation about dementia should include discussion of racial disparities in earlier life course experiences of loss, and emphasize that these losses are linked to racial disparities in U.S. life expectancy that begin in infancy.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01AG054624 and R01 AG054624-01A1S); and Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P2C HD042849 and T32 HD00708).

Author Contributions

D. Umberson planned the study, supervised data analysis, and wrote the article with input from all authors. R. Donnelly assisted with writing, supervision of data analysis, and revising the article. M. Xu and M. Farina performed statistical analyses and contributed to revising the article. M. A. Garcia assisted with revising the article.

References

- Allison P. D. (2010). Survival analysis using SAS: A practical guide (2nd ed.). Cary, North Carolina: SAS Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2019). Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 15(3), 321–387. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2019.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babulal G. M., Quiroz Y. T., Albensi B. C., Arenaza-Urquijo E., Astell A. J., Babiloni C., … O’Bryant S. E (2019). Perspectives on ethnic and racial disparities in Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias: Update and areas of immediate need. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 15(2), 292–312. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2018.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer D. G., Yaffe K., & Liverman C. T. (Eds.). (2015). Cognitive aging: Progress in understanding and opportunities for action. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/21693 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chêne G., Beiser A., Au R., Preis S. R., Wolf P. A., Dufouil C., & Seshadri S (2015). Gender and incidence of dementia in the Framingham Heart Study from mid-adult life. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 11(3), 310–320. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2013.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crimmins E. M., Kim J. K., Langa K. M., & Weir D. R (2011). Assessment of cognition using surveys and neuropsychological assessment: The Health and Retirement Study and the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66(Suppl. 1), i162–171. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbr048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dassel K. B., Carr D. C., & Vitaliano P (2017). Does caring for a spouse with dementia accelerate cognitive decline? Findings from the health and retirement study. The Gerontologist, 57, 319–328. doi:10.1093/geront/gnv148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman K. L., & Birditt K. S (2011). Relationships between adults and their aging parents. In Schaie K. W. & Willis S. L. (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of aging (7th ed., pp. 219–232). San Diego: Academic Press. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-380882-0.00014-0 [Google Scholar]

- Forrester S. N., Gallo J. J., Whitfield K. E., & Thorpe R. J (2018). A framework of minority stress: From physiological manifestations to cognitive outcomes. The Gerontologist, 59( 6), 1017–1023. doi:10.1093/geront/gny104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia M. A., Downer B., Chiu C.-T., Saenz J. L., Rote S., & Wong R (2017). Racial/ethnic and nativity differences in cognitive life expectancies among older adults in the United States. The Gerontologist, 59( 2), 281–289. doi:10.1093/geront/gnx142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen L., Wang H.-X., Reynolds C. A., Fratiglioni L., Gatz M., & Pedersen N. L (2017). Influence of negative life events and widowhood on risk for dementia. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(7), 766–778. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2017.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilsanz P., Mayeda E. R., Glymour M. M., Quesenberry C. P., & Whitmer R. A (2017). Association between birth in a high stroke mortality state, race, and risk of dementia. JAMA Neurology, 74(9), 1056–1062. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.1553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glymour M. M., & Manly J. J (2008). Lifecourse social conditions and racial and ethnic patterns of cognitive aging. Neuropsychology Review, 18(3), 223–254. doi:10.1007/s11065-008-9064-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene D., Tschanz J. T., Smith K. R., Ostbye T., Corcoran C., Welsh-Bohmer K. A., … Cache County Investigators. (2014). Impact of offspring death on cognitive health in late life: The Cache County Study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 22(11), 1307–1315. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2013.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg M. S., Tanev K., Marin M.-F., & Pitman R. K (2014). Stress, PTSD, and dementia. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 10(3 Suppl.), S155–S165. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2014.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James B. D., & Bennett D. A (2019). Causes and patterns of dementia: An update in the era of redefining Alzheimer’s disease. Annual Review of Public Health, 40, 65–84. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S. Q., Berrington de Gonzalez A., Best A. F., Chen Y., Haozous E. A., Rodriquez E. J., … Shiels M. S (2018). Infant and youth mortality trends by race/ethnicity and cause of death in the United States. JAMA Pediatrics, 172(12), e183317. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.3317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivimäki M., Luukkonen R., Batty G. D., Ferrie J. E., Pentti J., Nyberg S. T., … Jokela M (2018). Body mass index and risk of dementia: Analysis of individual-level data from 1.3 million individuals. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 14(5), 601–609. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2017.09.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langa K. M., Larson E., Crimmins E., Faul J, Levine D., Kabeto M., & Weir D (2017). A comparison of the prevalence of dementia in the United States in 2000 and 2012. JAMA Internal Medicine, 177(1), 51–58. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langa K. M., Larson E. B., Karlawish J. H., Cutler D. M., Kabeto M. U., Kim S. Y., & Rosen A. B (2008). Trends in the prevalence and mortality of cognitive impairment in the United States: Is there evidence of a compression of cognitive morbidity? Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 4(2), 134–144. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2008.01.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langa K. M., Weir D. R., Kabeto M., & Sonnega A (2018). Langa-Weir classification of cognitive function (1995 Onward). Ann Arbor, Michigan: Institute for Social Research. [Google Scholar]

- Lin J. C., Guerrieri J. G., & Moore A. A (2011). Drinking patterns and the development of functional limitations in older adults: Longitudinal analyses of the health and retirement survey. Journal of Aging and Health, 23(5), 806–821. doi:10.1177/0898264310397541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Zhang Z., Choi S., & Langa K.M (2019). Marital status and dementia: Evidence from the Health and Retirement Study. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbz087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayeda E. R., Glymour M. M., Quesenberry C. P., & Whitmer R. A (2016). Inequalities in dementia incidence between six racial and ethnic groups over 14 years. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 12(3), 216–224. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2015.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen B. S. (2007). Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: Central role of the brain. Physiological Reviews, 87(3), 873–904. doi:10.1152/physrev.00041.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X., & D’Arcy C (2012). Education and dementia in the context of the cognitive reserve hypothesis: A systematic review with meta-analyses and qualitative analyses. PLoS One, 7(6). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton M. C., Østbye T., Smith K. R., Munger R. G., & Tschanz J. T (2009). Early parental death and late-life dementia risk: Findings from the Cache County Study. Age and Ageing, 38(3), 340–343. doi:10.1093/ageing/afp023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peavy G. M., Jacobson M. W., Salmon D. P., Gamst A. C., Patterson T. L., Goldman S., … Galasko D (2012). The influence of chronic stress on dementia-related diagnostic change in older adults. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 26(3), 260–266. doi:10.1097/WAD.0b013e3182389a9c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson R. L., Fain M. J., Butler E. A., Ehiri J. E., & Carvajal S. C (2019). The role of social and behavioral risk factors in explaining racial disparities in age-related cognitive impairment: A structured narrative review. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition, 1–24. doi:10.1080/13825585.2019.1598539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravona-Springer R., Beeri M. S., & Goldbourt U (2012). Younger age at crisis following parental death in male children and adolescents is associated with higher risk for dementia at old age. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders, 26(1), 68. doi:10.1097/WAD.0b013e3182191f86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers C. H., Floyd F. J., Seltzer M. M., Greenberg J., & Hong J (2008). Long-term effects of the death of a child on parents’ adjustment in midlife. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(2), 203–211. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers R. G., Hummer R. A., Krueger P. M., & Vinneau J. M (2019). Adult mortality. In Poston D. Jr., (Ed), Handbook of population (pp. 355–381). Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Smith K. R., Hanson H. A., Norton M. C., Hollingshaus M. S., & Mineau G. P (2014). Survival of offspring who experience early parental death: Early life conditions and later-life mortality. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 119, 180. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.11.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St John P., & Montgomery P (2013). Does self-rated health predict dementia? Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 26, 41–50. doi:10.1177/0891988713476369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffick D. E. (2000). Documentation of affective functioning measures in the Health and Retirement Study. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M., Schut H., & Stroebe W (2007). Health outcomes of bereavement. Lancet (London, England), 370, 1960–1973. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61816-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D. (2017). Black deaths matter: Race, relationship loss, and effects on survivors. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 58, 405–420. doi:10.1177/0022146517739317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D., Olson J. S., Crosnoe R., Liu H., Pudrovska T., & Donnelly R (2017). Death of family members as an overlooked source of racial disadvantage in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114(5), 915. doi:10.1073/pnas.1605599114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdery A. M., & Margolis R (2017). Projections of white and black older adults without living kin in the United States, 2015 to 2060. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114(42), 11109–11114. doi:10.1073/pnas.1710341114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidarsdottir H., Fang F., Chang M., Aspelund T., Fall K., Jonsdottir M. K., … Valdimarsdottir U (2014). Spousal loss and cognitive function in later life: A 25-year follow-up in the AGES-Reykjavik study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 179(6), 674–683. doi:10.1093/aje/kwt321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viner R. M., Coffey C., Mathers C., Bloem P., Costello A., Santelli J., & Patton G. C (2011). 50-year mortality trends in children and young people: A study of 50 low-income, middle-income, and high-income countries. Lancet (London, England), 377, 1162–1174. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60106-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T.-Y., Wei H.-T., Liou Y.-J., Su T.-P., Bai Y.-M., Tsai S.-J., … Chen M.-H (2016). Risk for developing dementia among patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: A nationwide longitudinal study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 205, 306–310. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield K., & Baker T (2013). Handbook of minority aging. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R. (2018). Stress and the mental health of populations of color: Advancing our understanding of race-related stressors. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 59(4), 466–485. doi:10.1177/0022146518814251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., Lawrence J. A., & Davis B. A (2019). Racism and health: Evidence and needed research. Annual Review of Public Health, 40( 1), 105–125. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahodne L. B., Sol K., & Kraal Z (2019). Psychosocial pathways to racial/ethnic inequalities in late-life memory trajectories. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 74(3), 409–418. doi:10.1093/geronb/gbx113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Hayward M. D., & Yu Y. L (2016). Life course pathways to racial disparities in cognitive impairment among older Americans. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 57, 184–199. doi:10.1177/0022146516645925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]