Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has presented practitioners of applied behavior analysis (ABA) with new and uncharted challenges. Upholding ethical responsibilities while navigating an international public health crisis has opened areas of uncertainty that have no precedent. Although there is general guidance on how to respond ethically from the Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB) in their publication specific to the COVID-19 crisis (BACB, 2020, March 29, Ethics Guidance for ABA Providers During COVID-19 Pandemic, retrieved from https://www.bacb.com/ethics-guidance-for-aba-providers-during-covid-19-pandemic-2/), there remains a huge responsibility on the individual practitioner to make potentially life-changing decisions. In that regard, practitioners are urged to ensure that they rely on socially significant and valid decision-making processes. The goal of this article is to provide an exercise in accounting for stakeholder feedback and connecting with patients and families regarding their input on the acceptability of treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. The exercise is in the form of a structured parent interview to help practitioners account for the setting variables and social validity of treatment during a crisis. It is our ethical responsibility to remember this critical dimension of our science and practice.

Keywords: Autism, Clinical decision making, Consumer feedback, COVID-19, Social significance, Social validity

In March 2020, many states across the nation were instructed to systematically implement a shelter-in-place order outlined by each state’s government and with the guidance of the president of the United States. This was a result of the novel coronavirus that began to spread across the nation and take the lives of people who were considered vulnerable. Practitioners in the various essential services were left with the task of navigating their practice. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB) released general guidance on professional and ethical behavior during the crisis (BACB, 2020). In addition to this professional guidance, Behavior Analysis in Practice (BAP) established the COVID-19 Emergency Publication Series. Many articles focused on providing guidance to behavior analysts on how to continue their practice by, for example, maintaining treatment integrity (Rodriguez, 2020), using telehealth (Yi & Dixon, 2020), and applying decision-making models (Colombo et al., 2020; Cox, Plavnick, & Brodhead, 2020). Although these articles in combination do an excellent job of presenting solid frameworks for difficult decision making, they focus on a clinical framework and technical issues. In this article, we propose that one element of the decision-making process has been neglected: that of including consumer/stakeholder feedback. We will propose suggestions for including this aspect to complete the entire picture for the process of clinical decision making around client services.

In 2020, LeBlanc mentored readers to think about big ideas that “spark reactions from the reader, stimulate new areas of exploration, and inspire other ideas” (p. 7). As evidenced by the approximately 13 articles in the BAP Emergency Publication Series that were published in a relatively short period of time, our field has some big ideas. Although our topic is not a new area of exploration, we feel that the area of considering feedback from stakeholders as an aspect of social validity is often overlooked. Baer, Wolf, and Risley (1968, 1987) introduced and described seven dimensions of applied behavior analysis (ABA), and included among them was a greater concern for problems of social importance. Montrose Wolf (1978) expanded this concept of social validity in his keystone article, charging future practitioners to embrace this aspect of our practice as vital to the progress of the field. Of the articles in the BAP Emergency Publication Series, two of these specifically addressed social validity (i.e., Espinosa, Metko, Raimondi, Impenna, & Scognamiglio, 2020; Moran & Ming, 2020). The current article is explicitly focused on expanding the concept of consumer feedback and participation in clinical decision making.

A Word on Terminology

In 1991, the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis published an entire issue dedicated to the discussion of social validity. In this issue, it was noted that “consumers have always played a role in applied behavior analysis” (Schwartz, 1991, p. 241). Baer et al. (1968) included, while introducing the basic tenets of ABA, the need to examine “behaviors which are socially significant, rather than convenient for study” (p. 92). Many publications have used the terms social validity, social importance, and social significance somewhat interchangeably (Fawcett, 1991; Schwartz & Baer, 1991; Wolf, 1978). The bleed between the terms is completely understandable, as they all point to common ground in understanding the vital role of how ABA services are interpreted by those they are intended to support. For further clarification, this article seeks to emphasize a difference between the terms social significance and social validity. We argue that social significance is a broader term that implies general acceptability in a societal framework. A Google search for a generic definition of the phrase social significance generated meanings for social and significance, but guidance on a generally accepted definition was found to simply indicate “significance for society, or important to society” (https://forum.wordreference.com).

In contrast to social significance, the term social validity has presented a more precise definition. Broadly defined, social validity concerns the appropriateness and acceptability of ABA interventions as both process and outcome measures (Kazdin, 1977; Wolf, 1978). Several tools have been developed within the field of ABA for measuring social validity. The fact that we have tools for measuring social validity (but no tools for measuring social significance) indicates one difference between the terms: the capability for measurement and evaluation. Given that consumer feedback has been established in the literature as one of the factors considered in social validity, we will adopt this term for use in this article as it relates to this discussion. The authors put this forward to (a) more clearly differentiate between these crucial terms and (b) highlight the more functional defining features of social validity, which, by definition, necessitate a reliance on a structured and ongoing consumer-feedback process. We further assert that this process may often be lacking given the dearth of available systematized patient-informed models for navigating a comprehensive client progression of services.

A Brief Review of Social Validity

In the 1970s, two paramount articles appeared on the topic of social validity. Kazdin (1977) and Wolf (1978) explored the importance of social validity to the, at the time, new field of ABA. Montrose Wolf’s (1978) article, in particular, spoke to the importance of consumer feedback as we attempt to create socially significant treatments. Through these efforts, social validity was conceptualized on three levels: (a) the social importance of the behaviors to change, (b) the processes or procedures that are implemented, and (c) the outcomes on the society/community at large. Social validity and consumer input have to do with the first of these, the social importance of behaviors to change, and the last, meaningful consideration of the outcomes to consumers (i.e., society). Further insight into consumer behavior and its relationship to social validity is provided in an article by Ilene Schwartz (1991) titled “The Study of Consumer Behavior and Social Validity: An Essential Partnership for Applied Behavior Analysis.” This article suggested how very intimately ABA services are tied to consumer education and satisfaction and that our conceptualization of social validity had a great deal to do with this consumer behavior chain.

As practitioners, we find ourselves providing services during a pandemic, and many families receiving ABA services have experienced some level of change or pause in the delivery of treatment. The temporary change or pause of ABA service delivery presents the unique opportunity to collaborate with patients and their families to assess the validity of our interventions. The recipients of ABA services ultimately decide the utility and importance of treatment. Research has shown that families with children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) undergo more stress than families with children with other developmental disabilities (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Hayes & Watson, 2013). Those stresses can be compounded by additional factors during times of crisis, such as stress related to employment, housing, and education (Coyne et al., 2020). For our interventions to be effective, they must be implemented and maintained. Therefore, social validity is an important and necessary piece in the continuation of treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic: “It seems that if we aspire to social importance, then we must develop systems that allow our consumers to provide us feedback about how our applications relate to their values, to their reinforcers” (Wolf, 1978, p. 213).

Although ABA services are deemed medically necessary for those diagnosed with ASD and related disorders, the value and reinforcing properties of treatment for clients and families may change during this pandemic and/or during any natural disaster. The Association of Professional Behavior Analysts offered crisis guidelines in April 2020 with considerations specifically oriented to situations such as the one at hand. The Council of Autism Service Providers (2020) followed with similar materials. This information emphasized how a crisis necessitates a potential change in the intensity and format of service delivery, likely requiring increased caregiver involvement given the potential decreases in available essential workers due to the increased risk of exposure to the virus to all involved stakeholders. These changes are exactly what must be addressed with our ongoing evaluation of consumer feedback in regard to clinical decision making.

With COVID-19 here for longer than first anticipated, the examination of our interventions based on a complete consideration of social validity is warranted. The purpose of our article is to inspire the practitioner to continually assess for social validity by means of consumer feedback, throughout treatment, especially during times of uncertainty such as the COVID-19 pandemic. We will review some social validity tools for context and offer an exercise in the form of a structured interview—that is, a method to assess the value of ongoing interventions. With some modification, this exercise can be used not just during a time of crisis, but throughout intervention as a prompt to continually contrive discussions that make the social validity of ABA treatment to each individual patient and familial network a foundation of our interventions.

Social Validity Tools

Fairly recent review articles are available on the prevalence of social validity within published articles in behavior-analytic journals and journals closely associated with the practice of ABA (Carr, Austin, Britton, Kellum, & Bailey, 1999; Ferguson et al., 2019; Kennedy, 1992). The findings in each of these reviews were remarkably similar: treatment outcome and acceptability measures were reported in only about 12%–13% of published articles (Carr et al., 1999; Ferguson et al., 2019). In a different review, Park and Blair (2019) examined reports of social validity measures for behavioral interventions with young children. Twenty-eight studies published between 2001 and 2018 were included in their analysis. Their findings suggested improvements in three primary areas: (a) promoting implementation fidelity to improve social validity outcomes, (b) improving guidelines for timing and frequency of social validity assessment, and (c) working toward the development of social validity assessment tools designed to assess goals, procedures, and outcomes (Park & Blair, 2019). Although it is not the goal of this article to do an exhaustive review of all social validity measures available, for the purpose of providing context, we briefly review some notable, published social validity tools.

It comes as no surprise that Kazdin (1977) was the first to develop a tool, known as the Treatment Evaluation Inventory (TEI), to assess these components of social validity. The TEI is a subjective assessment that contains 15 questions answered on a 7-point Likert-type scale that was developed for parents to fill out on the treatment modality used for their children with behavior disorders. The TEI distinguishes various interventions by weighting the acceptability of each intervention. Kazdin (1977) chose the use of a subjective measure that aligned with Wolf’s (1978) argument that subjective measurements are more appropriate to assess social validity because society’s values or social acceptance is itself subjective. The tool was found to be an effective measure and is still commonly used today for acceptability studies (Miltenberger, 1990). A modified version of the subjective TEI also commonly used in research was introduced by Kelley, Heffer, Gresham, and Elliott (1989). Kelley et al. developed a shorter version, referred to as the Treatment Evaluation Inventory–Shortened Form (TEI-SF), that included nine items in the questionnaire with a 5-point Likert-type scale found to weigh heavily on the measurement of acceptability, but also additionally weighted ethical issues/discomfort. The shorter version yielded results similar to the original TEI in differentiating treatments and was reported to be more user friendly (i.e., shorter, easier to complete, and more preferred by the rater; Miltenberger, 1990). A third tool was introduced by Reimers and Wacker (1988) and later revised by Reimers, Wacker, and Cooper (1991), titled the Treatment Acceptability Rating Form (TARF and TARF–Revised, respectively). This form is also a questionnaire that uses a 7-point Likert-type scale developed to simulate the TEI, but it is more applicable to the clinical setting in that it also assesses concerns with treatment procedures, costs, problem severity, perceived effectiveness, and understanding of the treatment (Miltenberger, 1990).

Most tools have been developed to be a similarly subjective questionnaire with a Likert-type scale completed by either the parent or teacher. The Intervention Rating Profile (IRP; Tarnowski & Simonian, 1992) and the IRP-15 (a brief version of the IRP; Martens, Witt, Elliott, & Darveaux, 1985) are commonly used in educational settings; assess acceptability, risks to the client, length of treatment, and effects on the teacher and other children; and are completed by teachers in the classroom setting. The Behavior Intervention Rating Scale (Elliott and Treuting, 1991) is a modification of the IRP-15 and assesses the same components as the IRP. The Abbreviated Acceptability Rating Profile (Tarnowski & Simonian, 1992) is another modification of the IRP-15; however, is uses parents as the raters. Lastly, only one tool that was found uses the child or student as the rater: the Children’s Intervention Rating Profile (CIRP; Witt & Elliott, 1985). The CIRP is an additional modification of the IRP that assesses for fairness and the expected effectiveness of treatment.

In a more recent development, Kennedy (2002) proposed that measuring the maintenance of behavior change is an important indicator for evaluating social validity. Recognizing maintenance as an important variable to examine in social validity measurement helped develop a more complete view of what social significance entails. Having more tools that are designed to examine different aspects of social validity is a necessary step in the evolution of paying more attention to this somewhat neglected dimension of ABA. However, an organized method for obtaining information on the consumer experience to inform decisions regarding ABA services remains deficient.

ABA as Medical Necessity

Professionals and practitioners are now in general agreement that ABA is a medical necessity for ASD and related disorders; however, a larger emphasis has not yet been adequately placed on the less objective measures of treatment acceptance such as the “likeability” and “usability” of ABA interventions (Finn & Sladeczek, 1991). During a pandemic, as we are currently experiencing, this would be an even more critical component as we are suggesting less commonly implemented modalities of treatment such as determining the necessity of direct, face-to-face contact with clients versus telehealth sessions versus mitigating the risks and benefits of pausing intervention for an undetermined length of time. It is even more critical that our clients understand our interventions, accept the modality, find our interventions useful to the components of their lives that they are interested in changing, and can carry out our interventions with distance coaching in our absence.

Also pertinent to direct consumer feedback are issues such as new elements of interventions that may not have been relevant prior to this pandemic, such as wearing a face mask, learning to socially distance, and increasing handwashing. Recognizing the shift in what is important to a consumer in the ever-changing circumstances of our COVID-19 environment is a vital component of the regular and relevant assessment of interventions’ social significance. Moreover, the vast individual differences among families receiving ABA services are critical information to consider in clinical decision-making protocols. ABA has been a science of single-subject analysis and individualized treatment, so recommendations for general decision making in clinical practice during times of considerable environmental change cannot be considered best practice. A complete assessment is needed for clinical decision making when considering the medical necessity of ABA for individual clients, especially during a period of crisis.

We chose to use the general term consumer to refer to both an individual who receives ABA services and the caregivers and parents of those receiving ABA services because the caregivers are often receiving training themselves and are an active part of good intervention services. It is beyond the scope of this article to determine which words to use in reference to those who receive services, as it is a sidebar to the primary objective. The important point is the fact that the role of the caregiver/parent (hereafter referred to as caregiver) changed suddenly, without warning or preparation, and did so in a dramatic fashion when shelter-in-place orders were issued, schools closed, and many services related to and including ABA were disrupted. Soon after, many lost the ability to go to parks, movies, or recreational facilities. The usual expectation of the caregiver in ABA services is to attend trainings, participate in meetings, practice routines and targets, and perhaps collect data all while working hand in hand with trained providers. Under pandemic circumstances, parents of most children all over the country found themselves serving in the roles of teacher, counselor, principle, and nutritionist, and the list goes on. Many caregivers who had been accustomed to the support of ABA services experienced a drastic change, with all supports vanishing in some cases, creating a caregiver role that was not planned, was not reasonable, and in some cases, was not possible. This dramatic change in the culture contributes to the situational variables now facing both consumers and practitioners of ABA.

Consumer Behavior in ABA

Behavior analysts have been called on to increase clients’ input in the process of assessing social validity for over 40 years (Schwartz & Bear, 1991; Winett, Moore, & Anderson, 1991). As practitioners found themselves in the uncharted waters of serving clients during a pandemic, we have discovered an opportunity for assessing situational factors that affect social validity in our treatments. We have been cautioned about making blanket statements and assumptions about who and what kind of services are needed across the span of clientele who receive ABA services during the pandemic. However, consumers’ and clients’ participation in these significant decisions that directly impact them has been understated in the advice thus far. As consumers are a part of this decision-making process, a clinician’s attempt to reach a conclusion regarding service delivery that does not include the consumer’s meaningful input may violate one of our dearly held tenets of ABA: the social importance and social validity of our individualized services.

Hypothetical Case Study

In regard to the standard of properly assessing for individualized treatment, consider the hypothetical example of two different clients receiving ABA services. In our hypothetical scenario, our first client is a preverbal 6-year-old who is prone to severe behavior outbursts. The other is a 3-year-old who has beginning speech, emerging skills, and moderate tantrum behavior. At first glance, a practitioner may conclude that the 6-year-old is in greater need of receiving services than the 3-year-old, and if resources are scarce, the practitioner may arrange them accordingly. However, all the situational variables must be examined as part of this decision-making process. In considering the broader context, the practitioner finds that the 6-year-old lives in a household with two parents who have both had the opportunity to participate in parent training and have been in ABA services for more than 3 years. However, our hypothetical practitioner also learns that the 3-year-old resides in a single-parent household and has had ABA services for only a few months. Additionally, the single mother is going through a divorce, has not yet been able to access any parent training, is trying to work from home during the COVID-19 pandemic, and has little time to act in the role of treatment provider for her 3-year-old child. It could be assumed that, between our hypothetical clients, the value and importance of treatment might be vastly different. With so much pressure on practitioners to make careful decisions about treatment during a time of crisis, it is very challenging to consider all relevant variables. Utilizing a tool designed for accessing information about these kinds of setting factors may be of great benefit. As earlier reviewed, the commonly used social validity tools target specific treatment procedures and big-picture issues such as overall cost and feasibility (Reimers & Wacker, 1988). Thus, the existing tools for social validity do not assess the importance of the treatment procedures to the family as they do not consider the set of factors presented by the pandemic in the family’s life at home. It was for these reasons that the authors developed an exercise that would capture the value of our treatment delivery in the home and community setting during a crisis.

Development of the Consumer Feedback Exercise

Stephen Fawcett (1991) proposed some methodological considerations for social validity in the field of ABA. Fawcett (1991) referred to the process of examining social validity in terms of considering the social significance of goals, the social appropriateness of procedures, and the social importance of effects. To unpack what is meant by “social importance of effects,” Fawcett proposed three levels: proximal, intermediate, and distal. Proximal effects are discrete measures of specific skills, such as the increased occurrence of a social greeting. This type of measure would be part of ongoing data collection in any good intervention system. Intermediate effects are those that relate to the main domain goals, such as social skill improvement with peers. Distal effects of an intervention are those related to big-picture goals, such as making more friends and enjoying more social time with others. Fawcett recommended assessing interventions at each level for a complete social validity measure.

In order to assess social validity during the pandemic, we must solicit input from our clients and their families. As Schwartz (1991) confirmed, “most social validity assessments still ask consumers to rate only program characteristics” (p. 242). Program characteristics in Fawcett’s (1991) system relate to proximal effects. Schwartz (1991) continued: “Answers to questions about situational variables, consumer characteristics and environmental factors might improve the accuracy of these assessments” (pp. 242–243). In the review of previously published social validity tools earlier in this article, the majority of measures focused on proximal variables (i.e., ease of implementation, treatment integrity), with the only distal measure being cost. Of course, these tools were designed for the evaluation of applied research or work in complex settings like schools and are appropriate for those purposes. Because we wish to examine social validity in terms of situation variables and distal effects, we must develop a new set of questions that will capture those situational variables and how they interact in a client’s interpretation of what is appropriate.

The primary concern is including situational variables and setting factors relevant to individual clients in order to better understand the acceptability and value of treatment, as these vary greatly from family to family. In addition, Fawcett (1991) offered general procedures to consider when assessing for social validity. Although many of these points were originally designed for applied research, there are some variables that are relevant for assessing services during a pandemic. The first procedures suggested that expert evaluators be arranged. In the current context, we consider the patient’s parents consumers our experts. Other relevant considerations included the use of Likert-type scales for assessment. Many design components both from Fawcett and others do not translate directly, as evaluating applied research has been the primary purpose for social validity measures. When outcomes or effects are measured after a study or intervention, it is possible to ask questions that relate more concretely to direct measures. Still, the concept of proximal and distal factors may be translated to setting factors (proximal) and situational variables (distal) encouraged by Schwartz as vital components to linking consumer behavior to behavior-analytic treatment. Our exercise is necessarily subjective, as it invites the opinion of our client-consumers.

Structured Interview Tool

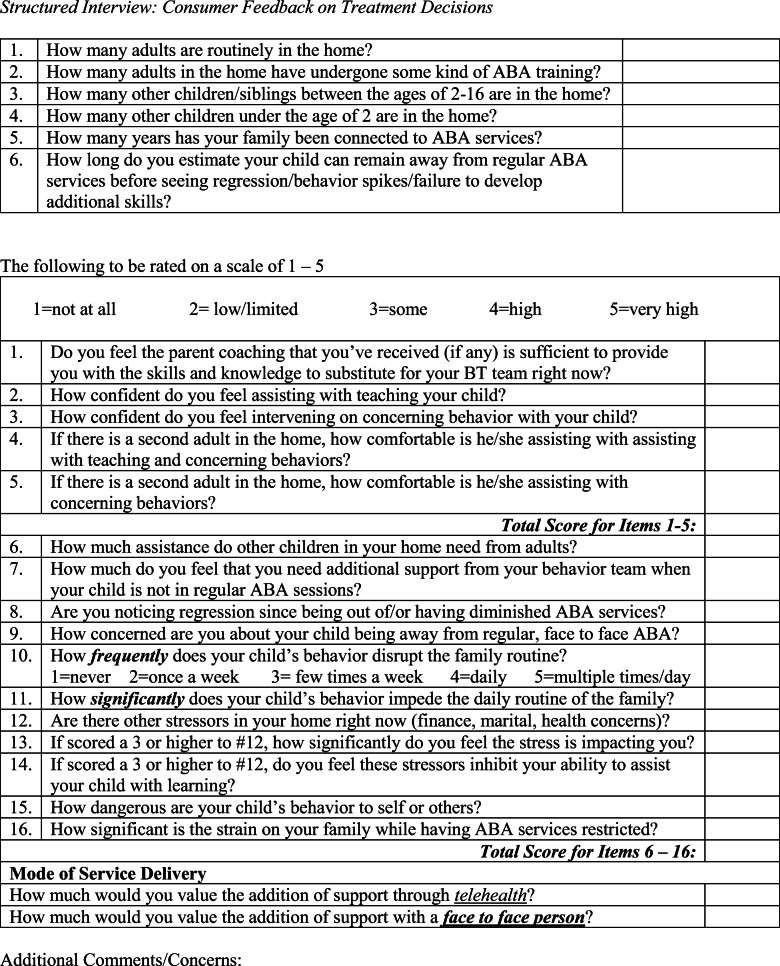

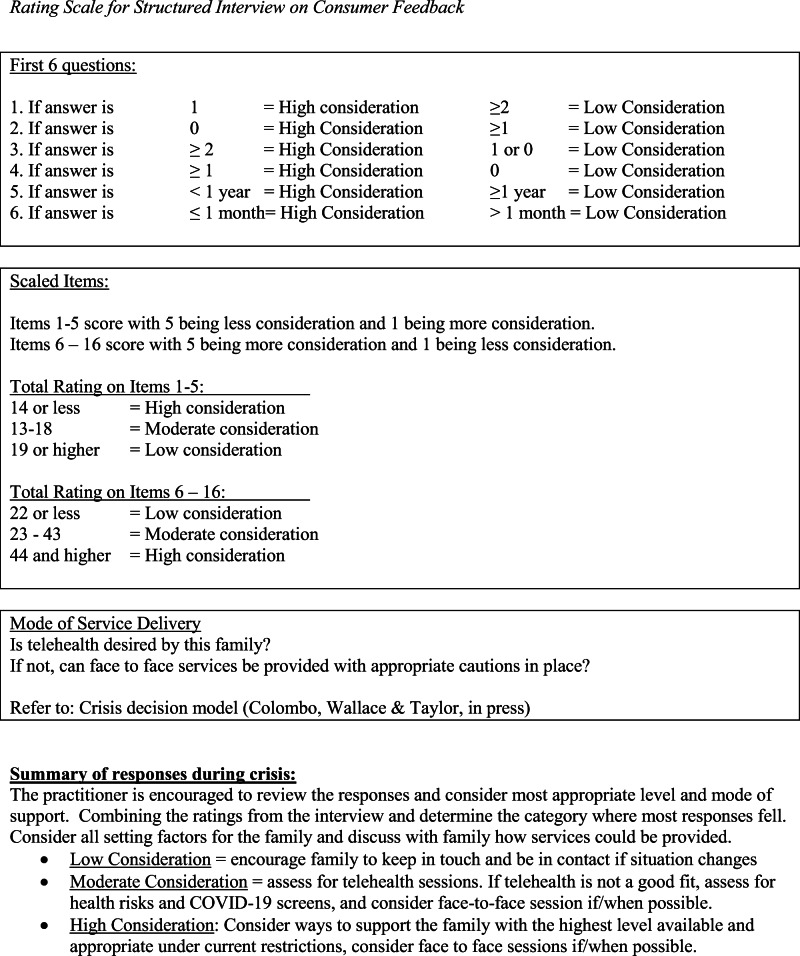

The structured interview is shown in Appendix 1. It combines a set of questions designed to capture setting factors and setting events, as recommended by Schwartz (1991), with a primary focus on intermediate and distal measures, as recommended by Fawcett (1991). The authors acknowledge that the set of questions presented in the structured interview (Appendix 1) and the rating scale (Appendix 2) have not been validated or tested. Future research may provide information on the metrics of using a system such a this, and we hope such evaluation is quickly forthcoming. We are proposing this interview for practitioners to consider, despite its developmental stage, due to the timeliness of the COVID-19 crisis and the immediate burden it has placed on ABA providers. This tool was developed by experienced Board Certified Behavior Analysts with over 60 years of combined experience in the field. It is intended to be used as a helpful exercise by practitioners who are synthesizing a great deal of information about treatment procedures during an unprecedented pandemic. This exercise will not replace or simplify the decision models proposed by Colombo et al. (2020) or by Cox et al. (2020). The purpose of the exercise is to incorporate the client’s perspective with contextual information that may modify the value and acceptability of treatment during a crisis. Including vital input in real time from client-consumers will enhance our work, add value to our service, and promote the development of the field of behavior analysis.

This interview tool considers variables that affect the manner in which a caregiver intercedes, mediates, and manages more of the process in the event of an absence of or reduction in professional support. The first six questions of the tool account for objective information, such as the number of children in the home and the length of time the family has received ABA services. The next section of the tool takes into account subjective ratings from the caregiver on a number of issues that could affect the ability to conduct and be effective with ongoing ABA services if there is a change in frequency or setting.

Conclusion

The topic of social validity is not new. In fact, it has been studied for over 40 years. The COVID-19 pandemic was the impetus of a series of publications geared toward improving the practices of behavior analysis; however, very little attention was given to social validity. The aim of our article was to highlight the importance of social validity during the pandemic and provide the practitioner with an exercise to gain the client’s and family’s perspective. This pandemic presents a moment in history that affords the practitioner with the unique opportunity to discuss the acceptability of treatment and services with clients and their families as they relate to critical daily-life functioning. These conversations and decisions regarding the social validity of our treatment can authentically occur in a way that could not be contrived in any other circumstance. As Wolf (1978) ribbed,

They would ask us: “How do you know what skills to teach? . . . How do you know that these are really appropriate?” We, of course, tried to explain that we were psychologists and thus the most qualified judges of what was best for people. Somehow, they didn’t seem convinced by that logic. (p. 206)

During this pandemic and throughout treatment, client-consumers and their family members, who are also consumers, should all be part of this decision-making process. The COVID-19 pandemic has presented barriers to treatment in a manner not anticipated, rehearsed, or prepared for. Given the numerous serious issues and factors facing practitioners at this juncture, having resources that connect with consumers regarding our services may prove useful. The structured interview described here is offered as an exercise in social validity. It is intended to serve as a method to identify and consider barriers for individuals and their families and thereby to understand the value of the treatment we offer from the view of true social significance. By working with families on the individualized and ongoing assessment of the components needed to create an acceptable, valid, and significant treatment approach, the practitioner may be empowered to make balanced clinical decisions about treatment. Social validity is a complex tenet that has received attention from great thinkers in the field of ABA. The aspect of social validity as it is related to consumer behavior touches on the critical point at which the science and practice of behavior analysis converge, and the result (we hope) is a meaningful and socially significant outcome. As practitioners in the field of ABA, we strive to continue to address socially relevant issues through the application of behavior analysis even during the age of COVID-19. Faced with more complex decisions than ever before, we must consider the situational variables that affect consumer behaviors. We recognize the subjective nature of this exercise and propose it is essential in an effort to maintain the productive dissemination of ABA. At some point in the not-too-distant future, this crisis will subside. How will our consumers reflect upon our behavior as ABA practitioners regarding our flexibility and attention to their changing needs? We rely on Wolf’s (1978) assertion that subjective measurement may indeed be at the heart of behavior analysis.

Author note

The authors would like to thank Rachel Taylor for her insightful and valuable comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Professional Behavior Analysts. (2020). Guidelines for practicing applied behavior analysis during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Retrieved from https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.apbahome.net/resource/collection/1FDDBDD2-5CAF4B2A-AB3F-DAE5E72111BF/APBA_Guidelines_-_Practicing_During_COVID19_Pandemic_040920.pdf

- Baer DM, Wolf MM, Risley TR. Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1968;1:91–97. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer DM, Wolf MM, Risley TR. Some still-current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1987;20(313):327. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1987.20-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board . Professional and ethical compliance code for behavior analysts. Littleton, CO: Author; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2020). Ethics guidance for ABA providers during COVID-19 pandemic. Retrieved from https://www.bacb.com/ethics-guidance-for-aba-providers-during-covid-19-pandemic-2/

- Carr JE, Austin JL, Britton LN, Kellum KK, Bailey JS. An assessment of social validity trends in applied behavior analysis. Behavioral Interventions. 1999;14:223–231. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-078X(199910/12)14:4<223::AID-BIN37>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). How to protect yourself. Retrieved April 28, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html

- Colombo, R. A., Wallace, M., & Taylor, R. (2020). An essential service decisions model for applied behavior analytic providers during crisis. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 13, 306–311. 10.31234/osf.io/te8ha [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Council of Autism Service Providers. (2020). Organizational guidelines and standards. Retrieved from https://casproviders.org/wpcontent/uploads/2020/03/CASP_ALS_Booklet_v1_1.3.20.pdf

- Cox DJ, Plavnick JB, Brodhead MT. A proposed process for risk mitigation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2020;13:299–305. doi: 10.1007/s40617-020-00430-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott SN, Treuting MVB. The Behavior Intervention Rating Scale: Development and validation of a pretreatment acceptability and effectiveness measure. Journal of School Psychology. 1991;29:43–51. doi: 10.1016/0022-4405(91)90014-I. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa, F., Metko, A., Raimondi, M., Impenna, M., & Scognamiglio, E. (2020). A model of support for families of children with autism living in the COVID-12 lockdown: Lessons from Italy. Behavior Analysis in Practice. Advance online publication. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5733-3709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fawcett SB. Social validity: A note on methodology. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1991;24:235–239. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1991.24-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, J. L., Cihon, J. H., Leaf, J. B., Van Meter, S. M., McEachin, J., & Leaf, R. (2019). Assessment of social validity trends in the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. European Journal of Behavior Analysis, 20, 146–157. 10.1080/15021149.2018.1534771

- Finn C, Sladeczek I. Assessing the social validity of behavioral interventions: A review of treatment acceptability measures. School Psychology Quarterly. 2001;16(2):176–206. doi: 10.1521/scpq.16.2.176.18703. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SA, Watson SL. The impact of parenting stress: A meta-analysis of studies comparing the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2013;43(3):629–642. doi: 10.1007/s10803-012-1604-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Assessing the clinical or applied importance of behavior change through social validation. Behavior Modification. 1977;1:427–452. doi: 10.1177/014544557714001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, French NH, Sherick RB. Acceptability of alternative treatments for children: Evaluations by inpatient children, parents, and staff. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1981;49(6):900–907. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.49.6.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley ML, Heffer RW, Gresham FM, Elliott SN. Development of a modified treatment evaluation inventory. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 1989;11:235–247. doi: 10.1007/BF00960495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy CH. Trends in the measurement of social validity. The Behavior Analyst. 1992;15(2):147–156. doi: 10.1007/BF03392597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy CH. The maintenance of behavior change as an indicator of social validity. Behavior Modification. 2002;26(5):594–604. doi: 10.1177/014544502236652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc LA. Editor’s note: The power of big ideas. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2020;53(1):6–9. doi: 10.1002/jaba.673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens BK, Witt JC, Elliott SN, Darveaux DX. Teacher judgments concerning the acceptability of school-based interventions. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1985;16(2):191–198. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.16.2.191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miltenberger, R. G. (1990). Assessment of treatment acceptability: A review of the literature. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 10(3), 24–38. 10.1177/027112149001000304.

- Moran, D. J., & Ming, S. (2020). The mindful action plan: Using the MAP to apply acceptance and commitment therapy to productivity and self-compassion for behavior analysts. Behavior Analysis Practice. Advance online publication. 10.1007/s40617-020-00441-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Park EY, Blair KSC. Social validity assessment in behavior interventions for young children: A systematic review. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2019;39(3):156–169. doi: 10.1177/02711221419860195. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reimers TM, Wacker DP. Parents’ ratings of the acceptability of behavioral treatment recommendations made in an outpatient clinic: A preliminary analysis of the influence of treatment effectiveness. Behavioral Disorders. 1988;14:7–15. doi: 10.1177/019874298801400104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reimers TM, Wacker DP, Cooper LJ. Evaluation of the acceptability of treatments for their children’s behavioral difficulties: Ratings by parents receiving services in an outpatient clinic. Child & Family Behavior Therapy. 1991;13(2):53–71. doi: 10.1300/J019v13n02_04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez K. Maintaining treatment integrity in the face of crisis: A treatment selection model for transitioning direct ABA services to telehealth. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2020;13:291–298. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/phtgv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, I. S. (1991). The study of consumer behavior and social validity: An essential partnership for applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 24(2), 241–244. 10.1901/jaba.1991.24-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schwartz IS, Bear DM. Social validity assessments: Is current practice state of the art? Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1991;24:189–204. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1991.24-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarnowski KJ, Simonian SJ. Assessing treatment acceptance: The Abbreviated Acceptability Rating Profile. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1992;23(2):101–106. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(92)90007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winett RA, Moore JF, Anderson ES. Extending the concept of social validity: Behavior analysis for disease prevention and health promotion. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1991;24(2):215–230. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1991.24-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt, J. C., & Elliott, S. N. (1985). Acceptability of classroom management strategies. In T. R. Kratochwill (Ed.), Advances in school psychology (Vol. 4, pp. 251–288). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Wolf MM. Social validity: The case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1978;11(2):203–214. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1978.11-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Word Reference. (n.d.). Definition of social significance. Retrieved August 10, 2020, from https://forum.wordreference.com

- Yi, Z., & Dixon, M. R. (2020). Developing and enhancing adherence to a telehealth ABA parent training curriculum for caregivers of children with autism. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 10.31234/osf.io/sc7br. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]