Abstract

Background: miR-146a has been demonstrated to be involved in normal hematopoiesis and the pathogenesis of many hematological malignancies by inhibiting the expression of its targets. Rs2910164(G>C) may modify the expression of the miR-146a gene, which might influence an individual's predisposition to childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). However, inconsistent findings have been reported on the association between the rs2910164(G>C) polymorphism and the risk of childhood ALL.

Methods: A comprehensive meta-analysis was performed to accurately estimate the association between the miR-146a rs2910164 polymorphism and childhood ALL among four different genetic models.

Results: This meta-analysis included Asian studies with a total of 1,543 patients and 1,816 controls. We observed a significant difference between patients and controls for the additive model (CC vs. GG: OR = 1.598, 95% CI: 1.003–2.545, P = 0.049) using a random effects model. Meanwhile, there was a trend of increased childhood ALL risk in the dominant model (CC + CG vs. GG: OR = 1.501, 95% CI: 0.976–2.307, P = 0.065), recessive model (CC vs. GG + CG: OR = 1.142, 95% CI: 0.946–1.380, P = 0.168) and allele model (C vs. G: OR = 1.217, 95% CI: 0.987–1.500, P = 0.066) between patients and controls.

Conclusions: Our findings suggest that the miR-146a rs2910164 CC genotype was significantly associated with childhood ALL susceptibility.

Keywords: childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia, miR-146a, rs2910164, Asian population, meta-analysis

Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is a very common malignancy among children, accounting for ~75% of leukemia cases among children (Pui et al., 2015). The incidence of this disease has continued to increase worldwide over the past several decades (Terracini, 2011). ALL is a clonal malignant disease that is characterized by an uncontrolled proliferation of immature cells, but its etiology remains unknown. MiRNAs are small non-coding RNAs that monitor gene expression post-transcriptionally. Previous studies have shown that miRNAs may play an important role in leukemogenesis (Schotte et al., 2010; Bottoni and Calin, 2013; Yan et al., 2013; Yin et al., 2014).

miR-146a has been identified as a modulator of cell differentiation and innate and adaptive immunity (Boldin et al., 2011; Rusca and Monticelli, 2011; Ghani et al., 2012; Labbaye and Testa, 2012). The abnormal expression of miR-146a is frequently observed in human diseases, such as inflammatory disorders and cancers (He et al., 2005; Iriyama et al., 2012; Petrovic et al., 2017; Shomali et al., 2017; Tan et al., 2018). Previous studies have reported that miR-146a is significantly increased in the peripheral blood samples of pediatric patients with ALL (Duyu et al., 2014; Yan et al., 2017), thus providing valuable insights into potential diagnostic or prognostic biomarkers. Lin showed that the absence of miR-146a can lead to leukemia in mice (Lin et al., 2015), which indicated that miR-146a might act as a leukemia suppressor. In addition, miR-146a might be involved in the progression of ALL by mediating the inflammatory response. Nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) signaling has been reported to be constitutively activated in a variety of leukemic cells. miR-146a could be upregulated by NF-κB (Justiniano et al., 2013; Taganov et al., 2015) and simultaneously inhibit the expression of TRAF6 and IRAK1, which are upstream regulatory proteins of NF-κB. Therefore, a negative feedback regulatory pathway is formed in the proliferation and differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells, similar to the development of hematological malignancies (Spierings et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2011, 2013).

In the rs2910164 polymorphism, which is located in pre-miR-146a, the nucleotide substitution from G to C leads to a transformation from a G:U pair to a C:U mismatch in the stem structure of the miR-146a precursor and results in a reduced amount of mature miR-146a (Yue et al., 2011; Palmieri et al., 2014). Jazdaewski found that mature miR-146a with the C allele is less able to inhibit the target genes IRAK1 and TRAF6 than the G allele (Jazdzewski et al., 2008), which seems to be associated with the development of ALL.

A significant association of miR-146a rs2910164 with childhood ALL has been reported in an Iranian population (Hasani et al., 2014). This result was successfully replicated in two Chinese case-control studies (Liu et al., 2018; Pei et al., 2020). In contrast, three studies from Thailand, India and China failed to replicate the results (Chansing et al., 2016; Devanandan et al., 2019; Xue et al., 2019). Considering the conflicting results, whether miR-146a rs2910164 is associated with childhood ALL in Asian populations remains to be elucidated. In this study, we performed a meta-analysis to estimate the association of miR-146a rs2910164 with childhood ALL among four different genetic models in an Asian population.

Materials and Methods

This study was pursuant to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The PRISMA checklist is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Literature Search

The PubMed, Google Scholar, WanFang and Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure databases were systematically searched for relevant studies using the words “miR-146a or microRNA-146a” “rs2910164” “leukemia” with no language or time restrictions. All studies were assessed by reading the title and abstract and irrelevant studies were excluded. Then, the full texts of the remaining studies were assessed to determine their eligibility.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The study inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) case-control or cohort studies that assessed the association between the miR-146a rs2910164 polymorphism and the risk of childhood ALL; (b) studies in which all patients had been diagnosed with ALL by morphology, immunology, cytogenetic and molecular biology (MICM) in accordance with one of the following criteria: (i) bone marrow morphology standard: according to the 2016 WHO diagnostic criteria, the original and immature lymphocytes in bone marrow are not <20%, (ii) if the original and immature lymphocytes were <20%, a molecular diagnosis method was used to determine whether ALL pathogenic genes existed; (c) studies with data that could be used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs); and (d) studies published before April 30, 2020.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (a) the study was not a case–control study; (b) the study was not related to acute lymphoblastic leukemia or 146a rs2910164; (c) the study lacked particular genotype data; (d) the genotype distribution of the control subjects was not in a Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE).

Data Extraction

The following data were independently extracted from included studies and entered into a database to ensure the veracity of the data: first author's name, year of publication, population, genotyping techniques, number of patients and controls, genotype distribution, allele distribution, HWE and other information. Studies were excluded if they did not provide the above information.

Statistical Analysis

The Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium was examined by Pearson's chi-squared test. Four genetic models were used in the study: the dominant model (CC +CG vs. GG), the recessive model (CC vs. GG + CG), the additive model (CC vs. GG) and the allele model (C vs. G). Genetic heterogeneity was evaluated using the Q-test and I2-test. I2 statistics range from 0 to 100%. Significant heterogeneity was defined as P < 0.01 and I2 > 50%. ORs with corresponding 95% CIs were calculated using the fixed effects model (Mantel-Haenszel) when no significant heterogeneity was observed; otherwise, a random effects model was used. The Z-test was used to test the significance of the ORs. To check the stability of our results, sensitivity analyses for the overall effect were conducted by excluding one study at a time. Additionally, Egger's and Begg's tests were used to assess publication bias. The statistical analyses were performed using the STATA v.16.0 software (Stata Corporation, Texas, USA), Review Manager 5.0.24 (The Nordic Cochrane Center, Denmark), R version 3.6.2 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria) and RStudio version 1.2.1 (Certified B Corporations, Boston, USA).

Results

Study Inclusion and Characteristics

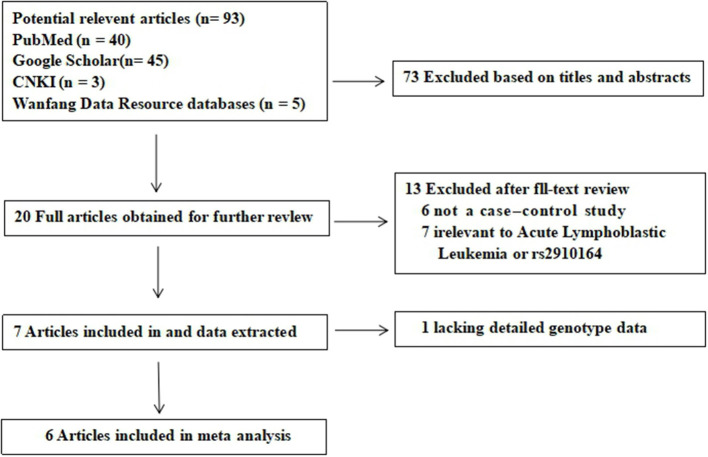

A total of 113 potential studies were retrieved through the initial search. Twenty duplicates were excluded. Then, the titles and abstracts of 93 studies were screened and 73 studies were excluded. The full texts of the remaining 20 articles were evaluated; 6 were excluded because they were not case-control studies and 7 were excluded because they were not related to acute lymphoblastic leukemia or rs2910164 and 1 study was excluded because it did not provide sufficient data. A flow chart of the study selection process is shown in Figure 1. There were 6 potentially relevant papers, including 5 written in English and 1 written in Chinese. A total of 1,543 childhood ALL patients and 1,816 healthy controls were included in the meta-analysis. Table 1 shows the characteristics of each study. Power analysis was conducted with the total sample size and revealed a power of 94.6% using an OR of 1.2 for the risk allele and a MAF of 0.39 for the C allele.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the literature search and selection.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis.

| References | Population | Genotyping | Number of participants | Genotype distribution (n) | Allele distribution (n) | HWE (P) | MAF | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GG | GC | CC | G | C | |||||||

| Hasani et al. (2014) | Southeast Iranian | T-ARMS-PCR | 75 | ALL | 7 | 46 | 22 | 60 | 90 | 0.400 | |

| 97 | CTR | 27 | 50 | 20 | 104 | 90 | 0.72 | 0.464 | |||

| Chansing et al. (2016) | Thailand | PCR-RFLP | 100 | ALL | 11 | 54 | 35 | 76 | 124 | 0.380 | |

| 200 | CTR | 31 | 96 | 73 | 158 | 242 | 0.95 | 0.395 | |||

| Liu et al. (2018) | Baoding, China | PCR-RFLP | 200 | ALL | 32 | 89 | 79 | 153 | 247 | 0.383 | |

| 100 | CTR | 29 | 41 | 30 | 99 | 101 | 0.07 | 0.495 | |||

| Devanandan et al. (2019) | India | PCR-RFLP | 71 | ALL | 27 | 32 | 12 | 86 | 56 | 0.394 | |

| 74 | CTR | 25 | 37 | 12 | 87 | 61 | 0.78 | 0.412 | |||

| Xue et al. (2019) | Nanjing, China | SNaPshot | 831 | ALL | 263 | 429 | 139 | 955 | 707 | 0.425 | |

| 1,079 | CTR | 369 | 541 | 169 | 1279 | 879 | 0.21 | 0.407 | |||

| Pei et al. (2020) | Taiwan, China | PCR-RFLP | 266 | ALL | 112 | 125 | 29 | 349 | 183 | 0.344 | |

| 266 | CTR | 90 | 117 | 59 | 297 | 235 | 0.08 | 0.442 | |||

ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; CTR, control; HWE, Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium; MAF, minor allele frequency.

Heterogeneity Analysis

The Cochran's Q test and the I2 statistics shown in Table 2 revealed that high heterogeneity among studies was detected in the CC +CG vs. GG (I2 = 74.9%), CC vs. GG + CG (I2 = 69.9%), CC vs. GG (I2 = 81.6%) and C vs. G (I2 = 79.5%) models for the rs2910164 polymorphism. As high heterogeneity was observed, sensitivity analysis was performed to analyze the sources of heterogeneity.

Table 2.

Heterogeneity analysis with random-effect model.

| Genetic model | N | OR | 95%-CI | Q | I2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC + CG vs. GG | 6 | 1.2828 | [0.8669; 1.8983] | 19.93 | 74.90% |

| CC vs. GG + CG | 6 | 0.9959 | [0.6870; 1.4435] | 16.61 | 69.90% |

| CC vs. GG | 6 | 1.2635 | [0.7010; 2.2776] | 27.16 | 81.60% |

| C vs. G | 6 | 1.0955 | [0.8423; 1.4249] | 24.37 | 79.50% |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; I2, measure to quantify the degree of heterogeneity in meta-analyses.

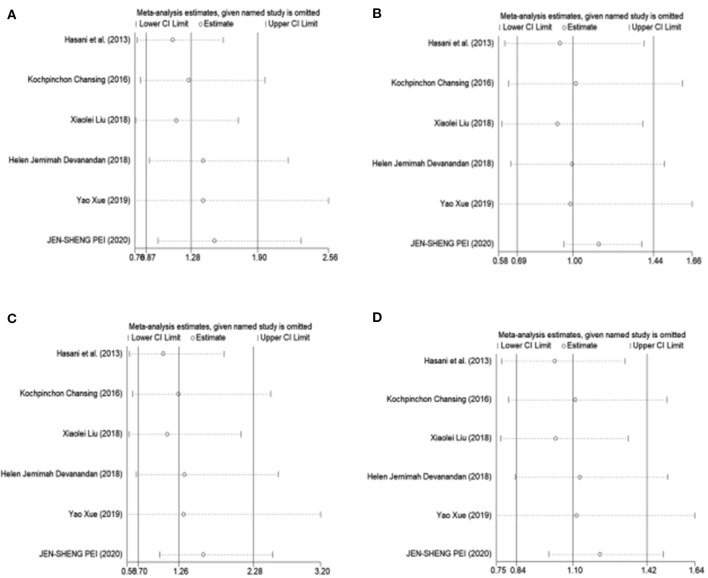

Sensitivity Analysis

To estimate the influence of each study on the overall OR of the four genetic models and to analyze the sources of high heterogeneity, a sensitivity analysis was performed with a random effects model. The results are shown in Figure 2. Omitting Pei's study effectively reduced heterogeneity, especially in the recessive model (CC vs. GG + CG: I2 = 0.0%, P = 0.571). The other three models showed a moderate degree of heterogeneity (CC +CG vs. GG: I2 = 66.5%, P = 0.018; CC vs. GG: I2 = 57.9%, P = 0.050; C vs. G: I2 = 54.3%, P = 0.068, respectively) (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Sensitivity analysis was performed by removing one study at a time. (A) Dominant model, CC +CG vs. GG. (B) Recessive model, CC vs. GG + CG. (C) Additive model, CC vs. GG. (D) Allele model, C vs. G.

Table 3.

Heterogeneity analysis after omitting Pei's study with random-effect model.

| Genetic model | Study(n) | OR | 95%-CI | Q | I2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC + CG vs. GG | 5 | 1.5006 | [0.9760; 2.3072] | 11.94 | 66.50% |

| CC vs. GG + CG | 5 | 1.1413 | [0.9439; 1.3799] | 2.92 | 0.00% |

| CC vs. GG | 5 | 1.5977 | [1.0027; 2.5455] | 9.51 | 57.90% |

| C vs. G | 5 | 1.2167 | [0.9873; 1.4995] | 8.74 | 54.30% |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; I2, measure to quantify the degree of heterogeneity in meta-analyses.

Results of the Association Between miR-146a rs2910164 and Childhood ALL Meta-Analysis

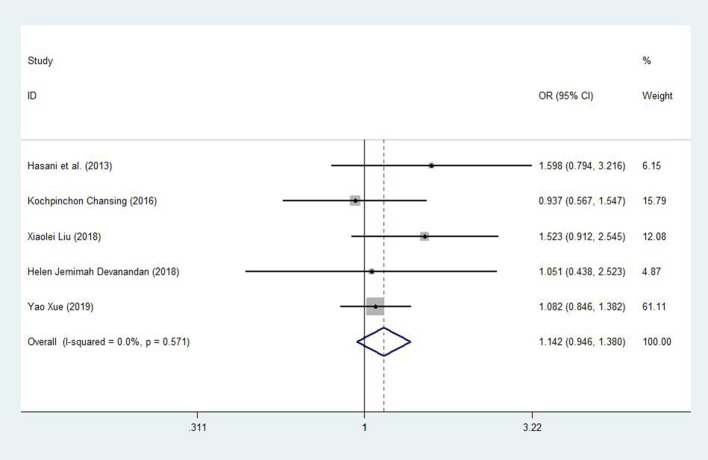

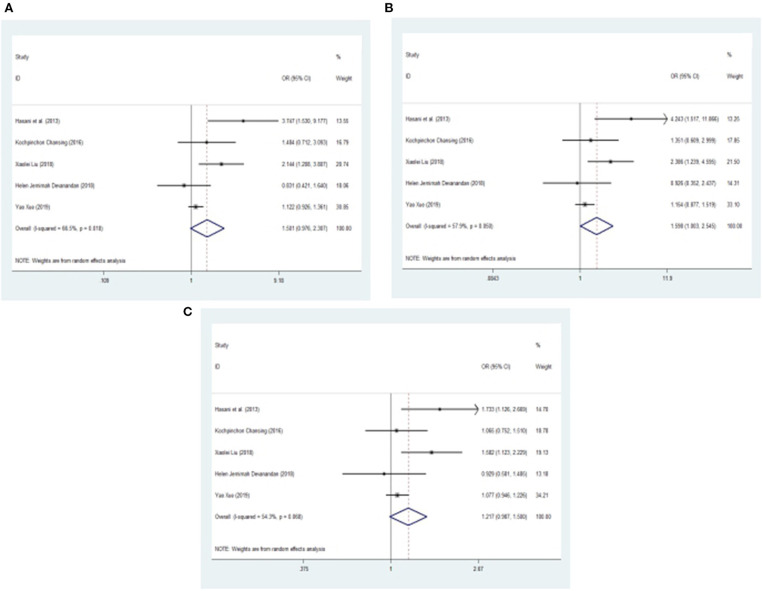

After one study was omitted, there was a moderate degree of heterogeneity among studies. A fixed effects model was used to analyze the recessive model; the dominant, additive and allele models were analyzed with a random effects model. The results showed a significant difference between childhood ALL patients and controls for the additive model (CC vs. GG: OR = 1.598, 95% CI: 1.003–2.545, P = 0.049) and a trend of increased childhood ALL risk for the dominant model (CC +CG vs. GG: OR = 1.501, 95% CI: 0.976–2.307, P = 0.065), recessive model (CC vs. GG + CG: OR = 1.142, 95% CI: 0.946–1.380, P = 0.168) and allele model (C vs. G: OR = 1.217, 95% CI: 0.987–1.500, P = 0.066) between patients and controls (Figures 3, 4).

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis with a fixed effects model for the association between the miR-146a rs2910164 polymorphism and childhood ALL susceptibility (recessive model, CC vs. GG + CG). OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; I-squared, measure to quantify the degree of heterogeneity in meta-analyses.

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis with a random effects model for the association between the miR-146a rs2910164 polymorphism and childhood ALL susceptibility. (A) Dominant model, CC +CG vs. GG. (B) Additive model, CC vs. GG. (C) Allele model, C vs. G. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; I-squared, measure to quantify the degree of heterogeneity in meta-analyses.

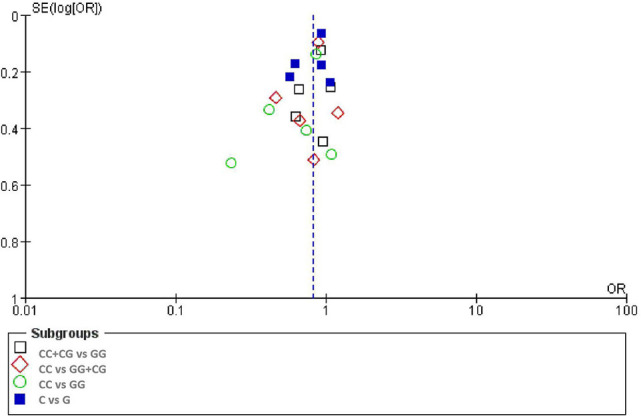

Publication Bias

There was no significant publication bias in any of the genetic models according to Begg's and Egger's tests (all P > 0.05, data not shown) and the funnel plot was symmetrical, as the studies did not coagulate into one quadrant of the funnel (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Funnel plot of the odds ratios in the meta-analysis.

Discussion

This meta-analysis included six Asian studies about the miR-146a rs2910164 loci and susceptibility to childhood ALL. Three studies reported an association between miR-146a rs2910164 and the risk of childhood ALL and the other three showed negative results. Moreover, the sample sizes of the individual studies were small, making it difficult to identify the possible small effect of rs2910164 on childhood ALL. Thus, this study enabled us to more accurately determine the association between rs2910164 and childhood ALL susceptibility due to the increased sample size and statistical power of the meta-analysis.

In this study, a total of 1,543 ALL patients and 1,816 controls were investigated to provide an overall evaluation of the association between the miR-146a rs2910164 polymorphism and childhood ALL. We conducted heterogeneity analysis and the results revealed that high heterogeneity among studies was detected in the four genetic models. Therefore, we explored the source of this heterogeneity via sensitivity analysis by omitting one study at a time. The results showed that omitting Pei's study could effectively reduce heterogeneity, especially in the recessive model and the other three models showed a moderate degree of heterogeneity. The most likely reasons for this heterogeneity might involve ethnicity, geographical region and the selection of control groups. The minor allele frequencies (MAFs) ranged from 0.395 to 0.495 in each study (Table 1). In Pei, Liu and Hasanis' studies, the MAF was higher than the NCBI SNP database in Asian populations. However, Pei's study sample sizes are larger than those of Liu and Hasanis. This is why Pei's study has a strong influence on heterogeneity. In addition, the populations of the control groups were not uniform. Individuals in the control group in Pei's study were determined to be cancer-free in accordance with the criteria set by the International Classification of Disease (ninth revision, defined by World Health Organization), but other studies did not explain the diagnostic criteria of the control groups. Thus, after omitting Pei's study, a fixed effects model was used to analyze the recessive model; the dominant, additive and allele models were analyzed with a random effects model. The results showed a significant difference between childhood ALL patients and controls for the additive model. Interestingly, there was a trend of increased childhood ALL risk in the other three modalities between patients and controls. These results showed that miR146a rs2910164 (G>C) was significantly associated with childhood ALL susceptibility.

In recent years, an increasing amount of data have demonstrated that miR-146a is related to normal hematopoiesis and the pathogenesis of some hematological malignancies by inhibiting the expression of its targets (Hua et al., 2011). The miR146a rs2910164 polymorphism has been extensively tested in different cancers. The rs2910164 CG or GG genotype was linked to a significantly decreased risk for lung cancer compared to the CC genotype (Jeon et al., 2014). In addition, the rs2910164 CC genotype may be devoted to breast cancer susceptibility in Europeans (Lian et al., 2012). For childhood ALL. Previous studies found that the rs2910164 CC or CG genotype significantly increased the risk of ALL (Hasani et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2018). The miR146a rs2910164 GG genotype was significantly related to a decreased susceptibility to childhood ALL (Pei et al., 2020). This study confirms that the miR146a rs2910164 polymorphism (G>C) contributes to childhood ALL susceptibility among Asians.

There are still some limitations in our study. Firstly, due to the limited examination of miR-146a rs2910164 in childhood ALL, only six studies were included in the meta-analysis. Secondly, the current research only includes Asian studies and there is an urgent need to conduct research using large samples of other ethnic groups across the world. Thirdly, the complexity of ALL, which is the result of the interaction of genetic and environmental factors, may affect the results. Among individuals with the same genotype, their susceptibility to ALL may be different due to the geographical environment lifestyle and other factors of the diverse population (Garzon et al., 2010).

In conclusion, our work contributed important evidence regarding the association between the miR-146a rs2910164 CC genotype and susceptibility to childhood ALL in an Asian population. Given the relatively small sample size of this study, more large-sample studies including different ethnic populations are needed to validate these results.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

DZ, JY, ZY, and QZ were responsible for the statistical analysis, study design, and manuscript preparation. DZ and CT managed the literature searches and analyses. This study was supervised by YW, QC, and RC. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This study was jointly funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81770034) and the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2020A1515010240).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2020.00886/full#supplementary-material

References

- Boldin M. P., Taganov K. D., Rao D. S., Yang L., Zhao J. L., Kalwani M., et al. (2011). miR-146a is a significant brake on autoimmunity,myeloproliferation and cancer in mice. J. Exp. Med. 208, 1189–1201. 10.1084/jem.20101823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottoni A., Calin A. G. (2013). MicroRNAs as main players in the pathogenesis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. MicroRNA. 2, 158–164. 10.2174/2211536602666131126002337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chansing K., Pakakasama S., Hongeng S, Thongmee A., Pongstaporn W. (2016). Lack of association between the MiR146a polymorphism and susceptibility to thai childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 17, 2435–2438. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devanandan H. J., Venkatesan V., Scott J. X., Magatha L. S., Paul S. F. D., Koshy T. (2019). MicroRNA 146a polymorphisms and expression in indian children with acute lymphoblastic Leukemia. Lab Med. 50, 249–253. 10.1093/labmed/lmy074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duyu M., Durmaz B., Gunduz C., Vergin C., Karapinar D. Y., Aksoylar S., et al. (2014). Prospective evaluation of whole genome microRNA expression profiling in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014:967585. 10.1155/2014/967585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garzon R., Marcucci G., Croce C. M., et al. (2010). Targeting microRNAs in cancer: rationale, strategies and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 9, 775–789. 10.1038/nrd3179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghani S., Riemke P., Schönheit J., Lenze D., Stumm J., Hoogenkamp M., et al. (2012). Macrophage development from HSCs requires PU.1-coordinated microRNA expression. Blood 118, 2275–2284. 10.1182/blood-2011-02-335141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasani S. S., Hashemi M., Eskandari-Nasab E., Naderi M., Omrani M., Sheybani-Nasab M. (2014). A functional polymorphism in the miR-146a gene is associated with the risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia:a preliminary report. Tumour Biol. 35, 219–225. 10.1007/s13277-013-1027-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He H., Jazdzewski K., Li W., Liyanarachchi S., Nagy R., Volinia S., et al. (2005). The role of microRNA genes in papillary thyroid carcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 19075–19080. 10.1073/pnas.0509603102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua Z., Chun W., Fang-Yuan C. (2011). MicroRNA-146a and hematopoietic disorders. Int. J. Hematol. 94, 224–229. 10.1007/s12185-011-0923-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iriyama N., Yoshino Y., Yuan B., Horikoshi A., Hirabayashi Y., Hatta Y., et al. (2012). Speciation of arsenic trioxide metabolites in peripheral blood and bone marrow from an acute promyelocytic leukemia patient. J. Hematol. Oncol. 5:1. 10.1186/1756-8722-5-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jazdzewski K., Murray E. L., Franssila K., Jarzab B., Schoenberg D. R., Chapelle A., et al. (2008). Common SNP in pre-miR-146a decreases mature miR expression and predisposes to papillary thyroid carcinoma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 7269–7274. 10.1073/pnas.0802682105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon H. S., Lee Y. H., Lee S. Y., Jang J. A., Choi Y. Y., Yoo S. S., et al. (2014). A common polymorphism in pre-microRNA-146a is associated with lung cancer risk in a Korean population. Gene 534, 66–71. 10.1016/j.gene.2013.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justiniano S. E., Elavazhagan S, Fatehchand K., Shah P., Mehta P., Roda J. M., et al. (2013). Fcy receptor-induced soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 (VEGFR-1) production inhibits angiogenesis and enhances efficacy of anti-tumor antibodies. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 26800–26809. 10.1074/jbc.M113.485185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbaye C., Testa U. (2012). The emerging role of miR-146a in the control of hematopoiesis,immune function and cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 5:13. 10.1186/1756-8722-5-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian H., Wang L., Zhang J. (2012). Increased risk of breast cancer associated with CC genotype of has-miR-146a rs2910164 polymorphism in Europeans. PLoS ONE 7:e31615. 10.1371/journal.pone.0031615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y., Zhang Q., Zhang H., Liu W., Liu C., Li Q., et al. (2015). Transcription factor and miRNA co-regulatory network reveals shared and specific regulators in the development of B cell and T cell. Sci. Rep. 5:15215. 10.1038/srep15215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Liu L., Cao Z., Guo B., Li M. (2018). Association between miR-146a (rs2910164) G > C polymorphism and susceptibility to acute lym phoblastic leukemia in children. Chin. J. Appl. Clin. Pediatr. 33:200–202. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.2095-428X.2018.03.010 (in Chinese). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri A., Carinci F., Martinelli M., Pezzetti F., Girardi A., Cura F., et al. (2014). Role of the MIR146A polymorphism in the origin and progression of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Eur. J. Oral. Sci. 122, 198–201. 10.1111/eos.12121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei J., Chang W. S., Hsu P., Chen C., Chin Y., Huang T., et al. (2020). Significant association βetween the MiR146a genotypes and susceptibility to childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia in Taiwan. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 17, 175–180. 10.21873/cgp.20178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic N., Davidovic R., Bajic V., Obradovic M., Isenovic R. E., et al. (2017). MicroRNA in breast cancer: the association with BRCA1/2. Cancer Biomark. 19, 119–128. 10.3233/CBM-160319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pui C., Yang J., Hunger S. P., Pieters R., Schrappe M., Biondi A., et al. (2015). Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: progress through collaboration. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 2938–2948. 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.1636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusca N., Monticelli S. (2011). miR-146a in immunity and disease. Mol. Biol. Int. 2011:437301. 10.4061/2011/437301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schotte D., Lange-Turenhout E. A. M., Stumpel D. J. P. M., Stam R. W., Buijs-Gladdineset J. G. C. A.M., Meijerink J. P. P., et al. (2010). Expression of miR-196b is not exclusively MLL-driven but is especially linked to activation of HOXA genes in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica 95, 1675–1682. 10.3324/haematol.2010.023481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shomali N., Mansoori B., Mohammadi A., Shirafkan N., Ghasabiet M., Baradaran B. (2017). MiR-146a functions as a small silent player in gastric cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 96, 238–245. 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.09.138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spierings D. C., McGoldrick D., Hamilton-Easton A. M., Neale G., Murchison E. P., Hannon G., et al. (2011). Ordered progression of stage-specific miRNA profiles in the mouse B2 B-cell lineage. Blood 117, 5340–5349. 10.1182/blood-2010-10-316034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taganov K. D., Boldin M. P., Chang K. J., Baltimore D. (2015). NF-kB-dependent induction of microRNA miR-146, an inhibitor targeted to signaling proteins of innate immune responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 12481–12486. 10.1073/pnas.0605298103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan W., Liao Y., Qiu Y., Liu H., Tan D., Wu T., et al. (2018). miRNA 146a promotes chemotherapy resistance in lung cancer cells by targeting DNA damage inducible transcript 3 (CHOP). Cancer Lett. 428, 55–68. 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.04.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terracini B. (2011). Epidemiology of childhood cancer. Environ. Health 10(Suppl.1):S8. 10.1186/1476-069X-10-S1-S8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y., Yang X., Hu S., Kang M., Chen J., Fang Y. (2019). A genetic variant in miR-100 is a protective factor of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Med. 8, 2553–2560. 10.1002/cam4.2082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J., Jiang N., Huang G., Tay J. L.-S., Lin B., Bi C., et al. (2013). Deregulated MIR335 that targets MAPK1 is implicated in poor outcome of paediatric acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 163, 93–103. 10.1111/bjh.12489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan W., Guo H., Suo F., Han C., Zheng H., Chen T. (2017). The effect of miR-146a on STAT1 expression and apoptosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia Jurkat cells. Oncol. Lett. 13, 151–154. 10.3892/ol.2016.5395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin J., Tang Q., Qian W., Qian J., Lin J., Wen X., et al. (2014). Increased expression of miR-24 is associated with acute myeloid leukemia with t(8;21). Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 7, 8032–8038. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue C., Wang M., Ding B., Wang W., Fu S., Zhou D., et al. (2011). Polymorphism of the pre-miR-146a is associated with risk of cervical cancer in a Chinese population. Gynecol. Oncol. 122, 33–37. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.03.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J. L., Rao D. S., Boldin M. P., Taganov K. D., O'Connelet R. M., Baltimore D. (2011). NF-kappaB dysregulation in microRNA-146a-deficient mice drives the development of myeloid malignancies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 9184–9189. 10.1073/pnas.1105398108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J. L., Rao D. S., O'Connell R. M., Garcia-Flores Y., Baltimore D. (2013). MicroRNA-146a acts as a guardian of the quality and longevity of hematopoietic stem cells in mice. Elife 2:e00537. 10.7554/eLife.00537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.