Abstract

Dynamic arterial elastance (Eadyn), the ratio between pulse pressure variation (PPV) and stroke volume variation (SVV), has been suggested as a dynamic parameter relating pressure and flow. We aimed to determine the effects of endotoxic septic shock and hemodynamic resuscitation on Eadyn in an experimental study in 18 New Zealand rabbits. Animals received placebo (SHAM, n = 6) or intravenous lipopolysaccharide (E. Coli 055:B5, 1 mg⋅kg–1) with or without (EDX-R, n = 6; EDX, n = 6) hemodynamic resuscitation (fluid bolus of 20 ml⋅kg–1 and norepinephrine for restoring mean arterial pressure). Continuous arterial pressure and aortic blood flow measurements were obtained simultaneously. Cardiovascular efficiency was evaluated by the oscillatory power fraction [%Osc: oscillatory work/left ventricular (LV) total work] and the energy efficiency ratio (EER = LV total work/cardiac output). Eadyn increased in septic animals (from 0.73 to 1.70; p = 0.012) and dropped after hemodynamic resuscitation. Eadyn was related with the %Osc and EER [estimates: −0.101 (−0.137 to −0.064) and −9.494 (−11.964 to −7.024); p < 0.001, respectively]. So, the higher the Eadyn, the better the cardiovascular efficiency (lower %Osc and EER). Sepsis resulted in a reduced %Osc and EER, reflecting a better cardiovascular efficiency that was tracked by Eadyn. Eadyn could be a potential index of cardiovascular efficiency during septic shock.

Keywords: cardiac output, arterial pressure, septic shock, dynamic arterial elastance, stroke volume variation, pulse pressure variation

Introduction

Variations in left ventricular (LV), stroke volume (SV), and arterial pulse pressure (PP) are closely related to changes in intrathoracic pressure during respiration (Pinsky, 1997). The magnitude of these changes has been used to define preload-dependency (Pinsky, 2012). Since the change in arterial PP for a change in SV has the dimension of elastance, the ratio between the PP variation (PPV) and SV variation (SVV) has been described as dynamic arterial elastance (Eadyn). This parameter has been proposed as a functional measure of the arterial load (Monge Garcia et al., 2014). It arises from the simultaneous assessment of PP and SV changes during a respiratory cycle and is related to the cardiac modulation of volume as a function of pressure (Monge Garcia et al., 2014). Although Eadyn was initially defined as a variable describing central arterial tone, Eadyn is affected not only by arterial factors but also by the heart rate (HR) and the pattern of blood flow during experimental changes in arterial load conditions (Monge Garcia et al., 2017). Moreover, we have recently demonstrated a significant relationship between Eadyn, ventriculo-arterial coupling, and LV mechanical efficiency (Monge Garcia et al., 2020). Accordingly, Eadyn could be considered as a composite index reflecting the interaction between both arterial and cardiac factors and potentially providing valuable information regarding cardiovascular performance and ventriculo-arterial coupling.

Although the primary function of the cardiovascular system is to deliver hydraulic energy (expressed in terms of blood flow and arterial pressure) to sustain normal physiological functions, there is an optimal combination of cardiac function and arterial system status that provides the maximum efficiency in transferring this mechanical energy from the LV to the arterial tree (Guarracino et al., 2013). Prior studies have demonstrated that this ideal combination occurs when the ventricle and the arterial tree are optimally coupled (Sunagawa et al., 1983; Asanoi et al., 1989).

Septic shock has a profound impact on macrohemodynamics and also the microcirculation (De Backer et al., 2002; Guarracino et al., 2014). Macrocirculatory derangements in septic shock have been characterized by a combination of a variable degree of cardiac dysfunction and a profound vasoplegia (Vieillard-Baron and Cecconi, 2014). These alterations are usually the expression of a ventricular-arterial uncoupling associated with a sepsis-induced cardiovascular inefficiency (Guarracino et al., 2014, 2019).

Since Eadyn has been shown to be affected by both arterial and cardiac factors, we hypothesized that sepsis-induced hemodynamic cardiovascular dysfunction could affect Eadyn. We, therefore, aimed to determine the effects of endotoxic septic shock on Eadyn, and the impact of hemodynamic resuscitation.

Materials and Methods

Eighteen New-Zealand rabbits (weight 2.5 ± 0.1 kg), supplied by the Reproduction Laboratory of the University of Cadiz, were maintained at a controlled temperature (23°C) in individual cages on a 12 h light/dark and fed with a standard rabbit chow diet and water up to the time of experimental procedures. Animals were allowed to acclimatize to the laboratory for 1 week before the beginning of the experiments. All methods and protocols were approved (project 06-04-15-230) by the Ethical Committee for Animal Experimentation of the School of Medicine of the University of Cadiz (license 07–9604) and the Dirección General de la Producción Agrícola y Ganadera of the Junta de Andalucía. Animal care and use procedures conformed to national and European Union regulations and guidelines (Spanish Royal Decree 53/2013 and EU Directive 2010/63/EU). The ARRIVE guidelines were used for the elaboration of this manuscript (Group, 2010).

Anesthesia and Instrumentation

Animals were premedicated with an intramuscular dose of xylazine (10 mg⋅kg–1) and ketamine (40 mg⋅kg–1). Then they were tracheotomized and their lungs mechanically ventilated in volume-controlled mode (Servo 900c, Siemens-Elema, Solna, Sweden), with 8 ml⋅kg–1 of tidal volume, positive end-expiratory pressure of 0 cmH2O, an inspiration to expiration ratio of 1:2, inspired oxygen fraction of 0.6, and a respiratory rate of 35–40 breaths⋅min–1 adjusted to maintain an end-tidal CO2 between 35 and 45 mmHg. The right internal jugular vein was catheterized for continuous sedation with ketamine (10–40 mg⋅kg–1⋅h–1) and midazolam (1–3 mg⋅kg–1⋅h–1). The muscular blockade was maintained with a rocuronium bromide infusion (0.6–1.2 mg⋅kg–1⋅h–1) (Quesenberry and Carpenter, 2012). Adequacy of anesthesia before neuromuscular blockade and through the experiment was evaluated by the absence of any significant blood pressure and/or heart rate change in response to an external noxious stimulus. A Ringers lactate solution (6 ml⋅kg–1⋅h–1) was administered as a maintenance fluid therapy. Animal temperature was continuously monitored by a rectal probe and maintained between 38 and 40°; using a heating pad. A 22G sterile polyethylene catheter was introduced into the right femoral artery and connected to a pressure transducer (TruWave, Edwards Lifesciences LLC, Irvine, CA, United States) zeroed against atmospheric pressure. Optimal damping of the arterial waveform was checked by a square wave test. The left femoral vein was used to administer vasoactive drugs and fluid bolus.

Hemodynamic Monitoring

A pediatric esophageal Doppler probe (KDP72; CardioQ Combi, Deltex Medical, Chichester, United Kingdom) was introduced into the esophagus until obtaining the best outline and maximal peak velocity of aortic blood waveform. Cardiac output (CO) was calculated using the minute distance of aortic blood flow, which represents the distance traveled by a column of blood in 1 min and is calculated by the Doppler system as the product of HR and the velocity-time integral of the aortic flow waveform. The peak velocity and maximum acceleration of blood flow were used as indexes of the left ventricular systolic function (Sabbah et al., 1986; Wallmeyer et al., 1988). The arterial pressure signal was transferred from the multi-parametric monitor (S/5, Datex-Ohmeda, Helsinki, Finland) to the Doppler system and automatically synchronized with the aortic blood flow waveform for pressure-flow analysis.

Evaluation of Arterial Load

A 3-element Windkessel model was used for characterizing the arterial system (Westerhof et al., 2009), consisting of systemic vascular resistance [SVR = mean arterial pressure (MAP)/CO]; arterial compliance (Cart = stroke volume / arterial pulse pressure) (Remington et al., 1948) and characteristic impedance (Zc). Zc represents the arterial input impedance in the absence of arterial wave reflections (Nichols and O’Rourke, 2005). Assuming that arterial reflections are negligible during early systole (Milnor, 1989; Nichols and O’Rourke, 2005), Zc was estimated as the slope of the early ejection pressure-flow relationship, using the ratio between the maximum of the first derivate of pressure and flow (Li, 1986; Lucas et al., 1988).

The effective arterial elastance (Ea) was used as a lumped parameter of arterial load accounting for both mean and pulsatile components (Kelly et al., 1992a):

Where RT is the total mean vascular resistance (SVR + Zc), ts and td are systolic and diastolic periods, respectively, and τ the diastolic time constant (τ = SVR × Cart) (Kelly et al., 1992a).

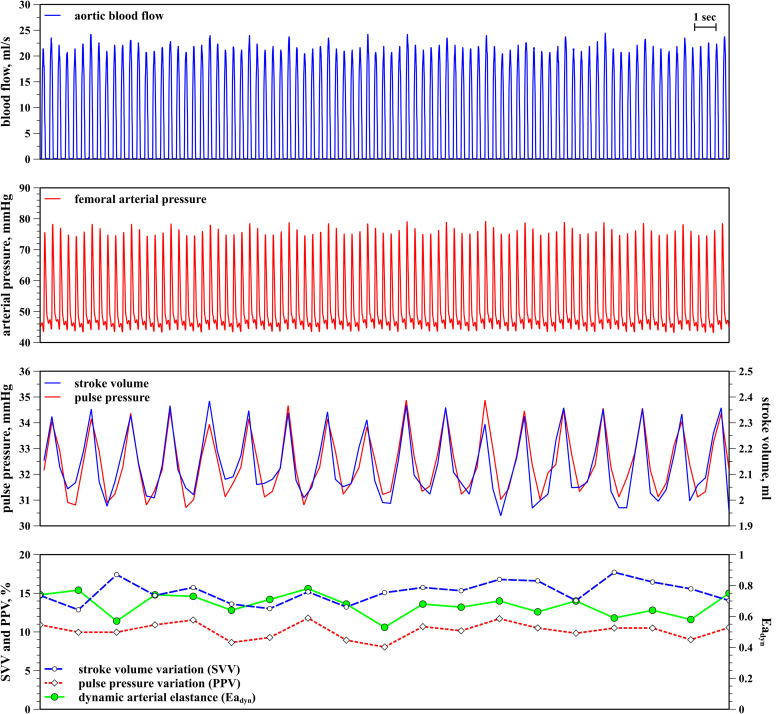

PPV, SVV, and Dynamic Arterial Elastance

PPV was calculated as the percentage changes in arterial pulse pressure during a ventilatory cycle as [(PPmax – PPmin)/(PPmax + PPmin)/2] × 100, where PPmax and PPmin represent the maximal and minimal arterial pulse pressure, respectively. The calculation of SVV was performed similarly. SVmax and SVmin were calculated by integrating the systolic component of aortic blood flow waveform, whereas PPV was derived from the femoral arterial pressure waveform. PPV and SVV values were simultaneously analyzed and averaged during 1 min using a custom Excel macro (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, United States) (Figure 1). Eadyn was calculated as beat-to-beat PPV/SVV averaged during 1 min (Monge Garcia et al., 2011).

FIGURE 1.

Calculation of pulse pressure variation (PPV), stroke volume variation (SVV), and dynamic arterial elastance (Eadyn). From top to bottom: aortic blood flow (blue); femoral arterial pressure (red); beat-to-beat stroke volume and arterial pulse pressure (pink and dark blue); stroke volume variation (SVV, dotted red line), pulse pressure variation (PPV, blue dashed line) and dynamic arterial elastance (Eadyn, solid green line).

Left Ventricular Energetics

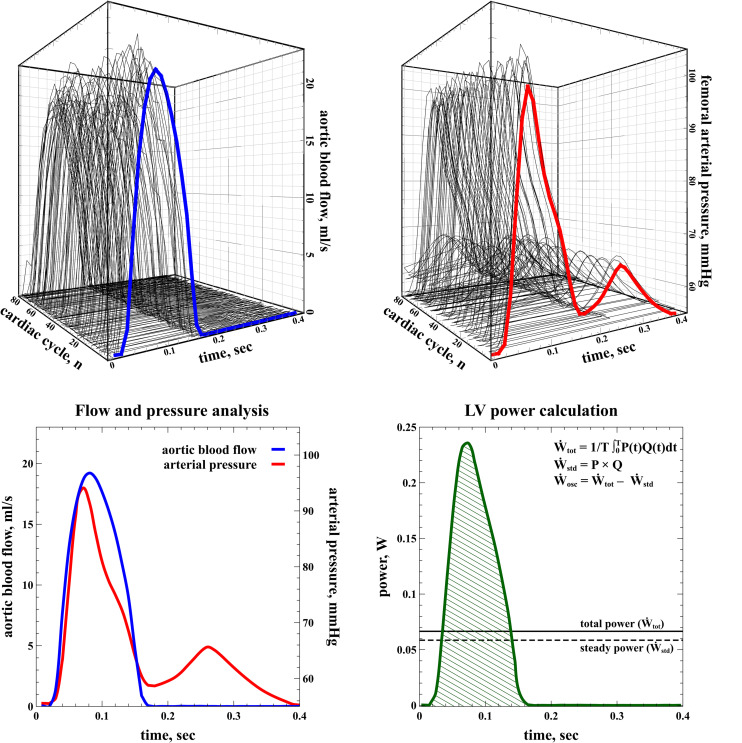

Left ventricular energetics were analyzed from the instantaneous pressure and flow recordings. Aortic blood flow and femoral arterial pressure waveforms were recorded simultaneously during at least 20 s at 180 Hz and ensemble-averaged, foot-to-foot aligned using the maximum of the second derivative (Vardoulis et al., 2013), and interpolated to the duration of the cardiac cycle to provide a representative waveform for analysis. An illustrative example of the signal processing is shown in Figure 2. The contribution of kinetic energy was considered negligible and not included in the analysis (Milnor, 1989).

FIGURE 2.

Calculation of left ventricular energetics. Aortic blood flow (top left, blue line) and arterial pressure waveforms (top right, red line) were ensembled-averaged (bottom, left) for analysis. The total LV power (Ẇtot) transferred to the systemic circulation was calculated as the time-averaged integral of the instantaneous product of pressure and flow during the whole cardiac period (bottom right, green shaded area). The difference between total power (Ẇtot) and steady power (Ẇstd, solid line) represents the extra expenditure of energy imposed by the pulsatile nature of the heart, i.e., the oscillatory power (Ẇosc, dashed line).

The left ventricular (LV) total power (Ẇtot) transferred to the systemic circulation was calculated as the time-averaged integral of the instantaneous product of blood pressure (P) by flow (Q) during the whole cardiac period (T):

The product of mean pressure by mean flow, or steady power (Ẇstd), corresponds to the energy maintaining forward blood flow and represents the fraction of Ẇtot useful for organ perfusion (O’Rourke, 1967; Milnor, 1989; Cholley and Le Gall, 2016).

The oscillatory power (Ẇosc) refers to the energy lost in pulsatile phenomena due to cardiac contractions:

Cardiovascular Efficiency

The oscillatory power fraction (%Osc) represents the portion of Ẇtot wasted in oscillatory power and quantifies the efficiency with which the external mechanical power was transferred into useful work from the LV to the arterial system (O’Rourke, 1967; Berger et al., 1995; Cholley and Le Gall, 2016). Therefore, the lower the %Osc, the more efficiently LV external work is delivered to the arterial system and converted into useful work for creating blood flow. %Osc has been used as a measure of the optimization of ventriculo-arterial coupling (O’Rourke, 1967; Cholley and Le Gall, 2016).

We also calculated the LV power necessary for generating one unit cardiac output for a given arterial load, as the energy efficiency ratio (EER) (Berger et al., 1995; Grignola et al., 2007):

Therefore, the lower the EER, the lower the energy required for generating blood flow for a given LV afterload.

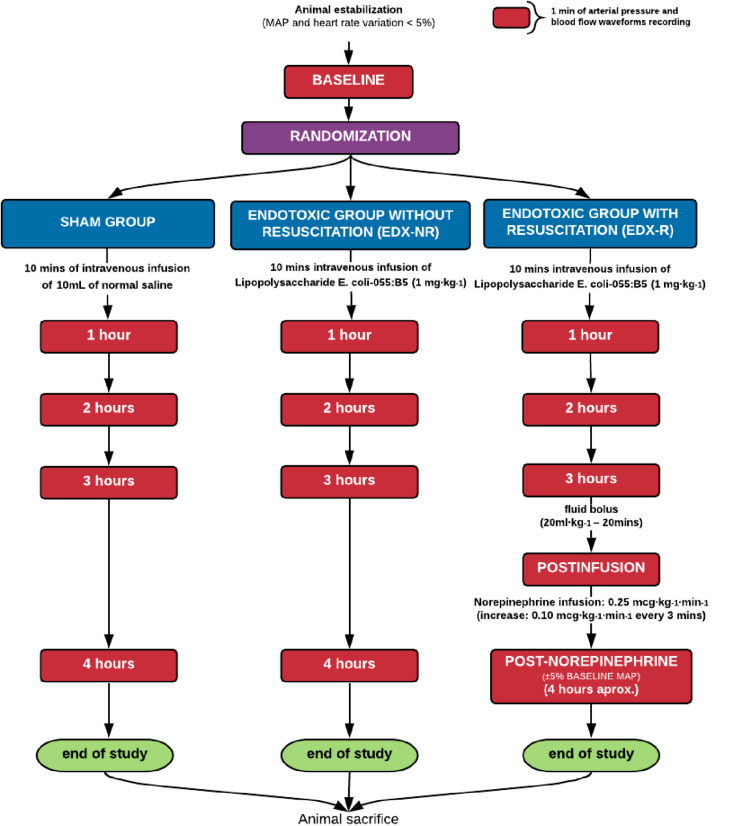

Experimental Protocol

After completion of the surgical procedures, animals were allowed to stabilize MAP and HR (variation < 5%) at least for 10 minutes. After that, they were assigned using a computer-generated random sequence to three groups (6 animals each): a sham-operated group (SHAM), a septic group (EDX), and a septic group with hemodynamic resuscitation (EDX-R). In septic animals, a purified lipopolysaccharide (LPS) prepared from Escherichia coli serotype 055:B5 (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) was intravenously infused over 10 min through the femoral vein (1 mg⋅kg–1 diluted in normal saline for a total volume of 8 ml, and flushed by 2 ml of normal saline to ensure a complete delivery). The dose and rate of LPS administration were previously established on a pilot experiment with 8 animals, in which the dose was varied from 1 to 2 mg⋅kg–1. SHAM animals received an equivalent amount of normal saline. Three hours after LPS infusion, animals in the EDX-R group received a fluid bolus of 20 ml⋅kg–1 for 10 min. A norepinephrine infusion started at 0.25 mcg⋅kg–1⋅min–1 was started after fluid administration if MAP was below the baseline level. Norepinephrine was increased by 0.10 mcg⋅kg–1⋅min–1 every 3 min until reaching a MAP value similar to the baseline level (±5% deviation). Hemodynamic measurements, aortic blood flow, and arterial pressure waveforms were recorded a least during 1 min at baseline and every hour up to 4 h after LPS or placebo administration. In EDX-R animals, measurements after fluid bolus (post-infusion) and norepinephrine infusion (which corresponds to 4 h after LPS infusion) were also obtained. After completion of the study protocol, animals were euthanized using a lethal dose of intravenous potassium chloride under deep anesthesia. Animal death was confirmed by verification of the absence of blood flow and arterial pressure tracings. A schematic description of the study protocol is shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Schematic representation of the study protocol.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± SD or median (25th to 75th interquartile). The normality of data was checked by the Shapiro Wilk test. Differences between groups at baseline were performed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and differences over time were assessed by two-way mixed ANOVA for repeated measurements. The Greenhouse–Geisser correction was used when the Mauchly test detected violation of sphericity. Whenever a significant interaction was found, pairwise comparison between groups was performed using a one-way ANOVA with the Tukey-Kramer test. Mixed-effect regression analyses were used to evaluate the relationship between Eadyn (the dependent variable) and arterial load, cardiac function variables, cardiac energetics, and indexes of cardiovascular efficiency (%Osc and EER) in septic shock animals (EDX and EDX-R groups). Models were constructed using individual animals and experimental groups as subjects for random factors, and experimental stages as repeated measurements with a heterogeneous first-order autoregressive covariance structure. This allowed us to consider the correlation between subjects and non-constant variability over time, which are not considered by the standard linear regression analysis. Model selection was based on the corrected Akaike’s Information Criteria, in which lower scores indicate superior fit (Fitzmaurice et al., 2011). Model parameters were estimated via the restricted maximum likelihood method, and the estimated fixed effect of each parameter quantified by using estimated value and standard error (SE). A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were two-tailed and performed using MedCalc Statistical Software version 19.1 (MedCalc Software bvba, Ostend, Belgium1; 2019) and SPPS (SPSS 21, SPPS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

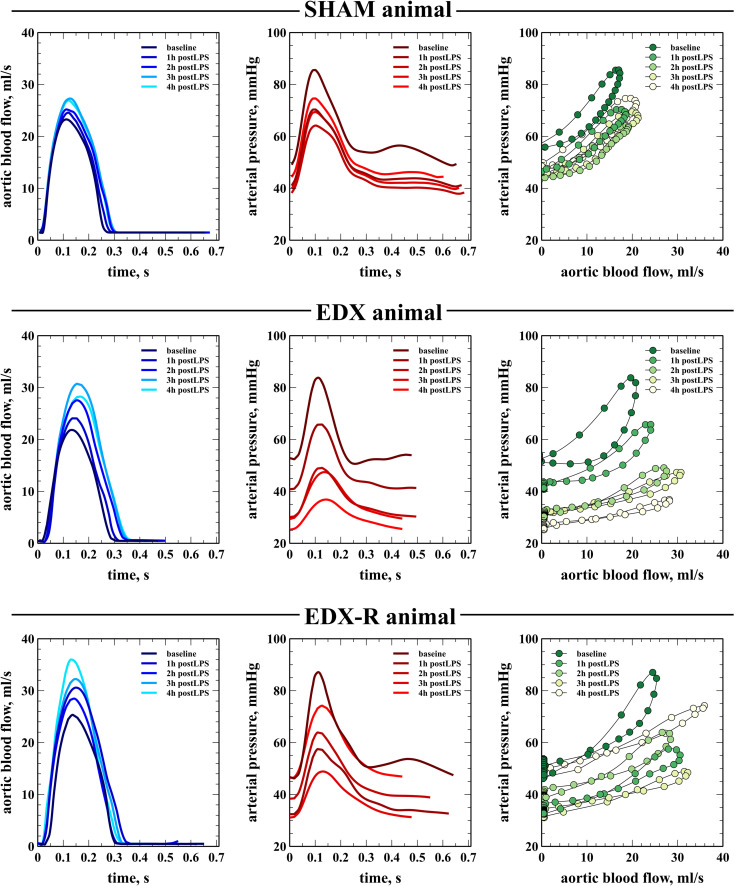

Hemodynamic Profile of Experimental Endotoxic Shock and Effects of Hemodynamic Resuscitation

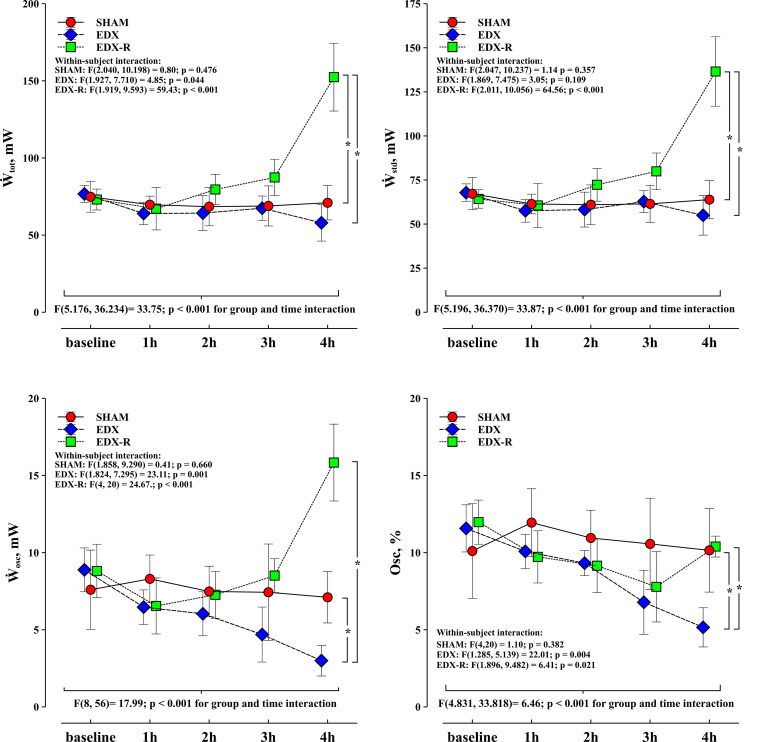

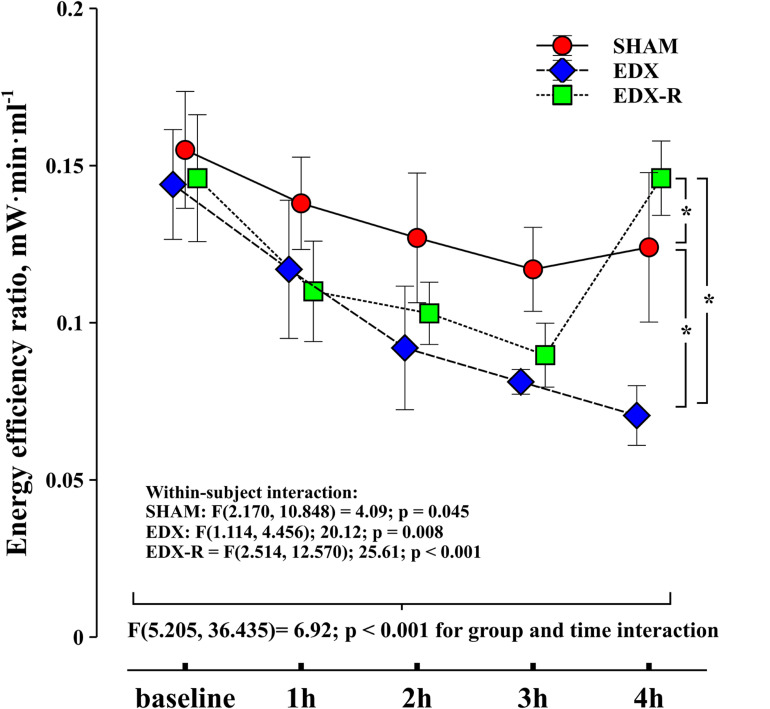

There were no significant differences between groups in all studied variables at baseline. The infusion of LPS resulted in a hyperdynamic hemodynamic profile with a progressive increase in CO secondary to a positive chronotropic response, a significant reduction in mean arterial pressure (35%), and a decreased arterial load (Table 1). This phenomenon was characterized by a progressive flattening of the pressure-flow relationship (Figure 4). Systolic function, as assessed by peak velocity of aortic blood flow, significantly increased in endotoxic shock animals. Although all experimental groups showed a significant decrease in the evolution of arterial load, the group and time interaction analysis showed that the changes in C and Zc were more pronounced in the EDX group when compared with the SHAM animals (Table 2). LPS reduced Ẇosc and slightly Ẇtot, but did not affect Ẇstd, which resulted in a better cardiovascular efficiency according to a lower Ẇosc/Ẇtot ratio (%Osc) and EER (Figures 5, 6).

TABLE 1.

Global hemodynamic changes during the experiment.

| Variables | Baseline* | 1 h | 2 h | 3 h | 4 ha | Time interaction | Group interaction | Group and time interaction |

| CO, l/min | ||||||||

| SHAM | 0.49 ± 0.06 | 0.51 ± 0.03 | 0.54 ± 0.03 | 0.58 ± 0.05 | 0.59 ± 0.10 | 0.057 | vs. EDX† | <0.001 |

| EDX | 0.54 ± 0.06 | 0.56 ± 0.07 | 0.70 ± 0.07 | 0.83 ± 0.07 | 0.81 ± 0.09 | <0.001 | vsEDX-R† | |

| EDX-R | 0.51 ± 0.08 | 0.61 ± 0.10 | 0.77 ± 0.07 | 0.99 ± 0.14 | 1.04 ± 0.12 | < 0.001 | vsSHAM† | |

| SV, ml | ||||||||

| SHAM | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | 3.1 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.6 | 0.176 | 0.147 | |

| EDX | 3.0 ± 0.5 | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 3.5 ± 0.8 | 3.5 ± 0.7 | 0.060 | ||

| EDX-R | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 0.005 | ||

| SAP, mmHg | ||||||||

| SHAM | 87 ± 13 | 76 ± 8 | 69 ± 10 | 65 ± 7 | 61 ± 6 | 0.010 | vs. EDX† | <0.001 |

| EDX | 82 ± 11 | 62 ± 11 | 50 ± 11 | 42 ± 4 | 42 ± 5 | 0.002 | vs. EDX-R† | |

| EDX-R | 85 ± 13 | 61 ± 11 | 57 ± 7 | 50 ± 8 | 77 ± 10 | < 0.001 | vsSHAM | |

| DAP, mmHg | ||||||||

| SHAM | 53 ± 6 | 46 ± 6 | 43 ± 7 | 40 ± 4 | 38 ± 3 | 0.006 | vs. EDX† | <0.001 |

| EDX | 48 ± 6 | 41 ± 7 | 32 ± 6 | 27 ± 3 | 26 ± 3 | 0.007 | vs. EDX-R | |

| EDX-R | 48 ± 7 | 37 ± 5 | 35 ± 3 | 29 ± 3 | 47 ± 6 | <0.001 | vsSHAM† | |

| MAP, mmHg | ||||||||

| SHAM | 63 ± 7 | 55 ± 6 | 51 ± 8 | 47 ± 5 | 46 ± 3 | 0.006 | vs. EDX† | <0.001 |

| EDX | 57 ± 7 | 47 ± 8 | 38 ± 8 | 34 ± 1 | 30 ± 3 | 0.007 | vs. EDX-R† | |

| EDX-R | 58 ± 8 | 45 ± 7 | 42 ± 4 | 38 ± 3 | 59 ± 5 | <0.001 | vsSHAM† |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. CO, cardiac output; DAP, diastolic arterial pressure; HR, heart rate; MAP, mean arterial pressure; SAP, systolic arterial pressure; SV, stroke volume; SHAM, sham-operated group; EDX, non-resuscitated septic rabbits; EDX-R, resuscitated septic rabbits. ∗Baseline values were similar between different experimental groups. aIn the EDX-R group, 4h refers after both fluid bolus and norepinephrine infusion. †p < 0.05 for between-group effects (Tukey-Kramer).

FIGURE 4.

Evolution of arterial pressure-flow relationship. Example of the evolution of blood flow (left column) and the arterial pressure waveform (middle column) and the pressure-flow loops (right column) in three animals from sham-operated group (SHAM), endotoxic group (EDX), and hemodynamic-resuscitated endotoxic group (EDX-R) during the study. In this latter group, 4h stage refers to after both fluid bolus and norepinephrine infusion. Pressure-flow loops were constructed using data from the shown aortic blood flow and arterial pressure waveforms on each experimental stage.

TABLE 2.

Arterial and cardiac variables during different stages of the experiment.

| Variables | Baseline* | 1h | 2h | 3h | 4ha | Time interaction | Group interaction | Group and time interaction |

| Arterial load variables | ||||||||

| Ea, mmHg/ml⋅10–1 | ||||||||

| SHAM | 0.83 ± 0.18 | 0.52 ± 0.09 | 0.43 ± 0.09 | 0.34 ± 0.04 | 0.36 ± 0.11 | 0.001 | 0.769 | |

| EDX | 0.67 ± 0.29 | 0.39 ± 0.16 | 0.22 ± 0.08 | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.021 | ||

| EDX-R | 0.68 ± 0.23 | 0.31 ± 0.09 | 0.23 ± 0.05 | 0.16 ± 0.04 | 0.24 ± 0.05 | 0.001 | ||

| C, ml/mmHg | ||||||||

| SHAM | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.006 | vs. EDX† | 0.001 |

| EDX | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 0.13 ± 0.03 | 0.19 ± 0.05 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 0.31 ± 0.04 | <0.001 | vsEDX-R | |

| EDX-R | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.15 ± 0.04 | 0.17 ± 0.06 | 0.21 ± 0.06 | 0.14 ± 0.03 | <0.001 | vsSHAM† | |

| Zc, dyn⋅s⋅cm–5⋅103 | ||||||||

| SHAM | 0.81 ± 0.24 | 0.70 ± 0.17 | 0.58 ± 0.17 | 0.49 ± 0.15 | 0.52 ± 0.20 | 0.013 | vs. EDX† | 0.020 |

| EDX | 0.84 ± 0.13 | 0.52 ± 0.11 | 0.35 ± 0.06 | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 0.001 | vs. EDX-R | |

| EDX-R | 0.85 ± 0.22 | 0.47 ± 0.10 | 0.39 ± 0.08 | 0.31 ± 0.12 | 0.45 ± 0.07 | 0.001 | vs. SHAM | |

| SVR, dyn⋅s⋅cm–5⋅103 | ||||||||

| SHAM | 10.55 ± 1.98 | 6.52 ± 1.01 | 5.72 ± 0.93 | 4.85 ± 0.33 | 4.87 ± 1.01 | <0.001 | 0.535 | |

| EDX | 8.66 ± 2.18 | 5.25 ± 1.68 | 3.25 ± 0.97 | 2.48 ± 0.19 | 2.25 ± 0.12 | 0.004 | ||

| EDX-R | 9.37 ± 2.52 | 4.52 ± 1.04 | 3.31 ± 0.45 | 2.32 ± 0.35 | 3.42 ± 0.50 | <0.001 | ||

| Cardiac variables | ||||||||

| HR, beats/min | ||||||||

| SHAM | 180 ± 28 | 187 ± 26 | 191 ± 24 | 188 ± 21 | 197 ± 24 | 0.039 | vs. EDX† | <0.001 |

| EDX | 182 ± 20 | 202 ± 22 | 222 ± 29 | 243 ± 39 | 237 ± 39 | 0.014 | vs. EDX-R | |

| EDX-R | 169 ± 17 | 178 ± 15 | 217 ± 40 | 234 ± 41 | 256 ± 18 | 0.004 | vs. SHAM† | |

| Accel, m/s2 | ||||||||

| SHAM | 6.47 ± 0.87 | 6.55 ± 0.47 | 6.58 ± 0.54 | 7.09 ± 0.58 | 7.02 ± 1.07 | 0.303 | 0.057 | |

| EDX | 6.41 ± 0.69 | 6.19 ± 0.84 | 6.81 ± 0.39 | 7.29 ± 1.00 | 6.70 ± 0.77 | 0.107 | ||

| EDX-R | 6.95 ± 0.81 | 6.87 ± 0.92 | 7.51 ± 0.59 | 8.93±.03 | 8.96 ± 1.42 | 0.018 | ||

| PV, ms/s | ||||||||

| SHAM | 92.2 ± 15.6 | 94.1 ± 10.4 | 97.0 ± 11.9 | 103.8 ± 14.3 | 101.6 ± 17.5 | 0.154 | vs. EDX† | <0.001 |

| EDX | 98.3 ± 8.9 | 101.1 ± 17.9 | 115.8 ± 22.3 | 128.5 ± 24.3 | 123.8 ± 26.0 | 0.007 | vs. EDX-R† | |

| EDX-R | 97.8 ± 13.4 | 108.1 ± 17.4 | 123.3 ± 6.9 | 150.5 ± 13.6 | 168 ± 16.5 | <0.001 | vsSHAM† | |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Accel, mean acceleration of aortic blood flow; C, net arterial compliance; Ea, effective arterial elastance; HR, heart rate; PV = peak velocity of aortic blood flow; SVR, systemic vascular resistance; Zc, characteristic impedance; SHAM, sham-operated group; EDX, septic group without hemodynamic resuscitation; EDX-R, hemodynamic resuscitated septic group. ∗Baseline values were similar between different experimental groups. aIn the EDX-R group, 4h refers after hemodynamic resuscitation (both fluid bolus and norepinephrine infusion). †p < 0.05 for between-group effects (Tukey-Kramer).

FIGURE 5.

Evolution of left ventricular energetics. Changes in left ventricular total work (Ẇtot), steady power (Ẇstd), oscillatory power (Ẇosc) and oscillatory power fraction (Osc) in the three experimental groups: Experimental arms: sham-operated group (SHAM), resuscitated endotoxic group (EDX), and hemodynamic-resuscitated group (EDX-R). Values are presented as mean ± SD. Differences in time course between groups: *p < 0.05.

FIGURE 6.

Evolution of energy efficiency ratio (EER). Experimental arms: sham-operated group (SHAM), resuscitated endotoxic group (EDX), and hemodynamic-resuscitated group (EDX-R). Values are presented as mean ± SD. Differences in time course between groups: *p < 0.05.

The effects of hemodynamic resuscitation in the EDX-R group are summarized in Table 3. Fluid bolus increased CO and MAP by 19 and 18%, respectively, although MAP remained significantly lower than the baseline value (58 ± 8 vs. 45 ± 4 mmHg; p = 0.011). Norepinephrine was therefore required in all EDX-R animals to restore MAP to a similar value that baseline levels (58 ± 8 vs. 59 ± 5 mmHg; p = 0.504). Overall, hemodynamic resuscitation resulted in a higher cardiac energetic cost and lower cardiovascular efficiency (higher EER and %Osc).

TABLE 3.

Effects of fluid bolus and norepinephrine in hemodynamic, arterial variables and cardiac energetics in resuscitated septic animals (EDX-R group).

| 3 h post-LPS | After fluid bolus (20 mL/Kg) | After norepinephrine (4 h post-LPS) | |

| Hemodynamic variables | |||

| CO, l/min | 0.99 ± 0.14 | 1.16 ± 0.09* | 1.04 ± 0.12*† |

| SV, ml | 4.3 ± 0.6 | 4.7 ± 0.6* | 4.1 ± 0.6 |

| SAP, mmHg | 50 ± 8 | 61 ± 10* | 77 ± 10*† |

| DAP, mmHg | 29 ± 3 | 35 ± 2* | 47 ± 6*† |

| MAP, mmHg | 38 ± 3 | 45 ± 4* | 59 ± 5*† |

| SVV, % | 22 ± 4 | 20 ± 3 | 24 ± 3† |

| PPV, % | 30 ± 7 | 19 ± 7* | 21 ± 6* |

| Eadyn | 1.38 ± 0.32 | 0.93 ± 0.24* | 0.87 ± 0.15* |

| Arterial variables | |||

| Ea, mmHg/ml⋅10–1 | 0.16 ± 0.04 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 0.24 ± 0.05 |

| C, ml/mmHg | 0.21 ± 0.06 | 0.19 ± 0.07 | 0.14 ± 0.03 |

| Zc, dyn⋅s⋅cm–5⋅103 | 0.31 ± 0.12 | 0.35 ± 0.13 | 0.45 ± 0.07 |

| SVR, dyn⋅s⋅cm–5⋅103 | 2.32 ± 0.35 | 2.32 ± 0.27 | 3.42 ± 0.50*† |

| Cardiac variables | |||

| HR, beats/min | 234 ± 41 | 251 ± 25 | 256 ± 18 |

| Accel, m/s2 | 8.93 ± 1.03 | 9.91 ± 0.63 | 8.96 ± 1.42 |

| PV, m/s | 150.5 ± 13.6 | 171.7 ± 11.7* | 168 ± 16.5† |

| Cardiac energetics | |||

| Ẇtot, mW | 87 ± 12 | 128 ± 19* | 152 ± 22*† |

| Ẇstd, mW | 80 ± 10 | 115 ± 16* | 137 ± 20*† |

| Ẇosc, mW | 7 ± 2 | 13 ± 4 | 16 ± 2* |

| %Osc, % | 9 ± 2 | 10 ± 2 | 10 ± 1* |

| EER, mW⋅min⋅ml–1 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.11 ± 0.01 | 0.15 ± 0.01*† |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Accel, maximal acceleration of aortic blood flow; C, net arterial compliance; CO, cardiac output; DAP, diastolic arterial pressure; Ea, effective arterial elastance; Eadyn, dynamic arterial elastance; EER, energy efficiency ratio (Ẇtot/CO); HR, heart rate; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MAP, mean arterial pressure; PPV, arterial pulse pressure variation; PV, peak velocity of aortic blood flow; SAP, systolic arterial pressure; SV, stroke volume; SVV, stroke volume variation; SVR, systemic vascular resistance; Ẇosc, left ventricular oscillatory power; Ẇstd, left ventricular steady power; Ẇtot, left ventricular total power; Zc, characteristic impedance; %Osc, oscillatory power fraction (Ẇosc/Ẇtot). *p < 0.05 vs. 3h postLPS stage, †p < 0.05 vs. After fluid bolus stage (Bonferroni corrected).

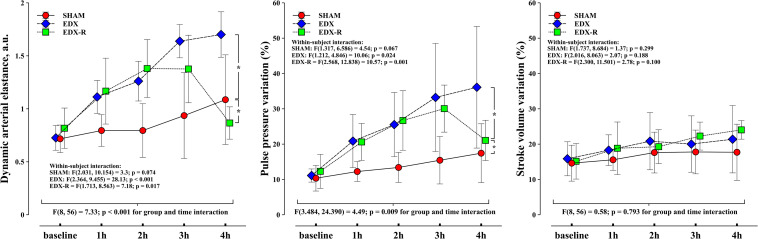

Evolution of PPV, SVV, and Eadyn

Figure 7 shows the development of Eadyn, PPV, and SVV among different experimental groups. Eadyn increased in both EDX and EDX-R groups because of a significant increase in PPV but decreased in EDX-R animals after fluid administration (Table 3). The time course of Eadyn did not reach statistical significance in SHAM animals.

FIGURE 7.

Evolution of dynamic arterial elastance, pulse pressure variation (PPV) and stroke volume variation (SVV). Experimental arms: sham-operated group (SHAM), resuscitated endotoxic group (EDX), and hemodynamic-resuscitated group (EDX-R). Values are presented as mean ± SD. Differences in time course between groups: *p < 0.05.

Relationship Between Eadyn, Arterial and Cardiac Factors During Septic Shock and Hemodynamic Resuscitation

When analyzing the relationship of different variables of arterial load, cardiac function, cardiac energetics, and cardiovascular efficiency indexes on Eadyn on endotoxic septic animals (EDX and EDX-R), the linear-mixed regression analysis revealed that Eadyn were related to both arterial and cardiac factors (Table 4). The overall impact of LV afterload, as assessed by Ea, was inversely associated with Eadyn (estimate: −1.082; 95% confidence interval (CI): −1.417 to −0.748; p < 0.001), being Zc the only component of arterial load associated to Eadyn (Table 4). On the other hand, among cardiac function variables, only heart rate was positively related to Eadyn. When a linear-mixed model was used with Zc and HR as fixed effects and Eadyn as the dependent variable, their association with Eadyn remained significant, and the coefficient of determination between predicted values and Eadyn was r2 = 0.67.

TABLE 4.

Mixed-effects regression model for the interaction between Eadyn and arterial load, cardiac, cardiac energetics and cardiovascular efficiency indexes in endotoxic shock animals (EDX and EDX-R groups).

| Fixed effects | β estimate | 95% confidence interval | p-value |

| Arterial load variables | |||

| SVR, dyn⋅s⋅cm–5⋅103 | 0.009 | −0.056 to 0.075 | 0.770 |

| C, ml/mmHg | 0.509 | −1.534 to 2.552 | 0.611 |

| Zc, dyn⋅s⋅cm–5⋅103 | −1.053 | −1.896 to −0.209 | 0.017 |

| Cardiac related variables | |||

| Heart rate, beats/min | 0.006 | 0.003 to 0.008 | 0.002 |

| Accel, ms/s2 | 0.047 | −0.044 to 0.137 | 0.101 |

| PV, m/s | −0.010 | −0.050 to 0.029 | 0.599 |

| Cardiac energetics variables | |||

| Ẇstd, W | 0.017 | 0.007 to 0.027 | <0.001 |

| Ẇosc, W | −0.125 | −0.174 to −0.076 | <0.001 |

| Cardiovascular efficiency variables | |||

| %Osc | −0.101 | −0.137 to −0.064 | <0.001 |

| EER, W⋅s⋅ml–1 | −9.494 | −11.964 to −7.024 | <0.001 |

Accel, maximal acceleration of aortic blood flow; C, arterial compliance; Eadyn, dynamic arterial elastance; EER, energy efficiency ratio; PV, peak velocity of aortic blood flow; SVR, systemic vascular resistance; Ẇosc, left ventricular oscillatory work; Ẇstd, left ventricular steady work; Zc, characteristic impedance; %Osc, oscillatory power fraction. Estimates reflect the average change in Eadyn per unit increase of the fixed effect. Mixed-effect regression models were constructed using arterial variables (SVR, C and Zc), cardiac variables (HR, Accel and PV), cardiac energetic variables (Ẇstd and Ẇosc), and cardiovascular efficiency indexes (%Osc and EER) as independent variables.

Relationship Between Eadyn, Cardiac Energetics and Cardiovascular Efficiency During Septic Shock and Hemodynamic Resuscitation

The relationship between cardiac energetics and Eadyn in septic shock animals (EDX and EDX-R) is shown in Table 4. Although no significant association between Eadyn and Ẇtot was found (estimate: 0.003; 95%CI: −0.003 to 0.011; p = 0.279), its components Ẇstd and Ẇosc were independently associated: while Ẇstd was positively associated with Eadyn, Ẇosc did so negatively. Eadyn was also related to both estimates of cardiovascular efficiency: %Osc and EER. Accordingly, the better the efficiency (i.e., the lower EER and %Osc), the higher the Eadyn.

Discussion

In this experimental animal study, Eadyn increased during endotoxic septic shock and decreased after hemodynamic resuscitation. The evolution of Eadyn was associated with both cardiac and arterial factors and was significantly associated with cardiovascular efficiency: the higher the efficiency of the cardiovascular system, the higher the Eadyn.

Relationship Between Eadyn and Cardiac and Arterial Variables

We found that heart rate and Zc, which represent the pulsatile component of the LV hydraulic workload (Milnor, 1989), were the main variables associated to Eadyn in septic animals. Moreover, when considering only HR and Zc, 67% of the actual Eadyn values could be predicted in the septic animals. However, considering that these two variables cannot account for all the Eadyn values, we cannot exclude that other factors not contemplated in our arterial load and cardiac function assessment may have impacted the observed Eadyn.

These findings corroborate previous results about the compound nature of Eadyn and the impact of both cardiac and arterial factors (Monge Garcia et al., 2020). While net changes in Ea, a net measure of LV afterload, were negatively associated with Eadyn, variations in heart rate did so positively (Monge Garcia et al., 2017; de Courson et al., 2019). Our results also confirm earlier observations about the impact of endotoxic septic shock on the PPV/SVV relationship. In a model of LPS-induced pneumonia in mechanically ventilated rats, Cherpanath et al. (2014) observed that the ratio PPV/SVV was higher in LPS-treated compared with untreated rats. Septic animals also showed a significant decrease in arterial tone, as reflected by an increase in net arterial compliance (Cherpanath et al., 2014). This study, together with our previous observations about the impact of changes in arterial load (Monge Garcia et al., 2017), support the notion that Eadyn does not represent a real measure of central arterial tone nor an index of the arterial stiffness, and that the concept of Eadyn as a variable describing LV afterload should be avoided (Monge Garcia et al., 2020).

Relationship Between LV Energetics and Eadyn

The force that pumps blood from the heart to the peripheral circulation is determined by an energy gradient that comprises a kinetic, gravitational, and a potential element (Burton, 1972). During a contraction, the heart works increasing potential energy and, in a much smaller proportion, kinetic energy. This work is distributed to the systemic circulation generating the energy gradient that drives blood flow through to the systemic circulation and delivers adequate transport for oxygen and nutrients to the tissues. In turn, the hydraulic work generated by the ventricle can be divided into two components: steady and oscillatory work. While Ẇstd represents the work per unit time that effectively contributes to blood flow and peripheral perfusion, Ẇosc represents the unavoidable consequence of the pulsatile nature of the heart’s activity and is considered “wasted” energy (Milnor, 1989). An efficient cardiovascular system would then minimize the oscillatory component of LV mechanical work. The ratio Ẇosc/Ẇtot (i.e., %Osc) becomes then a sort of index of the efficiency of the LV mechanical power dissipation in the arterial system (O’Rourke, 1967). Moreover, as the ability of the heart as a pump depends not only on the myocardial performance but also on the physical properties of the arterial system, %Osc represents also a measure of the efficiency of the matching between the heart and the arterial system (O’Rourke, 1967; Milnor, 1989).

While in normal conditions Ẇosc accounts only about 10% of the total LV mechanical work (O’Rourke, 1967; Nichols et al., 1986), which manifests the optimal efficiency of the arterial system for buffering cardiac pulsations, factors altering arterial load or heart rate are known to affect this balance (O’Rourke, 1967; Cox, 1974). In our study, the overall %Osc at baseline was 11 ± 2%, similar to that reported in previous animal studies (O’Rourke, 1967; Cholley et al., 1995). While in SHAM animals %Osc remained unchanged, it significantly decreased during LPS infusion and increased after hemodynamic resuscitation. These modifications agree with the known relationship between Zc and HR and %Osc. Previous studies have shown that, when Zc decreases or heart rate increases, %Osc decreases (O’Rourke, 1967; Cox, 1974; Nichols et al., 1977; Laskey et al., 1985). In our study, septic animals showed a progressive and significant decrease in Zc and increased heart rate. Not surprisingly, these same factors were the main determinants of the Eadyn changes in septic animals. As Eadyn was directly related to Ẇstd but inversely to Ẇosc, Eadyn reflects then not only the net LV mechanical work but how this work is generated. Therefore, changes in Osc% and EER were inversely associated with Eadyn variations. Accordingly, when cardiovascular efficiency increases, so does the Eadyn (Monge Garcia et al., 2020).

Our results differ from those reported by Cholley et al. (1995) in a similar study. These authors found that a lower dose of LPS (600 μg⋅kg–1) resulted in a hypodynamic hemodynamic profile characterized by low cardiac output, arterial hypotension, and increased %Osc. Septic shock was also associated with a lower heart rate and higher Zc resulting from the aortic smooth muscle contraction and aortic wall edema. These discrepancies may likely reflect differences in the experimental setup, the dose of LPS, and the anesthetic regimen used (pentobarbital vs. ketamine and midazolam). However, even if our results differ in how LPS affects hemodynamics, both are coheren t on the physiological mechanisms and how these factors are known to affect %Osc (O’Rourke, 1967; Cox, 1974; Nichols et al., 1977; Kelly et al., 1992b).

Clinical Implications

Ventriculo-arterial uncoupling and impaired LV efficiency is a frequent phenomenon in septic shock (Yan et al., 2017; Guarracino et al., 2019; Pinsky and Guarracino, 2020). The assessment of ventriculo-arterial coupling in these patients may help to determine the underlying mechanism of cardiovascular failure and to predict the effectiveness of the hemodynamic therapies (Guarracino et al., 2019). Therefore, considering the crucial role of ventriculo-arterial coupling and LV efficiency in septic shock, the continuous assessment of Eadyn as an index for monitoring cardiovascular mechanical efficiency becomes therefore evident. However, the clinical usefulness of Eadyn as an easily measured bedside tool for monitoring VAC and LV efficiency requires further validation.

Limitations

Our evaluation of the cardiovascular efficiency was based on the analysis of the instantaneous arterial pressure-aortic blood flow relationship (Milnor, 1989). This analysis, however, does not represent the actual LV mechanical efficiency since it does not consider myocardial oxygen consumption (Suga et al., 1981). Moreover, because of our simplified assessment of LV performance, we cannot determine the actual impact of LPS on myocardial performance, which would have required the invasive measurements of LV volume and pressure. However, we have recently demonstrated that Eadyn is significantly related to ventriculo-arterial coupling and LV efficiency using the data obtained from the LV pressure-volume analysis by the classical conductance catheter technique (Monge Garcia et al., 2018). Our current results agree with the observations made in this study. Nevertheless, even if LPS infusion was associated with an improved transfer of the power from the LV to the arterial system, we cannot confirm that this condition was only related to a better myocardial contractility. As LPS can alter not only LV contractility but also loading conditions (Pinsky and Rico, 2000; Jianhui et al., 2010), the decreased arterial load in septic animals may have played an essential role in the improved power transfer efficiency (O’Rourke, 1967). A low %Osc indicates therefore that, for a given LV myocardial performance, the arterial load was relatively lower. Thus, even if %Osc does not directly describe the ventricular-arterial coupling variables, it represents an index of the efficiency of the cardiovascular system (Berger et al., 1995; Cholley and Le Gall, 2016).

Conclusion

During experimental endotoxic shock, Eadyn changes were associated with arterial and cardiac factors and significantly related to cardiovascular efficiency: the higher the efficiency of the cardiovascular system on delivering the energy to the arterial system for sustaining blood flow, the higher the Eadyn. Therefore, Eadyn may be a valuable index for monitoring cardiovascular mechanical efficiency.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article are available to any qualified researcher from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committee for Animal Experimentation of the School of Medicine of the University of Cadiz (license 07–9604) and the Dirección General de la Producción Agrícola y Ganadera of the Junta de Andalucía.

Author Contributions

MMG conceived and designed the study, participated in the experiments, performed the statistical analysis, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. PG, PS, MG, and AG and participated in the experiments, interpreted the data, and helped to draft the manuscript. AM and AR have made substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of data, have been involved in drafting the manuscript, and contributed to its critical review. MC contributed to the conception and design of the study, interpreted the data, wrote, and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

MMG has received Honoraria and/or Travel Expenses from Edwards Lifesciences and Deltex Medical. AG has received Honoraria and/or Travel Expenses from Edwards Lifesciences. AR has received Honoraria and is on the advisory board for LiDCO, Honoraria for Covidien, Edwards Lifesciences, and Cheetah. MC in the last 5 years received Honoraria and/or Travel Expenses from Edwards Lifesciences, LiDCO, Cheetah, Bmeye, Masimo, and Deltex. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Carlos Costela Villodres, from the Servicio Central de Experimentación y Producción Animal (SEPA) of the University of Cádiz, for his valuable technical assistance. Dr. Arnoldo Santos Oviedo for his technical aid and useful comments. This manuscript has been released as a pre-print at Research Square (Monge García et al., 2020).

Abbreviations

- Eadyn

dynamic arterial elastance

- PPV

pulse pressure variation

- SVV

stroke volume variation

- HR

heart rate

- CO

cardiac output

- SVR

systemic vascular resistance

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- C

arterial compliance

- Zc

characteristic impedance

- Ea

effective arterial elastance

- RT

total mean vascular resistance

- τ

diastolic time constant

- LV

left ventricular

- Ẇtot

left total ventricular power

- P

blood pressure

- PV

peak velocity of aortic blood flow

- Q

aortic blood flow

- T

cardiac period

- Ẇstd

LV steady power

- Ẇosc

LV oscillatory power

- %Osc

oscillatory power fraction

- EER

energy efficiency ratio

- SHAM

sham-operated group

- EDX

endotoxic group without hemodynamic resuscitation

- EDX-R

endotoxic group with hemodynamic resuscitation

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- SE

standard error

- CI

confidence interval.

Funding. This work was supported by the St George’s University of London, United Kingdom, and performed at the Servicio Central de Experimentación y Producción Animal (SEPA) of the University of Cádiz, Cádiz, Spain.

References

- Asanoi H., Sasayama S., Kameyama T. (1989). Ventriculoarterial coupling in normal and failing heart in humans. Circ. Res. 65 483–493. 10.1161/01.res.65.2.483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger D. S., Li J. K., Noordergraaf A. (1995). Arterial wave propagation phenomena, ventricular work, and power dissipation. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 23 804–811. 10.1007/bf02584479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton A. C. (1972). Physiology and biophysics of the circulation; an introductory text. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Cherpanath T. G., Smeding L., Lagrand W. K., Hirsch A., Schultz M. J., Groeneveld J. A. (2014). Pulse pressure variation does not reflect stroke volume variation in mechanically ventilated rats with lipopolysaccharide-induced pneumonia. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 41 98–104. 10.1111/1440-1681.12187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cholley B., Le Gall A. (2016). Ventriculo-arterial coupling: the comeback? J. Thorac. Dis. 8 2287–2289. 10.21037/jtd.2016.08.34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cholley B. P., Lang R. M., Berger D. S., Korcarz C., Payen D., Shroff S. G. (1995). Alterations in systemic arterial mechanical properties during septic shock: role of fluid resuscitation. Am. J. Physiol. 269 H375–H384. 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.1.H375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox R. H. (1974). Determinants of systemic hydraulic power in unanesthetized dogs. Am. J. Physiol. 226 579–587. 10.1152/ajplegacy.1974.226.3.579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Backer D., Creteur J., Preiser J. C., Dubois M. J., Vincent J. L. (2002). Microvascular blood flow is altered in patients with sepsis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 166 98–104. 10.1164/rccm.200109-016oc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Courson H., Boyer P., Grobost R., Lanchon R., Sesay M., Nouette-Gaulain K., et al. (2019). Changes in dynamic arterial elastance induced by volume expansion and vasopressor in the operating room: a prospective bicentre study. Ann. Intensive. Care 9:117. 10.1186/s13613-019-0588-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzmaurice G. M., Laird N. M., Ware J. H. (2011). Modeling the covariance in Applied longitudinal analyss, 2nd Edn, (Hoboken, N.J: Wiley; ), 165–188. 10.1002/9781119513469 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grignola J. C., Gines F., Bia D., Armentano R. (2007). Improved right ventricular-vascular coupling during active pulmonary hypertension. Int. J. Cardiol. 115 171–182. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Group N. C. R. R. G. W. (2010). Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. J. Physiol. 588 2519–2521. 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.192278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarracino F., Baldassarri R., Pinsky M. R. (2013). Ventriculo-arterial decoupling in acutely altered hemodynamic states. Crit. Care 17:213. 10.1186/cc12522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarracino F., Bertini P., Pinsky M. R. (2019). Cardiovascular determinants of resuscitation from sepsis and septic shock. Crit. Care 23:118. 10.1186/s13054-019-2414-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarracino F., Ferro B., Morelli A., Bertini P., Baldassarri R., Pinsky M. R. (2014). Ventriculoarterial decoupling in human septic shock. Crit. Care 18:R80. 10.1186/cc13842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jianhui L., Rosenblatt-Velin N., Loukili N., Pacher P., Feihl F., Waeber B., et al. (2010). Endotoxin impairs cardiac hemodynamics by affecting loading conditions but not by reducing cardiac inotropism. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 299 H492–H501. 10.1152/ajpheart.01135.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly R. P., Ting C. T., Yang T. M., Liu C. P., Maughan W. L., Chang M. S., et al. (1992a). Effective arterial elastance as index of arterial vascular load in humans. Circulation 86 513–521. 10.1161/01.cir.86.2.513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly R. P., Tunin R., Kass D. A. (1992b). Effect of reduced aortic compliance on cardiac efficiency and contractile function of in situ canine left ventricle. Circ. Res. 71 490–502. 10.1161/01.res.71.3.490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskey W. K., Kussmaul W. G., Martin J. L., Kleaveland J. P., Hirshfeld J. W., Jr., Shroff S. (1985). Characteristics of vascular hydraulic load in patients with heart failure. Circulation 72 61–71. 10.1161/01.cir.72.1.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J. K. (1986). Time domain resolution of forward and reflected waves in the aorta. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 33 783–785. 10.1109/tbme.1986.325903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas C. L., Wilcox B. R., Ha B., Henry G. W. (1988). Comparison of time domain algorithms for estimating aortic characteristic impedance in humans. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 35 62–68. 10.1109/10.1337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milnor W. R. (1989). Hemodynamics. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Monge Garcia M., Gracia Romero M., Gil Cano A., Aya H. D., Rhodes A., Grounds R., et al. (2014). Dynamic arterial elastance as a predictor of arterial pressure response to fluid administration: a validation study. Crit. Care 18:626. 10.1186/s13054-014-0626-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monge Garcia M. I., Gil Cano A., Gracia Romero M. (2011). Dynamic arterial elastance to predict arterial pressure response to volume loading in preload-dependent patients. Crit. Care 15:R15. 10.1186/cc9420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monge Garcia M. I., Guijo Gonzalez P., Gracia Romero M., Gil Cano A., Rhodes A., Grounds R. M., et al. (2017). Effects of arterial load variations on dynamic arterial elastance: an experimental study. Br. J. Anaesth. 118 938–946. 10.1093/bja/aex070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monge García M. I., Guijo González P., Saludes Orduña P., Gracia Romero M., Gil Cano A., Messina A., et al. (2020). Dynamic arterial elastance during experimental endotoxic septic shock. Berlin: Springer; 10.21203/rs.3.rs-26370/v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monge Garcia M. I., Jian Z., Hatib F., Settels J. J., Cecconi M., Pinsky M. R. (2020). Dynamic Arterial Elastance as a Ventriculo-Arterial Coupling Index: An Experimental Animal Study. Front. Physiol. 11:284. 10.3389/fphys.2020.00284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monge Garcia M. I., Jian Z., Settels J. J., Hatib F., Cecconi M., Pinsky M. R. (2018). Reliability of effective arterial elastance using peripheral arterial pressure as surrogate for left ventricular end-systolic pressure. J. Clin. Monit. Comput. 33(5), 803–813. 10.1007/s10877-018-0236-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols W. W., Conti C. R., Walker W. E., Milnor W. R. (1977). Input impedance of the systemic circulation in man. Circ. Res. 40 451–458. 10.1161/01.res.40.5.451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols W. W., O’Rourke M. (2005). McDonald’s Blood Flow in Arteries: Theoretical, Experimental and Clinical principles. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nichols W. W., O’rourke M. F., Avolio A. P., Yaginuma T., Pepine C. J., Conti C. R. (1986). Ventricular/vascular interaction in patients with mild systemic hypertension and normal peripheral resistance. Circulation 74 455–462. 10.1161/01.cir.74.3.455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke M. F. (1967). Steady and pulsatile energy losses in the systemic circulation under normal conditions and in simulated arterial disease. Cardiovasc. Res. 1 313–326. 10.1093/cvr/1.4.313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsky M. R. (1997). The hemodynamic consequences of mechanical ventilation: an evolving story. Intensive Care Med. 23 493–503. 10.1007/s001340050364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsky M. R. (2012). Heart lung interactions during mechanical ventilation. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 18 256–260. 10.1097/mcc.0b013e3283532b73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsky M. R., Guarracino F. (2020). How to assess ventriculoarterial coupling in sepsis. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 26 313–318. 10.1097/mcc.0000000000000721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsky M. R., Rico P. (2000). Cardiac contractility is not depressed in early canine endotoxic shock. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 161 1087–1093. 10.1164/ajrccm.161.4.9904033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesenberry K. E., Carpenter J. W. (2012). Ferrets, rabbits, and rodents : clinical medicine and surgery. St. Louis, Mo: Elsevier/Saunders. [Google Scholar]

- Remington J. W., Noback C. R., Hamilton W. F., Gold J. J. (1948). Volume elasticity characteristics of the human aorta and prediction of the stroke volume from the pressure pulse. Am. J. Physiol. 153 298–308. 10.1152/ajplegacy.1948.153.2.298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbah H. N., Khaja F., Brymer J. F., Mcfarland T. M., Albert D. E., Snyder J. E., et al. (1986). Noninvasive evaluation of left ventricular performance based on peak aortic blood acceleration measured with a continuous-wave Doppler velocity meter. Circulation 74 323–329. 10.1161/01.cir.74.2.323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga H., Hayashi T., Shirahata M. (1981). Ventricular systolic pressure-volume area as predictor of cardiac oxygen consumption. Am. J. Physiol. 240 H39–H44. 10.1152/ajpheart.1981.240.1.H39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunagawa K., Maughan W. L., Burkhoff D., Sagawa K. (1983). Left ventricular interaction with arterial load studied in isolated canine ventricle. Am. J. Physiol. 245 H773–H780. 10.1152/ajpheart.1983.245.5.H773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardoulis O., Papaioannou T. G., Stergiopulos N. (2013). Validation of a novel and existing algorithms for the estimation of pulse transit time: advancing the accuracy in pulse wave velocity measurement. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 304 H1558–H1567. 10.1152/ajpheart.00963.2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieillard-Baron A., Cecconi M. (2014). Understanding cardiac failure in sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 40 1560–1563. 10.1007/s00134-014-3367-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallmeyer K., Wann L. S., Sagar K. B., Czakanski P., Kalbfleisch J., Klopfenstein H. S. (1988). The effect of changes in afterload on Doppler echocardiographic indexes of left ventricular performance. J. Am. Soc. Echocard. 1 135–140. 10.1016/s0894-7317(88)80095-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerhof N., Lankhaar J. W., Westerhof B. E. (2009). The arterial Windkessel. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 47 131–141. 10.1007/s11517-008-0359-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J., Zhou X., Hu B., Gong S., Yu Y., Cai G., et al. (2017). Prognostic value of left ventricular-arterial coupling in elderly patients with septic shock. J. Crit. Care 42 289–293. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article are available to any qualified researcher from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.