Abstract

The melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) is involved in energy homeostasis and is an important drug target for syndromic obesity. We report the structure of the antagonist SHU9119-bound human MC4R at 2.8-angstrom resolution. Ca2+ is identified as a cofactor that is complexed with residues from both the receptor and peptide ligand. Extracellular Ca2+ increases the affinity and potency of the endogenous agonist α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone at the MC4R by 37- and 600-fold, respectively. The ability of the MC4R crystallized construct to couple to ion channel Kir7.1, while lacking cyclic adenosine monophosphate stimulation, highlights a heterotrimeric GTP-binding protein (G protein)-independent mechanism for this signaling modality. MC4R is revealed as a structurally divergent G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), with more similarity to lipidic GPCRs than to the homologous peptidic GPCRs.

The hemelanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) plays a central role in the control of energy homeostasis (1–3). As such, it is a prime therapeutic target for the treatment of syndromic and dietary obesity (4). MC4R is expressed in the hypothalamus, brainstem, and elsewhere in the nervous system, where it serves to coordinate food intake and energy expenditure (1, 5). For example, a wide variety of heterozygous loss-of-function mutations, including those reducing heterotrimeric stimulatory G protein (Gs) coupling such as I1022.62T and M2185.54T [superscripts denote Ballesteros-Weinstein numbers (6)] in the receptor cause a morbid early-onset obesity syndrome (7, 8), whereas gain-of-function mutations that increase receptor activity are associated with leanness (9). MC4R is something of a pharmacological enigma in that it exhibits a number of unusual properties, including (i) a gene dosage effect rarely seen with heterotrimeric GTP-binding protein (G protein)-coupled receptors (GPCRs) (2); (ii) regulation by both an endogenous agonist peptide [the tridecapeptide α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone (α-MSH)] and an endogenous antagonist or biased agonist called agouti-related protein (AgRP) (10, 11); (iii) regulation by the cognate modulator melanocortin-2 receptor (MC2R) accessory protein 2 (12); and (iv) the ability to couple to the ion channel Kir7.1 independently of G proteins (13). Perhaps for this reason, drug development has been particularly challenging. The receptor is the target of the peptide drug setmelanotide, a synthetic cyclic α-MSH ligand that has been successful in the treatment of rare cases of monogenic and syndromic obesity (14, 15) but not dietary obesity (16). More-potent small molecule and peptide MC4R agonists have failed clinical trials for common dietary obesity because of a target-mediated pressor response (17, 18), which setmelanotide appears to lack. Approaches to drug development that target MC4R will thus require insight into these unusual properties of the MC4R.

GPCRs can bind a wide variety of extracellular ligands including physiological cations (19–22). Biological and pharmacological studies have previously implicated both Zn2+ (23) and Ca2+ (24, 25) in the function of multiple members of the melanocortin receptor family. Whereas a structural and stabilization role for the Na+-binding site has been described in high-resolution class A GPCR structures (22), a structural and functional role of cation interactions with the transmembrane domains of GPCRs is poorly understood. Here, we report the structure of the human MC4R bound to the melanocortin antagonist SHU9119 at 2.75-Å resolution (Fig. 1, A to C; fig. S1; and table S1) and show that Ca2+ is a critical cofactor for binding and function of the endogenous agonist α-MSH.

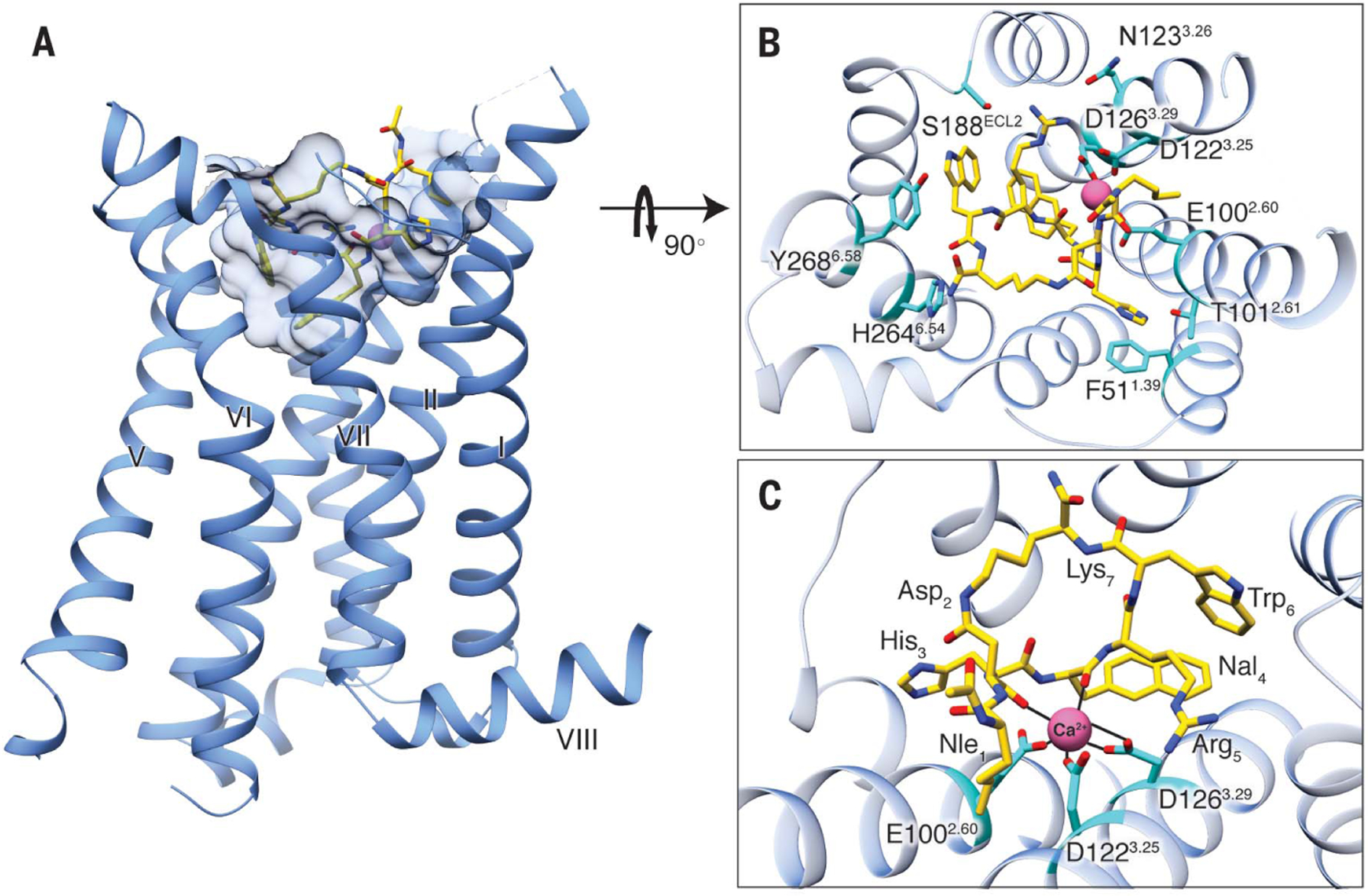

Fig. 1. Structure of SHU9119-bound MC4R.

(A) Side view of the crystal structure of the MC4R-SHU9119 complex. MC4R is shown in blue ribbons, SHU9119 in gold sticks. Shape of the binding pocket cut off at 4.7 Å is shown by light-blue semitransparent surface model. (B) Structure viewed from the extracellular side shows the interaction network between MC4R, SHU9119, and the metal ion. The interaction residues on MC4R are shown in cyan. (C) Expanded view of the metal ion-binding site. The interactions between the metal ion, MC4R, and SHU9119 are represented by solid black lines.

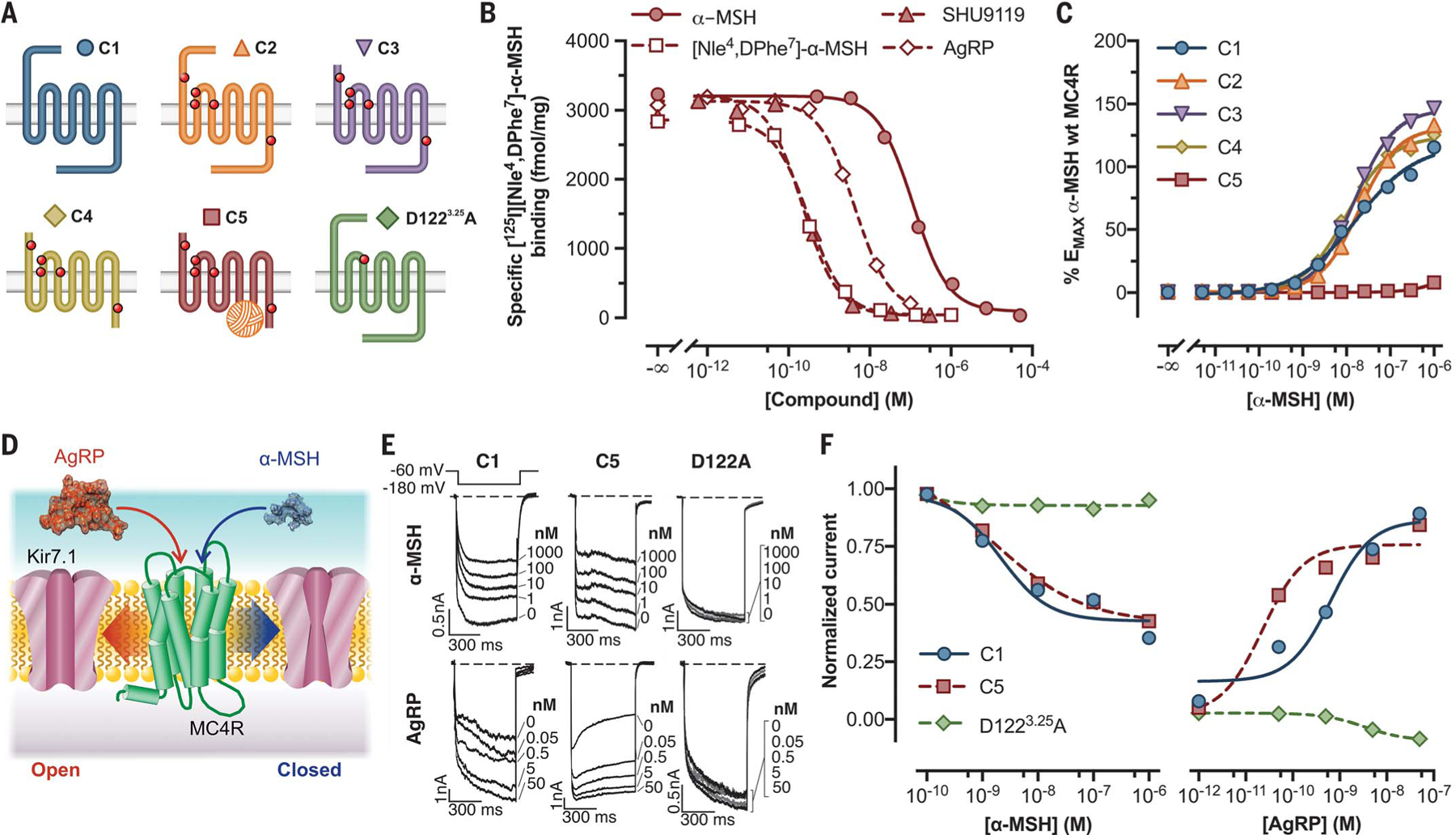

The final stabilized MC4R construct for crystallization was engineered by first introducing the following mutations into the MC4R wild-type sequence (Fig. 2A, C1 construct): E491.37V, N972.57L, S992.59F (26, 27), S1313.34A, and D2987.49N (Fig. 2A, C2 construct). To further stabilize the receptor, we truncated N-terminal residues 1 to 15 (Fig. 2A, C3 construct) and C-terminal residues 321 to 332 (Fig. 2A, C4 construct). Last, the sequence of a portion (residues 218 to 413) of Pyrococcus abyssi glycogen synthase (PGS) was inserted into the receptor’s third intracellular loop (ICL3) from residues H222 to R236 (Fig. 2A, C5 construct). As a result, a melting temperature of 75°C was achieved.

Fig. 2. Pharmacological characterization of MC4R constructs with thermostabilizing mutations, N- and C-terminal deletions, and PGS fusion.

(A) Modifications introduced to the human MC4R sequence and color key used in the other panels. (B) Competition binding of indicated compounds against 80 pM 125I-NDP-MSH to C5. (C) Live-cell α-MSH concentration-response curves for cAMP production in cells transfected with constructs C1 to C5. EMAX, Maximum effect; wt, wild-type. (D) Diagram depicting G protein-independent Kir7.1 modulation by MC4R in the presence of α-MSH or AgRP. (E) Representative inwardly rectifying Kir7.1 currents elicited by hyperpolarizing the membrane to −180 mV from a holding voltage of −60 mV from cells coexpressing the channel and indicated constructs (tagged wild-type receptor construct C1 and engineered crystallized receptor construct C5). (F) Concentration-response curves for α-MSH and AgRP in HEK293 cells cotransfected as labeled. In (B) and (C), data points represent the mean ± standard error from a representative experiment with six to 12 replicates. Data from (E) and (F) correspond to an ensemble of three to seven different patched cells per compound concentration. All data behind (B), (C), (E), and (F) are provided in data file S1.

The MC4R-SHU9119 complex shows a classical seven-transmembrane helical bundle with a small orthosteric binding pocket containing SHU9119 and a metal ion with strong electron density, suggesting the presence of a divalent cation (Fig. 1A and fig. S2, A and B). The metal ion is coordinated by two main-chain carbonyl oxygen atoms in SHU9119 (located at Asp2 and Nal4; position numbers for SHU9119 residues are labeled as subscripts) and three negatively charged residues in the MC4R (E1002.60, D1223.25, and D1263.29). Direct ligand interactions with the receptor include one salt bridge (Arg5 to D1263.29), multiple hydrogen bonds (His3 to T1012.61; Nal4 main-chain amide nitrogen atom to E1002.60; Arg5 to N1233.26 and S188ECL2; Trp6 to S188ECL2 main-chain carbonyl oxygen atom; and Trp6 main-chain carbonyl oxygen atom to H2646.54), and two π-π interactions (His3 to F511.39 and Trp6 to Y2686.58) (Fig. 1, B and C, and fig. S2, A to C). The hydrophobic interactions of SHU9119 with MC4R are very expansive, because all the transmembrane helices plus the N terminus and extracellular loop 2 (ECL2) regions are involved (Fig. 1B and fig. S2C).

In vitro mutagenesis studies previously suggested a role for some of these residues in ligand binding (E1002.60, D1223.25, D1263.29 and H2646.54, and Y2686.58) (28, 29). A classification system was previously proposed (30) to sort obesity-associated MC4R mutations into functional classes characterized by loss of expression (class I), disrupted trafficking to the plasma membrane (class II), decreased binding affinity (class III), defective coupling to Gαs (class IV mutants), and obesity-associated mutations with no apparent defect (class V). As expected, some class III and IV mutants, defective in ligand binding and receptor activation, respectively, map to the ligand-binding pocket and helix VII-switch region (Fig. 3A). By contrast, class II mutants primarily defective in cellular trafficking appear to localize to a previously uncharacterized receptor domain (Fig. 3B). Class V mutants, which are associated with syndromic obesity yet exhibit normal ligand binding and Gαs coupling, are largely excluded from the ligand-binding pocket and helix VII switch, as would be expected (Fig. 3C), and may also be highlighting a previously uncharacterized receptor domain. It was also reported that L1333.36 plays a role in defining the antagonist nature of SHU9119 (31) on MC4R, and we see an apparent interaction between this residue and the unnatural amino acid Nal4 in SHU9119.

Fig. 3. Distribution of functionally characterized mutations associated with syndromic obesity on the MC4R structure.

(A) Location of class III and IV mutations, functionally characterized as defective in ligand binding, or Gαs coupling, respectively. (B) Location of class II mutations, functionally characterized as primarily defective in trafficking. (C) Location of class V mutations, associated with syndromic obesity, but with normal ligand binding and Gαs coupling. Mutants shown here represent the subset of mutants for which we found validating functional data in the primary literature. The complete list of obesity-associated MC4R mutations and associated references from which the mutations here were derived may be found at www.mc4r.org.uk. Recently reported mutations impacting β-arrestin recruitment (9) were not included, because mutations impacting trafficking and coupling to Gαs also generally decrease β-arrestin recruitment. The models are shown as side views or as projections viewed from the extracellular side. Helices I and V are labeled as indicated for each model.

Notably, MC4R is structurally distinct from any reported GPCR. We compared MC4R with structures of all class A GPCRs in the inactive state by calculating the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of Cα atoms in the transmembrane regions. The smallest RMSD of any GPCR (excluding MC4R) to a receptor outside its subfamily is lower than 2.0 Å, whereas for MC4R, the lowest value still exceeds 2.2 Å when compared with the closest lysophosphatidic acid receptor 1 (table S2). The structural divergence between MC4R and other reported GPCR structures results primarily from its distinctive structural features, such as the very short ECL2, a missing conserved disulfide bond that usually connects ECL2 to helix III in other class A GPCRs (32), a distinctly outward position of helix V compared with those of other GPCRs, and the presence of nonconserved residues, including G2.58, D3.25, and H5.50.

We completed a thorough pharmacological characterization of the stepwise receptor modifications (Fig. 2A, receptor forms C2 through C5) that were required to produce a crystallizable form of MC4R, as compared with the wild-type receptor (C1). All mutated constructs (C2 through C5) appear to have a favored cell-surface expression over the wild-type form, with the thermostabilizing point mutations (C2) and the deletion of the amino terminus (C3) eliciting the highest expression levels, as assessed by means of experiments with surface enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (fig. S3A). The deletion of 12 C-terminal amino acids (C4) and the addition of a PGS sequence in ICL3 (C5) both showed decreased expression when compared with constructs C2 and C3 (fig. S3A). Saturation-binding studies of [125I][Nle4,DPhe7]-α-MSH (125I-NDP-MSH) (fig. S3B), a high-affinity synthetic ligand related to α-MSH, demonstrate that the crystallized form of the receptor (C5), in line with the cell-surface ELISA experiments, has a total expression level 10 times higher than that of the wild type (C1) and binds the ligand with a dissociation constant (Kd) (377 pM) similar to that of the untagged wild-type receptor (235 pM) (table S3). Competition-binding studies performed using 125I-NDP-MSH at a concentration near the Kd value for this ligand demonstrate that α-MSH, AgRP, SHU9119, and [Nle4,DPhe7]-α-MSH (NDP-MSH) bind C5 (Fig. 2B and table S4) with a rank order of affinity similar to that seen at the wild-type receptor (data not shown). Last, using a cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-based assay to examine coupling of C1 through C5 to Gαs, we determined that the potency for the native agonist α-MSH and the synthetic and native antagonists SHU9119 and AgRP are nearly identical at receptors C1 to C4 (Fig. 2C; fig. S3, C and D; and table S5). As expected, the introduction of the PGS fragment into ICL3 completely blocked coupling to Gαs (Fig. 2C; fig. S3, C and D; and table S5).

A recent study found that regulation of the firing activity of MC4R-expressing neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus could be mediated by ligand-induced coupling of the MC4R to close (by means of α-MSH) or open (by means of AgRP) the inward rectifying potassium channel Kir7.1 (Fig. 2D) (13). These pharmacological data suggested that neither event required G proteins. Whereas receptor construct C5 did not couple to Gαs, whole cell-patch voltage-clamp studies using human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells cotransfected with both Kir7.1 and either C1 or C5 forms of MC4R showed that the crystallized receptor form (C5) exhibits α-MSH- and AgRP-regulated coupling to Kir7.1 channels with concentration-response curves comparable (α-MSH) or even left-shifted (AgRP) relative to the wild-type (C1) receptor (Fig. 2, E and F; and table S6). We next compared concentration-response curves of Kir7.1 current inhibition and activation by α-MSH and AgRP (Fig. 2, E and F) for cells cotransfected with an MC4R mutant (D1223.25A), previously shown to lack high-affinity ligand binding, as a result of what we have shown (Fig. 1C) to be a critical electrostatic interaction for ligand binding (28). We confirmed the defective cAMP stimulation (fig. S3E) and found that this mutation completely abolished coupling of MC4R to the Kir7.1 channel (Fig. 2, E and F; and table S6), demonstrating the ligand dependence of this interaction.

The most notable feature of the MC4R-SHU9119 structure is the metal ion bound to both MC4R and SHU9119 (Fig. 1, B and C; and fig. S2). This is consistent with the necessary crystallization conditions requiring 50 to 100 mM CaCl2. To investigate the structural data suggesting the presence of Ca2+, a series of thermal stability assays were set up to analyze the effects of different divalent cations on MC4R stability. We measured the thermal stability of the MC4R in complex with different MC4R ligands such as SHU9119, NDP-MSH, α-MSH, and AgRP, in response to Ca2+, Mg2+, and Zn2+. Only Ca2+ increased the thermal stability of MC4R-SHU9119 or MC4R-NDP-MSH, and the temperature decreased to the same value as the vehicle when the receptor sample was further incubated with EDTA (Fig. 4, A and B). We also performed inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy with an aliquot of the same protein preparation (5.25 mg/ml) used for crystallization. The reported concentrations for Zn2+ and Mg2+ in this experiment were 0.21 mg/liter and <0.01 mg/liter to trace amounts, respectively, as opposed to 1.26 mg/liter for calcium, which is 100-fold higher than the concentration of Mg2+. Further confirmation came from radioligand-binding experiments conducted to evaluate the effects of monovalent and divalent cations on the binding of 125I-NDP-MSH to the MC4R (Fig. 4C and table S7). In concert with the structural data and effects on thermostability, Ca2+ was most effective at increasing ligand binding to the MC4R, with a median effective concentration (EC50) of 3.7 μM (table S7). Using a competition-binding assay on wild-type receptor, we next examined the effect of 10 μM Ca2+ on the affinity of native and synthetic ligands. Ca2+ only marginally lowered the inhibition constant (Ki) values of SHU9119, AgRP, and NDP-MSH. By contrast, Ca2+ caused a 37-fold increase in the binding affinity of the native agonist α-MSH, lowering the Ki value from 64 to 1.7 nM (Fig. 4D and table S8). Similar results were seen when α-MSH competition-binding experiments were performed using receptor constructs C1 and C5 with Ki fold shifts of ~28 and ~99, respectively, confirming that despite the introduction of thermostabilizing mutations, N- and C-terminal truncations, and insertion of the PGS sequence, the C5 crystallization construction retains an enhanced shift toward a high-affinity state for the endogenous agonist (fig. S4 and table S9) in the presence of Ca2+.

Fig. 4. Ca2+ affects receptor stability and modulates the binding and activation of MC4R coupling by α-MSH.

(A) Thiol-N-[4-(7-diethylamino-4-methyl-3-coumarinyl)phenyl] maleimide (CPM) dye-based thermostability assays of SHU9119, NDP-MSH, α-MSH, or AgRP(83–132) were performed in the presence of the indicated salts at a concentration of 100 μM. (B) CPM dye-based thermostability assays of SHU9119 or NDP-MSH were performed in the presence of 100 μM CaCl2 and/or 200 μM EDTA. a.u., arbitrary units. (C) Effect of different metal ions on the binding of 80 pM 125I-NDP-MSH to wild-type MC4R stably expressed in HEK293 cells. (D) Competition binding of SHU9119, NDP-MSH, the endogenous ligand α-MSH, or the endogenous antagonist AgRP(83–132) against 80 pM 125I-NDP-MSH in the presence or absence of 10 μM CaCl2 [using the same source of MC4R as in (C)]. max., maximum. (E and F) Effect of 0.5 mM CaCl2 on the concentration-response curves of α-MSH using MC4R-C1 transfected cells (E) or forskolin using untransfected HEK293 cells (F). (G) Effect of 0.5 mM CaCl2 on α-MSH-induced Kir7.1 channel closure. Data points on (C) through (G) represent the mean ± standard error for four [(E) and (F)] to six replicates [(C) and (D)] from two independent experiments for each condition. In (G), each data point represents the aggregate of 10 to 15 individually patched cells for each agonist concentration. All data behind (C) through (G) are provided in data file S1.

Perhaps of more importance is that the increased affinity of α-MSH for MC4R in the presence of Ca2+ translates into an exceedingly increased agonist potency for adenylyl cyclase stimulation and cAMP production. We found that the cAMP-level response profile for α-MSH was shifted to the left by ~600-fold, a very large effect for a sub-millimolar concentration of Ca2+ (Fig. 4E and table S10). Non-receptor-mediated activation of adenylyl cyclase with forskolin shows no Ca2+ dependence (Fig. 4F and table S10), confirming the specific role for Ca2+ in α-MSH-mediated MC4R stimulation. Furthermore, the importance of Ca2+ in MC4R function was not limited to Gαs-elicited signaling, as we observed a left fold shift of 7.25 for the endogenous agonist in Kir7.1-MC4R-coupling dose-response experiments (Fig. 4G and table S10).

These data may help explain the unusual biological observations on the importance of extracellular Ca2+ for signaling of melanocortin receptors MC1R and MC2R in cells and tissues (24, 25, 33). For example, early studies demonstrated that among multiple hormones that regulate the Gαs-mediated activation of adenylyl cyclase in adipocytes, only adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) was dependent on Ca2+ (24), suggesting that Ca2+ may be a cofactor for ACTH binding to MC2R. Similarly, a study on the MC1R in melanocytes showed that the prolonged induction of pigmentation by NDP-MSH was Ca2+ dependent (34).

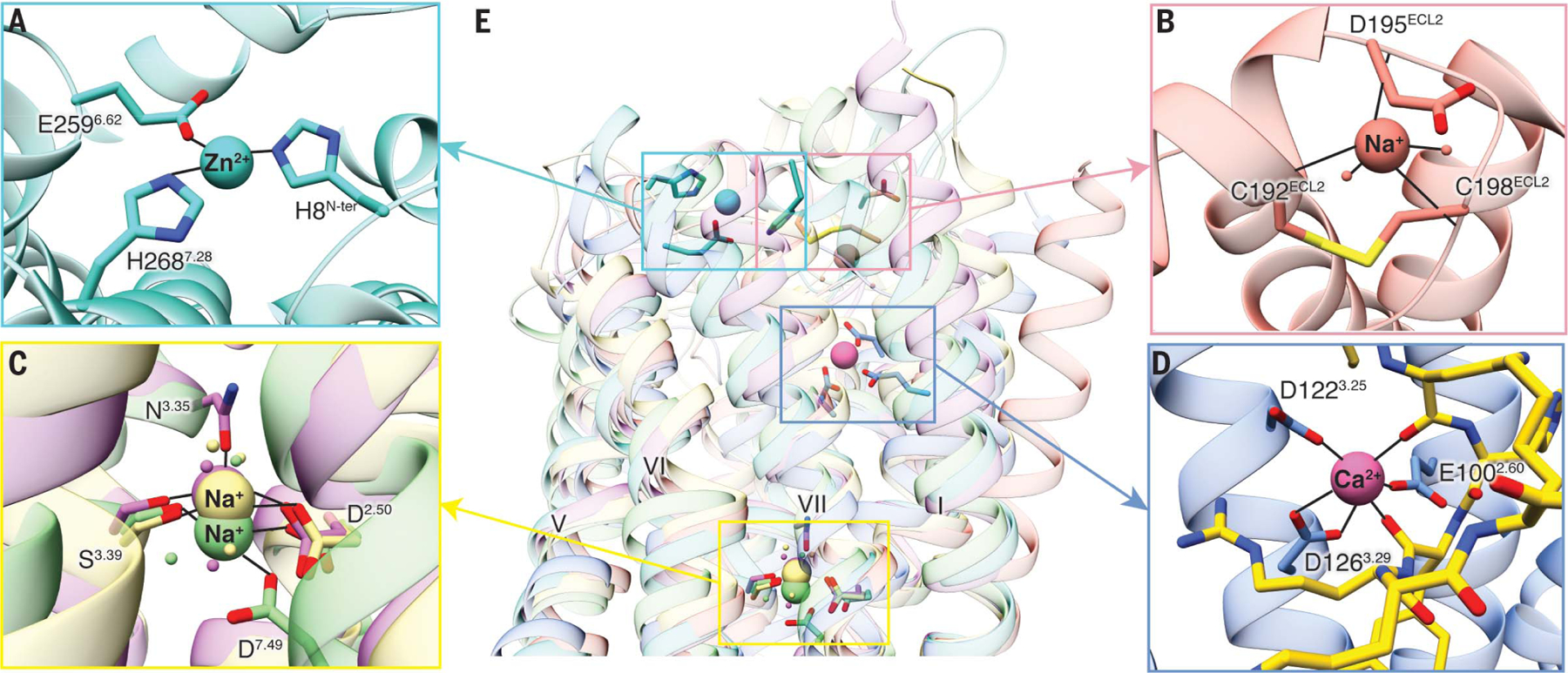

Modulation of GPCR function by physiologic cations, such as the regulation of the MC1R and MC4R by Zn2+ (23), has attracted some recent attention. Although Zn2+ is proposed to act as a positive allosteric modulator and weak partial agonist at the MC4R, no binding was noted in our biochemical studies. However, a binding site for Zn2+ coordinated by two histidine residues and one glutamic acid was recently revealed in the platelet-activating-factor receptor (PAFR) (Fig. 5A) (35). A role of Na+ in the negative allosteric modulation of class A GPCRs was demonstrated at a structural and functional level when the high-resolution crystal structure of the A2A adenosine receptor (A2AAR) was solved (22). As the development of technology on membrane protein crystallography has advanced, more high-resolution structures have reported the conserved Na+-binding site (21, 36), which is mostly formed by D2.50, N3.35, S3.39, N7.45, and N/D7.49 (Fig. 5C). Studies on the β1-adrenoceptor (β1AR) reported a previously unknown Na+-binding site located on an extracellular site coordinated by one aspartic acid, two cysteine residues, and two water molecules (Fig. 5B) (37). As shown in the superimposed comparison of known cation-binding sites (Fig. 5E), Ca2+ acts as a cofactor for ligand binding to the MC4R, occupying a different site that overlaps the MC4R orthosteric binding pocket and interacts with both the peptide ligand SHU9119 and MC4R (Fig. 5D). Our findings provide evidence supporting a different function for extracellular cations on GPCR regulation, where aside from allosteric modulators, they act as cofactors for ligand binding at the orthosteric site. Furthermore, Ca2+ acts in a biased fashion, regulating the affinity for the endogenous agonist α-MSH but not the endogenous inverse agonist AgRP.

Fig. 5. Ca2+-binding site of MC4R and comparison with other known GPCR cation-binding sites.

(A) Zn2+ ion-binding site is located at the extracellular side of PAFR (PDB ID 5ZKQ, turquoise). Residues are shown in turquoise. (B) Extracellular binding site of Na+ on β1AR (PDB ID 4BVN, salmon) is located at the extracellular loops. (C) Conserved Na+-binding site in most class A GPCRs including D2.50 and S3.39 (A2AAR, PDB ID 4EIY, khaki). Both proteinase-activated receptor 1 (PAR1, PDB ID 3VW7, light green) and d-type opioid receptor (DOR, PDB ID 4N6H, orchid) have an additional interaction residue, D7.49 and N3.35, respectively. (D) Binding site for Ca2+ in the MC4R is surrounded by residues from helices II and III and by carbonyl oxygens from the ligand, near the extracellular face. Ca2+ is shown as a pink sphere. The peptide ligand is represented as gold sticks. (E) Superposition of MC4R, PAFR, β1AR, A2AAR, PAR1, and DOR shows the comparison of known cation-binding sites. All coordinate bonds are shown in solid black lines.

MC4R has drawn much attention not only because it is the most common target of mutations causing monogenic obesity but also because it remains an important drug target for other forms of obesity as well (14, 15). The features of the MC4R structure that are critical for ligand binding have evolved to allow regulation by two unrelated endogenous ligands: the linear tridecapeptide agonist α-MSH, which activates MC4R and leads to reduced appetite, and the 50-amino acid cystine-knot antagonist or biased agonist AgRP, which leads to increased food intake. We hypothesize that Ca2+ stabilizes the ligand-binding pocket and functions as an endogenous cofactor for the binding of α-MSH to MC4R. With an EC50 of ~4 μM (table S7), Ca2+ is likely to bind when the receptor is exposed to extracellular Ca2+ concentrations (~1.2 mM in the extracellular space of the central nervous system) but might not be bound intracellularly (Ca2+ concentration: 100 nM), thus suggesting a potential regulatory role for Ca2+ in α-MSH-binding dynamics. It is interesting to speculate that signaling along the phospholipase C pathway can significantly raise the intracellular Ca2+ concentration, and this may constitute positive feedback from signaling of MC4R or other receptors that result in Ca2+ flux. Our discovery highlights the plasticity and multipronged regulation and control of this receptor and will aid in next-generation structure-based drug design of therapeutics for MC4R-related obesity.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The synchrotron radiation experiments were performed at the BL41XU and BL45XU of SPring-8 with approval of the Japan Synchrotron Radiation Research Institute (JASRI) (proposal numbers 2019A2520, 2019A2522, 2019A2523, 2019A2524). We thank Z.-J. Liu, T. Hua, L. Shen, and all staff from BL41XU and BL45XU for their help with data collection. We thank the Cloning, Cell Expression, Assay, and Protein Purification Core Facilities of the iHuman Institute for their support. We thank A. Walker for assistance with the manuscript, and we also thank J. Smith, J. Stuckey, and T. Claff for critical insights or reading of the manuscript. We thank P. Popov and V. Katritch for designing the thermostabilizing mutations. R.C.S. acknowledges that USC is his primary affiliation.

Funding: We thank the Shanghai Municipal Government, ShanghaiTech University, and the GPCR Consortium for financial support. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grants R01DK070332 (to R.D.C.) and R01DK110403 (to G.L.M.)]. B.S. was funded by an EMBO long-term postdoctoral fellowship (ALTF 677-2014).

Footnotes

Competing interests: R.C.S. is the founder of a GPCR structure-based drug discovery company called ShouTi. R.D.C. is a founder of a melanocortin receptor drug discovery company called Courage Therapeutics.

Data and materials availability: Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with identification code 6W25. Other data are available in the manuscript or supplementary materials.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Fan W, Boston BA, Kesterson RA, Hruby VJ, Cone RD, Nature 385, 165–168 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huszar D et al. , Cell 88, 131–141 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson EJ et al. , J. Mol. Endocrinol 56, T157–T174 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ericson MD et al. , Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis 1863 (10 Pt A), 2414–2435 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mountjoy KG, Mortrud MT, Low MJ, Simerly RB, Cone RD, Mol. Endocrinol 8, 1298–1308 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ballesteros JA, Weinstein H, in Receptor Molecular Biology, Sealfon SC, Ed. (Academic Press, 1995), vol. 25, pp. 366–428. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lubrano-Berthelier C et al. , J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 91, 1811–1818 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rong R et al. , Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf.) 65, 198–205 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lotta LA et al. , Cell 177, 597–607.e9 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ollmann MM et al. , Science 278, 135–138 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Büch TR, Heling D, Damm E, Gudermann T, Breit A, J. Biol. Chem 284, 26411–26420 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asai M et al. , Science 341, 275–278 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghamari-Langroudi M et al. , Nature 520, 94–98 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kühnen P et al. , N. Engl. J. Med 375, 240–246 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clément K et al. , Nat. Med 24, 551–555 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen KY et al. , J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 100, 1639–1645 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenfield JR et al. , N. Engl. J. Med 360, 44–52 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krishna R et al. , Clin. Pharmacol. Ther 86, 659–666 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zarzycka B, Zaidi SA, Roth BL, Katritch V, Pharmacol. Rev 71, 571–595 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White AD et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 116, 3294–3299 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang C et al. , Nature 492, 387–392 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu W et al. , Science 337, 232–236 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holst B, Elling CE, Schwartz TW, J. Biol. Chem 277, 47662–47670 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Birnbaumer L, Rodbell M, J. Biol. Chem 244, 3477–3482 (1969). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salomon Y, Mol. Cell. Endocrinol 70, 139–145 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Popov P et al. , eLife 7, e34729 (2018).29927385 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stauch B et al. , Nature 569, 284–288 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang YK et al. , Biochemistry 39, 14900–14911 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang Y, Harmon CM, Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis 1863 (10 Pt A), 2436–2447 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tao YX, Mol. Cell. Endocrinol 239, 1–14 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang Y et al. , J. Biol. Chem 277, 20328–20335 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Venkatakrishnan AJ et al. , Nature 494, 185–194 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kopanchuk S et al. , Eur. J. Pharmacol 512, 85–95 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hadley ME, Anderson B, Heward CB, Sawyer TK, Hruby VJ, Science 213, 1025–1027 (1981). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cao C et al. , Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 25, 488–495 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fenalti G et al. , Nature 506, 191–196 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller-Gallacher JL et al. , PLOS ONE 9, e92727 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.