Abstract

Background:

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals can interfere with hormonal homeostasis and have adverse effects for both humans and the environment. Their identification is increasingly difficult due to lack of adequate toxicological tests. This difficulty is particularly problematic for cosmetic ingredients, because in vivo testing is now banned completely in the European Union.

Objectives:

The aim was to identify candidate preservatives as endocrine disruptors by in silico methods and to confirm endocrine receptors’ activities through nuclear receptors in vitro.

Methods:

We screened preservatives listed in Annex V in the European Union Regulation on cosmetic products to predict their binding to nuclear receptors using the Endocrine Disruptome and VirtualToxLab™ version 5.8 in silico tools. Five candidate preservatives were further evaluated for androgen receptor (AR), estrogen receptor (), glucocorticoid receptor (GR), and thyroid receptor (TR) agonist and antagonist activities in cell-based luciferase reporter assays in vitro in AR-EcoScreen, , MDA-kb2, and GH3.TRE-Luc cell lines. Additionally, assays to test for false positives were used (nonspecific luciferase gene induction and luciferase inhibition).

Results:

Triclocarban had agonist activity on AR and at and antagonist activity on GR at and TR at . Triclosan showed antagonist effects on AR, , GR at and TR at , and bromochlorophene at (AR and TR) and at ( and GR). AR antagonist activity of chlorophene was observed [inhibitory concentration at 50% (IC50) ], as for its substantial agonist at and TR antagonist activity at . Climbazole showed AR antagonist (), agonist at , and TR antagonist activity at .

Discussion:

These data support the concerns of regulatory authorities about the endocrine-disrupting potential of preservatives. These data also define the need to further determine their effects on the endocrine system and the need to reassess the risks they pose to human health and the environment. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP6596

Introduction

Preservatives are substances that are incorporated into personal care products to improve their stability. However, the long-term health effects of daily use of preservatives were often unknown, even though they continue to be incorporated in consumer formulations (Halden et al. 2017). Indeed, after years on the market, some preservatives have been shown to be contact allergens (Goossens 2016), to have roles in antibiotic resistance (Aiello and Larson 2003), and to interfere with the endocrine system (SCCS 2018a). In past years, more emphasis was put on their adverse effects and especially their potential endocrine-disrupting activities (SCCS 2018a). Epidemiological studies showed an association between use of hair products with earlier age of menarche (James-Todd et al. 2011) and risk of uterine leiomyomata (Wise et al. 2012). Certain types of paraben preservatives were banned or restricted for use in cosmetic products where potential risk for human health was present due to their potential endocrine activity (European Commission 2014).

Identification, characterization, and risk assessment of preservatives is a challenging task. With the ban on animal testing for cosmetic ingredients in the European Union (European Parliament and Council of the European Union 2009) and a lack of adequate alternative nonanimal in vitro tests, it is very difficult to predict the potential endocrine-disrupting effects of these compounds. The World Health Organization defines an endocrine-disrupting chemical (EDC) as “an exogenous substance or mixture that alters function(s) of the endocrine system and consequently causes adverse effects in an intact organism, or its progeny, or (sub)populations” (World Health Organization 2013). However, for preservatives used solely in cosmetics, it is prohibited to conduct in vivo studies under the Cosmetic Regulation, and consequently, sufficient evidence cannot be provided to classify a preservative as an EDC. Thus, to assess the risk of endocrine disruption, regulatory authorities must rely on lines of evidence level-1 (existing data and nontest information) and lines of evidence level-2 [in vitro assays providing data about selected endocrine mechanism(s)/pathway(s) (mammalian and nonmammalian methods)] (SCCS 2018a). The caveat with lines of evidence level-1 is that in vivo tests conducted before the animal testing ban did not include end points on endocrine disruption, other than reproductive toxicity (SCCS 2006), and the crucial limitation of lines of evidence level-2 is the lack of in vitro tests that would cover all mechanisms by which EDCs can exert their effects. EDCs can disrupt the endocrine system at the level of hormone transport, synthesis, metabolism, secretion, or action (Gore et al. 2015). The most studied mechanism of action of EDCs is mimicking or antagonizing endogenous hormone effects by binding to nuclear receptors, and thereby causing changes in expression of hormone-responsive genes. However, EDCs can also affect hormonal homeostasis at the transcriptional level through epigenetic mechanisms (Shahidehnia 2016). In addition, they can have effects via nontranscriptional mechanisms by binding to nonnuclear steroid and nonsteroid receptors [e.g., membrane estrogen receptor (ER) and neurotransmitter receptors] (Diamanti-Kandarakis et al. 2009). Although many hormone systems and mechanisms of action of EDCs are not included, currently available in vitro methods to provide data on endocrine disruption for cosmetic ingredients are: estrogen or androgen receptor binding affinities; estrogen receptor transactivation; yeast estrogen screening; androgen receptor transcriptional activation; steroidogenesis in vitro; aromatase assays and thyroid disruption assays (e.g., thyroperoxidase inhibition, transthyretin binding); retinoid receptor transactivation assays; other hormone receptors assays as appropriate; and high-throughput screening (SCCS 2018a).

The use of preservatives nowadays also goes beyond cosmetic ingredients (e.g., in the textile, health care, plastics, and cleaning products industries), which results in greater exposure for humans and the biota. The Swedish Chemicals Agency (KEMI) has issued a warning about the consequences that might arise if preservatives with endocrine-disrupting properties enter the environment (KEMI 2017). KEMI has called for evaluation of seven common preservatives for their possible endocrine-disrupting effects. These preservatives include triclocarban, triclosan, bromochlorophene, chlorophene, and climbazole. Furthermore, the European Commission issued an open call in 2019 for any scientific information relevant to safety assessments of selected ingredients in cosmetic products that potentially have endocrine-disrupting properties, such as triclocarban and triclosan (European Commission 2019). The amount of toxicological data on different preservatives varies, though the lack of data on endocrine disruption is common to all.

Here, the aim was to screen some of the preservatives allowed in cosmetic products for their potential interference with nuclear receptors in silico. Furthermore, the top five preservatives identified by in silico methods (preservatives with three or more predicted interactions with nuclear receptors of moderate or high binding probabilities with Endocrine Disruptome [ED; (Kolšek et al. 2014b)] or binding at less than with VirtualToxLab™ [VTL; (Vedani et al. 2009, 2012, 2015; Vedani and Smiesko 2009)] were then assessed in terms of their endocrine-disrupting potential in vitro in the following reporter cell-line systems: AR-EcoScreen cells [Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) validated]; cells (OECD validated); MDA-kb2 cells; and GH3.TRE-Luc cells. These systems are designed to define androgen (AR), estrogen (ER), glucocorticoid (GR) and thyroid (TR) receptor agonists and antagonists.

Methods

Computational Methods

In silico evaluation of interactions of 56 preservatives with nuclear receptors was carried out to predict their endocrine-disrupting potential, using two platforms: Endocrine Disruptome (ED) (Kolšek et al. 2014b) and VirtualToxLab™, version 5.8 (VTL) (Vedani et al. 2009, 2012, 2015; Vedani and Smiesko 2009). The 56 screened preservatives are listed in Annex V of the “List of preservatives allowed in cosmetic products,” of Regulation (EC) No. 1223/2009 on cosmetic products (European Parliament and Council of the European Union 2009) as well as in Tables S1–S3.

The ED docking program (Kolšek et al. 2014b) was used to determine the binding affinities to nuclear receptors of the preservatives (for molecular weight ). The program uses Docking Interface for Target Systems (DoTS) for docking simulation, and AutoDock Vina for docking calculation (Kolšek et al. 2014b). The evaluation included 12 types of nuclear receptors: AR, , , GR, liver X receptor , , peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor , , , retinoid X receptor , , and , some of which are available as both agonist and antagonist conformations (AR, , , GR). The data obtained were color coded. The threshold values depended on the binding affinity of the ligands as follows: red () for high binding probability of the ligand; orange () for moderate binding probability; yellow () for low binding probability; and green () for very low binding probability (Kolšek et al. 2014b). Corresponding binding free energy thresholds for each receptor in ED were determined by ED validation by Kolšek et al. (2014b) and are provided in Table S4. ED is freely accessible at http://endocrinedisruptome.ki.si/ (Kolšek et al. 2014b).

In addition to ED, VTL (Vedani et al. 2009, 2012, 2015; Vedani and Smiesko 2009) was used to describe interactions of the preservatives with 10 nuclear receptors: AR, , , GR, LXR, mineralocorticoid receptor (MR), , progesterone receptor (PR), , and . The evaluation of the binding affinity in VTL was carried out by automated, flexible docking with Yeti/AutoDock (Spreafico et al. 2009; Vedani et al. 2005), which assesses all orientations and conformations of small molecules in the binding site. This was combined with multidimensional quantitative structure–activity relationships using the multidimensional QSAR (mQSAR) software [Quasar (Vedani et al. 2005, 2006, 2007b, 2007a; Vedani and Dobler 2002)], which considers orientation, conformation, position, protonation, tautomeric state, solvation, and induced fit of the small molecules. The data are provided as concentrations at which the compounds are predicted to interact with a nuclear receptor.

Chemicals

Preservatives triclocarban (CAS 101-20-2), triclosan (CAS 3380-34-5), bromochlorophene (CAS 15435-29-7), chlorophene (CAS 120-32-1) and climbazole (CAS 38083-17-9) were of 95% or higher purities, as specified by the manufacturer (Tokyo Chemical Industry). Control compounds (DHT; CAS 521-18-6), flutamide (FLU; CAS 13311-84-7), hydroxyflutamide (CAS 52806-53-8), (E2; CAS 50-28-2), (CAS 57-91-0), tamoxifen (CAS 10540-29-1), hydroxytamoxifen (CAS 68047-06-3), hydrocortisone (HC; CAS 50-23-7), mifepristone (CAS 84371-65-3; RU-486), dexamethasone (CAS 50-02-2), triiodothyronine (T3; CAS 6893-02-3), and bisphenol A (CAS 80-05-7) were of 97% or higher purities, as specified by the manufacturer (Sigma-Aldrich). Cell culture grade DMSO (CAS 67-68-5) was used as vehicle for chemical formulations for in vitro assays and was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All of the preservatives were first screened for agonist and antagonist activities in vitro at 0.1, 1.0, and (or lower, as “highest noncytotoxic,” if showed cytotoxicity). This was followed by dose-dependence assays over a broader range of concentrations if this initial screening showed endocrine-disrupting effects.

AR-EcoScreen Cell Line

The AR-EcoScreen cell line was used for identification of human (h)AR agonists and antagonists. As detailed in the OECD 458 guideline for the testing of chemicals, these cells provide a stably transfected hAR transcriptional activation assay for detection of androgenic agonist and antagonist activities of compounds (OECD 2016b). This cell line was derived from a Chinese hamster ovary cell line (CHO-K1) that was stably transfected with hAR, a firefly luciferase gene, and constitutively expressed renilla luciferase gene, to allow detection of cytotoxicity on this system. The AR-EcoScreen cell line was purchased from Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources (JCRB) Cell Bank (JCRB1328) and maintained in phenol red–free Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM)/F-12, supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), Zeocin (Invivogen), hygromycin B, penicillin, and streptomycin (all from Sigma-Aldrich). The test medium was prepared with phenol red–free DMEM/F-12 (Gibco), supplemented with 5% dextran charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum (Gibco), penicillin, and streptomycin (both Sigma-Aldrich). The cells were grown at 37°C under 5% . For the assays, OECD guideline 458 was followed (OECD 2016b). The cell suspensions in test medium (; ) were seeded in 96-well plates and preincubated for 24 h before the treatments. The control and preservative stock solutions were serially diluted in test medium, and of each was added to each well, as triplicates. The cells underwent these treatments in the absence and presence of DHT for 24 h, and the cells were then lysed using Luciferase Cell Culture Lysis Reagent (Promega). Afterward, firefly luciferase reagent ONE-Glo (Promega) was added, and luciferase luminescence was recorded (2-s medium shaking step followed by luminescence end point measurement; no light source or emission filters) using a microplate reader (Synergy 4 Hybrid Multi-Mode; BioTek). Cell viability assays were run in parallel as described by Freitas et al. (2011). Briefly, the cells were treated following the same protocols as the agonist and antagonist assays with the exception of the endpoint lysis and measurements. To determine the metabolic activities of the preservatives, resazurin was added to each well after the 24-h treatments. The cells were incubated in the dark at 37°C for 2–4 h. The cellular metabolic activity converted the resazurin to fluorescent resorufin, and its fluorescence was measured at and in a microplate reader (Synergy 4 Hybrid Multi-Mode; BioTek).

Cell Line

The cell line was used for identification of human (h) agonists and antagonists. It was developed by Japanese Chemicals Evaluation and Research Institute, and as detailed in the OECD 455 guideline for the testing of compounds, these cells provide a stably transfected in vitro transactivation assay to detect ER agonists and antagonists (OECD 2016a). This cell line was derived from a human cervical tumor that was stably transfected with and a firefly luciferase gene. The cell line was purchased from JCRB Cell Bank (JCRB1318) and maintained in Eagle’s minimum essential medium without phenol red (Gibco), supplemented with 10% dextran charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and kanamycin (Sigma-Aldrich), at 37°C under 5% . To determine agonist and antagonist activities, OECD guideline 455 was followed (OECD 2016a). Briefly, cells in were seeded in 96-well plates and preincubated for 3 h before the treatments. The control and preservative stock solutions were serially diluted in medium, and of each added to each well, as triplicates. For the antagonist setup, the dilution medium also had E2 added (final concentration, ). The cells were incubated for 24 h, followed by cell lysis, using Luciferase Cell Culture Lysis Reagent (Promega). Then, firefly luciferase reagent ONE-Glo (Promega) was added, and luciferase luminescence was recorded (2-s medium shaking step followed by luminescence end point measurement; no light source or emission filters) using a microplate reader (Synergy 4 Hybrid Multi-Mode; BioTek). Cell viability assays were run in parallel, as described above for the AR-EcoScreen cell line.

MDA-kb2 Cell Line

The MDA-kb2 cell line was used for the identification of GR agonists and antagonists. This cell line was developed by Wilson et al. (2002), and it was derived from a breast cancer MDA-MB-453 cell line that constitutively expressed high levels of functional GR and AR. The MDA-kb2 cell line was prepared by stable transfection of the MDA-MB-453 cell line with a murine mammalian tumor virus luciferase neo reporter gene construct, which expresses firefly luciferase on exposure to GR and AR agonists. To discriminate against AR-mediated increases in the luciferase production, these cells were concomitantly treated with an AR antagonist FLU in the GR agonist assays as described below. The MDA-kb2 cell line was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC CRL-2,713) and maintained in Leibovitz’s L-15 medium (Sigma-Aldrich), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), penicillin and streptomycin (both from Sigma-Aldrich). The test medium was prepared with the Leibovitz’s L-15 medium supplemented with 10% dextran-charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum (Gibco), penicillin and streptomycin (both from Sigma-Aldrich). The assays were carried out according to Wilson et al. (2002). Briefly, cells in were seeded in 96-well plates in test medium and preincubated for 24 h before the treatments. The control and preservative stock solutions were serially diluted in test medium. The medium from the wells was then removed. For the glucocorticoid agonist assays, the AR was blocked with androgen antagonist FLU with an incubation for 30 min; then was added to each well, as triplicates. Similarly for the glucocorticoid antagonist assay (but without FLU), was added to each well, as triplicates, and incubated for 30 min, and then HC in medium was added. The cells were incubated for 24 h, followed by cell lysis with Luciferase Cell Culture Lysis Reagent (Promega). Then, firefly luciferase reagent ONE-Glo (Promega) was added, and luciferase luminescence was recorded (2-s medium shaking step followed by luminescence end point measurement; no light source or emission filters) using a microplate reader (Synergy 4 Hybrid Multi-Mode; BioTek). Cell viability assays were run in parallel, as described above for the AR-EcoScreen cell line.

GH3.TRE-Luc Cell Line

Disruption of and function was tested in vitro on the GH3.TRE-Luc cell line. This cell line is used for identification of and agonists and antagonists and was developed by Freitas et al. (2011). The cell line was derived from the thyroid-responsive rat pituitary tumor GH3 cell line that constitutively expressed both isoforms of TR, and . GH3.TRE-Luc cells were prepared by stable transfection of the GH3 cell line with the pGL4CP-SV40-2xtaDR construct, which expresses firefly luciferase on exposure to TR agonists. The cells were maintained in growth medium of DMEM/F-12 (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), penicillin, and streptomycin (both from Sigma-Aldrich). The test medium was DMEM/F-12 (Gibco) supplemented with insulin, ethanolamine, sodium selenite, human apotransferine, and bovine serum albumin (all from Sigma-Aldrich). The assays were conducted as previously described by Freitas et al. (2011). The cells were seeded at 80% confluency in culture flasks in growth medium. After 24 h, the growth medium was removed, the cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (Sigma-Aldrich), and the test medium was added. After a further 24 h, cells in were seeded in 96-well plates and preincubated at 37°C for 3 h. The control and preservative stock solutions were serially diluted in test medium; then of each was added to the wells, in triplicates. For the antagonist setup, the dilution medium also had T3 added (final concentration, ). The cells were incubated for 24 h, followed by cell lysis using Luciferase Cell Culture Lysis Reagent (Promega). Then, firefly luciferase reagent ONE-Glo (Promega) was added, and luciferase luminescence was recorded (2-s medium shaking step followed by luminescence end point measurement; no light source or emission filters) using a microplate reader (Synergy 4 Hybrid Multi-Mode; BioTek). Cell viability assays were run in parallel, as described above for the AR-EcoScreen cell line.

Luciferase Inhibition Assays

For the luciferase inhibition assay, GH3.TRE-Luc cells in were seeded in 96-well plates and incubated for 24 h with T3, followed by cell lysis using Luciferase Cell Culture Lysis Reagent (Promega). Serial dilutions for each treatment were prepared in the cell lysate and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Then firefly luciferase reagent ONE-Glo (Promega) was added, and luciferase fluorescence was recorded (2-s medium shaking step followed by luminescence end point measurement; no light source or emission filters) using a microplate reader (Synergy 4 Hybrid Multi-Mode; BioTek).

Binding Assays

PolarScreen AR Competitor and PolarScreen GR Competitor assays (Green kit; Invitrogen) were used to measure the binding affinities of the compounds for the AR and GR, according to manufacturer instructions, respectively. The preservatives were tested at concentrations from down to (in dilutions steps of 1:10) in both assays, with down to (in dilutions steps of 1:10) dihydrotestosterone as control ligand for AR and down to (in dilutions steps of 1:10) dexamethasone as control ligand for GR. The fluorescence polarization was recorded using a microplate reader (Synergy 4 Hybrid Multi-Mode; BioTek).

Statistical Analysis

All cell-based assays were carried out in triplicate. All of the data are expressed as deviation (SD) of at least two (for the OECD-validated cell lines AR-EcoScreen, ) or three (for MDA-kb2, GH3.TRE-Luc cell lines) independent repeats. All of the data were first normalized to the metabolic activities, to allow for any cytotoxic or proliferative effects, followed by normalization to the vehicle control treatment (0.1% DMSO) for agonist assays, and the spike-in control (0.1% DMSO with a known agonist as described for each cell line) for antagonist assays, to obtain the relative transcriptional activities (RTAs). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s post hoc tests were used to compare each concentration of a preservative with its respective control [vehicle control (0.1% DMSO) for agonist assays, and spike-in control (0.1% DMSO with a known agonist as described for each cell line) for antagonist assays]. Additionally, for competitive ER agonism assays, one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc tests were used to compare means of pairs (each preservative with and without the strong antagonist). Here, were considered statistically significant. and inhibitory concentration at 50% (IC50) values were calculated where feasible. All of the statistical analyses and curve fitting were carried out using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software Inc).

Results

In Silico Analysis

Endocrine Disruptome and VTL were used to assess the nuclear receptor binding probabilities of the preservatives listed in Annex V of the “List of Preservatives Allowed in Cosmetic Products” of Regulation (EC) No. 1223/2009 of The European Parliament and of The Council of 30 November 2009 on cosmetic products [(European Parliament and Council of the European Union 2009); Table S1]. The data for the preservatives with predicted moderate and high binding probabilities to nuclear receptors with ED and for the preservatives with predicted binding concentration of less than to nuclear receptors with VTL are shown in Table 1. Predicted binding probability distributions across nuclear receptors with ED and VTL are shown in Figure S1A and Figure S1B, respectively.

Table 1.

In silico results for preservatives in Annex V of the “List of Preservatives Allowed in Cosmetic Products” of Regulation (EC) No. 1223/2009 (European Parliament and Council of the European Union 2009) with predicted moderate (class orange) and high (class red) binding probabilities with Endocrine Disruptome and with predicted binding at a concentration of less than in VirtualToxLab™.

| Preservative | Endocrine Disruptome high or moderate binding probability | VirtualToxLab™ binding prediction at |

|---|---|---|

| o-Phenylphenol | ARan, class orange (moderate binding probability) | — |

| Zinc pyrithione | ARan, class orange (moderate binding probability) | — |

| Hexetidine | — | GR, |

| 2-Bromo-2-nitropropane-1,3-diol | — | AR, |

| — | , | |

| Triclocarban | ARan, class orange (moderate binding probability) | GR, |

| , class orange (moderate binding probability) | — | |

| , class red (high binding probability) | — | |

| Triclosan | — | PR, |

| — | , | |

| — | , | |

| Imidazolidinyl urea | ARan, class orange (moderate binding probability) | — |

| Climbazole | ARan, class orange (moderate binding probability) | AR, |

| — | PR, | |

| Bromochlorophene | — | AR, |

| — | , | |

| — | , | |

| — | , | |

| Chlorophene | ARan, class orange (moderate binding probability) | AR, |

| — | , | |

| Hexamidine | ARan, class orange (moderate binding probability) | — |

Note: Endocrine Disruptome binding probability classes are as follows: class red for high binding probability; class orange for moderate binding probability; class yellow for low binding probability; class green for very low/no binding probability. Binding free energy threshold values for each receptor are further defined in Table S4. —, no prediction of moderate (class orange) or high (class red) binding probabilities with Endocrine Disruptome or predicted binding at a concentration of less than 1 microM in VirtualToxLab™; an, antagonist conformation; AR, androgen receptor; , estrogen receptor ; , estrogen receptor ; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; PR, progesterone receptor; , thyroid receptor ; , thyroid receptor .

Endocrine Disruptome predicted moderate binding as the antagonist conformation of AR for seven preservatives: o-phenylphenol, zinc pyrithione, triclocarban, imidazolidinyl urea, climbazole, chlorophene, and hexamidine. Triclocarban was the only preservative to show both a moderate probability of binding as the agonist conformation of and a high probability of binding as the antagonist conformation of . Results for all tested preservatives with ED are shown in Table S1.

In contrast to ED, VTL identified more preservatives that might disturb nuclear receptor signaling. The preservatives predicted to interact with the nuclear receptors at nanomolar concentrations were: 2-bromo-2-nitropropane-1,3-diol, climbazole, chlorophene, and bromochlorophene for AR (with bromochlorophene predicted to bind to AR at a concentration as low as ); bromochlorophene for ; 2-bromo-2-nitropropane-1,3-diol and chlorophene for ; hexetidine and triclocarban for GR; triclosan and climbazole for PR; and triclosan and bromochlorophene for both isoforms of TR. Results for all tested preservatives with VTL are shown in Table S2.

The preservatives with predicted very low or no binding with both in silico tools, ED and VTL, were formaldehyde, formic acid, and 7-ethylbicyclooxazolidine.

Fourteen items from Annex V of the “List of Preservatives Allowed in Cosmetic Products” of Regulation (EC) No. 1223/2009 (European Parliament and Council of the European Union 2009) that could not be screened with in silico programs are listed in Table S3. These items had either been moved or deleted from the list, or they could not be considered due to limitations of ED (e.g., multiple ionization, containing boron or salts) and VTL (e.g., molar mass , containing quaternary nitrogen). These were not considered for further in vitro tests, as the comparison of in vitro results with inconclusive in silico results would not be possible.

Based on the in silico data obtained using ED and VTL, the preservatives with three or more predicted interactions with nuclear receptors of moderate or high binding probabilities with ED or binding at less than with VTL were selected for further in vitro evaluation: triclocarban, triclosan, bromochlorophene, chlorophene, and climbazole.

Agonist and Antagonist Activities of the Selected Preservatives on AR

The recorded relative transcriptional activity (RTA) of AR-EcoScreen cells upon treatment with the five selected preservatives showed significant AR agonist activity for triclocarban, seen as a 40.4% higher AR RTA in cells treated with triclocarban than vehicle control cells treated with 0.1% DMSO (Figure 1A). This activity was less prominent [i.e., 30.3% higher AR RTA over vehicle control (0.1% DMSO)] at the highest noncytotoxic concentration of triclocarban. Cells treated with bromochlorophene had significantly lower AR RTA at the highest noncytotoxic concentration of (58.7% lower than vehicle control cells treated with 0.1% DMSO) in the AR agonist assay (Figure 1A).

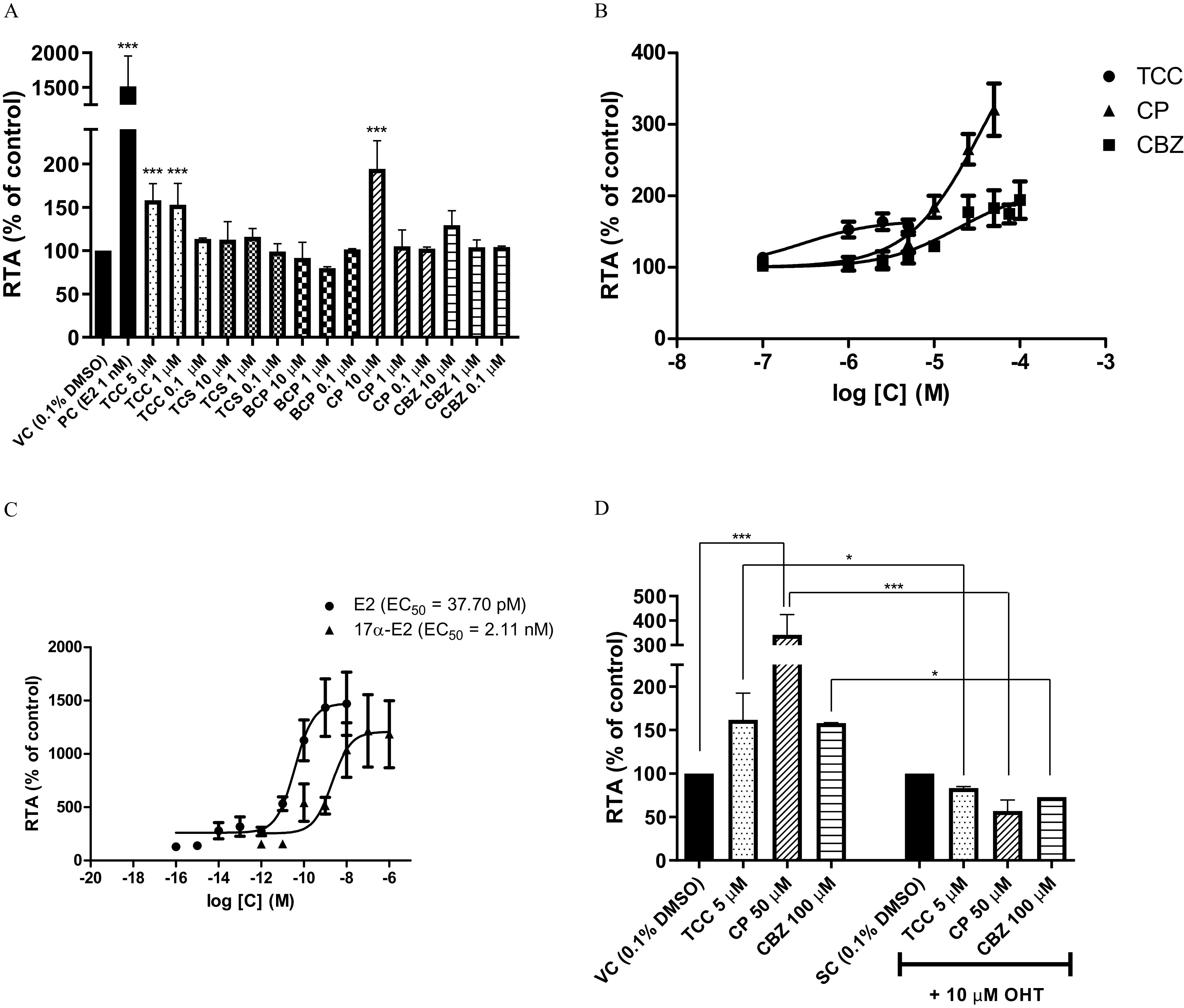

Figure 1.

Effects of preservatives triclocarban (TCC), triclosan (TCS), bromochlorophene (BCP), chlorophene (CP), and climbazole (CBZ) on AR. (A,B) Screening for androgen (A) and antiandrogen (B) activities at 0.1, 1.0 and up to preservatives (as indicated) in AR-EcoScreen cell line. 0.1% DMSO serves as the vehicle control (VC) and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) as the positive control (PC) in (A), whereas 0.1% DMSO with DHT is the spike-in control (SC), and hydroxyflutamide (H-FLU) the PC in (B). 0.1% DMSO alone shows the baseline response as compared to cells induced with a known agonist (SC, 0.1% DMSO with DHT) in (B). (C) Dose–response curves of the preservatives (as indicated) with the PC hydroxyflutamide (H-FLU) in the AR-EcoScreen cell line. (D) Binding affinity of the preservatives (as indicated) to isolated AR, with (DHT) as the PC. Data are (SD) of at least two independent repeats. All of the data were first normalized to the metabolic activities, to allow for any cytotoxic or proliferative effects, followed by normalization to the VC or SC treatments (0.1% DMSO for agonist assay, 0.1% DMSO with DHT for antagonist assay) to obtain the relative transcriptional activities (RTAs). Statistical significance as compared to the VC or SC: *, ; **, ; ***, (one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s post hoc tests). Note: ANOVA, analysis of variance; DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; SD, standard deviation.

In the AR antagonist setup where along with preservatives DHT was added (spike-in control) as indicated in Figure 1B, cells treated with triclocarban had significantly higher AR RTA (39.4% at ; 30.7% at ) than spike-in control (0.1% DMSO with DHT). By contrast, cells treated with each of the other preservatives had lower AR RTA than spike-in control cells treated 0.1% DMSO with DHT (indicating antagonist activities) (Figure 1B,C). In particular, cells treated with triclosan had 81.8% lower AR RTA than spike-in control (0.1% DMSO with DHT), with an estimated of for triclosan. Treatment with bromochlorophene resulted in significantly lower AR-mediated transcription [by 30.7% compared to spike-in control (0.1% DMSO with DHT)], although bromochlorophene could not be tested due to cytotoxicity constraints, and hence an estimated for bromochlorophene could not be determined. Chlorophene was the most potent antagonist, with lower AR RTA at than spike-in control (0.1% DMSO with DHT), and an estimated of (Figure 1B,C). Climbazole showed a 48.5% lower AR RTA at than spike-in control (0.1% DMSO with DHT), with an estimated of .

The binding affinity assays then confirmed the binding of triclosan, bromochlorophene, and chlorophene to AR, with effective concentration at 50% () values of , , and , respectively (Figure 1D). Triclocarban and climbazole did not show binding to the isolated AR.

Agonist and Antagonist Activities of the Selected Preservatives on

In transcriptional activity assays, harnessing the reporter cell line, three of the selected preservatives showed agonist activities (Figure 2). Here, cells treated with triclocarban and its highest noncytotoxic concentration of triclocarban had significantly higher RTA (by 53% and 58%, respectively) than vehicle control (cells treated with 0.1% DMSO). Chlorophene treatment resulted in the highest RTA, at almost 2-fold the vehicle control (0.1% DMSO) at , with no effect on RTA seen at 1/10 the concentration (i.e., chlorophene treatment). In addition to triclocarban and chlorophene treatments, the cells treated with climbazole also had higher RTA than vehicle control (cells treated with 0.1% DMSO), by at (indicating agonist activity), although this did not reach statistical significance (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Agonist effects of preservatives triclocarban (TCC), triclosan (TCS), bromochlorophene (BCP), chlorophene (CP), and climbazole (CBZ) on in the cell line. (A) Screening for estrogen activities at 0.1, 1 and up to preservatives (as indicated). 0.1% DMSO serves as the vehicle control (VC) and (E2) as the positive control (PC). (B) Dose–response curves of preservatives (as indicated). (C) Dose–response curves of the PCs E2 and (). (D) Competitive agonist assay where TCC, CP and CBZ were tested alone and with hydroxytamoxifen (OHT). 0.1% DMSO and 0.1% DMSO with OHT serve as the VC and the spike-in control (SC), respectively. Data are of at least two independent repeats. All of the data were first normalized to the metabolic activities, to allow for any cytotoxic or proliferative effects, followed by normalization to the VC or SC treatments (0.1% DMSO for agonist assays, 0.1% DMSO with OHT for competitive assay) to obtain the relative transcriptional activities (RTAs). Statistical significance as compared to the VC or SC: *, ; ***, [one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s post hoc tests and Bonferroni’s post hoc test in (D) only]. Note: ANOVA, analysis of variance; DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; SD, standard deviation.

Triclocarban, chlorophene and climbazole were further evaluated for their agonist activities here, from to . However, precipitation and cytotoxicity limited the highest tested concentrations to for triclocarban, and for chlorophene. Climbazole showed agonist activity, with 94% higher RTA than vehicle control (0.1% DMSO) in cells treated with climbazole, as compared with 36.6% higher RTA than vehicle control (0.1% DMSO) in cells treated with climbazole in the screening assay. A greater dose-dependent increase was seen with chlorophene, where the RTA was 3.2-fold the vehicle control (0.1% DMSO) in cells treated with chlorophene (Figure 2B). The positive controls in this cell line of E2 and are shown separately in Figure 2C.

Each preservative that showed ER agonist activity was also tested for false positivity at the concentration where their estrogenic effects were most prominent (Figure 2D). The estrogenic effects of all of these preservatives were completely reversed by the ER antagonist, as hydroxytamoxifen.

In the antagonist setup, where along with preservatives E2 was added (spike-in control) as indicated in Figure 3A, the estrogenic effects of triclocarban persisted (Figure 3A), although this was only seen at triclocarban. Cells treated with triclosan had lower RTA by 25.7% from the spike-in control (0.1% DMSO with E2). Due to cytotoxicity constraints of triclosan at higher concentrations, a dose–response curve could not be generated. Bromochlorophene was however a more potent antagonist here, with lower RTA than spike-in control (0.1% DMSO with E2) in cells treated with bromochlorophene, and an of (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Antagonist effects of preservatives triclocarban (TCC), triclosan (TCS), bromochlorophene (BCP), chlorophene (CP), and climbazole (CBZ) on ER in the cell line. (A) Screening for antiestrogen activities at 0.1, 1 and up to preservatives (as indicated). 0.1% DMSO with (E2) serves as the spike-in control (SC) and hydroxytamoxifen (OHT) as the positive control (PC). 0.1% DMSO alone shows the baseline response as compared to cells induced with a known agonist (SC, 0.1% DMSO with E2) in (A). (B) Dose–response curves of BCP and the PC tamoxifen (TAM). Dose-response curve for TCS could not be generated due to cytotoxicity constraints. Data are of at least two independent repeats. All of the data were first normalized to the metabolic activities, to allow for any cytotoxic or proliferative effects, followed by normalization to the SC treatment (0.1% DMSO with E2) to obtain the relative transcriptional activities (RTAs). Statistical significance as compared to the SC: *, ; **, ; ***, (one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s post hoc tests). Note: ANOVA, analysis of variance; SD, standard deviation.

Agonist and Antagonist Activities of the Selected Preservatives on GR

No GR agonist activities were seen for any of these five selected preservatives in the MDA-kb2 cell line. Instead, cells treated with triclosan had a lower GR RTA than vehicle control (0.1% DMSO with FLU), by 53.6% (Figure 4A) in the agonist assay. In the GR antagonist assays, where along with preservatives HC was added (spike-in control) as indicated in Figure 4B, activities were seen for triclocarban [38.9% lower GR RTA than spike-in control (0.1% DMSO with HC) at ], triclosan [53.2% lower GR RTA than spike-in control (0.1% DMSO with HC) at ], and bromochlorophene [85.8% lower GR RTA than spike-in control (0.1% DMSO with HC) at ] (Figure 4B), with bromochlorophene giving an of (Figure 4C). Due to cytotoxicity constraints of triclocarban and triclosan at higher concentrations, dose–response curves could not be generated.

Figure 4.

Effects of preservatives triclocarban (TCC), triclosan (TCS), bromochlorophene (BCP), chlorophene (CP) and climbazole (CBZ) on GR in the MDA-kb2 cell line. (A,B) Screening for glucocorticoid (A) and antiglucocorticoid (B) activities at 0.1, 1 and up to preservatives (as indicated). flutamide (FLU) was used in (A) to prevent for any androgen receptor-mediated transcriptional activity in the MDA-kb2 cell line. 0.1% DMSO with FLU serves as the vehicle control (VC) and hydrocortisone (HC) as the positive control (PC) in (A), whereas 0.1% DMSO with HC is the spike-in control (SC), and mifepristone (RU-486) is the PC in (B). 0.1% DMSO alone shows the baseline response as compared with cells induced with a known agonist (SC, 0.1% DMSO with HC) in (B). (C) Dose–response curves of BCP and the PC mifepristone (RU-486). Dose–response curves for TCC and TCS could not be generated due to cytotoxicity constraints. (D) Binding affinity of the preservatives (as indicated) to isolated GR, with dexamethasone (DEX) as the PC. Data are of at least three independent repeats. All of the data were first normalized to the metabolic activities, to allow for any cytotoxic or proliferative effects, followed by normalization to the VC or SC treatments (0.1% DMSO for agonist assay, 0.1% DMSO with HC for antagonist assays) to obtain relative transcriptional activities (RTAs). Statistical significance as compared to the VC or SC: *, ; ***, (one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s post hoc tests). Note: ANOVA, analysis of variance; DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; SD, standard deviation.

The binding affinity assays then confirmed the binding of triclosan, bromochlorophene, and chlorophene to GR, with values of , , and , respectively (Figure 4D). Triclocarban and climbazole did not show binding to the isolated GR.

Agonist and Antagonist Activities of the Selected Preservatives on and

None of these selected preservatives showed TR agonist activities in GH3.TRE-Luc cell line, and instead, the baseline TR-mediated transcriptional activity in agonist setup was lower in cells treated with triclocarban, and bromochlorophene, and triclosan (Figure 5A) as compared to vehicle control (cells treated with 0.1% DMSO). Similar effects were seen in the tests for TR antagonist activity, where along with preservatives T3 was added (spike-in control) as indicated in Figure 5B, with 44.3%, 71.9%, and 92.9% lower TR RTAs than spike-in control (0.1% DMSO with T3) in cells treated with triclocarban, triclosan, and bromochlorophene, respectively. Due to cytotoxicity constraints of triclocarban at higher concentrations, a dose–response curve could not be generated. Triclosan had an of (Figure 5C), and bromochlorophene had an of (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Effects of preservatives triclocarban (TCC), triclosan (TCS), bromochlorophene (BCP), chlorophene (CP) and climbazole (CBZ) on TR in GH3.TRE-Luc cell line. (A,B) Screening for thyroid (A) and antithyroid (B) activities at 0.1, 1 and up to preservatives (as shown). 0.1% DMSO serves as the vehicle control (VC) and triiodothyronine (T3) as the positive control (PC) in (A), whereas 0.1% DMSO with T3 is the spike-in control (SC), and bisphenol A (BPA) is the PC in (B). 0.1% DMSO alone shows the baseline response as compared with cells induced with a known agonist (SC, 0.1% DMSO with T3) in (B). (C) Dose–response curves of preservatives TCS and BCP and the PC bisphenol A (BPA). Dose–response curve for TCC could not be generated due to cytotoxicity constraints. Data are of at least three independent repeats. All of the data were first normalized to the metabolic activities, to allow for any cytotoxic or proliferative effects, followed by normalization to the VC or SC treatments (0.1% DMSO for agonist assay, 0.1% DMSO with T3 for antagonist assay) to obtain the relative transcriptional activities (RTAs). Statistical significance as compared to the VC or SC: *, ; **, ; ***, (one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s post hoc tests). Note: ANOVA, analysis of variance; DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; SD, standard deviation.

Luciferase Inhibition by the Selected Preservatives

Luciferase inhibition tests were carried out to monitor for false-positive data, using TR antagonist reporter assays with the GH3.TRE-Luc cell line, for the expression of firefly luciferase. The preservatives were added to lysates instead of the live cells used in all of the other cell-based assays for transcriptional activation. Inhibition of the luminescence signal of firefly luciferase by the preservatives independent of TR transcriptional activation was evaluated at the same concentrations used in the TR assays, and also at higher concentrations, as seven concentrations from to (Figure 6). The known luciferase inhibitor resveratrol served as the positive control. None of these preservatives significantly inhibited the firefly luciferase at the highest concentration at which they were used in the screening assays (). Triclocarban was the strongest inhibitor here, as it decreased the luminescence signal by 46.7% at , followed by bromochlorophene, with 26.1% inhibition at , and then climbazole, triclosan, and chlorophene with inhibition at .

Figure 6.

Luciferase inhibition by preservatives triclocarban (TCC), triclosan (TCS), bromochlorophene (BCP), chlorophene (CP) and climbazole (CBZ) in GH3.TRE-Luc cell lysates. Dose–response curves of the preservatives (as indicated), and the positive control resveratrol. Data are of at least three independent repeats. Note: SD, standard deviation.

Discussion

To protect human health and the environment, it is critical to limit the use of compounds with endocrine-disrupting properties. Preservatives are compounds that are used for many applications, from active ingredients in cleaning products to additives in personal care products and use in medical devices, kitchenware, office and school products, and clothing. Evaluation of their endocrine-disrupting potential is of key importance for their safe use. Toxicologists are being prompted to bridge the knowledge gap in this field and to provide more data on risk assessment (European Commission 2019).

Here, we used in silico screening to initially prioritize candidate preservatives for further evaluation in in vitro assays for endocrine activities through nuclear receptors. For this, the two in silico tools of ED and VTL were used. Although both have their limitations, and neither could be used to assess all of the 56 preservatives listed in Annex V of the “List of Preservatives Allowed in Cosmetic Products” of Regulation (EC) No. 1223/2009 (European Parliament and Council of the European Union 2009), as reported in the “Results” section herein, they nonetheless proved useful to prioritize candidates from this relatively large data set. Preservatives where in silico prediction was not possible (Table S3) were not further considered for in vitro tests, because the results obtained by in silico and in vitro methods could not be compared. However, these should still be evaluated for endocrine disruption in the future to ensure their safety. Moreover, preservatives with predicted low binding or no binding to nuclear receptors include, e.g., formic acid, which was put on the endocrine disruptor assessment list by ECHA (ECHA 2019); hence it is our opinion that the in silico evaluation provided herein should be the basis for prioritization of preservatives for further testing, as opposed to considering preservatives with predicted low binding or no binding to nuclear receptors as safe.

Based on in silico results, we selected five preservatives for cell-based tests for AR, , GR, and TR disruption. All five selected preservatives (triclocarban, triclosan, bromochlorophene, chlorophene, and climbazole) were previously called for evaluation by KEMI due to endocrine-disruption concerns. Triclocarban, triclosan, and climbazole are listed as suspected EDCs (ECHA 2018, 2020a, 2020b) and are under assessment as endocrine disrupting by ECHA. Additionally, triclosan and triclocarban were included in a call by the European Commission for scientific information relevant to safety assessments of selected ingredients in cosmetic products that potentially have endocrine-disrupting properties (European Commission 2019). At least one of the two in silico tools used here had predicted some degree of interaction with nuclear receptors, as was also confirmed in vitro for all of the preservatives, except for chlorophene on GR, and climbazole on , where both ED and VTL failed to define these preservatives as GR and disruptors, respectively. Low sensitivity was observed with ED for , where in silico prediction did not match with the in vitro data for four out of five preservatives (ED predicted only one interaction with correctly (a true positive—the in silico prediction matched our in vitro result), whereas there were four false negatives—the in silico predictions falsely assigned no binding, but we observed activity in vitro). ED was shown to have a low positive predictive value when evaluated with in vitro results in the Tox21 database (Kenda and Sollner Dolenc 2020), at the expense of predicting negative results more accurately, which is useful for screening studies of chemicals (Kolšek et al. 2014b). However, this was not the case for in the present study. In contrast, VTL had better sensitivity for , thus exemplifying the importance of considering more than one in silico method. Comparisons between in silico (this study) and in vitro (this study, previous studies) data are given in Tables 2–6 for each of the five selected preservatives here: triclocarban, triclosan, bromochlorophene, chlorophene, and climbazole.

Table 2.

Triclocarban interference with nuclear receptor function in the present in silico and in vitro study and previous studies.

| Systema | Androgen receptor | Estrogen | Glucocorticoid receptor | Thyroid receptor | Other nuclear receptorsb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endocrine Disruptome binding probability classc | Orange (an) | Orange | Yellow | Yellow (), yellow () | Green |

| VirtualToxLab™ binding prediction | No binding | No binding | (MR), no binding to others | ||

| Previous cell-based in vitro assays | Enhancer of testosterone activity in T47D-ARE cells (Ahn et al. 2008) | Enhancer of activity in BG1-ERE cells (Ahn et al. 2008) | Enhancer of HC activity in MDA-kb2 cells (Kolšek et al. 2014a) | — | — |

| Enhancer of testosterone activity in HEK-2933Y cells (Ahn et al. 2008; Chen et al. 2008) | Agonist in BG1-ERE cells (Ahn et al. 2008) | — | — | — | |

| Enhancer of activity in MDA-kb2 cells (Christen et al. 2010; Kolšek et al. 2014a; Tarnow et al. 2013) | Enhancer of activity in cells (Tarnow et al. 2013) | — | — | — | |

| Previous binding affinity assays | Negative for recombinant AR (Chen et al. 2008) | — | — | — | — |

| In vitro assays in the present study | Agonist (), negative in binding affinity assay on isolated AR | Agonist () | Antagonist (), negative in binding affinity assay on isolated GR | Antagonist () | — |

Note: —, no data; an, antagonist conformation; AR, androgen receptor; , estrogen receptor ; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; , thyroid receptor ; , thyroid receptor .

Endocrine Disruptome and VirtualToxLab™ are in silico tools used to perform molecular docking to nuclear receptors. Previous cell-based in vitro assays sum up findings of other studies on endocrine disruption in reporter gene cell lines. Previous binding affinity assays sum up findings of other studies on binding to respective nuclear receptors. In vitro assays in the present study include reporter gene assays in cell lines AR-EcoScreen, , MDA-kb2, GH3.TRE-Luc, and binding affinity assays on isolated AR and GR.

Other receptors in Endocrine Disruptome: , estrogen receptor ; , liver X receptor ; , liver X receptor ; , peroxisome proliferator activated receptor ; , peroxisome proliferator activated receptor ; , peroxisome proliferator activated receptor ; , retinoid X receptor . Other receptors in VirtualToxLab™: , estrogen receptor ; LXR, liver X receptor; MR, mineralocorticoid receptor; , peroxisome proliferator activated receptor ; PR, progesterone receptor.

Endocrine Disruptome binding probability classes are as follows: class red for high binding probability; class orange for moderate binding probability; class yellow for low binding probability; class green for very low/no binding probability. Binding free energy threshold values for each receptor are further defined in Table S4.

Table 6.

Climbazole and its potential to interfere with nuclear receptor function observed in silico and in vitro by this study and previous studies.

| Systema | Androgen receptor | Estrogen | Glucocorticoid receptor | Thyroid receptor | Other nuclear receptorsb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endocrine Disruptome binding probability classc | Orange (an) | Green | Green | Yellow (), yellow () | Green |

| VirtualToxLab™ binding prediction | No binding | () | (MR), (), (PR), no binding to others | ||

| Previous yeast based in vitro assays | No effect (Westlund and Yargeau 2017) | No effect (Westlund and Yargeau 2017) | — | — | — |

| In vitro assays in the present study | Antagonist (), negative in binding affinity assay on isolated AR | Agonist () | Negative (), negative in binding affinity assay on isolated GR | Antagonist () | — |

Note: —, no data; an, antagonist conformation; AR, androgen receptor; , estrogen receptor ; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; , thyroid receptor ; , thyroid receptor .

aEndocrine Disruptome and VirtualToxLab™ are in silico tools used to perform molecular docking to nuclear receptors. Previous yeast based in vitro assays sum up findings of other studies on endocrine disruption in reporter yeast assays. In vitro assays in the present study include reporter gene assays in cell lines AR-EcoScreen, , MDA-kb2, GH3.TRE-Luc, and binding affinity assays on isolated AR and GR.

Other receptors in Endocrine Disruptome: , estrogen receptor ; , liver X receptor ; , liver X receptor ; , peroxisome proliferator activated receptor ; , peroxisome proliferator activated receptor ; , peroxisome proliferator activated receptor ; , retinoid X receptor . Other receptors in VirtualToxLab™: , estrogen receptor ; LXR, liver X receptor; MR, mineralocorticoid receptor; , peroxisome proliferator activated receptor ; PR, progesterone receptor.

Endocrine Disruptome binding probability classes are as follows: class red for high binding probability; class orange for moderate binding probability; class yellow for low binding probability; class green for very low/no binding probability. Binding free energy threshold values for each receptor are further defined in Table S4.

Stably transfected transactivation assays are frequently used for in vitro evaluation of the endocrine-disrupting potential of chemicals (Grimaldi et al. 2015). These assays provide information on the binding of chemicals to nuclear receptors in a cell, and consequently their induction or suppression of the transcription of hormone-responsive genes (Grimaldi et al. 2015). At the same time, they do not identify EDCs that interact with other aspects within the endocrine system (e.g., receptors, enzymes), or EDCs that interfere with hormone synthesis, metabolism, distribution, and clearance (OECD 2016a, 2016b). Typically, firefly luciferase is used as the reporter gene, under the control of a promoter that includes the relevant hormone response elements—the binding sites for the nuclear receptors (Grimaldi et al. 2015). Upon binding of EDCs to the nuclear receptor, the luciferase enzyme is produced and can be quantified as decreased or increased luminescence (Thorne et al. 2010).

Limitations of the luciferase reporter assays include nonspecific induction of the promoter that drives the luciferase gene expression (e.g., genistein in the cell line; OECD 2016a), stabilization or inhibition of the reporter gene product (i.e., the luciferase enzyme), and lack of complexity of the promoters that drive the reporter gene expression (Thorne et al. 2012). Generally, the promoters in reporter cell lines contain hormone response elements and cannot account for the more complex control of hormone-responsive genes that do not contain hormone response elements in their promoters, but that have binding sites for coactivating transcription factors instead (Gertz et al. 2013). Indeed, many studies where such systems are used do not pay sufficient attention to changes in the luminescence signals that originate from cytotoxic or proliferative effects of the compounds under investigation (Berckmans et al. 2007; Huang et al. 2014).

All five preservatives in this study showed similar relative luciferase transcriptional activities in the GH3.TRE-Luc reporter cell line when they were screened for TR agonist and antagonist activities. With the comparable decreases in the luciferase activities in both of these assays, we suspected that these preservatives might be inhibiting firefly luciferase and hence be false positives in the TR antagonist assay. This effect is well known for resveratrol (Bakhtiarova et al. 2006), as well as for compounds that include phenyl groups, for example (Diller et al. 2008). However, the tests for false positives here removed this worry that the TR antagonist activity was due to inhibitory effects on the product of the reporter gene in the cell lines used (i.e., the firefly luciferase enzyme), because none of these preservatives showed significant inhibition at the highest concentrations tested in the screening assays (). However, TR agonist effects of these preservatives might have been reduced at . Based on the negative results in luciferase inhibition assays at for all five of the preservatives, we propose that the similarities between the data from the TR agonist and antagonist setups for TR-mediated transcriptional activities might be due to decreased expression of TR, or of its cofactors.

Triclocarban was not recognized as safe for long-term daily use due to its suspected endocrine-disrupting properties and its lack of effect (it is not retained on the skin long enough to have antimicrobial properties, and as such, it had been misbranded), with its ban from use in soaps ruled on by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2016 (Wolf 2016), but it is now still allowed in some personal care products and as a disinfectant in the health care industry. Following use of triclocarban-containing soaps by six healthy volunteers, plasma concentrations peaked at within 48 h of exposure, with the highest concentration obtained in a volunteer who regularly used triclocarban-containing soaps (Schebb et al. 2012). Triclocarban has already been shown to enhance testosterone- and DHT-induced transcription of AR-responsive genes, although it has not been reported to have agonist activity of its own (Ahn et al. 2008; Blake et al. 2010; Chen et al. 2008; Christen et al. 2010). A small increase in luminescence was seen for MDA-kb2 cells upon exposure to triclocarban alone, but the signal did not surpass the limit for agonist activity (Blake et al. 2010). In the present study, in this OECD-validated AR-EcoScreen cell line that is more sensitive to androgens than the MDA-kb2 reporter cells, triclocarban was identified as an agonist without and with DHT induction of AR-mediated transcription, at to . In support of our findings, Ankley et al. (2010) reported increased masculinization in the fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas) upon exposure to triclocarban. In addition, Chen et al. (2008) observed an increase in weight of the accessory sex organs in testosterone- and triclocarban-treated castrated rats, as well as in intact immature male rats, which thus confirmed that triclocarban can mimic androgens in vivo (Ankley et al. 2010; Chen et al. 2008; Duleba et al. 2011). The AR agonist effects of triclocarban when in combination with DHT were blocked by FLU, which thus confirmed the AR-mediated mechanism of action (Christen et al. 2010). Contrary to this, Tarnow et al. (2013) reported that expression of AR- and ER-controlled genes was unchanged upon exposure to triclocarban, and that the increased luminescence in reporter gene assays was due to stabilization of firefly luciferase (Tarnow et al. 2013). No binding of triclocarban to the isolated AR was shown in the present study, and Chen et al. (2008) supported this claim. Triclocarban has previously been shown to enhance E2 activity and to be an ER agonist in a firefly luciferase–based assay (Ahn et al. 2008; Yueh et al. 2012). Tarnow et al. (2013) also showed that triclocarban did not induce proliferation of E2-dependent MCF-7 cells. However, stabilization of the firefly luciferase enzyme does not explain why the potent antagonist hydroxytamoxifen blocked all of the triclocarban-induced luminescence, as shown here. This suggests that the luciferase transcriptional activities seen in this study were indeed mediated through ER and were not a consequence of nonspecific induction of the reporter gene. We propose that triclocarban might be an AR and ER agonist that acts through these respective nuclear receptors, although further adverse effects of triclocarban need to be confirmed in vivo. Thus far for triclocarban, Yueh et al. (2012) showed up-regulation of CYP2B6 and CYP1B1 in mice ovaries, and Zenobio et al. (2014) reported up-regulation of estrogen-sensitive vitellogenin transcripts in male and female fathead minnows (Yueh et al. 2012; Zenobio et al. 2014). Down-regulation of the ar gene transcript was seen only in male minnows (Zenobio et al. 2014). Triclocarban also enhanced AroB expression in zebrafish embryos. Although E2 alone induced an 8-fold increase in AroB transcription, addition of triclocarban produced an 18-fold increase. Interestingly, triclocarban did not enhance bisphenol A–mediated increased AroB transcription in the same study but suppressed it instead (Chung et al. 2011). This is indicative of unforeseeable changes from mixtures with triclocarban on estrogen-responsive genes in vivo. In addition to androgen- and estrogen-sensitive genes, the transcript for steroidogenic acute regulatory protein was down-regulated, and the lipoprotein lipase transcript was up-regulated in the study by Zenobio et al. (2014). A study that addressed the effects of triclocarban on GR showed enhanced HC activity at triclocarban (Kolšek et al. 2014a), whereas in the present study there was a similar, although less potent, response at triclocarban, and GR antagonist activity at triclocarban. There was no GR agonist activity of triclocarban alone, as also seen by Yueh et al. (2012). The present findings here and those from previous studies on triclocarban are summarized in Table 2.

As with triclocarban, in 2016 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration also banned the antimicrobial triclosan for use in soaps (Weatherly and Gosse 2017), although it is still widely included in toothpastes and mouthwash solutions; i.e., cosmetic products where oral ingestion of triclosan is probable. Following ingestion of a single dose of mouthwash by 10 healthy volunteers (5 of whom were regularly using triclosan-containing products), plasma concentrations peaked at (as opposed to preexperiment median triclosan plasma baseline concentration of ) up to 3 h after exposure (Sandborgh-Englund et al. 2006). Many studies have found triclosan in human urine (Heffernan et al. 2015; Philippat et al. 2013; Provencher et al. 2014; Yin et al. 2016), blood (Allmyr et al. 2006, 2008), breast milk (Adolfsson-Erici et al. 2002; Allmyr et al. 2006; Toms et al. 2011), and amniotic fluid (Philippat et al. 2013). Studies on triclosan as a disruptor of the androgen, estrogen, and thyroid hormone axes are inconclusive. Rostkowski et al. (2011) showed antiandrogenic activity for triclosan in an anti-YAS assay, with an of triclosan, and in an AR-CALUX assay, with an of triclosan. In the present study with the OECD-validated AR-EcoScreen cell line, triclosan showed a considerably higher of . In line with the present study, many previous studies have confirmed the antiandrogenic effects of triclosan in cell-based reporter gene in vitro assays (Table 3) (Ahn et al. 2008; Chen et al. 2007; Di Paolo et al. 2016; Gee et al. 2008; Kolšek et al. 2014a; Lange et al. 2015; Tamura et al. 2006). Conversely, Christen et al. (2010) showed that triclosan was an AR agonist in the MDA-kb2 cell line, as cells treated with triclosan had higher AR RTA than the control (Christen et al. 2010). Additionally, in an antagonist setup where DHT was added, triclosan enhanced DHT-induced AR RTA (Christen et al. 2010). The same study demonstrated that the AR agonist activity in was indeed AR driven, as the potent AR antagonist, at FLU completely inhibited the response (Christen et al. 2010). Although triclosan was an antagonist on AR and ER in the present study, similar effects of treatments with the AR and ER agonist triclocarban for fathead minnows have been seen in vivo—the AR gene transcript and the transcript for steroidogenic acute regulatory protein were down-regulated (Zenobio et al. 2014). Antiandrogenic effects of triclosan were shown in male rats (decrease in testicular weight) by Kumar et al. (2009), but no change in the weight of the accessory sex organs was seen in Hershberger assays by Farmer et al. (2018). In Yellow River carp (Cyprinus carpio), triclosan was shown to increase serum E2 levels (due to increased aromatase expression), to increase synthesis and secretion of ER in female carp, and to decrease AR gene transcripts in male carp (Wang et al. 2017, 2018). The ER-dependent growth of ovarian cancer cell lines and the AR-mediated prostate cancer cell proliferation and migration support triclosan as a xenoestrogen and xenoandrogen, respectively (Kim et al. 2014, 2015). Triclosan was shown to have no (anti)estrogenic effects in vitro, although it interfered with E2 responses in vivo (Serra et al. 2018). Triclosan up-regulated AR and ER in the placenta of pregnant rats, and decreased serum E2 and testosterone levels (Feng et al. 2016). Although it is generally accepted that triclosan interferes with thyroid hormone–controlled gene expression and has effects in vivo, there are studies that show no effects with respect to TR agonist and antagonist activities, and some that claim triclosan is a TR antagonist (Cao et al. 2018; Crofton et al. 2007; Fort et al. 2010, 2011; Paul et al. 2010; Veldhoen et al. 2006; Zhang et al. 2018; Zhou et al. 2017). The present study confirms that triclosan is a TR antagonist in the GH3.TRE-Luc reporter cell line, with an of . Our findings and data from previous studies on triclosan are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Triclosan interference with nuclear receptor function in the present in silico and in vitro study and previous studies.

| Systema | Androgen receptor | Estrogen | Glucocorticoid receptor | Thyroid receptor | Other nuclear receptorsb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endocrine Disruptome binding probability classc | Yellow (an) | Green | Yellow | Green (), green () | Green |

| VirtualToxLab™ binding prediction | (), () | (LXR), (MR), (), (PR), no binding to others | |||

| Previous cell based in vitro assays | Antagonist in HEK-2933Y cells (Chen et al. 2007) | Antagonist in BG1-ERE cells (Ahn et al. 2008) | No effect in MDA-kb2 at (Kolšek et al. 2014a) | No effect in ZFL cell line (Zhou et al. 2017) | — |

| Antagonist in stably transfected LTR-CAT gene in S115 +A cells (Gee et al. 2008) | Antagonist in stably transfected ERE-CAT gene in MCF7 cells (Gee et al. 2008) | — | — | — | |

| Antagonist in transiently transfected LTR-CAT gene in T47D cells (Gee et al. 2008) | Negative for agonist activity in ER-CALUX (Houtman et al. 2004) | — | — | — | |

| Antagonist in MDA-kb2 cells (Kolšek et al. 2014a; Tamura et al. 2006) | No effect in ZFL and human-derived MELN cell lines (Serra et al. 2018) | — | — | — | |

| Antagonist in T47D-ARE cells (Ahn et al. 2008) | — | — | — | — | |

| Enhancer of activity in MDA-kb2 cells (Christen et al. 2010) | — | — | — | — | |

| Agonist in MDA-kb2 cells (Christen et al. 2010) | — | — | — | — | |

| Antagonist at in stickleback AR reporter assay (Lange et al. 2015) | — | — | — | — | |

| Antagonist in stably transfected U2OS cell line (Di Paolo et al. 2016) | — | — | — | — | |

| Previous yeast based in vitro assays | Antagonist (Rostkowski et al. 2011) | — | — | — | — |

| Previous binding affinity assays | Positive for recombinant AR (Gee et al. 2008) | Positive for ER of MCF7 cytosol and recombinant (Gee et al. 2008) | — | — | — |

| In vitro assays in the present study | Antagonist (), positive in binding affinity assay on isolated AR () | Antagonist () | Antagonist (), positive in binding affinity assay on isolated GR () | Antagonist () | — |

Note: —, no data; an, antagonist conformation; AR, androgen receptor; , estrogen receptor ; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; , thyroid receptor ; , thyroid receptor .

Endocrine Disruptome and VirtualToxLab™ are in silico tools used to perform molecular docking to nuclear receptors. Previous cell-based in vitro assays sum up findings of other studies on endocrine disruption in reporter gene cell lines. Previous yeast based in vitro assays sum up findings of other studies on endocrine disruption in reporter yeast assays. Previous binding affinity assays sum up findings of other studies on binding to respective nuclear receptors. In vitro assays in the present study include reporter gene assays in cell lines AR-EcoScreen, , MDA-kb2, GH3.TRE-Luc, and binding affinity assays on isolated AR and GR.

Other receptors in Endocrine Disruptome: , estrogen receptor ; , liver X receptor ; , liver X receptor ; , peroxisome proliferator activated receptor ; , peroxisome proliferator activated receptor ; , peroxisome proliferator activated receptor ; , retinoid X receptor . Other receptors in VirtualToxLab™: , estrogen receptor ; LXR, liver X receptor; MR, mineralocorticoid receptor; , peroxisome proliferator activated receptor ; PR, progesterone receptor.

Endocrine Disruptome binding probability classes are as follows: class red for high binding probability; class orange for moderate binding probability; class yellow for low binding probability; class green for very low/no binding probability. Binding free energy threshold values for each receptor are further defined in Table S4.

Bromochlorophene is a preservative that was used in various personal care products where there was dermal (e.g., deodorants, soaps) and oral (e.g., dental care products) human exposure (Stibany et al. 2017), yet there is a lack of human exposure data and lack of data on environmental concentrations. Bromochlorophene has been rarely evaluated, and to the best of our knowledge, there have not been any studies that have looked into its effects on nuclear receptors to date. The present study showed that bromochlorophene can act as an antagonist on AR, , GR, and TR in vitro (Table 3). As opposed to its less halogenated analog, chlorophene, bromochlorophene did not have any agonist activity on . Based on OECD test guidelines 455 and 458 (OECD 2016a, 2016b), bromochlorophene was an AR antagonist and an antagonist. We have seen the same effects on GR and TR in non-OECD–validated cell lines, which might indicate that bromochlorophene can actually inhibit the reporter enzyme and not decrease its transcription in these luciferase reporter assays. This was not supported, however, by the luciferase inhibition assay we developed here. Also, as the baseline luminescence did not decrease in the agonist assays in the two cell lines, this speaks against bromochlorophene being a luciferase inhibitor. Additionally, bromochlorophene was positive in the binding assays with the isolated AR () and GR (). Thus, we can be confident that the AR, , GR, and TR antagonist activities of bromochlorophene in vitro represent true biological observations. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of antagonist activity of bromochlorophene on GR and TR. Our findings on bromochlorophene are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Bromochlorophene interference with nuclear receptor function in the present in silico and in vitro study.

| Systema | Androgen receptor | Estrogen | Glucocorticoid receptor | Thyroid receptor | Other nuclear receptorsb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endocrine Disruptome binding probability classc | Yellow (an) | Green | Yellow | Yellow () | Green |

| VirtualToxLab™ binding prediction | (), () | (MR), (), (PR), no binding to others | |||

| In vitro assays in the present study | Antagonist (), positive in binding affinity assay on isolated AR () | Antagonist () | Antagonist (), positive in binding affinity assay on isolated GR () | Antagonist () | — |

Note: —, no data; an, antagonist conformation; AR, androgen receptor; , estrogen receptor ; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; , thyroid receptor ; , thyroid receptor .

Endocrine Disruptome and VirtualToxLab™ are in silico tools used to perform molecular docking to nuclear receptors. In vitro assays in the present study include reporter gene assays in cell lines AR-EcoScreen, , MDA-kb2, GH3.TRE-Luc, and binding affinity assays on isolated AR and GR.

Other receptors in Endocrine Disruptome: , estrogen receptor ; , liver X receptor ; , liver X receptor ; , peroxisome proliferator activated receptor ; , peroxisome proliferator activated receptor ; , peroxisome proliferator activated receptor ; , retinoid X receptor . Other receptors in VirtualToxLab™: , estrogen receptor ; LXR, liver X receptor; MR, mineralocorticoid receptor; , peroxisome proliferator activated receptor ; PR, progesterone receptor.

Endocrine Disruptome binding probability classes are as follows: class red for high binding probability; class orange for moderate binding probability; class yellow for low binding probability; class green for very low/no binding probability. Binding free energy threshold values for each receptor are further defined in Table S4.

Chlorophene is a disinfectant that is included in cosmetics and cleaning products used in hospitals, households, and industrial and farming plants, and it can thus enter the water environment at high concentrations and with seasonal dependence (Arlos et al. 2015; Benitez et al. 2013). It was shown to be mutagenic in in vitro bacterial and mammalian assays and to increase incidence of neoplasms in mice (Yamarik 2004), and it was rejected by the European Chemicals Agency in 2017 (ECHA 2017) as a biocidal product type 2 and 3 due to hazards it might pose to operators handling such products. A previously shown of for chlorophene as an AR antagonist in anti-YAS assays (Rostkowski et al. 2011) is lower than the of obtained in the present study using an OECD-validated assay. Rostkowski et al. (2011) reported an for chlorophene of in AR-CALUX assays. On the basis of the substantially different membrane compositions between yeast and mammalian cells, stronger antagonist activity in yeast might be expected, whereas the different values between the two assays based on mammalian cells might be due to species and tissue type differences (e.g., AR-CALUX is a human bone tissue cell line, whereas AR-EcoScreen cells originate from CHO cells). Contradictory data have been published on chlorophene actions on ER thus far. Houtman et al. (2004) reported no effects on ER in their ER-CALUX cell line, but Schmitt et al. (2012) showed that chlorophene can mimic estrogen in YAS assays with an in the picomolar range (Houtman et al. 2004; Schmitt et al. 2012). Using the OECD-validated cell line in our study, we showed agonist activity of chlorophene at concentrations from to . Furthermore, this effect was shown here to be mediated by , because it was reversed by hydroxytamoxifen, and it was thus not a consequence of nonspecific transcriptional activation (i.e., a false positive). Based on these data, chlorophene meets the OECD criteria (OECD 2016a, 2016b) for an EDC: it is a confirmed antagonist on AR, and a confirmed agonist on . According to our in silico analyses, chlorophene might interfere with GR and TR as well, but it only showed potential as a TR antagonist in vitro at . To the best of our knowledge, chlorophene has not previously been shown to disrupt TR function. Our findings and data from previous studies on chlorophene are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Chlorophene interference with nuclear receptor function in the present in silico and in vitro study and previous studies.

| Systema | Androgen receptor | Estrogen | Glucocorticoid receptor | Thyroid receptor | Other nuclear receptorsb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endocrine Disruptome binding probability classc | Orange (an) | Green | Yellow | Yellow (), Yellow () | Green |

| VirtualToxLab™ binding prediction | (), () | (MR), (PR), no binding to others | |||

| Previous cell based in vitro assays | Antagonist in AR-CALUX assay (Rostkowski et al. 2011) | No effect in ER-CALUX (Houtman et al. 2004) | — | — | — |

| Antagonist at in a stickleback AR reporter assay (Lange et al. 2015) | — | — | — | — | |

| Previous yeast based in vitro assays | Antagonist (Rostkowski et al. 2011) | Agonist () (Schmitt et al. 2012) | — | — | — |

| In vitro assays in the present study | Antagonist (), positive in binding affinity assay on isolated AR () | Agonist () | Negative (), positive in binding affinity assay on isolated GR () | Antagonist () | — |

Note: —, no data; an, antagonist conformation; AR, androgen receptor; , estrogen receptor ; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; , thyroid receptor ; , thyroid receptor .

Endocrine Disruptome and VirtualToxLab™ are in silico tools used to perform molecular docking to nuclear receptors. Previous cell-based in vitro assays sum up findings of other studies on endocrine disruption in reporter gene cell lines. Previous yeast based in vitro assays sum up findings of other studies on endocrine disruption in reporter yeast assays. In vitro assays in the present study include reporter gene assays in cell lines AR-EcoScreen, , MDA-kb2, GH3.TRE-Luc, and binding affinity assays on isolated AR and GR.

Other receptors in Endocrine Disruptome: , estrogen receptor ; , liver X receptor ; , liver X receptor ; , peroxisome proliferator activated receptor ; , peroxisome proliferator activated receptor ; , peroxisome proliferator activated receptor ; , retinoid X receptor . Other receptors in VirtualToxLab™: , estrogen receptor ; LXR, liver X receptor; MR, mineralocorticoid receptor; , peroxisome proliferator activated receptor ; PR, progesterone receptor.

Endocrine Disruptome binding probability classes are as follows: class red for high binding probability; class orange for moderate binding probability; class yellow for low binding probability; class green for very low/no binding probability. Binding free energy threshold values for each receptor are further defined in Table S4.

Climbazole is a fungicide used as a preservative in personal care products; e.g., in creams and antidandruff shampoos. As a preservative, its concentration must not exceed 0.2% in leave-on products or 0.5% in rinse-off hair care products (SCCS 2018b). However, up to 2% climbazole is allowed in products when it is used as an active agent and not as a preservative; e.g., in antidandruff shampoos (SCCS 2018b). Recent calls from regulatory authorities to investigate climbazole in terms of endocrine disruption have put emphasis on this preservative (KEMI 2017; ECHA 2020a). The present study is the first to show that climbazole can act as an agonist and as an AR and TR antagonist. The mode of action through was further confirmed in a competitive assay with an antagonist, hydroxytamoxifen. Climbazole is thus a true agonist per OECD test guideline 455 in the mammalian cell line. Contradictory data were published in terms of a yeast-based assay, where climbazole showed no (anti)androgenic or (anti)estrogenic effects in YES/YAS tests (Westlund and Yargeau 2017). Climbazole was not active on GR in the MDA-kb2 cell line or in the binding affinity assay on the isolated GR, though Zhang et al. (2019) showed that climbazole affected transcription of genes in the steroidogenesis pathway in zebrafish at environmentally relevant concentrations (Zhang et al. 2019). Our findings and data from previous studies on climbazole are summarized in Table 6.