Abstract

Background:

Congregate settings have been disproportionately affected by coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Our objective was to compare testing for, diagnosis of and death after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection across 3 settings (residents of long-term care homes, people living in shelters and the rest of the population).

Methods:

We conducted a population-based prospective cohort study involving individuals tested for SARS-CoV-2 in the Greater Toronto Area between Jan. 23, 2020, and May 20, 2020. We sourced person-level data from COVID-19 surveillance and reporting systems in Ontario. We calculated cumulatively diagnosed cases per capita, proportion tested, proportion tested positive and case-fatality proportion for each setting. We estimated the age- and sex-adjusted rate ratios associated with setting for test positivity and case fatality using quasi-Poisson regression.

Results:

Over the study period, a total of 173 092 individuals were tested for and 16 490 individuals were diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection. We observed a shift in the proportion of cumulative cases from all cases being related to travel to cases in residents of long-term care homes (20.4% [3368/16 490]), shelters (2.3% [372/16 490]), other congregate settings (20.9% [3446/16 490]) and community settings (35.4% [5834/16 490]), with cumulative travel-related cases at 4.1% (674/16490). Cumulatively, compared with the rest of the population, the diagnosed cases per capita was 64-fold and 19-fold higher among long-term care home and shelter residents, respectively. By May 20, 2020, 76.3% (21 617/28 316) of long-term care home residents and 2.2% (150 077/6 808 890) of the rest of the population had been tested. After adjusting for age and sex, residents of long-term care homes were 2.4 (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.2–2.7) times more likely to test positive, and those who received a diagnosis of COVID-19 were 1.4-fold (95% CI 1.1–1.8) more likely to die than the rest of the population.

Interpretation:

Long-term care homes and shelters had disproportionate diagnosed cases per capita, and residents of long-term care homes diagnosed with COVID-19 had higher case fatality than the rest of the population. Heterogeneity across micro-epidemics among specific populations and settings may reflect underlying heterogeneity in transmission risks, necessitating setting-specific COVID-19 prevention and mitigation strategies.

In Canada, by May 20, 2020, there were 78 500 cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), with 5800 deaths.1 Large urban centres such as the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) shouldered the highest burden.2 By May 20, the 16 490 cases detected in the GTA’s population of 6.8 million3 represented 21% of cases in the country, more than two-thirds of cases in Ontario and a diagnosis per capita rate 1.5 times that of Ontario overall.1,2 As in past outbreaks of respiratory virus,4 congregate settings were disproportionately affected by COVID-19 globally5 and across Canada.6–9 Settings such as long-term care homes and homeless shelters were vulnerable partly owing to design barriers (e.g., shared living quarters and communal spaces) to physical distancing, and underresourcing of infection prevention and control measures.10–14

Lessons from past epidemics suggest that disproportionate risks across settings contribute to the spread and outcomes of infection.15 Thus, a key feature of an epidemic response is quantifying heterogeneity in “what has happened,” a process often referred to as an epidemic appraisal.16,17

As a first step to support epidemic appraisal, we aimed to characterize, using the best available data sources, patterns over time in testing (proportion tested), diagnoses (diagnosed cases per capita, testing positivity) and outcome (death) after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in the GTA across 3 settings for which we have data on the population size: residents of long-term care homes, people using shelters and the rest of the population.

Methods

Study design and setting

We conducted a population-based prospective cohort study of all individuals tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection in the GTA between Jan. 23, 2020, and May 20, 2020. We defined the GTA as the City of Toronto, York, Peel, Halton and Durham public health units.9,18–21

Data sources

We sourced COVID-19 surveillance and laboratory reporting systems, and used person-level data on laboratory-confirmed cases,2 testing and results,22 and death.2

The integrated Public Health Information System (iPHIS) is Ontario’s reportable diseases system.2 Each public health unit submits person-level data to iPHIS, including the date of case report to public health units (case report date); outcomes (e.g., death); case acquisition; demographic characteristics (e.g., sex and age);2 and an outbreak identification number to identify cases related to an outbreak in a specific setting, including long-term care homes and homeless shelters.23,24 Each case was counted once and classified by setting at time of case report.

For testing and positivity data, laboratory and health administrative data sets were linked using unique encoded identifiers and analyzed at ICES.25 Ontario Laboratories Information System (OLIS) contains SARS-CoV-2 infection test data submitted from hospitals, commercial laboratories, the provincial public health laboratory and COVID-19 assessment centres.22 OLIS includes test-episode-level (date, result) and person-level (sex, age, address) data. Patient addresses were used to classify cases in the GTA and residents of long-term care homes. Individuals with a record of emergency department visit or hospital admission in the past year and with a “homelessness” indicator at the time of the service (via linkage to health administrative data) were identified as people experiencing homelessness.26

We estimated the population size of long-term care home residents using the total long-term care home bed capacity in the GTA, assuming complete occupancy.8,27 Population denominators for people using shelters were sourced from public reports28–35 (Appendix 1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/8/4/E627/suppl/DC1). For the rest of the population, we subtracted the above estimates from census-derived GTA population size.3 Thus, the rest of the population includes individuals from other congregate facilities (e.g., retirement homes and jails), and we assumed group-specific population sizes were mutually exclusive and static.

Study period and outcomes

iPHIS data obtained through May 31, 2020 (data cut-off date) were used in our analyses for outcomes including diagnosed cases per capita and case-fatality proportions by case report date. OLIS data obtained through May 27 were used in our analyses for outcomes including proportion of individuals who were tested and proportion of individuals tested positive by testing date.

We defined our study period as confirmed cases reported from Jan. 23, 2020, to May 20, 2020, representing about 4 months since the first confirmed case in the GTA.2 However, we used follow-up data up to May 31, 2020, to minimize potential biases from delays in completing outcomes and reporting. By the end of follow-up (May 31, 2020), less than 5% (4.3%) of confirmed cases had an unknown outcome (neither died nor resolved, influence of lost to follow-up shown in Appendix 2, Supplementary Table 1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/8/4/E627/suppl/DC1). Complete entry of confirmed cases into iPHIS for a given case report date occurs within 3 days,36,37 and thus we assumed complete entry by May 31, 2020, of all cases reported by May 20, 2020. We used the May 27, 2020, OLIS data cut-off date to analyze results of tests sampled by May 20, 2020, because 95% of laboratory results were finalized and reported into OLIS within 6 days of a given testing date.22

Statistical analysis

To examine the completeness of testing data and the accuracy of classification by setting in OLIS, we compared the cumulative cases overall and by setting between OLIS and iPHIS.

We calculated the cumulative and daily number, and proportion of diagnosed cases over time in mutually exclusive categories in iPHIS: congregate settings (long-term care home residents, staff or other [e.g., volunteers], shelters and other congregate outbreak settings [hospitals, correctional facilities, retirement homes, group homes and others not yet classified, such as workplaces]); travel related; and community settings (with v. without epidemiological link). Cases with missing information on setting excluded congregate settings.

We calculated the following measures over time in the 3 settings for which we had data on the population size (long-term care home residents, people using shelters and the rest of the population): cumulative diagnoses per capita, cumulative proportion of population tested, daily and cumulative proportion of individuals who tested positive and the cumulative case-fatality proportion. For the case-fatality proportion over time, a rolling average of 7 days was computed using the centre method.38

We examined the age and sex distributions of diagnoses, proportion tested and death across the 3 settings. We used quasi-Poisson regression models39,40 to estimate test positivity rate ratio and case-fatality rate ratio with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) among long-term care home residents and people using shelters, separately, compared with the rest of the population, and adjusting for age (< 50, 50–59, 60–69, 70–79 and ≥ 80 yr) and sex. Finally, as most residents of long-term care homes were aged 60 years and older, we compared the age- and sex-specific relative ratios of case-fatality proportion and the proportion who tested positive between long-term care home residents and the rest of the population,41,42 restricted to people aged 60 years and older.

We used R version 4.0.243 for data cleaning and analyses.

Ethics approval

The University of Toronto Health Sciences Research Ethics Board (protocol no. 39253) approved the study.

Results

During the study period (Jan. 23 to May 20, 2020), a total of 173 092 individuals were tested for and 16 490 individuals were diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection in the GTA overall, based on OLIS and iPHIS data, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1:

Comparison across outbreak settings in the Greater Toronto Area in the cumulative risk of diagnosis, testing and case fatality of SARS-CoV-2 infection, as of May 20, 2020

| Measure | LTCH residents | People using shelters | The rest of the population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population size* | 28 316 | 10 588 | 6 808 890 |

| No. of diagnosed cases, overall† | 3368 | 372 | 12 750 |

| Sex, female, no. (%)‡ | 2164 (66.5)§§ | 159 (43.2)§§ | 6827 (53.9)§§ |

| Age, yr, no. (%) | |||

| < 50 | 20 (0.6) | 270 (72.6) | 6548 (51.4) |

| 50–59 | 48 (1.4) | 61 (16.4) | 2712 (21.3) |

| 60–69 | 190 (5.6) | 23 (6.2) | 1771 (13.9) |

| 70–79 | 592 (17.6) | 14 (3.8) | 755 (5.9) |

| ≥ 80 | 2518 (74.8) | 4 (1.1) | 964 (7.6) |

| No. of individuals tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection, overall§ | 21 617 | NA¶¶ | 150 077 |

| Sex, female, no. (%) | 14 802 (68.5) | NA¶¶ | 93 358 (62.2) |

| Age, yr, no. (%) | |||

| < 50 | 169 (0.8) | NA¶¶ | 77 384 (51.6) |

| 50–59 | 518 (2.4) | NA¶¶ | 28 571 (19.0) |

| 60–69 | 1593 (7.4) | NA¶¶ | 18 601 (12.4) |

| 70–79 | 3598 (16.6) | NA¶¶ | 10 256 (6.8) |

| ≥ 80 | 15 739 (72.8) | NA¶¶ | 15 265 (10.2) |

| No. of deaths among diagnosed cases, overall† | 918 | 3 | 516 |

| Sex, female, no. (%)‡ | 534 (59.9) | 0 (0) | 211 (40.9) |

| Age, yr, no. (%) | |||

| < 50 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 22 (4.3) |

| 50–59 | 7 (0.8) | 2 (66.7) | 41 (7.9) |

| 60–69 | 35 (3.8) | 0 (0) | 87 (16.9) |

| 70–79 | 132 (14.4) | 1 (33.3) | 122 (23.6) |

| ≥ 80 | 744 (81.0) | 0 (0) | 244 (47.3) |

| Diagnosed cases per 100 000 | |||

| Absolute value | 11 894 | 3513 | 187 |

| Relative value | 63.6 | 18.8 | Reference |

| Percentage of population tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection | |||

| Absolute value | 76.3 | NA¶¶ | 2.2 |

| Relative value | 34.7 | NA¶¶ | Reference |

| Percentage of individuals tested positive¶ | |||

| Absolute value | 15.1 | NA¶¶ | 7.9 |

| Relative value | 1.9 | NA¶¶ | Reference |

| Age- and sex-adjusted test positivity rate ratio (95% CI)** | 2.4 (2.2–2.7) | NA¶¶ | Reference |

| p value†† | < 0.001 | NA¶¶ | Reference |

| Case-fatality proportion‡‡ | |||

| Absolute value | 27.3 | 0.8 | 4.0 |

| Relative value | 6.8 | 0.2 | Reference |

| Age- and sex-adjusted case-fatality rate ratio (95% CI)** | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 0.4 (0 – 2.5) | Reference |

| p value†† | 0.02 | 0.5 | Reference |

Note: CI = confidence interval, GTA = Greater Toronto Area, LTCH = long-term care home, NA = not available, OLIS = Ontario Laboratory Information System, SARS-CoV-2 = severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

The population size of LTCH residents was approximated by the total LTCH bed capacity in the GTA; the population size of people using shelters was approximated by the estimated number of people experiencing homelessness in the GTA (Appendix 1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/8/4/E627/suppl/DC1); the population size of the rest of the population was estimated by the total census population size of the GTA (6 847 794) subtracting the population size of LTCH residents and people using shelters.

Number of diagnosed cases and number of deaths were sourced from the Integrated Public Health Information System.

Of 16 490 diagnosed cases, 112 LTCH residents, 4 people using shelters and 85 individuals from the rest of the population had unknown sex; of 918 deaths, 27 LTCH residents who died had unknown sex; sex distribution proportions are based on nonmissing information.

Number of individuals tested and number who tested positive were sourced from the OLIS.

For individuals with multiple tests, we selected 1 testing episode per individual based on the following hierarchy: i.e., the earliest testing episode where the individual was confirmed positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection, or their earliest episode where the results were indeterminate, or earliest episode where the individual tested negative.22 We considered individuals with only indeterminate results as positive as most individuals who had indeterminate results tested positive at a later date.

Estimated using quasi-Poisson regression models, adjusting for age and sex.

Partial Wald tests40 were performed to compare the difference in case-fatality rate and test positivity rate across settings estimated by the quasi-Poisson regression models.

A total of 4.3% of confirmed cases had an unknown outcome by the end of follow-up and were considered alive in our calculation. Thus, our estimates could underestimate the case-fatality proportion.

The overrepresentation of women among diagnosed cases of LTCH residents should not be interpreted as increased risk of diagnoses for female residents, as data among all LTCH in Ontario have shown that more than 75% of LTCH beds are occupied by women.27 Similarly, around 43.4% of people using shelters are female (Appendix 1) and 50.9% of the GTA population are female.3

We did not show results pertaining to testing for people using shelters owing to low sensitivity in identifying people using shelters in the OLIS testing data. A total of 1398 individuals had an indication of “homelessness” in OLIS data and had at least 1 test for SARS-CoV-2 infection, comprising 13.2% of people using shelters in the GTA. Of these 1398 individuals who may use shelters, 6.4% tested positive, comprising 24% of all diagnosed cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection in shelters by May 20, 2020.

Data quality

OLIS identified 92.0% (15 149/16 490) of confirmed cases in all settings combined, 97.1% (3269/3368) of confirmed cases in long-term care home residents and 23.9% (89/372) of confirmed cases in people using shelters, compared with iPHIS (Appendix 3, Supplementary Figures 1A–1C, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/8/4/E627/suppl/DC1). Given low sensitivity of OLIS data in identifying people using shelters, we did not report results on testing for this group.

Distribution in diagnoses over time across settings

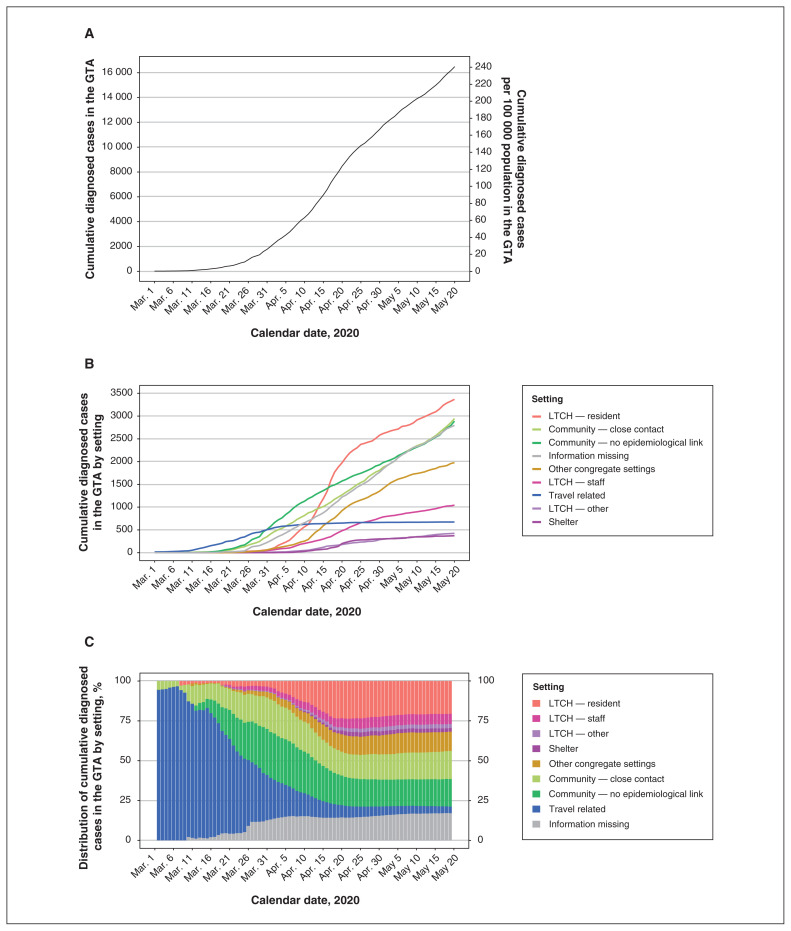

During the study period (Jan. 23 to May 20, 2020), there were 16 490 diagnosed cases (241 cases per 100 000 population) in the GTA overall (Table 1, Figure 1A), with 3368 diagnosed cases among residents of long-term care homes and 372 among people using shelters (Figure 1B). Diagnosed cases with a known travel history accounted for all cases by Feb. 27 and 96.7% of cases by Mar. 7 (Figure 1C).

Figure 1:

The (A) total number, (B) number of diagnosed cases by setting and (C) distribution of cumulative diagnosed coronavirus disease 2019 cases in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) by setting over time. Settings are defined as mutually exclusive categories by the order shown in the graph (C, from top to bottom) in the event of multiple exposures. “LTCH — other” may include volunteers; “other congregate settings” includes hospitals, correctional facilities, retirement homes, group homes and other not yet classified, such as workplaces; the “information missing” category excludes congregate settings. The calendar date refers to the date the case was reported to the public health unit. Data source: Integrated Public Health Information System. Note: LTCH = long-term care homes.

By May 20, 43.6% (7186/16 490) of cumulative cases were diagnosed in congregate settings, and 56.4% (9304/16 490) were diagnosed outside congregate settings, including 4.1% (674/16 490) travel related, 35.4% (5834/16 490) in community settings (17.9% [2945/16 490] with or 17.5% [2889/16 490] without an epidemiological link or close contact), and 17.0% (2796/16 490) with missing information (Figure 1C; Appendix 2, Supplementary Table 2). Of all cases in congregate settings by May 20, 46.9% (3368/7186) were among residents of long-term care homes, 5.2% (372/7186) were among people using shelters, and 47.9% (3446/7186) were among other congregate settings (Appendix 3, Supplementary Figure 2).

In March, diagnoses transitioned from predominantly travel-related cases to cases in community settings. By the end of March, 28.5% (505/1775) of cumulative cases were related to travel, 48.6% (863/1775) were in community settings and 10.3% (183/1775) were in congregate settings (Figure 1C). A sharp increase in cases in congregate settings, particularly among residents of long-term care homes, followed in April. From Apr. 1 to Apr. 20, the proportion of cumulative cases increased in each congregate setting: long-term care home residents (from 4.1% [83/2019] to 23.3% [1976/8476]), long-term care home staff (from 2.8% [56/2019] to 5.7% [482/8476]), people using shelters (from 0.0% [0/2019] to 2.4% [201/8476]) and other congregate settings (from 4.0% [81/2019] to 10.9% [923/8476]). The cumulative proportion of cases in congregate settings remained relatively stable thereafter (Figure 1C).

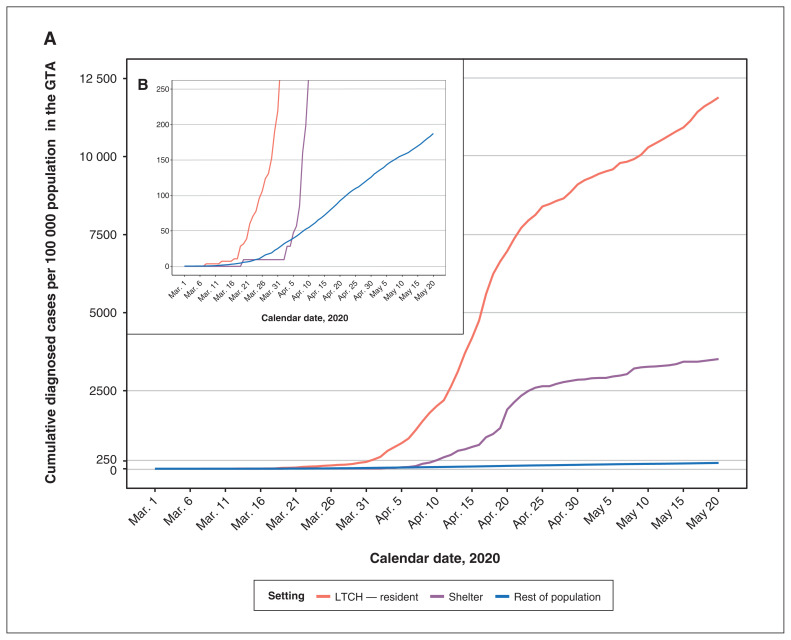

Cumulative diagnoses per capita by setting

Figure 2 shows the cumulative diagnoses per capita by setting over time. Cumulative diagnoses per capita were 64-fold higher among long-term care home residents and 19-fold higher among people using shelters than those of the rest of the population (Table 1).

Figure 2:

(A) Comparison of cumulative diagnosed cases per capita over time by outbreak setting in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA). (B) Shows the same information as (A) but with a different Y-axis range. The calendar date refers to the date the case was reported to the public health unit. Data source: Integrated Public Health Information System. Note: LTCH = long-term care homes.

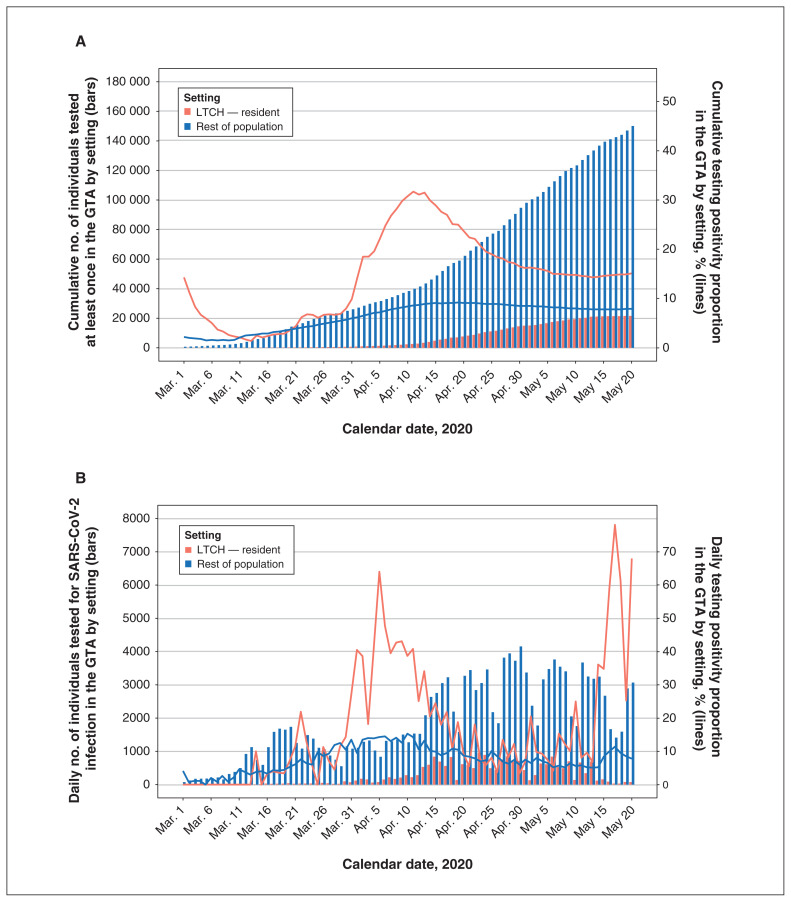

Per capita testing volume and positivity rate

By May 20, 76.3% (21 617/28 316) of residents in long-term care homes had been tested at least once, compared with 2.2% (150 077/6 808 890) of the rest of the population (Table 1). Appendix 3, Supplementary Figure 3 shows the proportions tested by setting over time. The cumulative proportion of individuals who tested positive was 15.1% (3269/21 617, long-term care home residents) and 7.9% (11 791/150 077, rest of the population). Among those tested, the age- and sex-adjusted test positivity rate ratio was 2.4 (95% CI 2.2–2.7) among residents of long-term care homes compared with the rest of the population (Table 1); and the age- and sex-specific test positivity rate ratios ranged from 1.9 to 2.9 (Appendix 2, Supplementary Table 3).

Test positivity of long-term care home residents changed over time with varying testing volume (Figure 3): the daily new testing positivity proportion spiked in early April, with 20%–60% of long-term care home residents testing positive each day. After Apr. 20, and as per capita testing volumes rose, test positivity among residents of long-term care homes fell to around 10%, similar to positivity in the rest of the population (Figure 3B).

Figure 3:

Cumulative (A) and daily (B) number of individuals tested for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection and the proportion of individuals tested positive over time by outbreak setting in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA). The calendar date refers to the date when the specimen was collected. The rest of the population excludes long-term care home (LTCH) residents and people using shelters (defined as individuals who had an indication of “homelessness” in Ontario Laboratories Information System [OLIS]). For individuals with multiple tests, we selected 1 testing episode per individual based on the following hierarchy: the earliest testing episode where the individual was confirmed positive for SARS-CoV-2 infection, or their earliest episode where the results were indeterminate, or earliest episode where the individual tested negative.22 We considered individuals with only indeterminate results as positive as most individuals who had indeterminate results tested positive at a later date. Data source: OLIS.

Case-fatality proportion

Among cases reported by May 20, 918 residents of long-term care homes, 3 people using shelters and 516 from the rest of the population had died, reflecting a case-fatality proportion of 27.3% (918/3368), 0.8% (3/372) and 4.0% (516/12 750), respectively (Table 1). The age- and sex-adjusted case-fatality rate was 1.4 (95% CI 1.1–1.8) times higher among long-term care home residents than among the rest of the population (Table 1), and the age- and sex-specific case-fatality rate ratios ranged from 1.2 to 7.6 (Appendix 2, Supplementary Table 3). The case-fatality proportion remained relatively stable over time from Apr. 15 onward for all settings (Appendix 3, Supplementary Figure 4).

Interpretation

We observed a shift in the proportion of cumulative cases of COVID-19 in the GTA from travel-related cases to cases in long-term care home residents, shelters, other congregate settings and community settings. Long-term care homes and shelters had disproportionate per capita diagnosed cases and, in the context of long-term care home residents, higher case fatality among those diagnosed.

The time-course of the microepidemics raise questions about how transmission may have moved through physical (and thus social) networks defined along intersections of architectural, occupation and socioeconomic factors. By Mar. 14, 2020, long-term care homes had restricted visitations,44–46 and thus connections between residents and the wider community were largely limited to long-term care home staff and volunteers. Efforts in early March to implement enhanced infection control practices, screening, triage and a temporary housing strategy for people experiencing homelessness and who were awaiting test results may have delayed the onset of outbreaks in shelters.47,48 Some community cases may reflect close contacts or an epidemiological link with congregate settings, for example, members of households of people who work or volunteer in facilities.49,50 Thus, alongside fewer contacts outside of households in the community,51 the epidemic may have concentrated in congregate settings and in community households, with additional work needed to discern connections between networks.

The size and trajectory in per capita diagnoses among long-term care home residents and among people using shelters likely reflect underlying differences in testing and differential risk. Early testing in Ontario focused on symptomatic individuals with travel history or who had close contact with a confirmed case.52,53 By Mar. 27, symptomatic individuals in several risk groups, including residents of long-term care homes, were prioritized for testing,54 and after Apr. 15, this included shelters.55 Long-term care home testing was further expanded on Apr. 8 to include asymptomatic individuals with potential exposures (close contacts) or in shared rooms with a symptomatic resident.56 The changing testing criteria corresponded to the observed patterns of surge in cases identified in long-term care homes and shelters in April. After Apr. 21, Ontario began to proactively test every (including asymptomatic) resident and staff member in the long-term care home,57,58 which may partially explain the subsequent decline in long-term care home residents’ test positivity proportions.

The 2.4-fold higher cumulative test positivity among long-term care home residents after adjustment for age and sex, despite wider scope of testing, suggests higher risk transmission environments and may actually be an underestimate of test positivity difference. Testing criteria outside the context of congregate settings were more risk-based (symptoms, epidemiological link, or close contact or exposures) during our study period.59–61 Thus, if risk-based testing yields higher test positivity proportion than population-based testing, and if everyone had been tested in both groups, we would have expected an even higher test positivity rate ratio among long-term care home residents versus the rest of the population. Similarly, the wider scope of testing for long-term care home residents could lead to a larger proportion of diagnoses of people with infection. Therefore, the infection-fatality rate ratio may be even higher than the 1.4 times case-fatality rate ratio observed in the current study between long-term care home residents and the rest of the population. The higher age- and sex-adjusted case-fatality rate among long-term care home residents as compared with the rest of the population may reflect underlying differences in comorbidities associated with COVID-19-attributable mortality or goals of care.62 Future studies including information on comorbidities could help identify causal pathways between residing in long-term care homes and increased case-fatality rate.

Limitations

Our analyses were limited to subpopulations on whom population size denominators were available (e.g., we could not estimate diagnoses per capita for long-term care home staff and for retirement homes). Future work in epidemic appraisal necessitates population size and per capita estimates across each type of outbreak setting and across additional sociodemographic and occupational disaggregation, as these data are now being collected.63–65 For example, occupation data will help distinguish staff cases in the shelter setting. The “rest of the population” subsumed other congregate facilities, and thus our estimates of the relative difference in per capita testing and positivity may be an underestimate, as other facilities (e.g., hospitals) were associated with more testing60,61 and risk of outbreaks.66 Even in a 4-month period, shifts may be possible in setting-specific population size.67 We could not estimate testing per capita or test positivity proportion among people using shelters given low sensitivity in identifying this population in the testing data.26 However, our data suggest that a minimum of 13.2% of people using shelters had been tested by May 20, 2020 (Appendix 3, Supplementary Figure 1C), suggesting that higher diagnoses per capita among people using shelters may be partially explained by increased testing. Work is underway to improve the sensitivity of algorithms to identify people experiencing homelessness.68 Our case-fatality estimates could be underestimated, as 4.3% of cases had an unknown outcome by the end of follow-up. Finally, test positivity and case-fatality proportions are limited to individuals with at least 1 test and thus may not generalize to those never tested, who may have lower test positivity and case-fatality proportions.69

Conclusion

Long-term care homes and shelters had disproportionate diagnosed cases per capita, and residents of long-term care homes diagnosed with COVID-19 had higher case fatality than the rest of the population. Heterogeneity across microepidemics signal the need for setting- and population-specific strategies in the next phase of the public health response in Canada, which could be guided by modelling the risks of onward transmission across each layer of heterogeneity and connections between networks.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Reported COVID-19 cases were obtained from the Public Health Ontario Integrated Public Health Information System (iPHIS) via the Ontario COVID-19 Modelling Consensus Table and with approval from the University of Toronto Health Sciences Research Ethics Board (protocol no. 39253). A subset of iPHIS data (confirmed cases only) were made available by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC) to the Ontario Modelling Consensus Table on a daily basis. Parts of this material are based on the OLIS data and information compiled and provided by MOHLTC and the Canadian Institute for Health Information. Marie-Claude Boily acknowledges joint centre funding from the UK Medical Research Council and Department for International Development. Sharmistha Mishra is supported by a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair in Mathematical Modeling and Program Science. Sharon Straus is supported by a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Knowledge Translation and Quality of Care. The analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are solely those of the authors and do not reflect those of the funding or data sources; no endorsement is intended or should be inferred.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Linwei Wang and Sharmistha Mishra conceptualized the study. Kristy Yiu, David Landsman and Linh Luong sourced literature and collated publicly available data; Huiting Ma, Andrew Calzavara and Linwei Wang performed data cleaning and analyses. Linwei Wang and Sharmistha Mishra drafted the manuscript. Huiting Ma, Kristy Yiu, David Landsman, Linh Luong, Andrew Calzavara, Adrienne Chan, Rafal Kustra, Jeffrey Kwong, Marie-Claude Boily, Stephen Hwang, Sharon Straus and Stefan Baral interpreted the data and revised the manuscript critically. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: The work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Foundation Grant (FN 13455), the Ontario Early Researcher Award (ER17-13-043), and the St. Michael’s Hospital Foundation Research Innovation Council’s 2020 COVID-19 Centre Research Award.

Data sharing: The de-identified data used for the current study are not publicly available but could be requested and accessed via the corresponding author, who would subsequently seek permission to share from the Ontario Ministry of Health via Ontario COVID-19 Modelling Consensus Table.

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/8/4/E627/suppl/DC1.

Disclaimer: This study was supported by ICES, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this article are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred.

References

- 1.COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. Worldometer; 2020. [accessed 2020 May 20]. Available: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Confirmed positive cases of COVID19 in Ontario. Toronto: Government of Ontario; 2020. [accessed 2020 May 20]. Available: https://data.ontario.ca/dataset/confirmed-positive-cases-of-covid-19-in-ontario/resource/455fd63b-603d-4608-8216-7d8647f43350. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Estimates of population (2016 Census and administrative data), by age group and sex for July 1st, Canada, provinces, territories, health regions (2018 boundaries) and peer groups. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2020. [accessed 2020 June 11]. Available: www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/cv.action?pid=1710013401#timeframe. [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacFadden DR, McGeer A, Athey T, et al. Use of genome sequencing to define institutional influenza outbreaks, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2014–15. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:492–7. doi: 10.3201/eid2403.171499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leclerc QJ, Fuller NM, Knight LE, et al. CMMID COVID-19 Working Group. What settings have been linked to SARS-CoV-2 transmission clusters? Wellcome Open Research. 2020;5:83. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15889.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pelley L. More than 80 Toronto health-care facilities, shelters experiencing COVID-19 outbreaks. CBC News. 2020. Apr 18, [accessed 2020 May 22]. Available: www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/more-than-80-toronto-health-care-facilities-shelters-experiencing-covid-19-outbreaks-1.5536867.

- 7.Bensadoun E. Nearly half of Canada’s COVID-19 deaths linked to long-term care facilities: Tam. Global News. 2020. Apr 13, [accessed 2020 May 22]. Available: https://globalnews.ca/news/6811726/coronavirus-long-term-care-deaths-canada.

- 8.NIA long term care COVID-19 tracker. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Long-Term Care; 2020. [accessed 2020 June 5]. Available: https://ltc-covid19-tracker.ca. [Google Scholar]

- 9.COVID-19: status of cases in Toronto. Toronto: City of Toronto; 2020. [accessed 2020 June 5]. Available: www.toronto.ca/home/covid-19/covid-19-latest-city-of-toronto-news/covid-19-status-of-cases-in-toronto. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee MH, Lee GA, Lee SH, et al. A systematic review on the causes of the transmission and control measures of outbreaks in long-term care facilities: back to basics of infection control. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0229911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levin-Rector A, Nivin B, Yeung A, et al. Building-level analyses to prospectively detect influenza outbreaks in long-term care facilities: New York City, 2013–2014. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43:839–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2015.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baggett TP, Keyes H, Sporn N, et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in residents of a large homeless shelter in Boston. JAMA. 2020;323:2191–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsai J, Wilson M. COVID-19: a potential public health problem for homeless populations. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e186–7. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30053-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Culhane DP, Treglia D, Steif K, et al. Estimated emergency and observational/quarantine capacity need for the US homeless population related to COVID-19 exposure by county; projected hospitalizations, intensive care units and mortality. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania; 2020. Apr 3, [accessed 2020 June 12]. Available: https://works.bepress.com/dennis_culhane/237. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lloyd-Smith JO, Schreiber SJ, Kopp PE, et al. Superspreading and the effect of individual variation on disease emergence. Nature. 2005;438:355–9. doi: 10.1038/nature04153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson D, Halperin DT. “Know your epidemic, know your response”: a useful approach, if we get it right. Lancet. 2008;372:423–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60883-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blanchard JF, Aral SO. Program Science: an initiative to improve the planning, implementation and evaluation of HIV/sexually transmitted infection prevention programmes. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87:2–3. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.047555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.COVID-19 update. Whitby (ON): Durham Region; 2020. [accessed 2020 May 21]. Available: www.durham.ca/en/health-and-wellness/novel-coronavirus-update.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 19.COVID-19 (2019 novel coronavirus) Oakville (ON): Halton Region; 2020. [accessed 2020 May 21]. Available: www.halton.ca/For-Residents/Immunizations-Preventable-Disease/Diseases-Infections/New-Coronavirus. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Novel coronavirus (COVID-19) Brampton (ON): Region of Peel; 2020. [accessed 2020 May 21]. Available: www.peelregion.ca/coronavirus. [Google Scholar]

- 21.COVID-19. Newmarket (ON): York Region; 2020. [accessed 2020 May 21]. Available: www.york.ca/wps/portal/yorkhome/health/yr/covid-19/covid19inyorkregion/01covid19inyorkregion/!ut/p/z1/tVXRcqIwFP2WffCRyU1AkzxmWSvQim5brebFYREhWwFLU61_v7GlD-20MDsWHkKSOTn33pM7J0iiBZJFtFdppFVZRFuzXsrByhcj3_MuIZg4zAUBExEQymDIMbp7ARDiDDzsQgDehIF_Qaf9X8zDcEmQbD4_RxLJXazWaEnshLKYM4tCP7acKB5YHP9Zm4Fv-pxvIm7wBh0XeqcztDxWq7gsdFLoHhzL6t4sHrXSTy8bWZknZkyirc56EJd7tbYwr2eYq-J0okpSU2YPAH-yXZfWkPupNPjiE1CfbwDINmllWwj5nmN0wxzw5wEVczwBx7drQMP1LE2S9Mssrgm626vkgGZFWeWmH27-87o8aIuAz4zQQm93Sk-hW3rSLf33iBP44GJxaj97aIMgvst-2gELw261D7vVPuxW-7Dbvp-fK07Q5k7mZSDV2B2nhjbSmaWKTYkWb0Zbzz446uJzozVU6u_DgxTG20-G_qzRomtzf5WPMld4YgRTuJ1R-D2kDhtcjadXZ7vSLp_lzD4q6_6aHW43WZqvxkO73_TbpkwbrPjxDzbwgmQ!/dz/d5/L2dBISEvZ0FBIS9nQSEh/#.XsqHoDpKhPY. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chung H, Fung K, Ferreira-Legere LE, et al. COVID-19 laboratory testing in Ontario: patterns of testing and characteristics of individuals tested, as of April 30, 2020. Toronto: ICES; 2020. [accessed 2020 May 22]. Available: www.ices.on.ca/Publications/Atlases-and-Reports/2020/COVID-19-Laboratory-Testing-in-Ontario. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Active COVID-19 outbreaks in Toronto shelters. Toronto: City of Toronto; 2020. [accessed 2020 May 22]. Available: www.toronto.ca/home/covid-19/covid-19-latest-city-of-toronto-news/covid-19-status-of-cases-in-toronto. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Active outbreaks in retirement homes and hospitals. Toronto: City of Toronto; 2020. [accessed 2020 June 11]. Available: www.toronto.ca/home/covid-19/covid-19-latest-city-of-toronto-news/covid-19-status-of-cases-in-toronto. [Google Scholar]

- 25.About ICES. Toronto: ICES; 2020. [accessed 2020 June 11]. Available: www.ices.on.ca/About-ICES. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richard L, Hwang SW, Forchuk C, et al. Validation study of health administrative data algorithms to identify individuals experiencing homelessness and estimate population prevalence of homelessness in Ontario, Canada. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e030221. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baines B. Long-term care homes legislation: lessons from Ontario. Toronto: Canadian Women’s Health Network; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halton region’s point in time count — 2018 dashboard. Oakville (ON): Halton Region; 2019. [accessed 2020 Sept. 25]. Available: https://www.homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/attachments/SS-03-19%20Attachment%20%234%20Point%20In%20Time%20Dashboard.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Homelessness in Halton (revised) Burlington (ON): Community Development Halton; 2019. [accessed 2020 Apr. 3]. Available: www.homelesshub.ca/CommunityProfiles. [Google Scholar]

- 30.I count: York Region’s 2018 homeless count. Newmarket (ON): York Region; 2019. [accessed 2020 June 11]. Available: www.homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/attachments/Working%2BTogether%2Bto%2BPrevent%2BReduce%2Band%2BEnd%2BHomelessness%2Bin%2BYork%2BRegion.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Everyone counts Peel: 2018 joint point-in-time count and registry week results. Mississauga (ON): Region of Peel, Peel Alliance to End Homelessness; 2019. [accessed 2020 June 11]. Available: www.homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/attachments/Final%20Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Durham 2018 pit count report. Ajax (ON): Community Development Council Durham, Durham Mental Health Services; 2019. [accessed 2020 June 11]. Available: www.homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/attachments/PROOF3_2018PIT_Report_CDCD-1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toronto street needs assessment 2018. Toronto: City of Toronto; 2018. [accessed 2020 May 22]. Available: www.toronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/99be-2018-SNA-Results-Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Emergency and transitional housing. Newmarket (ON): York Region; 2020. [accessed 2020 Apr. 3]. Available: www.york.ca/wps/portal/yorkhome/support/yr/housing/emergencyandtransitionalhousing/!ut/p/z0/hY7BDoIwEES_xQNHsw0xwrUhRkAJV-yFVKxQkW1pi8rfi2g86m3e7OzuAIMCGPKbrLmTCvl14gNblwndJnG8I2m-CiNCSU5TPwjJZh9ACux3YLogL33PKLBKoRMPB8Voylmj88ioTDuBddINs9GoTnjEDl. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Find a shelter — Region of Peel. Brampton (ON): Peel Region; 2020. [accessed 2020 Apr. 3]. Available: www.peelregion.ca/housing/shelters. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Epidemiologic summary: COVID-19 in Ontario — January 15, 2020 to May 17 2020. Toronto: Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario); 2020. [accessed 2020 Aug. 31]. Available: https://files.ontario.ca/moh-covid-19-report-en-2020-05-18.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 37.COVID-19 regional incidence and time to case notification in Ontario. Toronto: Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario); 2020. [accessed 2020 Aug. 31]. Available: www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/documents/ncov/epi/2020/covid-19-regional-epi-summary-report.pdf?la=en. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dowle M, Srinivasan A, Gorecki J, et al. Package ‘data.table’. 2020. [accessed 2020 Aug. 31]. Available: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/data.table/data.table.pdf.

- 39.Cameron AC, Trivedi PK. Regression analysis of count data. 2nd ed. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zeileis A, Kleiber C, Jackman S. Regression models for count data in R. J Stat Softw. 2008;27:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. London (UK): Chapman and Hall; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Relative risk calculator. New York: MEDCalc; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 43.R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, (Austria): R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kennedy B. Visits to long-term care homes and other facilities restricted due to COVID-19. The Toronto Star. 2020. Mar 14, [accessed 2020 May 22]. Available: www.thestar.com/news/gta/2020/03/14/visits-to-long-term-care-homes-and-other-facilities-restricted-due-to-covid-19.html.

- 45.Rocca R. Ban non-essential visits to long-term care homes during coronavirus pandemic: Ontario chief medical officer. Global News. 2020. Mar 14, [accessed 2020 May 22]. Available: https://globalnews.ca/news/6677922/coronavirus-ban-non-essential-visits-ontario-long-term-care-homes.

- 46.COVID-19 outbreak guidance for long-term care homes (LTCH) Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Health; 2020. [accessed 2020 May 22]. Available: www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/coronavirus/docs/LTCH_outbreak_guidance.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Toronto reports 2nd COVID-19-related death in its shelter system. CBC News. 2020. May 13, [accessed 2020 June 11]. Available: www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/covid-19-toronto-may-13-1.5567430.

- 48.Backgrounder: City of Toronto COVID-19 response for people experiencing homelessness. Toronto: City of Toronto; 2020. [accessed 2020 May 22]. Available: www.toronto.ca/home/media-room/backgrounders-other-resources/backgrounder-city-of-toronto-covid-19-response-for-people-experiencing-homelessness. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luo Y, Trevathan E, Qian Z, et al. Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection in household contacts of a healthcare provider, Wuhan, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1930–33. doi: 10.3201/eid2608.201016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pelley L. A healthcare worker got COVID-19 and survived — then lost her partner of 40 years to the illness. CBC News. 2020. Jun 8, [accessed 2020 Jun. 12]. Available: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/a-healthcare-worker-got-covid-19-and-survived-then-lost-her-partner-of-40-years-to-the-illness-1.5602216.

- 51.Soucy J-PR, Sturrock SL, Berry I, et al. Estimating the effect of physical distancing on the COVID-19 pandemic using an urban mobility index. medRxiv. 2020 Apr 4; doi: 10.1101/2020.04.05.20054288. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weeks C. Doctors say coronavirus test criteria are inconsistent, could lead to dangerous gaps. Globe and Mail [Toronto] 2020. Mar 12, [accessed 2020 Aug. 31]. Available: www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-doctors-say-coronavirus-test-criteria-is-inconsistent-could-lead-to.

- 53.Blackwell T. Canada among top world performers in testing for COVID-19, despite shortcomings. National Post [Toronto] 2020. Mar 17, [accessed 2020 Aug. 31]. Available: https://nationalpost.com/health/canada-among-top-world-performers-in-testing-for-covid-19-despite-shortcomings.

- 54.COVID-19 quick reference public health guidance on testing and clearance, version 3.0. Toronto: Ministry of Health, Government of Ontario; 2020. [accessed 2020 Aug. 31]. Available: https://fhs.mcmaster.ca/palliativecare/documents/OHCOVID-19QuickReferencePublicHealthGuidanceonTestingandClearance.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 55.COVID-19 provincial testing guidance update April 15, 2020, version 2.0. Toronto: Ministry of Health, Government of Ontario; 2020. [accessed 2020 Aug. 31]. Available: www.toronto.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/97ec-tph-moh-covid-19-testing-update-2020-04-15-Shared.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 56.COVID-19 provincial testing guidance update April 8, 2020. Toronto: Ministry of Health, Government of Ontario; 2020. [accessed 2020 Aug. 31]. Available: www.corhealthontario.ca/COVID-19-Testing-Guidance-Update-(2020-04-08).pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 57.D’Mello C. Ontario to begin ‘proactive’ testing for all long-term care residents one month into COVID-19 outbreak. CTV News. 2020. Apr 22, [accessed 2020 Aug. 31]. Available: https://toronto.ctvnews.ca/ontario-to-begin-proactive-testing-for-all-long-term-care-residents-one-month-into-covid-19-outbreak-1.4906755.

- 58.D’Mello C. Here’s the memo. Twitter. [accessed 2020 Aug. 31]. updated 2020 Apr 22. Available https://mobile.twitter.com/ColinDMello/status/1252966998579052548.

- 59.Farooqui S. Coronavirus: Doug Ford says anyone who wants a COVID-19 test in Ontario will be able to get one. Global News. 2020. May 24, [accessed 2020 June 11]. Available: https://globalnews.ca/news/6980167/coronavirus-ontario-testing-anyone-covid-19.

- 60.COVID-19 guidance for health sector: symptoms, screening, and testing resources. Toronto: Ministry of Health, Government of Ontario; 2020. [accessed 2020 Sept. 25]. Available: www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/coronavirus/2019_guidance.aspx#symptoms. [Google Scholar]

- 61.COVID-19 quick reference public health guidance on testing and clearance, version 7.0. Toronto: Ministry of Health, Government of Ontario; 2020. [accessed 2020 June 11]. Available: www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/coronavirus/2019_guidance.aspx#symptoms. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lai CC, Wang JH, Ko WC, et al. COVID-19 in long-term care facilities: an upcoming threat that cannot be ignored. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2020;53:444–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lower income people, new immigrants at higher COVID-19 risk in Toronto, data suggests. CBC News. 2020. May 12, [accessed 2020 June 11]. Available: www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/low-income-immigrants-covid-19-infection-1.5566384.

- 64.Toronto will start tracking race-based COVID-19 data, even if province won’t. CBC News. 2020. Apr 22, [accessed 2020 June 11]. Available: www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/toronto-covid-19-race-based-data-1.5540937.

- 65.Toronto pushing province to start collecting and sharing COVID-19 data around race and jobs. CBC News. 2020. Jun 2, [accessed 2020 Sept. 25]. Available: www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/toronto-race-based-data-ontario-1.5594715.

- 66.Yang J. Why COVID-19 outbreaks in hospitals are such a thorny issue. The Toronto Star. 2020. May 12, [accessed 2020 June 11]. Available: www.thestar.com/news/canada/2020/05/12/why-are-covid-19-outbreaks-in-hospitals-such-a-thorny-issue.html.

- 67.McGhie L, Barken R, Grenier A. Literature review: housing options for older homeless people. Hamilton (ON): Gilbrea Centre for Studies in Aging; 2013. [accessed 2020 June 12]. Available: https://aginghomelessness.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Literature-Review-Housing-Options-for-Older-Homeless-People.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Richard L, Ouedraogo AM, Shariff SZ. Identifying homelessness using health administrative data and postal codes. Toronto: Ontario Public Health; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Estimating mortality from COVID-19 [scientific brief] Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. Aug 4, [accessed 2020 Aug. 31]. Available: www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/estimating-mortality-from-covid-19. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.