Abstract

Carbonic anhydrase (CA) is a thoroughly studied enzyme. Its primary role is the rapid interconversion of carbon dioxide and bicarbonate in the cells, where carbon dioxide is produced, and in the lungs, where it is released from the blood. At the same time, it regulates pH homeostasis. The inhibitory function of sulfonamides on CA was discovered some 80 years ago. There are numerous physiological-therapeutic conditions in which inhibitors of carbonic anhydrase have a positive effect, such as glaucoma, or act as diuretics. With the realization that several isoenzymes of carbonic anhydrase are associated with the development of several types of cancer, such as brain and breast cancer, the development of inhibitor drugs specific to those enzyme forms has exploded. We would like to highlight the breadth of research on the enzyme as well as draw the attention to some problems in recent published work on inhibitor discovery.

Significance

The field of drug discovery against carbonic anhydrase has been extremely active for a number of years. The large number of human isoenzymes (isoforms) with different physiological roles has illustrated the need for development of specific inhibitors for the various isoenzymes. Numerous methods are needed to characterize the binding of inhibitors. However, one basic criterion, namely that an inhibitor should be able to reduce the enzyme activity to zero, has not always been proven, and these results need to be readdressed.

Introduction

The enzyme carbonic anhydrase (CA) was discovered in the 1930s (1). A detailed review of CA (2) describes the enzyme as an ideal subject for biophysical studies. CA is a zinc-containing enzyme that catalyzes the following reaction:

Seven different forms of the enzyme have been discovered in various species (3). These forms have different three-dimensional structures, but the enzyme mechanism is a case of convergent evolution in which the bound metal ion lowers the pKa of a water molecule to become a hydroxyl ion that can attack the carbon dioxide molecule bound in a hydrophobic pocket of the active site (4). Some forms of the enzyme are extremely active, working close to the rate of diffusion. Humans only carry the α-form, but there are 15 variants or isoenzymes (3). 12 of these are active enzymes found in various cellular contexts, in which some are membrane bound. The isoenzymes have different roles. Some human isoenzymes, particularly hCA IX and hCA XII, are associated with the development of cancer. Here, breast and brain cancer are noteworthy (5, 6, 7).

The first carbonic anhydrase inhibitors were discovered around 1940 (8), and a number of them have been used as clinical drugs for a long time (9). Most inhibitors have the R-SO2NH2 group, which binds to the Zn2+ ion in the active site. The development of specific inhibitors for the two isoenzymes mentioned is a current challenge.

Generally, enzymes are the targets in the development of drugs. Suitable enzyme inhibitors can be developed into drugs. In this analysis, it is important to understand the mode of inhibition and to determine accurately the inhibition strength. In this endeavor, there are a number of pitfalls that must be avoided (10,11). One basic criterion is especially noteworthy, namely that an inhibitor should be able to reduce the enzyme activity to zero, which has not always been demonstrated and, in particular in the results of the group of Claudiu T. Supuran, needs to be readdressed.

The catalytic mechanism of carbonic anhydrase

The catalytic mechanism of carbonic anhydrase has been characterized for the different forms of the enzyme. The extreme rate of the enzyme, with a kcat for hCA II of 106 s−1, is a challenge to comprehend (12). The metal ion, generally the zinc ion, is a central component of the active site. Furthermore, the pH profile of the activity, with an optimum around pH 7, suggests that a group titrating at that pH is involved (4). The identification of this group finally ended up on the zinc-bound water molecule, in which the zinc ion shifts its pKa to around 7 (4). X-ray (3,13) and neutron crystallography (14) have identified the binding mode of the zinc-bound water molecule, as well as those of bicarbonate and carbon dioxide. The hydrogen-bonding arrangement in the active site is such that the water or hydroxide ion donates a hydrogen bond to a proximal threonine (Thr199 in hCA II) because the hydroxyl group of this residue is forced to donate its hydrogen in a hydrogen bond to a negatively charged glutamate side chain (Glu106 in hCA II). Site-directed mutations have confirmed this model of the catalytic mechanism. The substrates/products carbon dioxide/bicarbonate are fairly weakly bound against a hydrophobic wall in the active site, which permits their rapid exchange. The rate-determining step is the transfer of the second proton of the zinc-bound water molecule to a histidine residue at the entrance of the active site (15).

Carbonic anhydrase as a nitrite reductase

The zinc ion in CA can be replaced by a number of other metals. When the zinc ion was exchanged for copper, two copper ions were bound (16,17). The new site was at the N-terminus. Furthermore, a diatomic molecule was bound to the copper ion in the classical metal site. The similarity in substrate structure between carbon dioxide and nitrite begged the question whether carbonic anhydrase also could be a nitrite reductase, which was found to be true (18). After some initial difficulties (19), it was found that Cu-hCA II indeed could reduce nitrite. Nitrite reductase is a copper enzyme with two metals bound, and Cu-hCA II not only binds the copper ions in a similar way but also performs the same reactions (20). With the high affinity for binding copper to the two sites in hCA II, a fraction of the enzyme in the blood must have two copper ions bound and thus be able to reduce nitrite (20).

Carbonic anhydrase inhibition

A wide range of compounds can inhibit the enzyme; among them are inorganic anions that normally replace the metal-bound water molecule (21). Already in 1940, it was found that sulfonamides inhibit the enzyme (8). Here, the NH2 group of the sulfonamide moiety binds to the metal. Gradually it became obvious that the sulfonamide group needs to be ionized to bind to the metal, and thus, a low pKa of the sulfonamide group is beneficial (3). It became obvious that the sulfonamide group functions as a transition state analog of the catalytic reaction (22). Hundreds of sulfonamides have been investigated for their capacity and specificity for the different hCA isoenzymes (9,22,23).

Inhibition constants

A classical enzyme inhibitor is able to reduce the enzyme activity to essentially zero. At the core of interest is the inhibition constant of the inhibitor (Ki). The Ki can be related to the IC50, which is the concentration of inhibitor that reduces the enzyme activity to half. The Cheng-Prusoff equation can be used for calculation of the inhibition constant Ki (24). However, IC50 is not always a good estimate of Ki.

Examples of proper enzymatic inhibition experiments and their presentation

Initially, we may need a reminder of how inhibition curves are presented in textbooks. Fig. 1 shows a theoretical case of a 1:1 binding competitive inhibitor inhibition curve.

Figure 1.

The binding of a competitive inhibitor to an enzyme ((25), Chapter 5).

As we see, at ∼100 times excess inhibitor relative to its IC50, less than 1% of enzymatic activity remains. Similarly, at 0.01 of IC50, the enzyme has around 99% of full activity. The curve should not change its slope substantially unless there are additional effects that make the inhibition mechanism more complex, which could be visualized through the Hill coefficient.

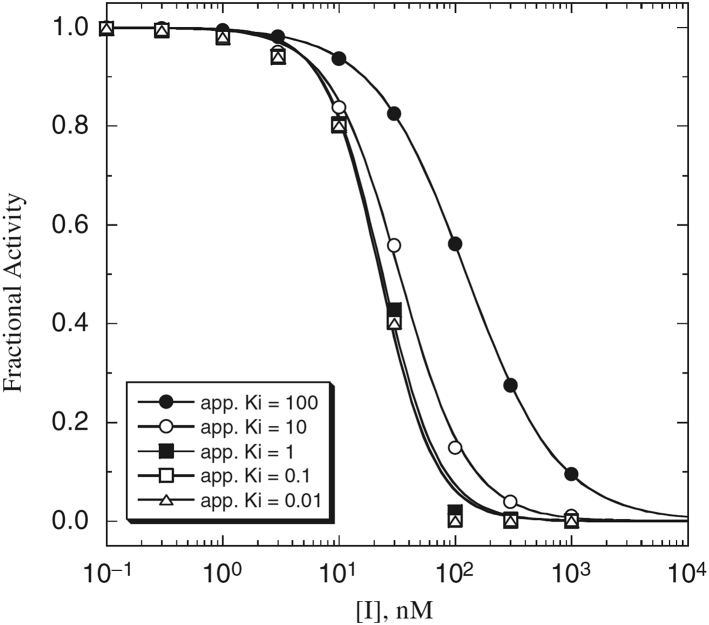

Fig. 2 shows the concentration-response plots for a series of increasingly tight binding inhibitors with apparent Ki-values ranging from 100 to 0.01 nM.

Figure 2.

Theoretical inhibition curves for inhibitors of various strengths at an enzyme concentration of 50 nM ((25), chapter 7).

As explained in (25), if the enzyme concentration is 50 nM, the measured IC50 is limited to 25 nM, and binding constants of tighter-binding inhibitors simply cannot be determined by this assay. The curves of inhibitors with 1-, 0.1-, and 0.01-nM Ki essentially overlap, and the resultant IC50 in every case is 25–26 nM. There is no possibility to measure 1- or 10-nM inhibitors, and particularly pM inhibitors, at this concentration of enzyme. The textbook explains in detail the relationship between IC50 and enzyme concentration [E]T (equation 7.12 in Chapter 7 of (25)): IC50 = Kiapp + 1/2[E]T. Using Morrison’s quadratic equation (26,27), it is possible to fit tight-binding inhibitor curves more accurately.

The hunt for isoenzyme-specific inhibitors

Often, the carbonic anhydrase inhibition constants Ki are calculated according to the Cheng-Prusoff equation (28, 29, 30). Here, Ki is determined from IC50, according to the equation Ki = IC50/(1 + S/KM). This equation is not valid under conditions when the enzyme concentration E > Ki (31). Thus, the calculation of Ki requires knowledge of the enzyme concentration, E, the KM-value, and the substrate concentration, S. In works by the group of Supuran (28, 29, 30), the enzyme concentrations are not published, and the substrate concentrations are only given as a range up to 17 mM. Thus, it is impossible to repeat the experiments and calculate the inhibition constants from the presented inhibition curves, and it is therefore also impossible to judge whether the conclusions drawn in these works are supported by the results.

The results from some inhibition studies are not compatible with the reported Ki-values. For example, in the supporting material of (28), the inhibition of CA II by the inhibitor number 12 is presented. The Ki is calculated to be 0.24 nM, close to the value of the IC50. This means that the total enzyme concentration (Etot) cannot be substantially higher than 2 × 0.24 nM = 0.5 nM. If one uses this value for Etot and uses the equation Ki = E × I/EI to calculate the amount of inhibition at an inhibitor concentration that is 100 × Ki (24 nM), one finds that the inhibition should be ∼99% and the remaining activity 1%. However the figure shows a remaining activity of ∼24% at this concentration. Such large deviations are found in much of the presented data. For example, in (32) (Fig. 3), the activity after inhibition of CA IX and CA XII by various inhibitors never goes below 40% at a 10−6 M inhibitor concentration, even though the Ki-values are claimed to be in the nM range. The same problem is also seen in (29,30).

Figure 3.

Typical inhibition curves from (32), using compound 10 and carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes II and XII.

Data on the inhibition of hCA IX and hCA XII (the anticancer targets) by coumarins have been reported in several publications. In Table 1 of (32), it appears that all listed compounds 1–13 have rather good selectivity toward hCA IX and hCA XII, whereas they only weakly inhibit hCA I and hCA II. The inhibition curves for compound 10 for hCA II and hCA XII are provided in the supporting material of (32).

The two curves have similar shapes, but the first of them never crosses 50% inhibition, whereas the second curve does. The authors judge that hCA XII is inhibited but hCA II is not! There are a number of problems with these curves:

-

1.

At high concentration of inhibitor, there is significant remaining enzyme activity (43% at 1 μM compound 10 for hCA XII).

-

2.

There is significant inhibition of hCA II by compound 10, with only 59% activity remaining at 10 nM added compound, so it is incorrect to claim that the compound does not inhibit hCA II.

-

3.

The overall shape of the curves is strange. There should be 90–100% enzyme activity at compound concentrations significantly below the IC50 and 0–10% enzyme activity remaining at concentrations significantly exceeding the IC50. However, the shape of the curves is nearly horizontal. In the limited number of publications by the group in which inhibition curves are provided, the shapes are very similar. This shape of the curves suggests that the assay used has problems and that the Ki-values are not correctly determined or reliable.

Several manuscripts list both the IC50 and the Ki of the inhibitors (33,34). Table 2 of (33) lists the IC50 of compound 1 for hCA I as 53.4 nM and the Ki as 77.8 nM. Ki is calculated from IC50 using the Cheng-Prusoff equation Ki = IC50/(1 + S/Km). Here, Ki is obtained by dividing IC50 by one or by a number larger than one. Therefore, it is impossible that the value of Ki is greater than IC50, as is the case for three compounds in this publication (1, 2, and 5).

The situation is similar in Table 2 in (34). We assume that IC50-values are on the left and Ki-values are on the right, as in the previously analyzed table. For acetazolamide inhibition of hCA I, as well as inhibition of hCA II, the Ki-values are greater than the IC50. For all numbered compounds, the inhibition of hCA I is possible, but for hCA II, the Ki-values are greater than the IC50-values for compounds 3, 4, 5, and 8, which is not possible. All the values in this table are in pM. Thus, the inhibition is in the subnanomolar range. Thus, the IC50-values must have been determined at extremely low enzyme concentrations, 0.2–0.4 nM, which seems unlikely. Furthermore, the Ki-values of acetazolamide inhibition of hCA I and hCA II are previously published and are different from 1.0665 to 1.1545 nM as listed here. The Ki-values reported elsewhere in the literature are considerably higher, 250.0 nM for hCA I and 12.5 nM for hCA II (35). Similar values have been previously reported numerous times. Therefore, the data in (33,34) seem unreliable. Unfortunately, no original measurements are provided; thus, there is no possibility for a closer analysis.

In the supporting material of (36), the concentration of the CA IX enzyme used in the assay is equal to 10−7 M (stated in red at the top of the figure). One curve shows the remaining activity of the enzyme upon addition of inhibitor 17a. Upon addition of 10−9 M of inhibitor, 16% of the enzyme activity is inhibited. No matter how strong the inhibitor is, it could only inhibit 1% of the enzyme molecules because one inhibitor molecule cannot inhibit multiple molecules of the enzyme. Addition of 10−8 M inhibitor could inhibit at most 10% of the enzyme, but the figure shows an inhibition of 42%. Table 1 in (36) lists the Ki of compound 17a toward CA IX as 45.1 nM, which corresponds roughly to the position of the midpoint in the corresponding curve and most likely should be the IC50 of this inhibition. The Ki should have been lower after the application of the Cheng-Prusoff equation. Furthermore, with a Ki of 45.1 nM, the remaining CA IX activity should not be 19% at 1.0 μM added inhibitor 17a.

In (28), compound 12 has an extremely low Ki toward carbonic anhydrases. The listed Ki-values are 0.63 nM for hCA I, 0.24 nM for hCA II, 0.38 nM for hCA VII, and 0.13 nM for hCA IX. The enzyme concentrations in these assays are not provided in the manuscript, and therefore it is impossible to repeat this experiment. However, if we consider the enzyme concentrations to be around 10−7 M, as in the previous manuscript (36), the whole design of the inhibition experiment with a concentration of inhibitor 12 beginning at 10−10 does not make sense because only 0.1% of the enzyme activity could be inhibited. Such low inhibitor concentrations could only be used as controls. However, the graphs show that 52–56% of enzyme activity remains upon addition at this low concentration of compound 12. Again, we have the impossible situation of one molecule of inhibitor acting on nearly 500 molecules of enzyme.

Furthermore, as stated above, addition of the largest concentrations of the inhibitor, 10−7 and 10−6 M, did not reduce the enzyme activity to zero, but 19–31% of activity remains. The Ki of inhibitor 12 can definitely not be in the subnanomolar range as stated.

Discussion

The group of Supuran has published an enormous number of works on various inhibitors, in which numerous groups of organic synthesis chemists have synthesized a large number of compounds and provided them for inhibition analysis by the group. The data are often provided in tables, in which important information and the original measurements are lacking. Furthermore, many measurements have been performed incorrectly. Thus, there is no proof that these inhibitors are actually as good as claimed. In the few studies in which more extensive data on enzyme inhibition are provided, the inhibition curves do not show normal inhibition, but comments are lacking.

A drug candidate, SLC-0111, has entered clinical trials. From our analysis above, it is doubtful whether the compound has the required Ki to be advanced into clinical trials (37). There are no proper data in the work to promote the compounds, even into preclinical testing (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/record/NCT02215850). Through incorrect inhibitor studies, the commercial interests of pharmaceutical companies, as well as the interests of patients, may be hurt.

In summary, much of the published work on CA inhibitors requires careful attention to the following considerations:

-

1.

An inhibitor of an enzyme should at some concentration abolish the enzyme activity almost completely.

-

2.

A low-molecular-weight inhibitor cannot inhibit more than one enzyme molecule.

-

3.

The inhibition by a strongly binding inhibitor has to be measured at a correspondingly low enzyme concentration.

-

4.

In the calculation of the Ki from an estimated IC50, the numeric value of the Ki must be smaller than the IC50.

-

5.

In a scientific work, the primary data should be provided in the main manuscript or the supplement so that the experiments can be reproduced and the calculations can be checked.

The main emphasis of the studies we have discussed concerns the identification of new inhibitors of carbonic anhydrase. First, the method to measure the inhibition has severe problems. If the enzyme still is active at an inhibitor concentration 100 times the estimated Ki, something is wrong. Furthermore, with the incomplete data provided, the measurements cannot be analyzed or repeated. Likewise, several of the early crystallographic investigations are poorly performed and cannot be trusted. The authors should provide the missing information in supplements and corrections and include discussions of the strange inhibition mechanisms.

Conclusion

It is obvious that carbonic anhydrase will be in focus for a long time for an improved understanding of its physiological role in two different enzymatic activities. The development of inhibitors of specific isoenzyme will have to go through careful continued investigations by different methods to provide diagnostic tools and therapeutic possibilities against severe conditions.

Author Contributions

The authors have contributed equally to the production of the article.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Derek Logan, Lund University (Lund, Sweden) has kindly revised the language and suggested some improvements of the text. The illustrations are reproduced with kind permission by Copyright Clearance Center.

Editor: Meyer Jackson.

References

- 1.Meldrum N.U., Roughton F.J. Some properties of carbonic anhydrase, the CO2 enzyme present in blood. J. Physiol. 1932;75:15P–16P. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krishnamurthy V.M., Kaufman G.K., Whitesides G.M. Carbonic anhydrase as a model for biophysical and physical-organic studies of proteins and protein-ligand binding. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:946–1051. doi: 10.1021/cr050262p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lomelino C.L., Andring J.T., McKenna R. Crystallography and its impact on carbonic anhydrase research. Int. J. Med. Chem. 2018;2018:9419521. doi: 10.1155/2018/9419521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silverman D.N., Lindskog S. The catalytic mechanism of carbonic anhydrase: implications of a rate limiting protolysis of water. Acc. Chem. Res. 1988;21:30–36. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pastorekova S., Kopacek J., Pastorek J. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and the management of cancer. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2007;7:865–878. doi: 10.2174/156802607780636708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pastorekova S., Zatovicova M., Pastorek J. Cancer-associated carbonic anhydrases and their inhibition. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2008;14:685–698. doi: 10.2174/138161208783877893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haapasalo J., Nordfors K., Parkkila S. The expression of carbonic anhydrases II, IX and XII in brain tumors. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:1723. doi: 10.3390/cancers12071723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mann T., Keilin D. Sulphanilamide as a specific inhibitor of carbonic anhydrase. Nature. 1940;146:164–165. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matulis D., editor. Carbonic Anhydrase as Drug Target: Thermodynamics and Structure of Inhibitor Binding. Springer Verlag; Berlin, Germany: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramsay R.R., Tipton K.F. Assessment of enzyme inhibition: a review with examples from the development of monoamine oxidase and cholinesterase inhibitory drugs. Molecules. 2017;22:1–46. doi: 10.3390/molecules22071192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holdgate G.A., Meek T.D., Grimley R.L. Mechanistic enzymology in drug discovery: a fresh perspective. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018;17:115–132. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khalifah R.G. The carbon dioxide hydration activity of carbonic anhydrase. I. Stop-flow kinetic studies on the native human isoenzymes B and C. J. Biol. Chem. 1971;246:2561–2573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liljas A., Kannan K.K., Petef M. Crystal structure of human carbonic anhydrase C. Nat. New Biol. 1972;235:131–137. doi: 10.1038/newbio235131a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisher Z., Kovalevsky A.Y., Langan P. Neutron structure of human carbonic anhydrase II: a hydrogen-bonded water network “switch” is observed between pH 7.8 and 10.0. Biochemistry. 2011;50:9421–9423. doi: 10.1021/bi201487b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tu C.K., Silverman D.N., Lindskog S. Role of histidine 64 in the catalytic mechanism of human carbonic anhydrase II studied with a site-specific mutant. Biochemistry. 1989;28:7913–7918. doi: 10.1021/bi00445a054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Håkansson K., Wehnert A., Liljas A. X-ray analysis of metal-substituted human carbonic anhydrase II derivatives. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1994;50:93–100. doi: 10.1107/S0907444993008790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferraroni M., Gaspari R., Supuran C.T. Dioxygen, an unexpected carbonic anhydrase ligand. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2018;33:999–1005. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2018.1475371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aamand R., Dalsgaard T., Fago A. Generation of nitric oxide from nitrite by carbonic anhydrase: a possible link between metabolic activity and vasodilation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2009;297:H2068–H2074. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00525.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andring J.T., Lomelino C.L., Swenson E.R. Carbonic anhydrase II does not exhibit Nitrite reductase or Nitrous Anhydrase Activity. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2018;117:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andring J.T., Kim C.U., McKenna R. Structure and mechanism of copper-carbonic anhydrase II: a nitrite reductase. IUCrJ. 2020;7:287–293. doi: 10.1107/S2052252520000986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liljas A., Håkansson K., Xue Y. Inhibition and catalysis of carbonic anhydrase. Recent crystallographic analyses. Eur. J. Biochem. 1994;219:1–10. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-79502-2_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linkuvienė V., Zubrienė A., Matulis D. Thermodynamic, kinetic, and structural parameterization of human carbonic anhydrase interactions toward enhanced inhibitor design. Quart. Rev. Biophys. 2018;51:1–176. doi: 10.1017/S0033583518000082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKenna R., Supuran C.T. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors drug design. In: Frost S.C., McKenna R., editors. Carbonic Anhydrase: Mechanism, Regulation, Links to Disease & Industrial Applications. Springer Nature; 2014. pp. 291–323. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng Y., Prusoff W.H. Relationship between the inhibition constant (KI) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1973;22:3099–3108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Copeland R.A. Wiley-Interscience; Hoboken, NJ: 2005. Evaluation of enzyme inhibitors in drug discovery: A guide for medicinal chemists and pharmacologists. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morrison J.F. Kinetics of the reversible inhibition of enzyme-catalysed reactions by tight-binding inhibitors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1969;185:269–286. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(69)90420-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams J.W., Morrison J.F. The kinetics of reversible tight-binding inhibition. Methods Enzymol. 1979;63:437–467. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(79)63019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bozdag M., Ferraroni M., Supuran C.T. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors based on sorafenib scaffold: design, synthesis, crystallographic investigation and effects on primary breast cancer cells. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019;182:111600. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fragai M., Comito G., Nativi C. Lipoyl-homotaurine derivative (ADM_12) reverts oxaliplatin-induced neuropathy and reduces cancer cells malignancy by inhibiting carbonic anhydrase IX (CAIX) J. Med. Chem. 2017;60:9003–9011. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zengin Kurt B., Sonmez F., Supuran C.T. Synthesis of coumarin-sulfonamide derivatives and determination of their cytotoxicity, carbonic anhydrase inhibitory and molecular docking studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019;183:111702. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cha S. Tight-binding inhibitors-I. Kinetic behavior. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1975;24:2177–2185. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(75)90050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.De Luca L., Mancuso F., Gitto R. Inhibitory effects and structural insights for a novel series of coumarin-based compounds that selectively target human CA IX and CA XII carbonic anhydrases. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018;143:276–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tugrak M., Gul H.I., Supuran C.T. Synthesis and biological evaluation of some new mono Mannich bases with piperazines as possible anticancer agents and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 2019;90:103095. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.103095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gul H.I., Tugrak M., Supuran C.T. New phenolic Mannich bases with piperazines and their bioactivities. Bioorg. Chem. 2019;90:103057. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.103057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Said M.A., Eldehna W.M., Supuran C.T. Synthesis, biological and molecular dynamics investigations with a series of triazolopyrimidine/triazole-based benzenesulfonamides as novel carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020;185:111843. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moi D., Nocentini A., Onnis V. Structure-activity relationship with pyrazoline-based aromatic sulfamates as carbonic anhydrase isoforms I, II, IX and XII inhibitors: synthesis and biological evaluation. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019;182:111638. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abo-Ashour M.F., Eldehna W.M., Supuran C.T. Novel synthesized SLC-0111 thiazole and thiadiazole analogues: determination of their carbonic anhydrase inhibitory activity and molecular modeling studies. Bioorg. Chem. 2019;87:794–802. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]