Abstract

Cell durotaxis is an essential process in tissue development. Although the role of cytoskeleton in cell durotaxis has been widely studied, whether cell volume and membrane tension are implicated in cell durotaxis remains unclear. By quantifying the volume distribution during cell durotaxis, we show that the volume of 3T3 fibroblast cells decreases by almost 40% as cells migrate toward stiffer regions of gradient gels. Inhibiting ion transporters that can reduce the amplitude of cell volume decrease significantly suppresses cell durotaxis. However, from the correlation analysis, we find that durotaxis index does not correlate with the cell volume decrease. It scales with the membrane tension difference in the direction of stiffness gradient. Because of the tight coupling between cell volume and membrane tension, inhibition of Na+/K+ ATPase and Na+/H+ exchanger results in smaller volume decrease and membrane tension difference. Collectively, our findings indicate that the polarization of membrane tension is a central regulator of cell durotaxis, and Na+/K+ ATPase and Na+/H+ exchanger can help to maintain the membrane tension polarity.

Significance

Recent studies have shown that cells prefer to migrate toward stiffer regions on substrates with a stiffness gradient, which is termed as durotaxis. Here, we show that cell durotaxis is accompanied by a remarkable cell volume decrease. Because of the coupling between cell volume and membrane tension, this result may imply a critical role of membrane tension in cell durotaxis. We find that the durotaxis index scales with the membrane tension difference in the direction of stiffness gradient. Furthermore, the inhibition of Na+/K+ ATPase and Na+/H+ exchanger leads to smaller volume shrinkage and membrane tension difference.

Introduction

Directional cell migration is essential for various cell functions such as tissue development (1), wound healing (2), cancer invasion (3), and angiogenesis (4). Many experiments have shown that directional cell migration can result from gradients of chemotactic factors (chemotaxis) (5,6), ligand density (haptotaxis) (7,8), or substrate stiffness (durotaxis) (9, 10, 11). Although the main players involved in chemotaxis and haptotaxis have been identified, little is known about the mechanisms of cell durotaxis. Recent studies indicate that both the migration speed and durotaxis index (the ratio of displacement in the direction of stiffness gradient to the total path length) increase with the stiffness gradient (10,12). Vascular smooth muscle cells undergo durotaxis on gradient gels coated with fibronectin, but not on those coated with laminin (11). But how cells decide their migration direction toward stiffer regions remains a puzzling problem.

The polarization of cytoskeleton compositions is implicated in cell durotaxis. Microtubules (MTs) and actin accumulate at the cell front (13,14), whereas myosin accumulates at the cell rear (15). These polarizations may lead to a bigger traction force on the stiffer side of gradient substrate (16,17), which then facilitates the biased migration toward the region with higher modulus. It has been shown that membrane tension plays a critical role in maintaining cell polarization (18). Thus, membrane tension may also have significant effect on cell durotaxis. Furthermore, experiments have shown that cell volume is significantly smaller on stiffer substrates (19,20), and the change in cell volume can provide a driving force for cell migration (21,22). Because of the tight coupling between membrane tension and cell volume (23,24), the change in cell volume is accompanied by the variation of membrane tension. These findings imply that if cell durotaxis relates to membrane tension, it may also relate to cell volume. However, whether cell durotaxis directly correlates with cell volume or membrane tension is still unclear.

To address these questions, we first study the migration trajectories and the volume distribution of 3T3 cells on polyacrylamide (PA) gels with a stiffness gradient. We find that cells prefer to migrate toward the stiffer region of gradient gels, and cell durotaxis is accompanied by a dramatic decrease in cell volume. We then treat cells with various drugs to disturb the transmembrane transports of ions and water to identify the roles of these elements in cell durotaxis. Among these inhibitions, only those that reduce the amplitude of volume shrinkage can lead to a decrease in durotaxis index. However, the durotaxis index does not show a strong correlation with the cell volume decrease. Given that cell volume and membrane tension are tightly coupled together (23,24), we also use various drugs to disturb the membrane tension and analyze the correlation between durotaxis index and membrane tension. We find that migration speed scales with the front-to-rear membrane tension difference in the direction of cell migration, whereas the durotaxis index scales with the stiff-to-soft membrane tension difference in the direction of stiffness gradient. Inhibition of Na+/K+ ATPase, Na+/H+ exchanger, myosin contractility, and MTs all results in smaller membrane tension differences in the direction of stiffness gradient. Together, our findings indicate that the polarization of membrane tension is a central regulator of cell durotaxis. Na+/K+ ATPase, Na+/H+ exchanger, myosin contractility, and MTs work jointly together to maintain the polarization of membrane tension.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

3T3 mouse fibroblasts cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD and Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), supplemented with (vol/vol) fetal calf serum (Gibco and Life Technologies) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco and Life Technologies), at 37°C and 5% CO2 in humid conditions. Cells were treated with 2 μM thymidine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) medium at least 18 h to block cells in G1/S transition. After this synchronization, cells were trypsinized with trypsin-EDTA (Gibco and Life Technologies), centrifugated at 1000 rpm/min for 3 min, and seeded on polyacrylamide substrate at low density (∼7–10 × 103 cells/cm2) to reduce cell-cell interaction.

Fabrications of gradient polyacrylamide gels

Polyacrylamide gels with a stiffness gradient were prepared with a microfluidic device (11). Briefly, 200 μL of 0.1 mM NaOH solution was added to cover the surface of a 20-mm-diameter glass dish (NEST, catalog no. 801001; Wuxi, China), and the glass dish was then heated at 80°C for 30 min. After removing the remainder of the NaOH solution, the glass dish was washed three times with sterile water. After drying, the dish was treated with octadecyl trichlorosilane (catalog no. 104817; Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h to form a hydrophobic barrier. A polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) mold with a dumbbell-shaped pattern was covered on the dish. Then, the pattern region was washed carefully with NaOH solution to break hydrophobicity. The dish covered with PDMS mold was treated with plasma cleaner (PDC-002; Harrick, Pleasantville, NY) for 30 s (Fig. S1 A) to create a hydrophilic dumbbell-shaped pattern region on the dish (Fig. S1 B). The glass dish and a glass coverslip coated with dichlorodimethylsilane (catalog no. 40136; Sigma-Aldrich) were stacked together with 150-μm spacers (Fig. S1 C). Two kinds of polyacrylamide solutions with different acrylamide/bis-acrylamide ratios were injected into each end of the dumbbell until the solutions made contact with each other in the middle of the “bar” region (Fig. S1 D). Specifically, the polyacrylamide solution that was injected in the “soft region” of the dumbbell-shaped pattern consisted of 4% acrylamide (Sangon Biotech, Shanghai, China), 0.1% bis-acrylamide (Sangon Biotech), 0.12% ammonium persulfate (catalog no. A3678; Sigma-Aldrich), and 0.12% N,N,N,N-tetramethylethylenediamine (catalog no. T9281; Sigma-Aldrich). The polyacrylamide solution that was injected in the “hard region” of the dumbbell-shaped pattern consisted of 12% acrylamide, 0.6% bis-acrylamide, 0.1% ammonium persulfate, and 0.1% N,N,N,N-tetramethylethylenediamine. The polymerization was completed in 10 min (Fig. S1 E), and then the coverslip was peeled off slowly (Fig. S1 F).

Mechanical characterization of substrate stiffness

The elastic module of polyacrylamide gels was characterized with nanoindentations using atomic force microscopy (AFM; Bruker, resolve). A 20-μm-diameter silica bead was stuck to the tip of an NP-O10-C probe with epoxy glue. Polyacrylamide gels were indented with a rate of 1 μm/s and an indentation depth of 1.5 μm in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution. To calculate the module of PA gels, we fitted force versus indentation depth data to a linearized Hertz model (10,11). The elastic modulus of gel is given as

| (1) |

where E is the elastic modulus, F is the indentation force, ν is the Poisson ratio of gels, R is the radius of the indenter, and δ is the indentation depth. We set the Poisson ratios of PA gels as 0.48.

Measurement of membrane tension

The membrane tension can be estimated from the AFM force-position (f-z) curves close to the contact point (25), and the membrane tension γ was given as

where F∗ and δ∗ are the differences of indentation force and piezo position between the contact point and the inflection point (Fig. S2). We used the MLCT-BIO-D probe (0.03 N/m, front angle 35°, back angle 35°, side angle 35°) to press cellular lamellipodia. The indentation rate was 50 nm/s, and the indentation depth was 20 nm.

It should be noted that for the correlation analysis in Fig. 4, C–F, the data of cell migration and the data of membrane tension were not acquired from the same experimental group. We first quantified the migration speed and durotaxis index with various treatments and then carried out other experiments with other groups with the same treatments to quantify membrane tension.

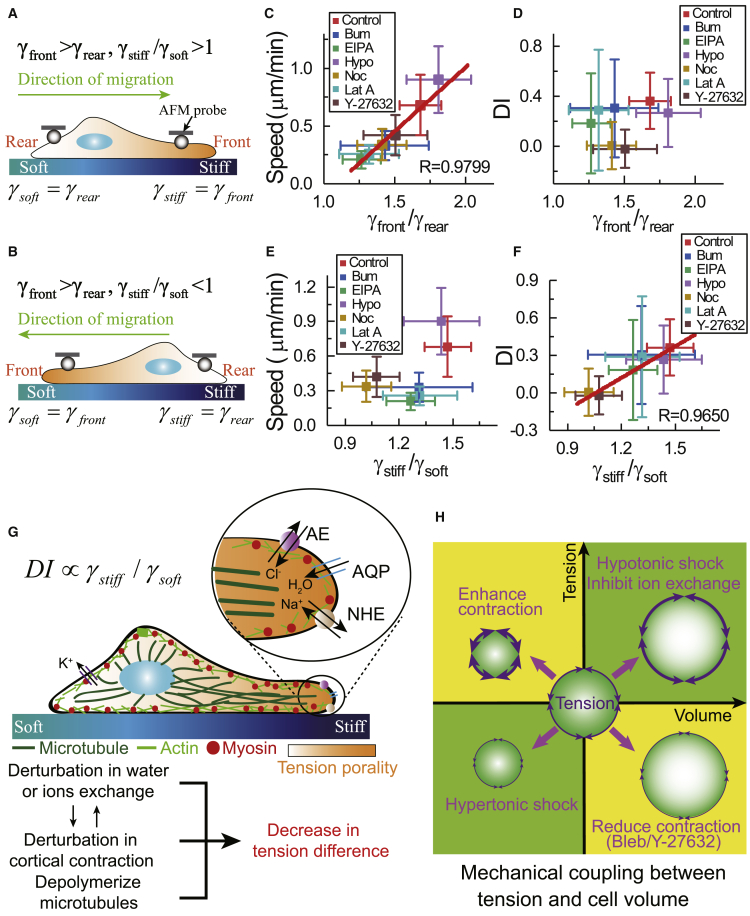

Figure 4.

Durotaxis index correlates with the polarity of membrane tension in the direction of stiffness gradient. (A and B) Definitions of local membrane tensions are given. γfront and γrear are the membrane tensions at cell front and cell rear, respectively. γstiff and γsoft are the membrane tensions on the stiffer side and softer side of substrate, respectively. (A) If cells migrate toward stiffer regions, the substrate stiffness at the cell front is bigger than that at cell rear; thus, γstiff = γfront and γsoft = γrear. (B) If cells migrate toward softer regions, γsoft = γfront and γstiff = γrear. (C and D) Migration speed and DI are shown as functions of γfront/γrear. (E and F) Migration speed and DI are shown as functions of γstiff/γsoft. Each point represents a set of data for the inhibition experiments, and the red lines are linear fittings. n = ∼7–18. Error bars are mean ± SD. (G) A schematic illustration of the proposed mechanism for cell durotaxis is given. The directional migration of cell closely correlates with the membrane tension difference between lamellipodia on the stiffer side and the softer side of substrate. The disturbances of the exchanges of ions and water, the disturbances of cortical contraction, and the depolymerization of microtubules can reduce the membrane tension difference and then impair cell durotaxis. (H) Mechanical coupling between cell volume and membrane tension is shown. To see this figure in color, go online.

Substrate functionalization

PA gels were functionalized with fibronectin. First, we covered the surfaces of gels with 0.35 mg/mL sufosuccinimidyl-6-(4’-azido-2’-nitrophenylamino)-hexanoate (sulfo-SANPAH) (catalog no. 803332; Sigma-Aldrich), and then the gels were exposed to 365 nm ultraviolet light for 15 min. Then, the gels were washed three times with 50 mM HEPES in PBS to remove unbound sulfo-SANPAH. PA gels were then incubated with 20 μg/mL fibronectin solution (catalog no. 33016015; Gibco) for 4 h at 37°C.

Quantification of cell motility

Cells were loaded with 1 μg/mL 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich) for 12 h and then washed three times with PBS for 5 min. An incubator chamber (TOKAI HIT, Shizuoka, Japan) was used to control the temperature, CO2 concentration, and humidity when cells were imaging. To reduce phototoxicity, the intensity of fluorescent light was set to the lowest level, and the exposure time of CCD was set as 50 ms. Cells were imaged in 15-min intervals for 10 h using an inverted fluorescence microscope (DMi8; Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with a ×20 air objective (NA = 0.8).

Cells were located by tracing the nucleus position with ImageJ. The complete trajectory of cell migration can obtain by connecting the nucleus position at each time frame. The migration speed of cell, v, was calculated by dividing the length of cell migration trajectory, L, by the whole migration time (Fig. 1 C). The durotaxis index (DI) was calculated by dividing the migration distance in the direction of the stiffness gradient, Sx, by the total path length of the cell L (Fig. 1 C). For cells that migrate on gradient gels, the migration angle, θ, was defined as the angle between the direction of the stiffness gradient and the line connecting the original and the final positions of cells (Fig. 1 C). For cells that migrate on uniform gels, the migration angle, θ, was defined as the angle between the x axis and the line connecting the original and the final positions of cells.

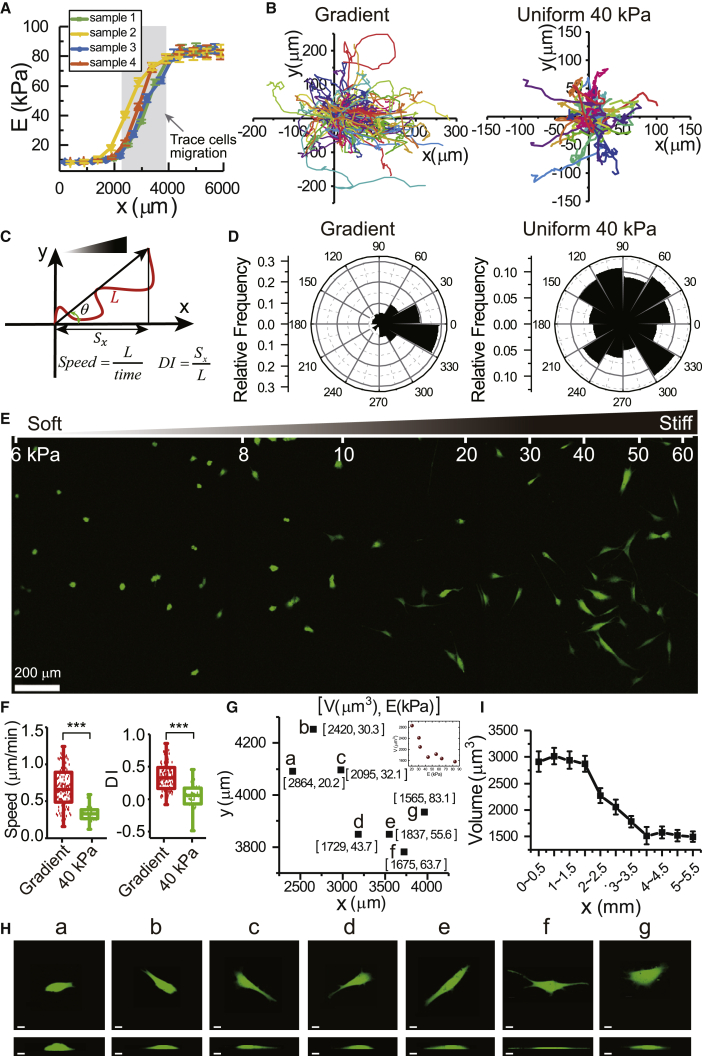

Figure 1.

Cells migrate toward the stiffer region on gradient gels and show a dramatic decrease in cell volume. (A) The elastic modulus of gels is shown as a function of the position along the gradient. Gray shadow indicates the region of data acquisition for cell migration. (B) Migration trajectories of 3T3 cells on gradient gels (left, n = 108) and uniform 40 kPa gels (right, n = 41) are shown. (C) Schematic of a cell trajectory (red line) and variables (migration speed, durotaxis index (DI), and migration angle θ) used to characterize migratory phenotypes are given. (D) Rose plots of migration angles are shown. (E) The distribution and morphologies of 3T3 cells on gradient PA gel are shown. (F) Box plots of average migration speed (left) and DI (right) are given. Box plots show median line and 25th and 75th percentiles, and whiskers extend to the maximal and minimal data points. ∗∗∗p < 0.001. (G) The distributions of cell volume and substrate stiffness on gradient gels are shown; V indicates cell volume and E indicates local substrate stiffness. Inset shows the plot of V vs. E. (H) Morphologies of 3T3 cells corresponding to the data in (G) are shown. Scale bars, 10 μm. (I) Cell volume is shown as a function of the position along the gradient, n = 6–10. Error bars are mean ± standard deviation (SD). To see this figure in color, go online.

Volume measurement

The measurement of cell volume was based on our previous work (20). Cells were loaded with a fluorescent indicator Cell Tracker Green 5-chloromethylgluorescein diacetate (CMFDA) and incubated with 20 μL/mL CMFDA for ∼20–30 min at 37°C. Then, cells were washed with PBS for three times before imaging. Cells were imaged by a laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica; SP8) equipped with a ×40 water immersion objective (NA = 1.1). The CMFDA dye was excited by a 488 nm laser, and its emission was detected in the band from 510 to 530 nm. The three-dimensional (3D) cell morphologies were reconstructed from the confocal images by stacking the xy-plane images through the whole height of cells. Then, the cell volume was calculated from the reconstructed cell morphology.

Drug treatments and osmotic shocks

The blebbistatin (myosin-II inhibitor; Sigma-Aldrich), Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor; Sigma-Aldrich), latrunculin A (F-actin polymerization inhibitor; Sigma-Aldrich), cytochalasin D (actin polymerization inhibitor; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), nocodazole (MT polymerization inhibitor; Sigma-Aldrich), bumetanide (Bum) (K+Na+/2 Cl− cotransporter inhibitor; Abcam), 4,4 diisothiocyanatostillbene 2,2′-disulfonic acid disodium salt hydrate (DIDS) (Cl− channel blocker; Sigma-Aldrich), ouabain (Oua) (Na+/K+ ATPase inhibitor; Sigma-Aldrich), ethylisopropylamiloride (EIPA) (Na+/H+ exchanger inhibitor; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), and GsMTx4 (mechanosensitive ion channel inhibitor; R&D Systems) were dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) solution to a desired concentration. Cells were incubated with these inhibitors for 1 h before imaging. For osmotic shock experiments, cell medium was premixed with PEG200 (Sigma-Aldrich) or sterile water to get the hypertonic or hypotonic solution.

Results

3T3 cells prefer to migrate toward stiffer region

PA hydrogel is widely used as a cell culture substrate in vitro (26). The stiffness of PA gel is determined by the concentrations of acrylamide monomer and cross-linker. Following (11), we use a microfluidic device to fabricate PA gels with stiffness gradient. We first create a dumbbell-shaped hydrophilic pattern on glass dishes with plasma treatment (Fig. S1, A and B). After stacking a coverslip over the glass dish (Fig. S1 C), we inject 12% acrylamide and 0.6% bis-acrylamide solution into one side of the pattern and 4% acrylamide and 0.1% bis-acrylamide solution on the other side (Fig. S1 D). The “bar” region of the dumbbell acts as a mixing region for the solution (Fig. S1 E). To measure the stiffness of PA gels, nanoindentation is performed with AFM. For convenience of description, we define the end of the “bar” with low acrylamide concentration (4% acrylamide) as the start point of the x axis (Fig. S1 F). We find that the stiffness of PA gels ranges from 8 to 80 kPa in the 2-mm-long “bar” region (Fig. 1 A). Furthermore, the overlap of the stiffness curves of different gels indicates that this method is robust and credible (Fig. 1 A).

To study the migration of cells on PA gels, we stain the cell nucleus with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride and trace the nucleus in 15-min intervals for 10 h. Because of the limitation of the view field of the microscopy, we trace the migration of cells in a 1.3 × 1.3-mm square region at the center region of PA gels (gray region in Fig. 1 A). We find that 3T3 cells prefer to migrate toward stiffer regions on gradient gels, whereas cells on 40-kPa uniform gels do not exhibit directional migration (Fig. 1 B). The migration angles of cells with respect to the direction of stiffness gradient (Fig. 1 C) are mostly within ∼−60° to 60° on gradient gels (around 70%), but the migration angles of cells on uniform gels are randomly distributed (Fig. 1 D). The morphology of 3T3 cells in the soft region of gradient gels is generally round, whereas cells in the stiff region display a flattened and polarized morphology (Fig. 1 E). The round cells are in the region where the stiffness of PA gels is small and uniform; thus, these cells are almost stationary and do not exhibit durotaxis. That is another reason why we measure cell migration at the center region of PA gels, where the stiffness of PA gel changes with the underlying position (gray region in Fig. 1 A). We also compare the migration speed of cells, i.e., the migration trajectory length per unit time (Fig. 1 C), on gradient gels and uniform gels. The migration speed of cells on gradient gels (0.68 ± 0.26 μm/min) is two times larger than that on uniform gels (0.34 ± 0.12 μm/min) (Fig. 1 F).

The extent to which cells migrate preferentially toward the stiffer region of gradient gels can be further quantified by the DI (10), which is defined as the ratio of the displacement in the direction of stiffness gradient to the total migration trajectory length (Fig. 1 C). If DI = 1, cells migrate straightly along the direction of the stiffness gradient. If DI = −1, cells migrate to the opposite direction of the stiffness gradient. Ideally, if DI = 0, cells exhibit a random migration. We find that the DI of 3T3 cells on gradient gels is around 0.36, whereas it decreases to 0.04 on uniform gels (Fig. 1 F). It should be noted that previous studies have shown that a stiffness gradient does not result in a density gradient of the coating fibronectin (11,12,27). Thus, the biased migration observed here is not a result of the spatial changes in ligand density. Together, these results indicate that a stiffness gradient can induce directional migration of 3T3 cells toward stiffer regions of gradient substrate.

Cell shrinks as cell migrates toward stiffer regions

Previously, we have found that the cell volume on stiff uniform PDMS substrates is ∼50% smaller than that on soft PDMS substrates (20). Therefore, we speculate that the cell volume might decrease as the cell migrates toward the stiffer region of gradient PA gels. To quantify the cell volume, we label the cellular cytoplasm with a fluorescent indicator CMFDA and use confocal microscopy to scan the 3D cellular morphology.

We first measure the cell volume on uniform PA gels when the stiffness of PA gels ranges from 0.5 to 150 kPa. We find that the cell volume decreases by almost 40% as the stiffness of PA gels increases (Fig. S3), which is in agreement with our previous study (20). It should be noted that the stiffness range of PDMS substrate in our previous study is 100–1000 kPa (20), which is much higher than the stiffness range of PA gels used in this study, but cells show a similar volume decrease on these two different kinds of substrates. Thus, these results imply that cells may actually sense the microscopic stiffness of substrates around focal adhesions, but not the bulk macroscopic stiffness, because cells sense rigidity by contracting against their substrates at the focal adhesions.

Next, we quantify the distribution of cell volume on gradient PA gels. To unify the positions of cells on different gels, we use the coordinates shown in Fig. S1 F to quantify cells’ positions. We scan the 3D cell morphology with confocal microscopy to calculate cell volume and measure the local substrate stiffness with AFM at the same time. We find that when a cell locates more closely to stiffer regions of gradient gels, the local substrate stiffness is bigger, whereas the cell volume is smaller (Fig. 1 G). The increase in local substrate stiffness also causes a bigger cell spread area and a smaller cell height (Fig. 1 H). We then divide each gradient gel into multiple strips with a width of 500 μm along the direction of stiffness gradient and quantify the average cell volume in these strips. We find that the cell volume decreases by as much as 40% as the position of cells and the local substrate stiffness increase (Figs. 1 I and S4 A, orange line). This is consistent with recent findings in 3D stiffness gradient hydrogel, which also found an inverse relationship between cell volume and local matrix stiffness (28). It should be noted that the cell volume of 3T3 cells on gradient PA gels still decreases exponentially with increasing spread area (Fig. S4 B), which is consistent with our previous work (20). Therefore, these results demonstrate that cell volume decreases dramatically as a cell migrates toward stiffer regions of gradient gels.

Na+/K+ ATPase, Na+/H+ exchanger, and mechanosensitive ion channels are required for the volume shrinkage

Does this volume decrease have significant effect on cell durotaxis? To address this point, we perturb the volume decrease on gradient gels with various treatments and then analyze the correlation between DI and the amplitude of volume decrease. Given that the regulation of cell volume is mainly determined by the transmembrane transports of ions and water (20,24) and cell volume is coupled to membrane tension, we can change the cell volume by three different ways. First, we can treat cells with various drugs to impede the transmembrane transport of ions. Second, we can apply osmotic shocks (i.e., hypotonic and hypertonic shocks) to perturb water transport. Third, we can perturb the cytoskeleton to change membrane tension and then cell volume.

We first study which specific ion transporters are implicated in the volume shrinkage. We find that the inhibition of Na+K+/2 Cl− cotransporter with Bum and the inhibition of /Cl− exchanger with DIDS do not result in remarkable cell volume change. The distribution of cell volume along the stiffness gradient is consistent with that of untreated cells (Fig. 2 A), and the amplitude of volume shrinkage ΔV is comparable with that of control cells (Fig. 2 B). However, inhibiting Na+/K+ ATPase with Oua and inhibiting the Na+/H+ exchanger with EIPA significantly reduce ΔV. The volume differences along the stiffness gradient of these inhibitions are much smaller than the volume difference of untreated cells (Fig. 2, A and B). We also use the spider venom peptide GsMTx4 to block the activity of mechanosensitive (MS) ion channels. The GSMTx4 treatment makes cells insensitive to the substrate stiffness, and the cell volume is almost constant along the stiffness gradient (Fig. 2, A and B), which implies a critical role of MS channels in rigidity sensing. Together, these results show that Na+/K+ ATPase, Na+/H+ exchanger, and MS channels are required for the volume shrinkage.

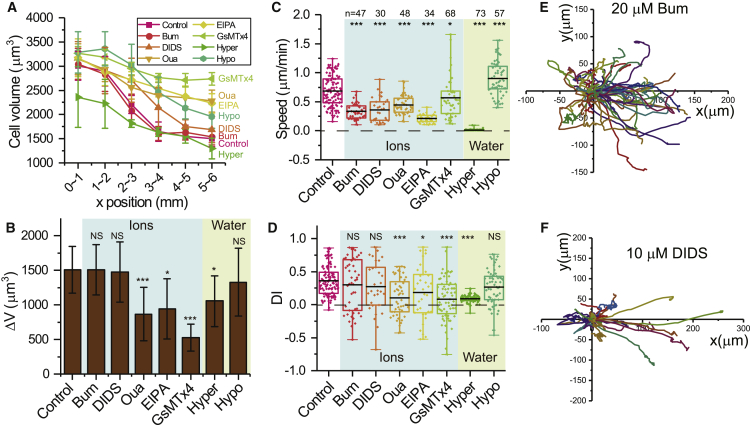

Figure 2.

Inhibition of ion transporters that are required for the volume shrinkage have significant effect on cell durotaxis. (A) Cell volume is shown as a function of cell position when cells are treated with Na+K+/2 Cl− cotransporter inhibitor Bum (20 μM), /Cl− exchanger blocker DIDS (10 μM), Na+/K+ ATPase inhibitor Oua (10 μM), Na+/H+ exchanger inhibitor EIPA (10 μM), or mechanosensitive ion channel blocker GsMTx4 (2 μM) or cells are cultured in a hypertonic (50% PEG) or hypotonic environment (50% water) (n = 10–22). Error bars are mean ± SD.∗p < 0.05, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, NS: nonsignificant difference. Data were analyzed by a one-way ANOVA. (B) The amplitude of volume decrease ΔV, which is defined as the difference of volume between cells on the softest region and the stiffest region, is shown after various treatments. Box plots of migration speed (C) and DI (D) after various treatments are given. Box plots show mean line and 25th and 75th percentiles, and whiskers extend to the maximal and minimal data points. n-values are shown above each category. (E and F) Migration trajectories of 3T3 cells treated with Bum and DIDS, respectively, are shown. To see this figure in color, go online.

Inhibition of ion transporters that are required for the volume shrinkage suppresses cell durotaxis

Next, we examine the effects of inhibition of ion transporters on the durotaxis of 3T3 cells. We find that inhibition of ion transport significantly hinders cell migration. The migration speed decreases 50–60% for various inhibitors (Fig. 2 C). For example, the migration speed decreases from 0.68 ± 0.26 μm/min to 0.33 ± 0.13 μm/min when inhibiting Na+K+/2 Cl− cotransporter with Bum, and it decreases to 0.36 ± 0.21 μm/min when inhibiting the Cl− channel with DIDS. Many studies have reported that the expressions of integrin and N-cadherin decrease radically when cells are treated with ouabain, which then inhibits cell migration (29,30). Here, we also find that the migration speed of 3T3 cell drops to 0.44 ± 0.16 μm/min when inhibiting Na+/K+ ATPase with Oua. Inhibiting the Na+/H+ exchanger with EIPA also significantly reduces the migration speed. Surprisingly, the migration speed only reduces from 0.68 ± 0.26 to 0.57 ± 0.35 μm/min after using GsMTx4 to block the activity of MS channels (Fig. 2 C). It has been found that the GsMTx4 can block the activation of TPRC1, TPRC6, and Piezo1 channels (31,32); thus, our results indicate that these channels may not be implicated in 3T3 fibroblast cell migration.

Even though all inhibitions of ion transport significantly reduce the migration speed, the effects of various ion transport inhibition on DI are different. From Fig. 2, B and D, we find that only the inhibition of ion transporters that reduce the amplitude of volume shrinkage ΔV leads to a decrease in DI. Compared with the untreated group (DI = 0.36 ± 0.23), the DI does not show a significant change when cells are treated with Bum or DIDS to inhibit Cl− transportation (Fig. 2 D), and 3T3 cells still prefer to migrate toward stiffer regions after these treatments (Fig. 2, E and F). However, DI decreases to 0.11 ± 0.29 after inhibiting Na+/K+ ATPase with Oua and 0.18 ± 0.40 after inhibiting Na+/H+ exchanger with EIPA (Fig. 2 D). Although DI decreases after inhibiting Na+/K+ ATPase and Na+/H+ exchanger, blocking those ion transporters does not alter the migration model of 3T3 cells from directional migration to random migration. From the migration trajectory and the rose plot of migration angle (Fig. S5, B and C), we find that 3T3 cells still prefer to migrate toward the stiffer region of PA gels after the treatments of Oua and EIPA. Previous studies have suggested an involvement of MS channels in cell rigidity sensing (33,34). Thus, impeding the activity of MS channels should prevent cells from detecting the stiffness gradient and result in random cell migration. As expected, after blocking the MS channels with GsMTx4, the direction of cell migration shows strong randomness (Fig. S5 D), and the DI reduces to 0.09 ± 0.32 (Fig. 2 D). Together, these results indicate that, if the volume decrease on gradient PA gels is impaired after inhibiting ion transporters, the durotaxis index also becomes smaller after inhibiting the same ion transporters.

Effects of osmotic shocks on the volume decrease and durotaxis index

We next alter the osmotic pressure of the medium to perturb the cell volume decrease. We find that a hypertonic shock causes a decrease of cell volume in the soft region but does not have a remarkable effect in stiff regions (Fig. 2 A) because cells in the stiff region may have reached their minimal volume (20) and cannot decrease their volume any more in a hypertonic environment. Thus, the amplitude of volume decrease, ΔV, is smaller after the hypertonic shock. 3T3 cells are almost stationary after the hypertonic shock, the migration speed is only 0.01 ± 0.01 μm/min (Figs. 2 C and S5 E). Thus, it is meaningless to discuss the directionality of cell migration in this case. Previous studies have found that a hypertonic environment would impair the formation of focal adhesions and suppress wound healing (35). Thus, the disappearance of cell migration in the hypertonic medium we found here may also result from the attenuation of focal adhesions.

After a hypotonic shock, the migration speed increases dramatically, from 0.68 ± 0.26 to 0.90 ± 0.28 μm/min (Fig. 2 C). This result is in agreement with a recent study that also showed that a hypotonic condition leads to an increase of migration speed (36). However, ΔV and DI do not show significant change after the hypotonic treatment (Fig. 2, B and D).

Effects of cytoskeletal disturbance on the cell volume decrease and durotaxis index

Cortical contractility has a critical influence on cell migration (37), and it is required for the cell volume decrease on stiff substrates (20). Therefore, we wonder whether 3T3 cells still show a biased migration toward the stiffer region when we perturb the cortical contractility to change cell volume. Thus, we examine the migration of 3T3 cells on gradient gels in the presence of various drugs that are known to modulate cortical contraction (Fig. 3, A and B). Two drugs that directly inhibit myosin contractility, blebbistatin and Y-27632, not only cause a decrease in migration speed but also abolish the directional migration (Figs. 3, A and B and S6, B and C). These findings are consistent with previous observations that inhibiting myosin contraction reduces the DI significantly (15). However, disrupting actin polymerization with latrunculin A (Lat A) or cytochalasin D (Cyto D) does not result in a remarkable change of durotaxis index (Fig. 3, B–D), even though these treatments significantly reduce the migration speed (Fig. 3 A).

Figure 3.

Microtubules and myosin contraction are required for the directional migration. Box plots of cell migration speed (A) and DI (B) when cells are treated with blebbistatin (Bleb, 10 μM, n = 85), Y-27632 (15 μM, n = 36), Lat A (1 μM, n = 49), Cyto D (2 μM, n = 24), and MT inhibitor nocodazole (Noc, 2.75 μM, n = 36) are given. Box plots show mean line and 25th and 75th percentiles, and whiskers extend to the maximal and minimal data points. ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, NS: nonsignificant difference. Data were analyzed by a one-way ANOVA. (C and D) Migration trajectories of 3T3 cells treated with Lat A and Cyto D, respectively, are shown. (E) DI plots as a function of volume difference ΔV are given. (F) Cell volume is shown as a function of the position along the direction of stiffness gradient when cells are treated with different inhibitors (n = 10–19). Error bars are mean ± SD. To see this figure in color, go online.

MTs can regulate actin-driven protrusion (13), which further affects membrane tension and cell volume, and previous studies have shown that MT depolymerization interferes with cell motility (38). Thus, we next study how the depolymerization of MTs affects cell durotaxis. When we depolymerize MTs with nocodazole, most cells lost their polarity, and hence, the pseudopod protrudes and retracts frequently (Fig. S7). The loss of cell polarity also results in a decrease of migration speed (Fig. 3 A) and the disappearance of cell durotaxis (DI decreases to 0.006 ± 0.19, Fig. 3 B).

Together, these results show that actin cortex, myosin contraction, and MTs are all crucial for efficient cell migration (Fig. 3 A), but the actin cortex is not required for maintaining the directionality of cell migration (Fig. 3, C and D).

Durotaxis index does not correlate with the volume decrease

From Fig. 2, B and D, we can find that inhibitions of ion transporters that reduce ΔV also lead to a remarkable decrease in DI. These results imply that DI may relate to ΔV. Thus, we further analyze the correlation between DI and ΔV. We find that DI does not show a strong correlation with ΔV (Fig. 3 E). As shown in Fig. 3 F, when we inhibit MTs polymerization with nocodazole, the volume decrease is similar to that of untreated cells (Fig. 3 F, solid line). However, the nocodazole treatment remarkably represses cell durotaxis (Fig. 3 B). Similar discrepancies can also be found in the inhibition of actin polymerization with Lat A and Cyto D, when the volume decrease is significantly suppressed (Fig. 3 F, dash-dot lines) but the DI does not show an apparent change (Fig. 3 B). Together, these results indicate that DI is not directly correlated with cell volume decrease; it may correlate with something else that can be related to cell volume.

Durotaxis index scales with the membrane tension difference of lamellipodia on the stiffer side and softer side of substrate

Because of the mechanical coupling between membrane tension and cell volume, the membrane tension also changes remarkably when there is a dramatic cell volume change. Thus, DI may correlate with membrane tension. It has been shown that there is a membrane tension gradient between the front and the rear of moving cells (39,40), and membrane tension plays a critical role in maintaining cell polarity (18). Therefore, we next study the relationship between cell durotaxis and the membrane tension difference between the cell front and cell rear.

To distinguish cell front and cell rear, we observe the cell migration for 20 min before measuring the membrane tension. Once the migration direction is confirmed, we use AFM to compress the lamellipodia at the front and rear of moving cells (Fig. 4, A and B). The membrane tension is given as (25), where F∗ and δ∗ are the differences of indentation force and piezo position between the contact point and the inflection point, respectively (Fig. S2). We first compare the membrane tension between the front and the rear of moving cells. We show that even though cells might transiently migrate toward the stiffer region (Fig. 4 A) or the softer region (Fig. 4 B), the local membrane tension at the front of moving cells is always bigger than the tension at the rear of moving cells (Fig. S8). Then, we study whether this membrane tension difference still exists after treating cells with various drugs. We quantify the difference of membrane tension with a ratio γfront/γrear, where γfront and γrear are the membrane tensions at the cell front and cell rear, respectively (Fig. 4, A and B). After disrupting cytoskeleton or inhibiting ion transportation, the membrane tension difference still exists, and the tension ratio γfront/γrear is still bigger than 1 (Fig. 4 C). However, the disturbance of both ion transportation and the cytoskeleton leads to a smaller ratio of γfront/γrear than that of the untreated group. We also find that the migration speed increases linearly with γfront/γrear (Fig. 4 C), but the DI does not correlate with γfront/γrear (Fig. 4 D).

Given that the migration speed relates to the membrane tension difference in the direction of cell migration, i.e., the membrane tension difference between the cell front and cell rear, the DI of cells may relate to the membrane tension difference in the direction of stiffness gradient. To verify this assumption, we define another parameter, γstiff/γsoft; this parameter represents the ratio between the membrane tension of lamellipodia on the stiffer side and softer side of gradient gels. The membrane tensions on stiffer and softer sides of the gradient gels, i.e., γstiff and γsoft, are deduced from γfront and γrear. If cells migrate toward stiffer regions, γstiff = γfront and γsoft = γrear (Fig. 4 A). If cells migrate toward softer regions, γstiff = γrear and γsoft = γfront (Fig. 4 B). Thus, γstiff/γsoft > 1 when cells migrate toward the stiffer side of the gradient gels (Fig. 4 A), and γstiff/γsoft < 1 when cells migrate toward the softer side of the gradient gels (Fig. 4 B). We find that the migration speed does not linearly correlate with γstiff/γsoft (Fig. 4 E), but the DI increases linearly with γstiff/γsoft (Fig. 4 F). We also find that inhibition of Na+/K+ ATPase and Na+/H+ exchanger results in smaller γstiff/γsoft. Together, these results show that the difference of membrane tension in the direction of stiffness gradient is functionally relevant to the directionality of cell durotaxis.

Discussion

It has been shown that cell durotaxis depends on the stiffness gradient (10) and the coating composition (11) of substrates. However, whether cell durotaxis relates to the volume regulation is unclear. To address this question, we study the volume distribution of 3T3 cells that migrate on PA gels with a stiffness gradient. We show that 3T3 cells tend to migrate toward the stiffer regions of PA gels. The migration speed of 3T3 cells on gradient substrates is bigger than that on uniform substrates, similar to what has been observed in previous studies (10,15). When cells migrate toward the stiffer region, the increase in substrate stiffness promotes the spread of cells and causes a decrease in cell volume. We also find that the DI increases linearly with the membrane tension difference between lamellipodia on the stiffer side and the softer side of the gradient substrate.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the changes in cell volume during durotaxis. We have previously shown that the increase in stiffness of uniform PDMS substrate leads to a bigger cell spread area and stronger cortical contraction, which further expels water and ions out of cells and induces a volume decrease (20). Here, we find that cell volume decreases dramatically during cell durotaxis on gradient PA gels. This volume decrease requires Na+/H+ exchanger, Na+/K+ ATPase, and MS channels. It should be noted that some cells, such as neuron and T cells, may prefer to migrate toward softer substrates because the traction forces of these cells are bigger on soft substrates than on stiff substrates (41,42). Because of a smaller spreading area on softer substrates, the cell volume of these cells may not decrease but increase because they migrate toward softer substrates. Thus, the mechanism we found here may be only applicable to cells that tend to migrate toward stiffer substrates and show a bigger spreading area on stiffer substrates.

Our work shows that ion transporter plays a pivotal role in cell migration and unveils different effects of various ions transportation on cell durotaxis. It has been shown that Na+/H+ exchangers, /Cl− anion exchangers, and aquaporins are implicated in cell migration (Fig. 4 G; (43,44)). We find that the inhibition of Na+/H+ exchanger with EIPA, the inhibition of Na+/K+ ATPase with Oua, the inhibition of Na+K+/2 Cl− cotransporter with Bum, and the inhibition of /Cl− anion exchangers with DIDS all cause a decrease in cell migration speed (Fig. 2 A). Therefore, our findings further verify the critical roles of these ion transporters in cell migration. However, we find that not all the inhibitions of ion transporters show significant effect on DI. Only the inhibition of ion transporters that reduce the amplitude of volume shrinkage on gradient gels leads to smaller DI. That is, only the inhibition of Na+/H+ exchanger with EIPA and the inhibition of Na+/K+ ATPase with Oua lead to a decrease in DI. Inhibition of Na+K+/2 Cl− cotransporter with Bum and inhibition of /Cl− anion exchangers with DIDS do not lead to a significant change in DI. Thus, our results also elucidate that the transportation of Na+ and K+, but not the transportation of Cl−, is implicated in cell durotaxis. These results indicate that the underlying mechanisms controlling the migration speed and deciding migration direction are different.

To migrate directionally on substrates with a stiffness gradient, cells must first detect the differences in substrate stiffness. MS channels are found to locate at or near focal adhesions; the traction force transmitted by actin stress fiber can activate these MS channels, which then increases cytoplasmic concentration (45, 46, 47, 48). A recent study also found that the activity of Piezo1 increases with substrate stiffness, thus suggesting a role for Piezo1 in detecting matrix elasticity (33). Here, we find that MS channels play a critical role in sensing the substrate gradient. The inhibition of MS channels prevents cells from detecting the stiffness gradient and results in random cell migration. Furthermore, the cell volume after this inhibition is independent of cell position along the stiffness gradient (i.e., independent of substrate stiffness). Thus, our findings provide more evidence for the role of MS channels in rigidity sensing.

After detecting differences in substrate stiffness, cells need to polarize in the direction of the stiffness gradient and then migrate along that direction. Previous studies usually attribute the directional cell migration to the polarization of traction force (9,16). However, here we find that the polarization of membrane tension is another mayor player of directional cell migration. We find that the membrane tension at the cell front is bigger than that at the cell rear, which is consistent with recent findings (39,40). Lower membrane tension at the cell rear can facilitate the activation of RhoA to promote rear retraction (40), and it has been shown that Rac1 is more active at the cell front, whereas Rho is more active at the cell rear (49). Thus, the contraction force generated by myosin may be bigger at the cell rear. However, we find that the membrane tension at the cell rear is lower than that at the cell front. These results indicate that the polarities of traction force and membrane tension may be different in 3T3 fibroblast cell durotaxis.

We also find that the migration speed is proportional to the membrane tension difference between the cell front and cell rear, whereas DI scales with the membrane tension difference between lamellipodia on the stiffer side and the softer side of the substrate. These results further emphasize the difference between the underlying mechanism of cell migration and directed cell migration.

The cell volume is tightly coupled to the membrane tension (23,24,50), but the relationship between cell volume and membrane tension is not simply monotonous. As demonstrated in a previous experiment (51), an increase in cell volume after hypotonic shock leads to a bigger membrane tension (Fig. 4 H), but an increase in cell volume after actin depolymerization is accompanied by a smaller membrane tension (Fig. 4 H). Because of the coupling between cell volume and membrane tension, inhibition of Na+/H+ exchanger and Na+/K+ ATPase would result in a smaller cell volume decrease, which then leads to a smaller membrane tension difference (Fig. 4 F). This finding implies that the volume decrease during cell durotaxis may help to maintain the polarization of membrane tension. Thus, our results further indicate the mechanical coupling between cell volume and membrane tension and reveal the importance of considering cell volume and membrane tension together when interpreting the effect of cell volume or membrane tension on cell functions. However, it would need further exploration to reveal the mechanism of how cell volume affects membrane tension and then cell durotaxis.

Our results also have important implications for collective cell migration. Recent experimental researches have observed that collective cell migration is also sensitive to the gradient of chemical signals (52) and substrate stiffness (53). Here, we find that cell volume decreases dramatically during durotaxis; thus, it may also play a critical role in collective cell migration when the underlying stiffness is changing. Further exploration is needed to answer this question.

Author Contributions

Y.Y. and K.X. contributed equally to this study. H.J. initiated and supervised the project. Y.Y. and K.X. performed experiments. All authors analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 11622222, 11872357 and 11472271), the Thousand Young Talents Program of China, the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, and the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. XDB22040403), the National Postdoctoral Program for Innovative Talents (Grants No. BX20190318), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grants No. 2019M662188), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grants No. WK2090000017), the USTC Research Funds of the Double First-Class Initiative (Grants No. YD2480002001), and Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grants No. 2008085QA24). This work was partially carried out at the University of Science and Technology of China Center for Micro and Nanoscale Research and Fabrication.

Editor: Guy Genin.

Footnotes

Yuehua Yang and Kekan Xie contributed equally to this study.

Supporting Material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2020.07.039.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Boldajipour B., Mahabaleshwar H., Raz E. Control of chemokine-guided cell migration by ligand sequestration. Cell. 2008;132:463–473. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krawczyk W.S. A pattern of epidermal cell migration during wound healing. J. Cell Biol. 1971;49:247–263. doi: 10.1083/jcb.49.2.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedl P., Gilmour D. Collective cell migration in morphogenesis, regeneration and cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;10:445–457. doi: 10.1038/nrm2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamalice L., Le Boeuf F., Huot J. Endothelial cell migration during angiogenesis. Circ. Res. 2007;100:782–794. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000259593.07661.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roussos E.T., Condeelis J.S., Patsialou A. Chemotaxis in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2011;11:573–587. doi: 10.1038/nrc3078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weber M., Hauschild R., Sixt M. Interstitial dendritic cell guidance by haptotactic chemokine gradients. Science. 2013;339:328–332. doi: 10.1126/science.1228456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gunawan R.C., Silvestre J., Leckband D.E. Cell migration and polarity on microfabricated gradients of extracellular matrix proteins. Langmuir. 2006;22:4250–4258. doi: 10.1021/la0531493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King S.J., Asokan S.B., Bear J.E. Lamellipodia are crucial for haptotactic sensing and response. J. Cell Sci. 2016;129:2329–2342. doi: 10.1242/jcs.184507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lo C.-M., Wang H.-B., Wang Y.L. Cell movement is guided by the rigidity of the substrate. Biophys. J. 2000;79:144–152. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76279-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Isenberg B.C., Dimilla P.A., Wong J.Y. Vascular smooth muscle cell durotaxis depends on substrate stiffness gradient strength. Biophys. J. 2009;97:1313–1322. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartman C.D., Isenberg B.C., Wong J.Y. Vascular smooth muscle cell durotaxis depends on extracellular matrix composition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:11190–11195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1611324113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vincent L.G., Choi Y.S., Engler A.J. Mesenchymal stem cell durotaxis depends on substrate stiffness gradient strength. Biotechnol. J. 2013;8:472–484. doi: 10.1002/biot.201200205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaverina I., Straube A. Volume 22. Elsevier; 2011. Regulation of cell migration by dynamic microtubules; pp. 968–974. (Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akhshi T.K., Wernike D., Piekny A. Microtubules and actin crosstalk in cell migration and division. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2014;71:1–23. doi: 10.1002/cm.21150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raab M., Swift J., Discher D.E. Crawling from soft to stiff matrix polarizes the cytoskeleton and phosphoregulates myosin-II heavy chain. J. Cell Biol. 2012;199:669–683. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201205056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breckenridge M.T., Desai R.A., Chen C.S. Substrates with engineered step changes in rigidity induce traction force polarity and durotaxis. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 2014;7:26–34. doi: 10.1007/s12195-013-0307-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han S.J., Rodriguez M.L., Sniadecki N.J. Spatial and temporal coordination of traction forces in one-dimensional cell migration. Cell Adhes. Migr. 2016;10:529–539. doi: 10.1080/19336918.2016.1221563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Houk A.R., Jilkine A., Weiner O.D. Membrane tension maintains cell polarity by confining signals to the leading edge during neutrophil migration. Cell. 2012;148 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.050. 17C5–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo M., Pegoraro A.F., Weitz D.A. Cell volume change through water efflux impacts cell stiffness and stem cell fate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1705179114. E8618-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie K., Yang Y., Jiang H. Controlling cellular volume via mechanical and physical properties of substrate. Biophys. J. 2018;114:675–687. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.11.3785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stroka K.M., Jiang H., Konstantopoulos K. Water permeation drives tumor cell migration in confined microenvironments. Cell. 2014;157:611–623. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saias L., Swoger J., Solon J. Decrease in cell volume generates contractile forces driving dorsal closure. Dev. Cell. 2015;33:611–621. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang H., Sun S.X. Cellular pressure and volume regulation and implications for cell mechanics. Biophys. J. 2013;105:609–619. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang Y., Jiang H. Shape and dynamics of adhesive cells: mechanical response of open systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2017;118:208102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.118.208102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manoussaki D., Shin W.D., Chadwick R.S. Cytosolic pressure provides a propulsive force comparable to actin polymerization during lamellipod protrusion. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:12314. doi: 10.1038/srep12314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tse J.R., Engler A.J. Preparation of hydrogel substrates with tunable mechanical properties. Curr. Protoc. Cell Biol. 2010;Chapter 10 doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb1016s47. Unit 10.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sunyer R., Jin A.J., Sackett D.L. Fabrication of hydrogels with steep stiffness gradients for studying cell mechanical response. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Major L.G., Holle A.W., Choi Y.S. Volume adaptation controls stem cell mechanotransduction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11:45520–45530. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b19770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu N., Li Y., Li J. Inhibition of cell migration by ouabain in the A549 human lung cancer cell line. Oncol. Lett. 2013;6:475–479. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ninsontia C., Chanvorachote P. Ouabain mediates integrin switch in human lung cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:5495–5502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson M., Kim E.Y., Dryer S.E. Opposing effects of podocin on the gating of podocyte TRPC6 channels evoked by membrane stretch or diacylglycerol. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2013;305:C276–C289. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00095.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bae C., Sachs F., Gottlieb P.A. The mechanosensitive ion channel Piezo1 is inhibited by the peptide GsMTx4. Biochemistry. 2011;50:6295–6300. doi: 10.1021/bi200770q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pathak M.M., Nourse J.L., Tombola F. Stretch-activated ion channel Piezo1 directs lineage choice in human neural stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:16148–16153. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409802111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gudipaty S.A., Lindblom J., Rosenblatt J. Mechanical stretch triggers rapid epithelial cell division through Piezo1. Nature. 2017;543:118–121. doi: 10.1038/nature21407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamura M., Osajima A., Nakashima Y. High glucose levels inhibit focal adhesion kinase-mediated wound healing of rat peritoneal mesothelial cells. Kidney Int. 2003;63:722–731. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Batchelder E.L., Hollopeter G., Plastino J. Membrane tension regulates motility by controlling lamellipodium organization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:11429–11434. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010481108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gupton S.L., Anderson K.L., Waterman-Storer C.M. Cell migration without a lamellipodium: translation of actin dynamics into cell movement mediated by tropomyosin. J. Cell Biol. 2005;168:619–631. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200406063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liao G., Nagasaki T., Gundersen G.G. Low concentrations of nocodazole interfere with fibroblast locomotion without significantly affecting microtubule level: implications for the role of dynamic microtubules in cell locomotion. J. Cell Sci. 1995;108:3473–3483. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.11.3473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lieber A.D., Schweitzer Y., Keren K. Front-to-rear membrane tension gradient in rapidly moving cells. Biophys. J. 2015;108:1599–1603. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hetmanski J.H.R., de Belly H., Caswell P.T. Membrane tension orchestrates rear retraction in matrix-directed cell migration. Dev. Cell. 2019;51:460–475.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2019.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chan C.E., Odde D.J. Traction dynamics of filopodia on compliant substrates. Science. 2008;322:1687–1691. doi: 10.1126/science.1163595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bangasser B.L., Rosenfeld S.S., Odde D.J. Determinants of maximal force transmission in a motor-clutch model of cell traction in a compliant microenvironment. Biophys. J. 2013;105:581–592. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klein M., Seeger P., Schwab A. Polarization of Na(+)/H(+) and Cl(-)/HCO (3)(-) exchangers in migrating renal epithelial cells. J. Gen. Physiol. 2000;115:599–608. doi: 10.1085/jgp.115.5.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Papadopoulos M.C., Saadoun S., Verkman A.S. Aquaporins and cell migration. Pflugers Arch. 2008;456:693–700. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0357-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hayakawa K., Tatsumi H., Sokabe M. Actin stress fibers transmit and focus force to activate mechanosensitive channels. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:496–503. doi: 10.1242/jcs.022053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kobayashi T., Sokabe M. Sensing substrate rigidity by mechanosensitive ion channels with stress fibers and focal adhesions. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2010;22:669–676. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cáceres M., Ortiz L., Cerda O. TRPM4 is a novel component of the adhesome required for focal adhesion disassembly, migration and contractility. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yao M., Tijore A., Sheetz M.P. Force-dependent Piezo1 recruitment to focal adhesions regulates adhesion maturation and turnover specifically in non-transformed cells. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.09.972307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reig G., Pulgar E., Concha M.L. Cell migration: from tissue culture to embryos. Development. 2014;141:1999–2013. doi: 10.1242/dev.101451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang Y., Jiang H. Cellular volume regulation and substrate stiffness modulate the detachment dynamics of adherent cells. J. Mech. Phys. Solids. 2018;112:594–618. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stewart M.P., Helenius J., Hyman A.A. Hydrostatic pressure and the actomyosin cortex drive mitotic cell rounding. Nature. 2011;469:226–230. doi: 10.1038/nature09642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Malet-Engra G., Yu W., Dupré L. Collective cell motility promotes chemotactic prowess and resistance to chemorepulsion. Curr. Biol. 2015;25:242–250. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sunyer R., Conte V., Trepat X. Collective cell durotaxis emerges from long-range intercellular force transmission. Science. 2016;353:1157–1161. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf7119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.