Abstract

Rationale & Objective

Attention to geriatric impairments is not routinely provided to older adults receiving dialysis. Our objective was to identify patient and personnel perspectives on experiences with geriatric problems, unmet needs that may affect a patient’s ability to maintain his or her functional status, and preferences for design of a geriatric model of care tailored to address the unmet needs.

Study Design

Qualitative study using semi-structured interviews and focus groups.

Setting & Participants

14 hemodialysis patients 55 years and older and 24 dialysis unit personnel (eg, nephrologists, nurses, patient care technicians, and social workers) representing 5 dialysis units.

Analytical Approach

Content analysis to identify themes reflecting unmet needs and design considerations for a geriatric model of care for older adults receiving dialysis.

Results

4 themes (or unmet needs) identified from both patient and personnel transcripts were: (1) mobility, which referred to the insufficient mobility assessment and transportation services; (2) medications, which referred to insufficient attention to appropriate prescribing and medication self-management; (3) social support, which referred to insufficient support for activities of daily living and emotional problems; and (4) communication, which referred to insufficient patient-provider and interprofessional communication, including data transfer across separate health systems. Although participants generally acknowledged that an integrated model of care could result in benefits across all 4 areas of unmet need, they noted that the program design would need to minimize disruption of current workflow and practices in dialysis units.

Limitations

The findings may not be broadly representative of all older adults receiving dialysis and dialysis unit personnel.

Conclusions

There is insufficient attention to mobility, medication management, social support, and communication needs for older adults receiving in-center hemodialysis. Addressing these unmet needs in a geriatric model of care and measuring its effectiveness are areas of future research.

Index Words: Aged, hemodialysis, needs assessment, interviews, functional impairment, frailty

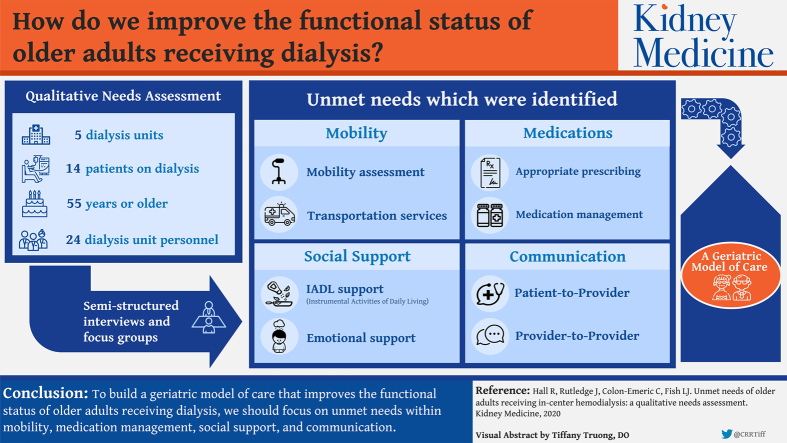

Graphical abstract

Plain-Language Summary.

Older adults receiving dialysis commonly experience geriatric problems, such as falls, limited mobility, polypharmacy, and cognitive deficits. These geriatric problems are managed by geriatric assessment, which involves a multidisciplinary team conducting a multidimensional evaluation (eg, functional status, cognition, social support, mood, comorbid conditions, and medications). Geriatric assessment is not routinely integrated into the dialysis setting; however, a multidisciplinary care team is standard of care. In this qualitative study, we interviewed patients and dialysis unit personnel to identify opportunities to enhance geriatric care provided by the dialysis care team. Patients and personnel reported adverse events that stem from 4 unmet needs (or domains that need improvement): mobility, medication management, social support, and communication. These unmet needs provide a framework for integrating geriatric assessment into the dialysis setting.

Editorial, p. 514

Adults 65 years and older make up nearly half the adult US dialysis population. Because they commonly have multiple comorbid conditions and geriatric impairments,1,2 older adults receiving dialysis contribute to the health system’s “high-cost, high-need” patients.3 Such patients may benefit from clinical care consistent with the approach of the World Health Organization (WHO) to integrated health care for older adults. According to the WHO, this integrated clinical care should involve a coordinated effort among all health care providers to help older adults improve or maintain functional status and prevent adverse events.4 However, there are no systematic approaches to providing such integrated care to older adults receiving dialysis.5

Outside the dialysis setting, geriatric models of care have been integrated into primary care or geriatric specialty clinics to encompass the WHO approach and improve functional outcomes and health care use for older adults.6, 7, 8, 9 For example, Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders (GRACE) is a model of care integrated with primary care involving an advance practice provider and social worker dyad who conduct in-home geriatric assessment with management of common geriatric conditions and care coordination across multiple providers.8 For a geriatric model of care to be provided for older adults receiving dialysis, there must be consideration of the unique challenges of end-stage kidney disease self-management, hemodialysis treatment time, and dialysis unit workflow. Some dialysis units have navigated these challenges in patient-centered medical homes or End-Stage Renal Disease Seamless Care Organizations value-based care programs.10,11 However, more information is needed to understand how a model of care similar to GRACE could fill gaps in care for older adults receiving dialysis.

We conducted a needs assessment using qualitative methods to gain both patient and dialysis personnel perspectives on: (1) unmet needs that influence functional status, and (2) adaptation of GRACE to address these unmet needs.

Methods

Study Design and Participant Population

We conducted this qualitative study with patients and dialysis personnel between May and November 2018. We approached patients enrolled in an observational study involving longitudinal physical performance measures. For that study, eligible patients were receiving in-center hemodialysis for at least 1 month and were 55 years or older. Because kidney failure is associated with accelerated aging and frailty is common in hemodialysis even in mid-life,12,13 we used a younger age cut-point to capture patients who are at risk for functional decline. Patients were ineligible if they were nonambulatory, had advanced dementia, were non–English speaking, were in hospice care, resided in long-term care, or were dependent in all basic activities of daily living (ADLs). For this study, we purposively sampled for patients with low, moderate, or high Lawton instrumental ADL (IADL) scores (ie, high score indicating patient reports independence with home activities such as meal preparation).14 We included dialysis personnel who served in one of the following roles: nephrologist, social worker, dietician, nurse manager, nurse, and patient care technician. Both patients and dialysis personnel were recruited from 5 dialysis units proximate to Durham, NC, where the nephrologists also serve as faculty at Duke University.

This study was approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board (Pro00075802). We report our study design and findings according to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist (Table S1).15

Recruitment and Data Collection Procedures

Dialysis unit social workers distributed study recruitment letters to potentially eligible patients. Patients who expressed interest in participation were approached by a research coordinator for the informed consent process. Personnel were recruited through fliers posted in the staff workroom and/or e-mail announcements. The study team arranged day and time for personnel focus groups with those who wanted to participate. Informed consent for personnel was conducted at the beginning of each focus group.

For patients, semi-structured interviews were conducted at dialysis units by a research coordinator (J.R.) trained in interviewing methodology. For personnel, focus groups (or interviews) were conducted and moderated by an experienced qualitative researcher (L.J.F.) at their workplace (dialysis unit or office) during regular staff meeting times. We planned focus groups with personnel to gain insights from the interactive discussion of their individual experiences. To ensure that perspectives from all focus group participants were captured, we used a modified nominal group technique (described next) and the moderator attempted to balance participation with statements such as “Who else has something to say?” Focus groups with nephrologists were separate from focus groups with other clinic personnel to avoid concerns about traditional power dynamics. Interviewers (J.R. and L.J.F.) were not employed by the dialysis units and had no prior relationships with the patients or dialysis unit personnel.

To understand how a model of care similar to GRACE could fit in the dialysis care setting, we asked both open-ended and focused questions for perspectives in each of 3 specific categories: (1) lived experiences with specific geriatric problems; (2) communication among patient, caregiver, and health care providers (nephrology and primary care providers [PCPs]); and (3) program preferences. We used a visual aid to demonstrate GRACE program components (eg, medication review, mobility assessment, emotional support, cognitive assessment, and care coordination) and probed for perceived benefits and preferences (eg, home vs dialysis visits). To gain personnel perspectives on their patients’ experiences, the focus groups started with a modified nominal group technique with the question: “What are the biggest threats to the well-being of older dialysis patients?” After the list was generated, each person was given 5 dot stickers to place next to the 5 threats they viewed as most important.8 Full interview guides are available as Items S1 and S2. Interviews and focus groups lasted up to an hour and were audio recorded and transcribed. Transcripts were not returned to participants for review. We maintained field notes during interviews and prepared memos after each interview.

Using a common approach for identifying saturation,16 coded transcripts and memos were reviewed for broad themes at intervals to determine whether new themes were identified. Through this process, we captured redundancy in broad themes after 14 patient interviews irrespective of IADL score. Although 4 focus groups can often yield the most themes,17 there was not complete overlap in broad themes after we conducted 4 personnel focus groups. As a result, we conducted 3 personnel semi-structured interviews that contributed to our understanding of the broad themes.

In addition to interviews, we obtained the following data from patients and/or their dialysis unit medical records: demographics (age, sex, and race), length of time receiving dialysis, residence type, assistive device use, and comorbid conditions (for Charlson Comorbidity Index), and Lawton IADL score. We collected personnel demographics.

Data Analysis

We conducted descriptive statistics on participant characteristics. From the modified nominal group technique, we tallied votes for each unique concern and qualitatively compared concerns across focus groups.18 Two experienced qualitative researchers (R.H. and L.J.F.) conducted the qualitative analysis using a content analysis theoretical framework. To guide this content analyses, we used a systematic multistage approach: (1) familiarization, (2) identifying a conceptual framework, (3) indexing, (4) charting and mapping, and (5) interpretation.19,20

Familiarization involved the research team (R.H. and L.J.F.) reviewing 3 transcripts to become familiar with the data. Using GRACE as the basis for our theoretical framework, we developed our initial coding framework that centered around identifying: (1) unmet needs among older adults receiving dialysis and (2) current approaches to care management among health care services (eg, nephrology, primary care, and community resources). As a result, this initial (a priori) coding framework included patient needs, geriatric problems, and health care services (full list in Item S3). We conducted line-by-line coding of a single transcript. We met to discuss the transcript and modify the initial coding framework. In the indexing stage, we conducted line-by-line coding of the remaining transcripts. Our coding included memos for each transcript to annotate coders’ questions, decisions about the data, and reflections on analysis. The annotations were discussed at regular intervals to ensure consistency in coding. After coding, we identified prominent themes (or unmet needs) from the patient transcripts that suggest the root cause of patient experiences and/or problems (eg, missed dialysis is related to insufficient transportation).

In the charting and mapping stage, we grouped similar codes into those themes and compared themes between patients and dialysis personnel. We matched dialysis personnel codes into the prominent themes identified from patient transcripts when appropriate. Because level of IADL independence affects unmet needs, we integrated participant IADL score with charting summaries to compare perspectives among those who had high (IADL score range, 6-8), medium (IADL score range, 3-5), and low scores (IADL score range, 0-2; most dependent).

In the interpretation stage, we identified major themes and associated quotes to summarize the results. We presented findings to personnel participants for confirmation, and there was no disagreement. We did not present a summary of findings to patients because of concern for excessive burden for recontacting them. NVivo 12 software was used for qualitative data analysis.

Results

Cohort Characteristics

We included 38 participants, with 14 patients and 24 dialysis unit personnel (21 participated in focus groups and 3 had semi-structured interviews; Table 1). Among the 14 patients, mean age was 70.4 (SD, 5.5; range, 61-80) years, 7 were women, and 10 were African American. Most dialysis personnel interviewed were nurses or patient care technicians (n = 12), followed by nephrologists (n = 8).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) or N (%) |

|---|---|

| Dialysis Patients (N = 14) | |

| Age, y | 70.4 (5.5) |

| Female sex | 7 (50%) |

| Race | |

| White | 4 (29%) |

| African American | 10 (71%) |

| Time on dialysis, y | 3.1 (3.5) |

| Functional status | |

| IADL 6-8 | 5 (36%) |

| IADL 3-5 | 6 (43%) |

| IADL 0-2 | 3 (21%) |

| Type of residence | |

| Home | 14 (100%) |

| Dialysis Unit Personnel (N = 24) | |

| Participant type | |

| Nurse, patient care technician | 12 (50%) |

| Social worker or dietician | 2 (8%) |

| Dietician | 1(4%) |

| Nurse manager | 1 (4%) |

| Physician | 8 (33%) |

| Age, y | 40.4 (10.8) |

| Female | 14 (58%) |

| Race | |

| White | 11 (46%) |

| African American | 6 (25%) |

| Othera | 7 (29%) |

| Hispanic Ethnicity | 2 (8%) |

Note: Values for categorical variables are given as number (percent); values for continuous variables are given as mean (standard deviation [SD]).

Abbreviation: IADL, instrumental activities of daily living.

Other race includes Asian, Native American, Pacific Islander, Alaska native, or race not reported by participant.

Summary of Unmet Need Themes

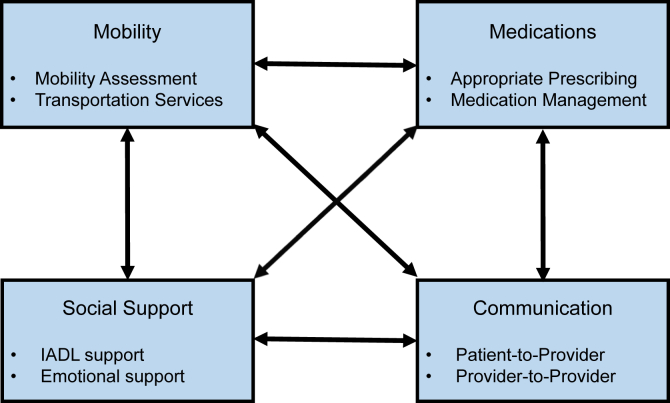

The unmet needs prominent in both patient and personnel transcripts were categorized into 4 interrelated areas: mobility, medications, social support, and communication. These 4 unmet needs were interrelated because an unmet need in one area was often related to an unmet need in another (eg, a patient with mobility limitations may miss medications because of insufficient social support for organizing medications; Fig 1). Table 2 depicts the unmet need themes, subthemes, and example quotes. We have described each theme and its related subthemes next and differences between patient and personnel perspectives, as well as differences in patient perspectives by IADL score.

Figure 1.

Four primary unmet needs of older adults receiving dialysis. Figure depicts the 4 domains of unmet needs in mobility, medications, social support, and communication and their related subthemes. Arrows emphasis the interrelatedness of the 4 domains. Abbreviation: IADL, instrumental activities of daily living.

Table 2.

Unmet Needs Themes, Subthemes, and Example Quotes

| Subtheme | Patient Quote | Personnel Quote |

|---|---|---|

| Mobility | ||

| Mobility assessment | “I ended up falling and I couldn’t get up…. And I couldn’t reach my phone [so I waited] until she finally came into my room, she saw I was on the floor cause…when I fell I kind of like wrapped myself like a pretzel and I couldn’t get up.” (Man in his 70s with high IADL score) | “I just see them in the chair and you know, I have often times been surprised seeing them in some other part of the hospital and either they’re more active than I think they are or less active, so yeah, I do think that mobility, it’s certainly a concern.” (Nephrologist) |

| Transportation services | “Well, it’s okay. I had to stand my ground because they kept sending a van, but no lift and there’s 1 person can help me get up the van with the steps because she helps me good, but the other ones, no. The last one I had to have her 3 times and she just stands out there and I had to try to get on myself and then when I get on she’s driving like maniac, I mean really, like maniac. … the other day she told me, oh, you have to put your bags on because my back hurts. I said lady, I’ve been hurting more than that so come on.” (Woman in her 70s with low ADL score) | “So, they really don’t like waiting, when you schedule a trip it’s not as if they just come 30 minutes you know, like 2 minutes right before your ride comes they give you a window, you have to be ready in that window. So, say your dialysis appointment is at 12 o’clock but they need to come and pick you up at you know, 11:15. They have to be ready you know, a little earlier than what you might normally would be ready if someone is driving you, so that’s frustrating sometimes for patients. They will only blow the horn and wait 5 minutes … if the volume is low or they’re in the house they hear the horn you know, they can’t move as fast as they could when they were in their 30s to get to the you know, outside in time for the van… It will drive away.” (Social worker) |

| Medication | ||

| Appropriate prescribing | “And then so, you know when you go to urgent care and different places and you tell them your doctor he’s supposed to always get a report back …so I don’t know if he got it or not. All I know is he didn’t take me off it and I didn’t have sense enough to get off it.” (Woman in her 60s with high IADL score) | “…the med list at the dialysis unit is correct a small proportion of the time…. They have like 3 different med lists.” (Nephrologist) |

| Medication Management | “And my wife had to help me do it because my mind wasn’t functioning right, so I got my meds all mixed up and when I was supposed to take ‘em from the morning to the evening and stuff like that so she had to do ‘em for me.” (Man in his 70s with high IADL score) “I take this color and I take this little pill and that color and that big horse pill, you understand? So you know, at least I knew so now my only worry, I knew what pills to take, I just had to keep in my mind, have you taken your medicine today or not cause I didn’t want to take it twice.” (Woman in her 60s with high IADL score) |

“The availability of medication, the cost in the elderly. I have a hard time at times, a patient who has Medicare as an elderly dialysis patient with some supplemental insurance where we basically struggle getting a [phosphorus] binder paid for.” (Nephrologist) “Being, I don’t know, my average patient is on 20 medicines or something like that and you know, we tell them to take 3 of 1 pill, 4 of another one at this and that time and you know, when we go and review their labs you know, we assume that they’re taking these and thus we need to increase or decrease the medicines, but the first question that needs to be assessed is whether really, are they really taking them…what their understanding of what they need [to take is].” (Nephrologist) |

| Social Support | ||

| IADL support | “…the things that when I’m at home that I’m not able to do any more and of course I’ve accepted it, but like for an example I can’t mow my grass or ride my mower or run my tiller and have a garden in my back yard.” (Man in his 80s with medium IADL score) | “so I have reported it to APS before if there’s some other issues going on in the home in which I feel like you know, a patient is being neglected or abused in any kind of way. We have to report that. And then sometimes it’s not necessarily a family member, it might be just a patient just not able to take care of themselves.” (Social worker) |

| Emotional support | “Yeah, and they don’t address that [death] in dialysis you know, they don’t have nobody - well I guess they had a social worker you can talk to, but it’s you know, and I guess the social worker will talk to you, but and I’m sure that some people do talk to the social worker about it cause it will affect different people different ways…and you try to be immune to it or get hard or hard core about it, it’s something’s that’s gonna happen you know, and I ain’t saying you get used to it, you don’t.” (Man in his 70s with medium IADL score) | “Patients may appear to be a little bit more solemn or depressed. Like I said, maybe they used to come in smiling and could laugh and joke but now they’re a little bit more quiet, they don’t smile as much, or a lot of times they will verbally say you know, I’m not sure how much longer I’m gonna be here. This just doesn’t feel right or they start saying their goodbyes or they start talking about death and making sure my family is okay and having those types of conversations with you in conjunction with you know, you can see a physical decline” (Social worker) |

| Communication | ||

| Patient-provider communication | “Well, see what happen is, you see, what he (nephrologist) does…he reads my report and the only thing he does is check to see if everything going as the prescription. You see, somebody gave him a prescription for what I was supposed to have done you know, and he base his thing on what you know, what’s going on you know. You see, most time, all he do is adjust my weight up and down…I guess he got to figure out…certain things you know, it’s just so quick. You know, cause he got a hundred some patients in here.” (Man in his 70s with high IADL score) “…The nurse ask you all the questions and the doctors (PCP) come in and look at you, you know, talk to you for 10 minutes and then he gone on to the next patient you know, so. … Yeah, well like I said, it change up so often, man you know, this is no longer you know, this is who your doctor is now you know, so the next time I go it may be somebody different. Who knows.” (Man in his 70s with medium IADL score) |

“So for some of them it’s they have family that’s involved with their care but the family might be out of state. And so they actually aren’t necessarily seeing the condition of the patient. And so when you’re trying to communicate to have, say a care plan meeting because their cognitive abilities are declining. You know sometimes [that’s] hard you know to have those discussions because they’re not seeing the patient.” (Nephrologist) |

| Interprofessional communication | “The only thing that they’re (the PCP]) not getting is the lab work from [dialysis]. It doesn’t filter into the [medical record]. … I think that should be, cause I don’t want to be stuck here taking my blood, they’re taking it and then I go over there, and I actually will be stuck because they don’t have the feedback from [dialysis].” (Woman in her 70s with medium IADL score) | “so the primary care person…recently for instance [sent a message through the electronic medical record to] us about a med, but we don’t routinely know when the patient went to their PCP], because they don't… communicate with us you know, and frankly we don't communicate with them. I try to tell them when they tell me they're gonna go see this doctor, that doctor, I say well here, take your run sheet, it has all this good information on it …” (Nephrologist) “We can fax like lab results and treatment sheets and stuff like that to the doctors if they're requesting as long as they have the medical release but typically we don't.” (Nurse) |

Abbreviations: ADL, activities of daily living; IADL, instrumental activities of daily living; PCP, primary care provider.

Mobility

Mobility Assessment

Most patients had a history of falls. Falls were commonly preventable, resulting from postdialysis hypotension, medications, and loss of balance, whereas others were attributed to a predisposing factor (eg, neuropathy). Subsequent to a fall, some patients endorsed using an assistive device to be “careful” when they walk, having physical therapy, and/or home modifications for fall prevention. Despite home modifications, some patients experienced falls and/or described they “couldn’t get up” on their own after a fall. Rounding nephrologists noted limited opportunities to address mobility disability because they do not “see patients walk.” Although nurses often recognized new gait abnormalities, they did not have a plan for addressing the problem.

Transportation Services

Patients described challenges with transportation services for travel to and from dialysis. These shared-ride services often were missed by patients who did not hear the van arrive or were moving too slowly to get to the van in time. One patient expressed frustration that the van did not have a handicap lift and the patient “had to try to get on myself” while the driver “just stands there.” After treatments, some patients experienced long waits for pick-up, leading to missed meals and/or scheduled medication doses. Personnel noted that missed transportation was a common reason for missed treatments.

Medications

Appropriate Prescribing

There were a few patients who received a prescription from a non-nephrology provider with the wrong dose. Example medications were insulin, opioids, gabapentin, and clonidine. A few patients reported “checking” with their nephrologist about new medications to avoid problems, but most did not. Nephrologists similarly expressed concern that they were unable to detect inappropriate prescribing because their patients were receiving medications from several other prescribers so the “med list at [dialysis] is correct a small proportion of the time.”

Medication Management

Patients with medium to high IADL scores reported that they were solely responsible for organizing and taking their medications. Still, some patients reported an instance of taking the wrong dose and experiencing significant side effects (eg, opioid-induced sedation). In contrast, those with low IADL scores had caregivers to prepare their pill box. However, these patients commonly “don’t know what they take” but recognize pills by their color. When patients had limited medication knowledge, personnel found it challenging to reconcile medications unless there was an available caregiver. One dialysis nurse noticed that some patients could not read and/or open pill bottles.

Social Support

IADL Support

Most patients had a family member who provided some degree of IADL support and 1 reported having a home aide. Still, some patients needed assistance with yard work, house cleaning, shopping, and meal preparation. Patients who were in a caregiver role reported that they lacked sufficient support for themselves. Personnel noticed that patients with ADL limitations tend to have difficulty meeting diet and fluid intake recommendations because of difficulty with food preparation and unhealthy dietary choices. Personnel were concerned that older patients who lived alone would have delayed recognition of declining functional status, worsening hygiene, and/or falls. They reported that ADL needs were difficult to meet when “family members are working” and paid caregiving services are inaccessible. One social worker described engaging adult protective services when a patient was “not able to take of care of themselves.”

Emotional Support

One patient described having “anguish” after watching other patients in their dialysis unit decline and die. This patient noted that he talks to others about it but they cannot relate to the experience, so he anticipated a need to see a mood specialist in the future. Another experienced isolation: “some of my friends when I was diagnosed with renal failure, walked away from me.” Others were advised by their doctor to stay positive about their disease because “people who get depressed and worry… get heart attacks.” Personnel recognized that mood changes, such as irritability or tearfulness, seemed to co-occur as with declines in physical health. Personnel endorsed the availability of social workers to address psychological concerns; however, they noticed that some patients with concerning symptoms do not want to talk about their emotions at dialysis.

Communication

Patient-Provider Communication

Some patients reported that PCPs are in a hurry or they do not want to see the patient frequently enough to “get to know me.” Some patients mentioned that visits with their nephrologists during dialysis are also short. Patients reported that these brief visits were used to discuss interactions with other providers (eg, new medication and upcoming procedure). Nephrologists also viewed limited time with patients, along with lack of privacy, as an important reason for these patients to “actually have a PCP.” However, they acknowledged that some patients “think the nephrologist is their PCP.” Dialysis nurses and patient care technicians have more face-to-face time with patients, but patients may not open up about their concerns. If there was a new health concern, personnel found it challenging to reach and engage family, especially if they are working or live in another state.

Interprofessional Communication

Most patients were confident that communication between their physicians (primary care and nephrology) was sufficient, especially when affiliated with the same health system; however, they wished that laboratory data would transfer to avoid repeated needlesticks. In contrast, nephrologists expressed concern that they received incomplete data from external health systems, leading to unmet clinical needs (eg, missed intravenous antibiotic administration with dialysis). Aware of the information gap, one nephrologist advised patients to “take your run sheet” (flow sheet of dialysis prescription, blood pressures, and weights) to their other appointments.

Unique Concerns Raised by Personnel

In the modified nominal group technique, prominent themes (or themes discussed in at least 3 of 4 focus groups or had the highest votes) were consistent with the major themes discussed above: loss of independence, medication problems, and transportation problems. One concern seldom discussed by patients but frequently raised during the nominal group technique was limited finances. Specifically, personnel noted that older patients’ lack of financial resources led to insufficient social support (eg, inability to access costly medications). Another concern discussed more by personnel than patients was their recognition of cognitive decline over time. Although cognition was not routinely assessed, decline was frequently inferred from “seeing people starting to fade,” forgetfulness, changes in hygiene, and difficulty understanding and taking their medications.

Input on Geriatric Model of Care Design

Patients with low IADL scores were receptive to having a care team “review your medications, check in on your ability to do things at home, check in your emotions, check on your thinking ability… and coordinate care with your doctors.” When asked, “what things do you not like about it?” they generally answered “nothing.” However, a few patients with high or medium IADL scores did not see a need for assistance now, but maybe in the future. One patient emphasized that an important benefit would be to help patients “not be depressed.” Personnel mentioned several potential benefits, including an ability to “take care of the whole patient,” improvement in self-management (eg, fluid and diet restrictions), and IADL support. They noted that the advance practice provider and social worker dyad had the potential to improve socialization for “the value of relationships,” patient education, and care coordination such that “patient care be a little bit more consistent because you’ll have that person that can give historically what is going on with that patient.” Some thought it could prevent hospitalizations.

Regarding concerns about implementation, several personnel highlighted that the proposed care team should not visit patients during dialysis because of limited privacy, “hectic pace,” and unexpected complications. A few patients had similar concerns, noting lack of privacy during dialysis, while others were open to the dialysis unit because they are “already here” and wish to avoid additional appointments. Some personnel expressed concern that “the system is overloaded” with patients with unmet needs, and there is limited supply of local resources (ie, personnel or community organizations) to meet those needs. Because a new program could alter workflow and staffing, personnel suggested that it would be necessary to have separate personnel deliver the program. They advised that there would be more adoption of the program if it did not add to their current workload and was seamlessly integrated (eg, incorporated into existing meetings and electronic medical records).

Discussion

We conducted a qualitative study with older adults receiving in-center hemodialysis and dialysis personnel to elucidate how their experiences with geriatric problems highlight unmet care needs. The 4 interrelated unmet needs were: (1) mobility, (2) medications, (3) social support, and (4) communication. In addition, we found that personnel were concerned about the impact of limited finances and cognitive impairment on the older patient’s well-being. Although participants had favorable comments regarding a geriatric model of care, some were cautious about its impact on workflow and potential demand exceeding available resources. Overall, these findings highlight the critical gaps and opportunities for a geriatric model of care tailored for older adults receiving in-center hemodialysis.

Our work builds on prior studies of patient experiences with hemodialysis in identifying areas for improvement in dialysis care. Consistent with a summary of qualitative studies,21 our participants described developing a need for assistance from others, the emotional impact of life receiving dialysis, and the value of relationship and communication with their providers. In 2 studies specific to older adults receiving dialysis,22,23 support with medications or mobility impairment were identified as key needs. Our study builds on this existing knowledge by incorporating dialysis personnel perspectives. Their perspectives not only confirm the unmet needs identified from patient experiences but also reveal how dialysis personnel are often frustrated by their inability to easily identify or intervene when geriatric problems develop. Although the unmet needs are not unique to the older dialysis population, our study demonstrates that these needs persist despite the multidisciplinary dialysis care team and frequent exposure to the health care system.

Our findings inform design elements for adapting GRACE for older adults receiving dialysis. The adaptation would involve a dedicated advance practice provider and social worker dyad conducting geriatric assessment, with emphasis on mobility assessment, medication appropriateness assessment and reconciliation, and age-appropriate depression screening. This dyad could make recommendations to the nephrologist and put those recommendations into action (eg, prescription and arranging consultation). Working closely with the existing dialysis multidisciplinary care team, the dyad could alleviate communication concerns by serving as a liaison between patients, family caregivers, the dialysis unit, and other providers. Because GRACE has demonstrated cost-effectiveness and efficacy in improving quality of life and decreasing hospitalizations for low-income community-dwelling older adults,8,24 there is a need for a pilot study to test the feasibility of GRACE for the dialysis setting.

We provide recommendations for dialysis units to implement changes to address the 4 unmet needs (Box 1). These recommendations include assessment and management of falls risk, medication problems, and social support concerns, as well as standardized approaches to data transfer with PCPs. Implementation of activities in these areas of unmet need is essential to address what matters most to older adults receiving dialysis.25 The Institute for Healthcare Improvement has resources to facilitate quality improvement efforts toward age-friendly health systems.26 Efforts to address these unmet needs have the potential to improve both quality of life and hospitalization rates.

Box 1. Recommendations for Meeting Unmet Needs in Older Adults Receiving Dialysis.

| Unmet Need | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Mobility | Routine home environment assessment for falls Address other fall risk factors (eg, medications, Orthostasis, vision impairment) Promote physical activity Address transportation issues |

| Medications | Routine medication reconciliation and education Systematic reporting of medication additions and changes |

| Social support | Routine age-appropriate depression screening Available counseling and IADL support |

| Communication | Increase frequency/length of visits as needed Enhanced data transfer across health systems |

| Abbreviation: | IADL, instrumental activities of daily living |

Abbreviation: IADL, instrumental activities of daily living.

Our findings should be interpreted with consideration of the following limitations. First, we did not design a study to capture perspectives from caregivers, other health care providers, or a larger sample of dialysis social workers. Second, our study has limited generalizability to other geographic regions and care settings not affiliated with academic medical centers and/or siloed electronic medical records. Patients receiving peritoneal dialysis or home hemodialysis may experience additional unmet needs. Last, responses from patients and personnel may have been constrained because of privacy concerns and/or social desirability bias.

In summary, this qualitative study of experiences of geriatric problems identifies 4 unmet needs among older adults receiving in-center hemodialysis: mobility, medications, social support, and communication. Efforts to meet these needs should provide more age-friendly care to this vulnerable population.

Article Information

Authors’ Full Names and Academic Degrees

Rasheeda Hall, MD, MBA, MHS, Jeanette Rutledge, RN, Cathleen Colón-Emeric, MD, MHS, and Laura J. Fish, PhD.

Authors’ Contributions

Research idea and study design: RH, CC-E, LJF; data acquisition: JR, LJF; data analysis/interpretation: RH, JR, CC-E, LJF; statistical analysis: RH; supervision or mentorship: CC-E, LJF. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision, accepts personal accountability for the author’s own contributions, and agrees to ensure that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Support

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging (Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center [P30AG028716; Drs Hall and Colón-Emeric], and K24AG049077-01A1 [Dr Colón-Emeric], and K76AG059930 [Dr Hall]) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (KL2TR001115; Dr Hall) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This work was also supported by the National Cancer Institute Office of Cancer Centers support of the Duke Cancer Institute’s (P30-CA014236; Dr Fish) Behavioral Health and Survey Research Core. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Research was also supported by American Society of Nephrology Foundation for Kidney Research (Dr Hall), and Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Grant 2015207 (Dr Hall). Funders had no role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Financial Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Andrea Hill for transcription services and Donna Crabtree for formatting assistance.

Peer Review

Received January 14, 2020. Evaluated by 3 external peer reviewers, with direct editorial input from the Editor-in-Chief. Accepted in revised form April 24, 2020.

Footnotes

Complete author and article information provided before references.

Item S1: Patient Interview Guide

Item S2: Personnel Interview Guide

Item S3: Initial Coding Framework

Table S1: Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) Checklist

Supplementary Material

Item S1-S3; Table S1

References

- 1.Berger J.R., Hedayati S.S. Renal replacement therapy in the elderly population. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(6):1039–1046. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10411011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Loon I.N., Wouters T.R., Boereboom F.T., Bots M.L., Verhaar M.C., Hamaker M.E. The relevance of geriatric impairments in patients starting dialysis: a systematic review. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(7):1245–1259. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06660615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blumenthal D., Chernof B., Fulmer T., Lumpkin J., Selberg J. Caring for high-need, high-cost patients - an urgent priority. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(10):909–911. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1608511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Araujo de Carvalho I., Epping-Jordan J., Pot A.M. Organizing integrated health-care services to meet older people’s needs. Bull World Health Organ. 2017;95(11):756–763. doi: 10.2471/BLT.16.187617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall R.K., McAdams-DeMarco M.A. Breaking the cycle of functional decline in older dialysis patients. Semin Dial. 2018;31(5):462–467. doi: 10.1111/sdi.12695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Low L.F., Yap M., Brodaty H. A systematic review of different models of home and community care services for older persons. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:93. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frank C., Wilson C.R. Models of primary care for frail patients. Can Fam Physician. 2015;61(7):601–606. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Counsell S.R., Callahan C.M., Buttar A.B., Clark D.O., Frank K.I. Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders (GRACE): a new model of primary care for low-income seniors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(7):1136–1141. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luker J.A., Worley A., Stanley M., Uy J., Watt A.M., Hillier S.L. The evidence for services to avoid or delay residential aged care admission: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):217. doi: 10.1186/s12877-019-1210-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Becker B.N., Nissenson A.R. Integrated care in ESKD: perspective of a large dialysis organization. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14(3):445–447. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08300718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Porter A.C., Fitzgibbon M.L., Fischer M.J. Rationale and design of a patient-centered medical home intervention for patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;42:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kooman J.P., Kotanko P., Schols A.M., Shiels P.G., Stenvinkel P. Chronic kidney disease and premature ageing. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014;10(12):732–742. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2014.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McAdams-DeMarco M.A., Law A., Salter M.L. Frailty as a novel predictor of mortality and hospitalization in individuals of all ages undergoing hemodialysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(6):896–901. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawton M.P., Brody E.M. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guest G., Bunce A., Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Method. 2006;18(1):59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guest G., Namey E., McKenna K. How many focus groups are enough? Building an evidence base for nonprobability sample sizes. Field Method. 2017;29(1):3–22. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McMillan S.S., Kelly F., Sav A. Using the nominal group technique: how to analyse across multiple groups. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol. 2014;14(3):92–108. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gale N.K., Heath G., Cameron E., Rashid S., Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reid C., Seymour J., Jones C. A thematic synthesis of the experiences of adults living with hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(7):1206–1218. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10561015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han E., Shiraz F., Haldane V. Biopsychosocial experiences and coping strategies of elderly ESRD patients: a qualitative study to inform the development of more holistic and person-centred health services in Singapore. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1107. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7433-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raj R., Brown B., Ahuja K., Frandsen M., Jose M. Enabling good outcomes in older adults on dialysis: a qualitative study. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21(1):28. doi: 10.1186/s12882-020-1695-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Counsell S.R., Callahan C.M., Tu W., Stump T.E., Arling G.W. Cost analysis of the Geriatric Resources for Assessment and Care of Elders care management intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1420–1426. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02383.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall R.K., Cary M.P., Jr., Washington T.R., Colon-Emeric C.S. Quality of life in older adults receiving hemodialysis: a qualitative study. Qual Life Res. 2020;29(3):655–663. doi: 10.1007/s11136-019-02349-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fulmer T., Mate K.S., Berman A. The age-friendly health system imperative. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(1):22–24. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Item S1-S3; Table S1