Summary

In sum, we show that MSCs manipulate the intrinsic activation pathway of CD8+T cells to affect their functional outcome, which results in differential immune activation or suppression.

Keywords: mesenchymal stem cell, EAE, CD8 T cell, autoimmune

Introduction

Stem cell therapy has garnered much attention because of its potential efficacy and widespread applicability to diseases. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are a particularly appealing subset of stem cells, as they may be isolated from multiple tissues of the body and can differentiate into canonical cells of the mesenchyme, including adipocytes, osteoblasts, and chondrocytes [1–3]. As they can be isolated from adult tissues, they do not carry the logistic or ethical difficulties of embryonic stem cells, a feature that has facilitated their entry into clinical trials.

While early work showed the extensive regenerative properties of MSCs, additional studies indicated their possible utility in autoimmune diseases. A number of studies showed that they have immunosuppressive effects: initial studies reported that MSCs inhibited the proliferation of T cells in both antigen-dependent and polyclonally stimulated systems [4, 5]. This suppression was also unrestricted by MHC type [6–8]. MSCs have been shown to reduce the production of IFNγ in CD4+ T cells and to downregulate the cytotoxic program in Tc1 (cytotoxic T lymphocytes, CTL) [9, 10]. Pro-inflammatory Th17 cells failed to develop in the presence of MSCs, though anti-inflammatory regulatory T cell (Treg) development was promoted [11–13] or alternatively left unchanged [14]. MSCs may employ diverse mechanisms in achieving broad immunomodulation, including contact-dependent and soluble factors, such as hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), and indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) [13, 15, 16]. These and other studies led to the evaluation of MSCs in animal models for autoimmune disease, which showed efficacy in models for multiple sclerosis (MS), rheumatoid arthritis, as well as in graft vs. host disease [9, 11, 17, 18]. Currently, a number of clinical trials are being conducted in these and other diseases [19, 20]. Most are still in phase I-II, although some results from the GvHD trials have started to reveal results.

While there have been many reports of benefit, there have also been reports of no improvement and even exacerbation, indicating the potential double-edged nature of these cells [21]. MSCs were shown to be immunogenic in a model of GvHD [22]. There have also been reports of inconsistencies between in vitro findings in which immunosuppression has been achieved and in vivo results in which no beneficial effect was observed, as was the case in an autoimmune neuritis model [23]. Importantly, the ratio of MSCs to T cells was shown to be a critical factor in the axis between immune suppression and immune activation [24], which is a significant finding both in terms of clinical applications and in terms of highlighting the need for elucidation of mechanisms behind the diverse effects of these cells.

One disease in which MSCs are undergoing active investigation is MS, with many studies being conducted in its animal model, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE). MS is a chronic, neuro-inflammatory autoimmune disease of the central nervous system (CNS), in which activated autoreactive T cells gain entry into the CNS and cause demyelination, eventually resulting in axonal degeneration and loss. While many animal models have focused on the role of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells are prominently observed in active acute and chronic MS lesions, even outnumbering CD4+ T cells [25]. These CD8+ T cells are oligoclonally expanded, indicative of antigen-specific responses in the CNS [26]. In MS patients, myelin-reactive CD8+ T cells exhibited increased responsiveness compared to healthy controls, have increased adhesion and migration in a blood-brain barrier system, and are numerically correlative to the extent of axonal damage in the patient [27–30]. Finally, cytotoxic T cells can directly kill oligodendrocytes and neurons in culture and can be microscopically observed with their cytotoxic granules polarized towards these cells [31, 32]. CD8+ T cells in MS lesions exhibit the Tc1 and IL-17A-producing Tc17 effector phenotypes, similar to CD4+ T cells [33]. Animal models to investigate the role of CD8+ T cells have been established and have shown the important role that this subset of cells can play in disease and their potential as a therapeutic target [34]. We thus sought to evaluate the effects of MSCs on subsets of CD8+ T cells in vitro and determine their impact on the progression of EAE induced with a CD8+ T cell-targeted antigen. In the present article, we show that MSCs differentially affect the activation and cytokine production of CD8+ T cells effector subsets and exacerbate CD8+-initiated MOG37–50 EAE pathogenesis. Our results support and extend those of previous studies indicating that MSCs are a pleiotropic, heterogeneous population of stem cells that have diverse functions and have implications for the context in which the MSCs are therapeutically utilized.

Materials/Methods

MSC in vitro culture.

Murine MSCs were generated by standard procedures: cells were derived from the bone marrow of humerus and long bones from 6–8 week-old female C57BL/6 mice. Isolated bone marrow was cultured in Murine Mesencult medium with stimulatory supplements (StemCell Technologies) in 37°C/ 5% CO2 incubation. After two days of initial culture, non-adherent cells were removed and adherent cells (80–90% confluence) were passaged. Cells were passaged as they reached 90% confluence and evaluated after at least ten passages. MSCs were passaged every 3–4 days, and used until the 21st passage, with maintenance of MSC cell surface phenotype. Human MSCs were purchased from Lonza and used between passages 2–10. Human MSCs were cultured in Lonza Mesenchymal Stem Cell Basal Medium supplemented with MSCGM SingleQuots.

Phenotypic and functional characterization and differentiation of MSCs.

After 10 passages, the cells were characterized by multiple commonly utilized markers for conventional MSCs. Phenotypic antibodies used are as follows: CD45-FITC, CD90-FITC, CD34-PE, CD11c-FITC, CD44-PE, I-Ab-FITC, CD80-FITC, CD11b-PE-Cy7, CD73-PE (all from BD Biosciences) and H-2kb-APC, CD105-PE, Sca-1-FITC, CD9-PE, and CD86-PE (all from eBioscience). All isotype controls were purchased from BioLegend. Flow Cytometry was conducted on a BD FacsCalibur. Standard protocols were conducted to verify the ability of MSCs to differentiate into adipocytes and osteoblasts using Mesencult mouse adipogenic stimulatory supplements and mouse osteogenic stimulatory supplements (StemCell Technologies products), respectively, in IMDM-based media with 10% FBS supplementation. Supplement-to-basal media was at a 1:4 ratio. For both differentiation tests, 2.5×104 MSC were plated per well in 2mL Mesencult media in 6-well plates in 37°C/ 10% CO2 incubation. On day 3, cells were given appropriate differentiation media, with media changes every 3– 4 days. After 2 weeks of culture, cells were stained for adipocytic differentiation with Oil Red O and osteogenic differentiation with Alizarin red. Human MSCs were phenotyped by Lonza as CD105+CD166+CD29+CD44+ > 90% and CD14+CD34+CD45+ <10%.

In vitro T cell polarization.

Spleens were harvested from adult female C57BL/6 mice and naïve CD8+ T cells were enriched using a Mouse CD8+ T Cell Enrichment Kit (Stem Cell Technologies), followed by selection of CD62L+CD8+ T cells using CD62L (L-selectin) Microbeads (Milteny Biotec Inc.). For activation, 5×105 T cells were added to wells containing plate-bound α-CD3 (5μg/mL) and soluble α-CD28 (2μg/mL) in IMDM-based medium in 6-well plates. For polarization, these activated cells were also given skewing cytokines and cytokine-neutralizing antibodies. For Tc1 generation, cells were given IL-2 (5 ng/mL), IL-12 (10 ng/mL) (both from Peprotech) and α-IL-4 (20 μg/mL) (NCI). For Tc17 generation, cells were given IL-6 (20 ng/mL), TGF-β1 (5 ng/mL) (both from Peprotech), IL-23 (20 ng/mL), IL-1β (20ng/mL), (both from R&D Systems), α-IL-4 (20 μg/mL) (NCI) and α-IFNγ (20 μg/mL) (eBioscience). For IL-2 neutralization studies, activated CD8+ T cells ± MSC were given α-IL-2 (eBioscience). For CFSE labeling, 1×106cells/mL were labeled with 2.5 μM CFSE labeling dye (CellTrace CFSE Cell Proliferation Kit, Invitrogen). When used, MSCs were co-cultured at a ratio of MSC: T cell of 1:4.T cells were cultured for 72–120 hours before analysis. For human studies, CD8+ T cells were isolated from normal peripheral blood mononuclear cells using the Human CD8+ T cell Enrichment Kit (StemCell Technologies). For activation, 1×106 T cells were added to wells containing plate-bound α-CD3 (5µg/mL) and soluble α-CD28 (2µg/mL) in IMDM-based medium. When used, human MSCs were co-cultured at a ratio of MSC: T cell of 1:4, and T cells were cultured for 72 hours before analysis.

Intracellular cytokine analysis.

T cells from polarization assays were re-stimulated with 2 μL/mL cells of Cell Stimulation Cocktail (eBioscience), containing PMA/Ionomycin/Brefeldin-A/monensin, for 5 hours at 37°C. Cells were then stained with cell surface and intracellular antibodies using the Foxp3 Staining Buffer Set (eBioscience). Antibodies used for cell analyses were conjugated to FITC, PE, PerCp, or APC, and are as follows: CD4-PE, CD8-PerCp, CD25-FITC, CD44-PE, IFNγ-FITC, Annexin V-APC (from BD Biosciences),7-AAD (BD Pharmingen), granzyme B-FITC, T-bet-APC, Eomes-PE, RORγt-PE, IL-17A-APC (from eBioscience), and CD107-FITC (from BioLegend). For human CD8+ T cells, CD8-PE and IFNγ-PerCp-Cy5.5 (eBioscience) were used. Cells were analyzed on a BD FacsCalibur.

ELISA.

Supernatants from in vitro T cell polarizations with and without MSC were harvested after 15 hours of culture and passed through a 0.22 µm filter. IFNγ and IL-2 cytokine secretions were interrogated using ELISA MAX Standard Mouse IFNγ and IL-2 kits, respectively, according to manufacturer’s protocols (BioLegend).

MOG37–50 EAE Induction, Behavioral Analysis, and ex vivo T cell analysis.

6–7 week old C57BL/6 female mice were purchased from the National Cancer Institute (NCI). For each mouse, 100 µg pure MOG37–50 in complete CFA (8 mg/mL M. tb) was injected in the abdomen subcutaneously on day 0. 250 ng pertussis toxin was administered intraperitoneally on days 0 and 2. For MSC-treated mice, mice were administered 5×106 MSCs or PBS vehicle i.p. on days 3 and 8. Mice were monitored daily by a blinded observer for behavioral EAE symptoms and scored as previously reported [35]. For ex vivo T cell analyses, mice from 14–16 days post EAE-induction were sacrificed, perfused with cold Hank’s buffered saline solution (HBSS), and whole brains were harvested. Brains were dissociated, filtered, and inflammatory infiltrates were isolated in Percoll gradients as previously reported [35]. Inflammatory cells were immediately re-stimulated with Cell Stimulation Cocktail (as described) for 4 hours, stained, and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Statistical Analysis.

All statistics shown were conducted using the GraphPad Prism program (GraphPad, San Diego, CA).

Results

MSC characterization.

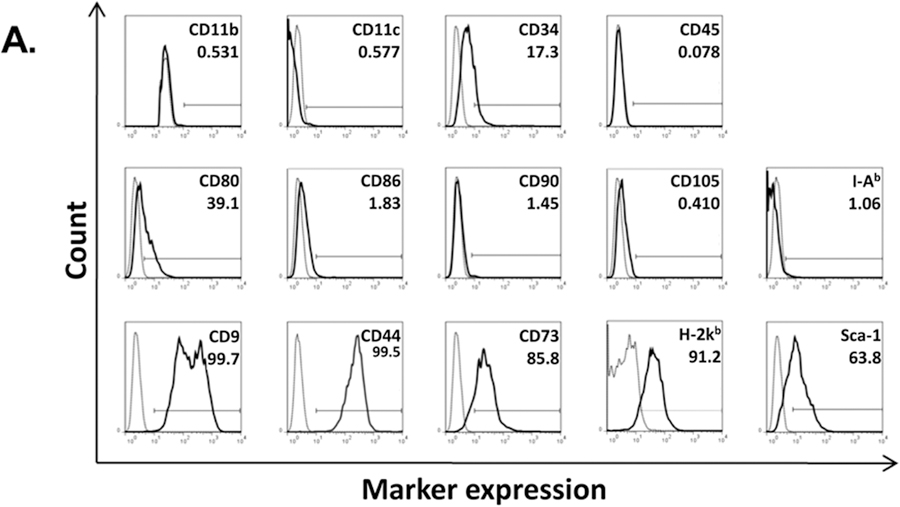

C57BL/ 6 mouse bone marrow from the humerus and long bones was cultured in Mouse Mesencult media for the selective expansion of mesenchymal stem cells. After 6 passages, the cells acquired a uniform fibroblastic morphology and were used for downstream experimentation after 10 passages. To verify MSC characteristics, cells were analyzed for phenotype by FACS using the following markers: CD9+CD44+CD73+MHC-I+Sca-1+ and CD11b−CD11c−CD34−/loCD45−CD80loCD86−/loCD90−CD105−MHC-II−(Fig. 1A). As the hallmark of MSCs is their multipotent differentiation potential, we confirmed their ability to differentiate into adipocytes and osteoblasts (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

MSC characterization. Murine MSCs were stained for a panel of canonical cell surface markers and were identified as CD11b−CD11c−CD34lo/−CD45−CD80loCD86−/loCD90−CD105−MHC-II(I-Ab)− and CD9+CD44+CD73+MHC-I(H-2kb)+Sca-1+ (A). Marker expression is shown as histograms from a representative MSC population. Cell surface markers are shown as solid line graphs and either isotype or unstained cell controls are depicted as dotted line graphs. Next, MSC were confirmed to have the capacity to differentiate into both adipocytes (left column) and osteoblasts (right column). (B)

MSCs affect the development of effector CD8+ T cell subsets differentially.

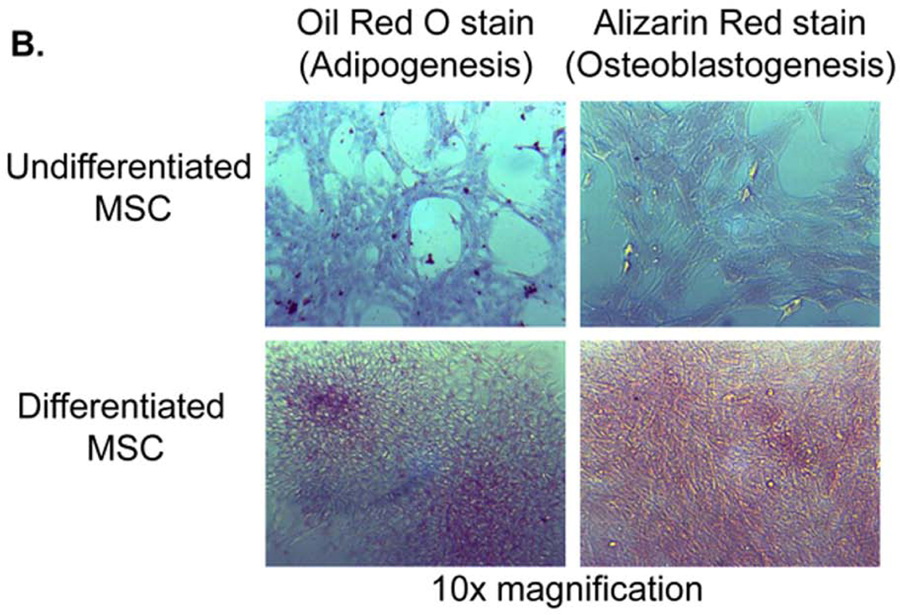

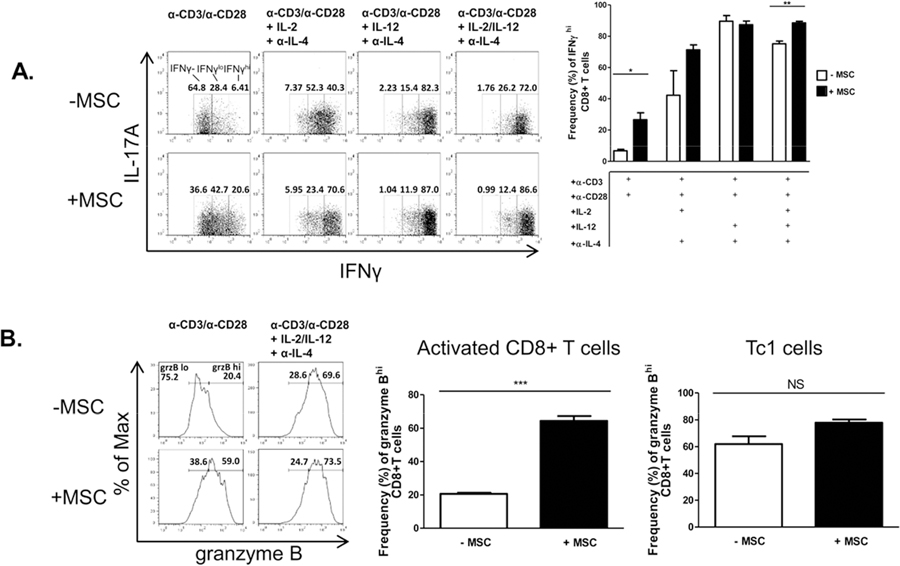

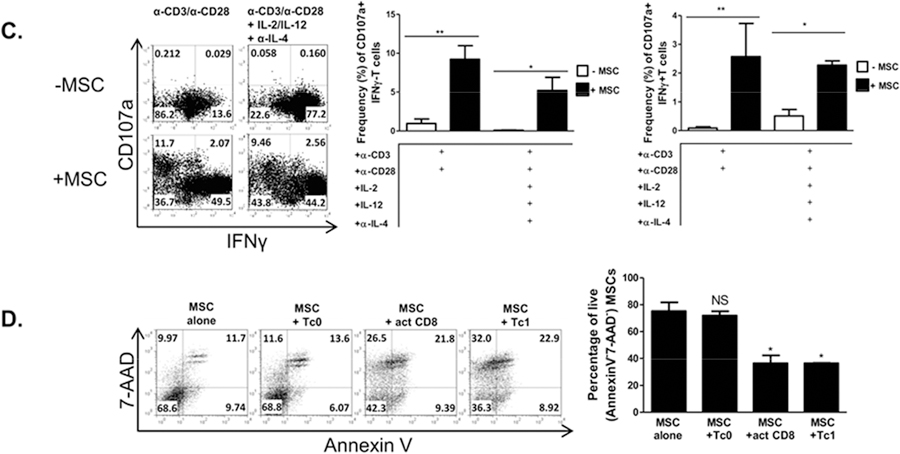

As MS and MOG37–50 EAE pathogeneses involve the generation of multiple CD8+ T cell effector subsets, including IFNγ-producing, cytotoxic Tc1 cells and Tc17 cells [29–35], we next sought to determine whether MSCs could broadly affect the development of non-polarized, IFNγ-producing activated CD8+ T cells, Tc1, and Tc17 cells. Spleen-derived, naïve CD62L+ CD8+ T cells were non-polarized but activated, polarized with IL-2 and IL-12 towards Tc1, and polarized with IL-6 and TGF-β1 ± IL-23 and IL-1β supplementation for Tc17 generation. MSCs were added with the developing T cell subsets in culture and T cells were analyzed 3–5 days post-activation.

Somewhat surprisingly, we found that MSCs significantly increased IFNγ production by non-polarized, activated CD8+ T cells. Tc1 cells, which already produced very high levels of IFNγ as their signature cytokine, were unaffected by MSCs (Fig. 2A). In addition, MSCs enhanced granzyme B production and induced degranulation in activated CD8+ T cells, with enhancement of Tc1 degranulation as well (Fig. 2B,C). Relevant to the clinical setting for these cells, we observed a significant increase in IFNγ production in human CD8+ T cells activated in the presence of human MSCs as well (Supp. Fig. 1).

Figure 2.

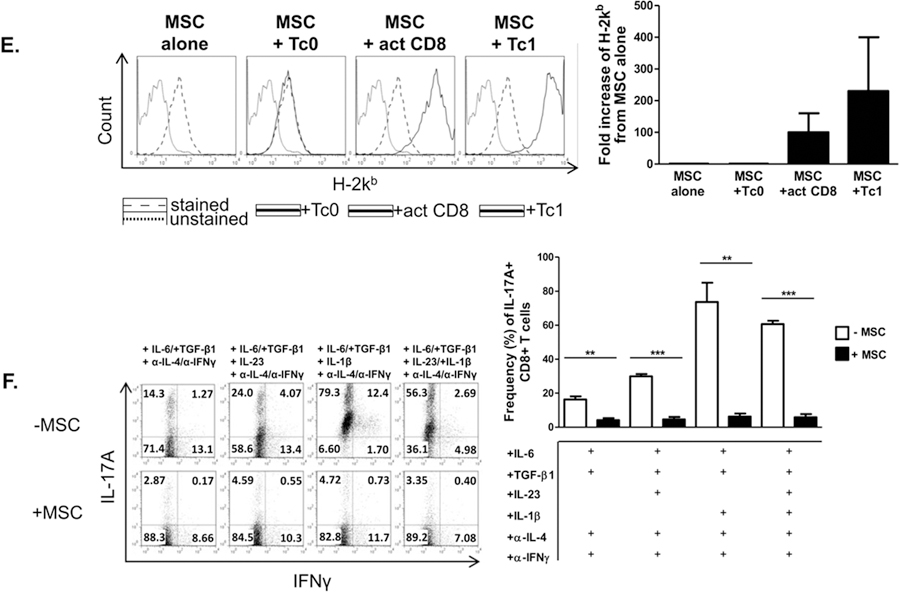

MSCs promote a Tc1-like phenotype in activated CD8+ T cells and suppress the Tc17 program. Naïve CD62L+CD8+ T cells were cultured in the presence or absence of MSCs at a ratio of 4:1, respectively. CD8+ T cells were activated with plate-bound α-CD3 and soluble α-CD28 ± polarizing cytokines and neutralizing antibodies. After 72 hours, T cells were re-stimulated with cell stimulation cocktail for 5 hours, stained, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Shown are representative flow cytometric plots, gated on CD8+ cells, of activated CD8+ and polarized Tc1 (A), granzyme B+ CD8+T cells (B), CD107a+IFNγ- or CD107a+IFNγ+ cells (C), and Tc17 cells (F) in the presence or absence of MSCs. (D) MSCs were cultured in the absence or presence of Tc0, activated CD8+ T cells, or Tc1 cells. After 48 hours, MSCs were harvested and evaluated for viability via flow cytometry. Representative flow plots are gated on CD45− cells (MSCs). (E) MSCs were cultured in the absence or presence of Tc0, activated CD8+T cells, or Tc1 cells. After 15 hours, MSCs were harvested and evaluated for H-2kb via flow cytometry. Representative histograms are gated on CD45− cells (MSCs) and compiled data are from two independent experiments. Data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments. (A-C,F) Compiled percentages of at least 3 experiments are shown per parameter. (D) Compiled percentages of at least 2 experiments are shown. Student t-tests (unpaired, 2-tailed) were conducted for statistical analysis, with statistical differences marked as *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

We next sought to assess the bidirectional effects of the co-cultured cells. As MSCs increased several cytotoxic parameters in activated CD8+ T cells and Tc1 cells, we explored the possibility that the increased activation of the T cells might prove cytotoxic to the MSCs themselves. Consistent with our findings, we observed that in the presence of this heightened cytotoxic response, MSC apoptosis and death were indeed increased (Fig. 2D). Interestingly, while MSCs express H-2kb at low levels in a steady-state, this molecule’s expression was notably up-regulated when MSCs were cultured with either activated CD8+ T cells and Tc1s, beginning as early as 15 hours post-T cell activation (Fig. 2E). In contrast, MSCs potently inhibited the development of Tc17 cells, even when the culture system was provided with the addition of the expansion-promoting, lineage-stabilizing factors IL-23 and IL-1β (Fig. 2F).

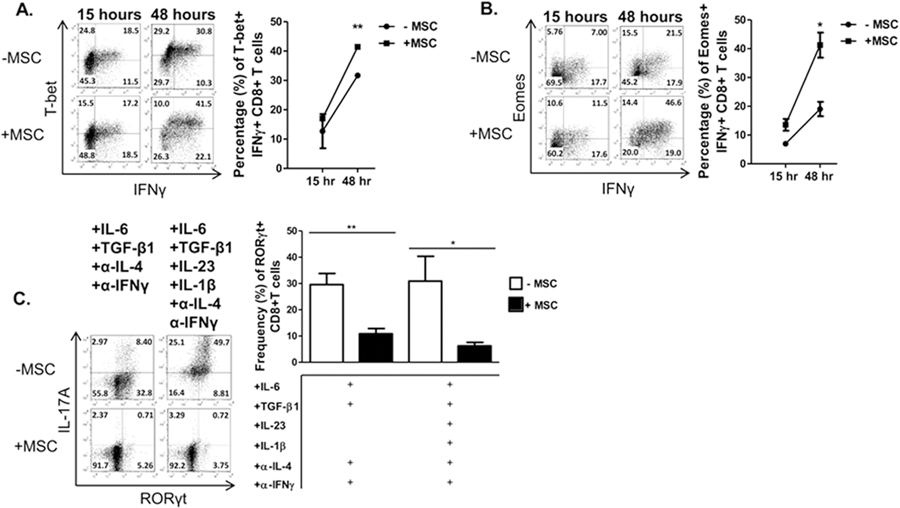

To assess molecular mechanisms by which the MSCs might be modulating T cell polarization, we determined the effects of MSCs on the expression of transcription factors required for cytokine and effector molecule production. The IFNγ-producing and cytotoxic programs are primarily driven by T-bet and Eomesodermin (Eomes), while the IL-17-producing program is governed by the orphan transcription factor RORγt [36, 37]. A time course analysis revealed that the addition of MSCs to activated, non-polarized T cell cultures led to an increasingly higher percentage of expression of both T-bet (Fig. 3A) and Eomes (Fig. 3B), compared to solitary T cell cultures. In Tc17-polarized cultures, MSCs potently inhibited induction of RORγt (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

MSCs enhance Eomes and T-bet induction in IFNγ-producing activated CD8+ T cells but impair RORγT induction in Tc17 cells. Naïve CD62L+CD8+ T cells were cultured in the presence or absence of MSC and activated with plate-bound α-CD3 and soluble α-CD28 ± polarizing cytokines and neutralizing antibodies. T cells were harvested after 15–48 hours (activated CD8+ T cells) or 96 hours (Tc17 cells) and re-stimulated with cell stimulation cocktail for 5 hours, stained, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Shown are representative flow plots and percentages of activated CD8+ T cells for expression of T-bet (A), Eomes (B), and of Tc17 cells for the expression of RORγt (C) in the presence or absence of MSCs. Data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments. Student t-tests (unpaired, 2-tailed) were conducted for statistical analysis, with statistical differences marked as *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

MSC co-culture affects CD8+ T cell activation profiles.

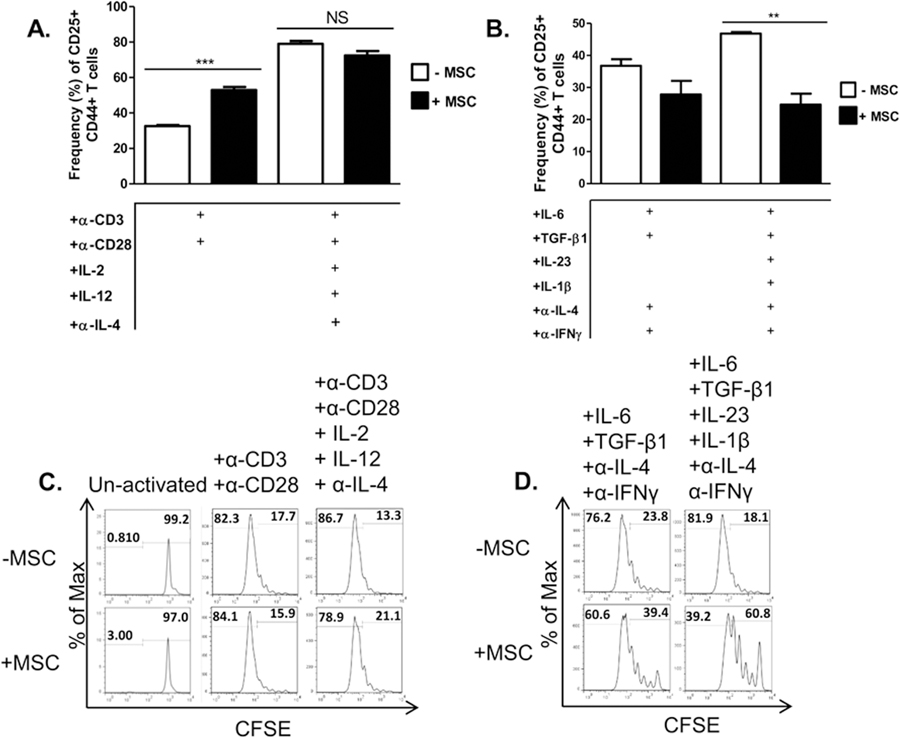

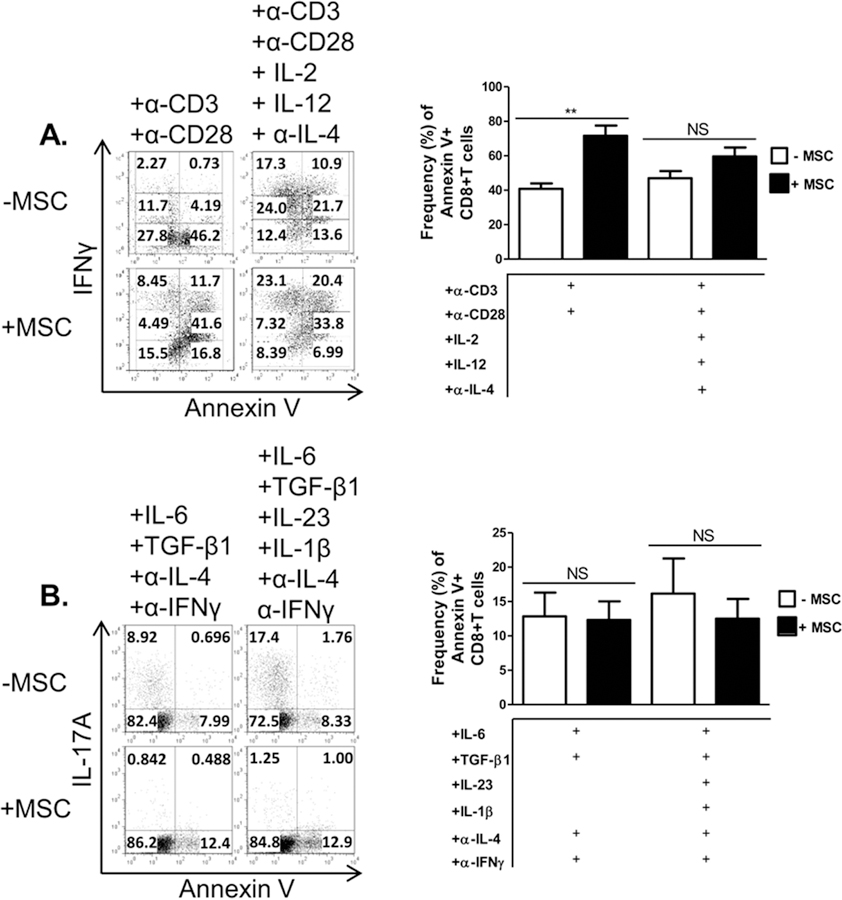

We next assessed the effects of MSCs on activation phenotype, cell proliferation, and apoptosis as markers of T cell activation. Activated T cells co-cultured with MSCs displayed a heightened activation state, marked by an increase in CD25+CD44+ T cells; no difference was noted in the Tc1 condition in which high levels of these markers were expressed already (Fig. 4A). Tc17 co-cultured with MSCs showed a decrease in the percentage of cells expressing both CD25 and CD44, which was even more significant in the presence of IL-23 and IL-1β (Fig. 4B). MSCs had no notable effect on non-specifically activated T cell or Tc1 cell proliferation, but did inhibit proliferation of Tc17 cells(Fig. 4C,D). Interestingly, MSCs increased apoptosis of activated T cells, as evidenced by Annexin V staining. However, MSCs had little effect on Tc17 viability (Fig. 5). In sum, these data show that MSCs differentially modulate effector CD8+ T cells by driving activated CD8++ T cells towards a Tc1-like phenotype, minimally affecting Tc1, and robustly antagonizing Tc17 development.

Figure 4.

Effects of MSCs on T cell activation and proliferation. Naïve CD62L+CD8+ T cells were cultured in the presence or absence of MSC and activated with plate-bound α-CD3/soluble α-CD28 or mouse T-Activator CD3/CD28 Dynabeads (6.25µL/mL) ± polarizing cytokines and neutralizing antibodies. T cells were harvested after 72 hours (activated/Tc1 cells) or 96 hours (Tc17 cells) and re-stimulated with cell stimulation cocktail for 5 hours, stained, and analyzed by flow cytometry.. Shown are percentages of CD25+CD44+CD8+ T cells of activated/Tc1 cells (A) and Tc17 cells (B) in the presence or absence of MSCs. For evaluating proliferation, Naïve CD62L+CD8+ T cells were CFSE labeled before culture. T cell proliferation is shown as histograms of CFSE for un-activated or activated/Tc1 cells (C) and Tc17 cells (D) in the presence or absence of MSCs. Data are representative of at least 3 independent experiments. Student t-tests (unpaired, 2-tailed) were conducted for statistical analysis, with statistical differences marked with statistical differences marked as **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

Figure 5.

MSCs significantly enhance apoptosis in activated CD8+ T cells, but not Tc1 or Tc17 cells. Naïve CD62L+CD8+ T cells were cultured in the presence or absence of MSCs and activated with plate-bound α-CD3 and soluble α-CD28 ± polarizing cytokines and neutralizing antibodies. T cells were harvested after 72 hours (activated/Tc1 cells) or 96 hours (Tc17 cells) and analyzed by flow cytometry. Shown are representative plots and percentages of activated/Tc1 cells and (A) and Tc17 cells (B) in the presence or absence of MSC. Data are representative of at least 2 independent experiments. Student t-tests (unpaired, 2-tailed) were conducted for statistical analysis, with statistical differences marked as **P < 0.01.

MSCs enhance IL-2 production in effector CD8+ T cell co-cultures.

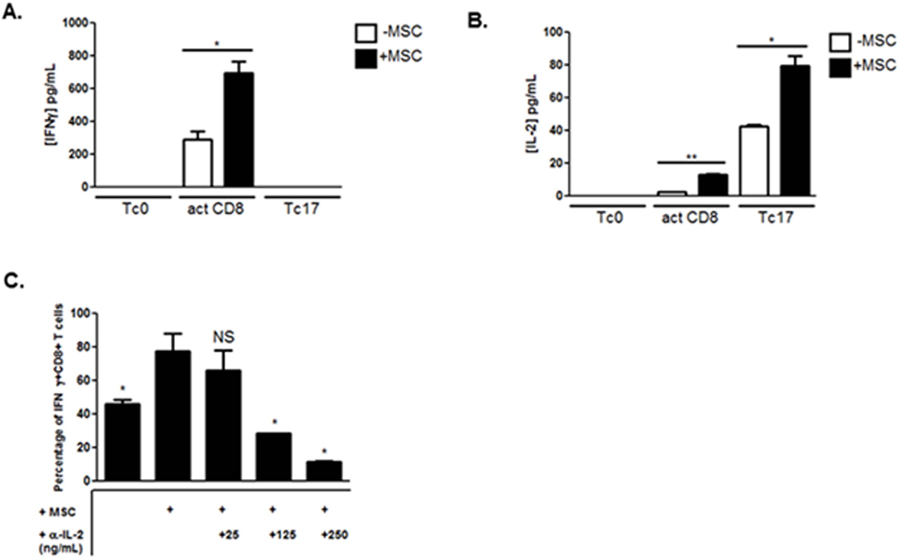

Established molecules known to simultaneously favor IFNγ and inhibit IL-17A production are pro-inflammatory cytokines that induce the Tc1 program, including IL-2 and IFNγ itself [38–40]. Although MSCs promoted IFNγ production in activated CD8+ T cells, no appreciable increase was observed in its production in Tc17 cells co-cultured with MSCs (Fig. 6A). In response to T cell activation, CD8+ T cells produced an initial burst of the cytokine IL-2 [38]. In addition to increasing T cell proliferation and eventual activation-induced cell death (AICD), IL-2 directly constrains IL-17A production via STAT5 signaling [40]. After 15 hours, activated CD8+ T cells and Tc17-polarized cell co-cultures with MSCs produced significantly more IL-2 than their monoculture T cell counterparts (Fig. 6B). No IFNγ or IL-2 secretion was detected in solitary MSC cultures (data not shown). To determine the functional consequence of early MSC-enhanced IL-2 production on effector CD8+ T cells, we neutralized IL-2 in a concentration-dependent manner in co-cultures of activated CD8+ T cells and MSCs. IL-2 neutralization reduced IFNγ production from MSC co-cultured activated CD8+ T cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

MSCs enhance early IL-2 production in effector CD8+ T cell co-cultures. Naïve CD8+ T cells were cultured in the absence or presence of MSCs and activated with plate-bound α-CD3 and soluble α-CD28 ± polarizing cytokines and neutralizing antibodies. After 15 hours of activation, supernatants were harvested, filtered, and evaluated for the secretion of IFNγ (A) and IL-2 (B) by ELISA. (C) Activated CD8+ T cells were cultured alone, with MSCs, or with MSC and neutralizing α-IL-2 antibody at indicated concentrations. After 3 days of activation, T cells were harvested and analyzed for the frequency of IFNγ+ cells via flow cytometry. Data are a combination of 2 independent experiments. For (C), significance is in relation to activated CD8+ and MSC co-culture condition. Student t-tests (unpaired, 2-tailed) were conducted for statistical analysis, with statistical differences marked as *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

MSCs exacerbate MOG37–50 EAE.

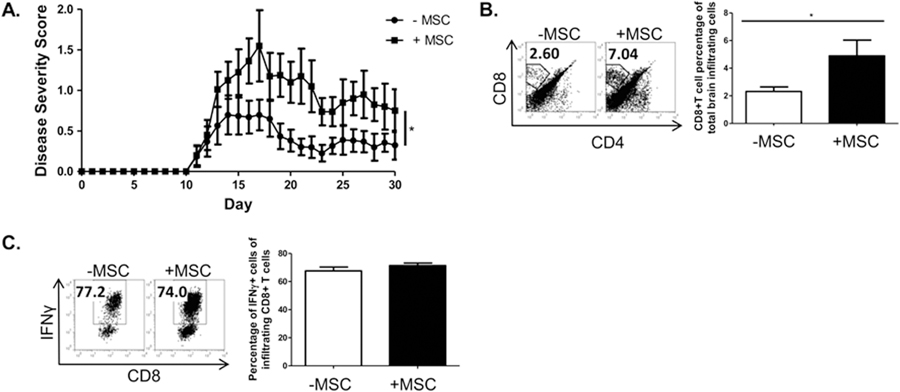

We next sought to evaluate the impact of MSCs on the disease course and myelin-reactive, pathogenic CD8+ T cells generated in the MOG 37–50 model. [31, 33, 34, 41, 42]. We immunized C57BL/6 mice with the CD8+ T cell targeted antigen MOG37–50, then administered two doses of MSCs during the priming phase of disease. Our results revealed an exacerbation of disease in the group treated with MSCs (Fig. 7A). In parallel, we analyzed corresponding CD8+ T cell parameters and found a significant increase in the infiltration of CD8+ T cells into the CNS of the MSC-treated mice (Fig. 7B). During MOG37–50 pathogenesis, CD8+ T cells become activated, migrate to the CNS, and are re-stimulated to produce inflammatory cytokines, such as IFNγ, which promote neuro-inflammation [34]. As expected, in both disease groups, a high percentage of CD8+ T cells in the brains produced IFNγ (Fig. 7C). We did not observe appreciable Tc17 generation (data not shown). Thus MSC- exacerbation of CD8-targeted EAE is associated with an increased frequency of CD8+ T cells in the brain.

Figure 7.

MSC exacerbate CD8-involved MOG37–50 EAE pathogenesis. Female C57BL/6 mice were immunized with MOG37–50 in CFA. On days 3 and 8 post-immunization, mice received either murine MSCs or PBS vehicle. Mice were scored daily in a blinded fashion. Data shown are the combination of two separate studies and are representative of 3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed with the Mann-Whitney U-test, and differences are marked as *P < 0.05 (A). Brains were harvested 14–16 days post-immunization and processed for analysis of infiltrating lymphocytes; lymphocytes were analyzed by flow cytometry. MSC treatment increased the frequency of CD8+ T cells in the infiltrating lymphocytic brain fractions (B), the large majority of T cells in the brains of both groups express IFNγ (C). B,C Data are representative of 3 independent experiments. Student t-tests (unpaired, 2-tailed) were conducted for statistical analysis, with statistical differences marked as *P < 0.05.

Discussion

Mesenchymal stem cells have been recognized for their broad-reaching potential for treating multiple medical conditions as a result of their diverse pleiotropic properties, including tissue regeneration, anti-scarring, angiogenesis, anti-apoptosis, and immunomodulation, especially in engraftment and autoimmune disease settings. Their pliable nature also endows MSCs with a dichotomous potential. The results of our studies indicate a differential effect on subsets of CD8+ T cells, which correlates with a genetic reprogramming of transcription factor expression. Specifically, MSCs suppressed Tc17 generation but augmented the cytotoxic phenotype of activated CD8+ T cells by enhancing intrinsic T cell activation and IL-2 production.

IFNγ-producing, cytotoxic (Tc1) and IL-17-producing (Tc17) CD8+ T cells play crucial roles in the initiation and progression of autoimmune pathologies, yet surprisingly little investigation has addressed the effects of MSCs on their development[33, 43, 44]. Thus we first queried whether MSC-mediated immunosuppression extended to all CD8+ T cell effector subsets in vitro, regardless of phenotype. In the absence of any exogenously added cytokines, MSCs drove activated IFNγ-producing CD8+ T cells towards a more differentiated, cytotoxic T cell-like phenotype marked by increased IFNγ and granzyme B production, and enhanced degranulation. To determine the effects of MSCs on CD8+ T cells, we evaluated two different intensities of polarization: on naïve cells that were either activated only through anti-CD3/anti-CD28, with no polarizing cytokines, which resulted in a weak polarization toward an IFNγ-producing phenotype, or those to which strongly polarized toward Tc1. Our results showed the most significant influence on the non-specifically activated T cells, with the addition of MSCs leading to a significant increase in the production of IFNγ and granzyme B. Addition of the MSCs resulted in the non-skewed T cells reaching an equivalent high level of IFNγ production as those T cells that were strongly polarized towards Tc1. The skewing conditions towards Tc1 alone led to a robust and homogeneous expression of IFNγ, which was not further enhanced by the addition of MSCs, perhaps because of a maximum plateau in cytokine expression. These results suggest that MSCs may exert their greatest effects on IFNγ production under non-polarizing conditions.

In contrast, the addition of MSCs led to a profound inhibition of polarization towards IL-17-producing T cells. We again tested a variety of stimuli, and found that while varying the intensity of polarization dramatically changed the overall production of IL-17, the MSCs potently inhibited IL-17 production regardless of the cytokine milieu. Importantly, we evaluated the contribution of different cytokines that could instruct the MSCs to suppress; in particular, it is possible that MSCs require activation with inflammatory cytokines, specifically with IFNγ and either TNFα or IL-1α/β [45, 46], and IL-1β is thought to be capable of priming MSCs for immunosuppression singly [36, 46]. As activated T cells produce an early burst of IFNγ and TNFα, which could synergize with the exogenously added IL-1β to enhance MSC suppression of Tc17 development, we evaluated additional conditions in which the IL-1β was omitted. The results of those studies showed that IL-17A production was also suppressed when CD8+ T cells were activated in MSC co-cultures with IL-6 and TGF-β1 without IL-1β, again indicating that the specific cytokine milieu was of less relevance than in the Tc1 condition. These results are consistent with a number of previous studies demonstrating that MSCs can inhibit IL-17 production in CD4+ T cells, via a variety of mechanisms [13, 47, 48]. In addition, our results are also consistent with previous notions that MSCs can differentially impact subsets of CD4+ T cells, via a variety of mechanisms [16].

Polarization of naïve T cells and production of accompanying cytokines is differentially mediated by transcription factor expression and activation. In activated and cytokine-induced Tc1 CD8+ T cell development, the cytotoxic program is orchestrated by the action of the T-box transcription factors T-bet and Eomes [36, 38]. We found that MSCs significantly up-regulated the expression of both of these transcription factors in activated CD8+ cells, indicating that their mechanism of enhancement of Tc1 was mediated through genetic reprogramming. During early CD8+ T cell activation, T-bet is usually induced early for IFNγ expression, while Eomes is up-regulated later and promotes sustained cytokine expression [36]. Thus it is likely that the MSC-induced dual, enhanced presence of both of these transcription factors strengthened IFNγ production in the T cells. In parallel, the skewing of naïve T cells towards an IL-17-producing phenotype is mediated through expression of RORγt, the master transcription factor governing the IL-17-producing program, which was previously shown to be both necessary and sufficient for IL-17-polarizing of naïve T cells [37]. We thus determined the impact of the addition of MSCs on the expression of this key cytokine and showed that MSCs potently inhibited RORγt expression, again indicating re-programming as at least a partial mechanism by which MSCs exert their effects.

We next analyzed the impact of MSCs on additional parameters of T cell effector homeostasis that crucially influence their biological and pathological functions. In response to activation cues, T cells proliferate, differentiate, and eventually contract in population size via apoptosis [49]. Activation of naïve T cells is a critical first step in the differentiation process, regardless of the ultimate phenotype. Our results indicated that the effect of MSCs on activation markers correlated with their ultimate effect on polarization, in that non-specifically activated CD8+ T cells exhibited increased co-expression of CD44 and CD25 in co-culture (both markers of activation), while Tc17 cells exhibited decreased co-expression of these molecules with MSC co-culture. Apoptosis of T cells is critical in regulating T cell number and preventing tissue damage. It is also indicative of T cell transit through the activation and effector phases and acquisition of a terminally, differentiated phenotype [49]. MSCs did not enhance apoptosis of T cells polarized towards Tc17, but promoted apoptosis of activated CD8+ T cells, which mirrored the apoptotic profile of fully differentiated Tc1 cells. These data are consistent with the observation that MSCs drive non-cytokine skewed activated CD8+ T cells towards a fully-differentiated Tc1-like phenotype yet potently suppress the Tc17 profile. MSCs exerted minimal influence on the proliferation of IFNγ-producing CD8+ T cells, yet inhibited proliferation of Tc17 cells. These results taken together support the notion of an early reprogramming of gene expression in the T cells by MSCs.

We next investigated potential mechanisms by which MSCs might promote the IFNγ-producing, cytotoxic activated phenotype of CD8+ T cell program while suppressing that of Tc17 cells. Towards this end, we analyzed expression of known key immune-modulatory factors, including IFNγ and IL-2 [38, 40]. Though IFNγ production was dramatically increased in activated CD8+ T cells in the presence of MSCs, it was not secreted in co-cultures of Tc17-polarized cells and MSCs. IL-2 is critical to intrinsic T cell activation and growth but suppresses IL-17 production [38, 40]. Our data demonstrate enhanced IL-2 production from the co-cultures of effector T cell and MSCs compared to the solitary T cell cultures and support the possibility that production of this cytokine may partially account for some of the observed effects of the MSCs.

Recent studies have also reported the pro-inflammatory potential of MSCs and have shown that as these cells interact intimately with their environments, they may adopt pro-inflammatory phenotypes under a range of conditions. Waterman et al. reported that, in response to TLR4 ligation, MSCs exhibit a pro-inflammatory bias via enhancing T cell proliferation, as opposed to TLR3-induced immunosuppressive MSC effects [50]. IL-6 dominates as a molecular switch for MSC immunomodulation in the context of macrophages [51]. MSC production of IL-6 drives macrophages towards an IL-10-producing M2 anti-inflammatory type, while in the absence of IL-6, MSCspromote IFNγ and TNFα production from macrophages, and thus adoption of an M1 phenotype. Furthermore, Li et al. attribute insufficient levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines and low T cell: MSC densities as factors ultimately promoting the pro-inflammatory MSC phenotype [21]. The high sensitivity of MSC to a variety of environmental factors therefore dictates MSC effects on immune responses. Taken together, these data reveal a notable potential for MSCs to promote a pro-inflammatory program in CD8+ T cells in vitro.

MSCs have been investigated in multiple clinical venues, but the dissection of their effects on different aspects of immunity is incomplete. With our in vitro data on the effects of MSCs on CD8+ T cells in mind, we sought to determine whether MSCs influenced CD8+ T cell responses in vivo. While CD8+ T cells are thought to play a significant role in the pathogenesis of MS, most animal models are initiated using a CD4+ -targeted antigen. We therefore tested the effects of disease pathogenesis in an alternate model in which disease is initiated via immunization with a CD8-targeted peptide MS model (MOG 37–50 EAE) [34, 41, 42]. This model of EAE has been shown to generate cytotoxic CD8+ T cells as well as Tc17. While effector CD8+ T cells are also generated in the more traditional CD4+ -targeted model, the MOG 37–50 EAE produces a much higher frequency and the CD8+ response does not become overshadowed by the CD4+ response. In this model system, the MSCs exacerbated disease severity and increased the frequency of CD8+ T cells in the brain, which is consistent with the observed in vitro pro-inflammatory effects. While a number of studies have shown efficacy in some models of disease, our results add to an emerging literature in which MSCs have the potential to have a neutral to negative impact on disease course. For example, in addition to a neutral effect on a model for autoimmune neuritis [23], and in a mouse model of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation, MSCs significantly decreased donor cell engraftment [22, 52]. MSCs may also exert detrimental effects for graft-versus-host-disease patients [52]. Considering the sensitivity of MSC to environmental cytokine milieus, it may be necessary to modify the MSC culture milieu before clinical use in order to achieve an immunosuppressive or immune-stimulatory outcome. Taken together, our data further reveal the pleiotropic nature of MSCs and their pro-inflammatory effects on certain effector CD8+ T cell groups, thereby highlighting the importance of fine tuning their use in experimental and clinical medical settings.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Human MSCs increase IFNγ production in human activated CD8+ T cells. Human CD8+ T cells were added to wells containing plate-bound α-CD3 (5µg/mL) and soluble α-CD28 (2µg/mL) and cultured in the absence or presence of human MSCs. After 72 hours, CD8+ T cells were harvested, re-stimulated with cell stimulation cocktail, stained, and flow cytometrically evaluated for the production of cytokines. For significance, unpaired, 2-tailed student t-tests were used, with *p<0.05.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by The Maryland Stem Cell Research Fund, The National Multiple Sclerosis Society, and The Silverman Foundation.

Grants used: This work was supported by The Maryland Stem Cell Research Fund, The National Multiple Sclerosis Society, and The Silverman Foundation.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors plead no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Pereira RF, et al. , Cultured adherent cells from marrow can serve as long-lasting precursor cells for bone, cartilage, and lung in irradiated mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1995. 92(11): p. 4857–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akahane M, et al. , Scaffold-free cell sheet injection results in bone formation. J Tissue Eng Regen Med, 2010. 4(5): p. 404–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morigi M, et al. , Mesenchymal stem cells are renotropic, helping to repair the kidney and improve function in acute renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2004. 15(7): p. 1794–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Nicola M, et al. , Human bone marrow stromal cells suppress T-lymphocyte proliferation induced by cellular or nonspecific mitogenic stimuli. Blood, 2002. 99(10): p. 3838–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bartholomew A, et al. , Mesenchymal stem cells suppress lymphocyte proliferation in vitro and prolong skin graft survival in vivo. Exp Hematol, 2002. 30(1): p. 42–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aggarwal S and Pittenger MF, Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate allogeneic immune cell responses. Blood, 2005. 105(4): p. 1815–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rasmusson I, et al. , Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit lymphocyte proliferation by mitogens and alloantigens by different mechanisms. Exp Cell Res, 2005. 305(1): p. 33–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krampera M, et al. , Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells inhibit the response of naive and memory antigen-specific T cells to their cognate peptide. Blood, 2003. 101(9): p. 3722–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zappia E, et al. , Mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis inducing T-cell anergy. Blood, 2005. 106(5): p. 1755–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rasmusson I, et al. , Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit the formation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes, but not activated cytotoxic T lymphocytes or natural killer cells. Transplantation, 2003. 76(8): p. 1208–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rafei M, et al. , Mesenchymal stromal cells ameliorate experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inhibiting CD4 Th17 T cells in a CC chemokine ligand 2-dependent manner. J Immunol, 2009. 182(10): p. 5994–6002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghannam S, et al. , Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit human Th17 cell differentiation and function and induce a T regulatory cell phenotype. J Immunol, 2010. 185(1): p. 302–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duffy MM, et al. , Mesenchymal stem cell inhibition of T-helper 17 cell- differentiation is triggered by cell-cell contact and mediated by prostaglandin E2 via the EP4 receptor. Eur J Immunol, 2011. 41(10): p. 2840–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luz-Crawford P, et al. , Mesenchymal stem cells generate a CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cell population during the differentiation process of Th1 and Th17 cells. Stem Cell Res Ther, 2013. 4(3): p. 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bai L, et al. , Hepatocyte growth factor mediates mesenchymal stem cell-induced recovery in multiple sclerosis models. Nat Neurosci, 2012. 15(6): p. 862–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tatara R, et al. , Mesenchymal stromal cells inhibit Th17 but not regulatory T-cell differentiation. Cytotherapy, 2011. 13(6): p. 686–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Papadopoulou A, et al. , Mesenchymal stem cells are conditionally therapeutic in preclinical models of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis, 2012. 71(10): p. 1733–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Polchert D, et al. , IFN-gamma activation of mesenchymal stem cells for treatment and prevention of graft versus host disease. Eur J Immunol, 2008. 38(6): p. 1745–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ren G, et al. , Concise review: mesenchymal stem cells and translational medicine: emerging issues. Stem Cells Transl Med, 2012. 1(1): p. 51–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ankrum J and Karp JM, Mesenchymal stem cell therapy: Two steps forward, one step back. Trends Mol Med, 2010. 16(5): p. 203–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li W, et al. , Mesenchymal stem cells: a double-edged sword in regulating immune responses. Cell Death Differ, 2012. 19(9): p. 1505–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nauta AJ, et al. , Donor-derived mesenchymal stem cells are immunogenic in an allogeneic host and stimulate donor graft rejection in a nonmyeloablative setting. Blood, 2006. 108(6): p. 2114–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sajic M, et al. , Mesenchymal stem cells lack efficacy in the treatment of experimental autoimmune neuritis despite in vitro inhibition of T-cell proliferation. PLoS One, 2012. 7(2): p. e30708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun B, et al. , Regulation of suppressing and activating effects of mesenchymal stem cells on the encephalitogenic potential of MBP68–86-specific lymphocytes. J Neuroimmunol, 2010. 226(1–2): p. 116–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Junker A, et al. , Multiple sclerosis: T-cell receptor expression in distinct brain regions. Brain, 2007. 130(Pt 11): p. 2789–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Babbe H, et al. , Clonal expansions of CD8(+) T cells dominate the T cell infiltrate in active multiple sclerosis lesions as shown by micromanipulation and single cell polymerase chain reaction. J Exp Med, 2000. 192(3): p. 393–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van der Aa A, et al. , Functional properties of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-reactive T cells in multiple sclerosis patients and controls. J Neuroimmunol, 2003. 137(1–2): p. 164–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zang YC, et al. , Increased CD8+ cytotoxic T cell responses to myelin basic protein in multiple sclerosis. J Immunol, 2004. 172(8): p. 5120–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Battistini L, et al. , CD8+ T cells from patients with acute multiple sclerosis display selective increase of adhesiveness in brain venules: a critical role for P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1. Blood, 2003. 101(12): p. 4775–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bitsch A, et al. , Acute axonal injury in multiple sclerosis. Correlation with demyelination and inflammation. Brain, 2000. 123 (Pt 6): p. 1174–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neumann H, et al. , Cytotoxic T lymphocytes in autoimmune and degenerative CNS diseases. Trends Neurosci, 2002. 25(6): p. 313–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jurewicz A, Biddison WE, and Antel JP, MHC class I-restricted lysis of human oligodendrocytes by myelin basic protein peptide-specific CD8 T lymphocytes. J Immunol, 1998. 160(6): p. 3056–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tzartos JS, et al. , Interleukin-17 production in central nervous system-infiltrating T cells and glial cells is associated with active disease in multiple sclerosis. Am J Pathol, 2008. 172(1): p. 146–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ford ML and Evavold BD, Specificity, magnitude, and kinetics of MOG-specific CD8+ T cell responses during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Eur J Immunol, 2005. 35(1): p. 76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skarica M, et al. , Signal transduction inhibition of APCs diminishes th17 and Th1 responses in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol, 2009. 182(7): p. 4192–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cruz-Guilloty F, et al. , Runx3 and T-box proteins cooperate to establish the transcriptional program of effector CTLs. J Exp Med, 2009. 206(1): p. 51–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Korn T, et al. , IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annu Rev Immunol, 2009. 27: p. 485–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cox MA, Harrington LE, and Zajac AJ, Cytokines and the inception of CD8 T cell responses. Trends Immunol, 2011. 32(4): p. 180–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iwakura Y and Ishigame H, The IL-23/IL-17 axis in inflammation. J Clin Invest, 2006. 116(5): p. 1218–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laurence A, et al. , Interleukin-2 signaling via STAT5 constrains T helper 17 cell generation. Immunity, 2007. 26(3): p. 371–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huber M, et al. , A Th17-like developmental process leads to CD8(+) Tc17 cells with reduced cytotoxic activity. Eur J Immunol, 2009. 39(7): p. 1716–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huber M, et al. , IL-17A secretion by CD8+ T cells supports Th17-mediated autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Clin Invest, 2013. 123(1): p. 247–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huseby ES, et al. , Pathogenic CD8 T cells in multiple sclerosis and its experimental models. Front Immunol, 2012. 3: p. 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Skepner J, et al. , Pharmacologic Inhibition of RORgammat Regulates Th17 Signature Gene Expression and Suppresses Cutaneous Inflammation In Vivo. J Immunol, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Ren G, et al. , Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated immunosuppression occurs via concerted action of chemokines and nitric oxide. Cell Stem Cell, 2008. 2(2): p. 141–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singer NG and Caplan AI, Mesenchymal stem cells: mechanisms of inflammation. Annu Rev Pathol, 2011. 6: p. 457–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luz-Crawford P, et al. , Mesenchymal stem cells repress Th17 molecular program through the PD-1 pathway. PLoS One, 2012. 7(9): p. e45272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luz-Crawford P, et al. , A8.11 gilz-dependent activin a production by MSC inhibits TH17 differentiation. Ann Rheum Dis, 2014. 73 Suppl 1: p. A80. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang N and Bevan MJ, CD8(+) T cells: foot soldiers of the immune system. Immunity, 2011. 35(2): p. 161–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Waterman RS, et al. , A new mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) paradigm: polarization into a pro-inflammatory MSC1 or an Immunosuppressive MSC2 phenotype. PLoS One, 2010. 5(4): p. e10088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bernardo ME and Fibbe WE, Mesenchymal stromal cells: sensors and switchers of inflammation. Cell Stem Cell, 2013. 13(4): p. 392–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miura Y, et al. , Mesenchymal stem cells for acute graft-versus-host disease. Lancet, 2008. 372(9640): p. 715–6; author reply 716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Human MSCs increase IFNγ production in human activated CD8+ T cells. Human CD8+ T cells were added to wells containing plate-bound α-CD3 (5µg/mL) and soluble α-CD28 (2µg/mL) and cultured in the absence or presence of human MSCs. After 72 hours, CD8+ T cells were harvested, re-stimulated with cell stimulation cocktail, stained, and flow cytometrically evaluated for the production of cytokines. For significance, unpaired, 2-tailed student t-tests were used, with *p<0.05.