Significance

Modification of instinctive behaviors occurs through experience, yet the mechanisms through which this happens have remained largely unknown. Recent studies have shown that potentiation of aggression, an innate behavior, can occur through repeated winning of aggressive encounters. Here, we show that synaptic plasticity at a specific excitatory input to a hypothalamic cell population is correlated with, and required for, the expression of increasingly higher levels of aggressive behavior following aggressive experience. We additionally show that the amplitude and persistence of long-term potentiation at this synapse are influenced by serum testosterone, administration of which can normalize individual differences in the expression of intermale aggression among genetically identical mice.

Keywords: innate behaviors, long-term potentiation, ventromedial hypothalamus, testosterone

Abstract

All animals can perform certain survival behaviors without prior experience, suggesting a “hard wiring” of underlying neural circuits. Experience, however, can alter the expression of innate behaviors. Where in the brain and how such plasticity occurs remains largely unknown. Previous studies have established the phenomenon of “aggression training,” in which the repeated experience of winning successive aggressive encounters across multiple days leads to increased aggressiveness. Here, we show that this procedure also leads to long-term potentiation (LTP) at an excitatory synapse, derived from the posteromedial part of the amygdalohippocampal area (AHiPM), onto estrogen receptor 1-expressing (Esr1+) neurons in the ventrolateral subdivision of the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMHvl). We demonstrate further that the optogenetic induction of such LTP in vivo facilitates, while optogenetic long-term depression (LTD) diminishes, the behavioral effect of aggression training, implying a causal role for potentiation at AHiPM→VMHvlEsr1 synapses in mediating the effect of this training. Interestingly, ∼25% of inbred C57BL/6 mice fail to respond to aggression training. We show that these individual differences are correlated both with lower levels of testosterone, relative to mice that respond to such training, and with a failure to exhibit LTP after aggression training. Administration of exogenous testosterone to such nonaggressive mice restores both behavioral and physiological plasticity. Together, these findings reveal that LTP at a hypothalamic circuit node mediates a form of experience-dependent plasticity in an innate social behavior, and a potential hormone-dependent basis for individual differences in such plasticity among genetically identical mice.

Brains evolved to optimize the survival of animal species by generating appropriate behavioral responses to both stable and unpredictable features of the environment. Accordingly, two major brain strategies for behavioral control have been selected. In the first, “hard-wired” neural circuits generate rapid innate responses to sensory stimuli that have remained relatively constant and predictable over evolutionary timescales (1, 2). In the second, neural circuits generate flexible responses to stimuli that can change over an individual’s life span, through learning and memory (3, 4).

One common view is that these two strategies are implemented by distinct neuroanatomical structures and neurophysiological mechanisms. According to this view, in the mammalian brain, innate behaviors are mediated by evolutionarily ancient subcortical structures, such as the extended amygdala and hypothalamus, which link specific sensory inputs to evolutionarily “prepared” motor outputs through relatively stable synaptic connections (5). In contrast, learned behaviors are mediated by more recently evolved structures, such as the cortex and hippocampus, which compute flexible input–output mapping responses through synaptic plasticity mechanisms (6). This view has been supported by studies that have revealed distinct anatomical pathways through which olfactory cues evoke learned vs. innate behaviors in both the mouse (7–9) and in Drosophila (reviewed in ref. 10).

This view of distinct neural pathways for innate vs. learned behaviors, however, is challenged by the case of behaviors that, while apparently “instinctive,” can nevertheless be modified by experience. For example, studies in rodents have shown that defensive behaviors such as freezing can be elicited by both unconditional and conditional stimuli, the latter via Pavlovian associative learning (reviewed in ref. 11). In this case, the prevailing view argues for parallel pathways: Conditioned defensive behavior is mediated by circuitry involving the hippocampus, the thalamus, and the basolateral/central amygdala whereas innate defensive responses to predators are mediated by the medial amygdala (MeA)/bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) and hypothalamic structures (reviewed in ref. 12). Although the basolateral amygdala contains representations of unconditioned aversive and appetitive stimuli, these representations are used as the cellular substrate for pairing with conditioned stimuli (13, 14). Despite this segregation of learned and innate defensive pathways, it remains possible that experience-dependent influences on other innate behaviors may involve plasticity at synapses that directly mediate instinctive behaviors.

We have investigated this issue using intermale offensive aggression in mice. While aggression has been considered by ethologists as a prototypical innate behavior (15, 16), animals can be trained to be more aggressive by repeated fighting experience (17–19). The neural substrates and physiological mechanisms underlying this form of experience-dependent plasticity remain unknown. Interestingly, inbred strains of laboratory mice exhibit individual differences in this form of plasticity, with up to 25% of animals failing to respond to aggression training (19). The biological basis of this heterogeneity is not understood. Here, we provide data supporting a plausible explanation for both experience-dependent changes and individual differences in male aggressiveness, one that links physiological plasticity at hypothalamic synapses to aggressive behavior and sex hormone levels.

Results

Aggression Training Increases VMHvlEsr1 Neuron Activity.

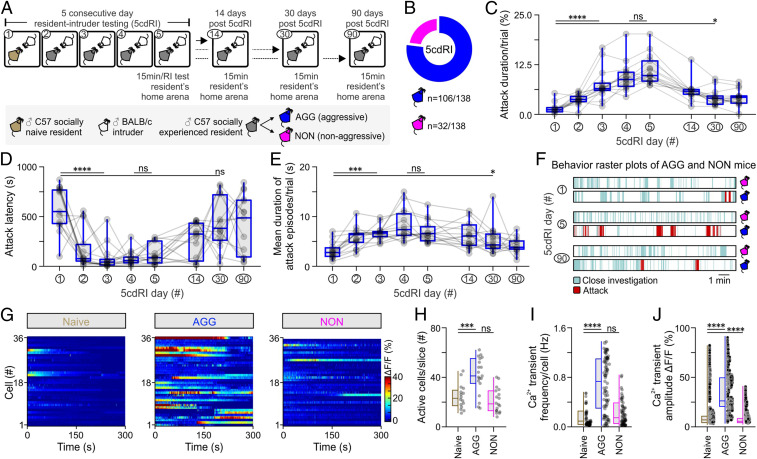

Aggression levels escalate following repeated fighting experience (19, 20), an effect termed here as “aggression training.” Using a five-consecutive-day resident–intruder (5cdRI) assay (Fig. 1A), aggression training was performed on a cohort of C57BL/6 Esr1-Cre mice (n = 138). Most of these animals displayed increased aggression levels that remained significantly elevated, relative to pretraining animals, over a prolonged period of time (maximal period tested, 3 mo) (Fig. 1 C–F). This assay enabled comparison of socially naive, vs. aggressive (AGG), and nonaggressive (NON) mice, the latter of which represented ∼23% of all males tested (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, aggression levels in AGG mice were found to plateau on the fourth and fifth day of the 5cdRI assay (Fig. 1 C–E).

Fig. 1.

Aggression learning alters baseline activity dynamics in VMHvlEsr1 neurons. (A) Schematic of the experimental design using the five-consecutive-day resident–intruder (5cdRI) test, with three follow-up dates, used for the study of the behavioral effect of aggression training. (B) Summary indicative of the number of male animals exhibiting the two distinct aggression phenotypes (n = 138). (C) Quantification of the cumulative duration (in %) of aggression per trial (n = 15 AGG mice per group, Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA with uncorrected Dunn’s post hoc test, P < 0.0001 between day 1 and day 3 of the 5cdRI assay, P = 0.4819 between day 4 and day 5 of the 5cdRI assay, P = 0.0149 between day 1 and day 30). (D) Quantification of attack latency (in seconds) of aggression per trial (n = 15 AGG mice per group, Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA with uncorrected Dunn’s post hoc test, P < 0.0001 between day 1 and day 3 of the 5cdRI assay, P = 0.5602 between day 4 and day 5 of the 5cdRI assay, P = 0.2184 between day 1 and day 30). (E) Quantification of the average attack episode duration (in seconds) per trial (n = 15 AGG mice per group, Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA with uncorrected Dunn’s post hoc test, P < 0.0001 between day 1 and day 3 of the 5cdRI assay, P = 0.3326 between day 4 and day 5 of the 5cdRI assay, P = 0.0209 between day 1 and day 30). (F) Behavior raster plots from AGG and NON mice, at different days of the 5cdRI test. (G) Baseline Ca2+ activity of VMHvlEsr1 neurons recorded ex vivo, in brain slices of socially naive, aggressive (AGG), and nonaggressive (NON) males. (H) Quantification of active cells per slice (n = 16 to 19 brain slices, collected from n = 7 to 9 mice, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test, P = 0.0002 between socially naive and AGG mouse brain slices, P = 0.6358 between socially naive and NON mouse brain slices). (I) Quantification of Ca2+ spike frequency per cell (n = 16 to 19 brain slices, collected from n = 7 to 9 mice, Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA with Dunn’s post hoc test, P < 0.0001 between socially naive and AGG mice, P = 0.3331 between socially naive and NON mice). (J) Quantification of Ca2+ spike amplitude (n = 16 to 19 brain slices, collected from n = 7 to 9 mice, Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA with Dunn’s post hoc test, P < 0.0001 between socially naive and AGG mice, P < 0.0001 between socially naive and NON mice). ns, not significant; *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. ΔF/F was used to calculate Ca2+-dependent changes in fluorescence, where F is the instantaneous fluorescence from the raw ROI time series. In box plots, the median is represented by the center line, the interquartile range is represented by the box edges, the bottom whisker extends to the minimal value, and the top whisker extends to the maximal value.

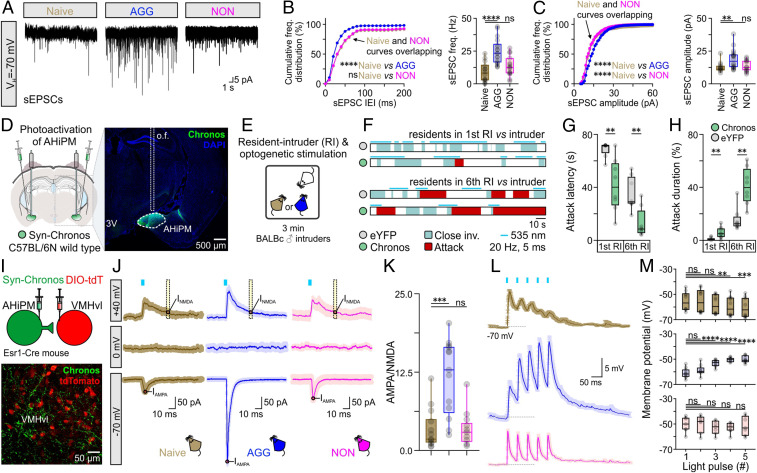

To test whether aggression training involves plasticity in a structure that mediates an innate form of aggression (21), we initially focused on VMHvlEsr1 (estrogen receptor 1-expressing neurons in the ventrolateral subdivision of the ventromedial hypothalamus) neurons, a group of cells highly overlapping with VMHvl progesterone receptor-expressing neurons, both of which are necessary and sufficient for eliciting attack in socially naive animals (22–24). Using brain slice Ca2+ imaging, the average baseline activity of VMHvlEsr1 neurons was found to increase in AGGs but not in NONs, following aggression training (Fig. 1 G–J). Voltage-clamp ex vivo VMHvlEsr1 neuron recordings revealed a significant increase in the frequency and amplitude of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs) in AGG mice (Fig. 2 A–C), relative to socially naive animals. In contrast, voltage-clamp ex vivo VMHvlEsr1 neuron recordings in slices from NON mice revealed an increase in the frequency and amplitude of spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). These observations raised the possibility that synaptic potentiation/depression mechanisms may be present in VMHvlEsr1 neurons (25).

Fig. 2.

AHiPM→VMHvlEsr1 synapses become potentiated following aggression training. (A) Representative recordings of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs) from VMHvlEsr1 neurons, from socially naive, AGG, and NON mice. (B, Left) Cumulative frequency distribution plot of sEPSC IEI in voltage-clamp recordings collected from VMHvlEsr1 neurons from socially naive, AGG, and NON mice (n = 14 to 18 VMHvlEsr1 neuron recordings per group, collected from 8 to 10 mice per group, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, P < 0.0001 between socially naive and AGG mice, P = 0.3454 between socially naive and NON mice). (B, Right) Comparison of sEPSC frequency from voltage-clamp recordings collected from VMHvlEsr1 neurons from socially naive, AGG, and NON mice (n = 14 to 18 VMHvlEsr1 neuron recordings per group, collected from 8 to 10 mice per group, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test, P < 0.0001 between socially naive and AGG mouse brain slices, P = 0.2576 between socially naive and NON mouse brain slices). (C, Left) Cumulative frequency distribution plot of sEPSC amplitude in voltage-clamp recordings collected from VMHvlEsr1 neurons from socially naive, AGG, and NON mice (n = 14 to 18 VMHvlEsr1 neuron recordings per group, collected from 8 to 10 mice per group, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, P < 0.0001 between socially naive and AGG mice, P < 0.0001 between socially naive and NON mice). (C, Right) Comparison of sEPSC frequency from voltage-clamp recordings collected from VMHvlEsr1 neurons from socially naive, AGG, and NON mice (n = 14 to 18 VMHvlEsr1 neuron recordings per group, collected from 8 to 10 mice per group, Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA with uncorrected Dunn’s post hoc test, P = 0.0041 between socially naive and AGG mouse brain slices, P = 0.6712 between socially naive and NON mouse brain slices). (D, Left) Schematic of the experimental design used for optogenetic studies of aggression following photoactivation of AHiPM. (Right) Confocal image indicative of Chronos-eYFP expression in AHiPM. (E) Schematic illustration of the experimental protocol used in AHiPMChronos stimulation experiments. (F) Sample behavior raster plots with in vivo optogenetics and social behavior in the resident–intruder (RI) assay, of socially naive and AGG mice. (G) Quantification of attack latency, in the first and sixth RI trial (n = 8 mice per group, first RI, two-sided Mann–Whitney U test, P = 0.0033 between YFP and Chronos groups, sixth RI, two-tailed unpaired t test, P = 0.0022 between YFP and Chronos groups). (H) Quantification of attack duration, in the first and sixth RI trial (n = 8 mice per group, first RI, two-sided Mann–Whitney U test, P = 0.0079 between YFP and Chronos groups, sixth RI, P = 0.0011 between YFP and Chronos groups). (I, Top) Schematic of the experimental design used for the study of the AHiPM→VMHvl synapse. (Bottom) Confocal image indicative of AHiPM originating processes in VMHvl. (J) Identification of the AHiPM→VMHvl synapse as purely excitatory, and extraction of the AMPA to NMDA ratio in socially naive, AGG, and NON mice (average of n = 13 to 14 neuron recordings from 8 to 9 socially naive, AGG, and NON mice, respectively). (K) Quantification of the AMPA/NMDA ratio (n = 13 to 14, Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA with Dunn’s post hoc test, P = 0.0005 between socially naive and AGG mice, P > 0.9999 between socially naive and NON mice). (L) Synaptic integration in VMHvlEsr1 neurons from socially naive, AGG, and NON mice (average traces of n = 7 to 10 neuron recordings from 7 to 9 mice, respectively). (M) Quantification of the five optically evoked excitatory postsynaptic potentials (oEPSPs) peak amplitude presented in L. (Top) oEPSP amplitude quantification in VMHvlEsr1 neurons recorded from socially naive mice (n = 10 neurons from nine mice, Friedman one-way ANOVA with Dunn’s post hoc test, P > 0.9999 between first and second pulse, P = 0.3587 between first and third pulse, P = 0.0028 between first and fourth pulse, and P = 0.0009 between first and fifth pulse). (Middle) oEPSP amplitude quantification in VMHvlEsr1 neurons recorded from AGG mice (n = 10 neurons from nine mice, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test, P = 0.2935 between first and second pulse, P < 0.0001 between first and third pulse, P < 0.0001 between first and fourth pulse, and P < 0.0001 between first and fifth pulse). (Bottom) oEPSP amplitude quantification in VMHvlEsr1 neurons recorded from NON mice (n = 7 neurons from seven mice, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test, P = 0.9865 between first and second pulse, P = 0.5704 between first and third pulse, P = 0.0751 between first and fourth pulse, and P = 0.9803 between first and fifth pulse). ns, not significant; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. In box plots, the median is represented by the center line, the interquartile range is represented by the box edges, the bottom whisker extends to the minimal value, and the top whisker extends to the maximal value. VH, holding voltage; IEI, inter-event interval, o.f., optic fiber; DIO-tdT, Cre-dependent tdTomato expression.

We first investigated whether potentiation of an excitatory input occurs on these cells. Anatomical studies previously identified a strong purely excitatory input to VMHvlEsr1 cells, which originates anatomically from the posteromedial part of the amygdalohippocampal area (AHiPM) (also termed the posterior amygdala [PA]) (26). In vivo optogenetic activation of AHiPM evoked aggression (Fig. 2 D–H), confirming recent reports (27, 28). We found, moreover, that this effect is amplified in aggression-experienced animals (Fig. 2 D–H). Investigation of the functional connectivity at AHiPM→VMHvlEsr1 synapses in acute slices using optogenetic activation of AHiPM inputs (Fig. 2 I–K) indicated that this projection is entirely excitatory, and at least in part monosynaptic (SI Appendix, Fig. S2), with an absence of any evoked responses at the reversal potential for excitation (holding voltage = 0 mV, Fig. 2 J, Middle Row) and reliable photostimulation-evoked currents at the reversal potential for inhibition (holding voltage = −70 mV, Fig. 2 J, Bottom Row). These observations raised the question of whether potentiation at AHiPM→VMHvlEsr1 synapses underlies the observed increase in the excitatory synaptic input onto VMHvlEsr1 neurons following aggression training.

Plasticity at a Hypothalamic Synapse Following Aggression Training.

At synapses that can undergo long-term potentiation (LTP), the postsynaptic response to stimulation of excitatory presynaptic inputs largely depends on the ratio of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors (29). Therefore, we measured the AMPA/NMDA ratio at AHiPM→VMHvlEsr1 synapses before vs. after aggression training (30, 31). This analysis revealed a significantly higher AMPA/NMDA ratio in AGGs following such training, compared to socially naive and NON mice (Fig. 2K). We also investigated synaptic integration properties (32) in VMHvlEsr1 neurons from socially naive, AGG (trained), and NON mice. We observed depressing/static synaptic integration in socially naive and NON mice, and facilitating synaptic integration in the VMHvlEsr1 neurons of AGG (trained) mice (Fig. 2 L and M).

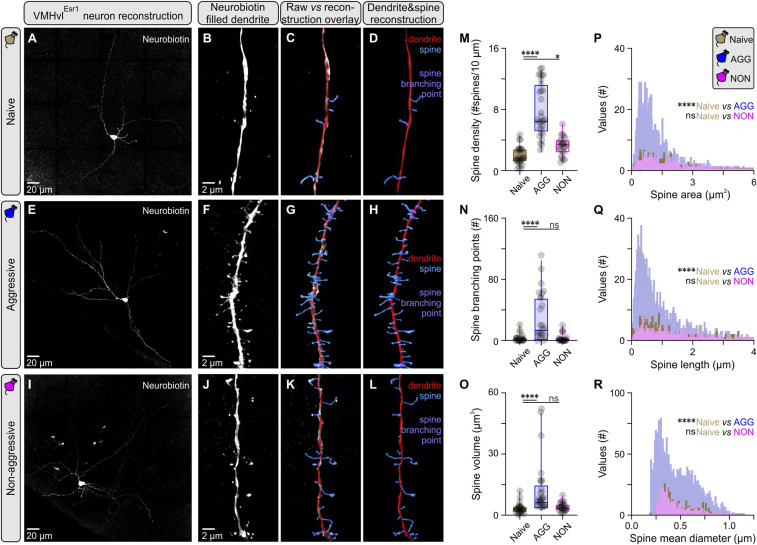

Changes in the AMPA/NMDA ratio and synaptic integration properties are often accompanied by changes in neuronal morphology and dendritic spine complexity, which can be indicative of structural LTP (sLTP) (33). To investigate this possibility, VMHvlEsr1 neurons from which the AMPA/NMDA measurements were acquired were filled with neurobiotin, and superresolution images for reconstruction were obtained using the Airyscanning technique in a ZEISS LSM 880 (34). Analysis of second-order dendritic segments identified a prominent increase in dendritic complexity in VMHvlEsr1 neurons from AGG (trained) mice, in comparison to socially naive and NON mice (Fig. 3 A–L). These changes were reflected in most spine parameters measured, including density, branching points, volume, area, length, and mean diameter (Fig. 3 M–R). However, the principal feature was an increase in the number of short-length spines, suggesting they were newly generated during or after training. While it is not yet clear whether these second-order dendrites receive input from AHiPM, these observations provided morphological evidence of VMHvlEsr1 plasticity following aggression training. We therefore further investigated plasticity using more specific electrophysiological protocols.

Fig. 3.

Increased dendritic spine complexity in VMHvlEsr1 neurons following aggression training. (A) Maximum projection confocal image of a VMHvlEsr1 neuron from a socially naive mouse recorded ex vivo, and filled with Neurobiotin. (B) Three-dimensional (3D) rendering of a second order dendritic segment Airyscan image from the neuron presented in A. (C) Overlay of reconstruction data generated in Imaris against 3D rendering for the dendritic segment presented in B. (D) Reconstructed dendritic segment of a VMHvlEsr1 neuron from a socially naive mouse, with color coding for the dendrite and spines. (E) Maximum projection confocal image of a VMHvlEsr1 neuron from an aggressive (AGG) mouse recorded ex vivo, and filled with Neurobiotin. (F) A 3D rendering of a second order dendritic segment Airyscan image from the neuron presented in E. (G) Overlay of reconstruction data generated in Imaris against 3D rendering for the dendritic segment presented in F. (H) Reconstructed dendritic segment of a VMHvlEsr1 neuron from an AGG mouse, with color coding for the dendrite and spines. (I) Maximum projection confocal image of a VMHvlEsr1 neuron from a nonaggressive (NON) mouse recorded ex vivo, and filled with Neurobiotin. (J) A 3D rendering of a second order dendritic segment Airyscan image from the neuron presented in I. (K) Overlay of reconstruction data generated in Imaris against 3D rendering for the dendritic segment presented in J. (L) Reconstructed dendritic segment of a VMHvlEsr1 neuron from a NON mouse, with color coding for the dendrite and spines. (M) Quantification of spine density in second order dendrites of VMHvlEsr1 neurons from socially naive, AGG, and NON mice (n = 3 to 5 cells per group, n = 1 cell per brain slice per animal, n = 23 to 26 segments analyzed per group, Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA with Dunn’s post hoc test, P < 0.0001 between socially naive and AGG mice, P = 0.0432 between socially naive and NON mice). (N) Quantification of branching points in second order dendrites of VMHvlEsr1 neurons from socially naive, AGG, and NON mice (n = 23 to 26 segments analyzed per group, Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA with Dunn’s post hoc test, P < 0.0001 between socially naive and AGG mice, P = 0.9969 between socially naive and NON mice). (O) Quantification of spine volume in second order dendrites of VMHvlEsr1 neurons from socially naive, AGG, and NON mice (n = 23 to 26 segments analyzed per group, Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA with Dunn’s post hoc test, P < 0.0001 between socially naive and AGG mice, P = 0.4640 between socially naive and NON mice). (P) Frequency distribution plot of spine area, of spines present in second order dendrites in VMHvlEsr1 neurons from socially naive, AGG, and NON mice (n = 3 to 5 cells per group, n = 1 cell per brain slice per animal, n = 402 to 2,365 spines per group). (Q) Frequency distribution plot of spine length, of spines present in second order dendrites in VMHvlEsr1 neurons from socially naive, AGG, and NON mice (n = 402 to 2,365 spines per group). (R) Frequency distribution plot of spine mean diameter, of spines present in second order dendrites in VMHvlEsr1 neurons from socially naive, AGG, and NON mice (n = 402 to 2,365 spines per group). ns, not significant; *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001. In box plots, the median is represented by the center line, the interquartile range is represented by the box edges, the bottom whisker extends to the minimal value, and the top whisker extends to the maximal value.

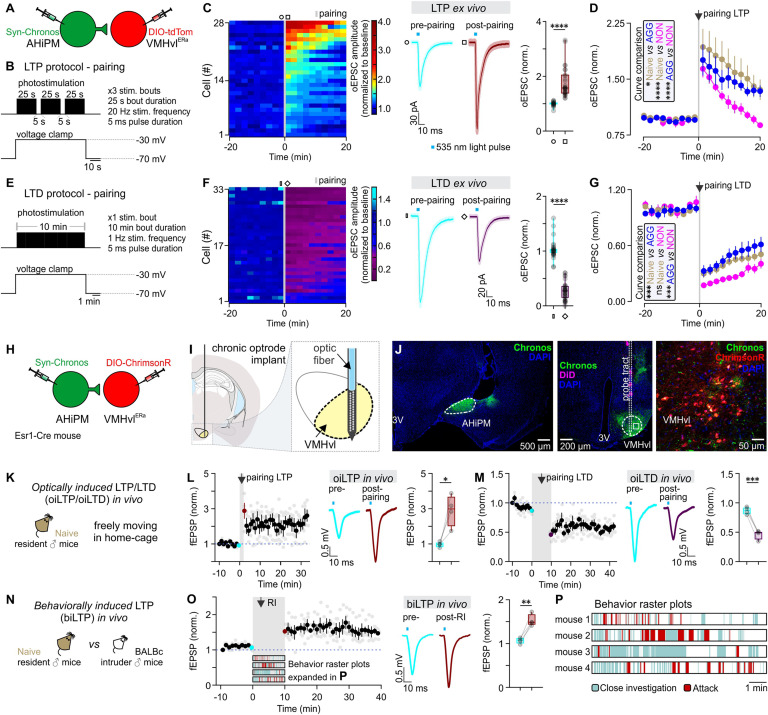

Experimental Induction of LTP and Long-Term Depression at AHiPM→VMHvlEsr1 Synapses.

LTP and long-term depression (LTD) can be experimentally induced in slices from brain areas typically associated with higher cognitive processing, such as the hippocampus (reviewed in ref. 35), but few studies have demonstrated that this can occur in the hypothalamus (36), a site traditionally considered the source of instincts.

To determine whether LTP can be experimentally induced at AHiPM→VMHvlEsr1 synapses ex vivo, we employed acute VMHvl slices and used an optogenetics protocol composed of three bouts of photostimulation of Chronos-expressing AHiPM terminals, during which the postsynaptic VMHvlEsr1 neuron (identified by Cre-dependent expression of tdTomato) was voltage-clamped at a depolarized membrane potential (−30 mV, Fig. 4 A and B). The choice of this Hebbian stimulation protocol was based on our initial finding that combined pre- and postsynaptic depolarization was necessary for induction of potentiation at AHiPM→VMHvlEsr1 synapses (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). The 20 Hz stimulation frequency of AHiPM terminals was chosen based on our previous demonstration that direct optogenetic stimulation of VMHvlEsr1 neurons at this frequency drives action potential firing with 100% spike fidelity ex vivo as well as in vivo, without depolarization block (22), and that it produces reliable synaptic integration in VMHvlEsr1 neurons (Fig. 2 L and M). Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings—composed of 20-min baseline and 20-min follow-up—revealed that the majority of VMHvlEsr1 neurons recorded in slices from socially naive, AGG, and NON mice exhibited synaptic potentiation in response to this manipulation (Fig. 4C). Comparison of the responses with the animals’ aggression phenotypes revealed, however, that the dynamics of the response, including its maximum amplitude and persistence, differed between groups, with synaptic potentiation in slices from NON mice returning to baseline levels within the maximal period tested (20 min, Fig. 4D). Based on the Hebbian conditions required to evoke this form of synaptic potentiation, and the similarity of its features to hippocampal LTP (37), we refer to this form of plasticity as hypothalamic LTP.

Fig. 4.

Induction of LTP and LTD at AHiPM→VMHvlEsr1 synapses ex vivo and in vivo. (A) Schematic of the experimental design used to study the induction of LTP and LTD ex vivo in socially naive, aggressive (AGG) and nonaggressive (NON) mice. (B) Illustration of the experimental protocol used to induce LTP in the AHiPM→VMHvl synapse. (C, Left) Heat map illustrating the magnitude of LTP induction in all recorded VMHvlEsr1 neurons. (Middle) Average current immediately prior to and following the induction of LTP (Middle, n = 28 neurons collected from the three groups—socially naive, AGG, and NON, with n = 6 to 8 mice per group, light color envelope is the SE). (Right) Quantification of the optically evoked excitatory post-synaptic current (oEPSC), prior to and following the induction of LTP (pre- vs. postpairing, n = 28 neurons collected from the three groups—socially naive, AGG, and NON, with n = 6 to 8 mice per group, two-tailed Wilcoxon signed-rank test, P < 0.0001). (D) Identification of differences in amplitude and persistence of LTP in socially naive, AGG, and NON mice (n = 9 neurons for six socially naive mice, n = 10 neurons from eight AGGs, and n = 9 neurons from six NONs, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for curve comparison, P = 0.0183 between socially naive and AGG mice, P < 0.0001 between socially naive and NON mice, and P < 0.0001 between AGG and NON mice). (E) Illustration of the experimental protocol used to induce LTD in the AHiPM→VMHvl synapse. (F, Left) Heat map illustrating the magnitude of LTD induction in all recorded VMHvlEsr1 neurons. (Middle) Average current immediately prior to and following the induction of LTD (Middle, n = 33 neurons collected from the three groups—socially naive, AGG, and NON, with n = 8 mice per group, light color envelope is the SE). (F, Right) Quantification of the oEPSC, prior to and following the induction of LTD (pre- vs. postpairing, n = 33 neurons collected from the three groups—socially naive, AGG, and NON, with n = 8 mice per group, two-tailed Wilcoxon signed-rank test, P < 0.0001). (G) LTD dynamics in the three groups (n = 12 neurons for eight socially naive mice, n = 10 neurons from eight AGGs, and n = 11 neurons from eight NONs, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for curve comparison, P = 0.0002 between socially naive and AGG mice, P > 0.9999 between socially naive and NON mice, and P = 0.0008 between AGG and NON mice). (H) Schematic of the experimental design used to study the induction of LTP and LTD in vivo in socially naive mice. (I) Schematic illustration of the target coordinates of the optrode used to record local field potentials in VMHvl. (J, Left) Representative confocal image of Chronos-eYFP expression in AHiPM. (Middle) Representative confocal image of the silicon probe tract targeted to VMHvl. (Right) High magnification confocal image of VMHvl. (K) Illustration of the experimental design used to induce LTP or LTD in the AHiPM→VMHvl synapse in vivo. (L, Left) Plot of the average of four experiments from four mice of field EPSP slope (normalized to baseline period) before and after optically induced LTP (oiLTP). (Middle) In vivo average field response prior to and following the induction of LTP. (Right) Quantification of optically induced fEPSPs, prior to and following the induction of LTP (pre- vs. postpairing, n = 4 mice per group, two-tailed paired t test, P = 0.0283). (M, Left) Plot of the average of four experiments from four mice of fEPSP slope (normalized to baseline period) before and after oiLTD. (Middle) In vivo average field response prior to and following the induction of LTD. (Right) Quantification of optically induced fEPSPs, prior to and following the induction of LTD (pre- vs. postpairing, n = 4 mice per group, two-tailed paired t test, P = 0.0007). (N) Illustration of the experimental design used to test the behavioral induction of LTP. (O, Left) Plot of the average of four experiments from four mice of fEPSP slope (normalized to baseline period) before and after behaviorally induced LTP (biLTP). (Middle) In vivo average field response prior to and following the behavioral induction of LTP. (Right) Quantification of optically induced fEPSPs, prior to and following social behavior experience in a socially naive mouse (pre- vs. postpairing, n = 4 mice per group, two-tailed paired t test, P = 0.0071). (P) Illustration of the behaviors expressed in the resident–intruder assay from socially naive mice used for the in vivo study of hypothalamic LTP. ns, not significant; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. In box plots, the median is represented by the center line, the interquartile range is represented by the box edges, the bottom whisker extends to the minimal value, and the top whisker extends to the maximal value.

We also investigated whether AHiPM→VMHvlEsr1 synapses can also express long-term synaptic depression (LTD), using a longer stimulation protocol for activating AHiPM terminals (10 min continuous stimulation at 1Hz, Fig. 4E). Similar to the case of LTP, most VMHvlEsr1 neurons expressed LTD of varying amplitude and dynamics, in a manner that varied with the animals’ aggression phenotypes (Fig. 4 F and G). Interestingly, VMHvlEsr1 cells from NON mice expressed higher amplitude LTD (Fig. 4G) than cells from other groups.

These observations raised the question of whether LTP and LTD can be induced at AHiPM→VMHvlEsr1 synapses in behaving animals by optogenetic stimulation or aggression training. For optogenetic induction of LTP, we simultaneously depolarized both pre- and postsynaptic terminals using different opsins with an overlap at 535 nm (38): Chronos in AHiPM and ChrimsonR in VMHvlEsr1 neurons (Fig. 4H). Chronic implantation of a silicon probe optrode in the VMHvl (Materials and Methods) (39) allowed the detection of optically induced LTP or LTD as a change in AHiPM stimulation-evoked local field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs, Fig. 4 I–K). Application of the Hebbian protocol in socially naive, freely moving mice led to the robust expression of LTP in VMHvl (Fig. 4L) while the 10-min long stimulation at 1 Hz led to robust expression of LTD (Fig. 4M). Although VMHvlEsr1 neurons in silicon probe recordings were identified by optogenetic photo-tagging of postsynaptic cells, we cannot exclude that other classes of VMHvl neurons contribute to the recorded fEPSPs.

To investigate whether LTP can be behaviorally induced in vivo, fEPSPs were monitored during a 10-min baseline period and then daily following aggression training, using optogenetic test pulses to briefly activate AHiPM terminals. Indeed, LTP (measured as an increase in fEPSP amplitude) was induced in VMHvlEsr1 neurons immediately after aggression (Fig. 4 N–P, n = 4 mice tested). Notably, the behavioral induction of LTP (Fig. 4O) led to a persistent change in the amplitude of the fEPSP. This might suggest a lack of an early- vs. late-phase distinction in LTP at AHiPM→VMHvlEsr1 synapses, in contrast to LTP in the hippocampus and the amygdala (40).

The above findings identified hypothalamic synaptic plasticity, and specifically LTP and LTD, as mechanisms that can alter VMHvlEsr1 neuronal excitability and which are correlated with behavioral plasticity. Next, we sought to address whether LTP or LTD play a causal role in the behavioral effect of aggression training.

LTP Facilitates and LTD Inhibits Potentiation of Aggression Following Training.

To address whether LTP at AHiPM→VMHvlEsr1 synapses can influence the expression of aggressive behavior in inexperienced animals, we optogenetically induced LTP in vivo in socially naive, solitary mice. The AHiPM of Esr1-Cre mice was transduced with Chronos or YFP while VMHvlEsr1 neurons were transduced with Cre-dependent ChrimsonR or mCherry (Fig. 4H and SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). The effects of these manipulations were investigated behaviorally, not physiologically; therefore, silicon probes were not implanted.

Following the application of the optogenetic LTP induction protocol over three consecutive days in the absence of any social experience, the RI test was performed on the fourth day without optogenetic manipulations (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). The opsin-expressing mice exhibited significantly elevated levels of aggression, measured as an increase in attack duration, number of attacks per trial, and a decrease in attack latency, in comparison to YFP-expressing control mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 C–G). These data indicate that the experimental induction of LTP at AHiPM→VMHvlEsr1 synapses in vivo can increase aggressiveness in the absence of social experience.

We investigated next whether optogenetically evoked LTP or LTD can modify the effects of aggression training (Figs. 4 K–M and 5A). To determine whether LTP could facilitate aggression training, the LTP induction protocol was delivered at the end of each RI trial, in both the control (XFP-expressing) and LTP (opsin-expressing) groups. In a separate experiment, the LTD induction protocol was delivered at the end of each RI trial in both the control and opsin-expressing groups (Fig. 5B). Application of LTD is expected to override any endogenous LTP that may have occurred (41); therefore, if LTP is required in vivo for the behavioral effect of aggression training, then LTD induction should diminish this effect. As in Fig. 1A, smaller size BALB/c intruders were used as intruders in the RI assay to increase the expression of aggression by C57BL/6NEsr1-Cre resident mice (Fig. 5C). Aggression levels were recorded and analyzed on each day of the 5cdRI assay (i.e., 24 h following the previous LTP or LTD manipulation), with the exception of day 1.

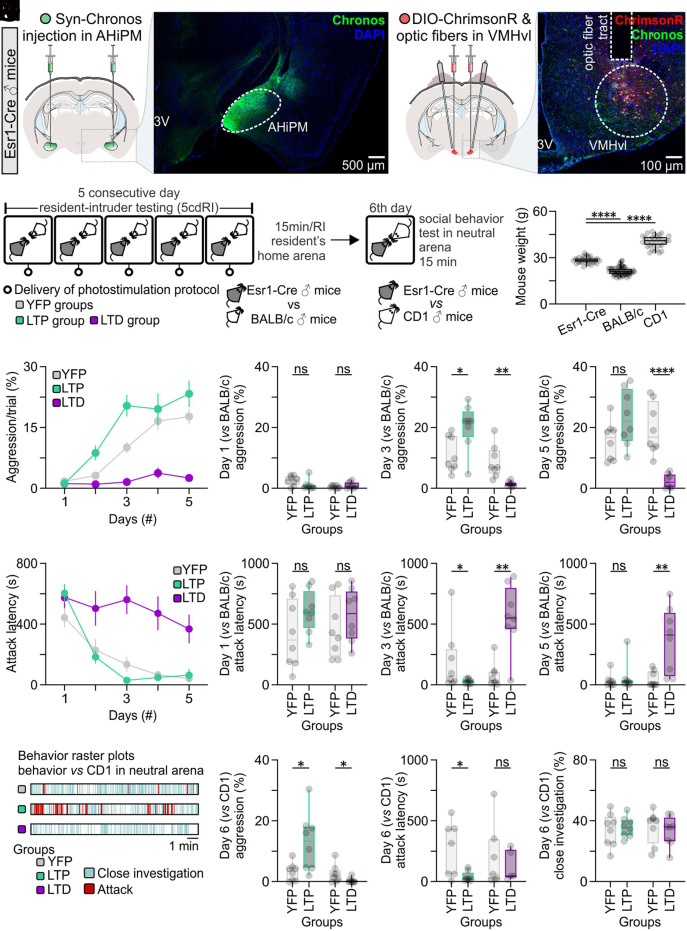

Fig. 5.

Optogenetic induction of LTP or LTD at AHiPM→VMHvlEsr1 synapses in vivo facilitates or abolishes, respectively, the effect of aggression training. (A, Left) Representative confocal image and schematic indicative of ChrimsonR expression in VMHvlEsr1 neurons, eYFP terminals of the AHiPM→VMHvl projection, and the optic fiber tract terminating above VMHvl. (Right) Representative confocal image and schematic indicative of Chronos-eYFP expression in AHiPM. (B) Schematic of the experimental design used to identify whether LTP and LTD have an impact on aggression training. (C) Weight measurements of the mice which were used in the protocol; specifically, the Esr1-Cre mice were used as residents, the BALB/c as intruders, and the CD1 as novel conspecifics in a novel/neutral arena (n = 32 to 64 mice per group, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test, P < 0.0001 between Esr1-Cre and BALB/c mice, P < 0.0001 between Esr1-Cre and CD1 mice). (D) Quantification of aggression levels expressed during a trial throughout the 5cdRI test in the YFP (control), LTP, and LTD groups. (E) Quantification of aggression levels on the first day of the 5cdRI test (n = 8 mice per group, two-tailed unpaired t test, P = 0.1049 between YFP and LTP groups, P = 0.2304 between YFP and LTD groups). (F) Quantification of aggression levels on the third day of the 5cdRI test (n = 8 mice per group, two-tailed unpaired t test, P = 0.0162 [observed power = 0.989, Cohen’s D = 0.7979, difference between means = 9.13 ± 3.34%, 95% CI = 1.966 to 16.29] between YFP [lower 95% CI = 6.452, higher 95% CI = 16.06] and LTP [lower 95% CI = 14.12, higher 95% CI = 26.65] groups, P = 0.0017 between YFP and LTD groups). (G) Quantification of aggression levels on the fifth day of the 5cdRI test (n = 8 mice per group, two-tailed unpaired t test, P = 0.0777 between YFP and LTP groups, P < 0.0001 between YFP and LTD groups). (H) Quantification of attack latency throughout the 5cdRI test in the YFP (control), LTP, and LTD groups. (I) Quantification of attack latency on the first day of the 5cdRI test (n = 8 mice per group, two-tailed unpaired t test, P = 0.1406 between YFP and LTP groups, P = 0.3688 between YFP and LTD groups). (J) Quantification of attack latency on the third day of the 5cdRI test (n = 8 mice per group, two-sided Mann–Whitney U test, P = 0.0415 [observed power = 0.999, Cohen’s D = 0.6072, difference between means = 159.40 ± 90.79 s, 95% CI = −378.8 to 60.04] between YFP [lower 95% CI = −21.05, higher 95% CI = 407.0] and LTP [lower 95% CI = 16.54, higher 95% CI = 50.56] groups, P = 0.0019 between YFP and LTD groups). (K) Quantification of attack latency on the fifth day of the 5cdRI test (n = 8 mice per group, two-sided Mann–Whitney U test, P = 0.5054 between YFP and LTP groups, two-tailed unpaired t test, P = 0.0052 between YFP and LTD groups). (L) Representative behavior raster plots of YFP, LTP, and LTD mouse behavior in a novel arena toward a novel CD1 conspecific. (M) Quantification of aggression levels on the sixth day against a CD1 male (n = 8 mice per group, two-tailed unpaired t test, P = 0.0387 [observed power = 0.999, Cohen’s D = 0.8980, difference between means = 9.816 ± 3.864%, 95% CI = 0.6784 to 18.95] between YFP [lower 95% CI = 0.8293, higher 95% CI = 5.768] and LTP [lower 95% CI = 5.190, higher 95% CI = 21.04] groups, two-sided Mann–Whitney U test, P = 0.0295 [observed power = 0.907, Cohen’s D = 0.7357, difference between means = 2.161 ± 1.069%, 95% CI = −4.616 to 0.2938] between YFP [lower 95% CI = 0.1860, higher 95% CI = 5.052] and LTD groups [lower 95% CI = −0.2284, higher 95% CI = 1.144]). (N) Quantification of attack latency on the sixth day against a CD1 male (n = 8 mice per group, two-tailed unpaired t test, P = 0.0328 [observed power = 0.985, Cohen’s D = 1.0431, difference between means = 227.00 ± 82.23 s, 95% CI = 25.81 to 428.2] between YFP [lower 95% CI = 67.01, higher 95% CI = 477.9] and LTP groups [lower 95% CI = 4.196, higher 95% CI = 86.63], two-sided Mann–Whitney U test, P > 0.9999 between YFP and LTD groups). (O) Quantification of close investigation on the sixth day against a CD1 male (n = 8 mice per group, two-tailed unpaired t test, P = 0.6973 between YFP and LTP groups, P = 0.6158 between YFP and LTD groups). ns, not significant; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001. In box plots, the median is represented by the center line, the interquartile range is represented by the box edges, the bottom whisker extends to the minimal value, and the top whisker extends to the maximal value.

Applying LTP or LTD induction protocols in vivo facilitated or diminished the behavioral effect of aggression training, respectively, as reflected by increased aggression/trial (percentage of the total trial duration occupied by aggressive behavior) and decreased attack latency (Fig. 5 D–K). Interestingly, although LTP was found to enhance the behavioral effect of aggression training on the second and third day of the 5cdRI assay, the effect plateaued on days 4 and 5, at a level similar to the control group (see also Fig. 1C), suggesting an effect that can increase the rate but not the extent of learning. In contrast, LTD had a profound inhibitory effect on aggression training, leading to similar aggression levels following day 1 and day 5 of the 5cdRI test (Fig. 5D, two-tailed paired t test, P = 0.0592 between day 1 and day 5 in the LTD group).

We investigated next whether the plateau in the effect of optogenetically evoked LTP following training day 3 is indeed due to a “ceiling effect” in the aggression training paradigm. To do this, we performed a modified RI test following completion of the 5cdRI training routine. On day 6, control or LTP-induced residents were tested in a novel arena against a larger CD1 male intruder (Fig. 5 B and C). Under these conditions, aggressive resident mice are less likely to attack the intruder (42). We reasoned that, if LTP mice reached “ceiling” levels of aggression in the standard 5cdRI assay, using subordinate BALB/c intruders, they might nevertheless show higher aggression toward the CD1 intruders.

Indeed, under these conditions, the 5cdRI/LTP-treated group exhibited significantly higher aggression levels toward CD1 intruders than any other tested group while the control and LTD groups expressed similarly low aggression levels (Fig. 5 L–N). This finding suggests that experimental induction of hypothalamic LTP in VMHvlEsr1 neurons can facilitate attack under modified RI conditions where resident aggressiveness is otherwise reduced, relative to conventional RI assays.

Together these experiments demonstrate a potential role for LTP and LTD in aggression plasticity. We next investigated the basis for individual differences in aggression training among genetically identical mice, by asking whether we could identify any experimental intervention that would allow aggression and/or hypothalamic LTP to be expressed in NON mice.

Testosterone Enables the Expression of Aggression and Hypothalamic LTP in NON Mice.

Levels of testosterone (T) correlate with aggression and dominance in numerous species (43, 44) while the administration of T in female mice, or following castration in male mice, introduces aggression to the animal’s behavioral repertoire (45, 46). As T levels are subject to environmental influences (47), we sought to determine whether individual differences in levels of the hormone were detectable among genetically identical, inbred C57BL/6N mice and, if so, whether they correlated with, and were responsible for, individual differences in the capacity to undergo aggression training.

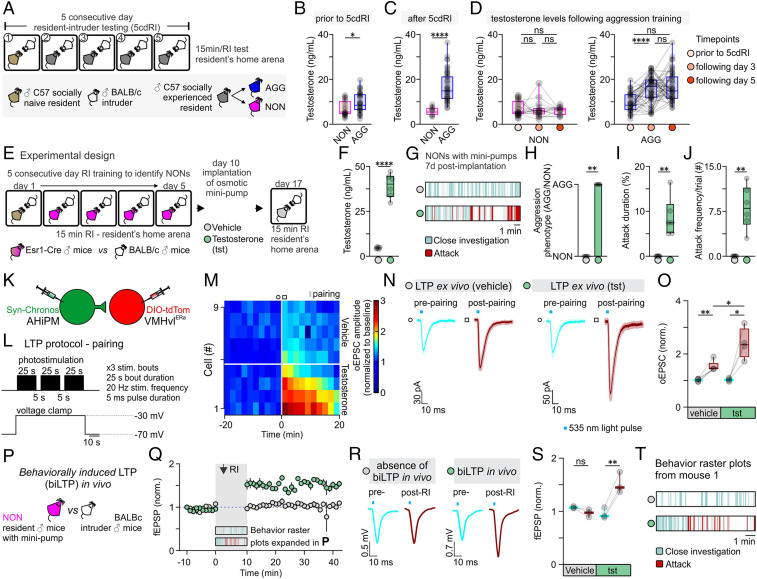

To investigate whether serum T levels differ between NON and AGG mice, we collected blood samples at different time points during the 5cdRI test (Fig. 6 A–D). This experiment revealed retrospectively that, prior to fighting, a small but statistically significant (P < 0.05) difference in serum T was detectable between NON and AGG mice (Fig. 6B). This difference was further accentuated following aggression training (Fig. 6C): Serum T levels remained unaltered in NON mice while they increased in AGG mice (Fig. 6D). Interestingly, the increase in serum T in AGG mice occurred in the first 3 d and was not further accentuated through additional aggression training (Fig. 6D). Together, these data reveal a correlation between individual differences in T and the ability to respond to aggression training in NON vs. AGG mice, as well as between levels of aggressiveness and T levels in AGG mice during training.

Fig. 6.

Testosterone administration leads to the expression of hypothalamic LTP and aggression in previously nonaggressive males. (A) Schematic of the experimental design used to identify aggressive (AGG) and nonaggressive (NON) males, from which tails blood samples were collected for quantification of serum testosterone levels. (B) Serum testosterone levels in NON vs. AGG mice prior to any aggression experience (n = 24 to 36 samples per group, two-sided Mann–Whitney U test, P = 0.0203 between NON and AGG groups). Mice were assigned as NON or AGG, according to whether they expressed aggression on the first day of the 5cdRI test. (C) Serum testosterone levels in NON vs. AGG mice after completion of the 5cdRI test (n = 14 to 46 samples per group, two-tailed unpaired t test, P < 0.0001 between NON and AGG groups). Mice that did not express any aggression/attack behavior throughout the 5cdRI test were assigned to the NON group. All other mice were included in the AGG group. (D, Left) Quantification of serum testosterone levels in NON mice throughout the 5cdRI test (n = 14 to 24 samples per group, Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA with Dunn’s post hoc test, P > 0.9999 between “prior to 5cdRI” and “following day 3,” P > 0.9999 between “prior to 5cdRI” and “following day 5,” and P > 0.9999 between “following day 3” and “following day 5” groups). (Right) Quantification of serum testosterone levels in AGG mice throughout the 5cdRI test (n = 36 to 46 samples per group, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s test, P < 0.0001 between “prior to 5cdRI” and “following day 3,” P < 0.0001 between “prior to 5cdRI” and “following day 5,” and P = 0.7060 between “following day 3” and “following day 5” groups). (E) Schematic of the experimental design used to identify NON mice and perform s.c. testosterone minipump implantation. (F) Serum testosterone levels in control vs. testosterone-treated mice (n = 6 mice per group, two-tailed unpaired t test, P < 0.0001 between vehicle and testosterone). (G) Representative behavior raster plots of vehicle vs. testosterone-treated mice. (H) Quantification of the number of mice that switched aggression phenotype following vehicle vs. testosterone administration (n = 0/6 in the vehicle-treated group vs. n = 6/6 in the testosterone-treated group, two-sided Mann–Whitney U test, P = 0.0022 between vehicle and testosterone). (I) Quantification of attack duration (n = 6 mice per group, two-sided Mann–Whitney U test, P = 0.0022 between vehicle and testosterone). (J) Quantification of attack frequency (number (#) of attacks per trial; n = 6 mice per group, two-sided Mann–Whitney U test, P = 0.0022 between vehicle and testosterone). (K) Schematic of the experimental design used to study the induction and modulation of LTP by testosterone in the AHiPM→VMHvl synapse in brain slices from NON mice. Note that slices were taken from animals that received T injections, but no behavioral training or other social experience. (L) Schematic of the LTP induction protocol, utilizing simultaneous photostimulation of the AHiPM terminals in VMHvl through the opsin Chronos and depolarization of the VMHvlEsr1 neuron through voltage clamp at −30 mV. (M) Heat map illustrating the magnitude of LTP induction in VMHvlEsr1 neurons from vehicle- vs. testosterone-treated mice. (N) Average current immediately prior to and following the induction of LTP in vehicle vs. testosterone conditions (light color envelope is the SE). (O) Quantification of the oEPSC, prior to and following the induction of LTP in vehicle vs. testosterone conditions (prepairing [lower 95% CI = 0.9508, higher 95% CI = 1.084] vs. postpairing [lower 95% CI = 1.274, higher 95% CI = 1.786] in vehicle conditions, n = 5 cells from three mice, two-tailed paired t test, P = 0.0038 [observed power = 0.992, Cohen’s D = 2.704, difference between means = 0.5124 ± 0.0847, 95% CI = 0.2771 to 0.7478], prepairing [lower 95% CI = 0.9349, higher 95% CI = 1.120] vs. postpairing [lower 95% CI = 1.456, higher 95% CI = 3.334] in testosterone conditions, n = 4 cells from three mice, two-tailed paired t test, P = 0.0209 [observed power = 0.889, Cohen’s D = 2.232, difference between means = 1.368 ± 0.3063, 95% CI = 0.3926 to 2.342], postpairing in vehicle [lower 95% CI = 1.274, higher 95% CI = 1.786] vs. testosterone [lower 95% CI = 1.456, higher 95% CI = 3.334] conditions, n = 4–5 cells from six mice, two-tailed unpaired t test, P = 0.0174 [observed power = 0.932, Cohen’s D = 0.6388, difference between means = 0.8652 ± 0.2974, 95% CI = 0.2044 to 1.526]). (P) Schematic of the experimental design used to trigger and record behaviorally induced LTP in vivo in NONs. (Q) fEPSP amplitude over time, prior to and following social behavior in the resident–intruder assay, in vehicle- vs. testosterone-treated NON mice (average fEPSP from n = 3 mice per group). (R) Average fEPSP amplitude immediately prior to and following the expression of social behavior in the resident–intruder assay, in vehicle- vs. testosterone-treated NON mice. (S) Quantification of fEPSP amplitude, prior to and following the induction of LTP in vehicle vs. testosterone conditions (prepairing [lower 95% CI = 1.027, higher 95% CI = 1.123] vs. postpairing [lower 95% CI = 0.7907, higher 95% CI = 1.143] in vehicle conditions, n = 3 mice, two-tailed paired t test, P = 0.1020 [observed power = 0.999, Cohen’s D = 1.6667, difference between means = 0.1081 ± 0.0374, 95% CI = −0.2692 to 0.05303], prepairing [lower 95% CI = 0.7055, higher 95% CI = 1.209] vs. postpairing [lower 95% CI = 1.027, higher 95% CI = 2.012] in testosterone conditions, n = 3 mice, two-tailed paired t test, P = 0.0098 [observed power = 0.786, Cohen’s D = 5.7787, difference between means = 0.5625 ± 0.0562, 95% CI = 0.3207 to 0.8043]). (T) Representative behavior raster plot of the same mouse treated with vehicle and 8 d after with testosterone and used for in vivo electrophysiology experiments. ns, not significant; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001. In box plots, the median is represented by the center line, the interquartile range is represented by the box edges, the bottom whisker extends to the minimal value, and the top whisker extends to the maximal value. In bar graphs, data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

To test whether T levels are causally responsible for the difference in aggressiveness between NON and AGG mice, subcutaneous (s.c.) osmotic minipumps containing T or vehicle were implanted in NON mice identified by their failure to show aggressiveness following 5cdRI training (Fig. 6E). The serum T levels in NONs measured at 7 d post-T minipump implantation were significantly higher than (but within the upper quartile of) the maximum T levels measured in AGG mice (Fig. 6 D and F) (serum T in NONs following T administration through minipump 39.22 ± 2.73 ng/mL, serum T in AGGs following aggression training 16.61 ± 1.01 ng/mL, n = 6 and 46 mice, respectively, two-sided Mann–Whitney U test, P < 0.0001). Strikingly, the administration of exogenous T induced aggression in all NON mice tested (Fig. 6 G–J). We investigated next whether T administration influenced the induction and/or expression of LTP, using ex vivo recordings in acute VMHvl slices from vehicle vs. T-treated NON mice. Using the Hebbian induction protocol, stronger LTP could be elicited in VMHvlEsr1 neurons recorded in slices from T-treated than from control NON mice (Fig. 6 K–O). Thus, T implants facilitate LTP induction ex vivo in NON mice.

An important remaining question was whether LTP was expressed in VMHvlEsr1 neurons in vivo, following aggression training in T-treated NON mice. To address this question, we used the design previously described in Fig. 4 H and N, in which AHiPM was transduced with Chronos, while VMHvlEsr1 cells were transduced with ChrimsonR. A novel BALB/c, small size male intruder was introduced into the NON’s home cage (Fig. 6P). In vehicle-treated mice, social interactions with intruder mice, but no aggression, were observed, and LTP did not occur in vivo, as measured by fEPSP recordings in response to optogenetic stimulation of Chronos-expressing AHiPM terminals (Fig. 6 Q–T). However, T administration through s.c. osmotic minipumps led to the expression of both aggressive behavior and in vivo behaviorally induced LTP, in NON mice (Fig. 6 Q–T).

These findings suggest that individual differences in serum T are responsible, at least in part, for individual differences in the capacity for aggression training among inbred mice. Elevation of serum T in NON mice confers susceptibility to aggression training, as well as the capacity to express strong LTP at AHiPM→VMHvlEsr1 synapses (both ex vivo and in vivo) following aggression training. This observation further strengthens the correlation between the ability to respond positively to aggression training, and the expression of LTP. However, it does not distinguish whether the enhanced LTP in NON mice is directly caused by T treatment, or rather is an indirect effect of the increased aggression promoted by the hormone implants. A schematic summary of the findings is presented in SI Appendix, Fig. S5.

Discussion

Synaptic plasticity mechanisms have been investigated predominantly in hippocampal circuits that mediate spatial learning (48) or in thalamo-amygdalar circuits that mediate Pavlovian associative conditioning (49). Both systems emphasize the role of LTP in allowing flexible neural circuits to mediate adaptive responses on fast timescales, as expected for the recently evolved brain regions in which they operate. By contrast, studies of the hypothalamus have emphasized circuits that mediate innate, evolutionarily ancient survival behaviors, with the expectation that they would be comprised predominantly of relatively stable, hard-wired connections (50–52). The present results demonstrate that LTP and LTD can occur at a hypothalamic synapse important for aggression (27, 28) and that LTP is part of the causal mechanisms through which repeated successful aggressive encounters increase aggressiveness. Moreover, they suggest that individual variation in T levels, taken together with an effect of T to promote LTP at AHiPM→VMHvlEsr1 synapses, may account for differences among genetically identical mice in the ability to respond to aggression training.

The form of hypothalamic LTP described here has subtle but interesting differences from that described in the hippocampus (see extended discussion in SI Appendix). Further investigation of synaptic plasticity mechanisms within neural pathways that control evolutionarily selected, robust survival behaviors may yield new insights into both the physiological and hormonal regulation of such mechanisms, as well as the forms of behavioral plasticity that they ultimately subserve.

Materials and Methods

All experimental procedures involving the use of live animals or their tissues were carried out in accordance with the NIH guidelines and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and the Institutional Biosafety Committee at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). Esr1Cre/+ knock-in mice (22) backcrossed into the C57BL/6N background (>N10) were bred at Caltech. The Esr1Cre/+ knock-in mouse line is available from The Jackson Laboratory (stock no. 017911). Heterozygous Esr1Cre/+ mice were used for all experiments and were genotyped by PCR analysis of tail DNA. Mice used as residents (see 5cdRI assay) were individually housed. All wild-type mice used as intruders in resident–intruder assays and for behavioral experiments were of the BALB/cAnNCrl or Crl:CD1 (ICR) strain (Charles River Laboratories). Health status was normal for all animals. Antibodies, compounds, and the experimental procedures with the coordinates of all injection sites are described in SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. B. Weissbourd and Dr. L. Li for advice on experiments, Dr. Y. Ouadah and Dr. P. Williams for advice during writing of the manuscript, X. Da and J. S. Chang for technical assistance, X. Da and C. Chiu for laboratory management, and G. Mancuso for administrative support. Members of the D.J.A. laboratory are thanked for discussion during the preparation of this manuscript. Confocal imaging was performed in the Biological Imaging Facility, with the support of the Caltech Beckman Institute and the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation. This study was supported by NIH Grant R01 MH070053 (to D.J.A.) and the European Molecular Biology Organization Advanced Long-Term Fellowship 736-2018 (to S.S.). D.J.A. is an investigator of the HHMI.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2011782117/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability.

All data discussed in the paper are available in the main text and SI Appendix. We used standard MATLAB functions and publicly available software indicated in the manuscript for analysis.

References

- 1.Manoli D. S., Meissner G. W., Baker B. S., Blueprints for behavior: Genetic specification of neural circuitry for innate behaviors. Trends Neurosci. 29, 444–451 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ishii K. K., Touhara K., Neural circuits regulating sexual behaviors via the olfactory system in mice. Neurosci. Res. 140, 59–76 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson E. B., Grossrubatscher I., Frank L., Dynamic hippocampal circuits support learning- and memory-guided behaviors. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 79, 51–58 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yavas E., Gonzalez S., Fanselow M. S., Interactions between the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex, and amygdala support complex learning and memory. F1000 Res. 8, 1–6 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sternson S. M., Hypothalamic survival circuits: Blueprints for purposive behaviors. Neuron 77, 810–824 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moscarello J. M., Maren S., Flexibility in the face of fear: Hippocampal-prefrontal regulation of fear and avoidance. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 19, 44–49 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miyamichi K. et al., Cortical representations of olfactory input by trans-synaptic tracing. Nature 472, 191–196 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sosulski D. L., Bloom M. L., Cutforth T., Axel R., Datta S. R., Distinct representations of olfactory information in different cortical centres. Nature 472, 213–216 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Root C. M., Denny C. A., Hen R., Axel R., The participation of cortical amygdala in innate, odour-driven behaviour. Nature 515, 269–273 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amin H., Lin A. C., Neuronal mechanisms underlying innate and learned olfactory processing in Drosophila. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 36, 9–17 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosen J. B., The neurobiology of conditioned and unconditioned fear: A neurobehavioral system analysis of the amygdala. Behav. Cogn. Neurosci. Rev. 3, 23–41 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gross C. T., Canteras N. S., The many paths to fear. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 13, 651–658 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gore F. et al., Neural representations of unconditioned stimuli in basolateral amygdala mediate innate and learned responses. Cell 162, 134–145 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Namburi P. et al., A circuit mechanism for differentiating positive and negative associations. Nature 520, 675–678 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tinbergen N., The Study of Instinct, (Clarendon Press, Oxford, England, 1951), p. 228. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lorenz K., On Aggression, (Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., New York, 1963). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lagerspetz K. M. J., Garattini S., Sigg E. B., Aggression and aggressiveness in laboratory mice. Aggress. Behav., 77–85 (1969). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scott J. P., Fredericson E., The causes of fighting in mice and rats. Physiol. Zool. 24, 273–309 (1951). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stagkourakis S. et al., A neural network for intermale aggression to establish social hierarchy. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 834–842 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Golden S. A. et al., Basal forebrain projections to the lateral habenula modulate aggression reward. Nature 534, 688–692 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin D. et al., Functional identification of an aggression locus in the mouse hypothalamus. Nature 470, 221–226 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee H. et al., Scalable control of mounting and attack by Esr1+ neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamus. Nature 509, 627–632 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang C. F. et al., Sexually dimorphic neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamus govern mating in both sexes and aggression in males. Cell 153, 896–909 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang T. et al., Social control of hypothalamus-mediated male aggression. Neuron 95, 955–970.e4 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alle H., Jonas P., Geiger J. R., PTP and LTP at a hippocampal mossy fiber-interneuron synapse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 14708–14713 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lo L. et al., Connectional architecture of a mouse hypothalamic circuit node controlling social behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 7503–7512 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zha X. et al., VMHvl-projecting Vglut1+ neurons in the posterior amygdala gate territorial aggression. Cell Rep. 31, 107517 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamaguchi T. et al., Posterior amygdala regulates sexual and aggressive behaviors in male mice. Nat. Neurosci. 23, 1111–1124 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Myme C. I., Sugino K., Turrigiano G. G., Nelson S. B., The NMDA-to-AMPA ratio at synapses onto layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons is conserved across prefrontal and visual cortices. J. Neurophysiol. 90, 771–779 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kauer J. A., Malenka R. C., Synaptic plasticity and addiction. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 844–858 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ungless M. A., Whistler J. L., Malenka R. C., Bonci A., Single cocaine exposure in vivo induces long-term potentiation in dopamine neurons. Nature 411, 583–587 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jeevakumar V., Kroener S., Ketamine administration during the second postnatal week alters synaptic properties of fast-spiking interneurons in the medial prefrontal cortex of adult mice. Cereb. Cortex 26, 1117–1129 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harde E. et al., EphrinB2 regulates VEGFR2 during dendritogenesis and hippocampal circuitry development. eLife 8, e49819 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scipioni L., Lanzanó L., Diaspro A., Gratton E., Comprehensive correlation analysis for super-resolution dynamic fingerprinting of cellular compartments using the Zeiss Airyscan detector. Nat. Commun. 9, 5120 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malenka R. C., Nicoll R. A., Learning and memory. Never fear, LTP is hear. Nature 390, 552–553 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rao Y. et al., Repeated in vivo exposure of cocaine induces long-lasting synaptic plasticity in hypocretin/orexin-producing neurons in the lateral hypothalamus in mice. J. Physiol. 591, 1951–1966 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jaffe D., Johnston D., Induction of long-term potentiation at hippocampal mossy-fiber synapses follows a Hebbian rule. J. Neurophysiol. 64, 948–960 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klapoetke N. C. et al., Independent optical excitation of distinct neural populations. Nat. Methods 11, 338–346 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salinas-Hernández X. I. et al., Dopamine neurons drive fear extinction learning by signaling the omission of expected aversive outcomes. eLife 7, e38818 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frey S., Bergado-Rosado J., Seidenbecher T., Pape H. C., Frey J. U., Reinforcement of early long-term potentiation (early-LTP) in dentate gyrus by stimulation of the basolateral amygdala: Heterosynaptic induction mechanisms of late-LTP. J. Neurosci. 21, 3697–3703 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nabavi S. et al., Engineering a memory with LTD and LTP. Nature 511, 348–352 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Natarajan D., de Vries H., Saaltink D. J., de Boer S. F., Koolhaas J. M., Delineation of violence from functional aggression in mice: An ethological approach. Behav. Genet. 39, 73–90 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anestis S. F., Testosterone in juvenile and adolescent male chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes): Effects of dominance rank, aggression, and behavioral style. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 130, 536–545 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oyegbile T. O., Marler C. A., Winning fights elevates testosterone levels in California mice and enhances future ability to win fights. Horm. Behav. 48, 259–267 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barkley M. S., Goldman B. D., Testosterone-induced aggression in adult female mice. Horm. Behav. 9, 76–84 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barkley M. S., Goldman B. D., The effects of castration and Silastic implants of testosterone on intermale aggression in the mouse. Horm. Behav. 9, 32–48 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Archer J., Testosterone and human aggression: An evaluation of the challenge hypothesis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 30, 319–345 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eichenbaum H., Spatial learning. The LTP-memory connection. Nature 378, 131–132 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bergstrom H. C., The neurocircuitry of remote cued fear memory. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 71, 409–417 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kohl J. et al., Functional circuit architecture underlying parental behaviour. Nature 556, 326–331 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moffitt J. R. et al., Molecular, spatial, and functional single-cell profiling of the hypothalamic preoptic region. Science 362, eaau5324 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ishii K. K. et al., A labeled-line neural circuit for pheromone-mediated sexual behaviors in mice. Neuron 95, 123–137.e8 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data discussed in the paper are available in the main text and SI Appendix. We used standard MATLAB functions and publicly available software indicated in the manuscript for analysis.