Abstract

Sow fertility traits, such as litter size and the number of lifetime parities produced (reproductive longevity), are economically important. Selection for these traits is difficult because they are lowly heritable and expressed late in life. Age at puberty (AP) is an early indicator of reproductive longevity. Here, we utilized a custom Affymetrix single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) array (SowPro90) enriched with positional candidate genetic variants for AP and a haplotype-based genome-wide association study to fine map the genetic sources associated with AP and other fertility traits in research (University of Nebraska-Lincoln [UNL]) and commercial sow populations. Five major quantitative trait loci (QTL) located on four Sus scrofa chromosomes (SSC2, SSC7, SSC14, and SSC18) were discovered for AP in the UNL population. Negative correlations (r = −0.96 to −0.10; P < 0.0001) were observed at each QTL between genomic estimated breeding values for AP and reproductive longevity measured as lifetime number of parities (LTNP). Some of the SNPs discovered in the major QTL regions for AP were located in candidate genes with fertility-associated gene ontologies (e.g., P2RX3, NR2F2, OAS1, and PTPN11). These SNPs showed significant (P < 0.05) or suggestive (P < 0.15) associations with AP, reproductive longevity, and litter size traits in the UNL population and litter size traits in the commercial sows. For example, in the UNL population, when the number of favorable alleles of an SNP located in the 3′ untranslated region of PTPN11 (SSC14) increased, AP decreased (P < 0.0001), while LTNP increased (P < 0.10). Additionally, a suggestive difference in the observed NR2F2 isoforms usage was hypothesized to be the source of the QTL for puberty onset mapped on SSC7. It will be beneficial to further characterize these candidate SNPs and genes to understand their impact on protein sequence and function, gene expression, splicing process, and how these changes affect the phenotypic variation of fertility traits.

Keywords: Bayes interval mapping, custom genotyping array, gilts, puberty, reproductive longevity, SowPro90

Introduction

Improving reproductive traits (e.g., litter size and reproductive longevity) via traditional breeding and quantitative genetic approaches is challenging given these traits are lowly heritable, sex-limited, expressed late in life, and polygenic, with each gene variant having a relatively small effect. Age at puberty (AP), defined as the age at which a gilt first ovulates or expresses estrus, is an early and indirect indicator of sow fertility (Serenius and Stalder, 2006; Tart et al., 2013). Gilts that achieve puberty at an early age have a greater probability to farrow early and produce more parities over their lifetime (Tart et al., 2013). Identifying pleiotropic DNA variants that affect AP and other fertility traits, including reproductive longevity, could help to improve the accuracy of genomic prediction for sow fertility.

AP is a moderately heritable trait (mean h2 = 0.32, 16 studies reviewed by Bidanel, 2011), but traditional selection for this trait is not widely practiced in commercial settings due to extensive time and labor requirements for daily estrus detection via boar exposure. With the aim of improving the accuracy of genomic prediction for sow fertility, previously, we developed custom Affymetrix single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) arrays, SowPro90 (86,452 SNPs) and the updated version, SowPro91 (105,601 SNPs), that are enriched in novel SNPs located in major quantitative trait loci (QTL) regions for AP, other fertility- and disease-related traits, and potential loss of function SNPs (Wijesena et al., 2019). These novel genetic variants were identified using deep transcriptomic and genomic sequencing, gene network analysis, and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) carried out at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln (UNL) and US Meat Animal Research Center (USMARC), two of the largest published data sets profiling AP.

The long-term objective of this research is to improve sow fertility in commercial swine populations. The aims of this specific study were to 1) fine map pleiotropic genomic regions and genetic variants associated with AP and other fertility traits (i.e., litter size and reproductive longevity) in the UNL population using the custom SowPro90 SNP array and 2) evaluate the effects of the identified genetic variants in a commercial Landrace × Large White F1 population. To facilitate the discovery of major genetic variants associated with targeted traits, we utilized a Bayesian mixture model, called Bayes interval mapping (BayesIM, Kachman, 2015), that extends the number of SNPs from 53,529 (Illumina SNP60 Bead Array) to 86,452 (SowPro90) in a haplotype analysis and fits haplotype effects in an association analysis.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the UNL Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Project ID: 1677).

The resource populations

UNL resource population

This population was extensively genotyped and phenotyped for several fertility and growth traits to study the role of genetics and nutrition on reproductive development and longevity of sows. The females used in this study (n = 2,054 gilts) were developed in 18 batches (B). The dams of the experimental gilts were either Large White × Landrace crossbreds or Nebraska Index Line (NIL), whereas the sires were from two unrelated commercial Landrace lines. During the 104-d development period (119 to 224 d of age) before breeding, gilts were subjected to four main experimental diets (with or without phase feeding). The diets included, 1) ad libitum standard corn–soybean-based diet, 2) energy-restricted diet with approximately 20% less metabolizable energy (ME), 3) energy- and lysine-restricted diet, and 4) a diet containing high protein and lysine with the same ME as in the standard diet and lysine:ME ratio as in the restricted diet. A detailed description of the resource population and dietary treatments can be found in Miller et al. (2011) and Trenhaile (2015).

Commercial populations

The research also involved 2,309 pigs from two separate industry sources, including 1) the parental genetic pure lines of the UNL resource population (Landrace and Yorkshire, n = 337 boars and sows) and 2) one of the most prevalent Landrace × Large White F1 crossbreds (n = 1,972 sows; Wijesena et al., 2019). These genetic sources were produced using standard commercial breeding practices.

Phenotypes

UNL resource population

Estrous detection in the UNL population began at approximately 130 d of age. The age at which gilts expressed first standing estrus was defined as the AP. Estrus detection was carried out daily by exposing the gilts to a mature intact boar for 15 min in an adjacent pen until all the gilts expressed estrus twice within a development pen or until they reached 224 d of age. The females were maintained and reproductive data collected up to four parities unless they died or were culled for reproductive, health, or structural failure.

Commercial population

The commercial Landrace × Large White F1 crossbred females entered five different farms as gilts during 2013. Reproductive data were available from up to eight parities unless the females were culled due to reproductive issues, age, or other structural and health reasons. It should also be noted that AP data were not available for commercial females.

The reproductive data available in UNL (n = 2,054) and commercial Landrace × Large White F1 (n = 1,972) data sets included litter size traits, such as total number of piglets born (TNB-P1 and TNB-P2) and number born alive (NBA-P1 and NBA-P2) in the first two parities, and reproductive longevity defined as lifetime number of parities (LTNP) produced up to four (0 to 4) parities in UNL and up to eight (0 to 3, >3) parities in commercial sows. For LTNP, the number of parities produced was recorded until reproductive failure and females that were culled due to nonreproductive reasons were removed from further analysis.

Genotyping

Tail snips or ear notches were collected from UNL gilts and commercial pigs shortly after birth. DNA was isolated from these tissues using the DNeasy or Puregene tissue kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The DNA quantity and purity were assessed using a NanoDrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA), Epoch (BioTek Inc., Winooski, VT) spectrophotometers or Qubit fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA).

The majority of the gilts from UNL (B1 to B14, n = 1,556) were previously genotyped with the commercial Porcine SNP60 BeadArray (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA; Tart et al., 2013; Wijesena et al., 2017). Gilts from UNL B15 to B17 (n = 375), commercial Landrace × Large White F1 females (n = 1,972), and commercial maternal parental lines (n = 314) were genotyped with SowPro90 custom SNP array (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA) (Wijesena et al., 2019). A subset of UNL gilts from B1 to B14 (UNL extreme gilts [UNLe]; n = 270) representing the tails of the distribution for Porcine SNP60 BeadArray (53,529 SNPs)-derived genomic estimated breeding values (GEBV) for AP (early, n = 147; late, n = 123) was also genotyped with SowPro90. After the initial quality evaluation of SowPro90, the array content was updated (SowPro91), excluding monomorphic and non-recommended SNPs (Wijesena et al., 2019) and including novel SNPs located in genes across the genome. Batch 18 (n = 123) was genotyped with SowPro91. Porcine SNP60 BeadArray genotypes were filtered at Illumina quality score ≥ 0.4 and sample and SNP call rate ≥ 80% leaving 53,529 SNPs for further analysis. The SowPro90 and SowPro91 genotype data were filtered at ≥93% sample and ≥97% SNP call rates. There were 86,452 SNPs from SowPro90 available for downstream analysis. Since only one UNL batch (B18) was genotyped with SowPro91, only the recommended SNPs that were common between SowPro90 and SowPro91 (77,695 SNPs) were used for downstream analysis of this batch.

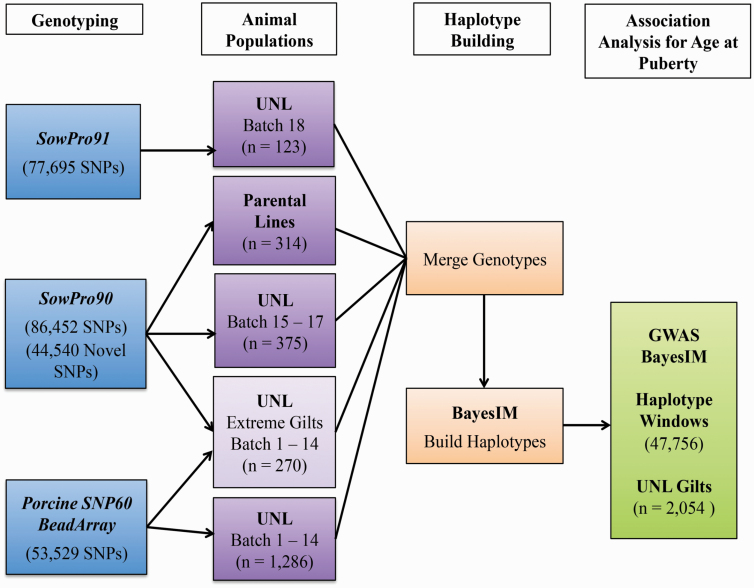

Infer SowPro90 haplotypes and genome-wide association analyses in the UNL population using BayesIM

Since the majority of the UNL population (~80%) was genotyped with the more limited Porcine SNP60 BeadArray, a Bayesian method (BayesIM) that utilizes haplotypes instead of individual SNPs in association analysis was implemented to infer SowPro90 haplotypes to the entire UNL population (Kachman, 2015). This approach, which is an alternative to imputation, extended the number of SNPs from 53,529 (Illumina SNP60 Bead Array) to 86,452 SNPs (SowPro90). To infer haplotypes, BayesIM used a reference data set that consisted of a subset of UNL gilts genotyped with SowPro90 and SowPro91 and sows and boars from commercial Landrace and Yorkshire lines genotyped with SowPro90. The sires of the UNL resource population originated from these two commercial lines (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the approach used for haplotype-based association analysis using BayesIM. Experimental UNL gilts and commercial parental lines of both sexes were genotyped with either Porcine SNP60 BeadArray, SowPro90, or SowPro91. Genotype information obtained from SowPro90 was used as a reference data set to infer SowPro90 haplotypes to the entire UNL population, previously genotyped with Porcine SNP60 BeadArray. The haplotypes assigned by BayesIM were used in a haplotype-based GWAS for AP.

Given QTL are unlikely to exist at the genotyped SNP location, and in order to take advantage of information from neighboring SNPs, a haplotype-based GWAS using BayesIM (Kachman, 2015; Wilson-Wells and Kachman, 2016; Schweer et al., 2018) was performed to estimate the proportion of genetic variance for AP (B1 to B18, n = 2,054) and LTNP (B1 to B17, n = 1,853) in the entire UNL population explained by SowPro90 SNP genotypes. The SNPs were mapped to the Sscrofa11.1 reference genome assembly (http://igenomes.illumina.com.s3-website-us-east-1.amazonaws.com/Sus_scrofa/Ensembl/Sscrofa11.1/Sus_scrofa_Ensembl_Sscrofa11.1.tar.gz – [accessed November 7, 2016]). BayesIM first builds a haplotype model where the genome is partitioned into variable length segments, and each segment is assigned to a haplotype state also called haplotype cluster. Haplotypes were assigned to individuals based on similarity using a hidden Markov model. In the haplotype model, the emission probability for a haplotype state at an SNP locus is the frequency of the A allele, and the transition probabilities between two loci were based on the distance between the loci. Given the haplotype model, BayesIM haplotype states at equally spaced haplotype, loci are sampled using a Metropolis–Hastings algorithm. The haplotype states, instead of SNP genotype, are used as covariates in the model. Similar to BayesC (Habier et al., 2011), the probability of a nonzero haplotype effect at a given locus is given by 1 − π, where π is the probability that a haplotype does not have an effect. The value of π was assumed to be 0.99; the number of haplotype states at each location was assumed to be eight; QTL frequency was 50 Kb (n = 47,756 haplotype windows); average haplotype length was 250 Kb; and the number of iterations to assign haplotypes was 25. The Markov chain Monte Carlo chain included 82,000 samples with the first 1,000 being discarded as burn in. The fixed effects included contemporary group (concatenation of batch and diet) and genetic line. Random effects included litter and developmental pen. Genetic variance and haplotype effects were estimated for each 50-Kb QTL region.

Correlation between GEBV for AP and LTNP in the UNL population

The haplotype windows (50 Kb) were ranked based on the genetic variance explained for AP and the top five distinct QTL regions located on four chromosomes were identified in the UNL population. These regions were extended in both directions to a 1-Mb QTL interval. GEBV for AP were calculated for all the UNL gilts for the five major 1-Mb windows by summing the product of posterior mean marker effects by marker genotypes across all SNP in the QTL region. Similarly, GEBV for LTNP were calculated for the five major AP QTL windows and for adjacent 1-Mb sliding windows that originated from the top AP window location and extended in both directions, each moving 250 Kb from the previous window. There were eight sliding windows on each side of the top window location, and the distance between the center of the top AP QTL and the last sliding window was 2.5 Mb. The pairwise correlation between GEBV for AP and LTNP for major QTL regions and adjacent sliding windows was calculated using JMP (version Pro 14.1.0, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Haplotype effects were calculated for AP and LTNP for the 5-Mb region (region between the 16 sliding 1-Mb windows) flanking the top QTL regions for AP.

Single-marker association and linkage disequilibrium analyses

UNL resource population

A general linear mixed model was used to test the additive effects of SNP located in the major 1-Mb windows (± 0.2 Mb flanking region) on AP in the UNLe subset of gilts (B1 to B14, n = 270). Association of these SNPs with other targeted fertility traits (e.g., LTNP, TNB-P1, TNB-P2, and NBA-P1, NBA-P2) was also tested in the same UNLe subset. The SNP effects were also tested separately in the subsequent batches of UNL sows (B15 to B17, n = 375) for AP, LTNP, and litter size traits. In both UNL subsets, the model included the fixed effects of SNP genotype and contemporary group (concatenation of batch and diet) and sire, litter, and development pen as random effects.

Commercial population

Significant SNPs identified in the UNL population were tested separately in the commercial Landrace × Large White F1 (n = 1,972) for LTNP and litter size traits. In this population, the model included SNP genotype, contemporary group (concatenation of farm and entry month), birth farm, and farm entry age as fixed effects and sire and litter as random effects.

For SNPs with significant F tests, a pairwise comparison of least squares means for each genotype was performed using the Tukey test. A significant association between an SNP and a trait was considered at P < 0.05 and suggestive at P < 0.15. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) was assessed in the top QTL regions (e.g., SSC7 and SSC14) using SowPro90 genotypes and HAPLOVIEW (Barrett et al., 2005).

Gene ontology and variant effect predictor analyses

The top QTL regions (± 0.2 Mb flanking region) were characterized for positional candidate genes using the Sscrofa build 11.1. The candidate genes and their gene ontology terms were obtained using the BIOMART tool in the Ensembl database (version 99; http://uswest.ensembl.org/biomart/martview/e0267c5280d49b8815f710187ba39839 [accessed February 10, 2020]). The SIFT scores and consequences of potential functional SNPs were obtained using Variant Effect Predictor in the Ensembl database (https://uswest.ensembl.org/Tools/VEP [accessed March 4, 2020]).

Results and Discussion

The aim of this study was to fine map and identify major genetic variants associated with phenotypic variation of AP in the UNL population using SowPro90. Knowing the role of AP as an indicator of sow fertility, potential major variants identified in the UNL discovery population were evaluated for their effect on other fertility traits (i.e., litter size and reproductive longevity) in the UNL and commercial maternal crossbreds.

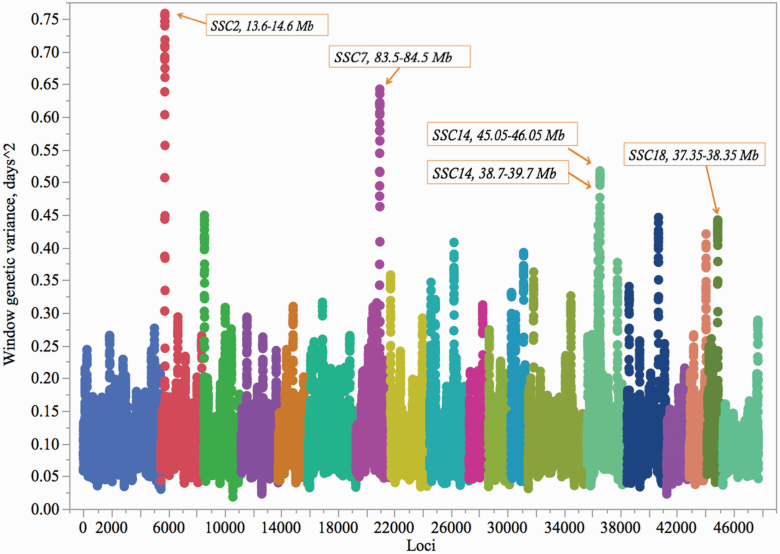

Genomic regions associated with AP were identified in the UNL population using QTL-enriched SowPro90 genotyping array

The haplotype-based BayesIM mixture model assigned haplotypes to the entire UNL population and utilized them in a haplotype-based association analysis (n = 47,756 haplotype windows) for AP and LTNP. This approach extended the genotype data from 53,529 (Illumina SNP60 Bead Array) to 86,452 SNPs (SowPro90) in the entire UNL data set. The combined haplotype effects explained 64% of phenotypic variation for AP (genomic h2). Five major 1-Mb QTL regions were identified for AP on SSC2 (13.6 to 14.6 Mb), SSC7 (83.5 to 84.5 Mb), SSC14 (38.7 to 39.7 and 45.05 to 46.05 Mb), and SSC18 (37.35 to 38.35 Mb; Figure 2). The proportion of phenotypic variation explained by these QTL was limited ranging from 0.12% to 0.20%. The QTL on SSC2, SSC7, and SSC14 also overlapped the top 1% major 1-Mb windows for AP identified in the previous GWAS in the UNL population using Porcine SNP60 BeadArray (Wijesena et al., 2017). Four of these top QTL regions were enriched with SNPs in SowPro90 and SowPro91 (Wijesena et al., 2019).

Figure 2.

Genome-wide association analysis for AP using SowPro90. The autosomes, from SSC1 to SSC18, followed by chromosome X are represented by different colors. Each dot represents a 50-Kb haplotype window. The boxed labels indicate the top five QTL regions for AP.

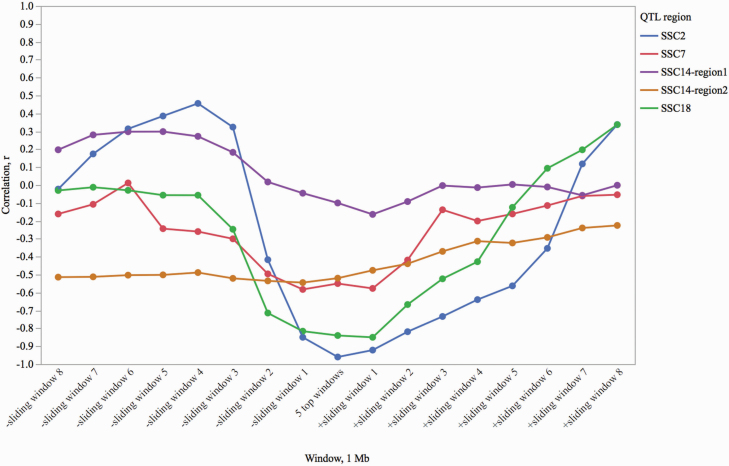

Negative correlations were detected between QTL-based GEBV for AP and LTNP in the UNL population

Previously, using Porcine SNP60 BeadArray, we reported negative low-to-moderate genomic relationships between AP and measures of lifetime productivity, such as number of parities produced by a sow during lifetime (r = −0.45), lifetime TNB (r = −0.25), and NBA (r = −0.28; P < 0.0001; Tart et al., 2013). We expected that some of the major QTL identified for AP would have an effect on other fertility phenotypes including reproductive longevity. Due to the nature of the phenotype and well-defined phenotyping procedure, the position of QTL for AP were distinct compared with the QTL for LTNP, which were less defined. To evaluate the effect of these major AP QTL on reproductive longevity, the correlation between GEBV for AP and LTNP was calculated for the top five regions. Additionally, the GEBV were calculated for LTNP in eight 1-Mb sliding windows by 250 Kb from the top windows detected for AP in each direction. This approach was used to observe the extent and the decay of the correlation between AP and reproductive longevity (Figure 3). As expected, negative correlations between AP and LTNP were observed across top AP QTL regions (r = −0.96 to −0.10; P < 0.0001). As the sliding windows for LTNP shifted away from the major QTL locations for AP, the correlation diminished reaching zero (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Correlation of GEBV for AP (top windows) and LTNP (top windows for AP and adjacent sliding windows). Adjacent windows for LTNP are sliding by 250 Kb. The distance between the center of the top QTL and the last sliding window is 2.5 Mb. SSC14-region1 represents 38.7 to 39.7 Mb QTL region, and SSC14-region2 represents 45.05 to 46.05 Mb QTL region. All the regions show negative correlations at the top QTL window, and the correlation reaches zero as moving away from the major QTL regions.

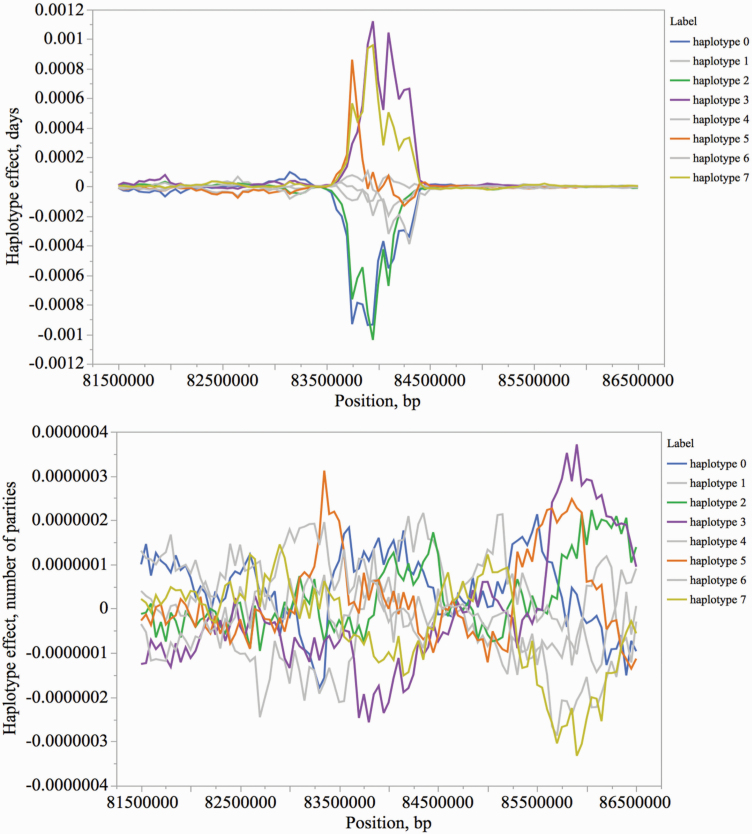

To further investigate the effect of these QTL regions on both traits, the haplotype effects (n = 8 haplotypes) were obtained for each region for AP and LTNP. For all QTL regions, the haplotypes with the largest effects on AP had an opposite effect on LTNP (Figure 4). As expected, the effects for LTNP were not as prominent as in AP. None of these top QTL regions associated with AP were among the top QTL identified for LTNP. This trait is complex, composite, and largely affected by the environment, making it difficult to fine map the underlying genetic sources driving the phenotypic variation.

Figure 4.

Haplotype effects for SSC7 QTL (5-Mb region including the sliding windows) for AP (top) and LTNP (bottom). Haplotypes with the largest effects on AP are shown in different colors, while the haplotypes with smaller effects are shown in gray for both traits. An opposite direction of the haplotype effects was observed between AP and LTNP. For example, haplotype 3 (purple) was associated with increasing AP and decreasing LTNP. Haplotype effects (d for AP and number of parities for LTNP) were presented as deviation from the mean of each QTL, which was set to zero.

SNPs located in major QTL explained some of the variation in AP and other fertility traits in the UNL and Commercial Landrace × Large White F1 populations

In order to identify major SNPs associated with fertility traits in UNL and commercial populations, all SNPs (n = 510 SNPs) representing the five major QTL regions for AP were used in a single-marker association analysis. Initially, the SNP effects on AP were estimated in a subset of UNL gilts representing the tails of the distribution for Porcine SNP60 BeadArray-derived GEBV for AP (UNLe, B1 to B14) using SowPro90 genotypes. Of all the SNPs tested, 35.5% had significant additive effects for AP (P < 0.05). Of these significant SNPs, 71.3% were located in 29 genes. All the SNPs (n = 510 SNPs) were also evaluated in a data set consisting of gilts from subsequent UNL batches (B15 to B17). Nineteen percent of the SNPs showed significant additive effects on AP, while 6.5% of the SNPs were significant in both UNL data sets. AP was not available in the commercial data set. Therefore, we were unable to validate these SNPs for AP across populations.

Ten SNPs with the largest additive effects (P < 0.05) on AP (in the UNLe) were selected for each QTL region (n = 50 SNPs) to evaluate their impact on other fertility traits (LTNP, TNB, and NBA). In the UNLe data set, a subset of SNPs also had significant effects on LTNP (16%) and TNB-P1 (18%). In the commercial data set, 2% of the SNPs had a suggestive effect (P < 0.15) on LTNP; however, the direction of the effect was opposite compared to the UNLe dataset. In the same commercial data set, a subset of SNPs was identified with significant or suggestive effects for TNB-P1 (14%), TNB-P2 (2%), NBA-P1 (26%), and NBA-P2 (6%).

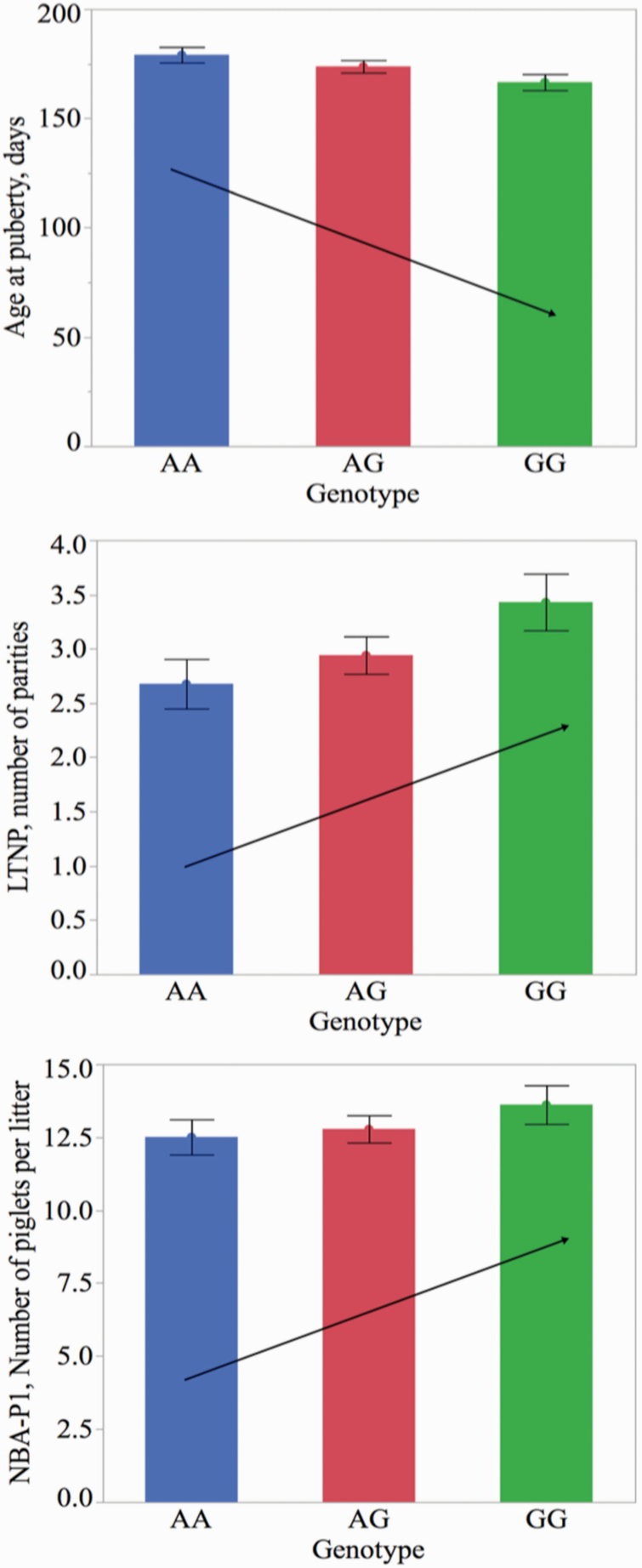

Specifically, the QTL located on SSC7 (83.3 to 84.7 Mb) showed evidence of pleiotropy influencing AP, LTNP, and litter size traits in the UNL population. The SNP associated with the largest effect on AP (AX-116689678, SSC7, 83.3 Mb, P = 0.01) also explained some of the phenotypic variations in LTNP and NBA-P1. As the number of favorable alleles increased, AP decreased by 6 d in UNLe gilts (P = 0.01) and by 4.1 d in subsequent UNL batches (P = 0.02). Lifetime number of parities and NBA-P1 increased by 0.37 litters (P = 0.03) and 0.53 piglets per litter (P = 0.24), respectively, in the UNLe sows (Table 1; Figure 5).

Table 1.

Single-marker association results of the SNPs that represent top QTL regions for AP on other fertility traits

| Least square means ± standard error4 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | Chr | Position, bp | Alleles | Trait1 | Data set2 | n | P-value3 | 11 | 12 | 22 |

| AX-116162218 | 2 | 14770110 | C/T | AP | UNL-Ex | 270 | 0.0001*** | 155.69a ± 13.50 | 168.19b ± 2.56 | 179.70 ± 2.82 |

| UNL B15-17 | 375 | 0.7913 | 167.65 ± 4.79 | 162.54 ± 1.95 | 163.37 ± 2.20 | |||||

| LTNP | UNL-Ex | 259 | 0.6206 | 2.69 ± 0.98 | 2.94 ± 0.17 | 3.04 ± 0.19 | ||||

| Commercial | 904 | 0.6493 | 2.70 ± 0.15 | 2.95 ± 0.07 | 2.90 ± 0.06 | |||||

| TNB-P1 | UNL-Ex | 189 | 0.2139 | 15.56 ± 2.02 | 14.64 ± 0.37 | 14.12 ± 0.42 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,675 | 0.0872* | 12.73 ± 0.28 | 12.94 ± 0.13 | 12.87 ± 0.12 | |||||

| TNB-P2 | UNL-Ex | 119 | 0.1224* | 15.58 ± 4.30 | 13.80 ± 0.50 | 12.68 ± 0.59 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,359 | 0.9746 | 13.96 0.36 | 13.39 0.17 | 13.61 0.15 | |||||

| NBA-P1 | UNL-Ex | 189 | 0.0843* | 14.85 ± 2.43 | 13.48 ± 0.41 | 12.63 ± 0.46 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,675 | 0.4527 | 12.15 ± 0.28 | 12.25 ± 0.13 | 12.08 ± 0.12 | |||||

| NBA-P2 | UNL-Ex | 119 | 0.1255* | 12.54 ± 4.65 | 12.54 ± 0.51 | 11.28 ± 0.61 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,359 | 0.9798 | 13.39 ± 0.35 | 12.79 ± 0.17 | 13.01 ± 0.16 | |||||

| AX-116689678 | 7 | 83373091 | A/G | AP | UNL-Ex | 270 | 0.0105** | 179.06a ± 3.56 | 173.75 ± 2.87 | 166.52b ± 3.71 |

| UNL B15-17 | 375 | 0.0166** | 167.83a ± 2.42 | 161.59 ± 1.94 | 160.18b ± 2.74 | |||||

| LTNP | UNL-Ex | 259 | 0.0278** | 2.68 ± 0.23 | 2.94 ± 0.17 | 3.43 ± 0.26 | ||||

| Commercial | 904 | 0.7173 | 2.90 ± 0.06 | 2.90 ± 0.08 | 3.05 ± 0.23 | |||||

| TNB-P1 | UNL-Ex | 189 | 0.8738 | 14.46 ± 0.51 | 14.45 ± 0.42 | 14.33 ± 0.51 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,675 | 0.1455* | 12.96 ± 0.11 | 12.73 ± 0.14 | 12.67 ± 0.38 | |||||

| TNB-P2 | UNL-Ex | 119 | NA | 13.73 ± 0.72 | 13.35 ± 0.52 | 12.90 ± 0.70 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,359 | 0.8540 | 13.50 ± 0.14 | 13.68 ± 0.19 | 13.14 ± 0.48 | |||||

| NBA-P1 | UNL-Ex | 189 | 0.2377 | 12.51 ± 0.60 | 12.78 ± 0.47 | 13.62 ± 0.66 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,675 | 0.8869 | 12.16 ± 0.11 | 12.13 ± 0.14 | 12.16 ± 0.39 | |||||

| NBA-P2 | UNL-Ex | 119 | 0.8244 | 11.81 ± 0.84 | 12.28 ± 0.62 | 11.63 ± 0.80 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,359 | 0.4233 | 12.86 ± 0.15 | 13.11 ± 0.19 | 12.83 ± 0.47 | |||||

| AX-134892687 (NR2F2) Promoter | 7 | 83091580 | C/T | AP | UNL-Ex | 270 | 0.1305* | 170.23 ± 2.90 | 175.50 ± 2.95 | 177.01 ± 5.00 |

| UNL B15-17 | 375 | 0.0065*** | 155.98a ± 3.52 | 163.12 ± 1.90 | 167.53b ± 2.41 | |||||

| LTNP | UNL-Ex | 259 | 0.0594* | 3.26 ± 0.19 | 2.79 ± 0.18 | 2.69 ± 0.34 | ||||

| Commercial | 904 | 0.4942 | 1.17 ± 0.84 | 2.98 ± 0.09 | 2.88 ± 0.06 | |||||

| TNB-P1 | UNL-Ex | 189 | 0.7901 | 14.39 ± 0.43 | 14.39 ± 0.42 | 14.68 ± 0.76 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,675 | 0.6246 | 11.41 ± 2.09 | 12.96 ± 0.16 | 12.85 ± 0.10 | |||||

| TNB-P2 | UNL-Ex | 119 | NA | 12.51 ± 0.51 | 13.82 ± 0.50 | 15.58 ± 1.10 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,359 | 0.1628 | 12.87 ± 3.39 | 13.78 ± 0.21 | 13.46 ± 0.14 | |||||

| NBA-P1 | UNL-Ex | 189 | 0.7719 | 12.81 ± 0.48 | 12.95 ± 0.48 | 13.06 ± 0.91 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,675 | 0.2338 | 10.06 ± 2.10 | 12.33 ± 0.16 | 12.09 ± 0.11 | |||||

| NBA-P2 | UNL-Ex | 119 | 0.1762 | 11.37 ± 0.57 | 12.20 ± 0.6 | 13.84 ± 1.23 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,359 | 0.1762 | 11.61 ± 3.37 | 13.18 ± 0.21 | 12.86 ± 0.14 | |||||

| AX-135052973 (NR2F2) 5′ UTR | 7 | 83090047 | C/T | AP | UNL-Ex | 270 | 0.2192 | 171.32 ± 2.86 | 174.51 ± 2.98 | 177.69 ± 5.26 |

| UNL B15-17 | 375 | 0.0042*** | 160.46a ± 2.12 | 163.22b ± 1.98 | 170.10b ± 2.83 | |||||

| LTNP | UNL-Ex | 259 | 0.1729 | 3.19 ± 0.19 | 2.81 ± 0.18 | 2.85 ± 0.36 | ||||

| Commercial | 904 | 0.3378 | 2.95 ± 0.14 | 2.94 ± 0.07 | 2.86 ± 0.07 | |||||

| TNB-P1 | UNL-Ex | 189 | 0.8959 | 14.50 ± 0.42 | 14.25 ± 0.43 | 14.97 ± 0.82 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,675 | 0.4241 | 12.83 ± 0.24 | 12.81 ± 0.12 | 12.96 ± 0.12 | |||||

| TNB-P2 | UNL-Ex | 119 | NA | 12.39 ± 0.50 | 14.02 ± 0.51 | 15.07 ± 1.14 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,359 | 0.5872 | 13.58 ± 0.32 | 13.60 ± 0.16 | 13.47 ± 0.16 | |||||

| NBA-P1 | UNL-Ex | 189 | 0.6371 | 12.80 ± 0.47 | 12.94 ± 0.49 | 13.32 ± 0.97 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,675 | 0.6064 | 12.21 ± 0.25 | 12.18 ± 0.12 | 12.11 ± 0.13 | |||||

| NBA-P2 | UNL-Ex | 119 | 0.0765* | 11.24 ± 0.56 | 12.49 ± 0.59 | 13.13 ± 1.28 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,359 | 0.5150 | 12.95 ± 0.32 | 13.03 ± 0.16 | 12.85 ± 0.17 | |||||

| AX-179489698 (NR2F2) Intron 1 | 7 | 83084320 | C/T | AP | UNL-Ex | 270 | 0.3096 | 171.47 ± 2.89 | 174.00 ± 2.96 | 177.07 ± 5.51 |

| UNL B15-17 | 375 | 0.0289** | 161.83a ± 2.11 | 162.04b ± 1.99 | 171.00b ± 3.09 | |||||

| LTNP | UNL-Ex | 259 | 0.1158* | 3.21 ± 0.19 | 2.80 ± 0.18 | 2.78 ± 0.38 | ||||

| Commercial | 904 | 0.4730 | 2.98 ± 0.17 | 2.92 ± 0.07 | 2.88 ± 0.07 | |||||

| TNB-P1 | UNL-Ex | 189 | 0.6476 | 14.37 ± 0.44 | 14.32 ± 0.43 | 15.05 ± 0.87 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,675 | 0.3970 | 12.63 ± 0.29 | 12.86 ± 0.12 | 12.92 ± 0.12 | |||||

| TNB-P2 | UNL-Ex | 119 | 0.0377** | 12.47 ± 0.56 | 14.04 ± 0.58 | 14.98 ± 1.35 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,359 | 0.3050 | 13.78 ± 0.37 | 13.61 ± 0.16 | 13.45 ± 0.16 | |||||

| NBA-P1 | UNL-Ex | 189 | 0.9842 | 13.01 ± 0.47 | 12.85 ± 0.47 | 13.17 ± 1.00 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,675 | 0.5568 | 12.10 ± 0.29 | 12.22 ± 0.13 | 12.08 ± 0.12 | |||||

| NBA-P2 | UNL-Ex | 119 | 0.1358* | 11.36 ± 0.58 | 12.48 ± 0.59 | 13.03 ± 1.37 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,359 | 0.2122 | 13.16 ± 0.37 | 13.04 ± 0.17 | 12.82 ± 0.16 | |||||

| AX-123958897 (NR2F2) Intron 1 | 7 | 83088085 | A/G | AP | UNL-Ex | 270 | 0.0885* | 175.47 ± 3.71 | 175.91 ± 2.82 | 166.89 ± 3.59 |

| UNL B15-17 | 375 | 0.0038*** | 167.76a ± 2.38 | 162.17b ± 2.02 | 156.40b ± 3.71 | |||||

| LTNP | UNL-Ex | 259 | 0.0146** | 2.57a ± 0.24 | 2.96 ± 0.17 | 3.40b ± 0.25 | ||||

| Commercial | 904 | 0.5561 | 2.90 ± 0.05 | 2.97 ± 0.12 | NA | |||||

| TNB-P1 | UNL-Ex | 189 | 0.1907 | 14.87 ± 0.53 | 14.51 ± 0.40 | 13.89 ± 0.55 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,675 | 0.9868 | 12.89 ± 0.09 | 12.91 ± 0.22 | 10.01 ± 2.97 | |||||

| TNB-P2 | UNL-Ex | 119 | NA | 14.67 ± 0.96 | 12.97 ± 0.50 | 13.00 ± 0.81 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,359 | 0.2663 | 13.49 ± 0.13 | 13.83 ± 0.29 | 12.93 ± 3.39 | |||||

| NBA-P1 | UNL-Ex | 189 | 0.7808 | 13.16 ± 0.64 | 12.79 ± 0.46 | 12.95 ± 0.63 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,675 | 0.6732 | 12.14 ± 0.10 | 12.27 ± 0.22 | 8.99 ± 2.97 | |||||

| NBA-P2 | UNL-Ex | 119 | NA | 13.24 ± 0.83 | 11.54 ± 0.49 | 11.80 ± 0.71 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,359 | 0.0987* | 12.87 ± 0.13 | 13.38 ± 0.29 | 11.68 ± 3.36 | |||||

| AX-141921242 | 14 | 39203611 | A/C | AP | UNL-Ex | 270 | <0.0001*** | 181.24a ± 2.74 | 164.62b ± 3.02 | 159.83b ± 5.57 |

| UNL B15-17 | 375 | 0.0577* | 164.46 ± 1.77 | 160.10 ± 2.12 | 165.29 ± 10.68 | |||||

| LTNP | UNL-Ex | 259 | 0.1046* | 2.83 ± 0.17 | 3.09 ± 0.20 | 3.46 ± 0.40 | ||||

| Commercial | 904 | 0.4854 | 2.92 ± 0.11 | 2.93 ± 0.06 | 2.85 ± 0.08 | |||||

| TNB-P1 | UNL-Ex | 189 | 0.4084 | 14.18 ± 0.4 | 15.02 ± 0.44 | 14.20 ± 0.79 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,675 | 0.1888 | 12.71 ± 0.19 | 12.87 ± 0.11 | 13.02 ± 0.15 | |||||

| TNB-P2 | UNL-Ex | 119 | NA | 12.83 ± 0.60 | 13.76 ± 0.64 | 13.50 ± 1.22 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,359 | 0.7512 | 13.56 ± 0.25 | 13.50 ± 0.15 | 13.63 ± 0.20 | |||||

| NBA-P1 | UNL-Ex | 189 | 0.6806 | 12.80 ± 0.46 | 13.69 ± 0.50 | 12.28 ± 0.94 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,675 | 0.0630* | 11.86 ± 0.19 | 12.15 ± 0.11 | 12.32 ± 0.16 | |||||

| NBA-P2 | UNL-Ex | 119 | NA | 11.94 ± 0.61 | 11.91 ± 0.68 | 12.62 ± 1.19 | ||||

| Commercial | 1,359 | 0.2988 | 12.84 ± 0.25 | 12.89 ± 0.15 | 13.12 ± 0.20 | |||||

1AP (d); LTNP (litters); TNB (piglets per litter); NBA (piglets per litter).

2UNLe, UNL extreme gilts (Batch 1 to 14). UNL B15-17, UNL gilts (Batch 15 to 17). Commercial: Large White × Landrace maternal crossbreds.

3P-value for the overall test of the effect of genotypes. ***P < 0.01, **P < 0.05, *P < 0.15.

4The alleles (1 and 2) are designated based on the alphabetical order of SNP variants (A, C, G, and T).

a,bLeast-square means differ at P ≤ 0.05.

Figure 5.

Least square means and standard errors for AP (P = 0.01), LTNP (P = 0.03), and NBA-P1 (P = 0.24) for AX-116689678 SNP genotypes in the UNLe data set. AX-116689678 had the largest effect on AP in the SSC7 QTL region. As the number of G alleles increased, AP decreased while LTNP and NBA-P1 increased

Similarly, the SSC2 QTL (13.4 to 14.8 Mb) showed pleiotropic effects for AP and litter size traits in the UNL population. The major SNP in this region (AX-116162218, SSC2, 14.7 Mb, P = 0.0001) explained 24-d difference in AP between homozygote genotypes (P = 0.04, UNLe gilts). As the number of favorable alleles increased, AP decreased by 11.6 d (P = 0.0001), and both TNB-P1 and NBA-P1 increased by 0.54 (P = 0.21) and 0.88 (P = 0.08) piglets per litter, respectively. For TNB, a numerical increase continued in P2 with a suggestive additive effect of 1.2 piglets per litter (P = 0.12; Table 1).

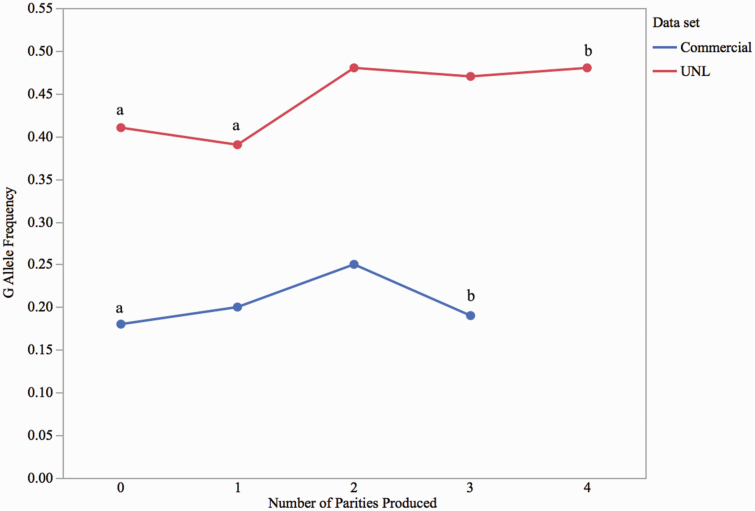

Changes in allelic frequency of major SNPs associated with AP and LTNP were observed across parities

Since SNP such as AX-116689678 (SSC7, 83.3 Mb) was associated with both AP (P = 0.01) and LTNP (P = 0.03), a change in allele frequency across parities was expected, as sows with poor fertility were culled during the experiment. This analysis included only females culled due to reproductive reasons. The frequency of the favorable allele increased from 0.41, in UNL sows unable to generate a parity, to 0.48, in sows that produced four parities (P < 0.05; Figure 6). Similarly, in the commercial data set, the frequency of the same allele slightly increased from 0.18 in sows unable to generate a parity to 0.19 in sows that produced three or more parities (Figure 6), even though the effect was not significant (P = 0.72).

Figure 6.

The frequency of favorable (G) AX-116689678 allele across parities in the UNL and commercial populations. The allele frequency increased from 0.41 in sows that were unable to generate a parity to 0.48 in sows that produced four parities in the UNL population (n = 645). Similarly, an increase in the allele frequency was observed from 0.18 in sows unable to generate a parity to 0.19 in sows that produced three or more parities in the commercial population (n = 904). a,bSuperscripts represent allele frequency changes that differ at P < 0.05.

Some of the SNPs associated with the largest effects are intergenic and in long-range LD with candidate genes

Surprisingly, some of the major SNPs identified for AP (e.g., AX-116162218 [SSC2] and AX-116689678 [SSC7]) have an intergenic location despite our effort to enrich SowPro90 with genic SNPs located in the QTL regions. One of the reasons could include limited annotation of the swine genome, especially the regulatory motifs that work in cis and influence gene expression and ultimately phenotypic variation.

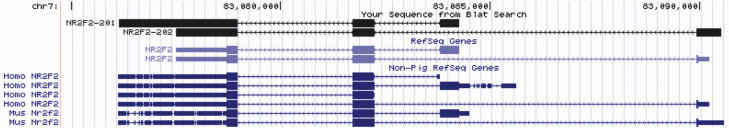

Specifically, in the current reference genome, there were no annotated genes identified in the SSC7 QTL region (83.3 to 84.7 Mb). Therefore, this region was extended by 0.5 Mb in both directions. Long-range LD (r2: 0.32 to 0.68) was detected between AX-116689678 (SSC7, 83.3 Mb) and four SNPs in nuclear receptor subfamily 2 group f member 2 (NR2F2; 83.07 Mb), a transcription factor located ~280 Kb upstream. The SNPs were in the proximal promoter (AX-134892687), 5′ untranslated region (UTR; AX-135052973), and intronic (AX-123958897 and AX-179489698) regions. Even though the gene is located quite distant from the QTL, the moderate-to-high LD between the QTL and NR2F2 SNPs suggests that this could be a potential candidate gene for AP. When the effects of NR2F2 SNPs were evaluated in a subsequent analysis (Table 1), significant additive effects for AP were detected in the UNL B15 to B17 (P < 0.05) gilts and suggestive effects in the UNLe gilts (P < 0.15; Table 1). Three of the NR2F2 SNPs (AX-135052973, AX-123958897, and AX-179489698) showed expected (opposite) direction of the association for AP (P < 0.05; UNL B15 to B17) and LTNP in the commercial data set (although the effects were not significant, P = 0.34 to 0.56; Table 1).

The closest gene to AX-116162218 (SSC2, 14.7 Mb), the major SNP on SSC2 QTL (13.4 to 14.8 Mb), is a small nuclear RNA (U6) located ~8 Kb downstream. Seven other top SNPs with the largest effects on AP in the region were located in genes (P2RX3, SSRP1, and PTPRJ). Three synonymous SNPs associated with AP (P < 0.05) were located in P2RX3, a gene involved in implantation and pregnancy (Slater et al., 2000). This QTL region was previously identified as a major QTL and a potential selection sweep for litter size traits in the UNL resource population (Trenhaile et al., 2016). P2X purinoceptor 3 gene was monomorphic in NIL, a line extensively selected for litter size traits for over 29 generations, while polymorphic in lines not subjected to selection for fertility traits (Trenhaile et al., 2016). The UNL experimental gilts were originated from NIL dams and that could explain the observed effect of this region on litter size traits in our population.

In the SSC14 QTL region (38.7 to 39.7 Mb), the 10 SNPs with the largest effects on AP were noncoding and located in seven genes (OAS1, OAS2, RPH3A, PTPN11, HECTD4, TRAFD1, and NAA25). This QTL was characterized by high LD in both UNL and commercial populations. The SNP associated with the largest effect on AP (AX-141921242, 39.2 Mb, P < 0.0001) was in high LD (r2 > 0.95) with next nine ranked SNPs associated with AP. In UNLe gilts, as the number of favorable alleles for these 10 SNPs increased, AP significantly decreased (11.9 to 13.1 d; P < 0.0001), while there was a numerical increase in LTNP (0.24 to 0.29 litters; P = 0.10 to 0.16; Table 1). The expected effect of these SNPs on AP was not observed in the subsequent UNL batches (B15 to B17) as the frequency of favorable homozygous genotype was very low (0.53%). Eight SNPs including the top SNP showed suggestive additive effects (P < 0.15) for NBA-P1 ranging from 0.16 to 0.23 piglets per litter in the commercial data set (Table 1).

Variation in NR2F2 isoform usage and AP onset

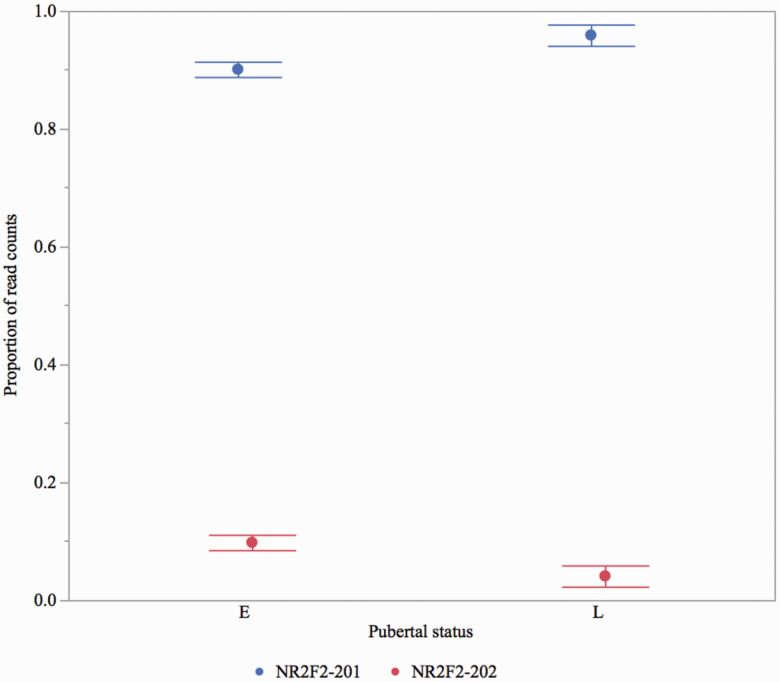

The NR2F2, the candidate gene located upstream (~280 Kb) of the AX-116689678 (SSC7), is a ligand-activated transcription factor involved in the modulation of the expression of many genes, including genes involved in fertility (e.g., ESR1 and OXT) and lipid metabolism pathways (e.g., CYP7A1, AOX, and ECHD). The lack of missense polymorphisms and differential expression for this gene (Wijesena et al., 2017) led us to explore isoform diversity as a genetic source of phenotypic variation. Using RNA sequencing data from the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus (ARC) of gilts with different pubertal status, we identified two NR2F2 isoforms (NR2F2-201 and NR2F2-202) with alternative transcription start sites (Figure 7). The same two transcripts were also predicted in public databases (e.g., ensembl.org). Variation in isoform expression was observed among gilts that attain puberty at different ages in the UNL population. Both isoforms were expressed in approximately 80% of the gilts, while the rest of the gilts only expressed NR2F2-201. Isoform NR2F2-201 was predominant, with the proportion of read counts per sample ranging from 87% to 100%. The expression of NR2F2-202 was higher in early pubertal gilts compared with late pubertal gilts (Padj = 0.17; Figure 8). The isoforms were translated into two distinct proteins (NR2F2-201: 414 aa peptide and NR2F2-202: 281 aa peptide). The NR2F2-201 peptide contained both a DNA-binding domain (DBD) and a ligand-binding domain (LBD) and functioned as a transcription activator via DBD and as a transcription repressor due to protein–protein interactions via LBD. The NR2F2-202 peptide only contained an LBD and mainly functioned as a transcription repressor (Yamazaki et al., 2013).

Figure 7.

Two NR2F2 isoforms (NR2F2-201 and NR2F2-202) with alternative transcription start sites identified in the hypothalamic ARC of gilts using RNA sequencing data. These gilts exhibited puberty at an earlier (< 150 d of age, n = 11) or at a later age (180 > d old n = 6).

Figure 8.

Variation in NR2F2 isoform expression (proportion of normalized read counts) was observed in the hypothalamic ARC of gilts that expressed puberty at different ages (early vs. late; n = 17). A suggestive higher expression (Padj = 0.17) of NR2F2-202 isoform was observed in early pubertal gilts compared with late puberty gilts.

The NR2F2 gene is implicated in many developmental, cell differentiation, and reproductive (e.g., fertilization and progesterone signaling during embryonic implantation) processes in mammals (Pereira et al., 2000; Takamoto et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2011; Yamazaki et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2016). Chen et al. (2016) reported an SNP located in the promoter region of NR2F2 gene that disrupts the binding site for cAMP response element-binding protein transcription factor and associated with litter size in Large White sows. Several groups have conducted mouse Nr2f2 knockout experiments and found that homozygosity for the knockout Nr2f2 (Nr2f2−/ Nr2f2−) caused embryonic lethality, while heterozygosity (Nr2f2−/ Nr2f2+) resulted in reduced fertility, including abnormal ovary and uterine morphology, absence of estrus, decreased circulating progesterone levels, and decreased litter size (Pereira et al., 2000, Takamoto et al., 2005). Klinge et al. (1997) reported that NR2F2 peptides can utilize their DBD to bind to estrogen receptor (ER) DNA elements and their LBD to directly bind to ERs, thereby, inhibiting the transcription and function of the ERs, ultimately downregulating the expression of genes induced by estrogen. On the contrary, NR2F2-202 is known to regulate the function of NR2F2-201 by inhibiting the binding of NR2F2-201 to promoters of its targeted genes (Yamazaki et al., 2013). Therefore, it can be speculated that NR2F2-201 inhibits the function of ERs via its DBD and LBD, while NR2F2-202 indirectly activates ER and transcription of estrogen-dependent genes by binding to NR2F2-201 via LBD and alleviating its negative regulation on ER. The beneficial effects of NR2F2-202 on ER activity could be a reason for higher expression of NR2F2-202 in early pubertal gilts in the UNL population. Based on the results of our research and findings by others, we hypothesized that; 1) differences in NR2F2 isoform usage are genetically or epigenetically controlled by alternative promoters (e.g., isoform-specific expression QTL as reported by Styrkarsdottir et al., 2017) and 2) differences in NR2F2 isoform usage have downstream effects on genes involved in the puberty onset (e.g., ESR1). Further characterization and investigation of NR2F2 gene are necessary to identify isoform-specific promoter variants or epigenetic markers (e.g., methylation and histone modification) and its targeted downstream genes.

Conclusions

The goal of this study was to fine map the genetic sources that explain variation in AP and other fertility traits to enable the accurate prediction of traits with low heritability and expressed late in life such as reproductive longevity. For this purpose, custom SNP arrays (SowPro90 and SowPro91) enriched in SNPs located in genes overlapping QTL regions for AP were employed.

Five QTL with the largest effects on AP were identified on four chromosomes (SSC2, SSC7, SSC14, and SSC8) using a haplotype-based GWAS. Genetic variants located in these QTL regions explained some of the variations for multiple fertility traits, including AP, LTNP, and litter size in the UNL population. Approximately, 70% of the SNPs significantly associated with AP were located in genes. Among them, P2RX3, NR2F2, PTPN11, and OAS1 were candidate genes for fertility-related phenotypes. Major SNPs associated with AP in the research population were evaluated for their effects on LTNP and litter size traits in a commercial data set. Suggestive associations were observed for some of these SNPs with litter size traits but not with LTNP. A reason for this could be that reproductive longevity is a composite phenotype and largely affected by the environment.

Overall, our research did not map loci that explain large proportions of the phenotypic variation of AP and did not define clear functional genetic variants associated with AP. Specifically, while genomic heritability for AP was 64%, the top 1% of haplotype windows only explained 3.2% of the phenotypic variation. One explanation could be that AP more or less resembles the theoretical infinitesimal model. Additionally, the initiation of female reproductive cycle is controlled by the interaction of many hormones secreted by specific cell types in the hypothalamus–pituitary–gonadal axis as well as environmental cues such as boar exposure (Soede et al., 2011). The complex nature of these hormonal interactions, their effects on downstream targets, and considerable influence of environment on these endocrine pathways make it difficult to pinpoint the causative genes and functional genetic variants within the QTL regions that are responsible for variation in AP. However, this study uncovered consistent haplotype and SNP effects in the same LD blocks that provide evidence for the presence of functional variants for AP within or in the proximity of the QTL regions. Therefore, the candidate polymorphisms can be further characterized to understand their role in gene expression, splicing process, protein sequence, and function, and how these changes affect the fertility phenotypes.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Agriculture and Food Research Initiative Competitive Grant (2013-68004-20370) and Hatch Funds from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture. We thank Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. for designing and manufacturing the SowPro90 and SowPro91 and Smithfield Premium Genetics for helping in the collection of phenotype and DNA samples for this study. The mention of a trade name, proprietary product, or specified equipment does not constitute a guarantee or warranty by the USDA and does not imply approval to the exclusion of other products that may be suitable. The USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AP

age at puberty

- ARC

arcuate nucleus

- B

batches

- BayesIM

Bayes interval mapping

- DBD

DNA-binding domain

- ER

estrogen receptors

- GEBV

genomic estimated breeding values

- GWAS

genome-wide association studies

- h 2

heritability

- LBD

ligand-binding domain

- LD

linkage disequilibrium

- LTNP

lifetime number of parities

- ME

metabolizable energy

- NBA-P1

number born alive parity 1

- NBA-P2

number born alive parity 2

- NIL

Nebraska Index Line

- NR2F2

nuclear receptor subfamily 2 group f member 2

- P2RX3

P2X purinoceptor 3

- QTL

quantitative trait loci

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- SSC

Sus scrofa chromosome

- TNB-P1

total number born parity 1

- TNB-P2

total number born parity 2

- UNL

University of Nebraska-Lincoln

- UNLe

UNL extreme gilts

- UTR

untranslated region

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no real or perceived conflicts of interest.

Literature Cited

- Barrett, J C, B Fry, J Maller, and M J Daly. . 2005. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics 21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidanel, J P2011. Biology and genetics of reproduction. In: Rothschild M F., and A Ruvinsky, editors. The genetics of the pig. 2nd ed. Wallingford (UK): CAB International; p. 218–241. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X, J Fu, and A Wang. . 2016. Expression of genes involved in progesterone receptor paracrine signaling and their effect on litter size in pigs. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 7:31. doi: 10.1186/s40104-016-0090-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habier, D, R L Fernando, K Kizilkaya, and D J Garrick. . 2011. Extension of the Bayesian alphabet for genomic selection. BMC Bioinformatics 12:186. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachman, S D. 2015. Genomic prediction model based on haplotype clusters. In: Proceedings of the Joint Statistical Meeting; August 11, 2015; Seattle (WA). Available from https://ww2.amstat.org/meetings/jsm/2015/onlinepro-gram/AbstractDetails.cfm?abstractid=314884 [accessed February 25, 2016] [Google Scholar]

- Klinge, C M, B F Silver, M D Driscoll, G Sathya, R A Bambara, and R Hilf. . 1997. Chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter-transcription factor interacts with estrogen receptor, binds to estrogen response elements and half-sites, and inhibits estrogen-induced gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 272:31465–31474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, F J, J Qin, K Tang, S Y Tsai, and M J Tsai. . 2011. Coup d’Etat: an orphan takes control. Endocr. Rev. 32:404–421. doi: 10.1210/er.2010-0021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, P S, R Moreno, and R K Johnson. . 2011. Effects of restricting energy during the gilt developmental period on growth and reproduction of lines differing in lean growth rate: responses in feed intake, growth, and age at puberty. J. Anim. Sci. 89:342–354. doi: 10.2527/jas.2010-3111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, F A, M J Tsai, and S Y Tsai. . 2000. COUP-TF orphan nuclear receptors in development and differentiation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 57:1388–1398. doi: 10.1007/PL00000624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweer, K R, S D Kachman, L A Kuehn, H C Freetly, J E Pollak, and M L Spangler. . 2018. Genome-wide association study for feed efficiency traits using SNP and haplotype models. J. Anim. Sci. 96:2086–2098. doi: 10.1093/jas/sky119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serenius, T, and K J Stalder. . 2006. Selection for sow longevity. J. Anim. Sci. 84:E166–E171. doi: 10.2527/2006.8413_supple166x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater, M, J A Barden, and C R Murphy. . 2000. The purinergic calcium channels P2X1,2,5,7 are down-regulated while P2X3,4,6 are up-regulated during apoptosis in the ageing rat prostate. Histochem. J. 32:571–580. doi: 10.1023/a:1004110529753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soede, N M, P Langendijk, and B Kemp. . 2011. Reproductive cycles in pigs. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 124:251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2011.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Styrkarsdottir, U, H Helgason, A Sigurdsson, G L Norddahl, A B Agustsdottir, L N Reynard, A Villalvilla, G H Halldorsson, A Jonasdottir, A Magnusdottir, . et al. 2017. Whole-genome sequencing identifies rare genotypes in COMP and CHADL associated with high risk of hip osteoarthritis. Nat. Genet. 49:801–805. doi: 10.1038/ng.3816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamoto, N, I Kurihara, K Lee, F J Demayo, M J Tsai, and S Y Tsai. . 2005. Haploinsufficiency of chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor II in female reproduction. Mol. Endocrinol. 19:2299–2308. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tart, J K, R K Johnson, J W Bundy, N N Ferdinand, A M McKnite, J R Wood, P S Miller, M F Rothschild, M L Spangler, D J Garrick, . et al. 2013. Genome-wide prediction of age at puberty and reproductive longevity in sows. Anim. Genet. 44:387–397. doi: 10.1111/age.12028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trenhaile, M D. 2015. Genomic analysis of sow reproductive traits: identification of selective sweeps, major genes, and genotype by diet interactions [MS Thesis]. Lincoln (NE): Animal Science Department, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. [Google Scholar]

- Trenhaile, M D, J L Petersen, S D Kachman, R K Johnson, and D C Ciobanu. . 2016. Long-term selection for litter size in swine results in shifts in allelic frequency in regions involved in reproductive processes. Anim. Genet. 47:534–542. doi: 10.1111/age.12448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijesena, H R, C A Lents, J J Riethoven, M D Trenhaile-Grannemann, J F Thorson, B N Keel, P S Miller, M L Spangler, S D Kachman, and D C Ciobanu. . 2017. GENOMICS SYMPOSIUM: Using genomic approaches to uncover sources of variation in age at puberty and reproductive longevity in sows. J. Anim. Sci. 95:4196–4205. doi: 10.2527/jas2016.1334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijesena, H R, G A Rohrer, D J Nonneman, B N Keel, J L Petersen, S D Kachman, and D C Ciobanu. . 2019. Evaluation of genotype quality parameters for SowPro90, a new genotyping array for swine1. J. Anim. Sci. 97:3262–3273. doi: 10.1093/jas/skz185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson-Wells, D F, and S D Kachman. . 2016. A Bayesian GWAS method utilizing haplotype clusters for a composite breed population. 2016. Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Applied Statistics in Agriculture; May 1 to 3, 2016; Manhattan (KS). doi: 10.4148/2475-7772.1469 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki, T, J -I Suehiro, H Miyazaki, T Minami, T Kodama, K Miyazono, and T Watabe. . 2013. The COUP-TFII variant lacking a DNA-binding domain inhibits the activation of the Cyp7a1 promoter through physical interaction with COUP-TFII. Biochem. J 452:345–357. doi: 10.1042/BJ20121200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]