Abstract

Atazanavir (ATZ) is an antiviral drug synthesized.ATZ is being investigated for potential application against the Coronavirus 2019-nCoV. To find candidate drugs for 2019-nCoV, we have carried out a computational study to screen for effective available drug ATZ which may work as an inhibitor for the Mpro of 2019-nCoV. In the present work, the first time the molecular structure of ATZ molecule has been studied using Density Functional Theory (CAMB3LYP/6-31G*) in solvent water. The electronic properties, atomic charges, MEP, NBO analysis, and excitation energies of ATZ have also been studied. The interaction of ATZ compound with the Coronavirus was performed by molecular docking studies.

Keywords: Atazanavir, Coronavirus 2019-nCoV, DFT, Molecular docking, Electronic properties

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Atazanavir with the brand name Reyataz among others is an azapeptide protease inhibitor (PI) and has been approved both by the FDA and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for the treatment of HIV infectious disease [1]. Atazanavir (ATZ) has fewer restrictions rather than other classic PIs including offering a lower pill burden, a more favorable lipid profile, and a lower incidence of gastrointestinal symptoms [1]. ATZ drug may become a new option for first-line PIs or salvage therapy in patients with moderate experience with PIs. Atazanavir is a highly selective and effective inhibitor of the HIV-1 protease enzyme. Early development studies performed in the late 1990s confirmed that it blocked the cleavage of both gag and gag-pol precursor proteins in HIV-infected cells, leading to a release of noninfectious and immature viral particles [2].Atazanavir is an azapeptide HIV-1 PI that prevents the formation of mature virions through the potent and selective inhibition of viral Gag and Gag–Pol polyprotein processing in HIV-1-infected cells [3]. Atazanavir may cause side effects. Many side effects from HIV medicines, such as nausea or occasional dizziness, are manageable. See the Clinical Info fact sheet on HYPERLINK "https://hivinfo.nih.gov/fact-sheet/hiv-medicines-and-side-effects" \t "_blank for more information. Some side effects of atazanavir can be serious. Serious side effects of atazanavir include changes in heart rhythm, severe rash, liver problems, and life-threatening drug interactions. (See section above: What are the most important things to know about atazanavir?). Other possible side effects of atazanavir include: mild rash, chronic kidney disease, Kidney stones. Contact your health care provider if you have pain in your lower back or lower stomach area, blood in your urine, or pain when urinating, gallbladder problems. Contact your health care provider right away if you develop symptoms of gallbladder problems (pain in your right or middle upper stomach area, fever, nausea and vomiting, or jaundice), diabetes and high blood sugar (hyperglycemia), changes in your immune system (called immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome or IRIS). IRIS is a condition that sometimes occurs when the immune system begins to recover after treatment with an HIV medicine. As the immune system gets stronger, it may have an increased response to a previously hidden infection, Changes in body fat (lipodystrophy syndrome), Increased bleeding problems in people with hemophilia [4], [5], [6].

According to the openly published data, in 2019, a novel Coronavirus 2019-nCoV was found to cause Severe Acute Respiratory symptoms and rapid pandemic in China. On 13, 16, and 21 January, respectively, Thailand, Japan, and Korea confirmed the detection of human infection with 2019‐nCoV from China [7]. Liu and co-workers have been suggested 10 drugs such as Colistin, Valrubicin, Icatibant, Bepotastine, Epirubicin, Epoprostenol, Vapreotide, Aprepitant, Caspofungin, Perphenazine as a candidate against 2019-nCoV coronavirus [8]. They have been studied the interaction of the mentioned drugs with the Coronavirus by molecular docking studies. To find candidate drugs for 2019-nCoV, we have performed a theoretical study for evaluating the usability of Atazanavir (C38H52N6O7) drug as an inhibitor for the Mpro of 2019-nCoV. The molecular docking approach is used to model the interaction between a molecule and a protein at the atomic level, which allows us to characterize the behavior of molecules in the binding site of target proteins as well as to elucidate fundamental biochemical processes [9,10]. We have recently suggested Triazavirin drug as a candidate against 2019-nCoV coronavirus [11]. We have been investigated the interaction of the mentioned drug with the Coronavirus by molecular docking studies. In this work, the first time the structure of the Atazanavir (ATZ) molecule has been investigated using Density Functional Theory (DFT: CAMB3LYP/6-31G*) in solvent water. The electronic properties, MEP and NBO analysis, excitation energies ATZ have also been calculated. The interaction of ATZ drug with the Coronavirus was performed by molecular docking studies.

2. Computational methods

In the current study, the first conformational analysis was performed for the compound Atazanavir (ATZ). Then, the quantum chemical calculations have been carried out for the most stable conformation using the Density Functional Theory (DFT) method at CAMB3LYP/6-31G* level of theory [12] in solvent water by the Gaussian 09W program package [13] on a Pentium IV/4.28 GHz personal computer. The Polarized Continuum Model (PCM) [14] was used for the calculations of solvent effect.We have used Time Dependent Density Functional Theory (TD-DFT) [15] for calculation of the electronic transitions of the ATZ molecule. The electronic properties such as EHOMO, ELUMO, HOMO-LUMO energy gap, dipole moment (DM), Mulliken atomic charges, and natural charge [16] of the ATZ molecule were obtained. The optimized molecule, molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) surface, HOMO, and LUMO surfaces were visualized using GaussView 05 program [17]. Interaction between the structure of Coronavirus 2019-nCoV and ATZ has been calculated by HyperChem Professional 08 [18], PyMOL, and Molegro Molecular Viewer software programs. The protein sequences of 2019-nCoV were downloaded from GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The crystal structure of SARS-CoVMpro (PDB ID: 1UJ1) was downloaded from Protein Data Bank (PDB, http://www.rcsb.org). Preparation of the protein receptor we have started with a procedure in which have deleted all water molecules and ligands except for necessary cofactors. We have examined the protein for gaps and follow procedures for building and optimizing the missing loops. We have added hydrogens and optimize the hydrogen-bonding network. Finally, we have saved cleaned structure for docking.

3. Results and discussion

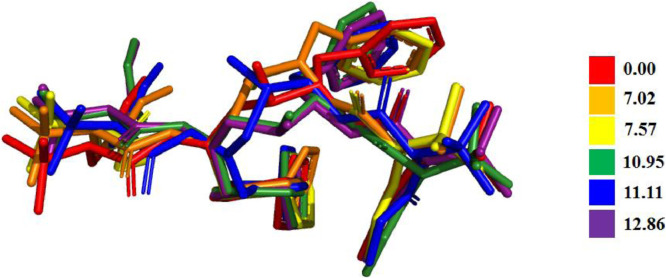

Since the Atazanavir (ATZ) molecule is flexible a conformation search was conducted first to obtain the minimal structure, the conformation search was done using the conformer distribution tool implemented in Spartan 16 software, molecular mechanics MMFF94 [19] was used with 10,000 conformers as a limit. Six conformers were identified as a minimum, further optimized at the PM6 level used to enhance the MMFF output. The energy difference was in 0.00 – 12.86 kcal/mol range (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

The obtained conformers with relative energies computed at PM6 in gas.

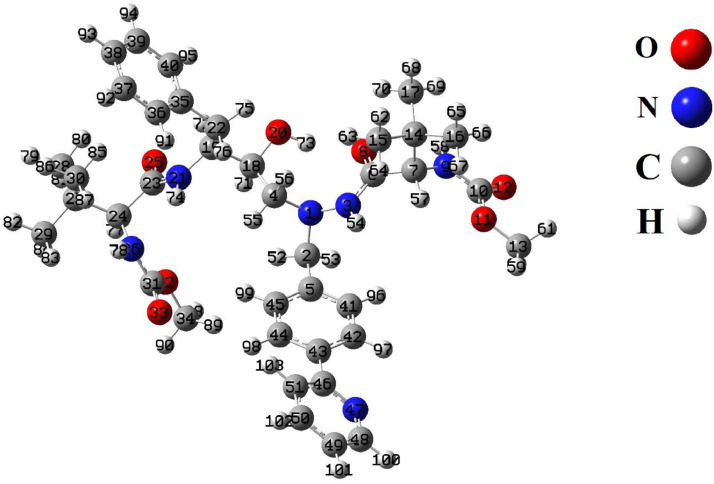

In the next step, the most stable conformation of ATZ in the ground state was optimized using CAMB3LYP/6-31G*level of theory (Fig. 2 ). The theoretical parameters such as Bond lengths (Å) and Bond angles (°) are shown in and Table 1 .

Fig. 2.

Optimized structure of the ATZ by CAMB3LYP/6-31G* method.

Table 1.

Selected optimized geometrical parameters (Bond lengths (Å) and Bond angles (°)) of the ATZ molecule.

| Bond | Bond lengths (Å) | Bond | Bond angles (Å) |

|---|---|---|---|

| N1-C2 | 1.468 | N1-C2-C5 | 115.22 |

| N1-N3 | 1.385 | N1-N3-C6 | 120.73 |

| N1-C4 | 1.469 | N1-C4-C18 | 109.03 |

| C2-C5 | 1.516 | N1-N3-H54 | 119.11 |

| N3-C6 | 1.349 | C2-N1-N3 | 112.79 |

| C4-C18 | 1.528 | C2-N1-C4 | 117.52 |

| C6-C7 | 1.529 | N3-N1-C4 | 114.97 |

| C6-O8 | 1.233 | N3-C6-C7 | 115.75 |

| C7-N9 | 1.454 | N3-C6-O8 | 123.09 |

| C7-C14 | 1.561 | C7-C6-O8 | 121.15 |

| C14-C15 | 1.534 | C7-N9-H58 | 117.11 |

| C14-C16 | 1.534 | C6-C7-C14 | 113.52 |

| C14-C17 | 1.533 | N9-C7-C14 | 112.77 |

| N9-C10 | 1.353 | C7-C14-C17 | 111.97 |

| C5-C41 | 1.398 | N9-C10-O11 | 112.87 |

| C5-C45 | 1.397 | N9-C10-O12 | 123.62 |

| C10-O11 | 1.342 | C10-O11-C13 | 116.13 |

| C10-O12 | 1.225 | O11-C10-O12 | 123.49 |

| O11-C13 | 1.433 | C15-C14-C17 | 109.52 |

| C18-C19 | 1.538 | C16-C14-C17 | 109.23 |

| C18-O20 | 1.418 | C18-O20-H73 | 109.20 |

| C19-N21 | 1.456 | C19-N21-C23 | 122.96 |

| C19-C22 | 1.533 | C19-N21-H74 | 119.20 |

| N21-C23 | 1.348 | C19-C22-C35 | 114.14 |

| C22-C35 | 1.511 | N21-C19-C22 | 110.94 |

| C23-O25 | 1.232 | N21-C23-O25 | 122.90 |

| C23-C24 | 1.537 | C22-C35-C36 | 120.84 |

| C24-N26 | 1.457 | C23-C24-N26 | 111.91 |

| C24-C27 | 1.561 | C23-C24-C27 | 103.68 |

| C27-C28 | 1.535 | C24-N26-H78 | 119.64 |

| C27-C29 | 1.536 | N26-C31-C32 | 112.22 |

| C27-C30 | 1.534 | N26-C31-O33 | 123.94 |

| N26-C31 | 1.357 | C28-C27-C30 | 108.85 |

| C31-O32 | 1.341 | C29-C27-C30 | 109.81 |

| C31-O33 | 1.224 | C31-O32-C34 | 116.31 |

| O32-C34 | 1.434 | O32-C31-O33 | 123.82 |

| C35-C36 | 1.395 | C35-C36-C37 | 121.03 |

| C35-C40 | 1.398 | C41-C42-C43 | 120.73 |

| C36-C37 | 1.393 | C42-C43-C44 | 118.23 |

| C37-C38 | 1.391 | C42-C43-C46 | 120.25 |

| C38-C39 | 1.394 | C43-C44-C45 | 120.87 |

| C39-C40 | 1.391 | C43-C46-N47 | 116.87 |

| N3-H54 | 1.016 | C44-C43-C46 | 121.49 |

| N9-H58 | 1.011 | C46-N47-C48 | 118.59 |

| N21-H74 | 1.011 | C48-C49-C50 | 117.90 |

| N26-H78 | 1.010 | C49-C50-C51 | 118.98 |

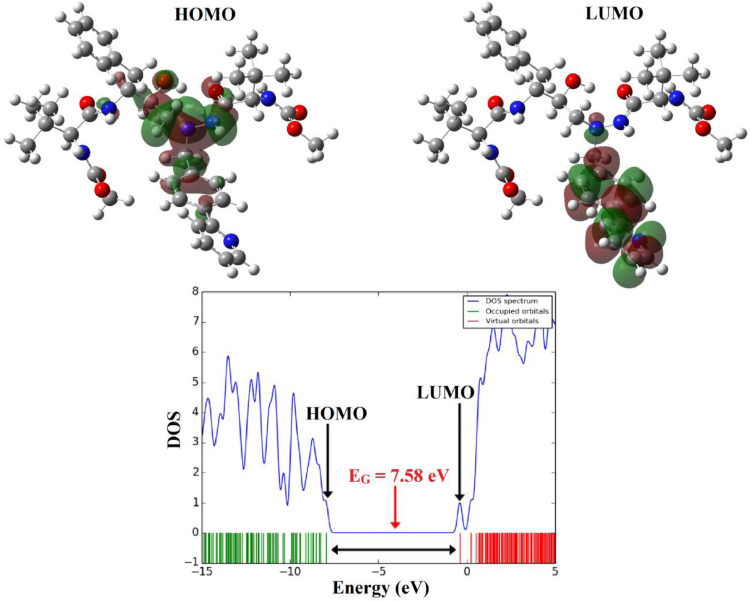

The HOMO and LUMO orbitals are the frontier molecular orbitals (FMOs) that have an important role in chemical stability, optical properties, UV/Vis spectrum, and kinetic reactivity properties of the molecules [20]. The energy difference between HOMO and LUMO orbitals shows an energy gap (Eg) which is related to the hardness or softness of molecules. We obtained the theoretical energies of HOMO (EHOMO) and the LUMO (ELUMO) orbitals and the electronic properties of the ATZusing CAMB3LYP/6-31G* level of theory; the results are reported in Table 2 . Fig. 3 shows the pictures of HOMO and LUMO orbitals. The HOMO orbital of ATZ is mainly centralized on the nitrogen atoms (N1 and N3), the oxygen atom of the carbonyl group (O8), and the oxygen atom of the hydroxyl group (O20), whereas the LUMO orbital is centralized on the N1 atom, double bonds (-C=C- and –C=N-) of one of phenyl rings and pyrimidine ring. Therefore, most of the charge transfer from the HOMO to LUMO in ATZ takes place with the contribution of lone pairs of and pi (π) bonds. The EG value of ATZ was calculated at about 7.5804 eV. The EHOMO and ELUMO are related to the ionization potential (I=-EHOMO) and the electron affinity (A=-ELUMO). The global hardness (η), electronegativity (χ), electronic chemical potential (µ) and electrophilicity (ω), and chemical softness (S) parameters of the ATZ are calculated with the following equations [21], [22], [23], [24]:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

in which is reported in Table 2. The density of states spectrum (DOS) of the ATZis shown in Fig. 3.

Table 2.

The calculated electronic properties of the ATZ.

| Property | CAMB3LYP |

|---|---|

| Electronic Energy (a.u.) | -2333.453 |

| DM (Debye) | 14.33 |

| Point Group | C1 |

| EHOMO (eV) | -7.9710 |

| ELUMO (eV) | -0.3906 |

| Eg (eV) | 7.5804 |

| I (eV) | 7.97 |

| A (eV) | 0.39 |

| χ (eV) | 4.18 |

| η (eV) | 3.79 |

| μ (eV) | -4.18 |

| ω (eV) | 2.30 |

| S (eV) | 0.13 |

Fig. 3.

The shape of HOMO and LUMO orbitals and DOS plot of the molecule ATZ.

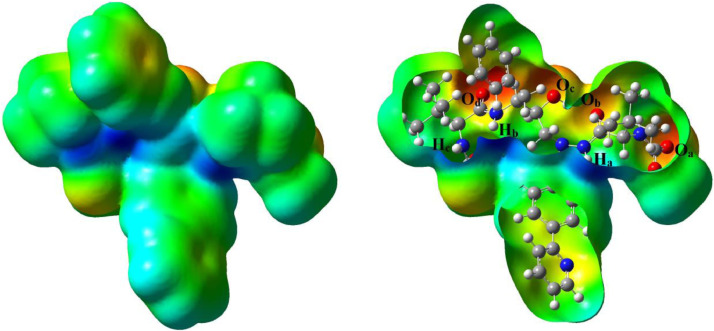

The MEP map of the optimized molecule ATZ was computed and given in Fig. 4 . The MEP surface of the molecule is related to the electronegativity, the electrophilic, and nucleophilic reactive of the molecules and the partial charges on the different atoms [25]. The difference of the electrostatic potential at the maps is shown in different colors. The electron-rich sites, partially negative charge, slightly electron-rich regions, positive charge or electron-poor and neutral sites in the MEP maps appear as red, orange, yellow, blue, and green colors, respectively [26]. In the MEP map of ATZ, the oxygen atoms such as Oa, Ob, Oc, Od with red color display electron rich regions, which is due to the lone pair electrons. The hydrogen atoms such as Ha, Hb, Hc with blue color show the electron-poor and electrophilic sites. The regions with green color show the sites with zero potential and neutral regions. The electrophilic and nucleophilic regions of the ATZ illustrate the interaction with other molecules in chemical reactions.

Fig. 4.

MEP map of the molecule ATZ.

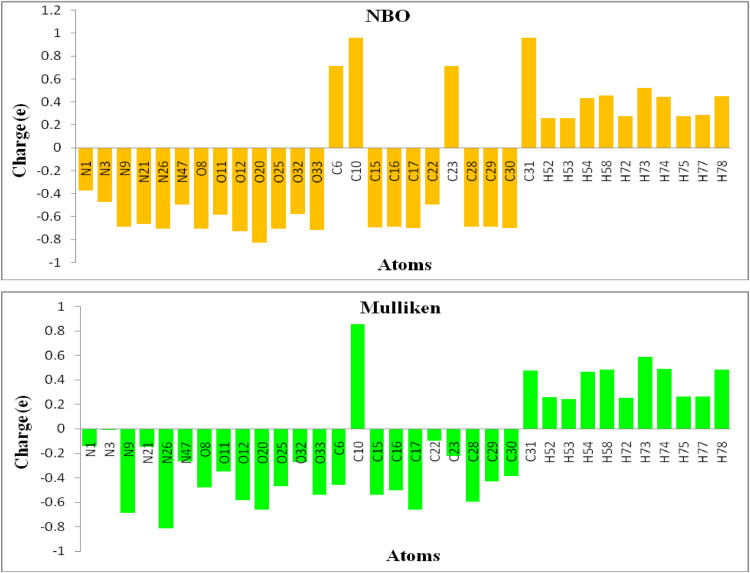

The calculated Mulliken atomic and natural charges of the ATZ molecule are summarized in Table 3 and the diagrams of charges are shown in Fig. 5 . The atomic charges have an important role in the prediction of the electrophilic and nucleophilic reactive regions of the molecules. The atomic charges can be illustrated the parameters such as dipole moments, electronic structures, polarizability, and chemical reactivity of molecules. The Mulliken and natural charges for the oxygen and nitrogen atoms are the negative values. The O20 atom has the highest negative charge (NBO: -0.824e and Mulliken: -0.663e) comparing with other oxygen atoms and the N26 atom has the highest negative charge (NBO: -0.824e and Mulliken: -0.663e) rather than other nitrogen atoms. All the hydrogen atoms display a positive charge.The H54, H58, H73, H74, H78 atoms have the highest positive charge about rather than other hydrogen atoms due to the attachment to electron-withdrawing nitrogen (nitro group) and oxygen atoms (hydroxyl group).

Table 3.

The selected calculated Mulliken and NBO charges (e) of the ATZ.

| Atoms | NBO | Mulliken |

|---|---|---|

| N1 | -0.372 | -0.139 |

| N3 | -0.469 | -0.008 |

| N9 | -0.684 | -0.689 |

| N21 | -0.664 | -0.146 |

| N26 | -0.700 | -0.814 |

| N47 | -0.490 | -0.264 |

| O8 | -0.700 | -0.478 |

| O11 | -0.580 | -0.346 |

| O12 | -0.723 | -0.586 |

| O20 | -0.824 | -0.663 |

| O25 | -0.704 | -0.470 |

| O32 | -0.576 | -0.270 |

| O33 | -0.716 | -0.537 |

| C6 | 0.715 | -0.457 |

| C10 | 0.959 | 0.855 |

| C15 | -0.692 | -0.538 |

| C16 | -0.686 | -0.504 |

| C17 | -0.694 | -0.660 |

| C22 | -0.491 | -0.095 |

| C23 | 0.713 | -0.220 |

| C28 | -0.684 | -0.592 |

| C29 | -0.686 | -0.432 |

| C30 | -0.694 | -0.386 |

| C31 | 0.960 | 0.482 |

| H52 | 0.263 | 0.259 |

| H53 | 0.263 | 0.246 |

| H54 | 0.437 | 0.471 |

| H58 | 0.459 | 0.486 |

| H72 | 0.277 | 0.253 |

| H73 | 0.525 | 0.590 |

| H74 | 0.449 | 0.489 |

| H75 | 0.278 | 0.265 |

| H77 | 0.291 | 0.266 |

| H78 | 0.453 | 0.487 |

Fig. 5.

Mulliken andnatural charges distribution of the ATZ.

NBO analysis is an important method for investigation of intra- and inter-molecular bonding and interaction between bonds and studying charge transfer in molecules [27]. The filled and empty NBOs and the stabilization energy (E(2)) calculated from the second-order micro disturbance theory of the ATZ molecule are represented in Table 4 .

Table 4.

Significant donor–acceptor interactions and second order perturbation energies of the ATZ.

| Donor (i) | Occupancy | Acceptor (j) | Occupancy | E(2)akcal/mol | E(j)-E(i)ba.u. | F(i, j)ca.u. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| σ(N3-C6) | 1.98979 | σ*(N1-C2) | 0.03037 | 1.18 | 1.35 | 0.036 |

| σ(C7-N9) | 1.98077 | σ*(C10-O12) | 0.29975 | 1.06 | 1.01 | 0.032 |

| σ(C14-C15) | 1.97710 | σ*(C16-H66) | 0.00655 | 1.92 | 1.19 | 0.043 |

| σ(N21-C23) | 1.98929 | σ*(C19-N21) | 0.02812 | 1.68 | 1.34 | 0.043 |

| σ(C31-O33) | 1.99190 | σ*(N26-C31) | 0.06423 | 1.32 | 1.59 | 0.041 |

| σ(C41-C42) | 1.97881 | σ*(C43-C46) | 0.03426 | 3.66 | 1.30 | 0.062 |

| π(C5-C45) | 1.64737 | π*(C41-C42) | 0.31237 | 28.63 | 0.036 | 0.092 |

| π*(C43-C44) | 0.35947 | 31.12 | 0.36 | 0.095 | ||

| π(C35-C36) | 1.65717 | π*C37-C38) | 0.33006 | 31.45 | 0.036 | 0.095 |

| π*(C39-C40) | 0.32465 | 29.00 | 0.36 | 0.092 | ||

| π(C37-C38) | 1.67086 | π*(C35-C36) | 0.33704 | 28.67 | 0.37 | 0.092 |

| π*(C39-C40) | 0.32465 | 30.63 | 0.36 | 0.094 | ||

| π(C39-C40) | 1.67400 | π*(C35-C36) | 0.33704 | 30.74 | 0.37 | 0.095 |

| π*(C37-C38) | 0.33006 | 29.15 | 0.36 | 0.092 | ||

| π(C41-C42) | 1.65951 | π*(C5-C45) | 0.35149 | 31.04 | 0.37 | 0.095 |

| π*(C43-C44) | 0.35947 | 29.31 | 0.36 | 0.093 | ||

| π(C43-C44) | 1.63676 | π*(C5-C45) | 0.35149 | 30.62 | 0.36 | 0.094 |

| π*(C41-C42) | 0.31237 | 29.15 | 0.36 | 0.093 | ||

| π*(C46-N47) | 0.42196 | 16.79 | 0.33 | 0.067 | ||

| π(C46-N47) | 1.70909 | π*(C48-C49) | 0.30173 | 37.89 | 0.41 | 0.112 |

| π*(C50-C51) | 0.29704 | 18.15 | 0.41 | 0.077 | ||

| π(C48-C49) | 1.63073 | π*(C46-N47) | 0.42196 | 26.27 | 0.34 | 0.085 |

| π*(C50-C51) | 0.29704 | 33.83 | 0.37 | 0.101 | ||

| π(C50-C51) | 1.64304 | π*(C46-N47) | 0.42196 | 42.21 | 0.34 | 0.109 |

| π*(C48-C49) | 0.30173 | 25.28 | 0.36 | 0.087 | ||

| π*(C46-N47) | 0.42196 | π*(C48-C49) | 0.30173 | 165.42 | 0.02 | 0.094 |

| π*(C50-C51) | 0.29704 | 171.64 | 0.03 | 0.100 | ||

| n1(N1) | 1.89493 | σ*(C2-C5) | 0.03299 | 8.71 | 0.82 | 0.077 |

| σ*(N3-H54) | 0.03212 | 9.55 | 0.82 | 0.081 | ||

| n1(N3) | 1.68960 | π*(C6-O8) | 0.29581 | 82.19 | 0.39 | 0.161 |

| n2(O8) | 1.87349 | σ*(N3-C6) | 0.07037 | 25.30 | 0.88 | 0.135 |

| σ*(C6-C7) | 0.06443 | 22.00 | 0.76 | 0.118 | ||

| n1(N9) | 1.73155 | σ*(C10-O12) | 0.29975 | 47.73 | 0.49 | 0.138 |

| n1(O11) | 1.95784 | π*(C10-O12) | 0.11541 | 9.11 | 1.12 | 0.092 |

| n2(O11) | 1.82707 | σ*(C10-O12) | 0.29975 | 32.51 | 0.57 | 0.126 |

| n2(O12) | 1.85596 | σ*(N9-C10) | 0.06299 | 24.61 | 0.86 | 0.133 |

| σ*(C10-O11) | 0.09572 | 36.98 | 0.75 | 0.151 | ||

| n1(N21) | 1.68253 | π*(C23-O25) | 0.28366 | 76.25 | 0.40 | 0.158 |

| n2(O25) | 1.88365 | σ*(N21-C23) | 0.06630 | 27.02 | 0.88 | 0.140 |

| σ*(C23-C24) | 0.07220 | 22.01 | 0.75 | 0.116 | ||

| n1(N26) | 1.74199 | π*(C31-O33) | 0.33447 | 59.38 | 0.42 | 0.144 |

| n1(O32) | 1.95858 | σ*(C31-O33) | 0.06865 | 10.65 | 1.20 | 0.102 |

| n2(O32) | 1.82199 | π*(C31-O33) | 0.33447 | 45.51 | 0.50 | 0.140 |

| n2(O33) | 1.85515 | σ*(N26-C31) | 0.06423 | 24.93 | 0.86 | 0.133 |

| σ*(C31-O32) | 0.09568 | 37.03 | 0.76 | 0.151 | ||

| n1(N47) | 1.92555 | σ*(C46-C51) | 0.03136 | 11.16 | 1.03 | 0.097 |

| σ*(C48-C49) | 0.02559 | 10.76 | 1.04 | 0.096 |

E(2) Energy of hyperconjucative interactions,

Energy difference between donor and acceptor i and j NBO orbitals,

F(i, j) is the Fock matrix element between i and j NBO orbitals.

The electron delocalization from the electron donor orbitals to the electron acceptor orbitals represented a conjugative electron transfer process between them [28]. For each electron donor orbital (i) and electron acceptor orbital (j), the interacting stabilization energy E(2) associated with the delocalization i→j is computed according to the following equation [28]:

| (6) |

in which qi is the electron donor orbital occupancy, εj and εi are diagonal elements and F(i,j) is the off-diagonal NBO Fock matrix element [27]. The stabilization energy (E(2)) shows the value of the participation of electrons in the resonance between atoms [27]. The greater E(2) value, the most intensive is the interaction between donor and acceptor orbitals, i.e. the more donation tendency from electron donors to electron acceptors and the most extent of conjugation of the whole molecule. NBO analysis has been performed for the ATZ molecule using CAMB3LYP/6-31G* level of theory. The selected intramolecular hyperconjugative interactions of the ATZsuch as π→π*, π*→π*, σ→σ*, n→π* and n→σ* transitions are reported in Table 4. According to obtained results, the important π→π* transitions of aryl rings is observed for π(C4-C45)→π*(C43-C44), π(C35-C36)→π*(C37-C38), π(C41-C42)→π*(C5-C45), π(C46-N47)→π*(C48-C49), π(C48-C49)→π*(C50-C51), π(C50-C51)→π*(C46-N47) interactions with stabilization energies (E(2)) of 31.12 kcal/mol, 31.45 kcal/mol, 31.04 kcal/mol, 37.89 kcal/mol, 33.83 kcal/mol, 42.21 kcal/mol respectively, and the π(C50-C51)→π*(C46-N47) interaction at the pyrimidine ring has the higher resonance energy (42.21 kcal/mol) rather than other π→π* interactions.The highest resonance energies of the ATZis observed for π*(C46-N47)→σ*(C48-C49) and π*(C46-N49)→π*(C50-C51) transitions at the pyrimidine ring with stabilization energies of 165.42 kcal/mol and 171.64 kcal/mol, respectively. The n1(N3)→π*(C6-O8), n1(N21)→π*(C23-O25), n1(N26)→π*(C31-O33),n2(O32)→π*(C31-O33) interactions have the highest resonance energies (E(2)) of n→π* with values of 82.19 kcal/mol, 76.25 kcal/mol, 59.38 kcal/mol, 45.51 kcal/mol, respectively. The important n→σ* transition is observed for n1(N9)→σ*(C10-O12) with resonance energy (E(2)) of 47.73 kcal/mol.

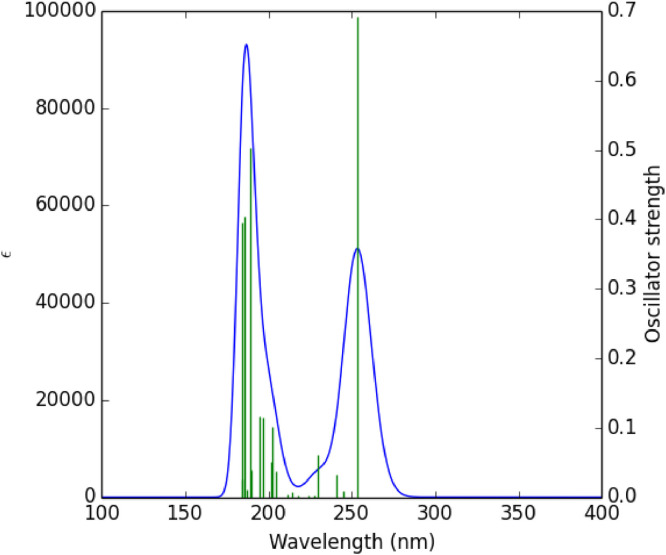

The theoretical UV spectrum of ATZ was calculated using the TD-CAMB3LYP/6-31G* method. The calculated absorption wavelength (λ = 100-400 nm), excitation energies (E), oscillator strength (f) greater than 0.1, and the participating orbitals in the electronic transitions are reported in Table 5 . According to results, the λmax appears at 253.70 nm and the oscillator strength f = 0.69 that is due to charge transfer of one electron into the excited singlet state S 0→S 1 with the participation of three configurations including H→L (85%), H-2→L (2%), H→L+1 (3%). Excitation of an electron from HOMO to LUMO [H→L (85%)] is the main contribution for the formation of the absorption band at λmax = 253.70 nm. As previously mentioned, the electronic transitions from HOMO to LUMO at the λmax are due to the contribution of pi (π) bonds and lone pairs including π→π* and n→π*.The calculated UV spectrum of the ATZ molecule is shown in Fig. 6 .

Table 5.

Electronic absorption spectrum of the ATZ molecule calculated by CAM-B3LYP/6-31G* method.

| Excited State | Wavelength (nm) | Excitation Energy (Ev) | Configurations Composition (corresponding transition orbitals) | Oscillator Strength (f) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S0→S1 | 253.70 | 4.88 | H→L (85%), H-2→L (2%), H→L+1 (3%) | 0.69 |

| S0→S11 | 202.55 | 6.12 | H-5→L (16%), H→L+3 (11%), H-9→L (7%), H-2→L+2 (2%), H-2→L+3 (2%), H-2→L+11 (9%), H-2→L+13 (9%), H→L+1 (8%), H→L+2 (7%) | 0.10 |

| S0→S13 | 196.94 | 6.29 | H-9→L (12%), H-5→L+3 (11%), H→L+2 (21%), H-13→L (5%), H-9→L+1 (3%), H-5→L (3%), H-5→L+1 (6%), H-5→L+2 (4%), H→L+3 (3%), H→L+7 (2%), H→L+8 (2%), H→L+20 (4%) | 0.11 |

| S0→S14 | 194.57 | 6.37 | H→L+2 (19%), H→L+7 (17%), H-13→L (5%), H-12→L (4%), H-9→L+1 (3%), H-5→L+1 (5%), H-5→L+2 (4%), H-5→L+3 (9%), H→L+1 (3%), H→L+3 (2%), H→L+4 (4%), H→L+16 (3%) | 0.12 |

| S0→S18 | 185.74 | 6.67 | H-9→L+1 (14%), H-5→L+1 (13%), H-13→L (8%), H-12→L (7%), H-12→L+1 (4%), H-5→L+3 (3%), H-2→L+2 (4%), H→L+1 (3%), H→L+3 (6%), H→L+4 (3%), H→L+13 (2%), H→L+20 (3%) | 0.40 |

| S0→S20 | 184.22 | 6.73 | H-3→L+2 (10%), H-3→L+4 (11%), H-3→L+6 (24%), H-1→L+6 (14%) H-3→L+3 (6%), H-3→L+7 (3%), H-3→L+9 (5%), H-2→L+2 (2%), H-1→L+4 (6%) | 0.39 |

*H-HOMO, L-LUMO

**In these table the transitions with f ≥ 0.1 are presented.

Fig. 6.

UV spectra of the ATZ molecule calculated by TD-CAMB3LYP/6-31G* method.

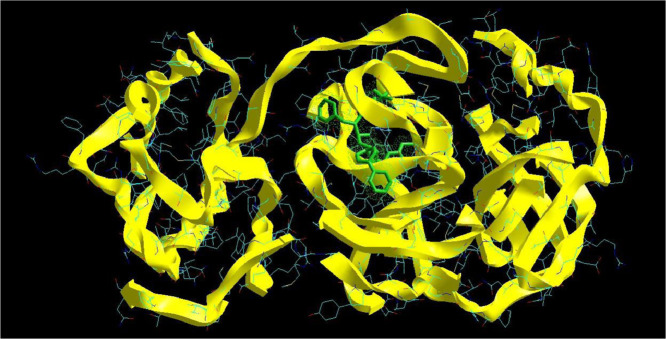

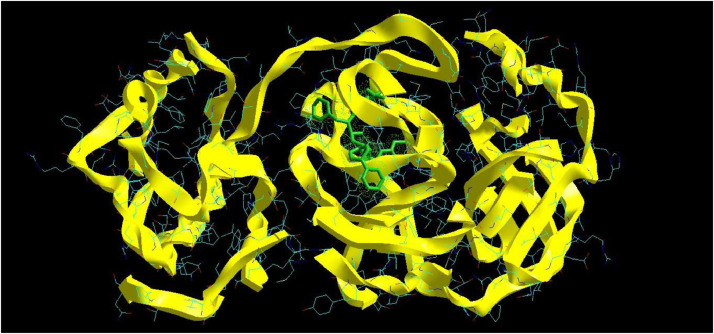

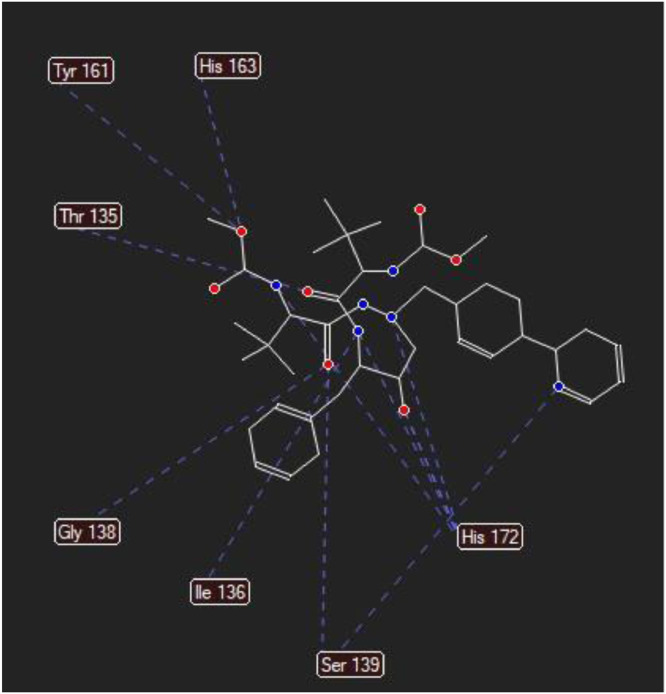

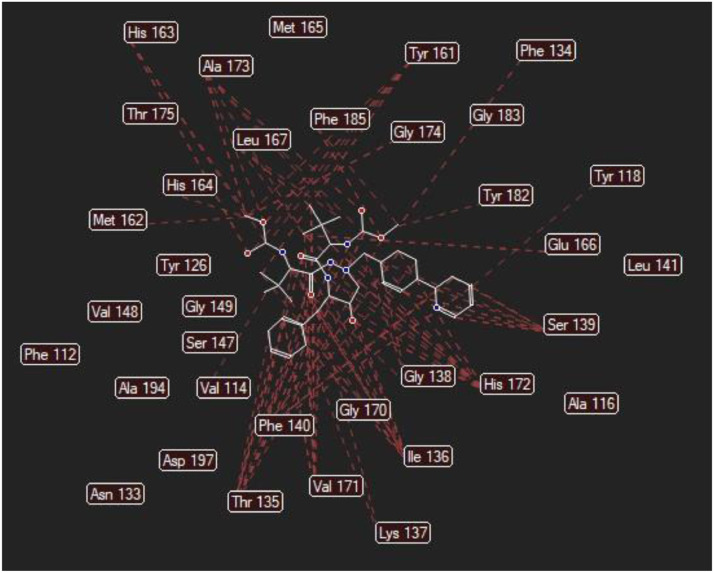

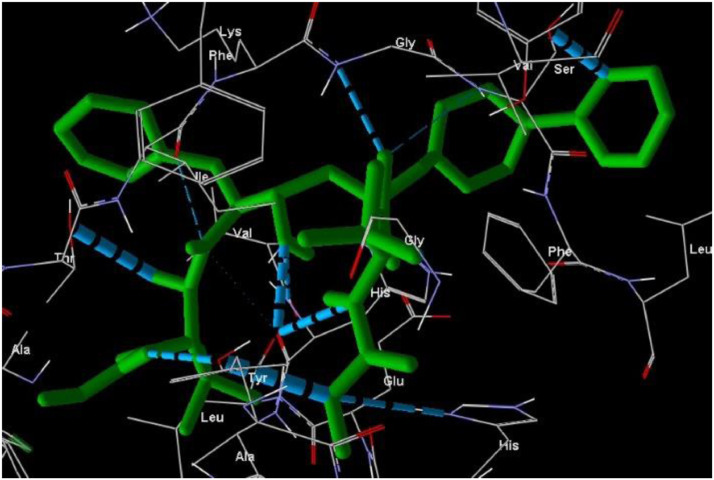

The molecular docking analysis is an important tool for drug design and molecularstructural biology [29]. The aim of molecular docking analysis is to predict the preferred binding location,affinity, and activity of drug molecules and their protein targets. In the present work, the moleculardocking studies of the Atazanavir molecule were performed against Coronavirus 2019-nCoV using HyperChem Professional 08, Molegro Molecular Viewer software programs. The molecular basis of interactions between Coronavirus 2019-nCoV molecule and the Atazanavir canbe understood with the help of docking analysis and interactions as observed in Fig. 7 . We found 4 positions in which there is a strong interaction between the drug molecule Atazanavir and the Coronavirus 2019-nCoV that leads to the destruction of the protein structure. The best position is presented here (Fig. 7). The binding energy for Coronavirus 2019-nCoV and Atazanavir is -64.29 kcal/mol in which shows a good bindingaffinity between the Atazanavir and 2019-nCoV. As seen from Fig. 8 and Table 6 twelve hydrogen bonding formation between reduces Tyr 161, His 163, Thr 135, Gly 138, and His 172 bonded with O atom, Lie 136 and His 172 bonded with N atoms of the Atazanavir are observed. Steric interactions between the Atazanavir and Coronavirus 2019-nCoV are presented in Fig. 9 .It was found that the ligand Atazanavir shows the best affinity towards of the 2019-nCoV compared to other known antiviral drugs: Colistin, Valrubicin, Icatibant, Bepotastine, Epirubicin, Epoprostenol, Vapreotide, Aprepitant in which the binding energy for Coronavirus 2019-nCoV and them is -11.206, -10.934, -9.607, -10.273, -9.091, 10.582, -9.892 and -11.376 kcal/mol that shows the weak binding affinity between them and 2019-nCoV [8]. Molecular docking energy data for mentioned ligand and hydrogen bonding are presented in Table 6 and Fig. 10 .

Fig. 7.

Interaction of Atazanavir with Coronavirus 2019-nCoV.

Fig. 8.

Docking hydrogen bonds interactions between the Atazanavir and Coronavirus 2019-nCoV.

Table 6.

Molecular docking energy data for mentioned ligand and hydrogen bonding.

| Protein | Bonded residues | ID | Hydrogen bond | Bond distance (Å) | Binding energy (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019-nCoV | Tyr | 161 | 1 | 1.4390 | -5.1104 |

| 2019-nCoV | His | 163 | 1 | 1.2878 | -6.5378 |

| 2019-nCoV | Thr | 135 | 1 | 1.4967 | -4.2558 |

| 2019-nCoV | Thr | 135 | 1 | 1.5033 | -5.4066 |

| 2019-nCoV | Gly | 138 | 1 | 2.5685 | -4.7547 |

| 2019-nCoV | Lie | 136 | 1 | 1.9035 | -4.9637 |

| 2019-nCoV | Ser | 139 | 1 | 2.8756 | -5.1167 |

| 2019-nCoV | Ser | 139 | 1 | 3.1103 | -4.7890 |

| 2019-nCoV | His | 172 | 1 | 2.0245 | -6.5234 |

| 2019-nCoV | His | 172 | 1 | 2.5439 | -5.2279 |

| 2019-nCoV | His | 172 | 1 | 2.0632 | -4.1191 |

| 2019-nCoV | His | 172 | 1 | 2.1195 | -5.5631 |

Fig. 9.

Steric interactions between the Atazanavir and Coronavirus 2019-nCoV.

Fig. 10.

Molecular docking of the Atazanavir to Coronavirus 2019-nCoV.

4. Conclusion

In this work, the quantum chemical calculations were carried out for the Atazanavir (ATZ) compound. The geometrical optimized bond lengths and bond angles were calculated theoretically. The HOMO orbital of ATZ is centralized on the N1, N3, O8, and O20, whereas the LUMO orbital is centralized on the N1 atom, double bonds (-C=C- and -C=N-) of one of phenyl and pyrimidine rings. Most of the charge transfer from the HOMO to LUMO in ATZ takes place with the contribution of lone pairs of and pi (π) bonds. The EG value of ATZ was calculated at about 7.58 eV. In the MEP map of ATZ, the oxygen atoms such as Oa, Ob, Oc, Od with red color display electron-rich regions which is due to the lone pair electrons, whereas the hydrogen atoms such as Ha, Hb, Hc with blue color show the electron-poor and electrophilic sites. The O20 atom has the highest negative charge (NBO: -0.824e and Mulliken: -0.663e) comparing with other oxygen atoms and the N26 atom has the highest negative charge (NBO: -0.824e and Mulliken: -0.663e) rather than other nitrogen atoms. The theoretical λmax appears at 257.70 nm and the oscillator strength f = 0.69 is due to the charge transfer of one electron into the excited singlet state S 0→S 1. The binding energy for Coronavirus 2019-nCoV and Atazanavir is -64.29 kcal/mol in which shows a good bindingaffinity between the Atazanavir and 2019-nCoV. Atazanavir can be used to treat the coronavirus pandemic.

Declaration of Competing Interest

I am Prof.Siyamak Shahab claim that is no conflict between authors of the MS.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129461.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Deeks S.G., Hecht F.M., Swanson M., Elbeik T., Loftus R., Cohen P.T., Grant R.M. HIV RNA and CD4 cell count response to protease inhibitor therapy in an urban AIDS clinic: response to both initial and salvage therapy. AIDS. 1999;13:F35–F43. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199904160-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fuster D., Clotet B. Review of atazanavir: a novel HIV protease inhibitor. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2005;6:1565–1572. doi: 10.1517/14656566.6.9.1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson B.S., Riccardi K.A., Gong Y.F., Guo Q., Stock D.A., Blair W.S., Terry B.J., Deminie C.A., Djang F., Colonno R.J., Lin P.F. BMS-232632, a highly potent human immunodeficiency virus protease inhibitor that can be used in combination with other available antiretroviral agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2093–2099. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.8.2093-2099.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cleijsen R.M.M., van de Ende M.E., Kroon F.P., Verduyn Lunel F., Koopmans P.P., Gras L., de Wolf F., Burger D.M. Therapeutic drug monitoring of the HIV protease inhibitor atazanavir in clinical practice. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007;60:897–900. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wood R. Atazanavir: its role in HIV treatment. Expert. Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2008;6:785–796. doi: 10.1586/14787210.6.6.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Achenbach Ch.J., Darin K.M., Murphy R.L., Katlama Ch. Atazanavir/ritonavir-based combination antiretroviral therapy for treatment of HIV-1 infection in adults. Future Virol. 2011;6:157–177. doi: 10.2217/fvl.10.89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li G., Fan. Y., Lai Y., Han T., Li Z., Zhou P., Pan P., Wang W., Hu D., Liu X., Zhang Q., Wu J. Coronavirus infections and immune responses. J. Med. Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu X., Wang X.J. Potential inhibitors against 2019-nCoV coronavirus M protease from clinically approved medicines. J. Genet. Genomics. 2020;47:119–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2020.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meng X.Y., Zhang H.X., Mezei M., Cui M. Molecular Docking: A powerful approach for structure-based drug discovery. Curr. Comput. Aided. Drug Des. 2011;7:146–157. doi: 10.2174/157340911795677602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Ruyck J., Brysbaert G., Blossey R., Lensink M.F. Molecular docking as a popular tool in drug design, an in silico travel. Adv. Appl. Bioinforma. Chem. 2016;9:1–11. doi: 10.2147/AABC.S105289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shahab S., Sheikhi M. Triazavirin- Potential inhibitor for 2019-nCoV Coronavirus M protease: A DFT study. Curr. Mol. Med. 2020 doi: 10.2174/1566524020666200521075848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Tawada Y., Tsuneda T., Yanagisawa S., Yanai T., Hirao K. A long-range-corrected time-dependent density functional theory. J. Chem. Phys. 2004;120:8425–8433. doi: 10.1063/1.1688752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yanai T., Tew D.P., Handy N.C. A new hybrid exchange-correlation functional using the Coulomb-attenuating method (CAM-B3LYP) Phys. Chem. Lett. 2004;393:51–57. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frisch M.J., Trucks G.W., Schlegel H.B., Scuseria G.E., Robb M.A., Cheeseman J.R., Scalmani G., Barone V., Mennucci B., Petersson G.A., Nakatsuji H., Caricato M., Li X., Hratchian H.P., Izmaylov A.F., Bloino J., Zheng G., Sonnenberg J.L., Hada M., Ehara M., Toyota K., Fukuda R., Hasegawa J., Ishida M., Nakajima T., Honda Y., Kitao O., Nakai H., Vreven T., Montgomery J.A., Jr., Peralta J.E., Ogliaro F., Bearpark M., Heyd J.J., Brothers E., Kudin K.N., Staroverov V.N., Kobayashi R., Normand J., Raghavachari K., Rendell A., Burant J.C., Iyengar S.S., Tomasi J., Cossi M., Rega N., Millam J.M., Klene M., Knox J.E., Cross J.B., Bakken V., Adamo C., Jaramillo J., Gomperts R., Stratmann R.E., Yazyev O., Austin A.J., Cammi R., Pomelli C., Ochterski J.W., Martin R.L., Morokuma K., Zakrzewski V.G., Voth G.A., Salvador P., Dannenberg J.J., Dapprich S., Daniels A.D., Farkas Ö., Foresman J.B., Ortiz J.V., Cioslowski J., Fox D.J. Gaussian, Inc.; Wallingford CT: 2009. Gaussian 09 revision A02. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomasi J., Mennucci B., Cammi R. Quantum mechanical continuum solvation models. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:2999–3093. doi: 10.1021/cr9904009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Runge E., Gross E.K.U. Density-functional theory for time-dependent systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1984;52:997–1000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shahab S., Filippovich L., Sheikhi M., Kumar R., Dikusar E., Yahyaei H., Muravsky A. Polarization, excited states, trans-cis properties and anisotropy of thermal and electrical conductivity of the 4-(phenyldiazenyl)aniline in PVA matrix. J. Mol. Struct. 2017;1141:703–709. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frisch A., Nielson A.B., Holder A.J. Gaussian Inc.; Pittsburgh, PA: 2000. GAUSSVIEW User Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 18.HyperChem™ Professional Release 8.0 for window molecular modeling system, dealer: copyright © 2002 Hypercube Inc.

- 19.Halgren T.A. Merck molecular force field. I. Basis, from, scope, parameterization, and performance of MMFF94. J. Comput. Chem. 1996;17:490–519. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shahab S., Sheikhi M., Filippovich L., Dikusar E., Rouhani M., Pazniak A., Kumar R. Molecular investigations of the new synthesized azomethines as antioxidants: theoretical and experimental studies. Curr. Mol. Med. 2019;19:419–433. doi: 10.2174/1566524019666190509102620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parr R.G., Szentpály L.V., Liu S. Electrophilicity index. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:1922–1924. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chattaraj P.K., Roy D.R. Update 1 of: electrophilicity index. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:PR46–PR74. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parr R.G., Yang W. Oxford University Press; New York, NY, USA: 1989. Density Functional Theory of Atoms and Molecules. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pearson R.G. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim; Germany: 1997. Chemical Hardness: Applications from Molecules to Solids. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheikhi M., Shahab S., Filippovich L., Yahyaei H., Dikusar E., Khaleghian M. New derivatives of (E,E)-azomethines: Design, quantum chemical modeling, spectroscopic (FT-IR, UV/Vis, polarization) studies, synthesis and their applications: Experimental and theoretical investigations. J. Mol. Struct. 2018;1152:368–385. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shahab S., Sheikhi M., Khaleghian M., Sharifi Sh, Kaviani S. Theoretical study of interaction between apalutamide anticancer drug and thymine by DFT method. Chin. J. Struct .Chem. 2019;38:1645–1663. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shahab S., Sheikhi M., Filippovich Li., Dikusar E., Yahyaei H., Kumar R., Khaleghian M. Design of geometry, synthesis, spectroscopic (FT-IR, UV/Vis, excited state, polarization) and anisotropy (thermal conductivity and electrical) properties of new synthesized derivatives of (E,E)-azomethines in colored stretched poly (vinyl alcohol) matrix. J. Mol. Struct. 2018;1157:536–550. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weinhold F., Landis C.R. Neutral bond orbitals and extensions of localized. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. Eur. 2001;2:91–104. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ataünal Ancın N., Gül Oztas S., Küçükterzi O., Altuntas Oztas N. Theoretical investigation of N-trans-cinnamylidene-m-toluidine by DFT method and molecular docking studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2019;1198 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.