Abstract

Patient: Male, 24-year-old

Final Diagnosis: Acute kidney injury • coagulopathy • liver failure • SARS-CoV-2

Symptoms: Cough • fever

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Gastroenterology and Hepatology • Infectious Diseases

Objective:

Unusual clinical course

Background:

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a newly emerging disease that is still not fully characterized. It is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), a novel virus that can be transmitted easily from human to human mainly by the respiratory route. Currently, there is no specific treatment for COVID-19 or a vaccine for prevention. The disease has various degrees of severity. It often presents with non-specific symptoms such as fever, headache, and fatigue, accompanied by respiratory symptoms (e.g., cough and dyspnea) and other systemic involvement. Severe disease is associated with hemophagocytic syndrome and cytokine storm due to altered immune response. Patients with severe disease are more likely to have increased liver enzymes. The disease can affect the liver through various mechanisms.

Case Report:

We report an unusual case of SARS-CoV-2 infection in a 24-year-old man with no previous medical illness, who presented with mild respiratory involvement. He had no serious lung injury during the disease course. However, he experienced acute fulminant hepatitis B infection and cytokine release syndrome that led to multiorgan failure and death.

Conclusions:

It is uncommon for SARS-CoV-2 infection with mild respiratory symptoms to result in severe systemic disease and organ failure. We report an unusual case of acute hepatitis B infection with concomitant SARS-CoV-2 leading to fulminant hepatitis, multiorgan failure, and death.

MeSH Keywords: COVID-19; Hepatitis; Hepatitis B; Liver Failure, Acute

Background

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection has been a central health concern worldwide for the last 6 months. During that time, it has caused more than 484,249 deaths [1]. It was first reported as a novel corona-virus causing a cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan city in China at the end of 2019. The virus causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which ranges in severity from mild asymptomatic to fatal disease due to severe acute respiratory distress syndrome and respiratory failure [2]. It typically presents with symptoms of fever and upper respiratory symptoms. Nonrespiratory symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection include gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, which have occurred in 17.6% of cases [3]. Most patients recover with supportive care only, without the use of specific medications [4]. SARS-CoV-2 infection can occur at any age, but the disease is uncommon in young people, with only 0.9% of patients being younger than 15 years [5]. Hospital admission is more common in the elderly population and mortality is high among older patients and patients with comorbidities [6]. Investigations on the disease pathogenesis and its effects in different populations are ongoing. We present a case in which a young man with no significant past medical history presented with SARS-CoV-2 infection symptoms. He developed fulminant hepatitis B infection and multiorgan failure that led to his death. In severe cases, COVID-19 is associated with cytokine release syndrome and fatality is high.

Case Report

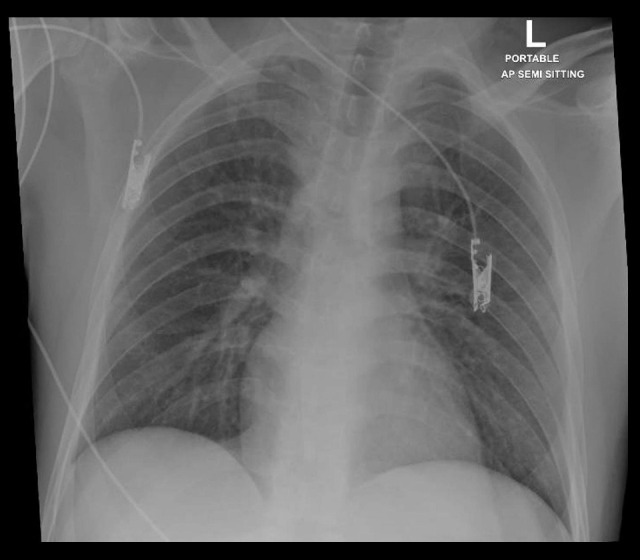

A 24-year-old Nepalese male with no previous medical history was brought by ambulance to the Emergency Department. He reported experiencing fever, cough, and fatigue for the past 3 days. On examination, he weighed 60 kg (height, 170 cm), and he appeared tired and was disoriented to place and time. Blood was observed in the nasopharynx, but he had no oral injury (e.g., tongue bite). No urinary or bowel incontinence and no neck stiffness was present. The patient vomited around 500 mL of coffee ground emesis (hematemesis). He was maintaining 99% oxygen saturation on room air, his blood pressure was 126/84 mmHg, and his temperature was 39.4°C. His level of consciousness deteriorated rapidly, and he was intubated to maintain the airway. A portable chest X-ray revealed normal lung parenchyma (Figure 1). Initial blood work showed severe deranged liver function.

Figure 1.

Anteroposterior chest X-ray showing normal lung parenchyma without signs of acute respiratory distress syndrome.

A nasopharyngeal/throat swab was tested using fully automated reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) Cobas® 6800 (Roche), and the result was positive for SARSCoV-2. The patient was classified as having severe disease according to the World Health Organization case definition [7].

He was started on SARS-CoV-2 treatment for severe disease per Infectious Disease Department protocol for patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection confirmed by PCR (chloroquine, azithromycin, oseltamivir, tocilizumab). For liver support, the patient received acetylcysteine infusion, lactulose, vitamin K (phytonadione 10 mg), rifaximin, and intravenous pantoprazole. He was also given 4-factor prothrombin complex concentrate (4F-PCC), fresh frozen plasma, and fibrinogen for coagulopathy, and he was started on sustained low-efficiency dialysis for acute kidney injury. Work-up for the underlying liver injury showed no other causes (Table 1). Computed tomography of the Head showed no evidence of intra- or extra-axial intracranial hemorrhage. Normal attenuation of brain parenchyma and no hydrocephalus were noted. No midline shift or mass effect was present, and posterior fossa structures were grossly unremarkable. Abdominal ultrasound showed the liver was normal in size, measuring 11 cm, with coarse parenchymal echotexture with no obvious foci, measuring 11 mm and patent. The common bile duct proximal part was normal in diameter, measuring 3 mm. The spleen was normal in size, measuring 10.7 cm, with homogeneous echotexture and no focal lesions. Both kidneys were normal in size, with no calculus or hydronephrosis.

Table 1.

Shows the lab investigation done for the patients, including toxicology screen, liver function, hepatitis serology, and inflammatory markers.

| Lab result | Normal range | |

|---|---|---|

| Blood group | O positive | |

| WBC | 10×103/uL | 4–10×103/uL |

| Absolute neutrophil count | 7.0×103/uL | |

| Eosinophil count | 0.0×103/uL | 0–0.5 |

| Lymphocyte | Count 1.7×103/uL | 1–3×103/uL |

| Hemoglobin | 13.9 gm/dL | 13–17 gm/dL |

| Platelets | 64×103/uL | 150–400 103/uL |

| Creatinine | 305 | 62–106 umol/L |

| urea | 8.7 umol/L | 2.8–8.1 umol/L |

| PH | 7.14 | 7.350–7.450 |

| HCO3 | 7 mmol/L | 22–29 mmol/L |

| Glucose | 3.2 mmol/L | 3.3–5.5 mmol/L |

| Lactate | 22.8 mmol/L | 0.5–2.2 mmol/L |

| ALT | >7000 U/L | 0–41 U/L |

| AST | >7000 U/L | 0–40 U/L |

| INR | 9.8 | Critical high >4.9 |

| Prothrombin time | 84.9 | 7.9–11.8 |

| bilirubin | 115 umol/L | 0–21 umol/L |

| Albumin | 37 gm/L | 35–53 gm/L |

| LDH | 1,134 U/L | 135–225 U/L |

| Ammonia | 268 umol/L | 16–60 umol/L |

| D-dimer | 11.51 mg/L FEU | 0–0.44 mg/L FEU |

| Fibrinogen | 0.8 gm/L | 2–4.1 gm/L |

| Cholesterol | 0.7 mmol/L | Normal: <1.7 mmol/L |

| TAG | 0.7 mmol/L | Normal: <1.7 mmol/L |

| Acetaminophen level | 193 umol/L | Therapeutic Range: 66–199 umol/L |

| Ethanol level | <2.2 mmol/L | Critical: >44.9 mmol/L |

| Salicylate | <0.3 mg/dL | Therapeutic range: 15–30 mg/dL for Anti-inflammatory/Rheumatic condition, Toxic: >30 mg/dL, Lethal: >60 |

| CRP | 67.4 mg/L | 0–5 mg/L |

| Ferritin | 20,573.0 ug/L | 38–270 ug/L |

| Procalcitonin | 4.89 ng/mL | >2.0 ng/mL represents a high risk of sever sepsis and/or septic shock ng/mL |

| Blood culures | Negative | |

| HIV Ag/Ab combo | Negative | |

| Hepatitis C Ab | Negative | |

| Hepatitis c PCR | Negative | |

| Hepatitis A total Ab | Negative | |

| Hepatitis B S Ag | Positive | |

| Hepatitis B S Ag Ab | <2.00 | Antibody titers of ≥10 mIU/ml post HBV vaccination confirms successful |

| Hepatitis B S Ag | Positive | |

| Hepatitis B PCR | >170,000,000 IU/mL | |

| Hepatitis B core Ab IgM | Positive | |

| Hepatitis B e Ag | Positive | |

| Hepatitis B e Ab | Negative | |

| Hepatitis D Ab | Negative |

The patient’s body temperature was high on admission (39.4°C), but later it was fluctuating between 31.8°C and 39°C and occasionally dropping to 24.4°C. His ventilatory settings were continuous mandatory ventilation, positive end expiratory pressure at 5 cm of H2O, and inspired oxygen fraction at 25%, with oxygen saturation at 99–100% most of the time. Repeat RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2 after 7 days was still positive. The patient developed disseminated intravascular coagulation and bleeding from the intravenous site and endotracheal tube. The patient remained in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and died on the 10th day of admission due to multiorgan failure, acute liver failure, acute renal failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Discussion

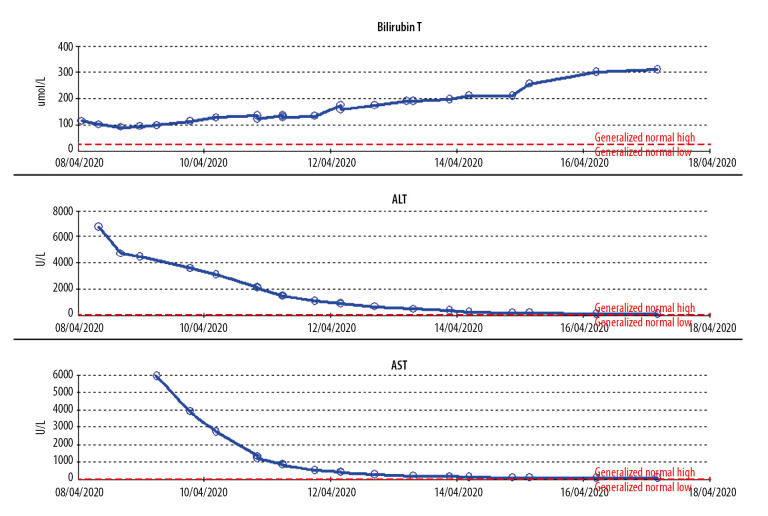

Our patient had a rapid deterioration in consciousness and no detailed information was obtained from him. He presented to the Emergency Department with typical symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection, including fever, fatigue, and dry cough, which are the 3 most common symptoms of COVID-19 (fever, 98.6%; fatigue, 69.6%; dry cough, 57%) [2]. His respiratory symptoms were mild, however, and respiratory function was stable. He was maintaining good saturation on room air, and his chest X-ray (Figure 1) was unremarkable, with no signs of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Even after intubation, he was on a low ventilatory setting, with low positive end-expiratory pressure and inspired oxygen fraction, and the criteria for ARDS were not met. The main affected system was the liver, with liver enzymes measured at more than 7000 U/L (Figure 2). The patient also had acute kidney injury requiring hemodialysis, with coagulopathy and features of disseminated intravascular coagulation (high international normalized ratio, low platelets, low fibrinogen, and high d-dimer).

Figure 2.

Trends for liver enzymes (ALT, AST) and total bilirubin during the hospital course. ALT – alanine transferase; AST – aspartate transferase.

The hepatitis B profile suggested early acute hepatitis B infection (Table 1) [8]. Ultrasound of the abdomen did not show features of chronic liver disease. The patient’s model for end-stage liver disease score was 51 (before starting dialysis). Although it is uncommon for COVID-19 to present mainly as hepatitis, 1 case has been reported [9]. It is uncommon for acute hepatitis B viral infection to coincide with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

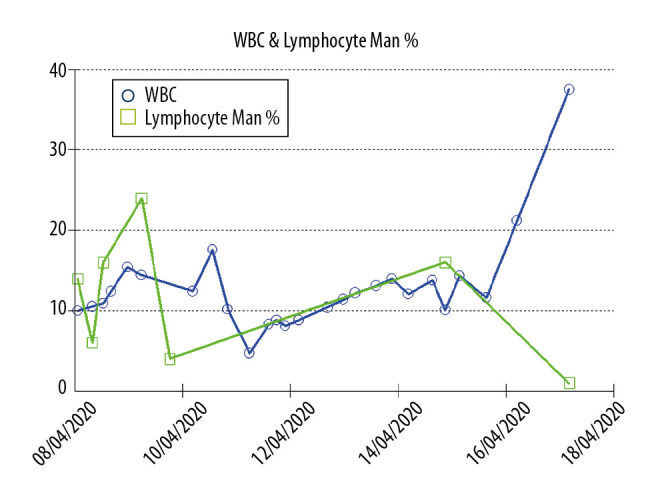

Increased levels of liver enzymes (e.g., aspartate transferase) during SARS-CoV-2 infection is common. It is seen in 18.2% of patients with nonsevere disease, and up to 39.4% of patients with severe disease [10]. Liver injury was more common among ICU-admitted patients, reaching up to 62% compared with 25% of patients not requiring ICU admission [10]. In most cases, liver injury is transient and requires no action. However, for severe liver injury, there are no clear guidelines, and management is based on an individualized approach [10]. The mechanism of liver injury in patients with COVID-19 could be due to SARS-CoV-2 infecting liver cells directly [10]. It is less likely that hypoxia due to ARDS and the positive pressure ventilation lead to hepatic congestion [11]. Additionally, the worsening of underlying liver disease during the infection or by drug hepatotoxicity may play a role [11]. Another explanation is that the increased liver enzymes are not released from hepatocytes but from other sites, similar to myositis in severe influenza, which is supported by elevated levels of creatinine kinase, lactate dehydrogenase, and myoglobin [11]. Similar to other respiratory viruses, SARS-CoV-2 might lead to hepatic damage from an altered immune response involving cytotoxic T cells and Kupffer cells [12]. This mechanism is the most likely explanation for the severe fulminant hepatitis seen in this patient, which led to an extremely high hepatitis B viral count (>17 million). Moreover, cytokine storms with associated altered immune response can aid in the activation of viral hepatitis, as seen with severe hepatitis B flares that occur during immunosuppression and chemotherapy treatment of lymphoma [13] or in treatment with disease-modifying anti-rheumatoid drugs [14]. Severe COVID-19 is also reported to have marked activation of coagulative and fibrinolytic system and a relatively lower platelet count [2] and higher ratio of neutrophil count to lymphocyte count. In our patient, the white blood cell count was rising but the ratio of lymphocytes to white blood cells was not constant and became inverse at the end of the disease course, as demonstrated in Figure 3. The patient had an H score of 172 (no organomegaly, temperature of 39.4°C, ferritin more than 6000 ng/mL, fibrinogen 0.8 g/L, 2 types of cytopenia [thrombocytopenia and anemia], triglycerides less than 1.5 mmol, and high aspartate transferase), with a 54% to 70% risk of hemophagocytic syndrome [15]. These findings were associated with COVID-19-induced cytokine storm and immunosuppression, which precipitated the flare of severe hepatitis B infection [16]. Similarly, patients with chronic liver disease, including patients with chronic hepatitis B infection co-occurring with SARS-CoV-2 infection, had more severe illness and poor outcomes [17]. These findings support that SARS-CoV-2 influences the immune response and aggravates hepatitis B viral replication during both acute and chronic phases of hepatitis B infection [17].

Figure 3.

Trends for white blood cells (WBCs) and lymphocytes (manual count) throughout the hospital course, with the lymphocyte percentage decreasing and WBCs increasing at the end of the disease course.

Our patient initially had a fever reaching up to 39.4°C during his hospital stay, although it fluctuating up and down and at times dropped to 24.4°C. In patients admitted to intensive care, this pattern may indicate poor neurological outcome, which was observed in patients admitted to ICU with brain injury [18] and after cardiac arrest [19]. It may also indicate a severe cerebral injury.

Conclusions

Patients with COVID-19 without severe respiratory involvement are at risk of immune-mediated activation of hepatitis B and fulminant hepatitis. Severe spontaneous hypothermia in the context of SARS-CoV-2 infection may be associated with poor outcome. Inverse neutrophil to lymphocyte count ratio could be used to monitor and predict the outcome.

Acknowledgments

All authors wish to express gratitude to the Internal Medicine Residency Program, Dr. Ahmed Ali Almohammed, and Dr. Dabia Hamad Almohanadi for the scientific support.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

References:

- 1.Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Situation Reports 2020. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports/

- 2.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061–69. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheung KS, Hung IFN, Chan PPY, et al. Gastrointestinal manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection and virus load in fecal samples from a Hong Kong cohort: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(1):81–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.03.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Food and Drug Administration . FDA cautions against use of hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine for COVID-19 outside of the hospital setting or a clinical trial due to risk of heart rhythm problems. FDA; 2020. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-cautions-against-usehydroxychloroquine-or-chloroquine-covid-19-outside-hospital-setting-or. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052–59. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization . Clinical management of COVID-19: Interim guidance. Geneva: WHO; 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/clinical-management-of-covid-19. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Terrault NA, Lok ASF, McMahon BJ, et al. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 Hepatitis B Guidance. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken) 2018;12(1):33–34. doi: 10.1002/cld.728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wander P, Epstein M, Bernstein D. COVID-19 presenting as acute hepatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(6):941–42. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang C, Shi L, Wang FS. Liver injury in COVID-19: Management and challenges. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(5):428–30. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30057-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bangash MN, Patel J, Parekh D. COVID-19 and the liver: Little cause for concern. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(6):529–30. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30084-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adams DH, Hubscher SG. Systemic viral infections and collateral damage in the liver. Am J Pathol. 2006;168(4):1057–59. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu C, Tsou HH, Lin SJ, et al. Chemotherapy-induced hepatitis B reactivation in lymphoma patients with resolved HBV infection: A prospective study. Hepatology. 2014;59(6):2092–100. doi: 10.1002/hep.26718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee YH, Bae SC, Song GG. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in HBsAg-positive patients with rheumatic diseases undergoing anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy or DMARDs. Int J Rheum Dis. 2013;16(5):527–31. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.12154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fardet L, Galicier L, Lambotte O, et al. Development and validation of the HScore, a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(9):2613–20. doi: 10.1002/art.38690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, et al. COVID-19: Consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1033–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zou X, Fang M, Li S, et al. Characteristics of liver function in patients with SARS-CoV-2 and chronic HBV co-infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.06.017. [Online ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rincon F, Hunter K, Schorr C, et al. The epidemiology of spontaneous fever and hypothermia on admission of brain injury patients to intensive care units: A multicenter cohort study. J Neurosurg. 2014;121(4):950–60. doi: 10.3171/2014.7.JNS132470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.den Hartog AW, de Pont AC, Robillard LB, et al. Spontaneous hypothermia on intensive care unit admission is a predictor of unfavorable neurological outcome in patients after resuscitation: an observational cohort study. Crit Care. 2010;14(3):R121. doi: 10.1186/cc9077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]