Abstract

Northern Italy has been the first European area affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and related social restrictive measures. We sought to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on PICU admissions in Northern Italy, using data from the Italian Network of Pediatric Intensive Care Units Registry. We included all patients admitted to 4 PICUs from 8-weeks-before to 8-weeks-after February 24th, 2020, and those admitted in the same period in 2019. Incidence rate ratios (IRR) evaluating incidence rate differences between pre- and post-COVID-19 periods in 2020 (IRR-1), as well as between the post-COVID-19-period with the same period in 2019 (IRR-2), were computed using zero-inflated negative binomial or Poisson regression modeling. A total of 1001 admissions were included. The number of PICU admissions significantly decreased during the COVID-19 outbreak compared to pre-COVID-19 and compared to the same period in 2020 (IRR-1 0.63 [95%CI 0.50–0.79]; IRR-2 0.70 [CI 0.57–0.91]). Unplanned and medical admissions significantly decreased (IRR-1 0.60 [CI 0.46–0.70]; IRR-2 0.67 [CI 0.51–0.89]; and IRR-1 0.52, [CI 0.40–0.67]; IRR-2 0.77 [CI 0.58–1.00], respectively). Intra-hospital, planned (potentially delayed by at least 12 h), and surgical admissions did not significantly change. Patients admitted for respiratory failure significantly decreased (IRR-1 0.55 [CI 0.37–0.77]; IRR-2 0.48 [CI 0.33–0.69]).

Conclusions: Unplanned and medical PICU admissions significantly decreased during COVID-19 outbreak, especially those for respiratory failure.

|

What is Known: • Northern Italy has been the first European area affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. • Although children are relatively spared from the severe COVID-19 disease, the pediatric care system has been affected by social restrictive measures, with a reported 73–88% reduction in pediatric emergency department admissions. | |

|

What is New: • Unplanned and medical PICU admissions significantly decreased during the COVID-19 outbreak compared to pre-COVID-19 and to the same period in 2019, especially those for respiratory failure. Further studies are needed to identify associated factors and new prevention strategies. |

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00431-020-03832-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Pediatric critical care, Intensive care, Pandemic, COVID-19, Public health, Pediatrics, Children

Introduction

Northern Italy has been the first European area in which the COVID-19 pandemic has spread. Although the number of pediatric patients affected by COVID-19 and the severity of symptoms is limited compared to adults [1–4], undirected changes affecting the pediatric care system have been described since the beginning of the outbreak. A recent study reported a 73–88% reduction in pediatric emergency department admissions after the implementation of lockdown measures, compared to the same period in 2018–2019 [5]. Variations in rates and types of admission to the pediatric intensive care units (PICUs) in this period have not yet been investigated. Here, we sought to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown measures on rates and types of PICU admissions in Northern Italy. To adequately contextualize this analysis, we also evaluated the overall pediatric mortality rate in the same periods and geographic area.

Material and methods

Data source and ethics approval

PICU admission data were extracted from the Italian Network of Pediatric Intensive Care Units (TIPNet) Registry. TIPNet is a Research Network involving 18 Italian PICUs. Ethics Committees of each Center approved the use of the Registry for no-profit research purposes, with a waiver for informed consent due to the observational nature and anonymity of data. Data are prospectively inserted each day of PICU stay into an electronic standardized sheet (REDCap-platform, REDCap, TN, USA). Data are anonymized at the moment of data extraction. Finally, overall mortality data were extracted from the Italian National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT) public repository. All investigations were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study population and data collection

We included all patients admitted to 4 PICUs in Northern Italy (Padova, Verona, Milano, Alessandria) in the period included between 8-weeks-before and 8-weeks-after the first administrative lockdown decree (24th February 2020) [6], and patients admitted in the same period in 2019. All patients admitted to the PICUs were registered. All centers maintained their role of reference for PICU admissions during the COVID-19 outbreak, and no transfer to other centers was registered. Children’s Hospital Vittore Buzzi admitted also adult patients during the outbreak, but pediatric admissions were never readdressed to other centers. The following variables were extracted: age, gender, center of admission, date of admission, type of admission (medical/surgical/traumas, planned/unplanned, intra-hospital/extra-hospital), diagnosis of admission, Pediatric Index of Mortality Score 3 (PIM3) [7], presence of comorbidities, and diagnosis at discharge. Planned admissions were defined as admissions that may be delayed by at least 12 h.

For the overall mortality rate analysis, we included all data on residence and mortality regarding the same municipalities involved in the PICU admission analysis.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data were reported in terms of absolute frequencies for categorical variables, and in terms of medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables. Age and PIM3 values were compared between the 2019 and 2020 cohorts using the Wilcoxon-rank sum test. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) evaluating incidence rate differences between pre- and post-COVID-19 periods in 2020 (IRR-1), as well as between the post-COVID-19-period with the same period in 2019 (IRR-2), and their 95% confidence intervals were computed using zero-inflated negative binomial or Poisson modeling according to the data distribution, with tuning parameters estimated from data [8, 9]. The zero-inflated method was preferred to account for both possible inflation of categories with no observation and overdispersion in counts data. Nighty-five percent confidence intervals (CIs) were computed using a bootstrapping technique. Finally, the daily mortality rates of the 16-week period in 2019 and of the same period in 2020 were computed as ratios between the daily number of deaths and the population at risk in the same areas. The IRR and 95% CI evaluating the difference in mortality rates between 2019 and 2020 was then computed using a Poisson regression modeling. All statistical analyses were performed using the R statistics statistical software (version 3.6.2., R Core Team, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Statistical significance was set at a two-sided p value < 0.05.

Results

Study population

Overall, 1001 patients were included. Over the course of the 2020 16-week period, a total of 443 patients were admitted to the 4 PICUs (9 [2%] affected by COVID-19). In the same period in 2019, 558 patients were admitted to the same centers. The median age was 0.9 years in the 2019 cohort (interquartile range [IQR] 0.1–5.0), and 1.2 years (IQR 0.2–5.9) in the 2020 cohort (p = 0.103). The PIM3 score was similar in the two cohorts (0.009 [IQR 0.004–0.032] vs 0.008 [IQR 0.005, 0.035], p = 0.94).

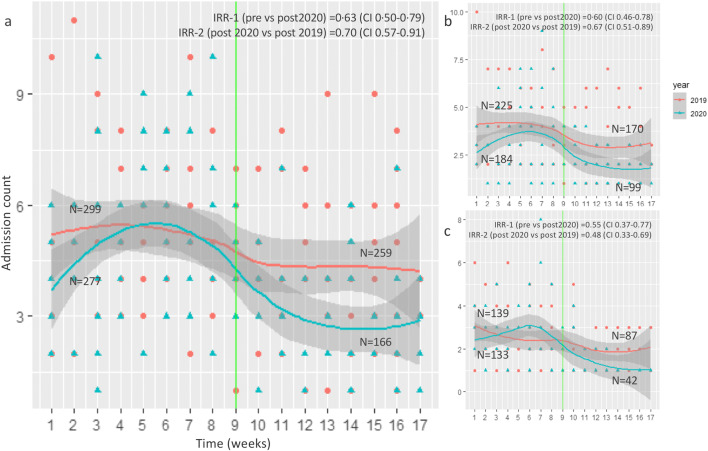

Frequency of PICU admissions and incidence rate ratios

Characteristics, frequencies of PICU admissions, and estimated IRRs are shown in Table 1. Overall, the number of PICU admissions significantly decreased by 37% compared to pre-COVID-19 (IRR-1 0.63 [CI 0.50–0.79]) and by 30% compared to 2019 (IRR-2 0.70 [CI 0.57–0.91]) (Fig. 1). PICU admissions decreased especially among patients < 1 year (IRR-1 0.64 [CI 0.47–0.91]), but this is not significant when compared to 2019. Unplanned admissions decreased by 40% compared to pre-COVID-19 (IRR-1 0.60 [CI 0.46–0.70]) and by 37% compared to 2019 (IRR-2 0.67 [CI 0.51–0.89]). Medical admissions decreased by 50% compared to pre-COVID-19 (IRR-1 0.52, [CI 0.40–0.67]) and by 23% compared to 2019 (IRR-2 0.77 [CI 0.58–1.00]. Extra-hospital admissions decreased by 50% compared to pre-COVID-19 (IRR-1 0.50 [CI 0.37–0.65]) and by 30% compared to 2019 (IRR-1 0.70 [CI 0.52–0.97]). Intra-hospital, planned, and surgical admissions did not significantly change. Patients admitted for respiratory failures decreased by 45% compared to pre-COVID-19 (IRR-1 0.55 [CI 0.37–0.77]) and by 52% compared to 2019 (IRR-2 0.48 [CI 0.33–0.69]). Other admission or discharge diagnoses did not significantly differ. Patients with comorbid conditions were admitted significantly less frequently during COVID-19 outbreak compared to the pre-COVID-19 period (IRR 0.73 [0.56–0.96]), but did not significantly differ from 2019.

Table 1.

Characteristics and frequency of admissions to pediatric intensive care units, and estimates of incidence rate ratios (IRR)

| Variable | IRR-1 (pre- vs post 2020) | 95% confidence interval | IRR-2 (post 2019 vs post 2020) | 95% confidence interval | 2019 | 2020 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N, pre-Feb 24 | N, post-Feb 24 | N, tot 2019 | N, pre-Feb 24 | N, post-Feb 24 | N, tot 2020 | |||||

| Admissions, overall | 0.63 | 0.50–0.79 | 0.70 | 0.57–0.91 | 299 | 259 | 558 | 277 | 166 | 443 |

| Gender | ||||||||||

|

Female Male |

0.71 0.69 |

0.52–0.98 0.53–0.90 |

0.79 0.83 |

0.57–1.08 0.63–1.11 |

134 165 |

110 149 |

244 314 |

115 162 |

62 104 |

177 266 |

| Age | ||||||||||

|

0–1 year 1–3 years 3–6 years > 6 years |

0.65 0.71 0.97 0.80 |

0.47–0.91 0.41–1.17 0.55–1.65 0.54–1.18 |

0.90 0.80 0.86 0.80 |

0.64–1.24 0.47–1.31 0.51–1.43 0.55–1.15 |

145 50 29 61 |

94 45 43 70 |

239 95 72 131 |

139 46 24 58 |

65 24 22 42 |

204 70 46 100 |

| Type of admission | ||||||||||

|

Extra-hospital Intra-hospital, ward Intra-hospital, surgery |

0.50 0.80 1.02 |

0.37–0.65 0.52–1.21 0.69–1.62 |

0.70 1.01 0.85 |

0.52–0.97 0.66–1.57 0.60–1.24 |

190 49 49 |

130 44 72 |

320 93 121 |

175 49 45 |

77 31 49 |

252 80 94 |

|

Planned Unplanned |

0.86 0.60 |

0.55–1.32 0.46–0.78 |

0.93 0.67 |

0.60–1.36 0.51–0.89 |

56 225 |

73 170 |

129 395 |

75 184 |

45 99 |

120 283 |

| Diagnosis at admission | ||||||||||

|

Medical Respiratory failure Sensory impairment/seizure Metabolic/dehydration Cardiovascular, congenital Heart failure Sepsis Others Surgical Traumas |

0.52 0.55 0.70 1.25 1.00b 0.57 1.00b 0.89 0.86 1.00b |

0.40–0.67 0.37–0.77 0.30–1.50 0.28–4.67 0.37–2.72 0.21–2.21 0.26–3.31 0.48–1.67 0.63–1.24 0.11 – c |

0.77 0.48 0.94 0.71 -d 1.13 1.00b 0.83 0.87 0.79 |

0.58–1.00 0.33–0.69 0.43–2.08 0.14–4.03 - 0.52–3.42 0.24–4.91 0.41–1.63 0.62–1.23 0.26–2.08 |

213 139 28 7 1 7 2 21 56 12 |

147 87 18 11 1 6 6 15 83 15 |

360 226 46 18 2 13 8 36 139 27 |

206 133 20 8 9 6 7 15 68 2 |

98 42 9 5 6 17 4 13 62 6 |

304 175 29 13 15 23 11 28 130 8 |

| Patient complexity | ||||||||||

|

Baseline comorbid conditions No comorbid conditions |

0.73 0.62 |

0.56–0.96 0.43–0.84 |

1.03 0.69 |

0.79–1.39 0.50–0.95 |

87 195 |

93 151 |

180 346 |

128 148 |

90 76 |

218 224 |

| Diagnosis at dischargea | ||||||||||

|

Respiratory, upper tract Respiratory, lower tract Respiratory, other Cardiovascular, congenital Cardiovascular, acquired Neurologic Gastrointestinal Others |

1.23 0.54 0.94 0.90 0.83 0.79 1.14 0.82 |

0.46–3.03 0.30–0.94 0.55–1.64 0.54–1.68 0.31–2.53 0.47–1.33 0.53–2.88 0.52–1.27 |

1.20 0.78 0.64 1.09 1.23 0.89 0.97 0.53 |

0.35–6.66 0.43–1.53 0.35–1.02 0.61–1.93 0.42–5.67 0.52–1.46 0.48–2.13 0.35–0.86 |

7 83 47 18 9 37 10 73 |

5 29 55 17 3 33 13 83 |

12 112 102 35 12 70 23 156 |

11 82 32 27 6 33 7 52 |

6 14 20 22 16 23 16 29 |

17 96 52 49 22 56 23 81 |

Incidence rate ratios are IRR-1, pre-COVID-19 incidence rate vs post-COVID-19 incidence rate in 2020; IRR-2, post-COVID-19 incidence rate in 2019 vs the incidence rate of the same period in 2020. a37 patients were still in the PICU at the moment of data analysis; thus, no diagnosis at discharge was entered. bIRR computed using zero-inflated Poisson regression modeling due to different data distribution. cInfinite upper bounds. dIRR and CI were not reliable due to the small numerosity of the subgroup. Missing data: n (2019, 2020): age: 44 (21, 23); type of admission extra/-hospital/intra-hospital/surgery: 41 (24, 17); planned/not planned: 74 (34, 40); diagnosis at admission: 32 (31, 1); comorbid conditions: 33 (32, 1); diagnosis at discharge 4 (4, 0). IRR, incidence rate ratio

Fig. 1.

a Overall trend of admissions to pediatric intensive care units in 2020 and 2019; b Trend of unplanned admissions; c Trend of admissions of patients with respiratory failure. Data refer to the period included from 8-weeks-before to 8-weeks-after the first administrative lockdown decree (24th February, green line). Lines represent the incidence rate and 95% confidence interval (dark gray area) modeling over time. Incidence rates and incidence rate ratios evaluating incidence rate differences between pre- and post-COVID-19 periods in 2020 (IRR-1), as well as between the post-COVID-19-period with the same period in 2019 (IRR-2), were computed using zero-inflated negative binomial or Poisson regression modeling, and bootstrapping process for CIs. N is the total count per subgroup

Overall mortality rate analysis

The overall pediatric mortality rate computed for the same geographic area in the 2020 16-week study period did not significantly differ from 2019 (IRR 1.23 [CI 0.60–2.53], Supplemental Figure 1).

Discussion

With this study, we have shown that unplanned and medical PICU admissions significantly decreased during the COVID-19 outbreak compared to pre-COVID-19 and to 2019. Particularly, PICU admissions for respiratory failure significantly decreased compared to pre-COVID-19 and to 2019.

A decrease in PICU admissions could have been theoretically expected due to the reorganization of elective-care within medical and surgical departments. However, our findings showed that planned admissions did not significantly change. This can be explained by the fact that “planned” PICU activity cannot be considered as a direct synonym of “elective,” since often involves critically patients whose admission can be delayed only by few hours or days (e.g., patients needed monitoring during infusions or procedures, vascular lines placements, etc.). Additionally, even if a large number of surgeries were postponed during the COVID-19-outbreak worldwide, it is also true that urgent interventions were not delayed, and those interventions usually represent the most significant determinant in the number of surgical PICU admissions.

Conversely, we found that unplanned medical admissions significantly decreased. Prevention of PICU admissions—i.e., reducing the number of patients who present with critical and life-threatening conditions—has been one of the main goals of the pediatric modern medicine. Here, we are looking at an event that has spontaneously reduced the PICU admissions by 30–50%. Although we do not have a clear scientific explanation of this phenomenon, we believe this represents an important message to the scientific community and Health Systems. We may speculate that the implementation of lockdown measures [6], social distancing, mask-wearing, travel restriction, and the consolidation of the hygiene practices might have reduced the transmission of other respiratory pathogens. Certainly, the human being cannot live under restrictive measures forever, but if restrictive measures were able to significantly reduce the rate of PICU admissions, it is worthy to analyze which measures can be reproduced within a healthy and constructive approach, e.g., reorganization of day cares or increasing the awareness on the importance to isolate symptomatic subjects.

An additional finding of our analysis was that the trend of admissions of comorbid patients significantly decreased during the outbreak, although it is not significantly different from 2019. Since comorbid patients are at higher risk of both PICU admission and COVID-19 disease, we could hypothesize that an effective strategy of domiciliary care might have been implemented during the outbreak for these patients. It is also possible that comorbid patients refrained from seeking specialized care during the outbreak. However, a spontaneous resolution of a moderate disease in comorbid patients would be extremely rare, and the overall mortality rate did not significantly differ from 2019.

Some limitations should be taken into consideration when interpreting these results. Although data were prospectively collected and all admitted patients were included in the registry, this remains a retrospective analysis and a small amount of data was missing. Additionally, no data regarding specific respiratory pathogens (other than COVID-19) were included. Finally, it was not possible to stratify the severity of comorbid conditions.

In conclusion, our study showed that unplanned and medical PICU admissions, especially those for respiratory failure, significantly decreased during COVID-19-outbreak. Further studies are needed to address the complex reasons underlying these significant changes, but we believe this report can guide and help physicians and health systems in being aware of the complex adjustments of events around a pandemic and identifying new strategies of prevention.

Electronic supplementary material

Trend of mortality rate in the pediatric population of the same geographic area in the same 2019 and 2020 periods. Data refer to the period included from 8-weeks-before to 8-weeks-after the first administrative lockdown decree (24th February, blue vertical line). Lines represent the incidence rate and 95% confidence interval (dark gray area) modeling over time. Incidence rates and incidence rate ratios and their 95% confidence intervals were computed using Poisson regression modeling, and bootstrapping process for CIs. (DOCX 36 kb)

Acknowledgments

We thank all Researchers involved in the TIPNet Research Group for the work they have done for implementing and constantly improving the TIPNet Registry. We thank all the Participating Centers and their PICU personnel for the data collection.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- CI

Confidence interval

- IQR

Interquartile ranges

- IRR

Incidence rate ratio

- PICU

Pediatric Intensive Care Unit

- PIM3

Pediatric Index of Mortality Score 3

- TIPNet

Italian Network of Pediatric Intensive Care Units

Authors’ Contributions

Dr. Sperotto, Dr. Amigoni, Dr. Gregori, Dr. Ocagli, and Dr. Comoretto had full access to all data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Dr. Sperotto, Dr. Wolfler, Dr. Gregori, and Dr. Amigoni had a major role in the study design, interpretation of data, and drafting of the manuscript. Dr. Gregori, Dr. Ocagli, Dr. Comoretto, and Dr. Sperotto performed the statistical analysis. All authors performed a critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical statement

Ethics Committees of each Center approved the use of the Registry within the Network for no-profit research purposes, with a waiver for informed consent due to the observational nature of the project and anonymity of data.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Francesca Sperotto and Andrea Wolfler contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Francesca Sperotto, Email: francesca.sperotto@cardio.chboston.org.

Andrea Wolfler, Email: andrea.wolfler@asst-fbf-sacco.it.

Paolo Biban, Email: paolo.biban@aovr.veneto.it.

Luigi Montagnini, Email: luigi.montagnini@gmail.com.

Honoria Ocagli, Email: honoria.ocagli@studenti.unipd.it.

Rosanna Comoretto, Email: rosanna.comoretto@unipd.it.

Dario Gregori, Email: dario.gregori@unipd.it.

Angela Amigoni, Email: angela.amigoni@aopd.veneto.it.

References

- 1.Garazzino S, Montagnani C, Donà D, et al. Multicentre Italian study of SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and adolescents, preliminary data as at 10 April 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25:1–4. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.18.2000600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parri N, Lenge M, Buonsenso D (2020) Children with Covid-19 in pediatric emergency departments in Italy. N Engl J Med 1-4 [E-pub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y, et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19 among children in China. Pediatrics. 2020;145:1–10. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shekerdemian LS, Mahmood NR, Wolfe KK, et al (2020) Characteristics and outcomes of children with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection admitted to US and Canadian pediatric intensive care units. JAMA Pediatr 1-6 [E-pub ahead of print]. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Lazzerini M, Barbi E, Apicella A, et al. Delayed access or provision of care in Italy resulting from fear of COVID-19. Lancet child Adolesc Heal. 2020;4:e10–e11. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30108-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Italian Prime Minister Administrative Decree, 23th February 2020:Urgent measures of prevention and social restriction regarding Covid-19 outbreak. https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/gu/2020/02/23/45/sg/html

- 7.Straney L, Clements A, Parslow RC, et al. Paediatric index of mortality 3: an updated model for predicting mortality in pediatric intensive care. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14:673–681. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31829760cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yau K, Wang K, Lee A. Zero-inflated negative binomial mixed regression modeling of over-dispersed count data with extra zeros. Biom J. 2003;45:437–452. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200390024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Long JS (1997) Regression models for categorical and limited dependent variables. SAGE Publications

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trend of mortality rate in the pediatric population of the same geographic area in the same 2019 and 2020 periods. Data refer to the period included from 8-weeks-before to 8-weeks-after the first administrative lockdown decree (24th February, blue vertical line). Lines represent the incidence rate and 95% confidence interval (dark gray area) modeling over time. Incidence rates and incidence rate ratios and their 95% confidence intervals were computed using Poisson regression modeling, and bootstrapping process for CIs. (DOCX 36 kb)