Abstract

A cross-sectional serological survey was carried out in two long-term care facilities that experienced COVID-19 outbreaks in order to evaluate current clinical COVID-19 case definitions. Among individuals with a negative or no previous COVID-19 diagnostic test, myalgias, headache, and loss of appetite were associated with serological reactivity. The US CDC probable case definition was also associated with seropositivity. Public health and infection control practitioners should consider these findings for case exclusion in outbreak settings.

Keywords: COVID-19, Public health, Case identification, Case exclusion, Clinical case definition, Serology

Background

Long-term care (LTC) facilities are high-risk settings for transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the causative agent of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Given the high mortality rate associated with COVID-19 among LTC residents,1 timely and evidence-informed interventions are critical for mitigating transmission risk. Serological testing may be useful to evaluate and inform public health infection control practices by uncovering cases missed during an outbreak using current laboratory-based and clinical case definitions.2

Communicable disease case definitions can be utilized in public health for a variety of purposes (ex. surveillance). In the context where diagnostic tests are not rapidly available or have limited sensitivity, symptom-based case definitions are essential. In LTC outbreaks, uncontrolled introduction of infections not identified through testing may perpetuate transmission despite outbreak control measures. Currently, various national probable/epidemiologically-linked (clinical) case definitions largely focus on respiratory symptoms (ie, cough and shortness of breath), with varying inclusion of systemic/generalized symptoms (ie, fever, chills, loss of appetite)(Appendix A). Given LTC residents often present with nonspecific generalized symptoms for other respiratory pathogens,3 potential cases of COVID-19 are likely missed and potentially contribute to propagation within LTC facilities.

Our analysis aims to provide a descriptive overview of a serological survey of LTC residents and staff members following outbreaks at 2 facilities and evaluate clinical case definitions of COVID-19 used in LTC outbreaks against serological results.

Methods

A cross-sectional serological survey of LTC residents and staff members was administered from May 4th to 14th, 2020 at 2 adult LTC facilities located in the Metro Vancouver area, British Columbia. These LTC facilities experienced large outbreaks, in which 107 residents and 59 staff had become COVID-19 cases at the time of serological sample collection. The onset of the outbreaks at the 2 facilities were March 5th (Facility A) and March 17th (Facility B), 2020. Individuals (or their substitute decision maker) working (staff) or living (resident) in the LTC facility during the outbreaks were included after providing informed verbal consent for venous blood specimen collection.

Venous specimens were tested using an orthogonal approach4 with 5 different commercially-available SARS-CoV-2 antibody assays with varying target immunoglobulin and epitopes (Appendix B), in accordance with manufacturers’ recommendations. Each individual was assigned by a medical microbiologist into “reactive”, “nonreactive” or “equivocal” category based on degree of agreement/disagreement of aggregate antibody results from all tests.

All nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) for SARS-CoV-2 performed on nasopharyngeal swab samples testing were carried out in fully accredited clinical laboratories for clinical purposes, following routine best practice guidelines. Specimens were tested utilizing either a fully validated laboratory developed test targeting the E-gene and RdRP gene regions of SARS-CoV-2 (BC Center for Disease Control Public Health Laboratory), a fully validated laboratory developed test targeting the E-gene region of SARS-CoV-2, or a fully validated commercially developed cobas SARS-CoV-25 test targeting the orf-1a/b and E-gene regions of SARS-CoV-2 (St Paul's Hospital).

Clinical information (symptomatic/asymptomatic history, symptoms recorded, medical comorbidities, medications) for each individual was gathered by abstracting data from a standardized case report form (Appendix C), medical charts of LTC residents, and phone interviews. Resident symptoms were documented through a combination of resident report/staff observation and utilization of a standardized symptom checklist(Appendix D). Symptom onset dates were captured using both clinical information and diagnostic test data (Appendix E). Participants were classified as immunocompromised or immunocompetent using provincial criteria (Appendix F). Data on clinical information and diagnostic test results were abstracted from May 22nd to June 5th 2020.

Descriptive statistics of the study population were summarized in R (v.3.6.2) and STATA (v.15). Multivariable logistic regression (adjusting for age, gender, and facility) was used to generate adjusted odd ratio (aOR) estimates of associations between serological results and different individual symptoms, symptom clusters (Appendix A), immunocompromise status (yes vs no) and history of negative NAATs (<3 vs ≥3). Covariate selection accounted for differences between staff and residents (age, gender) and facility characteristics. Individuals for whom we could not access a clinical history were excluded from regression analyses (n = 6).

Research ethics board review was not required, as this study was part of routine public health operations for quality improvement and program evaluation.

Results

Serological testing was offered to all residents and staff in both facilities, with 44% (303/691) consenting to participate (48% staff, 39% residents). A total of 303 LTC residents (n = 127) and staff (n = 176) were included in the study. After excluding 12 individuals with equivocal serological results, 39% (n = 113) were reactive and 61% (n = 178) were nonreactive. Table 1 provides a descriptive epidemiological summary of study participants. The median time between symptom onset and serological collection was 50 days (IQR = 15) for the entire cohort, 52 days (IQR = 9.5) for NAAT positive cases, and 48 days (IQR = 23.5) for no or negative NAAT cases.

Table 1.

Characteristics and epidemiological summary of study participants

| Cohort demographics | Reactive (n = 113) |

Non-reactive (n = 178) |

Overall (n = 291) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residents | Staff | Residents | Staff | Residents | Staff | |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Total cases | 68 | 45 | 54 | 124 | 122 | 169 |

| Facility | ||||||

| Facility A | 31 (46) | 23 (51) | 5 (9) | 48 (39) | 36 (30) | 71 (42) |

| Facility B | 37 (54) | 22 (49) | 49 (91) | 76 (61) | 86 (70) | 98 (58) |

| Age (y) | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 86 (14) | 50 (20) | 86 (14) | 49 (18) | 86 (15) | 49 (18) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 51 (75) | 32 (71) | 33 (61) | 94 (76) | 84 (69) | 126 (75) |

| Male | 17 (25) | 13 (29) | 21 (39) | 30 (24) | 38 (31) | 43 (25) |

| Symptomatic | ||||||

| Symptoms reported | 58 (85) | 37 (82) | 22 (41) | 39 (31) | 80 (66) | 76 (45) |

| No symptoms reported | 10 (15) | 8 (18) | 32 (59) | 85 (69) | 42 (34) | 93 (55) |

| NAAT result | ||||||

| Positive | 50 (74) | 30 (67) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 50 (41) | 30 (18) |

| Negative | 9 (13) | 7 (16) | 51 (94) | 84 (68) | 60 (49) | 91 (54) |

| No Result* | 9 (13) | 8 (18) | 3 (6) | 40 (32) | 12 (10) | 48 (28) |

| Immunocompromised | ||||||

| Yes | 14 (21) | 1 (2) | 7 (13) | 1(1) | 21 (17) | 2 (1) |

Indicates that no specimen was collected to be sent for NAAT.

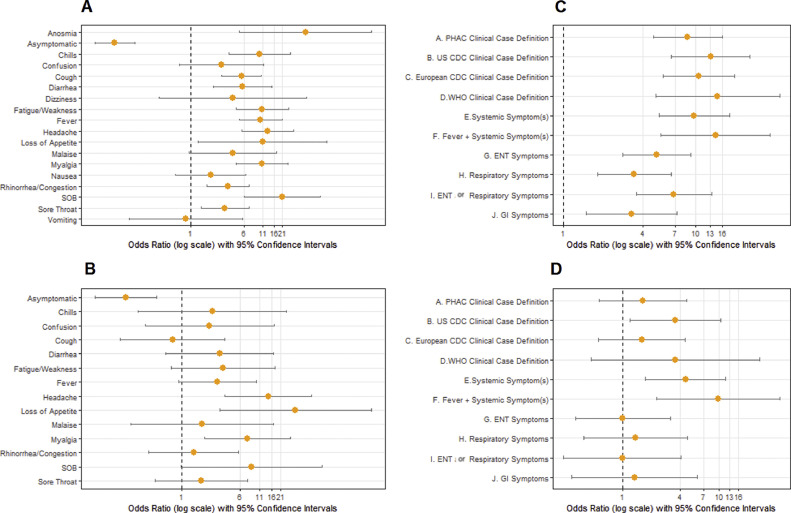

Among the entire study cohort, loss of smell/taste (aOR = 45.98, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 5.12-412.72), shortness of breath (aOR = 21.22, 95%CI: 5.91-76.22), headache (aOR = 13.00, 95%CI:5.47-30.86), loss of appetite (aOR = 10.94, 95%CI:1.27-94.53), fatigue (aOR = 10.90, 95% CI: 4.48-26.48), and myalgia (aOR = 10.80, 95%CI: 4.55-25.60) were most prominently associated with increased odds of reactive serology (Fig 1 A). All symptom cluster case definitions were significantly associated with seropositivity (Fig 1C). Participant immune status was not associated with seropositivity (aOR = 0.29, 95%CI: 0.05-1.66), even among residents only (aOR = 0.83, 95%CI: 0.08-9.07). At last, the absence of recorded symptoms was associated with decreased odds of being seropositive (aOR = 0.08, 95%CI: 0.04-0.15).

Fig 1.

Odds of serological reactivity based on symptoms and symptom clusters. (A and B) Depict (age, gender and facility) adjusted odds ratios (aORs) on a log10 scale for seropositivity of individual symptoms among the entire population (1A) or among individuals with a negative or no NAAT test prior to serological testing (1B). Anosmia, dizziness, nausea, and vomiting are not reported in 1B due to extremely broad confidence intervals. (C and D) Depict aORs (on a log10 scale) for seropositivity of symptom clusters (Appendix A) among the entire population (1C) or among individuals with a negative or no NAAT test prior to serological testing(1D). Anosmia, loss of smell/taste; SOB, shortness of breath/difficulty breathing; PHAC, Public Health Agency of Canada; US CDC, United States Centre for Disease Control; European CDC, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; WHO, World Health Organization.

Among, individuals with a negative or no previous NAAT, only myalgias (aOR = 7.51, 95%CI:2.00-28.25), headache (aOR = 14.27, 95%CI:3.78-53.90), loss of appetite (aOR = 33.23, 95%CI:3.19-345.90), and ≥3 negative NAAT (aOR = 29.04, 95%CI:5.60-150.57) were significantly associated with increased odds of reactive serology (Fig 1B).

Various national clinical case definitions were evaluated (Fig 1D) for individuals with no or negative prior NAAT in the context of a high-risk outbreak setting. No significant association with serological reactivity was observed using the Canadian (aOR = 1.64, 95%CI: 0.58-4.62), European (aOR = 1.59, 95% CI: 0.57- 4.49), or World Health Organizations’(WHO) (aOR = 3.55, 95% CI: 0.48-26.46) definitions; however, a significant association was observed for the US CDC case definition (aOR = 3.56, 95% CI: 1.21-10.45). Other significant case definitions included having at least one systemic symptom (aOR = 4.54, 95%CI: 1.74-11.82) and fever with one additional systemic symptom (aOR = 9.89, 95% CI: 2.28-42.84).

Discussion

Findings of this study are consistent with the results published by Menni et al, which also demonstrated a strong association between COVID-19 diagnosis and systemic symptoms6; however, our findings provide additional insight to inform outbreak management practices and policies in LTC facilities. Our study also contributes to the growing evidence for mild/atypical presentations of COVID-19 particularly among the elderly, such as falls, dizziness, and confusion.7 In other LTC settings, poor identification of these atypical symptoms has contributed to ongoing transmission of SARS-CoV-2.8 Serological studies of COVID-19 have largely focused on cluster identification and characterization,9 assessment of seroprevalence,10 and patterns of seroconversion.11 A recent study among hospitalized patients also utilized serology to identify cases with negative NAAT or asymptomatic infections12; however, no studies to date have used serology to inform clinical case definitions and subsequently infection control measures in LTC facilities.

Our findings support using a low threshold for symptoms in LTC settings (particularly nonrespiratory symptoms) when considering exclusion and isolation of symptomatic staff and residents. Given the nonspecific nature of symptoms found to be highly predictive, such as headache, myalgia, and loss of appetite, implementation of universal contact/droplet precautions early in the outbreak may be effective in curbing transmission within facilities, rather than relying on isolating residents when they present with fever and/or respiratory symptoms. Moreover, staff and residents with several negative NAATs for COVID-19 should warrant further investigation with serology and/or be considered a clinical case if repeat NAAT testing is due to persisting symptoms. At last, ongoing evaluation of the Canadian, European, and WHO probable case definitions in outbreak settings is necessary, given gaps in COVID-19 diagnosis highlighted by this and other serological studies.12 Amendment to align more closely with the US CDC definition, which was more sensitive to historical infection in this analysis, may be appropriate in LTC outbreak settings.

Strengths of this study include serological testing on several platforms and utilization of multiple sources (ie, phone interviews, medical charts, and public health data) to gather reliable clinical histories immediately after the outbreak; however, the study was limited by the small sample size, preventing further regression analysis stratified by case type. Given that systematic collection of clinical histories was refined over the duration of the outbreaks, symptoms may have been underreported for some resident cases. Our findings should be generalized to other settings with caution, as the study was conducted in an outbreak setting with a high pretest probability for COVID-19.

The use of serological testing introduced some additional limitations. Baseline serological testing was not available at the start of the outbreaks and thus prior cases may not have been identified; however, both LTCF facilities represent the earliest COVID-19 outbreaks and cases in Canada, reducing the theoretical probability of prior infection to the start of the outbreak. Due to the rapid and evolving nature of the pandemic response, there is also potential risk for misclassification bias, as the clinical and diagnostic laboratory data structures used to compare and interpret serology results underwent continual quality improvement and reconciliation. While diagnostic misclassification may also occur due to the performance characteristics of COVID-19 serological assays, tests used in this evaluation were found by the performing laboratory to have specificity of 97%-99.5% and sensitivity of up to 98% at >14 days from symptoms onset. An orthogonal approach to the interpretation of test results further improved the overall specificity.

Conclusion

Our serological survey demonstrates that generalized/nonspecific symptoms and repetitive negative NAAT testing are highly associated with seropositivity. The findings of this survey can help inform case identification when managing COVID-19 outbreaks in LTCFs.

Contribution statement

All authors made substantial contributions to the manuscript, including the conception/design (RV, AH, IS, MMu, PL), data acquisition (IS, MMu, MMc, PL, MK, AM, NC, SB, MS), data analysis (RV, CG), and interpretation of data for the work (all authors). RV initially drafted the manuscript, with all authors revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors provide final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Footnotes

Funding Statement: No financial sources/grants to disclose.

Conflicts of interest: None to report.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2020.10.009.

Appendix. SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

References

- 1.Hsu AT, Lane N. Impact of COVID-19 on residents of Canada's long-term care homes – ongoing challenges and policy response. Int Long Term Care Policy Netw. 2020 Available at: https://ltccovid.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/LTC-COVID19-situation-in-Canada-22-April-2020-1.pdf. Accessed October 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winter AK, Hegde ST. The important role of serology for COVID-19 control. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:758–759. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30322-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jartti L., Langen H, Söderlund-Venermo M, Vuorinen T, Ruuskanen O, Jartti T. New respiratory viruses and the elderly. Open Respir Med J. 2011;5:61–69. doi: 10.2174/1874306401105010061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Caeseele P, Bailey D, Forgie SE, Dingle TC, Krajden M. SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) serology: implications for clinical practice, laboratory medicine and public health. CMAJ. 2020;192:E972–E979. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.201588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roche. cobas® SARS-CoV-2 Test. Available at:https://diagnostics.roche.com/global/en/products/params/cobas-sars-cov-2-test.html. Accessed October 22, 2020.

- 6.Menni C, Valdes AM, Freidin MB, et al. Real-time tracking of self-reported symptoms to predict potential COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26:1037–1040. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0916-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vetter P, Vu DL, L'Huillier AG, Schibler M, Kaiser L, Jacquerioz F. Clinical features of COVID-19. BMJ. 2020;369:m1470. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kimball A, Hatfield KM, Arons M, et al. Asymptomatic and presymptomatic SARS-COV-2 infections in residents of a long-term care skilled nursing facility - King County, Washington, March 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:377–381. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6913e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yong SEF, Anderson DE, Wei WE, et al. Connecting clusters of COVID-19: an epidemiological and serological investigation. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:809–815. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30273-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Skowronski DM, Sekirov I, Sabaiduc S, et al. Low SARS-CoV-2 sero-prevalence based on anonymized residual sero-survey before and after first wave measures in British Columbia, Canada, March-May 2020. medRxiv. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yongchen Z, Shen H, Wang X, et al. Different longitudinal patterns of nucleic acid and serology testing results based on disease severity of COVID-19 patients. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:833–836. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1756699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Long QX, Liu BZ, Deng HJ, et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26:845–848. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0897-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.